Abstract

This paper presents a rare example of the conservation of a piece of marine oval-shaped tableware, commonly known as a ‘cloche’, made of nickel silver with silver electroplating that was recovered in 2006 from the 19th-century Patris paddle-wheel shipwreck in Greece. Our study found that the cloche is made of two components of differing compositions of nickel-silver alloy, also known as German silver: a forged body and a cast handle, joined by lead soldering. The body also has an impressed decorative stamp bearing the ‘Greek Steamship’ signature in Greek. The condition assessment found the object was covered in thick concretion formations and suffered galvanic corrosion, along with dealloying, resulting in redeposition of copper. The conservation treatment carried out in 2007 is detailed along with diagnostic examination using microscopic analysis, radiographic imaging, and chemical analysis of the corrosion and metal, using scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) and portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF). The conservation of the object involved mechanical and chemical methods (formic acid 5–10% v/v, stabilisation treatment with sodium sesquicarbonate 1% w/v), including spot electrolysis, and the object was coated with 15% w/v Paraloid B72 in acetone. Since its conservation, the object has been on display in the Industrial Museum of Hermoupolis in Syros. In 2025, the object was inspected for its coated surface as well as to carry out pXRF again with a more advanced system to better understand the alloy composition of the object. These results are presented here for this unique object.

1. Introduction

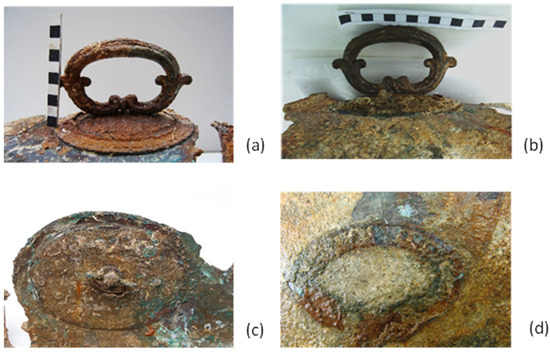

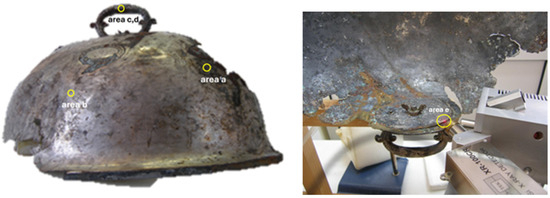

In 2006, several objects were recovered from a salvage operation of the 19th-century shipwreck Patris and were brought to the authors’ laboratory for conservation. One of those objects was a bell-shaped cover, or ‘cloche’, which is designed to fit over a serving dish (Figure 1). Measuring 44 × 22.5 cm, it is used to keep food warm and fresh. At the time, our macroscopic examination concluded that it was made of a copper alloy with a silver-plated finish consisting of two parts joined mechanically and with solder: the main body and the handle. There was also an unidentifiable oval stamp impression on the body. The cloche’s body was probably crafted by turning cold sheet metal on a lathe, while the handle was cast. The stamp was imprinted on the body using the impression technique.

Figure 1.

Different views of the serving tray cloche, © University of West Attica (K. Apostolopoulou).

A thick layer of marine concretions consisting of seabed sediments, salts, iron corrosion products, and marine organisms covered both the body and the handle (Figure 1). An initial examination also identified extensive black corrosion of the plating in areas where the concretion layer was absent, as well as reddish and green-blue corrosion products. These are indications of the presence of cuprite (copper oxide) and possibly basic copper chlorides (such as paratacamite) or oxychlorides (Cu2(OH)3Cl).

There are few published studies on the conservation of these types of nonferrous marine objects [1,2]. This study focuses on such a unique marine object and describes its condition assessment, the method of manufacture, the alloy compositions, the forms of corrosion, and the methods of conservation used to stabilize, clean, and protect the object in 2007. Since then, the object has been on display at the Industrial Museum of Hermoupolis (Syros) in a closed but not sealed showcase. In 2025, a follow-up inspection of the coated artefact was carried out to determine its current condition. It was deemed timely to reanalyse the object using a more advanced pXRF system that could provide a quantitative analysis in order to re-evaluate the original 2007 pXRF analysis of the object’s composition. While the 2007 pXRF analysis provided qualitative results indicating the composition to be nickel silver, there were still some open questions. The main questions were to determine the type of alloy used as the base metal for the silver-plated artefact and whether the silver plating was the result of electroplating or another plating method from the 18th or early 19th centuries. The condition assessment also provides valuable insights into the conservation of nonferrous composite artefacts from marine environments and serves as an example of a conservation plan involving stabilisation and cleaning.

2. Background Information

2.1. The Patris Shipwreck

The 217-foot-long steamer Patris was 27.5 feet wide and weighed 641 tonnes. It was propelled by two large iron paddle wheels, one on each side, in combination with sails. Built in 1859 at C. Lungley & Co.’s shipyards in Deptford, England, she was commissioned by King Otto of Greece and delivered in 1860. She was then registered with the Greek Steamship Company, the first steamship company founded in 1855 [3].

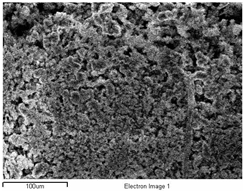

On 24 February 1868, the paddle steamer Patris collided with a reef southwest of Kea, breaking in two, with one part lying in shallower waters and the other in deeper waters ranging from 37 to 52 m, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Representation of the shipwreck from the documentary “Patris, Lost in 1868”, presented in 2008, http://www.ketepo.gr/el/2010/10/%CF%80%CE%B1%CF%84%CF%81%CE%AF%CF%82/ (accessed on 11 August 2025).

During the filming of the 2006 documentary, Patris, Lost in 1868, one of the two 8-tonne paddle wheels was lifted from a depth of 52 m, along with two royal cannons, an anchor, and a variety of smaller artefacts, including functional and decorative metal items, luxury porcelain tableware and glass cups and bottles. All of the artefacts, except the wheel, were stored wet in the Industrial Museum of Hermoupolis on the island of Syros. In 2007, many of the smaller metallic artefacts were brought to the authors’ lab for conservation [4], and the paddle wheel that was removed underwent in situ treatment using impressed current [5].

2.2. Nickel-Silver Alloys and Silver-Plating Techniques

Nickel-silver alloy, also known as German silver or nickel silver, is an alloy of copper, zinc, and nickel. It was invented through experimentation in an attempt to imitate Paktong, a Chinese white copper alloy that was imported from China in small quantities during the 18th and early 19th centuries [6]. European craftsmen used this alloy to make utilitarian and decorative domestic objects to imitate silverware.

As Pinn describes [6], by the 1830s, German silver production was established after initial experimentation to refine pure nickel. This new, more affordable and predictable alloy quickly became a popular alternative to Paktong in the British market, particularly for use in Sheffield and Birmingham’s silver trades. Consequently, after 1830, English nickel alloy objects were more likely to be made of German silver, with varying compositions but mainly an alloy containing 9–18 wt.% nickel. Furthermore, nickel-silver alloys are highly ductile and come in various forms like tubes, wires, and sheets [7]. Their properties vary with the nickel content: an alloy with around 18 wt.% nickel is corrosion-resistant, polishes to a white, silver-like finish, and is suitable for casting. In contrast, an alloy with 9–10 wt.% nickel is best for cold working.

Although silver as a plating material is less commonly preserved than gold, and corrosion at the interface between the silver and base metal can destroy evidence of how the plating was applied, there are sufficient examples to document technological developments in silver plating that achieve better results and make more economical use of the precious metal [8].

For similar luxury tableware from the time of the Patris shipwreck (pre-1868), the literature revealed different application techniques characterising the production of the 18th and 19th centuries, summarized in the following [6,8,9]:

- -

- In Sheffield plating, silver can be bonded to copper simply by heating the two metals in close contact with each other, without the need for an intermediate joining material or solder. Thomas Bolsover discovered this method in 1742, and most importantly, he found that the fused metals could be worked like solid silver [9]. German silver was used as a base metal for Sheffield process from the mid-1830s but only for articles that did not require complex shaping [6].

- -

- French plating was a method established in the 18th century, where the object is scored with fine grooves to provide keying and the silver foil is applied by rubbing and heating, until it is attached well into the grooves [9].

- -

- Close plating is an English process patented in 1779 by Richard Ellis, a London goldsmith, where a thin sheet of silver foil was manually fused onto a base metal object using a layer of molten tin as a solder. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this technique was used to plate silver onto a limited range of small iron or nickel-silver items [6,9].

- -

- Silvering pastes and solutions utilise the electro-differential between the plating paste or solution and the metal being plated to produce a very thin, pure, fine-grained deposit of silver with no distinguishable structure. This electrochemical process occurs when a metal from the negative end of the electromotive series is placed in an electrolyte containing ions of a more noble metal from the positive end of the series. This is a simple replacement reaction, so no external electric current is required. Silvering pastes and solutions, also known as cold silvering solutions, were undoubtedly discovered much earlier than electroplating [9].

- -

- Electroplating requires an external electric current, and difficulties were encountered in finding a suitable electrolyte during its early development. The development of electroplating as an industrial process is attributed to several English inventors, including John Wright and the Elkington cousins, George and Henry. In 1840, they patented the first commercially successful electroplating process for gold and silver [6,9]. Elkington silver plate was the thickest that could be bought at the time, around 35 μm, with most other suppliers happy to sell their EPNS (electroplated nickel silver) with coatings of 15–25 μm [1]. By the 1860s, electroplating had become standard practice in metal goods production [10].

More specifically, electroplating involves passing an electrical current through a bath containing a double cyanide of silver and potassium with a slight excess of free potassium cyanide. When used on a clean metal surface, it produces a thin, even deposit of pure silver. The most suitable metals for electroplating are brass, bronze, copper, and nickel silver (also known as German silver). This method superseded the others because it is relatively cheap and enables large numbers of complex-shaped items to be plated easily [9].

The use of German silver as a base for plated goods and ‘British plate’ (unplated burnished wares) became so widespread that, by the time electroplating was introduced, a few years later, plating onto copper was largely superseded. Complex construction methods that had evolved and been refined over the previous eighty years, such as Sheffield and French plating, were rendered redundant by electroplating. This technique was so revolutionary that, within ten years, the traditional plating methods had almost completely died out [6].

The electroplating process has the great advantage that a silver can be deposited on a piece after its production, thereby concealing seams, joints, and minor flaws. More importantly, cast component parts, such as handles, could now be used, offering much greater design flexibility and increasing sturdiness and durability. Fragility was always an issue due to the relatively thin layer of deposited silver compared with more elegant Sheffield wares [6].

2.3. Marine Environment and Its Effect

The corrosivity of seawater is determined by a combination of factors. The salinity, i.e., the amount of salt, and the concentration of dissolved oxygen in the water significantly impact its corrosivity. Temperature and the presence of various biological factors, such as bacteria, fungi, and algae, also play a crucial role. Corrosivity is also influenced by the displacement or movement of the corrosive medium relative to the metal exposed to the water and by the metal’s specific type [11].

The ‘Patris’ shipwreck is lying in the Aegean Sea, a saltwater body with an average depth of about 350 m. Monitoring stations set up by the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR) obtain data on temperature, pH, oxygen content, and salinity at various depths (surface, 10 m, 20 m, 50 m, 75 m, and deeper) all year round [12]. As Argyropoulos et al. documents (2025), the amount of dissolved oxygen (DO) in the sea varies from 5.1 to 5.65 mg/L during the yearly season and at various depths; the oxygen level does not vary in this area for up to a 30 m depth; the temperature of the Aegean Sea is 12–28 °C depending on season and depth, and is stable during the seasons, although subject to variations due to thermoclines; salinity increases from the surface to deeper levels, e.g., from 35 to 39 psu depending on the season; and the pH ranges from 7.5 to 8.2, and from 6.5 to 9.5 in marine sediments [13].

Under these conditions, rapid corrosion of metals is expected, influenced by parameters such as oxygen, temperature, salinity, pH, light penetration, sedimentation, and organic activity [14].

2.4. Corrosion of Nickel-Silver Alloys in Marine Environment

Nickel-silver alloys, as mentioned above, have a white tint and are tough, malleable, ductile, and corrosion resistant. Their high electrical resistance significantly affects corrosion performance [15]. Few publications describe the corrosion mechanism of nickel-silver alloys, with or without silver plating, for marine cultural heritage objects [1,2].

There are corrosion studies related to the marine industry on cupronickel, copper-nickel alloys (particularly 90/10), and brass alloys [13,16,17,18,19]. Copper-nickel alloys are renowned for their corrosion resistance, excellent machinability, and exceptional thermal and electrical conductivity in marine environments. As Jin et al. (2019) [16] describe, the oxide film on cupronickel alloys in seawater undergoes a substitution of Ni2+ into vacant Cu+ positions in the Cu2O lattice, thereby increasing the electrical resistance of the oxide film. The film changes from pure Cu2O to a mixture of CuxO and a copper hydroxide/oxide layer, which protects the underlying alloy [16].

The marine industry describes how the dealloying process, whereby one or more elemental constituents dissociate preferentially, is one process that appears to control corrosion performance in a marine environment. The most common forms are dezincification and denickelification [13,20,21,22].

Liu et al. (2015), examining the case study of failed copper-nickel tube section from a heat exchanger, define that dealloying is consistent with the mechanism of the simultaneous dissolution of Zn or Ni and Cu, followed by the redeposition of brown/purple Cu [21], and can be presented as follows:

Ni (or Zn) → Ni2+ (or Zn2+) + 2e− (Ni or Zn oxidation)

Cu → Cu2+ + 2e− (Cu oxidation)

Later Cu2+ ions reduce to metallic Cu due to a higher tendency of Cu2+ than Ni2+ or Zn2+ ions to plate out of solution.

Cu2+ + 2e− → Cu (Cu reduction)

Jin et al. (2019) [16] investigated corrosion behaviour and surface characterisation of 90/10 copper-nickel alloy sheet in natural sea water (NSW) describing that the Cu2O film formed initially is divided into an inner layer and outer layer, in which the outer layer is produced by the deposition of dissolved Cu2+, while the inner layer is produced by the more compact and protective Cu2O film. This makes the oxidation products of the outer layer porous and prone to falling off, because the strength of the corrosion product film is lower than its internal stress, leading to cracks in the film [16].

Research has shown that the presence of iron in burial environments near copper objects, due to the presence of iron objects or iron construction elements of a shipwreck (e.g., a ship’s paddle wheels), helps to form a protective layer, typically a layer of cuprite [23,24]. Copper and its alloys act as the cathode, reducing oxygen levels and increasing the pH of the water. This subsequently leads to the precipitation of calcium carbonate and the formation of concretions, which can be categorised into three types [24]. These concretions can form only in aerobic conditions.

MacLeod’s (2004) study of marine objects made of nickel-silver alloys from historic shipwrecks in both shallow and deep seawater, emphasises the impact of concretions on corrosion mechanisms, which provide an oxygen diffusion barrier to corroding surfaces [1]. Large amounts of iron are present in the concretions due to the incorporation of iron corrosion products, when the shipwreck vessel is made of steel alloys (as is the case with modern ships). In such cases, the properties of nickel-silver alloys are sensitive to the relative proportions of zinc and nickel. Also, extensive mineralisation is identified on non-concreted surfaces, which are characterised by little mobilisation of nickel but significant loss of zinc from the parent metal [2]. Other corrosion products detected on nickel-silver alloys in shallow waters were cuprite (Cu2O), along with significant amounts of zincian paratacamite (previously called anarakite, (Cu,Zn)2(OH)3Cl), as well as nickel(II) hydroxide (Ni(OH)2) [2].

The condition assessment of silver-plated nickel-silver cutlery from a deep-water environment of the Titanic revealed extensive pinhole corrosion caused by microscopic defects in the silver plating [1]. The plating had deformed due to pressure in hollowed-out pits beneath it, allowing chloride ions to penetrate and accelerate pitting corrosion in the underlying nickel-silver alloy. The corrosion products from a set of concreted silver-nickel spurs from a shallow and well-oxygenated wreck were identified by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and revealed significant dezincification and mobilisation of nickel [2]. For the artefacts from the Titanic shipwreck, stabilisation treatment was performed with immersion in a 50% volume aqueous solution of acetonitrile and water for 48 h in the LP3 laboratories at Semur-en-Auxois [1], whereas stabilisation for the artefacts from a shallow wreck included three months of washing in 2 w/v% sodium sesquicarbonate in deionized water [2].

2.5. Silver Corrosion in Marine Environments

Studies on marine silver objects determine that their corrosion products primarily consist of insoluble silver chlorides, sulphides, and bromides, which form when these anions are present in the surrounding environment [19,25]. A short-term electrochemical study on the corrosion mechanism found that silver chlorides usually form on the surface of silver oxide in a physiological sodium chloride (NaCl) solution [26]. Initially, they form within surface irregularities, such as scratches. Eventually, a uniform layer of silver chloride forms, dissolving the oxide layer [26].

Long-term exposure to chloride-rich environments, such as seawater, can lead to mineralisation. This is a continuous process due to the high ionic mobility of silver, whereby silver ions can quickly migrate to the surface [27]. The presence of bromide ions (Br−) also favours the formation of mixed silver chloride/bromide (embolite) [25].

In the absence of oxygen, the most common mineral alteration compound of silver is silver sulphide (acanthite, Ag2S), which is produced by high concentrations of hydrogen sulphide generated by sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB) [28,29]. As the silver sulphide film thickens, the colour and reflection of the surface changes from light interference tones to brown and finally black [30]. Studies on silver alloy coins showed that they are most often covered with concretions of varying composition, consisting of calcium carbonate, magnesium hydroxide, magnesian calcite (Ca1−xMgxCO3), and occasionally magnesian aragonite [31,32].

3. Methods and Materials

The methodological approach to the conservation project in 2007 included the following:

- A thorough visual inspection of surface technological features and corrosion stratigraphy.

- A stereomicroscope was used to perform a microscopic examination of the surface, technological features, and corrosion stratigraphy. This was initially carried out after the concretion layers had been removed and again after the object had been treated. A stereomicroscope with ×64 magnification was used for the microscopic examination.

- Sampling from areas of interest for further diagnostic analysis. Sampling was performed with a scalpel under a stereomicroscope at two selected points: one from a black area on the inside of the cloche, and a second from a whitish-grey area on the handle where the plating had worn off.

- Multi-analytical assessment:

X-ray radiography to determine technological features (e.g., construction, decoration, and forming techniques) and condition (e.g., amount of residual metal, thickness of concretions, and presence of cracks). X-ray radiography was performed before the removal of concretions using a digital CR X-ray machine (model CPI CMP200, series 50 kW, manufacturer Communication & Power Industries, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with a Fujifilm FCR Capsula-X detector (manufacturer Fujifilm Holdings Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The energy ranged between 100 and 120 keV, with the vertical position ranging from the object towards the source.

Portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) for qualitative and quantitative analysis of plating layer and metal substrate composition, as well as corrosion product characterisation.

A portable Amptek EDXRF setup (manufacturer Amptek Inc., Bedford, MA, USA) was used after the removal of concretions where the X-ray beam was generated by a mini mobile X-ray source with an Ag anode (Amptek Laser-X), providing a low current of 10 μA and a maximum energy of 35 keV. Fluorescence radiation was measured using an Amptek XR-100CR Si-PIN detector covering the energy range from 1 to 30 keV, coupled with an Amptek 8000A multi-channel analyser (MCA). The calibrated spectra can be used to qualitatively examine a location on the object.

Scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) was conducted to characterise the metal substrate and corrosion products. Elemental analysis was carried out on two samples without further preparation using a JEOL JSM 5310 SEM with a Pentafet 6587 detector (manufacturer JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with INCA analysis system software and hardware for EDX (manufacturer Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, UK). EDX was performed at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV.

The locations of the pXRF measurements in 2007 were chosen to determine the manufacturing process and condition of the object so as to come up with a treatment strategy for the object. These areas were the plating layer in the body; the metal substrate in the body (an area with plating loss); the plating layer in the handle; the whitish-grey area in the handle (an area with plating loss); the metal substrate in the handle (an area with plating loss); and the welding or soldering layer (where the handle is attached).

With regard to sampling of the metal, it should be noted that, according to Greek Law 3028/2002 on the protection of antiquities and cultural heritage, any invasive sampling of archaeological material requires official written permission from the Greek Ministry of Culture. During the conservation in 2007, such permission was not requested since it was deemed unnecessary for the conservation strategy. Our lab had to carry out and return the Patris’ objects to the Industrial Museum in Syros as soon as possible and their treatment was more important than further technological studies.

In 2025, pXRF analysis was performed with a more advanced pXRF system than the one used in 2007 in the museum where the object is on display. The system was a Bruker, Tracer 5, with a 50 kV–4 W Rh target X-ray source and measurement spot size of 3 mm (Artax version 8.0.0.476). The measurements were performed with the preset application mode Alloys 2–3 mm and time analysis of 60 s. The aim was to evaluate the performance of the coating system through the identification of possible corrosion products due to the impact of the indoor museum environment and to better understand the manufacturing technology of the object. When interpreting the results, it was considered that the fluorescence signal originates from a depth of around 0.1 mm within a copper alloy [33].

The selected measurement points were representative of the following:

- -

- Clean plating areas versus tarnished plating areas on both the inside and outside of the body and the handle;

- -

- Areas with plating loss and dark brown/black corrosion of the metal substrate, characterised by a layer of cupric/cuprous oxides;

- -

- Areas where redeposited copper was identified with microscopic examination.

4. Analytical Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of Examination and Spectroscopic Techniques

- Visual observation

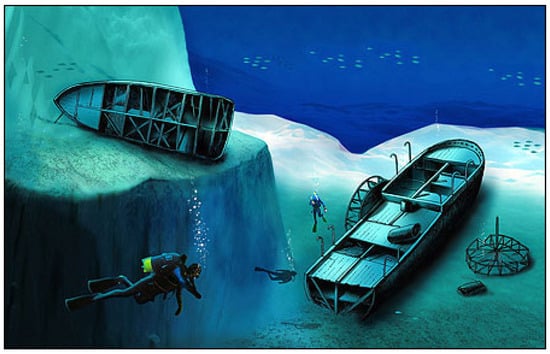

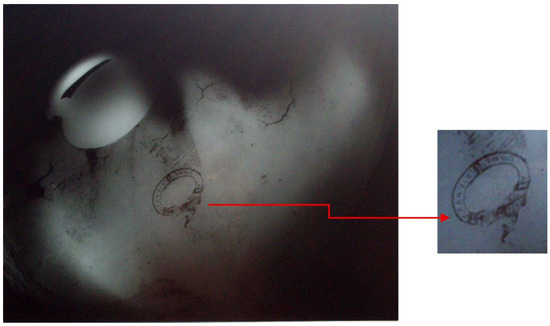

Examination of surface characteristics identified areas of interest as the area of the handle and the stamped signature (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a,b) Views of the handle and the body covered with a thin layer of concretion, containing iron corrosion products and remnants of marine organisms (annelida) in 2007. Black corrosion is documented in non-concreted areas. (c) View of the base of the handle, showing the presence of a mechanical joint for attaching the handle to the body in 2007. This area is covered with a thin layer of concretion and copper corrosion products on the right, as well as copper oxides and green corrosion products, which were probably cuprite and copper chlorides/oxychlorides. (d) View of the stamped area, where the shape can be seen, but the concretion layer makes it impossible to identify the signature in 2007, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

- X-ray radiography

Radiographs of the cloche in 2007 revealed a stamp bearing the owner’s name in Greek, ΕΛΛHΝΙΚH AΤΜOΠΛOΪA (Greek Steamship Company, Athens, Greece) which was concealed beneath a thick layer of marine deposits, seabed sediment and corrosion products from metal. Extensive ‘invisible’ embrittlement due to concretions has formed around the handle area, particularly in areas where material has been lost (Figure 4), highlighting its poor condition and the need for careful handling during the conservation process. The X-ray image did not reveal any other stamps or producer marks under the concretions that could help to identify the manufacturer or the plating method used.

Figure 4.

X-ray of plated lid in 2007. The stamp ‘ΕΛΛHΝΙΚH AΤΜOΠΛOΪA’ (Greek Steamship Company) can be seen clearly in the middle of the object, as can signs of embrittlement of the metal around its edge, © University of West Attica (Karamanou A. & Loizou Tz.).

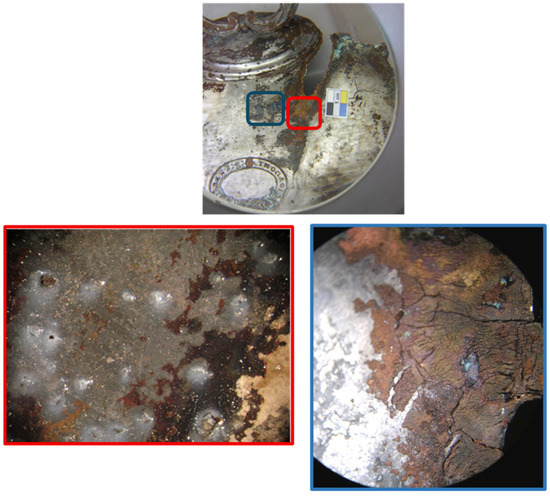

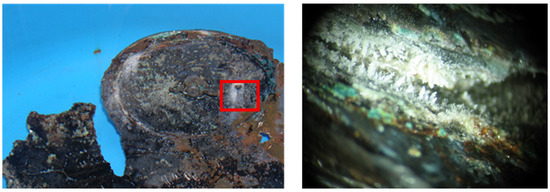

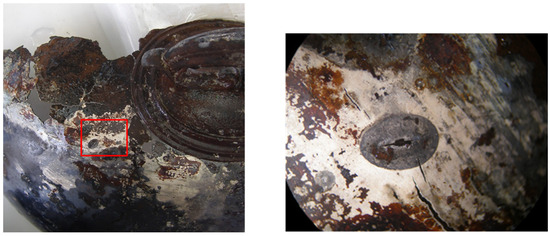

- Microscopic examination

Observation of the cloche under a stereomicroscope after the removal of the concretion and cleaning surface treatments in 2007 revealed the condition of the plating layer and the metal substrate:

- -

- Extensive black corrosion on the surface of the plating.

- -

- -

- Selective corrosion of the soldering lead alloy in the joint between the lid and handle due to object being stored in deionized water in the conservation lab (Figure 7).

- -

- Localised pitting of the silver plating and the copper alloy (Figure 8).

- -

- Blue-coloured corrosion of copper on the handle (Figure 9).

Figure 5.

After concretion removal, a layer of redeposited copper underneath the plating layer (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square is documented, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 5.

After concretion removal, a layer of redeposited copper underneath the plating layer (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square is documented, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 6.

After concretion removal: Localized pitting corrosion (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, where pitting is recognized in small white pin holes; iron corrosion products are observed on the left corner and the right side area (left). Corrosion of redeposited (secondary) copper underneath the plating layer (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the blue square (right), © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 6.

After concretion removal: Localized pitting corrosion (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, where pitting is recognized in small white pin holes; iron corrosion products are observed on the left corner and the right side area (left). Corrosion of redeposited (secondary) copper underneath the plating layer (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the blue square (right), © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 7.

After concretion removal: Selective corrosion of the lead soldering alloy (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 7.

After concretion removal: Selective corrosion of the lead soldering alloy (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 8.

After concretion removal: Pitting corrosion on the plating layer and iron corrosion products (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 8.

After concretion removal: Pitting corrosion on the plating layer and iron corrosion products (×64), and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 9.

After concretion removal: Blue-coloured corrosion of copper (×64) and underlying iron corrosion product, and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

Figure 9.

After concretion removal: Blue-coloured corrosion of copper (×64) and underlying iron corrosion product, and microscopic imaging of the area inside the red square, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

- XRF results in 2007

Portable EDXRF analysis of selected areas of the cloche revealed qualitative information about the alloy composition and the plating material, as well the presence of corrosion products (Table 1, Figure 10).

Table 1.

XRF qualitative results of selected areas in 2007.

Figure 10.

EDXRF analysis areas in 2007: (left) areas a–d and (right) area e.

Analysis of areas of the body and handle (areas a and c) where the plating was not preserved revealed the presence of copper, zinc, and nickel. Analysis of the plating area on the body (area b) identified the presence of silver, copper, zinc, and nickel, with nickel present as a trace element. Also, Cl was determined in area b, indicating the formation of chloride corrosion products due to the abundance of such anions in the marine environment. In a brown area (area d), the analysis identified copper, zinc, and iron, with nickel also present as a trace element. Analysis of the joint between the body and the handle (area e) revealed the presence of lead.

These results in 2007 supported our conclusion that a nickel-silver alloy was used for the manufacture of the cloche and silver for the plating. A lead metallurgical joint was used for the attachment of the handle to the body.

Regarding corrosion products, the analysis of a brown area suggested iron corrosion resulting from the surrounding burial environment, and confirmed the dealloying process of denickelification, since nickel was identified as a trace element. Also, Cl was detected in areas of the plating on the body of the object.

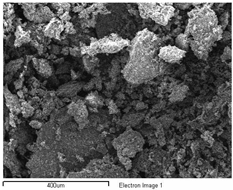

- SEM-EDX results in 2007

SEM-EDX analysis (Table 2) was performed on two samples: one from a black corrosion layer on the surface of the body and the other from a whitish layer that was found on an area of the cast handle where the plating had worn off.

Table 2.

SEM-EDX results on two samples from the body and the handle of the cloche before treatment in 2007.

Analysis of the sample taken from the black corrosion layer on the inner surface of the body revealed the presence of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn) as well as silver (Ag) in major and minor elements, but nickel (Ni) was not detected. Also, Ca, S, Si, and Al were identified in minor and trace concentrations. The presence of S indicates silver corrosion and the formation of silver sulphide (most likely acanthite), as well as the presence of Ca, Si, and Al from the concretion layer. This suggests that the bottom part of the object was most likely buried in the sediment and underwent corrosion due to sulphur-reducing bacteria (SRB), and then was re-exposed to the open water and concretions were then formed. Analysis of the sample from the white corrosion layer in an area of plating loss on the handle revealed major concentrations of Zn, Ni and O, and Ca as a trace element, and Cu was not detected; these are most likely oxides/hydroxides of the secondary alloying elements [1,2]. Evaluation of the results correlates them with the dealloying mechanism involving denickelification in the internal surface of the body of the object as opposed to decuprification on the handle of the object [12,13,14,15].

- XRF results in 2025

Portable XRF analysis was conducted in 2025, with the results presented in Table 3 and Table 4, Figure 11 and Figure 12. Table 3 shows the results of examining the plating layer on the body and handle, while Table 4 shows the results of examining the metal substrate on the body and handle in the brown-black areas where the plating has not preserved.

Table 3.

pXRF analysis from selected spots on the plating of the body and the handle of the cloche in 2025. Areas of analysis shown in Figure 11.

Table 4.

XRF analysis in 2025 from selected spots on the metal substrate of the body and the handle of the cloche, where a black/brown layer was observed where the silver plating was not preserved. Areas of analysis shown in Figure 12.

Figure 11.

pXRF analysis areas in 2025: (left) areas a and c–f, and (right) area b.

Figure 12.

pXRF analysis areas in 2025: (left) areas a and b, and (right) area c.

The pXRF analysis in 2025 of clean plating spots revealed a variation in Ag wt.% between 87.25 and 93.96. Copper, zinc, and nickel are detected, representing the base metal substrate, a nickel-silver alloy. Iron is detected as a major element in spots d, e, and f, indicating the presence of iron corrosion products due to the concretion layer and the contamination from the surrounding environment. The presence of iron corrosion products can also be identified in Figure 6, Figure 8 and Figure 9, indicating the presence of iron objects or iron-made ship components around the cloche. Finally, S is detected in spots e,f, but it is unclear if it is evidence of a silver, iron, or copper sulphide formed under anaerobic conditions during marine burial. There may be further evidence of SRB corrosion, due to the dark blue/black corrosion product that was observed under the microscope (see Figure 9), which is most probably an indication of covellite formation.

Analysis of the black/brown areas of the plating layer as shown in Table 3 revealed a variation in Ag wt.% ranging from 61.07 to 48.08, as well as the presence of S (2.83–1.51 wt.%) and a significant Fe concentration (24.89–14.17%). The presence of copper, zinc, and nickel was also detected due to the nickel-silver substrate alloy. It is unknown if the sulphur content corresponds to the presence of sulphides of either silver or possibly iron.

The pXRF analysis in 2025 for selected areas with plating loss as shown in Table 4 documented the presence of copper, zinc, and nickel, with different Ni percentages between the body and the cast handle, corresponding to the use of a nickel silver as the manufacture alloy and indicating the use of two different compositions, one for the body containing ~8% nickel and one for the handle containing ~18% nickel. Other elements were identified in minor and trace concentrations, such as Ag, Fe, Si, Al, and Pb. The presence of Pb is probably due to surface leaching of the lead solder that connected the handle to the body. Elements such as silicon and aluminium originate from the seabed and were incorporated into the concretions covering the cloche.

4.2. The Conservation Treatment

Following a detailed examination of the cloche in 2007, it was decided that an effective conservation methodology should be designed and applied to protect and stabilise the cloche, highlight its technological features, and reveal its original surface.

Many studies have evaluated the different types of conservation treatments for cleaning silver (mechanical, chemical, and electrochemical) and stabilising copper alloys in a marine environment, evaluating the different methods and materials used [28,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. A conservation plan was conceived by reviewing some of these studies, considering the preservation state of the cloche and the need to highlight its museological value. This plan involved removing concretions and chlorides to expose the original surface, as well as cleaning the silver-plated surface using spot electrolysis, since the plating was not preserved intact and the cloche could not be immersed in an electrolytic bath.

In October 2007, the cloche was transported to the authors’ lab wet in plastic container filled with tap water. Once the Patris’ metals collection arrived at the laboratory, the artefacts were documented using a digital camera and a registration form was completed and then they were placed in containers filled with deionised water.

The conservation strategy implemented focused on removing concretions using a combination of chemical solutions and mechanical cleaning methods involving hand and power tools. This revealed the objects’ authentic surfaces and the condition assessment discussed above required the object’s stabilisation treatment by immersion in dechlorination solution of 1% w/v sesqui-carbonate solutions in deionized water for seven weeks.

- Concretion removal

A combination of chemical and mechanical cleaning was deemed the most effective method for removing concretions. Two methods were employed:

- (a)

- Application of cotton compresses containing a 10% w/w aqueous formic acid solution in deionized wather for 30 min, followed by mechanical cleaning with a scalpel;

- (b)

- Immersion of the cloche in a 5% w/w aqueous formic acid solution in deionized water for 5 min, followed by mechanical cleaning with a scalpel and a thorough rinsing with deionised water after each application.

Concretions are usually made up of calcite and/or aragonite, both are calcium carbonate but with different crystalline structures: the former can be easily dissolved by acids compared to the latter; given its needle-like structure, only a pneumatic air-scribe can be used to break and remove the concretions without harming the metal underneath. Formic acid is commonly used to clean surfaces of pure silver without harm and can easily dissolve calcite. When the metal alloy is not silver, care is needed to ensure that the formic acid will not harm the alloy, so the procedure must be controlled and thorough rinsing with water is needed after the procedure. It is interesting to note that all of the concretions for all of the Patris nonferrous objects were easily dissolved with formic acid, as opposed to the authors’ experience with other marine metal finds from the Aegean Sea [13], for which the concretions were predominately made up of aragonite and could not be dissolved at all. The authors believe that this could be due to the age of the shipwreck and/or the surrounding burial environment. Finally, when mechanical cleaning was tested to remove the concretions of the plated object, the silver plating would come off like a foil, and the procedure was abandoned.

Concretion removal revealed silver plating and copper oxide layers in areas where the plating had been destroyed (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The exposure of the plating after the removal of concretions in 2007, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

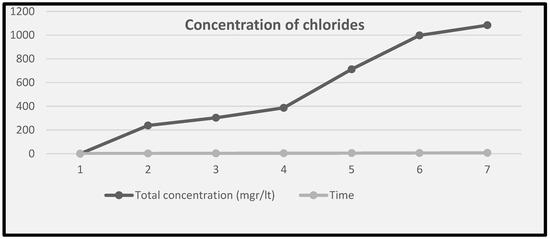

- Stabilisation process

The stabilisation treatment of the object to remove the chlorides required that the lid was completely immersed in an aqueous solution of 1% w/v sesquicarbonate in deionized water (approximately 26 L) for approximately 7 weeks; the solution was changed weekly and was analysed each time for amount of chlorides using potentiometric titration with silver nitrate. Figure 14 shows the results of Cl removal, with approximately 1100 mg/L of chlorides in total measured in the sesquicarbonate stabilisation solutions. The solution was changed after each measurement and the data in Figure 14 add together the weekly measurements to show the total amount.

Figure 14.

Total additive concentration of chloride anions (mg/L) over time in weeks.

- Cleaning of tarnished plating

After the stabilisation process, it was decided that the thin black corrosion layer on the silver-plating layer should be reduced electrolytically to expose the silverish plating surface, since mechanical cleaning may damage this plated surface. Spot electrolysis was chosen as the method to selectively treat the silver plating, and to protect the base nickel-silver alloy.

For Ag 999, silver ions (Ag+) are reduced to metallic silver (Ag0) at a potential of −0.85 volts versus the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) and the current intensity which corresponds to around 3.5 mA [39]. Low current amperemeters were designed for the authors’ lab not to surpass a 3.5 mA setting to be used for the cleaning of tarnished silver objects. These settings were established in the authors’ lab in 2007 under the direction of Dr. C. Degrigny, who has since designed the electrolytic pen for the removal of AgCl and/or AgS for both 925 and 999 Ag.

The negative pole (cathode) of the power generator was connected to the object, and the positive pole (anode) was connected to a thin stainless-steel rod. The current intensity was set to 3.5 mA. A small piece of cotton soaked in 1 w/v% sodium sesquicarbonate solution in deionized water covered the tip of the rod. Care was taken to ensure that the wet cotton swab only came in contact with the black corrosion layer of silver layer. A few seconds were needed to reduce the black layer to silver. The cleaned areas were rinsed with deionised water to remove remnants of the solution used. The procedure of spot electrolysis is now commonly used for reduction of silver sulphide from silver and Degrigny et al. provide more information on the evolution of this technique [39].

This process transforms the silver corrosion products into metallic silver. This new layer occupies a smaller volume because metallic silver is denser than the silver corrosion products. The redeposited silver surface layer is either granular with poor adhesion to the metal substrate, or hard, tough, and dull due to voids (Figure 15). To best highlight the redeposited silver layer after electrolysis, the granular silver surface should be rinsed with deionised water and lightly burnished with precipitated chalk (Mohs hardness 3), in order to make the surface of the silver more homogeneous (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Top (left), spot electrolysis process tested on black areas prior to concretion removal. Top (right), dull appearance of silver plating after spot electrolysis. (Bottom), silver-plated cloche after polishing and coating with Paraloid B72 in 2007, © University of West Attica (K. Kamani).

- Coating process

As surfaces of silver cleaned by electrochemical methods are more susceptible to tarnishing, the decision was made to coat the cloche in a 15% w/v Paraloid B72 solution in acetone with a fine brush to prevent tarnishing caused by sulphur compounds when the cover is exposed to uncontrolled environmental conditions at the Industrial Museum of Hermoupolis.

- Monitoring of treatments

During a visit in 2025, the condition was assessed with visual inspection, and it was documented that the object was stable, but appeared more tarnished than shown in Figure 15. Areas where the plating was lost and oxides were present appeared darker and areas of the silver plating next to them appeared more tarnished than our photographic documentation in 2007 (comparing Figure 15 with Figure 16). Also, isolated black spots were observed on the body and the base of the handle. Analysis with pXRF on the dark areas of the silver plating identified the presence of sulphur (Figure 16).

Figure 16.

General view of the cloche in 2025, © University of West Attica.

5. Conclusions

Thorough macroscopic and microscopic inspection, as well as diagnostic examination involving radiography, XRF, and SEM/EDX techniques, provided significant information regarding the artefact’s manufacturing technology and condition (i.e., corrosion stratigraphy and products).

The body was made of a nickel-silver alloy (German silver) containing ~8% nickel, and the handle was made of a nickel-silver alloy containing ~18% nickel. Nickel silvers do not contain silver but are essentially copper–zinc brasses containing 9–18% nickel. An 18% nickel alloy polishes to a colour similar to silver and has good corrosion resistance. The body was forged from a nickel-silver sheet, while the handle was cast in a mould. The two parts were joined together mechanically using a nut and bolt placed under the handle, as well as a lead welding alloy. The relative dating of the cloche indicates that such an alloy was used, as English nickel alloy objects were more likely to be made of German silver from around 1830 onwards, with varying compositions but mainly containing 9–18% nickel.

The cloche was most probably silver-plated using the electroplating technique, which has been in use since 1840. Despite its earlier discovery, electroplating, the process of applying a thin, durable layer of silver to another metal, only became commercially viable in the mid-19th century, as La Niece and others describe [8,9,10].

Given that ‘Patris’ was built in England in 1859, and that all of the luxury tableware was likely ordered around this time, it is reasonable to assume that the metal plating was carried out using the electroplating technique given its complex and large size and was more likely produced with this method than Sheffield plating. The fragility of the silvering layer, which was documented during conservation treatments, is also a characteristic of the electroplating technique, which produces a layer between 15 and 25 μm thick [1], compared to the Sheffield technique (~0.25 mm) [8]. Furthermore, the results of the XRF analysis in 2025 support this scenario, as the alloying elements of the nickel-silver substrate were present in all of the spot measurements of the plating layer, indicating the presence of a thin layer of electrodeposited silver that was permeable to X-rays.

The cloche has suffered considerable deformation and loss of material due to corrosion and mechanical stress. There is severe embrittlement around the area where the handle joins the body, as well as along the body’s periphery. X-ray radiography revealed the extent and dimensions of the cracks beneath the marine concretions, as well as the weak areas of the metal core.

A layer of concretions of varying thicknesses, marine organisms, and iron and greenish copper corrosion products covered the surface of the cloche. This was due to the effect of the marine environment and the proximity of iron objects or the metal construction of Patris vessel. Microscopic examination of the concretion layer classifies it as aerobically formed, dense, with low porosity, and with uniform coverage of the entire object, alongside secondary colonisation by annelid species [24].

Following the removal of concretions, the silver-plated surface exhibited a uniform black colour consisting of silver and iron corrosion products. EDXRF and pXRF qualitative and quantitative results, respectively, demonstrated this observation. Unfortunately, the Department of Conservation of Antiquities was not equipped with an XRD system to identify the mineralogical composition of corrosion products during the initial condition assessment in 2007. Despite this, EDXRF analysis identified the presence of Cl, indicating the formation either silver chloride and/or copper chlorides, while SEM-EDX analysis of the black layer identified the presence of S, indicating the formation of silver sulphide and/or copper sulphides. The pXRF analysis in 2025 highlighted the presence of iron corrosion products in high concentrations and the formation of metal sulphides. Thus, the object underwent aerobic and anaerobic corrosion during burial in the sea as is common for objects where the covering and uncovering of sea sediment often occurs over time.

Microscopic examination revealed that, in areas where the silver plating had not been preserved, a thick secondary layer of redeposited copper had formed due to selective corrosion resulting from the dealloying of copper, zinc, and/or nickel. This redeposited copper layer was porous and exhibited cracking [16]. XRF and SEM-EDX analyses of the metal substrate supported the presence of dealloying in the form of denickelification and/or copper depletion. Zinc and nickel corrosion products, probably oxides/hydroxides, were also observed using SEM-EDX; however, they could not be identified with certainty due to the absence of an XRD system at that time.

Other elements, like Si, Al, and Ca identified in minor and trace concentrations can be explained as depositions from the concretions and the sea sediment.

In the case of the silver-plated cloche, the nickel-silver alloy underlying the silver plating is the most active metal, while the silver plating is the noblest. Therefore, accelerated corrosion of the alloy is expected to occur alongside cathodic protection of the silver. This could explain why the silver plating is well preserved under the concretion layer and why selective corrosion has occurred in the metal substrate. The different preservation state of the body and the handle is correlated with the manufacturing technique, since worked metal corrodes faster than cast metal.

Finally, evaluation of the selected conservation methodology confirms that a combination of traditional chemical and mechanical methods, alongside electrochemical cleaning via spot electrolysis, was necessary to reveal the silver layer and eliminate black corrosion without impacting the secondary copper areas formed through selective corrosion.

Visual inspection and pXRF analysis in 2025 reveal that the object is stable and in good condition. However, the coating needs to be replaced after over 15 years in the display case of the museum in an uncontrolled environment as sulphur has been detected, probably due to pollutants in the museum environment. The authors plan to carry out further analyses in the future on the condition of the coating using FTIR analysis and to ask for permission to study more closely the microstructure and plating of this interesting object. Eventually, all of the Patris objects treated and on display will have to undergo coating removal and recoating. The authors are currently carrying out research to determine the best procedure and coatings to use for these objects, considering the exhibition environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.; methodology, M.G. and V.A.; software, M.G. and V.A.; validation, M.G. and V.A.; formal analysis, M.G. and V.A.; investigation, M.G. and V.A.; resources, V.A.; data curation, M.G. and V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G. and V.A.; visualization, M.G.; supervision, V.A.; project administration, V.A.; funding acquisition, V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Special Account for Research Funds of the University of West Attica, Greece.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following people for their contributions to this project: Anno Hein, Researcher at the National Centre of Scientific Research “Demokritos” and Ioannis Sianoudis, at the University of West Attica, for performing the XRF analysis in 2007; Athanasios Karabotsos, Technical Laboratory Staff at the University of West Attica, for performing the SEM-EDS analysis in 2007; Theodoros Panou, Technical Laboratory Staff at the University of West Attica, for performing the X-ray radiography in 2007; Stavroula Golfomitsou, laboratory teaching personnel at the University of West Attica in 2007–2008; and K. Apostolopoulou, K. Kamani, A. Karamanou, and Tz. Loizou, conservation students, for their support during the documentation and conservation stages.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- MacLeod, I.D.; Pennec, S. Characterisation of corrosion products on artefacts recovered from the RMS Titanic (1912). In METAL 2001, Proceedings of the ICOM Committee for Conservation Metals Working Group, Santiago, Chile, 16–20 April 2001; Western Australian Museum: Perth, Australia, 2004; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, I.D. Corrosion and Conservation of Nickel Silver Alloys Recovered from Historic Shipwrecks. In METAL 2022, Proceedings of the Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, Helsinki, Finland, 5–9 September 2022; Mardikian, P., Nasanen, L., Arponen, A., Eds.; International Council of Museums—Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) and The National Museums of Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 2022; pp. 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: http://www.ketepo.gr/el/2010/10/%CF%80%CE%B1%CF%84%CF%81%CE%AF%CF%82/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Argyropoulos, V.; Giannoulaki, M.; Malea, E.; Pournou, A.; Rapti, S. Corrosion theory for metallic and composite artefacts in the Aegean marine environment (Chapter 4). In The Conservation of Marine Metal Shipwrecks and Artefacts from the Aegean Sea. Good Practice Guide; Argyropoulos, V., Giannoulaki, M., Charalambous, D., Eds.; Dionikos Publications: Athens, Greece, 2015; ISBN 978-618-5208-06-6. [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Batis, G. Saving a marine iron paddle wheel removed from the 1868 steam engine shipwreck “Patris” during an economic crisis in Greece. In Big Stuff 2013; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinn, K. Paktong: The Chinese Alloy in Europe 1680–1820; Antique Collectors’ Club Ltd.: Suffolk, UK, 1999; Chapters 1, 5, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tuck, C.D.S.; Powell, C.A.; Nuttall, J. Corrosion of Copper and Its Alloys. In Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Niece, S. Silver Plating on copper, bronze and brass. Antiqu. J. 1990, 70, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Niece, S. Silvering. In Metal Plating and Patination; La Niece, S., Craddock, P., Eds.; Butterworth Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1993; pp. 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gugua, E.C.; Ujah, C.O.; Asadu, C.O.; Von Kallon, D.V.; Ekwueme, B.N. Electroplating in the modern era, improvements and challenges: A review. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejneru, C.; Savin, C.; Perju, M.C.; Burduhos-Nergis, D.D.; Costea, M.; Bejinariu, C. Studies on galvanic corrosion of metallic materials in marine medium. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Research—ICIR EUROINVENT, Iasi, Romania, 16–17 May 2019; IOP Publishing: Galati, Romania, 2019; Volume 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaoras, D.; Kassis, D.; Perivoliotis, L.; Pagonis, P.; Hondronasios, A.; Nittis, K. Temperature and Salinity Variability in the Greek Seas Based on POSEIDON Stations Time Series: Preliminary Results. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2019, 14, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Boyatzis, S.; Giannoulaki, M.; Malea, E.; Petrou, M.; Rapti, S. Metals in association with organic and inorganic materials: Marine composite artefacts (Section 4, 4.4). In Bridging the Gap. Corrosion Science For Heritage Contexts, 1st ed.; Neff, D., Grassini, S., Watkinson, D., Emmerson, N., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2025; Volume 73, ISBN 9780443186905. [Google Scholar]

- Proenca, L.; Fonseca, I.T.E.; Neto, M.M.M. Electrochemical studies on the corrosion of brass in seawater under anaerobic conditions. J. Solid-State Electrochem. 2008, 12, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, E.N. A Dictionary of Alloys; Frederick Muller: London, UK, 1969; pp. 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T.; Zhang, W.; Li, N.; Liu, X.; Han, L.; Dai, W. Surface characterization and corrosion behaviour of 90/10 copper-nickel alloy in marine environment. Materials 2019, 12, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.I.S.; Mendonça, M.H.; Fonseca, I.T.E. Corrosion of Brass in natural and artificial seawater. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2006, 36, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birn, J.; Skalski, I. 1-Corrosion behaviour of non-ferrous alloys in seawater in the Polish marine industry. In Corrosion Behaviour and Protection of Copper and Aluminium; Féron, D., Ed.; European Federation of Corrosion (EFC) Series; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Li, K.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Qin, C.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, W.; Zhai, Y.; Huang, G. Stress Corrosion Cracking of Copper–Nickel Alloys: A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Giannoulaki, M.; Guilminot, E. Nonferrous metals (Chapter 11). In Conservation of Cultural Heritage from Marine and Freshwater Sites; Godfrey, I.M., Gregory, D.J., Eds.; Routledge Publishers: New York, NY, USA, forthcoming 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-F.; Esmacher, M.J.; Kotwica, D. Denickelification and Dezincification of Copper Alloys in Water Environments. Microsc. Microanal. 2015, 21 (Suppl. S3), 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mansfeld, F.; Little, B. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of copper-based material exposed to natural seawater. Electrochem. Acta 1992, 37, 2291–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoropoulou, C.; Giannoulaki, M.; Argyropoulos, V. A condition assessment of Hellenistic leaded bronze bosses from Piraeus, Greece, using scanning electron microscopy with energy dispersive x-ray analysis (SEM-EDX). Conserv. 360 Diagnosis. Before, During, After, Vol. 2. 2022. Available online: https://monografias.editorial.upv.es/index.php/con_360/article/view/400 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Scott, D.A. Copper and Bronze in Art: Corrosion, Colorants, Conservation; The J. Paul Getty Museum: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, I. Formation of marine concretions on copper and its alloys. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 1982, 11, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, N.A.; MacLeod, I.D. Corrosion of metals. In Conservation of Marine Archaeological Objects; Pearsoned, C., Ed.; Butterworth & Co. Ltd.: London, UK, 1987; pp. 68–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, H.; Payer, J. The effect of silver chloride formation on the kinetics of silver dissolution in chloride solution. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 2781–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, V. The deterioration of silver alloys and some aspects of their conservation. Rev. Conserv. 2001, 2, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, J.D. The tarnishing of silver by organic sulfur vapors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1982, 129, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, M.B.; Little, B.J. Corrosion mechanisms for copper and silver objects in near-surface environments. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 1992, 31, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Kareem, O.; Al-Zahrani, A.; Al-Sadoun, A. Authentication and conservation of marine archaeological coins excavated from underwater of the Red Sea, Saudi Arabia. Mediterr. Archaeol. Archaeom. 2016, 16, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, I.D.; Schindelholz, E. Surface Analysis of Corroded Silver Coins from the Wreck of the San Pedro De Alcantara (1786). In Proceedings of the Metal 2004 National Museum of Australia Canberra ACT, Canberra, ACT, Australia, 4–8 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dungworth, D. Roman copper alloys: Analysis of artefacts from Northern Britain. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997, 24, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeper-Attia, M.-A.; Maniguet, T. Twenty years of conservation of plated brass instruments at the Musse de la musique in Paris. In Proceedings of the I COM Committee for Conservation 18th Triennial Meeting, Copenhagen, Denmark, 4–8 September 2017; ISBN 978-92-9012-426-9. [Google Scholar]

- Palomar, T.; Cano, E.; Ramirez, B. A comparative study of cleaning methods for tarnished silver. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 17, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomar, T.; Cano, E.; Ramirez, B. Evaluation of Cleaning Treatments for Tarnished Silver: The Conservator’s Perspective. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2018, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wharton, G.; Lansing Maish, S.; Ginell, W.S. A Comparative Study of Silver Cleaning Abrasives. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2013, 29, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, J.M.; Vassiliou, P.; Georgiza, E. Electrochemical Cleaning of Artificially Tarnished. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 7223–7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrigny, C.; Baudin, C.; Jeanneret, R.; Bussy, G. A new electrolytic pencil for the local cleaning of silver tarnish. Stud. Conserv. 2025, 61, 150612094103006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrigny, C.; Jerome, M.; Lacoudre, N. Surface Cleaning of Silvered Brass Wind Instruments Belonging to the Sax Collection. Corros. Australas. 1993, 18, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Aldaz, A.; Espana, T.; Montiel, V.; Lopez-Segura, M. A Simple Tool for the Electrolytic Restoration of Archaeological Objects with Localized Corrosion. Stud. Conserv. 1986, 31, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).