Understanding the Social Value of Geelong’s Design and Manufacturing Heritage for Extended Reality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Community Surveys

2.2. Stakeholder Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Community Online Surveys

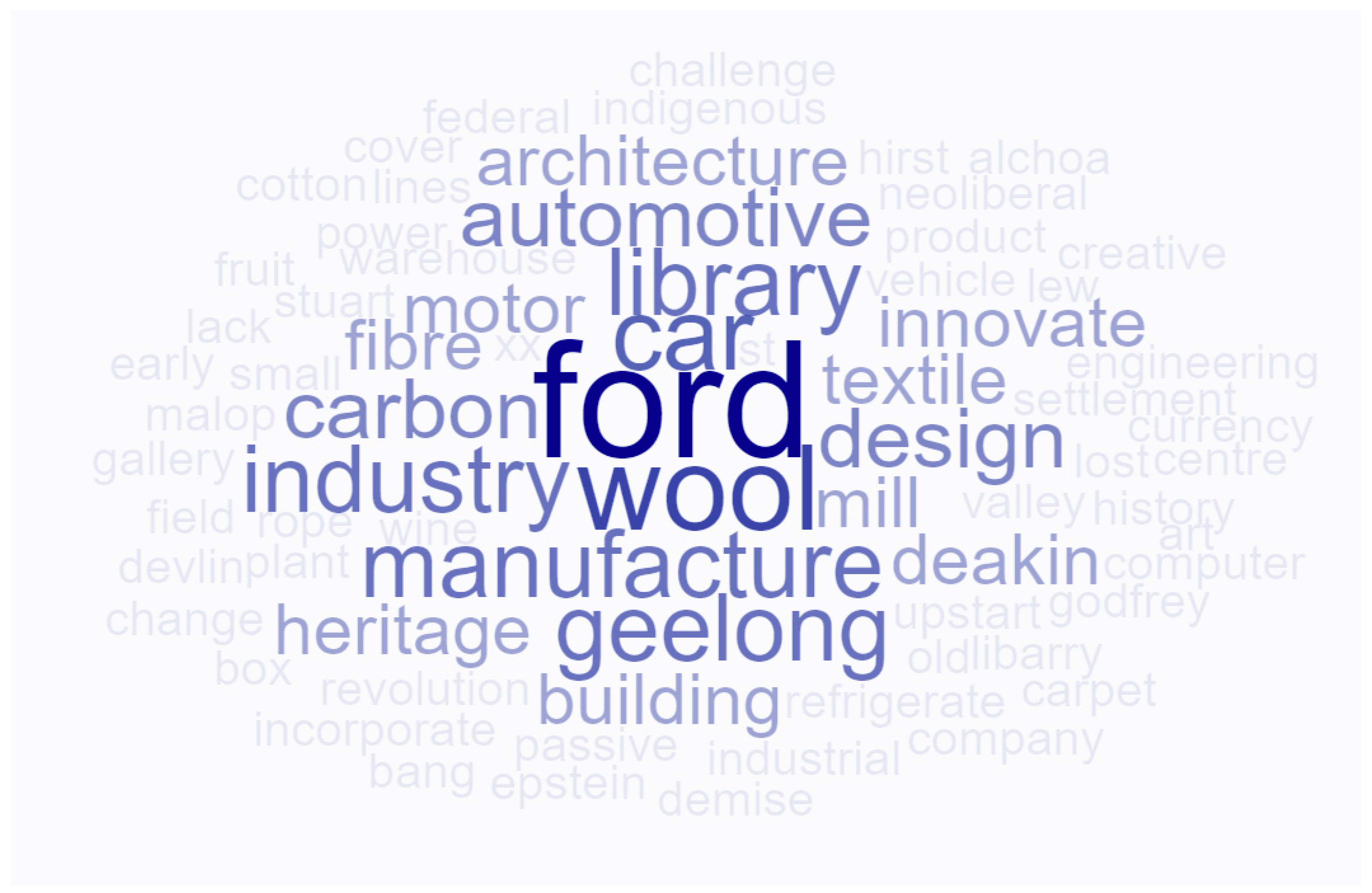

3.1.1. Design and Manufacturing of Geelong and Its Achievements

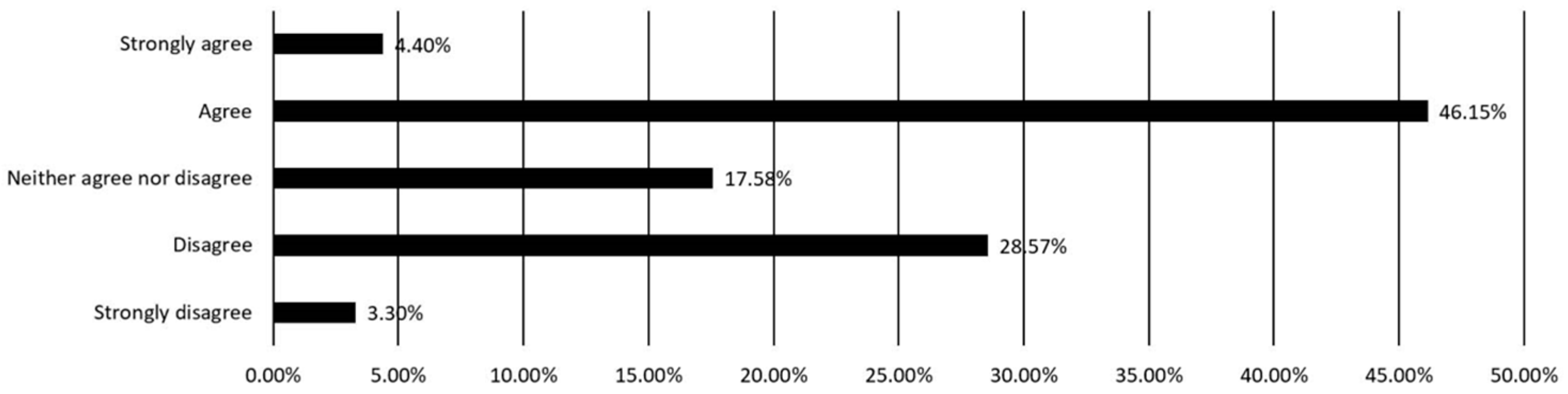

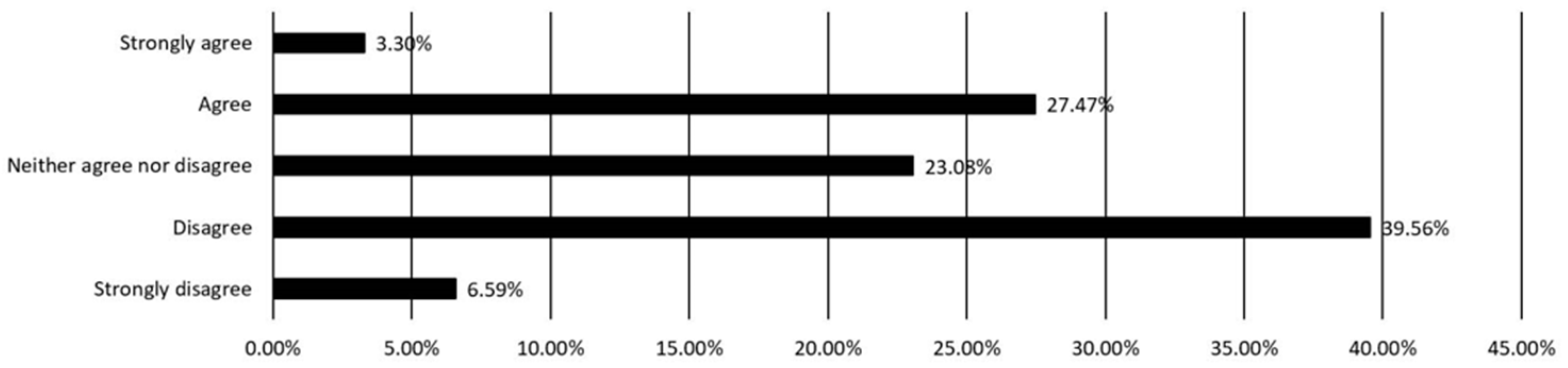

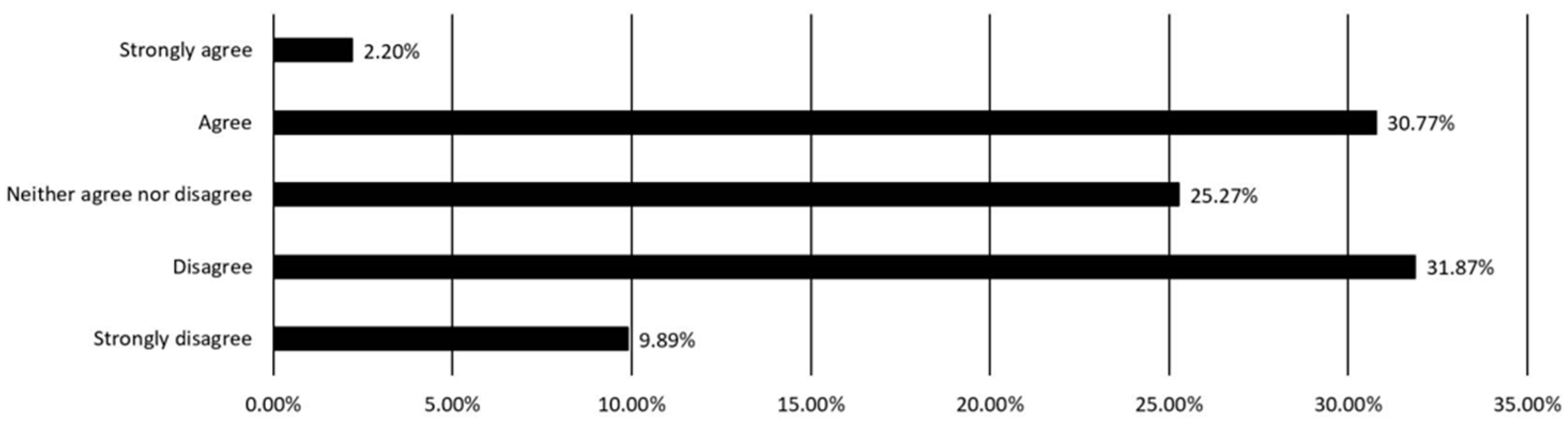

3.1.2. Quantitative Study on the Past and the Future of Geelong’s (Post-)Industrial Identity

3.1.3. Qualitative Results on the Importance of Heritage

“I worked for 22 years in a local Textile company until its demise in the 2008/9 financial crash. Valley Mill commenced in the mid-20’s as a vertical woollen mill producing fine worsted fabrics, especially those for Fletcher Jones and other well-known labels. Anticipating changing times, extensive research and development saw diversification into world class barrier fabrics using Kevlar, Nomex etc for armed services, firefighters; auto fabric for numerous car companies, industrial fabrics e.g. vertical blinds, microfibre, smart fabrics etc.”

“I have worked in three manufacturing companies and my father a fourth. All four no longer exist (a sad indictment I know). But I know stuff from working in each of those industries that helps me in my job today.”

“Worked as a textile designer/in textile business all my life. Geelong was a hub for Australia’s biggest export in those days which is something to be proud of and relatively unknown.”

“Geelong has had a rich and unique history, which design and manufacturing is big part of. At the moment we don’t celebrate our unique identity enough. The manufacturing industry boom in Geelong was about innovative people thinking big, about what could happen in Geelong. We need to tell the story about thinking big and creating new progressive and globally competitive things and not trying to restrict what those things are based on what they have been before. Continuing to create new things and industries.”

“Design and Manufacturing signifies re-invention and the desire to move forward for human endeavour. For me it engenders a solution focused mindset that I find exciting. The new practices or evolution of past practice creates a vibe that we can solve the issues that arise and will evolve to a society that is inclusive of all people, respectful and caring of our environment and other species.”

“It’s the fabric of our community and it where so many of our people were employed and derived a living from, particularly migrants from the 50′s through to the 80′s i.e., Yugoslavs, Italians, Slovenians, Croatians, Macedonians, Serbians, Bosnians, Russians, Ukrainians, Spanish, etc. It tells an important and rich story from our past.”

“I think it’s important to highlight achievements of Geelong in the past, especially with constant new growth in population to the city and surrounding areas. You get an insight of what Geelong was in the past and the history behind it. Geelong is also quite a creative hub, and supportive of local and small businesses. I think there is an opportunity to support the future of design and manufacturing today with recognition of the past.”

“It highlights achievement, ideas creation, local sourcing and supporting of talent, pride in city and competitiveness and collaboration.”

“Geelong’s recent history is of building an economically successful & pleasant new city after the end of our major manufacturing industries. We can provide guidance & inspiration to other regional areas in Australia as some of their industries decline or go through decarbonisation”.

3.1.4. Digital Interpretation of Geelong’s Design and Manufacturing Heritage

3.2. Stakeholder In-Person Interviews

3.2.1. Potential

“the shift from a materials-based economy […] to very specialised manufacturing or quick timeline manufacturing or highly technical manufacturing” demands a different “educational system that produces highly-qualified personnel, the shift in terms of our competitiveness in an international or global market is leaning into that high-level technical expertise as opposed to a bulk manufacturing base”.

3.2.2. Perceptions

3.2.3. Possibilities

“The whole city is our museum. […] I don’t necessarily believe that museums and galleries are the only places that you can go for that. I fundamentally believe if you want to share heritage, object, or a museum object, and it’s around health and maybe maternal health, the hospital is the best place for it to be. Develop an opportunity for the thing to be on display and interpreted and accessible at a hospital.”

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gospodini, A. Portraying, classifying and understanding the emerging landscapes in the post-industrial city. Cities 2006, 23, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caffyn, A.; Lutz, J. Developing the heritage tourism product in multi-ethnic cities. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo Abad, C.J. The post-industrial landscapes of Riotinto and Almadén, Spain: Scenic value, heritage and sustainable tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 2017, 12, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Greater Geelong. Greater Geelong: A Clever and Creative Future 2017. Available online: https://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/common/public/documents/8d4d2ad3b2b24c1-cleverandcreativedecember2017web.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- UNESCO. Creative Cities Network: Geelong. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/creative-cities/geelong#:~:text=About%20the%20Creative%20City%3A,and%20automotive%20and%20machinery%20components (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Gray, F.; Garduño Freeman, C.; Novacevski, M. Milling It over: Geelong’s New Life in Forgotten Places. Hist. Environ. 2017, 29, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Linge, G.J.R. Australian manufacturing in recession: A review of the spatial implications. Environ. Plan. A 1979, 11, 1405–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novacevski, M. The post-industrial landscape of Geelong. In Geelong’s Changing Landscape: Ecology, Development and Conservation; Jones, D.S., Roös, P.B., Eds.; CSIRO Publishing: Clayton, Australia, 2020; pp. 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Dingle, T.; O’Hanlon, S. The inner city transformed: Industrial and post-industrial Melbourne in pictures c1970–2005. In Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities 05 Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 30 November–2 December 2005; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lozanovska, M.; Nakai Kidd, A. ‘Vacant Geelong’ and Its Lingering Industrial Architecture. ARQ Archit. Res.Q. 2020, 24, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.C. Building Pathways to a Brighter Future; Deakin University: Melbourne, Australia, 2012; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Fairbrother, P.; Svensen, S.; Teicher, J. The Withering Away of the Australian State: Privatisation and Its Implications for Labour. Labour Ind. J. Soc. Econ. Relat. Work 1997, 8, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, F.; Novacevski, M. Zombie Urbanism and the City by the Bay: What’s Really Eating Geelong? J. Urban Cult. Stud. 2017, 4, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, S. Beyond aesthetics: Visibility and invisibility in the aftermath of deindustrialization. Int. Labor Work.-Class Hist. 2013, 84, 140–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozina, J.; Bole, D.; Tiran, J. Forgotten values of industrial city still alive: What can the creative city learn from its industrial counterpart? City Cult. Soc. 2021, 25, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crommelin, L. Making Place by Making Things Again?: How Artisanal Makers are Reshaping Place in Post-Industrial Detroit and Newcastle. In The Routledge Handbook of People and Place in the 21st-Century City; Bishop, K., Marshall, N., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Della Lucia, M.; Pashkevich, A. A sustainable afterlife for post-industrial sites: Balancing conservation, regeneration and heritage tourism. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 31, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z. Heritage conservation as a territorialised urban strategy: Conservative reuse of socialist industrial heritage in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2023, 29, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, D. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, UK, 1995; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lesh, J. Social value and the conservation of urban heritage places in Australia. Hist. Environ. 2019, 31, 42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C. What Is Social Value? A Discussion Paper; Australian Heritage Commission: Canberra, Australia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- King, L.; Stark, J.F.; Cooke, P. Experiencing the Digital World: The Cultural Value of Digital Engagement with Heritage. Herit. Soc. 2016, 9, 76–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.C. The ‘co’ in co-production: Museums, community participation and Science and Technology Studies. Sci. Mus. Group J. 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuedahl, D.; Mörtberg, C. Heritage knowledge, social media and the sustainability of the intangible. In Heritage and Social Media. Understanding and Experiencing Heritage in a Participatory Culture; Giaccardi, E., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 107–126. [Google Scholar]

- Crooke, E. The politics of community heritage: Motivations, authority and control. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Gaeta, M.; Monetta, G.; Rarità, L. E-cultural value co-creation. A proposed model for the heritage management. In Proceedings of the 18th Toulon-Verona International Conference, “Excellence in Services”, Palermo, Italy, 31 August–1 September 2015; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, R.; Becvar, K.M.; Boast, R.; Enote, J. Diverse knowledges and contact zones within the digital museum. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2010, 35, 735–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassiliadi, M.; Sylaiou, S.; Papagiannakis, G. Literary myths in mixed reality. Front. Digit. Humanit. 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. Wrestling with the social value of heritage: Problems, dilemmas and opportunities. J. Community Archaeol. Herit. 2017, 4, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, S.; Vassiliadi, M.; Zikas, P.; Geronikolakis, E.; Papagiannakis, G. From readership to usership: Communicating heritage digitally through presence, embodiment and aesthetic experience. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, 676446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, A.; Rodríguez, I.; Ll Arcos, J.; Rodríguez-Aguilar, J.A.; Cebrián, S.; Bogdanovych, A.; Morera, N.; Palomo, A.; Piqué, R. Lessons learned from supplementing archaeological museum exhibitions with virtual reality. Virtual Real. 2020, 24, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, K.; Eklund, E.; Reeves, A.; Scates, B.; Peel, V. Broken Hill: Rethinking the significance of the material culture and intangible heritage of the Australian labour movement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillette, M.B. Theorizing Heritage in the Post-Industrial City. In Heritage, Gentrification and Resistance in the Neoliberal City; Hammami, F., Jewesbury, D., Valli, C., Eds.; Berghan: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Copplestone, T.J. But that’s not accurate: The differing perceptions of accuracy in cultural-heritage videogames between creators, consumers and critics. Rethink. Hist. 2017, 21, 415–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Snis, U.L.; Olsson, A.K.; Bernhard, I. Becoming a smart old town–How to manage stakeholder collaboration and cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 11, 627–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Greater Geelong. The City of Greater Geelong Annual Report 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.geelongaustralia.com.au/common/Public/Documents/8d8661974ed16d2-thecityofgreatergeelongannualreport2019-20.PDF (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Jackson, S. The ‘Stump-Jumpers’: National Identity and the Mythology of Australian Industrial Design in the Period 1930–1975. Des. Issues 2002, 18, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, D. The heritage of mundane places. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 381–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, S.; Buckley, K. Visual research methodologies and the heritage of ‘everyday’ places. In People-Centred Methodologies for Heritage Conservation; Madgin, R., Lesh, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ogrizek, M.; Mortimer, M.; Antlej, K.; Callari, T.C.; Stefan, H.; Horan, B. Evaluating the Impact of Passive Physical Everyday Tools on Interacting with Virtual Reality Museum Objects. Virtual Real. 2023; submitted, under review. [Google Scholar]

| Survey Questions | |

|---|---|

| Q1 | What are the first five things you think about or associate with Geelong’s design and manufacturing? |

| Q2 | Have you heard about the following Geelong’s inventive/innovative design products, services, and technologies? This is a short list of just a few known achievements by a Geelong born and/or trained person and/or they were invented/innovated and/or first applied in Geelong. |

| Q3 | Our list of Geelong’s inventive/innovative design products, services and technologies is NOT COMPLETE. Let us know of any other achievements from this region you are aware of. You are more than welcome to add more details and who to contact for additional information. We are especially interested to learn about achievements by underrepresented groups (e.g., Indigenous and female inventors and designers) on this list. |

| Q4 | How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements? |

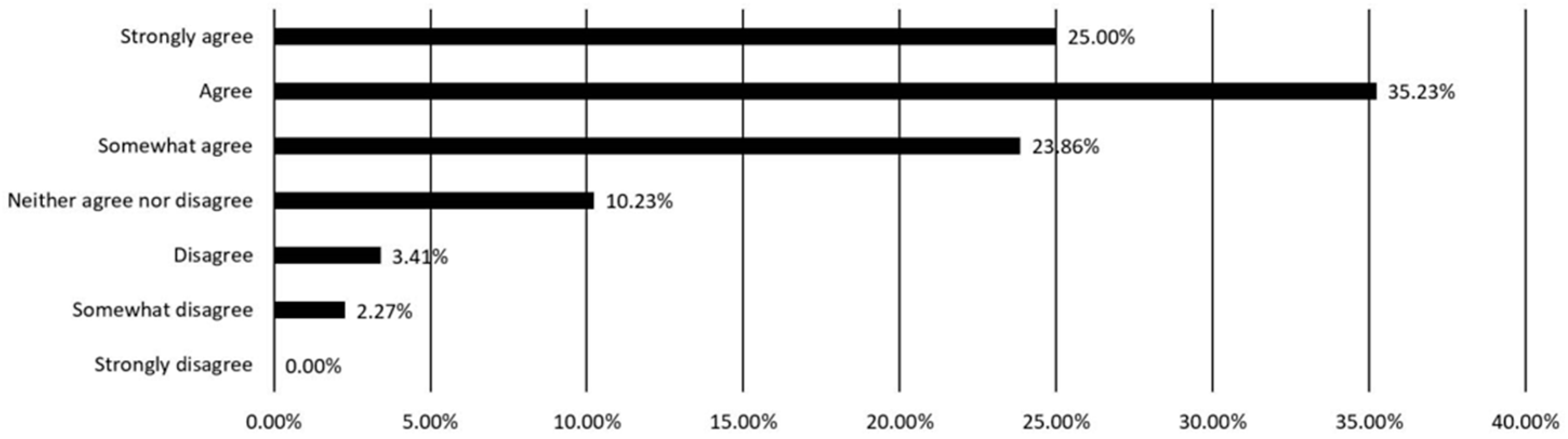

| Q5 | How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements? |

| Q6 | Describe why the design and manufacturing heritage of Geelong is important, or not, to you |

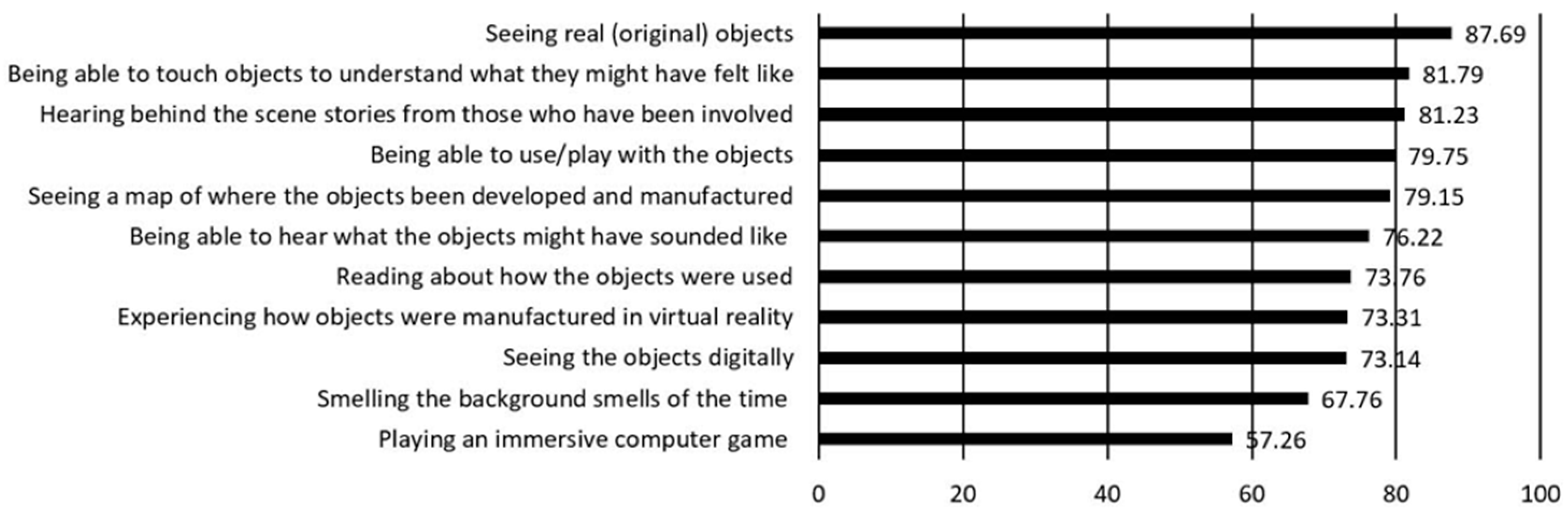

| Q7 | From this list, how much would the following experiences help you connect with our local design and manufacturing heritage? Slide the bar from 0 to 100. |

| Q8 | How much experience do you have with the following extended reality technologies? |

| Q9 | How interested are you in exploring extended reality to learn about Geelong’s inventions and design and manufacturing heritage? |

| Q10 | Tell us your fun ideas to experience an iconic Ford ute (original from 1934 or newer editions) using extended reality. It could be an immersive, touch-controlled and even a game-like experience… |

| Q11 | Describe how the following institutions could contribute to an immersive and interactive exhibition about Geelong’s design and manufacturing: Gallery Library Archive Museum |

| Q12 | Anything else you would like to add? |

| Q13 | What is your connection, if any, with design and manufacturing in Geelong? |

| Q14 | How long have you known about Geelong’s inventions and design and manufacturing heritage? |

| Q15 | What is your age? |

| Q16 | What is your gender? |

| Q17 | What is your higher educational level completed? |

| Interview Questions | |

|---|---|

| Q1 | How would you describe the past and present design, manufacturing, and engineering industry in Geelong? |

| Q2 | How would you describe your past and present involvement with the design, manufacturing, and engineering industry in Geelong (the answers should not be identifiable or de-identifiable)? |

| Q3 | Have there been any changes over time in Geelong? |

| Q4 | How would you describe the community’s perception of manufacturing and engineering in Geelong? |

| Q5 | How do external visitors (e.g., regional, interstate, overseas) see Geelong today? |

| Q6 | The Ford ute, the design of the first decimal currency coins, the rotary clothes hoist, and more recently, carbon wheels and RealSilk artificial fabric have all been developed in Geelong. Can you think of any opportunities to make objects like these more visible, for the benefit of the local community? |

| Q7 | Should this aspect of Geelong’s story be displayed in the local region? Where do you think is a suitable location? |

| Q8 | Do you see any benefits in telling the story of Geelong’s design and manufacturing heritage to the local community and visitors using extended reality experiences such as 3D printing, virtual reality, and augmented reality? |

| Q9 | Do you believe there is a connection between learning about local design and manufacturing heritage and an increase in participation in engineering studies and professional pathways? |

| Q10 | Do you believe learning about local design and manufacturing heritage could encourage girls, women and other underrepresented groups to participate in engineering studies and professions? |

| Q11 | Would you like to share any other ideas or add anything else? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antlej, K.; Cooke, S.; Kelly, M.; Kennedy, R.; Pikó, L.; Horan, B. Understanding the Social Value of Geelong’s Design and Manufacturing Heritage for Extended Reality. Heritage 2023, 6, 3043-3062. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030162

Antlej K, Cooke S, Kelly M, Kennedy R, Pikó L, Horan B. Understanding the Social Value of Geelong’s Design and Manufacturing Heritage for Extended Reality. Heritage. 2023; 6(3):3043-3062. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030162

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntlej, Kaja, Steven Cooke, Meghan Kelly, Russell Kennedy, Lauren Pikó, and Ben Horan. 2023. "Understanding the Social Value of Geelong’s Design and Manufacturing Heritage for Extended Reality" Heritage 6, no. 3: 3043-3062. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030162

APA StyleAntlej, K., Cooke, S., Kelly, M., Kennedy, R., Pikó, L., & Horan, B. (2023). Understanding the Social Value of Geelong’s Design and Manufacturing Heritage for Extended Reality. Heritage, 6(3), 3043-3062. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6030162