Abstract

Rural areas are regaining attention as key resource holders. This includes the attractiveness of intact and traditional cultural elements and heritage which helps to create new opportunities. However, renewal is needed for rural areas to be competitive beyond tourism. Knowledge exchange and transfer is seen as an enabling tool for regeneration and heritage valorization, although it has mostly been applied in an urban context. The aim of this paper is to explore the role of capacity building and knowledge exchange at different levels in promoting rural regeneration through heritage-led initiatives. The article describes a multi-directional knowledge transfer and exchange in 19 rural areas. The applied knowledge exchange methodology was designed to be a dynamic and vibrant exchange of capacity building and mutual learning. This exchange of knowledge enabled the local communities involved to explore new ideas and viable solutions for the regeneration of rural areas through the valorization of cultural and natural heritage. The research findings show that structuring a knowledge transfer and capacity building process that also involves key local stakeholders and the rural communities is an important milestone in the regeneration process. In addition, it can be a unique opportunity to start and build new professional long-term relationships.

1. Introduction

Knowledge sharing, also known as peer-to-peer learning, is a mutual exchange of ideas and information [1]. This exchange is seen as a powerful way of sharing, replicating, and scaling up development processes [2]. The concept of knowledge exchange has been applied in different contexts. Originating in organizational studies, it has subsequently been used in many disciplines, from business management to medicine, to improve communication and scale-up innovation processes [3]. While the value of stakeholder engagement has grown, knowledge exchange has been increasingly sought for in development projects and planning practices in urban contexts [4]. Knowledge exchange has been conceptualized in a number of studies, including [5,6,7], as a tool for the valorization of cultural heritage in cities. UNESCO [8] argues that preserving cultural values is key to development. The literature recognizes the need for stakeholder engagement for sustainable heritage management. However, there is a gap between theory and practice in the implementation of stakeholder engagement in heritage management [9]. There is a lack of comprehensive methodologies for capacity building and knowledge exchange among actors at different levels (for example, local versus international), especially in rural regions. Indeed, although some scholars have investigated the effects of knowledge exchange for the valorization of cultural heritage in rural areas [6,10], it is not yet clear how to enable knowledge exchange for rural communities in a systematic and effective way. On the other hand, the low investments and attention that have been given to rural areas in the last decades has resulted in a lack of expertise and opportunities to foster cultural heritage-led regeneration processes. Within the last twenty years, the social sciences have focused on research actions on the local cultural heritage in its interconnections with the socio-economic development of regions as a form of the diversification and multifunctionality of economic and productive activities [11]. The increasing interest is due to the many resources that rural areas are key holders of [12,13]. This has opened up new perspectives on rural life and possible movements against urbanization [14]. The attractiveness of intact and traditional cultural elements and heritage in more remote areas has enabled new business opportunities, mainly related to tourism. Cultural and natural heritage play a key role in making certain areas competitive as tourist destinations [15,16]. Yet, innovation is needed to make rural areas competitive at local, national, and international levels beyond tourism. Biocultural heritage allows for new approaches to heritage, conservation, landscape planning, and development goals which rely on knowledge transfer and collaborative initiatives [17]. Access to new knowledge can be achieved through cooperation and exchanges with others [18]. Just like indigenous knowledge reflects knowledge that has been gained through living with a certain environment for centuries [19], new perspectives and knowledge are also needed to grow. Local partnerships and knowledge exchanges, for example, within farming communities, are crucial for rural development [20]. Ceccarelli [21] acknowledges the paramount importance of building networks with local as well as distant peers, with different cultures, traditions, and conditions, in order to acquire new knowledge and experience new forms of cooperation, also based on digital networks. Bosworth et al. [22] argue that real results are achieved when local groups in rural areas are empowered to make decisions within a supportive framework that is not overly bureaucratic. Bindi et al. [11] describe a gradual engagement of local communities, which starts with small groups of local actors who identify and propose innovative solutions to meet the needs of their respective communities, and progressively generates attention and consensus from other members, in a process leading to the progressive involvement of the entire community.

This study was carried out as a part of the H2020-funded innovation project RURITAGE, which focuses on rural regeneration through the valorization of cultural and natural heritage. The project identifies six heritage-led drivers for sustainable rural regeneration, called Systemic Innovation Areas (SIAs), which act as catalysts for rural development through stakeholder engagement [23,24]. They are Pilgrimage, Local Food Production, Migration, Arts and Festivals, Resilience, and Integrated Landscape Management. These areas were seen as starting the conversation about local heritage and contributing to sustainable growth beyond tourism-led activities through knowledge exchange at both local and international levels. During the project, a knowledge exchange took place in nineteen rural communities from twelve European Countries (in Ireland, Iceland, Norway, United Kingdom, Spain, Germany, Italy, Slovenia, Greece, Hungary, Turkey, and Romania), and one in South America (Colombia).

The aim of this paper is to provide practical insights into how and to what extent capacity building and knowledge exchange at different levels can contribute to rural development through heritage-led initiatives. The purpose of this research is to draw on the experiences of the RURITAGE knowledge exchange methodology by asking the following research questions: What are the key elements for successful multidirectional knowledge exchange? Furthermore, in order to capture the lessons from practice, we ask: To what extent and under what conditions does knowledge exchange between rural areas support local regeneration processes?

In the following sections of this article, we provide an overview of the RURITAGE conceptual framework and methodology, present the study results, and discuss the method in relation to the findings. We conclude the article by summarizing the key lessons that we have learnt from leading and implementing a multidirectional heritage-led knowledge transfer and exchange in nineteen rural areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

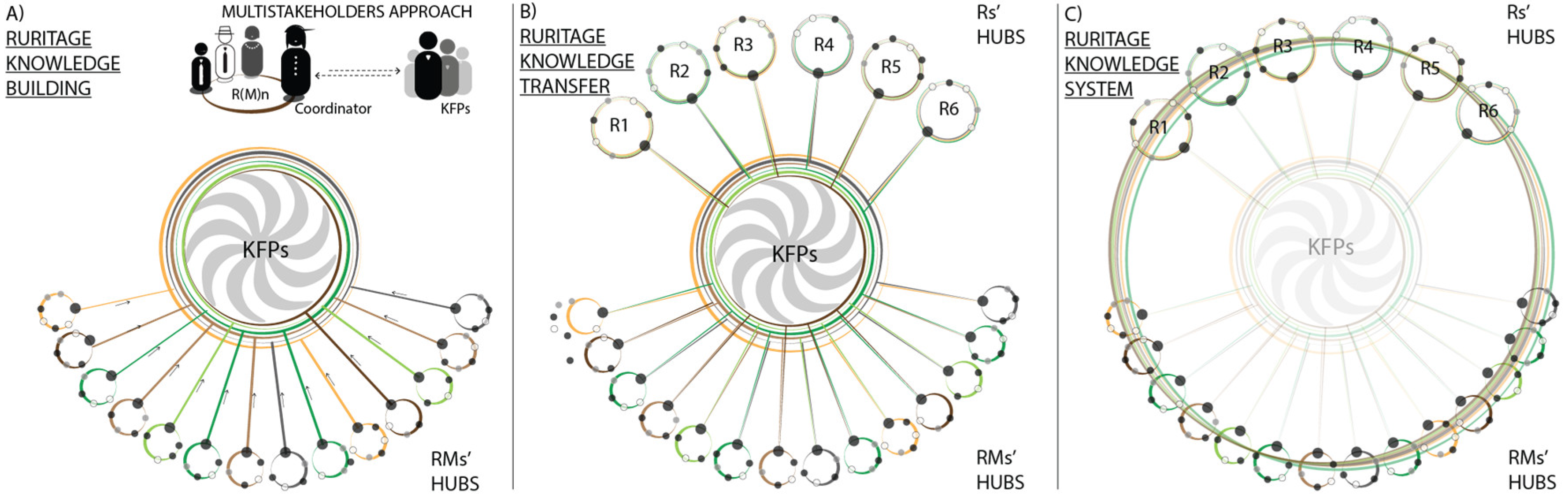

The RURITAGE project took place between June 2018 and August 2022. The project involved thirteen role model areas that had already demonstrated how heritage can act as a driver for positive rural regeneration and provided good practices of at least one of the SIAs. The multilevel repository of RURITAGE good practices is further described in [23]. The role models acted as mentors for six replicating territories that were aspiring to develop new heritage-led actions for rural regeneration within one or more SIAs. The exchanges between mentor and mentee were planned beyond the representatives of the participating entities, through the involvement of the local community. Understanding and mapping the wide range of actors that should be involved in regenerating their territory (Figure 1A) was one of the first steps of the process [24]. Guided by the project methodology and supported by the project funds, each involved community established a meeting place, called the Rural Heritage Hub, that functions both as a permissive space for exchanging ideas and a physical meeting place in daily community activities. For each Rural Heritage Hub, a coordinator was appointed to plan and manage the activities and to encourage various stakeholders to meet and share their ambitions for the territory [24].

Figure 1.

RURITAGE conceptual framework: (A) RURITAGE multilevel knowledge building; (B) RURITAGE knowledge exchange between role models (RMs), replicators (Rs), and knowledge facilitator partners (KFPs); (C) RURITAGE mutual knowledge exchange among role models and replicators.

The knowledge exchange between role models (RMs) and replicators (Rs) was facilitated by knowledge facilitator partners (KFPs) (Figure 1B). In total, seven universities, two research centers, two large international organizations, two SMEs, and four non-profit organizations were involved because of their expertise in a number of SIAs. They facilitated the knowledge transfer system from role models to replicators by collecting, analyzing, and digesting the information coming from the role models, and finally translating it into practical and replicable solutions.

Although the identification of the role model and replicator implies a one-way exchange, the methodology was designed to encourage a mutual learning process (Figure 1C). Replicators were expected not only to learn, but also to share their experiences with each other and with the role models, who also benefited from the process by improving their regeneration strategies. The exchange and mutual learning between role models and replicators were the basis of the RURITAGE paradigm and the effective implementation of the planned activities.

2.2. Methodological Steps

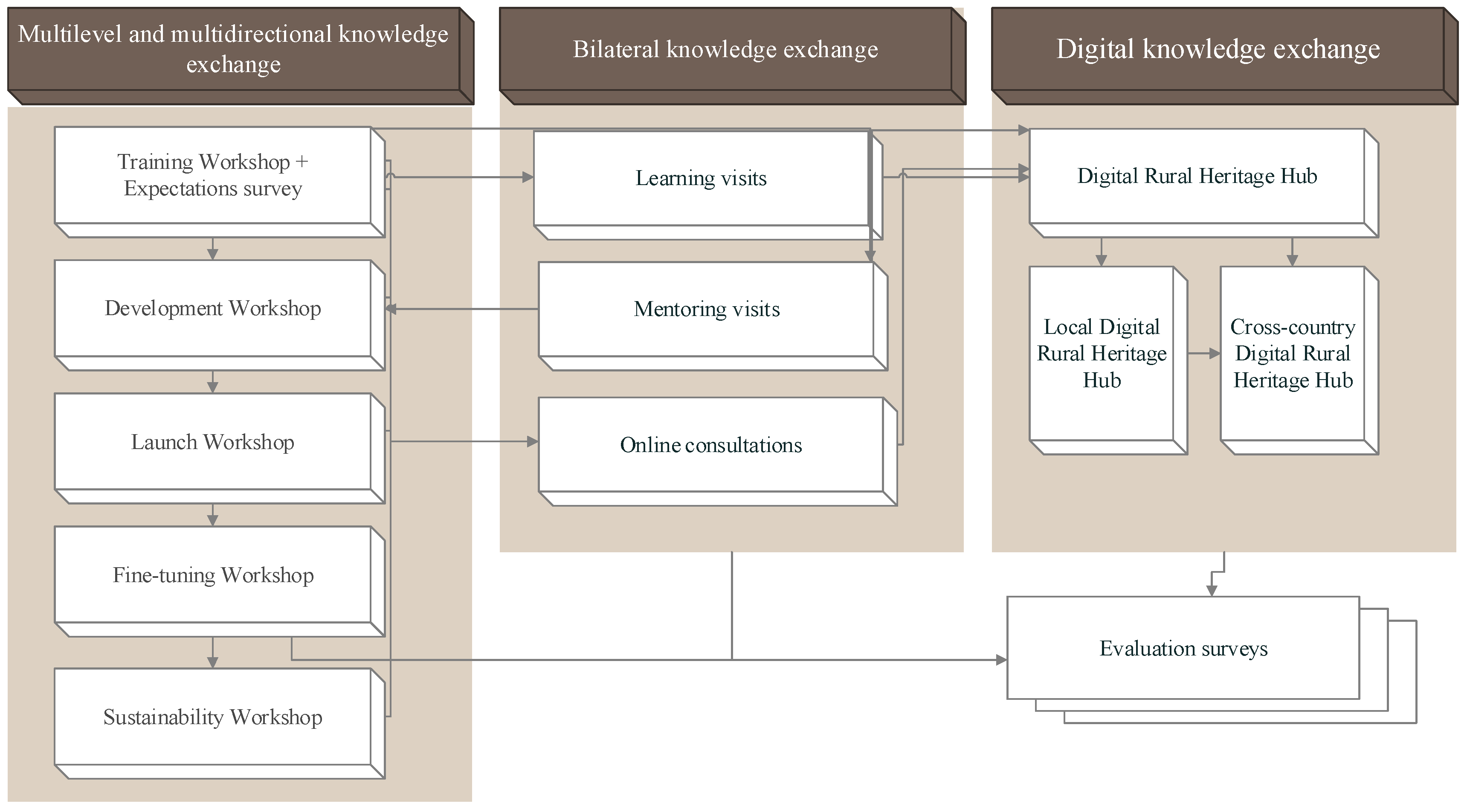

To ensure that the RURITAGE knowledge exchange was useful in practice, we developed a rigorous methodology that can be replicated beyond the project framework. The methodology offers three main forms of knowledge brokerage: (i) multilevel knowledge-transfer workshops, (ii) bilateral knowledge exchange events, and (iii) digital knowledge exchange. The interaction between the different forms is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of RURITAGE knowledge exchange methodology.

The multilevel and multidirectional knowledge transfer involved five workshops (i.e., Training, Development, Launch, Fine-Tuning, and Sustainability Workshops) following the main stages of the development of the Rural Regeneration Plan [24,25]. At the beginning of the project, all participants were asked to indicate their expectations and interest in the forthcoming knowledge exchange. The representatives of each role model and replicator submitted a form in which they ranked (from 1 to 10/least to most) the good practices of other role models [22] which they found the most interesting and which they could potentially replicate. These preferences were taken into account in the preparation of the thematic workshop sessions, in the design of bilateral exchange pairs, and in the identification of topics for digital exchanges.

In parallel with the five planned workshops, bilateral knowledge exchanges and brokerage events were organized between the role models and replicators. These took form of learning or mentoring staff visits, with a replicator or role model partner visiting another area and vice versa. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the RURITAGE bilateral visits were postponed from March 2020 to March 2022. During this period, a series of online consultations were introduced to partners as an alternative to face-to-face interactions to ensure continuous communication and knowledge transfer between role models, replicators, and knowledge facilitator partners.

An ongoing digital knowledge exchange framework has further strengthened the capacity building and knowledge exchange. As well as ensuring ongoing interactions, the digital exchanges were also an accessible way of storing information and good practices digitally. The digital knowledge exchange was carried out mainly as: (1) mutual learning at a project level through a digital platform called Digital Rural Heritage Hub (Digital RHH), which was set up like in a forum format where partners could open new threads and comment on each other’s posts [26]; (2) learning at a project and international level through a series of online webinars.

As the partners are geographically diverse and come from different cultural, religious, and linguistic backgrounds, representatives from the Rural Heritage Hubs were, therefore, important cornerstones in achieving successful exchanges, bridging the initiative at the project and the local communities. Although all project activities were conducted in English, all activities and initiatives were also translated into the national languages of each Rural Heritage Hub and adapted to the local context. This was a way of ensuring that everyone felt involved and prioritized in the exchanges.

To evaluate the impact of the capacity building activities, participants were asked to complete surveys at the end of each activity. In addition, an overall evaluation survey was conducted with all the partners involved at the end of the project.

It should be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic occurred in early 2020 which had an impact on all aspects of RURITAGE implementation, including the travel and visit plan. The impact of the pandemic can be seen in the results section below.

3. Results

The results are presented according to the planned knowledge exchange methodology. This section describes the series of events (see Figure 3) together with the results from the surveys.

Figure 3.

The knowledge exchange activities (photo credit: Åberg, 2022; RURITAGE, 2019).

3.1. Multilevel and Multidirectional Knowledge Transfer: Results from Five Workshops

Five milestone workshops were planned to ensure a knowledge transfer and brokerage between different SIAs, involving Rural Heritage Hubs beyond the mentor–mentee relationship of role models and replicators. In total, 72 to 95 people benefited from each workshop.

The five workshops (i.e., the Training Workshop, the Development Workshop, the Launch Workshop, the Fine-Tuning Workshop, and the Sustainability Workshop) were designed to be aligned with the stages of the heritage-led development projects in the replicator and role model regions. All workshops combined lecture-style sessions delivered by knowledge facilitator partners with more interactive sessions. Parts of the workshops also provided direct support and bilateral exchanges between partners. The knowledge gained by the partners during these workshops was to be shared with the local community.

The Training Workshop in March 2019 was the first step of the multidirectional knowledge transfer system (as shown in Figure 1C). The event aimed to guide the coordinators of the Rural Heritage Hubs through the Community-based heritage management and planning methodology [24]. One of the initial steps of this methodology was the Serious Game Workshop, which was to be held in each Hub. The game aimed to highlight the challenges and needs in each rural area. The training consisted of a simulation of the Serious Game Workshop, followed by a question-and-answer session, to prepare the Rural Heritage Hubs coordinators to run the workshop at a local level within their local Hub. Alongside the training, three parallel sessions on the different SIAs were organized. Each role model provided local tricks and tips, as well as lessons learned and good practices from the implementation of heritage-led practices in their area. At the end of these sessions, there was a discussion round on each SIA with specific questions on good practices, challenges, and the key elements needed.

The second workshop, the Development Workshop, took place in May 2019. The aim of this workshop was to support the implementation phase of the heritage-led development projects at a local level. This was organized through training workshops that the partners would later apply in their Rural Heritage Hubs, according to the RURITAGE methodology [24]. The first session focused on how to find and approach investors, benefiting from both external experts and the experiences of role models. The aim of this session was to support replicators in realizing their ideas. Other sessions focused on the challenges and possibilities faced by the participating rural territories while setting up and deploying their Rural Heritage Hubs.

The Launch Workshop, held in October 2019, was designed to support replicators in launching their heritage-led development plans. The replicators presented draft versions of their plans together with a detailed list of the first steps for their implementation. Role models and knowledge facilitator partners provided direct feedback and experiences on the proposed plans. The Role Models were given the opportunity to hold bilateral meetings with other Role Models and/or Knowledge Facilitator Partners in recognition of their willingness to further enhance their position in rural regeneration. This contributed to ensure a multi-directional exchange of knowledge.

The fourth workshop, the Fine-Tuning Workshop, although originally planned in May 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic took place online in October 2020. The aim was for partners to adapt and improve their planned development plans with the help of others. During this workshop, replicators presented their initial successes in implementing the regeneration plans, along with potential questions and difficulties, while role models presented their path towards their rural regeneration enhancement plans [27]. Experts on financial investments were also available for questions and ideas on how to generate investments.

To ensure sustainability and long-term thinking beyond the project, the fifth and final workshop, the Sustainability Workshop, took place during the final phase of the project in April 2022. The focus of the discussion was twofold: the sustainability of the project’s legacy, and the tangible traces the project had left on the ground. To address the former, all partners participated in a discussion on how to maintain the knowledge the community created during the funding period. To address the latter, replicators and role models were invited to discuss the financial and social opportunities made possible by the project and how they could sustain these initiatives without RURITAGE project funding.

The evaluation of the impact of the five workshops was carried out through online surveys. Overall, the results indicate that the workshops were highly valued by participants. The participants had a number of takeaways when asked about the main outcomes of the multilevel and multidirectional knowledge transfer workshops. The respondents noted that the workshops encouraged interaction, discussion, and learning; facilitated the building of trust and cooperation between project partners; and provided fresh ideas and practical advice on how to implement rural regeneration strategies.

When asked what type of knowledge transfer methods they found most useful, most participants answered ‘interactive sessions and discussions between replicators, role models and knowledge facilitator partners’. Participants felt that these sessions allowed them to develop closer mentor/mentee relationships.

In terms of the benefits of face-to-face workshops, most participants felt that ‘interacting with different people from different backgrounds’ was the greatest benefit. This was followed by a ‘better understanding of others’ experiences’ and ‘networking’. One of the workshops, the Fine-Tuning Workshop, was held online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. As expected, although most participants found the online modality to have advantages, such as being safer and less expensive, they felt that the online format did not provide the same level of social interaction as face-to-face meetings.

Finally, the vast majority of participants felt that the overall expectations of the workshops were met. The majority of participants felt that the social and networking moments during the workshops were well organized and led to better, stronger professional and informal relationships with partners, with plenty of networking moments. It was generally emphasized that there was value in having a balance between more formal and informal communication during the events. Although participants expressed that the events were intense, they were not seen as debilitating in the end, but as well worth the time.

3.2. Bilateral Knowledge Exchange: Learning and Mentoring Visits

The learning and mentoring visits were designed as two types of bilateral knowledge exchange. The key personnel of each replicator or role model travelled to other role models to learn about the barriers, lessons, and success factors of the practices implemented. Conversely, the key personnel of each role model travelled to the replicators and role models to provide local insights and advice. To facilitate the bilateral exchange of knowledge, the protocols of the visits were established and evaluation forms were completed after each visit. In addition, the KFPs supported the rural territories throughout the bilateral knowledge transfer process, providing input and guidance as needed.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a series of online consultations replaced the face-to-face visits. The online exchanges followed the model of learning and mentoring visits. Therefore, they provided comparable bilateral communication and professional knowledge transfer and guidance based on the identification of needs and inputs.

Nineteen face-to-face and five online consultations enabled partners to share knowledge and learn from each other. All role models and replicators participated at least once in a bilateral knowledge exchange visit. In total, 84 staff members took part in the exchanges, together with 210 stakeholders such as local producers, museum directors, pilgrimage route managers, researchers, tourist guides, or representatives of local associations. Participants visited 16 countries and 129 sites, including local markets and farms, museums, art galleries, and nature reserves.

The results of the evaluation survey confirmed that the main benefits of the bilateral visits were the ‘exchange of good practices’, a ‘better understanding of partners’ experiences’, the ‘creation of a wider network and greater trust’, and ‘interaction with people from different backgrounds’. Bilateral exchanges helped partners to acquire new skills by the following: (i) helping to build a stronger network, (ii) providing access to expert knowledge, (iii) sharing practical advice and best practice, (iv) teaching facilitation techniques, and (v) learning how to better engage stakeholders.

The respondents identified the most important outcomes as (i) increasing their network, (ii) providing fresh ideas and practical advice on how to implement rural regeneration strategies, (iii) increasing their knowledge of rural regeneration, (iv) facilitating the sharing of their expertise and knowledge with other partners, (v) encouraging interaction, discussion, and learning, and (vi) building trust and cooperation between stakeholders.

When asked if they intended to continue working with RURITAGE partners after the end of the project, most respondents answered positively. To do this, they plan to engage online, through emails, social media, and online meetings, before planning new face-to-face visits, either at conferences or on new joint projects.

3.3. Digital Knowledge Exchange

An open-access digital hub for rural regeneration, the RURITAGE Resource Ecosystem [26], was created to further promote knowledge sharing, mutual learning, and collaboration within rural communities and relevant stakeholders. The main tool for internal communication was the Digital RHH, an open platform for continuous knowledge sharing, thematic discussions, and networking within the RURITAGE community. It consists of a discussion forum organized by SIA and by thematic tags, and it has both a project level in English, and a local level, at a Rural Heritage Hub scale, in a local language to allow for the dissemination of information among the local community. The tool acts as an open forum for knowledge exchange between RURITAGE partners and stakeholders.

As of May 2023, five years after the project started, there were 383 registered users on the Digital RHH and 910 posts grouped into 248 topics. Overall, as confirmed by the feedback survey, the Digital RHH has proven to be an important tool for ongoing engagement within the RURITAGE community, increasing collaboration, discussion, social inclusion, and participatory decision-making, and maintaining motivation and momentum among stakeholders.

In addition to the digital tools, continuous learning was promoted through a series of webinars. The topics were tailored to the needs and interests of role models and replicators. In addition, the webinars were open to the public with a total of more than 700 registered attendees. Twenty-six webinars were delivered by RURITAGE partners throughout the project. The webinar series started with an introduction to the RURITAGE methodology followed by six SIA presentations. Toward the second part of the project, the webinars focused on specific topics of interest of the consortium (i.e., heritage and sustainable tourism and disaster risk management for heritage).

4. Discussion

To further bridge the gap between professionals and local communities, knowledge exchange and transfer through stakeholder engagement is key to sustainable rural regeneration [28]. Although stakeholder engagement is a time-consuming process, our experience with the RURITAGE knowledge exchange methodology, in line with Leyden et al. [29], suggests that it is worth the time and effort put into it. We demonstrated how knowledge exchange can be enabled for rural communities through a consistent approach. The findings of this research suggest that the key elements that enable a successful multidirectional knowledge exchange in rural areas are the following:

- A predetermined framework for knowledge transfer and exchange: this provides participants with an overview of their expected interactions, efforts, and outcomes. As there will never be a one-size-fits-all model for rural regeneration [30], sharing expectations in advance gives each community the opportunity to inform their stakeholders at an early stage and adapt the framework to their local needs.

- A mixed-methods approach: by using different ways and means to encourage knowledge exchange and transfer, the involved stakeholders receive a more varied input which ensures continued engagement and sustains interest.

- Ongoing exchange and transfer: through a variety of tools and methods, stakeholders have repeated opportunities to share knowledge. This allows them to reflect on their process and share their experiences at different stages of their work. Especially in the initial phase, close-up workshops represent a crucial component for trust building, which is necessary for successful knowledge exchange [18]. In addition, the Digital RHH provided an ongoing forum for exchange and served as an outlet for immediate ideas, questions, or concerns.

This research further explored the extent to which, and the conditions under which, knowledge transfer can support rural areas in regeneration processes. It suggests the most impactful ways of engaging a local community are the following:

- The multidirectional learning workshops were seen as an effective tool for interaction, discussion, and learning. As building trust is crucial for successful and sustainable exchanges [18], such workshops created multiple co-benefits and facilitated the establishment of trusting and collaborative relationships between partners. Through a combination of lectures and interactive exchanges, the sessions encouraged both formal and informal discussions.

- Although roles such as “role models” and “replicators” were defined by the methodology and were needed at the beginning of the project to structure the knowledge exchange process, once the local communities started to define their heritage-led regeneration actions and to implement them, replicators soon turn into role models themselves, as they inspired the regeneration enhancement plan developed by each role model in the late stage of the project [27]. The mutual knowledge exchange truly inspired the local communities, who felt acknowledged for their contribution to the heritage-led regeneration process of other communities.

- Beyond the framework of the RURITAGE project, the project partners initiated new collaborations based on their interests and competences that emerged during the knowledge exchange. What started as discussions during the workshops became new initiatives between partners. This led to applications and successful funding for new collaborative projects.

The results of this research suggest some guidelines for the future application of transferring and exchanging knowledge in rural areas:

- From an urban perspective, Frantzeskaki and Rok [31] state that collaborative learning, collective and individual empowerment, and connections across sectors are valuable for any community. It is not only the geographical isolation of rural areas, but also the social and economic isolation [32] that makes knowledge exchange and transfer initiatives even more necessary. It was recognized by the case study participants that more stakeholders should be involved in the multilevel and multidirectional knowledge exchange. As highlighted by Bindi et al. [11], empowering and motivating the communities can progressively stimulate the ability to rethink their own territory. This would support future commitment and the availability of new initiatives.

- The importance of appointing a local gatekeeper. Each partner was required to provide funding to employ one person in each Rural Heritage Hub. The findings suggest that this person was key to bridging the language gap between the project and the local community. Although this person was also likely to have played a key role in bridging social and cultural aspects, this was never explored further.

- Digital versus physical knowledge exchange. As mentioned above, many physical meetings were replaced by online interactions due to the pandemic. The digital exchanges were key to maintaining ongoing communication between project partners. However, the lack of face-to-face interaction means fewer opportunities to build relationships and trust, and more challenges for equity and equality, which can limit the effectiveness of knowledge sharing. On the other hand, digital transformation can (i) reduce barriers to participation, (ii) provide more opportunities to hear from broader and more diverse groups, and (iii) allow for more frequent and easier meetings. However, the unanticipated digital uses were undoubtedly a challenge for some participants, depending on their level of digital literacy. Although we provided guidance and support, future studies may need more time and effort to ensure that people of all ages feel included.

The majority of the case studies were located in rural areas across Europe. During the project, other non-funded communities were given the opportunity to participate in the RURITAGE events and benefit from the multidirectional heritage-led knowledge exchange. In addition to the provision of educational material through the digital tools, training opportunities and workshops were initiated to share the overall lessons from the project together with the UNESCO Latin America Office [33]. For future initiatives, it would be relevant to further explore how the knowledge exchange methodology can be applied and readapted to a non-European context.

We are aware that researchers have acted as facilitators of community-led initiatives, which could be seen either as a means of somehow shielding participants from the everyday tensions [31] coming from the contradictory role expectations between the organizers and the users [34], or what Farmer et al. [35] called a protective niche. This means that future initiatives may either require external facilitators or include training or exchanges between participants to make everybody confident with the diversity in roles.

5. Concluding Remarks

Stakeholder engagement is considered essential for sustainable heritage management and regeneration processes, but there is a recognized gap between theory and practice in implementing means to engage stakeholders and enable an effective knowledge transfer in rural areas. This study contributes to the bridging of theory and practice through practical applications, with insights and lessons learned from practice in nineteen rural areas over a four-year period.

The methodology itself was pre-defined for all pilot areas, so there was an understanding of what was expected, but the application and tools varied. Although the methodology required a minimum level of commitment, local areas were able to adapt it to their own capacity and needs. As a first step in the process, partners were able to share their own expectations. This was followed by three main levels of interaction: through multilevel and multidirectional knowledge transfer workshops involving all project partners; through bilateral knowledge exchange organized directly between two partners together with their stakeholders; and lastly, through a digital platform that enabled continuous knowledge exchange and sustained interaction.

The flexibility and variety of the tools included in the multidirectional heritage-led knowledge exchange methodology ensured continued engagement and were seen as maintaining interest throughout the process. The study also recognizes the need for trust in building long-term relationships and exchanges. By providing a model for knowledge exchange and transfer that also focuses on community knowledge, this can provide an opportunity to regenerate heritage through knowledge and preserve assets for the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.P., A.S., K.H. and S.T.; Methodology, H.E.Å., I.P. and A.S.; Investigation, H.E.Å., I.P., A.S. and Z.A.; Data curation, I.P. and Z.A.; Writing—original draft, H.E.Å.; Writing—review and editing, I.P. and A.S.; Supervision, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 776465. The sole responsibility for the content of this web page lies with the authors. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the European Union. Neither the EASME nor the European Commission is responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to GDPR related reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the RURITAGE partners and especially the 19 Rural Heritage Hub Coordinators for their enthusiasm and commitment which strongly contributed to the success of the knowledge exchange.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yeo, R.; Dopson, S. Chapter 3—Lose It to Gain It! Unlearning by Individuals and Relearning as a Team. In Organizational Learning in Asia: Issues and Challenges; Hong, J., Snell, R.S., Rowley, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 41–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobha, K.; Leonard, A. The Art of Knowledge Exchange: A Results-Focused Planning Guide for Development Practitioners; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Helbig, N.; Dawes, S.; Dzhusupova, Z.; Klievink, B.; Mkude, C. Stakeholder Engagement in Policy Development: Observations and Lessons from International Experience. In Policy Practice and Digital Science, 10th ed.; Public Administration and Information Technology; Janssen, M., Wimmer, M., Deljoo, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkinen, A.; Mäkelä, H.; Kujala, J.; Nieminen, J.; Jokinen, A.; Rekola, H. Urban Ecosystem Services and Stakeholders: Towards a Sustainable Capability Approach. In Strongly Sustainable Societies; Organising Human Activities on a Hot and Full Earth; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Giambruno, M.; Pistidda, S. Cultural Heritage for Urban Regeneration. Developing Methodology through a Knowledge Exchange Program. In Sustainable Urban Development and Globalization; Research for Development; Petrillo, A., Bellaviti, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, M.; Józsa, V. Cultural Heritage Valorisation for Regional Development. Köz-Gazdaság 2021, 16, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Woosnam, K.M. Considering urban regeneration policy support: Perceived collaborative governance in cultural heritage-led regeneration projects of Korea. Habitat Int. 2023, 140, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Power of Culture for Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000189382 (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Lou, E.C.; Lee, A.; Lim, Y.M. Stakeholder preference mapping: The case for built heritage of Georgetown, Malaysia. J. Cult. Heritage Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monova-Zheleva, M.; Zhelev, Y.; Stewart, R. An Approach for Valorisation of the Emerging Tacit Knowledge and Cultural Heritage in Rural and Peripheral Communities. In Digital Presentation and Preservation of Cultural and Scientific Heritage; Conference Proceedings; Institute of Mathematics and Informatics—BAS: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2019; Volume 9, ISSN 1314-4006. [Google Scholar]

- Bindi, L.; Conti, M.; Belliggiano, A. Sense of Place, Biocultural Heritage, and Sustainable Knowledge and Practices in Three Italian Rural Regeneration Processes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, A.K.; Krzysztofowicz, M. Scenarios for EU Rural Areas 2040. Contribution to European Commission’s Long-Term Vision for Rural Areas. Luxembourg. 2021. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/scenarios-eu-rural-areas-2040_en (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Slätmo, E. Preservation of Agricultural Land as an Issue of Societal Importance. Rural. Landsc. Soc. Environ. Hist. 2017, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkartzios, M.; Halfacree, K. Editorial. Counterurbanisation, again: Rural mobilities, representations, power and policies. Habitat Int. 2023, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Guizzardi, A. Does Designation as a UNESCO World Heritage Site Influence Tourist Evaluation of a Local Destination? J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, K.-J.; Ekblom, A. A framework for exploring and managing biocultural heritage. Anthropocene 2019, 25, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintossi, N.; Kaya, D.I.; van Wesemael, P.; Roders, A.P. Challenges of cultural heritage adaptive reuse: A stakeholders-based comparative study in three European cities. Habitat Int. 2023, 136, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Knickel, K.; Díaz-Puente, J.M.; Afonso, A. The Role of Social Capital in Agricultural and Rural Development: Lessons Learnt from Case Studies in Seven Countries. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Fang, M.; Beauchamp, M.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Z. An indigenous knowledge-based sustainable landscape for mountain villages: The Jiabang rice terraces of Guizhou, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 111, 102360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futemma, C.; De Castro, F.; Brondizio, E.S. Farmers and Social Innovations in Rural Development: Collaborative Arrangements in Eastern Brazilian Amazon. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarelli, P. Minor Settlements: Setting up a Network of Creative and Sustainable Communities. In Sustainable Urban Development and Globalization; Agostino, P., Paola, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosworth, G.; Price, L.; Hakulinen, V.; Marango, S. Rural Social Innovation and Neo-Endogenous Rural Development. In Neoendogenous Development in European Rural Areas; Cejudo, E., Navarro, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egusquiza, A.; Zubiaga, M.; Gandini, A.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S. Systemic Innovation Areas for Heritage-Led Rural Regeneration: A Multilevel Repository of Best Practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luca, C.; López-Murcia, J.; Conticelli, E.; Santangelo, A.; Perello, M.; Tondelli, S. Participatory Process for Regenerating Rural Areas through Heritage-Led Plans: The RURITAGE Community-Based Methodology. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åberg, H.E.; de Luca, C.; Santangelo, A.; Tondelli, S. RURITAGE Heritage-Led Regeneration Plans for Replicators; Deliverable 3.5; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamborrino, R.; Patti, E.; Aliberti, A.; Dinler, M.; Orlando, M.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Barrientos, F.; Martin, J.; Cunha, L.F.; et al. A resources ecosystem for digital and heritage-led holistic knowledge in rural regeneration. J. Cult. Heritage 2022, 57, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, L.; de Luca, C.; Tondelli, S.; Santangelo, A.; Conticelli, E.; Åberg, H.E. Role Model Regeneration Enhancement Report; Deliverable 3.5; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greser, J.; Kamiński, R.; Klatta, P.; Knieć, W.; Martinez-Perez, J.; Sitek, A.; Wagstaff, A. Knowledge Transfer, Knowledge Acquisition and Qualifications in the Context of Rural Development in Poland. Eur. Countrys. 2021, 13, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyden, K.M.; Slevin, A.; Grey, T.; Hynes, M.; Frisbaek, F.; Silke, R. Public and Stakeholder Engagement and the Built Environment: A Review. Curr. Environ. Heal. Rep. 2017, 4, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janc, K.; Dołzbłasz, S.; Raczyk, A.; Skrzypczyński, R. Winding Pathways to Rural Regeneration: Exploring Challenges and Success Factors for Three Types of Rural Changemakers in the Context of Knowledge Transfer and Networks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Rok, A. Co-producing urban sustainability transitions knowledge with community, policy and science. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transitions 2018, 29, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marilena, L.; Navarro Valverde, F. Depopulation and Aging in Rural Areas in the European Union: Practices Starting from the LEADER Approach. Perspect. Rural. Dev. 2019, 3, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regional Policy Workshop: Cultural and Natural Heritage for Rural Regeneration in Latin America and the Caribbean; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://es.unesco.org/sites/default/files/regionalpolicyworkshopmtv_final.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2024).

- Voorberg, W.H.; Bekkers, V.J.J.M.; Tummers, L.G. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 1333–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.; Carlisle, K.; Dickson-Swift, V.; Teasdale, S.; Kenny, A.; Taylor, J.; Croker, F.; Marini, K.; Gussy, M. Applying social innovation theory to examine how community co-designed health services develop: Using a case study approach and mixed methods. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).