Abstract

This article examines the first Spanish American lacquerwares produced by Indigenous artisans in the seventeenth century, barniz de Pasto in Colombia and Peribán lacquer in Mexico, and discusses how the evolution of the decorative motifs, techniques, and forms of these lacquerwares can establish an initial dating chronology. Over the last thirty years, a sufficient number of examples of seventeenth-century Spanish American lacquerware have come to light that are datable, whether through provenance, historical references, or radiocarbon dating, and that make possible tentative chronologies for their production. The Hispanic Society of America in New York City holds at present the most significant collection of datable pieces of barniz de Pasto and Peribán lacquerware that now provide the key dates that can serve as the basis for establishing dating chronologies.

1. Introduction

In the early decades of the seventeenth century, the limited supply and strong demand for the highly prized Asian lacquerware introduced to the Americas and Europe by the Manila Galleons from the Philippines prompted the emergence of two new Spanish American lacquer traditions based upon the ancient Indigenous lacquer traditions of Mesoamerican and Andean civilizations. Indigenous artisans of the modern regions of the department of Putumayo in southern Colombia and the state of Michoacán in Mexico invented the new Spanish American lacquerwares of barniz de Pasto produced at Pasto, department of Nariño, Colombia, and at Peribán, state of Michoacán, Mexico. Spanish American barniz de Pasto lacquerware uses as its medium mopa mopa resin, harvested from the leaf buds of the mopa mopa tree (Elaeagia pastoensis L. E. Mora), found in the tropical rain forests of the mountains of southwest Colombia near Mocoa, the capital of the Department of Putumayo. Peribán lacquerware employed as its principal medium a mixture of aje fat obtained from the females of a scale insect (Llaveia axin), cultivated by the Purépecha People of Michoacán for centuries on acacias, piñon pines, and hog plum trees, combined with chía oil extracteded from the seeds of a native sage plant (Salvia chian), which the Aztecs and the Purépecha Peoples had cultivated not just for the oil but as a food crop. The materials and techniques used in producing barniz de Pasto and Peribán lacquerware were first generally described in a number of publications, which brought these objects to the attention of a broader public [1,2,3,4]. Since 2000, a monograph [5] as well as a number of technical studies have been published mainly on viceregal barniz de Pasto objects, for example, identifying the source of the mopa mopa resin [6] and identifying many of the colorants used [7,8]. A technical study on Mexican lacquer was published in 2012 [9].

Seventeenth-century barniz de Pasto and Peribán lacquerwares were largely unknown until the end of the twentieth century, even in their countries of origin, with the exception of a few art historians, museum professionals, and collectors. No examples of matte barniz de Pasto were to be found in public institutions in Colombia, and the same can be said of Peribán lacquerware in Mexico up to the present. When the Hispanic Society began to collect Spanish American viceregal decorative arts in the 1990s, the only resources with images of examples of seventeenth-century lacquerware were publications that could only be found in a few institutional libraries, and fortunately, most of those publications were held by the Hispanic Society. The first important published examples of Peribán lacquerware were two bufetillos (table cabinets) and a batea (tray), all in convents in Spain, that appeared in México en el mundo de las colecciones de arte, Nueva España I (Mexico, 1994) [10]. This publication served as my primary reference when the Hispanic Society acquired an important Peribán batea in 1998 (LS1808) and then another in 1999 (LS1978). Before the Hispanic Society acquired its first piece of seventeenth-century barniz de Pasto in 2001, the only other pieces that I had seen in person or in a publication were an eighteenth-century azafate (tray) from the Museo Jacinto Jijón y Caamaño, Quito, Ecuador, included in the 1992 exhibition at the Americas Society in New York, Barroco de la Nueva Granada: Colonial Art from Colombia and Ecuador [11]; and a small seventeenth-century casket and a fine eighteenth-century chest from the collection of Rodrigo Rivero Lake, which were published in his 1997 book La visión de un anticuario [12]. The present article seeks to illustrate the evolution of these lacquerwares and to suggest dating methods based on the visual examination of the decorative motifs and the stylistic qualities of the objects. A Spanish translation of this article is available in Supplementary Materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Barniz de Pasto, Mopa Mopa Lacquer, or Pasto Varnish: Historical Context

The earliest Spanish references to the use of mopa mopa for decorating objects are associated with the village of Timaná, situated over 170 km northeast of Pasto. In 1582, the Augustinian friar Jerónimo de Escobar noted in his description of the province of Popayán that the Indigenous Peoples of Timaná made long staffs painted with a varnish in bright colors but did not clearly identify the varnish as mopa mopa [13]. The Franciscan chronicler Pedro Simón (1581–ca. 1628), writing around 1626, observed that the inhabitants of Timaná, as well as Mocoa, Quito, and other parts of Peru, produced staffs and tobacco boxes that were decorated with a resin of various colors that was obtained from the leaf buds of a tree in the region:

In this land, certain trees sprout a small ball of resin like a gum, that if not collected, opens in a few days and changes into a leaf. The Indians pick these balls, and making the resin in various colors, they varnish staffs, tobacco containers, flag poles, poles for canopies, and other things made of wood, because on clay or any other thing it does not stick well. They also do this type of work in Mocoa, Quito, and other parts of Peru [14].

During the Spanish American period, the Indigenous Peoples of the Sibundoy Valley (approximately 35 km east of Pasto) supplied the resin-covered leaf buds, pressed into blocks, to the lacquer artisans, who processed and colored the resin for application on a variety of decorative, primarily wood, objects in Pasto. The earliest reference to the production of lacquer objects in Pasto dates from around 1676, yet by this time, barniz de Pasto had already enjoyed considerable fame in Europe, according to the Colombian bishop Luca Fernández de Piedrahita (1624–1688) [15]. The Pasto historian José Rafael Sañudo, using manuscript sources not cited, in 1897 provided the name of the earliest known barnizador in a rambling history of Pasto in the seventeenth century: “It is in this century that for the first time we have been able to know the name of an artist of varnish painting, a private industry of the city, who was Sébastián de Trejo” [16]. In the second edition of his history, published in 1939, Sañudo clarified the year as 1692 and added two more names: “pintores de Barniz”, Sebastián Sapillos, and the “indio pastuso” don Marcos Bastides [17].

2.2. Barniz de Pasto: Techniques, Stylistic Influences, and Dating Methods

From its beginnings in the first quarter of the seventeenth century, the special properties of mopa mopa resin allowed the barnizadores of Pasto to produce intricate and highly complex designs with both matte and transparent (brillante) barniz. To achieve the luminous metallic luster of the barniz brillante, lacquer artisans placed silver leaf underneath the highly refined transparent lacquer, creating an effect similar to Asian lacquers that incorporated gold and silver powder or leaf. This required stretching mopa mopa resin, natural or colored, into sheets as thin as onion skin. The varied shapes of the design were cut from the center of the sheet, where it was the thinnest, and laminated over the silver leaf. These pieces functioned as independent elements within the overall design or were stacked in multiple layers to create designs in relief. Additional fine details, such as circles, squares, or diamonds, in different transparent or matte colors, were also applied over larger pieces to create more elaborate patterns. In some of the most complex early techniques, minute threads of black or white mopa mopa were used to outline figures, to add fine details, or as cross-hatching for shading effects. All of these techniques are found on a very early casket in the collection of The Hispanic Society of America (Figure 1 and Figure 2 LS2067 unicorn), which dates it to ca. 16251. As can be seen in a detail of the unicorn in Figure 2, the body of the unicorn, which was once a luminous silver, is now a dull gray due to air having penetrated below the barniz over time, causing the silver leaf to oxidize.

Figure 1.

Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. Barniz de Pasto on wood, with silver fittings, 19.2 cm × 27.2 cm × 13.7 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2067.

Figure 2.

Detail of a unicorn. Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2067.

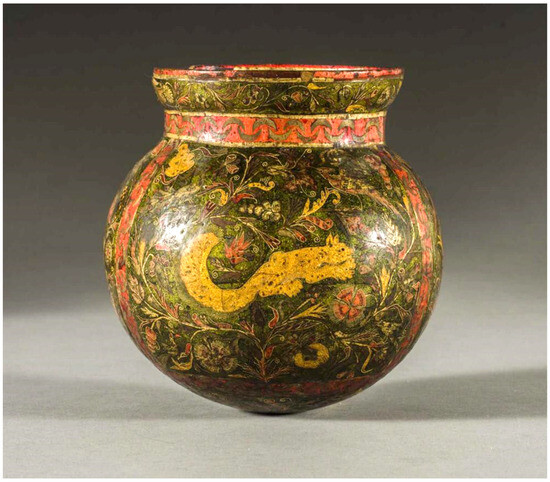

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, barniz de Pasto was used by Indigenous artisans to decorate the surfaces of secular and religious wooden objects, ranging from fall-front table cabinets to coffers, chests, caskets, trays, bowls, plates, book stands, picture frames, nesting beakers, as well as calabash gourd (totuma) drinking cups and vases (Figure 3). In the first half of the seventeenth century these luxury objects were made in Pasto for the cultural elite of the Spanish market under the supervision and instruction of Catholic missionary orders. They were primarily sent to Europe as gifts for high church officials, nobles, or monarchs or returned to Europe with their owners.

Figure 3.

Vase, Pasto, Colombia, before 1644. Barniz de Pasto on a calabash gourd (totuma), H 12 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2400.

Gourd vases are among the rarest survivors, made from the totuma (calabash), obtained from two possible species, Lagenaria siceraria or Crescentia cujete, both cultivated by the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas for millennia. This gourd vase2 in the collection of The Hispanic Society of America is one of the earliest datable pieces of viceregal barniz de Pasto, based on recent radiocarbon dating that yielded a terminus date of 1644 [7].

Early seventeenth-century examples of barniz de Pasto, whether matte or brillante, incorporate floral, foliate, and hunting motifs that include dogs, horses, deer, rabbits, foxes, wild boars, and lions, along with legendary beasts such as snailpersons, snailbirds, and snailunicorns, as well as creatures from Greco–Roman mythology, including unicorns, winged horses (Pegasus), double-headed eagles, mermaids, satyrs, sirens, and griffins. The earliest example of barniz brillante in the collection of The Hispanic Society of America (Figure 1), and perhaps the earliest extant example, is the ca. 1625 casket (LS2067). The complexity and delicacy of the designs on the casket suggest a date earlier than the gourd vase LS2400, made before 1644.

A griffin included on the back side of the casket LS2067 (Figure 4) exemplifies the complex and minute details that early Indigenous artisans were capable of creating. The figure of the griffin incorporates inset strands of white barniz de Pasto less than half a millimeter in width that outline and ornament the figure. Intricate waving bands and whorls ornament the neck, chest, and tail; cross-hatching on the belly emulates shading; and black strands delineate the wings and feathers composed of transparent and colored barniz over silver leaf. The inclusion of small squares and rectangles of varied colors combined to produce an iridescent effect on the feathers.

Figure 4.

Detail of a griffin. Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2067.

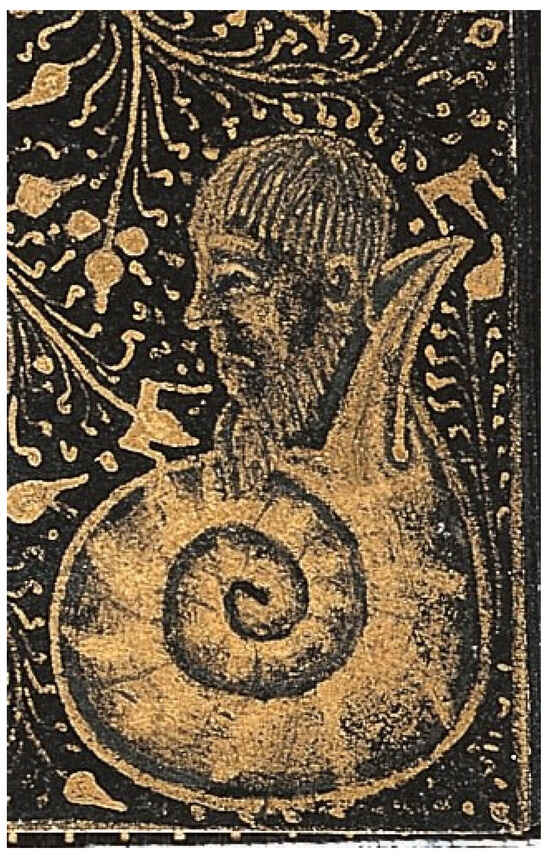

Some Indigenous influences appear on early barniz de Pasto, both matte and brillante, yet Asian influences are largely absent in spite of the fact that Asian lacquers served as the inspiration for the viceregal lacquers. This was probably due to the fact that the Indigenous artisans did not have specimens of the valuable Asian ware for reference at that early date. Most of the early designs were derived from fifteenth- and sixteenth-century European sources, such as illuminated manuscripts, emblem books, prints, and drawings, that were provided by Catholic missionaries to the Indigenous artisans with the idea of applying the Indigenous lacquer techniques to decorative objects that could compete with Asian lacquerwares. The Indigenous artisans often chose to interpret these foreign images within their own cultural heritage, like the snailperson on the Hispanic Society casket (Figure 5), who is depicted with a crown of feathers3 typical of a Kamëntsa shaman of the Sibundoy Valley [18], being the same location from which mopa mopa was sourced for the artisans in Pasto. Snailpersons do not appear in contemporary European printed books or prints, so the images adapted by the artisans in Pasto originated from late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century illuminated manuscripts, similar to the French and Belgian examples seen here from Late Medieval manuscripts in the collection of the Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books at The Hispanic Society of America (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Detail of a snailperson. Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2067.

Figure 6.

Detail of a snailperson. Black Book of Hours (Horae beatae marie secundum usum curie romane), Circle of Willem Vrelant (active Bruges, Belgium, 1454–1481), Bruges, Belgium, ca. 1458. Illuminated manuscript on vellum painted black, 15.2 cm × 10.7 cm × 2.7 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, B251.

Figure 7.

Detail of a snailperson. Book of the Most Valorous Count Artois, and of His Wife, Daughter of the Count of Boulloigne (Livre du tres cheualereux conte d’Artois et de sa femme fille du conte de Boulloigne), France, ca. 1450. Illuminated manuscript on vellum, 26.9 cm × 19.5 cm × 4.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, B1152.

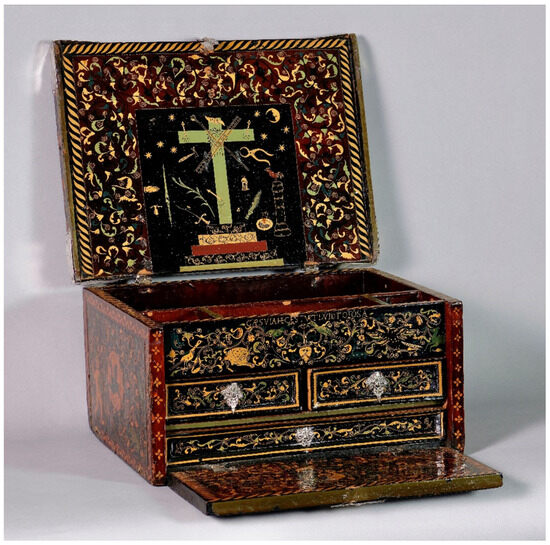

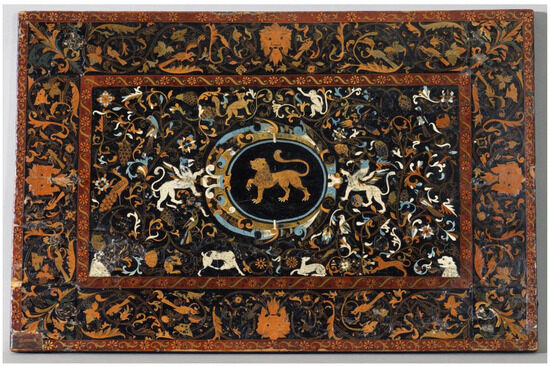

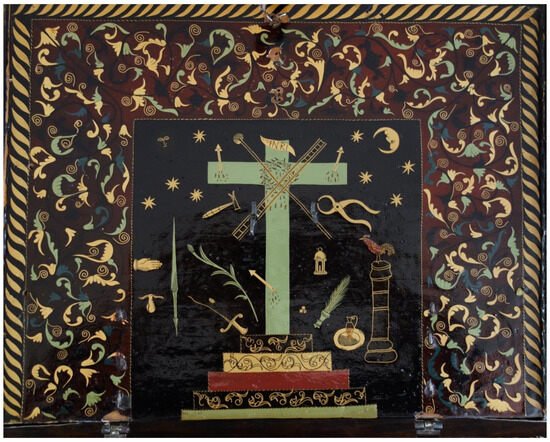

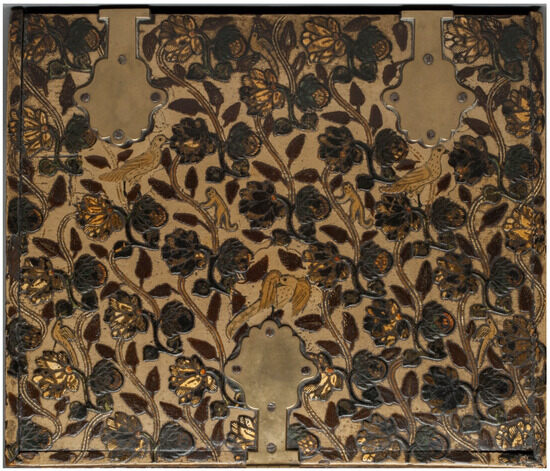

A matte barniz de Pasto table cabinet4 and accompanying tabletop5, acquired in 2019 by The Hispanic Society of America, display equally diverse imagery drawn from Classical mythology, Renaissance, Mannerist, and Indigenous sources (Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). The decorative surfaces are populated with Indigenous and Spanish hunters, dogs, wild boars, armadillos, deer, monkeys, birds, rabbits, jaguars, and lions, intermingled with mythological beasts such as satyrs, griffins, and unicorns, along with Mannerist cartouches and grotesque masks, all surrounded by Renaissance foliate and floral rinceaux. Symbols of the Stations of the Cross depicted on the interior of the lid suggest that the table cabinet was made for a member of the clergy (Figure 8 and Figure 10).

Figure 8.

Table cabinet, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. Barniz de Pasto on Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata), with silver fittings, 49 cm × 49.4 cm× 47 cm open, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

Figure 9.

Tabletop, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. Barniz de Pasto on Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata), 43.7 cm × 66 cm × 1.8 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2447.

Figure 10.

Detail of the Stations of the Cross on the interior of the lid. Table cabinet, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

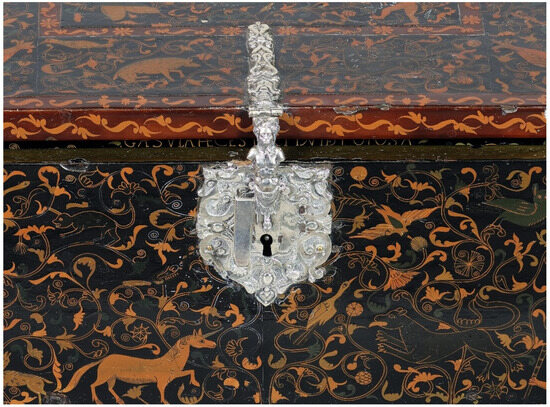

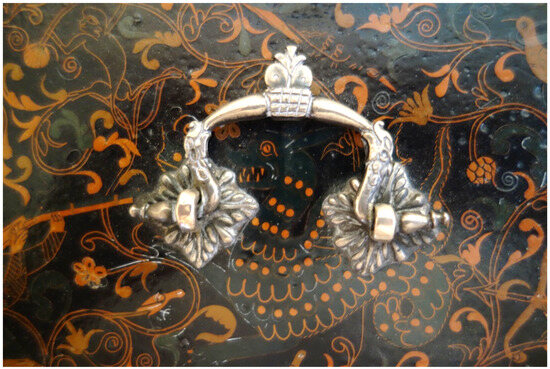

Of all known examples of barniz de Pasto from the earliest period (1625–1650), the silver fittings on this table cabinet are truly exceptional, especially the ornate lock escutcheon and hasp (Figure 11). The lock escutcheon is chased and engraved with a Renaissance-style sculptural hasp with the half figure of a herm, borrowed from ancient Greek sculpture.

Figure 11.

Detail of the silver lock escutcheon and hasp with a cast figure of a herm. Table cabinet, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

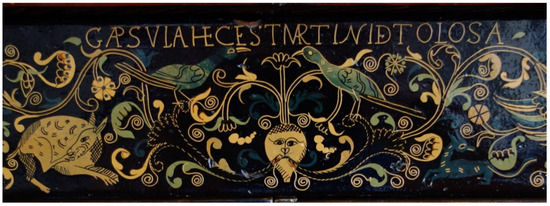

This table cabinet represents the only known example of the incorporation of an owner’s name as part of the original surface design on any piece of seventeenth-century barniz de Pasto. The ownership inscription appears on the interior front panel above the drawers, which reads in Latin: CAPSULA H(A)EC EST MARTINI DE TOLOSA; in English translation: THIS IS THE BOX OF MARTIN DE TOLOSA (Figure 12). Fortunately, it has been possible to identify the owner and accordingly provide an approximate date for the writing cabinet and tabletop.

Figure 12.

Martín de Tolosa ownership inscription on the interior front panel. Table cabinet, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

Colombian and Spanish archival sources reveal that Martín de Tolosa was a cleric, priest, chief sacristan, and chapel master of the Cathedral of Popayán from at least 1630 to 1643 [19,20,21,22]. Based on this documentation, the table cabinet and tabletop are the earliest known datable examples of seventeenth-century barniz de Pasto based on provenance.

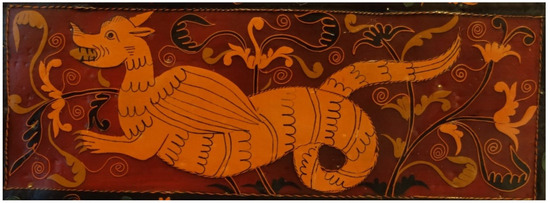

Within the array of European mythological creatures that populate the surfaces of early pieces of barniz de Pasto, a mythological beast that variably resembles a dragon, winged serpent, sea monster, or seahorse blends in perfectly. However, the beast is not of European origin but is an amaru/amaro of Andean mythology, a serpent creature that inhabited the underworld and was associated with all forms of water. The amaru is depicted in Andean decorative arts with a head similar to a dragon, two bat-like wings, two legs with long claws, and a body and tail covered with scales, although it can also take on the appearance of a sea horse or sea monster. Since depictions of the amaru were uncommon in Andean decorative arts until the seventeenth century, it is difficult to know whether or not the Indigenous artisans were attempting to copy European dragons in their own style or whether they were intentionally substituting a beast from Andean mythology. The Italian Jesuit historian Giovanni Anello Oliva (1572–1642) provided a description of the amaru similar to other contemporary accounts in his important manuscript Historia del reino y provincias del Perú y vidas de los varones insignes de la Compañía de Jesús (1625):

a serpent so ferocious and fearsome … as large as the biggest animal on earth, with wings like a bat, short and very thick arms with large nails … eyes polluted with fire and blood, the tongue quivering … covered with hard scales … and from this stupendous animal the Inca took the sobriquet Amaro, as such were these serpents called [23].

At least thirteen barniz de Pasto cabinets, coffers, chests, and caskets in public and private collections include depictions of amaru6. Most of the pieces are early, 1625–1650, although a few are from later in the seventeenth century. It is useful here to illustrate how the depictions of the amaru vary in a group of early works as a first step in identifying workshops and establishing a chronology for dating pieces. No two depictions of amaru on barniz brillante caskets, coffers, or chests are identical, although they are always presented with extended barbed tongues and as opposing pairs on the front, top, or back exterior surfaces. Representations of an amaru similar to the one on the Hispanic Society’s casket LS2067 (Figure 13) can also be found on small coffers, chests, or caskets at the Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX (2018.351); the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA (Figure 14); and the Victoria and Albert Museum, London (Figure 15). Conceivably, all four could have been produced in one or two workshops over the span of a few decades.

Figure 13.

Detail of an amaru. Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2067.

Figure 14.

Detail of an amaru. Chest, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1650. Barniz de Pasto on wood, with silver fittings, 17.2 cm × 23.2 cm × 13.3 cm, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2008.34.

Figure 15.

Detail of an amaru. Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1650. Barniz de Pasto on wood, with iron fittings, 13.5 cm × 21.3 cm × 9.5 cm, London Victoria and Albert Museum, W.7-2018.

In general, there is a common evolutionary trait within the decorative arts in viceregal Latin America in which the earliest pieces exhibit the greatest complexity and attention to detail. In the case of barniz brillante, this is evidenced in the complex patterns created by overlaying minute colored design elements, such as small squares, triangles, and circles, on individual figures. The same applies to the outlining, cross-hatching, and spirals used to reinforce parts of figures and create shading or create complex patterns using fine strands of black or white mopa mopa, as seen earlier in the undulating lines and spirals on the body of the griffin on the casket LS2067 (Figure 4). Based on the visual examination criteria discussed within a range of 1625–1650, The Hispanic Society of America casket (LS2067) would be the earliest, and the Victoria and Albert’s would be the latest.

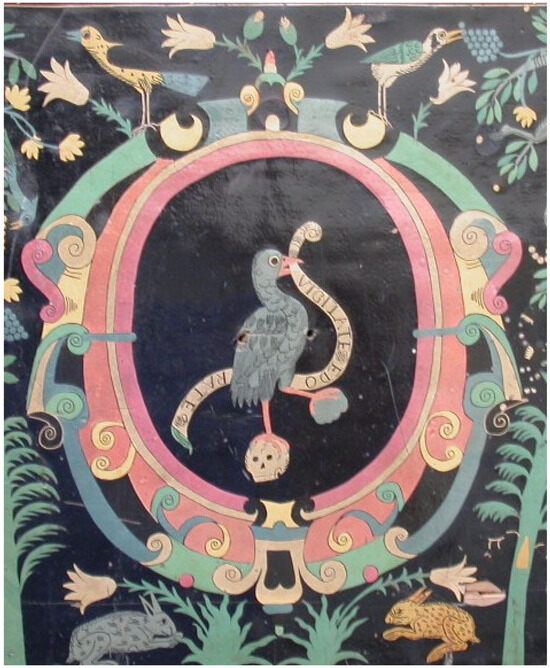

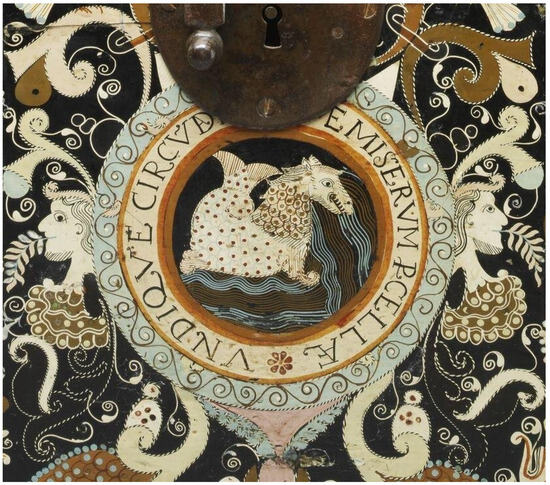

Similar comparisons are possible on three early matte barniz de Pasto table cabinets with hinged fall-fronts and hinged lids in the Victoria and Albert Museum, The Hispanic Society of America, and in the collection of Francisco Marcos Manzano, Salamanca, Spain, all dating from 1625 to 1650. All three cabinets show striking similarities in their iconography. Each incorporate an impresa with a motto in the decorative scheme, and one impresa appears on all three with the figure of a crane and a ribbon banner with the motto in Latin “VIGILATE” or “VIGILATE ET ORATE”7; in English “Be watchful” or “Watch and pray” (Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18).

Figure 16.

“VIGILATE” impresa. Table cabinet, the left side of the exterior, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625–1650. Barniz de Pasto on wood, 23.2 cm × 37.7 cm × 27 cm, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, W.5-2015.

Figure 17.

“VIGILATE” impresa. Table cabinet, interior of fall-front, Pasto Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

Figure 18.

“VIGILATE ET ORATE” impresa. Table cabinet, interior of lid. Pasto Colombia, ca. 1625–1650. Collection of Francisco Marcos Manzano, Salamanca, Spain.

The Hispanic Society’s table cabinet (LS2446) includes two variant depictions of an amaru, which would most likely indicate two separate artisans working on the same piece, and the Victoria and Albert’s cabinet has still another variant, yet no two amaru are depicted the same on any of the three (Figure 19, Figure 20 and Figure 21).

Figure 19.

Detail of an amaru. Table cabinet, center top of lid, under a silver handle, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

Figure 20.

Detail of an amaru. Table cabinet, back exterior panel, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446.

Figure 21.

Detail of an amaru within a cartouche for an impresa. Table cabinet, exterior of the fall-front, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625–1650. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, W.5-2015.

Since a date range of 1630–1643 has been established for the Hispanic Society’s table cabinet, and given the similarities between all three, they all would fall within the early date range of 1625–1650. The V&A cabinet has a complex and uniform decorative program with imprese on all five exterior sides and two interior sides, which suggests that it was made as a gift for an erudite member of the nobility or religious elite. All of the pieces were either commissioned by the owner or given as gifts. They might have been made in one workshop over time using barnizadores of different skill levels based on the price paid, but they clearly represent variations in a specific early design group originating at Pasto.

Another unusual European motif, that of a white hand, only appears on a few early pieces of barniz de Pasto dating from the period of 1625–1650. The exact symbolism of the hand is unclear, other than being a clever decorative motif. The Hispanic Society’s casket (LS2067) includes seven white or flesh-colored hands, a scalloped sleeve cuff at the base of the hand, and black outlines for the fingernails, all of which are positioned at the bottom center above the border on all four sides, and at bottom front and back center of the domed lid, two on the front and one on the back. The hands in matte barniz stand out in high contrast with the barniz brillante that covers the rest of the casket. With the thumb and index finger, the hand holds the stem of flowers that rise upward and spread to the sides (Figure 22).

Figure 22.

Detail of a hand with cuff. Casket, front of the domed lid, at the bottom right side of a silver hasp, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2067.

A similar pair of white matte hands with sleeve cuffs are found on a diminutive perfume sprinkler made from a calabash gourd (totuma), decorated entirely in matte barniz, with a silver tapered nozzle perforated at the top, in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (Figure 23).

Figure 23.

Detail of white hands. Flask and stopper, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625–1650. Barniz de Pasto on a calabash gourd flask, with a silver stopper and sprinkler, 9.525 cm × 4.76 cm, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 1577–1902.

The hands are in opposition, with the palms facing up and down, delicately holding with two fingers a heart composed of double white outlines. Classical foliate designs with flowers, combined with birds and a stylized fox or cat, make up the rest of the decoration. The heart possibly represents the symbol for the Augustinian order, which has been in Pasto since the late sixteenth century. In this context, the heart would signify that the perfume sprinkler was commissioned by or for an Augustinian. It should also be noted that the Augustinians probably were the missionaries that furnished the early barniz de Pasto Indigenous artisans images of mythological beasts and exotic creatures that served as their inspiration for creating the fantastic figures that populate their lacquerware.

Pieces produced in the second half of the seventeenth century into the early eighteenth century are densely decorated with an eclectic mix of motifs drawn from European, American, and Asian sources: the squirrel-and-grapevine motif common to sixteenth-century Chinese and Japanese decorative painting, as well as seventeenth-century lacquers from the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa); peonies and carnations from Chinese porcelains and textiles; parrots, monkeys, jaguars, bears, armadillos, alpacas, giant anteaters, wild boar, palm trees, passion flowers, and fruits native to Colombia; as well as the double-headed eagle of the Hapsburg kings of Spain, horses, lions, griffins, pelicans, and baskets of fruit borrowed from European heraldry, mythology, and still life paintings.

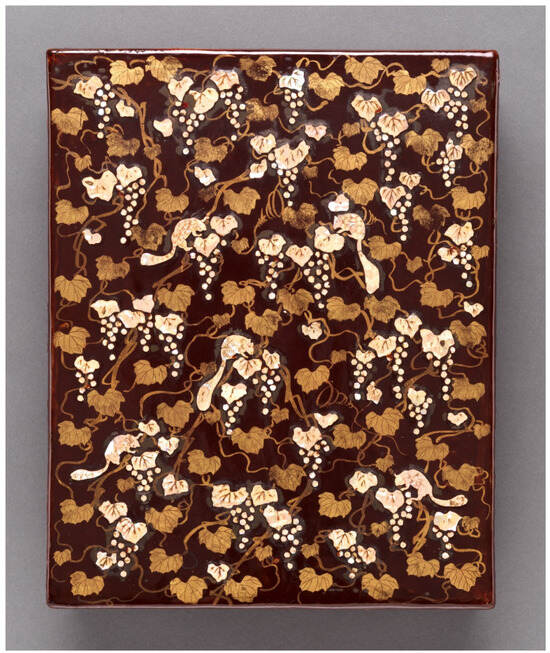

Most of these influences are combined on a table cabinet ca. 16848 that, without doubt, was commissioned by the bishop of Popayán, Cristóbal Bernardo de Quirós (1618–1684), as a gift for his brother, Gabriel Bernardo de Quirós, secretary to Charles II, who had been granted the title of Marquis of Monreal on 27 December 1683 [24]. The exterior of this table cabinet exemplifies the fusion of Asian and Indigenous motifs, where the squirrel-and-grapevine motif has been reinterpreted with an endemic monkey-and-passion flower vine motif (Figure 24 and Figure 25).

Figure 24.

Table cabinet with decoration of flowering vines and monkeys, top exterior, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1684. Barniz de Pasto on wood, with brass fittings, 19 cm × 36 cm × 30.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2000.

Figure 25.

Writing box with decoration of grapes and squirrels, top exterior, Japan (Ryūkyū Islands), 17th century. Black lacquer with mother-of-pearl inlay and gold painting, 6 × 26.2 × 21.6, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020.323.11a–e.

The subtly curved edges and slightly elevated fall front of the table cabinet more closely resemble early seventeenth-century Japanese Namban-style lacquer cabinets produced for the European market rather than traditional Spanish models (Figure 26). The synthesis of these diverse artistic and cultural traditions is most evident on the interior of the lid (Figure 27 and Figure 28).

Figure 26.

Table cabinet, closed, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1684. Barniz de Pasto on wood, with brass fittings, 9 cm × 36 cm × 30.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2000.

Figure 27.

Table cabinet, open, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1684. Barniz de Pasto on wood, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2000.

Figure 28.

Table cabinet, interior of the lid with the coat of arms of the Quirós family, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1684. Barniz de Pasto sobre madera, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2000.

Here, the coat-of-arms of the Quirós family is prominently displayed over a basket filled with tropical fruits, flanked by parrots, all set against a rich background of carnations, vines, leaves, and agraz berries9, reminiscent of contemporary Chinese embroidered textiles. It is worth noting that the brass fittings are not original to the cabinet but are lesser quality replacements for the fine silver fittings that probably were removed to raise money in the eighteenth century when the owner was having financial trouble. Unfortunately, most of the early barniz de Pasto cabinets suffered the same fate.

By the end of the seventeenth century, new designs appeared on some of the finest pieces, in which the overall floral and foliate designs became almost abstracted into a series of intricate swirling geometric designsreminiscent of Islamic interlace patterns. Flowers were more conventionalized and served as the points from which the swirling foliate designs emanated. Three pieces in the Museo de America in Madrid exemplify this style: a large chest with exceptionally intricate overall decoration (inv. no. 06675); a tray with scalloped borders in the form of a seventeenth-century Spanish barber’s basin (inv. no. 12242); and a portable writing desk (inv. no. 2015/08/01) [25,26]. The mythological creatures from earlier in the century have disappeared in favor of exotic Indigenous species such as giant anteaters, which stand out in matte black barniz on each side of the center roundel of the barber’s basin tray, or the matte black alpacas on each side of the center roundel of the interior of the fall front. In contrast with seventeenth-century examples of barniz de Pasto, those from the eighteenth century exhibit, in general, a notable decline in quality as the century progressed.

2.3. Pintura, Barniz, and Peribán Painting: Historical Context

The first Mexican lacquerware produced as a luxury object was attributed and documented by contemporary historians to Peribán, Michoacán. Unfortunately, since Peribán lacquerware is rare and examples survive in a very limited number of museums and private collections, it has been studied by only a few modern scholars who have direct access to the pieces. Early historical accounts refer to the lacquerware of Michoacán as pinturas (paintings) or barnices (varnishes). The terms laca (lacquer) and maque (from the Japanese word maki-e for lacquers incorporating gold or silver) did not come into use until the eighteenth century with the introduction of the Chinoiserie style, which emphasized gold in the decoration. Painted and lacquered gourd cups (jícaras) and bowls were the staple wares of the Purépecha lacquer artisans in central Mexico throughout the viceregal period, but what may be the earliest firsthand account of Indigenous lacquer being applied to wooden objects for use by Spanish missionaries and settlers comes from Tiripitío in Michoacán, located midway between Morelia (Valladolid) and Pátzcuaro. Pedro Montes de Oca, the chief magistrate of Tiripitío, writing in 1580 in response to a questionnaire on the jurisdiction sent by order of Philip II, described the wooden objects “painted” by the Purépecha artisans:

Many carts and plows, are made in this town from the oaks and holm oaks; and other things from the pines, a lot of planking for houses, doors, boxes, and desks and table cabinets and tables [and] trays. Large quantities are made of everything, because there are very good and polished Indian carpenters here, and very excellent; and when completed they are given to painters for painting, of which there are in this town the most polished and curious that there are in this New Spain for this purpose; such that the desks and writing cabinets can be given and presented to any prince [27].

The next references to Purépecha lacquer artisans appeared in a history of the Augustinian order in Michoacán, completed in 1644 and published in 1673 by Diego Basalenque (1577–1651). Speaking of the skills of the Purépecha in the villages of San Juan Parangaricutiro and Zacan, Basalenque wrote:

And in terms of wealth they exceed [Zirosto], because they have a lot of dealings and contracts, taking from the hot lands to Spanish Towns, fruits, brown sugar and honey, because they have many mules, and the things they make in their Towns that they profit from, such as paintings, and trays, inlays, agave fiber rope, are all everyday-wares in Spanish towns [28].

Basalenque went on to describe how the Purépechas of Pátzcuaro came to learn their trades and, in the process, made a clear reference to Indigenous inlaid lacquerwork:

the Bishop [Vasco de Quiroga]; he, who with his great talent, also ordered that the natives all have their entertainments and trades, and thus there were many carpenters who made boxes, desks, writing cabinets, paintings, and other things, which were traded to other cities. There were blacksmiths, tailors, shoemakers for whose works they came for to carry away. Others made shawms, flutes, trumpets, sackbuts, to provide the others singers, others organs, others images, with paint, also painting gourds, trays, making inlays with the colors invented here.

In an eighteenth-century chronicle of the Augustinian order in Michoacán, Matías de Escobar (d. 1749) described how the Augustinians introduced Spanish carpentry skills to the Purépecha of Tiripetío in the sixteenth century and how the Purépecha created their own style by adding Indigenous lacquer:

They gave them master carpenters because they had enough wood to work with, and they learned the art so well that their writing desks became famous and their coffers received applause, because making a diphthong of what they learned from the Spanish masters with what they knew, they formed a new graft on the woods of the Castilian models, drawers of desks, boxes and writing cabinets, they added their lacquers and their paintings, and made their work unique, because at the same time the Spanish design was dressed in Indian clothing [29].

Although the Indigenous lacquer technique was adapted earlier to wooden objects of Spanish design at Tiripitío, Escobar singles out Peribán lacquerware as the finest:

The painting of Periban up to today not imitated by any other nation, had its origin in this province, and apart from being so showy, the varnish is so permanent that it stubbornly defends itself against time, because colors having the quality of fading with age, this painting bets, persists, with aging endurance, the color becoming one with the wood, perhaps to further establish its permanence; it is the technique of this work, opening the work with the burin, and embedding the colors in the holes, supplying the variety of shades of those colors, without any wood showing

Escobar clearly makes a point of noting that the earlier lacquerware from Tiripitío did not cover the entire surface of the objects, thus leaving areas of exposed wood, unlike all of the later Spanish American lacquerware beginning with Peribán. Regrettably, no examples of the early utilitarian lacquerware produced at Tiripitío or Pátzcuaro are known to survive. Later in the text, after describing the early lacquerwork at Tiripitío, Escobar describes how the Purépecha had not excelled as traditional painters but how they had triumphed with the lacquerware from Peribán:

For the most part they do not equal the Europeans as painters, however those who have learned in Mexico, can take up a palette in the workshops of Apeles. They do not take great pains in the work; because they know they will not be paid for it, and so they act as if they will not receive the pay they deserve; they themselves have their paints and oils with which they stain their trays, exquisite gourds, called Peribán; which, not content to be sought after in all of New Spain, for their curiosity, they went on to be celebrated in Spain.

The production of lacquerware at any one village would have waxed and waned over time, so it is logical to assume that given the relatively close proximity of these villages, the Purépecha artisans could easily have moved from one village to another as needed.

2.4. Peribán Lacquerware: Techniques, Stylistic Influences, and Chronology

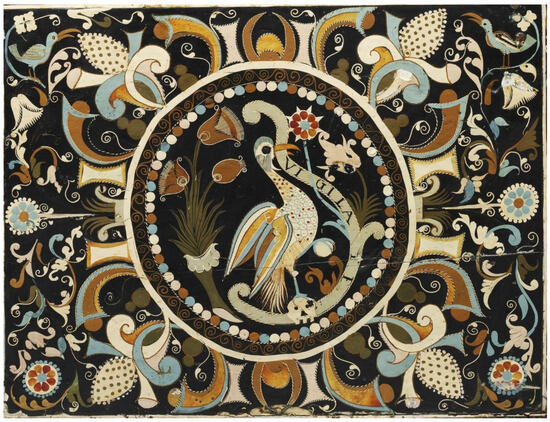

The introduction of Asian lacquerware to the Americas and Europe through the Manila Galleon in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries resulted in the adaptation of the Indigenous Mexican lacquer technique to the decorative arts as luxury goods destined for the Spanish market. In the seventeenth century, Peribán was the principal center of production. Peribán, situated in western Michoacán near the border with Jalisco, was credited by contemporary historians with the establishment of the earliest workshops of Spanish American lacquerware in Mexico. The Franciscan chronicler Alonso de la Rea (ca. 1605–1661), writing in 1639, credited the Purépecha lacquer artisans with having invented in Michoacán the art that he called “Peribán painting [30]”. He praised this lacquer not only for its beauty but also for its durability and resistance to hot liquids. De la Rea described their technique and observed that the artisans decorated a variety of fine writing desks, boxes, chests, trays (bateas), gourd bowls (tecomates) and cups (jícaras), and other curious objects with “figures, mysteries, or landscapes”. The earliest and finest examples known of Peribán lacquerware date to ca. 1625–1650, exemplified by an exceptional batea ca. 1625 (LS1808) in the collection of The Hispanic Society of America (Figure 29)10.

Figure 29.

Tray (batea), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1625. Mexican lacquer on wood, 8 cm × 56.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1808.

The acquisition of this batea serves as an example of how Peribán lacquerware, like early barniz de Pasto, went unrecognized by most dealers, museum professionals, collectors, and scholars throughout the twentieth century due to the lack of published images and examples in museum collections in the Americas. I came across this batea in 1998 at an antiques fair in New York City and immediately recognized it as an extremely rare example of seventeenth-century Peribán lacquerware. The dealer identified it as being eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Peruvian and said that another dealer had already offered it to the Brooklyn Museum, but they were not interested. We acquired the batea after it was examined by the curatorial and conservation staff and approved by the acquisitions committee.

More than five years later, I was showing some visiting researchers in the Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books photos taken in 1925 of the contents of the estate of Arabella Huntington (1850–1924), mother of Archer Milton Huntington, the founder of The Hispanic Society of America. One inconspicuous photo showed three bowls that appeared to be Mexican lacquerware propped up at the base of a cabinet, and upon examination with a loupe, the batea at the far left proved to be the same one that we had acquired in 1998 (Figure 30).

Figure 30.

Photo inventory of the estate of Arabella D. Huntington, 1925. Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books, The Hispanic Society of America.

Ironically, it had been in Arabella Huntington’s collection for years, possibly even acquired on their trip to Mexico City in 1889. Archer Huntington clearly was unaware that it was Mexican; otherwise, he surely would have donated it to the Hispanic Society. Another enigma is that these bateas are not included in the written inventory of the estate and somehow disappear without notice from the Fifth Avenue mansion. The destiny of the other two bateas at the center and far right in the photo remains unknown.

The inlay technique of Peribán lacquerware was labor-intensive since each application of lacquer required burnishing with a soft cloth before completely drying, a process that took several days. The same process was applied to incised cross-hatching, which was then filled with lacquer of a contrasting color in order to create a shading effect on figures, a technique clearly borrowed from contemporary engravings (Figure 31).

Figure 31.

Details of cross-hatching for shading effects. Tray (batea), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1625. Mexican lacquer on wood, 8 cm × 56.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1808.

Typical motifs on early Peribán bateas include a central Mannerist strapwork cartouche that frames allegorical or mythological figures, customarily surrounded by four smaller cartouches of similar theme, as seen on a second batea ca. 1625–1650 (LS1978) in The Hispanic Society of America (Figure 32)11. The Hispanic Society batea ca. 1625 (LS1808, Figure 29) is unique in having only one central cartouche, which strongly suggests that it predates all other known Peribán bateas since it was made before the design format was established with the addition of the four smaller surrounding cartouches.

Figure 32.

Batea (tray), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1650. Mexican lacquer on wood, 10.2 cm × 56.7 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1978.

The cartouches are surrounded by imaginary landscapes populated with courtly figures and rural laborers in late sixteenth-century European dress engaged in all manner of courtly festivities and rural activities, including farming, hunts, and combats. The compulsion to leave no space undecorated in horror vacui, a characteristic of Spanish American seventeenth-century decorative arts, is epitomized by early Peribán lacquerware. A fantastic menagerie of domestic animals, wildlife, and mythical creatures inhabit the scenes—dragons, unicorns, deer, wild boar, eagles, and lions—as well as the occasional New World species, such as the armadillo seen at the top center in the detail of the ca. 1625 batea (Figure 31). Dutch and Flemish prints served as the primary source for these images, yet the creativity of the Indigenous artists in their interpretation of European models remains omnipresent.

A very limited number of Peribán pieces survive, consisting primarily of bateas, chests, trunks, and fall-front writing cabinets (bufetillos and vargueños). The seventeenth-century bateas from Peribán became so famous that any lacquer tray was called a peribana into the nineteenth century. The only known contemporary image of Peribán lacquerware is a jícara (gourd cup), included with other exotic luxury objects in the painting Still Life with an Ebony Chest, 1652, by Antonio Pereda (Spain, 1611–1678), in The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia [31]. The jícara is seen sitting on the top right corner of the ebony chest. The winged creature on the front of the jicara is a siren, a creature from Greek mythology with the body of a bird and the head of a human, also found on the outer border on the underside of all early Peribán bateas.

Two Peribán-domed writing cabinets (bufetillos) in the collection of the Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales in Madrid most likely were a gift from Philip IV, King of Spain (1621–1665), or from a high Church official or member of the nobility, to the Discalced Carmelite nuns (inv. 00612072-73) [10]. Both writing cabinets display scenes of triumphal chariots and courtly figures. The same applies to a batea in the Conceptionist convent at Ágreda, Soria, home to the mystic Sister María de Ágreda (1602–1665), who was a long-time correspondent and advisor to Philip IV [10]. All three of these pieces, in their overall design and idiosyncratic style of depicting human and animal figures, are indications of having been produced in the same workshop between 1625 and 1650.

The evolution of the principal designs and motifs on Peribán over the course of the seventeenth century provides a means for setting approximate dates for extant pieces as they go from finely detailed to conventionalized. The figure of a siren, or winged mermaid, and the accompanying designs seen on the gourd cup in Pereda’s still life of 1652 are similar to those on the reverse of both bateas in The Hispanic Society of America, as well as the decoration on the front of a batea ca. 1675 in the Victoria and Albert Museum (Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35).

Figure 33.

Tray (batea), reverse, Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1625. Mexican lacquer on wood, 8 cm × 56.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1808.

Figure 34.

Tray (batea), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1650. Mexican lacquer on wood, 10.2 cm × 56.7 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1978.

Figure 35.

Tray (batea), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1675. Mexican lacquer on wood, 5 cm × 43 cm, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 158–1866.

On the reverse of both of the Hispanic Society’s bateas, a repeating design around the side combines four roundels with female musicians and male warriors, with winged sirens whose tails transform into divergent scrolling vines with fruits and flowers, with the scroll nearest to the siren terminating in a white bucranium, or ox skull. A common element in Greco–Roman architectural friezes, bucrania were symbols for sacrifice and death that were adopted in the Renaissance as a Classical motif in both architecture and the decorative arts. The Victoria and Albert’s batea repeats the general design of the two Peribán bateas with a central strapwork cartouche and surrounding smaller roundels. The major difference here is that the repeating design from the underside of the earlier bateas becomes the decoration for the front. The sirens remain recognizable, but the vines have become a mass of highly conventionalized motifs where the bucranium remains white, but the form is largely unidentifiable. Two additional bateas ca. 1675–1700 at the Victoria and Albert Museum display bolder, simpler designs not found on other Peribán bateas (Figure 36 and Figure 37)12.

Figure 36.

Tray (batea), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1675–1700. Mexican lacquer on wood, 5.4 cm × 45.7 cm, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 157–1866.

Figure 37.

Tray (batea), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1675–1700. Mexican lacquer on wood, 5.5 cm × 43.7 cm, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 156–1866.

This decorative style combines Indigenous and highly conventionalized European motifs in a limited three-color palate on black ground. Here, the decoration is a version of the previous sirens and scrolling vines. The sirens have become decorative scrolls, and the only motif that is vaguely recognizable from the earlier bateas is the bucranium. These bateas were probably intended for the local population and not for export to Spain or for the creole (criollos) elite of New Spain. All three bateas in the Victoria and Albert Museum were acquired in Spain from the same dealer in 1865, which would suggest that they probably had remained together since the time that they left Mexico.

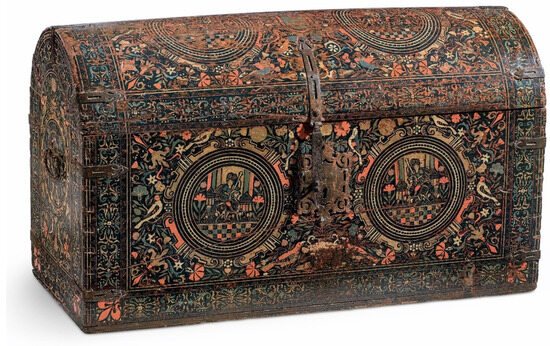

At least seven Peribán large domed trunks (baúles), all ca. 1650–1675 and probably from the same workshop, survive in collections in the United States, Spain, and Venezuela. Trunks in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Figure 38) [32], the Museo de Arte Colonial, Caracas, Venezuela [33]; the church of Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, Las Palmas, Canary Islands; and the Palace of the Countess of Lebrija in Seville all share a common decorative scheme similar to the early bateas, with two strapwork cartouches on the front and on the domed top of the trunk, as well as single cartouches on each end.

Figure 38.

Trunk (baúl), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1650–1675. Mexican lacquer on wood, iron fittings, 64.8 cm × 110.5 cm × 47 cm, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2015.69.1.

Another trunk in the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan, Madrid, shares a similar decorative scheme, except the two cartouches are substituted by the coat of arms of a member of the Valdés family from Asturias, and the domed top repeats the arms of the Order of Santiago, all surmounted by coronets of a marquis.

A second trunk in the Palace of the Countess of Lebrija displays a unique mudéjar geometric decoration formed from eight-pointed stars (Figure 39).

Figure 39.

Trunk (baúl), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1650–1675. Mexican lacquer on wood, iron fittings, Palace of the Countess of Lebrija, Seville, Spain.

The front and sides of the exterior of the trunk have stylized floral and foliate borders that include mudéjar interlacery designs, as found on the carved stone door and window surrounds, as well as the background of painted frescoes in the sixteenth-century Hospital Real de la Purísima Concepción in Uruapan, Michoacán. Within the borders are panels of finely detailed Islamic interlacery similar to the mudéjar artesonado ceilings that were common in many sixteenth-century churches in Michoacán. The vase with flowers seen here under the lid is a common motif among Peribán trunks and writing cabinets (vargueños), although this example adds a border of bobbin lace.

By the mid-eighteenth century, the production of bateas, portable writing desks, and trunks had ceased at Peribán. According to Antonio Alcedo y Bejarano (1736–1812), by the third quarter of the eighteenth century, Peribán specialized solely in lacquered jícaras (gourd cups), in which all of the Purépecha inhabitants were employed:

The population [of Peribán] is made up of 100 families of Spaniards, Mestizos and Mulattoes, and 66 of Tarascan Indians who make many gourd cups because it abounds with little gourds, and they paint them beautifully in various colors, forming the main source of their commerce because of the esteem they have everywhere [34].

Since gourd cups were inexpensive utilitarian objects, it is not surprising to find that no examples are known to survive.

3. Conclusions

The decorative arts of Asia had a profound impact on Latin American decorative arts during the Viceregal era, none more so than the Indigenous lacquer traditions of Mexico and the Andes. As demand exceeded supply for the exotic and expensive Asian lacquerware brought to Acapulco by the Manila galleons, Indigenous lacquer artisans in Mexico and Colombia began to apply their skills to the production of lacquerware for the Spanish market. Catholic missionaries were responsible for encouraging the lacquer artisans to adapt their ancient techniques to new forms, as well as providing them with European prints, drawings, and illuminated manuscripts that served as models for the pictorial decorations found on the earliest known examples from Pasto and Peribán. Beginning in the second half of the seventeenth century and through the eighteenth century, Asian and Indigenous motifs were incorporated into the decoration of Spanish American lacquerware. This resulted in lacquerware of enormous diversity that combined Indigenous, European, and Asian decorative styles and forms.

The finest Spanish American lacquerware became as highly prized in Europe and America as the finest Asian wares. Spanish America’s lacquerwares were treasured possessions brought back to Spain by royal officials, sent as gifts for the secular and ecclesiastical aristocracy of Europe, and were decorative objects that graced the churches and noble palaces of the viceroyalties. The exceptional lacquerwares of Colombia and Mexico that survive today stand as a testament to the creative genius of the Indigenous lacquer artisans as they expanded the possibilities of their art through the Indigenous, Asian, and European cultural exchange of the seventeenth century.

The Indigenous lacquer artisans of Spanish America, inspired by the challenge of creating lacquerware of comparable appearance and quality to Asian lacquerware, produced works of enormous complexity in both technique and iconography. In the course of the seventeenth century, virtually all Asian lacquer decorative techniques were copied or simulated by the lacquer artisans of Mexico and Colombia, including Peribán inlay in Mexico, relief decorative techniques in Colombia, and the use of silver leaf underneath layers of colored barniz de Pasto to create the effect of shimmering gold, silver, and iridescent feathers. The meticulous and intricate techniques of the early Indigenous artisans, in combination with the motifs and design programs they employed, establish a starting point for dating the Spanish American lacquerware as they evolved in the seventeenth century. The application of this methodology, in combination with more extensive radiocarbon dating of significant pieces, will ultimately yield a greater understanding of the different stages in the evolution of barniz de Pasto and Peribán lacquerwares.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage7080204/s1, Supplementary Material S1: Spanish version of this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author sincerely thanks Natasha Vargas (translator), Robert Esposito, and Laura Ramirez Polo (reviewers) from Rutgers University for the version of this article in Spanish.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1. | Casket, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1625. Barniz de Pasto on wood, with silver fittings. 19.2 cm × 27.2 cm × 13.7 cm. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS 2067. Provenance: Simois Gestión de Arte, Madrid, 2002, acquired by The Hispanic Society of America, 2002. |

| 2. | Gourd vase, Pasto, Colombia, before 1644. Barniz de Pasto on a calabash gourd (totuma), H 12 cm. LS2400. |

| 3. | The crown of feathers seen on the snailperson most likely represents the earliest recorded image of a Kamëntsá shaman’s crown of feathers, an image of profound significance for the cultural history of the Kamëntsá. |

| 4. | Table cabinet, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. Barniz de Pasto on Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata), with silver fittings. 20 cm × 39.7 cm × 30.7 cm. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2446. Provenance: Martín de Tolosa, Sacristan, Popayán Cathedral, Popayán, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643; Butterfield’s, San Francisco CA, Selected Furniture and Works of Art, 23 March 1983, Sale 3306G, lot 1945; Richard Yeakel Antiques, Laguna Beach CA, 1983; Klaus Schilling, Irvine CA, 1983–1987; Sotheby’s, European Works of Art, New York, 24 November 1987, lot 62; Richard Worthen Galleries, Albuquerque NM, 1991; Kurt Schilling, Newport Beach and Morro Bay CA—Santa Fe NM, 1991–2019; acquired by The Hispanic Society of America, 2019. |

| 5. | Tabletop, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643. Barniz de Pasto on Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata). 43.7 cm × 66 cm × 1.8 cm. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS2447. Provenance: Martín de Tolosa, Sacristan, Popayán Cathedral, Popayán, Colombia, ca. 1630–1643; Butterfield’s, San Francisco CA, Selected Furniture and Works of Art, 23 March 1983, Sale 3306G, lot 1945; Richard Yeakel Antiques, Laguna Beach CA, 1992; Klaus Schilling, Newport Beach and Morro Bay CA—Santa Fe NM, 1992–2019; acquired by The Hispanic Society of America, 2019. |

| 6. | The public collections include The Hispanic Society of America, NY (LS2067, LS 2446); Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, TX (2018.351) https://blanton.emuseum.com/objects/22542/coffer?ctx=c4a45705ff07ca4bd87f7a75d5d25b0b7586f0dc&idx=3 (accessed on 6 July 2024); Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA (M.2008.34); Victoria and Albert Museum, London (W.5-2015, W.7-2018); and Museo de America, Madrid (inv. no. 06775). |

| 7. | The motto is taken from Matthew 26:41 of the Latin Vulgate Bible, being the words spoken by Jesus to his disciples Peter, James and John in the Garden of Gethsemane. Vigilate et orate also is a famous motet for Palm Sunday by the Spanish Renaissance composer of sacred music Cristóbal de Morales (ca. 1500–1553). |

| 8. | Table cabinet, Pasto, Colombia, ca. 1684. Barniz de Pasto on Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata), with brass fittings. 19 cm × 36 cm × 30.5 cm. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, New York, LS2000. Provenance: Gabriel Bernaldo de Quirós y Mazo de la Vega, First Marquis of Monreal, ca. 1685; Alcalá Subastas, Madrid, 10–11 May 2000, lot 454; Caylus, Madrid, 2000; acquired by The Hispanic Society of America, 2001. |

| 9. | Agraz (Vaccinium meridionale Swartz) is a shrub native to Colombia, growing up to seven meters tall, found at altitudes from 2400 to 4000 meters, which produces a dark blue or purple fruit that grows in grape-like clusters. Agraz is from the family Ericaciae, which includes blueberries and cranberries. |

| 10. | Batea (tray), Peribán, Michoacán, Mexico, ca. 1625. Mexican lacquer on wood, 8 cm × 56.5 cm. New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1808. Provenance: Arabella D. Huntington (1850–1924), New York, until 1924; estate of Arabella D. Huntington, New York, 1924–1926; Martin Cohen, New York, 1998; acquired by The Hispanic Society of America, 1998. |

| 11. | Batea (tray), Peribán, Michoacán, ca. 1650. Mexican lacquer on wood, 10.2 cm × 56.7 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America, LS1978. Provenance: Catalina K. Meyer, New York, to 1997; Estate of Catalina K. Meyer, New York, 1997–1999, Christie’s East, The Latin American Sale, 23 November 1999, lot 30; acquired by The Hispanic Society of America, 1999. |

| 12. | Another Peribán batea of similar date with conventionalized floral motifs and stylized birds, attributed to Uruapan, is in the collection of the Museo de América, Madrid (inv. no. 06925). |

References

- Codding, M.A. The Decorative Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820: Lacquerwares. In The Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820; Rishel, J.J., Stratton-Pruitt, S., Eds.; Philadelphia Museum of Art: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006; pp. 106–113. Available online: https://archive.org/details/isbn_978-0-87633-250-4_202102/mode/1up (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Codding, M.A. The Lacquer Arts of Latin America. In Made in the Americas: The New World Discovers Asia; Dennis Carr, Ed.; Museum of Fine Arts: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Granda Paz, O. Barniz de Pasto: Una Artesanía De Raices Prehispánicas. Revista Artesanías de América No. 24. 1987, pp. 21–59. Available online: http://documentacion.cidap.gob.ec:8080/handle/cidap/926 (accessed on 6 July 2024).

- Pérez Carrillo, S. La Laca Mexicana: Desarrollo de un Oficio Artesanal en el Virreinato de la Nueva España Durante el Siglo XVIII; Banamex/Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-White, M.C. El Barniz de Pasto: Secretos y Revelaciones; Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Artes y Humanidades: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, R.; Kaplan, E.; Derrick, M. Mopa mopa: Scientific analysis and history of an unusual South American resin used by the Inka and artisans in Pasto, Colombia. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2015, 54, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, F.; Basso, E.; Katz, M. In search of Humboldt’s colors: Materials and techniques of a 17th-century lacquered gourd from Colombia. Herit. Sci. 2020, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L.; Melchar, D.; Strekopytov, S.; Peggie, D.A.; Melchiorre Di Crescenzo, M.; Keneghan, B.; Najorka, J.; Goral, T.; Gor-bout, A.; Clark, B. Identification, characterisation and mapping of calomel as ‘calomel’, a previously undocumented pigment from South America, and its use on a barniz de Pasto cabinet at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Microchem. J. 2018, 143, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña Castrellón, P.E. El Maque o Laca Mexicana: La Preservación de Una Tradición Centenaria; El Colegio de Michoacán: Zamora, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sabau García, M.L. México en el Mundo de las Colecciones de Arte, Nueva España; Grupo Azabache: Mexico City, Mexico, 1994; Volume 1, pp. 170–172, 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Barroco de la Nueva Granada: Colonial Art from Colombia and Ecuador; Kennedy, A., Fajardo de la Rueda, M., Eds.; Americas Society: New York, NY, USA, 1992; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero Lake, R. La visión de un Anticuario; Landucci: Mexico City, Mexico, 1997; pp. 286, 293–294. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, J.d. Memorial que Fray Geronimo Descobar predicador de la orden de Sant Agustin al Real Consejo de Indias de lo que toca a la provincia de Popayan (1582). In Relaciones y Visitas a Los Andes, S XVI; Pinzón, H.T., Ed.; Colcultura/Instituto de Cultura Hispánica: Santafé de Bogotá, Colombia, 1993; Volume 1, p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, P. Noticias historiales de las conquistas de Tierra Firme en las Indias Occidentales; Medardo Rivas: Bogotá, Colombia, 1892; Volume 4, p. 166. Available online: https://archive.org/details/tierrafirmeindias04simbrich/page/166/mode/2up (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Fernández de Piedrahita, L. Historia General de Las Conquistas del Nuevo Reyno de Granada; J.B. Verdussen: Amberes, Belgium, 1688; p. 360, The Dedication is Dated 12 August 1676, at Santa Marta, Colombia, p. [ii]; Available online: https://archive.org/details/historiagenerald00fern_0/page/n7/mode/2up (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Sañudo, J.R. Apuntes Sobre la Historia De Pasto. Segunda Parte, La Colonia En El Siglo XVII; Tipografía de Alejandro Santander, Impresor Elías Villareal: Pasto, Colombia, 1897; p. 104. Available online: https://catalogoenlinea.bibliotecanacional.gov.co/client/es_ES/search/asset/118764 (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Granda Paz, O. Análisis Histórico-Estético del Barniz de Pasto Siglos XV a XIX; Instituto Colombiano de Cultura: San Juan de Pasto, Colombia, 1992; p. 65, Unpublished typescript. Bogotá, Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, 738.12 G71a. [Google Scholar]

- Marín Valencia, A. Carnaval Kamëntsá: Identidad, simbolismo y resistencia. In El entrecruzimiento de la Tradición y la Modernidad: Memorias del Encuentro Internacional sobre Estudios de Fiesta, Nación y Cultura; González Pérez, M., Ed.; Intercultura: Bogotá, Colombia, 2011; pp. 131, 137–138. Available online: https://issuu.com/interculturacolombia/docs/entrecruzamientodelatradicionylamodernidad (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Montoya Guzmán, J.D. Mestizaje y frontera en las tierras del Pacífico del Nuevo Reino de Granada, siglos XVI y XVII. Hist. Crítica 2016, 1, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas Murcia, L.L. Del Pincel al Papel. Fuentes para el Estudio de la Pintura en el Nuevo Reino de Granada (1552–1813); Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, ICANH: Bogotá, Colombia, 2012; pp. 220–222. Available online: https://publicaciones.icanh.gov.co/index.php/picanh/catalog/view/86/89/15 (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Abadía Quintero, C. La Notoria Virtud de un Mérito. Redes Complejas, Poder Eclesiástico y negociación Política en las Indias Meridionales. El Caso del Obispado de Popayán, 1546–1714. Ph.D. Thesis, Colegio de Michoacán, Centro de Estudios Históricos, Zamora, Mexico, 2019; pp. 419, n954, 569–570, n1272. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338775754 (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Silva Ramírez, L.M.; Gutiérrez Avendaño, J. Creer para ver. Instauración del discurso milagroso entre la población del Nuevo Reino de Granada, siglos XVI, XVII y XVIII. Ilu. Rev. Cienc. Relig. 2016, 21, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hecht, J. The Past is Present: Transformation and Persistence of Imported Ornament in Viceregal Peru. In The Colonial Andes: Tapestries and Silverwork, 1530–1830; Phipps, E., Hecht, J., Esteras Martín, C., Eds.; Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, NY, USA, 2004; p. 50. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/The_Colonial_Andes_Tapestries_and_Silverwork_1530_1830 (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Cadenas y López, A.A.d. Elenco de Grandezas Y Títutlos Nobiliarios Españoles, 46th ed.; Ediciones Hidalguía: Madrid, Spain, 2013; p. 599. [Google Scholar]

- Zabía de la Mata, A. El arte del barniz de Pasto en la colección del Museo de América de Madrid. Anales del Museo de América 2020, 28. pp. 85–86, Figure 2 and Figure 4; pp. 88–89, Figure 7; pp. 90–91, Figure 9. Available online: https://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/museodeamerica/dam/jcr:fbf666e8-f20e-481c-96c9-16f9c7e5dc16/06-anales-del-museo-de-america-xxviii-2020-zab-a-81-98.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Zabía de la Mata, A. New Contributions Regarding the Barniz de Pasto Collection at the Museo de América, Madrid. Heritage 2024, 7, 667–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Oca, P. Relación de Tiripitío. In Relaciones Geográficas Del Siglo XVI: Michoacán; Acuña, R., Ed.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 1987; Volume 9, p. 354. [Google Scholar]

- Basalenque, D. Historia de la Provincia de San Nicolas de Tolentino, de Michoacan, Del Orden de n. p. s. Augustin … Año de 1673; Tip. Barbedillo y Comp.: Tlaxcala, Mexico, 1886; Volume 1, pp. 444–445, 450–451. Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433070777846&view=1up&seq=446 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- de Escobar, M. Americana Thebaida: Vitas Patrum de los Religiosos Hermitaños de N. P. San Augustin de la Provincia de S. Nicolas Tolentino de Mechoacan… año 1729; Imprenta Victoria: Tijuana, Mexico, 1924; pp. 26, 147–148. Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000019372242&view=1up&seq=203 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Rea, A. de la. Crónica de la Órden de N. Seráfico, P. S. Francisco, Provincia de San Pedro y San Pablo de Mechoacán en la Nueva España; Imprenta de J.R. Barbedillo: Mexico City, Mexico, 1882; p. 40. Available online: https://babel.Hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.31158005770762&view=1up&seq=60 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Antonio, P. Still Life with an Ebony Chest. 1652. Oil on Canvas, 80 cm × 94 cm. St. Petersburg, Russia, The State Hermitage Museum, ГЭ-327. Available online: https://hermitagemuseum.org/wps/portal/hermitage/digital-collection/01.+paintings/32672 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Katzew, I. (Ed.) Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800: Highlights from LACMA’s Collection ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; DelMonico Books/D.A.P.: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2022; pp. 288–290, notes pp. 356–357. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C.F. Catálogo de Obras Artísticas Mexicanas en Venezuela. Período hispánico; Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-UNAM: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998; p. 233. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39686747/Cat%C3%A1logo_de_obras_art%C3%ADsticas_mexicanas_en_Venezuela_Per%C3%ADodo_hisp%C3%A1nico (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- Alcedo y Bejarano, A. Diccionario geográfico-histórico de las Indias Occidentales o América: Es decir los Reynos del Perú, Nueva España, Tierra-Firme, Chile, y Nuevo Reyno de Granada; Manuel González: Madrid, Spain, 1788; Volume 4, p. 158, Spanish Text: “el vecindario se Compone de 100 Familias de Españoles, Mestizos y Mulatos, y 66 de Indios Tarascos Que fabrican Muchas Xícaras Porque Abunda de Calabacitos, y las Pintan Con Primor de Varios Colores, Formando el Principal Ramo de su Comercio por la Estimación Que Tienen en Todas Partes”; Available online: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ucm.5324318203&view=1up&seq=166 (accessed on 11 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).