The Communication Challenge in Archaeological Museums in Puglia: Insights into the Contribution of Social Media and ICTs to Small-Scale Institutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The Case Study’s Context: The Italian and Apulian Museum Heritage

3.1. The National Museum Sector’s Evolution

- −

- at the end of 2019, the Italian cultural heritage consisted of 4880 museums, monuments, and archaeological areas, 464 of which are state properties and 4416 are private or public, mostly municipal, properties; among these, 3928 museums account for 80.5% of the overall heritage [105];

- −

- at the end of 2020, 4265 public and private museums and similar institutions, among which 3337 museums and 295 archaeological areas, were open or partially open in the country [106].

- −

- Conferral of administrative autonomy to state museums of relevant national interest (up to that time simple extensions of ministerial superintendences), aligning them to all other public and private museums (at the time of writing, bestowed museums are 44);

- −

- creation of the new Regional Museum Poles (now “Directorates”), territorial branches of the General Directorate for Museums, in charge of defining common promotion strategies and objectives across the region, identifying cultural tourism itineraries, and spreading international standards among all regional public and private museums. They are constituted by state museums in each region, without administrative autonomy but with their own statute, balance, and individual mission;

- −

- creation of the Regional Museum System, including Regional Museum Poles and all other public and private museums meeting criteria and standards defined in the Reform Guidelines and the ICOM Ethic Code, on a voluntary basis and a specific Convention with the Pole.

3.2. The Case Study: The Archaeologic Museums of Puglia

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. The Survey on Museums: Aims and Design Issues

4.2. The Sample

4.3. The Questionnaire

- Museum’s data;

- identifying data (denomination)

- legal state (public/private property, public/private management);

- public bodies in charge of preservation, fruition, and promotion;

- contact person for the questionnaire.

- Online communication

- Existence of a specific communication strategy and target;

- communication channels (website and social media): channels presently active for the museum, perceived efficacy, problems encountered, year of activation, reason for possible dropout;

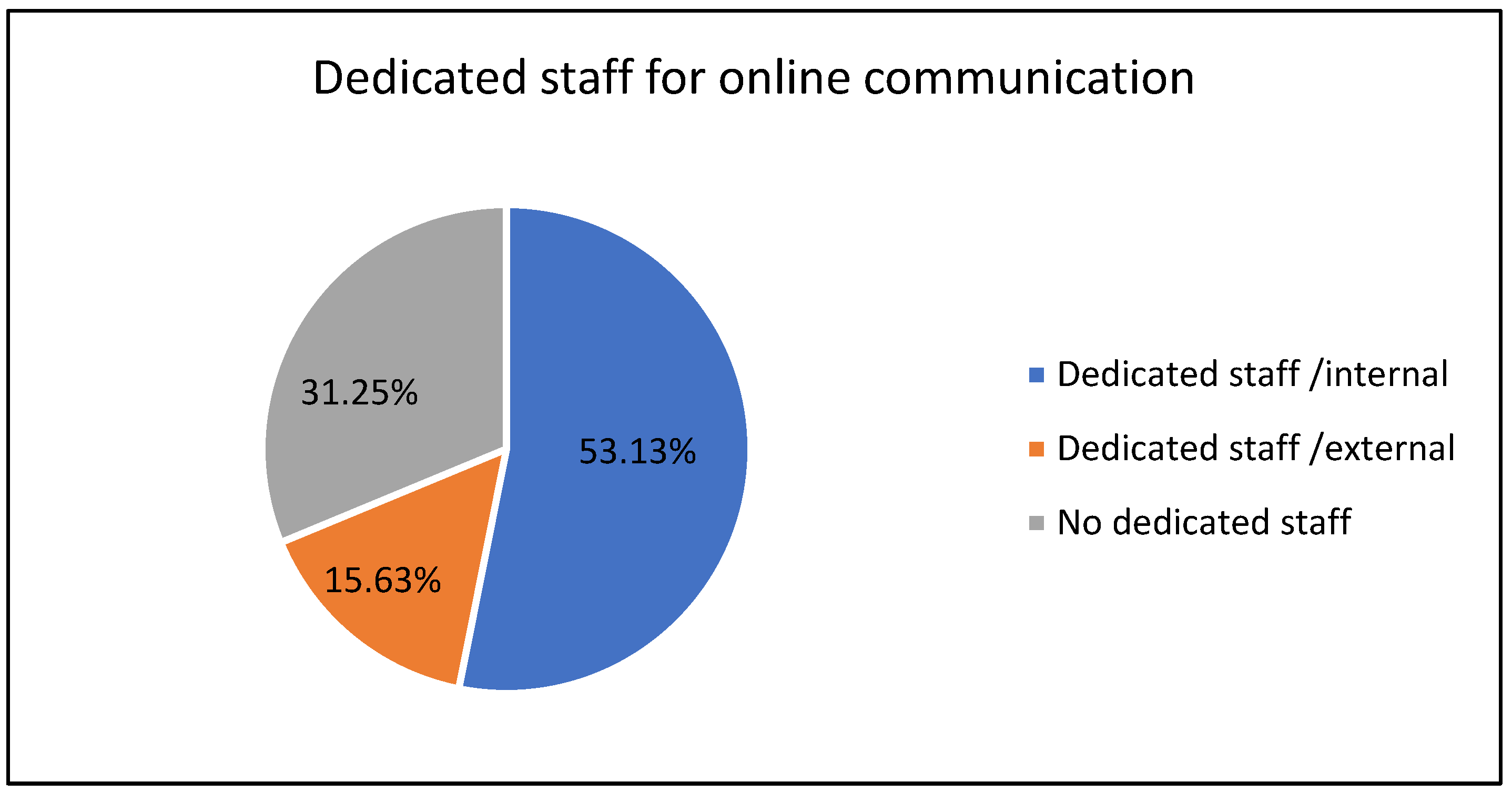

- dedicated staff and related policy;

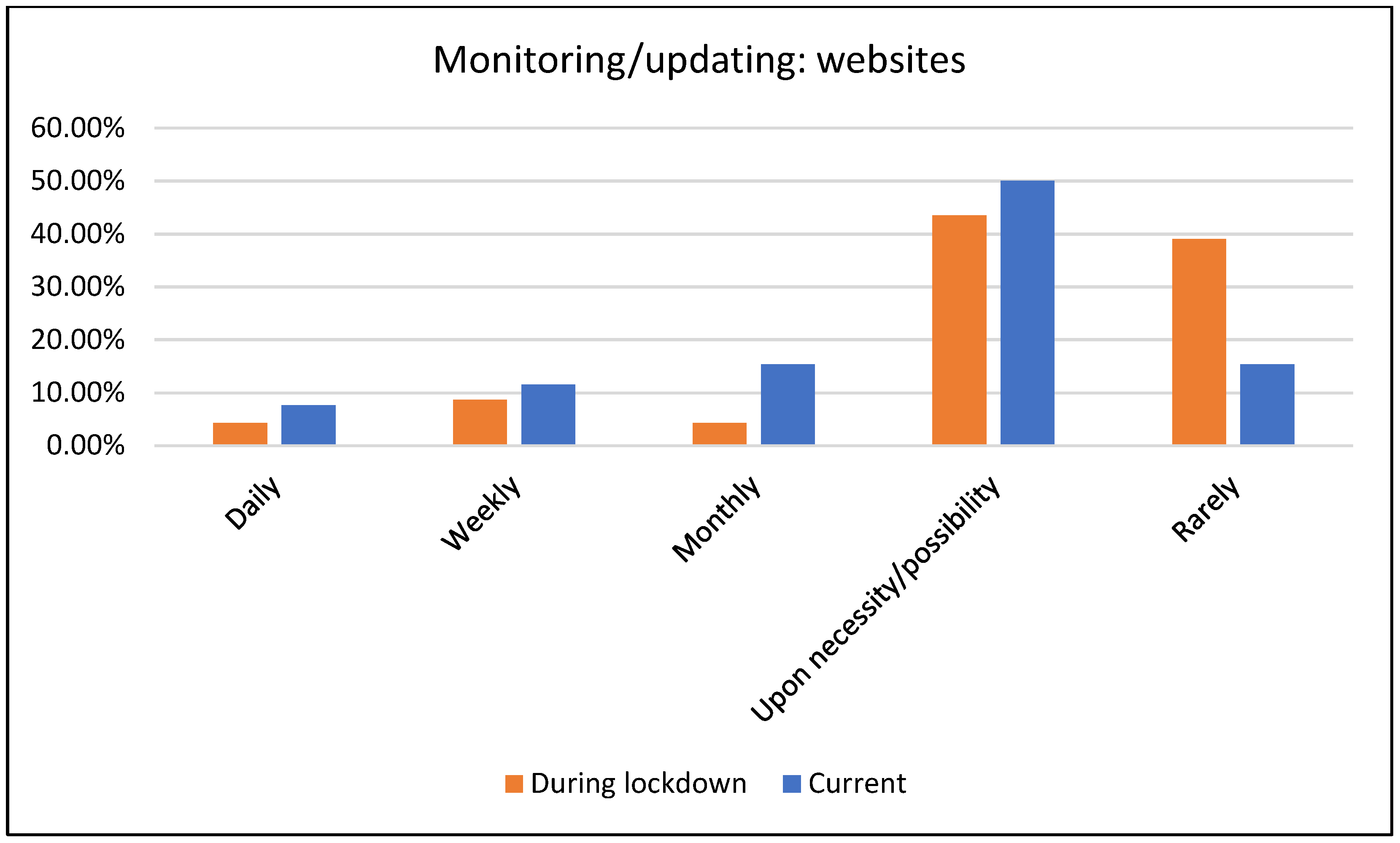

- regularity of website and SN accounts monitoring/updating, at present and during the lockdown;

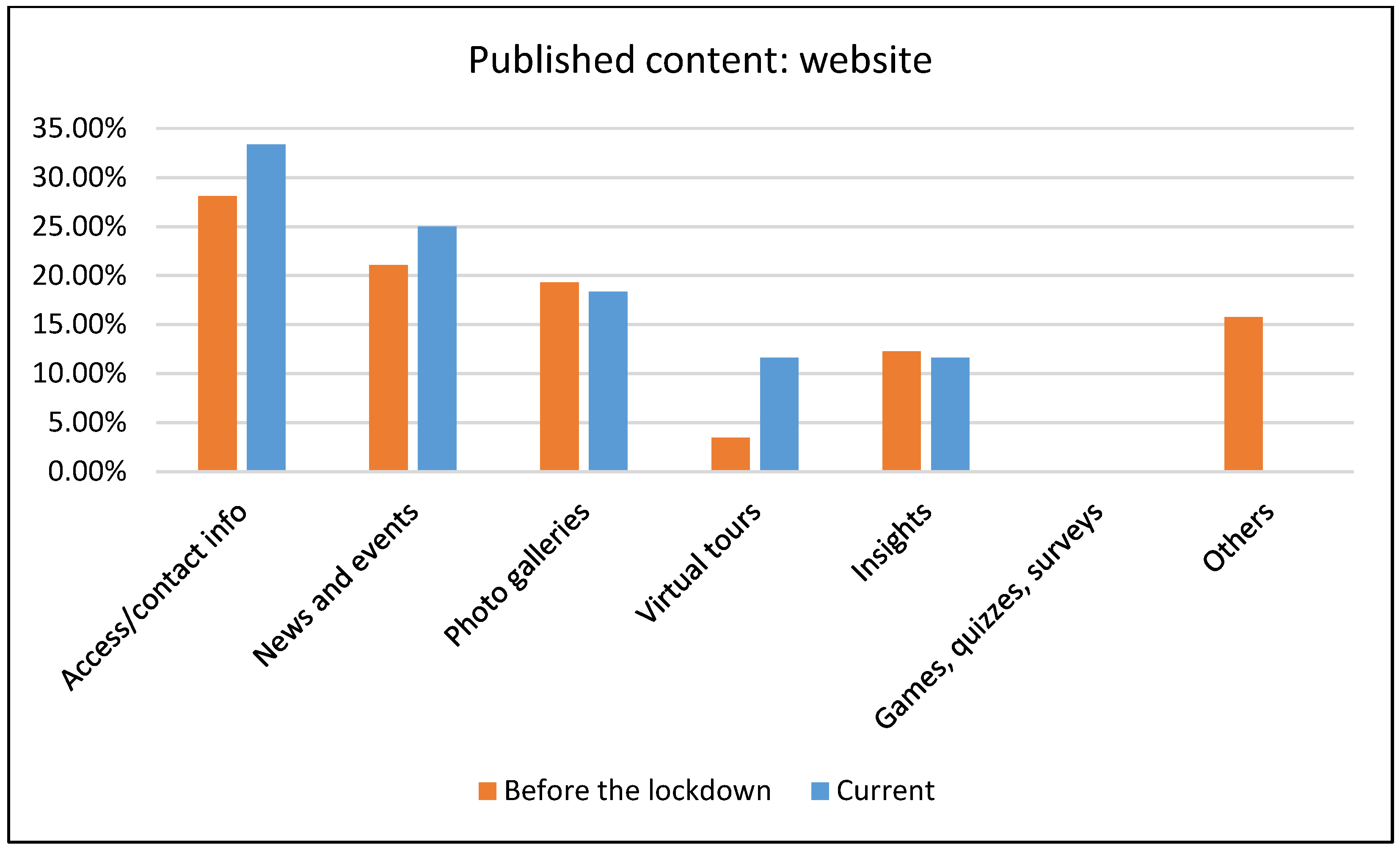

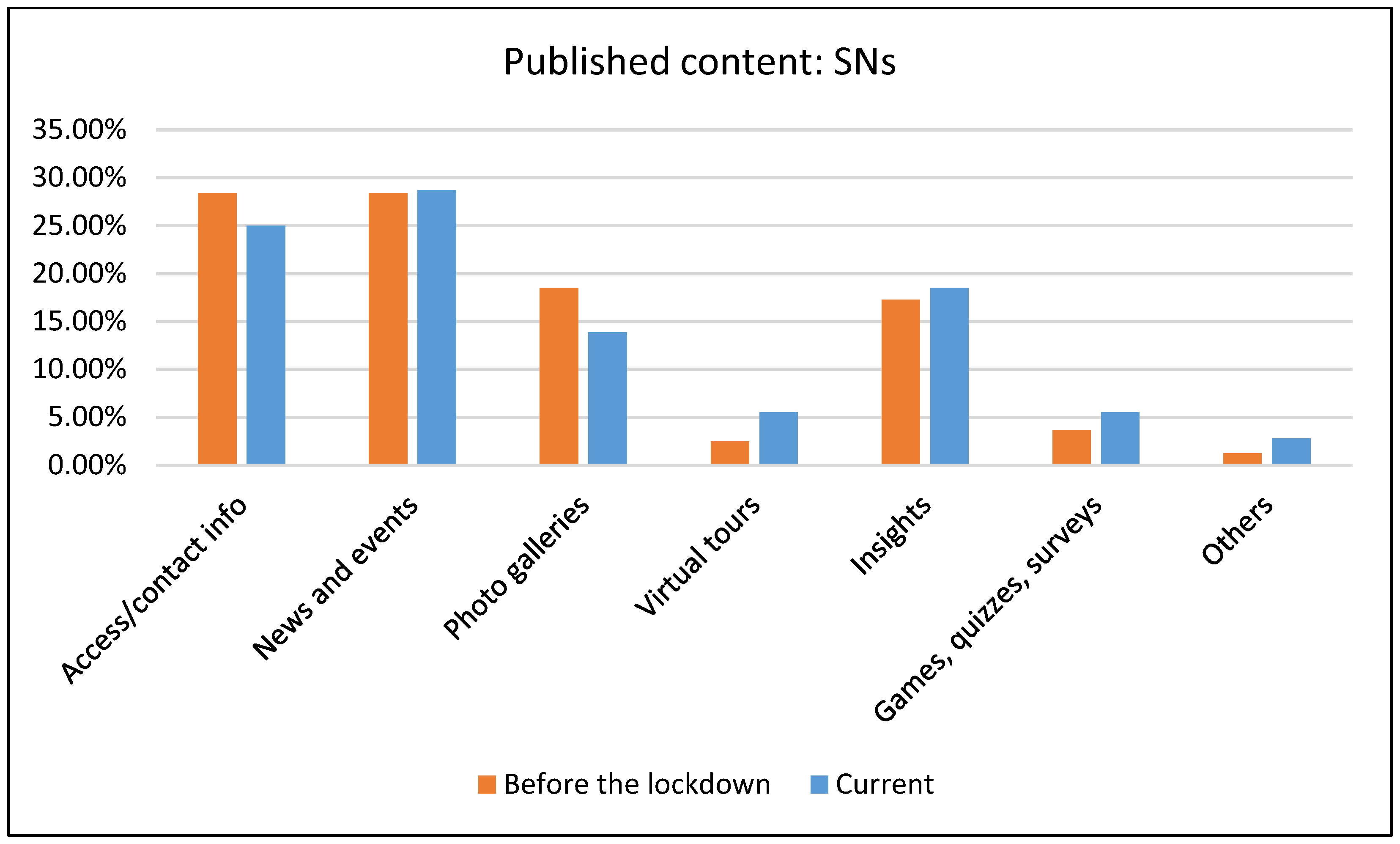

- type of information shared on communication media before the lockdown and at present;

- visit flows before the lockdown and after reopening;

- visit flows in the three years preceding the lockdown;

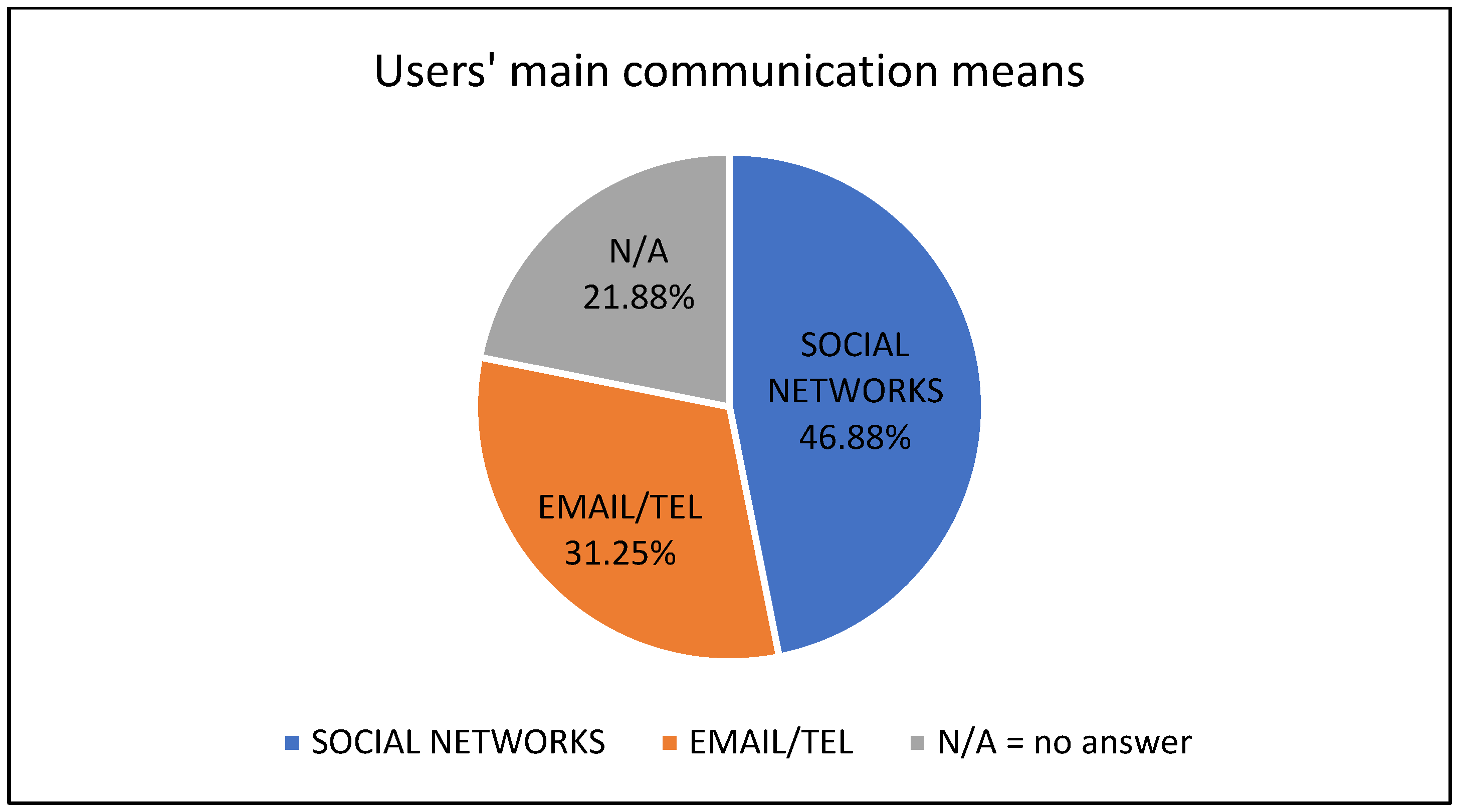

- communication means preferred by the public to communicate with museums;

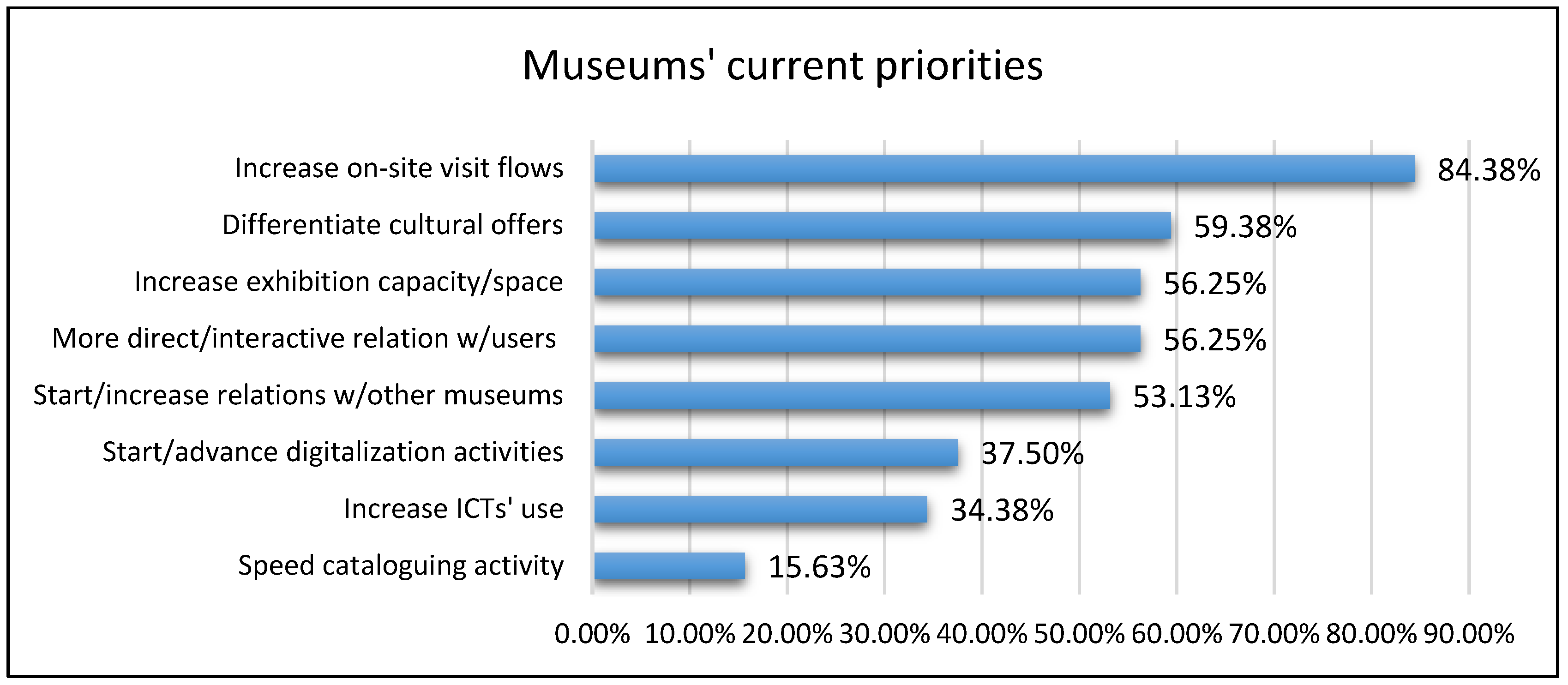

- current priorities in museum management.

- Digital content and digitization issues

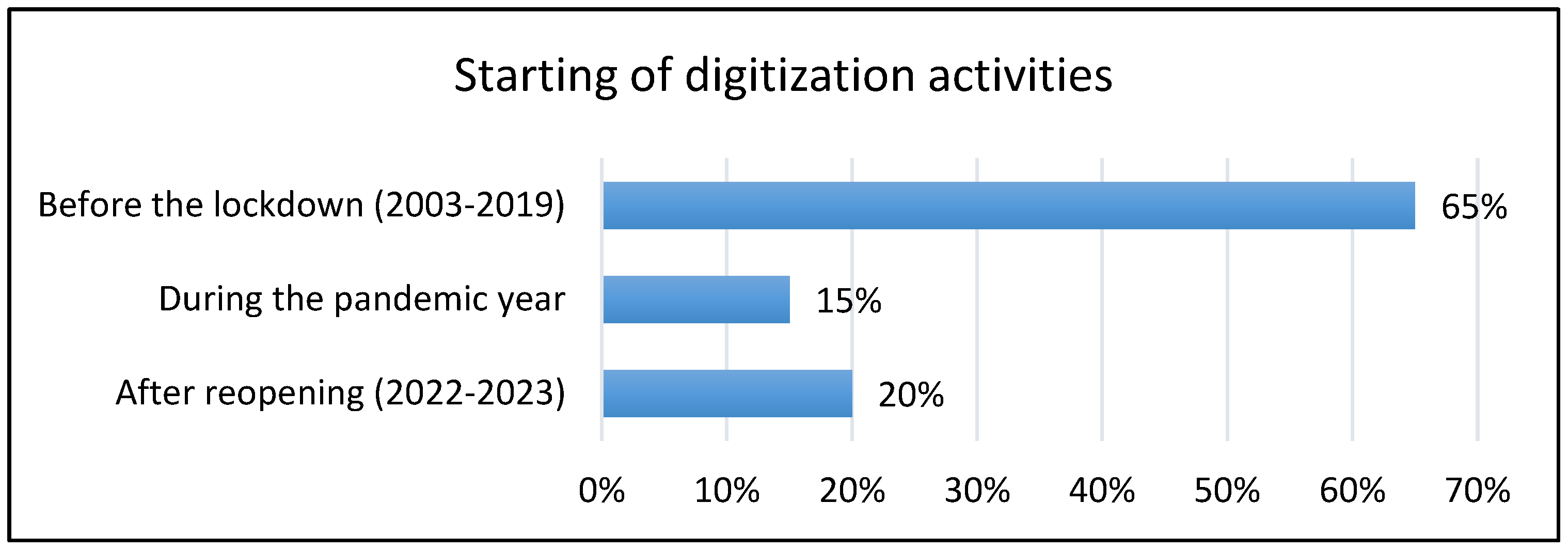

- Starting year of collections’ digitization process;

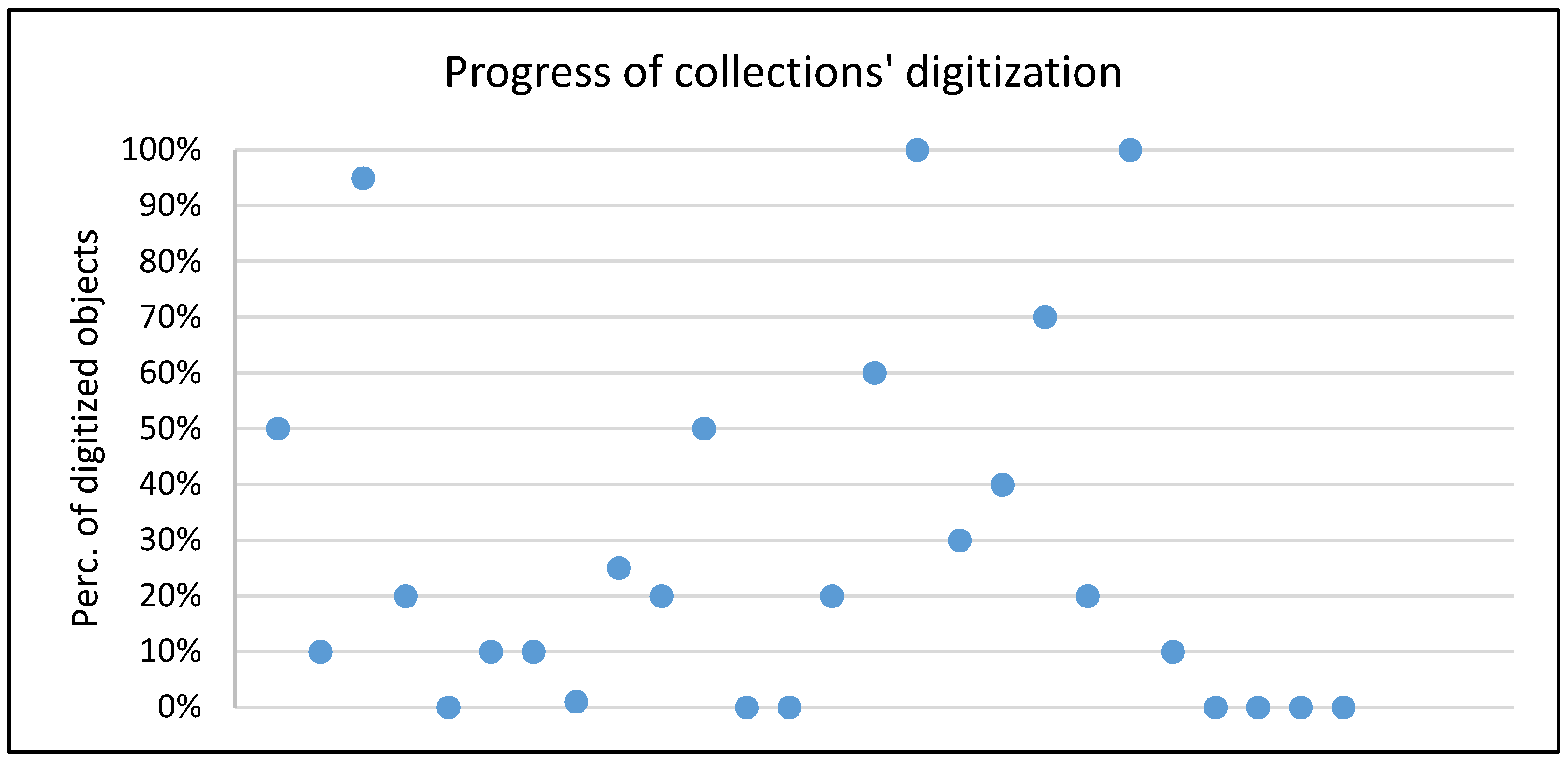

- current percentage of digitized objects on the total of owned objects and of objects stored in deposits on the total of digitized objects;

- percentage of digital objects realized specifically for the lockdown;

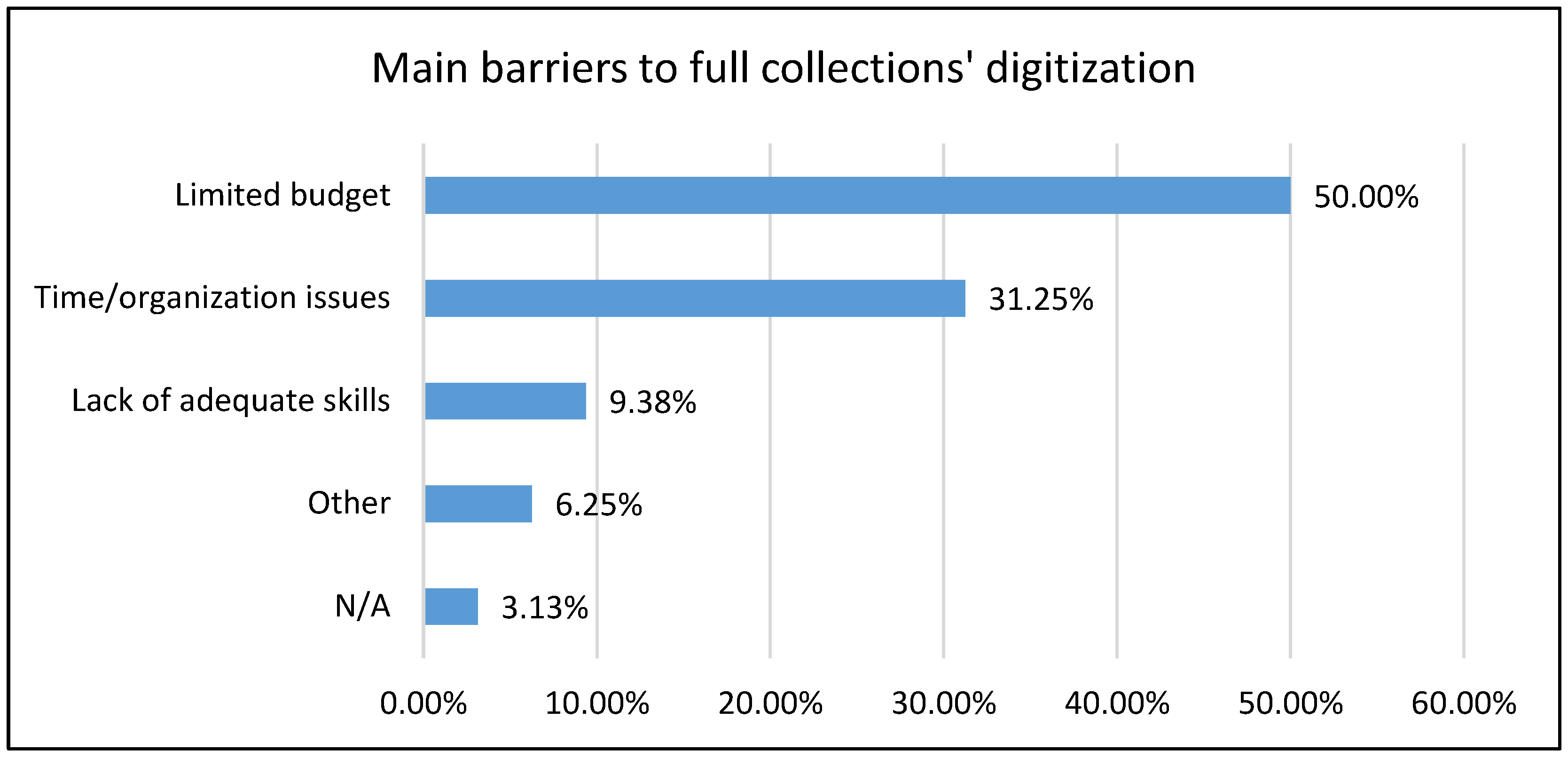

- problems encountered;

- other digital contents and products elaborated by the museum and their perceived usefulness in remote or on-site mode;

- interest in digital products shown by audiences during the lockdown and after reopening;

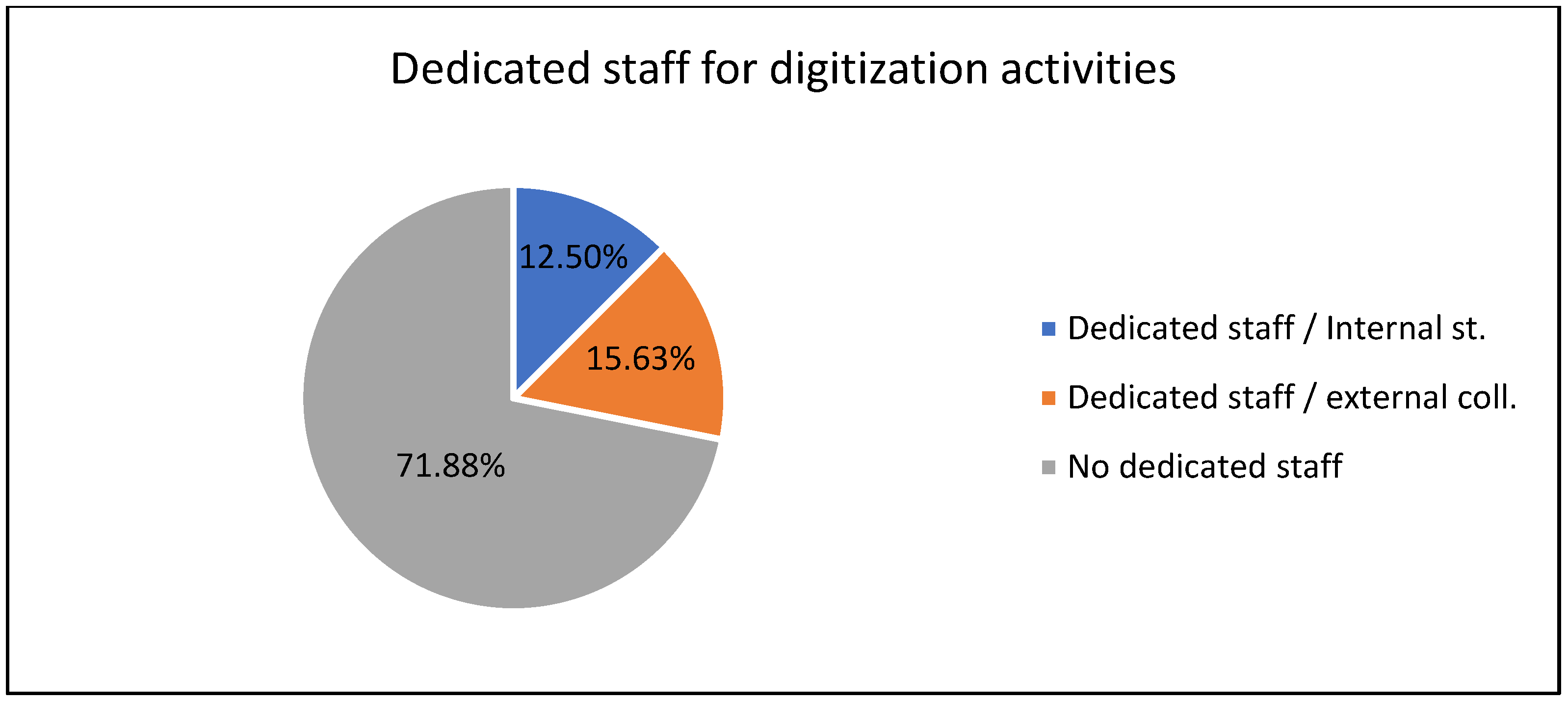

- dedicated staff and related policy.

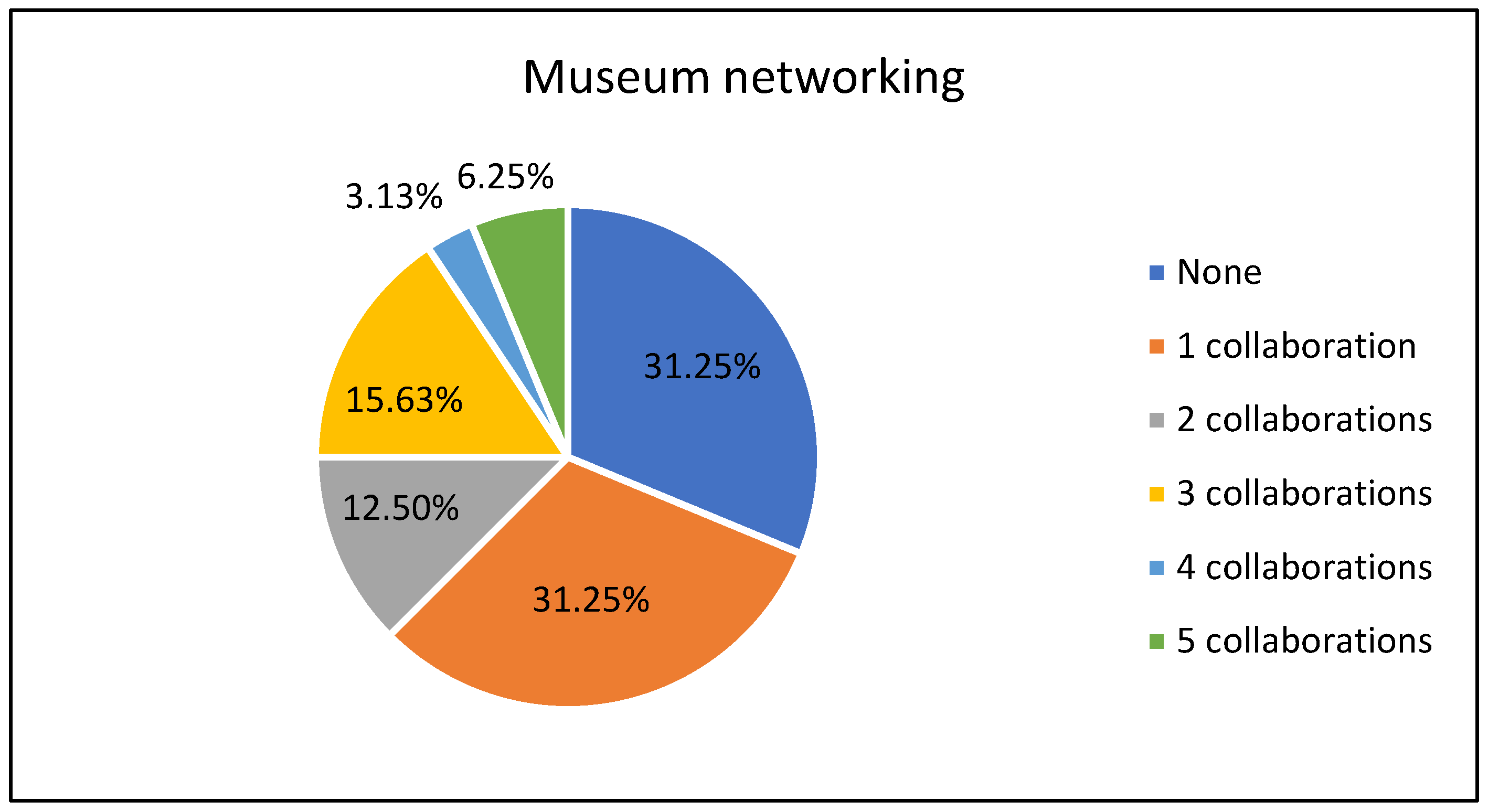

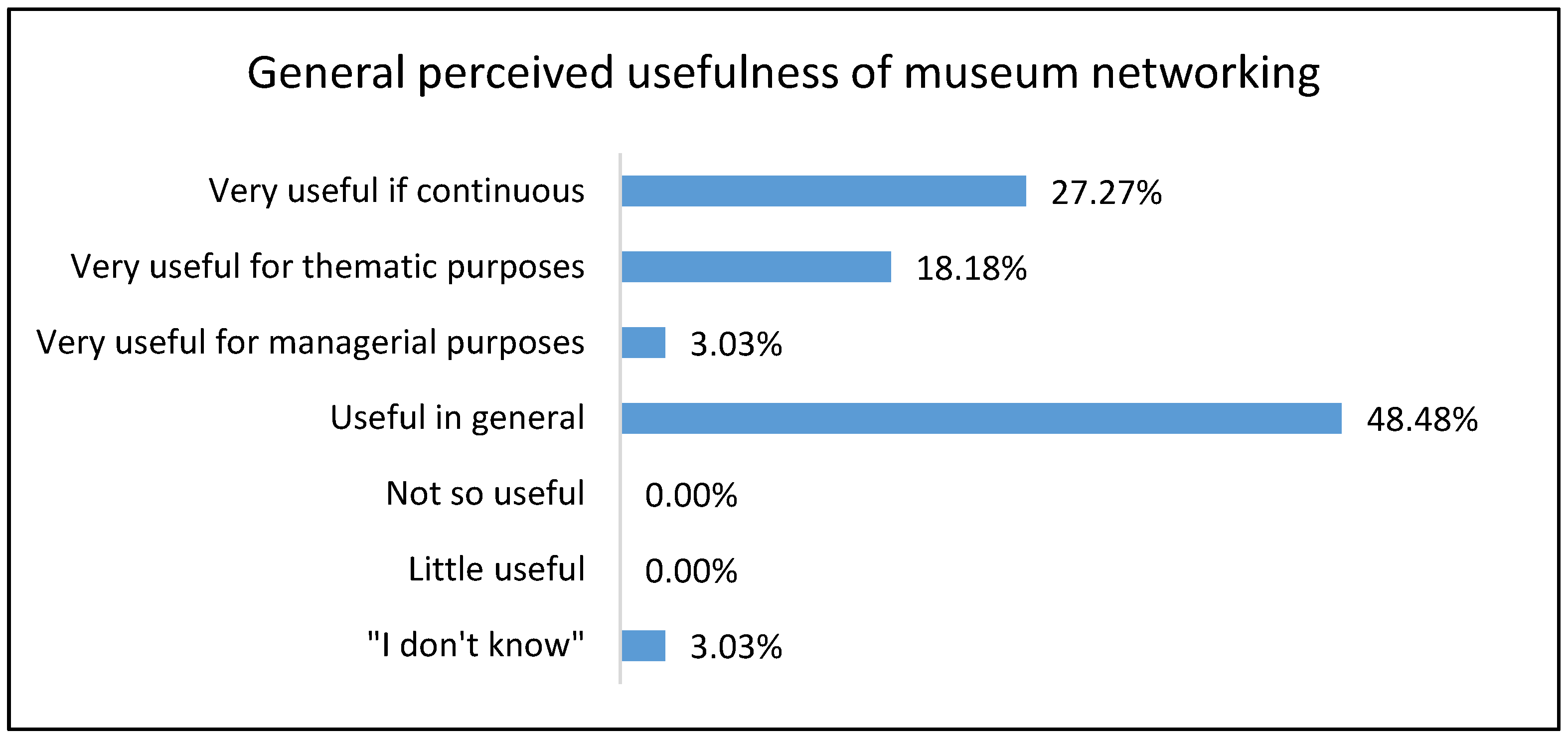

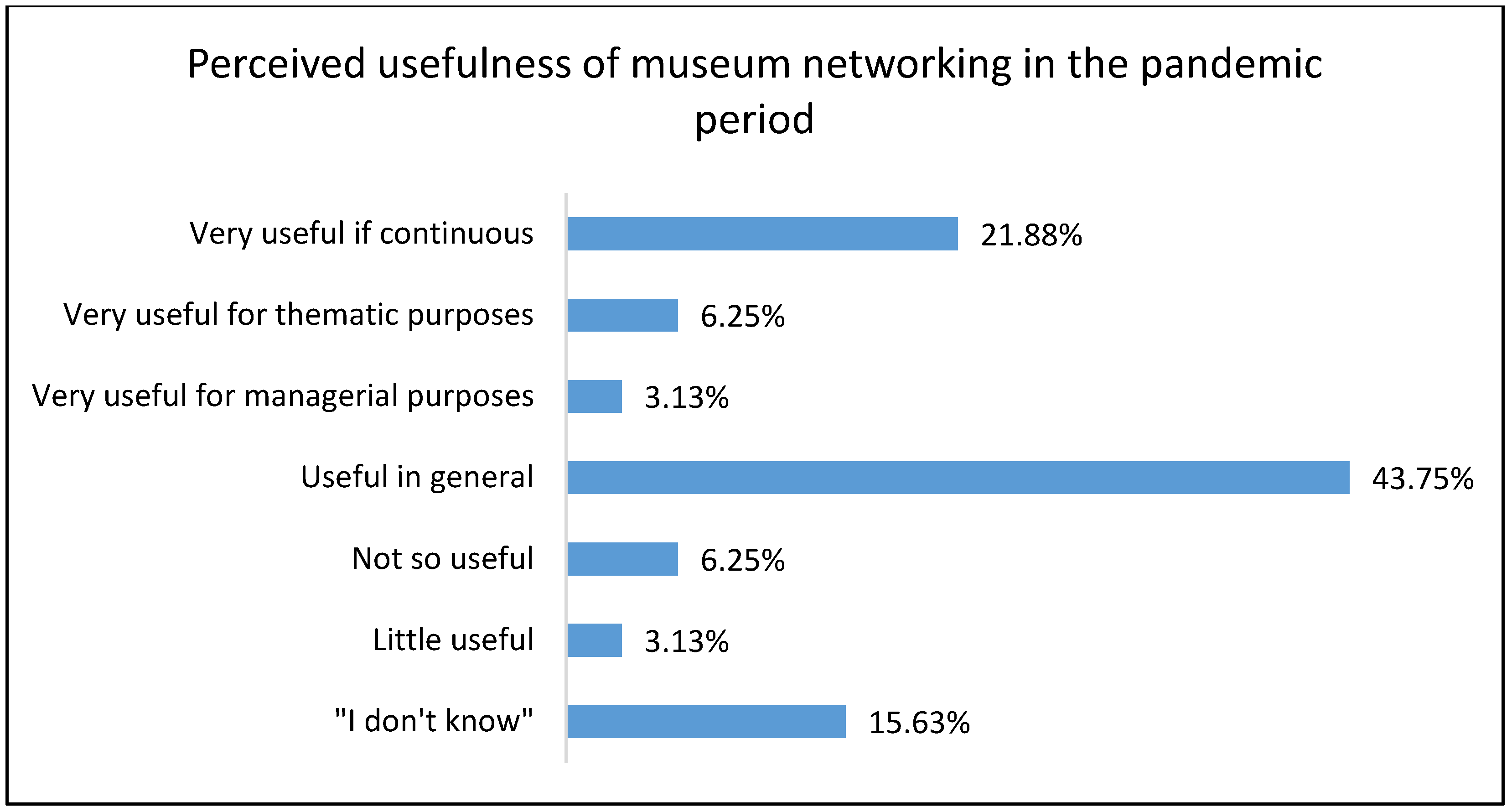

- Museum networking

- Connections/collaborations established with other museums from the local or national territory, purposes (thematic or managerial);

- perceived usefulness of museum networking, in general and with specific reference to the lockdown period.

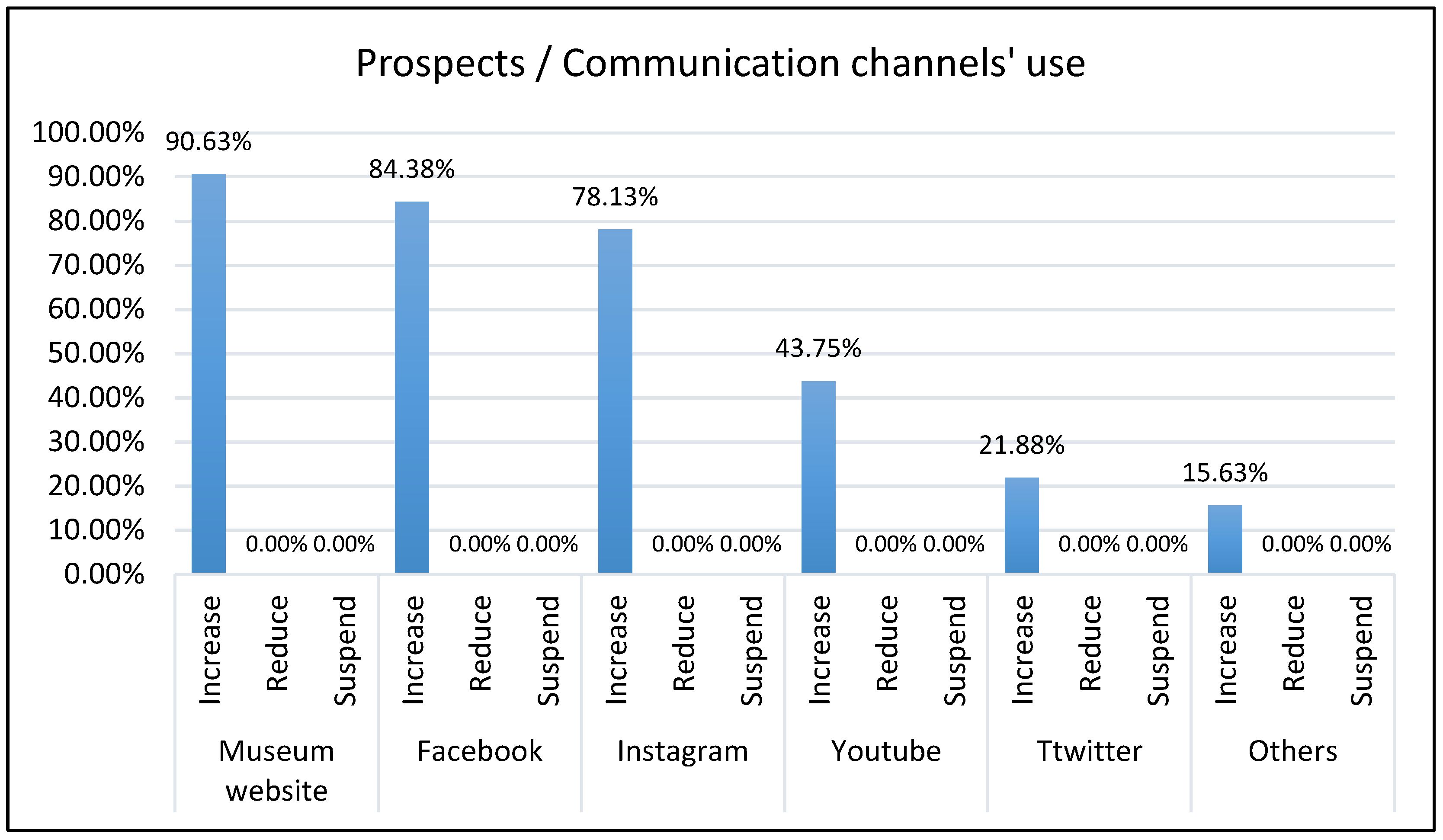

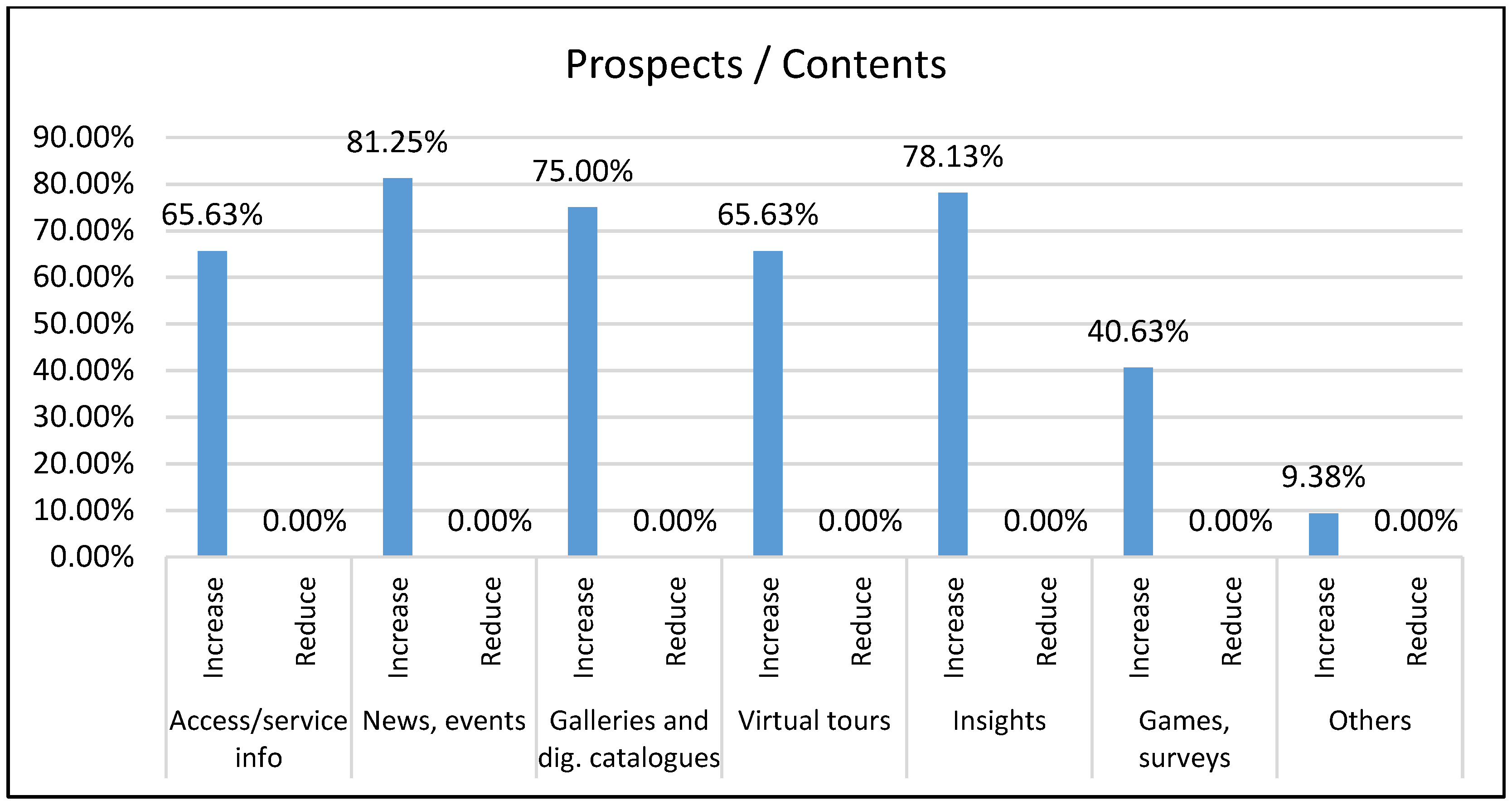

- Prospects

- Previsions on future use of the different communication channels (increase, reduction, dropout) and motivations;

- previsions on future feeding of the different content or sections of communication channels (enriching, reducing) and motivations;

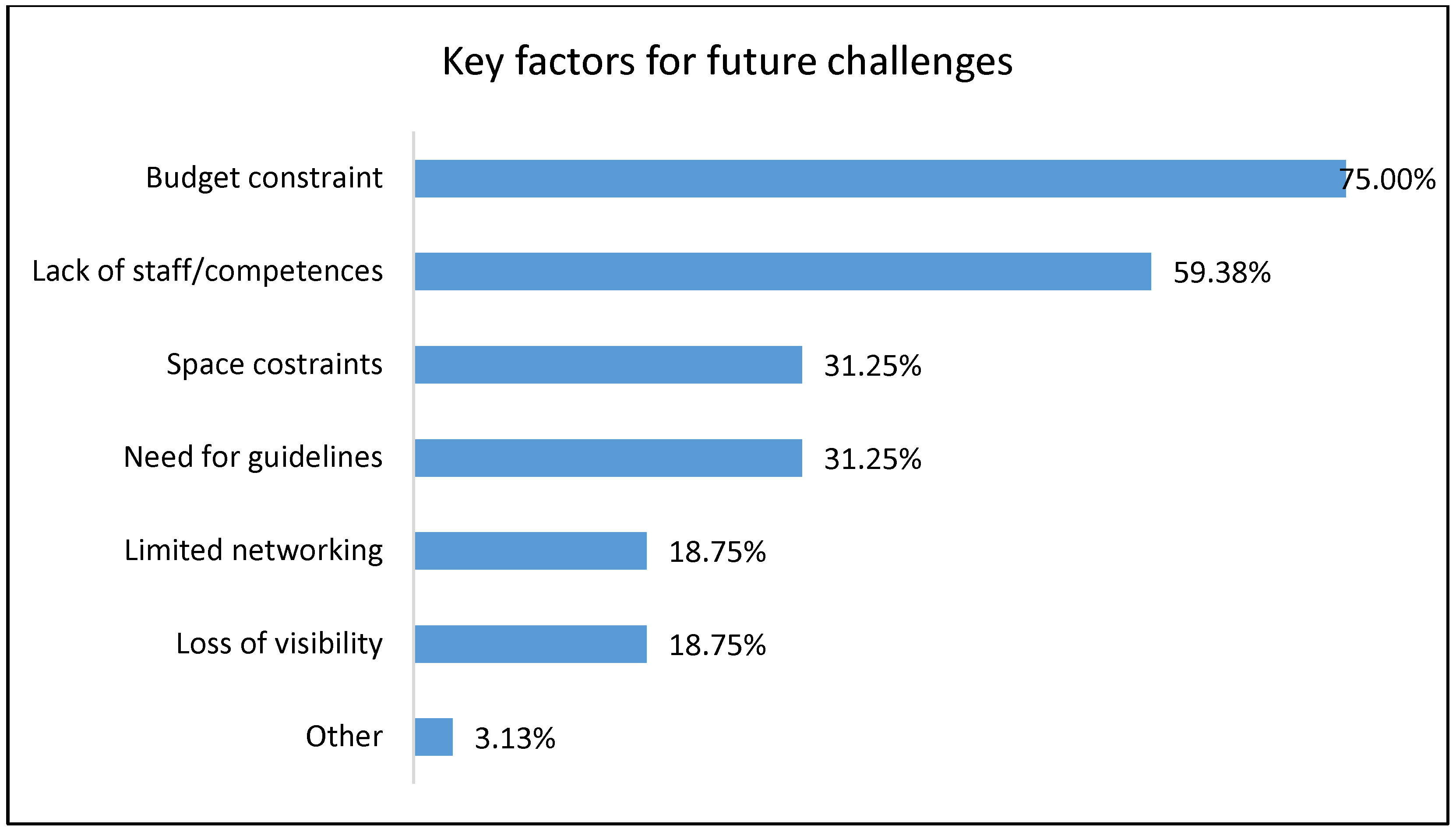

- most concerning challenges for the museum’s future competitiveness;

- key factors requiring specific attention and practical solutions to address such challenges at best.

5. Results

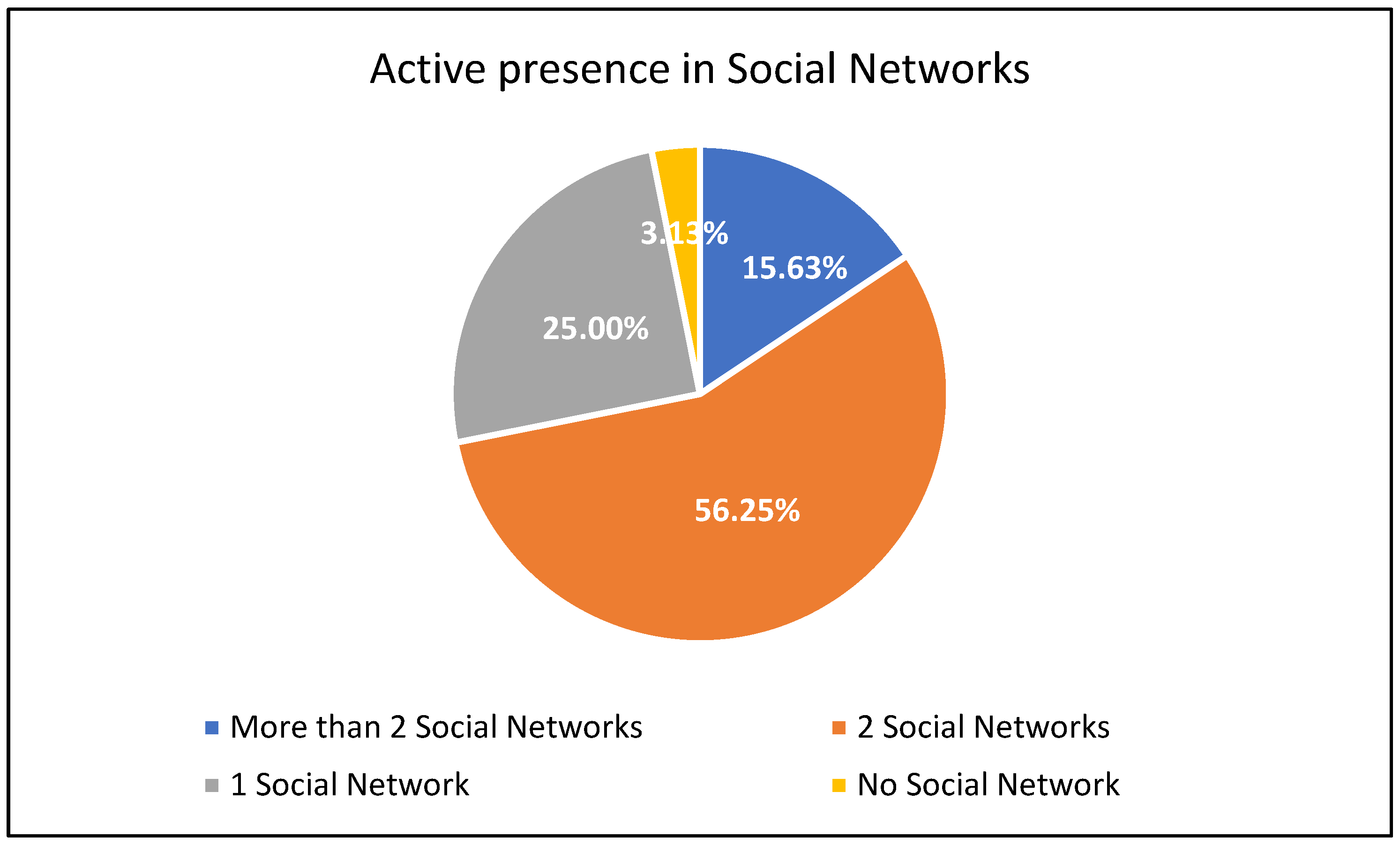

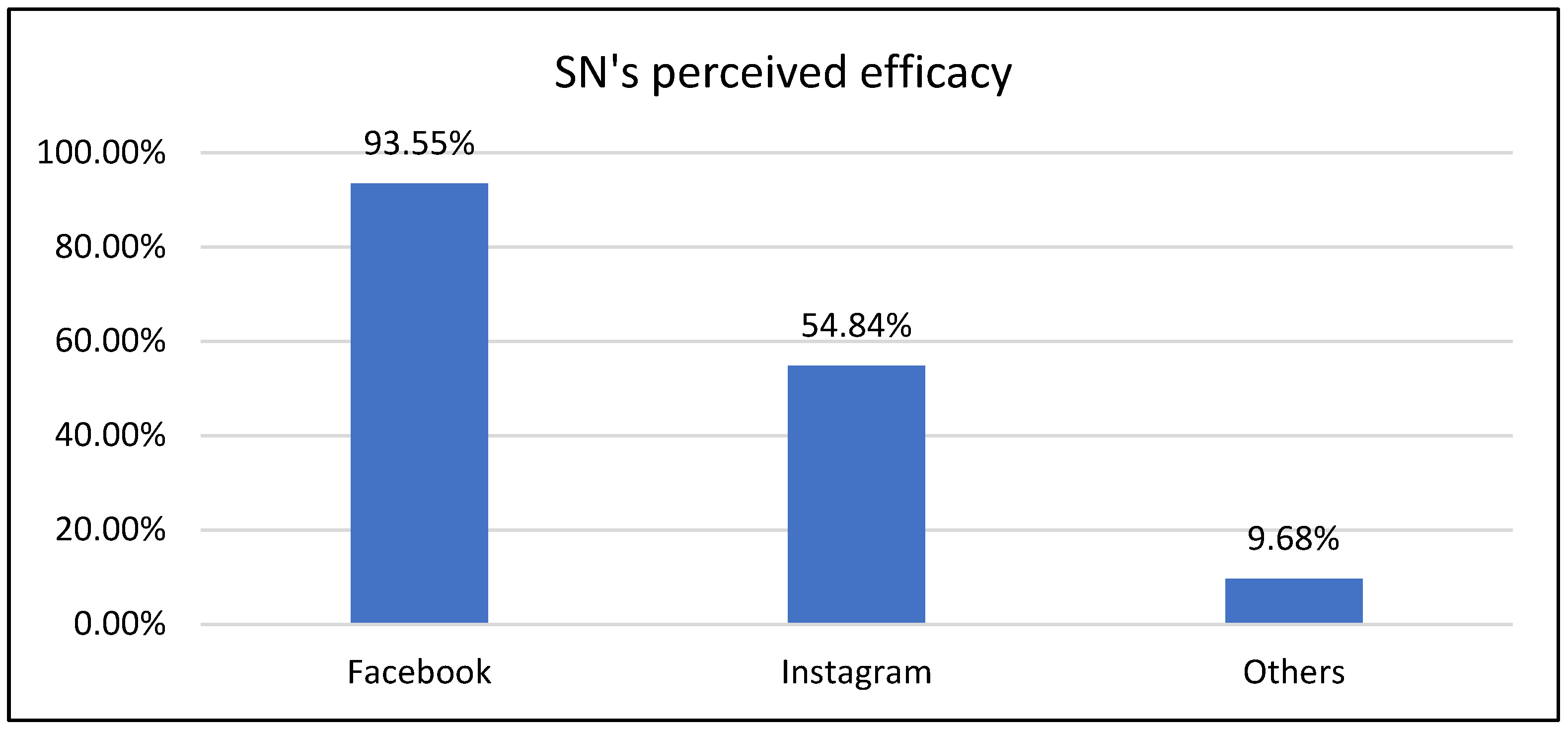

5.1. On-Line Communication

5.2. Digital Content and Digitization Issues

5.3. Museum Networking

5.4. Prospects

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). Report Museums, Museum Professionals and COVID-19. May 2020. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Report-Museums-and-COVID-19.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- International Council of Museums (ICOM). Report Museums, Museum Professionals and COVID-19: Follow-Up Survey. November 2020. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FINAL-EN_Follow-up-survey.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Museums Around the World in the Face of COVID-19. May 2020. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373530 (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- American Alliance of Museums (AAM). National Survey of COVID-19 Impact on United States Museums. July 2020. Available online: https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2020_National-Survey-of-COVID19-Impact-on-US-Museums.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Network of European Museum Organizations (NEMO). Survey on the Impact of the COVID-19 Situation on Museums in Europe—Final Report. May 2020. Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/NEMO_documents/NEMO_COVID19_Report_12.05.2020.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Pescarin, S. Museums and Virtual Museum in Europe: Reaching Expectations. Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2014, 4, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Radice, S. Designing for Audience Participation within Museums: Operative Insights from “Everyday History”. Int. J. Incl. Mus. 2014, 6, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, S. The Museum Evolution and Its Adaptation, Culture & Development. 2012, Volume 8, pp. 38–44. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000219726_eng (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Lerario, A. Languages and Context Issues of ICTs for a New Role of Museums in the COVID-19 Era. Heritage 2021, 4, 3065–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOM. Definition of Museum. 2007. Available online: https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020_ICOM-Czech-Republic_224-years-of-defining-the-museum.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2022).

- Ciolfi, L.; Bannon, L. Designing hybrid places: Merging interaction design, ubiquitous technologies and geographies of the museum space. Codesign 2007, 3, 159–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamantia, N. Il Museo—L’evoluzione Dell’esposizione Museale. Ph.D. Thesis, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Naples, Italy, 2016. Available online: http://www.fedoa.unina.it/11167/1/Lamantia.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Baradaran Rahimi, F. Hybrid Space: Re-Thinking Space and the Museum Experience. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 26 April 2019. Downloaded from PRISM Repository, University of Calgary. Available online: https://prism.ucalgary.ca (accessed on 28 November 2022).

- Waern, A.; Løvlie, A. Hybrid Museum Experiences: Theory and Design; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudhawasth, C.M. Museum as A Health and Wellbeing Facilitator in Pandemic Era: A Perspective from Museum Communication. J. Scr. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šveb Dragija, M.; Jelinčić, D.A. Can Museums Help Visitors Thrive? Review of Studies on Psychological Wellbeing in Museums. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser Travagli, A.M. Quale pubblico per I musei italiani? Archeol. Viva 2016, 179, 68–71. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/41659163/QUALE_PUBBLICO_PER_I_MUSEI_ITALIANI (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Turkle, S. Alone Together; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA; Perseus Books Group: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780465093663. Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=Utk4DgAAQBAJ&hl=it&source=gbs_book_other_versions (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Jalla, D. La “Riforma” Dei Musei Statali Italiani. Museo In-Forma, 2015—N.52 Speciale Riforma del MiBACT per i musei—Pag. 9. Available online: http://www.sistemamusei.ra.it/main/index.php?id_pag=99&op=lrs&id_riv_articolo=907 (accessed on 29 November 2022).

- Popescu, R.I. Communication Strategy of The National Museum of Natural History “Grigore Antipa”. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2007, 19E, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, R.; Minuti, M.; Ristuccia, M.S.; Diamanti, E.; Ferraro, V. I casi di studio. In Rivista Trimestrale dell’Associazione per l’Economia della Cultura; Economia della Cultura: Rome, Italy, 2012; pp. 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A. Museum-iD. Data-Driven Strategies for Delivering Web and Mobile for Museums. 2013. Available online: https://museum-id.com/data-driven-strategies-delivering-web-mobile-museums-andrew-lewis/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Price, K. V&A Academy. Getting the Most from Digital Media. October 2017. Available online: https://www.vam.ac.uk/event/Q6DWbyNg/getting-the-most-from-digital-media-oct-2017 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Pronk, M. museOn forscht. Inventing the Digital Rijksmuseum. Available online: https://www.museon.uni-freiburg.de/museon-forscht-2016-tagungspublikation/museon-forscht-2016-tagungspublikation_inventing-the-digital-rijksmuseum (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Alexandrou, E. Digital Strategy in Museums: A Case Study of The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Master’s Thesis, Business Administration & Legal Studies, School of Economics, Thessaloniki, Greece, January 2020. Available online: https://repository.ihu.edu.gr/xmlui/handle/11544/29516 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Fallon, J. How the Renovation of a World Renowned Art Museum is Inspiring a Sector in Digital Transformation. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/post/how-the-renovation-of-a-world-renowned-art-museum-is-inspiring-a-sector-in-digital-transformation (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- The Future Museum Project, Case Cards—Which Digital Strategies Make Sense in A Museum and How Can They Enhance Analogue Formats?/How Can Digitalisation Be Integrated in A Sustainable Way in The Organisational Structure of Museums? Available online: https://www.future-museum.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Case-Cards_Which-digital-strategies-make-sense-in-a-museum-and-how-can-they-enhance-analogue-formats.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Ministero della Cultura. Mann: A Napoli Il Museo Archeologico È Più Social E Digitale. 2020. Available online: https://ponculturaesviluppo.beniculturali.it/mann-a-napoli-il-museo-archeologico-e-piu-social-e-digitale/#:~:text=Il%20MANN%2C%20uno%20dei%20principali,di%20valorizzazione%20digitale%20all’utenza (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Gonzalez, R. Keep the Conversation Going: How Museums Use Social Media to Engage the Public. Mus. Sch. 2017, 1. Available online: https://articles.themuseumscholar.org/2017/02/06/vol1no1gonzalez/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Chung, T.; Marcketti, S.; Fiore, A.M. Use of social networking services for marketing art museums. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2014, 29, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulus, H. A review of museums in the context of communication and marketing. J. Int. Mus. Educ. 2021, 3, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamariotou, V.; Kamariotou, M.; Kitsios, F. Digital transformation strategy initiative in cultural heritage: The case of Tate Museum. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the EuroMed 2020: Digital Heritage. Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection, Virtual Event, 2–5 November 2020; Ioannides, M., Fink, E., Cantoni, L., Champion, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12642, Chapter 25; pp. 300–310. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-73043-7_25 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Capriotti, P. Managing Strategic, Communication in Museums. The case of Catalan museums. Commun. Soc. Comun. Y Soc. 2013, 26, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, A.A.; Smolskaya, E.P. Cadiz Museum and Its Communication Strategy. Lat.-Am. Hissotrical Alm. 2021, 29, 174–195. Available online: https://ahl.igh.ru/issues/19/articles/172?locale=es (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Camarero, C.; Garrido, M.J.; San José, R. Efficiency of Web Communication Strategies: The Case of Art Museums. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2016, 18, 42–62. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44989650 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Asensio, M.; Asenjo, E. Lazos de Luz Azul: Museos y Tecnologías 1, 2 y 3.0; Universitat Oberta de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2011; ISBN 9788490290439. Available online: https://searchworks.stanford.edu/view/10628439 (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Capriotti, P.; Kukliński, H. Assessing Dialogic Communication Through the Internet in Spanish Museums. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodzińska, K. From A Visitor to Participant. Strategies for Participation in Museums. Zarządzanie W Kult. 2017, 18, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechita, F. The New Concepts Shaping the Marketing Communication Strategies of Museums. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Braşov Ser. VII Soc. Sci. 2014, 7, 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland Bow, J.A. The Creative Museum—Analysis of Selected Best Practices from Europe; Siung, J., Ed.; Chester Beatty Library. 2016. Available online: https://creative-museum.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/analysis-of-best-practices.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Aerni, J.; Schegg, R. Museums’ Use of Social Media Results of an Online Survey Conducted in Switzerland and Abroad; Institute of Tourism, HES-SO Valais: Sierre, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva, N. Museums in social media. In Proceedings of the MWF2014: Museums and the Web, Florence, Italy, 18–21 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Özdemir, G.; Çelebi, D. A Social Media Framework of Cultural Museums Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Research (AHTR). Int. J. Akdeniz Univ. Tour. Fac. 2017, 5, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Laws, A.L. Social Network Sites (SNS) and Digital Culture: Developing the Online Strategy of the Panama Viejo Museum (Chapter). In Digital Culture and E-Tourism: Technologies, Applications and Management Approaches; Lytras, M., Ordóñez de Pablos, P., Damiani, E., Diaz, L., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Museums Association; Atkinson, R. Virtual Object Handling. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5274741/Virtual_object_handling_Museums_Association (accessed on 6 December 2022).

- Gabellone, F.; Giuri, F.; Ferrari, I.; Chiffi, M. What communication for museums? Experiences and reflections in a virtualization project for the Museo Egizio in Turin. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies, Vienna, Austria, 2–4 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppantonio Di Franco, P.; Matthews, J.L.; Matlock, T. Framing the Past: How Virtual Experience Affects Bodily Description of Artefacts. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 17, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, I.; Schreer, O.; Ebner, T.; Eisert, P.; Hilsmann, A.; Nonne, N.; Haeberlein, S. Digitization of People and Objects for Virtual Museum Applications. In Proceedings of the EVA Berlin 2016 Conference, Berlin, Germany, 9–11 November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, S.; Besser, H.; Borda, A.; Geber, K.; Lévy, P. Virtual Museum (of Canada): The Next Generation; Canadian Heritage Information Network (CHIN): Montreal, QC, Canada, 2003.

- Deshpande, S.; Geber, K.; Timpson, C. Engaged dialogism in virtual space: An exploration of research strategies for virtual museums. In Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage; Cameron, F., Kenderdine, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Caraceni, S. Comparison between virtual museums. SCIRES-IT Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2014, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, B. Virtual museums’ as digital collection complexes. A museological perspective using the example of Hans-Gross-Kriminalmuseum. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2017, 32, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.E. A New Medium for Old Masters: The Kress Study Collection Virtual Museum Project. Art Doc. J. Art Libr. Soc. North Am. 1998, 17, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzum, M. A Review of Museum Web Sites: In Search of User-Centred Design. Arch. Mus. Inform. 1999, 12, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, D.; Kritou, E.; Tudhope, D. Usability Evaluation for Museum Web Sites. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.L. Enhancing the Value of Museum Web Sites. J. Libr. Adm. 2003, 39, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.P.; Filippini-Fantoni, S. Personalization and the Web from a museum perspective. In Museums and the Web 2004, Proceedings of the International Conference Museums and the Web 2004, Arlington, VA, USA, 31 March–3 April 2004; Bearman, D., Trant, J., Eds.; Archives and Museum Informatics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004; pp. 63–78. Available online: http://www.archimuse.com/mw2004/papers/bowen/bowen.html (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Pallas, J.; Economides, A.A. Evaluation of art museums’ web sites worldwide. Inf. Serv. Use 2008, 28, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley-Huff, D.A. Design Insights and Inspiration from the Tate: What Museum Web Sites Can Offer Us, Portal: Libraries and the Academy; Project MUSE; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; Volume 9, pp. 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, R.M.; Abdullah, A.; Ramalingam, H. Learning of Web Quality Evaluation: A Case Study of Malaysia National Museum Web Site Using WebQEM Approach. In Taylor’s 7th Teaching and Learning Conference 2014 Proceedings; Tang, S.F., Logonnathan, L., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Singapore, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiseler, S.; Brüggemann, V.; Dörk, M. Tracing exploratory modes in digital collections of museum Web sites using reverse information architecture. First Monday 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoffield, S.; Liu, J. Online Marketing Communications and the Postmodern Consumer in the Museum context 2014. In Proceedings of the Cambridge Conference Business & Economics, Cambridge, UK, 1–2 July 2014; ISBN 9780974211428. Available online: https://cercles.diba.cat/documentsdigitals/pdf/E140146.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2022).

- Siglioccolo, M.; Perano, M.; Siano, A.; Pellicano, M.; Baxter, I. Exploring services provided by top Italian museums websites: What are they used for? Int. J. Electron. Mark. Retail. 2016, 7, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Azam, M.S. Linking Brand Image, Customer satisfaction, and Re-visit Intention: A Look at the Varendra Research Museum. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business and Sustainable Development (ICBSD), Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 8–9 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nina, S. The Participatory Museum; Museum 2.0: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780615346502. Available online: https://participatorymuseum.org/read/ (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Agostino, D.; Arnaboldi, M.; Diaz Lema, M. New development: COVID-19 as an accelerator of digital transformation in public service delivery. Public Money Manag. 2020, 41, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuningtyas, F.; Uljanatunnisa Hakim, L.; Intyaswati, D.; Prihatiningsih, W. Museum Nasional Program “Belajar Menari” Online During the COVID 19 Pandemic Through Social MediaInstagram. J. Sos. Hum. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, E.; Beresford, A.M.; Warwick, C.; Impett, L. Understanding levels of online participation in the U.K. museum sector. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2023, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, A.; Williams, S.; Nelson, G.; Manuel, M.; Dasgupta, S.; Gračanin, D. Redefining the Digital Paradigm for Virtual Museums. In Proceedings of the HCII 2021: Culture and Computing. Interactive Cultural Heritage and Arts, 9th International Conference, C&C 2021, Held as Part of the 23rd HCI International Conference, HCII 2021, Virtual Event, 24–29 July 2021. Proceedings, Part I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, R.B.; de Miguel Álvarez, L. Bibliographic review. Existence of virtual museums for educational purposes is applied to the professional environment. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2021, 4, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seung-Wan, J.; Kang, Z.; Dong, W. Studying the Factors of Virtual Museum Design on the Visitors’ Intention and Satisfaction. Rupkatha J. Interdiscip. Stud. Humanit. 2022, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qin, J. From digital museuming to on-site visiting: The mediation of cultural identity and perceived value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia Loureiro, S.M.; Rato, D. Stimulating the visit of a physical museum through a virtual one. Anatolia 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulon Soares, B. Defining the museum: Challenges and compromises of the 21st century. ICOFOM Study Ser. 2020, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Heras-Pedrosa, C.; Iglesias-Sánchez, P.P.; Jambrino-Maldonado, C.; López-Delgado, P.; Galarza-Fernández, E. Museum communication management in digital ecosystems. Impact of COVID-19 on digital strategy. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2022, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F.; Providência, F. Critical Digital: Digital Integration in the Museum. In Advances in Design and Digital Communication III; DIGICOM 2022; Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Martins, N., Brandão, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Network of European Museum Organizations (NEMO). Initiatives and Actions of the Museums in the Corona Crisis (NEMO Study, 6 April 2020). Available online: https://www.ne-mo.org/fileadmin/Dateien/public/NEMO_documents/Initiatives_of_museums_in_times_of_corona_4_20.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Erasmus + Sector Skills Alliances Mu.Sa: Museum Sector Alliance—Museum Professionals in The Digital Era. Agents of Change and Innovation Final Version. Available online: https://www.icom-italia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ICOMItalia.MUSA_.MuseumSectorAlliance.Professions.Digital.10ottobre.2018.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Sommer Paulsen, K. Successful Digital Transformation of Museums. AdventureLAB. 2021. Available online: https://www.planetattractions.com/news/Successful-digital-transformation-of-museums/188 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Roma Culture. Sovrintendenza Capitolina ai Beni Culturali. Il Sistema Musei di Roma Capitale. Available online: https://www.museodiroma.it/it/musei_digitali/i_mic_sui_social_network (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Sun, Y.; Zheng, Y. A Study of Visitor Interaction with Virtual Museum. In Communications in Computer and Information Science, Proceedings of the HCII 2022: HCI International 2022—Late Breaking Posters, Virtual Event, 26 June–1 July 2022; Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálosi, A. Designing Authenticity in Virtual Museum Tours. Pap. Arts Humanit. 2022, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatlı, Z.; Çelenk, G.; Altınışık, D. Analysis of virtual museums in terms of design and perception of presence. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadán-Guerrero, J.; Guevara, C.; Lara-Alvarez, P.; Sanchez-Gordon, S.; Calle-Jimenez, T.; Salvador-Ullauri, L.; Acosta-Vargas, P.; Bonilla-Jurado, D. Building Hybrid Interfaces to Increase Interaction with Young Children and Children with Special Needs. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Proceedings of the AHFE 2019: Advances in Human Factors and Systems Interaction; Washington, DC, USA, 24–28 July 2019, Nunes, I., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 959, pp. 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, B.M. Physical Versus Digital Museums: The User Experience. Master’s Thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, April 2015; 26p. [Google Scholar]

- Markopoulos, E.; Ye, C.; Markopoulos, P.; Luimula, M. Digital Museum Transformation Strategy Against the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Proceedings of the AHFE 2021: Advances in Creativity, Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Communication of Design, Virtual, 25–29 July 2021; Markopoulos, E., Goonetilleke, R.S., Ho, A.G., Luximon, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 276, pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranta, A.; Alexandri, E.; Kyprianos, K. Young people and museums in the time of COVID-19. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2021, 36, 632–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, G.; Dicuonzo, F.; Karacan, E.; Pastore, D. The Impact of Virtual Tours On Museum Exhibitions After The Onset of Covid-19 Restrictions: Visitor Engagement and Long Term Perspectives. Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2021, 11, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietroni, E. Experience Design, Virtual Reality and Media Hybridization for the Digital Communication Inside Museums. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2019, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R. Arts Management and Technology Management. The Hybrid Museum Experience: Case Studies in Digital Engagement and Experience Design. 2019. Available online: https://amt-lab.org/blog/2019/9/the-hybrid-museum-experience-case-studies-in-digital-engagement-and-experience-design-in-the-museum-space (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Puspasari, S.; Ermatita; Zulkardi. Innovative Virtual Museum Conceptual Model for Learning Enhancement During the Pandemic. In Proceedings of the 2022 11th Electrical Power, Electronics, Communications, Controls and Informatics Seminar (EECCIS), Malang, Indonesia, 23–25 August 2022; pp. 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, B.; Cengiz, E. Students’ opinions on the use of virtual museums in science teaching. Res. Educ. Psychol. (REP) 2023, 7, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristeidou, M.; Orphanoudakis, T.; Kouvara, T.; Karachristos, C.; Spyropoulou, N. Evaluating the usability and learning potential of a virtual museum tour application for schools. In Proceedings of the INTED 2023 Proceedings, Valencia, Spain, 6–8 March 2023; pp. 2572–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutsenko, S. Information Potential of Official Websites of The Museums of Cherkasy Region as a Source for Studying History of The Native Region At History Lessons; Uman State Pedagogical University: Cherkasy Oblast, Ukraine, 2023; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Lu, Y.; Martin, J. A Review of the Role of Social Media for the Cultural Heritage Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Yi, T.; Hong, S.; Lai, P.Y.; Jun, J.Y.; Lee, J.H. Identifying Museum Visitors via Social Network Analysis of Instagram. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2022, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanatidis, D.; Mylona, I.; Mamalis, S.; Kamenidou, I. Social media for cultural communication: A critical investigation of museums’ Instagram practices. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2020, 6, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsehyan, G.B. Digital Transformation in Museum Management: The Usage of Information and Communication Technologies. Turk. Stud. Soc. Sci. 2020, 15, 3539–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnic, I.; Vidak, I.; Kovacevic, M. The Application of Multimedia and Web 2.0 Technologies in Communicating and Interpreting Acultural Tourism Product. In Proceedings of the 72nd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development—Digital Transformation and Business, Varazdin, Croatia, 30 September–1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrova, S.; Spasova, S. Regional Libraries and Regional History Museums in Bulgaria in The Conditions of Lockdown: Social Network Case Study. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies, Online Conference, 5–6 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avgousti, A.; Papaioannou, G. The Current State and Challenges in Democratizing Small Museums’ Collections Online. Inf. Technol. Libr. 2023, 42, 14099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltadefinizione. La Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze e Haltadefinizione Insieme per un Museo Digitale, 16 September 2020. Available online: https://www.haltadefinizione.com/news-and-media/comunicati-stampa/la-galleria-dellaccademia-di-firenze-e-haltadefinizione-insieme-per-un-museo-digitale/ (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- Giannini, F.; Baratta, I. Finestre sull’Arte. Nuovi Modi Per Comunicare I Musei: Eccone Alcuni Che Si Stanno Distinguendo Nella Seconda Ondata. 21 November 2020. Available online: https://www.finestresullarte.info/focus/nuovi-modi-per-comunicare-i-musei-seconda-ondata-covid (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- De Bernardi, P.; Gilli, M. Museum Digital Innovation: The Role of Digital Communication Strategies in Torino Museums. In Handbook of Research on Examining Cultural Policies Through Digital Communication; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Indagine Sui Musei E Le Istituzioni Similari—Anno 2019—Aspetti Metodologici Dell’indagine. 2020. Available online: https://www.istat.it/microdata/download.php?id=/import/fs/pub/wwwarmida/204/2020/01/Nota.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- ISTAT. Musei E Istituzioni Similari in Italia—ANNO 2020. 17 February 2022. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2022/02/REPORT_MUSEI-E-ISTITUZIONI-SIMILARI-IN-ITALIA.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Minucciani, V.A.P.M. Quanti Sono I Piccoli Musei in Italia? 7 February 2019. Available online: https://www.piccolimusei.com/quanti-sono-i-piccoli-musei-in-italia/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- ISTAT. I Musei, le Aree Archeologiche E I Monumenti in Italia Anno 2017. 2019. Available online: https://www.journalchc.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/reportmusei_2017.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- ANMLI—Associazione Nazionale Musei Locali Italiani. Available online: https://www.associazioneanmli.it/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- APM—Associazione Nazionale Piccoli Musei. Available online: https://www.piccolimusei.com/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Regio Decreto 30 Gennaio 1913, n. 363 Regolamento di Esecuzione Delle Leggi 20 Giugno 1909, n. 364, e 23 Giugno 1912, n. 688, Per Le Antichità E Le Belle Arti. Available online: https://www.antiquariditalia.it/download/associazione/legislazione/Regio_Decreto_363_1913.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Benedetti, B. Il Concetto E L’evoluzione Del Museo Come Premessa Metodologica Alla Progettazione Di Modelli 3D, SCIRES-IT. Sci. Res. Inf. Technol. 2013, 3, 87–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso Peressut, G.L. Il Museo Moderno. Architettura e museografia da Perret a Kahn; Lybra Immagine: Milan, Italy, 2005; ISBN 8882230694. [Google Scholar]

- Varni, A. Storia e Futuro. I Musei Fra Passato E Futuro. Rivista di Storia e Storiografia Contemporanea online. Archivi, Numero 32—Giugno 2013. Available online: https://storiaefuturo.eu/i-musei-fra-passato-e-futuro/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Morbidelli, G. I Musei Civici Italiani Fra Tradizione e Innovatività, Aedon, Numero 1. 2021. ISSN 1127-1345. Available online: http://www.aedon.mulino.it/archivio/2021/1/morbidelli.htm (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Mottola Molfino, A. Saper Vedere I Musei, Treccani—Italia Nostra; ISBN 978-88-12-00633-5. Available online: https://www.italianostraeducazione.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Saper-vedere-i-musei.compressed.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Maccabruni, S. Il Museo che vive. L’evoluzione Del Ruolo Sociale dal Museo Moderno al Museo Contemporaneo—Lettura critica del Testo: Il Museo Moderno. Architettura e Museografia da Auguste Perret a Louis I. Kahn, di Luca Basso Peressut. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/20012626/Il_Museo_che_vive_L_evoluzione_del_ruolo_sociale_dal_Museo_Moderno_al_Museo_Contemporaneo (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Università degli Studi di Milano. Convegno ICOM Italia Il Museo in Evoluzione: Verso Una Nuova Definizione. 2019. Available online: https://lastatalenews.unimi.it/museo-evoluzione-verso-nuova-definizione (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Cosenza, G. Il Sole 24 Ore. Il Sistema Museale Nazionale Accredita più di 200 musei. 21 May 2021. Available online: https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/il-sistema-museale-nazionale-accredita-piu-200-musei-AEKL5HM (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Montella, M. Regioni e Musei Locali: Obiettivi e Comportamenti. Il Capitale Culturale: Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage, Supplemento Speciale; 2020; pp. 417–425, ISSN 2039-2362, ISBN 978-88-6056-671-3. Available online: https://riviste.unimc.it/index.php/cap-cult/article/view/2431/1827 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- ICOM Italia. Reti e Sistemi. Available online: https://www.icom-italia.org/reti-e-sistemi/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Ministero della Cultura, MuD. Museo Digitale—Idee a Confronto per l’innovazione Del Web Culturale. Available online: https://www.musei.molise.beniculturali.it/progetti/mud-museo-digitale (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Ministero della Cultura. Piano Nazionale di Digitalizzazione del Patrimonio Culturale. Release Consultazione—Italia. 6 July 2022. Available online: https://docs.italia.it/italia/icdp/icdp-pnd-docs/it/consultazione/index.html (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- COR-COM. Digitale in Frenata Per Musei e Teatri, solo 1 su 5 ha Una Strategia. 7 June 2022. Available online: https://www.corrierecomunicazioni.it/digital-economy/digitale-in-frenata-per-musei-e-teatri-solo-1-su-5-ha-una-strategia/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Monti, S. Artribune. E’ Ora Che I Piccoli Musei Facciano Sentire La Loro Voce. 10 February 2023. Available online: https://www.artribune.com/professioni-e-professionisti/politica-e-pubblica-amministrazione/2023/02/piccoli-musei/ (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Jalla, D. Regioni e Musei. In Istituzioni; Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana: Roma, Italy, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 519–544. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/13314255/Regioni_e_musei_2015_ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Solima, L. L’offerta di beni culturali (musei ed aree archeologiche) nel mezzogiorno. In Mezzogiorno E Beni Culturali—Caratteristiche, Potenzialità E Policy Per Una Loro Efficace Valorizzazione (Report); SRM-Studi e ricerche per il Mezzogiorno; Cuzzolin S.R.L.: Napoli, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-88-87479-36-2. [Google Scholar]

- Imperiale, F.; Terlizzi, V. Musei, raccolte e collezioni in Puglia. Il Cap. Cult. Stud. Value Cult. Herit. 2013, 6, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regione Puglia. CartApulia—La Carta dei Beni Culturali Pugliesi. Available online: https://cartapulia.it/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Ministero Della Cultura—Direzione Regionale Musei Puglia. Polo Regionale Puglia: Elenco Musei. Available online: https://musei.puglia.beniculturali.it/musei/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Mediateur. Cultura Turismo Territori, Reti E Sistemi Culturali in Puglia. 24 September 2021. Available online: https://mediateur.it/reti-e-sistemi-culturali-in-puglia/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Rete Museale “Uomo di Altamura”. Available online: https://uomodialtamura.it/go/16/l-uomo-di-altamura.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Raimo, N.; De Turi, I.; Ricciardelli, A.; Vitolla, F. Digitalization in the cultural industry: Evidence from Italian museums. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, ahead of print. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350278503_Digitalization_in_the_cultural_industry_evidence_from_Italian_museums (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Natali, V. Musei di Puglia—Bari, Brindisi, Foggia, Lecce, Taranto; Edipuglia: Bari, Italy, 2006; ISBN 88-7228-379-5. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, D. L’uso dei media da parte dei musei nell’era della pandemia COVID-19: Criticità e potenzialità. Media Educ. 2020, 11, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budge, Κ.; Burness, A. Museum objects and Instagram: Agency and communication in digital engagement. J. Media Cult. Stud. 2017, 32, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalaki, V.V.; Voutsa, M.C.; Boutsouki, C.; Hatzithomas, L. Service quality, visitor satisfaction and future behavior in the museum sector. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2020, 6, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, M.; Grit, A. Contemporary Dutch Museums in a Post-Covid Era. Acad. Lett. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaberge, E. La fruizione del patrimonio culturale tra spettacolarizzazione e forme narrative. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Torino, Torino, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto Ministeriale 23 dicembre 2014, Organizzazione Dei Musei Statali. Available online: http://www.beniculturali.it/mibac/multimedia/MiBAC/documents/feed/pdf/DM%20del%2023%20dicembre%202014-imported-49315.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- D.M. 10 maggio 2001. Atto di Indirizzo Sui Criteri Tecnico- Scientifici E Sugli Standard Di Funzionamento E Sviluppo Dei Musei (Art. 150, comma 6, del D.Lgs. n. 112 del 1998) G.U. 19 ottobre 2001, n. 244, S.O. Available online: http://www.toscana.beniculturali.it/index.php?it/208/gli-standard-museali (accessed on 21 April 2023).

| Communication Mode | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Museum websites (active) | 59.38% | 40.63% |

| Active accounts in SNs | 96.88% | 3.13% |

| SN | Active | Dormant | Absent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 96.88% | 0.00% | 3.13% | |

| 68.75% | 3.13% | 28.13% | |

| YouTube | 15.63% | 9.38% | 75.00% |

| 9.38% | 9.38% | 56.25% | |

| Other | 15.63% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Activation Period | % |

|---|---|

| Before the pandemic outbreak | 78.13% |

| During/after the lockdown | 18.75% |

| N/A = no answer | 3.13% |

| Use | App | Dig. Catalogues | 3D Models | Virtual Tours | Online Lessons | Didactic Labs | Podcast | Video | Audio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-site | 3.13% | 0.00% | 15.63% | 3.13% | 0.00% | 84.38% | 6.25% | 12.50% | 15.63% |

| Remote | 6.25% | 53.13% | 25.00% | 71.88% | 78.13% | 3.13% | 43.75% | 3.13% | 3.13% |

| Both | 81.25% | 43.75% | 50.00% | 18.75% | 15.63% | 9.38% | 34.38% | 78.13% | 71.88% |

| N/A | 9.38% | 3.13% | 9.38% | 6.25% | 6.25% | 3.13% | 15.63% | 6.25% | 9.38% |

| Products/Tools | Period | Children | Young People | Adults | Elderly | Scholars | Schools | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apps | LD | 6.25% | 9.38% | 12.50% | 3.13% | 3.13% | 12.50% | 62.50% |

| PT | 6.25% | 18.75% | 15.63% | 3.13% | 3.13% | 6.25% | 59.38% | |

| Digital catalogues | LD | 3.13% | 9.38% | 15.63% | 6.25% | 15.63% | 15.63% | 53.13% |

| PT | 3.13% | 9.38% | 12.50% | 6.25% | 12.50% | 9.38% | 56.25% | |

| 3D models | LD | 9.38% | 18.75% | 18.75% | 9.38% | 12.50% | 12.50% | 59.38% |

| PT | 18.75% | 15.63% | 21.88% | 6.25% | 12.50% | 21.88% | 53.13% | |

| Virtual tours | LD | 15.63% | 28.13% | 37.50% | 6.25% | 15.63% | 28.13% | 46.88% |

| PT | 9.38% | 12.50% | 18.75% | 0.00% | 6.25% | 21.88% | 43.75% | |

| Online lessons | LD | 15.63% | 28.13% | 18.75% | 9.38% | 9.38% | 34.38% | 40.63% |

| PT | 6.25% | 12.50% | 12.50% | 6.25% | 6.25% | 18.75% | 50.00% | |

| Didactic labs | LD | 18.75% | 25.00% | 9.38% | 3.13% | 3.13% | 25.00% | 56.25% |

| PT | 65.63% | 56.25% | 15.63% | 0.00% | 9.38% | 59.38% | 9.38% | |

| Podcast | LD | 6.25% | 9.38% | 12.50% | 9.38% | 9.38% | 9.38% | 65.63% |

| PT | 6.25% | 6.25% | 3.13% | 0.00% | 3.13% | 9.38% | 62.50% | |

| Video | LD | 25.00% | 37.50% | 50.00% | 18.75% | 25.00% | 37.50% | 34.38% |

| PT | 34.38% | 43.75% | 43.75% | 28.13% | 28.13% | 37.50% | 25.00% | |

| Audio | LD | 12.50% | 21.88% | 28.13% | 18.75% | 18.75% | 18.75% | 50.00% |

| PT | 9.38% | 12.50% | 9.38% | 15.63% | 9.38% | 18.75% | 46.88% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lerario, A. The Communication Challenge in Archaeological Museums in Puglia: Insights into the Contribution of Social Media and ICTs to Small-Scale Institutions. Heritage 2023, 6, 4956-4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070264

Lerario A. The Communication Challenge in Archaeological Museums in Puglia: Insights into the Contribution of Social Media and ICTs to Small-Scale Institutions. Heritage. 2023; 6(7):4956-4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070264

Chicago/Turabian StyleLerario, Antonella. 2023. "The Communication Challenge in Archaeological Museums in Puglia: Insights into the Contribution of Social Media and ICTs to Small-Scale Institutions" Heritage 6, no. 7: 4956-4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070264

APA StyleLerario, A. (2023). The Communication Challenge in Archaeological Museums in Puglia: Insights into the Contribution of Social Media and ICTs to Small-Scale Institutions. Heritage, 6(7), 4956-4992. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6070264