Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition of Cultural Routes

1.2. Cultural Tourism and Heritage Sites

1.3. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products

2. Methodology

2.1. Selection of Studies to Be Included

2.2. Analysis and Classification of Cultural Route Cases

2.3. Summarizing and Evaluation of Tools for Cultural Tourism

3. Distribution and Classification of Cultural Route Products

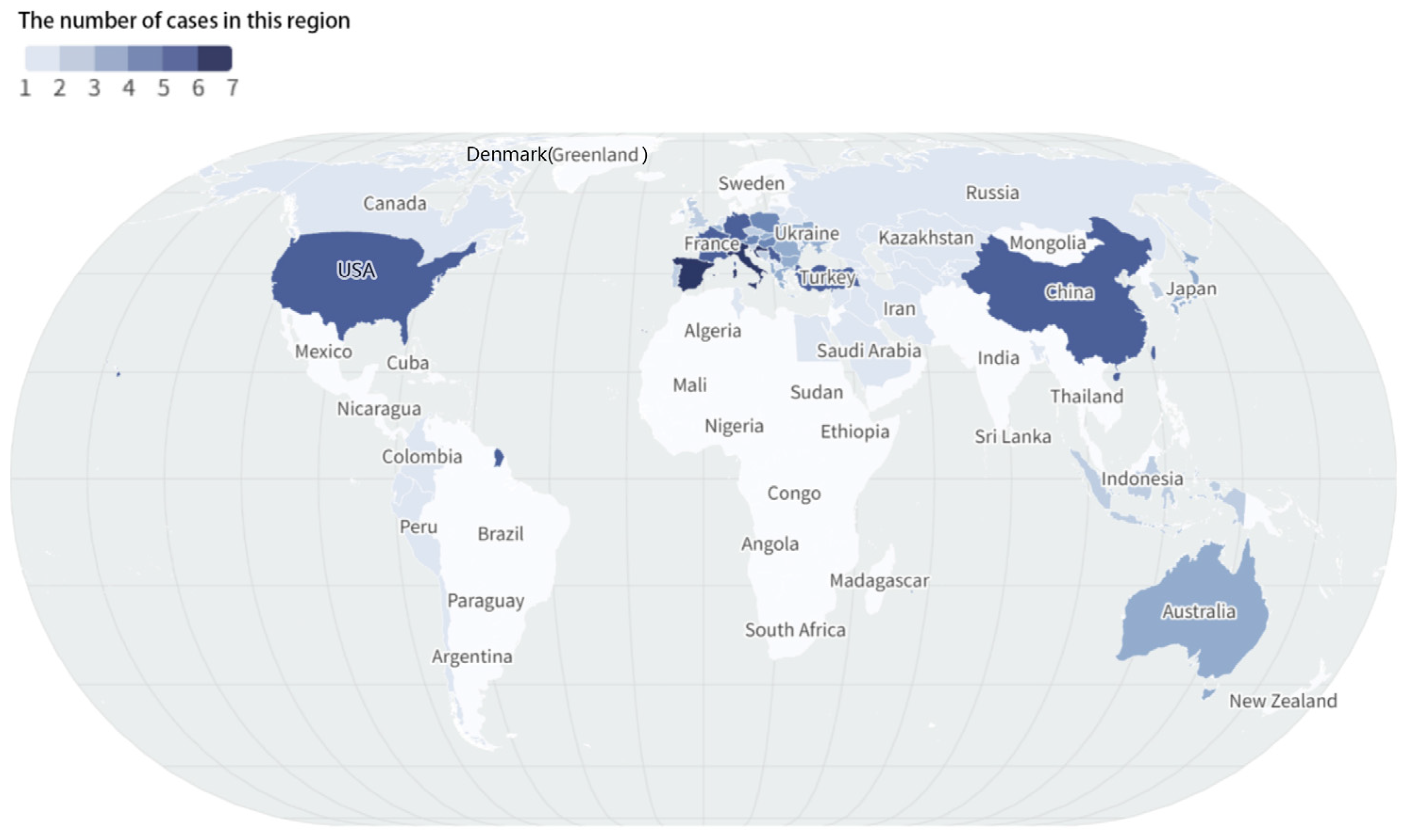

3.1. Case Distribution

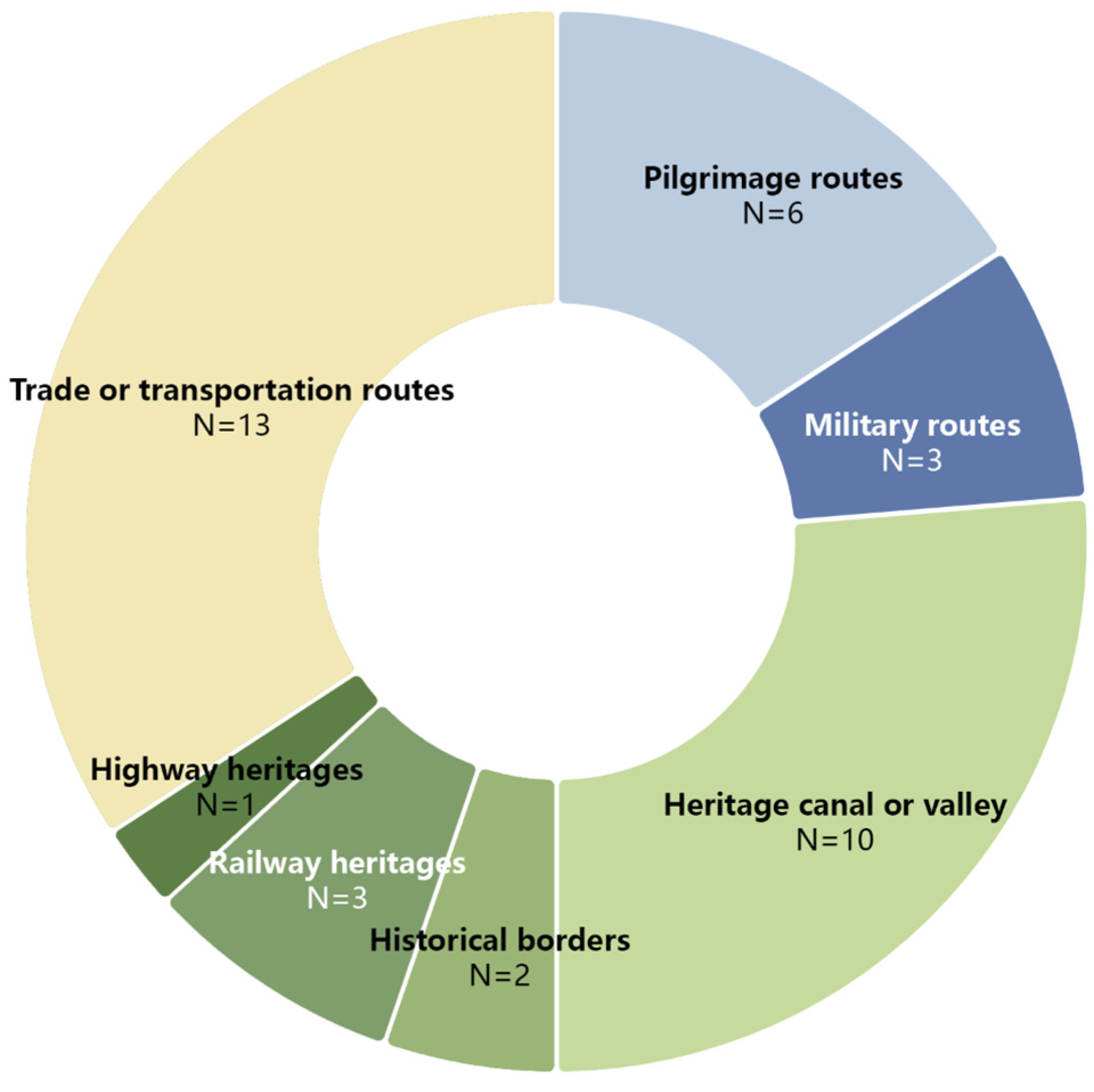

3.2. Case Classification

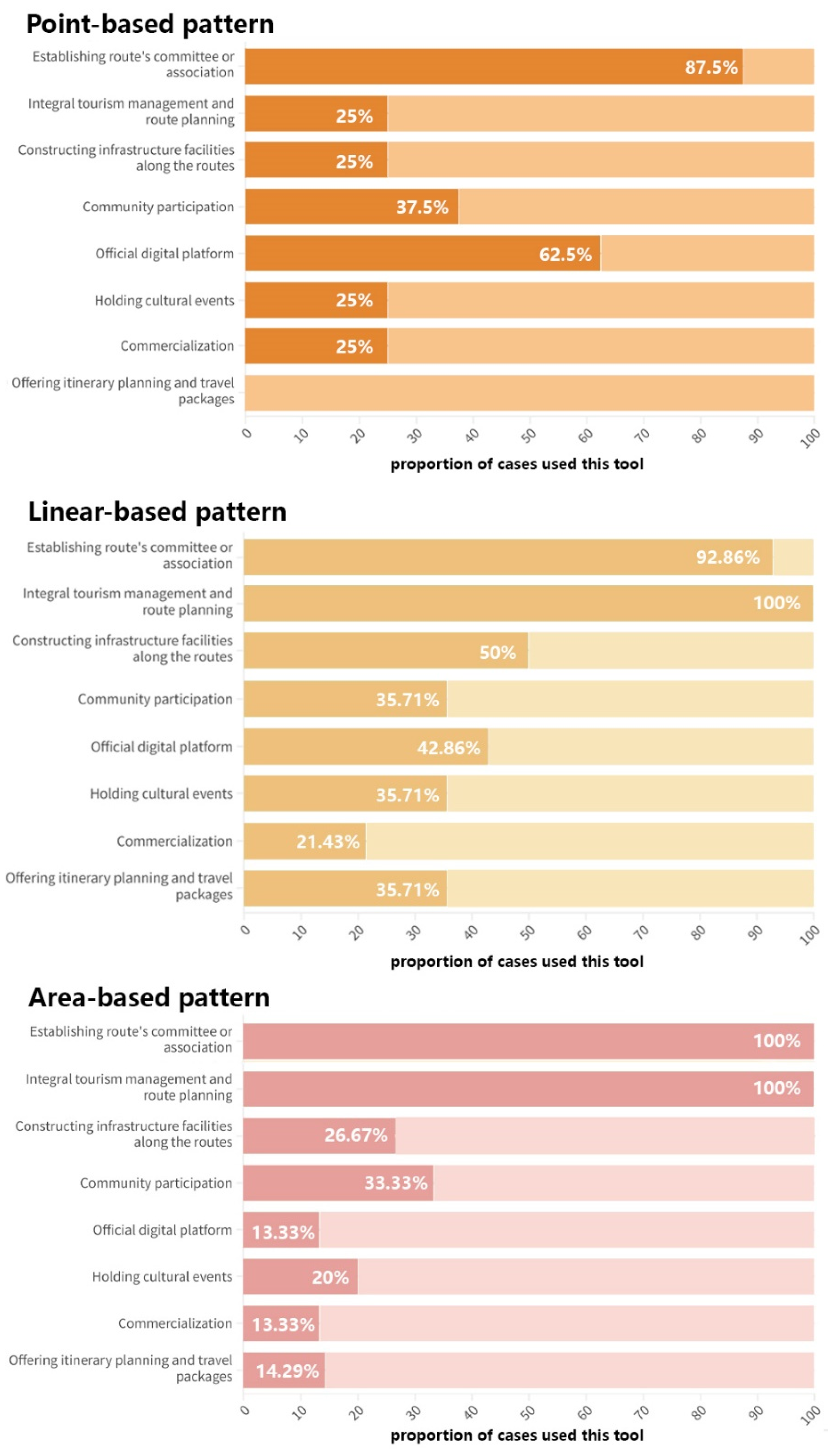

4. Planning Patterns for Route Tourism

4.1. Point-Based Pattern

4.2. Linear-Based Pattern

4.3. Area-Based Pattern

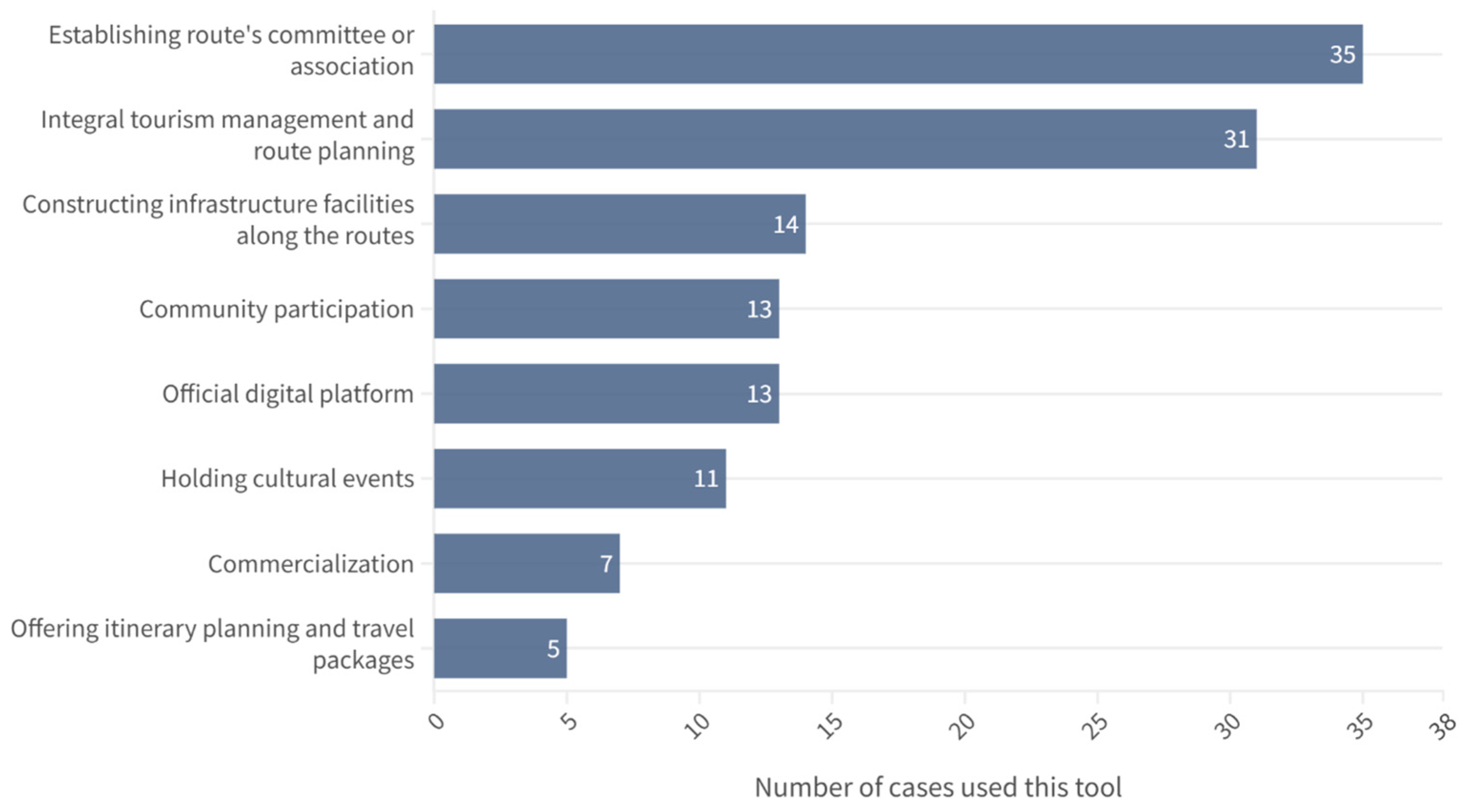

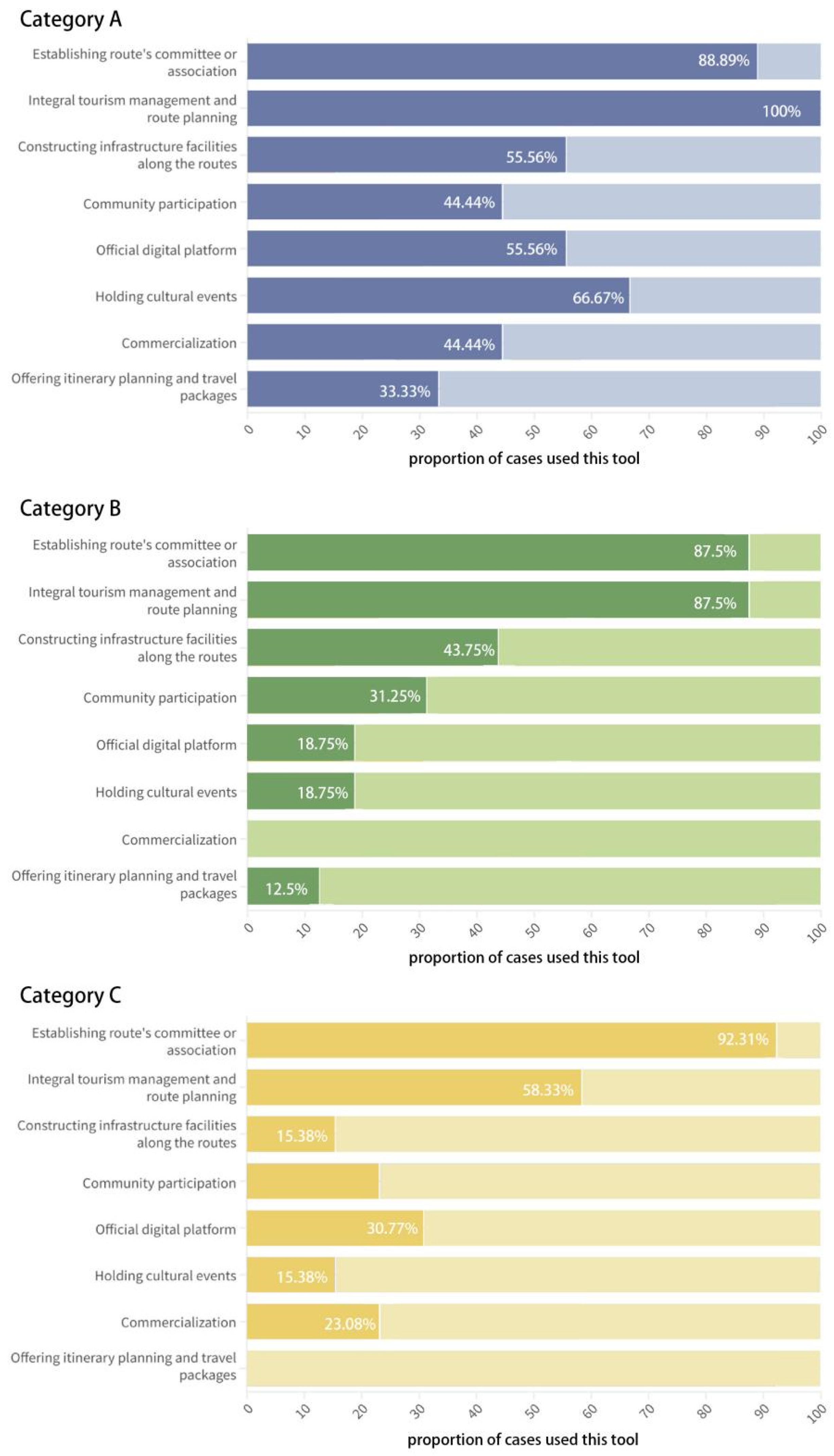

5. Tools of Cultural Tourism for Regional Conservation and Development

5.1. The Summary of Tools

5.2. The Evaluation of Tools

5.2.1. Establishing Route Committees or Associations

5.2.2. Integral Tourism Management and Route Planning

5.2.3. Constructing Infrastructure Facilities along the Routes

5.2.4. Community Participation

5.2.5. Establishing an Official Digital Platform

5.2.6. Holding Cultural Events

5.2.7. Commercialization

5.2.8. Offering Itinerary Planning and Travel Programs

6. Discussion

6.1. How Cultural Routes, as Cultural Tourism Products, Can Contribute to Heritage Conservation and Regional Development

6.2. How to Promote the Planning and Management of Cultural Routes

- (1)

- To establish a comprehensive planning and management framework. This should include detailed planning from the regional to the local level, ensuring that the needs and expectations of all relevant stakeholders are taken into account.

- (2)

- To implement performance assessment tools to integrate goals related to specific interests of heritage conservation, local aesthetics, recreational activities, and various stakeholders. Such tools should enable effective assessment at different stages of tourism development to help balance the preservation and use of cultural heritage while avoiding the secularization of the symbolic meaning of cultural routes.

- (3)

- To select the appropriate planning pattern. Depending on the specific content and function of the cultural route, point-, linear-, or area-based planning patterns can be selected. These patterns should be flexibly adapted to the characteristics of cultural routes and the needs of tourists.

- (4)

- To establish route committees or associations for daily management and strategy development. They can be responsible for building the necessary transport and arts infrastructure, organizing regular cultural events, or creating and updating tourist information platforms.

- (5)

- To encourage communities along the route to be involved in tourism development and route planning from the ground up. This strategy not only helps to enhance the sense of participation and belonging of community members but also promotes the conservation and rational use of cultural heritage.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Name | Country | Types | Planning Patterns | Tools | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Via Regia | France, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, Belarus | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Official digital platform | [2,53,77] |

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 2 | Rideau Canal | Canada | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [39,75] |

| Community participation | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| 3 | The Danube region | Germany, Austria, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova, Serbia, Croatia | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Community participation | [37,47,78,79] |

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

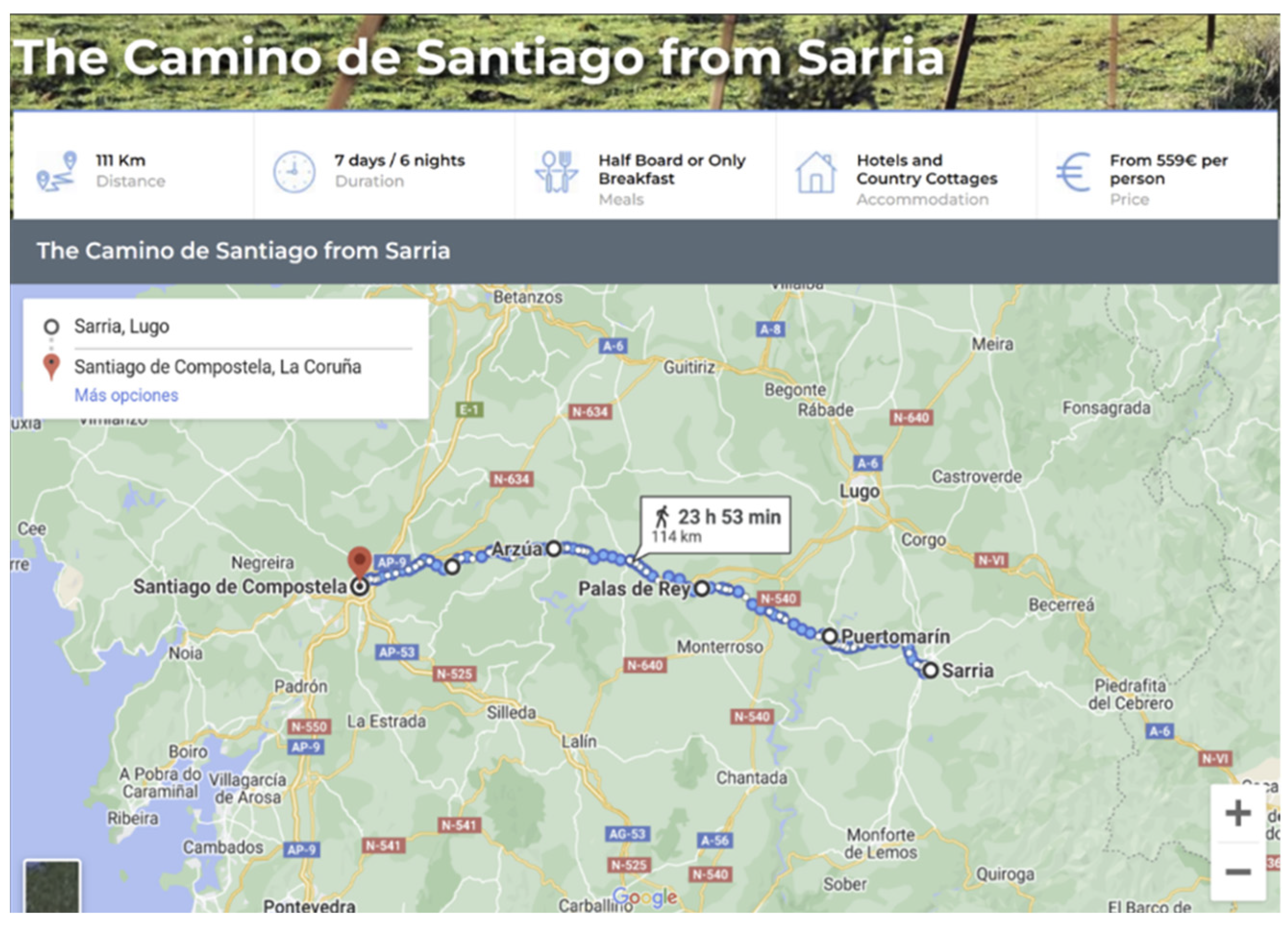

| 4 | The Way of St. James (the Camino de Santiago) | Spain, France, Portugal | Pilgrimage route | Linear-based planning | Commercialization | [38,51,53,66,80,81,82] |

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

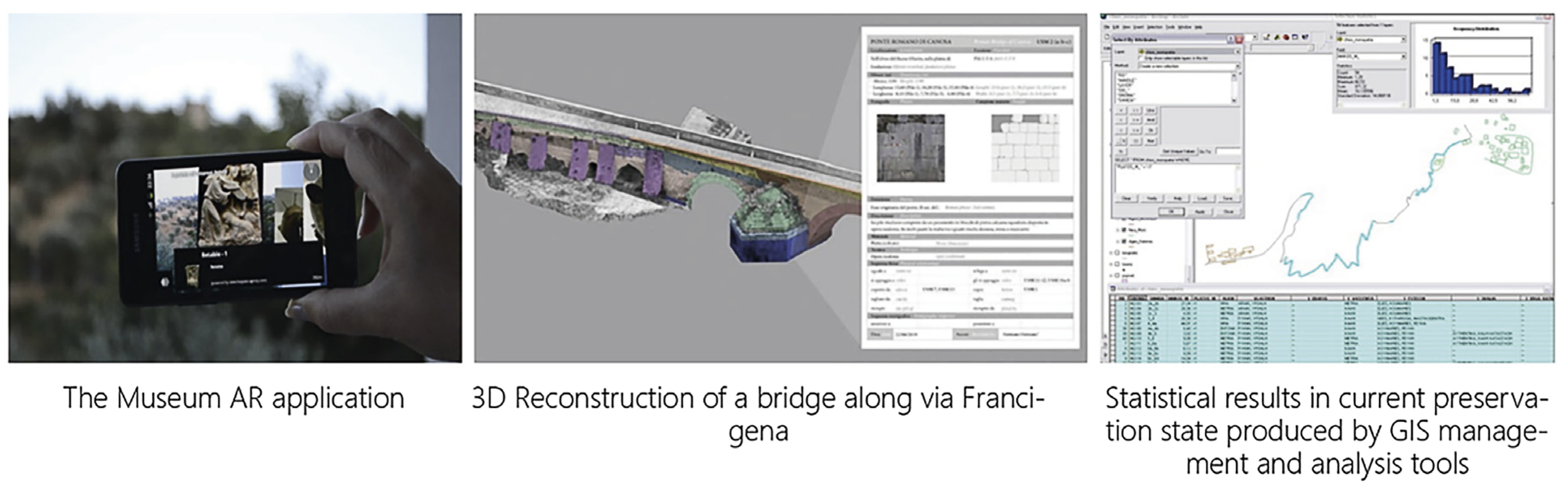

| 5 | Via Francigena | England, France, Switzerland, Italy | Pilgrimage route | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [31,45,55,56,83,84] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Commercialization | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| 6 | The Phoenician Way | Albania, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, Malta, Spain, Tunisia, Slovenia, Ukraine | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Establishing route committees or associations | [3,85,86,87] |

| Community participation | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| 7 | The Qhapaq Ñan | Peru, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Establishing route committees or associations | [48,49,73,88] |

| Community participation | ||||||

| Commercialization | ||||||

| 8 | Saint Martin of Tours Route | Austria, Belgium, Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Slovak, Slovenia, Poland | Pilgrimage route | Point-based planning | Establishing route committees or associations | [46] |

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Commercialization | ||||||

| 9 | Iron Curtain Trail | Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Lithuania, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Turkey | Historical borders | Linear-based planning | Official digital platform | [59] |

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| 10 | Via Romea Germanica | Germany, Italy, Austria | Pilgrimage route | Linear-based planning | Official digital platform | [59] |

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| 11 | Ibar Valley | Serbia | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Holding cultural events | [61] |

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 12 | The Path of Peace | Italy | Military route | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [62] |

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Commercialization | ||||||

| 13 | Great Ocean Road | Australia | Military route | Linear-based planning | Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | [57] |

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 14 | Batik Cultural Route | Indonesia | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Official digital platform | [68] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 15 | St. Paul Trail | Turkey | Pilgrimage route | Linear-based planning | Official digital platform | [89] |

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 16 | The Lycian Way | Turkey | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [89] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 17 | Tamsui–Kavalan trails | China (Taiwan) | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [50] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| 18 | The Phrygian Way | Turkey | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [74] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Commercialization | ||||||

| 19 | The Kumano Kodo Route | Japan | Pilgrimage route | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [23] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| 20 | Oscypek Trail | Poland | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [40] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 21 | Roman Emperors and Danube Wine Route | Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Montenegro, north Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [44,72] |

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| Commercialization | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 22 | The Great Wall in the Ming Dynasty | China | Historical borders | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [54,90] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 23 | The Illinois and Michigan Canal | USA | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [41,76] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| 24 | The Grand Canal | China | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [52,58,91] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 25 | Meiguan Historical Trail | China | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [92] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 26 | Cane River | USA | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Community participation | [35,36] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

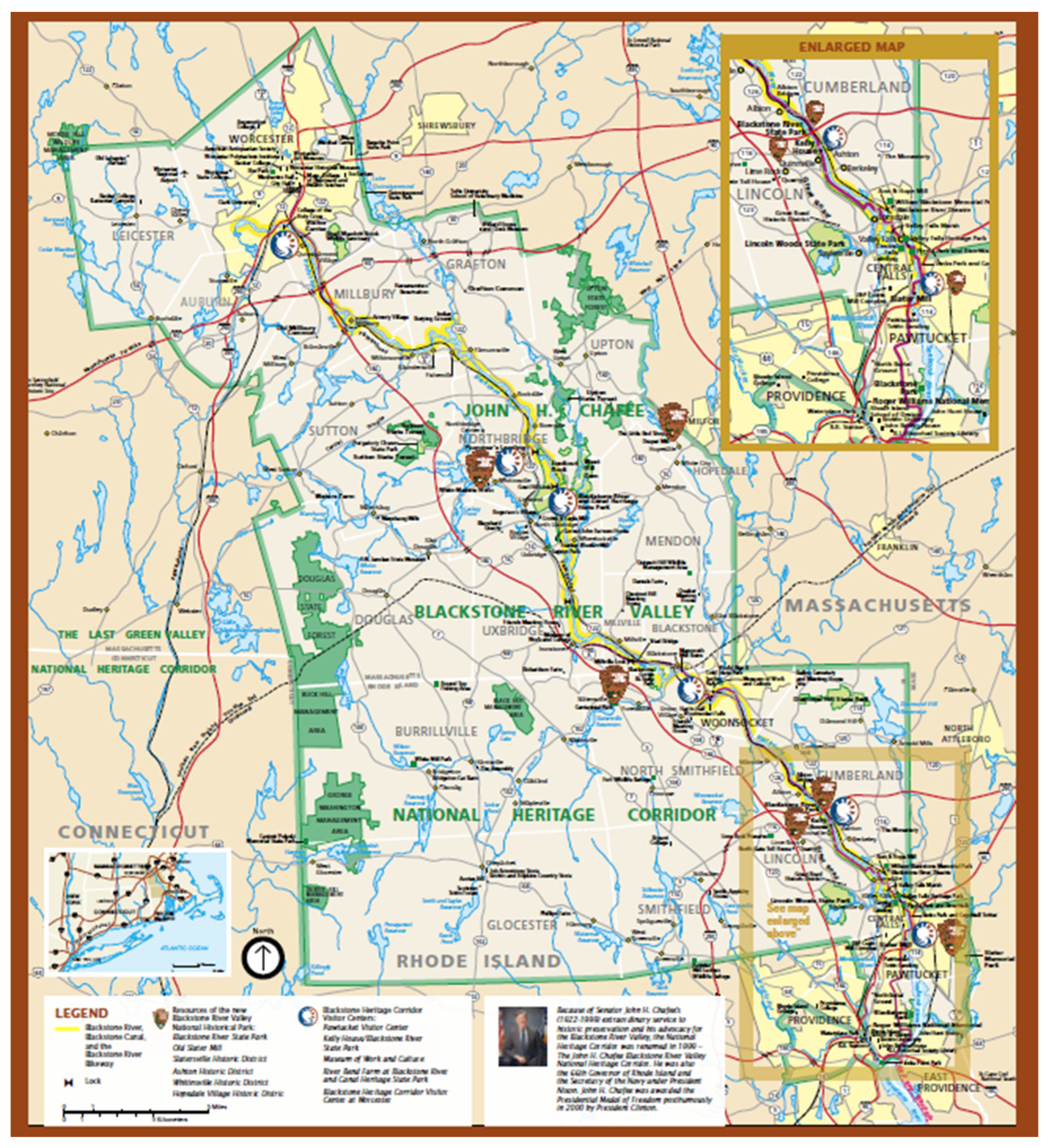

| 27 | Blackstone River Valley | USA | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [35,36] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 28 | Delaware and Lehigh National Heritage Corridor | USA | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based development | Integral tourism management and route planning | [35,36] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| 29 | The Piast Trail | Poland | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Area-based planning | Establishing route committees or associations | [42] |

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| 30 | The Underground Military Galleries of the Petrovaradin Fortress | Serbia | Military route | Area-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [43] |

| Construction of infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

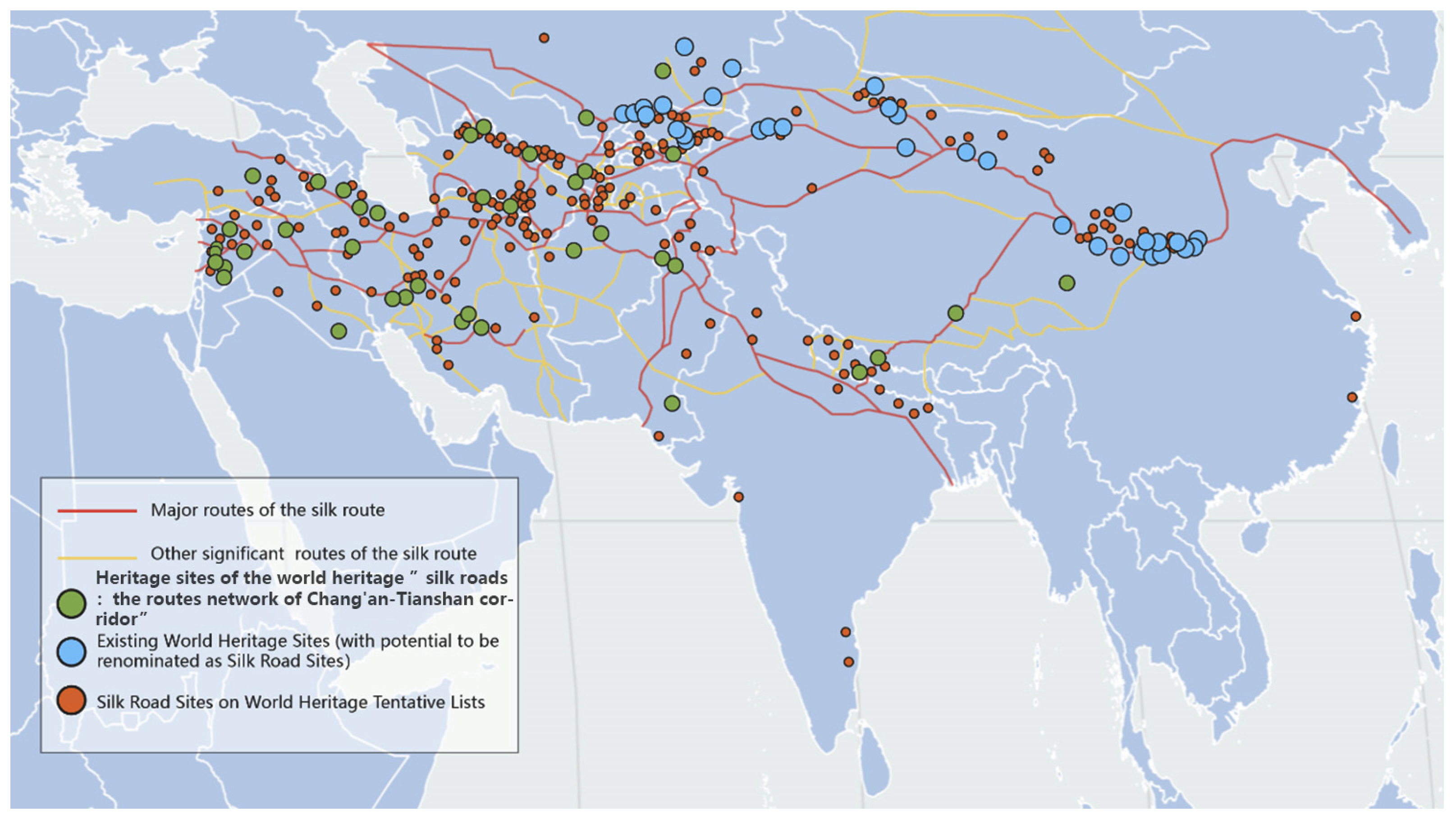

| 31 | The Silk Road | Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Korea, Egypt, Georgia, Greece, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Pakistan, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russia, San Marino, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Establishing route committees or associations | [25,26,27] |

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| 32 | Erie Canal | USA | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | [64,93] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| 33 | Chishui River | China | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | Point-based planning | Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | [60] |

| 34 | Canal du Midi | France | Heritage canal or valley | Area-based planning | Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | [53,94] |

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Integral tourism management and route planning | ||||||

| 35 | Cyprus Government Railways | Cyprus | Railway heritage | Point-based planning | Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | [65] |

| 36 | Puffing Billy | Austria | Railway heritage | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [63] |

| Establishing route committees or associations | ||||||

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | ||||||

| Community participation | ||||||

| Holding cultural events | ||||||

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| 37 | Kuranda Train | Austria | Railway heritage | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [63] |

| Community participation | ||||||

| Official digital platform | ||||||

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | ||||||

| 38 | Route 66 | USA | Highway heritage | Linear-based planning | Integral tourism management and route planning | [95] |

| Establishing route committees or associations |

References

- Dayoub, B.; Yang, P.; Dayoub, A.; Omran, S.; Li, H. The role of cultural routes in sustainable tourism development: A case study of Syria’s spiritual route. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khovanova-Rubicondo, K. Cultural routes as a source for new kind of tourism development: Evidence from the council of Europe’s Programme. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2012, 1, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, W. Cultural routes: An innovation tool for creative tourism. In Proceedings of the Management International Conference-MIC, Sousse, Tunisia, 25–28 November 2009; pp. 1841–1854. [Google Scholar]

- Srichandan, S.; Pasupuleti, R.S.; Mishra, A.J. The transhumance route of Pithoragarh: A cultural route? Environ. Chall. 2021, 5, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter on Cultural Routes. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/culturalroutes_e.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Shishmanova, M.V. Cultural tourism in cultural corridors, itineraries, areas and cores networked. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, D.H.; Trono, A.; Fidgeon, P.R. Pilgrimage trails and routes: The journey from the past to the present. In Religious Pilgrimage Routes and Trails: Sustainable Development and Management; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. Concepts, Definitions, and Classifications for Tourism Statistics; Technical Manual No. 1-Concepts, définitions et classifications des statistiques du tourisme (Version française); World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WTO. WTO Definitions of Tourism; WTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.; Braga, J.L.; Mota, C.; Brás, S.; Leite, S. The impact of the culture–heritage relationship for tourism and sustainable development. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems: Selected Papers from ICOTTS 2021; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 411–425. Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J. Contemporary cultural heritage and tourism: Development issues and emerging trends. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urošević, N. Cultural identity and cultural tourism: Between the local and the global (a case study of Pula, Croatia). Singidunum J. Appl. Sci. 2012, 9, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-D. Cultural events and cultural tourism development: Lessons from the European Capitals of Culture. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 498–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virginija, J. Interaction between cultural/creative tourism and tourism/cultural heritage industries. In Tourism from Empirical Research towards Practical Application; InTech: Rijeka, Crotia, 2016; pp. 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, S.; Tomić, N. Developing the cultural route evaluation model (CREM) and its application on the Trail of Roman Emperors, Serbia. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 17, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Resolution CM/Res(2010)53. In Proceedings of the Enlarged Partial Agreement on Cultural Routes (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers at Its 1101st Meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies). Available online: https://www.cultura.gob.es/dam/jcr:676626cf-af41-4904-a04d-6725b1e4fa2b/resolution-cm-2010-53itinerarios-en.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Durusoy, E. Chapter 2: Cultural Route Concepts, Their Planning and Management Principles în: From an Ancient Road to a Cultural Route: Conservation and Management of the Road between Milas and Labraunda. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karataş, E. The Role of Cultural Route Planning in Cultural Heritage Conservation the Case of Central Lycia. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore, J.N. Cultural Routes and US Preservation Policy. Master’s Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaro, G.; Pistocchi, F. Linking destinations through sustainable cultural routes. Symphonya. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2016, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrisever, C. As an alternative: Cultural routes education for tourism guides–a model suggestion from Turkey. In Cases on Tour Guide Practices for Alternative Tourism; Canan Tanrisever: Kastamonu, Turkey, 2020; pp. 217–239. [Google Scholar]

- Timothy, D.J.; Boyd, S.W. Tourism and Trails: Cultural, Ecological and Management Issues; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2015; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Moira, P.; Mylonopoulos, D.; Konstantinou, G. Tourists, Pilgrims and Cultural Routes: The Case of the Kumano Kodo Route in Japan. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2021, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, D.J. Cultural routes: Tourist destinations and tools for development. In Religious Pilgrimage Routes and Trails: Sustainable Development and Management; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriadis, M.; Shen, S. The contribution of partnership and branding to destination management in a globalized context: The case of the UNWTO Silk Road Programme. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2017, 3, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, M.; Popesku, J. Cultural routes as innovative tourism products and possibilities of their development. Int. J. Cult. Digit. Tour. 2016, 3, 24–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zeng, S.; Na, W.; Yang, H.; Huang, J.; Tan, X.; Sun, Z. Design and Research of Service Platform for Protection and Dissemination of Cultural Heritage Resources of The Silk Road in the Territory of China. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 2, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. A Concept for the Serial Nomination of the Silk Roads in Central Asia and China to the World Heritage List (Updated Text after the Consultation Meeting in Xi’an (China), June 2008). Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/document/9882 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Winter, T. The geocultural heritage of the Silk Roads. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 27, 700–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. The Silk Roads: An ICOMOS Thematic Study; ICOMOS, Charenton-le-Pont, France 2014.

- Lucarno, G. The Camino de Santiago de Compostela (Spain) and The Via Francigena (Italy): A comparison between two important historic pilgrimage routes in Europe. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2016, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Medina, J. Cultural tourism and urban management in northwestern Spain: The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. Tour. Geogr. 2003, 5, 446–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lois González, R. The Camino de Santiago and its contemporary renewal: Pilgrims, tourists and territorial identities. Cult. Relig. 2013, 14, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Sarman, A.M.; bin Mohamad, M.I.; Wei, G.M. Study on Construction of Corridor for Conservation of Port Heritage under Interdiciplinary Perspective. Res. Mil. 2023, 13, 1842–1865. [Google Scholar]

- Laven, D.; Ventriss, C.; Manning, R.; Mitchell, N. Evaluating US national heritage areas: Theory, methods, and application. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laven, D.N.; Krymkowski, D.H.; Ventriss, C.L.; Manning, R.E.; Mitchell, N.J. From partnerships to networks: New approaches for measuring US National Heritage Area effectiveness. Eval. Rev. 2010, 34, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Jovičić, A.; Simeunović-Bajić, N. Community role in heritage management and sustainable tourism development: Case study of the Danube region in Serbia. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. Special Issue 2014, 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lois González, R.C.; Castro Fernández, B.M.; Lopez, L. From sacred place to monumental space: Mobility along the way to St. James. Mobilities 2016, 11, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, H.M. Sustainable heritage tourism marketing and Canada’s Rideau Canal world heritage site. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Kamińska, N. The Role of Cultural Oscypek Trail in the Protection of Polish and European Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 6th UNESCO UNITWIN Conference 2019, Leuven, Belgium, 8–12 April 2019. Institute of Contemporary Culture, University of Lodz (POLAND), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Conzen, M.P.; Wulfestieg, B.M. Metropolitan Chicago’s Regional Cultural Park: Assessing the Development of the Illinois & Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor. J. Geogr. 2008, 100, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacz-Wojtanowska, E.; Góral, A.; Bugdol, M. The role of trust in sustainable heritage management networks. case study of selected cultural routes in Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, T.; Pivac, T.; Cimbaljević, M.; Đerčan, B.; Bubalo Živković, M.; Besermenji, S.; Penjišević, I.; Golić, R. Sustainability of Underground Heritage; The Example of the Military Galleries of the Petrovaradin Fortress in Novi Sad, Serbia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petković, G.; Werner, M.; Pindžo, R. Traveling experience: Roman emperors and Danube wine route. Ekon. Preduzeća 2019, 67, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trono, A.; Castronuovo, V. The Via Francigena del Sud: The value of pilgrimage routes in the development of inland areas. The state of the art of two emblematic cases. Rev. Galega De Econ. 2021, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afferni, R.; Ferrario, C. Sustainable and quality tourism along Saint Martin of Tours route in the rural area of Pavia. In The European Pilgrimage Routes for Promoting Sustainable and Quality Tourism in Rural Areas; Florence University Press: Florence, Italy, 2015; pp. 901–916. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, A.; Woller, R. Preservation, Sustainable Use and Revitalisation of the Roman Heritage along the Danube–the EU Interreg DTP Project “Living Danube Limes”. Építés-Építészettudomány 2021, 49, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kania, M. Qhapaq Ñan: Indigenous peoples’ heritage as an instrument of Inter-American integration policy. Anu. Latinoam. 2019, 7, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, E. Heritage routes and multiple narratives. The Inca Road System (Qhapaq Ñan, Camino principal andino/Andean road system): A specific case of a non-tourism heritage route? Via. Tour. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-C. Across the Administrative Boundaries—The First Mile of the Long-Distance Trail Collaboration in Taiwan. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 19, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, B.M.C.; González, R.C.L.; Lopez, L. Historic city, tourism performance and development: The balance of social behaviours in the city of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Tour. Hosp. Res. 2016, 16, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Dai, D.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Chen, X. Discussion and Reflection on Several Core Issues in the Grand Canal Heritage Conservation Planning Under the Background of Application for World Heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 40, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso Hortelano Mínguez, L.; Mansvelt Beck, J. Is heritage tourism a panacea for rural decline? A comparative study of the Camino de Santiago and the Canal de Castilla in Spain. J. Herit. Tour. 2023, 18, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Tan, L.; Zhou, J. Distribution and integration of military settlements’ cultural heritage in the large pass city of the Great Wall in the Ming Dynasty: A case study of Juyong Pass defense area. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trono, A.; Ruppi, F.; Mitrotti, F.; Cortese, S. The via Francigena Salentina as an opportunity for experiential tourism and a territorial enhancement tool. Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2017, 8, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splendiani, S.; Forlani, F.; Picciotti, A.; Presenza, A. Social Innovation Project and Tourism Lifestyle Entrepreneurship to Revitalize the Marginal Areas. The Case of the via Francigena Cultural Route. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2022, 20, 938–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenburg, K.; James, L. The Great Ocean road, Victoria: A case study for inclusion in the National Heritage List. Hist. Environ. 2013, 25, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Y.; Ding, Y. Observation & Protection Stations-Network of Grand Canal: A Case of the Involvement of Communities Along Cultural Routes. In Proceedings of the 16th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium: ‘Finding the Spirit of Place–between the Tangible and the Intangible, Quebec, QC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, D. The experience of common European heritage: A critical discourse analysis of tourism practices at Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe. J. Eur. Landsc. 2022, 3, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zheng, X. A cultural route perspective on rural revitalization of traditional villages: A case study from Chishui, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Bjeljac, Ž.; Jovičić, A.; Penjišević, I. Cultural Route and Ecomuseum Concepts as a Synergy of Nature, Heritage and Community Oriented Sustainable Development Ecomuseum „Ibar Valley “in Serbia. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Irimiás, A. The Great War heritage site management in Trentino, northern Italy. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, A.; Pryce, J.; Chaiechi, T. Industrial railway heritage trains: The evolution of a heritage tourism genre and its attributes. J. Herit. Tour. 2014, 9, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burd, C. A New, Historic Canal. IA J. Soc. Ind. Archeol. 2016, 42, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Günçe, K.; Misirlisoy, D. Railway heritage as a cultural tourism resource: Proposals for Cyprus government railways. In Proceedings of the 6th UNESCO UNITWIN Conference 2019, Leuven, Belgium, 8–12 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lois-González, R.C.; Somoza-Medina, X. The Necessary Digital Update of the Camino de Santiago. In Proceedings of the International Symposium: New Metropolitan Perspectives, Reggio Calabria, Italy, 24–26 May 2022; pp. 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Martorell Carreño, A. The Transmision of the Spirit of the Place in the Living Cultural Routes: The Route of Santiago de Compostela as Case Study. Available online: https://openarchive.icomos.org/id/eprint/151/1/77-Z2G7-92.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Permatasari, P.A.; Wijaya, D. Reviving the lost heritage: Batik cultural route in the Indonesian spice route perspective. In Current Issues in Tourism, Gastronomy, and Tourist Destination Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefan, L.; Gheorghiu, D. E-Cultural Tourism for Highlighting the “Invisible” Communities–Elaboration of Cultural Routes Using Augmented Reality for Mobile Devices (MAR). In Proceedings of the Current Trends in Archaeological Heritage Preservation: National and International Perspectives, Proceedings of the International Conference, Iaşi, Romania, 6–10 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Germanó, G. Diachronic 3D Reconstruction of a Roman Bridge: A Multidisciplinary Approach. In Digital Restoration and Virtual Reconstructions: Case Studies and Compared Experiences for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomopoulou, E.; Delegou, E.T.; Sayas, J.; Moropoulou, A. An innovative approach to the protection of cultural heritage: The case of cultural routes in Chios Island, Greece. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 14, 742–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beri, D.; Tomi, N. The Role of Promotion in toURIsts’ DeCIsIon to PARtAKe in a Cultural Route. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2014, 5, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, A. Quebrada de Humahuaca, Argentina: Opportunities and Threats of Tourism on a World Heritage Cultural Route. In Proceedings of the World Heritage International Exchange Symposium, ICOMOS-CIIC, Tokyo, Japan, 1 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aşan, K.; Yolal, M. Sustaining Cultural Routes: The Case of the Phrygian Way. In Heritage Tourism Beyond Borders and Civilizations: Proceedings of the Tourism Outlook Conference, Eskişehir, Turkey, 3–5 October 2018; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfeller, A.É.; Eisenberg, J. Scaling the local: Canada’s Rideau Canal and shifting world heritage norms. J. World Hist. 2015, 26, 491–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holladay, P.; Skibins, J.C.; Zach, F.J.; Arze, M. Exploratory Social Network Analysis of Stakeholder Organizations Along the Illinois and Michigan Canal National Heritage Corridor. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2017, 35, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paolis, R. Strategic Design for the Enhancement of Cultural Itineraries and Related Territories. “Via Regina”: A European Cultural Itinerary. In Putting Tradition into Practice: Heritage, Place and Design: Proceedings of 5th INTBAU International Annual Event 5, Milan, Italy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosavljević, U.; Kuletin Ćulafić, I. Use of cultural heritage for place branding in educational projects: The case of Smederevo and Golubac fortresses on the Danube. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzić, A.; Bjeljac, Ž. Cultural Routes-Cross-border Tourist Destinations within Southeastern Europe. Forum Geogr. 2016, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibireva, E. Pilgrims–Potential Peril or Promising Potential for Sustainability? Sustainability Challenges in the Management of the Camino de Santiago. In ISCONTOUR 2014—Tourism Research Perspectives: Proceedings of the International Student Conference in Tourism Research, Kola Kinabalu, Malaysia, 9–11 December 2014; BoD–Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2014; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Pereiro, X. The CICATUR Model Applied to the Cultural Heritage of the CPIS (the Portuguese Camino de Santiago). Available online: https://dspace.uib.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11201/155008/558489.pdf?sequence=1#page=148 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Larrauri, S. The Ways of St. James: Diversity, Dissemination and Disclosure of Jacobean Heritage. In Diversity in Archaeology: Proceedings of the Cambridge Annual Student Archaeology Conference 2020/2021; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2022; 402p. [Google Scholar]

- Beltramo, S. Cultural Routes and Networks of Knowledge: The identity and promotion of cultural heritage. The case study of Piedmont. Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2013, 4, 13–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scidurlo, P.; D’Angeli, G. Vie Francigene for All? Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2019, 10, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabbini, E. Cultural routes and intangible heritage. Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2012, 3, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneghello, S.; Mingotto, E. Local Active Engagement as an Effective Tool for Sustainable Tourism Development: First Considerations from the European Cultural Routes Case. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2020, 248, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xuereb, K.; Avellino, M. The Phoenician Cultural Route as a framework for intercultural dialogue in today’s Mediterranean: A focus on Malta. Almatourism-J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Dev. 2019, 10, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saintenoy, T.; Estefane, F.G.; Jofré, D.; Masaguer, M. Walking and Stumbling on the Paths of Heritage-making for Rural Development in the Arica Highlands. Mt. Res. Dev. 2019, 39, D1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, H.; Eryurt, E. Culture Routes İn Turkey. Available online: http://www.diadrasis.org/public/files/edialogos_003-ROBERT-ERYURT.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Zhou, M.; Wu, D.; WU, J. A framework for interpreting large-scale linear cultural heritage in the context of National Cultural parks: A case study of the Great Wall (in China). Landsc. Archit. 2023, 30, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, N. Integral Protection of Cultural Heritage of the Grand Canal of China: A Perspective of Cultural Spaces. Front. Soc. Sci. Technol 2020, 2, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, J.; Zhang, H. Spatial Reconstruction and Cultural Practice of Linear Cultural Heritage: A Case Study of Meiguan Historical Trail, Guangdong, China. Buildings 2022, 13, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.; Teron, L. Visualising Heritage: A critical discourse analysis of place, race, and nationhood along the Erie Canal. Local Environ. 2023, 28, 739–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, F.; Crozat, D. The Fonséranes lock on the Canal du Midi: Representation, reality and renovation of a heritage site. In Waterways and the Cultural Landscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, R.; Rodríguez, J.; Coronado, J.M. Modern roads as UNESCO World Heritage sites: Framework and proposals. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Keywords | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Cultural route | Cultural routes display route systems of cultural assets and historical sites created by cultural exchange and dialogue. These routes can integrate spiritual, economic, environmental, and cultural values into tourism systems [17]. |

| Heritage corridor | Cultural corridors are networks of cultural creativity and economic exchange based on a wide range of stakeholders. They form historical axes of ancient cultural and economic ties [6]. |

| Route heritage | A heritage route is composed of tangible elements of which the cultural significance comes from exchanges and a multi-dimensional dialogue across countries or regions and that illustrate the interaction of movement along the route in space and time [18]. |

| Keywords | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Origin | A geographically defined pathway of human movement that might have been created as a planned project or taken advantage (fully or partially) of pre-existing roads and evolved over a long period to fulfill a collective purpose [4]. |

| Context | Within a given cultural region or extended across different geographical areas that share a process of reciprocal influences in the formation or evolution of cultural values [5]. |

| Fundamental features | Long-lasting history with continuity in space and time, multi-dimensional function, wholeness, crossing and connecting borders, reflecting cross-fertilization of cultures (include a dynamic factor), associational value [3,5,19]. |

| Content | The communication routes itself, tangible heritage assets and intangible heritage elements [5]. |

| The Conservation Principle of Cultural Routes | Description | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticity | Historical and cultural characteristics | Authenticity should be evident in the natural and cultural context to prove its historic functionality. | [5] |

| Heritage discovery and restoration | Authenticity should be reflected in every part of the route and evident by the tangible and intangible heritage. | ||

| Integrity | Historical and cultural background | To ensure that the significance of the cultural and historical processes of routes can be fully demonstrated. | [5] |

| Route structure | Evidence of the historic relationships and dynamic functions essential to the distinctive character of the cultural route, whether its physical fabric and/or its significant features are in good condition, and whether the impact of deterioration processes is controlled. | ||

| Sustainability | Environmental protection | To protect the environment and natural landscape around the routes. | [2] |

| Activation and utilization | To promote local community well-being and economic development. | [2,20] | |

| Education and promotion | To improve the visibility of the routes and people’s awareness of heritage conservation. | [21] | |

| Categories | Description | Subcategories | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Routes used for specific events in a period of history | Pilgrimage route | [18] |

| Military route | |||

| B | Routes defined with the use of heritage or landscape | Heritage canal or valley | [22] |

| Historical border | |||

| Railway heritage | |||

| Highway heritage | |||

| C | Important routes in ancient times because of the need for transportation and trade | Trade, migration, or transportation routes | [5,22] |

| Tools of Cultural Tourism | Authenticity | Integrity | Sustainability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical and Cultural Characteristics | Heritage Discovery and Restoration | Historical and Cultural Background | Route Structure | Environmental Protection | Activation and Utilization | Education and Promotion | |

| Establishing route committees or associations | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | √ |

| Integral tourism management and route planning | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | / |

| Constructing infrastructure facilities along the routes | √ | √ | √ | √ | / | √ | / |

| Community participation | √ | / | / | / | √ | √ | √ |

| Establishing an official digital platform | √ | / | √ | / | √ | / | √ |

| Holding cultural events | √ | / | √ | / | × | - | √ |

| Commercialization | × | - | / | / | × | √ | / |

| Offering itinerary planning and travel programs | √ | / | √ | / | / | / | √ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, X.; Shen, Z.; Teng, X.; Mao, Q. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage 2024, 7, 2399-2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7050114

Lin X, Shen Z, Teng X, Mao Q. Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage. 2024; 7(5):2399-2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7050114

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Xinyue, Zhenjiang Shen, Xiao Teng, and Qizhi Mao. 2024. "Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review" Heritage 7, no. 5: 2399-2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7050114

APA StyleLin, X., Shen, Z., Teng, X., & Mao, Q. (2024). Cultural Routes as Cultural Tourism Products for Heritage Conservation and Regional Development: A Systematic Review. Heritage, 7(5), 2399-2425. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage7050114