Abstract

This article offers a critical analysis of two ‘replicas’ of monuments destroyed by ISIL in 2015: the Institute for Digital Archaeology’s Arch of Palmyra (2016) and the lamassu from Nimrud, exhibited in the Rinascere dalle Distruzioni exhibition (2016). Drawing on Jacques Derrida’s formulation of hauntology and Umberto Eco’s theory of forgery, this study examines the ontological, ethical, and ideological stakes of digitally mediated replication. Rather than treating digital and physical ‘copies’ as straightforward reproductions of ancient ‘originals’, the essay reframes them as specters: material re-appearances haunted by loss, technological mediation, and political discourses. Through a close analysis of production methods, rhetorical framings, media coverage, and public reception, it argues that presenting such ‘replicas’ as faithful restorations or acts of cultural resurrection collapses a hauntological relationship into a false ontology. The article thus shows how, by concealing the intermediary, spectral role of digital modeling, such framings enable the symbolic use of these ‘replicas’ as instruments of Western technological triumphalism and digital colonialism. This research calls for a critical approach that recognizes the ontological peculiarities of such replicas, foregrounds their reliance on interpretive rather than purely mechanical processes, and acknowledges the ideological weight they carry.

1. Introduction in Eight Events

- Event 1

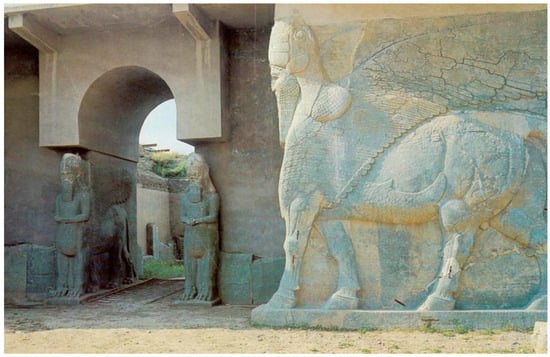

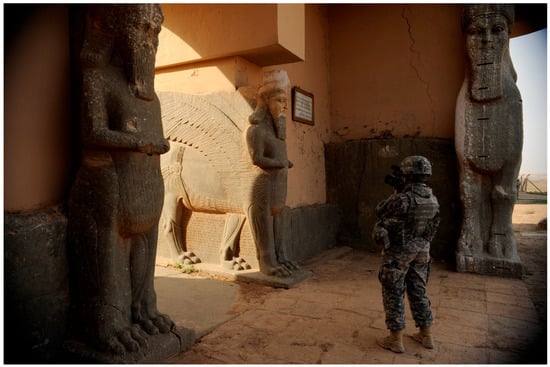

“L’avenir ne peut être qu’aux fantômes. Et le passé.” (J. Derrida). Between 883 and 859 BCE, in the ancient city of Kalhu (Nimrud)—the newly established administrative capital of the Assyrian Empire located 30 km southeast of modern-day Mosul (Iraq)—King Ashurnasirpal II initiates a building campaign that includes the construction of the so-called Northwest Palace, made of mud-brick walls and timber reinforcements. Monumental lamassu statues—creatures with human heads and animal bodies—guard the entrance to the grand throne room of the palace, emerging from three portals as “apotropaic magical beasts” [1] (p. 230) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Lamassu statues in the Northwest Palace, Nimrud (Iraq). Credit: M. Chohan, public domain.

- Event 2

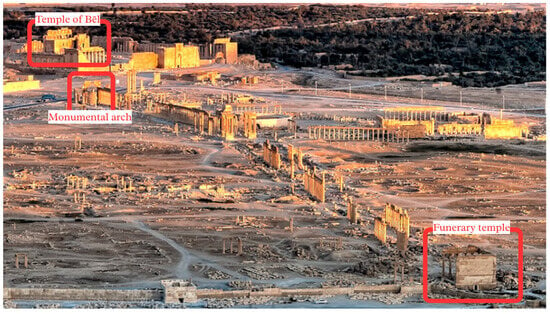

In the second quarter of the third century CE, in the ancient city of Palmyra (Syria), a monumental arch is added to a larger pre-existing system of colonnaded streets (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Built from local limestone, it features a large central arch flanked by two narrower ones. The structure belongs to the central section of the so-called Great Colonnade, which stretches approximately 1.1 km, connecting the Sanctuary of Bēl at the southeastern end of the city to the Funerary Temple in the northwestern part (Figure 3) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

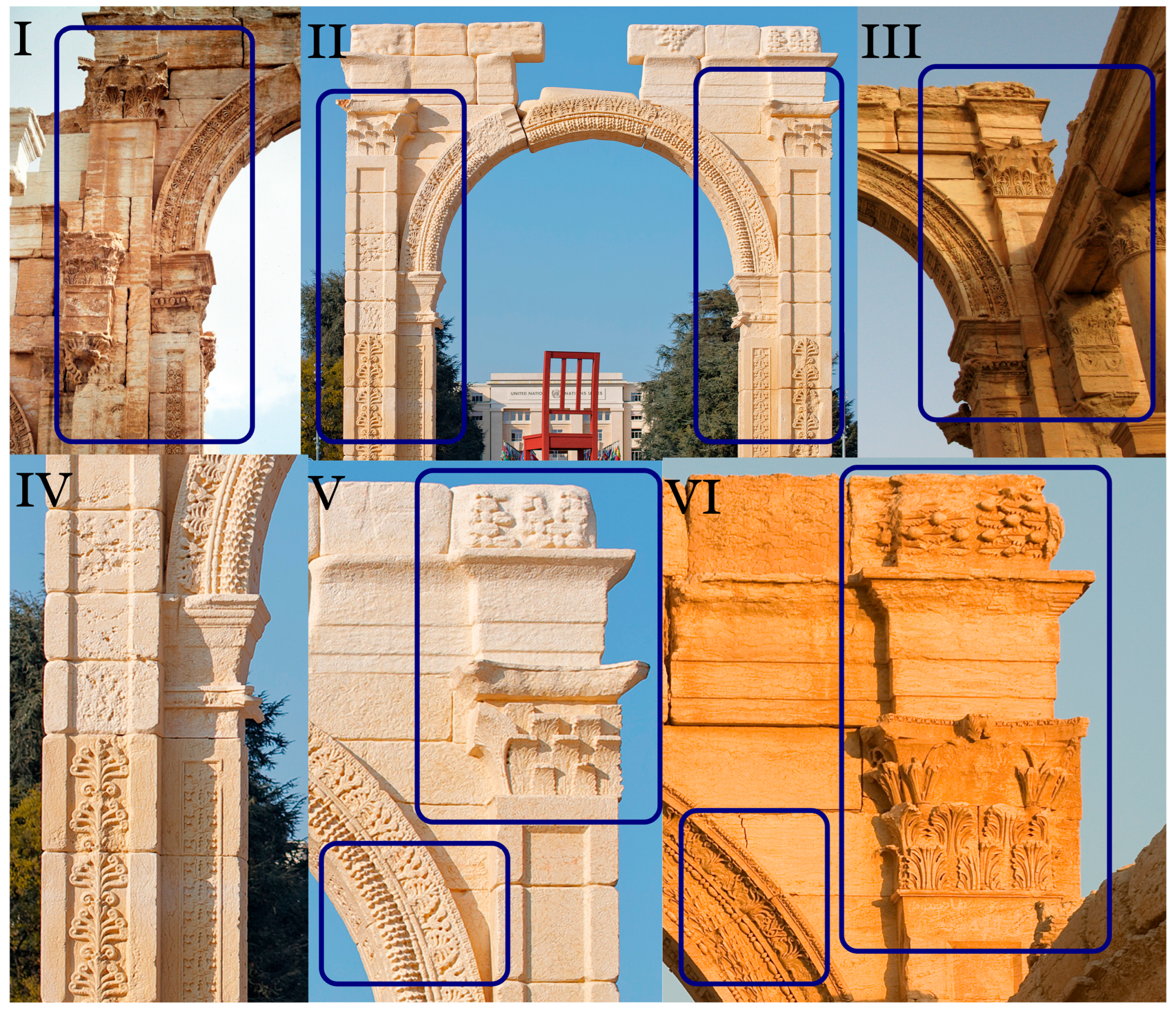

Figure 2.

The Great Colonnade and the Monumental Arch at the archaeological site of Palmyra (Syria). Credit: Vyacheslav Argenberg, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.

Archaeological site of Palmyra (Syria). Credit: Giuseppe Maria Galasso, public domain. Edited by the author.

- Event 3

In November 2008, in the ancient city of Kalhu (Nimrud), a reporter of the U.S. Air Force takes pictures of one of the lamassu statues in Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A reporter of the U.S. Air Force’s 1st Combat Camera Squadron photographs a lamassu statue in the Northwest Palace in Nimrud (Syria). Credit: U.S. Department of Defense, public domain. The appearance of the U.S. Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) visual information does not imply or constitute the DoD’s endorsement.

- Event 4

In the months preceding the capture of Palmyra by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA), as a part of the Million Image Database project, carries out photographic documentation of the site with the assistance of local volunteers. The Monumental Arch is among the documented structures [9].

- Event 5

In March 2015 in Ashurnasirpal II’s Northwest Palace at Nimrud, lamassu statues are destroyed by the military forces of ISIL [10].

- Event 6

In May 2015 ISIL military forces take control of the modern city of Palmyra and the ancient site nearby. In the following months, worldwide-spread photographs and videos attest to the destruction of several archaeological buildings, including the Temple of Baalshamin, the Temple of Bēl, and most of the Monumental Arch (Figure 5) [11,12,13].

Figure 5.

The remains of the Monumental Arch of Palmyra after ISIL’s destruction. Credit: REUTERS/Omar Sanadiki.

- Event 7

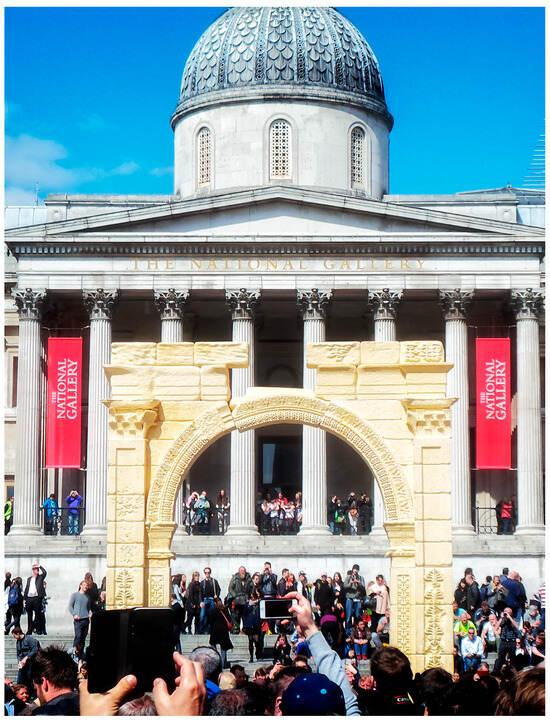

On 19 April 2016, in Trafalgar Square (London, the United Kingdom), the then-Mayor Boris Johnson unveils a ‘replica’ of the Arch of Palmyra created by the IDA [14,15]. This one-third-scale ‘reproduction’ of the ancient arch was carved from Egyptian marble by the Italian workshop TorArt in Carrara, Italy, using a robotic arm. The IDA’s arch is based on a 3D digital model derived from the photographs of the ancient monument mentioned in Event 4. [9]. Between 2016 and 2019, it was showcased in several cities around the world, from New York City to Dubai (Figure 6).1

Figure 6.

The Institute for Digital Archaeology’s ‘replica’ of the Monumental Arch of Palmyra in Trafalgar Square (London) in April 2016. Credit: Garry Knight, licensed under CC BY 2.0.

- Event 8

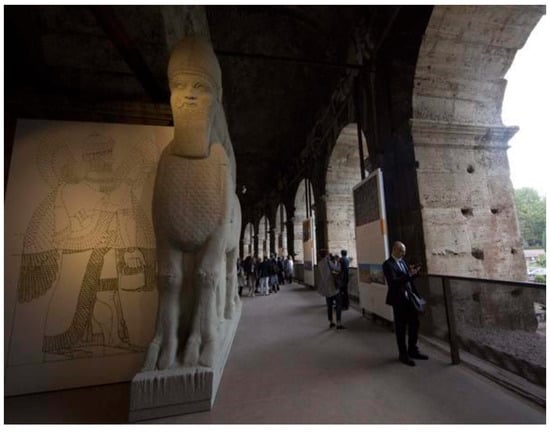

In December 2016, at the Colosseum (Rome, Italy), the exhibition Rinascere dalle Distruzioni. Ebla, Nimrud, Palmira (Rising from destruction: Ebla, Nimrud, Palmyra, RfD), promoted by Incontro di Civiltà, displays 1:1 ‘replicas’ of three monuments destroyed by ISIL in Iraq and Syria: a lamassu statue from the Northwest Palace of Nimrud (Figure 7), the Archive Room of Ebla, and the ceiling of the cella of the Bēl Temple in Palmyra [16]. The digital model of the lamassu from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (Figure 1) was created using five high-resolution photographs from those mentioned in Event 3 (Figure 4). The three ‘replicas’ were later displayed in different venues across Europe.2 At the end of August 2019, the lamassu was donated and shipped to Iraq; in February 2024, it became a part of the collection of the new museum in Basra [17].

Figure 7.

‘Replica’ of the lamassu from Nimrud, displayed in the exhibition Rinascere dalle Distruzioni. Ebla, Nimrud, Palmira, at the Colosseum in Rome (Italy), October–December 2016.

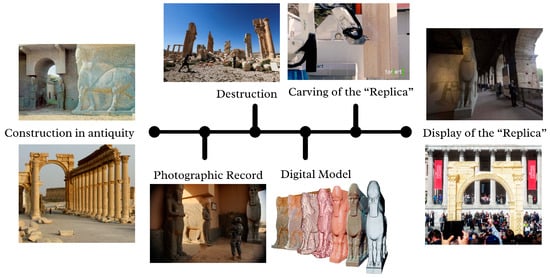

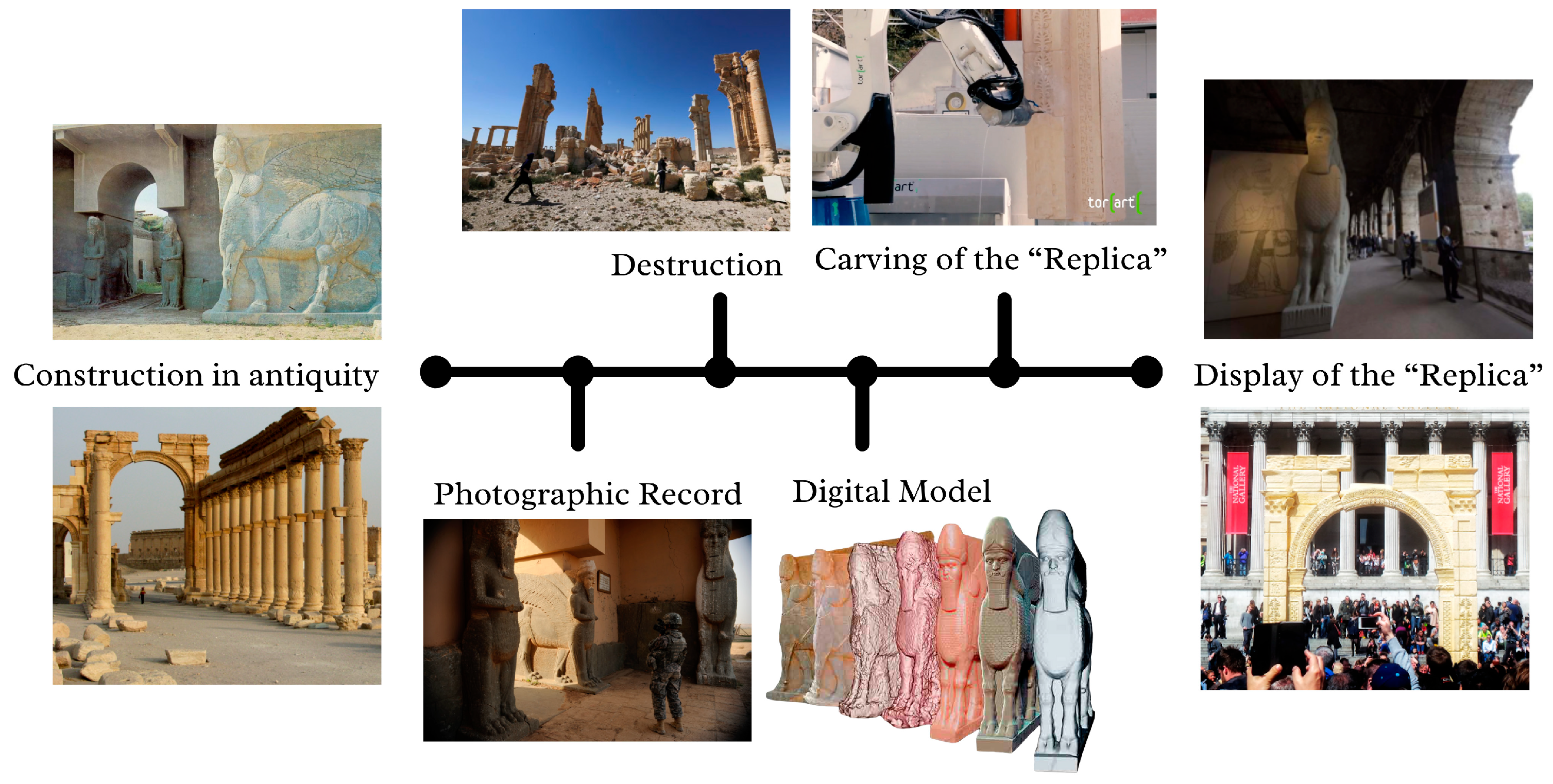

These are (some of) the Events that form the factual bedrock upon which this essay is built. They are presented in chronological order, following a sequence of actions and reactions, as commonly structured in previous scholarly inquiries (Figure 8). They can be outlined as follows:

Figure 8.

Chronological succession of the Events presented in the Introduction.

Figure 8.

Chronological succession of the Events presented in the Introduction.

I aim to complicate this narrative by further interrogating these Events beyond a linear historical framework, treating both the human agents—ancient kings and sculptors, ISIL militants, photographers, creators of digital and physical replicas, politicians, and cultural heritage experts—and the associated objects as dynamic actants. The material entities in question—the ‘original’ monuments and physical ‘replicas’—are thus examined not only as static artifacts but also as outcomes of digital and technological processes as well as cultural, political, and ideological acts. To this end, I propose deconstructing the linear relationship among the ‘original’, digital, and physical objects by critically unpacking the ontological, material, visual, ethical, and cultural dimensions of two exemplary cases: the ‘replica’ of Palmyra’s Monumental Arch, produced by the Institute for Digital Archaeology (2016), and the lamassu displayed in the exhibition Rinascere dalle Distruzioni. Ebla, Nimrud, Palmira (Rising from Destruction: Ebla, Nimrud, Palmyra) held at the Colosseum in 2016.

2. How to Build a Specter

2.1. From Stone to Screen (and Back): Replicating the Arch and the Lamassu

Let me begin with the monument mentioned in Event 7 (Figure 6): the ‘copy’ of the Arch of Palmyra. First unveiled in Trafalgar Square by the then-Mayor of London, Boris Johnson, the arch was built by the Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA), an organization founded in 2012 by Roger Michel with the mission to “promote, improve and expand […] important new digital tools” in the field of classical archaeology [18]. One of the IDA’s projects, the Million Image Database, seeks to establish a comprehensive digital archive of 3D and digital images of global cultural heritage.3 As a part of this initiative, documentation was conducted at the ancient site of Palmyra with the assistance of local volunteers, until the city was seized by ISIL militants in 2015 (Event 4).4 In the aftermath of the destruction at the archaeological site (Event 6), the IDA decided to use data from the Million Image Database to recreate one of the demolished monuments [19]. After the project underwent several changes regarding the object to replicate, methods of construction, scale, and materials, the IDA decided to make a “26,000 lb monumental-scale marble reconstruction of the Triumphal Arch” [9] built in Palmyra in the third century CE (Event 7, Figure 6). On the IDA’s official website, the arch is presented as a “1/3 scale reproduction” of the ancient one, created “using a combination of computer-based 3D rendering and a pioneering 3D carving technology capable of creating very accurate renditions of computer-modeled objects in solid stone” [9]. The arch (Figure 6 and Figure 9), significantly smaller than its ancient predecessor, was carved from Egyptian marble by the Italian sculpture workshop TorArt in Carrara, Italy, using a robotic arm and following a 3D digital model obtained from photographs of the ancient monument (Event 4). Therefore, it was not 3D-printed, as erroneously reported in numerous journalistic, as well as academic, accounts [20,21] (pp. 33–35). The IDA has not provided a comprehensive report detailing the creation of the digital model; a short video features snapshots of the carving process [22].

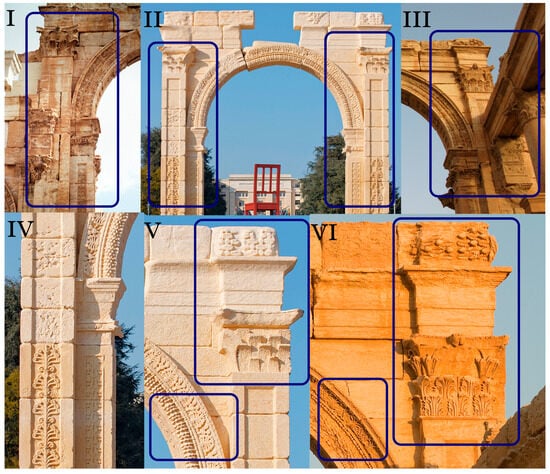

Figure 9.

Comparison between the Arch of Palmyra before ISIL’s destruction and the IDA’s arch. Credits: (I): Marina Milella, licensed under Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International; (II), (IV), (V): Markus Schweizer; (III): photograph by Vyacheslav Argenberg, licensed under Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International; (VI): Dosseman, licensed under Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International. Cropped and combined by the author.

Despite Roger Michael’s claim that the decorative features of the arch are “completely indistinguishable from the original” [23], many significant details have either been roughly rendered or entirely omitted (Figure 9) [20,24]. On the external pilasters, the acanthus leaves of the Corinthian capitals have been heavily schematized and simplified, disregarding the original number, form, and intricacy of the carving (Figure 9V,VI). Corinthian capitals, originally integrated into the shafts of these pilasters to support the architrave of the colonnaded street extending from the arch, have been entirely omitted (Figure 9I–III). Moreover, the vegetal decoration along the shaft is not only oversimplified but also positioned higher than that in the ancient monument (Figure 9I,IV). The capitals and floral frames of the internal pilasters, as well as the intricate decoration of the voussoir, have likewise been drastically simplified (Figure 9IV–VI). While the ancient arch belonged to a complex architectural structure, with a façade comprising three arches (none of which survived ISIL’s destruction), only the central arch has been replicated (Figure 2, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

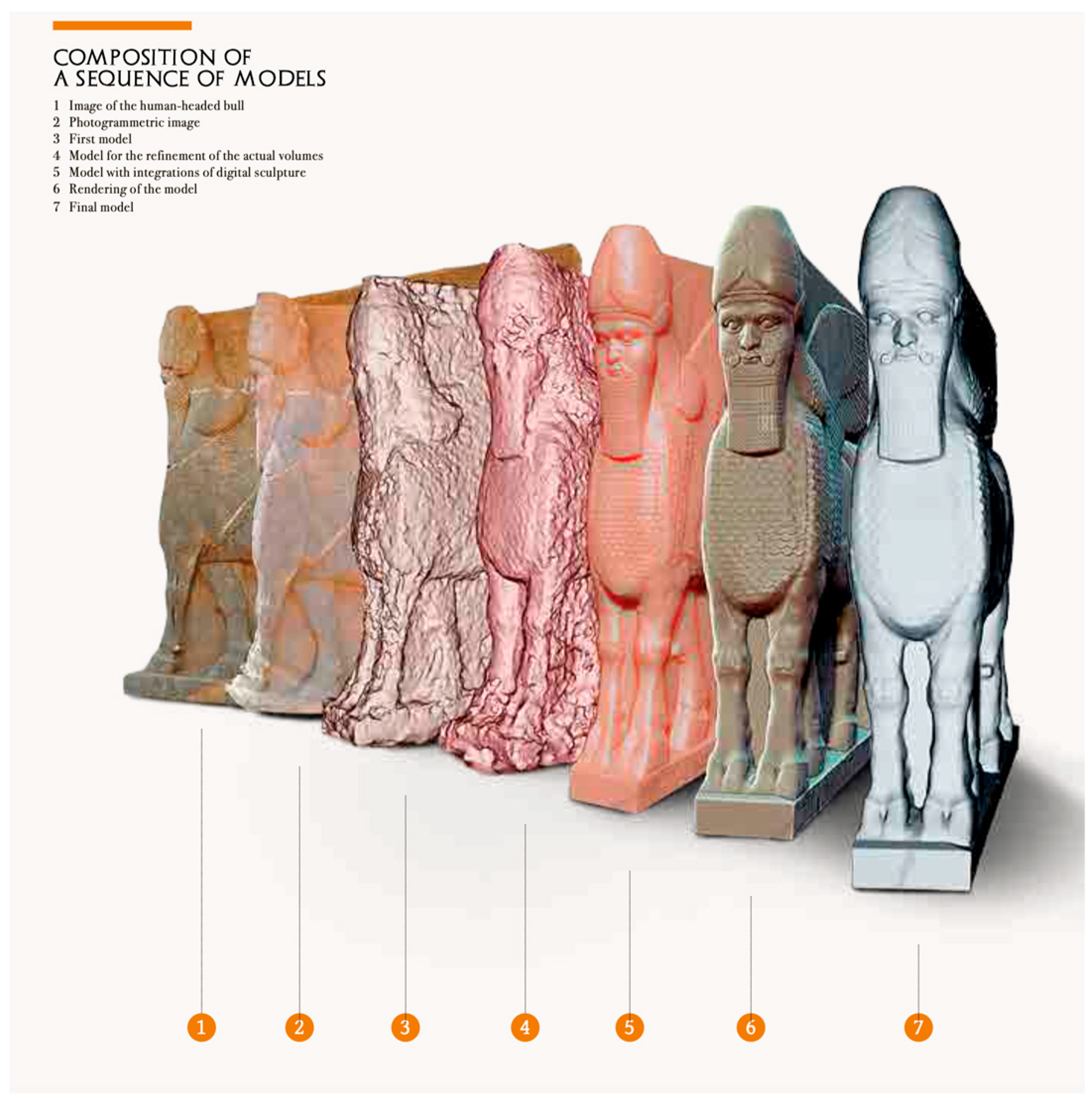

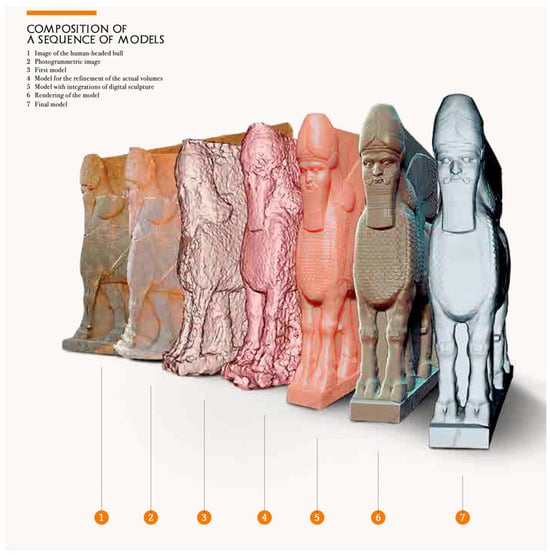

Moving to Rinascere dalle Distruzioni (RfD) (Event 8), the publication accompanying the exhibition includes historical and archaeological descriptions of the original monuments and settings, along with detailed accounts of the replication process [16]. The ‘replicas’ of the Archive Room of Ebla, the lamassu from Nimrud, and the ceiling of the Temple of Bēl at Palmyra were created using a combination of 3D models, mechanical and manual carving, painting, and (only for the ceiling of the Temple of Bēl) 3D-printed ornamental elements [16] (p. 40). In the case of the lamassu from Nimrud, the team coordinated by restorer Nicola Salvioli followed a multi-stage process that combined digital technology with manual craftsmanship. The available photographs (Event 3) were calibrated and used to generate a photogrammetric image, from which “the first three-dimensional, numerical model of the lamassu” was produced [16] (p. 50) (Figure 10, steps 2 and 3). This initial rough 3D model was scaled and refined through digital sculpting, with missing elements reconstructed based on photographs and a comparative analysis of similar lamassu statues in museum collections (Figure 10, steps 5 and 6). To create the physical ’replica’, the digital model was “broken down into virtual modules, namely, parallelepipeds, which were, in turn, sliced virtually then reproduced as sintered and expanded polystyrene sheets” [16] (p. 51). These polystyrene sheets were milled using a CNC machine and glued together to form 16 blocks “comprising partially lightened cores and a sculpted relief” [16] (p. 51). The blocks were designed with internal cavities to accommodate a metal frame that stabilizes the structure. Once assembled, the surface of this “large, three-dimensional puzzle in white” (Figure 10, step 7) underwent manual cleaning and refinement, including the carving of details and the application of a stone–resin mixture closely matched to the original in color and texture (Figure 10) [16] (pp. 50–56). This case is exemplary in demonstrating the possibilities offered by digital technologies and CNC milling machines to generate digital “molds” from photographic evidence alone, even in the absence of the original artifact, and to produce physical replicas from them. At the same time, it highlights how several stages of the replication process inevitably involve subjective interpretation and alteration, both in the creation of the virtual model and in the manual crafting of the physical object.

Figure 10.

Sequence of the different models used to create the lamassu replica for the Rising from Destruction—Ebla, Nimrud, Palmyra exhibition ([16] (p. 53)). Courtesy of Nicola Salvioli, used with permission.

The distinctive features of the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu raise the question of how such objects should most appropriately be classified. “Copy”, “replica”, “reproduction”, and “reconstruction” are terms frequently employed in both public and academic discourses. According to the Collins English Dictionary, a copy is “something that has been made to be exactly like something else”, and a replica is “an exact copy of an object”, implying the existence of two distinct objects—a ‘model’ and a ‘copy’. The term reconstruction presupposes that an object has been damaged or destroyed and subsequently rebuilt or restored. This issue is not merely linguistic but also philosophical because the matter of ‘copies’ and ‘originals’ raises questions of identity—specifically, qualitative identity [25]. Drawing on variations of the Aristotelian notions of matter and form to compare the described ‘copies’ with the ancient monuments, one finds that the former fail to align with the latter on either level, as they diverge in several critical aspects—including material, color, dimensions, and iconographic or architectural details. Thus, if the IDA’s arch or the RfD lamassu is presented as a ‘copy’, a ‘replication’, or a ‘reconstruction’ of its ancient model, a qualitative identity is (incorrectly) implied. One could counter that a certain visual continuity between the ancient and the new objects remains evident and that both the crafting of the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu involved significant time, specialized skill, research, and material selection—clearly distinguishing them from, say, mass-produced souvenirs from a museum gift shop. A comparison of the two projects also reveals that they met different qualitative and scholarly standards (I will return to this point later). Yet even in the case of the lamassu, which arguably comes closer to its destroyed model, the creators of the ‘copy’ themselves acknowledge that their work resulted in “a version of the Lamassu which, in fact, never existed” [16] (p. 56). What, then, are the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu? This definitional question necessitates a line of inquiry that recognizes that ‘original’ and ‘copy’ are not the only components at play and that addresses the ontological relationships among the lost ‘original’, the ‘copy’, and the digital model derived from photographs of the former and used in the creation of the latter. I propose to approach this matter by reconsidering the relationship among the lost ancient monument, the digital model, and the physical ‘copy’ and by shifting the analytical lens from an ontological to a hauntological framework.

2.2. Mourning Monuments: The Arch and the Lamassu as Specters

The multiple and variable steps involved in the processes of digital and physical replication, as outlined in the preceding paragraphs, underscore that the relationship between lost ‘originals’ and ‘copies’ produced through digital models should not be understood merely in linear terms or as straightforward genealogies. To address the complexities of this relationship—further affected, in our cases, by the violent destruction of one of the subjects—I propose drawing on Derrida’s concept of the specter, as articulated in Spectres de Marx (1993) [26]. Here, Derrida reinterprets Marx through Hamlet, centering on the ghost’s demand for justice and the notion of time being “out of joint”. For Derrida, this Shakespearean phrase operates on two levels: Ontologically, it signals a temporal disjunction in which the present is unsettled by the return of spectral figures; ethically and politically, it designates a historical moment in which the possibility of justice appears as both an unfulfilled injunction from the past and a deferred promise of/from the future. The present is, thus, a haunted site, inhabited by spectral traces coming both from the past and the future: “it is a proper characteristic of the specter, if there is any, that no one can be sure if by returning it testifies to a living past or to a living future” [26] (p. 99).

My own mobilization of Derrida’s hauntology entails reworking concepts and trajectories developed in Spectres de Marx to address the specific concerns of the present analysis. This approach requires two preliminary considerations. First, while Derrida did not formulate hauntology with cultural heritage in mind, hauntology’s inherently asystematic features have allowed it to proliferate across disciplinary boundaries, giving rise to different hauntological frameworks in fields ranging from literary criticism and music to anthropology and cultural heritage [27,28,29,30]. For the purposes of this research, it is also worth emphasizing that hauntology has found particularly fertile ground in photographic theory, a trajectory already initiated by Derrida himself [31,32,33,34,35]. Second, while hauntology has been justly embraced for its productive adaptability, post-Spectres engagements with hauntology risk falling into two opposite, but complementary, pitfalls: a superficial use of hauntology as a ready-made concept rather than a deconstructive tool and an over-theorization that diverts attention from the specific subject at hand [27]. For these reasons, the proposed methodological approach engages selectively with specific concepts and trajectories from Spectres de Marx to develop a situated deconstruction of the phenomenon under investigation. In other words, I allow the ‘copies’ of the arch and the lamassu to be haunted by the specter(s) of Spectres de Marx; I take spectrality as a metaphor, but I take it seriously. In doing so, I aim to deconstruct the philosophical status of physical ‘replicas’ produced from digital 3D models of destroyed monuments, before interrogating the ethical and ideological implications of their public display.

“First of all, mourning” [26] (p. 9). For Derrida, “mourning consists always in attempting to ontologize remains, to make them present, in the first place by identifying bodily remains and by localizing the dead” [26] (p. 9). As works of mourning, the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu identify and localize the absent physical remains of the Palmyra Arch and the lamassu from Nimrud: As cenotaphs of the destroyed monuments, they render the loss visible and make the absent present by declaring their death. The work of hauntology deconstructs this work of mourning by shifting “beyond the opposition between presence and non-presence, actuality and inactuality, life and non-life” (namely, beyond “all ontologization, all semanticization—philosophical, hermeneutical, or psychoanalytical”), thereby “thinking the possibility of the specter, the specter as possibility” [26] (p. 12). Within this framework, the physical ‘copies’ not only bear a trace of the past and mourn the destruction of their ancient antecedents but also exist in a present already marked by their own inevitable impermanence. Their materiality is celebrated (see part three of this essay) as a “resurrection”, a triumph over death, destruction, and oblivion. Yet at the same time, their material existence conjures the inevitability of future decay and disappearance, coming into tension with the supposed permanence of the digital models that generated them and the seemingly infinite possibilities of their reappearance (or, rather, re-appearance): “what seems to be out front, the future, comes back in advance: from the past, from the back” [26] (p. 10). These ontological dislocations of the physical ‘copy’ make it, in hauntological terms, the embodiment of a specter and a specter itself: “for there to be ghost, there must be a return to the body […] a paradoxical incorporation […] in another artifactual body, a prosthetic body […] one might say a ghost of the ghost” [26] (p. 126) (here, and in all the quotes from Spectres de Marx, the emphasis is in the original). As a ghost of a ghost, the physical ‘copy’ is haunted both by the specter of the lost ‘original’ and by that of the digital model on which it is based.

Digital models—whether obtained by scanning an object or, if the object no longer exists, through photographs—reproduce physical objects (such as statues and buildings), while simultaneously existing within a distinct (virtual) reality. As products of replication, they possess the capacity to be replicated again, to outlive the demise of their material model, and to return to the realm of tangible reality, as in the case of the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu. The digital model of an object is, thus, tied to the past yet contains an element of futurity due to the potential for reproduction afforded by digital technologies. It manifests as a specter, a virtual bridge between a materiality that no longer is and one that might be or might never be: “this element itself is neither living nor dead, present nor absent: it spectralizes” [26] (p. 51). The digital model exists within this dislocated temporality, and its semblance is, likewise, out of joint. Unless displayed alongside the object, it can be conjured as a mental image but without any stable or defined visual features. For example, a visual comparison between the displayed ‘replica’ (Figure 7) and the lamassu at Nimrud (Figure 1) reveals nothing about the sequence of models illustrated in Figure 10. Without that illustration, one might assume that some digital models of the lamassu were used to produce the ‘copy’ and that they roughly resemble the physical ‘replica’, but their exact appearance—or even their number—would remain unknown.

Moreover, Figure 10 illustrates how a digital model is always a plurality: one of many, one among many (numbers two through six in the figure represent just a selection of all the digital models generated during the process of crafting the lamassu). Indeed, even the first photogrammetric model (number two in Figure 10) is itself based on a series—a plurality—of photographs, a medium that Derrida presents as inherently marked by absence, trace, and spectral return [32,35]. As he puts it, “the spectral is the essence of photography” [31] (p. 34). Although Derrida did not focus explicitly on digital models, his insights lend themselves to a spectral analysis of digital models generated through photogrammetry [33,34]: “Faith […] is summoned by technics itself, by our relation of essential incompetence to technical operation. (For even if we know how something works, our knowledge is incommensurable with the immediate perception that attunes us to technical efficacy, to the fact that “it works”: we see that “it works”, but even if we know this, we don’t see how “it works”; seeing and knowing are incommensurable here.) […] We are spectralized by the shot, captured or possessed by spectrality in advance” [32] (p. 117). Applying this framework to digital models, one can argue that even when a digital model is visible (on a screen or in a picture, as in Figure 10), we see that it “works” (steps 2 to 6 in Figure 10) and may know how “it works” ([16] (pp. 50–56)), yet we do not see how “it works”. Just as the numeric data associated with pixels do not have inherent color or form until interpreted by a display system, the various elements that constitute the model’s computational substrate (geometry, coordinates, mesh data, and codes), while carrying visual and spatial information, remain unseen or, rather, do not produce an image.

The ontology of the digital model is out of joint and the model itself can be addressed as a specter: “Sensuous–non-sensuous, visible–invisible, the specter first of all sees us. From the other side of the eye, visor effect, it looks at us even before we see it or even before we see period […] Especially—and this is the event, for the specter is of the event—it sees us during a visit. It (re)pays us a visit [Il nous rend visite]” [26] (p. 125). Derrida explicitly applies this visor effect to images and screens: “One has a tendency to treat […] image, teletechnology, television screen, archive, as if all these things were on display: a collection of objects, things we see, spectacles in front of us, devices we might use […]. But wherever there are these specters, we are being watched, we sense or think we are being watched” [32] (p. 122). One could say that digital models see us, for they constitute the very (digital) (pre)condition for the (material and visual) appearance of the ‘copies’ (namely, the spectral “event”, the specter’s “visit” in Derrida’s terms): By looking at the ‘copy’, we perceive the “visor” but not the “eyes” behind it. But if the spectrality of the photographic medium informs both the digital model and, consequently, the physical ‘copy’, where is the photographed—namely, the ‘original’—positioned within this “virtual space of spectrality” [26] (p. 11)?

The photographs on which the digital models are based captured the Arch in Palmyra and the lamassu at Nimrud at a specific moment on a specific day (Events 3 and 4). For Derrida, that moment—that “click”—carries the potential for spectralization: “We know that, once it has been taken, captured, this image will be reproducible in our absence, because we know this already, we are already haunted by this future, which brings our death. Our disappearance is already here. We are already transfixed by a disappearance which promises and conceals in advance another magic ’apparition’, a ghostly ’reapparition’” [32] (p. 117). From a hauntological perspective, every photograph of the Palmyra Arch and the lamassu at Nimrud is a replication, a spectral visitation. In the singularity of each repetition, of each visitation (“Repetition and first time, but also repetition and last time, since the singularity of any first time makes of it also a last time. Each time it is the event itself, a first time is a last time” [26] (p. 10)), the specter appears both as a “paradoxical incorporation, the becoming-body, a certain phenomenal and carnal form”, and as “an unnameable or almost unnameable thing” [26] (p. 6). This “Thing” is at once individualized (“this thing and not any other”) and “invisible between its apparitions” [26] (p. 6). It is the “thing” on the other side of the helmet (the “visor effect”) that sees us before we see it, appearing in the moment of its visitation, only to vanish behind the materiality of its own appearance. As Derrida notes in his discussion about the translation of the Shakespearean “time is out of joint”:“The Thing […], like an elusive specter, engineers [s’ingénie] a habitation without proper inhabiting, call it a haunting, of both memory and translation. A masterpiece always moves, by definition, in the manner of a ghost. The Thing [Chose] haunts, for example, it causes, it inhabits without residing, without ever confining itself to the numerous versions of this passage” [26] (p. 18). Applying these notions to the question of the ‘original’, I would argue that in our cases, the ‘original’ is not the state of the arch or the lamassu at the moment of their destruction, nor when they were photographed or digitally modeled, nor even when they were first built, sculpted, or designed. The ‘original’ corresponds to all and none of these singularities and could be equated to what Derrida calls the “masterpiece”—the “Thing” on the other side of the “visor”—a necessary but elusive presence that precedes and exceeds all material instantiations. In this spectral framework, the ‘original’ is historical but is not dated: “Haunting is historical, to be sure, but it is not dated, it is never docilely given a date in the chain of presents, day after day, according to the instituted order of a calendar” [26] (p. 3). The ‘original’ is that which ‘originates’, that which returns to us, “pays us a visit” [Il nous rend visite], haunting the biographies of the arch and the lamassu long before and long after their digital capture and physical destruction. This has significant implications for the initial question of qualitative identity between the destroyed monuments and their ‘copies’—between ‘copies’ and ‘originals’. If the ‘copies’ are haunted by the specter of the ‘original’ through the mediation of the digital model—that is, through photographs of the monuments—how can one account for and quantify the visual discrepancies between photographs, models, and replicas? To address this inquiry, one must further evaluate the dynamic interrelationship among ontological, hauntological, and phenomenological forms of appearance.

Let me first juxtapose three images: the sequence depicting the different stages in the production of the RfD lamassu (Figure 10), the photograph of the lamassu at Nimrud (Figure 1), and a picture of the final ‘replica’ (Figure 7). What we see are: one ancient monument—or rather, a photograph of it (Figure 1); six digital models (numbers 2–7 in Figure 10); and one polyester ‘copy’ (Figure 7). From a hauntological perspective, one might describe all these eight physical and digital objects as “paradoxical incorporation[s], the becoming-body, a certain phenomenal and carnal form”, of the same specter—namely, the specter of the ‘original’. Each of them makes the “Thing”, the ‘original’, visible without ever fully embodying it—they are haunted by it, even as they haunt one another. As seen in the previous paragraphs, the statue of the lamassu spectralizes in the moment of the photographic “shot” (not for the first, nor the last, time) [32] (p. 117). This process (“technics”), as Derrida observes, “calls upon our “faith”: We place our faith in the process of replication because we see that “it works”, as it produces yet another “phenomenal and carnal form” of the specter (a ghost of a ghost): the photograph of the lamassu. Digital replication reiterates this process, generating a plurality of “paradoxical incorporation[s]”—“another magic ‘apparition’, a ghostly ‘re-apparition’” [32] (p. 117)—in the form of various digital and, subsequently, physical models. Each time, we see that the replication works because we perceive its results—the various ‘replicas’—and we may even know how it works by understanding the processes behind the crafting of the models shown in Figure 10. Yet we do not see how it works: The non-visual substratum—the geometry, coordinates, mesh data, and codes—remains invisible. I would argue that it is precisely here—in the “incommensurable” gap between seeing and knowing [32] (p. 117)—that the “faith” invoked by photographic and digital replication may become, in phenomenological terms, a misleading guarantor of mechanical authenticity and perceived qualitative similarity. Applied to our example, the non-visuality of the numeric substratum means that one cannot distinguish between what is mechanical and what is interpretive just by examining the visual results of each stage in the lamassu’s re-production. For instance, the alterations to the model’s “substratum” based on the details “drawn from the memories of those who studied the original sculpture on site and on numerous occasions” [16] (p. 56), as well from comparisons with other preserved lamassu statues, result in visual modifications that cannot be qualitatively isolated or quantitatively assessed. Moreover, one must acknowledge that the “technics” of neither photography (the camera type, aperture, lighting, exposure, etc.) nor digital modeling (software selection and processing parameters) consists solely of “mechanical” operations.

Recent scholarship—without explicitly invoking a hauntological framework—has arrived at similar conclusions regarding the misleading perception of mechanical objectivity in digital models derived from photographic documentation [36,37,38,39]. In one such study, Adam Rabinowitz compares 3D digital models and plaster casts, describing the latter as “a Victorian analogy for the 3D digital surrogates created with structure–from–motion algorithms” [37] (p. 32). His analysis demonstrates that both forms of reproduction entail artifice, interpretation, and the potential for distortion, yet are frequently presented as purely “mechanical”, and, thus, are mistakenly perceived as free from subjective intervention or human error [37]. While a hauntological analysis of the potential spectrality of plaster casts lies beyond the scope of this discussion, Rabinowitz’s comparison provides a useful lens through which to consider how, although all forms of reproduction may entail a degree of spectrality, digital models are, in a sense, “more spectral”—or rather, how the specter operates within them at a higher “frequency of […] visibility” [26] (p. 100), a condition tied to the nature of the digital medium. As Derrida has observed, the “acceleration of technical advances” in the contemporary world has brought “so many spectral effects” and a “new speed of apparition […] of the simulacrum, the synthetic or prosthetic image, and the virtual event” [26] (p. 54). The fact that Rabinowitz and other scholars arrived at conclusions analogous to those presented in this essay, without invoking a hauntological framework, raises an unavoidable question: If similar insights can be reached through alternative approaches, what, then, is the added value of a hauntological perspective?

Let me begin by noting that the intuitions of Rabinowitz and other scholars into digital replication have led them to advocate for greater transparency and more explicit communication about the processes involved in producing digital models [37,38,39,40]. These findings are undoubtedly valuable, and one can productively assess the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu against the four key principles for the scholarly use of digital models proposed by Rabinowitz [37] (pp. 34–36) or the guidelines established in 2012 by the London Charter for the Computer-based Visualisation of Cultural Heritage [40,41]. The principles advanced by Rabinowitz include the supply of accessible information about scale and units, access to raw data, access to robust metadata that contextualize both the object and the creation process, and the documentation of the full chain of technological manipulations involved. Based on the analysis presented in the first part of this essay, the IDA’s arch fails to meet these criteria. The Rinascere dalle Distruzioni exhibition catalog and displayed panels document the full process behind the creation of the digital model, include contextual information, and acknowledge the interpretative steps and challenges that emerged during the process [16]. However, the raw data or accompanying metadata were not made publicly accessible. This qualitative line of inquiry informed the initial gesture of this article, which began by comparing the IDA’s and RfD’s projects in terms of their technical procedures and outcomes. A part of this exegesis involved a qualitative assessment of the IDA’s arch through a comparison with selected images of the Arch in Palmyra (Figure 9). Such methodologies follow the logic of the ‘original’ by establishing a standard—such as, in this case, photographs of the ancient arch—against which the quality of the replicated product (i.e., its accuracy) can be measured (for instance by using Rabinowitz’ principles or the London Charter). Far from negating the validity or necessity of such standards, the metaphor of the specter employed in the preceding paragraphs not only offers additional insights into the complex mechanisms of replication but also allows for their integration into an asynchronous framework in which different planes and phenomena coexist—or rather, co-haunt. A moment of methodological self-reflection may help to illuminate this point.

From a hauntological perspective, the referent against which I compared the IDA’s arch at the outset of this contribution—the photographs of the Arch of Palmyra—was itself haunted by multiple layers of spectrality (specters of specters): not only the spectrality inherent to the photographic medium, as discussed in the preceding paragraphs, but also the losses introduced by my own cropping of the images, the details uncaptured by the camera or rendered invisible on screen, the changes the monument may have undergone between the times the different photographs were taken, and my own selective choices in presenting images of the ancient monument from specific angles to illustrate particular points. Moreover, one cannot ignore the (haunting) impact of the ISIL militants who destroyed the Arch of Palmyra, nor the influence of the images and videos that circulated online and in newspapers, along with the discourses advanced by politicians, archaeologists, scholars, and cultural heritage experts. In broader terms, the products of digital replication are haunted not only by the technologies through which they are produced (photography, photogrammetry, etc.) but also by accumulated layers of loss, decay, and contingency over time, as well as by historical ruptures, interpretive choices, manipulations, and omissions. Derrida might call all of this “inheritance”. For Derrida, a spectral inheritance is necessarily heterogeneous: Its “readability” is never “given, natural, transparent, univocal”, but rather “call[s] for and at the same time def[ies] interpretation” [26] (p. 16). We inherit the ruin, the photograph, the model, the polyester copies of the arch and the lamassu, the statues, the acts and media strategies of the ISIL militants, and the discourses of the experts and politicians—each haunted and haunting in turn. As I proceed in this investigation, the specters seem to multiply. How many are there? How can one identify them, call them by name (“the ‘scholar’ of the future should learn […] not how to make conversation with the ghost but how to talk with him, with her, how to let them speak or how to give them back speech” [26] (p16.))? What, then, is one to do with them? The question is central to Derrida, who, significantly, speaks of specters of Marx—in the plural: “We intend to understand spirits in the plural and, in the sense of specters, of untimely specters that one must not chase away but sort out, critique, keep close by, and allow to come back” [26] (p. 87). But if “one must filter, sift, criticize” in order to “sort out several different possibles that inhabit the same injunction” [26] (p. 16), one also “must never hide from the fact that the principle of selectivity which will have to guide and hierarchize among the “spirits” will fatally exclude in its turn. It will even annhilate [sic], by watching (over) its ancestors rather than (over) certain others” [26] (p. 87). In this limit lies, I believe, the affordance offered by a hauntological approach. Even if “by forgetfulness […] this watch itself will engender new ghosts”, it will, at the same time, have allowed many others to appear, to address each other, and to speak together. Having let the specters of digital replication speak—and acknowledging all those that will remain silent—let me now turn to the others: the specters embedded in cultural, media, political, and academic discourses around the arch and the lamassu.

3. Specters on Display

In Spectres de Marx, Derrida identifies “three indissociable […] apparatuses of our culture:”

- “The culture called more or less properly political (the official discourses of parties and politicians in power in the world, virtually everywhere Western models prevail, the speech or the rhetoric of what in France is called the ‘classe politique’) [26] (p. 52);

- “Mass-media culture: ‘communications’” and interpretations, selective and hierarchized productions of “information” [26] (p. 52);

- “Scholarly or academic culture” [26] (p. 53).

The following paragraphs focus on how the IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu have been presented and deployed within these interrelated cultures.

Let me begin by offering two examples of speeches delivered during the global tour of the IDA’s arch, with additional speeches included in Appendix A: (1) “This is an arch of triumph, and in many ways, a triumph of technology and determination […]. We are here in a spirit of defiance, defiance of the barbarians who destroyed the original of this arch […]. It is with great, great pleasure, therefore, that I hereby unveil the oldest new structure in the history of this city. Ladies and gentlemen, the Triumphal Arch of Palmyra” (Major Boris Johnson, Trafalgar Square, April 2016) (Appendix A.1); (2) “We are here today to celebrate hope, to celebrate how technology gives us hope for the future […]. It’s an act of defiance, an act of saying we do not stand for terrorism, we will continue to prevail” (Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, New York City) (Appendix A.2). To address such discourses, I suggest combining Derrida’s hauntology with Umberto Eco’s analysis of doubleness and forgery, where he argues that the problem of “doubles” is also “a pragmatic one” [42] (p. 179). Eco introduces the roles (or “actants”) of the Judge, the Claimant, and the two Authors (the Author of the original object (Oa) and the Author of the copy, or Ob): “The necessary conditions for a forgery are that given the actual or supposed existence of an object Oa, made by A […] under specific historical circumstances t1, there is a different object Ob, made by B […] under circumstances t2, which under a certain description displays strong similarities to Oa (or with a traditional image of Oa). The sufficient condition for a forgery is that it be claimed by some Claimant that Ob is indiscernibly identical with Oa […]. A forgery is always such only for an external observer—the Judge—who, knowing that Oa and Ob are two different objects, understands that the Claimant, whether viciously or in good faith, has made a false identification” [42] (p. 181). Even though we are not dealing with a straightforward case of “forgery” (nobody has ever suggested that these ‘replicas’ are ‘original’), Eco’s analysis of the actants involved in a “forgery” provides valuable exegetical tools for investigating the two scenarios under scrutiny (the display of the IDA’s arch and the RfD exhibition) from a “pragmatic” perspective. Applying Eco’s nomenclature to the present cases, Palmyra in the third century CE and Nimrud in the ninth century BCE correspond to the material, cultural, and historical contexts (t1) outlined at the beginning of this contribution. The IDA’s arch and the RfD lamassu represent the ’copies’ (Ob) of the ‘originals’ (Oa). In this context, the Claimants include the IDA, the politicians who presented the arch, the promoters of the Rinascere dalle Distruzioni exhibition, the newspapers that reported on them, and the scholars who wrote about them, while I adopt the role of the Judge. In the preceding paragraphs, I—as the Judge—have already undertaken an evaluation of (1) the ontological statuses of the various Obs in relation to their Oas and (2) the hauntological tensions between the Obs and their respective Oas. I now turn to an analysis of how the Claimants have presented and showcased the various Obs within the contemporary cultural and political contexts (t2).

Beginning with the IDA’s arch, several controversial aspects emerge from the Claimants’ rhetoric. Their discourses often construct an opposition between “they”—identified as the “enemy” and the “barbarians”—and a “we” whose identity shifts between two configurations: “we” as in “the West” and “we” as in a collective entity of the West and the Syrian people. Such ambiguity has relevant implications. When “we” stands for “we, the West”, the display of the ‘replicas’ of the destroyed artifacts risks assuming a propagandistic dimension as a symbolic declaration of victory embodied by the ‘replicas’ themselves, which are presented as emblems of Western technological power: “we are here in a spirit of defiance” (Appendix A.1); “a triumph of technology and determination” (Appendix A.1); “to celebrate how technology gives us hope for the future” (Appendix A.2); “we are stronger because we build” (Appendix A.3). This is even more patent when one takes into account that starting from the IDA itself, the arch has been presented as a Triumphal Arch, when the monument is “normally referred to in scholarship as simply an arch or a ‘Monumental Arch’” [43] (p. 85). This nomenclature issue is particularly relevant, as recent scholarship has urged a more nuanced application of the term “triumphal” when referring to Roman arches. In her discussion of the IDA’s ‘replica’, Jessica Nitschke has argued that although arch monuments were widespread in Rome and across the empire, the majority were not built to commemorate a formal triumphus or even a specific military victory. Noting that no so-called triumphal arches were constructed in the Near East, she considers the label “triumphal arch” as misleading when applied to the Arch of Palmyra [43]. Kimberly Cassibry further notes that scholars often use the broad term “honorific” to describe Roman arches, yet this label can obscure the overlapping and multifaceted functions these monuments served—ranging from triumphal and funerary to votive and commemorative purposes. She also highlights the ambiguity of the term “triumphal arch”, as the concept of “triumph” itself has historically encompassed a range of meanings, from formal military processions to more general notions of success [44]. To better capture this complexity, Cassibry opts for even more inclusive terms, like “commemorative arch” and “arch monument” [44] (p. 246, n. 8). While it may be argued that triumphal arches influenced the design and symbolic function of monumental arches across the Roman Empire, it is important to emphasize that the monumental Arch of Palmyra did not commemorate any specific military victory (the claim that the arch was “built during the third century to commemorate the victory of the Roman Empire over the Parthians” [20] (p. 1) is unsupported by the available historical record and finds no corroboration in formal architectural analysis).

The striking misnomer confirms the propagandistic tone of the discourses surrounding the IDA’s arch. The Author(s) of the Ob and the Claimants have, in fact, ascribed to the ancient monument a function it never possessed, namely, that of symbolizing a military triumph over an enemy. When the misleading label of “triumphal arch” is transferred to the ‘copy’, the ‘copy’ itself becomes a symbol of Western triumph over contemporary “barbarians”, celebrating Western technological primacy and advancing a reductive narrative of a definitive military triumph over terrorism. This “rhetoric of victory” rests on the misconception that digital technologies can faithfully (“mechanically”) reproduce any destroyed artifact, thereby fostering perceptions of Western technological superiority and endorsing forms of “digital enthusiasm”—if not digital colonialism [45]. As Achille Mbembe reminds us, the “myth about the absolute superiority of so-called Western culture understood as the culture of a race—the white race” leverages technological power: “Whether it concerns the past or the present, this power is to have enabled the erecting of Western culture into a culture like no other” [46] (p. 121). Nitschke has also noticed how the display of the IDA’s arch during its global tour contributed to the colonialist overtones of the project: “The IDA arch frames both the neoclassical facade of the National Gallery on the one side and the column of Lord Nelson on the other. The setting is a stark reminder of how Britain’s colonial power led to a thirst for antiquities hunting that was justified on presumptions of cultural superiority” [43] (p. 86). Those who remain overly skeptical need only to read Eliot Engel’s speech at the unveiling ceremony in Washington, D.C.: “When you look at this beautiful Arch, we are seeing through the eyes of ancient civilizations, and to have it right here, set against the classical columns of the Capitol, is really extraordinary” (Appendix A.4).

When the Claimants adopt the viewpoint of “we = the West and the Syrian people”, they position the destroyed Arch of Palmyra as a symbol of shared cultural heritage—an association grounded in an emphasis on the arch’s “Roman” or “classical” features. However, Nitschke reminds us that the design and execution of the Arch of Palmyra, likely commissioned by the Palmyrene elite and constructed by local craftsmen, reflect local approaches to space, architecture, and identity [43] (pp. 79–81). I would further argue that the downplaying of the local features of the arch in favor of a more “classical” reading is closely tied to the detachment from its original archaeological context, namely, the so-called Great Colonnade (Event 2, Figure 3). As a part of the Great Colonnade, the arch was integrated into a distinctive architectural ensemble within Palmyra’s urban fabric of the second and third centuries CE [8] (pp. 325–327). Scholars have long debated the origins and functions of colonnaded streets [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. As Emanuele Intagliata aptly synthesizes, while their genesis has been alternatively viewed as a Roman development derived from the Greek stoa or as a localized Eastern innovation, their function within the urban environment is now better understood [8] (pp. 325–327). Rather than serving merely as circulation routes, colonnaded streets were used as commercial hubs lined with shops, and in the case of Palmyra, possibly also as architectural backdrops to religious processions [8] (p. 326). Crucially, the Great Colonnade in Palmyra also held significant social and political value, as it offered a space for elite display through the honorific statues mounted on its columns [8] (pp. 325–327). The detachment of the Arch of Palmyra from this specific material and cultural context—as seen in the IDA’s presentation of the project but echoed also in most journalistic and scholarly accounts—results in the loss of crucial information about its use and meaning in antiquity and its consequent transformation into a symbol. In other words, even in, or perhaps precisely because of, its lack of accuracy and detail, the ‘copy’ of the arch perfectly fulfills its symbolic function. The way the IDA presents the genesis of the project is emblematic of this transformation of the Palmyra Arch from an archaeological object to a symbol of Wester cultural superiority: ”People from the region selected the Triumphal Arch for this reconstruction project not only because it is a powerful symbol of Palmyra and, through it, their national identity but also because it illustrates so beautifully the fusion of early Eastern and Western architectural styles for which the site is so well known among archaeologists, and which was such a huge influence in the design of many great cities during the neo-classical period” [9]). While it is acknowledged that the “people of the region” selected the arch (though the details of the selection process remain undisclosed), the Western-centered perspective is unmistakable. This is even more evident when considering that most of the monuments destroyed by ISIL did not belong to pre-Islamic heritage [12,13]. While I do not deny that the IDA’s arch was exhibited as an act of solidarity with the people of Syria, and as an emblem of the collective struggle for peace and against terrorism, the risk of transforming this “message of peace and hope” into an instance of “digital colonialism” remains readily apparent [43,45].5

This use of the IDA’s arch is further exacerbated by the absence—throughout its global display—of any information concerning the monument’s recent history and its destruction by ISIL. If the primary goal of exhibiting the arch was to raise awareness about the conflict in Syria and the damage inflicted on both the people and monuments of the region, the display would have benefitted from labels, texts, or other explanatory devices recounting the entire “biography” of the monument, including the context of its destruction. When looking at this version of Palmyra’s Arch, one wonders what viewers might learn about ISIL, the motivations behind the destruction of cultural heritage, and, more crucially, about the people who live (and died) in the region [45,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. A partial answer to this question emerges from the Postcard to Palmyra project, in which Zena Kamash invited visitors in Trafalgar Square to share their memories and fears concerning the archaeological site of Palmyra, as well as their reactions to the display of the IDA’s arch in London [53]. While many visitors praised the IDA project as a symbolic act of solidarity with Syria and a defiance of terrorism, some expressed the same criticisms found in most scholarly contributions, such as the lack of accuracy and context and the possible colonialist connotations of the entire project. As one postcard poignantly captures: “little attention […] [was] paid to the human stories behind the arch, Palmyra, and everything which they represent” [53] (p. 617). A few misconceptions also appeared in the postcards, including the belief that the arch had been 3D-printed rather than machine carved. This confusion is also reflected in media coverage of the IDA’s arch.

Dominic Basulto, in The Washington Post, claims that “3D printers can help undo the destruction of ISIS” (7 January 2016), even though the IDA’s arch was not produced using 3-D printing [57]. Similarly, The Guardian titled its piece: “Erasing Isis: How 3D technology now lets us copy and rebuild entire cities” (27 May 2016), reporting that the IDA’s project demonstrates a “remarkable new capability to rebuild exact copies of urban structures” [58]. While newspapers and magazines include both critical responses [50,59,60,61,62] and sensationalized, often misleading language, it is primarily in the latter that one finds headlines suggesting the arch has been brought back to life or fully restored, implying a degree of authenticity that the IDA’s arch does not, in fact, possess [14,15,57,58,63].6 The Smithsonian Magazine further contributes to this narrative with its portrayal of the IDA reconstruction as “The Heroic Effort to Digitally Reconstruct Lost Monuments” (March 2016), casting the technological process in dramatic and triumphalist terms that echo the political rhetoric cited earlier [63]. These headlines obscure the material peculiarities of the IDA’s ‘replica’ and frame the project as a technologically driven act of cultural salvation, reinforcing a rhetoric of Western intervention and mastery. This glimpse into the general public’s reactions and media coverage offers valuable insight into the effects of the Claimants’ uses of the arch, supporting the assessment of the IDA’s project as problematic and misleading. As Kamash notes—in a formulation that seems haunted by Derrida’s earlier-cited reflections on the “faith” involved in the medium of replication: “One wonders whether people would have been quite so enchanted had they been made fully aware of the technology used. Masking the technology to make it seem magical […] may not have been the deliberate intention of the IDA, but this seems to be the end result of the lack of information” [53] (p. 615).

To sum up, the IDA did not clearly articulate the visual and material differences between the ‘original’ and the ‘copy’ nor the role of the digital model in the crafting of the latter, thereby fostering a misleading perception that it is possible to create nearly identical replicas of any destroyed object. In doing so, the IDA’s arch has become a symbol of Western technological power, a declaration of victory promoting a dangerous rhetoric of reconstruction: “While one may expect some companies to prefer the production of polyurethane replicas to restoring antiquities because of their own interests and potential profits, there is now also an effort to impose these replicas upon the ancient sites themselves without regard for local views” [64] (p. 116). In the aftermath of the destruction, experts who have worked at Syrian and Iraqi sites for decades firmly opposed swift restoration efforts, and on 19 April 2016, a group of archeologists signed a petition against Russia and UNESCO’s statement to restore Palmyra soon after it was retaken from ISIS. Andreas Schmidt-Colinet, in response to Horst Bredekamp’s proposal for a “combative reconstruction” of Palmyra, has stated that “We should do absolutely nothing! We can only make suggestions, perhaps create 3D animations, but above all, we can provide funding and perhaps specialized personnel” [65].7 One thing that we should do is to prioritize the voices of local people and scholars [64,65,66,67].8

The analysis of the Claimants’ presentation of the IDA’s arch through Eco’s framework suggests that the monument occupies a space between what Eco defines as a “moderate forgery” (“We assume that Oa exists, or existed in the past, and that the Claimant knows something about it. The addressees know that Oa exists, or existed, but do not necessarily have clear ideas about it. The Claimant knows that Oa and Ob are different but decides that in particular circumstances and for particular purposes they are of equal value. The Claimant does not claim that they are identical but claims that they are interchangeable” [42] (p. 185)) and “confusional enthusiasm” (“The Claimant knows that Oa is not identical with Ob, the latter having been produced later as a copy, but is not sensitive to questions of authenticity. The Claimant thinks that the two objects are interchangeable as regards their value and their function and uses or enjoys Ob as if it were Oa, thus implicitly advocating their identity. Roman patricians were aesthetically satisfied with a copy of a Greek statue and asked for a forged signature of the original author” [42] (p. 185)). As the result of a “moderate forgery” and “confusional enthusiasm”, the IDA’s arch is presented as “interchangeable” with its ancient antecedent within the “particular circumstances” of the war against ISIL, the “particular purposes” of a political affirmation of Western power and victory, and a cultural sensitivity more attuned to the affordances of digital fabrication than to questions of authenticity. To use Eco’s words, the IDA’s arch is a “fake” that has been presented as a triumph over ISIL and the irreparable damage caused by human atrocity: “We can literally roll back the clock and restore what the nihilists have damaged” (Appendix A.3). But, in fact, we cannot.

Turning to the Rinascere dalle Distruzioni exhibition, the actions of the Claimants must be evaluated based on (a) the presentation of the Ob (‘copies’), (b) the role of the Authors of Ob as Claimants, and (c) the political discourses surrounding the Ob made by cultural heritage experts and political figures acting as Claimants. At the Colosseum, the ‘replicas’ were displayed alongside labels and panels describing the archaeological and historical contexts of the lost originals (Event 8). For example, the lamassu from Nimrud was presented alongside drawings depicting the reliefs that adorned the walls of the royal palace (Figure 7). The displayed panels and the exhibition catalog offered further explanations about the technical steps and challenges encountered in producing the ‘replicas’ in the absence of a physical model, highlighting the distinctions between the ‘copies’ and the ‘originals’.9 Thereby, the exhibition at the Colosseum offers alternative approaches to some of the challenges posed by the IDA’s arch—most notably, the importance of recognizing the degree of accuracy of the ‘replicas’ and the necessity of providing contextual information about their entire “biography”. Moreover, the Incontro di Civiltà association, along with other public and private institutions, like Priorità Cultura, spearheaded a series of commendable initiatives and interventions, which have significantly advanced the current knowledge on the restoration and reconstruction of damaged cultural heritage. Their intellectual, cultural, diplomatic, and political efforts not only raised public awareness about these critical issues but also made substantial contributions to the prevention and protection of endangered or damaged cultural heritage. In this regard, one of the key outcomes of the Rinascere dalle Distruzioni project has been the use of the created ‘replicas’ as educational tools in universities and museums, following a recent, but widespread, trend in museum education [36,68,69].

The opening statement of the 2019 summary of Incontro di Civiltà‘s activities marks a significant shift from an educational to a political use of the RfD ‘replicas’. This text, written by Francesco Rutelli (the former Minister of Cultural Heritage, Minister of the Environment, and former mayor of Rome), adopts a rhetoric of reconstruction similar to the one we have just discussed: “We did not restrict ourselves to crying out against the new iconoclastic disasters […] We actually worked, together with the most qualified experts, specialized companies, and competent institutions, to prove that it is possible to reproduce the things that have been destroyed [70] (p. 5) (bold in the original). A comparison between Rutelli’s remarks and the speeches delivered in front of the IDA’s arch reveals similarly problematic implications. Rutelli’s claim that thanks to modern technologies, we (once again!) possess the power not only to restore but also to reproduce and reconstruct what has been destroyed is yet another example of what Eco defines as “moderate forgery” and “confusional enthusiasm”. It is worth stressing again that such arguments risk exploiting cultural heritage for a “rhetoric of victory” grounded in Western technological power, ultimately promoting forms of “digital enthusiasm” and “digital colonialism” [43,45]. Because, as the reports in the RdF catalog clearly state, at the actual stage, it is not possible to reproduce the things that have been destroyed, claiming otherwise results in the construction of a false ontology—a “forgery” that undermines the implications of the hauntological nature of cultural heritage replications involving digital technologies. In sum, by integrating Eco’s framework with a hauntological analysis of the relationship between the destroyed monuments (Oa) and their ‘replicas’ (Ob), one can understand how the Claimants’ presentations of these ‘copies’ risk to become instances of “moderate forgery” and “confusional enthusiasm” because they frame the connection between Oa and Ob as linear and objective, neglecting the intermediary (hauntological) contribution of the digital model—a variable construct shaped by selective interpretation and contingent reconstruction choices.

4. Conclusions

From an Eco–Derridean perspective, the political discourses surrounding the ‘replicas’ under investigation have transformed a hauntology into a (fake) ontology. In Derrida’s terms, these political and media cultures do not speak of or to the ghost—they ‘conjure’ it; that is, they try to “make it disappear”. In Spectres de Marx, the French verb conjurer carries multiple meanings, including the idea of an escamotage: “The word “Eskamotage” speaks of subterfuge or [...] sleight of hand by means of which an illusionist makes the most perceptible body disappear. It is an art or a technique of making disappear. The escamoteur knows how to make inapparent. He is expert in a hyper-phenomenology. Now, the height of the conjuring trick here consists in causing to disappear while producing “apparitions,” which is only contradictory in appearance.” [26] (p. 128). For Derrida, conjurer is also related to the performance of an “exorcism:” “[E]ffective exorcism pretends to declare the death only in order to put to death. As a coroner might do, it certifies the death but here it is in order to inflict it. This is a familiar tactic. The constative form tends to reassure. The certification is effective. It wants to be and it must be in effect. It is effectively a performative. But here effectivity phantomizes itself […]. In short, it is often a matter of pretending to certify death where the death certificate is still the performative of an act of war or the impotent gesticulation, the restless dream, of an execution” [26] (p. 48). The “cultures” discussed in the preceding paragraphs present the physical body of the ‘copy’ as a form of “resurrection”—a triumph not only over terrorism but also over time and death itself. In Derrida’s terms, by conjuring the illusion (escamotage) of the objective, mechanical reproduction in the crafting of the ‘replicas’ (“while producing ‘apparitions’”), they “make disappear” the specters that haunt the products of that replication. In doing so, they position the arch and the lamassu as both “death certificates” for the ancient monuments and symbolic “acts of defiance” (Appendix A.1) against their destruction by terrorists. The old must remain dead in order for the ‘replica’ to assume the aura of a new ‘original’—a granitic emblem of Western technological power.

Does this imply that we should banish the use of 3D modeling and printing technologies in the preservation of cultural heritage? Certainly not. For example, a number of recent projects have employed the same digital technologies as a proactive response to the controversial digitization of threatened cultural heritage sites in the Middle East [71]. In particular, in her 2016 project Material Speculation: ISIS, Iranian-born artist and activist Morehshin Allahyari 3D-printed twelve statues destroyed by ISIL in 2015, embedding a flash drive and memory card within each object to store research, images, and documentation related to the original artifacts [51,52]: “Like time capsules, each object is sealed (though accessible) for future civilizations”, thereby creating “a practical and political possibility for artifact archival while also proposing 3D printing technology as a tool for resistance and documentation” [51]. This confirms that the issue is rarely the medium or the technology itself but rather the way it is used.

To conclude, the vanished objects of antiquity spectralize in both the traces they leave behind (but also before and after) and the ever-imminent possibility of their return through countless and varied reappearances—Il nous rend visite [26] (p. 125). On the one hand, these re-appearances disclose only selected aspects of the ‘original’, shaped (“haunted”) by the medium of reproduction and the interpretive choices of the creators. On the other hand, a hauntological perspective invites us to recognize that no single moment in the life of an archaeological artifact should be regarded as more authentic than another. The very notion of an ‘original’ and its associated “aura” is misplaced within a spectral framework [72,73,74]. From this vantage point, attempts to reconstruct an object’s ‘original’ state risk confining it to a singular moment of its biography, overlooking the fact that archaeological artifacts possess a (spectral) life before and after their material creation, extending long before, and often long after, their physical destruction. When the lamassus from Nimrud were destroyed in 2015, the sculptures, which derived from iconographies and beliefs established before their creation, had already lived for millennia and stood at a site that, like the sculptures themselves, had been restored and altered over time. Acknowledging the visual distance between the lamassu exhibited in Rome (Figure 7 and Figure 10) and its ancient form (Figure 1)—“We might imagine seeing the Lamassu on a windy day, with our eyes half-shut and dust in the air” [16] (pp. 52–53)—the creators of the ‘replica’ stated that it had been rendered “as if it had been transferred to Italy and restored according to modern approaches before its destruction”, a process that resulted in the creation of “a version of the Lamassu which, in fact, never existed” [16] (p. 56). In other words, they aptly recognized that digital replication in this context is a matter of “specters, even if they do not exist, even if they are no longer, even if they are not yet” [26] (p. 176).

In the end, the question about ‘copies’, ‘replicas’, and ‘originals’ is not merely a linguistic issue; one may call these objects ‘copies’, ‘replicas’, ‘reconstructions’, or ‘surrogates’ [74], as long as their spectrality—and spectral implications—is addressed. It is a call for an openness to “the possibility of the specter, the specter as possibility” [26] (p. 13); in our case, the possibility of the replication of the specter, the specter as possibility of replication. Ultimately, it is a question of what kind of world we want to (re)build, a matter of ancient specters coming from the future and how we choose to engage with them today: l’avenir ne peut être qu’aux fantômes. Et le passé.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to warmly thank Anna Foka, Katherine Kelaidis, and Georgia Xekalaki for welcoming my contribution and for curating this important volume. This contribution draws in part from a paper originally developed for the course Ethical Issues in Museums, taught by Sally Yerkovich at Columbia University in the fall of 2018. A version of this work was presented at the “Munich–New York City Workshop on Ethics”, organized by Katja Vogt (Columbia University, 7–9 March 2020). In April 2024, I presented a revised draft at the Spectral Cartographies: Haunting and Greco–Roman Antiquity conference, organized at Princeton University by Paul Eberwine and Aditi Rao, whom I thank for accepting my paper and for fostering such an intellectually rich and collaborative environment. I am sincerely grateful to the participants at these various events for their thoughtful feedback, which has greatly enriched this project. I am especially indebted to Sally Yerkovich and Katja Vogt for their invaluable guidance and sustained engagement with this work. My deepest thanks also go to Francesco de Angelis and Zainab Bahrani, whose generous readings of multiple drafts offered crucial insights that have significantly shaped the final form of this paper. I am deeply grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and generous suggestions, which significantly strengthened this article. Portions of this work were further informed by illuminating conversations over the years with my dear friends and colleagues Guoshi (Cedric) Li and Marta del Gigia, to whom I extend my heartfelt thanks. All the remaining errors or shortcomings are entirely my own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

“This is an arch of triumph and, in many ways, a triumph of technology and determination […]. We are here in a spirit of defiance, defiance of the barbarians who destroyed the original of this arch […]. It is with great, great pleasure, therefore, that I hereby unveil the oldest new structure in the history of this city. Ladies and gentlemen, the Triumphal Arch of Palmyra” (Boris Johnson, Trafalgar Square, April 2016). The entire speech was recorded and livestreamed by The Telegraph.

Appendix A.2

“We are here today to celebrate hope, to celebrate how technology gives us hope for the future […]. But it’s also an expression of our shared history and humanity that transcends borders and nations. It’s an act of defiance, an act of saying we do not stand for terrorism, we will continue to prevail” (Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen, New York City, September 2016).

Appendix A.3

“What you destroy, we can create again […]. Ultimately, we are stronger because we build […]. We can literally roll back the clock and restore what the nihilists have damaged. It is a message to them: Everything they are working to erase can be preserved” (Mohammed Abdullah Al Gergawi, Minister of Cabinet Affairs and The Future (Dubai UAE) and Managing Director of the Dubai Future Foundation, Dubai February 2017).

Appendix A.4

“The thugs of ISIS destroyed the physical arch, but we will not, and never, allow them to take that profoundly important piece of human history away from us, away from the people of Syria, away from anyone. When you look at this beautiful Arch, we are seeing through the eyes of ancient civilizations, and to have it right here, set against the classical columns of the Capitol, is really extraordinary […]. Today, we stand shoulder to shoulder, our voices as one. We will not let the terrorists erase history; we are in solidarity with the people of Syria, who have been subjected to such unimaginable horror by ISIS and the Assad Regime. We need to stay committed to ending this barbarity” (House Foreign Affairs Committee ranking member Eliot Engel (D-NY), Washington D.C., September 2018). Available online: https://youtu.be/mvylakWVi8o?si=Ihy-PIkwECj1lFOi (accessed 13 May 2025).

Notes

| 1 | New York City (City Hall Park, September 2016), Dubai (World Government Summit, February 2017), Florence (G7 Culture Summit, March–April 2017), Arona (ceremony for the renaming of the local archaeological museum in honor of Khaled al-Asaad, April 2017), Washington, D.C. (National Mall, September 2018), Geneva (Place des Nations, commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the Second Protocol, April 2019), Bern (celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Swiss Commission for UNESCO, June 2019), and Luxembourg (December 2019–February 2020). The arch was originally intended to be sent to Syria as its final destination; following the initial announcement, no further updates have been provided regarding the monument’s future. A smaller version of the arch, produced as a part of the same project, is currently on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. |

| 2 | In 2018, the Archive Room of Ebla was donated to University La Sapienza in Rome, and since April 2019, the replica of the Bēl Temple’s ceiling has been on display at the Damascus Museum. The Ebla Archive was exhibited in front of the headquarters of the European Council in the Justus Lipsius building in Brussels. Between November 2017 and January 2018, the lamassu was placed “in defense” of the entrance of the UNESCO headquarters in Paris. The ceiling of the Temple of Bēl was on display in the exhibition Palmyra: Rising from Destruction organized at FAO headquarters in Rome during the 30th ICCROM General Assembly (from 29 November to 1 December 2017), together with a funeral bust looted from Palmyra and recovered in Italy by the Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. |

| 3 | “Armed with smartphones, DSLRs, or our proprietary lightweight, discreet, and easy-to-use 3D cameras, our dedicated volunteer photographers are capturing high-quality scans at important sites in conflict zones throughout the Middle East and North Africa. Images are uploaded through our web portal for inclusion in the open-source Million Image Database. These images will be used for research, heritage appreciation, educational programs, and 3D reconstruction” [19]. As of this writing, the database has not yet been made publicly accessible. |

| 4 | “The Institute for Digital Archaeology was, at that time, in the early stages of a documentation and cultural heritage protection project in collaboration with the people of the region. Plans were made to create a massive scale reconstruction of one of the well-known structures from the site for public display, using a combination of computer-based 3D rendering and a pioneering 3D-carving technology capable of creating very accurate renditions of computer-modeled objects in solid stone” [9]. |