1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the concept of “virtual museums” (VMs) has rapidly evolved due to technological advancements. Undoubtedly, the consequences of COVID-19, in particular, the inaccessibility of most cultural places for months, have boosted the needs in this field as well as clarified weak points in the digital preparedness of institutions and operators. Several initiatives and EU programs have highlighted the importance of innovating narratives in geoinformation and sustaining the digital transformation of touristic practices. This digitization can undoubtedly enhance the visitor experience, adding a layer of richness to the tourist practice by providing dynamic, context-aware stories that engage and captivate users, creating a more immersive and memorable journey. Leveraging geo-storytelling allows for the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage: through digital transformation, tourists can explore historical sites and cultural landmarks with augmented reality and virtual guides, ensuring the continuity of cultural appreciation. In addition, personalized travel experiences can be tailored to individual preferences and interests. By utilizing digital tools, tourists can access personalized recommendations, creating a more satisfying and relevant travel experience, but these tools can also foster community involvement by showcasing local stories, traditions, and businesses. This not only benefits the local economy but also encourages responsible tourism, creating a mutually beneficial relationship between tourists and communities.

The leading examples of smart tourism practices in Europe [

1], extracted from the 2023 European Capital of Smart Tourism competition, included, in the category of digitalization that makes tourism smart, different examples of digital tours, city exploration, and augmented reality apps, related to the same concepts above. In particular, it is highlighted that digital tourism and e-tourism mean offering innovative tourism and information, products, services, spaces, and experiences adapted to the needs of the consumers through ICT-based solutions and digital tools.

The project presented here was developed during the time of the pandemic and certainly faced its challenges. However, it also seized the opportunities that this disruption created and that affected cultural heritage institutions, as synthetized in [

2]. Additionally, it serves as a notable example of widespread heritage. It is a multi-scalar, multilayer virtual museum in which a systematized heritage, specifically that of the Adriatic ports, is seamlessly presented alongside individual artifacts and folk traditions. The project leveraged the concept of geo-storytelling and applied two augmented reality technologies for site-specific installations. This paper proposes, through the critical presentation of the VM, a methodology that can be reused in other contexts, also providing toolkits for both its implementation and a user satisfaction survey, as well as analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of some specific experiences. The goal of the present research is thus to establish a consolidated methodological framework for designing, developing, implementing, and assessing a virtual museum, fully featured with 3D models and augmented reality technologies.

The Interreg REMEMBER project (restoring the memory of Adriatic ports sites—maritime culture to foster balanced territorial growth) focused on leveraging the historical, cultural, and economic significance of Adriatic ports for the sustainable development of the surrounding territories. The project was triggered by the rich history and complexity of the Adriatic region and tried to bridge the gap between past and future by preserving and promoting the cultural heritage associated with the ports. The project acknowledged the thousand-year history of the Adriatic region, emphasizing the importance of the traditions, stories, and professions that have shaped its maritime culture. This history formed a basis for understanding the present and guiding future development.

The project envisioned a dual perspective that connects the present with the past, thus forming the core identity of port cities. This identity encompasses cultural elements, economic activities, and investments, placing ports at the heart of local community development. Despite its complexities, the Adriatic region is seen as a “community” where commonalities outweigh differences. The unique nature of the Adriatic Sea is highlighted as a microcosm of the larger Mediterranean [

3,

4].

The REMEMBER project established a network between cities, particularly through collaboration between Italian and Croatian partners. This collaboration is facilitated by a cloud-based platform designed to enhance maritime assets and promote the overall objectives of the project: a new virtual museum built up in a collaborative way by the partnership and currently kept alive by the entity developed by the Remember project thanks to a Memorandum of Understanding.

The project created a new platform, “Adrijo”, by combining the Italian word “Adriatic” with the Croatian word “Jadransko”, which reflects a linguistically constructed unity between the two sides of the Adriatic region. This new virtual museum symbolizes the collaborative network among the ports of eight maritime cities: Ancona, Ravenna, Venice, Trieste, Fiume, Zara, Split, and Dubrovnik. These cities are all part of the REMEMBER project, sharing a deep-rooted maritime cultural heritage, historical connections, and a sense of belonging that has developed through centuries of commercial and social interactions.

In addition to the platform, the project involves the creation of eight local virtual museums (VMs). These VMs combine the conventional museum experience with the advantages offered by information and communication technology (ICT). The concept of these VMs aims to provide a “remote immersive experience” related to maritime and port heritage. This addresses the constraints such as limited time or resources for travel and lack of physical exhibition space. The VMs facilitate the easy dissemination of shared knowledge to distant locations and enable the circular utilization of the common heritage among the participating cities.

The paper starts with a summary of the state of the art regarding VMs, including some interesting experiences based on mixed and augmented reality. The methodology chapter presents the three levels of the Adrijo virtual tool, from the general level regarding the eight ports, to the Ancona VM and its multifaceted contents, finishing with the AR experience developed for the Arch of Trajan. The results section thus presents the most significant achievement of this research: the toolkit for developing similar digital experiences. Moreover, the effectiveness of the obtained solutions is tested with different methods, such as usability tests, web analytics and questionnaires, all presented for the sake of being thorough and able to be repeated. The conclusion contains both the results and a critical discussion of the VM.

2. State of the Art

The concept of virtual museums traces back to 1947 when André Malraux introduced the notion of an imaginary museum known as the “Musée imaginaire” [

5]. This involved assembling a collection of art and cultural artifacts from different civilizations and eras using reproductions, photos, and visual media. This concept envisioned a museum without a physical location, walls, or boundaries, which aimed to make art accessible to people from diverse backgrounds and include art which was previously inaccessible to many. Today, VMs have gone beyond being simple “digital copies” of real-world museums or being restricted just as mere online entities. They have become sophisticated communication tools, closely connected to concepts such as storytelling, interaction, and immersive 3D experiences [

6].

Although the term ‘virtual museum’ was coined in the early 1990s, the improvements in information and communication technology (ICT) have driven virtual museums to reflect this technological advancement, leading to a wide range of possibilities and interpretations when it comes to a closer definition [

7]. Terms such as “cyberspace museum”, “digital museum”, “electronic museum”, “experiential museum”, “internet museum”, “online museum”, and “web museum” were often used interchangeably, resulting in a lack of clarity and consensus with a continuous under-developed definition of VMs and the need to shed light on the differences between digital collections, online archives, and virtual museums [

8,

9,

10].

Over the years, several definitions have been proposed [

11,

12], focusing on different aspects that can define what a VM is. Among EU-funded initiatives, the V-Must project (Virtual Museum Transnational Network), spanning from 2011 to 2015, played a crucial role in documenting and analyzing various virtual museums both in and outside Europe [

13]. As an outcome, the project introduced a broad framework relating to virtual museums based on the collaboration of different professionals involved in the field, who produced a structured glossary [

14] and defined a VM as “a digital entity that draws on the characteristics of a museum, in order to complement, enhance, or augment the museum experience through personalization, interactivity and richness of content. Virtual museums can perform as the digital footprint of a physical museum, or can act independently, while maintaining the authoritative status as bestowed by ICOM in its definition of museum. In tandem with the ICOM mission of a physical museum, the virtual museum is also committed to public access; to both the knowledge systems imbedded in the collections and the systematic, and coherent organization of their display, as well as to their long-term preservation.” [

15].

This definition highlights a virtual museum’s ability to bridge the gap between physical and digital spaces, sharing the purpose of preserving and promoting knowledge with brick-and-mortar museums. Even though they might be commonly considered simply as a ‘web counterpart’ in terms of information content and related functions (archives, ticketing, communications, etc.), the role of such entities has changed substantially over the years, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. VMs contribute to the mission of fostering cultural understanding, education, and visitors’ engagement, serving several purposes.

Firstly, they serve as a means to preserve and showcase tangible and intangible heritage, as also stated in ICOM’s museum definition [

16]: digitizing and creating virtual replicas of physical artifacts and cultural objects ensures their preservation and accessibility.

Secondly, virtual museums provide educational opportunities by offering interactive and immersive experiences where users can learn about history, art, and other cultural topics through virtual exhibitions, videos, and interactive contents.

Furthermore, virtual museums also have the potential to increase visitors’ engagement and reach a wider audience, as they are not limited by geographical location or opening hours. VMs can overcome barriers, allowing people from all over the world to access and discover cultural heritage through a “remote visit” [

12] without the need for a physical museum, by using a media tool which appeals to a variety of visitors while promoting the ‘real sites’ [

17].

Much like their traditional counterparts, virtual museums can be created based on specific objects or themes, or they can be entirely new exhibitions. Moreover, they can be a locally distributed product, accessible on portable devices (such as smartphones or tablets), or web-based (as in the case of displaying a museum’s digital collections) [

18]. Furthermore [

19], two other concepts of VMs can be defined: the “Imaginary Museum”, which only exists through its digital internet site and digital products, and the “museum of museums”, which digitally represents various museums in a single virtual experience.

The V-Must project carried out a screening of existing VMs with the aim of identifying categories and types of virtual museums, both to ensure a semantic approach and to evaluate future developments [

19]. The eight categories identified were: content (archaeology, virtual art, etc.), interaction type (interactive/non-interactive), duration (permanent, temporary, etc.), communication style (narrative, descriptive), immersivity level (immersive, non-immersive, etc.), type of distribution (online VM, offline VM, etc.), scope (educational, entertainment, promotional, etc.), and sustainability level [

14].

The concept of VMs can be applied to different contexts and heritage, varying significantly from small scales, such as objects or buildings, to larger scales such as entire territories. This multi-scale approach gives the opportunity to consider the museum experience in an integrated manner [

20,

21], or in a targeted way [

22], depending on the audience or the specific aims.

While it is easier to identify the “limits” of objects or entities, contextualizing the territorial aspect, intended as the landscape, proves to be a complex endeavor. This complexity arises from its close connection not only to geographical boundaries but often to sociocultural, historical, and anthropological concepts, since these concepts are not always easily ascribed to a specific territorial region [

23]. In this context, virtual museums offer a remarkable flexibility and create structured museum experiences capable of bringing together distant territories linked by shared customs and traditions (i.e., intangible heritage). This strength lies in encouraging common values within a broader system, facilitating the reconnection. A virtual landscape museum requires strong connections across various fields. Thus, the distinction between real and virtual museums begins to fade, and the role of the audience becomes increasingly significant. This paradigm shift leads to a more user-centered VM, a “responsive museum” [

15], where the priority is focused on the visitor rather than the object. In some cases, they can act not only as spectators or observers, but as active contributors and generators of data and content. Geo-social tagging and geo-storytelling platforms, as discussed by [

24], are becoming increasingly popular, especially those based on ‘crowdsourcing’, which can involve users in content creation (user generated content—UGC). Experiences like Loquis or izi.TRAVEL have demonstrated how those platforms can act as catalysts for the economic and tourist revitalization of the associated territories, bringing the user to the center.

Experiences on a larger scale usually employ different types of technologies and devices. There are many examples, from websites with maps and geo-localized content [

25], to applications able to extend the in situ experience with multimedia content (audio guides, texts, videos, images) and technologies, such as augmented reality and virtual reality, widely tested for cultural heritage [

26,

27,

28]. AR technology has proved capable of enhancing the in situ experience, providing immersive and innovative museum experiences for the visitor, allowing information content to be consulted via smartphones and tablets, which are common devices. The term “phygital” has been coined to define the overlap between digital and physical experiences that these technologies create, which give added value to a visit and enable innovative storytelling [

29,

30], from exploring historical city squares [

31] to witnessing events from the past [

32], blurring the lines between history and reality.

Despite their benefits, those technologies also present different challenges. Evaluating these user experiences is essential for understanding user perceptions and interactions with the content [

33]. There are a variety of evaluation methods, from traditional questionnaires to advanced techniques like eye-tracking and usability testing. Assessing how users engage with AR content leads to design improvements, enhancing the quality of AR interactions. One invaluable tool for assessing user experiences in AR applications is the user experience questionnaire (UEQ). The UEQ is tailored to measure overall user experience, including usability, aesthetics, and emotional engagement [

34,

35]. After engaging with an AR application, users respond to carefully designed questions. Their responses offer insights into satisfaction and help to pinpoint areas to be enhanced, facilitating user-centered design for more compelling and effective AR applications.

3. Materials and Methods

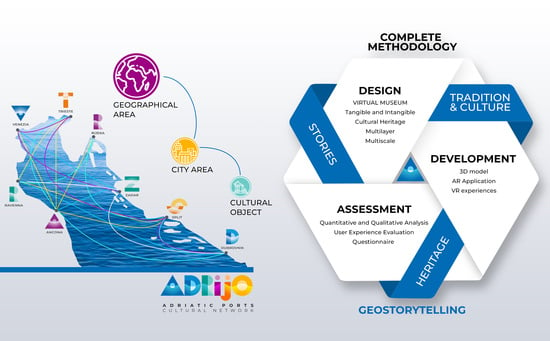

The methodology employed in this study presents the workflow of the Adrijo virtual tool, a comprehensive digital platform designed to provide different levels of engagement and cultural exploration. At its core, the Adrijo tool operates on three distinct levels, commencing with a broad overview of the eight ports, then delving into the points of interest of the Ancona VM with its multifaceted contents, and finally culminating in an augmented reality (AR) experience specifically tailored for the Arch of Trajan—a site-specific application.

The primary objective of this methodology is rooted in the creation of digital content intended for use across various platforms, including websites, geo-located mobile applications, and augmented reality applications. This approach is strategically devised to address the challenges posed by the dynamic landscape of cultural offerings, providing users with a versatile and immersive experience.

Central to the methodology is the systematic alignment of tourism and cultural enhancement objectives through digital transformation. This is facilitated by solutions that seamlessly blend top-down and bottom-up approaches, thereby offering a harmonious integration of structured planning and participatory engagement. By leveraging these approaches, our methodology not only demonstrates the technical features of the Adrijo tool but also showcases its potential to systematically address evolving cultural demands, ensuring a well-rounded and accessible digital experience for users across different platforms.

In the subsequent sections, we elucidate the specific steps and processes undertaken to achieve these objectives, offering a comprehensive understanding of the methodology employed in the development of the Adrijo virtual platform.

3.1. The First Level: A VM for the Adriatic Heritage of Ports

The REMEMBER project contributed to the improvement of the accessibility to the eight cultural heritage sites by creating a VM on a single-cloud based platform which is accessible from smartphones or tablets with or without downloading specific applications. This way, virtual tourists can also access the cultural content from remote locations, increasing the visibility of the cultural destinations. The editorial plan, an important added value, was the result of a collaboration from three main partners: the Central Adriatic Port Authority (the lead partner), the Venice Port Authority, and Università Politecnica delle Marche. It was also set up considering a taxonomy of keywords based on the partners’ suggestions, hence representing a real cooperative approach.

The Adrijo platform (

www.adrijo.eu/en, accessed on 3 February 2024) is able to promote eight cultural heritage sites which are the eight Adriatic ports in the Italian and Croatian cities of Ancona, Ravenna, Trieste, Venice, Rijeka, Dubrovnik, Zadar, and Split, five of which are UNESCO sites (Ravenna, Venice, Dubrovnik, Split, and Zadar).

One of the main strengths of the REMEMBER project is indeed the focus of a digital representation of tangible and intangible heritage though the Adrijo platform. Cultural content was made available to different types of visitors (low season, disabled, seniors). The Adriatic maritime heritage was promoted as a single destination through renovated historical port buildings and rooms for touristic purposes in Venice, Ravenna, Trieste, and Zadar; a cultural touristic itinerary was set up in both Ancona and Dubrovnik to improve the accessibility and usability of port city cultural heritage.

The Adrijo platform was set up in three languages: English, Italian, and Croatian. This increased the accessibility to the cultural content for the local, thus promoting the stories, and cultural richness of the port environment. The narrative is told through three categories (stories, traditions and cultures, and heritage) with further subcategories (

Figure 1).

The REMEMBER project helped to enhance and rediscover the cultural values and the social and economic relations that link the Italian and Croatian ports in the Adriatic and their surrounding territories, starting with the roles as “cultural hubs” traditionally played by the ports. The REMEMBER project increased knowledge and awareness about the relations that forged the cultural identity of the involved territories. This will surely strengthen the mutual understanding between ports, cities and surrounding territories contributing to the generation of added value under the social, cultural, and economic aspects. The higher level of the Adrijo platform is currently fed by more than 150 items, ranging from 3D models, panoramic images and videos, to text and images (

Figure 2).

The future sustainability of the virtual museums on the Adrijo platform is facilitated by the strong interest coming from all the project partners and the eight ports sites, even when not directly involved in the project. For example, Rijeka and Split expressed an interest to continue their experience with the REMEMBER project and to expand the Adrijo platform with more content and functionalities.

The first result coming from this interest was the port authorities’ joint decision to nominate the proposal “Adrijo—Adriatic Ports Cultural Network” for the ESPO—European Sea Port Organization—award in July 2022. The “ADRIJO—Adriatic Ports Cultural Network” proposal was shortlisted with other four proposals and came second. Moreover, the Adrijo platform was presented during the SEATRADE Cruise Med event held in Malaga and during the MEDCRUISE General Assembly in September 2022. The participation in the different initiatives is evidence that all parties demonstrated a strong commitment to continue to invest in the Adrijo platform, beyond the REMEMBER project duration and financial resources.

Transferring the Adrijo platform is going to be achieved by expanding it to other ports of the Adriatic–Ionian region and by submitting a proposal to the IPA-Adrion call, or through joint cooperation activities to be carried out within the MEDCRUISE Association framework, which has already declared the Adrijo platform a best practice to be transferred to other Mediterranean ports.

Digital technology applied in the REMEMBER project ensures durability and allows content to be updated even after the end of the project. Both the technological improvements and content consistency have recently been confirmed thanks to the financial backing of Adrijo Routes, a new Interreg IT_HR project led by the Central Adriatic Port Authority.

The VM represents a solid way of enhancing the maritime cultural heritage in the short term. However, at the same time, it will contribute to long-term sustainable development objectives in the territories, valorizing cultural and historical heritage, revitalizing local communities and their economies, and finally expanding touristic seasonality. Furthermore, the involvement of local actors and territorial entities as well as the collaboration of entrepreneurs and local populations will pave the way for the future sustainability of their outputs and results.

3.2. The Second Level: An Example of a VM for the Waterfront of Ancona

In the project “Valorization of tangible cultural heritage in Adriatic Italian and Croatian ports”, the maritime tangible cultural heritage was further valorized, by raising awareness about the characteristics of each territory, port, and museum, thanks to itineraries and installations set up at the ports. Venice designed a self-supporting double-sided totem to be installed inside the former warehouse and created an installation of a dedicated interactive wall inside the Naval Historical Museum of Venice. The description highlights the close link between the port’s past and present history, featuring places such as Venice, Marghera, and Chioggia. Trieste set up a permanent exhibition on its premises. The exhibition tour concerning the history and historical–cultural heritage of the ports of Trieste and Monfalcone is designed to “recall” the value of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage linked to its relationship with the sea. Dubrovnik focused on the old port, boat building, inland and city port relations, and the cultural heritage of the port city. It set up a permanent corner with a touch screen monitor and a Karaka ship model in the maritime museum. Zadar set up three video walls in the port of Gaženica, where artistic videos about the historical development of the port and its history and culture are continuously projected. Ravenna developed “45 points of interest” about the history and culture related to the Port of Ravenna. Rijeka focused on the history and traditions of this northern Croatian port. Split concentrated on the typical and historical boat building, the port’s history, and its subsequent industrial development and developed narratives about the island of Vis.

The core of the narratives within the scope of the REMEMBER project’s local virtual museums was the transformation of the port ecosystem. The port of Ancona is indeed characterized as a valuable hub, facilitating the coexistence of manufacturing and transformation economies, a network of tertiary services with commercial and touristic roots, cultural and creative industries, as well as specialized functions in control and security. This ecosystem is a dynamic and innovative multilevel context, a useful infrastructure that accommodates the proximity between historical–artistic and archaeological landmarks and the contemporaneity of art, architecture, business, and labor. It functions as a valuable hub, generating both material and immaterial content, as well as networking on a continental and Adriatic scale, within the broader dimensions of the macro-regional, urban, and territorial contexts.

Therefore, Ancona set up a cultural and touristic itinerary to allow locals and visitors to discover the most important and iconic sites of the port (

Figure 3). The contents are a result of multi-source contributions coming from different artists, communication and conduction companies, authors, and cultural and scientific institutions, such as Università Politecnica delle Marche, which developed 3D content and virtual and augmented reality experiences. Ten of the points of interest (PoIs) that make up the virtual route identified on the Adrijo platform correspond with the locations of the specifically built physical route marked with tourist signs.

The online visit is enriched by the on-site experience, as the platform’s PoIs are directly connected to the related places. In the same way, the on-site visit is guided, educational, and amplified through virtual content that can be enjoyed online, as well as in augmented reality mode.

The local virtual museums can fulfil their mission of representing and enhancing the cultures that define their history and perspective through storytelling using words from different languages, images, sounds, 3D models, and panoramic photos. A network of PoIs, implemented through a digital information system and designed to be accessible on different devices, will serve as guidance to comprehend the transformation of the port from a historical perspective, spanning from antiquity to the present, and to envision traces of the future (

Figure 3).

The tourist–cultural wayfinding project for the port of Ancona has established a connection to other cultural locations in Ancona by identifying the PoIs within the port area. The PoIs identified by the project are the Mandracchio fish market, the Mole Vanvitelliana, the waterfront (which includes Porta Pia and the statue of Trajan), the port of Ancona (general presentation of the PoIs of the Port, near the Adriatic Port Authority headquarter), the Portelle (S. Maria, Panunzi, Torriglioni, and Loggia), the port Captain’s House, the warehouses of the Roman port, the Arch of Trajan, the Arsenal (Corridor), and the Ancient Port.

3.3. The Third Level: The User Experience for the Arch of Trajan

Closely connected with the concept of a multi-level experience, the user is accompanied on their port area visit by a series of marked kiosks. Upon reaching the Arch of Trajan, the tourist is brought to a further level of musealization, represented by the implementation of an augmented reality application, tailor-made to narrate some features of the monument in a more engaging way.

One of the advantages of an on-site experience is that through AR a visitor can learn about the inscriptions as well as the reconstruction of the ancient friezes and decorations or listen to explanations or stories about the parts that make up the arch itself. This can guarantee an added value to the local visit compared to consulting the online VM, enhancing the overall value of the port area, often visited by tourists in transit from the ships docking there. The application, available in both Italian and English, has been developed for mobile devices and can be downloaded for Android and iOS devices from their respective stores.

Once the language has been selected, a disclaimer pops up on the homepage and it explains that the content comes from the REMEMBER project and the Adrijo portal. It is then possible to access an overview of the virtual museum of the port of Ancona, in which there is a brief description of the port and a map of the PoIs along the waterfront. From here, it is possible to delve into the section dedicated to the Trajan Arch (

Figure 4), look at the image gallery, read about the history of the arch, and finally, access the augmented reality section.

To begin the AR experience and view the contents, it is necessary to frame the image target installed at the base of the arch crepidome, used as an anchor to place the 3D content, specifically the printed representation of the arch frieze. Once the contents are placed, they will be kept aligned to the real world by tracking the device’s movements, viewing the menu aligned with the real object.

The menu presents four options:

In particular, the last section shows a reconstruction of the arch and the original decorations, which are superimposed by projecting a 3D model which highlights the decorative elements. The app was developed using the Unity engine with the functionality of AR Foundation, which in turn leverages AR Core on Android and ARKit on iOS.

Thanks to the tracking based on a combination of image target recognition and device tracking (SLAM), the app shows augmented reality content put over the Arch of Trajan, overlapping a 3D reconstruction of the whole monument over the real one, a 1:1 scale reconstruction, with optimal tracking and alignment results even when moving around the object (

Figure 5).

This type of real-scale AR is possible thanks to the perfect matching of the real object with the model used for the three-dimensional reconstruction, made through an integrated survey using laser-scanning and UAV photogrammetry techniques. Before being integrated into the mobile application, these three-dimensional objects which result from the survey must be processed to reduce the number of polygons and the computational load for the devices, while maintaining the original level of detail.

As already experimentally determined in [

36], “

The process to obtain a low poly model is similar to the production concept of the videogame 3D scene and consists in three main steps: (a) the high definition and high poly modelling, (b) the decimation and faces reduction and finally (c) the projection of the geometric characteristics from the high poly to the low poly one.”

The AR application therefore allows end users to enjoy content that would otherwise be difficult to share, making it easier to understand for different age groups, especially younger generations.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the development, implementation, and some assessment of the Adrijo digital platform: a platform specifically designed for the storytelling of Adriatic port heritage and for enabling tourism experiences leveraged by digital technologies. The Interreg project REMEMBER represented a commendable effort in the face of challenges posed by the pandemic, not only navigating the difficulties but capitalizing on the unique opportunities that emerged during this disruptive period. Serving as a noteworthy example of disseminating and presenting widespread heritage, the multi-scalar, multilayer virtual museum seamlessly integrates the systematized heritage of the Adriatic ports with historical artifacts and folk traditions, alongside the current contemporary panorama of the port life. It embraces the innovative concepts of geo-storytelling and employs different technologies (such as VR, AR, and 3D reality-based or reconstruction models) for three levels of geographical interaction: from the Adriatic area as a whole, considering the network of eight ports, to each single port-city, and finally to a specific artifact, thus enabling site-specific installations. This research showcases a forward-thinking approach to cultural representation and tourism experiences. In addition, this paper is an achievement in itself since it is a sort of tool-kit available not only for implementing virtual museums for widespread heritage but also for managing a multi-scalar approach to the values of a landscape or a tourism destination.

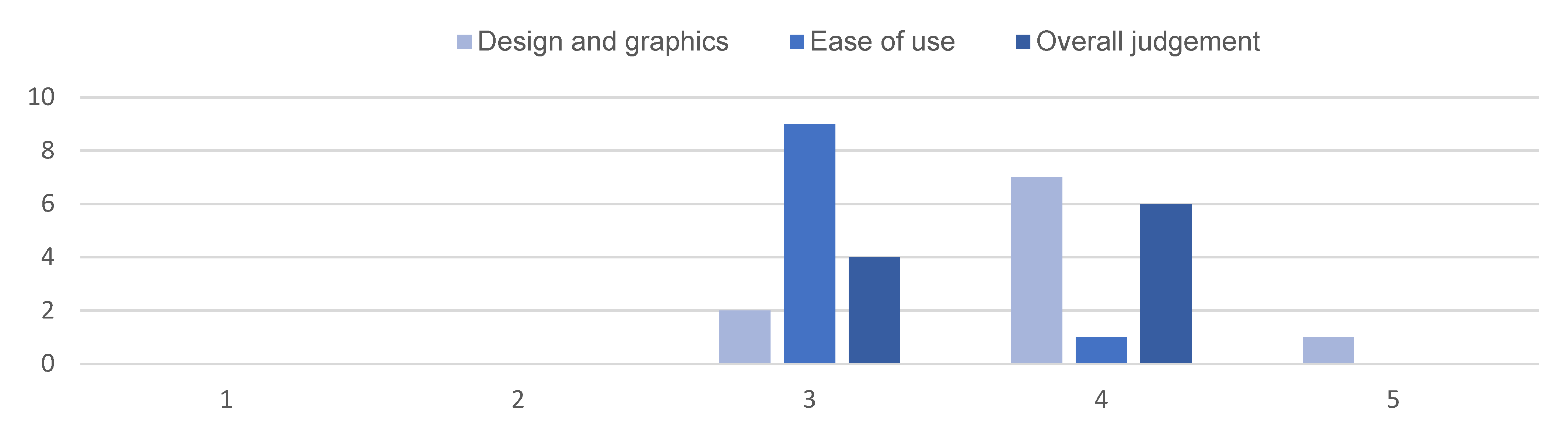

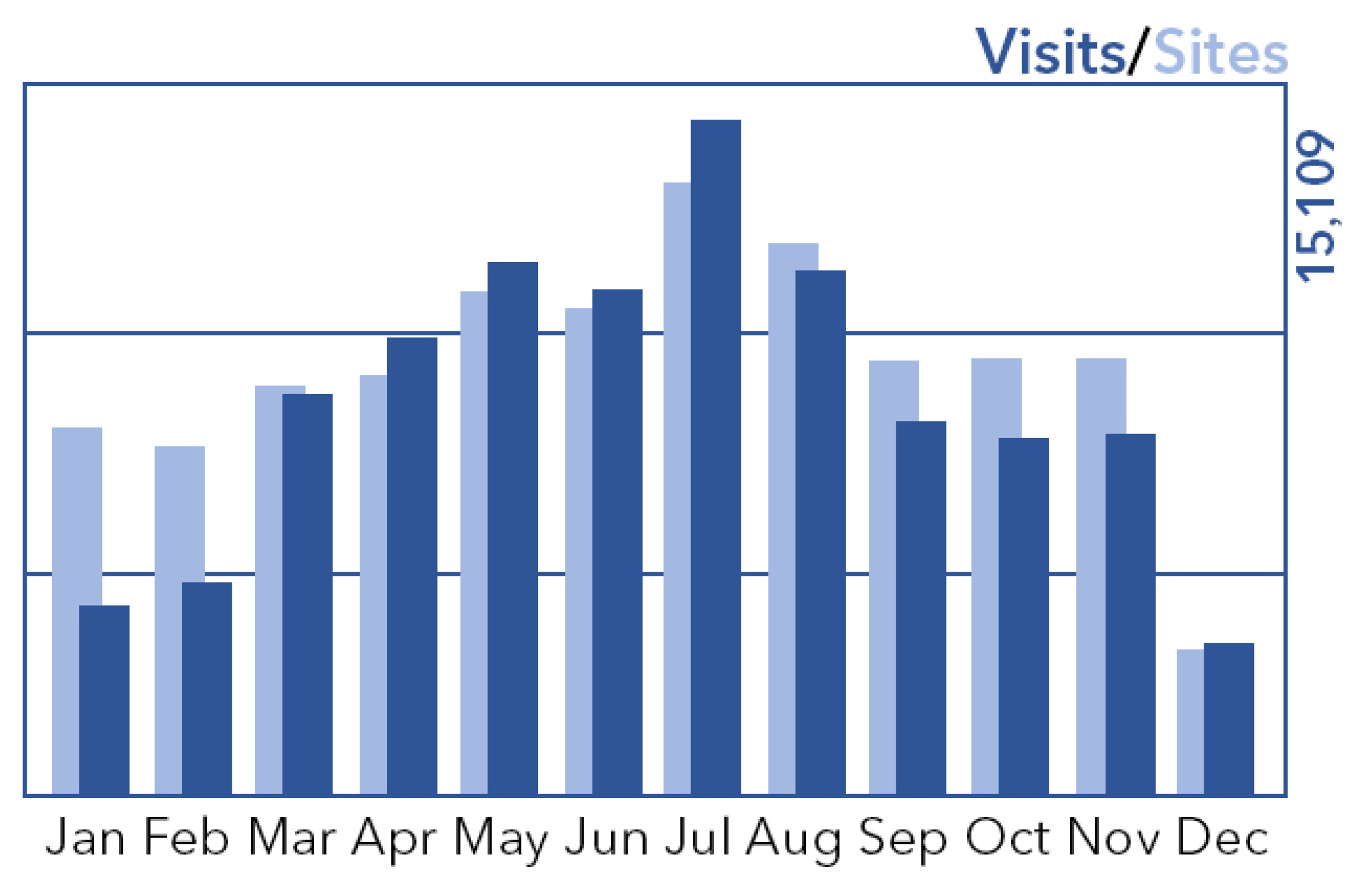

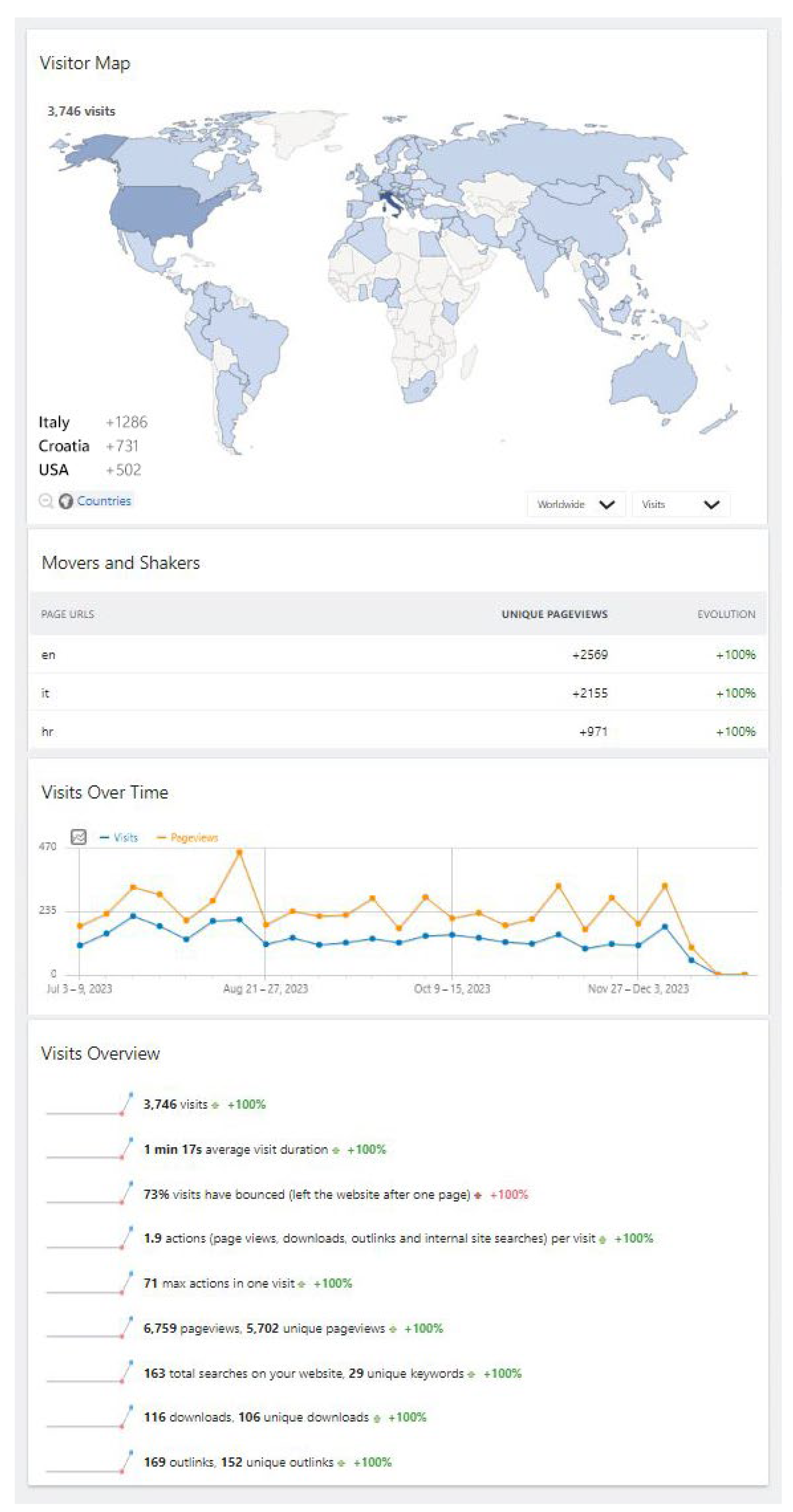

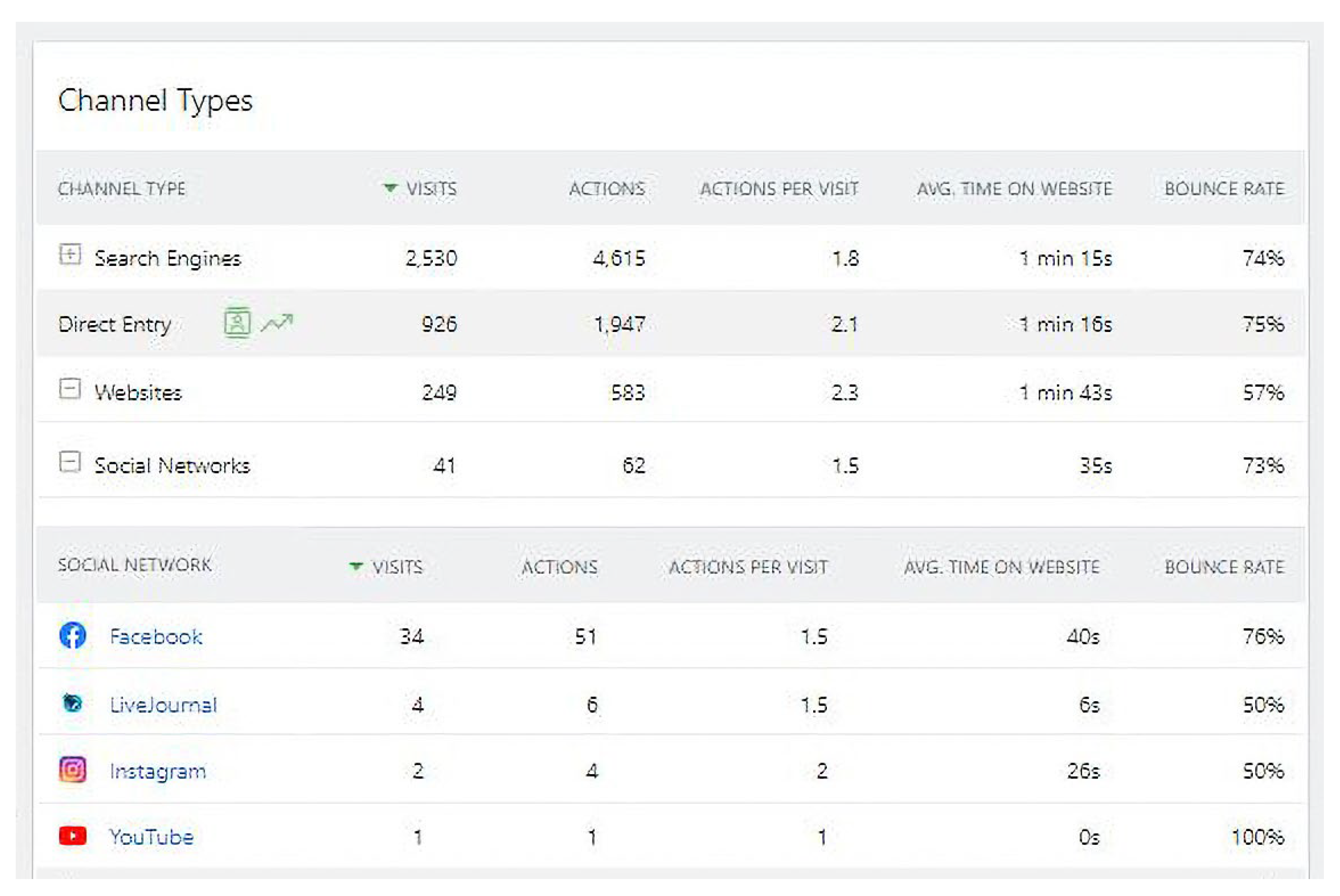

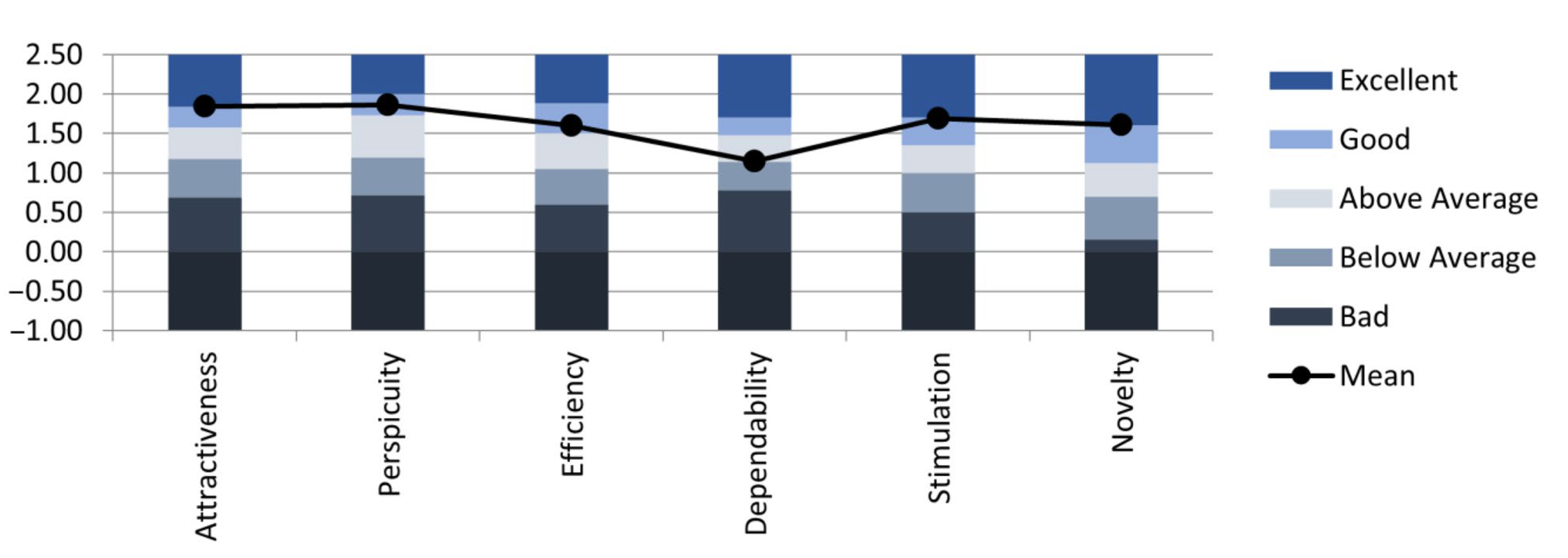

With reference to the Adrijo web platform and the Arch of Trajan AR application—presented as the two main focuses in the results section—a general appreciation of the products should be noted, especially when analyzing qualitative surveys.

The results of the usability tests indicated a consistently positive response from participants showing engagement as they interacted with the scenarios. Users demonstrated a high level of satisfaction and ease in navigating through the virtual environments or interfaces presented to them. This positive reception is indicative of the effectiveness of the Adrijo web platform and the Arch of Trajan AR application in meeting user expectations and providing a seamless and enjoyable user experience.

Finally, this work sheds light on the future need for specialized professional profiles and occupations in museums, virtual museums, and tourism. Key roles include digital experience designers specializing in immersive digital experiences, geo-storytelling experts creating location-specific narratives, virtual curators organizing digital collections, cultural technologists bridging technology and culture, and tourism experience strategists developing strategies for digital platforms. Additionally, roles like AR developers, data analysts for cultural tourism, and accessibility and inclusion specialists should be given special attention for their role in the evolving landscape of cultural heritage, technology, and tourism.

As virtual museums and tourism continue to evolve, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, these specialized occupations will likely grow in demand, reflecting the need for expertise in the area where culture, technology, and tourism meet. Interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches will be essential for successful collaboration and innovation in these domains.

In conclusion, this paper’s critical analysis of virtual museums not only sheds light on the methodologies applied but also provides reusable frameworks for implementation, comprehensive user satisfaction surveys, and an insightful examination of the strengths and weaknesses gleaned from specific experiences. As a valuable contribution to the field, especially in the post-COVID-19 scenario, this endeavor sets a foundation for future advancements in virtual museums and touristic experiences, emphasizing the adaptability required for the evolving landscape of digital heritage dissemination and communication.