Abstract

The craft of painting icons on glass developed in the 17th century in Transylvania (Romania) following the spread of the news about the wooden icon of the weeping Mother of God in the church of Nicula. This news turned Nicula into a pilgrimage centre, and requests for reproductions of the icon led to the locals becoming glass painters. Because of the surplus of icons, some of the Nicula painters set up new icon-painting centres along the road to Brașov (to the south) and the other main trade routes of Transylvania. In order to highlight the potential for sustainable development associated with this craft and to stimulate the painting of icons in the traditional way, we conducted documentary research on the subject of icons on glass. This research revealed the local peculiarities of the icon painters’ workshops and their importance to the identity of the Romanian peasants in Transylvania. We also conducted a participatory observation carried out in Brasov, which revealed that the iconography courses in popular schools of arts and crafts were both a viable way of managing the relationship with the iconographic tradition and a means to capitalize on religious painting on glass as a cultural heritage resource. The research highlighted the way in which, to preserve the traditional dimension of the craft, it is useful to encourage students to use anonymous glass icons as models and to have limited involvement in model restoration.

1. Introduction

1.1. Some Considerations on the History of European Interest in Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage has been a subject of interest in European politics since the founding treaties of the European Union [1]. The concept of “cultural heritage”, which originated in France in the 19th century, was developed in the 1970s and then promoted at national, sub-national and supranational level [2]. Official European discourses place European identity on two pillars: common political and legal values on the one hand, and common culture on the other [3]. The Maastricht Treaty [4] promotes the preservation of culture and its unifying potential in shaping the European identity. The Council Conclusion of 17 June 1994, on the drawing up of a Community Action Plan in the field of cultural heritage, is the first specific document on cultural heritage. The document addresses heritage primarily from the point of view of conservation. However, it also supports its relation to tourism, territorial development, research, media and new technologies. The decades that followed modelled this interpretation of cultural heritage, veering from an interest in conservation and the creation of shared cultural identity to one of socio-economic development supported by heritage as a strategic asset of the EU [5]. In 2014, several documents were issued and marked a turning point in European cultural heritage policies. In fact, they signalled the orientation of European cultural policies towards the sustainable dimension of culture and cultural management [6]. The European Commission’s operational definition of Europe’s cultural heritage is as “a rich and diverse mosaic of cultural and creative expressions, an inheritance from previous generations of Europeans and a legacy for those to come. It includes natural, built and archaeological sites, museums, monuments, artworks, historic cities, literary, musical and audio-visual works, and the knowledge, practices and traditions of European citizens” [7].

Furthermore, the Council of Europe is the international organization that first used the concept of “cultural heritage” as a central piece of its 1954 Cultural Convention, after the Second World War. On that occasion, the tangible, intangible and political dimensions of cultural heritage were also defined. Tangible heritage comprises artefacts and monuments; intangible heritage includes history, language and traditions; political heritage consists of political values and principles. The Council of Europe’s Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (Faro Convention, 2005) [8] promotes the idea of participation and the role of cultural heritage in supporting sustainable development, cultural diversity and contemporary creativity. According to the Faro Convention, in addition to the protected heritage officially that is recognized by national authorities, cultural resources acknowledged by people and local authorities as such are also part of this heritage [9]. In this context, cultural heritage is defined as “a group of resources inherited from the past which people identify… as a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge and traditions. It includes all aspects of the environment resulting from the interaction between people and places through time” [8] (p. 2).

The interest of the various European institutions in cultural heritage has been in line with UNESCO’s interest. The 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention placed the concept in a global framework [10], by acknowledging the axiological potential of cultural representations. The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, ratified in 2003 at the UNESCO General Conference, defined the phrase of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) as “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith—that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage” [11] (p. 5). The Convention outlined five main domains of ICH: “(a) oral traditions and expressions, including language as a vehicle of the intangible cultural heritage; (b) performing arts; (c) social practices, rituals and festive events; (d) knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe; (e) traditional craftsmanship” [11] (p. 5). The list of domains was completed in 2012, when the United Nations World Tourism Organization explicitly added music to performing acts and established a separate ICH domain, namely gastronomy and culinary practices [12] (p. 4).

1.2. The Sustainable Potential of Cultural Heritage

Cultural heritage is dynamic, it evolves in interaction with the social, economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable development [13]. Cultural heritage preserves information about the transformations produced at political, artistic, scientific, spiritual, philosophical or economic levels, transformations that are involved in the formation and management of European identity [9]. It is an expression of human creativity, an identity resource and a source of cohesion for communities [13]. Cultural heritage facilitates intercultural dialogue, diversity and the sense of belonging given by the community of values, being at the same time a tool for legitimizing and strengthening identity [14]. From this perspective, educating the new European generation towards sharing cultural identity acquires political stakes in the EU [15]. Cultural heritage is the place where the tensions inherent in the confrontation between European unity and national identity are discharged [14]. Cultural heritage management is ideologically, politically and institutionally based on nation states [15].

Access to heritage resources is facilitated by education. Meaning, relevance, tradition can be learned. Their learning should be managed as a long-term process, throughout lifetime and in intergenerational contexts. In the case of cultural heritage, it is necessary to give credit to the knowledge of previous generations, and intergenerational encounters are always beneficial [13].

Culture transforms communities and generates jobs [7]. Cultural heritage is also important for the development of local communities and for the economy of the continent [16]. Interest in cultural heritage is linked to its potential to support economic development. However, its effective economic capitalization requires expertise in both management and conservation [13]. Preserving cultural heritage today means ensuring that heritage is shared for the good of people and the environment. Heritage supports sustainable development and well-being. Decision-making and knowledge production related to cultural heritage should be the result of participatory practices. The selection, preservation, interpretation and presentation of heritage resources directly concerns local people, local businesses, public administration and political representatives [14]. The challenges of the 21st century demand a holistic and sustainable model. This means much more than ensuring economic comfort and requires meeting “physical, mental, emotional, social, cultural, spiritual and economic” needs, namely achieving one’s potential [17] (p. 1).

1.3. Teleological Clarifications

Cultural heritage therefore underpins the common European identity, is a source of community cohesion and a dynamic expression of human creativity. As far as the European interest in cultural heritage is concerned, conservation is convergent with sustainable local development. Sustainable enhancement of cultural heritage, which creates well-being, requires community participation, expertise in management and conservation, as well as intergenerational transmission of knowledge and skills. These features, which directly reflect European cultural heritage policies and the consequences of these policies, provide a viable overall framework for dealing with heritage resources. The latter capitalize on resources in various ways, depending on features such as their history and origin.

In this article we present Transylvanian glass icons and the craft of painting them as cultural heritage resources. We will highlight the context in which icons on glass emerged and spread in this area of Romania, the local stylistic differences in the production of icons and their identity related significance. We will also highlight the evolution of the representations of glass icons in the Romanian cultural environment, as well as the interest they raise. Finally, we will discuss the sensitive relationship between reproduction and correction in contemporary icon painting, trying to answer the question: How can this cultural heritage resource be sustainably capitalized?

The aim of this initiative is to stimulate the painting of icons on glass in the traditional way. The discussion of the history of the craft, of the different local ways of painting, and of the effective management of iconography specialization today, in line with the European trend of conservation and valorisation of cultural heritage, is subordinated to this aim. The suggestion we make is also subordinated to the same goal: that the training of glass icon painters should be conducted in the institutional framework offered by schools of arts and crafts.

2. Materials and Methods

The folklorist Ion Mușlea (1899–1966) is considered the initiator and one of the main supporters of the recovery of Transylvanian glass icons as a heritage resource. He published two studies on the subject of icons, Icoanele pe sticlă la românii din Ardeal (The glass icons of the Romanian people in Ardeal) (1928), in the journal Șezătoarea, and Pictura pe sticlă la românii din Șcheii-Brașovului (The glass icons of the Romanian inhabitants of Șcheii-Brașovului) (1929), in the journal Țara Bârsei, and presented a paper in Prague in 1928, on the occasion of the first congress of traditional arts. The paper was published in Paris in the volume of the congress in 1931 under the title La peinture sur verre chez les Roumains de Transylvanie. He gathered a valuable collection of icons and wanted to establish a museum of icons in Cluj-Napoca, the most important of the Transylvanian cities. He did not succeed, but donated part of the collection to the National Museum of Transylvanian History. He maintained his interest in icons and his conviction about their value even after the change of the political regime in post-war Romania, when religiosity and religious manifestations became difficult, even dangerous topics to deal with [18]. Mușlea’s work on icons, written in the 1950s but published in Romania only after the fall of the communist regime, Icons on Glass and the woodcuts of Romanian Peasants in Transylvania [19], is the central bibliographical source for the documentary research we have conducted. We also consulted the extensive study La peinture paysanne sur verre de Roumanie by Iuliana Dancu and Dumitru Dancu [20] and the work Icons and icon painters in Făgăraș Land. Centres and trends in glass icon painting [21] by Elena Băjenaru, current director of the Făgăraș Land Museum “Valer Literat”. The aforementioned work capitalizes on the author’s doctoral thesis. In addition to these works, which we consider very relevant in approaching the theme, we have consulted several other publications that address specific topics of this theme. On the basis of all these works we have outlined the history of religious painting on glass in Transylvania.

In order to exemplify the discussion about the local differences in the manner of painting employed by different icon centres, we have used randomly chosen images from the multitude of icons, reproductions or photographs that are available in works dedicated to the subject, in museums in Romania and in private collections.

Regarding the possibilities of revitalizing the craft, this article uses the results of a participatory observation conducted between 2015 and 2020 in the iconography class of the Popular School of Arts and Crafts “Tiberiu Brediceanu” in Brașov (Romania). The participatory observation was carried out by one of the authors of the article as a student. Data recording was undertaken post-festum. The data concern the iconographic models and attitudes towards tradition promoted in the school. The teacher of the iconography class was informed about the study and agreed to the use of the results of the participatory observation for the elaboration of some papers.

3. Results

3.1. History of Religious Painting on Glass in Transylvania

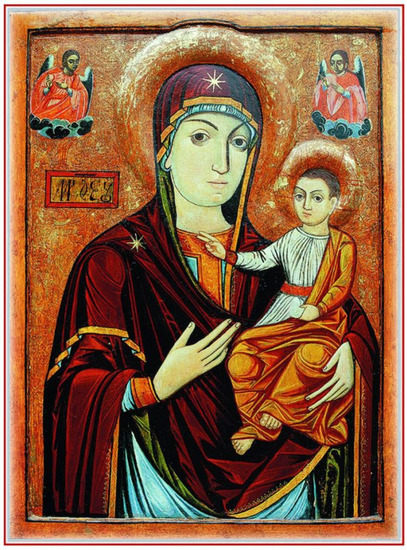

The appearance of icons on glass in Transylvania is, according to traditional accounts, linked to the icon of the Mother of God in the parish church of Nicula which wept at the end of the 17th century (in 1694 or 1699, according to different sources), for 16 days, starting on 16 February [22]. Those oral accounts are supported by the research conducted by Ion Mușlea [19]. The icon was painted on wood in 1681, by priest Luca from Iclod (a village nowadays located in Cluj county). News of the event soon turned Nicula into a place of pilgrimage. The quarrel between the Romanian villagers and the Hungarian Catholic nobleman Sigismund Kornis, the Hungarian governor of Transylvania a few years later, over the hosting of the icon, led to the building of the monastery to house it, upon the conciliatory suggestion of the Austrian Emperor Leopold I, who had been informed of the events in the village [23]. The decision of the local Catholic bishop to assign the icon to the Jesuits in Cluj for safekeeping and the fact that Sigismund Kornis commissioned one or more copies of it triggered a long-running interdenominational dispute over the location of the original icon. It has thus been contended as to whether the original icon was located in Cluj, in the nowadays Piarist church in the town centre, or in the monastery of Nicula. Both alternatives can be accounted for with eligible historical, historiographical or stylistic arguments [23,24,25,26]. All the more so since both icons are credited as working miracles [25]. The icon from the monastery was built into the wall of a believer’s house in the context of the dissolution of the institutions of the Greek Catholic Church (of Byzantine rite) in Romania in 1948, and the persecution of its believers by the communist state [27]. It was founded in 1964 and kept until after 1989 in the chapel of the Orthodox Theological Institute in Cluj-Napoca (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The icon that is currently in the monastery of Nicula, after restoration. Serial reproduction on paper, owned by the authors.

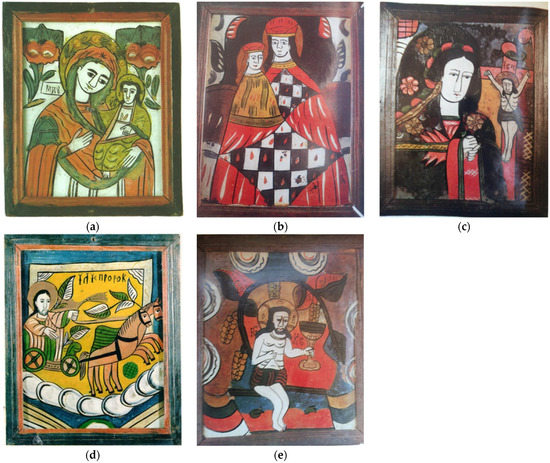

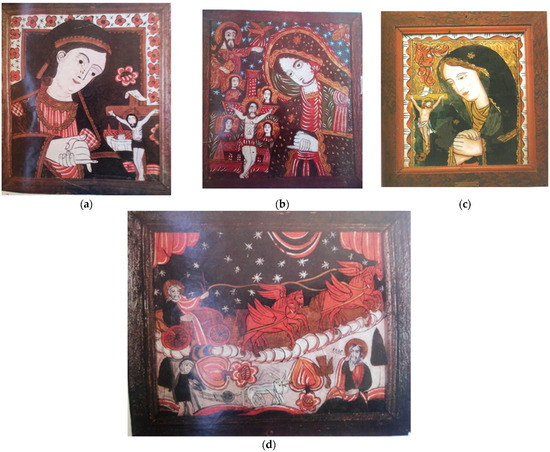

However, as the fame of the pilgrimage site grew, so did the demand for reproductions of the weeping icon. The first reproductions were offered for sale by traders from the West. Then the monks of the monastery began to make reproductions themselves [19]. Those are paintings on glass. The craft of glass painting, which appeared in 16th century Germany [28], was already widespread in the mountainous areas of Central Europe, “in Alsace, Bavaria, Switzerland, Tyrol, Upper Austria, then Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia, as well as among the gurals in Tatra” [19] (p. 9). After a while the local peasants also learned how to paint, moving on from reproductions of icons of the Mother of the Lord to depictions of Jesus Christ and other saints (Figure 2). Nicula thus became a village of icon painters.

Figure 2.

Icons from Nicula. (a,b) Mother of the Lord with Child [31]; (c) Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion [20]; (d) St. Prophet Elijah [31]; (e) Jesus, the vine of life [20]; (f) The prayer from the Garden of Gethsemani [20]; (g) St. George [20]; (h) Table of Heaven [20].

The surplus of icons from Nicula forced some of the villagers to try to sell them, as “made in the monastery” for prestige and profit, further away from their village, in Transylvania. Some of these painters settled in the Sebeș Valley (Laz, Lancrăm), in Mărginimea Sibiului (Săliște, Poiana Sibiului), in Făgăraș Land and in the Bârsa Land. They understood that they would be more successful there than at home in Nicula, where almost everyone was painting. They looked for places close to forests, so they could prepare their glass, or close to already functioning glass manufacturing sites. This is how icon centres appeared along the road to Brașov [19], but also along other trade routes. These routes also acted as disseminators of cultural influence from Central Europe to Maramureș, Bihor, Hațeg, Cluj, Banat, and Bucovina [29]. These influences contributed to the local differentiation of the iconographic style.

Icons on glass are painted on the back of the glass (“Hinterglasmalerei” in German, “reverse painted glass” in England and English-speaking countries, ref. [28]), so that the glass is both the support of the painting and its protective layer. The technique requires reversing the order in which the layers of colour are laid down compared to ordinary painting. Painters used brushes and mineral colours, and later gold leaf and silver paper. During the inter-war period of Muslea’s studies on the technique of painting on glass there was no information on the use of vegetal colours. This is a piece of information that Muslea assumed to be true in the case of the first icons, considering the original Western influences on the craft. In the inter-war period, colours were bought as lumps and ground on stone in the workshop. They were then mixed with glue, spirit, oil, yolk or egg white. The names of the colours are in many cases phonetic adaptations of the corresponding German terms used in the shops of German merchants in Transylvanian towns: “Zinkweiss” for white, “Zinnober” for purple, “Kienruss” for sooty black, etc. The drawing was done with a very thin brush made of cat hair (from the cat’s tail), according to the craftsman’ personal or inherited pattern (Mușlea, 1995). The patterns represented the inverted (mirror) outline of the icon’s model. The drawing was then coloured. At the end, in the remaining areas not covered in colour, such as the saints’ halos or some of the vestments, gold leaf or a cheaper substitute for it was applied with an adhesive. The gold leaf revealed the shades of light generated by the irregularities of the roughly produced glass [22], creating an impression of pomp and surrealism [30].

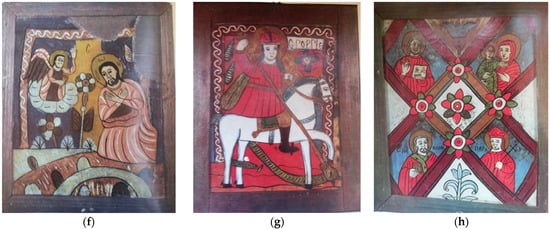

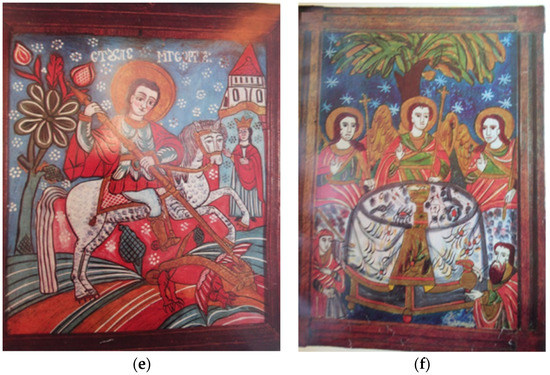

In Nicula and in Șcheii Brașovului (or Șchei, a Romanian district located in the southern part of the Brașov city, close to the mountain, outside the walls of the medieval fortress) large workshops operated that would generate an amount of items that was almost similar to mass production [19]. In Șchei (Figure 3) a limited number of workers (three or five) could paint as many as twenty icons a day, which they sold to the peasants from Țara Bârsei at the fair. The latter acted as intermediaries in the regional trade with icons [21].

Figure 3.

Icons from Șcheii Brașovului. (a) Mother of the Lord with the Child [31]; (b) Birth of the Lord [31]; (c) Jesus, the vine of life (Mystical Winepress) [31]; (d) Saints Archangels Michael and Gabriel [31]; (e) St. George [20].

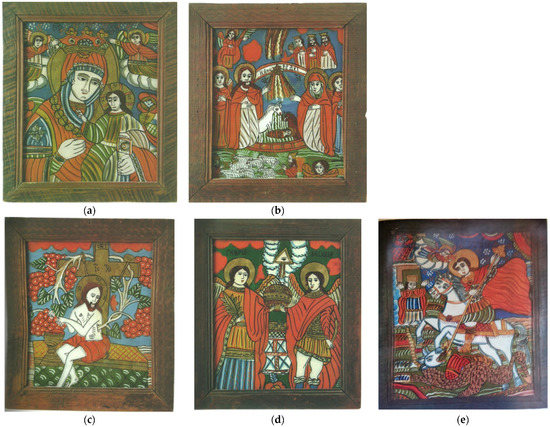

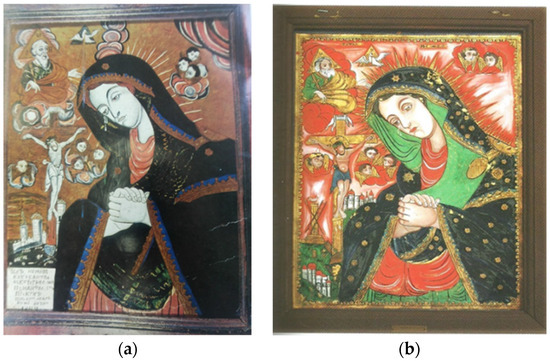

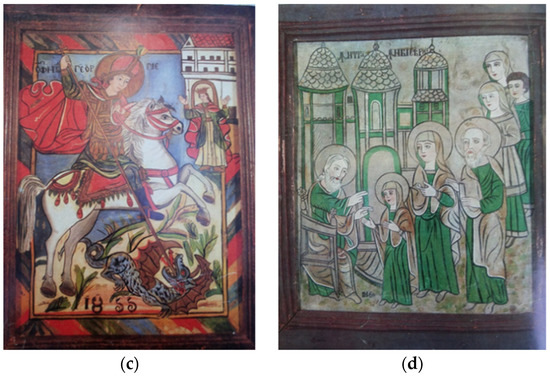

In other centres, e.g., in Făgăraș Land (Figure 4) the production of icons was organised around a famous master, or a good draughtsman. The names of such painters have been preserved, especially those from the 19th century: Ioan Pop from Făgăraș, Savu Moga from Arpașu de Sus (Figure 5), Matei Țâmforea from Cârțișoara. In some centres the prestige and skill of the master was passed on to the next generations, as in the case of the Costea family from Lancrăm and the Poienaru family from Laz. Icons were custom made in such centres. In the case of icons by master painters it is easier to identify Byzantine or Catholic influences compared to the icons painted by the workers in the large workshops.

Figure 4.

Icons from Făgăraș Land. (a) Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion [20]; (b,c) Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion [22]; (d) St. Prophet Elijah [20]; (e) St. George [31]; (f) The Holy Trinity [20].

Figure 5.

Icons painted by Savu Moga. (a) Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion [20]; (b) Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion [22]; (c) St. George [20]; (d) Entry of the Mother of the Lord into the Church [20].

However, both in the large workshops and in the workshops of the famous masters, the differences among generations of painters are visible in the quality of icon production. On the one hand, this was due to the use of old blueprints by less skilled workers who had diminishing capacity to understand what they were drawing or the original intention of the icon painter [19]. On the other hand, the changes in style and technique can also be explained by the creative assimilation [29] of different influences.

During the 19th century, the production of icons and their sale were carried out discreetly, as a direct relationship between the painters and those wishing icons, namely Romanian peasants from Transylvania. The scant and sporadic attention paid to them by intellectuals manifested mainly in the form of harsh criticism, as in the case of Simion Bărnuțiu and George Bariț, prominent Romanian figures in the 1848 revolution. That was also the case of the poets Andrei Mureșianu, who considered the icons “monstrous… and frightening for small children”, and Mihai Eminescu, who considered them “very primitive” [20] (p. 17).

Nicolae Iorga, an important Romanian historian, formulated a similar opinion in the interwar period, referring to the “hideous ugliness” of Nicula icons. However, during that period, a competing representation was gradually gaining ground. European Expressionism, influenced by glass painting in Germany [28], catalysed a re-evaluation of local glass icons in Romania. The Expressionist lens led to a recalibration of artists’ representations of Transylvanian glass painting, which Ion Mușlea, the folklorist, happily recorded. What is more, the poet Lucian Blaga, born in the iconographic village of Lancrăm, recollected the saints “so tenderly” painted by the craftsman in the workshop he often visited as a child. Another important Romanian poet, Ion Minulescu, considered icons on glass “a joy for eyes”. Minulescu’s reference points were mainly icons from the Făgăraș Land. The Bucharest School of Sociology organized an exhibition of such icons in 1933, following a field research campaign in the village of Drăguș (in Făgăraș Land) and at the suggestion of the young painter Lena Constante, a member of the field research team. She was enchanted by the icons discovered in the houses of the peasants. Another Romanian painter, Nicolae Tonitza, enthusiastically pointed out the “new picturesque features” of the icons, which he considered superior in terms of their level of refinement to Western stained glass [19] (pp. 17–18).

Thus, the awareness of the value of Transylvanian painting on glass was consolidated. Research and studies were carried out, conferences and lectures were held on the subject. The aesthetic value of the icons was attributed to the purity of style, the originality of composition and the skill of the icon maker in creatively exploiting the tradition [28]. The process of building up collections of icons on glass, either privately or in museums, began. The ethnographer Romulus Vuia brought icons to the Ethnographic Museum of Transylvania as early as 1928 [19].

After 1947, with the establishment of a programmatic atheist regime in Romania, the explicit interest in the exhibition and appreciation of glass icons declined. A period of denunciation and propagandistic disregard of the Christian faith, which was deemed retrograde, began. Moreover, as we have shown previously, the Greek Catholic Church, with many believers and places of worship in southern Transylvania, was declared illegal in 1948. Collectable icons were moved to little-visited rooms or museum storage. The transfer of Greek Catholic Church property to the Orthodox Church led over time to a trend of replacing the old wooden churches with stone churches. Many of the old glass icons no longer found their place in the new churches, and many of them remained forgotten in the attics of villagers’ houses [21] or parish houses. In the 1980s, the abbot of the Orthodox monastery of Sâmbăta de Sus started a large collection of icons from Făgăraș Land at the monastery, the spiritual centre of the area.

The good intention of the monks of Sâmbăta de Sus was encouraged and was partly sabotaged by the emergence of a network of icon hunters. They persuaded many of the inhabitants of Transylvania to exchange old, smoked glass icons for brightly coloured reproductions on paper of religious paintings. Some of the glass icons collected in this way from rural households ended up in monasteries or museums, many others entered private collections. Whether they donated them to the monastery or exchanged them for beautifully coloured and shiny papers, the Transylvanian peasants parted with a good number of their glass icons. It was also the time of wider changes in rural life in Romania. Attempts to “enlighten”, i.e., to propagandistically promote Marxist atheism in traditional communities considered primitive, is, historically speaking, one of the less dramatic aspects of this transformation. Much more dramatically, many rural communities were directly involved in the anti-communist resistance movement. One of the stakes of the resistance was the Soviet style cooperativisation of agriculture. The Făgăraș Land was one of the important centres of this resistance [32], the memory of which is still imprinted on the way of being of the locals [33] and their tenacity to keep the right to decide on the exploitation of their land [34,35].

After the fall of communism in 1989, there was a revival of religiosity and a reconfiguration of the axiology in Romania. In the horizon of the post-secular rediscovery of the perenniality of religiosity [36], the Christian faith was widely re-assumed, and the prestige of churches and clergy increased dramatically. In this context, interest in icons, important tools for mediating the relationship of the faithful with God and the saints in the Orthodox Church, which dominated Romania, and in the Greek Catholic Church, which had returned to legality in December 1989, was revived. The icon kept in the Nicula monastery until 1948 was restored rather invasively [24,28] in 1991 at the National Museum of Transylvanian History and reinstalled, symbolically, in the monastery in 1992. Religious painting resumed its place in museums and, as timid personal initiatives first, then in an organized setting (in popular schools of arts and crafts, in NGOs and workshops alongside monasteries), the painting of glass icons was also resumed.

3.2. The Identity Dimension of Transylvanian Glass Icons

Returning to old icons, from the period of their spread in Transylvania, they gradually became the centrepiece of peasant interiors [28,29], both from a sacral and an aesthetic perspective. Their original apotropaic function was doubled by that of adornment, with icons “pairing” with painted furniture, painted ceramics and traditional local fabrics [29]. Icons of the Mother of the Lord with the Child began to appear at the top (at the beginning) of the dowry sheets of Romanian girls to be married [19].

Ion Mușlea [19] has inventoried the main themes addressed in the works of Transylvanian icon-makers. These are the Mother of the Lord with the Child; the Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion; then Jesus in various evangelical contexts (Baptism, Entry into the Church, Entry into Jerusalem, Last Supper, Crucifixion, Resurrection), blessing or on a throne, or in the spectacular representation as a Mystical Winepress, with the vine cord coming out of His body; the saints (George, Haralambia, Elijah, Nicholas, Constantine and Helen, John the Baptist, Dumitru, Peter and Paul, the Archangels, Paraskeva), sometimes at the Table of Heaven; and Adam and Eve. Of these themes, the most frequently addressed are those of the Mother of the Lord mourning the Crucifixion, and of saints close to the Romanian peasants, involved by their attributes in rural life or in memorable historical events. These are St. George, a saint of spring linked to the beginning of agricultural activities; St. Dumitru, linked to the autumn harvests; St. Haralambie, the master of the plague; St. Nicholas, the bringer of gifts; St. Elijah, lord of the rains; and St. Paraskeva. The latter is the patron saint of many parish churches in southern Transylvania. Tradition links this to the deep impression left on the locals by the procession of the saint’s relics to Iași (in Moldova, a province in eastern Romania) in the 17th century.

Referring to the Nicula icons, Mușlea [19] highlights the clumsy and simple drawing, the summary composition, the importance of the ornamental border in the composition, the childlike perspective and the vivid colours, as complementary factors responsible for the elementary and authentically rustic impression created by the icons.

These characteristics, together with the tendency to paint mainly close saints, form the background to the regionally differentiated development of the craft. Most of the icon-makers outside the monastery of Nicula were not clerics and the church did not exercise authority over them. They had the freedom to interpret the canons and to insert elements from dogmatics and popular tradition, legends and fairy tales alike, into their creations [28]. It is precisely the interpretative and compositional choices of the icon-makers, validated by the demand for icons in Transylvanian villages that support the identity dimension of the phenomenon.

In Transylvanian glass icons, influences from a heterogeneous mix of sources can be identified. These include biblical texts, Byzantine guidelines, hagiographic texts, frescoes, troughs, Wallachian and Moldavian art, as well as Western and Central European art, popular books, folklore, everyday existence, and the local landscape [37]. The craft of painting flourished in a challenging environment, one that was hostile to the Romanians [38] from a confessional (through the pressure of conversion to Catholicism), social and economic (through the status of “tolerated” nation of the Romanians in Transylvania, which remained in force until the end of the 19th century) point of view. These challenges catalysed the manifestation of Romanian spirituality in the area of freedom represented by the icons on glass.

It is significant in this context that Transylvanian icons are definitely marked by Byzantine influences [28,30,38]. The Byzantine iconographic approach is specific only to Transylvanian icons and differentiates them from the paintings on glass of the Catholic and Baroque religions in Central Europe [38]. The gold leaf used as the background of the icon in all, and only, Transylvanian centres [28,30], and the hieraticism and severity of the representations, especially in the products of the icon centres of southern Transylvania [28], are expressions of this anchoring in Eastern iconography.

It may be that this is precisely what the Expressionist lens of the icons, of which Mușlea [19] spoke, has highlighted: as in the Byzantine iconographic tradition and the ability of its painters to capture and portray human nature transfigured by the reunion of the human with the divine [39] and of earthly reality with heavenly reality (Larchet, 2012). The childlike appearance could conceal a profound knowledge both about the essence of things and about the nature of human knowledge. The emphasis on what is important, interesting and characteristic is a trait that even canonical Eastern icons share with children’s drawings [40].

Moreover, at the intersection of the compositional freedoms assumed by secular painters and the emphasis on the essence proper to Eastern iconography, many novel graphic resolutions have been adopted. In Transylvanian glass icons, only four Apostles may appear at the Last Supper, because only that many can fit in the icon, and at the Table of Heaven only two other saints are seated next to the Mother of the Lord with the Child and the mature Jesus. The braided rope is not a mere decorative element framing the composition, it depicts the dual nature of the Savior [22].

The vivid colours in the icons could also be expressions of the joy that lies at the heart of Eastern Christianity. For Easterners, the Resurrection is more important than the Passion, says Dumitru Stăniloae [41], an important contemporary Orthodox theologian born in southern Transylvania. The salvific Resurrection is the source of this constitutive joy, as highlighted by the Russian theologian V. Losski [42] and, more recently, by Protestant theologian Peter Berger [43].

All these features give Transylvanian icons on glass their specificity and enhance their identity value. These features cannot be seen in isolation from the historical context of the emergence and flourishing of the craft of icon painting. The Nicula icon’s lament is contemporary with the adoption of the Unionist solution, i.e., the transition of the Orthodox Metropolitan of Transylvania, and a large amount of the clergy, to Greek Catholicism in 1698, and the organization of the Romanian Church United with Rome as part of the Catholic Church in 1716. The changeover was not exactly voluntary and was not well received in all Romanian villages or monastic communities in Transylvania. In the southern part of the principality, in the valleys at the foot of the Făgăraș Mountains, there were many Orthodox monks living in small communities. They were at the centre of a movement rejecting union with Rome, which disrupted community life in Făgăraș Land and even led to the fragmentation of communities on religious grounds. Faced with this resistance half a century later, the Austrian general Adolf Nikolaus von Buccow, later governor of Transylvania, burned and demolished the monastic buildings [44]. The location of the old hermitages and monasteries is preserved in the local topographical designations, just as the deaths of monks who refused to leave the burnt or cannon-struck churches are preserved in the collective memory of the locals. The establishment of icon centres in that area and at that time links icons on glass to the confessional turmoil of the Romanian peasants. It makes the spreading of icons part of the response to these upheavals.

3.3. The Craft of Glass Icons in the Iconography Specialization Program in Brașov

In Romania, popular schools of arts and crafts are public institutions of culture with a profile of artistic education and traditional crafts. They operate in the county towns under the authority of the county councils [45]. They carry out educational programs in the field of lifelong learning and organize cultural and artistic activities to promote the performance of their students. The traditional crafts for which specialization courses are organized are different, depending on the local specificity of the tradition. The duration of the training varies according to the complexity of the specialization. Graduation diplomas allow graduates to join craft associations and, in the case of convincing portfolios of work, the Union of Artists.

At the Popular School of Arts and Crafts “Tiberiu Brediceanu” in Brașov there is a class of Iconography. The basic course lasts three years and can be continued with a two-year specialisation. Painting on glass is taught in the first part of the course, i.e., in the first year. Then students learn to paint icons on wood. The teacher is the same and the workshop is shared. It is explained to the students after the first year that each of them will most likely prefer one of the two options (wood or glass) better, that each one has its own subtleties and that the decision to specialize is personal. In general, students aim to improve their skills in the finer art of painting on wood and occasionally return to painting a glass icon. A good glass icon is an appreciated gift.

At the beginning of the first year, students are invited to choose their first icon model. They are provided with catalogues and reproductions of icons from the 18th and 19th centuries. Most of these are icons from Nicula, from the Șcheii Brașovului and from Făgăraș Land, but not exclusively. The collective discussion generated by the students’ choices is an opportunity for the teacher to highlight the distinctive features of icons from different centres. The discussion is taken up and deepened at the following working meetings, when, in parallel with the assisted work on their own icons, students are gradually taught to recognize the centre of origin of the icons they see. In the Iconography class in Brașov, great emphasis is placed on the provenance of the icon chosen as a model. This is also true for icons on wood. Using models of icons that are obviously new or whose origin cannot be identified by their characteristics or dating is discouraged. Chromatic liberties are also discouraged. Apprenticeship in iconography involves the exact reproduction of as many good icons as possible.

The students reproduce the composition of the chosen icon by drawing it freely in pencil, then the teacher corrects the drawing and teaches the students to transpose it (because the painting will be undertaken on the back of the glass). Next comes the stage of tracing the outlines of the composition on the glass, then applying the layers of colour and finally the gold leaf. Throughout this work, mineral pigments and egg emulsion (egg yolk thinned with water and stabilised with a few drops of vinegar) are used as ingredients. Students are taught to identify the correct order in which to apply the layers of colour, from the slightly transparent pink of the cheeks in icons of the Mother of the Lord with the Child to the ornaments of saints’ vestments. Students are also taught to be patient, i.e., to wait for the applied layer of colour to dry thoroughly before applying the next layer. Corrections can be made along the way, but the process of removing the colour from the glass can cause adhesion problems for the next layer of colour. After completion, the icon is sealed, i.e., a protective layer of paper is applied over the painting, glued to the edges of the icon, and the painting is sent for framing. The school works with a master carpenter who makes simple frames, similar to those of old icons on glass.

During the painting classes, the teacher reveals the meanings of the compositional details that appear in the icons. Most of these are references to the Byzantine hagiographic tradition, but there are also local interpretations, which come from the painters’ workshops in Șchei or Făgăraș Land. These revelations help learners to better understand what they are painting and gradually reinforce their sense of belonging to the icon-makers’ class.

During each school year students are invited to participate in two ordinary exhibitions (at Christmas and at the end of the school year) and in extraordinary exhibitions that are generally linked to events and projects in which the teacher is involved.

By the end of the first year, students paint four to five icons. From one icon to the next, the students train their hand (gain confidence in drawing lines) and learn to combine colours. They also train their eye (they learn to select models) and, above all, their critical sense. They can easily spot deviations from tradition and uncover innovations in the icons on offer at contemporary craft fairs. They can also identify good icons at fairs.

Few Iconography graduates make icon painting their main source of income after graduation. For most of the students, painting has the status of a hobby or occasional occupation. Icons are painted as gifts or, less often, on commission. Among the usual students that are present there are usually religious teachers. They learn to paint in order to teach their pupils to paint.

4. Discussion

The EU has promoted unity in diversity. Protecting, preserving, promoting and enhancing cultural heritage supports the building of a European society on the principles of its common heritage [9]. Effective management of cultural heritage facilitates social interaction, creativity, cohesion, identity building, and a sense of belonging and well-being. Cultural heritage strengthens people’s connection to their places of origin, strengthens them against social isolation and toward sustainable development and environmental protection [46]. European cultural heritage is a tool to support local cultural diversity in the context of the homogenizing trend of European integration [3].

The craft of icons on glass is an intangible cultural heritage resource, it belongs to the field of “(e) traditional craftsmanship” according to the classification of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, ratified in 2003 at the UNESCO General Conference [11]. Its promotion follows the EU orientation towards the valorisation of cultural heritage as a resource. Information about heritage should be introduced into the educational process to train young people as custodians of cultural heritage, as Francis-Lindsay [47] considered more than a decade ago. Iconography courses offered by popular schools of arts and crafts could be a viable way of promoting this traditional craft.

Ensuring intergenerational transmission of heritage resources and working with specialists are measures that experts say are effective in managing cultural heritage [48]. These indications apply to the Brașov course and, in theory, should apply to all courses organized under the aegis of county councils. Underlying the institutional guarantee is an effective personnel policy, i.e., putting the right person in the right place.

It is the teacher who guides the students in the choice of the model of the icon to be painted, thus ensuring the correct placement of the novice in the tradition. In Eastern iconography the depictions of saints and biblical, venerational and New Testament scenes are strictly regulated [49]. There are strict indications regarding the positions, clothing, accessories, even beards of the saints. The icon-maker learns the craft and later paints his icons taking into account all these canonical indications, which operate restrictively. The painter’s freedom can manifest within the limits of respect for the canons. Most of the icons are re-workings of earlier compositions or fragments of compositions. They are not simple reproductions, but canonical reinterpretations of models. The first icon painter is, according to tradition, St Luke the Apostle, painter of the Mother of the Lord. Eastern tradition also records the efforts of other holy icon painters, who let the Holy Spirit work through them. This is where the canonical iconographic indications come from. The icons of these saints and the icons inspired by them are the most valuable models. Newer iconographers cannot and do not wish to compete with such. They simply use the knowledge gathered in the craft over two millennia, particularly since their works are recognized as icons in the church, an institution definitively rooted in tradition.

In the case of Transylvanian painting on glass, the problem of relating to the chosen model takes on an extra dimension. If in wood painting it is only a question of respecting the canons, in glass icons the deterioration of the original model must be taken into account and, implicitly, the justified tendency to restore it. Mușlea blamed the repeated mechanical copying, without the worker understanding what the copied drawing represents, without much effort for accuracy and possibly also with an unpractised hand, for the reception of peasant icons on glass as ugly. Their ugliness, Mușlea [19] points out in his attempt to defend them, is not constitutive of them, it must be considered accidental. Judging in this way, today’s icon-maker would be right to try to restore the original drawing, correct the lines and clarify the composition. His attempt would not be innovative, it would take place within the tradition, it would be a return to the origins.

On the other hand, the repeated use of templates available in a workshop, sometimes by successive generations of icon-makers, may have led to a gradual unloading of the materiality of the drawing. This is the case of the large workshops, with almost mass production, at Nicula and in the Șcheii Brașovului. The process may have revealed and encouraged the aptitude for the archetypal in icon-makers, similar to the Romanian Brancusi’s way of sculpting [31]. The educated gaze in expressionism might have seen just that in icons: its operation through archetype. But if that is the case, the way the model has come to be reproduced is the right way, the way that captures the essential. The icon is perfect as it is, the icon maker has nothing to correct. He can only use that model for a new icon.

Between these variations of reporting to the model come sensitive decisions that keep icon painting on glass in the rather narrow area of tradition. We consider that these sensitivities are managed efficiently in the iconography course in Brașov which is a model of good practice. It is about encouraging the use of old icons from Nicula, the Șcheii Brașovului and Făgăraș Land (mostly anonymous icons) as models, with minimal intervention on the drawing. The simplification of the composition to the point of working with archetypes is best seen in the case of the Nicula icons. The icons from Șchei and Făgăraș Land are local and well anchored in Byzantine iconography.

It is also about providing popular arts and crafts schools with two types of counselling at the same time. On one hand, the counselling concerns the iconographic tradition, theological at its origins. On the other hand, it is focused on painting as an artistic approach. The teacher, employed by the school, can be chosen to provide this kind of advice. This is not the case with the monasteries’ glass painting workshops, which are run by monks. In their case, the painter’s theological training suppresses the freedoms of expression gained over time by painting icons on glass. This is not the case for most non-affiliated painters. They move away from tradition and make shady reproductions of classical themes in the name of personal artistic freedom and in the absence of information about the theological significance of the iconographic themes they approach. This is not to say that only the popular arts and crafts schools can support the sustainable revival of the craft of painting icons on glass. There are also good painters, not too many, who are well acquainted with the iconographic tradition and who pass on the craft in a private environment. The popular arts and crafts schools are most likely the only option, as we have shown above, to have the right person for the right job. That is to say, the teacher acting as a guide can provide the aforementioned two-fold advice that would allow students to observe the norms and rules of the craft.

The orientation of the school in Brașov has been taken up by religious teachers in the school glass painting circles they have set up and run in their own schools. Child painters are encouraged to paint the same kind of icons [50,51].

We believe that the situation is similar for crafts such as decorating Romanian blouses or sheepskins and painting Easter eggs. In the case of both of these Romanian crafts, preserving tradition requires knowledge of the meaning of the ornaments applied. They are not just any geometric shapes or flowers. They tell stories about the making of the world and how it works. The person learning to sew, or paint needs instruction in these stories. Learning in such cases is not simply about gaining skills, it is a form of accessing a community of connoisseurs and requires skilled guidance.

Collections of glass icons have been restored to the exhibition spaces of museums in major Romanian cities. Small museums in Transylvania are now also exhibiting icons on glass, whether ethnographic (e.g., Badea Cârțan Ethnographic Museum, The Venetian Village Museum, Junilor Museum in Brașov [52,53,54]) or religious art (e.g., at Sibiel, Cluj-Napoca, Sâmbăta de Sus [55,56,57]). Visual access to this wealth of old icons can support and boost glass painting. It can be valued as a heritage resource. Each of the areas around the old icon centres can take on their local heritage differently.

5. Conclusions

Romanians are religious, but not zealots. Their relation to Christianity is in many cases non-canonical, and associated with surviving pre-Christian beliefs, especially in rural areas on the fringes of Orthodoxy [58,59]. Glass icons, of Byzantine influence but with graphic solutions that often ignore the canons, bringing into the composition both fairy-tale elements and archetypal simplifications, could be an appropriate expression of the religiosity of the Romanians in Transylvania. The craft of glass painting could develop as a regional mark of identity, growing naturally in accordance with the local way of being. For this, good mentors are needed. We believe that today the popular schools of arts and crafts offer the right framework for training future icon craftsmen. The courses held in these schools could start the process of revaluing religious painting on glass in Transylvania. It is, at the same time, a process of educating the demand for icons, of guiding it within the tradition. Good icons, namely those resembling the old ones, bring back memories of grandparents’ or parents’ homes and facilitate a sense of returning to one’s roots. The more contemporaries see good icons, the more likely they are to recognise them as a means to return “home”. In this way, glass painting would fulfil, as with other traditional crafts, a role in supporting the local and community identity. Only by strengthening this identity, i.e., connecting the icons with the way of being of the locals, can the craft of glass painting develop sustainably and become an authentic brand.

Research limitations. The suggestion of sustainable development of the craft of glass icons by means of specializations in iconography at popular schools of arts and crafts is based on the participatory observation carried out in a single class of iconography, the one held in Brașov. We may have discovered, by a fortuitous happenstance, precisely the model of best practices we were looking for. However, the institutional subordination of these schools to the county councils provides a guarantee for the responsible choice of teachers and instructors. On the other hand, even if we have accidentally discovered a model of good practice in dealing with Transylvanian glass painting, it can nevertheless be adopted programmatically in other schools, with the minimally invasive help of some procedural regulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S. and I.M.P.; methodology, D.S. and I.M.P.; investigation, D.S. and I.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S. and I.M.P.; writing—review and editing, D.S. and I.M.P.; visualization, D.S. and I.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ovidiu Gliga, coordinator of the iconography specialization at the “Tiberiu Brediceanu” Popular School of Arts and Crafts in Brașov, for all their knowledge about Transylvanian painting on glass and its local peculiarities. The authors thank Raluca Șerban and Nicoleta Moraru for their information about children who paint icons on glass in their secondary schools in Brașov county.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sciacchitano, E. L’evoluzione delle politiche sul patrimonio culturale in Europa dopo Faro. In Citizens of Europe. Culture e Diritti; Zagato, L., Vecco, M., Eds.; Ca’Foscari Digital Publishing: Venezia, Italy, 2015; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafstein, T. Cultural Heritage. In A Companion to Folklore; Bendix, R.F., Hasan-Rokem, G., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 500–519. [Google Scholar]

- Calligaro, O. From “European cultural heritage”to “cultural diversity”? Polit. Eur. 2014, 3, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex. Treaty on European Union. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:11992M/TXT (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Barca, F. L’Anno europeo del patrimonio culturale e la visione europea della cultura. Digit. Sci. J. Digit. Cult. 2017, 2, 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Borin, E.; Donato, F. What is the legacy of the European Year of Cultural Heritage? A long way from cultural policies towards innovative cultural management models. Eur. J. Cult. Manag. Policy 2020, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://culture.ec.europa.eu/cultural-heritage (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the European Cultural Heritage Strategy for the 21st century, CM/Rec(2017)1. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16806f6a03 (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baltà Portolés, J. Cultural Heritage and Sustainable Cities. Key Themes and Examples in European Cities. UCLG Comm. Cult. Rep. 2018, 1–25. Available online: https://www.agenda21culture.net/sites/default/files/report_7_-_cultural_heritage_sustainable_development_-_eng.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Mäkinen, K. Cultural heritage: Connecting people? Monit. Glob. Intell. Racism 2020, 6, 1–4. Available online: http://monitoracism.eu/cultural-heritage-connecting-people/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Lähdesmäki, T.; Mäkinen, K. The ”European Significance” of Heritage. Politics of Scale in EU Heritage Policy Discourse”. In Politics of Scale: A New Approach to Heritage Studies; Lähdesmäki, T., Zhu, Y., Thomas, S., Eds.; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018: Why It Is Important. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/eu-affairs/20180109STO91388/european-year-of-cultural-heritage-2018-why-it-is-important (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Heritage, A.; Tissot, A.; Banerjee, B. Heritage and Wellbeing: What Constitutes a Good Life? International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM): Rome, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/projects/heritage-and-wellbeing-what-constitutesgood-life (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Sorea, D. The Der Alte Hildebrand Anecdote and the European Dimension of Romanian Folklore. Philobiblon 2019, 24, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mușlea, I. Icoanele pe Sticlă și Xilogravurile Țăranilor Români din Transilvania; Grai și suflet- Cultura națională: București, Romania, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dancu, J.; Dancu, D. La Peinture Paysanne sur Verre de Roumanie; Meridiane: București, Romania, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Băjenaru, E. Icoane și Iconari din Țara Făgărașului. Centre și Curente de Pictură pe Sticlă; Oscar Print: București, Roamnia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggeri, G. Icoanele pe Sticlă din Sibiel; Arti Grafiche La Moderna: Roma, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bota, I.M. Mănăstirea Nicula în Istoria Vieţii Religioase a Poporului Român; Viaţa Creştină: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitran, A.; Hegedűs, E.; Rus, V. Fecioarele Înlăcrimate ale Transilvaniei. Preliminarii la o Istorie Ilustrată A Toleranţei Religioase; Altip: Alba Iulia, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diaconescu, A.; Lungu, V. Minunea de la Nicula. Ziar De Cluj. 16 August 2016. Available online: https://ziardecluj.ro/minunea-de-la-nicula/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Cobzaru, D. Monografia Mânăstirii ”Adormirea Maicii Domnului” Nicula; Renașterea: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sana, S. The Forbidden Church. Greek-Catholics from the North-West of Romania under the Communist Regime (1945–1989); L’Harmattan: Paris, France, 2020; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Purnichescu, A. Icoanele populare pe sticlă—Identitate și specific naţional în România Mare. Rev. De Arte Și Istor. Artei 2018, 1, 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Coman-Sipeanu, O. Icoane pe sticla din patrimoniul Muzeului Astra Sibiu—Colecția Cornel Irimie; Astra Museum Publishing: Sibiu, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lazăr, I.S. Icoanele pe sticlă- ipostaze ale teo-antropologiei populare. In Icoana Transilvăneană pe Sticlă Între Devoțiune Populară și Patrimoniul Cultural; Nicolae, J., Ed.; Reîntregirea: Alba-Iulia, Romania, 2016; pp. 79–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, D. Ion Mușlea, primul doctor în etnografie și folclor al Universității din Cluj. In Universitatea Babeș-Bolyai la 100 de ani. Trecut, prezent și viitor; Buzalic, A., Popescu, I.M., Eds.; Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2019; pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, D.; Bolborici, A.M. The Anti-Communist Resistance in the Făgăraș Mountains (Romania) as a Challenge for Social Memory and an Exercise of Critical Thinking. Sociológia Slovak Sociol. Rev. 2021, 53, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Csesznek, C. The Groups of Caroling Lads from Făgăras, Land (Romania) as Niche Tourism Resource. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Roșculeț, G.; Rățulea, G.G. The Compossessorates in the Olt Land (Romania) as Sustainable Commons. Land 2022, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Csesznek, C.; Rățulea, G.G. The Culture-Centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăras, Land (Romania). Land 2022, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzalic, A. Anthropos- Omul: Paradigmele unui Model Antropologic Integral; Galaxia Gutenberg: Tg. Lăpuș, Romania, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, I.A. Studii de Folclor şi Artă Populară; Minerva: Bucureşti, Romania, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Roşu, G. Icoane pe Sticlă din Colecţia Muzeului Tăranului Român; Alcor: Bucureşti, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Uspensky, L. Teologia Icoanei; Anastasia: București, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Larchet, J.C. Iconarul și Artistul; Sophia: București, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stăniloae, D. De ce suntem ortodocşi. Teol. Şi Viaţă 1991, 67, 15–27. Available online: https://teologiesiviata.ro/arhivatv (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Lossky, V. Teologia mistică a Bisericii de Răsărit; Humanitas: București, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P.L. Orthodoxy and Global Pluralism. Demokr. J. Post-Sov. Democr. 2005, 13, 437–447. Available online: http://demokratizatsiya.pub/archives.php (accessed on 2 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Giurescu, C.C. Istoria Românilor. Vol.III: De la Moartea lui Mihai Viteazul Până la Sfârșitul Epocii Fanariote (1601–1821); ALL: București, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- REGULAMENT CADRU de Organizare Şi Funcţionare A Şcolilor Populare De Arte Şi Meserii. Ordin 2193/2004. Available online: https://lege5.ro/Gratuit/guztmmry/regulament-cadru-de-organizare-si-functionare-a-scolilor-populare-de-arte-si-meserii-ordin-2193-2004?dp=ge2daobxgezdc (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Wellbeing and the Historic Environment by Historic England. 2018. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/wellbeing-and-thehistoric-environment/wellbeing-and-historic-environment (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Francis-Lindsay, J. The Intrinsic Value of Cultural Heritage and its Relationship to Sustainable Tourism Development: The Contrasting Experiences of Jamaica and Japan. Caribb. Q. 2009, 55, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EENC Paper. Challenges and Priorities for Cultural Heritage in Europe: Results of an Expert Consultation. 2013. Available online: https://eenc.eu/uploads/eenc-eu/2021/04/21/07d4959fa85d06c29a0e262d18398e75.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Dionisie from Furna. Erminia Picturii bizantine; Sophia: București, Romania, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Un proiect deosebit la Săcele: “Icoana, parte a sufletului meu”. 2016. Available online: http://www.saceleanul.ro/un-proiect-deosebit-la-sacele-icoana-parte-sufletului-meu/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Stan, O. Rugă De Copil—Expoziție de Icoane Pe Sticlă în Muzeul Codlei. 2019. Available online: https://codlea-info.ro/ruga-de-copil-expozitie-de-icoane-pe-sticla-in-muzeul-codlei/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Muzeul Etnografic Badea Cârțan. Available online: https://transfagarasan.travel/ghid/locatie/muzeul-etnografic-badea-cartan/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Mihalache, S. Cele două Veneții ale României. 2021. Available online: https://eusinziana.ro/cele-doua-venetii-ale-romaniei/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Muzeul Junilor Brașov. Available online: https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=3Ui2acW6baP (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Muzeul Pr. Zosim Oancea din Sibiel. Available online: https://www.sibiel.net/Home_RO.html (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Muzeul Mitropoliei Clujului. Available online: https://www.mitropolia-clujului.ro/muzeul-mitropoliei/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Muzeul “Antonie Plămădeală” Sâmbăta de Sus. Available online: http://www.sambatadesus.ro/manastirea-brancoveanu/ (accessed on 14 July 2022).

- Sorea, D. Two Particular Expressions of Neo-Paganism. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Braşov Ser. VII 2013, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, D.; Scârneci-Domnișoru, F. Unorthodox depictions of divinity. Romanian children’s drawings of Him, Her or It. Int. J. Child. Spiritual. 2018, 23, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).