Techniques and Stylistic Characteristics of Stucco Decorations in Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

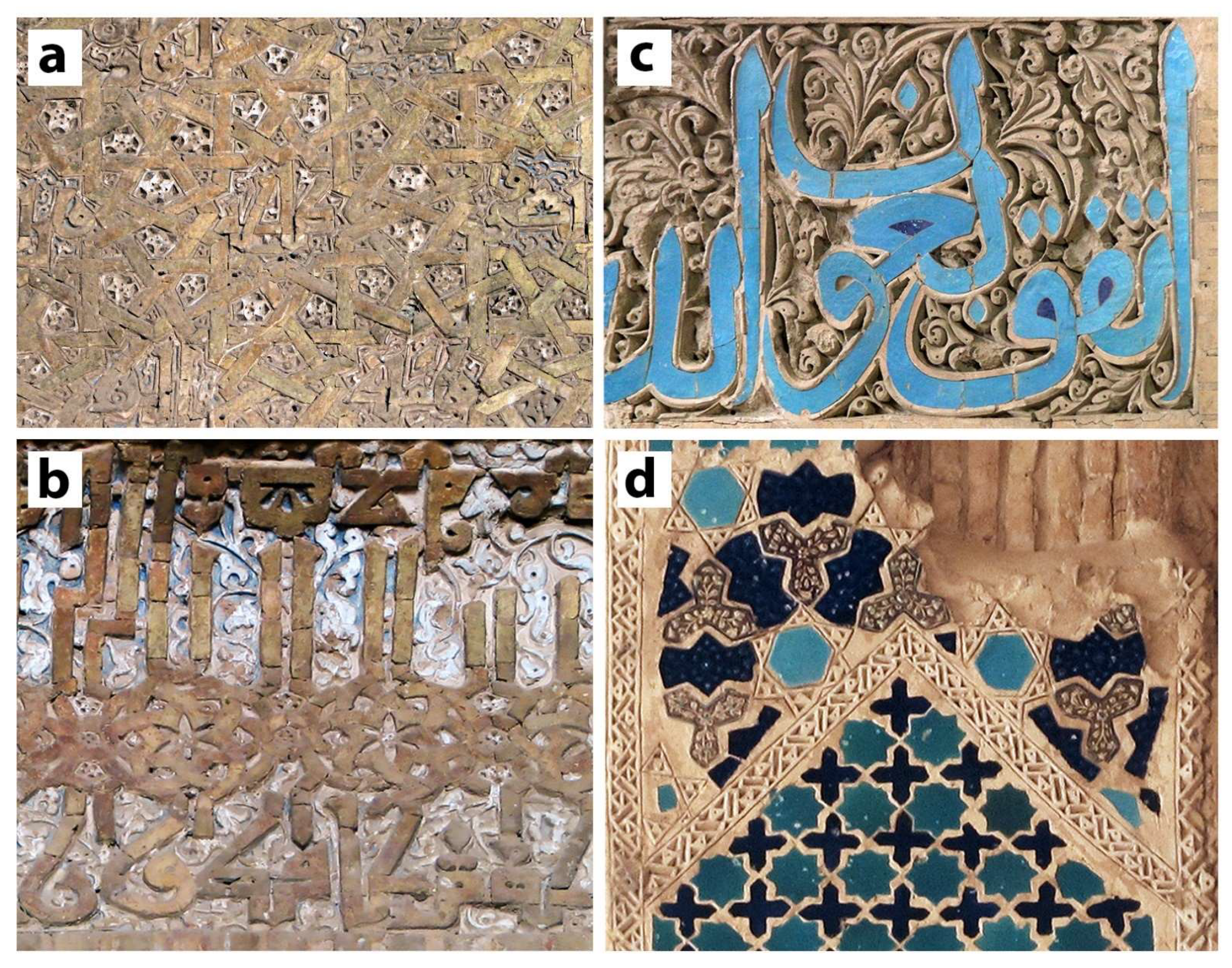

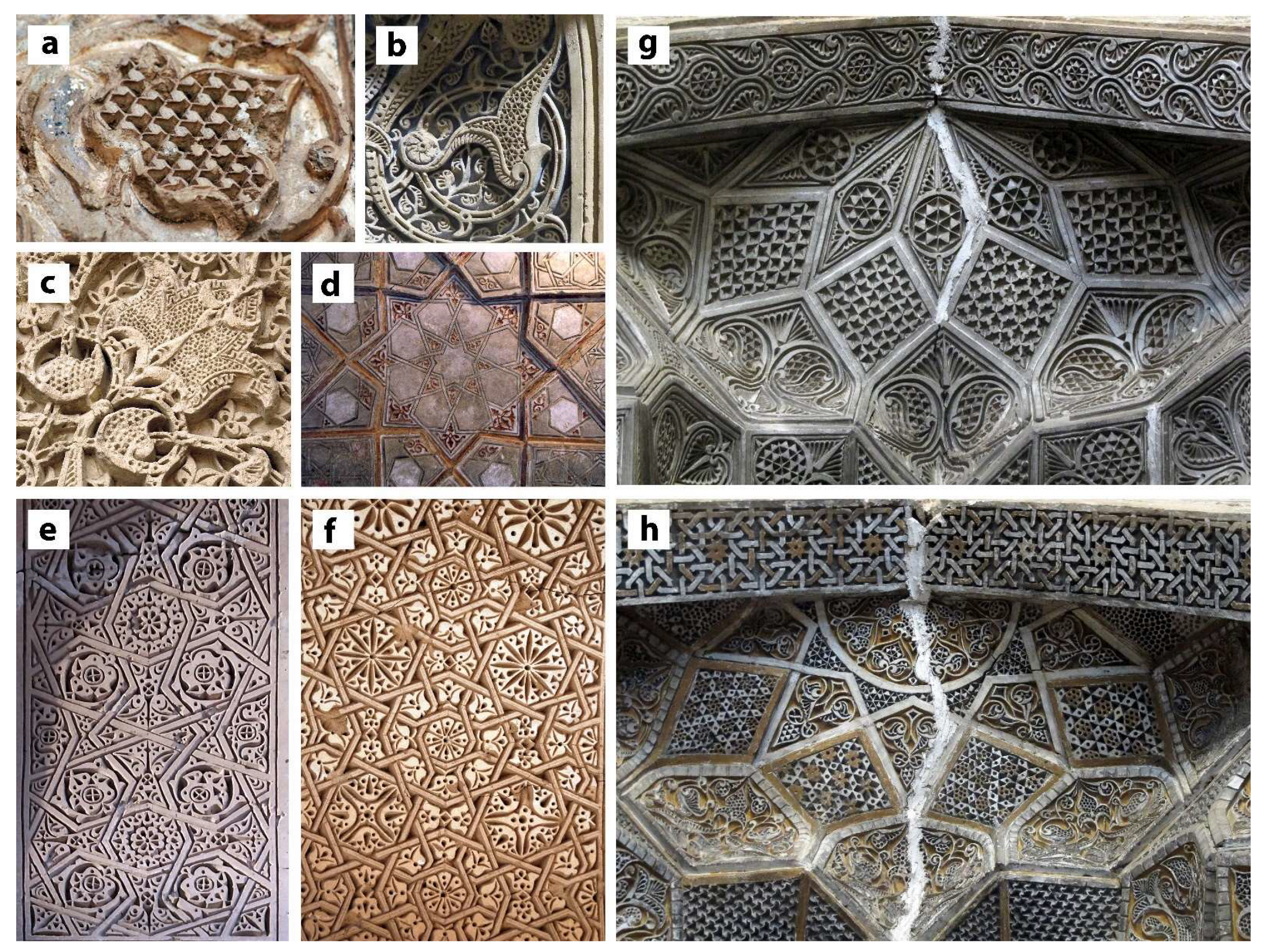

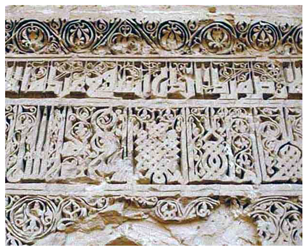

2.1. Main Features of Stucco Decorations Before the Ilkhanid

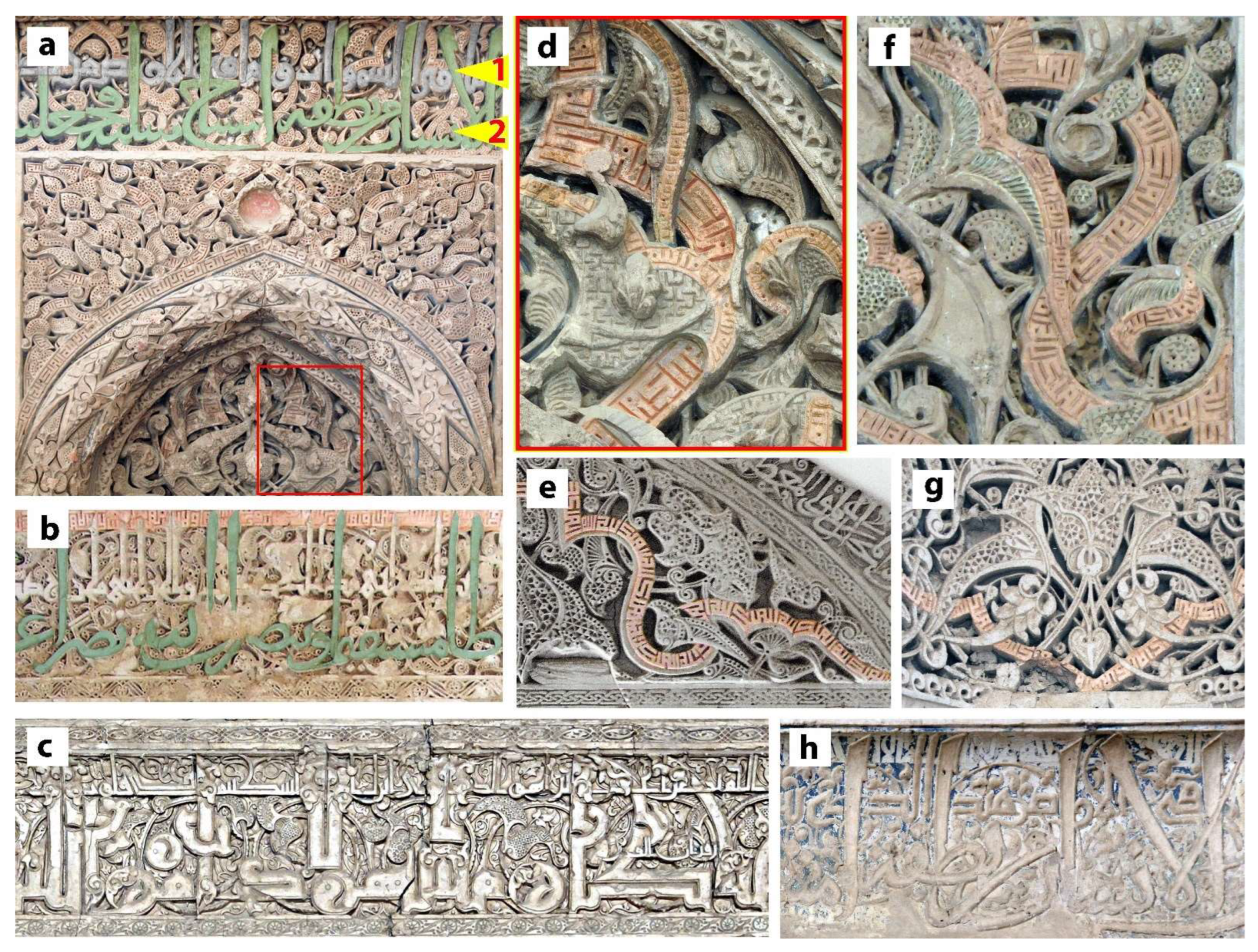

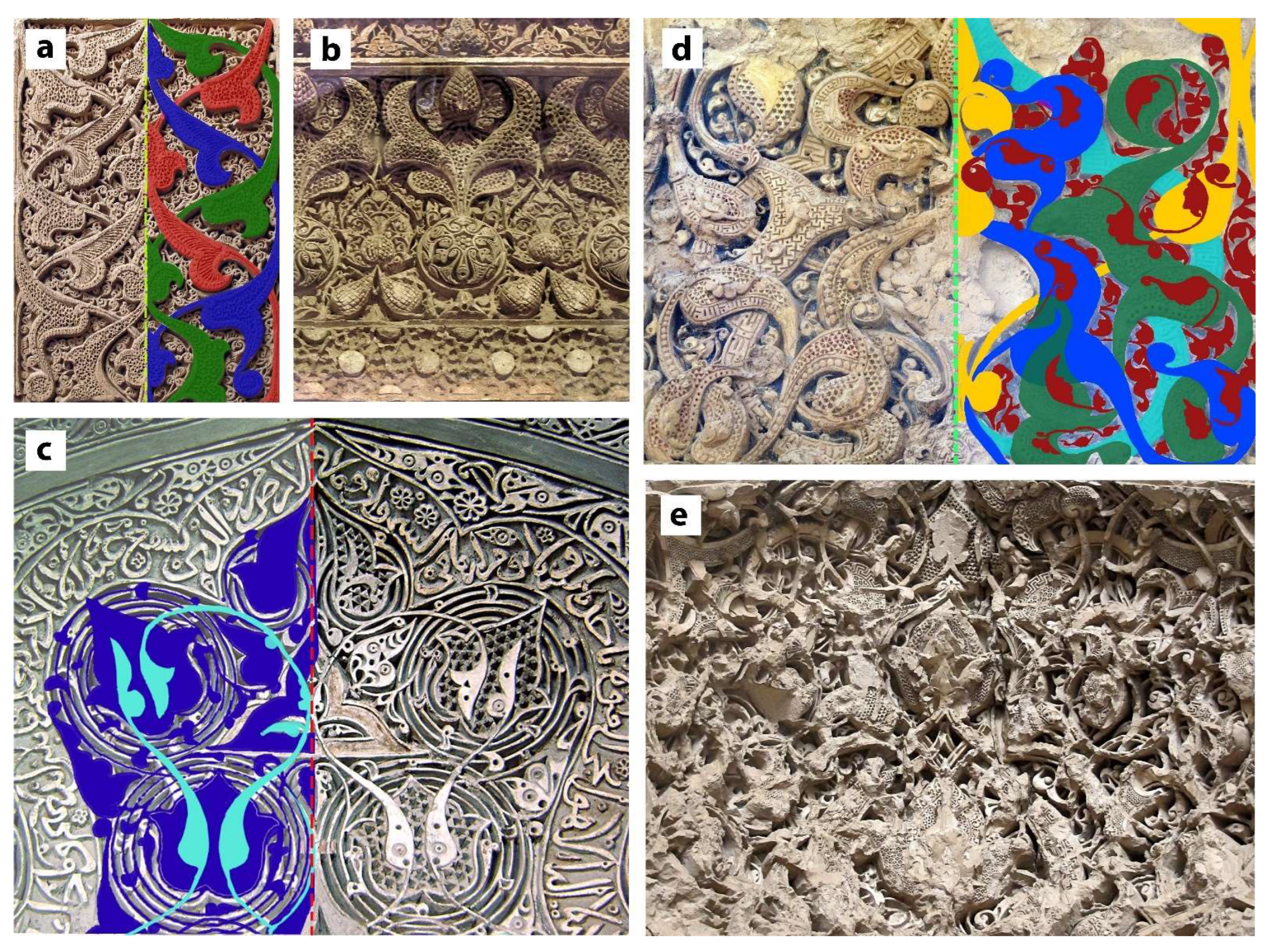

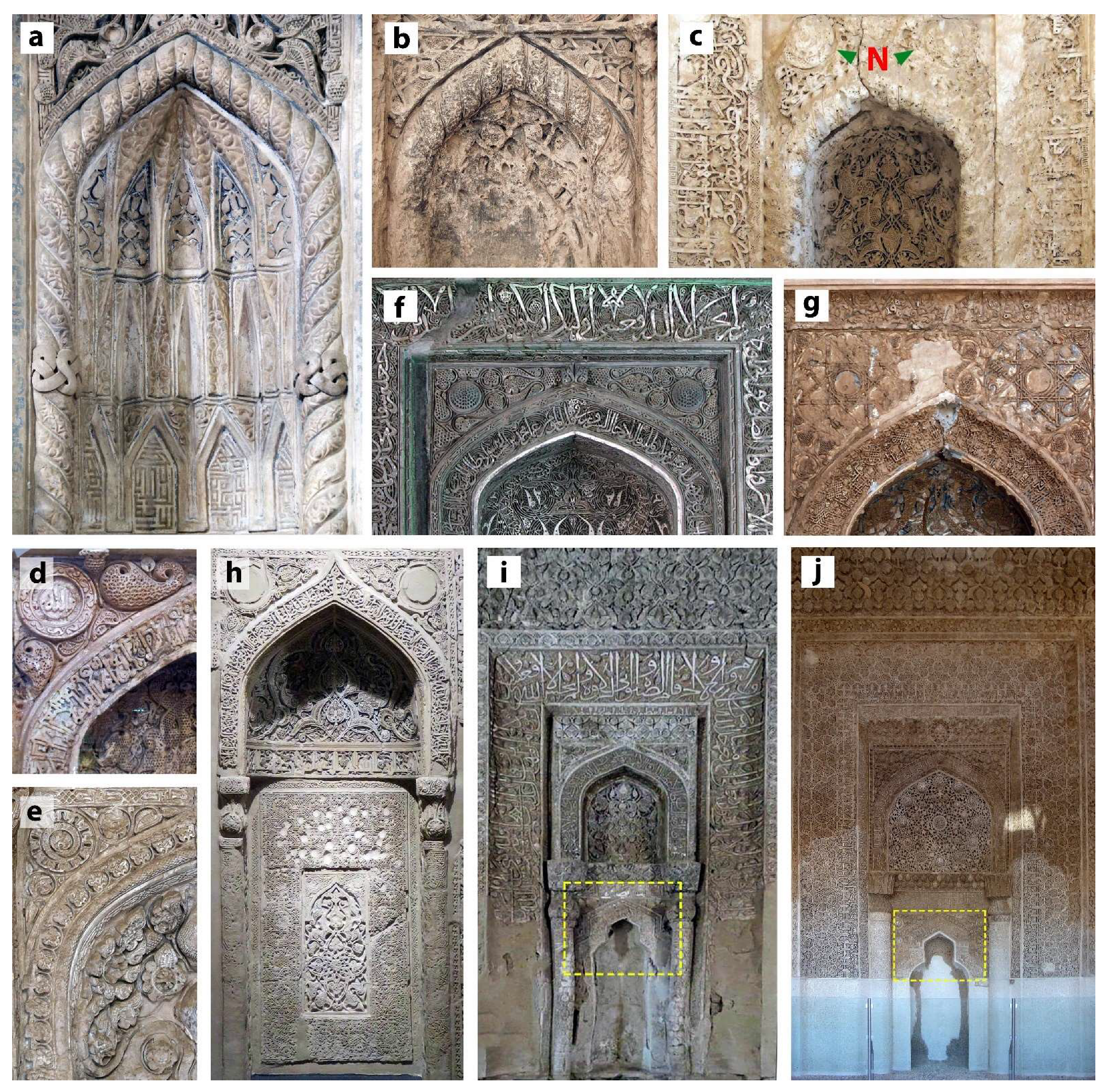

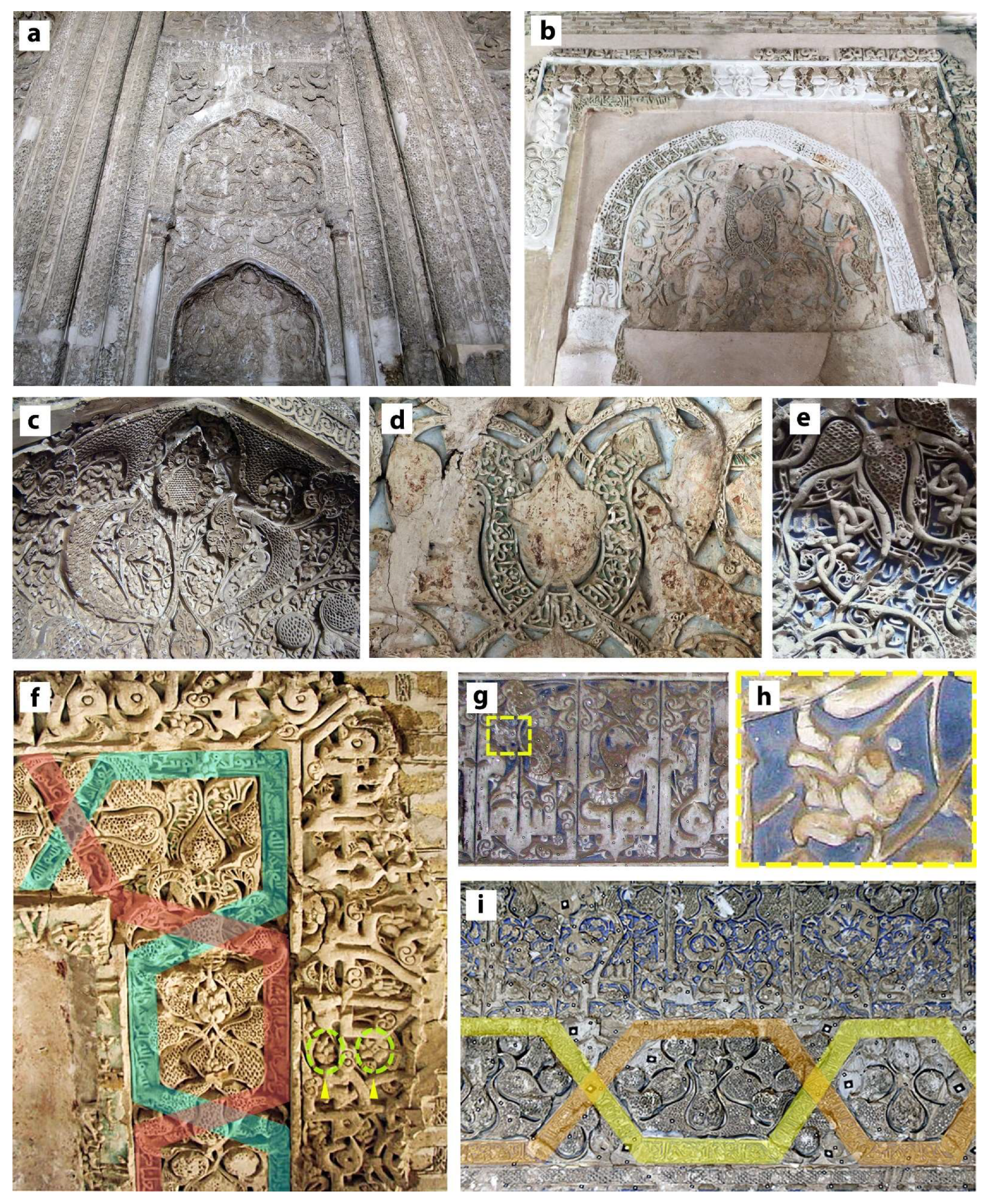

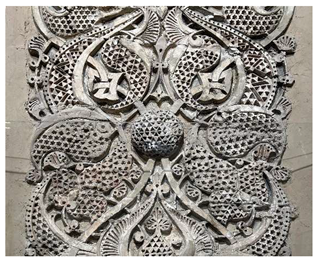

2.2. Stucco Decorations of the Ilkhanid

3. Methods

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Techniques of Ilkhanid Stucco Decorations

4.2. Design Elements and Compositions of Ilkhanid Stucco Decorations

4.3. Stylistic Features of Ilkhanid Stucco Decorations

- -

- Yek-gacha (low-relief) stucco cladding: Particularly presented in brick-like patterns, geometric compositions, and Bannāī inscriptions.

- -

- Seh-gacha (very high relief): A technique unique to the Ilkhanid period, appearing for the first time in select small-scale motifs.

- -

- Patta and Moshabbak: Two innovative methods of stucco decoration introduced during this period, albeit with limited application.

- -

- Gilding: A novel finishing technique, applied to stucco surfaces for the first time in Ilkhanid monuments.

- -

- Decorative combination of different materials: Sophisticated integration of stucco with brickwork and, most notably, with tile.

- -

- Geometric patterns: Employed extensively, both in simple Āazhede-kāri forms and in more complex compositions combined with Khatāʾī elements in a Shāh-gereh.

- -

- Inscriptions: Widespread use of diverse scripts—including knotted Kufic, Bannāī, thuluth, and Mosalsal—together with new composite arrangements such as Mādar-o Farzand.

- -

- Multilayered ornaments: Complex multilayered compositions, typically comprising an arabesque base layer, a second layer of floriated Khatāʾī, and a third layer of inscriptions (often a row of curved Bannāī); in some cases, there is a fourth layer of arabesque with isolated Khatāʾī motifs.

- -

- New architectural elements: Introduction of small twisted spiral columns flanking a niche of mihrab, as well as semi-columns decorated with geometric patterns, as in Rabiʿa Khātūn-i Oshtorjān.

- -

- Trefoil arches and muqarnas lunettes: Their earliest known appearance in stucco mihrabs belongs to this period.

- -

- Noqul decoration: Extensively applied to Ilkhanid mihrabs, typically rendered in reticulated patterns with polychrome enhancement.

- -

- Brick-like stucco cladding: Large wall surfaces—often more than fifty percent—were covered with gypsum in the form of brick-like patterns and Bannāī inscriptions, creating the effect of structural brickwork.

5. Two Case Studies Based on the Research Findings

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Two main techniques of stucco decoration have been identified through stylistic studies. During the early Nasrid period (1238–1314), stucco was carved in situ with chisels while the gypsum was still damp. The decorative programs of the Alhambra from this phase are comparatively simple and less labor-intensive. Later, a plaster-cast technique was introduced, in which stucco was molded in Plaster of Paris, clay, or wooden molds and subsequently affixed to the walls. By the late Nasrid period, working methods had become more systematized, with casts employed to produce increasingly complex decorative motifs [5]. This Arabic-derived style of stucco decoration in Andalusia was further disseminated by the Moors and became known as the mudéjar style, which flourished in Spain from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries [6]. |

| 2 | Dar-jā (درجا) in Persian |

| 3 | In Islamic thought, two key considerations are closely intertwined: (i) the rejection of images that might be perceived as idols—most notably representations of humans or animals, especially within mosques, where only very rare depictions of birds or quadrupeds are observed; (ii) the broader prohibition of figural representation of living beings. It should be noted, however, that this attitude was not universally or uniformly imposed. For instance, human figures appear somewhat more frequently in Shiʿi contexts than in Sunnite ones [13,14]. Moreover, Islamic principles also discouraged the use of excessive luxury in art, as it was seen as a violation of the sanctity of religious values [15,16]. |

| 4 | Some scholars argue that Byzantine and Islamic artistic borrowings from the Sasanians were part of a broader pattern of emulating Sasanian imperial practices, reflecting admiration for an empire that epitomized oriental luxury and political authority. In fact, it was primarily the late Sasanian stylistic features that disseminated into Islamic artistic realms [18,19,20]. |

| 5 | In miniaturistic compositions, a greater number of elements are required to fill similar spaces, making such works more labor-intensive and painstaking than their monumental counterparts. |

| 6 | Accession Number: 40.170.441, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/450114 (accessed on 1 November 2022). |

| 7 | Du-gacha (دو گچه) is a technique of using two gypsum layers to make high-relief decoration. |

| 8 | Movaraq Kufic (کوفی مورق): The bifurcation of letter endings, often forming half-palmettes, is one of the most striking features among the varieties of Kufic script. These varieties include primitive (simple) Kufic, foliated Kufic, floriated Kufic, plated or interlaced Kufic, knotted Kufic, bordered Kufic, Bannāī (angular Kufic), and Maʿqely Kufic (rectangular or square Kufic) [46,47]). |

| 9 | Āazhede-kāri (آژده کاری): Repetitive simple geometric shapes like a honeycomb. |

| 10 | Stamped joint plugs are observed on nearly all surfaces, from the lower layers of brick masonry up to the apex of the dome. In some areas, wider joints are filled with more elaborate motifs, such as knots or plaited bands, while the fundamental brick-bonding pattern remains dominant. In mihrabs, stucco ornamentation becomes more prominent and exhibits greater freedom, with tendrils and fleurons in relief filling the spaces between the letters of inscriptions [48]. Notably, the practice of filling spaces between the letters of brick inscriptions with stucco fleurons predates the Seljuq period, as seen in the Kufic band of the octagonal pavilion of Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ṣamad in Natanz, attributed to the Buyid era. |

| 11 | Khatāʾī (ختایی): Floral patterns added to the arabesque to create lavish designs. |

| 12 | Qaṭār-bandy (قطاربندی): A circuit frieze of inscription inside maqṣura (dome chamber). |

| 13 | Pishāny (پیشانی) is a decorative frame above the mihrab, directly beneath the roofline of the maqṣura, serving as both an ornamental feature and a transitional element between the vertical surface of the mihrab and the overhead architectural framework. |

| 14 | Gach-o-Khak (گچ و خاک) is a specific mixture of clay and gypsum to level the substrate before executing the decoration on the wall. |

| 15 | Gach-i Tiz (گچ تیز) is quick-setting gypsum. |

| 16 | Yek-gacha (یک گچه) is a technique using a single gypsum layer to make a low-relief decoration. |

| 17 | Gach-i Khoush-maya (گچ خوش مایه). |

| 18 | Seh-gacha (سه گچه) involves using three gypsum layers to make a very high-relief decoration. |

| 19 | Kaluk-band (کلوک بند) is a method to decorate the vertical distance between the bricks of a row. |

| 20 | Shebh-i Ājori (شبه آجری) is composed of the brick-like cladding of the wall, which is executed by gypsum. |

| 21 | Godard produced the first reports on the stucco decoration of Pir-i Ḥamze Sabzpūsh, which has been attributed to the sixth century AH [63]; Pope also noted the similarity of this mihrab to the stucco decoration of Gonbad-i ʿAlaviyān, Hamedan [23]. The mihrab’s inscription is damaged but partially legible, “فی المحرم… …ﻌین و خمسمائه”, with the probable date reading “تسعین و خمسمائه” (590 AH; 1194 CE). Scholarly consensus suggests that the decorations belong to two distinct periods: the sixth and eighth centuries AH [64]. According to these authors, the upper panel of the mihrab, which includes Moshabbak decoration, dates to the eighth century AH, as it is set apart from the margin of the mihrab and differs in both design and execution. The underlying white paint layer, associated with the first phase of decoration, is located beneath the mihrab near its cornice [64,65] |

| 22 | The earliest dated inscription of the mihrab is 363/974 (Deylamid period), although Godard considered the mosque to be of even earlier origin [66]. The mihrab appears to have undergone several phases of restoration and reconstruction, as evidenced by additional dates: 460/1068 (Seljuq), 560/1165 (Khwarazmian), and another now-destroyed inscription that is no longer legible. Surrounding the mihrab is also a thuluth inscription dated 946/1540. Beyond the mihrab itself, inscriptions elsewhere in the mosque attest to further interventions, particularly during the Safavid and Qajar periods. Despite this epigraphic evidence, the precise dating of each structural or decorative phase of the mihrab remains uncertain—especially the inner lunette, which features reticulated decoration. From a stylistic perspective, this reticulated element cannot be earlier than the Khwarazmian period, and in fact, its design bears closer affinity to Safavid ornament. |

| 23 | The dating of the mihrab of Yahya va Fażl-al-Reżā remains a matter of scholarly debate. An inscription at the base of the mihrab reads: “فی ایام امیرالمومنین رضی الله عنه سنة ثلثین”. Taken literally, this would correspond to 30 AH; however, such a date is implausible, since the use of the thuluth script had not yet been developed at that time. Some scholars suggest that the word “ثلثمائه” (three hundred) may have been partially destroyed in the inscription, which would instead yield a date of 330 AH [67]. By contrast, Wilber proposed a much later date of 708 AH [1]. Further evidence comes from the builder’s signature, “عمل حسن علی احمد بابویه”, inscribed on the mihrab. Scholars generally associate this name with the Babuya family, who are attested in contemporary architectural contexts, including the Shaykh ʿAbd al-Ṣamad Monastery (707/1308) and the luster mihrab now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (eighth/fourteenth century) [68]. On this basis, most experts assign the mihrab of Yahya va Fażl-al-Reżā to the eighth/fourteenth century [69]. |

| 24 | Noqul (نغول) is the name of a small, circular, projecting ornament on the mihrab in Persian. |

| 25 | Moʿaraq (معرق) consists of small pieces of polychrome tile carefully fitted together to form a figure or inscription, in a manner comparable to mosaic. |

| 26 | Including Iran, Egypt, North Africa, Spain (Al Andalus), Iraq, Syria, Palestine, the Indian Subcontinent, Turkey, Central Asia, and Anatolia. |

| 27 | Bannāī (بنایی) is a kind of angular Kufic script that has geometric letters like squares, rhombuses, rectangles, and parallel and crossed lines [47]. |

| 28 | |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Herzfeld has estimated the date of this building as being between 709 and 716 AH (1310–1317) [75]. In addition, Wilber estimated that the interior decoration was probably added in the next period, and its date is 715 AH (1316) due to the elegance, beauty, and prominence of the motifs, which are characteristic of the patriarchal beds [1]. |

| 31 | According to the style and inscriptions beside the lotus flowers on the mihrab of Sujās, it is attributed to the eighth AH century [76]. |

| 32 | The first phase is attributed to the Seljuq period, given the style of its building, and the second phase is attributed to the later thirteenth century [70]. |

| 33 | Tawqiʿ (توقیع) is one of the six Islamic calligraphies deriving from thuluth. Its shape and appearance are conclusive evidence that it is a derivative of thuluth [47]. |

| 34 | This lotus flower is a preliminary design of the Shāh Abbāsi flower, or “Goljam”, which is formed in Khatāʾī twirl [77]. |

References

- Wilber, D.N. The Architecture of Islamic Iran: The Ilkhanid Period; Greenwood press: Westport, CT, USA, 1955; pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sheila, B. The Mongol Capital of Sulṭāniyya, ‘The Imperial’. Iran 1986, 24, 139–151. [Google Scholar]

- Piran McClary, R. Three Ilkhanid Stucco Mihrabs in Central Iran: Work of a Distinctive Regional Workshop? In Stucco in the Islamic World, Studies of Architectural Ornament from Spain to India; Richard, P., Ed.; Edinburgh University Press: McClary, Scotland, 2025; Chapter 12; pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Grbanovic, A.M. The Ilkhanid Revetment Aesthetic in the Buqʿa Pir-i Bakran: Chaotic Exuberance or a Cunningly Planned Architectural Revetment Repertoire? Muqarnas Online 2017, 34, 43–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardell-Fernández, C.; Navarrete-Aguilera, C. Pigment and plasterwork analyses of Nasrid polychromed lacework stucco in the Alhambra (Granada, Spain). Stud. Conserv. 2006, 3, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattstein, M.; Delius, P. Islamic Art and Architecture; Tandem Verlag: Cologne, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio Domene, R. Yeserías De La Alhambra: Historia, Técnica y Conservación; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2010; pp. 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff, H.E. The Traditional Crafts of Persia; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Erich FSchmidt Persepolis, I. Structures, reliefs, inscriptions. J. Am. Orient. Soc. 1957, 77, 145–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, J.; Sasanian Stucco, A. Ornamental. In A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present; Pope, A.U., Ackerman, P.H., Eds.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 1938; pp. 601–630. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, P.O. Art in Iran, History of Sasanian. In Encyclopaedia Iranica; Yarshater, E., Ed.; Routledge & Kegan Paul: Oxfordshire, UK, 1986; Volume II, pp. 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- Kharazmi, M.; Afhami, R.; Tavoosi, M. A Study of Practical Geometry in Sassanid Stucco Ornament in Ancient Persia. Nexus Netw. J. 2012, 14, 227–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riefstahl, R.M. Persian Islamic Stucco Sculptures. Art Bull. 1931, 13, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabar, O. The Formation of Islamic Art; Revised and Enlarged Edition; Yale University Press: London, UK, 1987; pp. 136–149. [Google Scholar]

- Ismāʿīl, R. al-Fārūqī. “Islām and Art.” Stud. Islam. 1973, 37, 81–109. [Google Scholar]

- Soganci, I.O. Islamic aniconism: Making sense of a messy literature. Marilyn Zurmuehlen Work. Pap. Art Educ. 2004, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidemann, S.; de Lapérouse, J.F.; Parry, V. The Large Audience: Life-Sized Stucco Figures of Royal Princes from the Seljuq Period. Muqarnas 2014, 31, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, A.L. A Brief Note on Early Abbasid Stucco Decoration. Madinat al-Far and the First Friday Mosque of Isfahan. Muqarnas 2017, 25, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, C.A. Sasanian Stucco Influence: Sorrento and East-West. Orient. Lovan. Period. 1983, 14, 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, C.P. The Development of Stucco Decoration in Northern Syria of the 8th and 9th Centuries and the Bevelled Style of Samarra. Facts Artefacts 2007, 439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, H.; Shekofteh, A. The Stucco Decoration in Early Periods of Islamic Architecture in Iran (seventh to eleventh centuries AD). J. Lit. Relig. Art 2011, 4, 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Flury, S. Un monument des premiers siècles de l’Hégire en Perse: II. Le décor de la mosquée de Nâyin. Syria 1921, 2, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, A.U.; Ackerman, P. A Survey of Persian Art from Prehistoric Times to the Present; Soroush Press: Tehran, Iran, 1964; Volume 3, pp. 1264–1364. [Google Scholar]

- Shekofteh, A. Comparative Study on the Stucco Decorations of Two Monuments from the Greater Khorasan: Robat Sharaf and Faryoūmad Mosque (Seljuq, Khwarazmian, The Ilkhanid). Negareh J. 2019, 14, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Shekofteh, A. Study on the Evolution of Stucco Ornaments in Architecture of Iran, the First Part of the Encyclopedia of Iran Architecture’s Decorations; Research Institute of Cultural Heritage & Tourism: Tehran, Iran, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aghajani, I.; Korn, L. Stucco of the Seljuq Period in Iran, with a Focus on Dado Zones and Mihrabs. In Stucco in the Islamic World: Studies of Architectural Ornament from Spain to India; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2025; pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Taqavinejad, B. The Comparative Study of Geometric Ornaments of Plaster Mihrabs Created during Seljuk Period versus the Ones Created during Ilkhanid Period in Iran. Maremat Me’mari-E Iran 2019, 9, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Grube, E.J. Studies in the Decorative Arts of the Muslim World; Pindar Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- O’kane, B. Studies in Persian Art and Architecture; Amer University in Cairo Press: Cairo, Egypt, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, A.U. The Historic Significance of Stucco Decoration in Persian Architecture. Art Bull. 1934, 16, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’kane, B. Naṭanz and Turbat-i Jām. Stud. Iran. 1992, 21, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.E.; Mortazaei, M.; Behboodi, N.; Thani, L. An Analytical view on the Stucco Decorations of the Ilkhanid Religious Buildings: A Case Study of Pir-i Bakran Isfahan, Iran. Iran. J. Archaeol. Stud. 2012, 2, 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Shekofte, A. The Most Significant Visual Characteristic in Stucco Decorations, Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran. J. Iran. Archit. Stud. 2013, 1, 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shekofte, A.; Salehi Kakhki, A. Techniques and changes of stucco decorations in Iranian architecture from 7th to 9th century Hijry Qamari. Negareh 2014, 9, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Alvandiyan Khakbaz, E. Identification of the unique stucco technique of the Ilkhanid tomb. Seyyed Rokn Al din Yazd. Master’s Thesis, Department of Conservation, Art University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran, 2005, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Taqavinejad, B. Typology of the Form and the Role of the Frames Covered in the Stucco Decorations Made during 8th Century in Iran. Maremat Me’mari-E Iran 2020, 10, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi Kakhki, A.; Aslani, H. Presentation of 12 types of stucco works used in the architectural decoration of the Islamic period in Iran based on technical properties. J. Archaeol. Stud. 2011, 3, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Aslani, H. Technical Studies of Stucco Decoration on the Islamic Era. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Conservation, Art University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran, 2012, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzavi, Y.; Aslani, H. Arayiha-Yi Miʿmari-yi Buqʿa-yi Pir-I Bakran; Goldasteh: Isfahan, Iran, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, B. The Allover Pattern in Mesopotamian Stuccowork. Berytus Archaeol. Stud. 1952, 10, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. Stucco from Chal Tarkhan-Eshqabad near Rayy; Aris & Phillips Ltd.: Warminster, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Keall, E.J. Qalʿeh-i Yazdigird: A Sasanian Palace Stronghold in Persian Kurdistan. Iran 1967, 5, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keall, E.J.; Leveque, M.A.; Willson, N. Qal’eh-i Yazdigird: Its Architectural Decorations. Iran 1980, 18, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, R. On the Stylistic Idiosyncrasies of a Saljūq, Stucco Workshop from the Region of Kāshān. Iran 1989, 27, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhtiar, M.; Soucek, P.; Canby, S.R.; Haidar, N.N. Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2011; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann, A. The Origin and Early Development of Floriated Kūfic. Ars Orient. 1957, 2, 183–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fazaeli, H. Aṭlas-i khat; Calligraphy Atlas; Enteshārāt-i Mash’al: Isfahan, Iran, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, L. Architecture and Ornament in the Great Mosque of Golpāyegān (Iran). Beiträge Zur Islam. Kunst Und Archäologie 2012, 3, 212–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekofteh, A.; Ahmadi, H.; Oudbashi, O. Architectural Decorations from Seljuq Period in Iran and Their Impact on the Maintenance of Culture in Further Historical Periods; Research Report; Centre of Traditional Arts of Islam, the Institute of Culture, Art and Communication: Isfahan, Iran, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shekofteh, A.; Ahmadi, H.; Oudbashi, O. Seljuk Brickwork Decorations and Their Sustainability in Khwarezmid and Ilkhanid Decorations. Univ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 3, 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, L. Iranian Style ‘Out of Place’? Some Egyptian and Syrian Stucco of the 5–6th/11–12th Centuries. Ann. Islam. 2003, 37, 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Taqavinejad, B. The study of the plant and geometric decorations of the stucco mihrabs of the tomb of Torbat-e Sheikh-e Jam. Negarineh Islam. Art 2017, 4, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Taqavinejad, B. Introducing and Reviewing the Decorative Features of the Mihrab of the Great Mosque of Saveh in Arak Chaharfasl Museum. Negarineh Islam. Art 2018, 5, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi-Kakhki, A.; Taqavinejad, B. Introduction and Typology of Geometric Decorations in the Architectural Ornaments of the Dome of Sultaniyya. JIAS 2020, 9, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Taqavinejad, B.; Mirsalehian, S. Geometric decorations in the architectural of Varamin Mosque. Rahpooye-E Honar 2022, 5, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi Kakhki, A.; Taqavinejad, B. The typology of plant compositions in the Iranian stucco decoration from the Islamic period to the end of the eighth century AH. J. Res. Islam. Archit. 2019, 6, 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mishmastnehi, M.; Van Driessche, A.E.; Smales, G.J.; Moya, A.; Stawski, T.M. Advanced materials engineering in historical gypsum plaster formulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2208836120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motififard, M.; Fotohi, P. Plastering: Reviving Forgotten Arts; Naqsh-e Mana: Tehran, Iran, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Degeorge, G.; Porter, Y. The Art of the Islamic Tile; Flammarion: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Heydari, F. Technological Study of a Type of Stucco Decorations Under the Soltaniyeh Dome. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Restoration and Conservation, Art University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran, 2012, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla, M. Pre-fabricated Stucco Decorations in Sultaniyya. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Stucco Decoration in the Architecture of Iran and Neighbouring Lands, Bamberg, Germany, 4–7 May 2022; “Bamberg” University: Bamberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Isfahani-pour Hanzaei, F. Technological Study, Condition Assessment, and a Conservation Plan for Stucco Decorations in Shamsiyeh School, Yazd. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Conservation and Restoration, Art University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Godard, A.; Godard, Y.; Siroux, M. Aṯhār-e-Irān; trans. Abul Hasan Sarv-qad Moqadam; Astan-e-quds-Razavi publication: Mashhad, Iran, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Karimy, A.H.; Holakooei, P. Analytical studies leading to the identification of the pigments used in the Pīr-i Hamza Sabzpūsh Tomb in Abarqū, Iran: A reappraisal. Period. Di Mineral. 84 2015, 3A, 389–405. [Google Scholar]

- Fadawi, S.M.; Zareʿ, H. Pīr-i Hamza Sabzpūsh. Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba Honar-Ha-Ye Tajassomi 20 2015, 1, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zakeri, M.H.; Memarian, G.H. Jamaʿ Mosque of Neyriz. Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba 2006, 24, 67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Feiz-e Qomi, A. Ganjine Athar-i Qom; Mihr Ostovar: Qom, Iran, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, R. Salǧūq Monuments in Iran: I. Orientral Art 1972, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, S. A Medieval Persian Builder. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 45 1986, 4, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taqavinejad, B. The Ornaments of Ilkhanid Stucco Mihrabs of Iran Stylistic Characteristics on the Basis of Composition and Motifs. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Conservation and Restoration, Art University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran, 2017, unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullahi, Y.; Rashid Bin Embi, M. Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns. Front. Archit. Res. 2013, 2, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillenbrand, R. Salǧūq Monuments in Iran. V. The Imāmzāda Nūr, Gurgān. Iran 1987, 25, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekofteh, A. The Content of Quranic Inscriptions Used in Ilkhanid Altars. JRIA 2015, 3, 104–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hatam, Q.A. Islamic architecture of Iran in the Seljuq period; Jahad-i dāneshgāhi Publications: Tehran, Iran, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Herzfeld, E. Die Gumbadh-i ʿAlawiyyan und die Baukunst der Ilkhāne in Iran. In A Volume of Oriental Studies Presented to Edward G. Browne, on His 60th Birthday (7 February 1922); Arnold, T.W., Nicholson, R.A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1922; pp. 186–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, R. Salǧūq Monuments in Iran: III: The Domed Masǧid–I Ǧāmiʿ At Suǧās. Kunst Des Orients 10 1975, 1/2, 49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kühnel, E. Arabesque and Khatāī, Shāh Abbās Flowers: A View on the Historical Background of Three Decorative Paintings; trans. Shahryar Maleki, Hadi Aqdasiye and Hossein Taherzade-Behzad (in Persian). Yasavouli: Tehran, Iran, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi-Kakhki, A.; Taqavinejad, B. The Study of Genealogy and Individual Styles of Plaster Workers Of the 14th Century. JRIA 2017, 5, 84–104. [Google Scholar]

- Grbanović, A.M. Ilkhanid Stucco Revetments in Iran, C. 1256–1335: Function, Meaning, and Aesthetic Principles. Ph.D. Thesis, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg, Bamberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Period | Main Techniques | Design Characteristics | Representative Image | Distinctive Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sasanid (3rd–7th c.) |

|

|  Stucco fragment from Tepe Hissar, NMI |

|

| Early Islamic (7th–11th c.) |

|

|  Stucco decoration from Naʿin Mosque |

|

| Seljuq (11th–12th c.) & Khwarazmian (11th–13th.c) |

|

|  Stucco decoration from Robat Sharaf |

|

| Ilkhanid (13th–14th c.) |

|

|  Stucco decoration from Torbat-i Jam, NMI Stucco decoration from Torbat-i Jam, NMI |

|

| Muzafarid & Tymurid (14th–16th c.) |

|

|  Decoration from Shams al-Din Mausoleum Decoration from Shams al-Din Mausoleum |

|

| Name | Location (Province) | Date C.E./AH. | Location of the Stucco Decorations (W: Width, H: Height) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Urmia Jamaʿ Mosque | West Azerbaijan | 1276/676 | Mihrab (5.50 m W, 7.82 m H) |

| 2 | Tabriz Jamaʿ Mosque | East Azerbaijan | 13th c. | Mihrab (≈5 m W, 8 m H) |

| 3 | Marand Jamaʿ Mosque | East Azerbaijan | 1330/731 | Mihrab (2.75 m W, 6 m H) |

| 4 | Sāveh Jamaʿ Mosque | Markazi | 13th c. | Mihrab (2.60 m W, 3.50 m H), walls |

| 5 | Shāhzādeh Kudzar | Markazi | 14th c. | Mihrab (≈3 m W, 4 m H), walls |

| 6 | Yahya va Fażl-al-Reżā | Markazi | 14th c.? | Mihrab (2 m W, 2.70 m H) |

| 7 | Haft Shūya Mosque | Isfahan | 13th–14th c. | Mihrab (3.30 m W, 6.20 m H), walls |

| 8 | Koche-i Mir Mosque | Isfahan | 14th c. | Mihrab (1.65 m W, 2.85 m H) |

| 9 | Natanz Jamaʿ Mosque | Isfahan | 1304-07/704-09 | Arch inscription |

| 10 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Isfahan | Isfahan | 1310/710 | Oljaytu Mihrab (3.30 m W, 5.60 m H) |

| 11 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Kāshān | Isfahan | 14th c. | Mihrab (≈4 m W, 7 m H) |

| 12 | Pir-i Bakrān Mausoleum | Isfahan | 1303-12/703-12 | Mihrab (3.70 m W, 6.50 m H), walls |

| 13 | Fār Fān Mosque | Isfahan | 14th c. | Mihrab (3.30 m W, 3.80 m H) |

| 14 | Shāh Karam | Isfahan | 1339/740 | Mihrab (2 m W, 3.50 m H) |

| 15 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Oshtorjān | Isfahan | 1315/715 | Mihrab (≈3 m W, 7 m H), walls |

| 16 | Rabiʿa Khātūn-i Oshtorjān | Isfahan (moved to National Museum of Iran) | 1308/708 | Mihrab (2.60 m W, 4.15 m H) |

| 17 | Imamzadeh Yahya-i Varāmīn | Tehran | 1307/707 | Walls |

| 18 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Varāmīn | Tehran | 1322-26/722-26 | Mihrab (3.90 m W, 8 m H), walls, inscription |

| 19 | Solṭāniyya Dome | Zanjan | 1305-17/705-16 | Walls, dome |

| 20 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Faryoūmad | Semnan (Great Khorasan) | 13th–14th c. | The main mihrab (3 m W, 5 m H), walls |

| 21 | Bayazid-i Basțāmi complex | Semnan (Great Khorasan) | 1262-1314/660-713 | Mihrab of the second mosque (3.30 m W, 3.90 m W), walls, inscription |

| 22 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Basțām | Semnan (Great Khorasan) | 1303-07/702-06 | Mihrab (2.70 m W, 4 m H), walls |

| 23 | Tomb of Abu al-Hassan Karaqāni | Semnan (Great Khorasan) | 8th c.? | Mihrab (1.90 m W, 3.30 m H) |

| 24 | Shaykh-i Jām Complex | Khorasan-e Rażavi | 1312-28/712-28 | Kermānī mihrab (3.30 m W, 5.60 m H), walls, inscription |

| 25 | Mir-i Zobeyr | Kerman | 1350/751 | Mihrab (3 m W, 3.80 m H), walls |

| 26 | Jamaʿ mosque of Neyriz | Fars | 8th c. | Mihrab (4 m W, 4.90 m H) |

| 27 | Imamzadeh Khwāja Ali ibn-i Jaʿfar | Qom | 1339/740 | Walls, ceiling |

| 28 | Imamzadeh Seyed-i Sarbakhsh | Qom | 1343/744 | Walls, ceiling |

| 29 | Jamaʿ Mosque of Abarqū | Yazd | 1338/738 | Mihrab (4.50 m W, 5.40 m H) |

| 30 | Pir-i Ḥamze Sabzpūsh | Yazd | 14th c.? | Mihrab (≈2 m W, 3.50 m H) |

| Techniques | Codes of the Monument in Table 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

| Du-gacha | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● |

| Seh-gacha | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● |

| Patta | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Moshabbak | ● | — | — | ● | — | ● | ● | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | ● | ● |

| Gilding | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Material combination (stucco and tile) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | — | ● | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Monuments | Basic Formation of Grid | Location in the Monuments |

|---|---|---|

| Urmia Jamaʿ Mosque | 8-point | Lunette |

| Sāveh Jamaʿ Mosque | 6-point | Lunette |

| Imamzadeh Shāhzādeh Kudzar | 8-point | Side wall |

| Yahya va Fażl-al-Reżā | 4-point, 6-point | Lunette–margin–semi columns |

| Koch-i Mir Mosque—Natanz | 4-point | Mihrab |

| Pir-i Bakrān Mausoleum | 5-point, 6-point | Mihrab |

| Fār Fān Mosque | 6-point | Mihrab |

| Shāh Karam | 6-point, 8-point | Lunette–side walls |

| Jamaʿ Mosque of Oshtorjān | 4-point, 10-point, 12-point | Side walls |

| Rabiʿa Khātūn-i Oshtorjān | 5-point, 8-point, 12-point | Mihrab |

| Imamzadeh Yahya-i Varāmīn | 6-point, 8-point, 10-point, 12-point | Walls |

| Jamaʿ Mosque of Varāmīn | 4-point, 6-point, 8-point | Side walls |

| Solṭāniyya Dome | 6-point, 8-point, 10-point, 12-point | Walls–ceiling |

| Jamaʿ Mosque of Faryoūmad | 4-point, 6-point, 8-point, 12-point | Mihrab–side walls–muqarnas |

| Bayazid-i Basțāmi Complex | 4-point, 6-point, 8-point | Lunette–margin–semi columns |

| Jamaʿ Mosque of Basțam | 6-point, 8-point | Mihrab |

| Shaykh-i Jām Complex | 6-point | Side wall |

| Mir-i Zobeyr | 8-point | Lunette |

| Imamzadeh Ḵhaje Ali ibn-i Jaʿfar | 6-point | Lunette, ceiling |

| Imamzadeh Seyed-i Sarbakhsh | 6-point | Side wall, lunette, ceiling |

| Jamaʿ Mosque of Abarqū | 5-point, 8-point | Lunette and side wall of mihrab |

| Pir-i Ḥamze Sabzpūsh | 8-point | Side wall |

| Features | Codes of the Monument in Table 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

| Geometric pattern | ● | — | — | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Diverse inscriptions | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● |

| Mādar-o Farzand | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | ● | — |

| Bannāī | — | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | — | ● | ● | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | ● | ● | — |

| Brick-like cladding | — | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | ● | ● | — | — |

| Sophisticated patterns | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● |

| Superimposed layers | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Overlapping elements of Khatāʾī and Bannāī | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | — | ● | — | ● | ||

| Twisted spiral columns | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | ● | — |

| Muqarnas lunettes | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Trefoil lunette | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Noqul | — | — | — | ● | — | ● | — | ● | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ● | — | — | — | ● | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | — | ● | ● | ● | — |

| Ilkhanid Idiosyncrasies | Gonbad-i ʿAlaviyān | Sujās Jamaʿ Mosque | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | |||

| Yek-gacha | Brick-like patterns | ● | ● |

| Geometric compositions | ● | — | |

| Bannāī inscription | — | — | |

| Du--gacha | ● | ● | |

| Seh-gacha | ● | — | |

| Novel techniques (Patta/Moshabbak/gilding) | — | — | |

| Decorative combination of different materials | ● | ● | |

| Brick-like stucco cladding | ● | ● | |

| Design | |||

| Extensive coverage of surfaces with stucco | ● | — | |

| Diverse style of inscriptions (knotted Kufic and thuluth/Mosalsal/Mādar-o Farzand) | ● | ● | |

| Multilayered compositions (arabesques + Khatāʾī + inscriptions) | ● | — | |

| Specific elements (Noqul, twisted spiral columns, trefoil arches, muqarnas) | — | — | |

| Two-level mihrab including two lunettes (great vertical extent) | ● | — | |

| Pishāny and Qaṭār-bandy | ● | — | |

| Geometric bases (6-point and 8-point) | ● | — | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shekofteh, A. Techniques and Stylistic Characteristics of Stucco Decorations in Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran. Heritage 2025, 8, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110443

Shekofteh A. Techniques and Stylistic Characteristics of Stucco Decorations in Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran. Heritage. 2025; 8(11):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110443

Chicago/Turabian StyleShekofteh, Atefeh. 2025. "Techniques and Stylistic Characteristics of Stucco Decorations in Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran" Heritage 8, no. 11: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110443

APA StyleShekofteh, A. (2025). Techniques and Stylistic Characteristics of Stucco Decorations in Ilkhanid Architecture of Iran. Heritage, 8(11), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8110443