Abstract

Recent research has identified a connection between ancient identities and the surrounding landscape during the Roman era in Shropshire, UK. Specifically, archaeological sites associated with distinct identities, characterised by abundant material culture remains, tend to be located in highly visible places. This suggests that their placement was intentional, possibly to signal wealth, status, and territorial control or to oversee slaves and tenants working nearby. This article aims to build on that research by examining the relationship between these identity-linked sites and the broader landscape using ArcGIS techniques. The analysis found no significant correlation between the identities and the wider landscape. Instead, all sites—regardless of identity—are situated near watercourses, Roman roads, and areas that minimise human effort and energy expenditure. These findings imply that ancient groups’ perceptions and management of the landscape varied depending on the spatial scale considered.

1. Introduction

The rural landscape is an important source of information about cultural heritage, a fact formally recognised by organisations such as UNESCO and the European Landscape Convention [1,2]. This significance was first noted in the 1950s by William George Hoskins, who, in his seminal book The Making of the English Landscape, described the landscape as a palimpsest of information from different times, which can be interpreted using appropriate techniques [3]. Similarly, the connection between culture and landscape was proposed earlier, in 1925, by Carl Ortwin Sauer. His concept of the cultural landscape views culture as the agent, the natural environment as the medium, and the resulting cultural landscape as their outcome [4,5]. In this paradigm, a cultural landscape represents the interrelationships between places, events, people, and settings over time [6]. Within this context, the rural landscape is defined as a form of cultural landscape that has emerged through a prolonged interaction between environmental factors and the activities of communities inhabiting a given area, with traces of the past manifesting as landscape patterns [7].

One key aspect of cultural and rural landscapes is their continual change over time, which can lead to the loss of cultural diversity and historical habitats [8,9,10]. Awareness of these losses—and recognition of landscapes as reservoirs of cultural heritage—has inspired several initiatives and policies aimed at preserving landscape heritage. Notable examples include the Principles Concerning Rural Landscapes as Heritage and the World Rural Landscapes Initiative, which seek to raise awareness about the value of cultural landscapes [11,12,13].

The concept of cultural landscape, and specifically rural landscape, has become increasingly important in recent years as a tool for protecting the heritage of rural areas. This includes agricultural heritage, built heritage, and the broader rural cultural environment. In fact, rural landscapes were formally recognised as a special category of World Heritage sites in 1992 [5,14]. Reflecting the growing significance of cultural and rural landscapes, a substantial body of academic work has emerged to explore the interactions between people and their surrounding environment from various perspectives. These studies encompass a range of approaches, including landscape archaeology, oral history, identity analysis, examinations of the relationships between landscape features, cultural heritage reuse, and investigations of landscape change, among others [15,16,17,18].

In line with these investigations, this article highlights one study in particular, conducted by May [19], because the current research builds upon this academic work. May developed a mixed-methods approach to identify ancient identities within the landscape. The methodology consists of two stages: a quantitative stage based on network theory, which treats archaeological sites as nodes and similarities in material culture as links, and a qualitative stage grounded in phenomenology, used to interpret possible relationships between the identified identities and their surrounding landscape. In the quantitative stage, network algorithms identify clusters of sites with similar material culture, reflecting broad identity groups in the landscape. The subsequent qualitative analysis explores the connections between these identity clusters and landscape features. May applied this approach to a sample of sites in the Shropshire region to investigate identity patterns and their evolution during Roman times.

In this setting, the concept of identity is centred on collective identities, whereby identity denotes how individuals see themselves as members of particular groups while distinguishing themselves from others [20]. This framework views social identity as multidimensional, comprising various individual identity types. These identity types can be associated with material culture through specific social behaviours or habitual practices [21,22].

Although employing social behaviour as an intermediary to connect material culture with collective identity is advantageous, it poses the challenge that past behaviours and habits are not directly observable. However, recent archaeological research has proposed that lifestyles and activities, as inferred from material remains, may serve as proxies for behaviour [21,23]. This approach forms the methodological basis of May’s investigation [19].

Expanding on this perspective, collective identity can be inferred by correlating lifestyles and activities with extant material culture. Drawing from the literature, twelve broad categories related to lifestyles and activities were delineated [21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]: construction and building practices, household organisation, culinary activities and food preparation, transportation, literacy, security, defence, leisure, personal appearance, grooming, religious practices, and economic engagements. Within this framework, sites are considered to share a collective identity when they exhibit comparable material culture indicators that reflect analogous lifestyles and activities.

In this framework, wealth is a multifaceted concept encompassing not only the tangible material culture (such as artefacts, landholdings, and agricultural productivity) visible archaeologically but also the social, cultural, and symbolic expressions of status, control, and identity as experienced and understood by the late antique agents themselves. This includes the ability to display status through site location and landscape control, as well as the lived realities of social relationships, labour supervision, and cultural values beyond mere possession of material goods. Thus, apparent absence of material wealth may not equate to lack of wealth or status in the contemporary farmer’s view but could reflect different modes of wealth expression or value systems [30,31].

The results from May’s work revealed that during the Early Roman period (approximately 43 to 200 AD), a single cultural identity occupied this landscape. This identity is associated with a set of sites characterised by relatively sparse material culture and an emphasis on agricultural production. By the Late Roman period (approximately 200 to 450 AD), this identity had evolved into two distinct groups: a low-status group marked by limited wealth, which may reflect native cultural expression, and a wealthier group exhibiting varying degrees of Roman influence. Phenomenological analysis further showed that sites in the wealthier cluster tended to be located in areas with good visibility, suggesting a deliberate effort to display status and signal control over the surrounding landscape, including supervision of slaves or tenants. In contrast, sites in the poorer cluster were situated in less visible locations. These findings demonstrate that past social relationships can be inferred indirectly through landscape analysis, underscoring that preservation efforts are important not only to maintain cultural heritage itself but also to protect the archaeological information embedded within rural landscapes for future discovery.

A notable limitation of May’s original study [19] lies in its exclusive focus on the immediate vicinity when analysing the relationship between identified identities and the surrounding landscape. Although this localised approach yielded valuable insights into the interactions between individual sites and their close environment, it does not adequately elucidate how sites and identities are spatially organised within the broader landscape. In contrast, substantial evidence indicates a non-random spatial distribution of sites aligned with specific landscape features at a larger scale. For example, Henry, Roberts, and Roskams [32] demonstrated that site locations predominantly cluster within areas of significant religious importance, implying a purposeful association between sites and landscape characteristics at a regional level. Similarly, research on archaeological site distribution in Roman Britain has identified non-random placement patterns influenced by regional topography, hydrology, and cultural boundaries [33]. Consequently, while the large-scale landscape analysis remains insufficiently explored, existing studies reveal contextual associations at the regional scale.

This article seeks to address this gap by analysing the large-scale landscape of the Shropshire region, using the same sample employed by May [19]. To do so, standard tools available in ArcGIS Pro 3.0.1 software are utilised. The goal is to integrate these results with May’s original findings to offer a clearer understanding of how ancient identities interacted with the landscape across multiple scales.

The research conducted by May and the present study are components of the same overarching project. Due to the extensive volume of results, it was not feasible to present all findings within a single publication. May’s original work [19] primarily concentrated on identifying identities within the landscape through an analysis of material culture at the sites and their immediate surroundings. In contrast, the current article aims to systematically demonstrate the relationships among the sites in the sample at a regional scale. Building on the established understanding of site interrelations in terms of proximity and material culture, this study extends the analysis to a broader spatial framework. As previously noted in related academic works, this regional perspective has revealed factors influencing site distribution, such as cultural boundaries and regional topography. Identifying factors of this nature in the Shropshire region is the aim of this work.

Because this study builds on May [19], it is important to note that the concept of identity employed here derives from [20] and was later connected to material culture by Eckardt and Swift [21,22]. In this framework, identity is conceived as a collective construct, articulated through shared lifestyles and activities that are both materially and socially recognisable. Although individual behaviours are not directly observable in the archaeological record, material culture functions as a proxy through which habits and practices may be inferred. By relating these practices to broader aspects of daily life, sites can thus be interpreted as participating in a common social identity when their material evidence reflects comparable modes of living. This perspective underscores identity not merely as an individual affiliation but as a socially embedded and materially expressed phenomenon.

The Archaeology of Roman Britain in Shropshire

To gain a better understanding of the social-historical context of people in Shropshire during the Roman Britain period, a brief description of what we know in the region is provided as follows.

Research on Roman Britain in Shropshire has traditionally concentrated on the Wroxeter Roman city, with excavations beginning in the 19th century. However, knowledge about the surrounding region remained limited, aside from a few studies that analysed cropmark typologies identified through aerial surveys [34]. A significant shift in this research approach occurred with the launch of the Wroxeter Hinterland Project (WHP) in 1994, an extensive study designed to explore the connections between Wroxeter Roman town and its hinterland [35,36]. The findings from the project demonstrated that Wroxeter had considerable influence over the nearby area, channelling communal wealth into the town and indicating the presence of a powerful, centralised elite [34]. Additionally, the project uncovered evidence concerning the broader landscape through GIS buffer analyses surrounding placenames ending in -ley, which suggested the existence of woodlands during the Roman era and a tendency for settlements to be situated in clearer, non-wooded areas [37].

Although Roman rural settlements in Shropshire remain largely unexamined, some archaeological data indicate that communities near urban centres and road settlements were somewhat influenced by Roman customs over time. In contrast, the scarcity of Roman artefacts in more remote rural locations implies either a disinterest in adopting Roman lifestyles or a lack of resources among rural populations to do so [38,39].

In considering the information revised in the last two sections, the following research questions are proposed:

- What landscape features influence the spatial distribution of archaeological sites at a regional scale, specifically in Shropshire?

- How do cultural boundaries, topography, and hydrology shape the organisation of ancient cultural identities across a large rural landscape?

- What insights can be gained by extending the archaeological identity analysis from immediate surroundings to a regional framework?

These research questions are consistent with the provided observation about Roman Britain in Shropshire. The observation outlines the focus on the Wroxeter Roman city and its influence on the surrounding region, highlighting landscape features (woodlands, clearings), settlement patterns, and different levels of Roman cultural adoption in rural areas. In addition, the opening explanation establishes rural landscapes as dynamic cultural palimpsests shaped by long-term human-environment interaction and recognised as important reservoirs of cultural heritage. This sets the foundation for understanding that rural landscapes encode social identities and historical processes within their spatial patterns. The research questions then build directly on this by aiming to uncover how specific landscape features and broader regional factors influence the spatial organisation of archaeological sites and cultural identities over a large rural area (Shropshire).

2. Methodology

In this study, a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) for the Shropshire area was created using ArcGIS software and the Land Form Panorama map obtained from the OS OpenData database. The DEM corresponds to the OS Terrain 5 dataset available on the Ordnance Survey website: https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/terrain-5 (accessed on 7 March 2023). Specifically, the version used consists of 5 km by 5 km tiles with a 5 m post spacing resolution [40].

The DEM was employed to analyse various characteristics of the wider landscape in this region and to identify potential relationships between features within the Roman-era landscape. To explore these relationships, we conducted several analyses: visibility analysis, site catchment analysis, cost of movement on land, least cost path from Roman roads, bedrock analysis, and superficial deposits analysis.

These methodologies are closely aligned with the research questions within the context of landscape archaeology in Shropshire. For the first question, which investigates landscape features influencing the regional spatial distribution of archaeological sites, analyses of visibility, site catchments, bedrock, and superficial deposits identify key physical factors (e.g., terrain, geology, soil) affecting site locations and clustering. Cost of movement and least cost path analyses from Roman roads examine how accessibility and travel routes influenced settlement patterns. Collectively, these methods elucidate how natural and human-modified landscape characteristics shape site distribution across Shropshire’s geologically and topographically diverse terrain.

Regarding the second question, which addresses the role of cultural boundaries, topography, and hydrology in structuring ancient cultural identities, visibility analysis reveals how visual access and strategic viewpoints may define cultural territories or sacred spaces. Movement cost analyses highlight connectivity and barriers shaped by the natural landscape, influencing interaction or separation among groups. Site catchment analysis examines resource utilisation across boundaries, while bedrock and superficial deposit assessments link environmental conditions to cultural practices. Together, these approaches clarify the spatial organisation of cultural identities in relation to both natural and social landscape features.

For the third question, expanding archaeological identity analysis from local to regional scales through combined visibility, catchment, and movement analyses uncovers broader spatial patterns, networks, and interactions among sites. This multi-scalar framework reveals how diverse environments, cultural zones, and access routes interrelate, offering a more comprehensive understanding of Roman-era landscape use and cultural identity than site-specific studies alone.

These methods are explained below.

2.1. Visibility Analysis

Several academic studies have demonstrated that prominent Roman-Britain sites in the landscape functioned as communication stations, utilising visibility for signalling [41]. Building on this research, visibility analysis was employed in this study to assess whether the sites under consideration are intervisible. To this end, the line-of-sight technique was adopted, which involves determining the intervisibility between two points in the landscape [42]. Using ArcGIS software, lines of sight are represented with colour coding: a green line indicates that the path between two points is visible from both locations; a red line signifies that the path is not visible; and a red line containing a green segment indicates partial visibility, where only the green portion of the path is visible from the points.

An important consideration in the analysis of visibility is the presence of vegetation, as trees in the past may have obstructed lines of sight between sites. Nevertheless, evidence of woodland clearance in the study area, particularly towards the end of the Iron Age [43], has been documented. It is important to note, however, that this does not imply the complete absence of trees, and therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

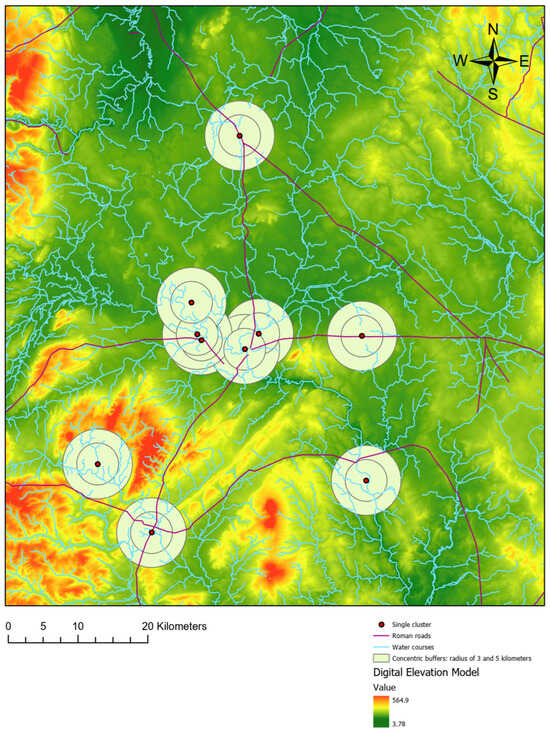

2.2. Site Catchment Analysis

Site catchment analysis is a technique developed to investigate and understand the relationship between human settlements and their local environments and economic resources [44]. In this study, it was used to determine whether the sites under investigation are associated with nearby environmental and economic resources, and whether variations in these resources correspond to differences in site identities. To do so, buffers—circular areas centred on archaeological sites—with radii of 3 and 5 km were employed. The 5-kilometre radius reflects the maximum daily range of agricultural exploitation [45], while the 3-kilometre radius identifies zones of likely more intensive economic activity around each site. This approach differs from that of May [19], who defined the surrounding landscape as the circular area with a radius of 1 kilometre centred on each archaeological site.

2.3. Cost of Movement on Land

The cost of movement on land is a technique used to estimate the effort required to traverse a landscape, defined primarily as a function of slope or topography. A digital elevation model (DEM) is employed to calculate the topographic cost incurred when moving from one cell to any of its adjacent cells. In this context, cell values represent relative cost—how easy it is to move between cells—and energy expenditure [46,47]. This approach was adopted to determine whether sites associated with a particular identity are located in areas of relatively similar movement cost. To do this, a cost raster was generated using the cost function proposed by Pandolf, Givoni, and Goldman [48]. For related archaeological research using this function, see [47,49]. The cost function is presented as follows.

where

M = Absolute cost (i.e., metabolic rate) measured in Watts

W = Subject weight (kg)

L = weight of the load (kg)

V = walking velocity (m−s)

G = Percentage slope (information obtained from DEM)

η = Terrain coefficient (used to capture how easy is to walk across a determined terrain)

In considering the work by White and Barber [47], a subject weight of 75 kilos was adopted in this formula. For load, previous studies have considered weights between 7 and 40 kilos [47,48]. Consistent with these values, a load of 10 kilos was assumed (e.g., clothing and tools). For velocity, a value of 1.3 m/s was chosen because it falls within the range of speeds used to estimate terrain coefficients [50]. Finally, a terrain coefficient of 1.1 was adopted, corresponding to dirt roads and grass. See Table 1 in [51]. Note that a value of 1 is the lower limit and relates to treadmill walking, while a value of 2.1 corresponds to loose sand. In this context, a terrain coefficient of 1.1 reflects moderate difficulty in walking across the landscape.

Table 1.

Sites included in the sample (source: based on May [19]).

2.4. Least Cost Path from Roman Roads

The least corridor path technique identifies a route between two points that minimises the accumulated movement cost [52]. This analysis was conducted to determine whether the sample sites were situated in areas of low accumulated movement cost relative to Roman roads, and to explore whether any differences might be related to varying identities. To do this, the movement cost raster developed in the previous section was used to generate least-cost paths.

2.5. Bedrock Geology

To assess whether bedrock geology influences the location of sites in the sample, we plotted these sites on the DiGMapGB-625 bedrock map from the British Geological Survey: https://www.bgs.ac.uk/datasets/bgs-geology-625k/ (accessed on 7 March 2023). The predominant bedrock types in Shropshire are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Type of bedrock in Shropshire (Source: British Geological Survey).

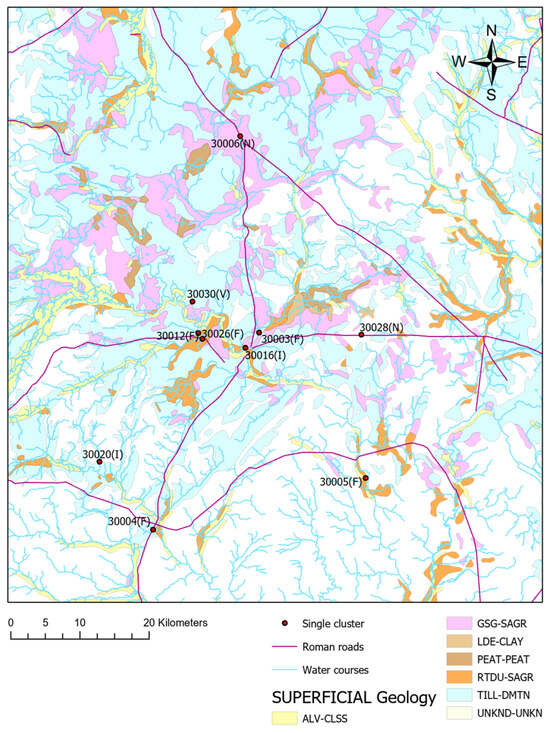

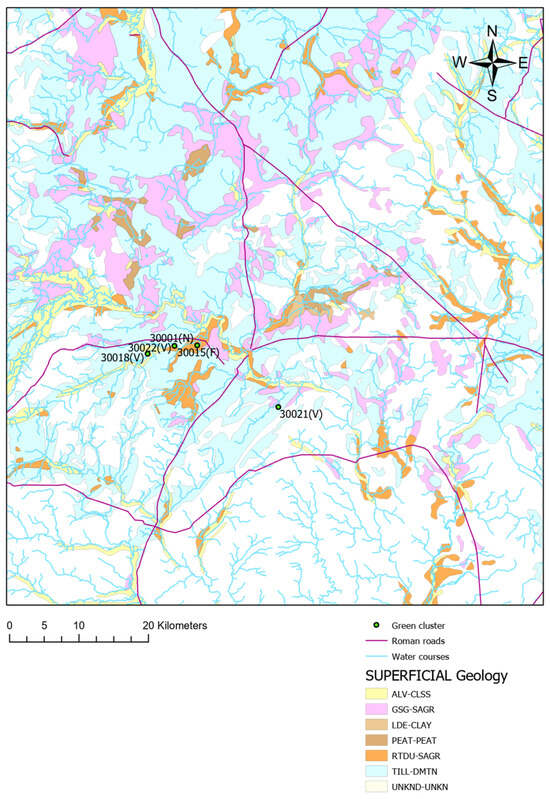

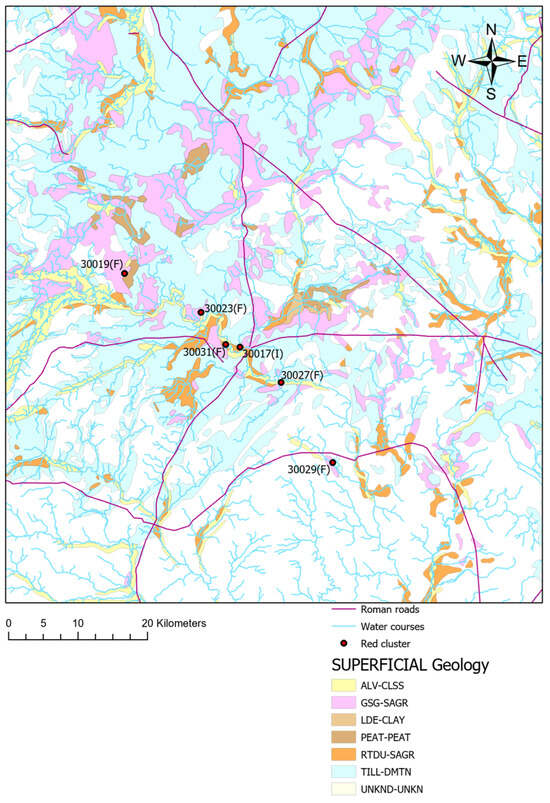

2.6. Superficial Geology

This last analysis was developed to determine whether the superficial geology influenced the distribution of the sites. As in the previous section, the sites were plotted in the DigMapGB-625 superficial deposit map: https://www.data.gov.uk/dataset/9bec0be4-c552-4769-b6dc-4073d1de9f46/bgs-geology-625k-digmapgb-625-superficial-version-4 (accessed on 7 March 2023).

The current research utilised the same sample as May [19], which was extracted from the Rural Settlement of Roman Britain Online Resource provided by the Archaeological Data Service: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/romangl/ (accessed on 22 June 2021). This resource contains a list of rural settlements with archaeological data related to the Roman period, compiled from both published academic works and grey literature. For Shropshire, the original study considered 21 excavated sites with reliable information in the database. Of these, 10 were classified as belonging to the Earlier Roman period, while the remaining sites were designated as Later Roman period settlements. Table 1 presents these sites along with relevant information for the current research.

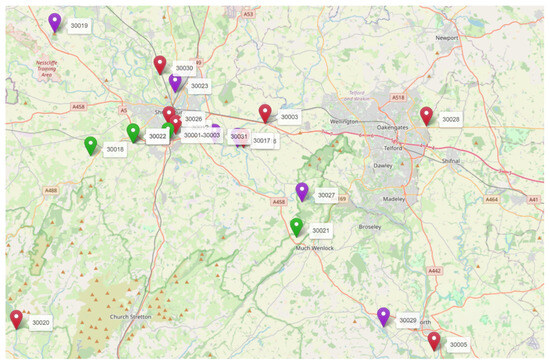

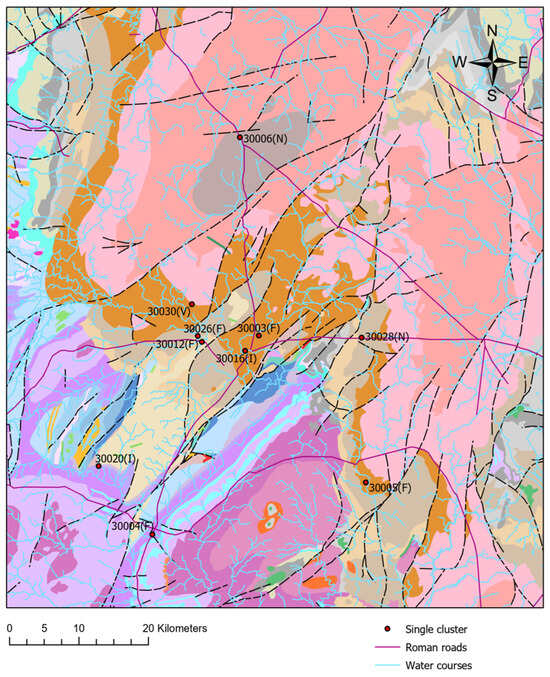

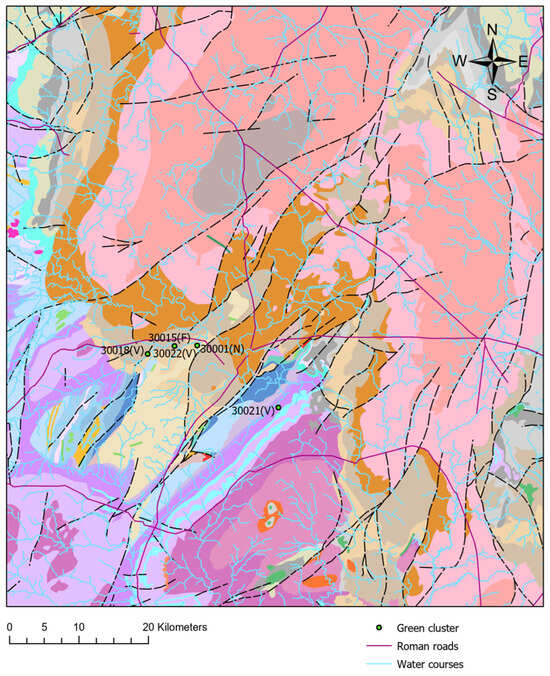

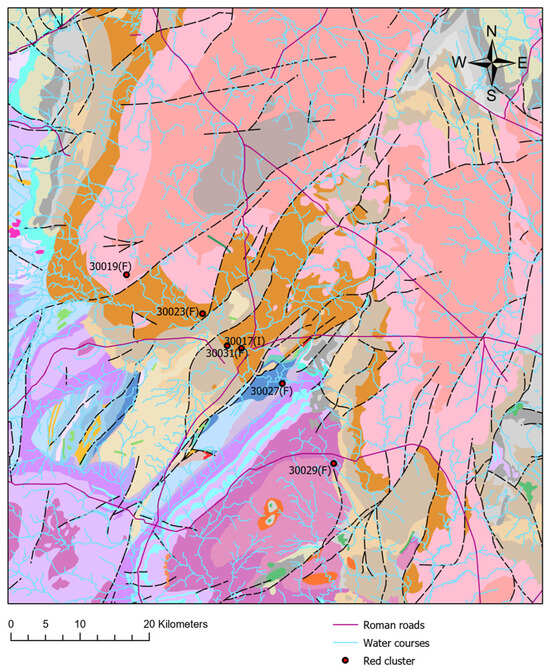

In this table, all sites from the Earlier Roman period are grouped under a single category, Identity 1. This group is characterised by a lack of material culture, which suggests a dominant native identity expression. In contrast, five sites from the Later Roman period belong to Identity 2. These sites are mainly villas and display heterogeneous material culture remains. This cluster is interpreted as representing a wealthy identity, given the presence of status-associated artefacts. Finally, six Later Roman period sites are classified as Identity 3. These sites exhibit little or no material culture, indicating either native expression or subsistence settlements. These sites are shown in the following map (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sites in the sample (red = Early Roman; Green = wealthy Later Roman; Purple = Non-wealthy native Later Roman. Number next to the points are the site ID).

3. Results

This section presents the results from analyses of visibility, site catchment, cost of movement on land, last cost path from Roman roads, bedrock, and superficial deposits.

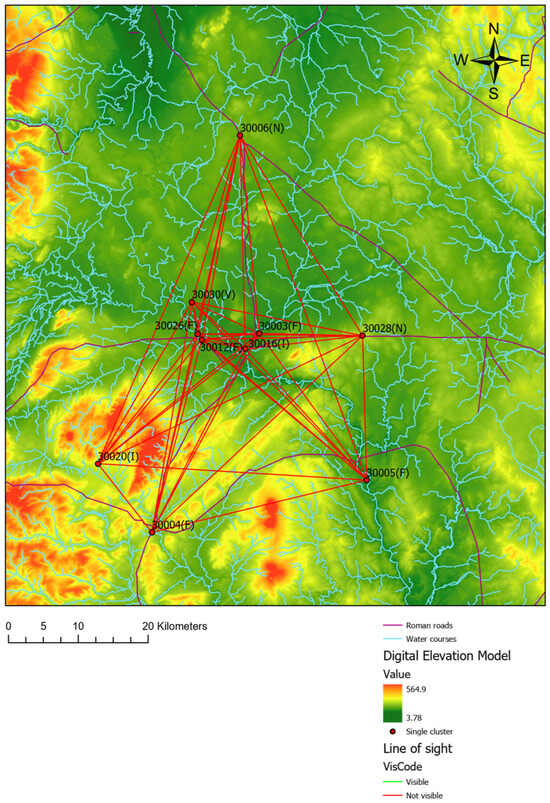

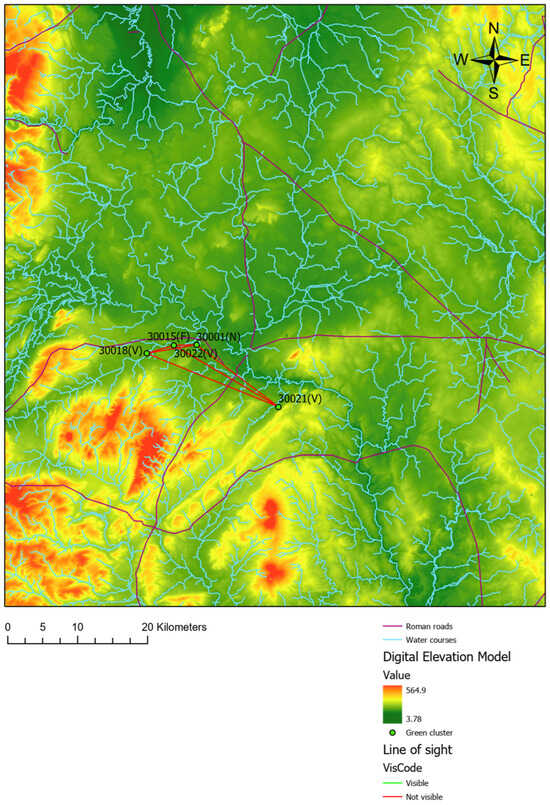

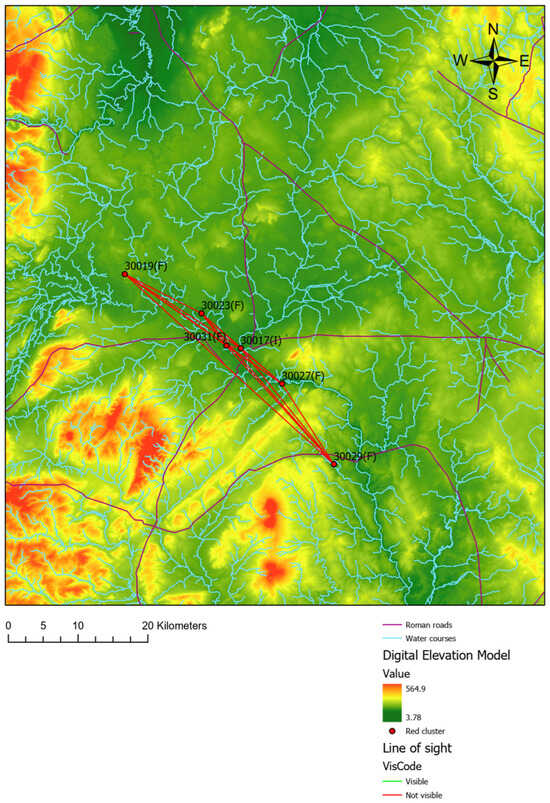

3.1. Visibility Analysis

Figure 3 shows that the sites in the Earlier Roman period, which reflect a single identity named Identity 1 in Table 1, are not visible from one another, suggesting that intervisibility between settlements was not a relevant feature associated with this identity. The same is true for the two identities in the Later Roman period, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. It is concluded, therefore, that visibility, while relevant in other contexts, plays no role in the distribution of the sites, in the manifestation of identity, or in the evolution of identities over time. See, for example, [53,54].

Figure 3.

Line of sight of the sites of Identity 1: Earlier Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 4.

Line of sight of the sites of Identity 2: Later Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 5.

Line of sight of the sites of Identity 3: Later Roman, Shropshire.

Based on these results, it is argued that the emphasis on intervisibility as a key factor requires reconsideration, particularly in the context of dispersed rural farms during the Roman period, where mutual visibility was unlikely to play a significant role in identity or social organisation. In contrast, during the Late Iron Age, hillforts were strategically situated on elevated terrain, deliberately maximising visibility and visual dominance, which held clear socio-political importance. This fundamental difference in settlement patterns and socio-political structures suggests that intervisibility had varying relevance across periods. Making this distinction explicit helps clarify why methods focusing on visibility relationships produce significant insights for the Late Iron Age but fail to capture meaningful patterns in the Roman period, where other factors likely governed social cohesion and organisation.

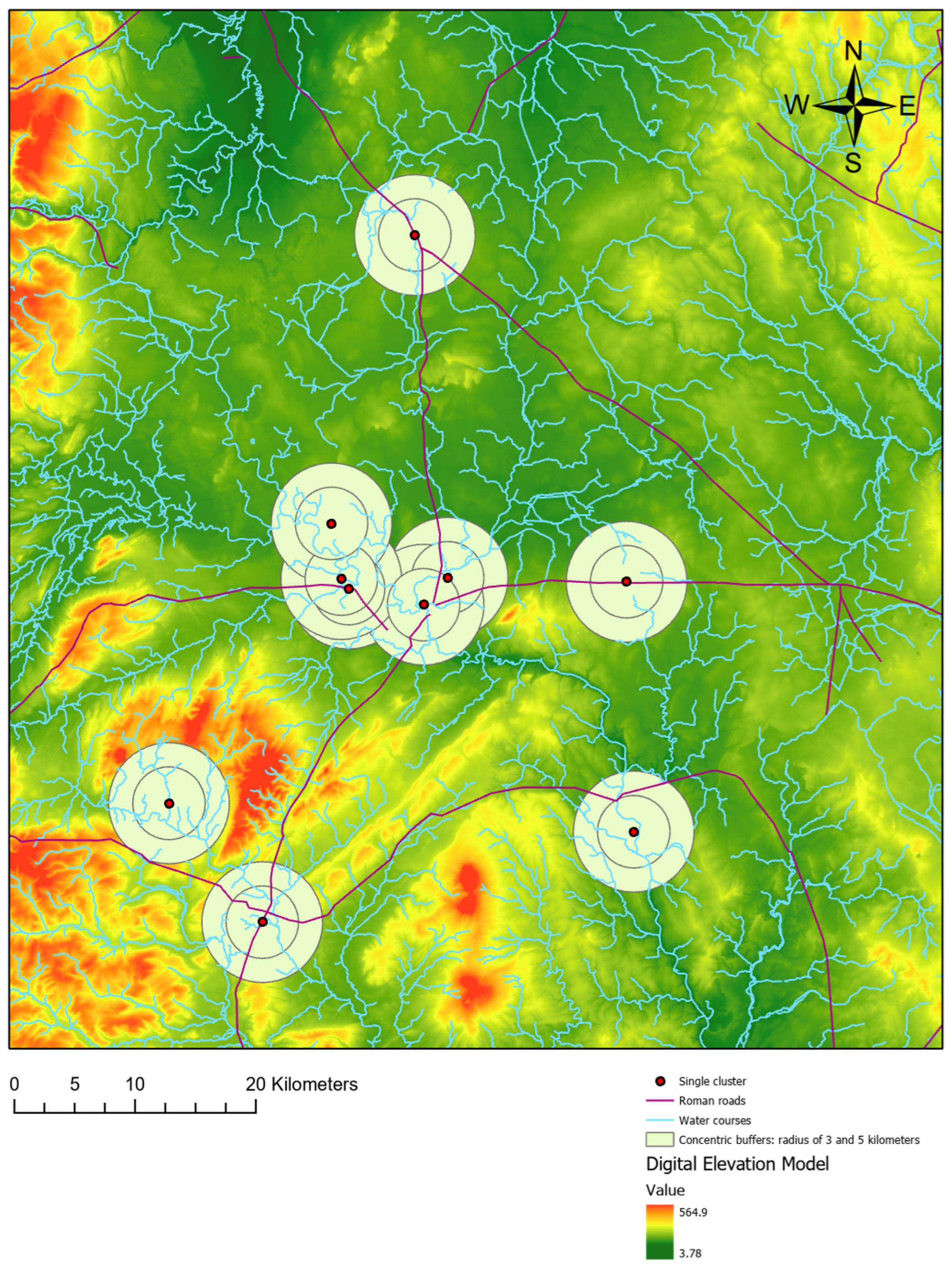

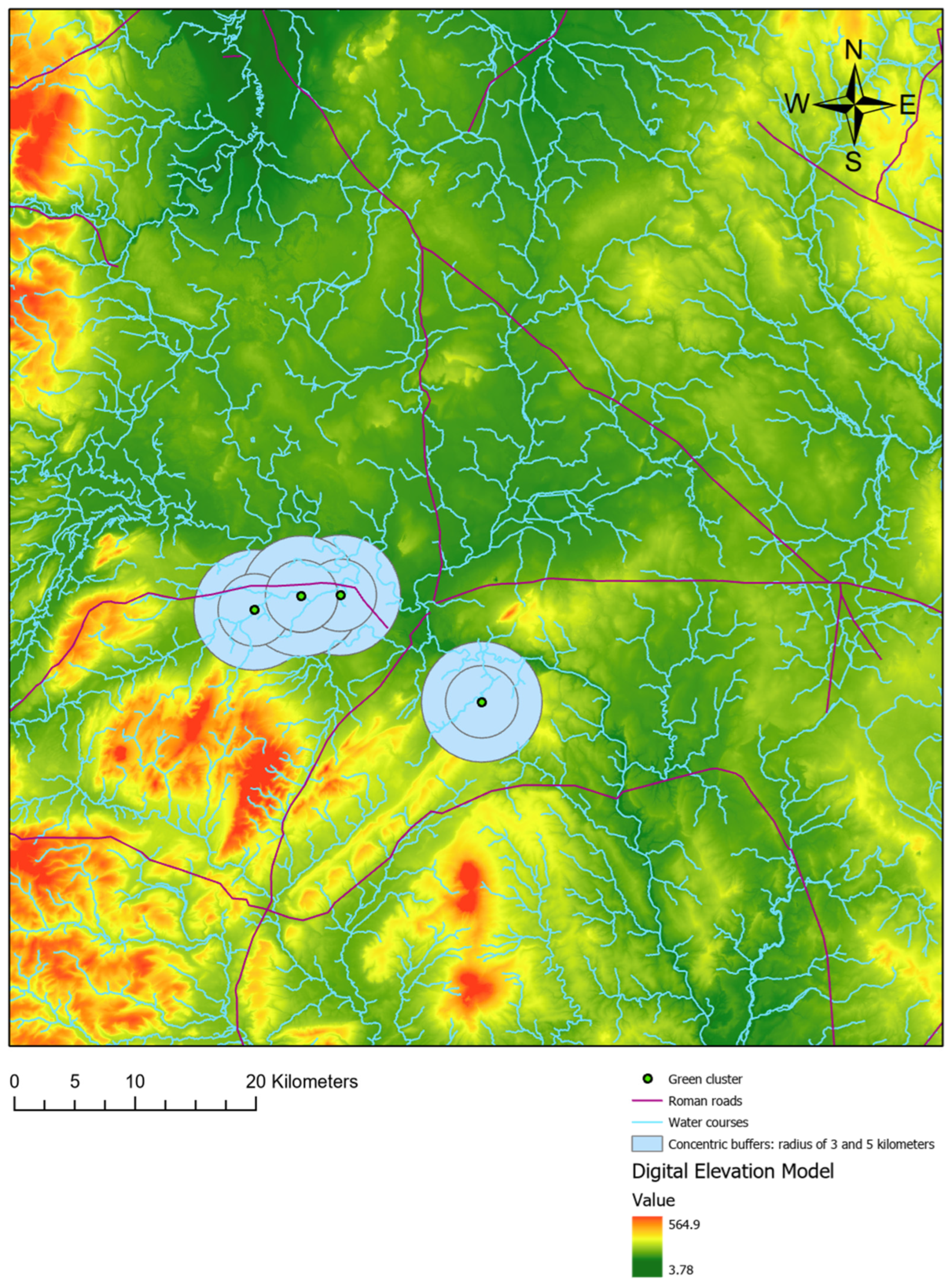

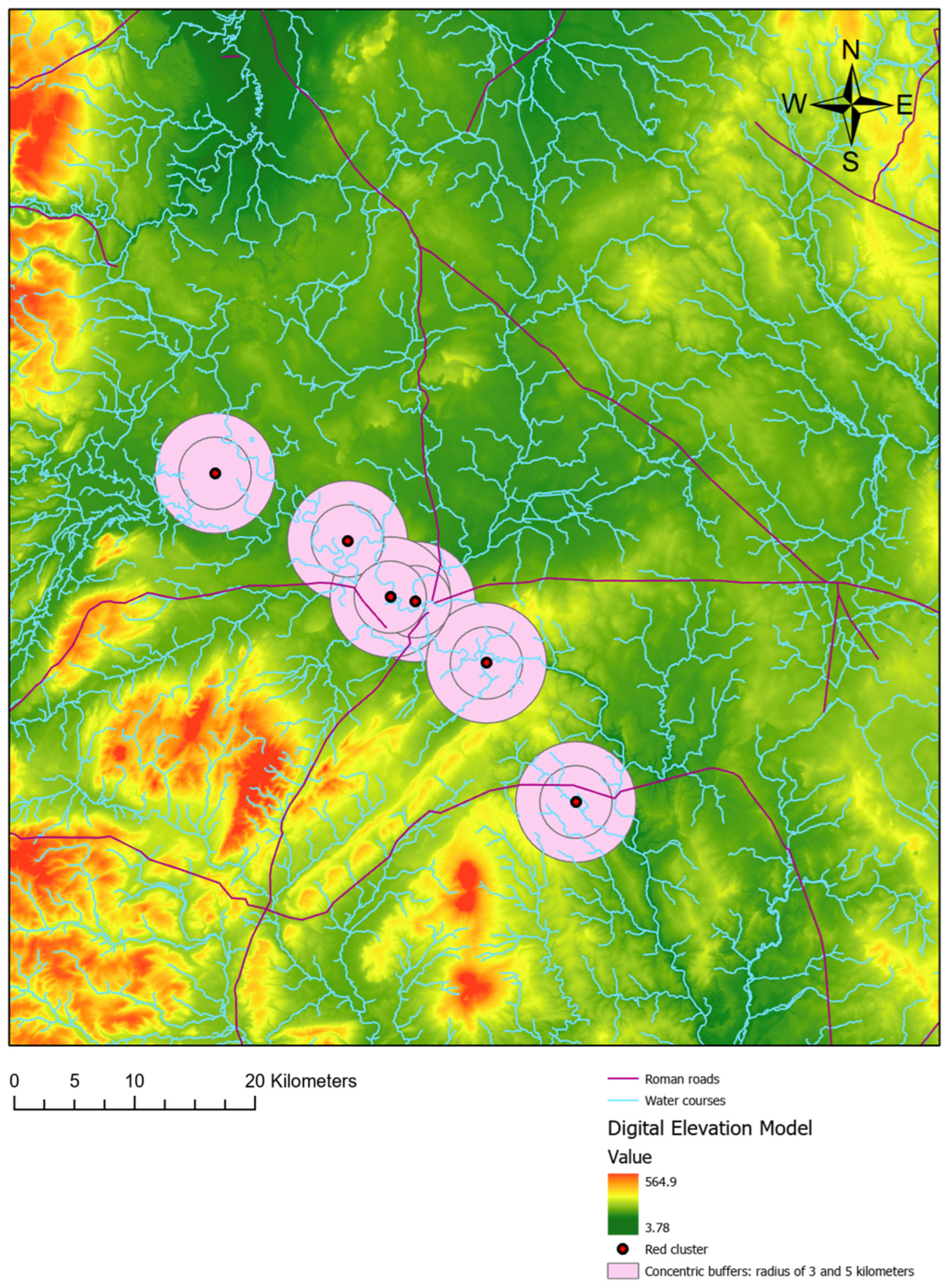

3.2. Site Catchment Analysis

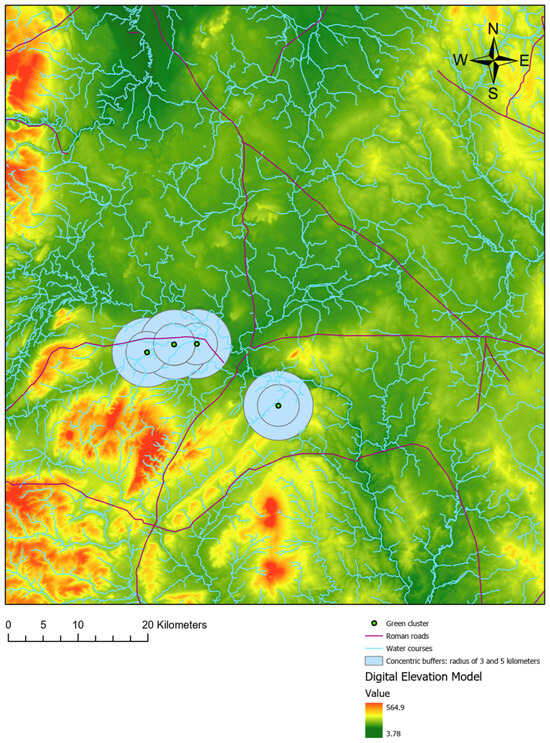

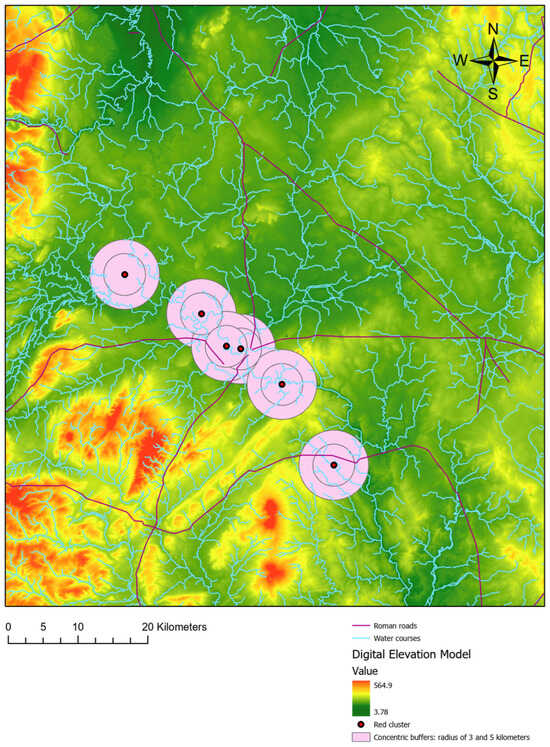

The results of the catchment analysis revealed that sites from the Earlier Roman period are generally located near watercourses, as expected for rural settlements. They are also situated close to ancient Roman roads, suggesting that these roads served as an important network for communication and possibly trade within the landscape (see Figure 6). Similar patterns were observed for the sites categorised as Identities 2 and 3 in the Later Roman period (see Figure 7 and Figure 8). With few exceptions, most of these settlements are positioned near both Roman roads and watercourses, indicating that roads were a key feature of connectivity across identities and periods.

Figure 6.

Site catchment analysis for Identity 1: Earlier Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 7.

Site catchment analysis for Identity 2: Later Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 8.

Site catchment analysis for Identity 3: Later Roman, Shropshire.

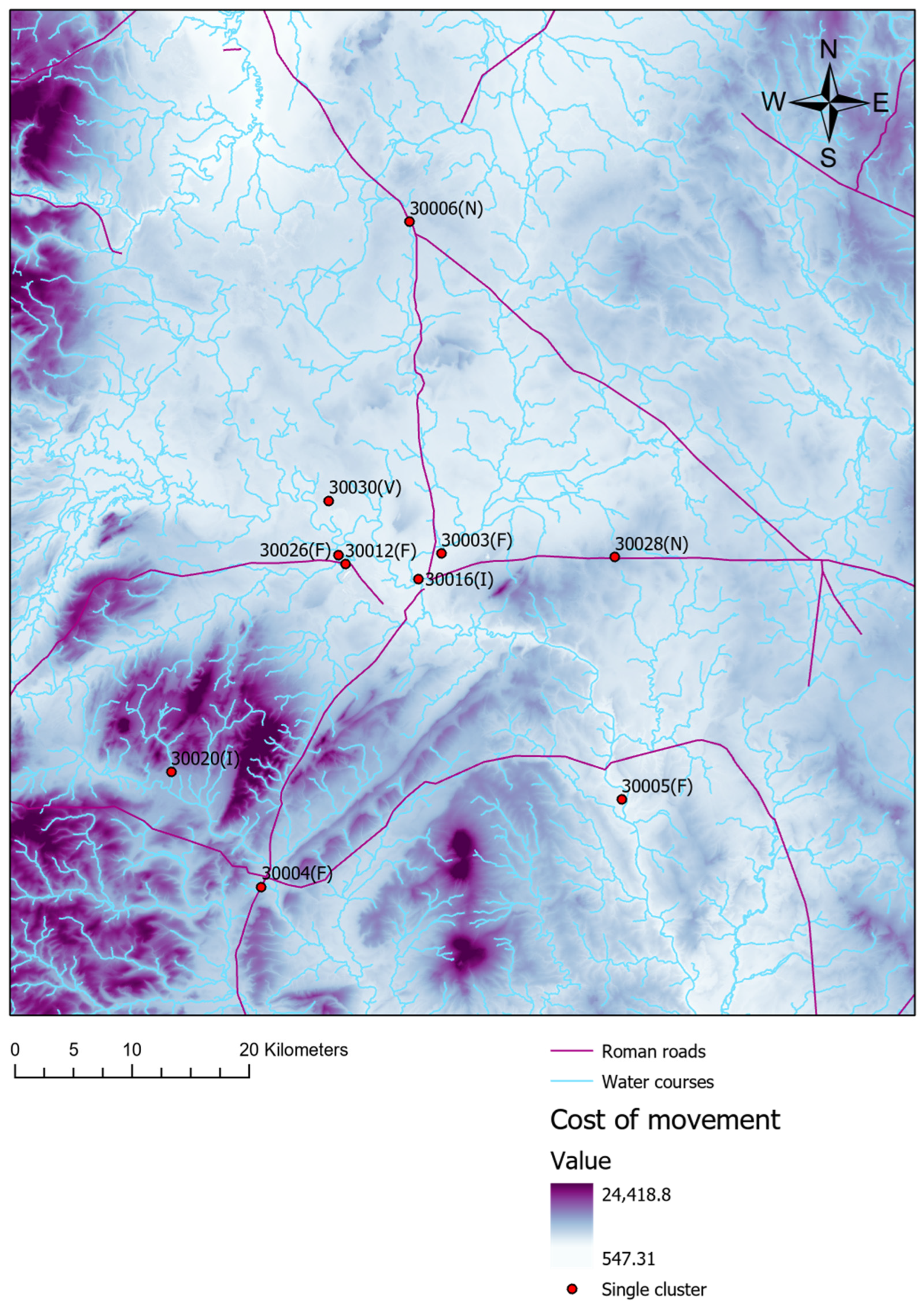

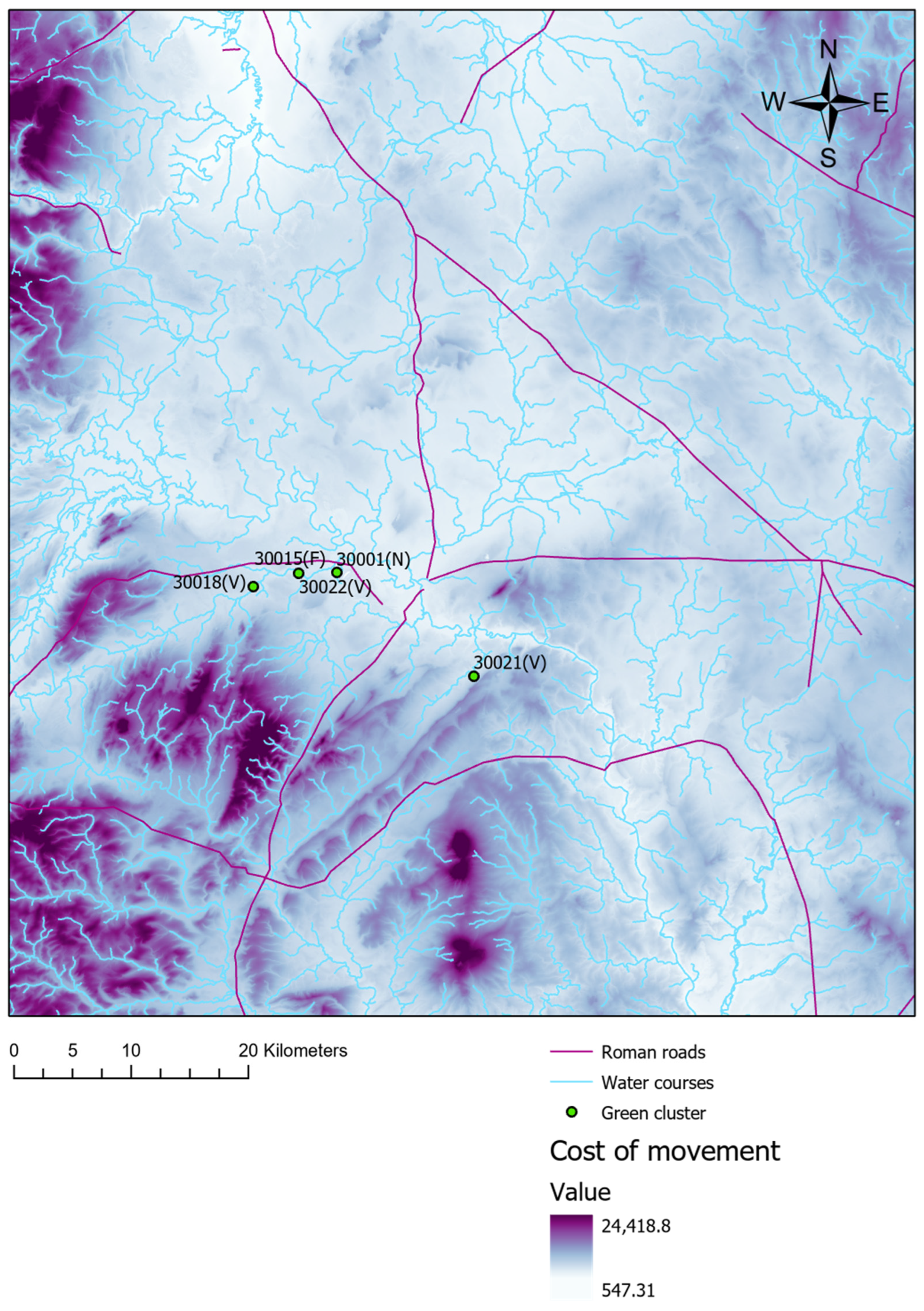

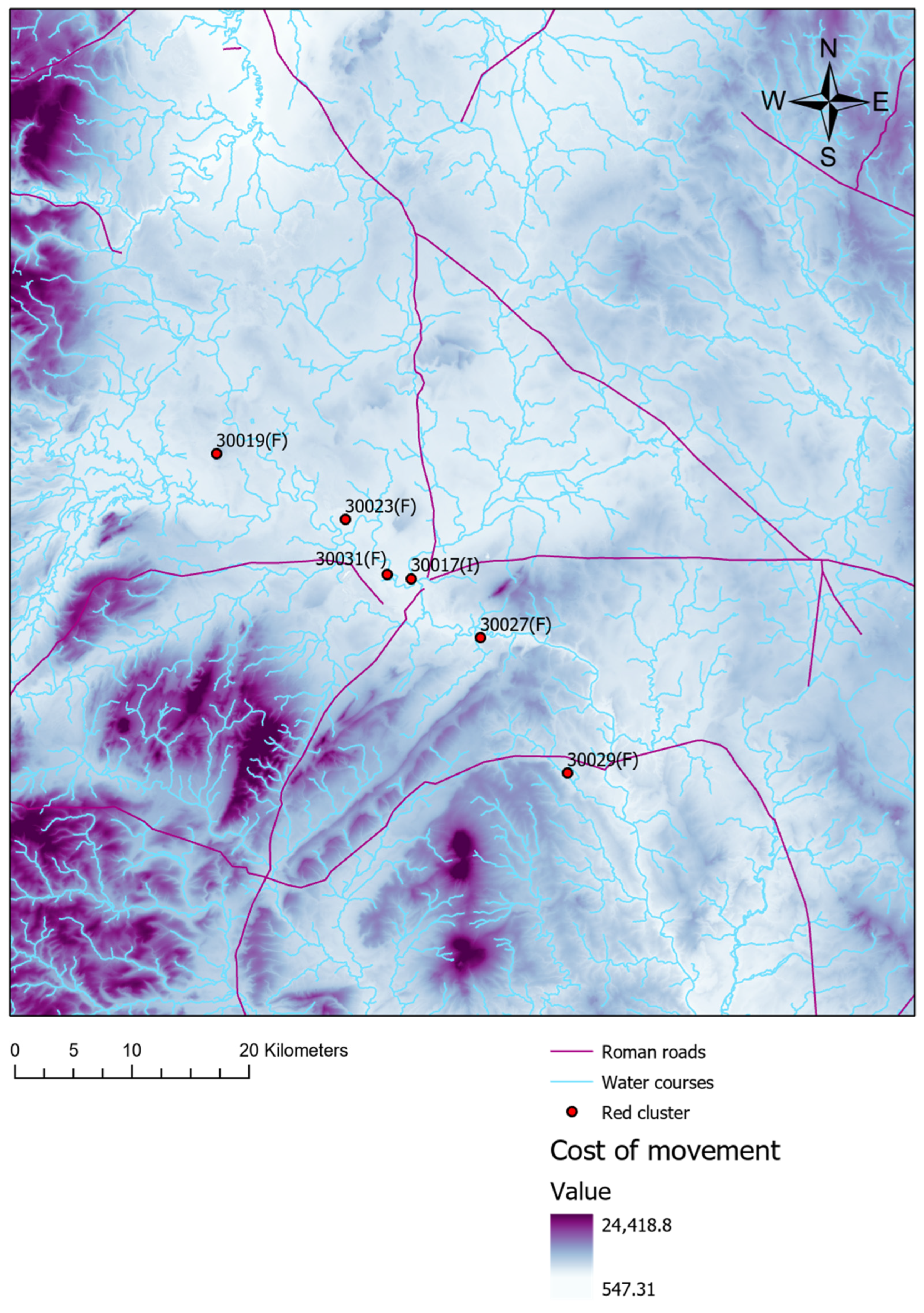

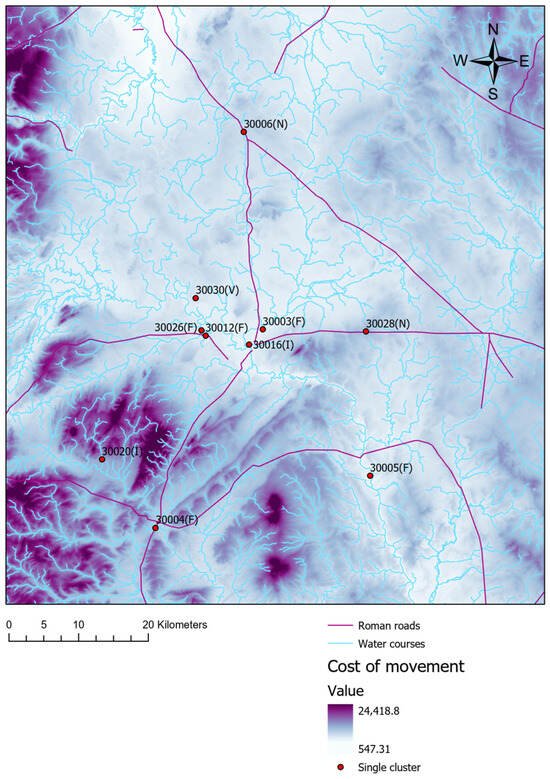

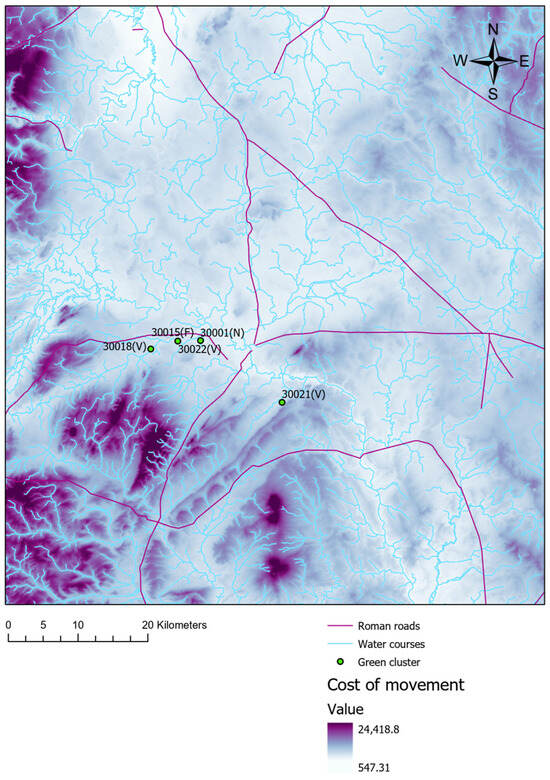

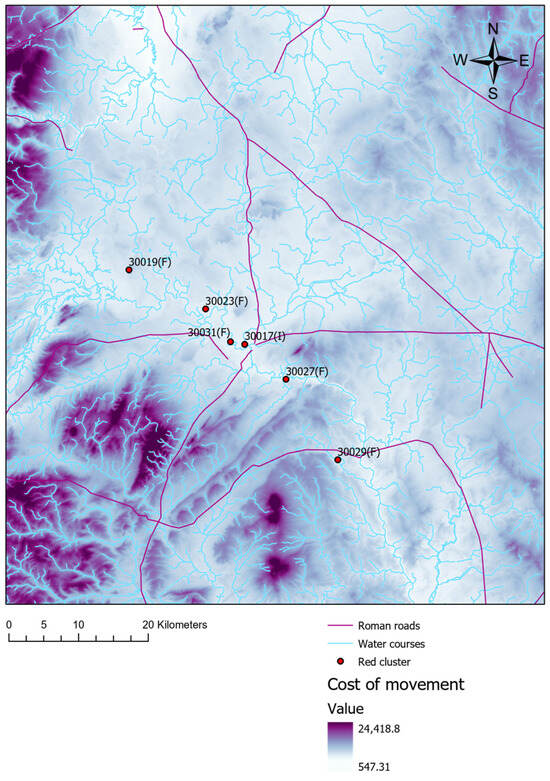

3.3. Cost of Movement on Land

Regarding the cost of movement on land, Figure 9 shows that most sites from the Earlier Roman period are located in areas with low movement costs, suggesting that inhabitants preferred to settle in locations requiring minimal physical effort. There are, however, exceptions such as the site at Linley Hall, which is associated with an industrial activity. Similarly, all sites from the Later Roman period are situated in areas of low movement cost (Figure 10 and Figure 11). These findings indicate that, regardless of cultural identity, people in Roman Shropshire consistently chose to occupy easily accessible areas to reduce physical exertion.

Figure 9.

Cost of movement on land for Identity 1, Earlier Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 10.

Cost of movement on land for Identity 2, Later Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 11.

Cost of movement on land for Identity 3, Later Roman, Shropshire.

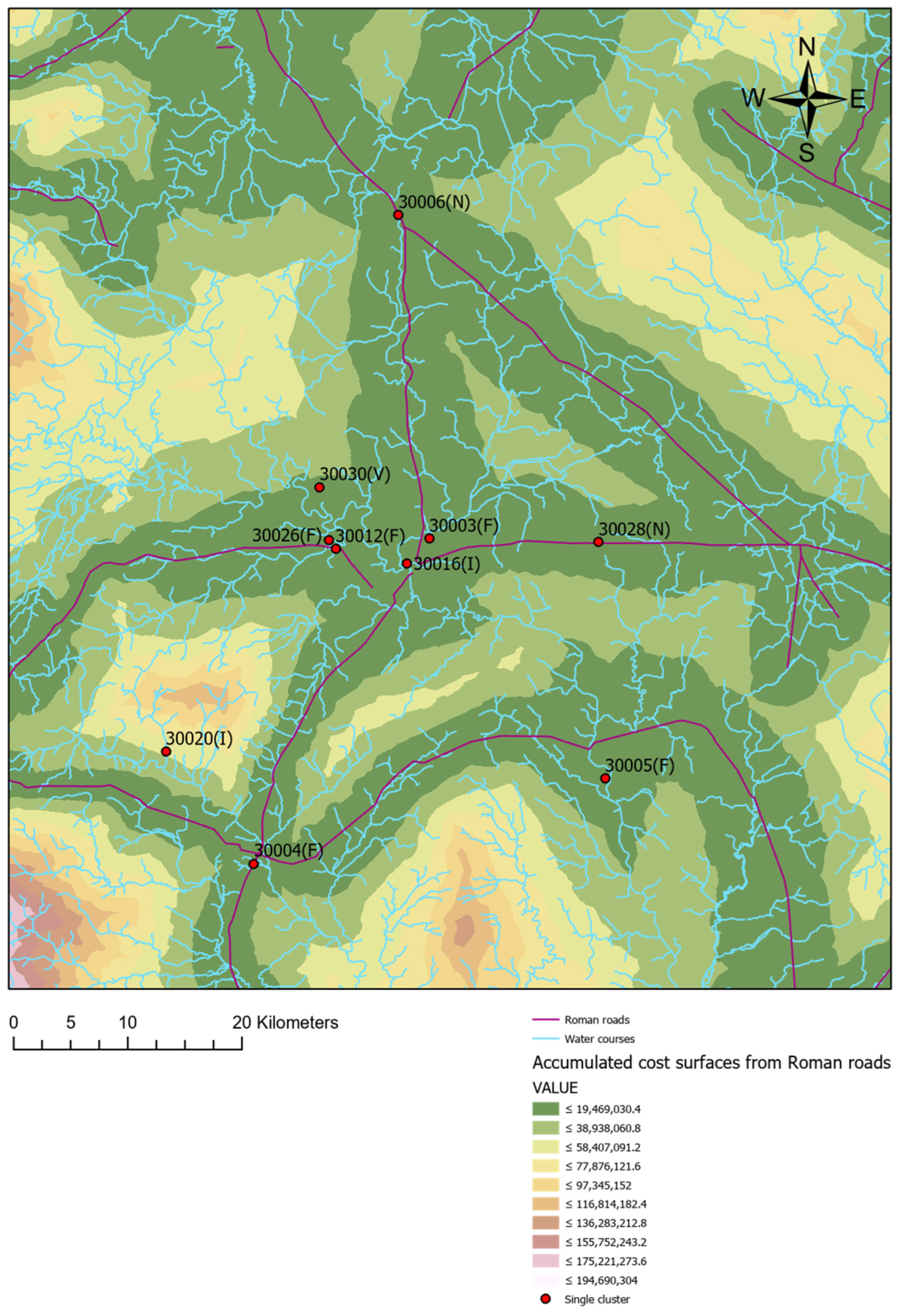

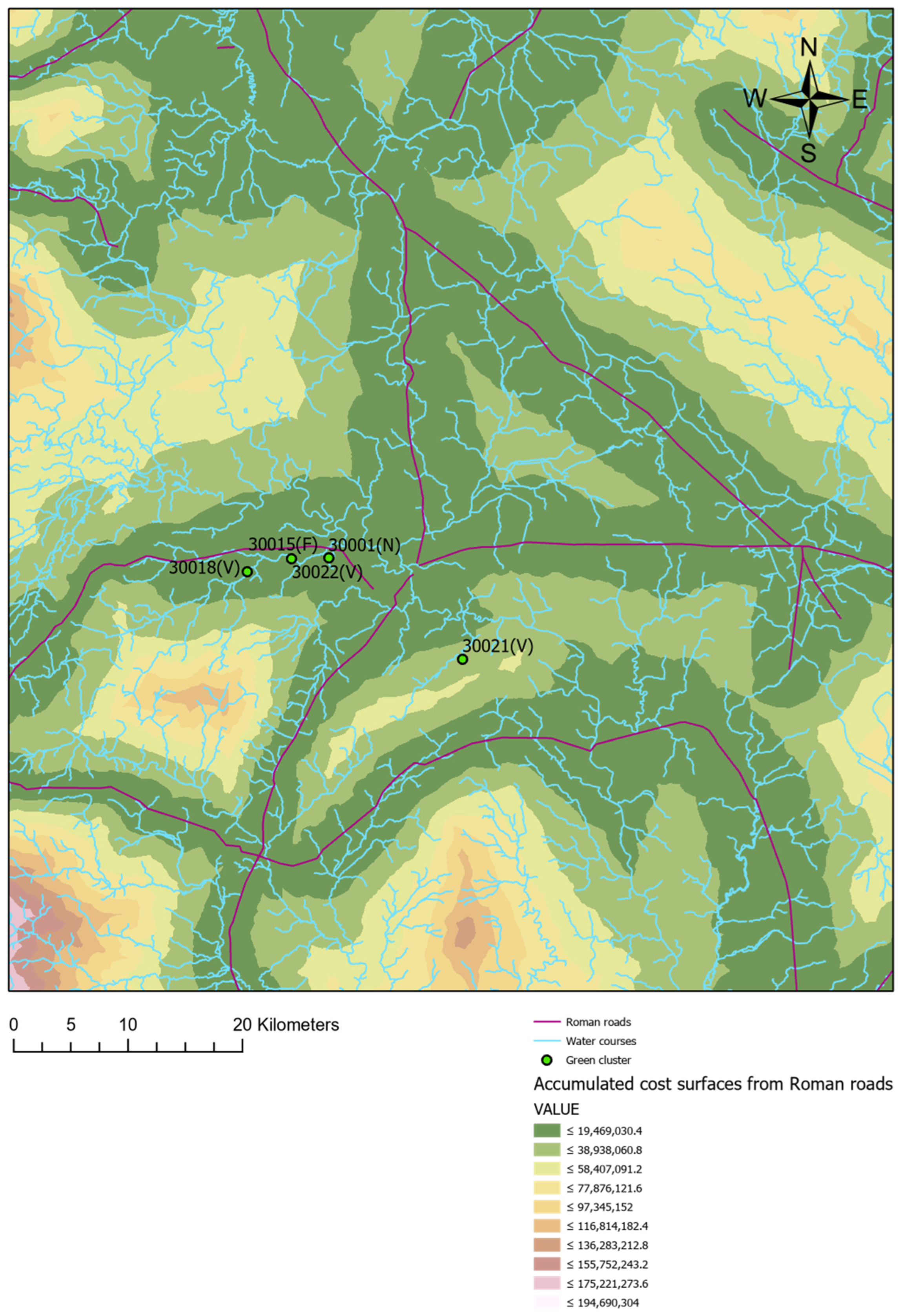

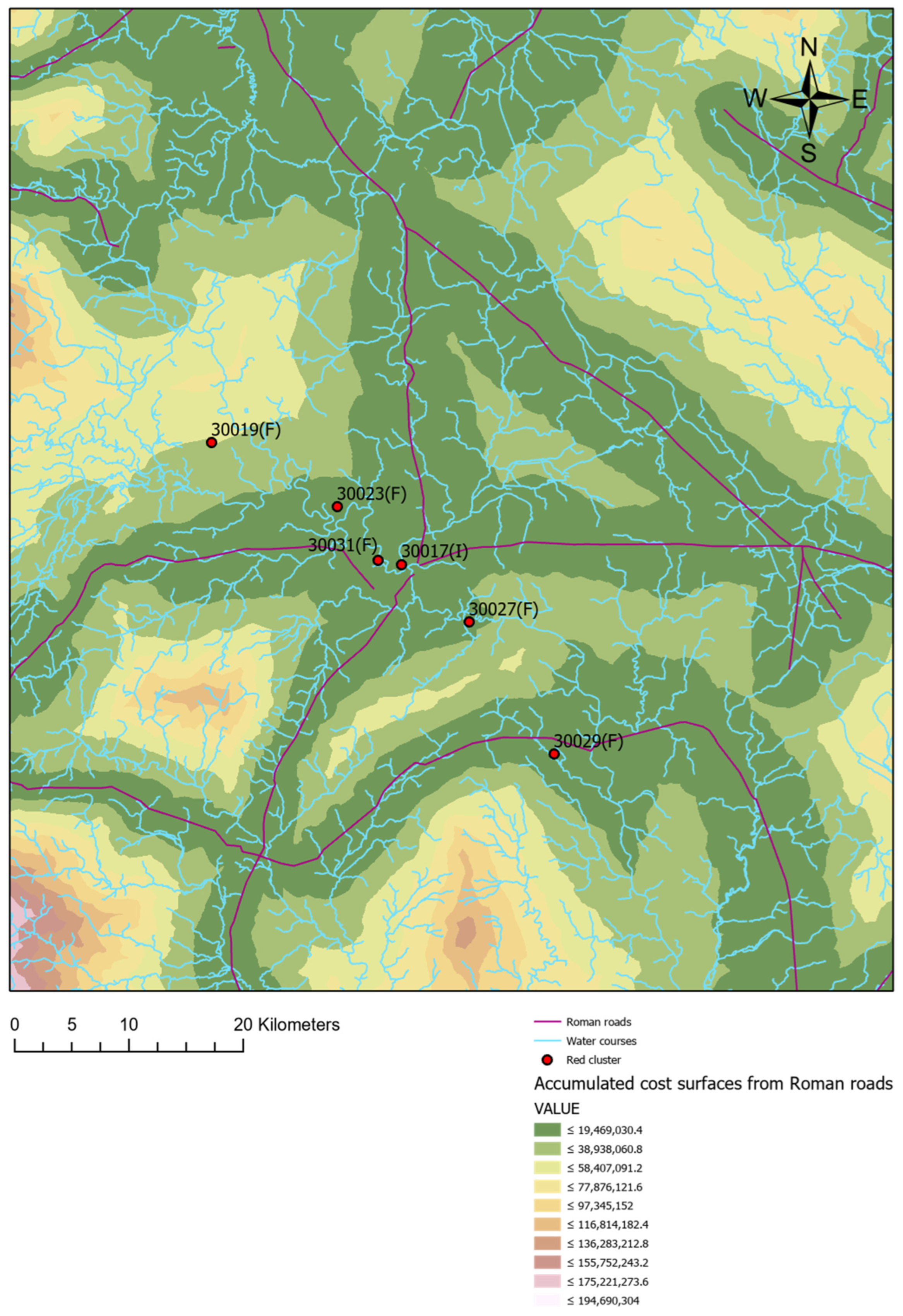

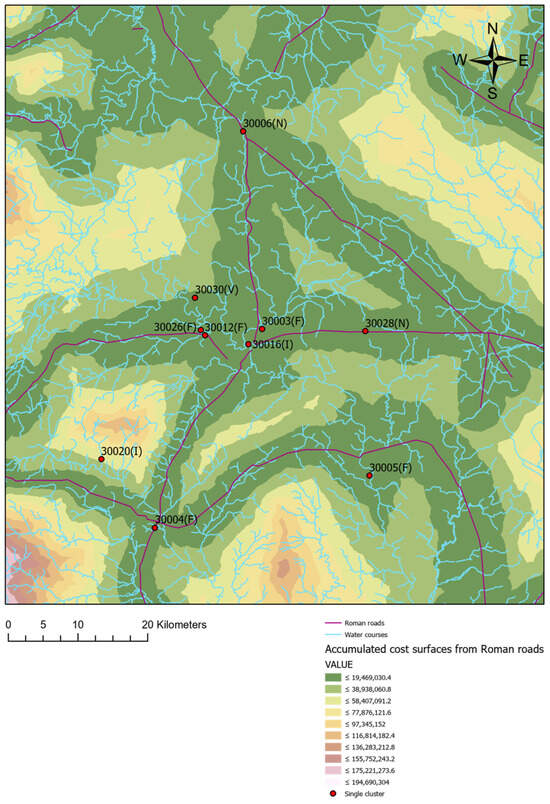

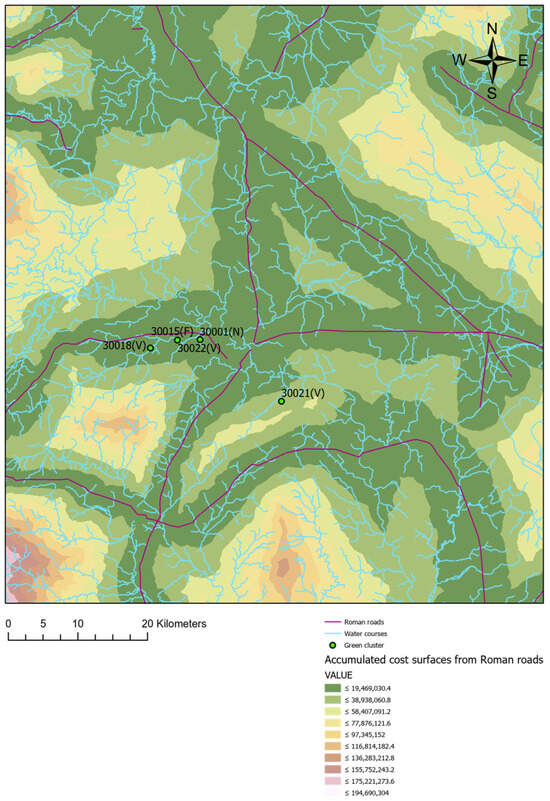

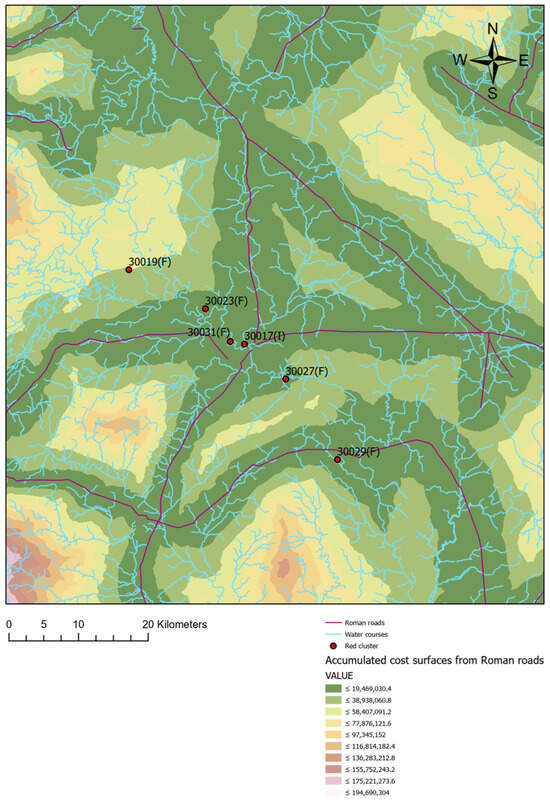

3.4. Least Cost Path from Roman Roads

The results show that all sites in the study are located in areas of low accumulated movement cost from Roman roads (see Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14). This pattern holds even for sites situated more than 5 km away from Roman roads (see the catchment analysis above) and for those located in areas with higher movement costs (see the cost of movement on land analysis above). These findings suggest that proximity to Roman roads or being in areas of low accumulated energy expenditure were key factors influencing the distribution of the sites in the sample.

Figure 12.

Least cost path analysis for Identity 1, Earlier Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 13.

Least cost path analysis for Identity 2, Later Roman, Shropshire.

Figure 14.

Least cost path analysis for Identity 3, Later Roman, Shropshire.

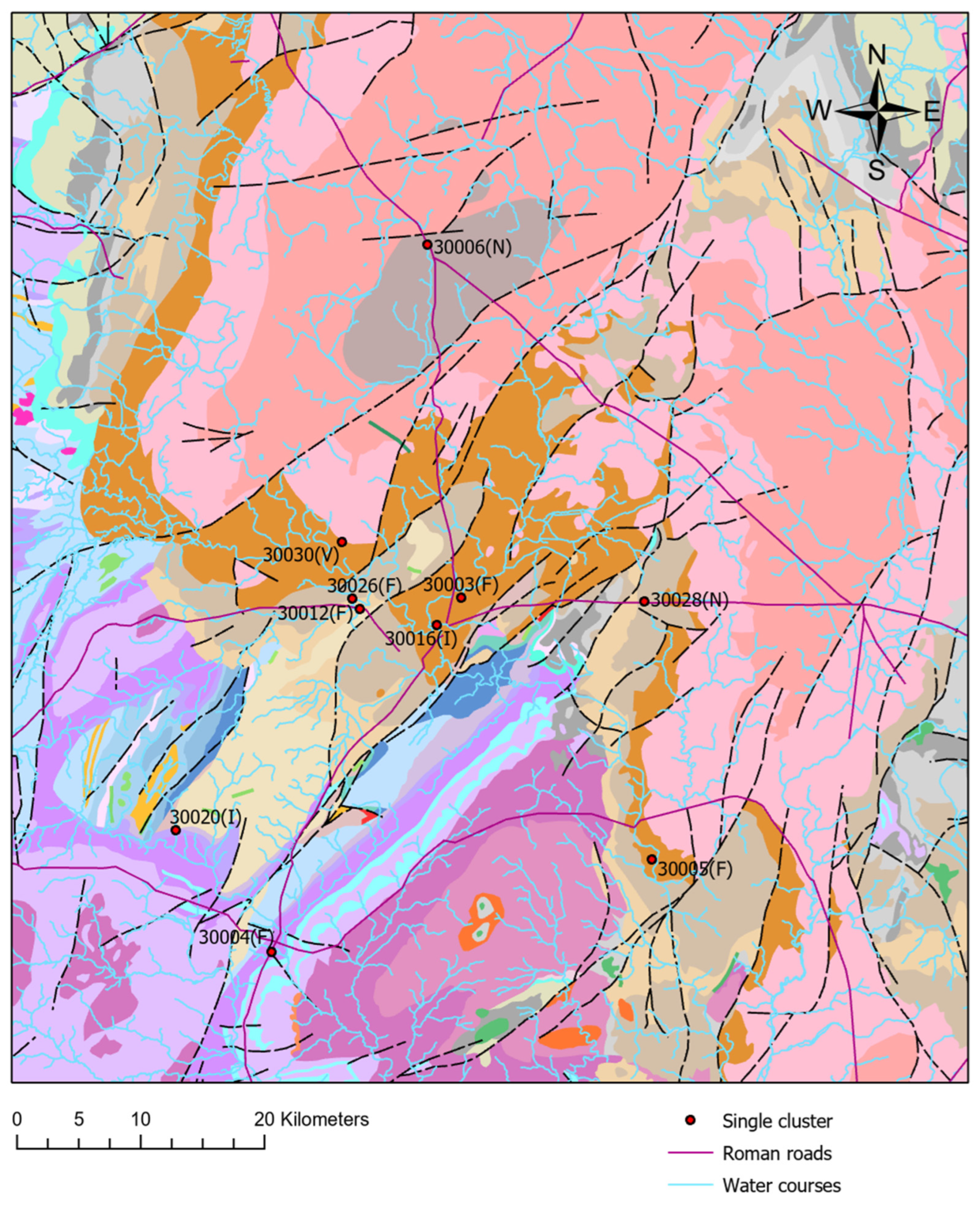

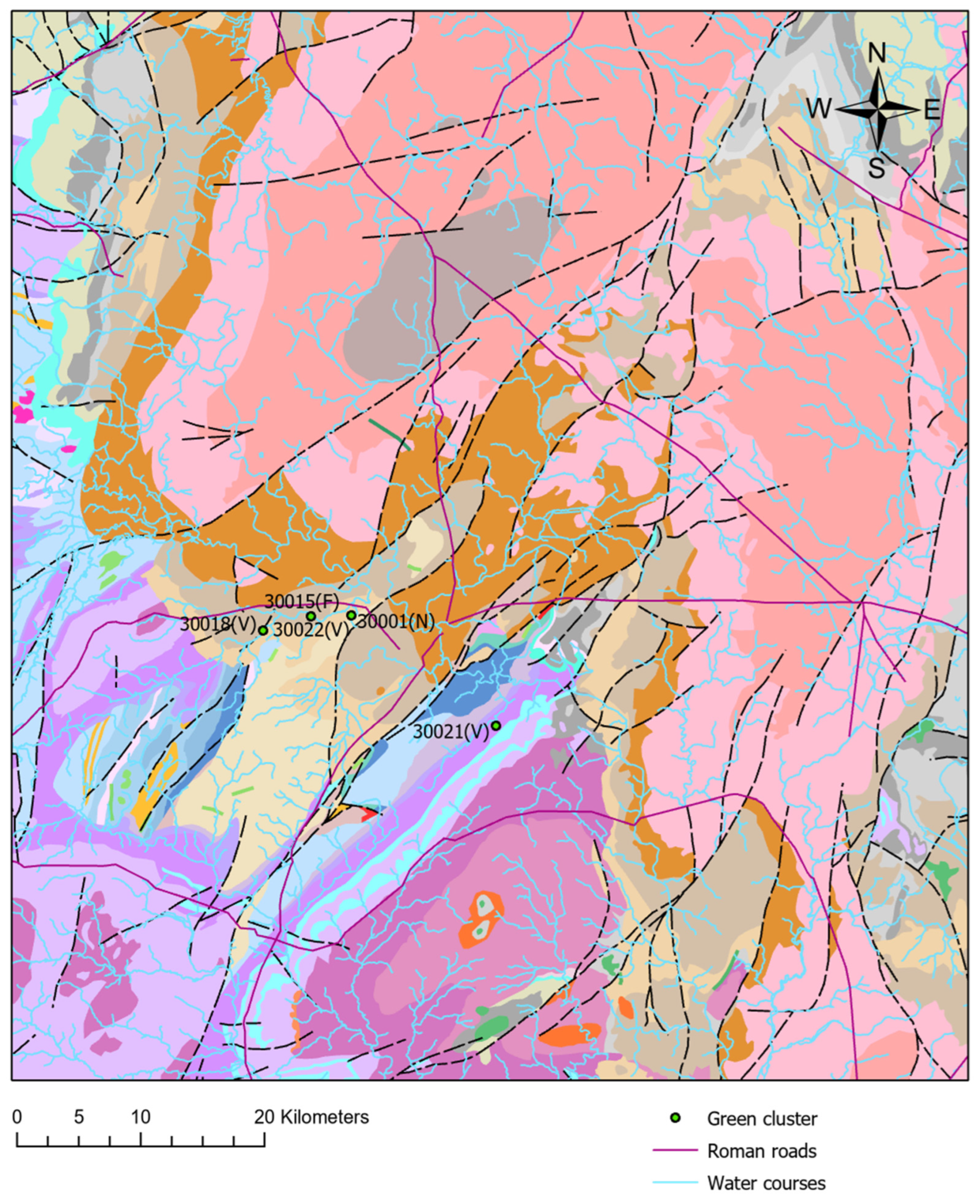

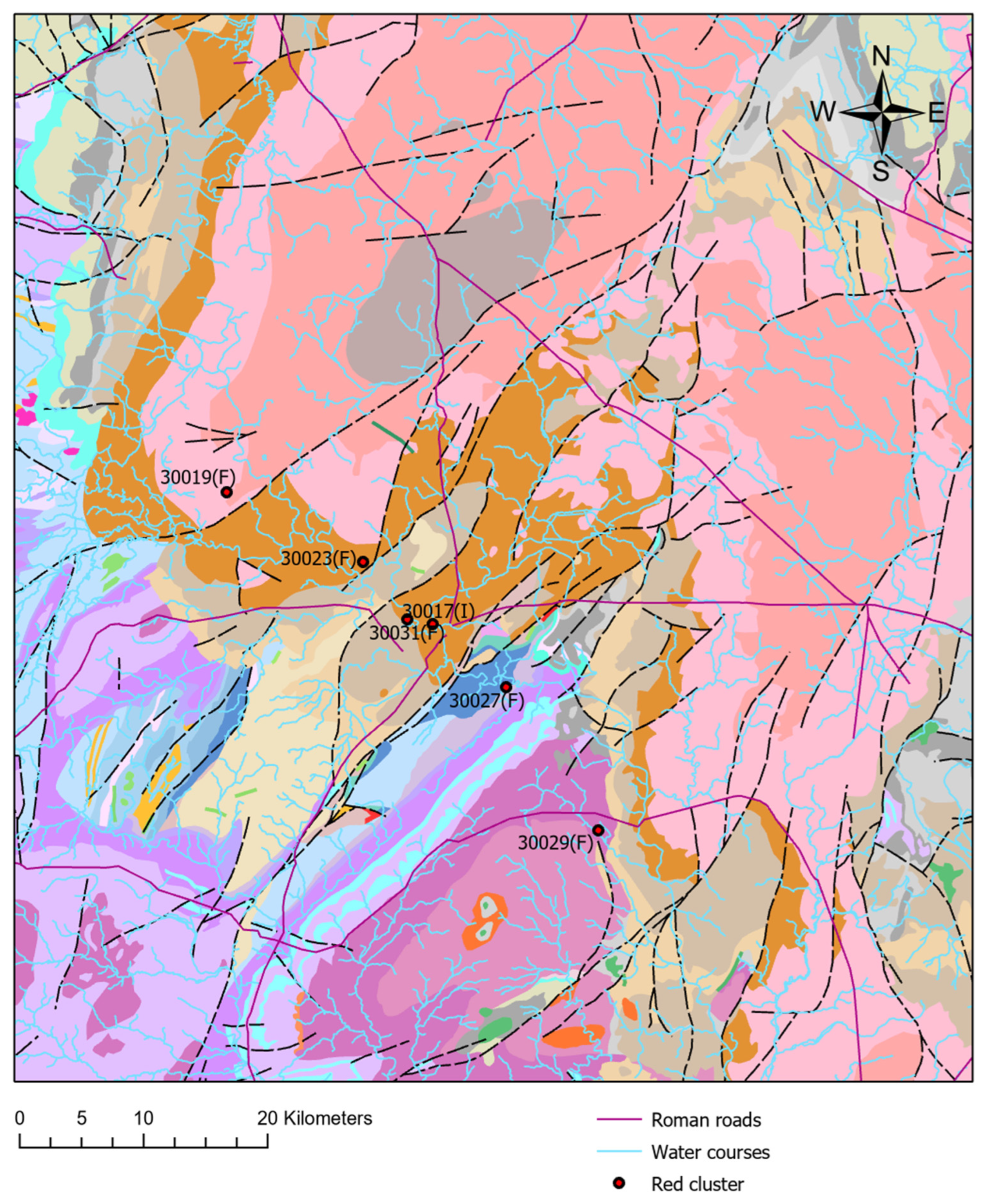

3.5. Bedrock Geology

Although Shropshire has a wide variety of bedrock types (see Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17), the sampled sites are located in only a few of these, as shown in the following table (Table 2).

Figure 15.

Earlier Roman period. Bedrock and Identity 1, Shropshire.

Figure 16.

Later Roman period. Bedrock and Identity 2, Shropshire.

Figure 17.

Later Roman period. Bedrock and Identity 3, Shropshire.

Table 2.

Relevant bedrock types.

According to this table, most of the sites from both the Earlier and Later Roman periods are concentrated in only two bedrock types: Permian rocks and the Warwickshire group. Building materials have historically been extracted from these types, particularly during Medieval times [55,56]. Although it is less clear whether these materials were used for construction in Shropshire during the Roman period—given the low proportion of sites with stone building structures—it remains a possibility.

The concentration of sites in specific bedrock types, and the possible resources that could have been extracted from them, cannot explain the nature of the clusters or their identities. As shown in the figures above, the sites within each cluster are generally located on different bedrock types. Therefore, bedrock geology can be ruled out as a factor related to the diversity of identities.

3.6. Superficial Geology

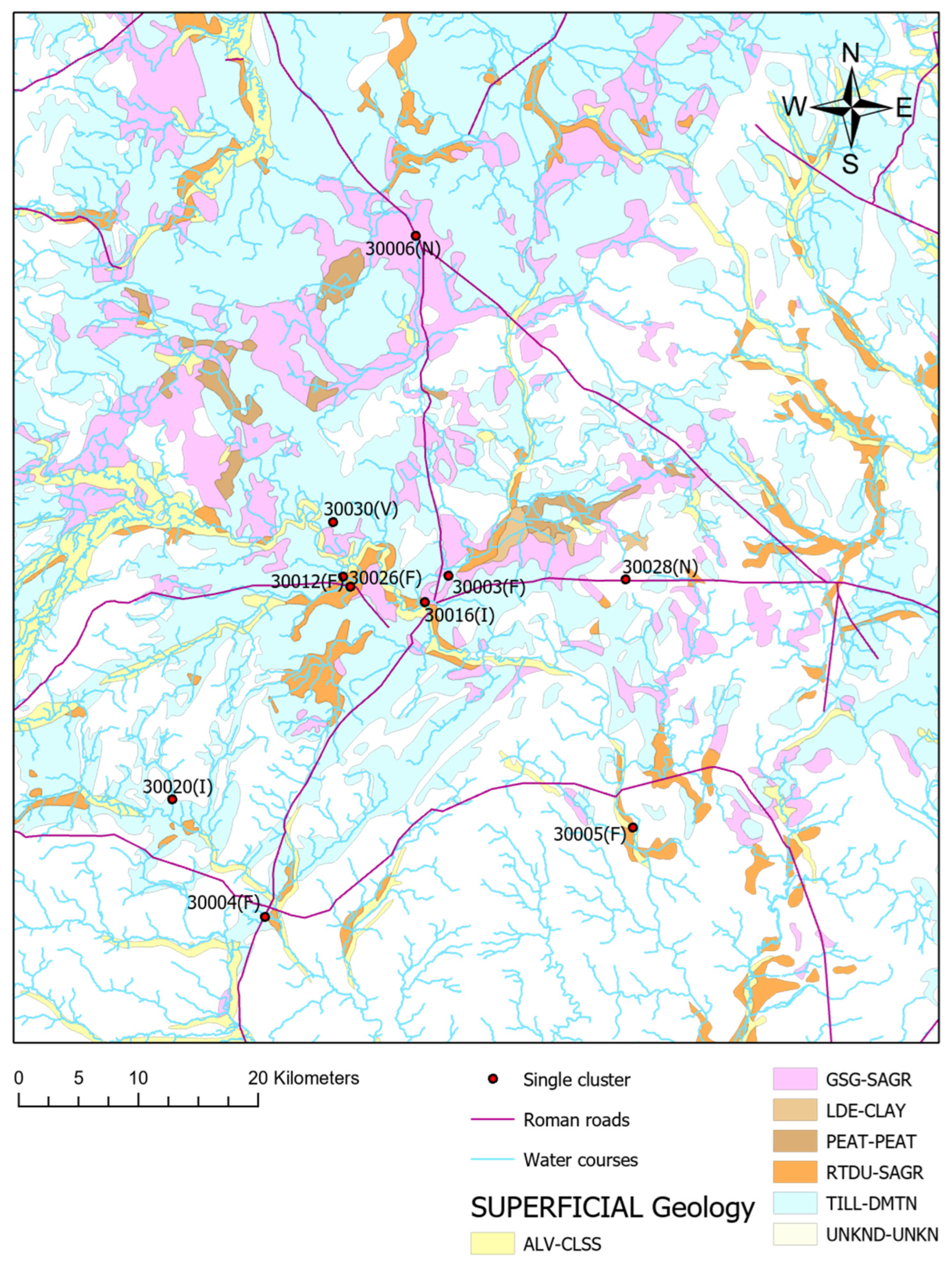

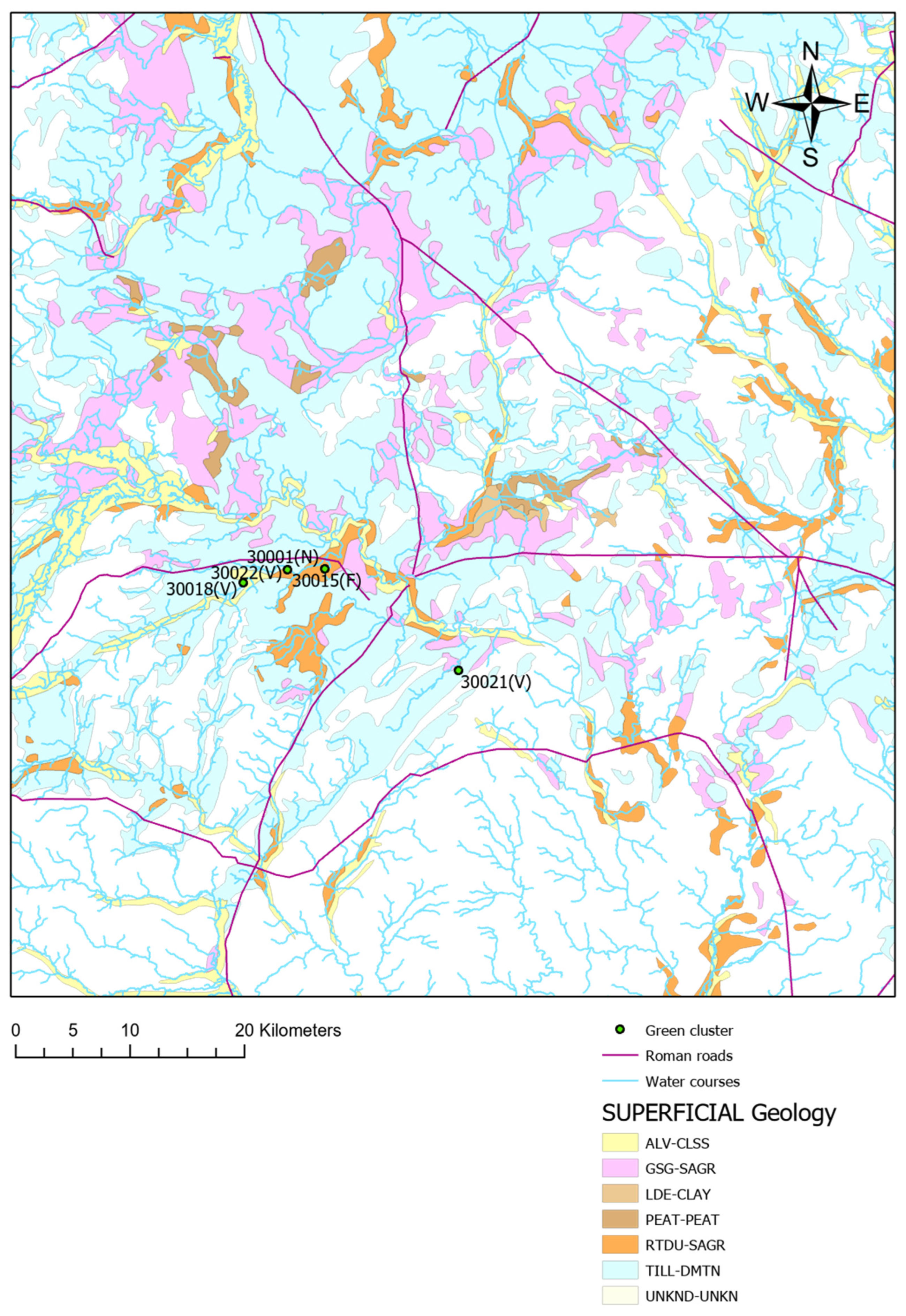

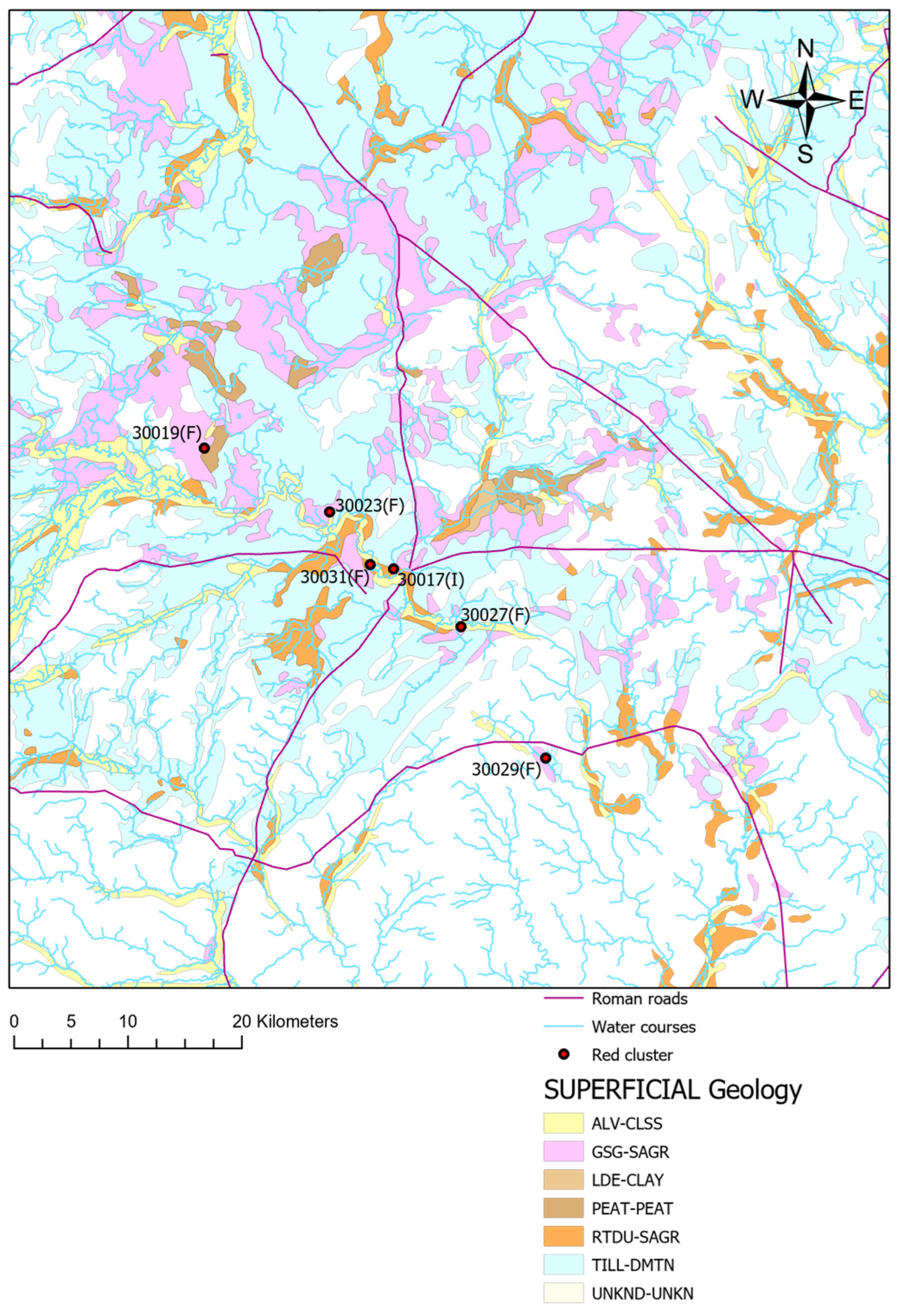

The results of this analysis are summarised in Table 3, which shows the proportion of sites located within different superficial deposit types.

Table 3.

Relevant bedrock types for the ECMNMs.

According to the table, most sites in both periods are located in river terraced deposits and till deposits. Despite this concentration, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20 show that, in general, sites within a cluster are situated on different superficial deposits. This implies that this variable alone cannot explain the nature of the clusters and, consequently, the possible diverse identities associated with them.

Figure 18.

Earlier Roman period. Superficial deposits and Identity 1, Shropshire.

Figure 19.

Later Roman period. Superficial deposits and Identity 2, Shropshire.

Figure 20.

Later Roman period. Superficial deposits and Identity 3, Shropshire.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The main results from the analyses can be summarised as follows. First, no association was found between site identity and factors such as visibility, movement costs across the land, bedrock geology, or superficial deposit geology. Second, proximity to watercourses and Roman roads—or areas with low cumulative movement costs from these roads—appear to be the primary geographical factors influencing site distribution in this study. However, since these factors apply to all sites in the sample, they do not explain the formation of clusters. Therefore, geographical and geological factors cannot be linked to distinct identities.

These results reaffirm the rural character of these Romano-British sites while highlighting the value of using replicable, quantitative methods to critically test existing hypotheses. Although the results show no significant effects, this outcome is important as it clarifies the constraints of applying intervisibility and network analysis to this particular settlement pattern, providing insights that can improve future methodological frameworks.

Extending analysis beyond the immediate site surroundings to a regional scale reveals structured, non-random spatial patterns that are intricately connected to wider environmental and cultural contexts. At this broader scale, landscape-scale relationships emerge, such as clustering around areas of religious significance and delineations along cultural boundaries, patterns that remain obscured at smaller, localised scales. This regional perspective enriches the understanding provided by May’s micro-scale study [19] by incorporating a landscape-wide dimension, thereby reinforcing foundational theories proposed by Sauer and Hoskins [3,4], which conceptualise cultural landscapes as products of interconnected environmental and social influences.

The integration of regional-scale insights aligns with empirical findings from studies in Roman Britain, which underscore the importance of topographical and hydrological factors in shaping site distribution [32,33]. By highlighting these landscape-wide spatial distributions and their relation to cultural identity and social organisation, this approach advances scholarly comprehension of how ancient communities constructed their identities and structured their social environments within specific geographic contexts.

Such an integrated methodological framework underscores the value of analysing cultural landscapes through a multi-scalar lens—from local site-specific details to broader regional patterns—thereby providing a more holistic understanding of the dynamic interplay between environment, culture, and social structure in historical geographies. This narrative situates the present findings within ongoing scholarly dialogues, illustrating how landscape and regional analyses complement micro-scale research to construct a nuanced picture of ancient cultural landscapes.

In considering these results alongside those obtained by May, the following conclusions can be drawn. During the Earlier Roman period, a single cultural identity occupied the Shropshire region. This identity consisted mainly of sites with little evidence of material culture, except for some that showed partial Roman influence. These latter sites tend to be located in areas with good local visibility, possibly to signal wealth, status, and territorial control or to oversee slaves and tenants working nearby. However, when examining settlement patterns at a broader regional scale, this emphasis on visibility appears less important. Instead, the distribution of sites during this period seems to have been influenced by practical considerations such as ease of movement, proximity to watercourses (likely for consumption and agricultural purposes), and low-energy access to Roman roads.

This latter factor is particularly relevant because it indicates that sites from this period were connected by a network of roads. These roads likely served not only for transit but also for commerce. This is plausible because recent studies have revealed that people in Roman-era Shropshire exhibited a level of sophistication comparable to other groups in the country—for example, they developed metal roads and participated in extensive trade networks. Given the large number of farmsteads in the region, it is argued that the native population occupied fertile arable lands, enabling them to produce surplus food to sustain a large population [39].

Similar observations apply to identities in the Later Roman period. While local visibility appears relevant for the wealthy identity 2 at a small scale, it is not significant at a larger scale. Furthermore, the patterns identified in the Earlier Roman period are also evident in the Later Roman period: factors such as low cost of movement, easy access to Roman roads, proximity to these roads, and closeness to watercourses seem to have influenced people in Shropshire regardless of their identity. This suggests that expressions of identity are identifiable primarily at the site level and in the immediate surrounding landscape. At a broader scale, however, all sites appear to have been strategically organised to secure access to agricultural lands and to integrate into an extensive network of roads facilitating transit, trade, and commerce.

Regarding bedrock, the majority of the sites in both periods are located on Permian-type rocks and the Warwickshire Group. Permian rocks were important in Roman times because they provided local building materials. Similarly, the Warwickshire Group bedrock was economically significant in Roman Britain, supporting mineral extraction and offering terrain suitable for strategic infrastructure critical to Roman military and administrative control [57,58]. It is unclear whether the sites were specifically placed on these bedrocks for these purposes, as that information is not available. However, it is evident that the availability of these resources does not appear to be linked to expressions of identity. On the contrary, it seems that all identity groups in the region were aware of the useful resources available across the Shropshire landscape.

Finally, with regard to superficial deposits, the majority of sites in both periods are located in river terraced and till deposits. River terraced deposits were commonly exploited in Roman Britain as important sources of raw materials for construction and road building. Rivers themselves were key arteries for transportation, trade, and communication linked to these waterways. Regarding till deposits, their chalky and clay-rich composition influenced land usability and the distribution of settlements across the landscape, as these properties were beneficial for agriculture [59,60]. In considering this evidence, it is possible that people in Shropshire in Roman times selected these types of land given their beneficial properties for agriculture and for raw materials.

This article finishes by acknowledging an important limitation of the research. As noted by May [19], the sample used in this investigation is small, which may introduce some bias. Unfortunately, obtaining a larger sample was not possible because other sites in the database contain incomplete or inconsistent data. Future work could address this issue by considering additional regions within the UK or by analysing several regions simultaneously.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight the complexity of interpreting social behaviours such as regular meetings and identity formation within the archaeological record. Indeed, these aspects are challenging to reconstruct directly due to the fragmentary nature of the available evidence. The primary objective of this study was to explore large-scale patterns in settlement distribution and potential identity markers through indirect spatial analysis tools like ArcGIS, which offer a means to generate hypotheses where direct archaeological or historical information is lacking.

We acknowledge that the effectiveness of GIS-based analyses is inherently dependent on the quality, resolution, and contextual understanding of the input data, and the current sample size and temporal breadth present certain limitations. Furthermore, we agree that factors such as landownership, socio-political organisation, and nuanced site functions are critical variables that should be integrated to refine interpretations, but such data are often unavailable or insufficiently detailed for the sites considered here.

Despite these constraints, the application of spatial analysis in this study has yielded valuable preliminary insights into settlement distributions and possible identity dynamics at a landscape scale. We consider this work a foundational step that highlights the potential of combining GIS with archaeological data while recognising that a comprehensive understanding of social interactions and identity formation will require further multidisciplinary research incorporating more detailed site-specific information and broader datasets in future studies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this research is available in the following links: https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-government/products/terrain-5 (accessed on 7 March 2023). https://www.bgs.ac.uk/datasets/bgs-geology-625k/ (accessed on 7 March 2023). https://www.data.gov.uk/dataset/9bec0be4-c552-4769-b6dc-4073d1de9f46/bgs-geology-625k-digmapgb-625-superficial-version-4 (accessed on 7 March 2023). https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/romangl/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Wieruszewska, M. Rural landscape as a value of cultural heritage. Wieś Rol. 2016, 4, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, F.; Martin, J.; De Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Zalama Casanova, E. Computational methods and rural cultural & natural heritage: A review. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 49, 250–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins, W.G. The Making of the English Landscape; Hodder and Stoughton: London, UK, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape. Univ. Calif. Publ. Geogr. 1925, 2, 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D. Cultural Landscape Conservation in China Today. Landsc. Res. Jpn. J. Jpn. Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2016, 80, 59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K. New lives, new landscapes. Landscape, heritage and rural revitalisation: Whose cultural values? Built Herit. 2019, 3, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupidura, A. The role of landscape heritage in integrated development of rural areas in the context of “landscape legal regulation”. Infrastrukt. Ekol. Teren. Wiej. 2017, III, 869–878. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, I.A.; Sofer, M. Integrated rural heritage landscapes: The case of agricultural cooperative settlements and open space in Israel. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, G. Landscape and heritage: Ideas from Europe for culturally based solutions in rural environments. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentz, M.; Albert, N. Cultural Landscapes as Potential Tools for the Conservation of Rural Landscape Heritage Values: Using the Example of the Passau Abbey Cultural Site. Mod. Geográfia 2023, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, J.; Knippenberg, L. The Heritage of the Productive Landscape: Landscape Design for Rural Areas in the Netherlands, 1954–1985. Landsc. Res. 2008, 33, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scazzosi, L. Rural landscape as heritage: Reasons for and implications of principles concerning rural landscapes as heritage ICOMOS-IFLA 2017. Built Herit. 2018, 2, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, S.; Bruckmann, L. The quest for new tools to preserve rural heritage landscapes. Doc. D’anàlisi Geogràfica 2020, 66, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHC (World Heritage Centre). Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, I.J.M. Hardscrabble Heritage: The ruined blackhouse and crofting landscape as heritage from below. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrastina, P.; Hronček, P.; Gregorová, B.; Žoncová, M. Land-Use changes of historical rural landscape—Heritage, protection, and sustainable ecotourism: Case study of Slovak Exclave Čív (Piliscsév) in Komárom-Esztergom County (Hungary). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekakis, S.; Dragouni, M. Heritage in the Making: Rural Heritage and Its Mnemeiosis at Naxos Island, Greece. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossitti, M.; Oppio, A.; Torrieri, F. The Financial Sustainability of Cultural Heritage Reuse Projects: An Integrated Approach for the Historical Rural Landscape. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.E. Mixed Methods in Landscape Archaeology: An Application to Explore Identity Formation in the Romano-British Period, Shropshire Region. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2024, 19, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. Social Identity; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, H. Objects and Identities: Roman Britain and the North-Western Provinces; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, E. Roman Artefacts and Society: Design, Behaviour and Experience; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Millett, M. By small things revealed: Rural settlement and society. In The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain; Millett, M., Revell, L., Moore, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 699–720. [Google Scholar]

- Herrle, P. Architecture and Identity? Herrle, P., Wegerhoff, E., Eds.; Deutsche National Bibliothek: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Allason-Jones, L. Artefacts in Roman Britain; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, I. Roman Britain Through Its Objects; Amberley Publishing: Amberley, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J. Status and burial. In The Oxford Handbook of Roman Britain; Millett, M., Revell, L., Moore, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 341–362. [Google Scholar]

- Brindle, T. Personal appearance in the countryside of Roman Britain. In The Rural Settlement of Roman Britain, New Visions of the Countryside of Roman Britain; Britannia Monograph 32; Smith, A., Allen, M., Brindle, T., Fulford, M., Lodwick, L., Rohnbogner, A., Eds.; Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: London, UK, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 30–65. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Brindle, T.; Fulford, M.; Lodwick, L. Lifestyle and the social environment. In The Rural Settlement of Roman Britain, New Visions of the Countryside of Roman Britain; Britannia Monograph 32; Smith, A., Allen, M., Brindle, T., Fulford, M., Lodwick, L., Rohnbogner, A., Eds.; Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies: London, UK, 2018; Volume 3, pp. 48–77. [Google Scholar]

- Prentiss, A.M.; Foor, T.A.; Hampton, A.; Ryan, E.; Walsh, M.J. The evolution of material wealth-based inequality: The record of Housepit 54, Bridge River, British Columbia. Am. Antiq. 2018, 83, 598–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallon, K. The meanings and value of Late Antiquity—J. STONER 2019. The Cultural Lives of Domestic Objects in Late Antiquity. Leiden: Brill. Pp. xii + 132. ISBN 978-9-00438-687-7. J. Rom. Archaeol. 2022, 35, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.; Roberts, D.; Roskams, S. A Roman Temple from Southern Britain: Religious Practices in the Landscape Context. Antiqu. J. 2021, 101, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Götz, M.; Cowley, D.; Hamilton, D.; Hardwick, I.J.; McDonald, S. Strategy and Structures along the Roman Frontier. In Proceedings of the 25th International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies 2, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2 September 2024; van Enckevort, H., Driessen, M., Graafstal, E., Hazenberg, T., Ivleva, T., van Driel-Murray, C., Eds.; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Buteux, S.; Gaffney, S.; White, R.; van Leusen, M. Wroxeter Hinterland Project and Geophysical Survey at Wroxeter. Archaeol. Prospect. 2000, 7, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, C.F.; Gater, J.A.; Linford, P.; Gaffney, V.L.; White, R. Large-scale Systematic Fluxgate Gradiometry at the Roman City of Wroxeter. Archaeol. Prospect. 2000, 7, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, V.L.; White, R.H.; Goodchild, H. Wroxeter, the Cornovii and the Urban Process. In Final Report on the Wroxeter Hinterland Project 1994–1997; Volume 1: Researching the Hinterland; Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series 68; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.H. Whitley Grange villa, Shropshire: A hunting lodge and its landscape. In Villas, Sanctuaries and Settlement in the Romano-British Countryside; Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 95; Henig, M., Soffe, G., Adcock, K., King, A., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.H.; Gaffney, C.; Gaffney, V.L. Wroxeter: The Cornovii, and the Urban Process. In Final Report on the Wroxeter Hinterland Project 1994–1997; Volume 2: Characterising the City; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.; Wigley, A. Shropshire in the Roman period. In Clash of Cultures? The Romano-British Period in the West Midlands; White, R., Hodder, M., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Ordnance Survey (OS). OS Terrain 5: User Guider and Technical Specification; Ordnance Survey: Southampton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.M.; Gittings, B.; Crow, J. Visibility analysis of the Roman communication network in southern Scotland. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2018, 17, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliou, E. Visual Perception in Past Built Environments: Theoretical and Procedural Issues in the Archaeological Application of Three-Dimensional Visibility Analysis. In Digital Geoarchaeology; Natural Science in Archaeology; Siart, C., Forbrigerm, M., Bubenzer, O., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, I. Discovering a Welsh Landscape: Archaeology in the Clwydian Range; Windgather Press: Macclesfield, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, D.; De Andrés-Herrero, M.; Willmes, C.; Weniger, G.-C.; Bareth, G. Investigating the Influence of Different DEMs on GIS-Based Cost Distance Modeling for Site Catchment Analysis of Prehistoric Sites in Andalusia. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G. Site catchment analysis. In Archaeology: The Key Concepts; Renfrew, C., Bahn, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Llobera, M. Understanding movement: A pilot model towards the sociology of movement. In Beyond the Map: Archaeology and Spatial Technologies; Lock, G., Ed.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- White, D.A.; Barber, S.B. Geospatial modeling of pedestrian transportation networks: A case study from precolumbian Oxaca, Mexico. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012, 39, 2684–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandolf, K.B.; Givoni, B.; Goldman, R.F. Predicting energy expenditure with loads while standing or walking very slowly. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 1977, 43, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, B.F.; Garrard, A.N.; Brandy, P. Modeling foraging ranges and spatial organization of Late Pleistocene hunter–gatherers in the southern Levant—A least-cost GIS approach. Quat. Int. 2016, 396, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, R.; Goldman, R. Terrain coefficients for energy cost prediction. J. Appl. Physiol. 1972, 32, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gruchy, M.; Caswell, E.; Edwards, J. Velocity-Based Terrain Coefficients for Time-Based Models of Human Movement. Internet Archaeol. 2017, 45, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surface-Evans, S.L.; White, D.A. An introduction to the least cost analysis of social landscapes. In Least Cost Analysis of Social Landscapes; White, D.A., Surface-Evans, S.L., Eds.; University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- De Montis, A.; Caschili, S. Nuraghes and landscape planning: Coupling viewshed with complex network analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés-Alba, A.; Calvo-Trias, M. Connecting Architectures across the Landscape: A Visibility and Network Analysis in the Island of Mallorca during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2022, 32, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, G.D.; Buckland, P.C. Sources of building materials in Roman York. In Aspects of Industry in Roman Yorkshire and the North; Wilson, P., Price, J., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Historic England. Strategic Stone Study: A Building Stone Atlas of Shropshire; Historic England: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, S.D.; Brown, T.J. Minerals Safeguarding Areas for Warwickshire. In British Geological Survey, Economic Minerals Programme, Open Report OR/08/065; British Geological Survey: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P.; Milward, D.; Young, B.; Merritt, J.W.; Clarke, S.M.; McCormac, M.; Lawrence, D.J.D. Northern England. In British Regional Geology; British Geological Survey: Nottingham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buffery, C.A. Changing Landscapes: A Legal Geography of the River Severn. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Vareilles, A.; Pelling, R.; Woodbridge, J.; Fyfe, R. Archaeology and agriculture: Plants, people, and past land-use. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2021, 36, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).