Abstract

One of the major public health measures to manage and contain the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic was to engage in systematic contact tracing, which required gastronomy, community and sporting venues to keep patron registers. Stand-alone and web-based applications, developed by a range of private IT providers, soon replaced pen-and-paper lists. With the introduction of a uniform, state-wide, mandatory data collection system, these private applications became obsolete. Although only active for four months, these applications paved the way for the public acceptance of state-administered collection systems that allowed for an unprecedented, centralized tracking system of the movements of the entire population. This paper discusses the cultural significance of these applications as a game changer in the debate on civil liberties, and addresses the question of how the materiality, or lack thereof, of this digital heritage affects the management of ephemeral smartphone applications, and its preservation for future generations.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage studies aim to observe, interpret, document and preserve the tangible and intangible manifestations of human interactions with each other and the environments they inhabit. Cultural heritage management is primarily concerned with the present generation: managing these tangible and intangible heritage assets for posteriority, based on an assumed benefit to future generations [1], by evaluating the cultural significance of the heritage assets and then engaging in processes and actions that prolong their existence in the face of technological obsolescence and environmental decay [2]. Given that the evaluation of cultural significance is based on hindsight, cultural heritage management, as a profession, has often struggled with the recognition and evaluation of recent and emerging heritage assets, as well as with over-the-horizon concepts [3].

Cultural heritage is commonly construed as a dichotomy between the tangible (e.g., objects, sites, structures, places) and intangible (e.g., traditions, customs, language, dance) domains of heritage assets [4,5,6]. The advent of electronic computing in the 1940s and its proliferation in the personal space with desktop machines in the 1980s, and smartphones in the 2000s, however, has added a third domain: virtual heritage. In this domain, human interactions with each other, or with human- or artificial-intelligence-designed applications, occur in an essentially ephemeral, virtual space, stored either in RAM or digital media, where all traces, as well all products of such interactions, also remain ephemeral until such time that they are printed out or documented with analogue media (i.e., ‘old fashioned’ silver nitrate film).

The heritage of twenty-first century digital realities is comprised of all three domains: tangible, intangible and virtual. As noted by Huggett, the majority of research into ‘digital archaeology,’ ‘digital heritage’ and ‘digital museology’ is concerned with the use of computers, digital technology and digital applications in the service of the archaeology, heritage and museum disciplines, rather than with the archaeology and heritage of computers and computing per se [7]. Indeed, searches in Google Scholar or Scopus for terms such as ‘digital heritage’, ‘heritage’ + ‘computer hardware’ or ‘heritage’ + ‘computer programs’ overwhelmingly return references for such research.

While there is an entire journal dedicated to the history of computing (IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, ISSN 1058-6180), only a very small number of papers have considered the tangible aspects, primarily the material culture of computing, such as mainframes [8], portable computers [9] or desktop publishing [10,11], as well as collections and collection methodologies dedicated to the history of computing [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. A limited number of other studies have looked at the intangible aspects of computing heritage, and primarily in terms of oral histories [22,23], software design [24] as well experiences when playing computer games [25].

Focusing on the digital domain, there is a growing body of literature that considers the need for the conservation, curation and interpretation of ‘born digital’ content [26,27,28,29,30,31]. This literature is, by and large, focused on the various editing stages of textual material, primarily literary matter [32,33], as well as news content data journalism [34,35]. In parallel, several authors have been concerned with the mechanics of digital audiovisual archiving, looking at storage techniques and technology, file standards and the use and maintenance of legacy machines as well as emulators [36,37,38].

As part of the recent convergence, voices have called for a holistic approach to digital heritage [39,40], noting that the preservation focuses primarily on content [41], rather than the ‘look-and-feel’ of the digital universe preserved or the underlying programming and functionality. A limited number of studies have ventured into this space [42], for example, using concepts of forensic, bibliographical archaeology to examine iterations of computer programs [43], as well as developing methodologies for the preservation, and study, of digital games [44]. In addition, conceptual papers have considered aspects of the sentience of AI systems when discussing the emerging and future heritage of robots [45].

As part of the research into the heritage of the COVID-19 pandemic and its management [46,47], this paper will examine the deployment of digital contact tracing registers in Australia and discuss their heritage in the context of digital and virtual heritage. It can be surmised that the digital applications and documents will, in the medium–long-term future, become a historic source akin to the present use of manuscripts and printed archival data. Given that this paper is an exploration and deliberation, it does not follow the standard IMRAD (introduction, methodology, results and discussion) format of papers.

2. Digital Registers for Tracing the Contacts of COVID-19-Positive Individuals

In early 2020, soon after COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus [48], rapidly developed into a global pandemic, many governments at the national or state levels enacted a range of public health measures to curb or at least slow its progress [49,50].

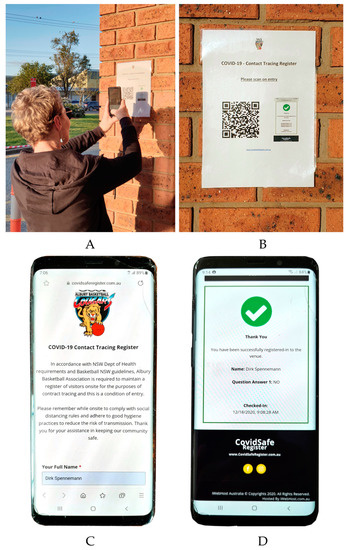

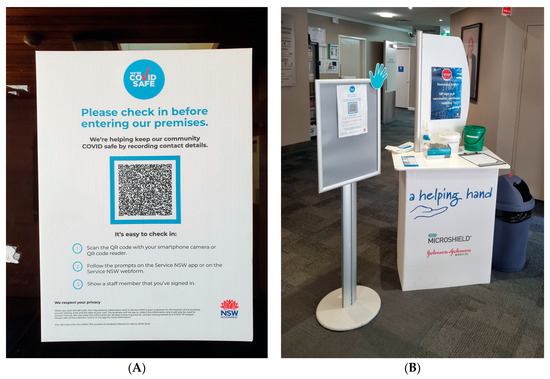

During the early days of the pandemic, public health departments engaged in epidemiological contact tracing to contain the spread of COVID-19 [51] (i.e., the identification and establishment of networks of people with whom a symptomatic patient could have come into contact while being infectious with SARS-CoV-2). To facilitate this, premises such as restaurants, cafés and bars, as well as sporting clubs, and later all shops, were required (as of 16 July 2020) to keep contact records (names, phone numbers, e-mails) of all staff, customers and patrons attending their venues [52]. While the initial systems were simply pen-and-paper-based lists placed on counters and maintained by each business [46], they carried the concomitant risk of infection through shared pens. In view of this risk, as well as the administrative burden of the additional recordkeeping involved with paper-based solutions, digital applications were soon created (as of 31 July 2020) [53], which allowed patrons to enter attendance data via their own smartphones. These systems were developed either as stand-alone applications, designed by small-scale web developers, or were offered as add-on modules to hospitality software published by major IT companies. These were web-based internet applications that could be readily accessed via quick response (QR) codes. Consequently, premises carried signs with their own QR codes (Figure 1A,B) linking to a website that collected the mandated contact information (Figure 1C,D). The uptake of these premises-based collection systems was rapid, leading to a proliferation of QR codes [54].

Figure 1.

COVID-19 check-in process with publicly posted QR code and resulting digital ephemera. (A) sign in in progress; (B) Sign-in notice with QR code; (C) Sign-in message screen on cell phone; (D) Confirmation of successful sign-in displayed on cell phone (Lauren Jackson Sports Centre, Albury, NSW, December 2020).

One provider, the New Zealand-based company Guest HQ, stated that over 5000 businesses had signed up to their services by September 2020 [55], while GuestTrack, operated by a Melbourne provider, had 3500 subscribers (with over 2 million check-ins) by the end of October 2020 [56]. Small-scale web firms, who offered these check-in systems altruistically as a community service (e.g., Nook), had a much smaller uptake of below 150 customers [57]. Premises that did not invest in digital data collection were required to continue maintaining a paper-based system [46], the open nature of which also posed privacy concerns [58].

While the datasets were supposed to be dynamic, with data older than four weeks (i.e., the then-calculated ‘standard’ SARS-CoV-2 incubation period plus an additional two weeks for tracing efforts) to be routinely discarded [56], unauthorised data retention for marketing purposes may well have occurred [59,60], especially where such check-in systems were provided free of charge to businesses [61]. The legitimacy of the data retention for marketing purposes depended on the terms of use applied by the venue or the provider of the ‘free’ applications [56], terms that most users never read or considered. Not surprisingly, some concerns about privacy and unauthorised data retention were raised [55]. Successful registration resulted in immediate verification via an acknowledgment screen (e.g., Figure 1D) and/or e-mail (Figure 2C).

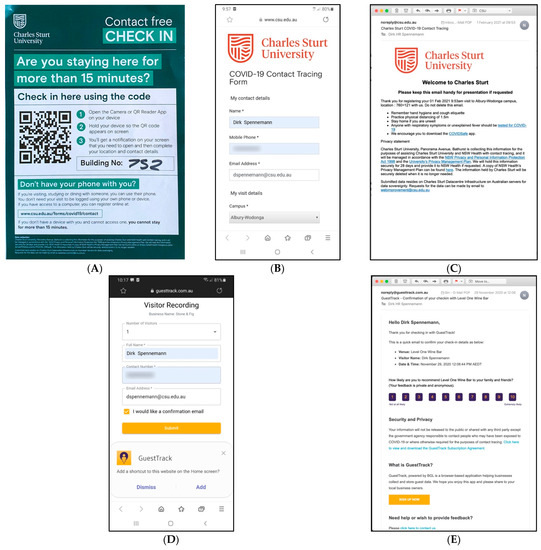

Figure 2.

Physical and digital ephemera—(A–C) Charles Sturt University, Albury; (D,E) Level 1 Winebar, Albury; (A) notification sheet at the entrance to a building; (B,D) screenshot of digital contact tracing application; (C,E) confirmation e-mail of successful notification. All images from December 2020 [46].

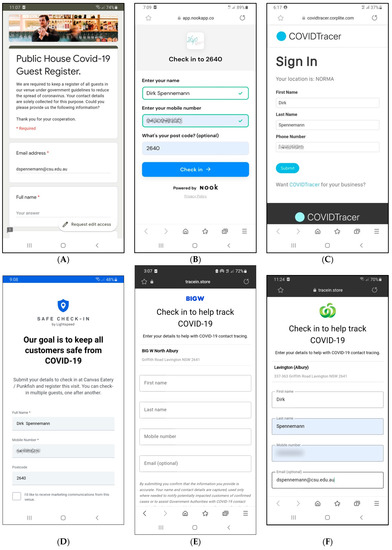

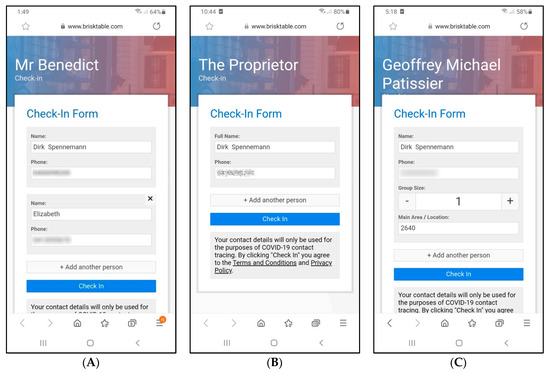

These web-based internet applications were provided by developers with a generic interface and then ‘customised’ by inserting the venue’s name, logo or imagery (Figure 3D and Figure 4. Larger corporations developed company-wide systems with store-specific recording (Figure 3E,F) [62]. One of the shortcomings of these systems was that users had no record of their own check-ins or movements, unless the application allowed for e-mail notifications (Figure 2) or the user took screenshots of the registration confirmation screen. Moreover, these applications were unidirectional, with users not being alerted if they may have been exposed to patrons who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at a later date.

Figure 3.

Digital ephemera—screenshots of data entry pages of various apps. (A) Public House (unknown provider); (B) Café 2640 (Nook); (C) Norma (Corplite Technologies); (D) Canvas (Lightspeed); (E,F) Woolworths Lavington (Woolworth Group) [46].

Figure 4.

(A–C) Digital ephemera—screenshots of the data entry pages of various Albury hospitality venues serviced by the same app interface (Brisk Cloudware Inc.) [46].

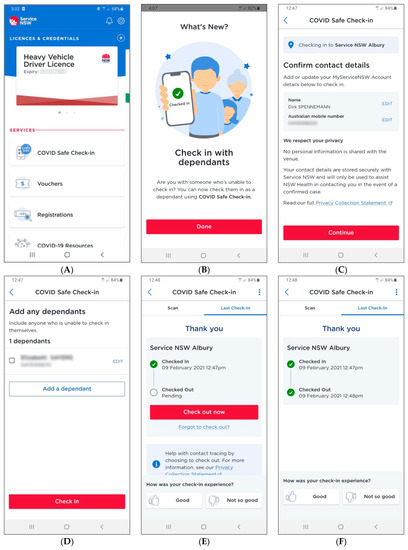

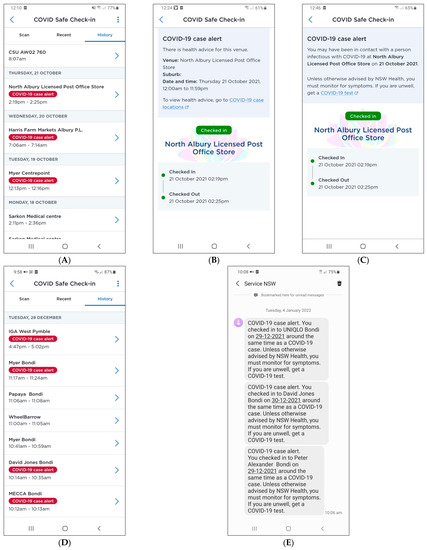

By 23 November 2020, the digital check-in became compulsory in New South Wales, [63], with the state health authorities requiring the use of the standardised, state-wide Service NSW app (Figure 5 and Figure 6) [64,65,66]. This effectively put an immediate end to the use of the applications developed by private providers. Following a brief grace period, these individual systems were phased out in favour of the mandated centralised state-based data collection run by Service NSW (Figure 6). Service NSW also generated personalized, printable COVID-19 check-in cards for people who did not own smartphones [67]. Other Australian states and territories soon followed with their similarly functioning systems. The major advantage of the centralised Service NSW application was that it allowed the public health department to notify users that they had visited a venue at the same time as a person who later on tested positive to COVID-19 (Figure 7). This allowed users to then get tested themselves.

Figure 5.

Physical ephemera—(A) Service NSW notification sheet (B) Service NSW notification sheet as part of a COVID-19 welcome and processing station. Both Albury Private Hospital, 30 June 2022.

Figure 6.

Digital ephemera—screenshots of a state-based digital contact tracing application. Attendance registration via the Service NSW app (all Albury NSW): (A) December 2020; (B–F) February 2021.

Figure 7.

Digital ephemera—screenshots of a state-based digital contact tracing application. Possible contact notification via the Service NSW app: (A–C) October 2021, Albury NSW; (D,E) January 2022, Sydney, NSW.

Even though only active for four months, the privately developed applications, with the varied interfaces, had become an accepted ‘way of life’ for the Australian public, and they paved the way for the easy transition to and adoption of the state-wide Service NSW app.

Effective 17 February 2022, QR check-ins at public venues were no longer required in NSW [68], and, as of 13 May 2022, were no longer required in the ACT [69]. While some people continued to use QR check-ins [70], the overall usage dropped soon after. The QR check-in systems remained in place for ‘at risk’ venues, however, such as aged care homes, medical centres and hospitals (Figure 3). As long as some venues retained the signage, some patrons chose to continue to use the system out of habit, or for reasons of peace of mind [71]. The QR check-in option of the Service NSW app was formally discontinued on 7 June 2022 [72].

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–2023 has proven to have been a cross-cultural, cross-sectoral and transnational disruptor on a truly global scale. It can be posited that the event will become the focus of social history exhibitions or retrospectives in the medium-term future. Thus, now is the time to act when processes are still in place and observable, when ephemeral sites can be documented [73] and when digital and physical artifacts are still able to be collected [47]. The remainder of this paper will focus on a set of short-lived digital artefacts that were generated by private businesses in response to and as part of the initial public health measures.

3. Methodology

3.1. Background

Between 2020 and 2023, the author systematically photographed, collected and documented examples of material culture associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Albury, a major regional service centre in southern New South Wales (NSW) at the border to Victoria (Australia) [46,50,73,74,75,76]. This is the only systematic and comprehensive documentation of its kind in Australia. Albury–Wodonga, with a regional population in excess of 150,000 people, can be regarded as a microcosmos of the Australian state of NSW, for which the findings of the various documentation efforts can be regarded as representative of the state and thus allow for extrapolation not only to NSW as a whole, but also to the Australian situation in general. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Albury community was equivalent to that of the rest of metropolitan and regional NSW—if not more so due to repeated border closures that impacted commuting workers [50].

3.2. Collection of QR Codes

The systematic documentation of COVID-19-related physical ephemera in 2020 provided numerous images of a number of public notification signs with QR codes for venue-based electronic contact registers (Table 1) [46]. These provided a starting point for the assessment of digital ephemera. Additional QR codes could be accessed via imagery posted on the internet (Table 2). In addition, a number of screenshots of smartphone applications and notifications were also collected during 2020 and 2021 [46,77].

Table 1.

Individual venue-based electronic contact registers documented for Albury (NSW).

3.3. Verification of QR Codes

To assess the active statuses of the web-based internet data collection systems, the QR codes (as reproduced on the notification sheets or the web) (Table 1 and Table 2) were scanned with a QR-reader-enabled cell phone. The resultant URLs (see Appendix, Table A1) were copied into a web browser. Where the site was still live, the underlying HTML coding was saved for documentation and research purposes, while the look and feel of the site were documented with screenshots both on a laptop and handheld smartphone device. Due to copyright issues, these HTML codes cannot be shared publicly at this point in time [78]. All identified URLs were also entered into Internet Archive’s WayBack Machine [79] to ascertain whether the page had been archived for posterity (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Individual venue-based electronic contact registers documented for other locations (IN: sourced via internet, no specific reference).

Table 2.

Individual venue-based electronic contact registers documented for other locations (IN: sourced via internet, no specific reference).

| Venue Name | Venue Class | Location | Status Feb 23 | WayBack Machine | Source | Provider | QR Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvest Breads & Café | Restaurant | Maroochydore, Qld | live | no | commercial | Guest Hq | [80] |

| Mr Wednesday | Restaurant | Melbourne, Vic | live | no | commercial | Corplite Technologies | [54] |

| Amalfi | Restaurant | ? | dead | no | commercial | UseNook | [81] |

| Three Blue Ducks | Restaurant | Byron Bay | dead | no | commercial | MyGuestlist | IN |

| Australian Open | Event | Melbourne, Vic | dead | no | commercial | Corplite Technologies | IN |

Most URLs were comprised of a webserver element and a venue-specific extension, which contained an alphanumeric string without a clear indication as to its configuration. Consequently, it was not possible to alter this alphanumeric string in a meaningful way to discover other venues serviced by the same provider. An exception were the URLs for the check-in forms for Woolworths and BigW stores (Table A1, URLs M and N) containing three- or four-digit numbers. Changes to the numbers brought up check-in forms for different stores of these chains.

4. Results

Canvassing the photographic dataset and web searches resulted in twenty venue-based electronic contact registers. Although no longer useful and valid, as they had been superseded by the Service NSW application since the end of November 2020, twelve of these COVID-19 attendance register sites were still functioning on 31 January 2022, and eleven on 31 October 2022, as well as on 6 February 2023. Only one of these sites, which was still ‘live,’ had been archived by a web crawler and could also be retrieved via the Internet WayBack Machine (Table 1).

Intriguingly, scanning a QR code of the venue-based private contact register sites still functioning in February 2023 (Table 1) not only served up the respective registration forms, but when they were filled out, also allowed the data to be sent to the provider, which resulted in a server response with a confirmation of the registration. For all practical purposes, therefore, these sites are still functioning as designed, although they are conceptionally obsolete.

The Service NSW “COVID safe check in” app remained active and functional until at least November 2022, as it was still used for potential contact tracing in some age care, medical practice and hospital settings. Scanning a QR code only activated the app and prefilled location-specific data that were automatically extracted from a database of locations. As the database has not been culled, QR codes of now-obsolete locations will continue to solicit a response. For example, the Service NSW QR collection code once used to register access to a Charles Sturt University building was still active at the time of writing, even though the requirements had been lifted since February 2022 and the sign had long since been removed (QR scanned from image; Figure 3A). At the time of writing (February 2023), the Service NSW “COVID safe check in” no longer functioned.

5. Discussion

The following discussion will address the cultural significance of QR-code-initiated contact tracing registers, and the state of constraints of the audiovisual archiving of the COVID-19 check-in applications, with a further discussion on the materiality of digital heritage. The discussion concludes with considerations of management processes of virtual heritage, and how the materiality of virtual heritage can be managed.

5.1. The Cultural Significance of QR-Code-Initiated Contact Tracing Registers in Australia

As noted by numerous authors, events of war, natural disasters and terrorist attacks create social conditions that entice or force populations to accept real or perceived infringements on personal liberties that would be uncountenanceable under ordinary circumstances [82,83,84]. The COVID-19 pandemic is no different in this regard [85,86,87,88,89]. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous governments, driven by the perceived primacy of public health concerns, favoured, and implemented, centralized contact tracing registers, mandating participation without formal, volunteered consent [88,90,91]. Members of the public were not only concerned about governmental overreach, but also feared that the applications could be used to gather personal data beyond the declared remit of contact tracing. Indeed, a paper by Sharma et al. examining the privacy protections embedded in a range of COVID-19 tracing apps that were publicly accessible via Google PlayStore in 2020 found that 60% of the applications required users to grant access permissions well beyond what was (incl. access to contacts) essential for their purposes [92].

In the Australian case, the cultural significance of these QR-code-initiated apps, irrespective of their small nature and comparatively short implementation span, rests in the fact that Australian citizens, by and large, were ready to surrender their privacy and allowed themselves and their movements to be registered and potentially traced, all in the name of the public good and public health. The groundwork for this had been laid, to some extent, by internal state border closures [50], as well as the ring-fencing of communities within states.

By the time the QR check-in option of the Service NSW app was formally discontinued on 7 June 2022 [72], 1.39 billion check-ins had been registered [93] from a population of 6.6 million residents aged 14 years and older [94]. This widespread acquiescence needs to be seen in the context of the almost visceral response to the, ultimately failed, introduction of the Australia card three decades ago. At the time (1985), the Hawke Labor government proposed to introduce a national identification card for Australian citizens and foreigners with residency status to better track possible tax avoidance, and health and welfare fraud. The scheme was abandoned in 1987 in the face of widespread opposition and deep-seated fears of governmental overreach and invasion of privacy [95,96,97]. Attempts to introduce a national identification card in the wake of terrorist bombings in 2004 and 2005 [98] also failed due to privacy concerns [99].

5.2. Audiovisual Archiving of COVID-19 Check-In Applications

The photographic dataset of public notices with QR codes documented as part of the physical manifestation of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in twenty links to venue-based electronic contact registers, six of which were no longer active in January 2022, with an additional link inactive since then.

The COVID-19 check-in applications and webforms were created by commercial providers of guest and restaurant management software as an extension of their offerings (e.g., Brisktable), by large web development and application design houses with large marketing capabilities (e.g., Corplite Technologies [100,101]), and by small-scale web designers creating niche applications (e.g., Nook app). In addition, some venues designed their own forms, either through custom programming using in-house capabilities (e.g., Charles Sturt University), or ad hoc development using GoogleDocs (e.g., Catholic Diocese Wagga Wagga), possibly drawing on free online instructions [102].

The future of these applications, and this expression of digital heritage, are uncertain. Critical in this regard will be the timeframe that is envisaged. It can be posited that both smaller and larger firms will retain the code in the short-to-medium term for future reference and adaptation when designing similar registers. It can be posited, however, that venues that engaged in ad hoc development using GoogleDocs will discard these capabilities once their websites are redesigned or restructured, thereby losing the code. Likewise, the resilience of web developers varies, based on long-term financial viability (for larger entities) and personal interest (for smaller entities). Depending on the interest of the former and new owners, some of the code may be retained. In view of the intellectual property in these applications, it is unlikely that the server-side code will be freely shared for archiving by outsiders. This indeed was confirmed by inquiries made as part of this paper.

While the underlying programming code of these applications may be retained by these companies in the immediate future, it can be expected that changes to programming languages may make some of the code (and its retention for future use) obsolete. Furthermore, the costs of the audiovisual archiving and data migration of obsolete applications is a cost that companies are unlikely to bear. In the longer term, even if such data migration of obsolete applications were to occur, the future of such digital company archives will be in doubt if the paucity of historic company archives of the second half of the twentieth century in public hands is any guide.

Consequently, the future of these applications as records of the societal reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic appears bleak. Before we consider potential approaches for managing the heritage implication of these COVID-19 registers, it is incumbent to briefly discuss their nature, as they are, sensu stricto, neither tangible nor intangible heritage.

5.3. The Materiality of Digital Heritage

The materiality of any artefact, which, sensu stricto, is an object created and shaped through direct and intentional human intervention, is comprised of ontic and ontological properties. Artefacts possess ontic properties, which are based on tangible, measurable and otherwise observable and describable attributes: shape, size, colour, texture, weight and raw material(s) [103]. Artefacts also possess ontological properties, those intangible properties that relate to an artefact’s existence and function in personal or communal lives, and the social relationships they establish, reaffirm or symbolize [103]. Inherent in all discussion of the ontological properties of artefacts is that they have material, social or spiritual value to the owner.

There is a growing body of literature that considers ‘digital materiality,’ not only from the angle of tangible objects (computers, peripherals and storage media) [104,105], but that also approaches the topic from the premise that data as intangible facilitators of actions can create definable entities, such as the results of a web search or a text generated by artificial intelligence, that possess numerous ontological dimensions, and that therefore warrant the attribution of materiality [106,107]. The conceptualization and application of ‘digital materiality’ is becoming increasingly multifaceted and opaque.

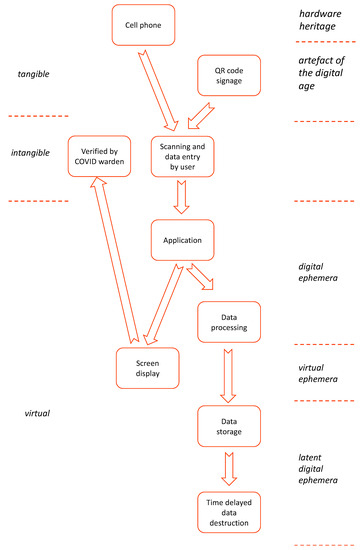

There is need for a level of classificatory rigor to disentangle this space. At the very least, we should differentiate between the following:

- Hardware heritage (i.e., computers, keyboards, storage media, printers);

- Digital artefacts (i.e., items of material culture generated by computers, such as a paper printouts or 3D products);

- Virtual artefacts (i.e., virtual, computer-generated content that is visually or auditorily perceivable by humans via computer screens or speakers);

- Latent digital signatures (i.e., volatile data written on ferromagnetic or optical media surfaces);

- Digital ephemera (i.e., programs, interactions and content performed and generated by computers without a tangible output).

While digital ephemera, latent digital ephemera and virtual artefacts possess numerous ontological properties of materiality that can be described and thus documented, the ontic dimension, and one can argue condition, of ‘materiality,’ however, is not met. Consequently, it is apposite to conceptualize this reality of heritage as a third domain to accompany the established domains of tangible heritage and intangible heritage: virtual heritage (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Process flow of the digital check-in systems in relation to the three heritage domains and the various manifestations of digital heritage.

5.4. Towards Management Processes of Virtual Heritage

From a cultural heritage management perspective, it is imperative to develop processes and procedures that allow for the documentation and preservation of virtual heritage. As virtual heritage shares a lack of ontic properties with intangible heritage, it is apposite to use the approaches to the management of this heritage as a model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Framework for the management of intangible and virtual heritage.

In an ideal world, the cultural expressions of intangible heritage are maintained through their ongoing relevance to a community and its continued practice [108,109,110]. Given that community values are intergenerationally mutable qualities [111], which may lead to the discontinuation of a practice, cultural expressions of intangible heritage need to be observed and documented, with the collection of the associated material culture. The same applies to virtual heritage, with the expectation that intragenerational technological change will make the continuation of a practice inevitably impossible. While the use of emulators has been showcased, for example, in the realm of old video/arcade games [112,113], they cannot replicate the look and feel of the now-obsolete machines, cathode-ray tube monitors and peripherals (such as trackballs and joysticks) that were instrumental elements of the user experience.

The recording of an intangible heritage practice should include an ethnographic observation and description of the practice, be it a dance or the exercise of a traditional skill. Likewise, an ethnographic observation and description of the computing practice situates computer usage in the sociocultural environment in which it is embedded. The current generation, all techno-natives [114] of an age of personal desktop computing, for example, has no understanding that the university processing and statistical analysis of experimental data in the early 1980s required that a code be written, compiled and tested, and that a computer operator had to be asked to manually mount the relevant tape drives for the program to access the relevant data.

The recording of an intangible heritage practice entails the rationale, process and sequence of the practice, as well as the audiovisual recording of events (sound, visions), both through formal and informal channels [115], and the documentation of the objects used (instruments, dress, paraphernalia). Ideally, any documentation should also include a recording of the experiential effect of the practice on the actors/participants, as well as the audience. Similarly, the recording of the virtual heritage practice not only entails the rationale, process and sequence of the practice, but then also includes content and output (via printouts), and the computer code of programs and applications. Similar to the approach to intangible heritage practice, it is advantageous to compile an audiovisual recording of the user interaction, and to record the experiential effect of the practice on the users of hardware and software, as well as the experiential effect on clients.

Finally, the material culture associated with intangible and virtual heritage can be collected and curated. In the field of virtual heritage, we need to consider not only the collection of hardware heritage and digital artefacts, but also the collection and archiving of digital ephemera.

There are some limitations, however. As noted, the programs, interactions and content performed and generated by computers without tangible output are digital ephemera. Even if the code of an application is printed out, it needs to be realized that this, in and of itself, is insufficient. All applications used for the COVID-19 check-in registers rely on helper applications or enabling language. For example, the majority of the applications rely on user- or server-side executed code written in the JavaScript programming language, which requires the presence of a JavaScript engine (a software component) on the host machine to execute the script. Consequently, the mere documentation of the code as reflected on the webpage (to which the QR code points) does not ensure future executability. Moreover, in the case of server-side executed code, the critical JavaScript code also resides on the host machine and the HTML code of the webpage merely initiates this script (Table 4).

Table 4.

Individual venue-based electronic contact registers documented for Albury (NSW) and other locations. For individual URLs, see Table A1.

6. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020–2023 represents an unprecedented socioeconomic and sociocultural disruptor on a global scale and with a magnitude (albeit not the number of deaths) exceeding the impact of the influenza pandemic of 1918/19. The pandemic manifested itself in a range of items of material culture, such as face masks, hand sanitizer stations, social distancing indications and temporary structures, as well as numerous online portals and other digital solutions, to handle the information and administrative requirements that were required to manage it from a public health perspective.

Among these digital solutions were online registers to facilitate the contact tracing of COVID-19-positive individuals. Created ad hoc and designed by both small independent and larger web software providers, the various application designs soon saw an enthusiastic uptake by businesses that were keen to do away with cumbersome pen-and-paper records. Scanning a venue-specific QR code with a personal smartphone initiated a data collection web interface. After several months of operation, these individual systems were formally replaced by centralized data collection systems run by the various public health authorities in each of the Australian states. None of these independently designed systems were formally documented as part of a social science collection developed to document and archive community and government responses to the pandemic.

As this paper has shown, while several of these applications are still running (when tested using QR codes found on photographs), there are no processes in place to archive these digital ephemera, and there is little prospect that those that still remain will survive the next company restructure, let alone upgrades to hardware platforms, programming languages and operating systems.

This paper discusses these applications as virtual heritage, which forms part of the broader concept of digital heritage, and it proposes a framework for the management of virtual heritage that draws on parallels with the management of intangible heritage. In addition to recording the rationale, process and sequence of the use of such applications, any documentation should also include the recording of an audiovisual recording of the user interaction and a recording of the experiential effect of the use of these applications, as well as the digital archiving of underlying computer codes and other virtual and digital ephemera.

While some modicum documentation was possible both concurrent with the practice (e.g., photographic recording of QR code signs and screenshots of applications) and retrospectively (e.g., save some publicly accessible codes), this only captured a small amount of what could have been possible. The process discussed and proposed in this paper provides a framework to capture future events in a more holistic and comprehensive fashion.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Jeremy Blaze (Never Before Seen, Melbourne) and Andrew Rigney (Web Office, Division of Information Technology, Charles Sturt University) for the comments on their operations.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of weblinks (all accessed 31 January 2022 and again on 31 October 2022 and 4 February 2023; for statuses, see Table 1).

Table A1.

List of weblinks (all accessed 31 January 2022 and again on 31 October 2022 and 4 February 2023; for statuses, see Table 1).

References

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Beyond Preserving the Past for the Future: Contemporary Relevance and Historic Preservation. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2011, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Feilden, B. Conservation of Historic Buildings; Routledge: Abindon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Conceptualizing a Methodology for Cultural Heritage Futures: Using Futurist Hindsight toMake ‘Known Unknowns’ Knowable. Heritage 2023, 6, 548–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzerini, F. Intangible cultural heritage: The living culture of peoples. Eur. J. Int. Law 2011, 22, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munjeri, D. Tangible and intangible heritage: From difference to convergence. Mus. Int. 2004, 56, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggett, J. Archaeologies of the digital. Antiquity 2021, 95, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashe, C.J.; Johnson, L.R.; Palmer, J.H.; Pugh, E.W. IBM’s Early Computers; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Król, K. Hardware Heritage—Briefcase-Sized Computers. Heritage 2021, 4, 2237–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, B.; Hemmendinger, D. Desktop Publishing, Part 2. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 2019, 41, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grad, B.; Hemmendinger, D. Desktop Publishing, Part 3. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 2020, 42, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, A.B.; Sheard, J.; Avram, C. The Monash Museum of Computing History: Part 1. ACM SIGCSE Bull. 2008, 40, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, K. 12.4 Computermuseum (Hardware Preservation). In Nestor Handbuch: Eine Kleine Enzyklopädie der Digitalen Langzeitarchivierung, 1st ed.; Neuroth, H., Liegmann, H., Oßwald, A., Scheffel, R., Jehn, M., Eds.; Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek: Göttingen, Germany, 2008; pp. 12.24–12.30. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, K. 8.5 Computermuseum (Hardware Preservation). In Nestor Handbuch: Eine Kleine Enzyklopädie der Digitalen Langzeitarchivierung, 2nd ed.; Neuroth, H., Liegmann, H., Oßwald, A., Scheffel, R., Jehn, M., Eds.; Verlag Werner Hülsbusch: Göttingen, Germany, 2009; pp. 8.24–28.31. [Google Scholar]

- Huth, K. 8.5 Computermuseum (Hardware Preservation). In Nestor Handbuch: Eine Kleine Enzyklopädie der Digitalen Langzeitarchivierung, 3rd ed.; Neuroth, H., Oßwald, A., Scheffel, R., Strathmann, S., Huth, K., Eds.; Verlag Werner Hülsbusch: Göttingen, Germany, 2010; pp. 8.24–28.31. [Google Scholar]

- Dooijes, E.H. Old Computers, Now and in the Future; University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, C. Bits and pieces: A mini survey of computer collecting. Ind. Archaeol. Rev. 2003, 25, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, G.; Rosin, R.F. 16. The role of museums in collecting computers. In Forum on the History of Computing. History of Programming languages II; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 785–788. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, P. Retrocomputing, archival research, and digital heritage preservation: A computer museum and iSchool collaboration. Libr. Trends 2011, 59, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer, H. Preserving the Technical Heritage. In Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing, 3rd ed.; Bruderer, H., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 851–858. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, M.S. The history of computing in the history of technology. Ann. Hist. Comput. 1988, 10, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computer History Museum. CHM’s Oral History Collection. Available online: https://www.computerhistory.org/collections/oralhistories/ (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Johnson, L. Creating the software industry-recollections of software company founders of the 1960s. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 2002, 24, 14–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, M.S. What makes the history of software hard. IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 2008, 30, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, K. There is no objective history of video games—Every player’s experience is different. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/games/2022/jul/14/there-is-no-objective-history-of-video-games-every-players-experience-is-different (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Ries, T. “Die geräte klüger als ihre besitzer”: Philologische Durchblicke hinter die Schreibszene des Graphical User Interface. Editio 2010, 24, 149–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, T. The rationale of the born-digital dossier génétique: Digital forensics and the writing process: With examples from the Thomas Kling Archive. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2018, 33, 391–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrave, J.-L. Computer forensics: La critique génétique et l’écriture numérique. Genesis. Manuscr. Rech. Invent. 2011, 33, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasson, A.; Lebrave, J.-L.; Pedrazzi, J. Le «siliscrit» de Jacques Derrida. Exploration d’une archive nativement numérique. Genesis. Manuscr. Rech. Invent. 2019, 49, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschenbaum, M.; Ovenden, R.; Redwine, G.; Donahue, R. Digital Forensics and Born-Digital Content in Cultural Heritage Collections; Council on Library and Information Resources: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jarlbrink, J. How to Approach Hard Drives as Cultural Heritage. In Digital Human Sciences New —New Approaches; Petersson, S., Ed.; Stockholm University Press: Stockholm, Sweden, 2021; pp. 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, N.; Grigar, D. Born digital preservation of e-lit: A live internet traversal of Sarah Smith’s King of Space. International J. Digit. Humanit. 2019, 1, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, P.; Smith, J.; Mann, J. The forensic imagination: Interdisciplinary approaches to tracing creativity in writers’ born-digital archives. Arch. Manuscr. 2019, 47, 374–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, K.; Broussard, M. Challenges of archiving and preserving born-digital news applications. IFLA J. 2017, 43, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussard, M.; Boss, K. Saving Data Journalism: New strategies for archiving interactive, born-digital news. Digit. Journal. 2018, 6, 1206–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennock, M.; Day, M. Managing and preserving digital collections at the British Library. In Managing Digital Cultural Objects: Analysis, Discovery and Retrieval; Foster, A., Rafferty, P., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Diprose, G.; George, M.; Darwall-Smith, R. An alternative method of very long-term conservation of digital images and their historical context for the archive, University College, Oxford. In EVA ’18: Proceedings of the Conference on Electronic Visualisation and the Arts; BCS Learning & Development Ltd.: Swindon, UK; pp. 48–55.

- Schielke, P.J. Old hardware new students: Using old computing machinery in the modern classroom. J. Comput. Sci. Coll. 2014, 29, 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Werf, T.v.d.; Werf, B.v.d. Documentary heritage in the digital age: Born digital, being digital, dying digital. In The UNESCO Memory of the World Programme; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Ries, T.; Palkó, G. Born-digital archives. International Journal of Digital Humanities 2019, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassenroot, E.; Chambers, S.; Di Pretoro, E.; Geeraert, F.; Haesendonck, G.; Michel, A.; Mechant, P. Web archives as a data resource for digital scholars. Int. J. Digit. Humanit. 2019, 1, 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T.; Thomas, G.H. The invention and dissemination of the spacer gif: Implications for the future of access and use of web archives. Int. J. Digit. Humanit. 2019, 1, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, J.A. Comparing born-digital artefacts using bibliographical archeology: A survey of Timothy Leary’s published software (1985–1996). Inf. Res. 2019, 24, paper 818. [Google Scholar]

- Guay-Bélanger, D. Assembling Auras: Towards a Methodology for the Preservation and Study of Video Games as Cultural Heritage Artefacts. Games Cult. 2021, 15554120211020381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Of Great Apes and Robots: Considering the Future(s) of Cultural Heritage. Futures 2007, 39, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Collecting COVID-19 Ephemera: A Photographic Documentation of Examples from Regional Australia; Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Curating the Contemporary: A case for national and local COVID-19 collections. Curator 2022, 65, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) and the Virus that Causes It. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Sayers, E. Facing COVID: Engaging participants during lockdown. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2022, 21, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. No Entry into New South Wales: COVID-19 and the Historic and Contemporary Trajectories of the Effects of Border Closures on an Australian Cross-Border Community. Land 2021, 10, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, R.M.; Abeysuriya, R.G.; Kerr, C.C.; Mistry, D.; Klein, D.J.; Gray, R.T.; Hellard, M.; Scott, N. Role of masks, testing and contact tracing in preventing COVID-19 resurgences: A case study from New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Restrictions on Gathering and Movement) (No. 4) Amendment Order (16 July 2020); New South Wales Government Gazette; 2020; pp. 3634–3637.

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Restrictions on Gathering and Movement) (No. 4) Amendment Order (No 3) (31 July 2020); New South Wales Government Gazette; 2020; pp. 3860–3865.

- Purtill, J. The Proliferation of QR Code Check-Ins is a Dog’s Breakfast. Is There a Better Way? Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2020-11-20/covid-19-coronavirus-why-so-many-qr-code-check-in-systems/12895678 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Wong-See, T. QR Codes Making Life Easier for Cafe Owners and Customers, but What about Privacy? Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-10/how-to-use-qr-codes-at-cafes-in-covid-pandemic/12627300 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Nguyen, K. The QR Code has Turned COVID-19 Check-Ins into a Golden Opportunity for Marketing and Data Companies. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-31/covid-19-check-in-data-using-qr-codes-raises-privacy-concerns/12823432 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Blaze, J. COVID Register, 2022; E-mail to the author 21 Januray 2023.

- Bengio, Y.; Janda, R.; Yu, Y.W.; Ippolito, D.; Jarvie, M.; Pilat, D.; Struck, B.; Krastev, S.; Sharma, A. The need for privacy with public digital contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Digit. Health 2020, 2, e342–e344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E.Y.; Saqib, N.U. Privacy Concerns Can Explain Unwillingness to Download and Use Contact Tracing Apps When COVID-19 Concerns are High. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 106718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, R.A.; Hino, A. COVID-19, digital privacy, and the social limits on data-focused public health responses. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, T. Privacy in a pandemic—the conundrum of COVID-19 check-in solutions. Available online: https://iapp.org/news/a/privacy-in-a-pandemic-the-conundrum-of-covid-19-check-in-solutions/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Paine, H. Woolworths Introduces New QR Code Check-In to Trace Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.news.com.au/lifestyle/real-life/news-life/woolworths-introduces-new-qr-code-checkin-to-trace-coronavirus/news-story/af3e7d40bdf6ac15ab4f8944483d6761 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Restrictions on Gathering and Movement) (No. 5) Amendment Order (No 3) (20 November 2020); New South Wales Government Gazette; 2020; p. n2020-4578.

- Service NSW (One-stop Access to Government Services) Amendment (COVID-19 Information Privacy) Act 2021 No 35. 2021. Available online: https://legislation.nsw.gov.au/view/pdf/asmade/act-2021-35 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Gathering Restrictions) Order (Nº 2) Amendment Order (No 2) 2021; New South Wales Government Gazette; 2021; p. n2021-1491.

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 Gathering Restrictions) Order (No 2) 2021; New South Wales Government Gazette; 2021; pp. 1–25.

- Service NSW. COVID Check-in Cards. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20220306091205/https://apply.service.nsw.gov.au/covid-checkin-card/[via wayback machine]; (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 General) Order (No 2) Amendment (No 7) Order 2022; New South Wales Government Gazette; 2022; p. s2022-2061.d2003.

- ACT Government. Check In CBR App No Longer Mandatory, Upgraded for Use as Health Screening Tool. Available online: https://www.covid19.act.gov.au/news-articles/check-in-cbr-app-no-longer-mandatory,-upgraded-for-use-as-health-screening-tool (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Boyd, S. QR check-ins drop in Albury, Greater Hume, Federation and Wagga. The Border Mail. 30 May 2021. Available online: https://www.bordermail.com.au/story/7275110/qr-code-check-ins-drop-in-albury-but-city-stacks-up-next-to-wagga/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Mannheim, M. Most Canberrans Still Using Defunct Check In CBR App as ACT Government Considers Reboot. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-02-03/canberra-check-in-act-use-still-high/100795246 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- MHMR. Public Health (COVID-19 General) Order (No 2) 2022; New South Wales Government Gazette; 2022; p. s2022-2235.d2002.

- Spennemann, D.H.R. COVID-19 on the ground: Heritage sites of a pandemic. Heritage 2021, 3, 2140–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Facing COVID-19: Quantifying the use of reusable vs disposable facemasks. Hygiene 2021, 1, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Material Culture of the COVID-19 Pandemic. A Descriptive Catalogue of SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Tests Collected for the Albury LibraryMuseum; SAEVS, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Material Culture of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Face Masks Donated to Charity. A Cross-Section of Masks Donated to Charitable Organisations by a Regional Australian Community; SAEVS, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. COVID-19 Ephemera of 2021: A Photographic Documentation of Examples from Regional Australia; SAEVS, Charles Sturt University: Albury, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koščík, M.; Myška, M. Copyright Law Challenges of Preservation of" born-digital" Digital Content as Cultural Heritage. Eur. J. Law Technol. 2019, 10., 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Internet Archive. WayBack Machine. Available online: https://archive.org/web/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Anonymous. Sydney News: QR Codes Mandatory across NSW from Today, Severe Fire Danger for Parts of State. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-11-23/sydney-morning-briefing-qr-codes-compulsory/12908600 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Olle, E. SA COVID Restrictions Eased as QR Code System Launched on mySA GOV App. Available online: https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/sa-covid-restrictions-eased-as-qr-code-system-launched-on-mysa-gov-app-c-1682942 (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Grayling, A.C. Liberty in the Age of Terror: A Defence of Civil Liberties and Enlightenment Values; Bloomsbury Publishing: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Deflem, M.; McDonough, S. The fear of counterterrorism: Surveillance and civil liberties since 9/11. Society 2015, 52, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J.M.; Ulmschneider, G.W. Civil liberties, national security and US courts in times of terrorism. Perspect. Terror. 2019, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kitchin, R. Civil liberties or public health, or civil liberties and public health? Using surveillance technologies to tackle the spread of COVID-19. Space Polity 2020, 24, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, C.M.; MacDonnell, V.; Thomas, B.; Wilson, K. Reconciling civil liberties and public health in the response to COVID-19. Facets J. 2020, 5, 887–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamutata, C. Do civil liberties really matter during pandemics?: Approaches to coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Int. Hum. Rights Law Rev. 2020, 9, 62–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.-Y.; Tsai, C.-h. Democratic values, collective security, and privacy: Taiwan people’s response to COVID-19. Asian J. Public Opin. Res. 2020, 8, 222–245. [Google Scholar]

- Chemerinsky, E.; Goodwint, M. Civil Liberties in a Pandemic: The Lessons of History. Cornell L. Rev. 2020, 106, 815. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, I.G.; Gostin, L.O.; Weitzner, D.J. Digital smartphone tracking for COVID-19: Public health and civil liberties in tension. JAMA 2020, 323, 2371–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzechowski, M.; Schochow, M.; Steger, F. Balancing public health and civil liberties in times of pandemic. J. Public Health Policy 2021, 42, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, T.; Bashir, M. Use of apps in the COVID-19 response and the loss of privacy protection. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1165–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Service NSW. Annual Report 2021–22; Service NSW: Haymarket, NSW, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Census of Population and Housing: Population Data Summary, 2021. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/population-census/latest-release#data-downloads (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Greenleaf, G. The Australia Card: Towards a national surveillance system. Law Soc. J. 1987, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf, G.; Nolan, J. The deceptive history of the Australia Card. Aust. Q. 1986, 58, 407–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. The Australia Card-A Survey of the Privacy Problems Arising from the Proposed Introduction of an Australian Identity Card. JL Inf. Sci. 1991, 2, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, F. Australia Considers Identity Card to Combat Terrorism (Update1). Bloomberg News 26 July 2005. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20150924132957/http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=a0frH90idLMo&refer=top_world_news (accessed on 6 February 2023).

- Greenleaf, G. Australia’s proposed ID card: Still quacking like a duck. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2007, 23, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corplite Technologies. COVID Tracer. Available online: https://corplite.com/products/covidtracer/ (accessed on 3 February 2023).

- Corplite Technologies. COVID Tracer. User Manual. 2021.

- Simplewise Living. COVID-19: Create/DIY QR Code and Google Form for Visitor Attendance 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pTb6sF4WHf0 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Tilley, C. Materiality in materials. Archaeol. Dialogues 2007, 14, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Robertson, J. The materiality of digital media: The hard disk drive, phonograph, magnetic tape and optical media in technical close-up. New Media Soc. 2017, 19, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, S. Understanding media archaeology. Can. J. Commun. 2012, 37, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlikowski, W.J. Sociomaterial practices: Exploring technology at work. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1435–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Digital materiality? How artifacts without matter, matter. First Monday 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.-J.; Chiou, S.-C. The safeguarding of intangible cultural heritage from the perspective of civic participation: The informal education of Chinese embroidery handicrafts. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, F. The Participation in the safeguarding of the intangible cultural heritage. Rev. Dos Sócios Do Mus. Do Povo Galego 2018, 23, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Alivizatou, M. Intangible Cultural Heritage and Participation: Encounters with Safeguarding Practices; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Shifting Baseline Syndrome and Generational Amnesia in Heritage Studies. Heritage 2022, 5, 2007–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, D.; Kim, J.; McKeehan, M.; Rhonemus, A. How to party like it’s 1999: Emulation for everyone. Code4Lib J. 2016.

- Von Suchodoletz, D.; Van der Hoeven, J. Emulation: From digital artefact to remotely rendered environments. Int. J. Digit. Curation 2009, 4, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inayatullah, S. Future Avoiders, Migrants and Natives. J. Future Stud. 2004, 9, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobruno, S. YouTube and the social archiving of intangible heritage. New Media Soc. 2013, 15, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).