Can Overtourism at Heritage Attractions Really Be Sustainably Managed? Lights and Shadows of the Experience at the Site of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Management of Overtourism and Handling Capacities in Heritage Sites

3. Methods and Case Study

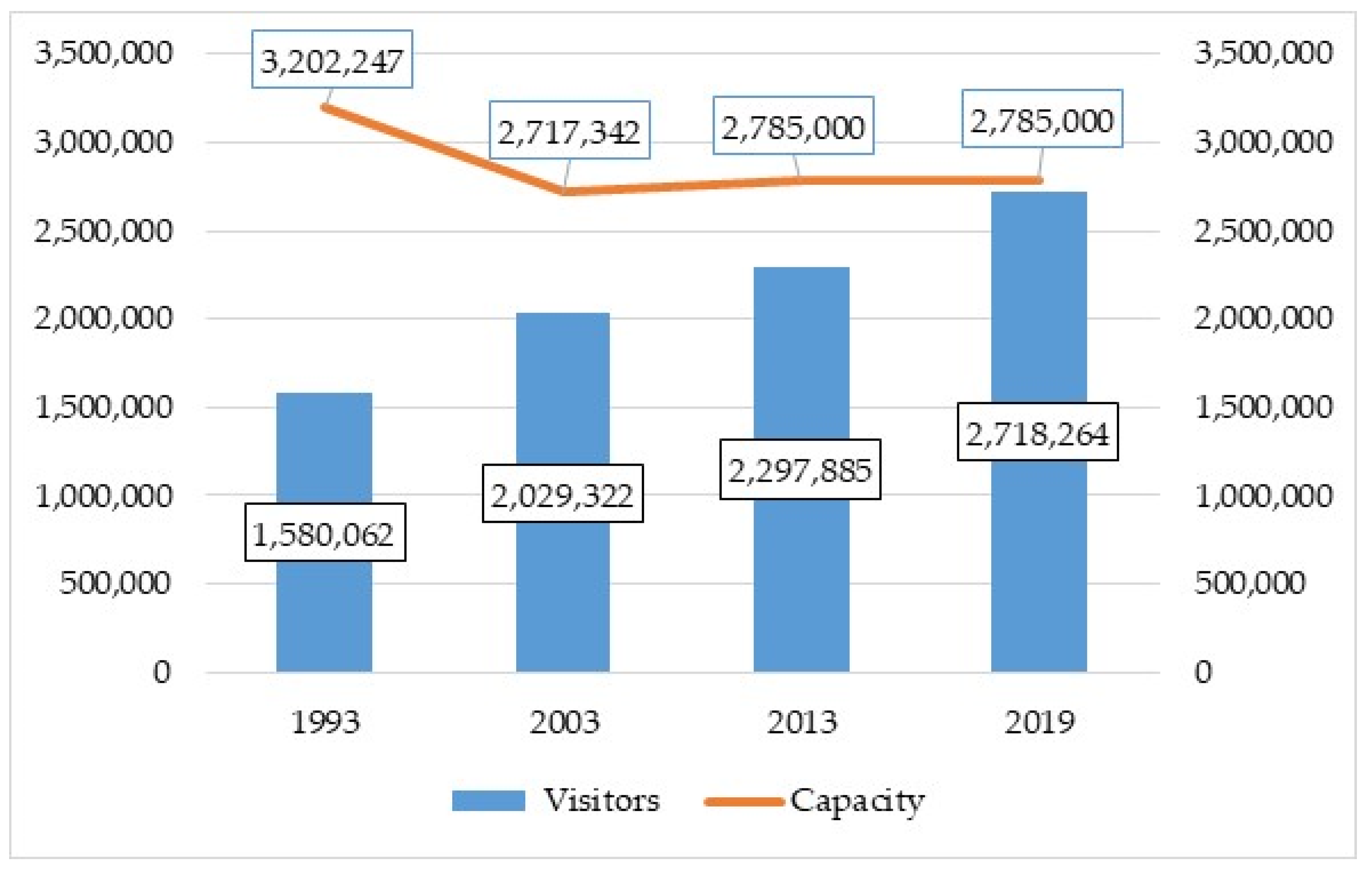

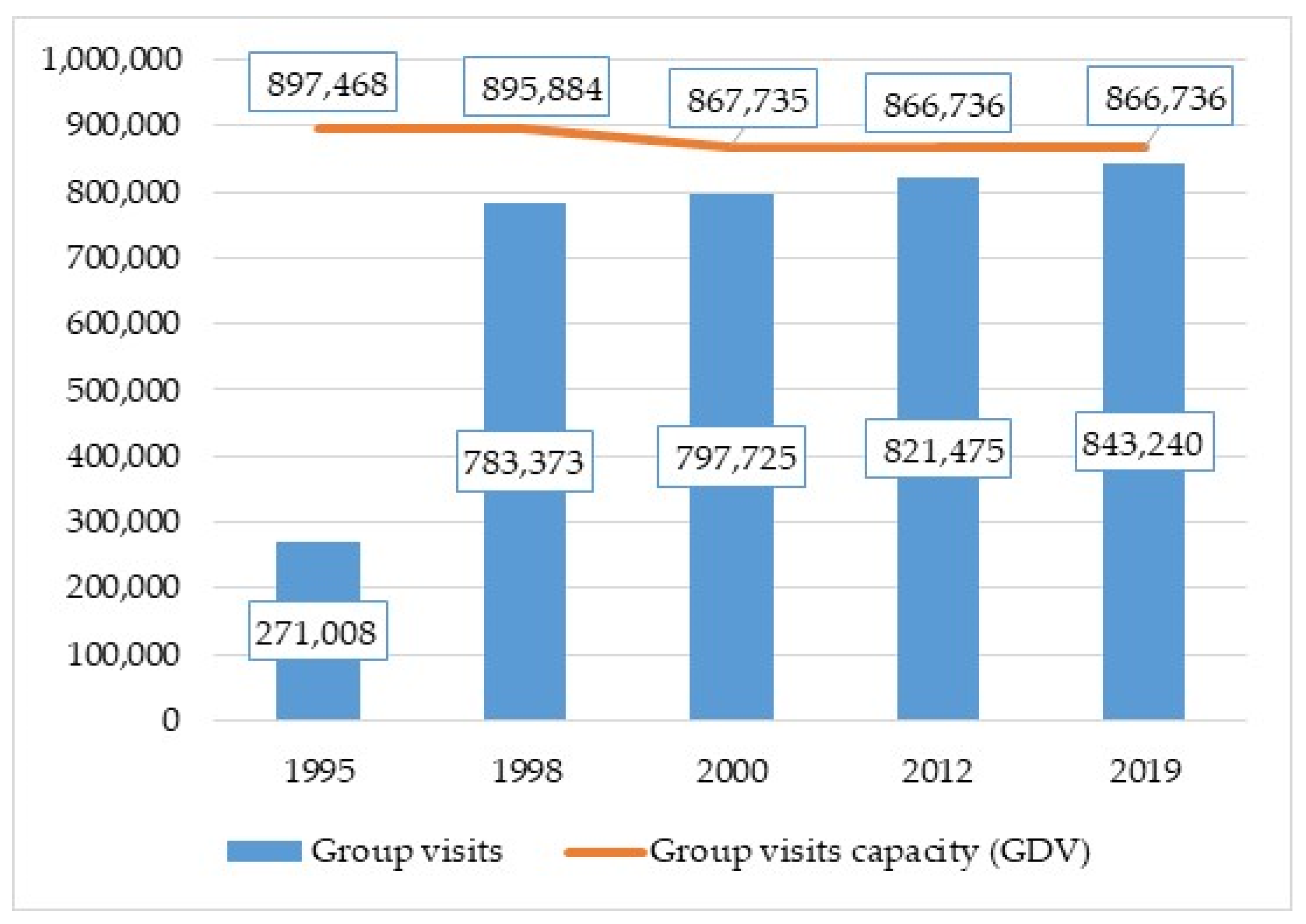

4. Results: Management of Tourist Visits to the Alhambra and Generalife Site

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICOMOS. Cultural Tourism Charter; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1976; Available online: https://www.icomosictc.org/p/1976-icomos-cultural-tourism-charter.html (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- ICOMOS. Cultural Tourism Charter; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1999; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters/INTERNATIONAL_CULTURAL_TOURISM_CHARTER.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- García Hernández, M.; de la Calle Vaquero, M.; Mínguez García, C. Capacidad de carga turística y espacios patrimoniales. Aproximación a la estimación de la capacidad de carga del Conjunto Arqueológico de Carmona (Sevilla, España) [Tourist carring capacity and heritage sites. Archaeological site of Carmona (Seville, Spain)]. Bol. Asoc. Geóg. Esp. 2011, 57, 219–242. Available online: https://bage.age-geografia.es/ojs/index.php/bage/article/view/1382 (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Wall, G. From carrying capacity to overtourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D. “Overtourism” Old Wine in New Bottles? 2017. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/overtourism-old-wine-new-bottles-dianne-dredge (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is “overtourism” a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2235–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adie, B.A.; Falk, M.; Savioli, M. Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Europe. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1737–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Dastgerdi, A.S.; Francini, C.; Liberatore, G. Sustainable cultural heritage planning and management of overtourism in art cities: Lessons from Atlas World Heritage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclaren, F.T. Cultural heritage resources in National Parks in North America—The challenge to maintain historic structures and sites in the face of increasing demand and decreasing budgets. In The Overtourism Debate: NIMBY, Nuisance, Commodification; Oskam, A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heskinga, J.; Isaac, R.; et al. Research for TRAN Committee-Overtourism: Impact and Possible Policy Responses; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panayiotopoulos, A.; Pisano, C. Overtourism dystopias and socialist utopias: Towards an urban armature for Dubrovnik. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M.; Szromek, A.R. Influence of the residents’ perception of overtourism on the selection of innovative anti-overtourism solutions. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Pazos Otón, M.; Piñeiro Antelo, M.d.l.Á. čExiste overtourism en Santiago de Compostela? Contribuciones para un debate ya iniciado. Bol. Asoc. Geógr. Esp. 2019, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuval, F. To Compete or Cooperate? Intermunicipal Management of Overtourism. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sousa, A. La percepción de los problemas del overtourism en Barcelona. Recerca 2021, 26, 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remenyik, B.; Barcza, A.; Csapó, J.; Szabó, B.; Fodor, G.; Dávid, L.D. Overtourism in Budapest: Analysis of spatial process and suggested solutions. Reg. Stat. 2021, 11, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, K.; Türkay, O. Overtourism in Istanbul: An interpretative study of non-governmental organizational views. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2022, 20, 652–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.P.; Torkington, K. Conflicting discursive representations of overtourism in Lisbon in the Portuguese digital press. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 286–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, S.; Preiti, A. Mapping Overtourism and Undertourism in UNESCO World Heritage Sites Pre- and Post-COVID-19: A Methodological Approach Starting from the Case Study of the City of Rome, Italy. In Tourism Recovery from COVID-19: Prospects for Over- and Under-Tourism Regions; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, N.C. Overtourism at heritage and cultural sites. In Overtourism. Causes, Implications and Solutions; Seraphin, T.H., Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Charlet, N.; Dosquet, F. Overtourism—The Case of the Palace of Versailles; Seraphin, T.H., Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzamuto, M.; Picone, M. The Commodification Dilemma: Tourism Pressure and Heritage Conservation in Barcelona. Societies 2022, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Egger, R. Tourist experiences at overcrowded attractions: A text analytics approach. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021; Wörnd, W., Ed.; Springer International: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caust, J.; Vecco, M. Is UNESCO World Heritage recognition a blessing or burden? Evidence from developing Asian countries. J. Cult. Herit. 2017, 27, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, M.; Holuj, D. Museums and coping with overtourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Papp, B.; Postma, A. Management strategies growth in eight European cities. In ‘Overtourism’?—Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Barth, M.; Camp, M.-A.; Fux, S.; Gross, S. Tourism Destinations under Pressure: Challenges and Innovative Solutions; Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts: Lucerne, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56dacbc6d210b821510cf939/t/5906f320f7e0ab75891c6e65/1493627704590/WTFL_study+2017_full+version.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Roland Berger GMBH. Protecting Your City from Overtourism—European City Tourism Study; Roland Berger: Munich, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.rolandberger.com/en/Insights/Publications/’’Overtourism’’-in-Europe’s-cities-Action-required-before-it’s-too-late.html (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Postma, A.; Koens, K.; Papp, B. Overtourism: Carrying capacity revisited. In The Overtourism Debate: NIMBY, Nuisance, Commodification; Oskam, J.A., Ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, J. Managing overtourism through a holistic lens. In Overtourism. Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism; Milano, C., Cheer, J.M., Novelli, M., Eds.; CABI: New Haven, CT, USA, 2019; pp. 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, G. Perspectives on the environment and overtourism. In Overtourism, Issues, Realities and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, C.; Zacher, D.; Pechlaner, H.; Namberger, P.; Schmude, J. Strategies and measures directed towards overtourism: A perspective of European DMOs. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasian, S.; Onn, G.; Arnautovic, D. Overtourism in Dubrovnik in the eyes of local tourism employees: A qualitatitve study. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1775944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchon, F.; Rauscher, M. Cities and tourism, a love and hate story; towards a conceptual framework for urban overtourism management. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 598–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R.W. Conclusion. In Overtourism, Issues, Realities and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S. Overcoming Overtourism. Creating Revived Originals; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Cities Marketing. Managing Tourism Growth in Europe: The ECM Toolbox. 2018. Available online: https://www.europeancitiesmarketing.com/city-marketing/managing-tourism-growth-in-europe-the-ecm-toolbox-cover/ (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Jamieson, W.; Jamieson, M. Managing overtourism at the municipal/destination level. In Overtourism, Issues, Realities and Solutions; Dodds, R., Butler, R.W., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A. Understanding and Managing Visitor Pressure in Urban Tourism. A Study to into the Nature of and Methods Used to Manage Visitor Pressure in Six Major European Cities; CELTH-Breda University of Applied Sciences: Breda, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://www.celth.nl/sites/default/files/2018-09/Voorkomen%20van%20bezoekersdruk%20in%20Europese%20steden.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Mckinsey & Company-World Travel & Tourism Council. Coping with Success: Managing Overcrowding Tourism Destinations. 2017. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/travel-logistics-and-infrastructure/our-insights/coping-with-success-managing-overcrowding-in-tourism-destinations (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Milano, C. Overtourism, malestar social y turismofobia. Un debate controvertido. PASOS Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2018, 18, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verissimo, M.; Moraes, M.; Breda, Z.; Guizi, A.; Costa, C. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A systematic literature review. Tourism 2020, 68, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; García-Hernández, M.; Mendoza de Miguel, S. Urban planning regulations for tourism in the context of overtourism. Applications in historic centres. Sustainability 2021, 13, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Sobolevsky, S.; Ratti, C.; Girardin, F.; Carrascal, J.P.; Blat, J.; Sinatra, R. An analysis of visitors’ behaviour in The Louvre Museum: A study using Bluetooth data. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2014, 41, 1113–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mygind, L.; Bentsen, P. Reviewing Automated Sensor-Based Visitor Tracking Studies: Beyond Traditional Observational Methods? Visit. Stud. 2017, 20, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Briviba, A. Revived Originals—A proposal to deal with cultural overtourism. Tour. Econ. 2020, 27, 1221–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla Uceda, M. Turismo y patrimonio arquitectónico. Accesibilidad y regulación de flujos de visitantes en la Alhambra. Cuad. Alhambra 2001, 37, 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro, V. La Alhambra. El Lugar Y El Visitante [Alhambra. Place and Visitor]; Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, Tinta Blanca Editor and Editorial Almuzara: Granada, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Villafranca Jiménez, M.M.; Gutiérez-Carrillo, M.L. The Alhambra master plan (2007–2020) as a strategic model of preventive conservation of cultural heritage. Vitruvio. Int. J. Archit. Technol. Sustain. 2019, 4, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enseñat-Soberanis, F.; Frausto-Martínez, O.; Gándara-Vázquez, M.A. Visitor flow management process for touristified archaeological sites. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troitiño Vinuesa, M.A. Estudio Previo Para La Revisión Del Plan Especial De La Alhambra Y Alijares. Documento De Síntesis Y Diagnóstico [Preliminary Study for the Revision of the Special Plan of the Alhambra and Alijares. Synthesis and Diagnosis Document]; Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife: Granada, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- García Hernández, M. Turismo Y Conjuntos Monumentales: Capacidad De Acogida Turística y Gestión De Flujos De Visitantes [Tourism and Monumental Sites: Carring Capacity and Management of Visitor Flows]; Tirant lo Blanch: Valencia, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- García Hernández, M.; de la Calle Vaquero, M.; Ruiz Lanuza, A. Capacidad de carga y gestión turístico-cultural. Aplicaciones en la Alhambra de Granada (España) [Carring capacity and tourist-cultural management. Applications in the Alhambra-Granada (Spain)]. In Innovación Turística Para El Desarrollo; Gómez Hinojosa, C., Palafox Muñoz, A., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas—AMIT: Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Mexico, 2014; pp. 336–356. [Google Scholar]

- Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife. Plan De Innovación Para La Visita. [Innovation Plan for the Tourist Visit]; Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife: Granada, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, T.; Artioli, F.; Colomb, C. Explaining the diversity of policy responses to platform-mediated short-term rentals in European cities: A comparison of Barcelona, Paris and Milan. Environ. Plan. 2019, 53, 1689–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwland, S.; van Melik, R. Regulating Airbnb: How cities deal with perceived negative externalities of short-term rentals. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 23, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, D. A tale of two cities: The regulatory battle to incorporate short-term residential rentals into modern law. Am. Univ. Bus. Law Rev. 2015, 4, 287–321. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3156798 (accessed on 28 August 2023).

- Bei, G.; Celata, F. Challenges and effects of short-term rentals regulation A counterfactual assessment of European cities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 101, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, D.; Seraphin, H. COVID-19 crisis as an unexpected opportunity to adopt radical changes to tackle overtourism. Anatolia 2021, 32, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, P.; Chowdhary, N. Has COVID-19 brought a temporary halt to overtourism? Turyzm Tour. 2021, 31, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Koens, K. The paradox of tourism extremes. Excesses and restraints in times of COVID-19. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. The missing link between overtourism and post-pandemic tourism. Framing Twitter debate on the Italian tourism crisis. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2021, 15, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żemła, M.; Szromek, A.R. From overtourism to no-tourism—Costs and benefits of extreme volume of tourism traffic as perceived by inhabitants of two Polish destinations. J. Int. Stud. 2023, 16, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Capacity Management Strategies | |

|---|---|---|

| Limitation | Extension | |

| Bouchon and Rauscher (2019) [35] | Regulatory (containment) | |

| De Luca et al. (2020) [8] | Regulation | |

| Dodds and Butler (2019) [36] | Limiting numbers, impositions of controls | Facility provision |

| Frey (2021) [37] | Temporal and local administrative restrictions | |

| Eckert et al. (2019) [33] | Restrictions | |

| EUROPEAN CITIES MARKETING (2018) [38] | On-the-ground visitor management/taxes, caps and limitations | On-the-ground visitor management |

| Jamieson and Jamieson (2019) [39] | Physical design and constraints/restrictions/controls | |

| Koens and Postma (2016) [40] | Regulation | Improve city infrastructure and facilities |

| Koens et al. (2018) [30] | Review and adapt regulation | Improve city infrastructure and facilities |

| MCKINSEY & COMPANY—WORLD TRAVEL & TOURISM COUNCIL (2017) [41] | Regulate accommodation supply/limit access and activities | Improve capacity and efficiency of infrastructure, facilities and services |

| Milano (2018) [42] | Decongestion | |

| Murzyn-Kupisz and Holuj (2020) [26] | Monitor and limit informal tourism services and tourism-sharing economy/limit expansion of existing tourism facilities/limits and restrictions on access to particular sites or on particular days | |

| Peeters et al. (2018) [10] | Laws and law enforcement directed at tourists; prevent uncontrollable development | Increasing capacities of the destination to deal with higher numbers of people |

| ROLAND BERGER GMBH (2018) [29] | Regulation of capacities/active management of the sharing economy/limitation of access | |

| Verissimo et al. (2020) [43] | Limit the numbers of visitors/regulate short-term accommodation | Improve public and supporting services/make current destinations more capable of accommodating the growing number of visitors |

| Weber et al. (2017) [28] | Policies and regulations | Infrastructure facilities |

| Plans | Urban plan:

|

Strategic plans:

| |

| Laws | Statutes of the Trust:

|

Public visits and marketing regulations for the site: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/patronato/normativa/normativa-de-visita-publica (accessed on 28 August 2023) and https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/boja.html (accessed on 28 August 2023):

| |

| Management reports | Annual management reports: PATRONATO DE LA ALHAMBRA Y GENERALIFE (de 2007 a 2019). Memoria Anual. Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/patronato/portal-de-transparencia/memorias-anuales (accesed on 28 August 2023). |

| Studies of Visitors | Studies of the Alhambra Sustainability Laboratory. (1999–2016). Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/patronato/portal-de-transparencia/estudios-visitantesdata (accesed on 28 August 2023). |

| Archival documentation | Archival documents from the office of the Secretariat General for the Alhambra until 2014 (reports, studies and resolutions of the management bodies of the Board of the Alhambra). |

| Type of Group | No. of Tickets Available | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Long-term advance sales entry | 129,695 | 15% |

| Cruises | 43,232 | 5% |

| Medium-term advance sales | 43,232 | 5% |

| Short-term advance sales | 129,695 | 45% |

| Asian agencies | 116,725 | 13% |

| Agencies offering day visits from the coast | 155,633 | 18% |

| Local agencies | 116,725 | 13% |

| Other agents | 259,389 | 30% |

| Total Group Capacity | 864,630 | 100% |

| 2000–2008 | 2008–2016 | 2016–2019 | 2020 and After | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quotas | Quotas | Sub-Quotas | Quotas | Quotas | |

| 35% individual visits | 39% individual visits | 39% individual visits | 82% general channel | 70% direct sale, 12% institutional agreements | |

| 30% cultural visits | 22% cultural visits | 22% cultural visits | 18% institutional channel | ||

| 35% group visits | 39% group visits | Long-term advance sales CruisesMedium-term advance sales Short-term advance sales Other | 39% group visitors (extendible to 49%) | Out of the quotas: groups from universities, government and other institutions | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Hernández, M.; de la Calle-Vaquero, M.; Chamorro-Martínez, V. Can Overtourism at Heritage Attractions Really Be Sustainably Managed? Lights and Shadows of the Experience at the Site of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain). Heritage 2023, 6, 6494-6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6100339

García-Hernández M, de la Calle-Vaquero M, Chamorro-Martínez V. Can Overtourism at Heritage Attractions Really Be Sustainably Managed? Lights and Shadows of the Experience at the Site of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain). Heritage. 2023; 6(10):6494-6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6100339

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Hernández, María, Manuel de la Calle-Vaquero, and Victoria Chamorro-Martínez. 2023. "Can Overtourism at Heritage Attractions Really Be Sustainably Managed? Lights and Shadows of the Experience at the Site of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain)" Heritage 6, no. 10: 6494-6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6100339

APA StyleGarcía-Hernández, M., de la Calle-Vaquero, M., & Chamorro-Martínez, V. (2023). Can Overtourism at Heritage Attractions Really Be Sustainably Managed? Lights and Shadows of the Experience at the Site of the Alhambra and Generalife (Spain). Heritage, 6(10), 6494-6509. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6100339