Neolithic Fishing Stations at Šventoji, Southeastern Baltic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Site Description

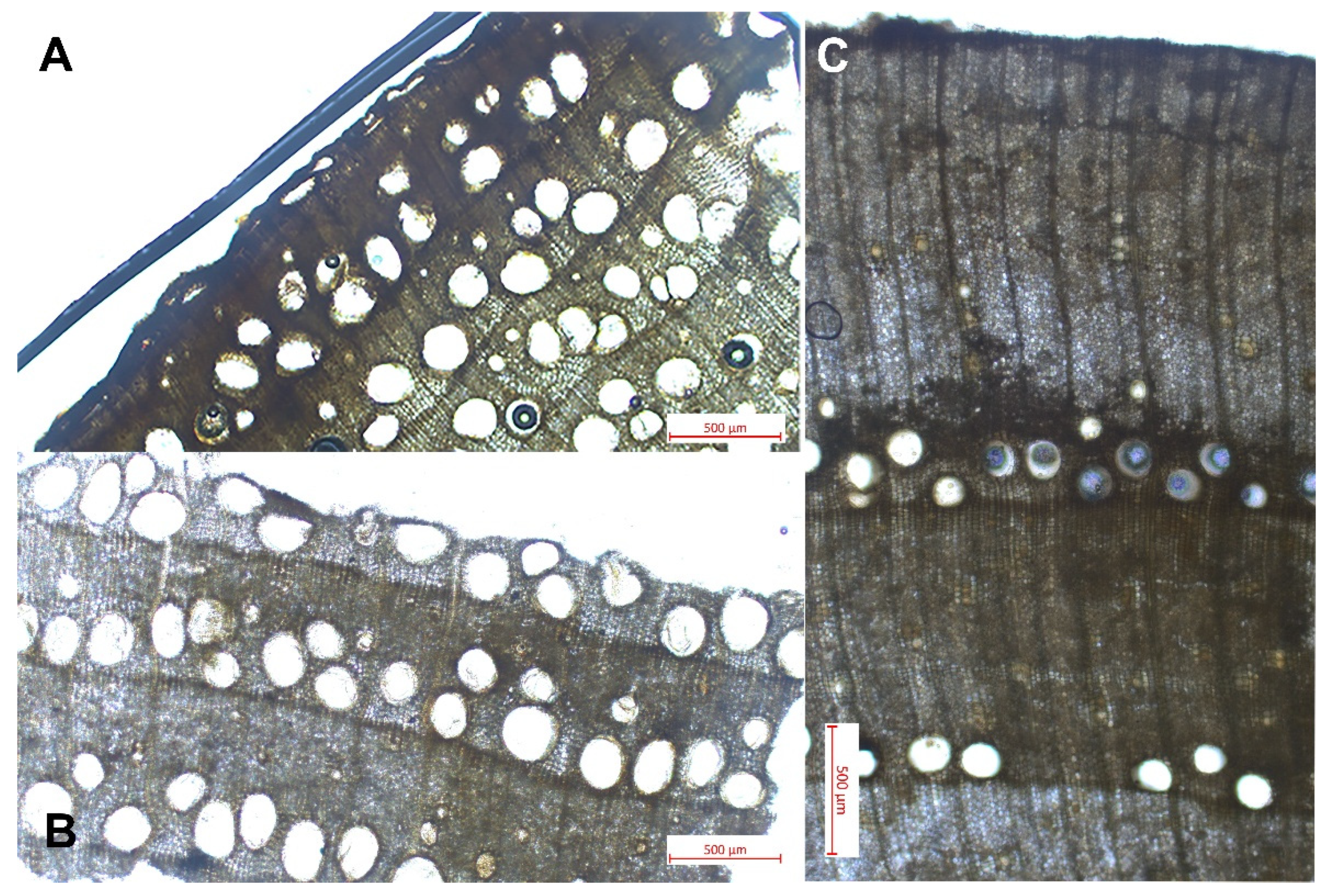

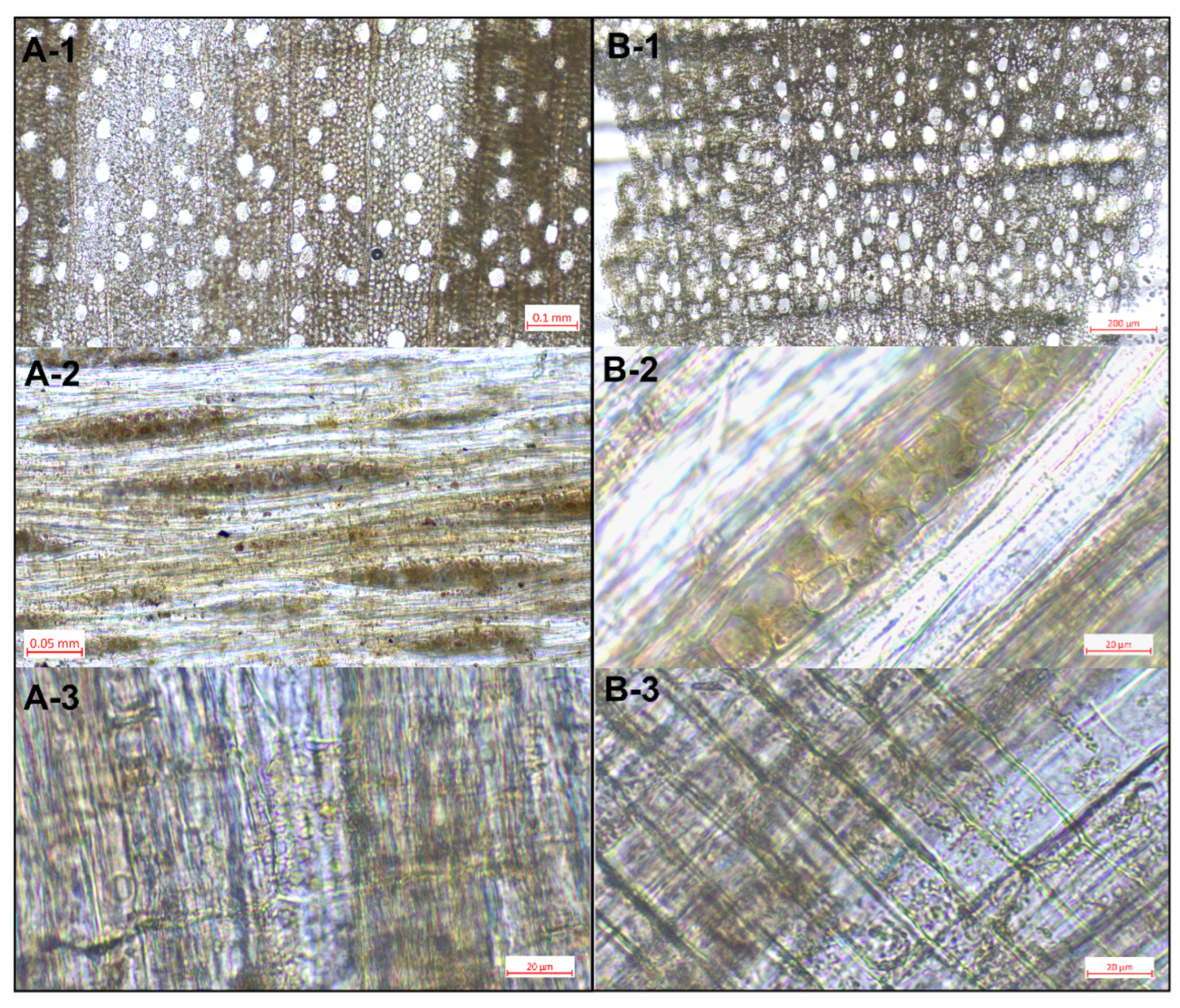

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

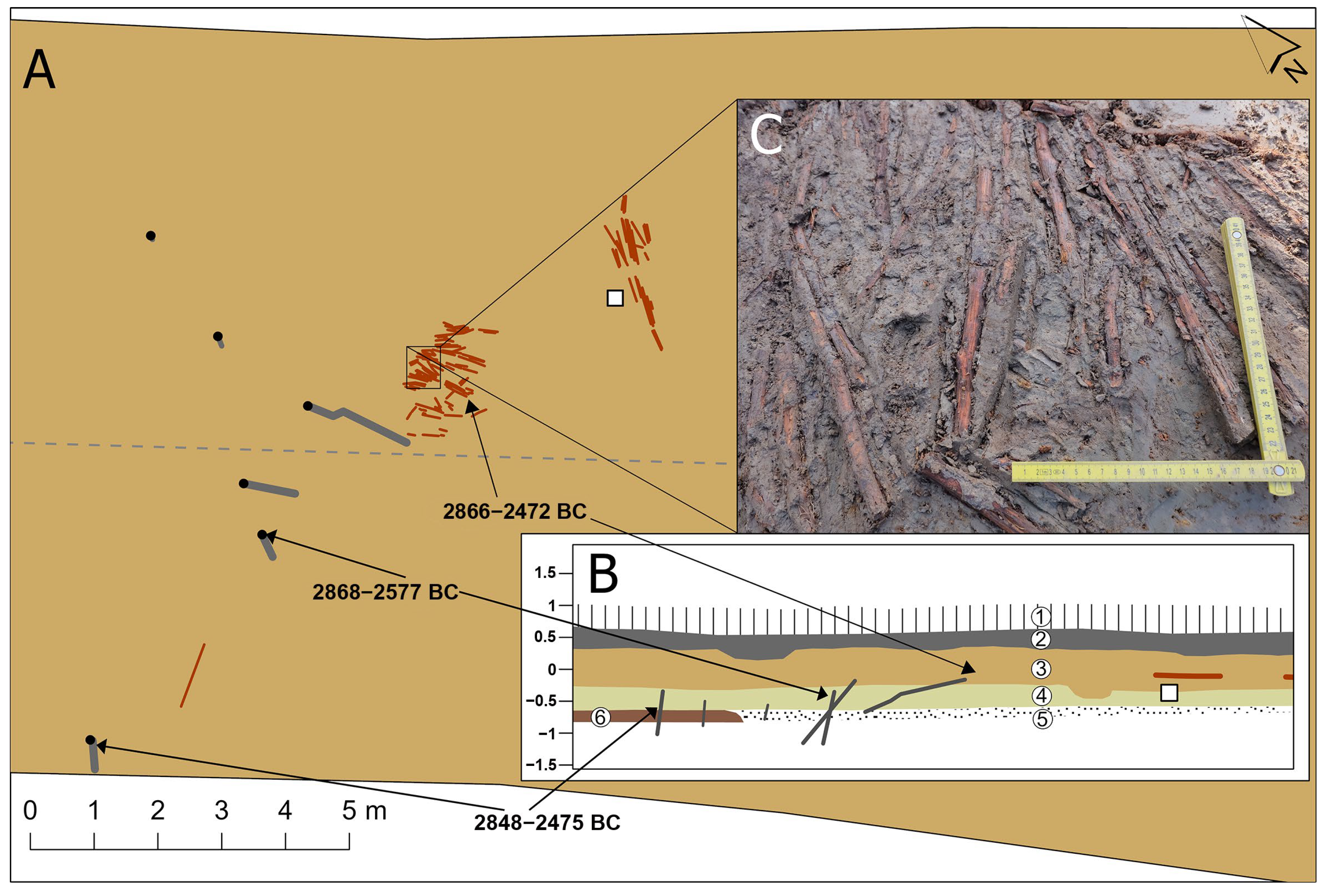

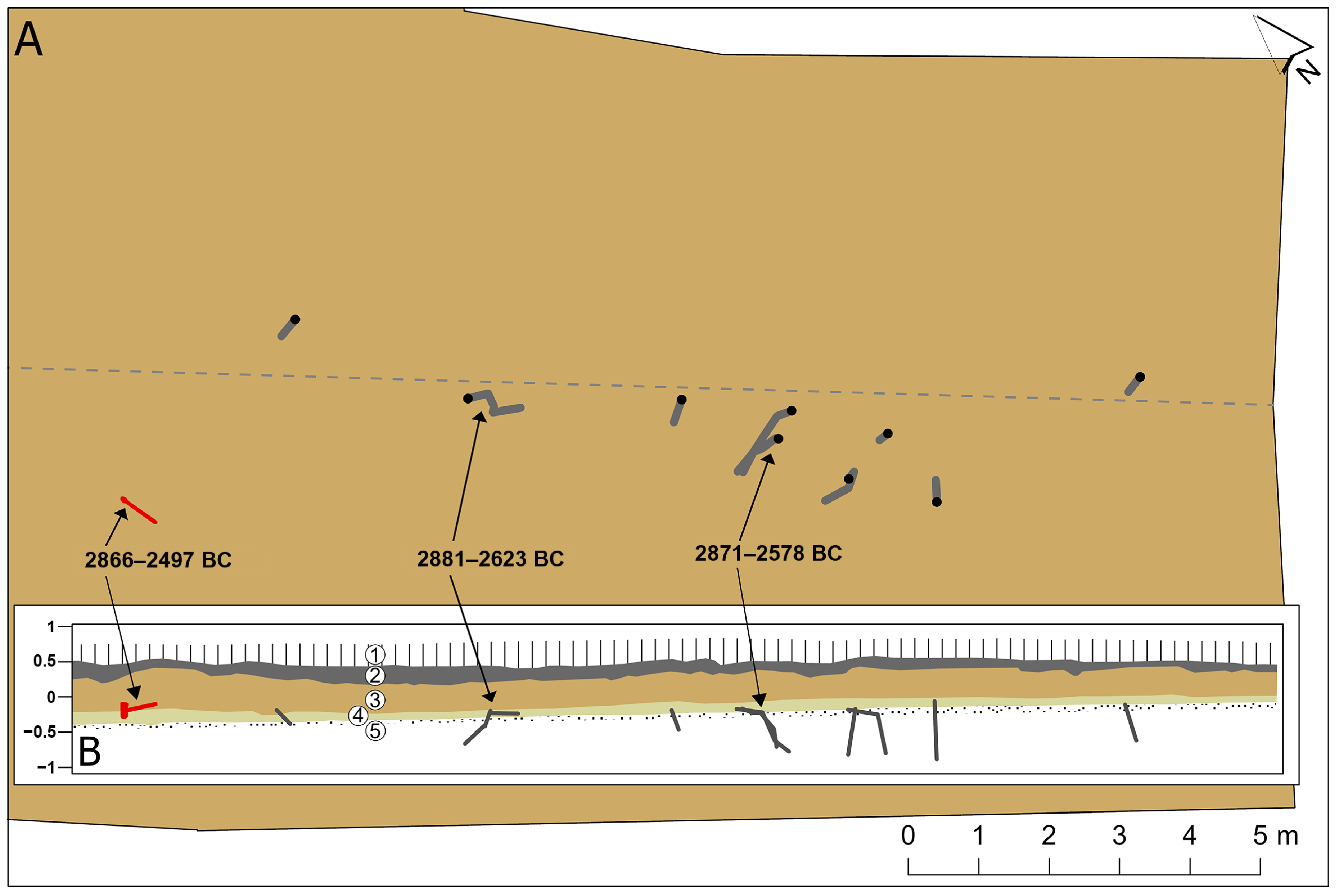

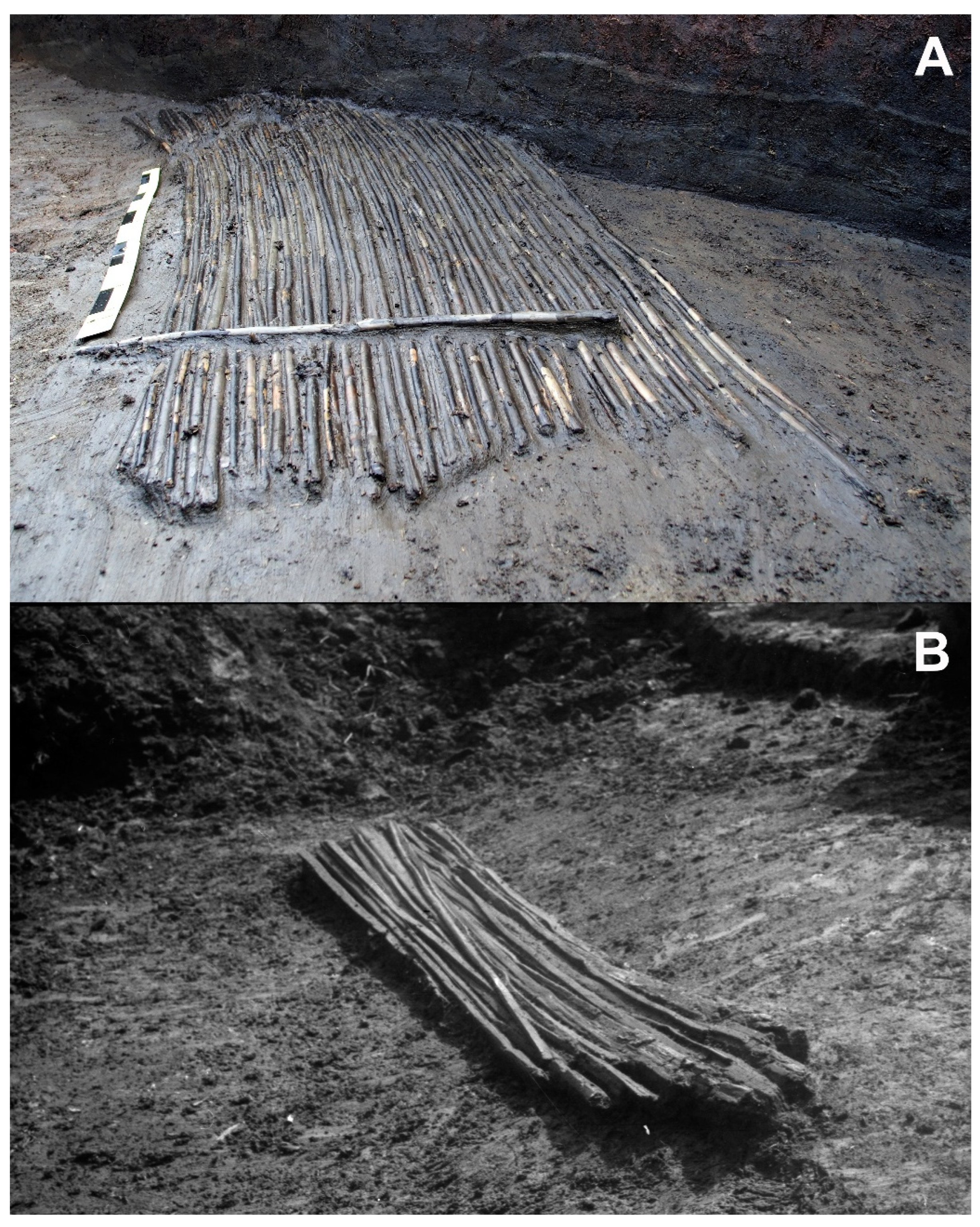

4.1. Fish Fences and Traps

4.2. Shaft-Hole Battle Axes

5. Discussion

5.1. Construction and Function of Neolithic Fishing Stations

5.2. Dating of Neolithic Fishing Sites

5.3. Users of Neolithic Fishing Sites

5.4. Concerning De-Neolithisation in the Southeastern Baltic

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malmström, H.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Thomas, M.G.; Brandström, M.; Storå, J.; Molnar, P.; Andersen, P.K.; Bendixen, C.; Holmlund, G.; Götherström, A.; et al. Ancient DNA Reveals Lack of Continuity between Neolithic Hunter-Gatherers and Contemporary Scandinavians. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1758–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haak, W.; Balanovsky, O.; Sanchez, J.J.; Koshel, S.; Zaporozhchenko, V.; Adler, C.J.; Der Sarkissian, C.S.I.; Brandt, G.; Schwarz, C.; Nicklisch, N.; et al. Ancient DNA from European Early Neolithic Farmers Reveals Their Near Eastern Affinities. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; et al. Massive Migration from the Steppe Was a Source for Indo-European Languages in Europe. Nature 2015, 522, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieson, I.; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, S.; Posth, C.; Szécsényi-Nagy, A.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Olalde, I.; Broomandkhoshbacht, N.; Candilio, F.; Cheronet, O.; et al. The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe. Nature 2018, 555, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, J.M.; Lucarini, G.; Tassie, G.J.; Rowland, J.M. (Eds.) Revolutions; Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. Neolithization and Population Replacement in Britain: An Alternative View. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2022, 32, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, D. Not Going Anywhere? Migration as a Social Practice in the Early Neolithic Linearbandkeramik. Quat. Int. 2020, 560–561, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szécsényi-Nagy, A.; Brandt, G.; Haak, W.; Keerl, V.; Jakucs, J.; Möller-Rieker, S.; Köhler, K.; Mende, B.G.; Oross, K.; Marton, T.; et al. Tracing the Genetic Origin of Europe’s First Farmers Reveals Insights into Their Social Organization. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282, 20150339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, J.O.; Krumhardt, K.M.; Zimmermann, N. The Prehistoric and Preindustrial Deforestation of Europe. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 3016–3034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, R.; Philippsen, B.; Persson, P. Reconsidering the Pitted Ware Chronology: A Temporal Fixation of the Scandinavian Neolithic Hunters, Fishers and Gatherers. Praehist. Z. 2021, 96, 44–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Pranckėnaitė, E.; Matiukas, A.; Osipowicz, G.; Peseckas, K.; Kozakaitė, J.; Damušytė, A.; Gál, E.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Robson, H.K. Garnys: An Underwater Riverine Site with Delayed Neolithisation in the Southeastern Baltic. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 52, 104232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsch, E. Traktbegerkultur-Megalitkultur: En Studie Av Øst-Norges Eldste, Neolitiske Gruppe; Universitetets Oldsaksamling: Oslo, Norway, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.V.; Persson, P.; Solheim, S. De-Neolithisation in Southern Norway Inferred from Statistical Modelling of Radiocarbon Dates. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2019, 53, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, R. Beyond the Neolithic Transition: The ‘de-Neolithisation’of South Scandinavia. In NW Europe in Transition: The Early Neolithic in Britain and South Sweden; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Kluczynska, G.; Kisielienė, D.; Skipitytė, R.; Peseckas, K.; Matuzevičiūtė, S.; Lukešová, H.; Lucquin, A.; Craig, O.E.; Robson, H.K. Fishers of The Corded Ware Culture in The Eastern Baltic. ACAR 2020, 91, 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, H.K.; Skipitytė, R.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Lucquin, A.; Heron, C.; Craig, O.E.; Piličiauskas, G. Diet, Cuisine and Consumption Practices of the First Farmers in the Southeastern Baltic. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 4011–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G. Lietuvos Pajūris Subneolite Ir Neolite. Žemės Ūkio Pradžia. Liet. Archeol. 2016, 42, 25–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rimantienė, R. Die Steinzeitfischer an der Ostseelagune in Litauen; Litauisches Nationalmuseum: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2005; ISBN 978-9955-415-44-2. [Google Scholar]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Kisielienė, D.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Gaižauskas, L.; Kalinauskas, A. Comb Ware Culture in Lithuania: New Evidence from Šventoji 43. Liet. Archeol. 2019, 45, 67–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Vaikutienė, G.; Kisielienė, D.; Damušytė, A.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Peseckas, K.; Gaižauskas, L. A Closer Look at Šventoji 2/4—A Stratified Stone Age Fishing Site in Coastal Lithuania, 3200–2600 Cal BC. Liet. Archeol. 2019, 45, 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipowicz, G.; Piličiauskas, G.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Bosiak, M. “Seal Scrapers” from Šventoji—In Search of Their Possible Function. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 27, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipowicz, G.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Orłowska, J.; Piličiauskas, G. An Occasional Ornament, Part of Clothes or Just a Gift for Ancestors? The Results of Traceological Studies of Teeth Pendants from the Subneolithic Sites in Šventoji, Lithuania. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 29, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Mažeika, J.; Gaidamavičius, A.; Vaikutienė, G.; Bitinas, A.; Skuratovič, Ž.; Stančikaitė, M. New Archaeological, Paleoenvironmental, and 14C Data from the Šventoji Neolithic Sites, NW Lithuania. Radiocarbon 2012, 54, 1017–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archaeological Heritage Maintenance. Available online: https://www.e-tar.lt/portal/en/legalAct/TAR.8B2A750536FF/qZHCgJXGQK (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Schoch, W.; Heller, I.; Schweingruber, F.H.; Kienast, F. Wood Anatomy of Central European Species; Swiss Federal Institute for Forest: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, E.A. Inside Wood–A Web Resource for Hardwood Anatomy. Iawa J. 2011, 32, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukienė, R. Žemaitiškės 2-Osios Polinės Gyvenvietės Medinių Konstrukcijų Anatominė Analizė. Liet. Archeol. 2004, 26, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Sass-Klaassen, U.; Vernimmen, T.; Baittinger, C. Dendrochronological Dating and Provenancing of Timber Used as Foundation Piles under Historic Buildings in The Netherlands. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2008, 61, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šapolaitė, J.; Kazakevičiūtė-Jakučiūnienė, L.; Garbarienė, I.; Ežerinskis, Ž. Overview of Pretreatment Protocols and14 C Measurement Quality with AMS Facilities (SSAMS and LEA) at the Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Lithuania: Insights from Intercomparison Tests. Radiocarbon 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznan Radiocarbon Laboratory. Available online: https://radiocarbon.pl/en/poznanskie-laboratorium-radioweglowe-plr/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Bronk Ramsey, C. Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon 2009, 51, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.N.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Bronk Ramsey, C.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M.; et al. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curve (0–55 Cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, P.C. Use-Wear Analysis of Flaked Stone Tools; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-8165-0861-7. [Google Scholar]

- van Gijn, A.L. The Wear and Tear of Flint: Principles of Functional Analysis Applied to Dutch Neolithic Assemblages; Analecta praehistorica Leidensia; Universiteit Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1989; ISBN 978-90-73368-02-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sidéra, I. Les Assemblages Osseux En Bassins Parisien et Rhénan Du VI e Au IV e Millénaires B.-C. Histoire, Techno-Économie et Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Paris I, Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Juel Jensen, H. Flint Tools and Plant Working: Hidden Traces of Stone Age Technology: A Use Wear Study of Some Danish Mesolithic and TRB Implements; Aarhus University Press: Aarhus C, Denmark, 1994; ISBN 978-87-7288-454-7. [Google Scholar]

- Osipowicz, G. Narzędzia Krzemienne w Epoce Kamienia Na Ziemi Chełmińskiej: Studium Traseologiczne; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika: Toruń, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buc, N. Experimental Series and Use-Wear in Bone Tools. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, G.K.; Wilson, S.R. Procedures for comparing and combining radiocarbon age determinations: A critique. Archaeometry 1978, 20, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Włodarczak, P. Kultura ceramiki sznurowej na Wyżynie Małopolskiej; Wydawnictwo Instytutu Archeologii i Etnologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk. Oddział: Kraków, Poland, 2006; ISBN 978-83-923556-0-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rimantienė, R. Lietuvos TSR Archeologijos Atlasas: Akmens Ir Žalvario Amžiaus Paminklai; Mintis: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1974; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, D.J.Q. Later Mesolithic Fishing Strategies and Practices in Denmark; BAR International Series; J. and E. Hedges: Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-1-84171-328-1. [Google Scholar]

- Connaway, J.M. Fishweirs: A World Perspective with Emphasis on the Fishweirs of Mississippi; Archaeological Report; Mississippi Department of Archives and History: Jackson, MS, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-938896-89-0. [Google Scholar]

- Leineweber, R.; Lübke, H.; Hellmund, M.; Döhle, H.-J.; Klooß, S. A Late Neolithic Fishing Fence in Lake Arendsee, Sachsen-Anhalt, Germany. In Submerged Prehistory; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lozovski, V.M.; Lozovskaya, O.; Clemente-Conte, I.; Mazurkevich, A.; Gassiot Ballbè, E. Wooden Fishing Structures on the Stone Age Site Zamostje 2. In Zamostje 2: Lake Settlement of the Mesolithic and Neolithic Fisherman in Upper Volga Region; IHMC RAS: St Petersburg, Russia, 2013; pp. 46–75. [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, S.; Robson, H.K.; Philippsen, B.; Stafseth, T.; Brinch, M.; Schmölcke, U.; Astrup, P.M.; Casati, C.; Henriksen, M.B.; Uldum, O.; et al. Fishing with Stationary Wooden Structures in Stone Age Denmark: New Evidence from Syltholm Fjord, Southern Lolland. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 2024, 90, 147–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girininkas, A. Kretuono 1C Gyvenvietės Bendruomenės Gyvensena. Liet. Archeol. 2004, 25, 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Girininkas, A. Baltų Kultūros Ištakos; Savastis: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, S.H. Coastal Adaptation and Marine Exploitation in Late Mesolithic Denmark-with Special Emphasis on the Limfjord Region. In Man and Sea in the Mesolithic. Coastal Settlement Above and Below Present Sea Level; Oxbow books: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, L. 7000 Years of Fishing: Stationary Fishing Structures in the Mesolithic and Afterwards. In Man and Sea in the Mesolithic. Coastal Settlement Above and Below Present Sea Level; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- The Prehistory of the Netherlands; Louwe Kooijmans, L.P., Ed.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 978-90-5356-160-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bērziņš, V. Sārnate: Living by a Coastal Lake During the East Baltic Neolithic; Acta Universitatis Ouluensis. B, Humaniora; Oulun yliopisto: Oulu, Finland, 2008; ISBN 978-951-42-8940-8. [Google Scholar]

- Peseckas, K. Gamtinė Aplinka Ir Medienos Panaudojimas Lietuvos Teritorijoje Holocene Archeologinės Medienos Anatominių Tyrimų Duomenimis. Ph.D. Thesis, Vilniaus Universitetas, Vilnius, Lithuania, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, S.W. Problems of Dating Spread on Radiocarbon Calibration Curve Plateaus: The 1620–1540 BC Example and the Dating of the Therasia Olive Shrub Samples and Thera Volcanic Eruption. Radiocarbon 2024, 66, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G. Virvelinės Keramikos Kultūra Lietuvoje 2800–2400 cal BC; Lietuvos Istorijos Institutas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2018; ISBN 978-609-8183-48-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zagorska, I. The First Radiocarbon Datings from Zvejnieki Stone Age Burial Ground, Latvia. Iskos 1997, 11, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lougas, L.; Kriiska, A.; Maldre, L. New Dates for the Late Neolithic Corded Ware Culture Burials and Early Husbandry in the East Baltic Region. Archaeofauna 2007, 16, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Skipitytė, R.; Oras, E.; Lucquin, A.; Craig, O.E.; Robson, H.K. The Globular Amphora Culture in the Eastern Baltic: New Discoveries. Acta Archaeol. 2023, 92, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Jankauskas, R.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Dupras, T. Reconstructing Subneolithic and Neolithic Diets of the Inhabitants of the SE Baltic Coast (3100–2500 Cal BC) Using Stable Isotope Analysis. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2017, 9, 1421–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, S.A. Syltholm: Denmark’s Largest Stone Age Excavation. Mesolith. Misc. 2016, 24, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, G. Woodland in the Neolithic of Northern Europe: The Forest as Ancestor; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ennos, A.R.; Oliveira, J.A.V. The Mechanical Properties of Wood and the Design of Neolithic Stone Axes. J. Lithic Stud. 2020, 8, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspé, O.; Findlay, C.; Jacquemart, A. Sorbus Aucuparia L. J. Ecol. 2000, 88, 910–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardío, J.; Arnal, A.; Lázaro, A. Ethnobotany of the Crab Apple Tree (Malus Sylvestris (L.) Mill., Rosaceae) in Spain. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 795–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaižauskas, L.; Peseckas, K.; Piličiauskienė, G. Šventosios 5 Radimvietė. Archeol. Tyrinėjimai Liet. 2021 Met. 2022, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- EUFORGEN Acer Campestre. Field Maple. Available online: https://www.euforgen.org/species/acer-campestre (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Rimantienė, R. Nida: Senųjų Baltų Gyvenvietė; Mokslas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Olausson, D. Battleaxes: Home-Made, Made to Order or Factory Products. In Proceedings of the Third Flint Alternatives Conference at Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden, 18–20 October 1996; Knutsson, K., Ed.; Uppsala University: Uppsala, Sweden; 1998; pp. 125–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wentink, K. Stereotype: The Role of Grave Sets in Corded Ware and Bell Beaker Funerary Practices; Sidestone Press: Leiden, Holland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Piličiauskas, G.; Jankauskas, R.; Piličiauskienė, G.; Craig, O.E.; Charlton, S.; Dupras, T. The Transition from Foraging to Farming (7000–500 Cal BC) in the SE Baltic: A Re-Evaluation of Chronological and Palaeodietary Evidence from Human Remains. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 14, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebbesen, K. The Battle Axe Period: Stridsøksetid; Attika: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mittnik, A.; Wang, C.-C.; Pfrengle, S.; Daubaras, M.; Zariņa, G.; Hallgren, F.; Allmäe, R.; Khartanovich, V.; Moiseyev, V.; Tõrv, M.; et al. The Genetic Prehistory of the Baltic Sea Region. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saag, L.; Varul, L.; Scheib, C.L.; Stenderup, J.; Allentoft, M.E.; Saag, L.; Pagani, L.; Reidla, M.; Tambets, K.; Metspalu, E.; et al. Extensive Farming in Estonia Started through a Sex-Biased Migration from the Steppe. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 2185–2193.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmyt, M. Społeczności Kultury Amfor Kulistych Na Kujawach; PSO: Poznań, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Czebreszuk, J.; Szmyt, M. Identities, Differentiation and Interactions on the Central European Plain in the 3rd Millennium BC. In Sozialarchäologische Perspektiven: Gesellschaftlicher Wandel 5000–1500 v. Chr. zwischen Atlantik und Kaukasus; Verlag Philipp von Zabern: Mainz, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fornander, E. Dietary Diversity and Moderate Mobility: Isotope Evidence from Scanian Battle Axe Culture Burials. J. Nord. Archaeol. Sci. 2013, 18, 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak-Martens, L.; Brinkkemper, O.; Oudemans, T.F.M. What’s for Dinner? Processed Food in the Coastal Area of the Northern Netherlands in the Late Neolithic. Veget Hist. Archaeobot 2015, 24, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjögren, K.-G.; Price, T.D.; Kristiansen, K. Diet and Mobility in the Corded Ware of Central Europe. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werens, K.; Szczepanek, A.; Jarosz, P. Light Stable Isotope Analysis of Diet in Corded Ware Culture Communities: Święte, Jarosław District, South-Eastern Poland. Balt.-Pontic Stud. 2018, 23, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

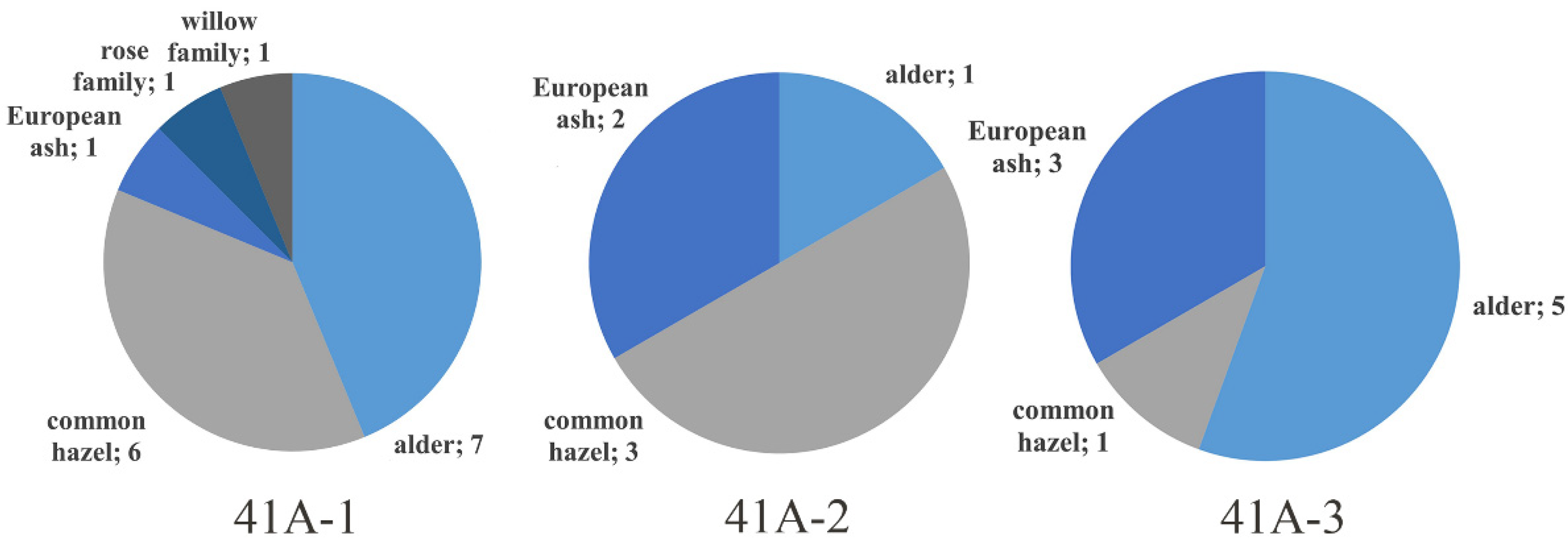

| Horizontal Shoots (0.5–2 cm) | Vertical Piles (4–8 cm) | Vertical Stakes (1–2 cm) | Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site and Species | B-C | N/I | Total | A | B | B-C | C | N/I | Total | A-B | B-C | C | N/I | Total | |

| 41A-1 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 2 | – | 9 | – | 5 | 16 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 41 |

| Alnus sp. | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | – | 3 | 7 | – | – | – | – | – | 7 |

| Corylus avellana | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | – | 4 | – | – | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 21 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | – | 2 | 2 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 3 |

| Rosaceae | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Salix sp. | 2 | 1 | 3 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| 41A-2 | – | 7 | 7 | – | 1 | – | 1 | 4 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | 13 |

| Alnus sp. | – | 3 | 3 | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 4 |

| Corylus avellana | – | 4 | 4 | – | – | – | 1 | 2 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | 7 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| 41A-3 | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | 8 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | 9 |

| Alnus sp. | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 5 |

| Corylus avellana | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Fraxinus excelsior | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | v | 2 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | 3 |

| Total | 4 | 12 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 17 | 31 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 63 |

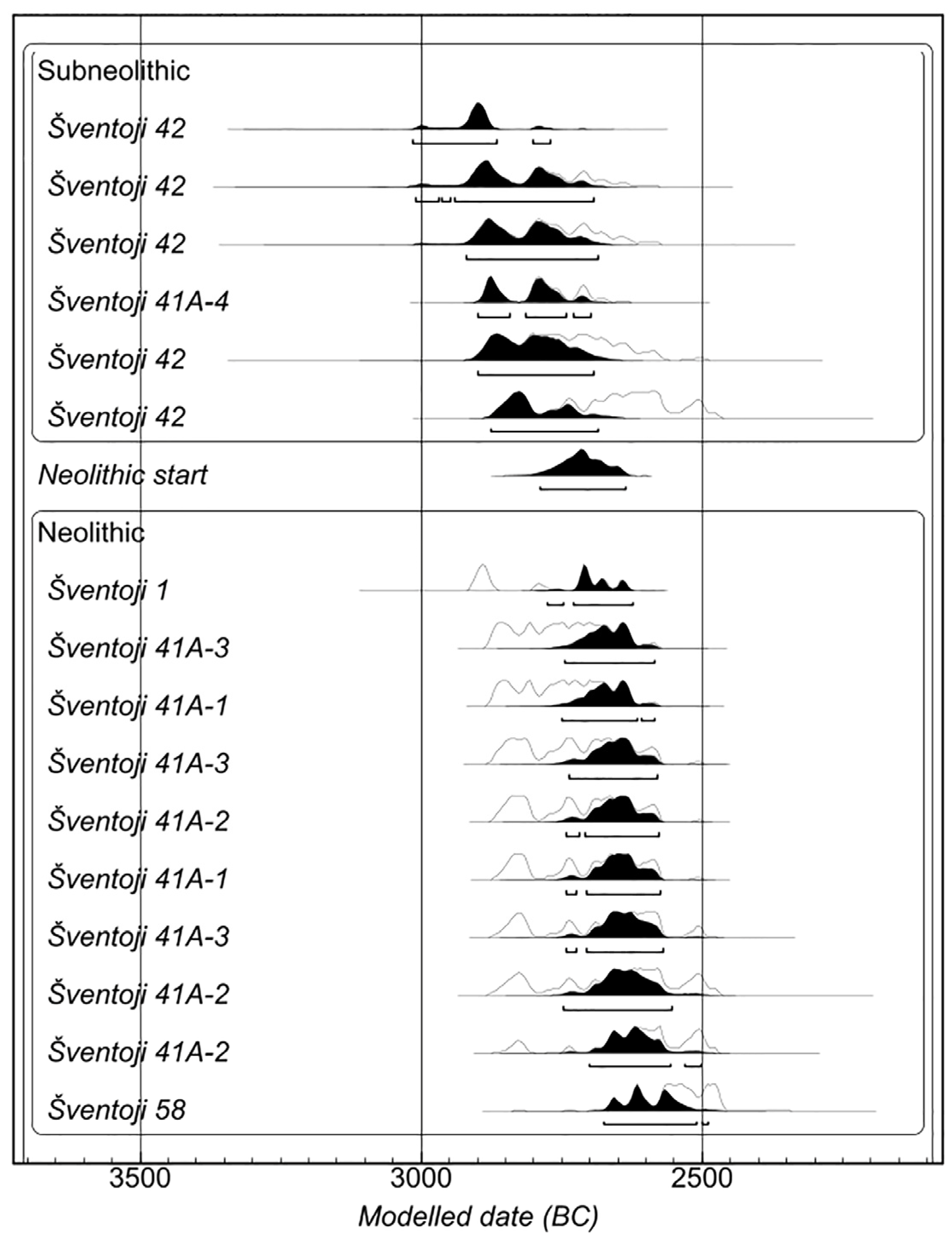

| No. | Fishing Site | Period | Lab Code | Date BP | Cal BC/AD (95.4%) | Description, ID | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Šventoji 1 | Neolithic | Poz-197686 | 4255 ± 35 | 2923–2701 | wooden (Rosaceae) handle of the stone battle axe, EM2070:510 | this study |

| 2 | Šventoji 41A-1 | Neolithic | FTMC-UJ17-11 | 4150 ± 29 | 2876–2627 | wooden (willow family) stake, ID 158 | this study |

| 3 | Šventoji 41A-1 | Neolithic | FTMC-UJ17-10 | 4111 ± 28 | 2866–2574 | wooden (alder) pile, ID 124 | this study |

| 4 | Šventoji 41A-2 | Neolithic | Poz-193160 | 4065 ± 35 | 2848–2475 | wooden (alder) pile, ID 56 | this study |

| 5 | Šventoji 41A-2 | Neolithic | Poz-193348 | 4080 ± 50 | 2866–2475 | wooden (hazel) shoot, ID 43 | this study |

| 6 | Šventoji 41A-2 | Neolithic | Poz-193159 | 4120 ± 30 | 2868–2577 | wooden (hazel) pile, ID 35 | this study |

| 7 | Šventoji 41A-3 | Neolithic | Poz-193347 | 4095 ± 35 | 2866–2497 | wooden (maple) handle of the stone battle axe, ID 37 | this study |

| 8 | Šventoji 41A-3 | Neolithic | Poz-193158 | 4125 ± 35 | 2871–2578 | wooden (alder) pile, ID 30 | this study |

| 9 | Šventoji 41A-3 | Neolithic | Poz-192941 | 4155 ± 35 | 2881–2623 | wooden (ash) pile, ID 28 | this study |

| 10 | Šventoji 41A-4 | Subneolithic | Poz-192943 | 4205 ± 30 | 2897–2674 | wooden (alder) pile, ID 80 | this study |

| 11 | Šventoji 42 | Subneolithic | Tln-3415 | 4177 ± 60 | 2900–2580 | wooden (alder) pile, ID 115 | this study |

| 12 | Šventoji 42 | Subneolithic | Tln-3421 | 4215 ± 60 | 2920–2620 | wooden (alder) pile, ID 118 | this study |

| 13 | Šventoji 42 | Subneolithic | Tln-3449 | 4239 ± 60 | 3010–2630 | wooden pile, ID 5 | this study |

| 14 | Šventoji 42 | Subneolithic | Vs-1956 | 4280 ± 40 | 3018–2762 | wooden pile, ID 3 | [23] |

| 15 | Šventoji 42 | Subneolithic | Vs-1981 | 4090 ± 50 | 2872–2491 | wooden pile, ID 14 | [23] |

| 16 | Šventoji 58 | Neolithic | Poz-77557 | 4000 ± 35 | 2619–2462 | wooden (hazel) shoot of fish screen, test-pit 101, ID 18 | [15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piličiauskas, G.; Peseckas, K.; Kalinauskas, A.; Osipowicz, G. Neolithic Fishing Stations at Šventoji, Southeastern Baltic. Heritage 2025, 8, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110442

Piličiauskas G, Peseckas K, Kalinauskas A, Osipowicz G. Neolithic Fishing Stations at Šventoji, Southeastern Baltic. Heritage. 2025; 8(11):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110442

Chicago/Turabian StylePiličiauskas, Gytis, Kęstutis Peseckas, Algirdas Kalinauskas, and Grzegorz Osipowicz. 2025. "Neolithic Fishing Stations at Šventoji, Southeastern Baltic" Heritage 8, no. 11: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110442

APA StylePiličiauskas, G., Peseckas, K., Kalinauskas, A., & Osipowicz, G. (2025). Neolithic Fishing Stations at Šventoji, Southeastern Baltic. Heritage, 8(11), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110442