Visual Identity Based on Ancestral Iconography: A Strategy for Re-Evaluation of the Caranqui Cultural Heritage in the Gualimán Archaeological Site (Ecuador)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cultural, Territorial, and Visual Identity in Ancestral Iconography

2.1. Cultural Identity, Values, and Heritage

2.2. Visual Identity and Ancestral Iconography

2.3. Case Study

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results/Discussion

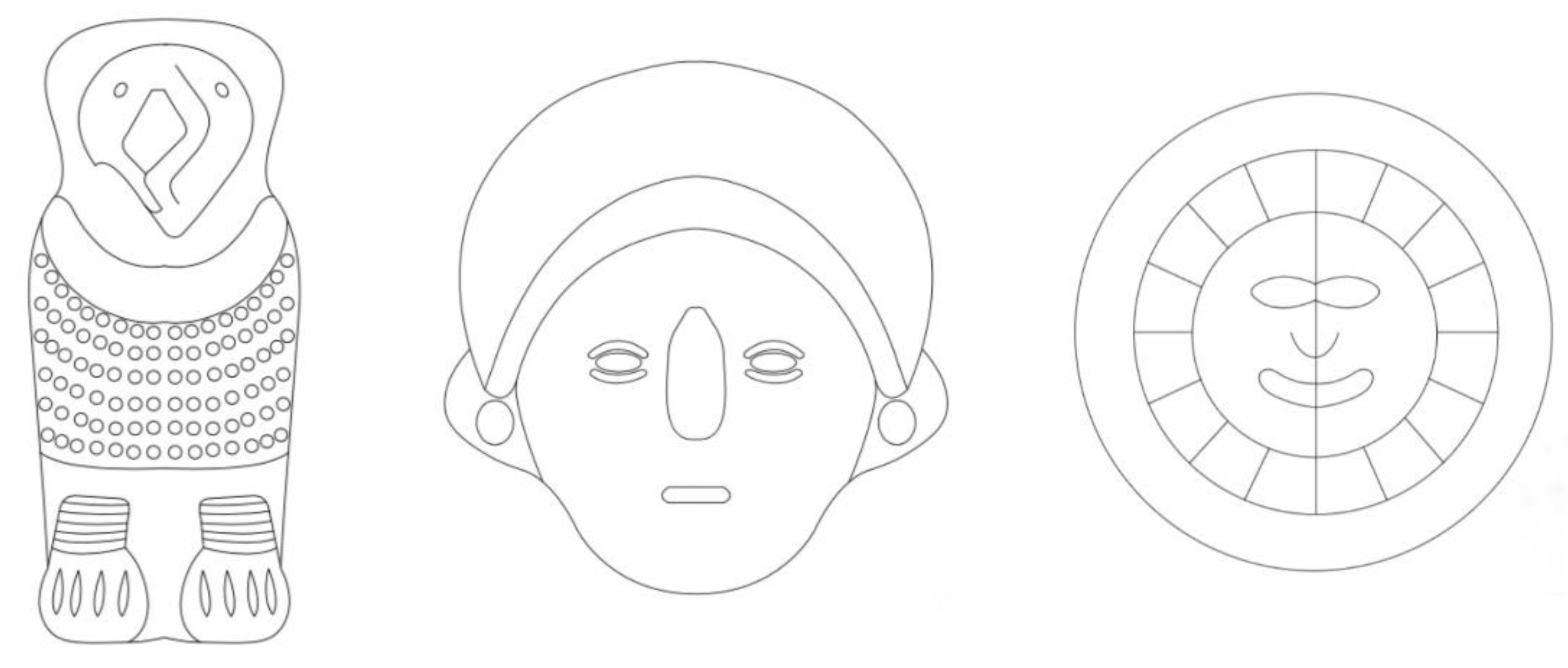

4.1. Visual Identity in the Caranqui Culture at the Gualimán Archaeological Site

4.2. Interview and Survey Analysis

- (1)

- It is proved that the heritage elements have not caused residents to be interested in visiting the Gualimán archaeological site; 47% of those who were consulted have never visited it. Additionally, this information supports the one obtained through interviews with site managers, who indicate that the most interested visitors in Gualimán’s culture are mainly foreign tourists.

- (2)

- 100% of the inhabitants of the area are unaware of the meaning of the word Gualimán.

- (3)

- The high level of lack of knowledge about the culture in general is noted in the results, since 51% of those surveyed think that it was the Incas who inhabited Gualimán. Only 17% were aware that the Caranqui culture was the one that settled here.

- (4)

- A low level of identification of the material symbols of the past is shown, such as vessels, pyramids, funerary mounds, or the purification fountain. However, in relation to the identification of the most significant and predominant archaeological remains in the area, 59% are familiar with the function of the tolas as a funerary object.

- (5)

- For the last question of the questionnaire, the contributions of the inhabitants were fundamental to learning about the appreciation of the archaeological site; they consider it important but at the same time distant and inaccessible for a lot of them; it is confirmed that they know about its existence and believe that its main attractions are the canopy and the Temple of the Sun. They also state that the rituals that are performed should be communicated through radio besides social networks because not everyone uses them. They express that it is a site of great interest and high affluence of foreigners for the celebrated rituals. In reference to the application of ancestral iconography to promote cultural value, making it a strategy for preservation and revaluation, 60% of those surveyed agree with the initiative; they consider that it would be appropriate to identify it and encourage visits by residents and foreigners to the area.

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paredes, B.; Nájera, C.; y León, Z. Morfología del diseño ancestral aplicado al diseño moderno: Una estrategia de preservación del legado cultural. Caso: Comunidad Jatumpamba. AUC Rev. De Arquit. 2016, 37, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Simaluiza, R. Iconografía Precolombina del Ecuador. Aplicación en Obras de Arte Sobre Materiales Alternativos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2017. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=176978 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Banco Central del Ecuador. El Museo te Visita, Museo Numismático del Banco Central del Ecuador. Available online: https://numismatico.bce.fin.ec/index.php/museo/el-museo-te-visita.html (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Ricaurte, L. Diseños Prehispánicos del Ecuador; Banco del Pacífico: Guayaquil, Ecuador, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, F.W. Motivos Indígenas del Antiguo Ecuador; Ediciones Abya–Yala: Quito, Ecuador, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Mussfeld, P.; de Soles, M. Viaje al Círculo de Fuego; Editoral La Caracola: Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fedel, A. Vanessa Zuniga, Embajadora de un Nuevo Vocabulario Visual Basado en las Culturas Precolombinas. Gráffica. Available online: https://graffica.info/vanessa-zuniga-tipografia-basada-en-las-culturas-precolombinas/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Salvador Lara, J. Paleo-antropología física de la región andino-ecuatorial. Humanit. Boletín Ecuat. De Antropol. 1968, 37, 5–50. [Google Scholar]

- ICCROM. Protección del Patrimonio Cultural Durante la Pandemia de COVID-19; Centro Internacional de Estudios de Conservación y Restauración de los Bienes Culturales: Islamabad, Pakistan, 2020; Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/es/news/protección-del-patrimonio-cultural-durante-la-pandemia-de-covid-19 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Rpp Noticias. Canta Wawa: Lanzan Proyecto para Enseñar a los Niños las Lenguas Originarias de la Amazonía. Rpp Noticias, 5 June 2020. Available online: https://rpp.pe/peru/actualidad/canta-wawa-lanzan-proyecto-para-ensenar-a-los-ninos-las-lenguas-originarias-de-la-amazonia-noticia-1270933 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Jambrina, A. Cultura y Patrimonio al Caer el sol en Nueva Edición de la Noche Blanca Praviana. El Comercio, 9 October 2021. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.es/asturias/mas-concejos/cultura-patrimonio-caer-20211009002713-ntvo.html (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Molano, O. Identidad cultural un concepto que evoluciona. Rev. Opera 2007, 7, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ozer, S.U. The Role of Culture in City Branding. In Advertising and Branding: Concepts, Methodologies; Tools, A.I.G., Ibi Global, Eds.; Trakya University: Edirne, Turkey, 2017; pp. 1125–1142. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Nuestra Diversidad Creativa. Informe de la Comisión Mundial de Cultura y Desarrollo; Ediciones UNESCO: París, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Llop, F. Un patrimonio para una comunidad: Estrategias para la protección social del Patrimonio Inmaterial. Revista Patrimonio Cultural de España. 2009, pp. 133–144. Available online: https://ccfib.mcu.es/patrimonio/docs/MC/IPHE/PatrimonioCulturalE/N0/13-Patrimonio_comunidad_estrategias_proteccion.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Bákula, C. Reflexiones en torno al patrimonio cultural. Rev. Tur. Y Patrim. 2000, 1, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Alonso, P. La Construcción de la Identidad Cultural y los Procesos de Cambio Social en las Medianas de la Isla de La Gomera. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/43312 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Teruel, M.D. La Identidad en el Proceso de Puesta en valor del Patrimonio y Como Elemento Estratégico del Desarrollo Territorial; Despoblación y Desarrollo sostenible: La Serranía Celtibérica; I Congreso Universitario Activar la Serranía Celtibérica: Valencia, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño Torralba, L. La dimensión turística del Patrimonio cultural de la ciudad de Lorca, Murcia, España. Cuad. De Tur. 2015, 36, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Alcocer, N. Assessing the path from information sources to loyalty (attitudinal and behavioral): Evidences obtained in an archeological site in Spain. Ph.D. Thesis, Castilla-La Mancha University, Ciudad Real, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reynosa, E. Factores que Afectan la Promoción del Patrimonio Cultural que Destina el Museo Municipal de Moa, a las Escuelas Primarias del Municipio. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Holguín, Holguín, Cuba, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Arévalo, J. El Patrimonio como Representación Colectiva. La intangibilidad de los bienes culturales. Gaz. De Antropol. 2010, 26, 1–31. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/6799 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Warburg, A. El Atlas Mnemosyne 1929; Akal, ed.: Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Melewar, T.C. Determinants of the Corporate Identity Construct: A Review of the Literature. J. Mark. Commun. 2003, 9, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A. Designing Brand Identity: An Essential Guide for the Whole Branding Team; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Zamudio, M.; González Castro, Y.; Manzano Durán, O. Elementos metodológicos para diseñar marca ciudad a partir de la teoría fundamentada. Cuad. De Gestión 2021, 21, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, P. Branding Corporativo. Fundamentos para la Gestión Estratégica de la Identidad Corporativa; Libros de la Empresa: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, J. Una nueva identidad visual corporativa para Consorcio Rdtc S.A. Master’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2011. Available online: https://repositorio.uc.cl/handle/11534/885 (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Chaves, N. y Belluccia, R. La Marca Corporativa. Gestión y Diseño de Símbolos y Logotipos; Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mut Camacho, M. y Breva, E. De la Identidad Corporativa a la Identidad Visual Corporativa, un Camino Necesario; Fórum de Recerca: Castelló, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- González Solas, J. Identidad Visual Corporativa, La Imagen de Nuestro Tiempo; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, J. Imagen Corporativa del Siglo XXI; Editorial La Crujía: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J. The New Strategic Brand Management. In Advanced Insights and Strategic Thinking, 5th ed.; Kogan Page: Londres, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Compte, M. La Estrategia de Comunicación del Patrimonio desde la Comunicación Corporativa y las Relaciones Públicas. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Ramon Llull, Barcelona, Spain, 2016. Available online: https://www.tdx.cat/handle/10803/400386-page=1 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Valero Muñoz, A. Principios de Color y Holopintura; Editorial Club Universitario: Alicante, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pueblos originarios de América, La Whipala. Available online: https://pueblosoriginarios.com/sur/andina/aymara/whipala.html (accessed on 11 February 2022).

- Panofsky, E. Estudios Sobre Iconología; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Barretto, M. Estética y turismo. Pasos. Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2013, 11, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Cavia, J.; Díaz-Luque, P.; Huertas, A.; Rovira, C.; Pedraza-Jimenez, R.; Sicilia, M.; Gómez, L.; Míguez, M.I. Marcas de destino y evaluación de sitios web: Una metodología de investigación. Rev. Lat. De Comun. Soc. 2013, 68, 622–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, S.; Brettel, M. Understanding the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Identity, Image, and Firm Performance. Manag. Decis. 2010, 48, 1469–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J. Arqueología, identidad y patrimonio. Un diálogo en construcción permanente. Revista Tabona 2002, 11, 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Viñals, M.J. (dir.); Mayor, M.; Martínez-Sanchís, I.; Teruel, L.; Alonso, P.; Morant, M. Turismo Sostenible y Patrimonio. Herramientas para la puesta en valor y la Planificación; Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2017; Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/881/88165873013/html/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Calero, C. San Biritute: Representación simbólica del agua. Patrim. Cult. Inmater. 2011, 1, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pappu, R.; Quester, P. Country equity: Conceptualization and empirical evidence. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D. Nuevos retos de la Administración Pública Centrada en los Ciudadanos: Adopción y uso de Servicios Públicos con Base Tecnológica. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotto, C. La problemática del patrimonio cultural inmaterial. Cult. Rev. De Gestión Cult. 2014, 1, 1–22. Available online: https://polipapers.upv.es/index.php/cs/article/view/3162 (accessed on 20 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A. Caranqui-Ibarra. In Transformación Simbólica del Centro Sagrado; Edición CESA-UCE: Quito, Ecuador, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Patrimonio y Cultura. Ficha de Inventario Tolas de Gualimán; Dirección de Inventario Patrimonial: Quito, Ecuador, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Mora, M. Diccionario Etimológico y Comparado del Kichua del Ecuador; Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana, Núcleo del Azuay: Cuenca, Ecuador, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Valarezo, G.R. Áreas Histótico-Culturales del Ecuador Antiguo; Fundación Sinchi Sacha: Quito, Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hostil, O.R. Content Analysis for the Social Sciences and Humanities; Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Sinchi Sacha. Catálogo de Iconografía Ancestral del Ecuador; Sinchi Sacha: Quito, Ecuador, 2015; Available online: http://documentacion.cidap.gob.ec/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=6482 (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Pike, S.D. Measuring a Destination’s Brand Equity between 2003 and 2012 Using the Consumer-Based Brand Equity (CBBE) Hierarchy. Anais, 8. Consumer Psychology in Tourism, Hospitality & Leisure Research Symposium; Cabi: Istambul, Turquia; Wallingford, CT, USA; Inglaterra, UK, 2013; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vásquez, V. Aportación a la Gestión del Patrimonio Desde la Iconografía en Los conjuntos Monumentales Renancentistas del Alto Vinalopó. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/57170 (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Yenîpinar, Y.D.; Yildirim, Ö.G. Destinasyon Markalaşmasında Yerel Simgelerin Logo ve Amblemlerde Kullanılması: Muğla Araştırması. Seyahat Ve Otel İşletmeciliği Derg. 2016, 13, 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Campelo, A.; Aitken, R.; Thyne, M.; Gnoth, J. Sense of place: The importance for destination branding. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Color | Aymara Language | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Red | Chupika | Pachamama. Mother Earth, the telluric energy. The material world, the visible. |

| Orange | Kallapi | Jaqi. To assume responsibility and understand the magnitude of being people when the duality of “chacha-warmi” (man-woman) complements each other. |

| Yellow | Q’illu | Ayni. Reciprocity and complementarity; the energy that unites all forms of existence. |

| White | Janq’u | Pacha. Time and space. Place and time. Cyclical history. A way of life in harmony with the whole multiverse. |

| Green | Chuxña | Manqhapacha. Life and dynamics in the inner world. Akapacha. Life and dynamic in this world, in this plane. |

| Variable | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 164 | 56% |

| Female | 131 | 44% |

| Age | ||

| 15 to 25 | 47 | 16% |

| 26 to 35 | 80 | 27% |

| 36 to 45 | 98 | 33% |

| 46 to 75 | 70 | 24% |

| Self-identification | ||

| Mestizo | 193 | 65% |

| Indigenous | 76 | 26% |

| Afro-Ecuadorian | 15 | 5% |

| White | 9 | 3% |

| Montubio | 1 | 0% |

| Other | 1 | 0% |

| Education | ||

| Not stated | 10 | 3% |

| Post graduate | 8 | 3% |

| Superior | 39 | 13% |

| Post baccalaureate | 32 | 11% |

| High school | 44 | 15% |

| Elementary | 120 | 41% |

| Literacy center | 10 | 3% |

| None | 32 | 11% |

| Economic activities | ||

| Agriculture and livestock | 135 | 46% |

| Manufacturing industry | 30 | 10% |

| Construction | 15 | 5% |

| Trade | 20 | 7% |

| Instruction | 25 | 8% |

| Other activities | 70 | 24% |

| Objective | Question |

|---|---|

| To know the interest of the residents regarding the Gualimán archaeological site. | (1) Have you visited the Gualimán archaeological site? Yes ___ No___ |

| Determine whether the meaning of the word “Gualiman” is known. | (2) Do you know the meaning of the word Gualiman? Yes ___ No___ If your answer is Yes, write the meaning |

| To identify which culture is associated with the archaeological site, according to the inhabitants. | (3) Which of the following cultures do you think lived Gualimán in the past? Caranqui or Cara ___ Inca___ Cañari___ Does not know___ |

| To demonstrate the level of identification that the inhabitants have about the material symbols of the past. | (4) Which of the following archaeological remains do you think the culture that once lived in Gualimán is known for? Ceramics ___ Ceremonial burial___ Tolas ___ Does not know___ |

| To find out the consideration of the inhabitants in the use of ancestral iconography as a means of identification and cultural revalorization. | (5) Do you consider that the application of ancestral iconography in the visual identity of “Gualimán” would help in its identification and re-evaluation of cultural assets |

| Gualimán Archaeological Site | ||

|---|---|---|

| Identity | ||

| Elements | Identification | Observations |

| Graphic identifier (logo) | Does have | Uses several logos of different colors and typographies. It presents the isotype of a base; there are no essential identity features. It does not constitute a powerful identifier of the Caranqui culture. |

| Brand personality | Not defined | There is a perceived absence of a model that identifies it and frames it with distinctive characteristics. |

| Voice tone | Does have | Distant because when expressing itself, it fails to connect with visitors and is not very flexible because it does not adapt to the type of communication it presents. |

| Brand mantra | Does not have | |

| Visual identity system | Does not have | Non-distinctive, non-uniform brand identity. They are presented in many forms and with a variety of colors in the different fonts. |

| Communicational strategies | ||

| Elements | Detail | |

| Type and frequency of communication | Inconsistent | Informative approach. It communicates material and immaterial attributes. Conveys experiences. Does not generate engagement. Interaction almost null. Does not create links. |

| Oficial website | Does have | Basic, no graphic identifier. Own management. |

| Digital channels | Does have | Facebook: presents 3 different fan pages. Instagram: no graphic identifier anywhere. |

| Content verticals | Does have | No information is generated by blocks, there is cultural communication but very general. |

| Brand awareness | Does have | There is no notoriety due to the lack of active communication. Lack of brand communication uniformity in its channels, which affects Gualimán’s image. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Ruiz, I.N.; Teruel-Serrano, M.D.; Miranda-Sánchez, S.I. Visual Identity Based on Ancestral Iconography: A Strategy for Re-Evaluation of the Caranqui Cultural Heritage in the Gualimán Archaeological Site (Ecuador). Heritage 2022, 5, 3463-3478. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040178

Ruiz-Ruiz IN, Teruel-Serrano MD, Miranda-Sánchez SI. Visual Identity Based on Ancestral Iconography: A Strategy for Re-Evaluation of the Caranqui Cultural Heritage in the Gualimán Archaeological Site (Ecuador). Heritage. 2022; 5(4):3463-3478. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040178

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Ruiz, Ingrid Ninoshka, María Dolores Teruel-Serrano, and Sabrina Irina Miranda-Sánchez. 2022. "Visual Identity Based on Ancestral Iconography: A Strategy for Re-Evaluation of the Caranqui Cultural Heritage in the Gualimán Archaeological Site (Ecuador)" Heritage 5, no. 4: 3463-3478. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040178

APA StyleRuiz-Ruiz, I. N., Teruel-Serrano, M. D., & Miranda-Sánchez, S. I. (2022). Visual Identity Based on Ancestral Iconography: A Strategy for Re-Evaluation of the Caranqui Cultural Heritage in the Gualimán Archaeological Site (Ecuador). Heritage, 5(4), 3463-3478. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage5040178