Motivations for the Demand for Religious Tourism: The Case of the Pilgrimage of the Virgin of Montserrat in Ecuador

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Religious Tourism

2.2. Motivations in Religious Tourism

3. Methodology

3.1. Context of the Virgin of Montserrat Pilgrimage in Ecuador

3.2. Survey, Data Collection, and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Aspects

4.2. Motivation for Religious Tourism

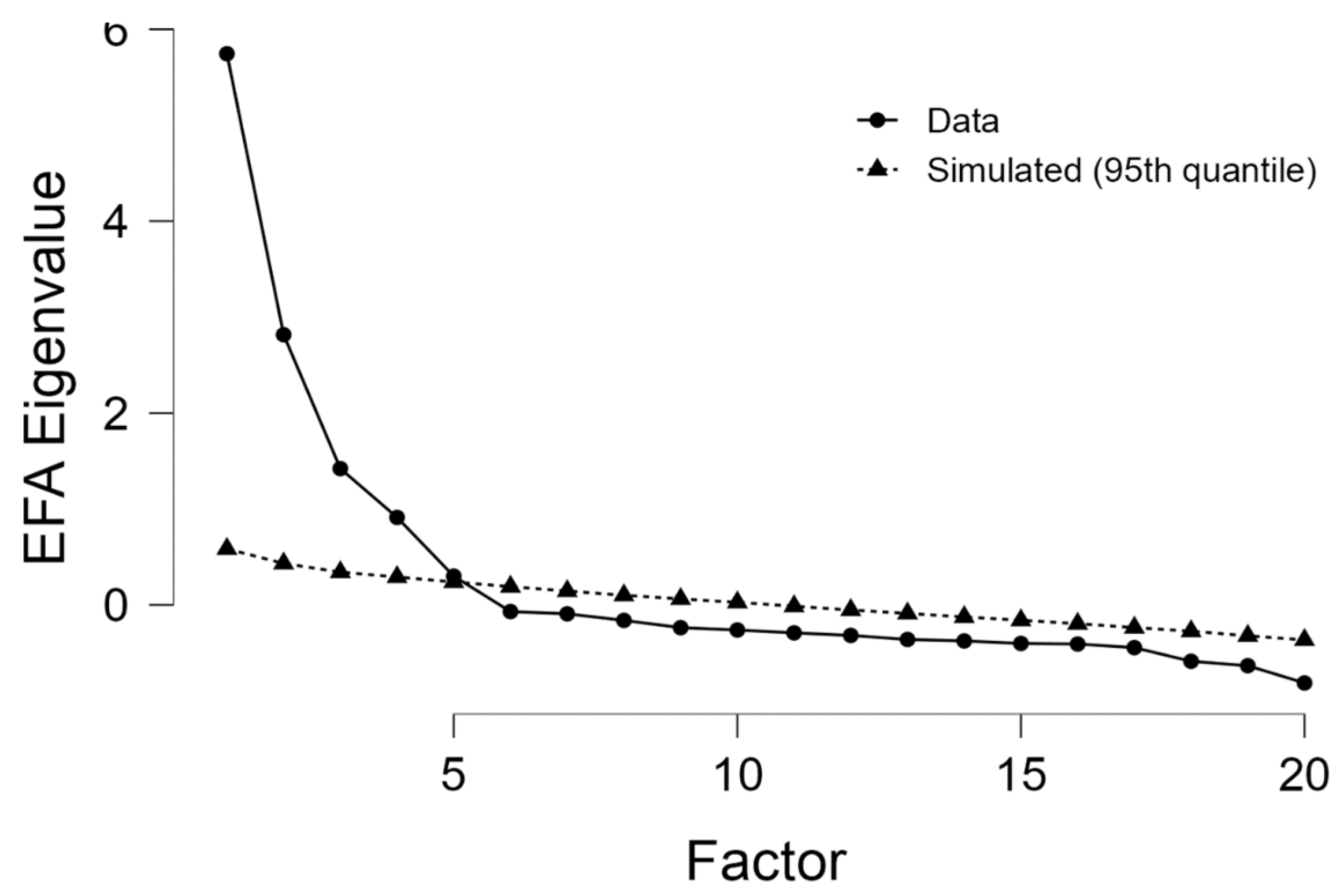

4.3. Construct Validity

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinschede, G. Forms of religious tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; Suntikul, W. Tourism and Religion; Channel View Publication: Bristol, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Kreiner, N. Religion and tourism: A diverse and fragmented field in need of a holistic agenda. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 82, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.; King, B. Religious tourism studies: Evolution, progress, and future prospects. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomljenović, D.J.; Dukić, L. Religious tourism—From a tourism product to an agent of societal transformation. In SITCON 2017—Religious Tourism and the Contemporary Tourism Market; Univerzitet Singidunum: Beograd, Serbia, 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O. Motivations as predictors of religious tourism: The Muslim pilgrimage to the city of Mecca. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hanandeh, A. Quantifying the carbon footprint of religious tourism: The case of Hajj. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimias, A.; Mitev, A.; Michalko, G. Demographic Characteristics Influencing Religious Tourism Behaviour: Evidence form a Central-Eastern-European country. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2016, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutic, J.; Caie, E.; Clegg, A. In search of heterotopia? Motivations of visitors to an English cathedral. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 750–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; White, G.R.T.; Samuel, A. To pray and to play: Post-postmodern pilgrimage at Lourdes. Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.L.; Marrison, A.M.; Rutledge, J.L. Tourism Bridges across Continents; McGraw-Hill: Sydney, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yolal, M.; Rus, R.V.; Cosma, S.; Gursoy, D. A pilot study on spectators’ motivations and their socio-economic perceptions of a film festival. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2015, 16, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayal, G. The personas and motivation of religious tourists and their impact on intentions to visit religious sites in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Tour. 2023, 9, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulet, S.; Vidal, D. Tourism and religion: Sacred spaces as transmitters of heritage values. Church. Commun. Cult. (CC&C) 2018, 3, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Sánchez, A.; Álvarez-García, J.; del Río-Rama, M.; Oliveira, C. Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage: Bibliometric Overview. Religions 2018, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, J.S.; Huang, K. Religious tourist motivation in Buddhist Mountain: The case from China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, J.; Sołjan, I.; Bilska-Wodecka, E. Visitors’ diversified motivations and behavior—The case of the pilgrimage center in Krakow (Poland). J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2018, 16, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najib, M.; Sumardi, R.S.; Nurlaela, S.; Fahma, F. Determinant factors of Muslim Tourist motivation and attitude in Indonesia and Malaysia. GeoJ. Tour. Geosites 2020, 31, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margry, P.J. The Pilgrimage to Jim Morrison’s Grave at Père Lachaise Cemetery: The Social Construction of Sacred Space. In Shrines and Pilgrimage in the Modern World: New Itineraries into the Sacred; Margry, P.J., Ed.; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Iverson, T. Tourism and Islam: Considerations of culture and duty. In Tourism Religion and Spiritual Journeys; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrimage: Roman Catholic Pilgrimage in the New World. Available online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/pilgrimage-roman-catholic-pilgrimage-new-world (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Palka, J.; Folch, R. Pilgrimage in Colonial Latin America. In Latin American Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, M.Á.B.; Meroño, M.C.P. Tourist profiles based on the motivations to travel. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, J.M. Social Psychology of Travel and Tourism; Thomson: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pillai, S.K.B.; Kamat, K.; Scaglione, M.; D’Mello, C.; Weiermair, K. Exposition of St. Francis Xavier’s holy relics in Goa: An importance-performance analysis. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2017, 5, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzidou, M.; Scarles, C.; Saunders, M.N. The complexities of religious tourism motivations: Sacred places, vows and visions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 70, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, C. Israeli education addressing dilemmas caused by pluralism: A sociological perspective. In Education in a Comparative Context; Krausz, E., Ed.; Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1989; Volume 4, pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Božic, S.; Spasojević, B.; Vujičić, M.D.; Stamenkovic, I. Exploring the motives of religious travel by applying the Ahp Method—The case study of Monastery Vujan (Serbia). Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2016, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, T.R.; Gray, L.E.; Dunville, A.M.; Hicks, A.M.; Gilson, E.A. Preference and tranquility for houses of worship. Environ. Behav. 2013, 45, 504–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canoves, G.; Prat, F.J.M. The Determinants of Tourist Satisfaction in Religious Destinations: The case of Montserrat (Spain). Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2016, 4, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L.J.; Annis, J.; Robbins, M.; ap Sion, T.; Williams, E. National heritage and spiritual awareness: A study in psychological type theory among visitors to St Davids Cathedral. In Religious Identity and National Heritage; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 123–147. [Google Scholar]

- Rebenstorf, H.; Körs, A. Die Besucher* innen von Citykirchen: Besuchsverhalten, Erwartungen und Kirchenraumwahrnehmung. dies./Christopher Zarnow/Christoph Sigrist (Hg.). In Citykirchen und Tourismus: Soziologisch-Theologische Studien Zwischen Berlin und Zürich; Evangelische Verlagsanstalt: Leipzig, Germany, 2018; pp. 35–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G.M. Anomie, ego-enhancement and tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1977, 4, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Antunes, A.; Henriques, C. A closer look at Santiago de Compostela’s pilgrims through the lens of motivations. Tour. Manag. 2018, 64, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina Ramírez, R.; Pulido Fernández, M. Religious experiences of travellers visiting the Royal Monastery of Santa María de Guadalupe (Spain). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, C.S.; Di Nuovo, S. Motivation and personality traits for choosing religious tourism. A research on the case of Medjugorje. Curr. Issues Tour. 2013, 16, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robina Ramírez, R.; Fernández Portillo, A. What role does touristś educational motivation play in promoting religious tourism among travellers? Ann. Leis. Res. 2020, 23, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vistad, O.I.; Øian, H.; Williams, D.R.; Stokowski, P. Long-distance hikers and their inner journeys: On motives and pilgrimage to Nidaros, Norway. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2020, 31, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, U.; Lindner, K. Visit Motivation of Tourists in Church Buildings: Amending the Phelan-Bauer-Lewalter Scale for Visit Motivation by a Religious Dimension. Rural. Theol. 2020, 18, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, J. Visitors’ motivations and behaviours at pilgrimage centres: Push and pull perspectives. J. Herit. Tour. 2021, 16, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Segmentation by motivations in religious tourism: A study of the Christ of Miracles Pilgrimage, Peru. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redacción. MONTECRISTI|Procession with the Image of the Virgin of Monserrat Will Be without Pilgrims. Informate Manabí Digital Journalism. 2020. Available online: https://informatemanabi.com/montecristi-procesion-con-imagen-de-la-virgen-de-monserrat-sera-sin-peregrinos (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Tseng, C.H.; Lin, Y.F. Segmentation by recreation experience in island-based tourism: A case study of Taiwan’s Liuqiu Island. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.; Whitney, D. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.; MacKenzie, S.; Lee, J.; Podsakoff, N. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2010, 41, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective (Seventh). Pearson Education. 2010. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/6885/bb9a29e8a5804a71bf5b6e813f2f966269bc.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Hutcheson, G.; Sofroniou, N. The Multivariate Social Scientist: Introductory Statistics Using Generalized Linear Models; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R. Multivariate data analysis 6th Edition. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2006, 87, 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas Cedeño, L.L. Turismo Religioso en Montecristi (Ecuador): Análisis de Turistas y Residentes. 2023. Available online: https://helvia.uco.es/handle/10396/26036 (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Steenkamp, J.; Van Trijp, H. The use of lisrel in validating marketing constructs. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1991, 8, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC). INEC Presents Statistics on Religion for the First Time. 2024. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/inec-presenta-por-primera-vez-estadisticas-sobre-religion/ (accessed on 10 April 2024).

| Author | Year of Publication | Religious Event | Motivations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gutic et al. [9] | 2010 | To visit the Chichester Cathedral in England | Spirituality, architecture, and history |

| Francis L.J. [31] | 2012 | To visit St. David’s Cathedral in Wales | Historical and architectural aspects rather than religious ones |

| Abbate and Di Nuovo [36] | 2013 | To visit the Medjugorje Sanctuary (Bosnia-Herzegovina) | The need for discovery in men and socialization in women. |

| Božic et al. [28] | 2016 | To visit Vujan Monastery in Serbia | Religious and non-religious or secular (architecture, culture, and history) |

| Pillai et al. [25] | 2017 | To visit the exhibition of the holy relics of Saint Francis Xavier in Goa (India) | Religious experience, social exploration, escape, experience of belief, and shopping. |

| Robenstorf and Körs [32] | 2018 | To visit churches in German and Swiss cities | Building’s historical origins, architecture, and atmosphere are more important than religious reasons |

| Liro et al. [17] | 2018 | To visit the Divine Mercy Shrine in Krakow (Poland) | Religious, touristic, and recreational |

| Amaro et al. [34] | 2018 | Pilgrimage to the Camino de Santiago de Compostela | Religious, spiritual, new experiences, cultural, nature and sports, escape from routine, meeting new people and places, and fulfilling the promise |

| Robina and Pulido [35] | 2018 | To visit the Royal Monastery of Guadalupe, Spain. | Religious, cultural, environmental, social, and educational, where a there is a higher percentage of influence from religious, cultural, and environmental motivations at the time of religious tourism |

| Riegel and Linder [39] | 2020 | To visit a church in Germany | Religion, learning and interest, relaxation and recreation, the site’s popularity, social contact, and social learning |

| Robina and Férnandez [37] | 2020 | To visit the Monastery of Guadalupe, Spain | Cultural, educational, environmental, and rural |

| Vistad et al. [38] | 2020 | To visit Trondheim (Norway) | The inner self, the religious self, knowing places and local heritage, slow travel, nature knowledge and joy, exercising in nature, hiking together, and being alone |

| Liro et al. [40] | 2021 | To visit eight of the most famous Roman Catholic shrines in Poland | Religious motivations, tourist motivations, recreation, social and family motivation, and commercial and shopping motivation |

| Carvache-Franco et al. [41] | 2024 | To attend the Christ of Miracles pilgrimage in Lima, Peru | Religious experience, belief experience, escape, touristic experience, and shopping |

| Measurement Items | Loading | Eigenvalue | Variance Explained % | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience Belief | 6.379 | 29.069 | 0.939 | |

| EB1: For religious fulfillment | 0.926 | |||

| EB2: To experience the holy atmosphere | 0.917 | |||

| EB3: To pay respect to the Saint’s relics | 0.905 | |||

| EB4: To redeem me | 0.805 | |||

| EB5: To fulfill a life-long desire | 0.797 | |||

| Experience Religion | 3.471 | 11.618 | 0.905 | |

| ER1: To seek spiritual comfort | 0.923 | |||

| ER2: To experience the mystery of religion | 0.869 | |||

| ER3: To seek peace | 0.838 | |||

| ER4: To experience a different culture | 0.775 | |||

| ER5: To appreciate/experience the grandeur of the church | 0.615 | |||

| Social Exploration | 2.398 | 15.747 | 0.834 | |

| SE1: For a holiday | 0.823 | |||

| SE2: It is a chance to see Montecristi | 0.745 | |||

| SE3: Sightseeing | 0.742 | |||

| SE4: To satisfy my curiosity | 0.664 | |||

| SE5: To accompany friends or family | 0.502 | |||

| Escape | 1.607 | 5.460 | 0.882 | |

| ES1: To relieve daily stress | 0.950 | |||

| ES2: To relieve boredom | 0.841 | |||

| ES3: To escape from routine life | 0.752 | |||

| Shopping | 1.101 | 5.067 | 0.829 | |

| SH1: To purchase local products | 0.866 | |||

| SH2: To purchase religious items | 0.784 |

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Indicator | Symbol | Estimate | Std. Error | z-Value | p | Lower | Upper | Std. Est. (all) |

| Experience Belief | EB1 | λ11 | 1.341 | 0.051 | 26.283 | <0.001 | 1.241 | 1.441 | 0.875 |

| EB2 | λ12 | 1.301 | 0.048 | 27.221 | <0.001 | 1.208 | 1.395 | 0.911 | |

| EB3 | λ13 | 1.276 | 0.053 | 24.265 | <0.001 | 1.173 | 1.379 | 0.875 | |

| EB4 | λ14 | 1.267 | 0.049 | 25.741 | <0.001 | 1.171 | 1.364 | 0.846 | |

| EB5 | λ15 | 1.274 | 0.048 | 26.273 | <0.001 | 1.179 | 1.369 | 0.843 | |

| Experience Religion | ER1 | λ21 | 1.257 | 0.057 | 21.956 | <0.001 | 1.145 | 1.369 | 0.855 |

| ER2 | λ22 | 1.296 | 0.049 | 26.569 | <0.001 | 1.201 | 1.392 | 0.883 | |

| ER3 | λ23 | 1.047 | 0.072 | 14.604 | <0.001 | 0.906 | 1.187 | 0.766 | |

| ER4 | λ24 | 1.159 | 0.067 | 17.276 | <0.001 | 1.027 | 1.290 | 0.802 | |

| ER5 | λ25 | 0.981 | 0.076 | 12.850 | <0.001 | 0.832 | 1.131 | 0.744 | |

| Social Exploration | SE1 | λ31 | 1.104 | 0.061 | 18.239 | <0.001 | 0.985 | 1.222 | 0.753 |

| SE2 | λ32 | 1.132 | 0.067 | 16.853 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.263 | 0.793 | |

| SE3 | λ33 | 0.828 | 0.075 | 11.042 | <0.001 | 0.681 | 0.975 | 0.663 | |

| SE4 | λ34 | 0.951 | 0.076 | 12.511 | <0.001 | 0.802 | 1.100 | 0.658 | |

| SE5 | λ35 | 0.895 | 0.076 | 11.818 | <0.001 | 0.746 | 1.043 | 0.678 | |

| Escape | ES1 | λ41 | 0.735 | 0.053 | 13.831 | <0.001 | 0.631 | 0.839 | 0.956 |

| ES2 | λ42 | 0.647 | 0.059 | 10.912 | <0.001 | 0.531 | 0.763 | 0.835 | |

| ES3 | λ43 | 0.542 | 0.067 | 8.075 | <0.001 | 0.411 | 0.674 | 0.749 | |

| Shopping | SH1 | λ51 | 1.007 | 0.070 | 14.436 | <0.001 | 0.870 | 1.144 | 0.791 |

| SH2 | λ52 | 1.098 | 0.068 | 16.159 | <0.001 | 0.965 | 1.231 | 0.896 | |

| Index | Value |

|---|---|

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.960 |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.953 |

| Bentler–Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.953 |

| Bentler–Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.922 |

| Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) | 0.776 |

| Bollen’s Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.907 |

| Bollen’s Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.960 |

| Relative Non-centrality Index (RNI) | 0.960 |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.056 |

| PClose | 0.133 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.043 |

| Factor | CR | AVE | α | MSV | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience Belief | 0.940 | 0.758 | 0.940 | 0.318 | 0.871 | ||||

| 2. Experience Religion | 0.906 | 0.659 | 0.896 | 0.359 | 0.322 *** | 0.812 | |||

| 3. Social Exploration | 0.836 | 0.506 | 0.847 | 0.359 | 0.261 *** | 0.600 *** | 0.711 | ||

| 4. Escape | 0.886 | 0.724 | 0.887 | 0.012 | −0.048 | -0.109 † | −0.097 | 0.851 | |

| 5. Shopping | 0.833 | 0.715 | 0.771 | 0.318 | 0.564 *** | 0.117 † | 0.117 † | 0.002 | 0.845 |

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Experience Belief | |||||

| 2. Experience Religion | 0.918 | ||||

| 3. Social Exploration | 0.637 | 0.695 | |||

| 4. Escape | 0.529 | 0.583 | 0.863 | ||

| 5. Shopping | 0.788 | 0.746 | 0.754 | 0.594 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Andrade-Alcivar, L.; Cedeño-Zavala, B. Motivations for the Demand for Religious Tourism: The Case of the Pilgrimage of the Virgin of Montserrat in Ecuador. Heritage 2024, 7, 3719-3733. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070176

Carvache-Franco M, Carvache-Franco W, Orden-Mejía M, Carvache-Franco O, Andrade-Alcivar L, Cedeño-Zavala B. Motivations for the Demand for Religious Tourism: The Case of the Pilgrimage of the Virgin of Montserrat in Ecuador. Heritage. 2024; 7(7):3719-3733. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070176

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarvache-Franco, Mauricio, Wilmer Carvache-Franco, Miguel Orden-Mejía, Orly Carvache-Franco, Luis Andrade-Alcivar, and Brigette Cedeño-Zavala. 2024. "Motivations for the Demand for Religious Tourism: The Case of the Pilgrimage of the Virgin of Montserrat in Ecuador" Heritage 7, no. 7: 3719-3733. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070176

APA StyleCarvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Orden-Mejía, M., Carvache-Franco, O., Andrade-Alcivar, L., & Cedeño-Zavala, B. (2024). Motivations for the Demand for Religious Tourism: The Case of the Pilgrimage of the Virgin of Montserrat in Ecuador. Heritage, 7(7), 3719-3733. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7070176