Abstract

Since the 1920s, nearly six identical versions of an ancient printed book, The Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon (南明泉和尙頌證道歌), have been found in Korea. Until very recently, they were believed to be woodblock-printed versions from the 13th to 16th centuries using woodblocks carved from the sheets of a metal-type-printed version from 1239. Two of the six versions were once identified to be woodblock prints in the Goryeo dynasty in the 13th century and designated as Korean treasures in 1984 and 2012. In 2021, one woodblock-printed version printed during the Joseon dynasty in 1526, was designated as a treasure of the Metropolitan city of Seoul, Korea. Historians in Korea have been in heated debate over the printing techniques (metal type print for one version or all woodblock prints) and printing dates (or sequence) of the two versions designated as Korean treasures for the last 50 years. It was almost a never-ending debate with struggles and anger among Korean historians due to the very subjective nature of the examination method and decision-making process by consensus. The heated debates in Korea were never brought to the world’s attention, outside of Korea, and are still considered to be a taboo subject in Korea. To conclude this heated debate with direct evidence of metal type printing of the particular version of interests, all six versions were examined by image comparisons and quantitative analyses of inked areas of individual characters, lines of characters, pages and borderlines. All claims against the possibility of metal type printing of the particular version were reviewed thoroughly. Very clear circumstantial and physical evidence for metal type printing of the version designated as a Korean treasure in 2012 was found. The version carries more than metal casting defects and has the smallest inked area (characters with thin strokes) among all six versions. The version of interest was very likely printed using movable metal type in September 1239, as indicated in the imprint, and is definitely the world’s oldest extant book, printed using metal type in Korea in 1239, predating Jikji (1377) by 138 years and the 42-line Gutenberg Bible (1455) by 216 years.

1. Introduction

In 1999, the Edge Foundation posted a question “1999: WHAT IS THE MOST IMPORTANT INVENTION IN THE PAST TWO THOUSAND YEARS?” [1]. There were many suggestions around the world based on the personal opinion of well-respected professionals. There are no right or wrong answers. Gormley wrote an article entitled “The Greatest Inventions In The Past 1000 Years” [2]. In his article, the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450 was listed as the top invention of all because it allowed literacy to greatly expand. Obviously, the invention of paper [3,4] and metal type and metal type printing [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13] before Gutenberg, in 1450, is as important as the invention of the printing press. The invention of metal type printing in historic records is found as early as 1234 in the Goryeo (高麗) dynasty (918–1392) of Korea [4,5,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. It was more than 200 years prior to the invention of the printing press in Europe. As the title of Carter’s book “The invention of printing in China and its spread westward” published in 1925 suggested, printing was invented in Asia and from there was disseminated to Europe via the Silk Road [4,5]. Woodblock printing was widely practiced in Asian countries, such as China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam, from early in the second millennium [11,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Movable type printing was also invented in Asia. It was first used in China, and the world’s oldest dated extant movable-type-printed book was produced by the Tanguts in 1216 [14,15]. Printing with metal type was a new development introduced in Korea in the 12th–13th centuries [6,7,10,11,12,17].

The oldest extant metal-type-printed book, recognized by UNESCO, to date is Jikji, printed in Cheongju, Korea in 1377 [19,20,21,22]. The 42-line Gutenberg Bible, printed in Mainz, Germany in the 1450s (often referred as 1455), is the oldest metal-type-printed book from the west [2,4,9,10,11,12]. Both Jikji and the 42-line Gutenberg Bible were recognized by the UNESCO Memory of the World program in 2001 [19,20,21,22,23].

A collaborative research project called “From Jikji to Gutenberg” has been started to investigate the technological evidence related to the invention of book printing [24]. The interdisciplinary team is made up of historians, material specialists, conservators and scientists to study what appears to be independent developments that lead to thriving print cultures from Eastern Asia to Western Europe. The project plans cooperative transnational exhibits to commemorate the 650th anniversary of the printing of Jikji in July 2027. UNESCO’s International Centre for Documentary Heritage and the University of Utah’s Marriott Library are leading this project.

It is important to commemorate the 650th anniversary of the printing of Jikji, but the recognition of the 138-year predated metal-type-printed version of The Song of Enlightenment, printed in 1239, should not be ignored or postponed. As the author reported in previous publications [25,26,27], one of the six versions of The Song of Enlightenment (南明泉和尙頌證道歌) with Choi Yi (崔怡: 1166–1249)’s postscript, dated September 1239, is very likely the world’s oldest metal-type-printed book, printed in Korea in 1239, predating the Jikji by 138 years (printed in 1377) and the 42-line Gutenberg Bible by 216 years (printed in 1445).

Two of the six versions were once identified to be woodblock prints in the Goryeo dynasty in the 13th century and designated as Korean treasures in 1984 [28] and 2012 [29], respectively. Their value was already recognized as documentary cultural heritage by Korean historians, as well as by the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea. However, the version of interest has been misidentified and was recognized as a woodblock-printed version [25,26]. In 2021, one of the woodblock-printed versions printed during the Joseon dynasty, in 1526, was designated as a treasure of the Metropolitan city of Seoul, Korea [30].

In this paper, several types of metal casting defects, only seen from printed characters in the version of interest, are direct evidence of metal type printing and are provided and compared with the corresponding characters from the other five versions. Inked areas of individual characters and lines of characters, in all six versions, were quantified by image analysis and used as supporting evidence for the printing sequence determined in the previous studies [25,26,27]. The role of craftsmen, printed at the bottom of the center of every folded leaf, will also be discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Song of Enlightenment

The Song of Enlightenment (證道歌, 证道歌, 증도가), a Chan (禪, 禅, 선, Zen; meaning: mediation or mediative state) discourse, was written sometime in the first half of the 8th century in the Tang dynasty (唐: 618–907) in China. It is also referred to as Song of Awakening or Song of Freedom. There are many different books of The Song of Enlightenment. The particular book of interest in this study is called Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (南明泉和尙頌證道歌) in Korean. The title of the book is often translated as The Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon. As the translation of the title suggested, there are books without commentaries.

It is written in combinations of three-character and seven-character Chinese poems. The full text in Chinese [31] and various versions of English translations are available from various Buddhist research institutes and religious institutes [32,33,34,35]. It is usually attributed to the Zen Master Yongjia Xuanjue (永嘉禪師, 665–713 or 675–713) [9,10,28,29,36,37,38,39,40], but the true authorship of the work is a matter of debate. A number of elements in the writing suggest that either the text has been substantially changed over time or the Zen Master Yongjia Xuanjue may not be the true author [41]. It consists of 105 three-character Chinese poems and 214 seven-character Chinese poems. The Song of Enlightenment consists of 319 poems and 1813 Chinese characters (105 poems × 3 characters + 214 poems × 7 characters = 1813 characters) [27]. They are rather short poems.

To make the poems more understandable to Zen beginners and Zen practitioners, commentaries and interpretations have been added to The Song of Enlightenment. The first commentaries appeared in the 11th century during the Song (宋) dynasty (960–1279) of China. The subject of this study, Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (南明泉和尙頌證道歌; The Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon), is one version of them. The teaching in The Song of Enlightenment has remained popular through the centuries and is still often taught and memorized in Zen practice around the world [35] and translated into many different languages.

2.2. The Six Versions of The Song of Enlightenment (南明泉和尙頌證道歌)

Six nearly identical old books of Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (南明泉和尙頌證道歌; The Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon) were found in Korea from the 1920s to the 2010s. The National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本) was found in the 1920s. The Samseong version (三省本) and Gongin version (空印本) were found in the 1960s–1970s. The Daegu version (大邱本) and Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本) were reported after 2000. The Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) was collected in the library in the 1920s, during the Japanese colonial period, but it was only noticed in recent years and designated as a treasure of the Metropolitan city of Seoul, Korea in 2021 [30]. Details of characteristics of all six versions can be found in previous publications [25,26,27].

All books consist of 44 folding leaves or 88 pages (two prefaces dated 1078, the main text, and two postscripts dated 1077 and 1239). The last page in each version was left blank. All pages, except for page 78, have eight vertical lines of Chinese characters. Page 78 has only seven vertical lines of Chinese characters. Most vertical lines have 15 Chinese characters. Other vertical lines have 2 to 16 Chinese characters depending on sentence structures. Two books, the Daegu version (大邱本) and Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) have extra pages for additional postscripts, indicating actual printing dates of 1472 and 1526 during the Joseon (朝鮮) dynasty (1392–1897) in Korea [42,43,44,45]. There could have been a metal-type-printed version, but that having this postscript does not mean this particular imprint is not made from a woodblock. Prefaces and postfaces from previous editions are always reprinted in later editions.

The printing sequence of six versions was determined and suggested based on image comparisons and analyses of printed images of individual characters, lines of characters, pages of characters and border lines in the cases of two, four and six versions [25,26,27]. Printing sequences were as follows: Gongin version (空印本) in 1239 ⟶ Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本) ⟶ Daegu version (大邱本) in 1472 ⟶ Samseong version (三省本) ⟶ Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) in 1526 ⟶ National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本) [25,26,27].

For easy referencing, alphabetic symbols A through F are assigned to the six versions in the order of printing sequence determined in the previous study: A: Gongin version (空印本), B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本), D: Samseong version (三省本), E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本). To avoid the use of repeated descriptions of the long title of books, the version symbols are frequently used throughout the text.

The origin and history of The Song of Enlightenment can be found in many references [7,8,9,10,11,13,25,26,27,28,29,30,36,37,46].

2.3. Debates over A; Gongin Version (空印本) on Printing Technique and Sequence

The first version available to the public was the F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本) in the 1940s. Ironically, it was the last version of all. It was woodblock printed, long after 1526, the printing year for the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本). Even though it had Choi Yi’s postscript, dated 1239, no one seriously thought that it was printed in 1239 judging from its appearance, such as paper quality, book binding style and so on. The printing technique was easily determined by collectors and historians based on characteristics typical of woodblock printing [10,47].

In the 1960s–1970s, two versions of the D: Samseong version (三省本) and A: Gongin version (空印本) surfaced. The D: Samseong version (三省本) was in excellent condition in terms of paper quality and printing clarity. It also has many chiseling marks and missing strokes due to woodblock damage. It was a very easy task for historians to determine the printing technique as a woodblock print. However, printing date determination was very difficult. Historians have to rely on the Choi Yi’s postscript, dated 1239, and the degree of woodblock damage at the time of printing based on the printing characteristics. With time, wood shrinks and deforms by losing moisture. Thus, woodblocks are prone to damage if proper care is not taken. Age ring patterns of the woodblocks start to appear and they lose small portions of positively engraved characters by chipping. This can happen as early as a few years after woodblock engraving. Historians believed that this version was printed using re-engraved woodblocks, based on an upside-down copy of a metal-type-printed book printed earlier than 1239 [10,39,40]. They self-justified their interpretation of Choi Yi’s postscript as evidence for woodblock making in 1239. The version was finally recognized as from woodblock prints in the Goryeo dynasty in the 13th century. It was designated as a Korean treasure in 1984 [29].

The A: Gongin version (空印本) has also surfaced in the 1960s [46]. It looked to be of very poor quality in terms of paper thickness and uneven printing characteristics. The papers used for the book were very thin and almost semi-transparent. Many characters were not printed clearly, and the users of the book retouched and wrote characters. It was easy to overlook and devaluate the historical meaning of the A: Gongin version (空印本) by comparing with the D: Samseong version (三省本) with exceptional quality of paper and printing. This was a very unfortunate event for the A: Gongin version (空印本). The former collector strongly believed that this version was the original metal-type-printed version, printed in 1239. He launched a full investigation for about 30 years. He tried to publish papers to journals in Korea and held press conferences to express his opinions, but none of them worked in his favor. He wrote his findings as a 178-page long paper in a local history journal in 1988 [46]. In his paper, page-by-page comparisons of the A: Gongin version (空印本) and D: Samseong version (三省本) were included. All of his claims have been denied by reputable Korean historians [10,13,39,40]. He passed away without any success, a very sad story. The A: Gongin version (空印本) became the possession of a Buddhist Monk who is a personal friend of the previous collector. The new collector also believed that the A: Gongin version (空印本) was the original metal-type-printed book from 1239. The new collector filed an application for it to be evaluated as a cultural heritage designation evaluation. The A: Gongin version (空印本) was designated as a Korean treasure in 2012. During the examination process, historians insisted that this version is the woodblock-printed version using the identical woodblocks used for printing the D: Samseong version (三省本). Furthermore, the printing date of the A: Gongin version (空印本) was much later than that of the D: Samseong version (三省本) based on the quality of paper and printing characteristics. Both the A: Gongin version (空印本) and D: Samseong version (三省本) have been recognized by the Cultural Heritage Administration of Korea as woodblock-printed versions from the Goryeo dynasty in the 13th century [29,30]. However, the printing date for both the D: Samseong version (三省本) and A: Gongin version (空印本) had to be restated to a much later date in the Joseon dynasty, perhaps the 15th or 16th century, due to the actual printing date which was found to be intentionally removed pages from the C: Daegu version (大邱本) during the cultural property designation examination process in 2016 [42]. Until 2016, none of the versions had proof of a printing date other than Choi Yi’s postscript dated 1234. The entire evaluation process and results, without solid evidence, are very questionable. Obviously, the credibility of historians who were involved in the examination processes of all versions, and their followers, may be at risk.

2.4. Forbidden Discussion within Korea

It is still considered taboo to raise this issue in Korea. The author has submitted many papers in Korean academic societies including bibliography, history, Buddhism, conservation science, cultural heritage, history of science, etc., in 2022 and was rejected eight consecutive times. The author also received personal warnings from a leader of reviewer group members not to raise this issue in academic journals. The author was told that he can write as many books as he wants about this issue, but he cannot, and should not, publish a single paper. The author does not think this is a very healthy academic environment for any scholar, in particular entry-level researchers and newcomers to the field. This is one of the reasons why the author tries to share the background and situation of this very issue with respected researchers around the world, by publishing a series of papers outside Korea.

As reported previously, the only versions with actual printing dates are the C: Daegu version (大邱本) and E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) which were examined [26,27,36,37,42]. During the application examination for the cultural property designation of the D: Daegu version (大邱本), the intentional removal of the prayer or epilog (跋文), written by Kim Su-on (金守溫: 1410–1481) and dated June 1472, was discovered and resulted in application denial in 2016 [42]. The F: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) was a part of the former collection of Queen Sunjung Hyo (純貞孝皇后) and the family of Imperial Korea was collected by the Jongno Branch of the Library of Seoul under the Japanese colonial government in the 1920s [30]. It was opened to the public to view in the 2010s. The additional imprint after Choi Yi’s postscript date 1239 of the F: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) revealed that the woodblock was re-engraved at the Simwonsa Temple (深源寺) in Mt. Jabi (慈悲山), Hwangju (黃州) (which is currently a part of North Korea), in 1526 [34,35,41]. The factual printing dates for the C: Daegu version (大邱本) and E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) are 1472 and 1526. These dates can be used for printing sequence and printing date references for the other four versions.

Korean historians against the recognition of the A: Gongin version (空印本) being the original metal type print in 1239, claim the following three issues. They are:

- (i)

- It is identical to the D: Samseong version (三省本);

- (ii)

- Paper and printing quality is poorer than for the D: Samseong version (三省本);

- (iii)

- There are eleven names of craftsmen (possibly woodblock engravers) printed at the bottom of the folded leaves.

These are their reasons for denial. They even confirmed that some of craftsmen were found from the woodblocks of Tripitaka Koreana engraved during the Goryeo dynasty in the 13th century [47]. In the author’s opinion, the issues can be easily refuted with convincing evidence. Details can be found in the following sections.

2.5. Image Comparisons Using Image Analysis Software (PicMan)

In the previous reports, image comparisons and analysis results on all six versions were introduced [25,26,27,48,49]. Page-by-page, line-by-line and character-by-character image comparisons and analyses were done using image analysis software (PicMan from WaferMasters, Inc., Dublin, CA, USA.). Rather qualitative comparisons and analysis results were provided in the previous reports. The image analysis software, PicMan, was developed and used for automatic and quantitative analysis of any types of digital images in almost every field, including semiconductor, materials science, nanotechnology, food industry, biology, medical research, and colorimetric applications. In this paper, more quantitative analysis results are discussed to avoid ambiguity and subjectivity. The same image comparison and analysis can be done by combinations of other commercial or opensource image analysis software, such as Photoshop, Illustrator, Paint, Lightroom, Image J, etc. However, the implementation becomes very complicated and very time consuming.

The key differentiation factor of PicMan from other commercial image manipulation or editing software is the ability to perform quantitative analysis in addition to the functions of other software and to export edited and analyzed data in various image formats, as well as the numerical data in spreadsheet formats of CSV (comma-separated values) where additional statistical analyses may be desired. The exported numerical data can be used as valuable source data for further numerical analyses and statistical reasoning as demonstrated in the following section of this paper. Application examples of PicMan in conservation and restoration of cultural heritages have been reported in recent years [25,26,27,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Several new functions such as image overlap, image subtraction, image division, outline generation, image crop, background color removal, transparency application and coloring of selected areas were developed for this study. The ease of image comparisons, visual presentation of comparison results and quantitative analysis results were one of the top priorities in developing the image analysis software, PicMan. A Korean book titled Digital Image Analysis Program Manual for Diagnosis of Conservation Status of Painting Cultural Heritage that uses PicMan was published with application examples in cultural heritage characterization and analysis by Konkuk University and the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (Korea) [56].

3. Results and Discussion

The image comparisons and analyses were performed page-by-page, line-by-line and character-by-character for all six versions using PicMan [26,27,28]. Potential clues and evidence for leading the verification of the printing technique and printing sequence of each printed version were searched. In this study, printing characteristics peculiar to the A: Gongin version (空印本) were searched and compared with the other five versions. The validity of the three points upon which Korean historians are relying to oppose the recognition of the A: Gongin version (空印本) as the original metal type print in 1239, as written in Choi Yi’s postscript, were examined based on the image comparisons and analyses results.

3.1. Untold Customs in Woodblock Duplication

Figure 1 shows a screen capture of PicMan measuring the 2nd character 相 in line 8, on page 1, of five versions except for the B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本). The first folding leaf for pages 1 and 2 is missing and image was not available for comparison. Approximately 270 dpi resolution image was used for analysis of individual characters. The image size of all versions was adjusted before making image comparisons and quantitative analyses.

Figure 1.

A screen capture of image analysis software (PicMan) highlighting a defective character 相 (the 2nd character in line 8 of page 1) in five versions. Inked areas of the character 相 in all versions were measured in pixels for comparison. The first leaf (page 1 and page 2) of one version is missing. A small dot on the top left of character is formed by metal casting defect and was duplicated until the version D by woodblock engravers. (A) Gongin version (空印本), (B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)).

The character 相 was selected for image comparison because it has very distinctive errors in stroke. The character相 is made of a 木 (tree) and 目 (eye) character components. The character 木 (tree) should have a continuous straight line at the center. It is a very common and basic Chinese character which even a beginner in Chinese language would understand. The character 相in three versions (A, B and D) has a small dot on top of strange combinations of strokes never used in Chinese characters. If the original versions were woodblock printed, there is no way to make this character in this weird shape. The character 相 was used 48 times in The Song of Enlightenment. The metal casting defect in the 2nd character in line 8 of page 1 was the only case. If it were the woodblock engraver’s intention to do it that way, why were the other 47 characters of 相 normal? The shape of the character 相 in the three versions was very strange. The other two versions (E and F) have corrected the mistakes. From this fact, all versions can be classified to versions before and after 1526 of the printing year of the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本).

As reported previously, all six versions looked identical or similar, but they were printed using different printing templates, regardless of metal type or woodblock [23,24,25,46,47]. In the author’s opinion, the defect in the character 相 is from a metal casting error in the version A: Gongin version (空印本). Woodblock engravers of the C: Daegu version (大邱本) 1472 and D: Samseong version (三省本) simply duplicated as printed in the upside-down copy on the woodblocks. It was a very long tradition of duplicating someone’s work. It also applies to the names on the bottom of every one of the folded leaves. Thus, the names are not the woodblock engravers name at all. The C: Daegu version (大邱本) was printed using woodblocks in 1472. It is 233 years after the first publication year of 1239. No woodblock engravers can live and be on active duty in woodworking for 233 years. It is out of the question. The Korean historian’s famous claims are baseless.

The impression on the character 相in three versions (A, B and D) can be different from person to person. It is a very subjective matter. Some may say they are identical. Some may say they look similar. Others may say they are the same, or the difference may be due to variations in printing using the identical printing template. In the case of the E and F versions, no one would argue that they are different from each other and absolutely different from the versions A, C and D.

How can we get a consensus on the versions A, C and D? The shape of the defective dot on top left of the character 相 looks different, but it is also a very subjective opinion based on an individual’s personal impression. One thing we can assume is that the quantitative measurements of inked area and its trends between versions can provide additional clues. The inked areas of the character 相 in different versions were measured using PicMan. The inked area in the A: Gongin version (空印本) was 2839 pixels while the inked areas in C: Daegu version (大邱本) and D: Samseong version (三省本) were measured to be 4554 and 4236 pixels, respectively. From the A: Gongin version (空印本) to the C: Daegu version (大邱本) and D: Samseong version (三省本), the inked area has been increased by 60.4% and 49.2%. If the same template was used for printing all three versions of the A: Gongin version (空印本) to the C: Daegu version (大邱本) and D: Samseong version (三省本), the double-digit percent (60.4% and 49.2%) increase of inked area of the same character 相 cannot occur between versions. Between the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本), both the shape and inked areas of the characters are significantly different and no questions will arise.

Across the entire book of The Song of Enlightenment, more than 10 cases of missing or broken strokes were found in the A: Gongin version (空印本) and almost all metal casting defects were duplicated in the B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本) and D: Samseong version (三省本). Completely new-style characters were engraved in the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本). In addition, the names at the bottom of folded leaves have disappeared from the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本).

3.2. Unplanned Mistakes

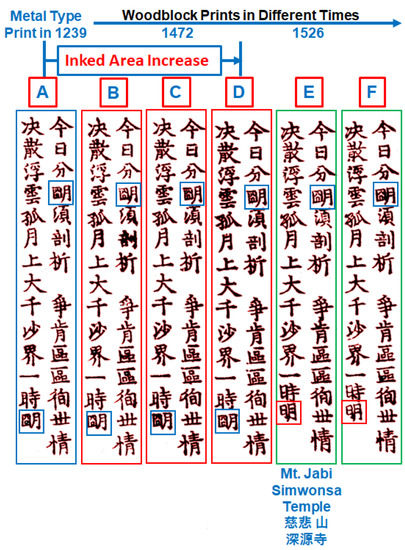

Noting Figure 2 images of page 10 (the backside of 5th folded leaf) of all six versions, two lines (line 4 and line 5 from the right) containing 28 characters (14 characters per line) are highlighted by red rectangles for character image comparisons and inked area measurement of individual characters. These two lines contain a specific character of 朙 (old-style character of 明) in each line.

Figure 2.

Images of page 10 (the backside of the fifth folded leaf) from all six versions of The Song of Enlightenment in the order of printing determined by previous studies.

Figure 3 shows a screen capture of PicMan highlighting the character of interest 朙 in line 4 and line 5 on page 10, of all six versions. To fit to a screen, images with an 87-dpi equivalent resolution were used. The 4th character in line 4 and the 14th character (last character) in line 5 are highlighted with red squares for easy comparisons. As seen from Figure 3, the 4th character in line 4 in all six versions shows the old-style character 朙. However, the 14th character (last character) in line 5 is different. The versions A to D have used the old-style character 朙 and the versions E and F used the new-style character 明. It was neither intentional nor planned usage. If it was an intentional or planned change, all old-style characters of 朙 should be replaced. Only 2 out of 47 old-style characters of朙 have been mistakenly engraved to the new-style character of 明 (the 2nd character in line 4 on page 5 (the front side of the 3rd folded leaf) and this one (the 14th character (last character) in line 5 on page 10).

Figure 3.

A screen capture of image analysis software (PicMan) highlighting two characters of 朙 in all six versions in printing sequence from 13th to 16th centuries. Two characters of 朙 on the bottom right have been changed from an old-style character 朙 to a new-style character 明 during woodblock duplication by engraver. (A) Gongin version (空印本), (B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)).

According to the customs in woodblock duplication practices, not only the same style of characters, but also defects, were to be duplicated. However, sometimes unintentional mistakes were made due to the subconscious actions of woodblock engravers. These mistakes, due to human factors, can provide additional insight into the woodblock duplication process at the time. When the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) was engraved in 1526, it was almost 300~400 years after the 朙 → 明 transition.

In The Song of Enlightenment, the old-style character 朙 was used 47 times, and the new-style character 明 was used once in Choi Yi’s postscript dated 1239. At the time of writing the postscript, in 1239, the old-style character 朙 had been replaced with the new-style character of 明. The main text was written in 1078, and it is 161 years before Choi Yi wrote the postscript in 1239. It is not surprising to see this type of mistake during the woodblock duplication process. It is more surprising that the number of mistakes is so small.

3.3. Inked Area Measurements and Statistics

Inked areas of all 28 characters in line 4 and line 5 on page 10 (the backside of 5th folded leaf) of all six versions were measured. Figure 4 and Figure 5 show as-cropped images and after-inked area separation. The printing techniques, printing sequence and printing dates determined in the previous study were also indicated as guidance. The characters 朙 or 明 in the combined images were highlighted with red squares for easy recognition and visual inspection of the difference in style and relative position, with respect to other characters. Versions A to D showed monotonic increase in inked area by thickening of strokes from version A to subsequent versions. The versions E and F showed not only the 朙 → 明 transition of the last character in line 5, but also the upward shift of character 明 from the four previous versions A though D.

Figure 4.

Cropped images of 28 characters and border lines in line 4 and line 5 of page 10 (the backside of fifth folded leaf) in all six versions for inked area measurement of individual characters in different versions by image analysis. (A) Gongin version (空印本), (B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)).

Figure 5.

Printed characters were extracted and highlighted by red outlines using PicMan for character shape inspection and inked area measurement. Two characters of 朙 highlighted by red squares on the bottom right have been changed from an old-style character 朙 to a new-style character 明 during woodblock duplication by the engraver. (A) Gongin version (空印本), (B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)).

Table 1 summarizes the inked area measurement results on 28 characters in line 4 and line 5 on page 10 of all six versions of The Song of Enlightenment. Changes in the inked area of 28 individual characters of 今日分朙湏剖析爭肯區區徇丗情 in line 4 and 决散浮雲孤月上大千沙界一時朙 in line 5 were measured in pixels. A combined image with an 87-dpi equivalent resolution were used for the inked area measurements. The total inked areas of 28 characters in six different versions were also calculated. The ratios of inked area change with respect to the A: Gongin version (空印本) gives a general idea of changes in inked area in the versions printed at later times. The ratios of inked area change with respect to the immediate prior versions were also calculated to demonstrate version-by-version changes of the total inked area for 28 characters. It should be noted that the versions E and F have the new-style character 明 instead of the old-style character 朙. The effect of this 朙 → 明 transition on inked area measurement is negligible.

Table 1.

Summary of inked area measurement of 28 characters in line 4 and line 5 on page 10 of all six versions of The Song of Enlightenment (南明泉和尙頌證道歌; Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon) printed with different techniques from the 13th and 16th centuries. (A: Gongin version (空印本), B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, D: Samseong version (三省本), E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)). (Unit: Pixels).

Figure 6 shows a bar graph of the sum of inked areas for 28 characters as a function of the printed versions A through F, in pixels. Two blue vertical lines were added to show the timing of printing technique changes (between the versions A and B) and entirely new woodblock duplication in 1526 for version E. The total inked area in the A version was measured to be 37,298 pixels and is the smallest of all versions. The total inked areas in versions B to D monotonically increased up to 47,479 pixels, which accounts for a 27.4% increase by thickening strokes caused by woodblock duplication between versions. The inked area measurement error is less than 0.5% of total area. The difference in inked area between versions is statistically significant. The change of inked area between versions is not from the wear and tear of the identical woodblock. The duplicated woodblock-printed versions of B to F are printed using newly duplicated woodblocks over 300 years, from the 13th to 16th centuries, as reported in previous studies [25,26,27].

Figure 6.

The sum of printed areas of 28 characters in line 4 and line 5 of page 10 (the backside of the fifth folded leaf) from medium resolution images of all six versions. Two characters of 朙 (one character per version) have been changed from an old-style character 朙 to a new-style character 明 during woodblock duplication for the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本) by engraver. Effect of this character change in inked area measurement is negligible. Measurement error for the inked area is smaller than 0.5%.

When duplicating woodblocks, woodblock engravers tend to hesitate to cut inside the characters on the upside-down copy on woodblocks. This is the psychology of woodblock engravers and expected human behaviors. Versions E and F showed the opposite trend of inked area shrinkage indicating a sign of different versions of duplicated woodblocks. As reported in the previous study, a few characters in the version E were omitted and modified in version F when the new woodblocks were engraved for duplication [27].

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the inked area measurement results on individual characters of the four nearly identical versions of A to D. The overall trends of inked areas to increase version by version was verified except for a few characters (剖, 析, 區 in line 4, and 决, 月 in line 5), printed with excessive ink coverage in version B. This trend of sequential increase of the inked areas among nearly identical versions of A to D also suggests the printing sequence determined in the previous study are logical conclusions [26,27]. As seen from Figure 4 and Figure 5, it is impossible to make conclusions based on the first impression or uncertain memories of different versions seen in separate places and at different times.

Figure 7.

Trends of version-by-version printed area increase of 14 individual characters (今日分朙湏剖析爭肯區區徇丗情) in line 4 of page 10 (the backside of fifth folded leaf) from medium resolution images of the four nearly identical versions (A: Gongin version (空印本), B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, D: Samseong version (三省本)).

Figure 8.

Trends of version-by-version printed area increase of 14 individual characters (决散浮雲孤月上大千沙界一時朙) in line 5 of page 10 (the backside of fifth folded leaf) from medium resolution images of the four nearly identical versions (A: Gongin version (空印本), B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, D: Samseong version (三省本)).

It is important to get assistance available from experts from different fields to draw objective conclusions. Previous conclusions, made long ago without trustworthy evidence, can no longer stand. At that time, much less information was available compared to today’s understanding and only three versions of A, D, F [9,10,13,35,40].

3.4. Metal Casting Originated Defects

Various types of metal casting, causing defects in the A: Gongin version (空印本), have been found and classified into four categories. Four examples per defect type are summarized in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 9.

Images of four selected characters (聞, 相, 佛, 來) with obvious metal casting defects in the original version (A: Gongin version (空印本)) and subsequent re-engraved woodblock-printed versions (B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, D: Samseong version (三省本), E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)). Metal casting defects highlighted in red color were precisely duplicated by woodblock engravers until the D: Samseong version (三省本).

Figure 10.

Images of four selected characters (折, 惡, 見, 行) with obvious metal casting defects and mistakes in the original version ((A) Gongin version (空印本)) and subsequent reengraved woodblock-printed versions ((B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)). Metal casting defects and mistakes, highlighted in red color, were precisely duplicated by woodblock engravers until certain versions.

Figure 11.

Images of four selected characters (意, 續, 𢙉, 岸) with noteworthy characteristics, including mistake in 續 and rare style of 𢙉 for 惱, in the original version ((A) Gongin version (空印本)) and subsequent re-engraved woodblock-printed versions ((B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)). Mistake correction, character style change and appearance of new mistakes have been found in subsequent woodblock-printed versions.

Figure 12.

Images of four selected characters (貧, 勞, 力, 山) with obvious metal casting defects only seen in the original version ((A) Gongin version (空印本)). The metal casting defects were corrected in subsequent reengraved woodblock-printed versions ((B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)).

3.4.1. Defect Type A: Broken Stroke

Figure 9 shows four examples of metal casting originated defects, highlighted in red color, which caused broken strokes in characters of 聞, 相, 佛, 來 and their influences in subsequent versions. These defects were very obvious to people, even people with an entry level of knowledge of Chinese dialects. The defects were duplicated until version D because the character can be legible and then corrected from versions E and F. When we closely examine the differences of the four characters 聞, 相, 佛, 來, position, shape and size of broken strokes found in versions A to D, are not identical. This cannot happen if the four versions of A to D were from identical woodblocks.

All characters in versions E and F were significantly different from the previous versions. Broken strokes have been corrected. The character 來 in version E and F were heavily tilted and the size of the characters has been modified significantly. All these observations need someone’s time and dedicated efforts. The author is certain that none of the Korean historians paid sufficient enough attention to draw conclusions.

3.4.2. Defect Type B: Excessive Strokes and Unnatural Strokes

Figure 10 shows four examples of metal casting originated defects caused confusion in subsequent versions. The excessive stroke in character 折was printed similar to character 拆 in the version A. It was carried all the way to the version F with a different style character implying, neither the woodblock engraver, nor a proofreader, understood the true meaning of the text. In the case of the character 惡, the top right portion became an extra dot in the version A. It was duplicated in the version B but corrected from the version C and forward.

For character 見, two short extra strokes near the bottom right were printed in the version A. If woodblocks were used, this type of mistake would never happen. It is a perfect sign of metal casting related defects. The wooden type engraver must have made a mistake during wooden type making processes for metal casting molds. This mistake was duplicated until the version D. The extra strokes have been removed from the version E to F. The character 見 was used 44 times. This is the only case with the extra strokes. It is a very rare case.

In the case of the character 行, a vertical stroke in a radical on the left came out to be too thick. It is a metal casting originated defect. This shape was somewhat mimicked in version B. In version C, the vertical stroke became more natural but tilted to the clockwise direction. In version D, the majority of the vertical stroke is missing. For the versions E and F, it looks totally different in shape and thickness.

By comparing the excessive strokes and unnatural strokes with the characters in the newly engraved versions E and F, it is easily speculated that the unnatural strokes cannot be printed without the metal casting originated defects in the version A.

3.4.3. Defect Type C: Shape Change and False Character

Figure 11 shows four examples of shape change of characters between versions, and false character corrections in subsequent versions. The character 意 in the version A became much larger in the versions C and D. The top portion of 意, and 立became 亠 in the versions E and F, due to the mistake made by engravers of the woodblocks of the version E, in 1526. The woodblock engraver for the version F just followed the previous version, according to the tradition.

In the case of the character 續, the top portion of a radical on the right is printed to 亠 instead of 士 due to the mistake in metal type casting in the version A. The same mistake was repeated in the version B by duplicating a woodblock exactly. There is no Chinese character like this. It was an obvious mistake. In the versions C and D, it was corrected to 士, but the woodblock engraver was hesitant to change the original shape and the spacing between the two horizontal lines in the 士 portion became narrower even though it becomes a very unnatural looking character of 續. In the versions E and F, the spacing was adjusted and the character took on a more natural form. The hesitation of a woodblock engraver at the time of their work can be felt from the subtle shape change of characters between versions.

The character 𢙉 (an old form of 惱) in versions A to D was also changed to an uncommon form of an equivalent character 惱 in versions E and F. The bottom right portion of the character, 山 was changed to 田. From version C to the version D, the stroke became much thicker confirming the versions C and D are printed using different woodblocks.

There are some cases that require unexpected change during woodblock duplication due to the condition of woodblocks. The character 岸 seems to be such a case. The stroke extended towards the bottom left in versions A and B and became shortened. The angle from the horizontal stroke was changed in the versions C and D. It could be due to the condition of the woodblock of version C. There are no other explainable reasons. The version D must be a simple duplication of version C. The versions E and F do not resemble any of the previous versions.

All of these phenomena are enough to justify that all versions were printed using different templates whether they are metal type or woodblocks. The metal casting originated defects in the version A are direct evidence for metal type printing.

3.4.4. Defect Type D: Isolated Metal Casting Originated Defects

Figure 12 shows four examples of isolated metal casting originated defects in 貧, 勞, 力and 山characters only found on the version A. Other than the version A, these metal casting originated defects have been completely removed in other versions. It is the clear evidence that can serve as proof of the A: Gongin version (空印本) being the metal type print.

Based on this evidence, it is safe to claim that the A: Gongin version (空印本) of The Song of Enlightenment is the original metal-type-printed version from 1239, as written by Choi Yi.

3.5. Surface Characteristics of Woodblock and Metal Type

Woodblock printing is a book created by engraving and printing writings using a wooden plate (woodblock). Woodblock making starts with calligraphy on paper done by a master. It can also be done by duplicating a movable type or woodblock print. The paper is put upside-down on a flat wooden plate. The characters on the page are see-through from the backside of the paper. Then, the engravers cut the woodblock by cutting outside of printed characters face-down on paper on the woodblock. The ink is applied on the block and paper is pressed on top of it and rubbed. Multiple copies cannot be made at once. The book making process is long and very costly. In Korea, they were initially created mainly to publish Buddhist canons. Later on, the usage became more diverse and general. The woodblock printing was used to publish philosophic ideas, academic papers, collections of essays and other various documents [13].

Figure 13 shows woodblock images of the Tripiṭaka Koreana (Goryeo Tripiṭaka) or Palman Daejanggyeong (“Eighty-Thousand Tripiṭaka”) images showing flat surface of engraved characters on woodblocks [57,58]. The Tripiṭaka Koreana was fabricated in the 13th century Goryeo dynasty of Korea. The surface of engraved characters is very flat and generally results in uniform printing. Dark black ink, Songyeonmuk (松煙墨), is used for woodblock printing.

Figure 13.

Woodblock images of the Tripiṭaka Koreana (Goryeo Tripiṭaka) or Palman Daejanggyeong (“Eighty-Thousand Tripiṭaka”) images showing flat surface of engraved characters on woodblocks [59,60].

Movable metal types are made by melting and casting metal for printing. These types are classified by type of metal or metal alloys used, such as copper, lead and iron. Traces of minor metals were usually used to make alloys with the main metal. The movable metal type was invented in the early 13th century during the mid Goryeo Dynasty, Korea [7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. There are several known traditional Korean movable metal typecasting methods: wax, sand and kaolin. Casting is done by pouring the molten substance into a mold to create the desired shape [13].

There is no record of exactly what type of metal casting methods were used during the Goryeo Dynasty. Joseon is known to have used the sand typecasting method at the National Foundry, Jujaso (鑄字所) from the founding of the Dynasty [13]. Few movable metal types from the Goryeo dynasty have been excavated in Gaeseong (開城), North Korea. Figure 14 shows two movable metal types of 㠅 and 嫥 from the Goryeo dynasty. They were made of copper alloys. The dimensions of the 㠅 character are 1 cm in width, 1.2 cm in height and 0.7 cm in thickness [61]. The 嫥 character has been excavated in 2015 [62]. A piece of metal type was unearthed at the site of Manwoldae (滿月臺) on 14 November 2015, a medieval royal palace of the Goryeo Kingdom (918–1392) in the North Korean border city of Gaeseong by a group of South and North Korean historians [63].

Figure 14.

Photographs of the sand type casted, from 13th century Goryeo metal type showing rough surface [59,60].

As seen in Figure 14, the surface of metal movable types was rough and uneven. They seemed to be sand casted. Other metal movable types from the 13th century of Goryeo dynasty also showed similar surface roughness [13]. The sand typecasting method seemed to be very popular at the time.

When metal movable type, with rough and uneven surfaces, were used for printing, non-uniform and uneven printing results are expected. In addition, oil containing light black ink, Yuyeonmuk (油煙墨), was used for metal type printing.

3.6. Ink Color and Printed Character Image Comparisons

To determine the printing technique for all six versions, cropped images of 15 characters (絶學無爲閑道人雲蹤鶴態何依抡春) and border lines in line 8 of page 3 (the front side of third folded leaf) in all six versions, before and after saturation, excluding inked areas were summarized in Figure 15. The printed characters from the A: Gongin version (空印本) was significantly lighter, uneven and non-uniform compared to the other five versions. It strongly suggests that the A: Gongin version (空印本) was printed using movable metal type. Ink color for the other five versions was darker. The printed characters of the five versions were also more continuous and uniform.

Figure 15.

Cropped images of 15 characters and border lines in line 8 of page 3 (the front side of third folded leaf) in all six versions, before and after saturation, excluding inked areas in different versions by image analysis. ((A) Gongin version (空印本), (B) Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), (C) Daegu version (大邱本) 1472, (D) Samseong version (三省本), (E) Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) 1526 and (F) National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本)).

To make the comparison easier, enlarged images of 15 characters from two versions, the A: Gongin version (空印本) and D: Samseong version (三省本), were summarized in Figure 16. It is very obvious that the printing characteristics of 15 characters in the two versions are characteristics of metal type print and woodblock print.

Figure 16.

Differences in printing characteristics of 15 characters in line 8 of page 3 (the front side of the third folded leaf). Spotty light-black printing of thin characters in metal-type-printed version and continuous dark-black printing of thick characters in the woodblock-printed version due to the differences in type of ink used and surface roughness of characters.

3.7. Microphotographs of Metal-Type-Printed Version

Microphotographs of hundreds of printed characters in the A: Gongin version (空印本) were taken for detailed observation of printing characteristics. Microphotographs were taken from the front side and backside of the paper. Digital microscope images of two characters (頌 and 殊) with 5 mm scale bars were summarized in Figure 17. Uneven and non-continuous printing of characters are very obvious. Debris on metal type, possibly casting defect, prohibited uniform and even printing. These types of printing characteristics were only seen from the A: Gongin version (空印本). This is one very strong evidence of metal type printing for the A: Gongin version (空印本). The metal casting originated defects described in Section 3.4 are also very powerful circumstantial evidence of metal type printing.

Figure 17.

Microphotographs of two printed characters (頌 and 殊) from the front and backside of paper of the metal-type-printed A: Gongin version (空印本). Uneven surface and metal casting defects of metal type caused imperfect printing of characters.

4. Discussion and Recommendations

4.1. Counterargument against Korean Historians’ Earlier Judgement

With all evidence described above, it is time to answer Korean historians’ earlier judgment on the printing template, printing sequence and the role of names printed at the bottom of all folded leaves of the A: Gongin version (空印本) of The Song of Enlightenment.

Korean historians’ claims:

- (i)

- It is identical to the D: Samseong version (三省本);

- (ii)

- Paper and printing quality is poorer than for the D: Samseong version (三省本);

- (iii)

- There are eleven names of craftsmen (possibly woodblock engravers) printed at the bottom of the folded leaves.

The author’s counterarguments:

- (i)

- The shape and inked areas of individual characters of the versions A to D looked identical in low resolution images or inspection by the naked eye (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5). Detailed image comparisons, inked area measurement and statistical analysis showed significant difference among all versions (Figure 1, Table 1, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12). The A: Gongin version (空印本) shows more than 50 metal-casting originated defects which cannot be seen from any other versions.

- (ii)

- Paper quality depends on paper making materials and process. Paper quality varies a lot between batches, craftsmen and the time of the paper making. Printing quality also varies by printing technique. At the early stage of metal type printing in the 13th century, printing techniques were not mature and cannot be simply compared with already mature woodblock printing techniques. The D: Samseong version (三省本) was printed in the 15th century after 1472.

- (iii)

- The names do not belong to woodblock engravers. Since all versions were identified to be different versions and the C: Daegu version (大邱本) was printed in 1472 and still carries the exact same names, they cannot be the woodblock engravers’ names. No woodblock engravers can live and actively for 233 years, from 1239 to 1472. The names possibly belonged to proofreaders at the time of typesetting of metal types in 1239. Woodblock engravers for the versions B: Banyasa Temple version (般若寺本), C: Daegu version (大邱本) and D: Samseong version (三省本) simply engraved the upside-down copy of a printed version on woodblocks. The names were omitted in the E: Jongno Public Library version (鍾路圖書館本) and F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本).

Based on four years of thorough investigation of six very similar or nearly identical versions of The Song of Enlightenment (南明泉和尙頌證道歌), the author is confident in claiming that the A: Gongin version (空印本) was the world’s oldest metal-type-printed book in the Goryeo dynasty of Korea in 1239. For image comparisons and analyses, a specially developed image analysis software (PicMan) was used. Individual characters, line-by-line, page-by-page comparisons and analyses among all six versions made statistics-based determination possible, to avoid subjective judgment based on impressions.

With a variety of evidence of the A: Gongin version (空印本) of The Song of Enlightenment for the metal type printing in 1239, we should revisit Choi Yi’s postscript, shown below, again.

“夫南明證道歌者實禪門之樞要也故後學叅禪之流莫不由斯而入升堂覩奧矣然則其可閇塞而不傳通乎於是募工重彫鑄字本以壽其傳焉時己亥九月上旬中書令晉陽公崔 怡 謹誌”

Korean historians were focused in one specific Chinese character 彫 (meaning: carve or engrave) in the 9-character phrase “於是募工重彫鑄字本” to interpret the true intension of Choi Yi, approximately 800 years ago in September 1239. In the phrase, there were metal type related word combinations such as 鑄字 (metal casted type) or 鑄字本 (metal-type-printed book or mold for metal type casting). However, they were interpreting the phrase to fit to their findings of woodblock-printed versions of the F: National Library of Korea version (國立中央圖書館本) and D: Samseong version (三省本). Furthermore, they not only wanted, but insisted, to apply their theories to all other versions, including the A: Gongin version (空印本) by ignoring the characteristics of metal-type-printed book. It was an inconvenient truth for them. This made them hinder any publication against their theory in Korea for almost 50 years. No one outside Korea would have any idea on what was going on. Everyone in Korea was intoxicated from the success story of Jikji being recognized by UNESCO as the oldest extant metal-type-printed book.

With all evidence of metal type printing in the A: Gongin version (空印本) of The Song of Enlightenment, Choi Yi’s true intention of postscript becomes very clear. He wrote the postscript to celebrate the birth of the world’s first metal-type-printed Buddhist text.

4.2. Recommendations

As historians around the world investigated the history of printing, paper making, printing press and the spread of technology in ancient times, for more than 100 years, it is important to find out and understand the true history of science and technology [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,17,18,19,20,21,22,55,56]. As we learn about things and discover new facts, we have to integrate that knowledge to revise our understanding. If we decide not to look for new facts or intentionally ignore them for their own sake, we cannot learn anything from history, which is shameful. A healthy academic society should not only allow, but encourage, voices of different opinions and active debates.

As described in a series of reports, there have been claims that the Gongin version (空印本) of The Song of Enlightenment is the world’s oldest surviving movable metal-type-printed version from September 1239, during the Goryeo dynasty of Korea. The claim has been consistently raised over the past 50 years, since the 1970s [25,26,27,36,37,46,48,49]. The author has tried to raise this claim in Korea by publishing articles and discussions at conferences, but eight consecutive rejections of manuscripts, due to extremely negative comments from a specific group of reviewers, is the current record [64,65,66,67]. The author has no plans or reasons to give up. It is a perfect time to seriously re-evaluate this claim without prejudice. Historical background information, new evidence and vast amounts of image comparisons, analyses and results introduced in the author’s previous reports, plus this study, should be very useful for objective evaluation. With the author’s continuous appeal and further discussions with Korean historians and conservation scientists, a manuscript has finally been accepted for publication [68,69]. The research results have been heavily covered in newspapers in Korea [64,65,66,67]. Many historians, bibliographers and conservation scientists expressed their interest on this very exciting subject.

The author would like to strongly urge historians around the world to again look closely at the ancient book, Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (南明泉和尙頌證道歌; The Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon). “The Song of Enlightenment” was designated as Korean Treasure No. 758-2 (A: Gongin version (空印本) in this paper) on 29 June 2012 [29]. It has already been recognized as a valuable documentary cultural property in Korea. This version is most likely the world’s oldest surviving movable metal-type-printed book from September 1239 and is a great candidate for the UNESCO Memory of the World program.

In the collaborative research project “From Jikji to Gutenberg”, a group of international researchers have started to investigate the technological evidence related to the invention of book printing [24]. The interdisciplinary team is to study what appears to be independent developments that lead to thriving print cultures from Eastern Asia to Western Europe in the 14th to 15th centuries, as other historians have mentioned previously [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Any findings from the six versions of The Song of Enlightenment adds to our insight into the evolution of printing techniques and practices in Korea from the 13th to 16th centuries and propagation of newly developed technology around the world. The invention and usage of metal movable type to facilitate our understanding and preservation of important histories of technology and of mankind can be achieved through unbiased investigation. A truly impactful contribution from long ago can be gained and documented.

It is worthwhile to commemorate the 650th anniversary of the printing of Jikji in July 2027. More importantly, we should not forget, or leave out, any potential documentary cultural heritage of great interest due to preferences of individuals or research groups. The appearance of older versions and recognition of their value only enrich the history of mankind.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank his colleagues, Jung Gon Kim and Kitaek Kang, and James Schram of WaferMasters, Inc. for their understanding and support during this very exciting cultural heritage image analysis and evaluation project. He is also thankful to Jae Seug Yun and Kwon Hee Nam of Kyungpook National University, Daegu, Korea, Yun Pyo Hong of Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, Tae-Ho Choi of Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea and Jae-Young Chung of KOREATECH (Korea University of Technology and Education), Cheonan, Korea for their introduction and study materials on this very topic. He is also thankful to the collector and Buddhist Monk Won-Jin, Yangsan, Korea for providing the opportunity to inspect the C: Gongin version (空印本) of The Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong Cheon (南明泉和尙頌證道歌) multiple times upon request. He also would like to thank Sang Keun Lee, Chairman of the Cultural Heritage Restoration Foundation, Seoul, Korea for his interest, encouragement and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Edge Foundation. 1999: What is the Most Important Invention in the Past Two Thousand Years? Available online: https://www.edge.org/annual-question/what-is-the-most-important-invention-in-the-past-two-thousand-years (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Gormley, L. The Greatest Inventions in The Past 1000 Years. Available online: https://ehistory.osu.edu/articles/greatest-inventions-past-1000-years (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Hunter, D. Paper Making: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft; Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1943; Chapters 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gunarantne, S.A. Paper, Printing and The Printing Press: A Horizontally Integrative Macrohistory Analysis. SAGE J. 2001, 63, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, T.F. The Invention of Printing in China and Its Spread Westward; Part IV; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Laufer, B. Reviews of Books: The Invention of Printing in China and Its Spread Westward by Thomas Francis Carter; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1925; Available online: https://www.ghazali.org/articles/jaos-47-bl-r.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Sohn, P.-K. Early Korean Printing. J. Am. Orient. Soc. 1959, 79, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, P.K. Early Korean Typography; Korean Library Studies Association: Seoul, Korea, 1971. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Chon, H.B. 200 Years before Gutenberg: The Master Printers of Koryo. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/courier/december-1978/200-years-gutenberg-master-printers-koryo (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Cheon, H.B. The World’s First Invention, Metal Type Printing in Goryeo Dynasty (高麗鑄字印刷). Gyujanggak 1984, 8, 63–75. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002632708 (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean with English Abstract).

- Newman, M.S. The Buddhist History of Moveable Type—Forget Johannes Gutenberg. The First Person to Ever Make a Book Printed with Moveable Metal Type was Named Choe Yun-ui. 2016. Available online: https://tricycle.org/magazine/buddhist-history-moveable-type/ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Wikipedia. Movable Type. Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Movable_type#Europe (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Ok, Y.J. Early Printings in Korea; The Academy of Korean Studies Press: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos, I. Translating Chinese Tradition and Teaching Tangut Culture; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J. 史金波. Xixia Fojiao Shilüe (西夏佛教史略); Ningxia Renmin Chubanshe: Yinchuan, China, 1988; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, C. Woodblock Printing. Available online: https://msutexas.edu/library/departments/nolan-moore-iii/case-2.php (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Yan, K. The Importance of Chinese Woodblock Printing: What Was Chinese Woodblock Printing Like in Early Modern East Asia? Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/96780ec4dddf47c786dfac1154a3f196 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Hang, L.T.; Van, V.H. Method of Printing Carved on Wood under the Nguyen Dynasty of Vietnam: Study of Woodblocks Recognized by UNESCO as a World Documentary Heritage. Int. J. Psychosoc. Rehabil. 2020, 24, 2701–2708. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Memory of the World. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/programme/mow (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- UNESCO. MOW JIKJI Prize. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/prizes/jikji-mow-prize (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- BnF (The Bibliothèque Nationale de France), 2022, “백운화상초록불조직지심체요절. 白雲和尙抄錄佛祖直指心體要節 Päk un (1298–1374). Auteur du Texte”. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10527116j.image (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Mohamed, S. “JIKJI”, the Oldest Printed Book. Available online: https://www.politics-dz.com/en/jikji-the-oldest-printed-book/ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- UNESCO. Epistola Hieronymi—Bd./Vol. 1—fol. 001r. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/mediabank/24944/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- The University of Utah. From Jikji to Gutenberg. Available online: https://jikji.utah.edu/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Yoo, W.S.; Kim, J.G. Comparative Study on Very Similar Jeungdoga Scripts through Image Analysis—Fundamental Difference between Treasure No. 758-1 and Treasure No. 758-2. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37, 791–800, (In Korean with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S. The World’s Oldest Book Printed by Movable Metal Type in Korea in 1239: The Song of Enlightenment. Heritage 2022, 5, 1089–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S. How Was the World’s Oldest Metal-Type-Printed Book (The Song of Enlightenment, Korea, 1239) Misidentified for Nearly 50 Years? Heritage 2022, 5, 1779–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultural Heritage Administration (Korea). Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong). Available online: http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do?pageNo=1_1_2_0&ccbaCpno=1121107580000 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Cultural Heritage Administration (Korea). Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong). Available online: http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do?ccbaCpno=1123807580200 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Cultural Heritage Administration (Korea). Nammyeong Cheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga (Song of Enlightenment with Commentaries by Buddhist Monk Nammyeong). Available online: http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/culSelectDetail.do;jsessionid=EsDv0h414RnB79FYIGRzGm9UWRDBBzDT3FXGSlDsZDu0AlJAJxx3m8rIvbk6Iu95.cpawas_servlet_engine1?culPageNo=35®ion=&searchCondition=&searchCondition2=&s_kdcd=&s_ctcd=11&ccbaKdcd=21&ccbaAsno=04840000&ccbaCtcd=11&ccbaCpno=2111104840000&ccbaCndt=&ccbaLcto=11&stCcbaAsno=&endCcbaAsno=&stCcbaAsdt=&endCcbaAsdt=&ccbaPcd1=&chGubun=&header=region&returnUrl=%2Fheri%2Fcul%2FculSelectRegionList.do&pageNo=1_1_3_1&sngl=Y (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Amitofo3 TV. Yongjia Dàshı Zhèng Dào Ge 永嘉大師證道歌: Master Yongjia’s Song of Enlightenment. Available online: http://www.amitofo3.net/books/b083.html (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- The Matheson Trust. The Song of Enlightenment. Available online: https://www.themathesontrust.org/library/cheng-dao-ke (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Fotozhengfa. Cheng-Tao-Ko. Available online: https://fotuozhengfa.com/archives/35352 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Pacific Zen Institute. Song of Enlightenment—Yongjia Xuanjue. Available online: https://www.pacificzen.org/library/ceremonies-long-readings-for-afternoon-song-of-enlightenment-yongjia-xuanjue/ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- The Matheson Trust. The Song That Attests to the Way. Available online: https://www.themathesontrust.org/papers/buddhism/shasta-song.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Park, S.K. Nammyeong Jeungdoga, the World’s First Metal Type Print; Gymmyoung Publishers: Seoul, Korea, 2020. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.K. Nammyeongcheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga [Birth of the World’s First Metal Type Print]; Gymmyoung Publishers: Seoul, Korea, 2020. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, P.K. Presentation Summary (1972–1978)—Discussion [Korean Metal Types (金屬活字)]: Aspects of Cultural History. Korean J. Hist. Sci. 1979, 1, 73. Available online: http://www.khss.or.kr/index.php?mid=kjhs&category=187&document_srl=414 (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean).

- Cheon, H.B. Presentation Summary (1972–1978)—Discussion [Korean Metal Types (金屬活字)]: A Bibliographical Aspect. Korean J. Hist. Sci. 1979, 1, 73–74. Available online: http://www.khss.or.kr/index.php?mid=kjhs&category=187&document_srl=416 (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean).

- Cheon, H.B. On the Recarved Edition of Priest Nanmingchuan’s Chengtao-ko, Printed with Metal Type in the Koryo Dynasty. J. Korean Libr. Sci. Soc. 1988, 15, 267–280. Available online: https://scienceon.kisti.re.kr/srch/selectPORSrchArticle.do?cn=JAKO198825720296247&dbt=NART (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean with English Abstract).

- Wikipedia. Song of Enlightenment. Available online: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_of_Enlightenment (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- The Dong-A Ilbo. Jeungdoga of Goryeo Dynasty, Designated as a Korean Treasure, Revealed in a Joseon Dynasty Version. 2016. Available online: https://www.donga.com/news/Culture/article/all/20160129/76197418/1 (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean).

- Song, I.G.; Park, J.S. A Bibliographical Study on the Buddhist Scriptures Published in Temples Located in Hwanghae-do Province. Korean Soc. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2016, 50, 395–416, (In Korean with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kyunghyang Shinmun. 3 Types of Old Books Owned by Jongno Library, Designated as a Tangible Cultural Property by the Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2021. Available online: https://m.khan.co.kr/national/education/article/202103111201001#c2b (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean).

- Shin, J.Y. Analysis of the Engraving of Metal Type Re-engraved Version in the Early Joseon Dynasty—Focusing on the re-engraved version of Jinseosandokseogieuljipsangdaehakyeoneui-. J. Korean Soc. Bibliogr. 2021, 86, 167–192. Available online: https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/landing/article.kci?arti_id=ART002727089#none (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean with English Abstract).

- Park, D.S. Goryeo Metal-Type Printing, ‘Nammyeongcheon Hwasangsong Jeungdoga’; (Hyangto Andong) Society for the Study of Local History of Andong: Andong, Korea, 1988; Volume 1, pp. 15–192. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Haeinsa Temple Janggyeong Panjeon, the Depositories for the Tripitaka Koreana Woodblocks. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/737/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- BTN News. “First Confirmation that Nammyungjeungdoga of Samseong-Version and Gongin-Version are Different”. A Korean-American Scholar Published a Research Paper in the Latest Issue of the Journal of Conservation Science. Overturning the Judgment of the Cultural Heritage Committee. Available online: https://www.btnnews.tv/news/articleView.html?idxno=69828 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- BTN News. Gongin Version Predates Samsung Version of The Song of Enlightenment. 2022. Available online: http://www.btnnews.tv/news/articleView.html?idxno=71808 (accessed on 25 June 2022). (In Korean).

- Yoo, Y.; Yoo, W.S. Digital Image Comparisons for Investigating Aging Effects and Artificial Modifications Using Image Analysis Software. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S.; Kim, J.G.; Ahn, E.J. An Experimental Study on the Printing Characteristics of Traditional Korean Paper (Hanji) Using a Replicated Woodblock of Wanpanbon Edition Shimcheongjeon. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37, 289–301, (In Korean with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S.; Kim, J.G.; Ahn, E.J. An Experimental Reproduction Study on Characteristics of Woodblock Printing on Traditional Korean Paper (Hanji). J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 37, 579–689, (In Korean with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S. Comparison of Outlines by Image Analysis for Derivation of Objective Validation Results: “Ito Hirobumi’s Characters on the Foundation Stone” of the Main Building of Bank of Korea. J. Conserv. Sci. 2020, 36, 511–518, (In Korean with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Kim, J.G.; Kang, K.; Yoo, W.S. Image-Based Quantitative Analysis of Foxing Stains on Old Printed Paper Documents. Heritage 2019, 2, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.S.; Kim, J.G.; Kang, K.; Yoo, Y. Extraction of Colour Information from Digital Images Towards Cultural Heritage Characterisation Applications. SPAFA J. 2021, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Image Analysis Program Manual for Diagnosis of Conservation Status of Painting Cultural Heritage; Konkuk University and National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage (Korea): Daejeon, Korea, 2022; ISBN 978-89-299-2570-3. (In Korean)

- Park, H.O. The History of Pre-Gutenberg Woodblock and Movable Type Printing in Korea. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cultural Heritage Administration (Korea). Memory of the World. Available online: http://english.cha.go.kr/cop/bbs/selectBoardList.do?bbsId=BBSMSTR_1205&uniq=0&mn=EN_03_03&ctgryLrcls=CTGRY211 (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Cultural Heritage Administration (Korea). Printing Woodblocks of the Tripitaka Koreana in Haeinsa Temple, Hapcheon (합천 해인사 대장경판 (陜川 海印寺 大藏經板)). Available online: http://www.heritage.go.kr/heri/cul/imgHeritage.do?ccimId=1613003&ccbaKdcd=11&ccbaAsno=00320000&ccbaCtcd=38 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Sisa Journal. Preview of Daejanggyeong World Culture Festival at Haeinsa Temple in Hapcheon (미리 찾아가 본 합천 해인사 대장경세계문화축전). Available online: https://www.sisajournal.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=171652 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- National Museum of Korea, Goryeo Metal Type (고려 금속활자). Available online: https://www.museum.go.kr/site/main/relic/search/view?relicId=1348 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Woori Culture Newspaper (우리 문화신문). Excavation of Metal Movable type from the Goryeo Dynasty at Manwoldae in Gaeseong (개성 만월대서 고려시대 금속활자 발굴). Available online: https://www.koya-culture.com/mobile/article.html?no=101833 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- The Korea Times. Ancient Metal Type Unearthed at Gaeseong’s Manwoldae. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/culture/2021/05/135_192179.html (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Yeongnam Ilbo. Kyungpook National University Dr. Woo Sik Yoo, Identified the World’s Best Printed Metal Type ‘Nammyeongcheon Hwasangsongjeungdoga’. Available online: https://www.yeongnam.com/web/view.php?key=20220818010002253 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Munhwa Ilbo. Scientific Proof that ‘Nammyung Jeungdoga’, the Oldest Metal Type in the World, is Older Than ‘Jikji’. Available online: http://www.munhwa.com/news/view.html?no=2022081901031027106001 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- The Korea Herald. [Visual History of Korea] Jeungdoga Book May be Oldest Movable Metal Type Print Book. Available online: https://m.koreaherald.com/amp/view.php?ud=20221028000652 (accessed on 31 October 2022).