Specific Design Approach of Croatian Architect Dinko Kovačić: The Coexistence of Modernism and Tradition in the Second Half of the 20th Century

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Architect Dinko Kovačić’s Professional Background

3. Motive for the Research and Methodology

4. Analysis of Selected Buildings by Architect Dinko Kovačić

4.1. Ljubićeva Street in Split 3

4.2. Marjanović-Popović Semi-Detached House in Meje, Split

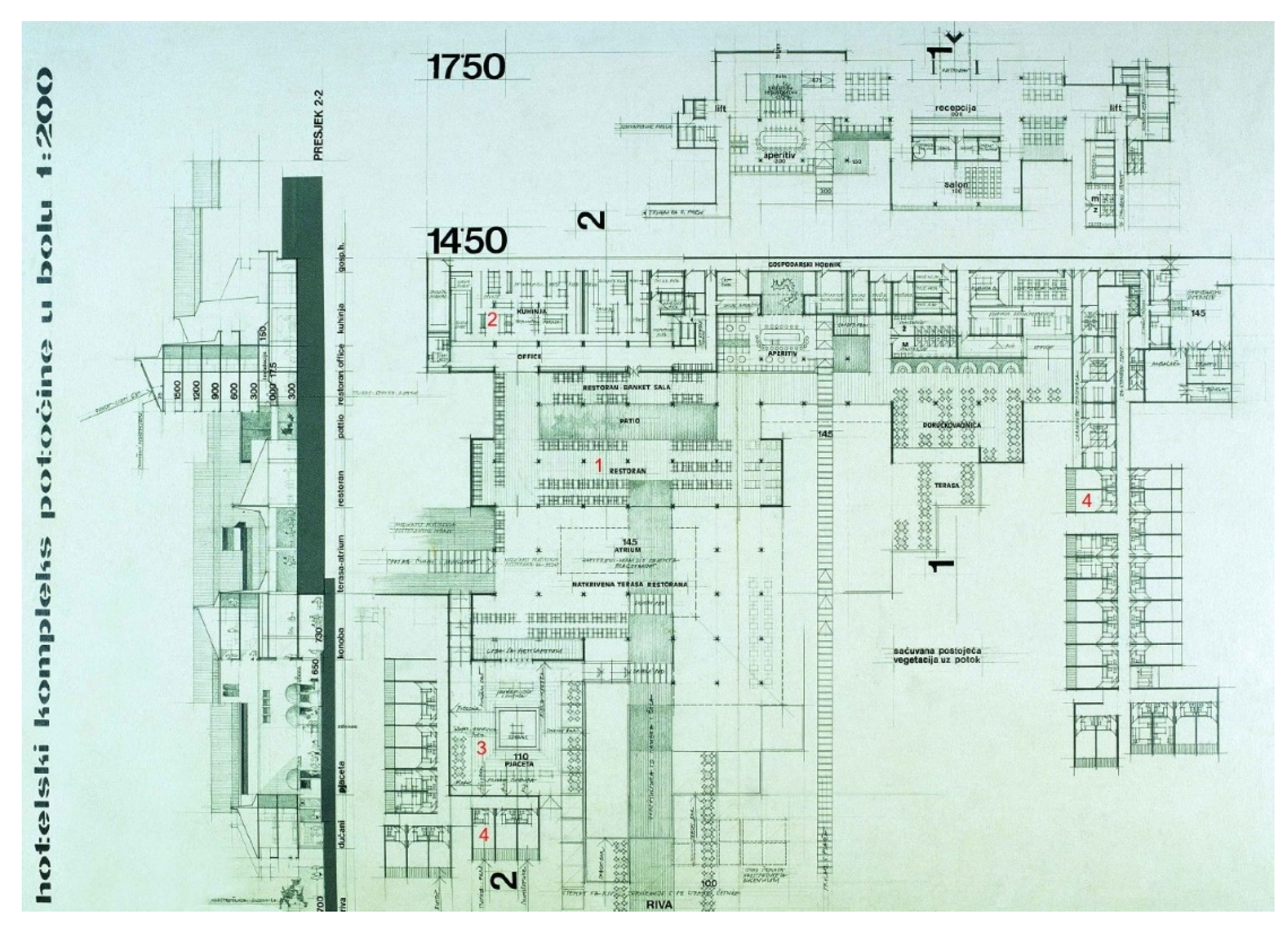

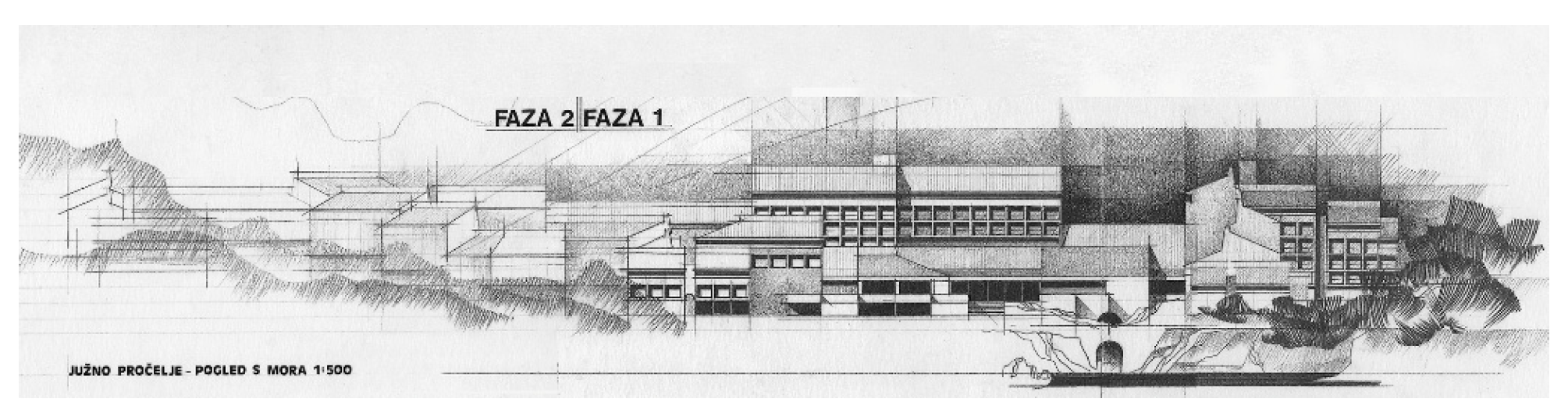

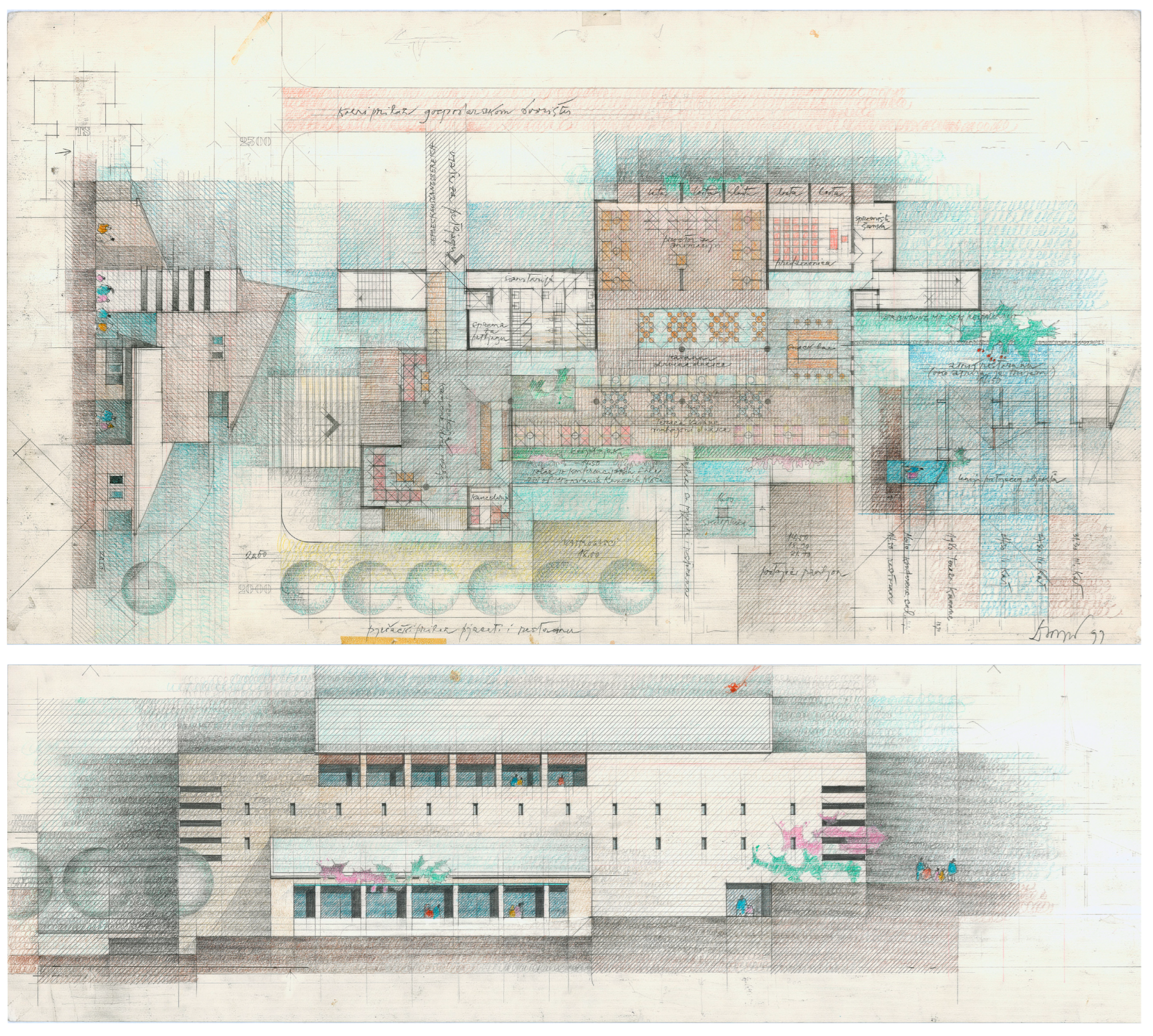

4.3. Bretanide Hotel in Bol on Brač

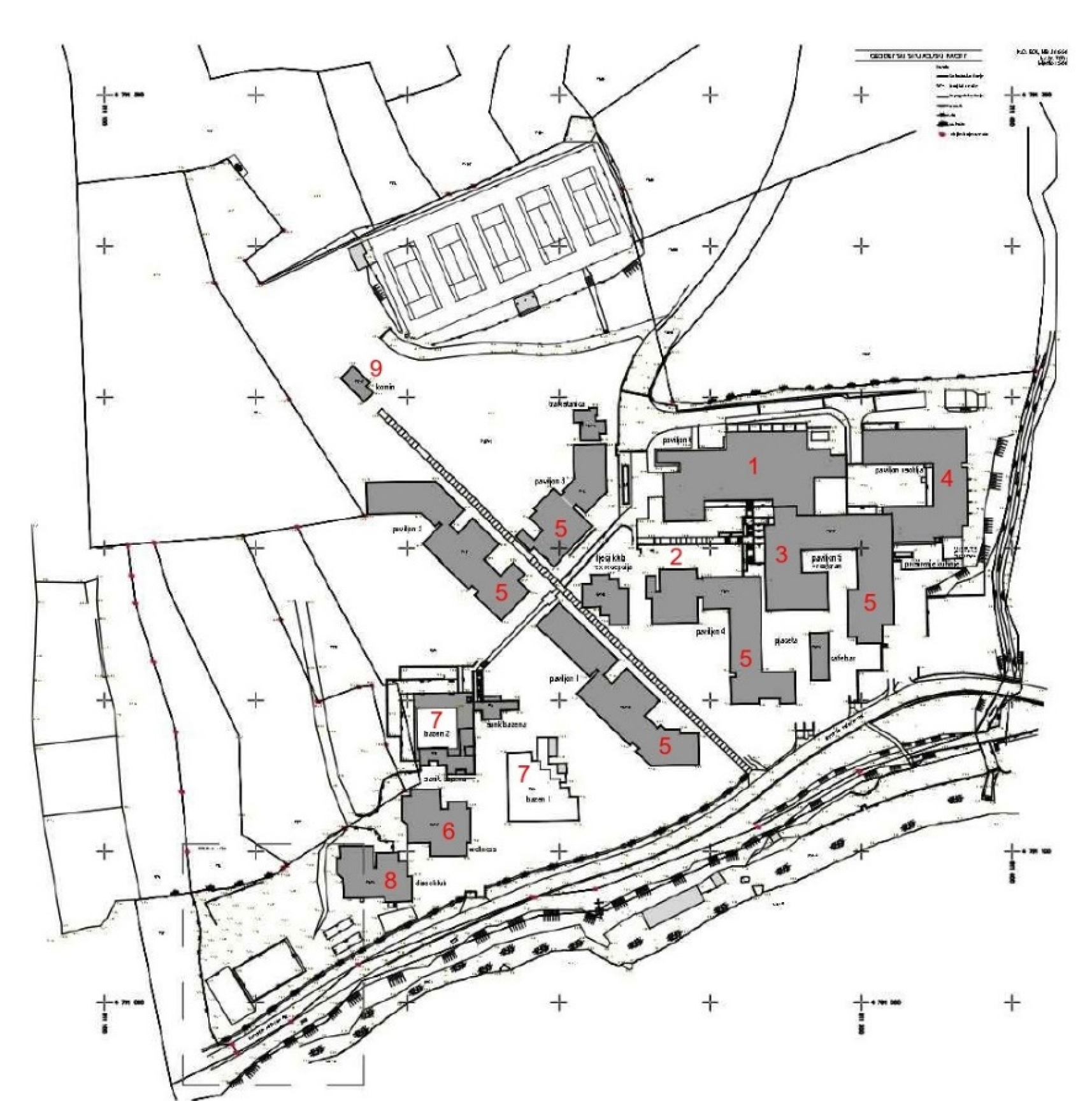

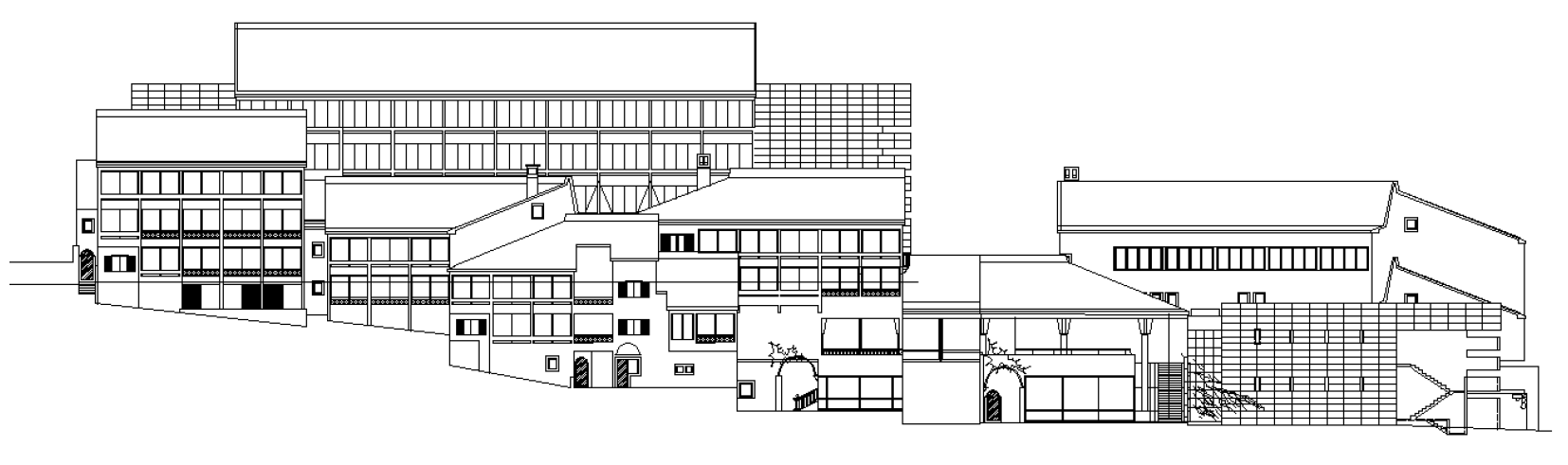

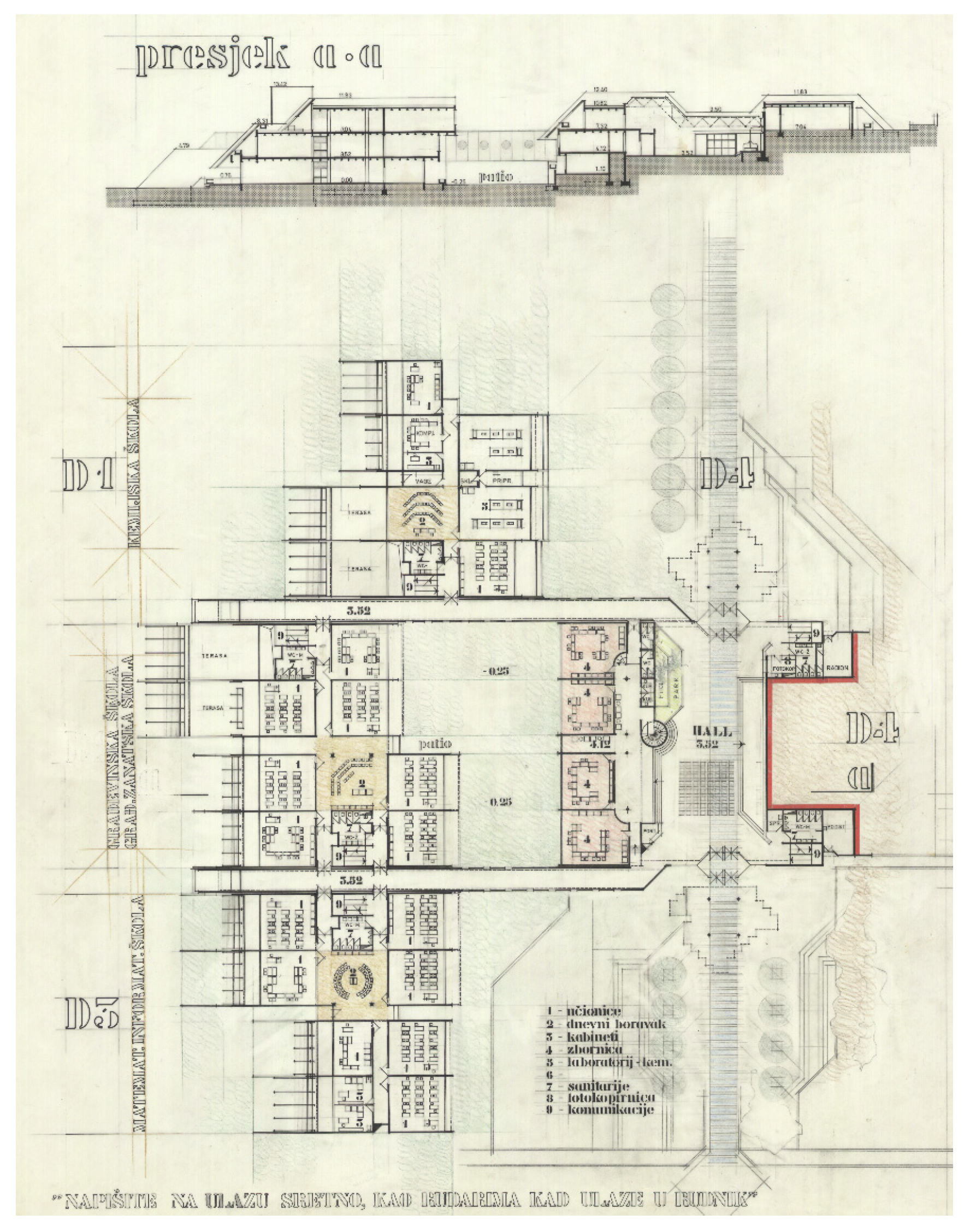

4.4. Secondary School Centre in Split 3

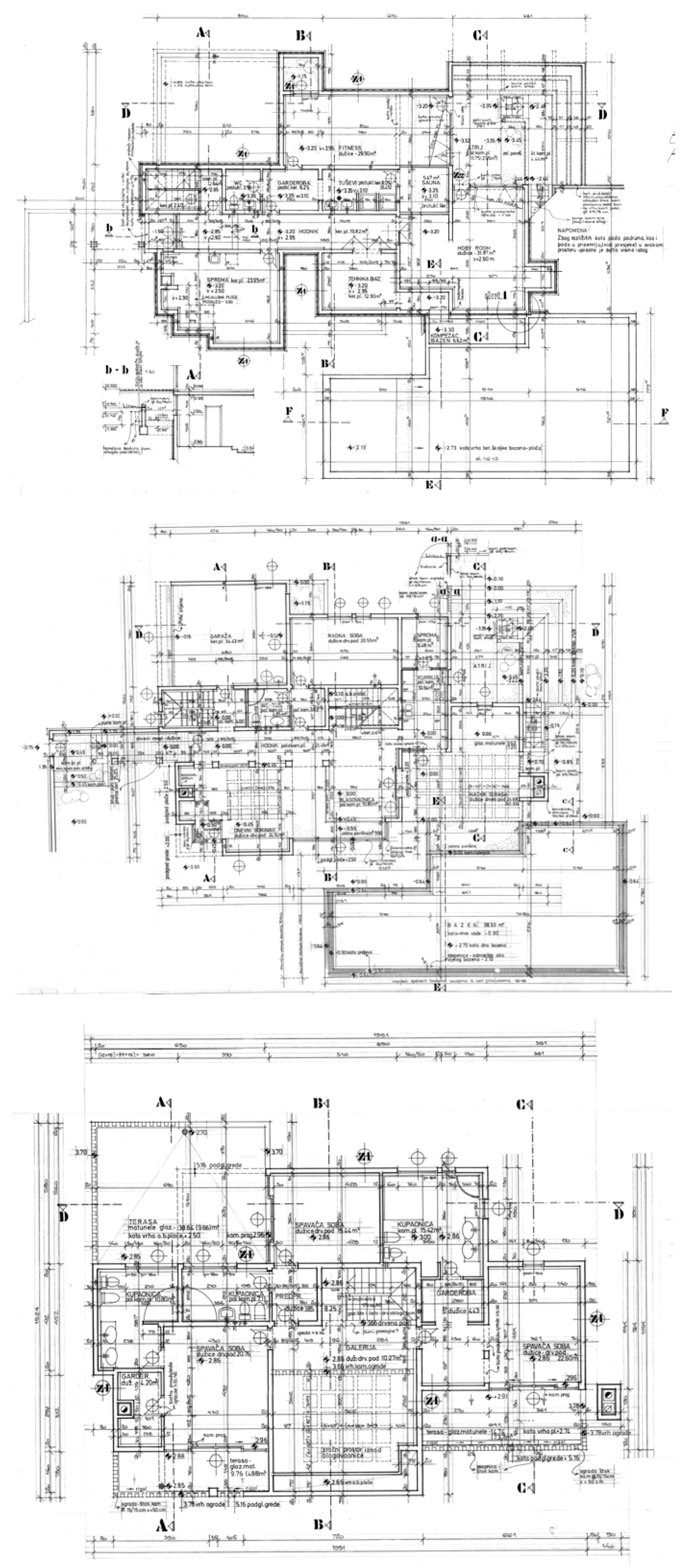

4.5. Stupalo Family House in Meje, Split

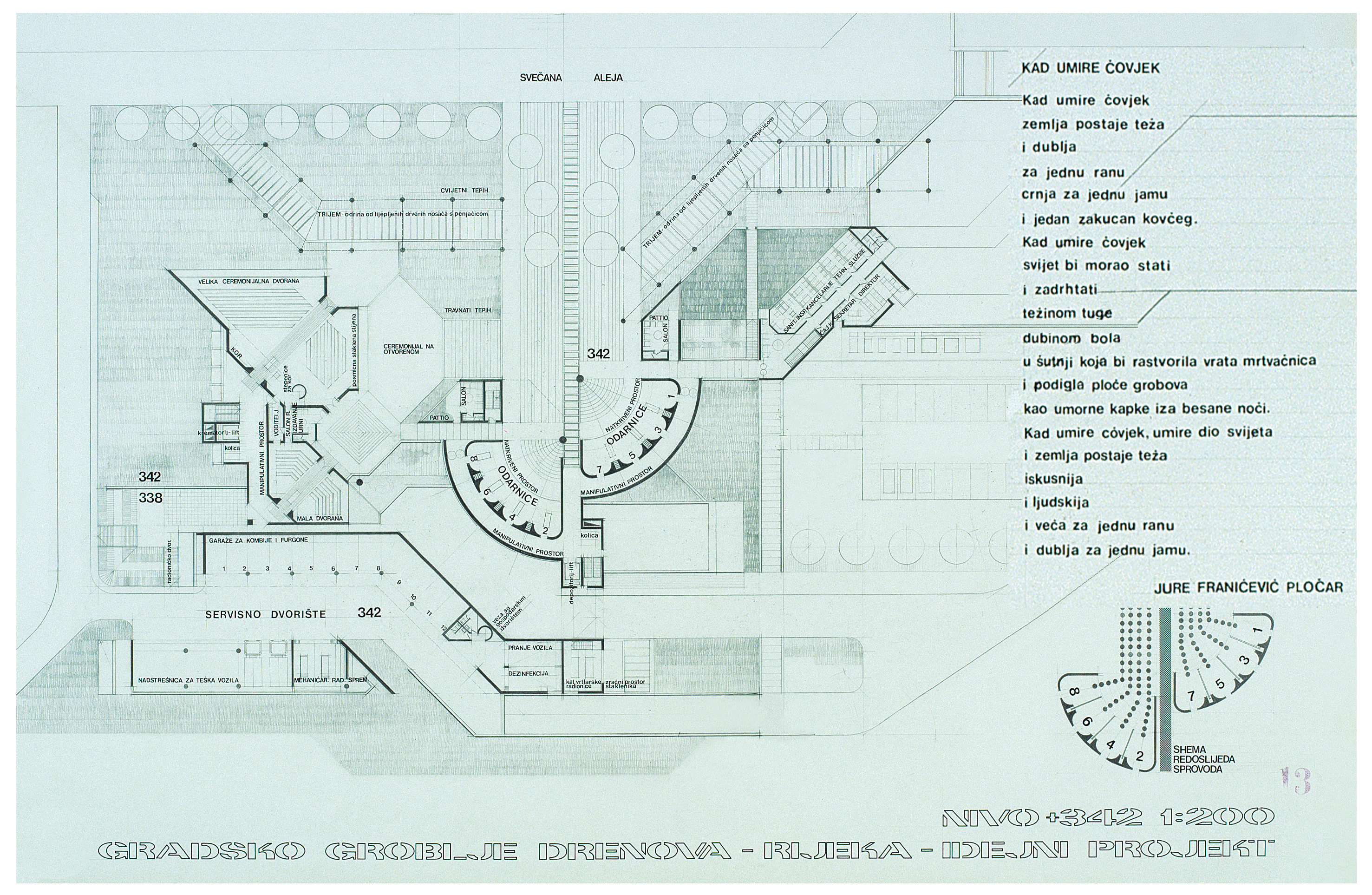

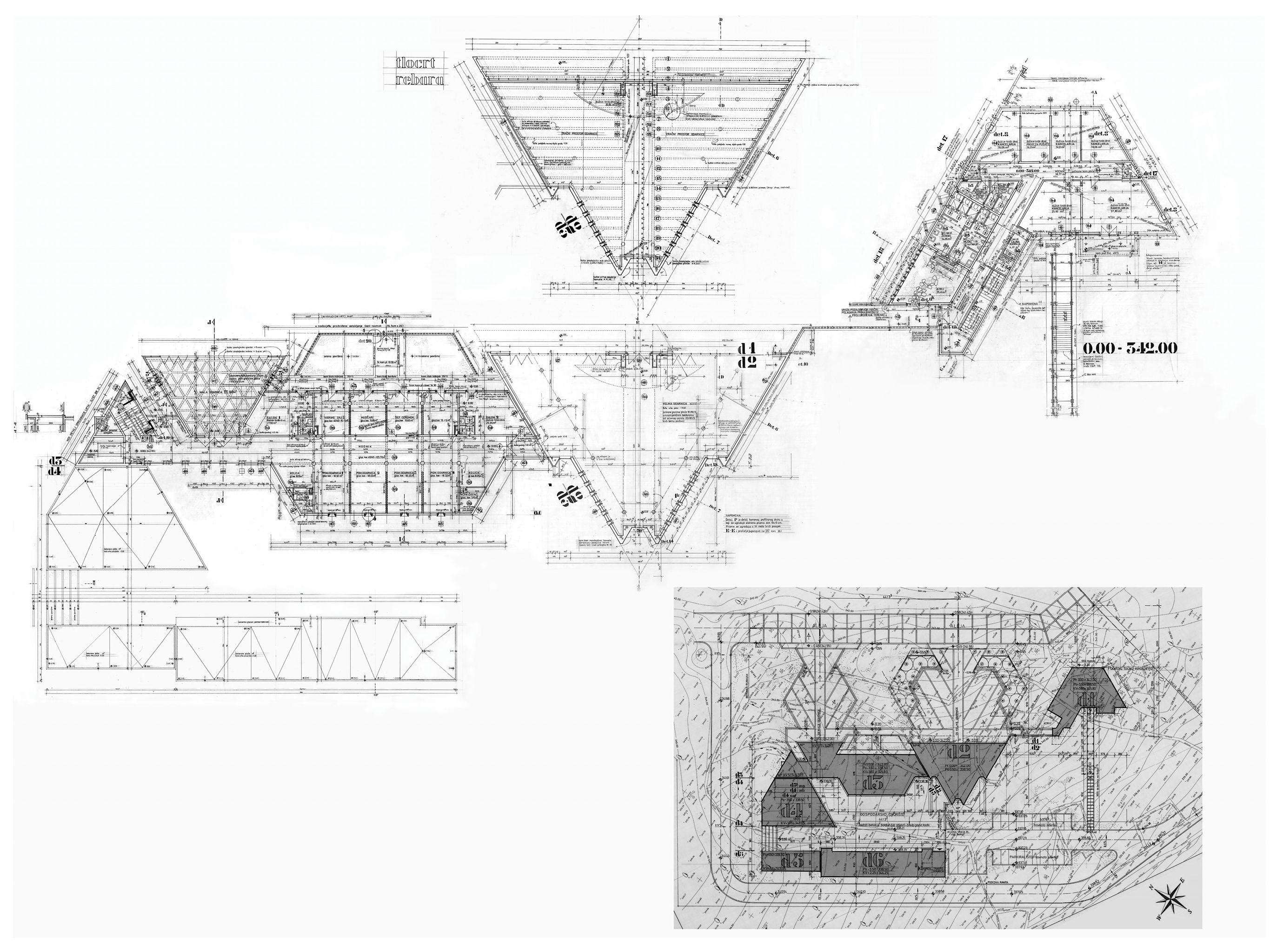

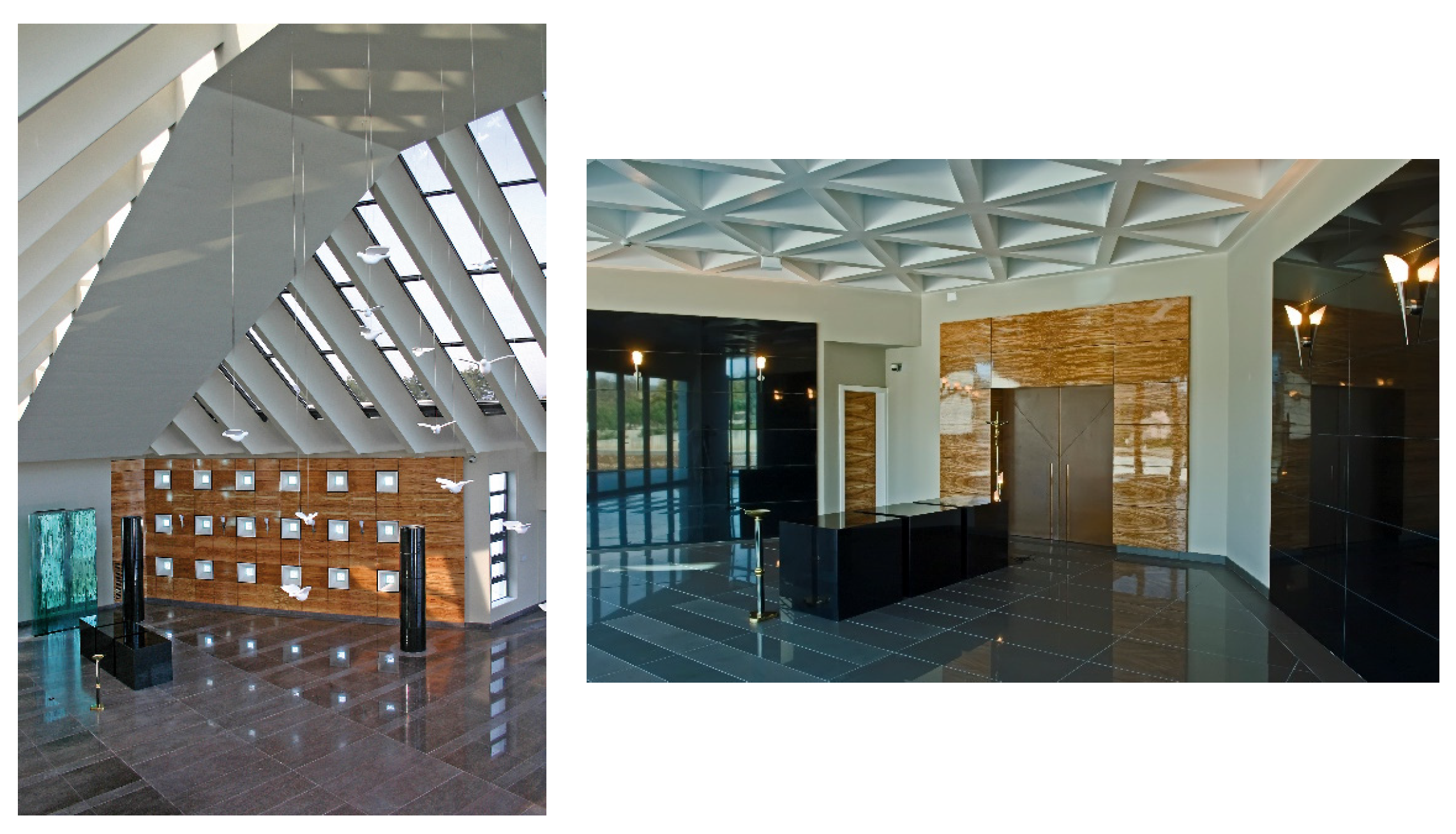

4.6. Ceremonial Object of the Drenova Central City Cemetery in Rijeka

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marković, S. (Ed.) Kincl; Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; Available online: https://www.upi2mbooks.hr/en/trgovina/arhitektura/arhitekti/branko-kincl/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Rogić Nehajev, I. (Ed.) Marijan Hržić: Obrisi opusa.= Marijan Hržić: Outlines of the Opus; UPI-2M: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019; Available online: https://www.upi2mbooks.hr/en/trgovina/arhitektura/ostalo-arhitektura/marijan-hrzic-obrisi-opusa/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Bobovec, B. Miroslav Begović; Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts and Croatian Architects Association: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Paladino, Z. Lavoslav Horvat: Contextual Ambientalism and Modernism; Meandarmedia and Croatian Academy of Science and Arts–Croatian Museum of Architecture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2013; Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/636375 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Barišić Marenić, Z. Architect Zoja Dumengjić; UPI-2M Plus and University of Zagreb–Faculty of Architecture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1112146 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Perković Jović, V. Architect Frano Gotovac; University of Split–Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy: Split, Croatia, 2015; Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/643491 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Paladino, Z. Nikola Filipović: Master of Architecture; Naklada Ljevak and University of Zagreb–Faculty of Architecture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015; Available online: https://www.bib.irb.hr/794157 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- D., Kt. Kovačić, Dinko. In Likovna enciklopedija Jugoslavije; Jugoslavenski leksikografski zavod “Miroslav Krleža”: Zagreb, Croatia, 1984; Volume 2, pp. 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Da., Tu. Kovačić, Dinko. In Hrvatski biografski leksikon; VII Svezak, Leksikografski zavod ‘‘Miroslav Krleža’’: Zagreb, Croatia, 2009; Volume VII, pp. 791–792. Available online: https://hbl.lzmk.hr/clanak.aspx?id=10564 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kovačić, D. Hrvatski Leksikon; Svezak, I., Vujić, A., Eds.; Naklada leksikon u suradnji s Leksikografskim zavodom “Miroslav Krleža”: Zagreb, Croatia, 1996; Volume I, p. 633. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, D. Hrvatska enciklopedija, Mrežno izdanje; online edition; Leksikografski zavod ‘’Miroslav Krleža’’: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021; Available online: https://www.enciklopedija.hr/natuknica.aspx?id=33523 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Tušek, D. A Lexicon of Split Modern Architecture; University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy: Split, Croatia, 2018; pp. 14, 15, 17, 19–21, 31, 32, 39, 44, 45, 53, 54, 57, 62, 75, 77, 90, 199, 208, 213, 216, 237, 262, 266, 285, 286, 340, 349, 353, 356, 361, 364. [Google Scholar]

- Tušek, D. (Ed.) Split: 20th Century Architecture: A Guidebook; University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy: Split, Croatia, 2011; pp. 97, 101, 107, 113, 114, 134, 142, 146, 147. [Google Scholar]

- Šegvić, N. The State of the Situation, One Point of View, 1945–1985; Arhitektura, XXXIX, 196–199 (thematic issue: Architecture in Croatia 1945–1985); Hržić, M., Ed.; Association of Croatian Architect: Zagreb, Croatia, 1986; pp. 120, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Eterović, I. Split: A Picture of the Beloved City; Logos: Split, Croatia, 1987; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Šegvić, E. The Split’s Brick; Šegvić, D., Ed.; University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, Split Society of Architects, Society of Friends of Cultural Heritage: Split, Croatia, 2018; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Tušek, D. Architectural Competitions in Split 1945–1995; University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Split Society of Architects: Split, Croatia, 1996; pp. 26, 169, 171, 212, 213, 215, 218, 260–262, 447, 470, 503, 507, 511, 519. [Google Scholar]

- Galović, K. Masters of Eclectic Modernism; Vijenac 265: Lukavac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2004; p. 18. Available online: https://www.matica.hr/vijenac/265/majstori-eklektickog-modernizma-10676/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Štraus, I. Architecture of Yugoslavia; Svjetlost: Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, 1991; pp. 122–123, 125, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Academician: Dinko Kovačić: Architect, (exhibition catalogue); Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts–Gliptoteka: Zagreb, Croatia, 6–30 November 2014.

- Academician Architect: Dinko Kovačić: Recapitulation, (exhibition catalogue); Galerija umjetnina: Split, Croatia, 15 May–June 11 2017.

- Dinko Kovačić. Available online: http://www.dinkokovacic.net/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Mlivončić, I. Cult of the Region; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1974; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Lorger, S. Dinko Kovačić; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1975; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jukić, Z. Dinko Kovačić: Let’s Make a Human Nest; VUS-Vjesnik u Srijedu: Zagreb, Croatia, 1976; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrović, M. Split’s Example; Politika: Beograd, Serbia, 1979; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Mirković, V. Facades of Memories; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1991; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fiamengo, J. The Architecture of Landscape, the Landscape of Architecture; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1996; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Fiamengo, J. All My Buildings Are Citizens of Split; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2000; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jandrić, D. A Deal between Modernity and Tradition; Večernji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 2000; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Petranović, D. Our Urban Planning Suffers from Bribery; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2000; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gazde, S. Builder with a Soul; Nedjeljna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2000; pp. 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Žutelija, Ž. Architecture on the Wings of Birds; Crnković, Z., Ed.; Mostovi, Otokar Keršovani, biblioteka Svjedočanstva: Rijeka, Croatia, 2000; pp. 270–277. [Google Scholar]

- Gattin, I. I Believe That a House Starts Much Further from Its Wall; Jutarnji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 2001; pp. 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vidulić, S. Dinko without a Filter; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2001; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Hlevnjak, B. Architecture at the Turn of the Century; Hrvatsko slovo: Zagreb, Croatia, 2001; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Jakus, K. It Is Not a Place for the Simple; Feral Tribune: Split, Croatia, 2002; pp. 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pejković, D. Split–A City without an Instruction Manual; Slobodna Dalmacija, Design, Stil, Nekretnine, I: Split, Croatia, 2006; pp. 1, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- I Have Never Drawn a Dining Room–I Drew Lunch; Čovjek i prostor, Association of Croatian Architect: Zagreb, Croatia, 2002; pp. 38–41. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=11265&tify={%22pages%22:[40],%22panX%22:0.305,%22panY%22:0.671,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.443} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- J. F. Conversations about Construction; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2002; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Körbler, I. There Is no Architecture without Joy; Vijenac: Zagreb, Croatia, 2003; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Fiamengo, J. Space Is Not Conquered, but Adopted! Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2003; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Žutelija, Ž. I Get the Best Ideas on Pjaca; Globus: Zagreb, Croatia, 2004; pp. 77–79. [Google Scholar]

- Erceg, K. Houses and Other Passions; Matica: Zagreb, Croatia, 2004; pp. 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Žutelija, Ž. A House for My Wife; Globus: Zagreb, Croatia, 2004; pp. 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Petranović, D. How I Built My Houses; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2007; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jerković, A. You Have to Learn to Love Architecture; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1997; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Bibić, M. Marjan Is Threatened by Profiteers; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2007; pp. 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Šimundić Bendić, T. Split Is a City of Great Potential; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2011; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Brešan, I. Some Architects Move Along the Edge of Morality and Law; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2013; pp. 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, Z. Architecture and Morality; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2014; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gall, Z. Kovačić, the Builder of the Spirit: An Architect Who Loves People and Birds; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2014; pp. 15–17. Available online: https://www.slobodnadalmacija.hr/scena/mozaik/clanak/id/252824/dinko-kovacic--graditelj-duha-arhitekt-koji-voli-ljude-i-ptice (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Kalčić, S. Nativeness or Universality; XV/400-01; Zarez: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015; p. 35. Available online: http://www.zarez.hr/clanci/zavicajnost-ili-univerzalnost (accessed on 30 March 2023).

- Marjanović, V. Split’s Urban Planning Is Rulled by Disorder; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia; pp. 8–9.

- Krnić, M. Concrete Master with a Soul; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2017; p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- Maričić, B. The Unrepeatable Ease of Designing; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia; p. 17.

- Mitrović, M. A Place for Birds; Politika: Beograd, Serbia, 2017; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Vidulić, S. Legendary Architect Dinko Kovačić: I Don’t Want to Watch My Own Decline While the Best Portion of Our Youth, Our Crust, Is Going Abroad; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2017; Available online: https://slobodnadalmacija.hr/scena/kultura/clanak/id/487120/legendarni-arhitekt-dinko-kovacic-ne-zelim-gledati-vlastito-propadanje-dok-najbolji-dio-mladosti-onaj-nas-skorup-odlazi-u-inozemstvo (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Bilić, A.N.; Grimmer, V. Dinko Kovačić: Architect of the Mediterranean; ORIS, XIX: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017; pp. 126–145. [Google Scholar]

- Topić, A. We Have Chased the Souls Out of the Courtyard; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2018; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorović, K. Academician Dinko Kovačić: Houses Are like People, Sometimes They Suffer Violence; Dubrovniknet.hr: Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2018; Available online: http://www.dubrovniknet.hr/novost.php?id=65047#.W-l60dVKi70 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- R., K. Academician Kovačić: Split 3–My Memories; Slobodna Dalmacija; 16.10.2018; Split, Croatia, 2018; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Krnić, M. Split 3 or a Plea for the Urban Institute; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2018; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Promoter of the Unbreakable Bond Between the Man and Space; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2019; p. 8.

- Vidulić, S. Dinko Kovačić: I Have Never Sold Myself, Not for any Money; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2019; pp. 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baretić, R. On Sundays at 2. In Lovori i Drače Renata Baretića; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2019; p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Kekez, S. We Will Rebuild ‘Bajamontuša’, There Is No More Building on Marjan! Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2019; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Krnić, M. Dinko Kovačić, Architect of Joy and of Houses for Songbirds; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2019; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kiš, P. “The Houses I’ve Designed Are my Guardian Angels”; Jutarnji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019; pp. 80–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kiš Terbovc, P. Life Confession of Our Great Architect, One of the Authors of the Famous Split 3 “The Buildings I’ve Designed Are Alive, They Are My Friends...”; Jutarnji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019; Available online: https://www.jutarnji.hr/life/zivotne-price/zivotna-ispovijest-naseg-velikog-arhitekta-jednog-od-autora-cuvenog-splita-3-zgrade-koje-sam-projektirao-su-zive-one-su-moji-prijatelji-8697977 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Perkov, I. Dinko Kovačić: I Am a Former Architect and Professor, Now Just a Man. He Revealed Which Buildings in Split Are a Punch in the Eye for Him, Praised the Young People at DAS and the Ambasador Hotel; Universitas: Split, Croatia; Available online: https://slobodnadalmacija.hr/split/dinko-kovacic-ja-sam-bivsi-arhitekt-i-profesor-sad-samo-covjek-otkrio-koje-su-mu-zgrade-u-splitu-saka-u-oko-pohvalio-mlade-u-das-u-i-hotel-ambasador-1079722 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Rožić Mikolašević, N. Architecture Is Not Made, It Is Lived. 25 May 2022.

- Residential Towers in Split; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1970; p. 11. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10576&tify={%22pages%22:[11],%22panX%22:0.356,%22panY%22:0.733,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.378} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Vilić, R. They Are Building Split 3: Lavčević–1000 Apartments a Year; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1970; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Pasinović, A. Individual Living on the Sixteenth Floor; Telegram: Zagreb, Croatia, 1972; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Vilić, R. Creation of Space and Mood; Slobodna Dalmacija; 9.2.1974; Split, Croatia, 1974; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, D. Let’s Not Forget the Deal; Večernji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 1975; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, D. Environment Architecture: A City for Man; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1976; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kečkemet, D. Humane and Aesthetic Approach; Vjesnik: Zagreb, Croatia, 1977; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Kečkemet, D. Dinka Šimunovića Street in Split; Nedjeljna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1977; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Vrankulj, J. Split 3: An Essay on the Personality of a Unique Project and of an Urban Idea; Baustela.hr: Zagreb, Croatia, 2021; Available online: https://baustela.hr/nekretnine/split-3-osobnost-jednog-neponovljivog-projekta-i-urbane-ideje/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kovačić, D. Split 3: What Came Before It, What It Was, and What It Is Today; Art Bulletin 66(2016); The Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, The Department of Fine Arts, The Fine Arts Archives: Zagreb, Croatia, 2016; Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/200947 (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Kiš, P. “The Enthusiasm That Accompanied Split 3 Will Never Again Be Felt in This City”; Jutarnji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014; pp. 27, 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Magdić, D. The Only Task of Split 3 Was to Confront Alienation, Pogledaj.to. 9 December 2013. Available online: http://pogledaj.to/arhitektura/jedini-zadatak-splita-3-je-bio-suprotstaviti-se-otudenju/(accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Jelača, M. The Obverse of Split 3; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2000; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- J., F. Kovačić’s Mediterranean; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2002; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Magdić, D. The Captain of the Space-Producing Ship. Pogledaj.to, 9 October 2014. Available online: https://pogledaj.to/arhitektura/kapetan-broda-koji-proizvodi-prostor/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Lendvaj, A. Architecture Enables People to Live Happily; Večernji list: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014; Available online: https://www.vecernji.hr/kultura/arhitektura-ljudima-omogucuje-sretan-zivot-971795 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Žunić, A. An Architect of Native Expression; Vijenac: Zagreb, Croatia, 2014; p. 21. Available online: http://www.matica.hr/vijenac/540/arhitekt-zavicajnog-izricaja-23861/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Opening of the Retrospective Exhibition “Academician Dinko Kovačić Architect”. Available online: https://arhitekti-hka.hr/hr/novosti/dogadanja/otvorenje-retrospektivne-izlozbe-akademik-dinko-kovacic-arhitekt,1573.html (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Vidulić, S. I’m Definitely Saying Goodbye to Architecture because I don’t Want to Watch my own Decay; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2017; pp. 18–21. [Google Scholar]

- Perković Jović, V. The Relationship between Man and Space: Recapitulation; Retrospective Exhibition of Dinko Kovačić, Art Gallery, Split 15 May–11 June 2017; Mance, I., Ed.; Kvartal: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017; pp. 55–62. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/287585 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Vujević, E. Split Doyen Said Farewell to Architecture; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2017; Available online: https://www.slobodnadalmacija.hr/kultura/clanak/id/486181/splitski-doajen-rekao-zbogom-arhitekturi-rekapitulacija-bogate-karijere-dinka-kovacica (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Restović, M. A Retrospective Exhibition of Dinko Kovačić’s Works Is at the Art Gallery. Radio Dalmacija, 14 May 2017. Available online: https://www.radiodalmacija.hr/galeriji-umjetnina-retrospektivna-izlozba-radova-dinka-kovacica/(accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Franceschi, B. Dinko Kovačić: Recapitulation; Art Gallery: Split, Croatia, 2017; Available online: https://www.galum.hr/izlozbe/izlozba/1521/ (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Museum Documentation Centre. Calendar of Events: Overview of the Month–May 2017 (15 May 2017). Available online: http://www.mdc.hr/hr/kalendar/pregled-mjeseca/rekapitulacija-_-dinko-kovacic,99303.html?date=15-05-2017#.W8mTD9SLRnI (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Pejković-Kaćanski, M. Dinko Kovačić Said Goodbye to Architecture with an Emotional Speech; Vecernji.hr: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017; Available online: https://www.vecernji.hr/kultura/emotivnim-nastupom-dinko-kovacic-rastao-se-od-arhitekture-1170306 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Fiamengo, J. Kovačić’s Split at the Paris’s UNESCO; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2002; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Domić, L. Kovacic’s Architectural Gems for Europe and the World; Hrvatsko slovo: Zagreb, Croatia, 2003; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- H. Dinko Kovačić Exhibits at the Palace of Europe in Strasbourg; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2003; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Botteri, I. Exhibition of the Croatian Academician Dinko Kovačić; Korijeni: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2013; pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Architect Dinko Kovačić: Lecture and Exhibition. Available online: http://trajekt.org/2013/06/06/arhitekt-dinko-kovacic/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Architect Dinko Kovačić. Available online: http://www.mao.si/Razstava/Arhitekt-Dinko-Kovacic (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Zorko, A. Between Modernity and Tradition; Delo in Dom: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2013; pp. 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- MoMA: Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980; Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA): New York, NY, USA, 15 July 2018–13 January 2019; Available online: https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3931 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Skansi, L. The World has Recognized the Importance of Split 3. What Are the People of Split Waiting for?: Split all the Way to New York: Exhibition at the MoMA Museum; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2018; pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- The Man who Brought Yugoslavian Architecture to New York Explains Why Split 3 Is a Masterpiece in the Rank of Diocletian’s Palace and the Closest Example of Primordial Split Urbanity. Available online: www.slobodnadalmacija.hr/dalmacija/split/clanak/id/564856/covjek-koji-je-jugoslavensku-arhitekturu-doveo-u-new-york-tumaci-zasto-je-split-3-remek-djelo-u-rangu-dioklecijanove-palace-i-najblizi-primjer-iskonskog-splitskog-urbaniteta (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Ožegović, N. The Glory and Power of YU Architecture–Hated only Here; Express.24sata.hr: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018; Available online: https://www.express.hr/kultura/slava-i-moc-yu-arhitekture-omrazena-samo-kod-nas-16807 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Zagreb Salon Awards; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1973; p. 4. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10604&tify={%22pages%22:[4],%22panX%22:0.344,%22panY%22:0.435,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.377} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Vilić, R. “Borba” Award to Split Architects Dinko Kovačić and Mihajlo Zorić; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1974; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Vilić, R. D. Kovačić and M. Zorić Receive the “Vladimir Nazor” Lifetime Award; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1974; p. 5, (AN: Note a lifetime, but an annual award). [Google Scholar]

- “Vladimir Nazor” Awards for 1974: Annual Award to Dinko Kovačić and Mihajlo Zorić; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1975; p. 13. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10674&tify={%22pages%22:[13],%22view%22:%22info%22} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Recognition to Dinko Kovačić from Split; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2001; p. 4.

- Pavić, J. Lifetime Achievement Award to I. Martinac, Annual Award to Dinko Kovačić; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2002; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Slobodna Dalmacija Awards for 2002 in the Field of Culture, Science and Journalism; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2002; p. 1.

- Laušić, V. Architect Dinko Kovačić Awarded; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2004; p. 68. [Google Scholar]

- Petranović, D. Lifetime Achievement Award to D. Kovačić, and Personal Award to Duplančić; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2004; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- M., P. Award as a Congratulation for Living in This City; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2004; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Dinko Kovačić: “Vladimir Nazor“ Lifetime Achievement Award. In Award “Vladimir Nazor” for 2010; Vraneša, A. (Ed.) Special editions, Book 10; Republic of Croatia, Ministry of Culture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2011; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- “Vladimir Nazor” Award. Available online: https://min-kulture.gov.hr/o-ministarstvu/djelatnosti/nagrade-u-kulturi/nagrada-vladimir-nazor/16565 (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Akademik Dinko Kovačić–Udruženje hrvatskih arhitekata (uha.hr). Available online: https://uha.hr/akademik-dinko-kovacic/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Dinko Kovačić. In Yearbook of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts for the Year 2006; book 110; Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts: Zagreb, Croatia, 2007; pp. 538–541.

- Fiamengo, J. The Light of the Brač Stone; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2000; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Fiamengo, J. Architects are Producers of Happiness; Nedjeljna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2002; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Fiamengo, J. Architectural School of Wisdom; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2009; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Frampton, K. Modern Architecture: A Critical History; Kralj-Štih, A., Ed.; Globus Nakladni Zavod, Biblioteka Posebna Izdanja: Zagreb, Croatia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zevi, B. History of Modern Architecture II: From Franck Lloyd Wright to Frank O. Gehry: Organic Sequence; Roth-Čerina, M., Ed.; Golden Marketing-Tehnička Knjiga, University of Zagreb-Faculty of Architecture: Zagreb, Croatia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, J.R.W. Modern Architecture Since 1900; Phaidon Press Limited: London, UK; Phaidon Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kečkemet, D. City for Man; book XXVII; The Croatian Society of Art Historians: Split, Croatia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Gotovac, F. Dictatorship Program: (Subjective) Author’s Reflections Competition “Krvavice–Šibenik”; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1982; pp. 28–29. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10796&tify={%22pages%22:[28],%22panX%22:0.443,%22panY%22:0.66,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.45} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Action Program for the Realization of Construction of “Split III”: Second Fase of Preparation for Construction; Company for the Construction of Split–PIS: Croatia, Split, 1968/1969.

- Mušič, B. Urban Planning Is a Will; Arhitektura: Zagreb, Croatia, 1968; pp. 8–14. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10032&tify={%22pages%22:[16],%22view%22:%22info%22} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Guidelines for the Construction of “Split III”; Company for the Construction of Split–PIS: Split, Croatia, 1968.

- Zorić, M. Residantial Objects–Split 3: Project Program; Company for the Construction of Split–PIS, Association of Construction Companies: Split, Croatia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Zorić, M. Project Program of Residantial Objects “Split 3”; Company for the Construction of Split–PIS, Association of Construction Companies: Split, Croatia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Pasinović, A. The Regionalism of Architecture and the Architectonics of Regionalism; Telegram: Zagreb, Croatia, 1972; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- I., Mc. Appropriate Architecture; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1972; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Plejić, R. An Essay on Individual Residential Construction in the Split Area; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1983; pp. 24–25. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10539&tify={%22pages%22:[24],%22panX%22:0.246,%22panY%22:0.52,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.643} (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Hotel “Elaphusa”–Bol; URBS: Split, Croatia, 1973; p. 92.

- Urban Planning Solution of the Hotel Complex in Bol; URBS: Split, Croatia, 1973; p. 91.

- Gotovac, F. Hotel Complex “Bretanide” in Bol on Brač; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1987; pp. 22–23. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10820&tify={%22pages%22:[30],%22panX%22:0.29,%22panY%22:0.53,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.377} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Zlatko Ugljen Architect. Available online: https://zlatkougljen.com/en/architecture (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Boris Magaš. Available online: https://enciklopedija.hr/natuknica.aspx?id=37977 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Ante Rožić. Available online: https://enciklopedija.hr/natuknica.aspx?id=53562 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Žutelija, Ž. A Dream Hotel Reality; Danas: Zagreb, Croatia, 1984; pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrović, M. Bretanide; OKO: Zagreb, Croatia, 1985; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- S.P. A New Tourist Resort “Bretanida” Opened in Bol Yesterday; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1984; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gotovac, F. No Dilemmas; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1984/1985; p. 19.

- Fiamengo, J. Countdown of Happy Moments; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2001; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- M., M. A Golden Craft on the Golden Horn; Politika: Beograd, Serbia, 1985; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Domić, L. The Olive Promised the Concrete It Would Grow Straight; Hrvatsko slovo: Zagreb, Croatia, 2000; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Mrinjek Kliska, N.; Šerman, K.; Bačić, D.; Mrđa, A. The Impact of Tourism Trends on Hotel Classification in Croatia at the Beginning of the 21st Century; Prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 2020; pp. 334–345. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/clanak/361617 (accessed on 27 April 2023).

- Miličić, J. The Spirit of the Work and the City; University of Split, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy: Split, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- L., V. School Opened for 2500 Students; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1992; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Žutelija, Ž. A School for Students and–Birds; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 1992; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tenžera, M. A Lot of Parents Have Called Me and Said: “Since Attending Your School, My Child Has Completely Changed”; Nedjeljni Vjesnik: Zagreb, Croatia, 2000; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Žutelija, Ž. My School Frees Children of Fear of Classrooms and Teachers; Globus; 19.1.2001.; Zagreb, Croatia, 2001; pp. 94–95. [Google Scholar]

- Petranović, D. The Most Beautiful Villa Stupalo; Slobodna Dalmacija: Split, Croatia, 2001; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Kolacio, Z. Successful Competition; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1981; p. 15. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10746&tify={%22pages%22:[15],%22panX%22:0.49,%22panY%22:0.732,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.378} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Competition for a Crematorium in Rijeka; Čovjek i prostor: Zagreb, Croatia, 1981; pp. 12–14. Available online: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10746&tify={%22pages%22:[12],%22panX%22:0.586,%22panY%22:0.691,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.378} (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Pallasmaa, J. Empathic and Embodied Imagination: Intuiting Experience and Life in Architecture. In Architecture and Empathy; Tidwell, P., Ed.; Tapio Wirkkala-Rut Bryk Foundation: Espoo, Finland, 2015; pp. 4–19. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292783014_Architecture_and_Empathy (accessed on 27 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perković Jović, V.; Mrinjek Kliska, N. Specific Design Approach of Croatian Architect Dinko Kovačić: The Coexistence of Modernism and Tradition in the Second Half of the 20th Century. Heritage 2023, 6, 4993-5029. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070265

Perković Jović V, Mrinjek Kliska N. Specific Design Approach of Croatian Architect Dinko Kovačić: The Coexistence of Modernism and Tradition in the Second Half of the 20th Century. Heritage. 2023; 6(7):4993-5029. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070265

Chicago/Turabian StylePerković Jović, Vesna, and Neda Mrinjek Kliska. 2023. "Specific Design Approach of Croatian Architect Dinko Kovačić: The Coexistence of Modernism and Tradition in the Second Half of the 20th Century" Heritage 6, no. 7: 4993-5029. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070265

APA StylePerković Jović, V., & Mrinjek Kliska, N. (2023). Specific Design Approach of Croatian Architect Dinko Kovačić: The Coexistence of Modernism and Tradition in the Second Half of the 20th Century. Heritage, 6(7), 4993-5029. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070265