Abstract

Dehesas constitute one of the most relevant and traditional landscapes of the Extremadura region. However, the supremacy given to the economic–productive functionality of agricultural territories over environmental and cultural sustainability leads to the devaluation and neglect of the heritage manifestations of the rural world. Based on this premise, this study aimed to understand the current situation of some of the traditional trades of the Extremadura pasture, assessing the benefits of their conservation and determining the possible threats that hinder their preservation. In addition, it sought to articulate a proposal for solutions aimed at safeguarding them. To this end, the Delphi method was used, and 20 experts were interviewed in depth, mainly cork and charcoal extractors. The results corroborate the existence of various problems faced by the traditional trades, which compromise the conservation of the identity of the rural population and the sustainability of the dehesa. To mitigate these tensions, it was concluded that there is a need to disseminate the heritage of the dehesa through educational and agrotourism experiences to promote an increase in tourist awareness, revalue ancestral knowledge, and contribute to the conservation of intangible assets.

1. Introduction

The dehesa is one of the most representative landscapes of the Iberian Peninsula. It covers more than 3.5 million hectares, two-thirds of which are located in Spain, while one-third is in Portugal, where it is called “montado” or “mounted” [1]. Broadly speaking, the dehesa can be understood as an agrosilvopastoral system that possesses unique characteristics that make it exclusive in the world [2]. It is a space in which man has intervened to achieve better agricultural and livestock production while maintaining the original forest use [2]. The dehesa has been defined in many ways throughout history, in some cases in an incomplete, contradictory, and even very limited way at the legislative level [3]. This complexity of definitions increases if we consider that it is not a static unit but that it changes with the evolution of societies and their adaptation to the environment [4].

The variety of meanings to refer to this concept is specified in the Dehesa Green Book, which mentions this diversity as one of the main obstacles to debate and decision-making [5]. Some sources of discussion refer to the predominant type of trees or the proportion of the farm area in which there are scattered trees in relation to treeless areas. However, this document states that “at least 50% of the area is occupied by grassland with sparse acorn-producing trees and with a fraction of the area covered between 5 and 60%” [5], p. 7.

It is worth noting the disparity in the definitions in the legislation of Extremadura and Andalusia, the two communities with the highest percentage of pasture land in the national territory, 35% and 27%, respectively [6]. In the case of Extremadura, Law 1/1986 of 2 May 1986 on the Dehesa in Extremadura [2], defines it in Article 1 as “any rustic estate in which more than one hundred hectares of its surface area is susceptible, according to its most suitable agricultural use, to extensive livestock farming” [2], p. 5. For its part, Andalusia, through Law 7/2010 of 14 July for the Dehesa [7], contemplates a more environmentalist approach since it refers to the relationship between humans and the landscape, mentioning the sustainable management of the landscape and resources as a priority objective: “The dehesa is a humanized landscape that constitutes an example of optimal coexistence of humans with the environment, a model of sustainable management in which the resources offered by nature are used without neglecting their conservation” [7], p. 1.

Broadly speaking, it has been described as a singular and appreciated type of landscape, both for its aesthetic and natural values, although the high ethnographic values it treasures are rarely recognized. In addition to its biological and landscape richness, the dehesa evokes social values and sensitivities such as respect for the environment, the quality and sustainability of the production processes or the valuation of an agricultural heritage that is not always known [8,9].

The balance that for years has defined man’s relationship with this extremely vulnerable natural environment has promoted the conservation of an exceptional landscape and a rich agricultural heritage. The harmony between the exploitation and the conservation of the attractions of the dehesa has led to its inclusion among the agrarian systems of high conservation value [10].

The pasture is associated with different elements that constitute a powerful cultural heritage [11,12]. These include living traditions, customs, traditional trades, agri-food knowledge, artisan, festive, folkloric manifestations, and even the specific vocabulary of many areas. Therefore, in addition to constituting spaces for production, agricultural landscapes are home to a wide and diverse heritage that contributes to maintaining the identity of the rural population.

Despite their extraordinary landscape and their high heritage value, these agrosystems face various threats that compromise their future. The loss of profitability of the farms, the marked reduction in human capital in the activities and trades associated with the rural world, and the aging of the population are some of the limitations that hinder the sustainable use of these areas [8,13].

In addition, the primacy given to the economic–productive functionality of agrarian territories to the detriment of their heritage value leads to a certain neglect of the cultural manifestations of the rural world. Thus begins a process of delegitimization of the culture of the countryside, which entails the neglect of its most significant properties, as well as the loss or transformation of knowledge, techniques, trades, languages, and landscapes associated with these landscapes [14].

Economic constraints, socio-demographic problems, the devaluation of agricultural heritage, and threats to the environment itself have repercussions in the current context of the crisis that the dehesa is going through [15,16]. Faced with the situation of depletion and deterioration of the environment caused by the prevailing production model, there is a need to promote an economic development model that, in addition to supporting the green, circular, and social economy, extols the existence of intangible assets associated with pasturelands. However, although these could improve the tourism potential of the territories, they are not being exploited due to lack of knowledge and disinterest [2].

Therefore, despite the importance of agricultural activity for economic development and the rich heritage of rural areas, these are not sufficient reasons to achieve territorial and sustainable development. Together with the agricultural activities that have traditionally made possible the use of the dehesa, there is an increasing commitment to complementary initiatives that allow the revaluation of some of its inherent heritage resources, from the landscape to the environmental, cultural, artistic, gastronomic, and recreational [15,17]. Agricultural heritage is currently emerging as an identity resource on which to support certain development processes [14].

Under this consideration, tourism is seen as an opportunity to revitalize local economies, as well as to value heritage manifestations. Precisely, Law 45/2007 of 13 December 2007 for the sustainable development of the rural environment, points out the promotion of rural tourism as a measure for economic diversification, mentioning agrotourism or tourism linked to agricultural activity as a means to achieve it [18]. Likewise, the Tourism Plan of Extremadura 2021–2023 coincides with these ideas, betting on ecotourism in the dehesas [19].

Agritourism, as a new alternative, reveals new approaches to sustainable rural development, as it plays an essential role in education and recreation with agrarian tasks relevant to preserving the memory of a particular society or collective [20,21,22]. It stands as an appropriate strategy to preserve the rural heritage, tangible and intangible, projecting the personal and cultural value that these resources possess for the personnel linked to agricultural tasks [23]. In addition, current demand shows a clear preference for traditional agricultural landscapes as a reflection of diverse ecological values and cultural identity, which justifies the attractiveness of the pastures [24].

The process of approaching the heritage reality in the pastures requires educational and socializing strategies that enable physical, intellectual, and affective accessibility to various manifestations [25,26,27]. Therefore, it is necessary to seek strategies for the dissemination of heritage resources with the greatest possible benefits. To this end, heritage education is defined as an essential discipline since, in addition to communicating heritage, it seeks to raise public awareness of the need to conserve it [28], for which it employs educational and interpretative actions aimed at understanding its value [29].

The main hypothesis of this study is the existence of various problems facing the dehesa. Among them, the deterioration or devaluation of its agricultural heritage stands out, especially in relation to traditional knowledge and trades, many of which are at risk of disappearing. Specifically, the reduction in the number of people engaged in cork harvesting or charcoal making is assumed, which not only affects the maintenance of the signs of identity but also the sustainability of the dehesa. Among the solutions to address some of the threats, agrotourism is suggested to disseminate, raise awareness, and educate about agrarian heritage.

The main objective of the study was to determine the current situation of the dehesa and the traditional trades associated with it. For this reason, the study is based on the opinion of the main actors involved in this area, i.e., cork harvesters and charcoal burners. The aim is to assess the benefits of its conservation, as well as to determine the possible limitations that hinder its protection. It also seeks to articulate a proposal for solutions aimed at safeguarding them. These objectives are proposed with the aim of revaluing the agrarian, social, cultural, and ethnological heritage associated with the dehesa and promoting its communication committed to education and sustainability.

1.1. The Rich Heritage of the Pastureland

The evolution of agricultural practices has generated a valuable heritage linked to the heritage of agricultural exploitation, considered in a broad sense that includes territories such as pastures, cultivated areas, or forest plantations. The cultural heritage associated with these spaces is linked to tangible assets such as buildings, infrastructures, and equipment related to the production and transformation of agricultural products, also known as agricultural monuments. It also encompasses a wide repertoire of traditions, trades, knowledge, and crafts with an ethnographic and intangible character that increases their cultural and historical relevance [14].

The dehesa possesses a large part of the values that today’s society demands from the rural environment [15]. It has extensive material and landscape values, articulated based on a multitude of balances and anthropic readaptations on which its conservation depends. In addition to its natural and landscape values, there is a rich and diverse cultural heritage, which provides identity to these areas. Agricultural exploitation offers an abundant heritage materialized in numerous examples of vernacular and traditional architecture, which can be appreciated both in customs, uses, and ancestral means of production and in constructive systems and resources resulting from human adaptation to the environment (huts, stone fences, watering troughs, zahurdas, wine presses, farmhouses, haciendas, etc.) [8]. In addition, it has a wide repertoire of traditional trades, some of which have already disappeared or are threatened.

Many of these uses and activities are in the process of extinction, so these cultural assets and manifestations are almost the only means of accessing knowledge of rural society. The changes experienced in the production systems have directly affected the conservation of the constructions, causing the abandonment, deterioration, or modification of many of them, provoking a perceptive devaluation and a patrimonial fracture [8]. In this panorama of vulnerability, it is common to find scattered and unknown architectural remains in the countryside [30].

Together with changes in production systems, the lack of recognition of agricultural properties and landscapes has contributed to a lack of knowledge that threatens agricultural heritage. The European Landscape Convention, held in Florence in 2000, represents a turning point since it recognizes the heritage, aesthetic, and identity value of all landscapes, including agricultural and rural landscapes [31]. Thus, landscapes have begun to be understood as a reflection of the nature, culture, and material and immaterial heritage of territories [32]. This contributes to the consideration of the landscape, territory, and heritage as an inseparable trinomial [33,34].

There is currently a vindication of the dehesa and its landscapes in a new socio-cultural context aimed at their preservation. This is due to the recognition of agricultural landscapes as spaces that treasure landscape, cultural, and heritage values and that, beyond agricultural exploitation, perform other functions of environmental preservation, territorial rebalancing, leisure and recreation, or education and awareness raising [14]. However, neglect and devaluation have caused serious territorial and cultural losses that must be urgently stopped [8].

To mitigate this situation, heritage tourism education is offered as an ideal strategy to maintain agricultural landscapes and to make their heritage known under different forms of exhibition and interaction situations, being the main way to disseminate the culture and values of rural populations [35,36,37]. Through educational processes, cultural participation, identity, and social exchanges are strengthened, generating an endogenous development for the protection of heritage [38].

Specifically, agrotourism, as a typology of rural tourism, integrates education and interpretation activities as distinctive factors [39]. It plays an important role in education and recreation with agrarian tasks since it allows interaction with people linked to life in the countryside or learning and participation in the tasks of the field [40]. This approach makes the recovery and revaluation of traditions, techniques, and agricultural heritage possible, which is essential to preserve the identity of a particular way of life [21,23].

Therefore, rural tourism can favor the conservation of the dehesas through the generation of agrotourism products, thus complementing the existing offer based on the exploitation of agricultural and livestock resources and promoting contact with vernacular architectural heritage and with ancestral trades such as uncorking, charcoal production, or apiculture, among others [3].

1.2. Agrotourism for the Valorization of the Agricultural Heritage and as a Complement of Income

After the 2000s, the reform of the Common Agricultural Policy introduced changes in rural development policies, generating incentives for agricultural multifunctionality and reinforcing its value as an identifying symbol of rural areas [41]. This has led to the recognition of various roles and responsibilities for farm workers, not only those related to food production but also those associated with cultural identity, the preservation of landscape values, or the mitigation of territorial imbalances [42].

As a result, new productive approaches are emerging based on activities that are transversal to agriculture, ranging from the revaluation of typical products [43] to the promotion of rural tourism [44,45]. This diversification of the economic structure favors the conversion of tourism into a potential force of attraction for rural territories [46]. It offers different perspectives of interpretation by promoting the participation of local actors, the diffusion of endogenous products, the preservation of the landscape, or the conservation of rural customs and traditions [40].

During the last decade, there has been a significant increase in the supply and demand for rural tourism, which favors the development of tourism products in non-massified destinations [40]. The inherent diversity of farms makes a wide and attractive catalog of resources that can be used for tourism possible, linked to the diversity of agricultural work, livestock techniques, or work related to forestry [15,47].

Likewise, in recent years there have been changes associated with the tastes and interests of the demand in relation to the so-called experience society, for which the offer of quality services is not enough to achieve their satisfaction. New tourists are looking for a greater component of action, participation, and interaction with the environment, authenticity, the return to cultural roots, and the enhancement of heritage [48,49,50]. The demand has begun to be interested in active and emotional experiences, seeking new learning opportunities and a variety of activities that allow contact with the history, the environment, and the culture of the population [34,39,51].

In this context, agritourism experiences respond to new customer expectations by promoting the enhancement of heritage elements through educational or recreational activities in any agricultural work environment [52]. This alternative currently offers the visitor a different experience, based mainly on learning and observing the culture of native communities [39]. In addition to its high educational component, it is environmentally responsible by allowing tourists to interact with natural spaces, enjoying and appreciating both the natural attractions and the cultural manifestations present [53].

Agritourism is positioned within the potential tourism typologies that are being developed in rural areas [39]. Its main distinctive component lies in its emphasis on the visitor’s participation and interaction with rural communities, as it includes interest in the culture of the inhabitants, the infrastructure, or the area’s gastronomy [54]. In other words, it involves considering agricultural activities not only from a productivist view of the countryside but also from a perspective that includes the social and cultural values associated with life in the countryside.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was carried out in Extremadura, an inland and peripheral region of Spain, covering an area of 41,635 km2. It is characterized by a low population density. It currently has 1,059,501 inhabitants [55], among which there is a high proportion of people over 65 years of age, 21.37% [56]. Its productive base does not differ substantially from the national structure, but its GDP is among the communities with the lowest incomes. It presents a clear predominance of the service sector, which occupies 66% of the active population and generates three-quarters of the annual GDP; the industrial sector is less developed, with 16% of the active population and 19% of the GDP, among which one-third is due to a construction subsector; finally, the agricultural sector, although with only 10% of the active population, is three times the national average and only contributes 6.4% of the GDP.

However, these socio-demographic and economic problems, together with the secular neglect of central governments to reverse the adversities, have had beneficial effects on the conservation of a natural environment in privileged conditions [3]. So much so that the region has more than 30% of its surface area protected for having extraordinary landscapes, among which are the dehesas, currently also recognized as a cultural landscape due to the extensive heritage values that it represents [57].

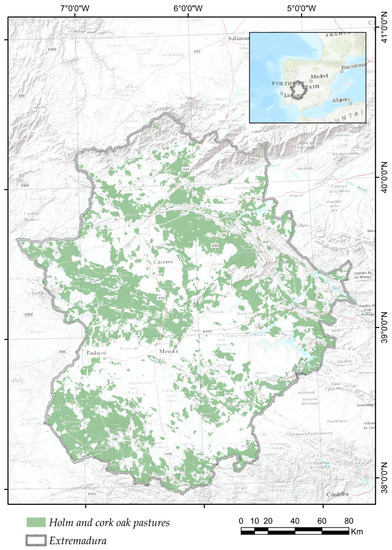

The dehesa is an agroforestry system exclusive to some areas of the Western Mediterranean, being an element of great territorial significance in the Iberian Peninsula, where it occupies large areas. Specifically, Spain is the country with the greatest extension of pasture lands, represented to a greater extent in the Extremadura region, accounting for 35% of the territory of this community [1] (IDEEx) [58]. Likewise, the dehesas overlap with numerous protected natural areas such as special conservation areas (SCA), which accumulate 82,894,917 hectares (19.9%) and special protection areas for birds (SPA), with 1,089,232 hectares (26.1%) (ING) [59] (Figure 1). Therefore, the great potential of Extremadura’s territory for carrying out this study is justified, as well as for launching initiatives to promote awareness of the importance and uniqueness of the natural and cultural heritage linked to the pasturelands.

Figure 1.

Study area. Source: Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN) [59], Infraestructura de Datos Especiales de Extremadura (IDEEx) [58].

2.2. Design and Sample

The present work focuses on the study of heritage in non-formal contexts and is therefore situated within the framework of didactic–conceptual research [60]. Specifically, it deals with some traditional crafts, which are part of the immaterial, ethnographic, and cultural heritage of Extremadura, assessing the causes that hinder its preservation. For this purpose, a qualitative methodology is used, based on a Delphi analysis conducted in two rounds [61,62]. Its usefulness is based on understanding the opportunities offered by these intangible assets for local territories [63,64,65].

Considering the spatial delimitation of the work, the objective of the analyses is not to establish generalizations but to achieve a more exhaustive understanding of the phenomenon and to delve into questions related to the experiences, feelings, and desires of the participants [66,67]. The qualitative design also allows the interpretation of the perceptions and intentions of interviewees, considering subjectivity and intersubjectivity as a source of richness. In addition, it highlights the reflective and interpretative methodological approach and the analyses reducible to the exact context in which the information is produced, based on the interaction with expert participants.

For the selection of the sample, the discriminating criterion was to have good knowledge and experience in traditional trades carried out in the dehesa. More specifically, the study was limited to cork harvesting and charcoal production. The study involved 20 experts who carry out trades related to agricultural tasks in the Extremadura countryside (Table 1).

Table 1.

Panel of experts.

They are mainly cork tappers and charcoal burners with extensive experience who have undergone transitions in the traditional production practices of their trades. The sample also includes other participants linked to forestry management, business, and tourism communication, who have also experienced traditional trades but who now have a different professional situation. This diversity makes it possible to obtain different views on the state of conservation and dissemination of ancestral knowledge and practices.

2.3. Instruments and Techniques

Delphi analysis is a group communication process that allows a complex problem to be dealt with through the participation of a group of experts without the need for personal interaction between them [68,69]. Its purpose is to seek a certain consensus in the opinions concerning the problems under analysis [70]. This method takes advantage of the synergies of group discussion and eliminates the constraints of group interactions, such as hierarchical influences, systematic noise, and possible pressure towards conformity [71]. Reaching consensus is therefore obtained by aggregating individual judgments [72].

Considering its variants, the present study contemplates a decisional Delphi and expert meeting since its application is aimed at understanding a territorial and social reality, with the objective of offering decisions oriented to improve this reality through the contributions of experts [73]. In this case, its purpose is to articulate different measures that allow preserving traditional crafts and knowledge and projecting them as potential identity heritage resources. To this end, in-depth interviews were conducted with each of the participants. This is made up of six thematic blocks that determine its structure (Table 2).

Table 2.

Structure of the interview.

The interviews were recorded with the consent of the participants, whose anonymity was guaranteed. The interviews were conducted in the experts’ usual place of work, so they took place in San Vicente de Alcántara, but also in Zahínos, Alconchel, Moraleja, and Mérida.

From the transcriptions, the most significant segments of information were recovered and coded into analyzable units [74]. This recovery and coding process generated several categories defined by some common features or elements. In this process, the most relevant phenomena were identified, examples were collected, and similarities, differences, patterns, and structures were found [75].

From the initial categories, several subcategories were generated and used to segment and analyze the ideas and concerns of the interviewees, which required searching for fragments in the text as evidence of the selected codes. Thus, additional information was added until reaching theoretical saturation. Finally, the process was concluded with the configuration of a scheme of categories–subcategories, resulting from the analysis of all the interviews.

3. Results

The results reveal the reality perceived by the experts at the end of the two Delphi rounds. Aspects related to the benefits derived from maintaining traditional trades are included. The study also considers the limitations that hinder their conservation and the consequences of their extinction. Likewise, we sought to understand the possible solutions that could be proposed to mitigate the threat to these ancestral practices. Other personal questions were also considered to obtain a deeper knowledge of traditional practices based on the use of cork oak and the changes experienced over the years in the production systems and the way of life associated with them.

For each of the variables mentioned above, a system of categories–subcategories was defined to facilitate the analysis and interpretation of the results. The categorized elements are distributed in tables ordered according to the degree of consensus reached by the participants, represented by percentages (F).

3.1. Profile of the Experts

Broadly speaking, the profile of the experts was determined by the fact that they were mainly men between 40 and 50 years of age, dedicated to agricultural activities since the age of 16, and with a basic level of education. Their link to agricultural work was determined by a strong family influence, although it should be noted that, in most cases, their children did not desire to continue with this legacy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Profile of experts.

Family tradition is a very influential factor in the preservation of traditional trades. Most experts affirm that their initiation in these agricultural practices is driven by the family nucleus, with their parents usually being the ones from whom they learned the trade. Some interviewees even stated the following: “I have experienced some things with my father, who was also my friend and taught me values such as effort and love for the countryside”. However, it is striking that many of the family descendants of the participants do not wish to continue to work in jobs linked to the rural world, which could pose a threat to the continuity of these trades.

3.2. Technological Transformations and Changes in the Way of Life

After the interviews with the experts, numerous transformations were detected, both in the process of cork extraction and transformation, as well as in the elaboration of charcoal, which has led to changes in the lifestyles associated with these activities. Likewise, the experience of the cork extractors and charcoal makers entails specific knowledge, often necessary for the cork corking and charcoal-making processes. This includes the recognition of a lexicon related to the different types of cork, depending on the quality or different parts of the tree (bornizo, segundero, corcho de reproducción, zapata, canuto), to specific procedures in the techniques of cork extraction (palanquear) and care of the ovens (hurgonero, encañar), to ancestral traditions (jato, jatera, aguao, boliche, chozo), or associated with different trades linked to this practice, with many of them already being extinct (sacador, juntador, arriero, apilador, aguador, ranchero) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Examples of vocabulary related to the traditional trades.

3.2.1. Main Transformations in the Cork Sector

- (a)

- Extraction process and technological changes

Corking is a process that takes place every 9 years in Extremadura, as specified by the Directorate of Forestry Policy of the Regional Government of Extremadura (in Decree 134/2019, of 3 September, which regulates the implementation of certain forestry activities in the Autonomous Community of Extremadura and the Registers of Cooperatives, Companies and Forest Industries, and Protective Forests of Extremadura), while in other communities it can be extended to 10 years. It begins on 1 August and ends on 31 August, although this activity may be brought forward due to the high temperatures experienced in the community. Based on the contributions of the experts, the current extraction process could be summarized as follows: (1) use of an axe to make different cuts and extract the cork. (2) Arrival of the necessary machinery to collect the cork and pile it up. (3) Transport to the factory. (4) Resting and stacking the cork for six months to straighten the cork plates. (5) Cooking in a boiler for one hour and resting for several days. (6) Process of selection according to quality and caliber. (7) Manipulation, preparation, and transformation for its later commercialization.

However, this process has undergone several changes. In relation to transport, it is worth mentioning that in the past, donkeys were used to transport the cork during harvesting; although these are still used, they are currently only utilized in mountainous areas where tractors cannot access. In this line, they point out that “in the past they used to make vereas, a narrow road for the beasts to pass”. On other occasions, cork bales were transported with a wheelbarrow, while nowadays, they always use machinery. The corking day ended when the corkscrew extracted the canute; that is, a uniform and perimeter piece of cork. This was “a demonstration of the crew’s skill”.

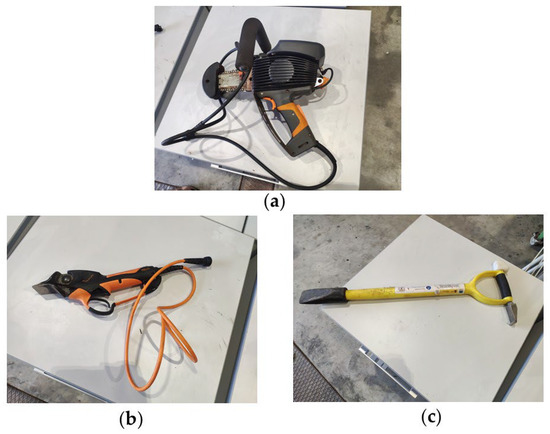

One of the most relevant changes is due to the introduction of new tools for cork extraction (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

New tools designed for cork harvesting: (a) electric chainsaw; (b) electric cork tongs; (c) technological lever for cork removal. Source: Tools provided by the Center for Scientific and Technological Research of Extremadura (CICYTEX).

Among them, a small chainsaw has been developed that, according to the experts, does not require as much experience, as it is easier to use than an axe and involves fewer risks, both for the operator and the tree itself (Figure 3). In conclusion, they state that this tool “is more careful with the tree and less dangerous for people. It is easier to learn to use than the axe. With the axe, the operator had to have dexterity, experience and strength. In addition, the depth and caliber had to be calculated briefly, and there are many blows to the tree. The less caliber it has, the more damage you can do to the tree”.

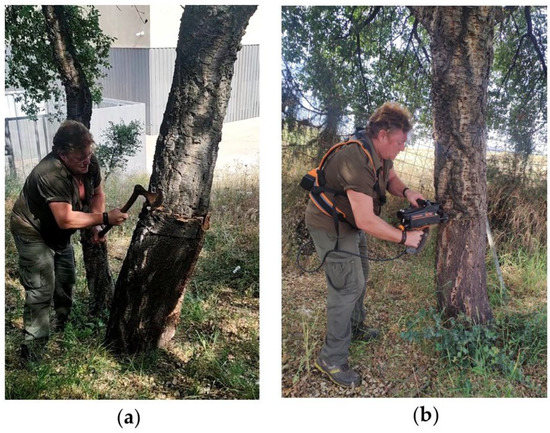

Figure 3.

Changes in the uncorking process: (a) traditional uncorking method; (b) modern uncorking method. Source: authors based on the cork removal work carried out by a cork puller from CICYTEX.

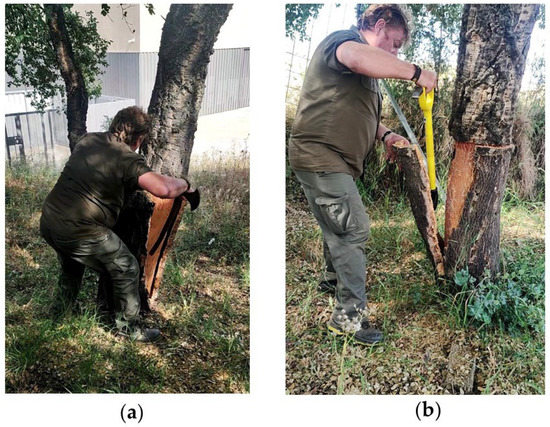

It is also worth mentioning the introduction of new tools similar to the burgee or crowbar used in the process of detaching the cork from the mother layer (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in the cork detachment process: (a) traditional extraction method; (b) modern extraction method. Source: authors based on the cork stripping work carried out by a cork puller from CICYTEX.

The firing process has also undergone changes that, through mechanization, benefit productivity and reduce the risk of accidents (Figure 5). In this regard, it is argued that “in the past, it was lowered by hand, with the help of two workers who had to slide a large plate by means of chains, with the consequent effort and the added risk of falling into the boiler. Today the boilers are the same as they were 50 years ago, but now a mechanized hydraulic system is used”.

Figure 5.

Actual cork firing process.

Finally, the sorting process in the factory has also been modernized since the selection, preparation, and choice of material was always carried out by hand until a few years ago. As a result, experts point out that “now twice as much is produced. More cork is extracted and transformed in a day than before in a week”.

- (b)

- Cultural transformations

The most significant losses associated with the work of sacadors are especially related to the way of life that characterized them until approximately 20 years ago.

This hard and peculiar life is corroborated by statements made in this sense, going so far as to enunciate that “they would go to the countryside for a month and a half or whatever the bosses told us to take out the cork. We had to make the jato, which consisted of the luggage with the shawl, the trivet, the pans, the stews, the food, etc.”.

There they made their bed, known as jatera, using cork oak branches, a broom, and a shawl. To keep food out of reach of animals, they used freshly taken corks, which hung from the cork oak under which they had the jatera. In the morning, the ranchero would prepare the aguao and chickpea stew for lunchtime. In addition, they also brought a chair, a table, and some utensils for washing clothes.

These ancestral traditions have disappeared, as experts recognize when they say that “people used to stay in the countryside to sleep under a tree, then they would ask the owner for a room in the farmhouse and now they go back home”.

As for apprenticeships in different trades of the cuadrilla, they usually began as water carriers or ranchers. They start as apprentices from an early age, for two or three years, taking advantage of the breaks in the day to experience any process related to cork removal. During those breaks, they recall, “they would take 5 min to eat a sandwich and 10 min to learn by watching what the others were doing. They were taught all the processes and you were trained with the experience”. They also state that “that is no longer done”.

It was a temporary job, so once the cork harvest was finished, they would go to the grape harvest, then to the apple harvest, and finally, they would return to pruning during the winter. They also undertook other agricultural work, as many of them were shearers or engaged in other tasks such as olive harvesting, cleaning farms, or reforesting trees. They agree that they had “seasonal jobs”. When cork could not be harvested, they “pruned the oaks, built fences with wire fences or chose to pick olives”. They recall that their life “was like a wheel that changed every season. They were also in charge of cleaning farms, weeding, sowing and all kinds of work related to the countryside”.

3.2.2. Main Changes in the Coal Sector

- (a)

- Manufacturing process and technological changes

As experts point out, the felling process begins in October and ends on 28 February. The felling is mainly of holm oaks but also of cork oaks, eucalyptus, or olive trees and is carried out again at around 14 years of age. Once felling is finished, the process of collecting the firewood begins, and it is then left to rest until the maximum possible amount of moisture is extracted from it in the open air. Subsequently, from March to May, the wood begins to be fired to make the ovens, where the firewood is cooked for 10 days in winter and 7 in summer.

The main transformation is due to structural changes in the ovens, which were previously made with earth and straw and were maintained for a month or a month and a half. Currently, masonry, brick, and concrete ovens are used. As with cork, the transfer of firewood has also undergone numerous changes, as it was previously carried out with the help of mules or donkeys, while now machinery such as tractors are used.

- (b)

- Cultural transformations

The notorious cultural transformations are related to the ancestral way of life that characterized the charcoal burners. They lived in the countryside, where they spent 4 or 5 months sheltering in a hut. To keep the water fresh and the food in good condition, they made a hole inside the hut that they filled with water and where they introduced a pitcher. The charcoal burners were consulted to provide a good account of this and stated that “the cooler was a clay pot that was placed in a hole inside the hut”.

The contact with nature was constant, which nurtured their learning, both of the environment and trade and social values. Some say that “they slept 4 or 5 months in the hut or on a trailer, under the light of the stars and accompanied by their father”. Although they qualify to illustrate the change in life and their progress that “they already have a house, with a bed and other comforts, but in a certain way they yearn for the previous lifestyle”. During that time, “they covered the ovens with earth and watched the combustion daily, opening holes at the top, with a stick that was called hurgonero, making an attack, or closing them when necessary”.

3.3. Benefits of Preserving Traditional Trades

Experts identify several benefits derived from maintaining traditional trades and knowledge, including economic, environmental, sociocultural, educational, and recreational benefits (Table 5).

Table 5.

Benefits derived from the conservation of traditional crafts.

Several economic benefits stand out related to the growth of the local economy and the commercialization of exclusive products and services derived from natural resources: decoration, restoration, domestic uses, and handicrafts. The environmental benefits also stand out, related to the knowledge of the dehesa and its natural heritage and the projection of ecological values aimed at its conservation. The following statement stands out: “It gives value to the pasture and you understand that you have to take care of it because it is a scarce asset. It is a special way of connecting with the countryside”.

In addition, the contribution of traditional trades to sustainable development is mentioned since they are a clear example of a sustainable economy that generates economic benefits through a sustainable use of the cork oak grove, respectful of its environment and the tree itself. In fact, one interviewee stated: “We remove the waste, bring in the dead trees, do the necessary felling, prepare the oaks and cork oaks and clean the pasture. In addition, anything goes with cork and charcoal, everything is used”.

Although, to a lesser extent, other advantages are also recognized. These include sociocultural advantages, which refer to the concept of traditional knowledge and ancestral ways of life as symbols of identity of the native populations; educational advantages, which emphasize teaching through experience, intergenerational knowledge and experiences in direct contact with nature; recreational advantages, which emphasize activities in a natural environment and the creation of groups and “cuadrillas”. Proof of this is the statement made by one of the experts: “The groups have always been people who knew each other from the village, close friends and relatives who formed a good working group that we enjoyed”.

3.4. Causes Interfering in the Loss of Traditional Trades

Based on the results, there are several problems that interfere with the progressive loss of traditional trades. Among them, the decrease in the labor force is mentioned as the main cause, for which there is absolute consensus. Other causes are also mentioned, such as the need for previous experience, which does not currently exist, the lack of knowledge and devaluation of practices associated with the rural environment, replacement by modern technologies, economic supremacy over identity and cultural revaluation, the lack of dissemination of the importance of these traditional trades and networking, the instability of the cork and charcoal market, the decrease in the quantity and quality of raw material and the restrictions, and lack of economic support from the administrations (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors contributing to the loss of traditional professions.

The decrease in the labor force is the main problem that threatens the conservation of this intangible heritage because of generational replacement or the perceived lack of profitability. Perhaps, the statement “when there are generational changes, everything is lost. It is very hard work for the money it gives” summarizes the thinking of the main actors. In addition, it requires previous experience linked to family inheritance, learned over the years, which avoids bad practices that cause damage to the trees. As the experts state, “it is a trade that has to be learned over a long period of time. Normally these are people with families who have worked in the field. They have to come from a previous generation; you can’t motivate someone who has never seen it or grown up in it.”

Disconnection from the rural world is reflected in a lack of knowledge and depreciation of rural practices, which is also one of the main threats. The experts assume that there is a lack of knowledge about agricultural activity in formal education, possibly accompanied by certain prejudices associated with rural life. They go so far as to state categorically that “it is associated with illiterate people. There is a lot of ignorance; it is thought that we are destroying the countryside and we are very much singled out as responsible for the negative impacts that appear in the countryside”. It is also striking that they recognize the lack of training in these tasks. They affirm that “there is nothing that really trains in this” while recognizing that “we have an enormous wealth that we do not value nor know how to take advantage of. People do not know the values that lie behind it, how the countryside is cared for, what it means or how resources are transformed”. More specifically, they warn about the risk involved in the continuity of the traditional trades associated with the dehesa. In this sense, they affirm that “there are fewer and fewer charcoal burners, pruners, and sackers, as a result of the fact that young people do not want to learn. There is little desire to teach and little desire to learn”. Moreover, they argue that “an attempt was made to hold a training course and only two or three people signed up”.

On the other hand, new technological advances have benefits that allow for greater productivity, ease of use, and lower risk for trees and specialist personnel. However, they also imply a transformation of traditional trades and the ancestral practices and customs associated with them. A clear example of this is the modification of tools for cork extraction or the substitution of traditional ovens, as well as the reduction in the number of women in the selection process, a task currently carried out by specific machinery.

Other limitations refer to economic supremacy over identity and culture since economic interests are more important than the educational values associated with these practices. They argue that “nobody wants to learn this profession”, explaining that when they look for people to train them in these trades, the first thing they ask about is the salary, not caring about their ability to learn. Faced with this situation, they reflect on the value of their work, stating that “they cannot hire a person who does not know the trade well, since what they are interested in is that the work is well done. They conclude that “the main interest is to produce a lot”, recognizing that “that is the mentality, there is no other”.

Likewise, there is a lack of networking, justified by the scarce collaboration between companies and the administration, favoring a competitive approach that does not benefit entrepreneurs linked to this sector or new apprentices. Moreover, they recognize that “now there is no partnership in the business, there are only people who care about making more money. This situation contrasts with what happened before when they did not ask for anything in return”. They conclude that “right now the owners do not want apprentices, but someone has to learn to give continuity to the trade”.

On the other hand, the instability of the cork and coal market causes uncertainty among workers and questions about the continuity of temporary jobs. This is especially due to the rapid development of other industries that have installed, in recent decades, large, technologically advanced establishments that have a great command of the sector, making it difficult to maintain other smaller companies.

This is compounded by the decrease in the quantity and quality of raw material due to the scarcity of rainfall, the aging of trees, and the transformation of the environment caused by human beings, as well as the restrictions and demands of the administrations, whose economic support is not sufficient to meet the existing demands. An important concern refers to climate change with all that it entails in a Mediterranean environment, where extreme phenomena are becoming more acute. In this sense, they state that “right now drought is a serious problem”. They go on to explain that “since 1985 the thickness of the cork has decreased”. In addition, they state that “now the areas are very much intervened and are suffering from bad practices, pruning or inadequate cork harvesting”. They also regret that “the competent administrations do nothing, despite the fact that the trees are very old”.

3.5. Consequences Derived from the Loss of Traditional Occupations

The loss of traditional trades entails serious environmental, cultural, economic, and social losses and transformations (Table 7).

Table 7.

Consequences of the loss of traditional professions.

Experts point out the lack of knowledge of the dehesa and cork oak grove, the values they represent, and the neglect of the dehesa and farms as the main consequences of the disappearance of traditional trades. It also entails the possibility of carrying out bad practices towards the trees due to the scarcity of experienced people since it requires a learning process that is not currently carried out with sufficient efficiency.

Additionally, the cultural loss associated with the impairment of intangible values is insignificant. These include practices, customs, traditions, folklore, lexicon, and ancestral ways of life, which contribute to the loss of identity of populations.

The experts also point to economic consequences related to the loss of income and the decrease in the number of companies. They estimate that “there are about 30 companies left, although when they started working, decades ago, there were more than 70”. At the same time, they describe that “90% are family businesses and of small size, with 5 workers on average”. On the other hand, they state that gender inequality is increasing since “the female workforce in the companies is decreasing, with the consequent masculinization of the sector”.

3.6. Possible Solutions to Safeguard Traditional Professions

The solutions proposed by the interviewees can be used as possible future strategies focused on preserving traditional trades and knowledge (Table 8).

Table 8.

Proposed solutions for safeguarding traditional professions.

Fundamentally, education stands out as the main strategy to mitigate or reverse the situation of the progressive extinction of hereditary agricultural practices. They mention the need to integrate formal education aimed at raising awareness, sensitizing, and giving value to the traditional trades linked to the rural world, starting in schools and promoting a real approach to the trade, appreciating its emotional, cultural, ethnographic, symbolic, and identity value. They believe that “it is necessary to motivate people from the emotional point of view. They advocate telling them that they can work in a niche that allows them to enjoy nature, appreciate biodiversity, take care of the vegetation and know that they are contributing to sustainability”. Moreover, considering the current training gaps, they support the suitability of allowing apprentices on farms, promoting a more collaborative approach between companies and other sectors of society.

Other strategies include the dissemination of experiences and campaigns for the knowledge and valorization of trades, the promotion of agrotourism experiences that allow direct contact with nature, and increased communication with the administration, as well as with entrepreneurs and other agents linked to the rural environment.

3.7. Considerations on Agrotourism

Of all those interviewed, 70% consider the integration of agricultural activity with agritourism to be positive, valuing it as a very favorable option to contribute to the knowledge of the rural environment and agricultural heritage. Despite considering that agritourism could be a favorable future option, 85% do not collaborate with any tourism company or carry out any activity linked to this sector. Despite this, some of them recognize that in certain cases, “it has been proposed to them, although they have always refused, arguing that they lose work time”. They clarify that “they could do it occasionally, but not continuously, since they must organize the company, emphasizing economic profitability when they argue that they need to earn money and not lose it”. Moreover, they recognize that “people ask for it, but we do not make any profit”.

The supremacy of economic benefits over the dissemination of educational and cultural values is clear, although the latter aspects are also considered by some experts. Perhaps this attitude is due, on the one hand, to the fact that there is a significant lack of knowledge about the potential of tourism to improve economic income. On the other hand, there is little interest in disseminating ancestral trades and ways of life, although some recognize that “they would not mind having another form of business if there was a mentality of teaching what is ours and of collaboration”.

On the other hand, 15% of the interviewees who link their activity with tourism do so through contact with the interpretation center or visits to the Cork, Wood, and Charcoal Institute (CICYTEX). However, they do not promote or disseminate these services, but rather these are improvised and sporadic visits.

4. Discussion

The dehesa is a cultural landscape located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula. It constitutes an unrepeatable mosaic of great anthropological and natural richness, characterized by a unique heritage and a quality environment that offers the possibility of carrying out various activities in a unique landscape.

Extremadura has a surface area of pastures that reaches 35% of its total territory, which justifies the representativeness of this landscape in the community. Although it has herbaceous and shrub strata, the woodland is the true protagonist of the dehesa, composed mainly of species of the Quercus genus. It is mainly composed of holm oaks (quercus ilex) and cork oaks (quercus suber), which account for 29.89% of the surface area [3]. This forest wealth offers numerous possibilities for silvicultural exploitation in relation to obtaining natural products such as cork, firewood, or charcoal.

The inadequate adaptation of the dehesa to developmental models has allowed it to maintain an excellent state of conservation, preserving values that are in great demand: unique landscapes, quality products, biodiversity, environmental richness, and cultural tradition [8]. Thus, it constitutes a space in which ancestral practices, traditions, and knowledge are still maintained, forming an immaterial heritage of great value and at serious risk of disappearing.

The conservation of traditional crafts brings economic, environmental, socio-cultural, educational, and recreational benefits. Among these benefits, the panel of experts consulted mainly recognized the educational activities. Its promotion makes possible the growth of the local economy through the emergence of a first and second-transformation industry that, in the case of towns such as San Vicente de Alcántara, represents a large percentage of the cork industry at an international level [76]. Together with this, the projection of customs and traditions is established as a mechanism to achieve better economic exploitation of the areas if their tourist potential is considered [2].

Likewise, other environmental benefits provided by traditional occupations should not go unnoticed due to their influence on the conservation of the dehesa. These pasturelands favor biodiversity, contribute to the absorption of CO2, prevent soil erosion, regulate water systems, and prevent the spread of forest fires [77].

Likewise, the socio-cultural, educational, and recreational values derived from the maintenance of traditional trades stand out, relevant for disseminating the symbolic and identity value associated with these landscapes, as well as for promoting learning and significant experiences through direct contact with the rural world [37]. Living cultural traditions, ancestral knowledge, and expressions contribute to different aspects of local development and provide meaning and identity to the localities [78].

Although various advantages are listed, the passing of time has led to changes in the technical, social, cultural, and economic conditions and, consequently, in the working methods that characterized the way of life of the territories. These reasons explain why the dehesa has not experienced conditions of stability and sustainability [15].

The results of the present study reaffirm this idea, revealing the existence of various problems that threaten the survival of traditional agricultural trades and activities, thus confirming the starting hypothesis of the present study. These include the decrease in the labor force linked to generational replacement and the lack of experience that this causes; the lack of knowledge, disinterest, and devaluation of rural practices, largely due to the lack of interested educational models on these issues; the replacement of traditional techniques and tools by new technologies; the greater valuation of the economic benefits over the cultural and educational values associated with these trades; the lack of networking; the instability of the cork and charcoal market; the decrease in the quality and quantity of raw material, which leads to an aging tree stock; the restrictions and demands of the administrations.

The loss of profitability of farms, together with other threats such as the physical severity of these trades, is causing an abandonment of traditional activities in the sector, provoking a lack of interest in the new generations towards this knowledge and generating an increase in agricultural unemployment. The persistence in the biological degradation of the dehesas proves that the efforts of the market and the governmental policies do not attend to their adequate conservation in spite of the competitive profitability of these territories [79]. The economic difficulties, the socio-demographic problems linked to them, and the threats to the environment distance this landscape from economic and social sustainability. This reaffirms the difficult balance between the conservation of the landscape and its economic exploitation, and consequently, there is a risk of deterioration, wear and tear, and devaluation of its rich heritage [15].

In this context of fragility, the preservation of the ancient trades of the pasture is a difficult challenge to achieve. The lack of knowledge of the pasture and its representativeness as part of the natural and cultural heritage of the populations often becomes a threat to its preservation [8].

In addition to the above, the study of the dehesa from a patrimonial perspective is very unusual since there is a clear supremacy of its economic–productive functionality [14,49,80] to the detriment of the cultural and educational representation of this type of landscape. Likewise, the operators who work in agricultural tasks are not valuing the capacity of the heritage to produce direct economic gains, which leads to the progressive dissociation of agricultural practice with its associated cultural values [23].

In short, the reasons for giving up traditional trades are varied and include precarious wages, prejudices associated with these practices, the seasonality of the work, insecurity in the face of market fluctuations, and disinterest, among other aspects. The devaluation of rural practices is motivated, in large part, by the scarce and even practically non-existent educational and training models interested in ancestral knowledge and trades. In addition, the prevailing economic models relegate ethnographic and identity issues related to the way of life associated with these practices to the background. All of this leads to a lack of awareness of the heritage value of the pasturelands, projected in the progressive abandonment and deterioration of tangible and intangible manifestations that are increasingly less present and less considered.

Considering the crisis that traditional trades are going through, experts have articulated several solutions to safeguard them. Among them, they are committed to promoting educational strategies from formal education and at different levels so as to promote a real approach to the different trades and to favor awareness of their emotional, cultural, ethnographic, symbolic, and identity value [15,76].

Article 180 of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the Convention for the Protection of the Intangible Cultural Heritage [81] defends this idea, encouraging the dissemination of intangibles in programs of formal and non-formal education systems.

Specifically, heritage education is articulated as a proposal to contribute to the preservation of ancestral trades and practices insofar as its aims are to raise awareness and sensitize both the local population and visitors to the need to conserve heritage assets, for which it uses educational actions aimed at their valuation [35,82].

Other proposals highlight the importance of promoting collaboration and networking among the different agents and social actors linked to the rural world. The objective is to enhance the value of the pastureland landscapes and their social, cultural, and ethnological heritage, making their uniqueness known [49,83,84]. Cooperation between natural spaces, museums, interpretation centers, tourist companies, and rural agents is advocated in order to share experiences and disseminate the dehesa and its heritage as a sign of identity. This would contribute to its social and touristic valuation and, with this, consolidate new economic opportunities that improve the quality of life in these territories and mitigate the threats to which traditional practices are subjected [76].

Likewise, it is important to consider the dehesa as a natural example of a cultural landscape [85], which could be used as a resource to promote rural tourism [86] so that the inhabitants can obtain higher incomes than those generated exclusively from agriculture or livestock farming. Opting for economic diversification through tourism contributes to the construction of a sustainable management model for these spaces [87]. It makes it possible to reconcile agricultural interests with environmental protection while spreading values related to the preservation of tangible and intangible heritage, as well as the conservation of an ancestral form of exploitation beneficial to any ecosystem [88]. Thus, despite the significance of agricultural activity in rural territories, it is not sufficient for rural development, and it is necessary to focus on the diversification of activities [46].

The heritage of rural areas is inseparable from their identity and history, which is why its revaluation should be part of rural development policies [40]. In addition, demand is beginning to take an interest in the offer of experiences rich in emotions, which allow direct contact with the culture, history, and environment of the populations [51]. This new type of tourist is looking for new forms of learning opportunities, as well as the enjoyment that the environment can provide [34,39].

This is why new products are emerging, ancestral methods are being revalued, and experiences based on relational and emotional contact with the destinations are being promoted. Specifically, agritourism, as a type of rural tourism, responds to the new demands of tourists, enabling the recovery and revaluation of traditions, techniques, and agricultural heritage through the offer of educational activities in any type of agricultural work environment [52].

An example of this could be the experiences linked to live demonstrations of certain ancestral practices and their cultural heritage. If they are well articulated with their geographical, scenic, and cultural environment, they can become a potential attraction, with the capacity to generate tourist flows that are not negligible [89,90]. In addition, the offer of recreational activities preserves the family heritage, transfers traditional knowledge to new generations, and makes it possible to maintain the ancestral intangible heritage [91].

This is the case of the cultural work of the woodland, such as cork harvesting or the traditional manufacture of charcoal, which are original and specific to the dehesa, have ample educational possibilities and can be attractive to visitors [15]. Likewise, the dehesa has other resources that can also be offered to visitors, and that would allow for greater diversification, such as bird watching, the collection of wild products, gastronomic activities, visits to vineyards and wineries, culinary art workshops, knowledge of elements of rural architecture, beekeeping activities, and visits to farms of agricultural production.

However, although there are ample references to the capacity of Extremadura’s dehesas to promote tourism development, there is still no use to be made of them in this sense [3,92]. The results of the present study consolidate this idea since, even though many experts consider positive the dissemination of agrotourism activities to contribute to the knowledge of the agrarian heritage, 85% of those interviewed do not collaborate with any tourism company or carry out any activity linked to this sector.

Despite the great potential of dehesas, the possible uses of agroforestry systems beyond their conception as places linked to food production or the transformation of natural resources are not known [93]. Thus, their economic exploitation is often related to the generation of natural products emanating from them, without valuing the potential of intangibles as resources of great educational, heritage, and tourism value for these rural areas [27,94].

In short, it is essential to make traditional practices and trades known because, as experts point out, the mechanization of practices and the lack of generational replacement are causing not only changes in ways of life and work but also the extinction of the lexicon and ancestral knowledge. It is especially interesting for those rural areas that still preserve the agricultural tradition and its ancestral practices, as they form a living ecomuseum ideal for tourists to visit and experience the traditional work [3].

The process of detecting and selecting experts was complex and is perhaps conditioned to a broader opinion of the actors of traditional trades. In addition, entrepreneurs and other stakeholders make up less weight in the sample. However, this apparent imbalance was diluted by the fact that they were able to reach a consensus on generalized opinions.

Despite the good results obtained, other more important questions remain open to us. Therefore, in the future, we will extend the research to a wider area, present in Portugal and Andalusia, with the aim of finding out if there are differences between the two territories.

5. Conclusions

The dehesa lays the foundations of an extraordinary landscape, appreciated both for its natural characteristics and for the cultural and ethnographic values it treasures. In addition to the socio-economic benefits it provides, its contribution to the maintenance of the rural population’s own signs of identity has been noted, as it possesses a broad heritage linked to the traditions, trades, customs, folklore, crafts, gastronomy, and specific vocabulary of the territories.

However, it is concluded that there are several problems that interfere with the progressive loss of the traditional trade representative of the dehesa. The loss of profitability of the farms, the lack of generational replacement, the devaluation of rural practices, and the introduction of new technologies have meant modifications and threats to working methods have characterized the way of life of the territories.

Considering the threats to which traditional crafts and knowledge are subjected, the proposed solutions devised by the experts are very useful in contributing to their preservation. As a priority aspect, they point out the need to promote heritage education that favors a real approach to the trade and that promotes didactic strategies that contribute to the appreciation of the emotional, cultural, ethnographic, and identity value of the agricultural heritage of the pastures.

They are also committed to the promotion of tourism activities that allow direct contact with nature. Specifically, agritourism practices are consolidated as an ideal instrument for the conservation and enhancement of natural and cultural resources, as they contribute to disseminating and valuing traditional knowledge and practices as a source of identity and wealth. It also makes it possible to take advantage of agricultural activities in a holistic manner, considering not only the productivity aspect of the countryside but also projecting the social and cultural values of production systems and traditional trades.

In short, it has been proven that it is possible to contribute to the sustainable development of the dehesa, considering its educational and tourist potential and taking its environment, culture, and traditions as a reference. Therefore, the attractiveness of the territory and its resources is a necessary but not sufficient condition for rural development. It is essential to understand the unique heritage of the dehesa as a didactic resource and tourist experiences as learning laboratories, ideal for promoting an increase in tourist awareness, contributing to the conservation of intangible assets, strengthening the links between visitors and rural areas, and encouraging the appreciation of ancestral knowledge.

However, despite recognizing the advantages of agrotourism for the knowledge of the rural environment and agricultural heritage, it is noted that the integration of tourism with the intangible cultural heritage resources and local culture is deficient. Together with the agricultural activities that have traditionally allowed the integral use of the dehesa, it is considered advisable to initiate new tourism practices that allow the valorization of its heritage resources. This would not only provide the dehesa with complementary income but would also contribute to the conservation of a heritage that is currently under serious threat.

What this study intends to emphasize is not so much the socio-economic implications of the dehesa, but rather the need to value its environmental, historical, cultural, recreational, and educational implications as a way of increasing the possibilities of contributing to its sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; methodology, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; validation, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; validation, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; formal analysis, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; investigation, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; resources, R.G.-P.; research, R.G.-P.; resources, R.G.-P.; data curation, R.G.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.-P.; writing—review and editing, R.G.-P., A.M.H.-C. and J.M.S.-M.; supervision, A.M.H.-C.; project administration, J.M.S.-M.; funding acquisition, J.M.S.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of the research conducted during the execution of the project “Agritourism in the dehesas of Extremadura: an opportunity to increase agricultural incomes and the fixation of the population in rural areas”, and its code number is IB20012. This research was funded by the Consejería de Economía, Ciencia y Agenda Digital de la Junta de Extremadura (the branch of the regional government that covers the Economy, Science and Digital Agenda of the Regional Government of Extremadura), and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF); it was also funded by the University of Extremadura and by the European Union, through the “Ayudas Margarita Salas para la Formación de Jóvenes Doctores”. Reference MS-8.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the collaboration of the stakeholders interviewed, including the charcoal makers, the corkmen, the businessmen, and the CICYTEX employees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Junta de Extremadura. Manual Del Estado de Conservación Del Hábitat de Dehesas En Extremadura. 2021. Available online: http://extremambiente.juntaex.es/files/2021/Prodehesa/MANUAL%20ESP.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Rangel, J.F.; Parejo, F.M.; Faísca, C.M.; Bombico, S. La Dehesa y El Montado En El Debate Académico. Una Visión Desde La Historia Económica. História E Econ. 2018, 21, 15–29. Available online: https://www.historiaeeconomia.pt/index.php/he/article/view/168 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Sánchez-Martín, J.M.; Blas-Morato, R.; Rengifo-Gallego, J.I. The Dehesas of Extremadura, Spain: A Potential for Socio-Economic Development Based on Agritourism Activities. Forests 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, J.M. Dehesas y Paisajes Adehesados En Castilla y León. Polygons. Rev. Geogr. 2011, 21, 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, F.; Picardo, A.; Campos, P.; Carranza, J.; Coleto, J.; Díaz, M.; Diéguez, E.; Escudero, A.; Ezquerra, F.J.; López, L.; et al. Libro Verde de La Dehesa; Consejería de Medio Ambiente, Junta Castilla La Mancha: Castilla La Mancha, Spain, 2010; Available online: https://pfcyl.es/sites/default/files/eventos/adjuntos/libroverdedeladehesa.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Junta de Andalucía. Plan Director de Las Dehesas de Andalucía. 2021. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/sites/default/files/2021-06/171103_PDDehesas_Documento_vCMAOT.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Law 7/2010, of July 14, for La Dehesa. BOE No. 193, 10 August 2010. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2010/BOE-A-2010-12891-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Silva, M.R.; Fernández, V. Claves Para El Reconocimiento de La Dehesa Como “Paisaje Cultural” de Unesco. Ann. Geogr. 2015, 35, 121–142. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5578874 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Díaz, M.C.; Lozano, P.J. The Dehesa Landscapes of the Province of Ciudad Real. Characterization and Biogeographic Valuation through the LANBIOEVA Methodology. Cuad. Geográficos 2017, 56, 187–206. Available online: https://revistaseug.ugr.es/index.php/cuadgeo/article/view/5305 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Acosta, R.; Guzmán, J.R. The Spanish Pasture: History, Conceptualization and Social Image. CULTIVAR-Cad. De Análise E Prospetiva 2020, 21, 1–22. Available online: https://www.gpp.pt/images/GPP/O_que_disponibilizamos/Publicacoes/CULTIVAR_21/Seccao_I_4_Artigo_AcostaGuzman_ES.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Rodríguez, M.D.C. The Cork Removal: A Shared Activity. Cuad. Los Amigos Los Mus. Osuna 2016, 18, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Rosillo, J.F.; Alías, M.A.; Sánchez, A.; Guillén, F. Los Conocimientos y Usos Tradicionales de La Geodiversidad En España: Situación Actual, Legislación e Inventario. Geotemas 2022, 19, 101–104. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8600309 (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Berrocal, F. Paisajes patrimoniales. Keys to Sustainable Development. El Hinojal. MUVI J. Stud. 2017, 9, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R. Hacia Una Valoración Patrimonial de La Agricultura. Scr. Nova 2008, 12, 275. Available online: https://raco.cat/index.php/ScriptaNova/article/view/120173 (accessed on 2 April 2023).

- Pérez, A.; Rengifo, J.I.; Leco, F. El Agroturismo: Un Complemento Para La Maltrecha Economía de La Dehesa. In Turismo e Innovación: VI Jornadas de Investigación En Turismo; Jiménez, J.L., Ed.; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2013; pp. 409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, A. La Dehesa: A Landscape in Agony? Rev. De Estud. Extrem. 2015, 71, 569–604. [Google Scholar]

- Hortelano, L.A.; Azofra, E.; Martín, M.I.; Izquierdo, J.I. Patrimonio Cultural y Turismo En Torno al Cerdo Ibérico En Salamanca. Cuad. Tur. 2019, 44, 193–2018. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/404811 (accessed on 20 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Law 45/2007, of 13 December 13 2007, For The Sustainable Development Of The Rural Environment. BOE No. 299, of 14/12/2007. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/12/13/45/con (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Regional Government of Extremadura. Tourism Plan of Extremadura 2021–2023. Estrategia de Turismo Sostenible de Extremadura 2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.ugtextremadura.org/sites/www.ugtextremadura.org/files/estrategia_2030_ii_plan_turistico_extremadura_2021-2023.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Sánchez, J.M.; Gurría, J.L.; Leco, F.; Pérez, M.N. SIG Para El Desarrollo Turístico En Los Espacios Rurales de Extremadura. Estud. Geográficos 2001, 62, 335–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandth, B.; Haugen, M.S. Farm Diversification into Tourism–Implications for Social Identity? J. Rural. Stud. 2011, 27, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.I.R.; Sánchez-Martín, J.M. The Assessment of the Tourism Potential of the Tagus International Nature Reserve Landscapes Using Methods Based on the Opinion of the Demand. Land 2022, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPan, C.; Barbieri, C. The Role of Agritourism in Heritage Preservation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidegain, Í.; López-Santiago, C.A.; González, J.A.; Martínez-Sastre, R.; Ravera, F.; Cerda, C. Social Valuation of Mediterranean Cultural Landscapes: Exploring Landscape Preferences and Ecosystem Services Perceptions through a Visual Approach. Land 2020, 9, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamarina, B. From Education to Heritage Interpretation: Heritage, Interpretation and Anthropology. In Patrimonios Culturales: Educación e Interpretación: Cruzando Límites y Produciendo Alternativas; Pereiro, X., Prado, S., Takenaka, H., Eds.; Ankulegi: San Sebastián, Spain, 2008; pp. 39–56. ISBN 9788469149645. [Google Scholar]

- Señorán, J.M. Patrimonio y Comunidad: El Proyecto de La Dehesa de Montehermoso. TEJUELO. Didact. Lang. Literature. Educ. 2014, 19, 143–153. Available online: https://mascvuex.unex.es/revistas/index.php/tejuelo/article/view/2569 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Fernández, M.I.; Rangel, N. La Dehesa Extremeña. A Didactic Resource. Vegas Altas Hist. J. 2018, 12, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Geovan, D.; Baptista, L.; Cardozo, P. Education, Restoration and Tourism: A Dialectical Reflection Applied to the Headquarters of the Forest Farm (Irati, Brazil). Stud. Perspect. Tour. 2017, 26, 441–460. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=180750377011 (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Fontal, O.; Vallés, J. Much More Than… Expanding Horizons for Heritage Education. In Patrimonios Migrantes; Huerta, R., De La Calle, R., Eds.; Servei de Publicacions: Valencia, Spain, 2013; pp. 149–158. ISBN 978-84-370-9011-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, A.N. Cortijos y Casas de Campo En Las Dehesas Del Término de Cáceres. In La Arquitectura Vernácula: Patrimonio de la Humanidad: Asociación Por la Arquitectura Rural Tradicional de Extremadura; Martín, J.L., Ed.; Diputación Provincial de Badajoz: Badajoz, Spain, 2006; pp. 1063–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention. Florence. 2000. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/ai/2000/10/20/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Rössler, M. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes: A UNESCO Flagship Programme 1992–2006. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvado, J. Wine Culture, Territory/Landscape and Tourism, the Enotourism Key Pillars: How to Get Business Success and Territorial Sustainability inside Tourism Ecosystem? In A Pathway for the New Generation of Tourism Research: Proceedings of the EATSA Conference, Coimbra, Portugal, 26–30 June 2016; EATSA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2016; pp. 391–414. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11328/1628 (accessed on 2 April 2023).