Abstract

Intangible Culture Heritage (ICH) is defined as the collection of oral traditions and expressions such as epics, fairy tales, stories, arts, social practices, rituals and celebrations, events, knowledge, and practices related to nature and the universe, traditional medicine, folk medicine, traditional handcrafts, as well as personal experiences related to important historical events or cultural activities that shaped the historical and local identity. Under the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the ICH, nations are committed to developing inventories of ICH and working with local communities, groups, and individuals to preserve these traditions. In this paper, a platform is introduced that facilitates the collection of intangible ICH data, the formation of story-based narratives, and their presentation to the public via a web and mobile application, which offers Augmented Reality (AR) experiences. The platform aims to support the formation of user communities sharing common interests and to provide them with the appropriate tools for collecting pieces of ICH. Collected ICH resources and created narratives are modeled using semantic web technologies so that information can be perceived by third-party systems too. Furthermore, towards the dissemination of the platform, a real-world use case took place on the island of Rhodes focusing on the recent history of the island between 1912 and 1948 (WWII). The platform was implemented to support the goals of the project InCulture, funded by the EPAnEK Greek national co-funded operational program “Competitiveness Entrepreneurship and Innovation”.

1. Introduction

According to UNESCO, the intangible dimension of Cultural Heritage (CH) includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge, and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts. While fragile, ICH is an important factor in maintaining cultural diversity in the face of growing globalization. An understanding of ICH in different communities helps with intercultural dialogue and encourages mutual respect for other ways of life [1,2].

The approach presented in this paper addresses both the formation of story-based narratives through user communities and content exploration from the Web and/or on the go. To do so, an online platform [3] is introduced as a result of the project, “InCulture: Collection, representation and presentation of ICH” [4].

In this context, this research work introduces a new solution for collaborative authoring of story-based ICH narratives aiming to support the collection of pieces of information relevant to the recent history of the island of Rhodes (Greece). A representation model for ICH narratives is shaped to support the production of narratives that combine and correlate textual content with multimedia. The representation model is based on a CH domain standard, the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model (CRM) [5].

Furthermore, InCulture unleashes the power of user communities by supporting their formation and offering collaborative features. Tools for resource capturing are also made available to facilitate content collection on the spot. The ICH information collected and narratives formed are made available through a web and a mobile application, offering AR experiences, by exploiting the location metadata of the available resources.

The combination of (i) easy-to-use tools for ICH resources collection via mobile devices, (ii) semantic web representation of collected data, (iii) real-time collaborative tools for authoring of narratives and (iv) novel user interfaces presenting the collected ICH content makes InCulture a unique solution for the ICH domain. InCulture aims to democratize ICH content crafting and access.

2. Related Work

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a narrative is defined as “an account of a series of events, facts, etc., given in order and with the establishing of connections between them.” [6]. The study of the concept of a narrative goes back to Aristotle [7], further elaborated by many philosophers afterwards. A more systematic study of the narrative structure was conducted by Russian formalists [8], giving rise to narratology.

2.1. Semantic Models for CH

Today, semantic web technologies are considered an integral part of digital CH [9]. In this context, the pioneering work of Europeana stands out for making the representation of CH artifacts with semantic technologies possible [10]. The evolution of such technologies can be considered to have occurred in three phases, as described below.

The first phase was rooted in knowledge classification approaches as applied to libraries and archives powering object-centric approaches such as MINERVA [11] and Europeana Rhine [12]. In this phase, Digital Libraries (DLs), especially in the Cultural Heritage domain, are considered to be rich in narratives, since every digital object in a DL tells some kind of story, regardless of the medium, the genre, or the type of object. However, in the first phase, DLs didn’t offer services about narratives but rather only discovered functionalities over their contents, without regard for the narratives themselves [13].

The second phase was empowered by the representation of events as proposed by CIDOC CRM [5]. The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model is standard used worldwide for the storage and codification of cultural information, providing a formal structure for common relationships and attributes regarded in cultural heritage documentation, such as the births of important figures and the constructions of monuments. An example of its manifestation was the integration of the basic “Event” class to the Europeana Data Model [10]. The introduction of the class “Event” led to significant improvements, mainly for the obvious reason that it made possible the representation of events but also due to the inherited attribute of connecting these events with object-centric representations. With this breakthrough it was made possible to represent series of events, each one connected with instances that, when put together, can represent the backbone of a story. For example, a building acquisition transaction is an event happening sometime in the past. The factory is a manmade object linked with digital assets (e.g., photographic documentation of the building, 3D scans, etc.) designed by an architect (e.g., a person). Furthermore, the transaction has participants which are, for example, the owner and the buyer, and takes place in a specific location which is represented with geo-coordinates.

Recent work on the third phase focuses on the semantic representation of narratives [14,15] and has implemented such an ontology as an extension of three standard vocabularies, i.e., the CIDOC-CRM [5], FRBRoo [16], and OWL Time [17], and using the SWRL [18] rule language to express the axioms. Furthermore, the following contents of a narrative were defined by the Russian formalists [8]: (a) the fabula representing the story itself as it happened, (b) the narrations, that represent one or more expressions of the fabula, and (c) the plot, which is the way that narration is narrated. This work was further extended to support the representation of the tangible and intangible dimensions of traditional crafts and their interconnection with the socio-historic context of the community practicing them [19].

The work presented in this paper aspires to be part of the third phase by introducing narrative-centric representations. The work builds on the CIDOC CRM [5] but simplifies the structure of a narrative, thus reducing the effort of narrative authoring in close relation to the production of an easy-to-use and intuitive web-based user interface.

2.2. Participatory Narrative Authoring Systems

The importance of narratives for the representation and presentation of social and historic context has been recently identified. Since narratives are by themselves a manifestation of ICH, the earliest attempt for its representation online can be considered the i-Treasures web platform, which was an open and extendable platform providing access to intangible heritage data of different formats. Although i-Treasures did not work on the formalization of narratives, it offered different forms of disseminating ICH data such as MoCap of dance [20].

The Mingei Online Platform (MOP) is probably the latest attempt to support collaborative authoring from multiple knowledge curators of semantic descriptions on the socio-historic context, grouped together under the formalized description of a semantic narrative [21,22]. The MOP has been also recently extended to represent recipes expressed both as a process and as narratives [23]. The formalization of the narrative itself is facilitated in MOP by previous research efforts in the domain, where the term of semantic narratives was introduced as a way of giving “meaning” to digital content [15]. Furthermore, due to the evolution of the technical means for documenting cultural resources, various digital forms of information have been integrated to such systems, including multimodal digitization and online sources such as Wikidata [24,25], thus allowing data curators to enhance their representations through open linked data. The authoring process of the above-mentioned narratives has been systematized in the form of a step-by-step approach [26]. Finally, recent approaches have expanded the applicability of narratives for CH objects and sites by supporting the collaborative authoring of narratives that could be narrated in conjunction with (a) the geographical context [27,28], (b) an artifact [29], (c) a museum collection [30,31,32], etc. Last but not least, to ensure compatibility with open linked data repositories, attempts have been made toward harmonizing the representation of narratives with open linked data repositories such as the Europeana [33].

2.3. Approach and Contribution

While several solutions exist that try to address ICH preservation through model representations, they fall short on engaging the end-users to participate actively in the collection of ICH resources and on the presentation of the available content. This work contributes a versatile solution that offers a unique combination of features for ICH resource collection, organization, preservation, presentation, and promotion. Specifically, the InCulture platform presented in this paper introduces a mobile application featuring multimedia resource capturing and uploading, towards enabling crowd-sourced collection of content via a mobile-friendly, easy-to-use way. Further, the platform facilitates the formation of user communities that share common interests in regards to ICH, and provides tools for collaborative authoring of story-based narratives. The authored narratives are presented both on a web interface as well as a mobile application that features location-based AR experiences for context-aware content exploration. Finally, the InCulture framework proposes a formal representation model, which is based on and extends the CIDOC CRM [5], a well-established ontology for CH resources.

3. User Requirements Specification

For this work, the elicitation of user requirements was achieved through a series of interviews and questionnaires of the target user groups. The respondents were asked to imagine a system/platform and what they would like from it, instead of evaluating an existing and tested one. Some of the concepts discussed during the requirements elicitation phase are listed below:

- How is the term “ICH” perceived?

- What forms of ICH resources would they expect to find and study on an online web platform?

- When and in what ways is collaborative creation of resources and narratives better than individual contributions?

- In what way should the available resources be offered and what tools do they imagine being provided to content creators?

The above-mentioned concepts were discussed during thirteen (13) structured, face-to-face interviews that took place in public areas with randomly selected individuals. In addition, fifty (50) individuals filled in an online questionnaire, which was promoted on social media pages.

The results from the interviews and questionnaires confirmed the interest of the public around ICH and pointed out the ICH categories about which the users would be most interested to read or most willing to contribute content, such as (i) personal stories and local history, (ii) local traditions, (iii) local gastronomy, (iv) festivities, and more. In regard to collaborative authoring, the results revealed that users prefer working in user groups (81%) instead of working alone (19%). Moreover, interviewees specified that users within a collaborative group could provide supplementary material (42%), validate the content (30%), exchange ideas (19%), or just distribute the work (9%).

In regard to content creation, results showed that creators would expect such a platform to automatically generate metadata from provided content (e.g., geographic location), accommodate custom tags for content, feature a spellchecker for textual content, provide sharing functionality for social media, refer to external or internal sources, and more. The results also revealed that users would feel more comfortable with contributing if a moderation policy was enforced before the content was published.

Finally, in regard to content presentation, the results showed that users would expect an appealing graphical user-interface that can be accessed both on desktop and mobile devices. Moreover, such a platform would benefit from social interactions with features like an integrated commenting mechanism.

3.1. User Roles

Towards defining specific use cases and application scenarios, it was required to identify the representative user roles, according to the scope of the system and the results from the interviews and questionnaires. In this direction, user roles are derived according to the expected functionality as follows:

- Visitor: Represents the users that can browse, view and provide feedback for content on the InCulture platform.

- Creator: Refers to the authorized users who contribute with content by uploading and creating ICH resources. Creators can participate in user communities and work on collaborative authoring.

- Community moderator: Represents users responsible for maintaining and coordinating a user community. Community moderators accept or reject members, assign tasks and moderate discussions at a community level.

- Scientific Committee member: Refers to domain experts responsible for the content published by the InCulture platform.

- Administrator: Refers to users in charge of maintaining the platform by adjusting system configurations and assigning user roles.

User roles are created on top of each other in layers, thus each one extends the role on top. For example, a user with the creator role is also a visitor, a community moderator is also a creator and so on. Each user can only have one role attached at each time.

3.2. Use Cases

Use cases are indicative solutions and representations of the contract between the stakeholders and the system’s behavior. They enable developers to understand and design software systems and platforms as artifacts of human activity, tools to use in one’s work, or as media for interacting with other people [34]. InCulture deploys a total of thirty-three (33) use cases grouped under three (3) main categories, which are briefly described in the following sections: (a) content exploring, (b) individual and collaborative content creation, and (c) users and communities management. A summary of these use cases is presented below.

3.2.1. Content Exploring

The InCulture platform aims to host, preserve, and present pieces of ICH to visitors. Accordingly, use cases grouped under the content exploring category describe functionalities associated with the visitor role. Use cases under this group describe the interactions of the visitor with the content, e.g., viewing, writing comments, adding likes, etc. In brief, visitors should be able to:

- view published narratives

- view ICH resources

- explore narratives using AR views

- perform searches for content

- add comments and/or likes to a content entry

3.2.2. Individual and Collaborative Content Creation

In addition to content presentation, the InCulture platform aims to support the role of the users as content creators. According to this, users with the role of creator are provided with tools to capture, collect, and upload content to the platform, as well as features to allow the collaborative authoring of narratives. Specifically, creators should be able to:

- upload single ICH resources

- create and edit ICH resources using an easy-to-use content editor

- attach multimedia files to an ICH resource

- provide metadata to ICH resources

- create and edit parts of narratives by referring to existing ICH resources or adding custom content

- collaborate on narratives and exchange messages via message boards with members of the same community

3.2.3. Communities Moderation

One of the novelties introduced by the InCulture platform is the online formation of narratives through active collaboration between members of user communities. Towards this, several use cases were defined to showcase the related features. In brief, community moderators should be able to:

- accept and reject join requests

- view lists of communities and details for each one

- modify the community details (title and description)

- view community members

- coordinate work and distribute tasks in regards to narratives authoring on a narrative specific message board

- lead discussions on a user community specific message board

3.2.4. Content Moderation

As the InCulture platform is based mostly on users’ contributions in a crowdsourcing form, there is a need for content moderation policies to be applied in order to maintain a complete and historically valid content base. To this end, a governance body called a scientific committee is introduced, consisting of appointed field experts that have absolute control over what can be published or not. Following the creation of an ICH resource or narrative, a scientific committee member has to review and approve it before publication (on webpage and mobile application). Specifically, members of the scientific committee should be able to:

- approve or reject content publication

- participate in discussions on narratives

- resolve conflicts related to content

3.2.5. System Administration

The appointment of scientific committee members and community moderators is fulfilled by general system administrators. Besides roles assignments, administrators have complete power over the user base, system settings, and content across the platform. Their actions can override every other action from users with a different role. In brief, system administrators should be able to:

- modify the platform’s settings, such as presentation details, text literals, etc.

- appoint community moderators and scientific committee members

- monitor the system’s health in regard to availability and performance

3.3. UI Design

Based on the findings of the requirement analysis and the specification of use cases, several design prototypes were implemented by User Interface (UI) designers in collaboration with User Experience (UX) experts. Prototyping helps stakeholders to develop a concrete sense regarding the application that is not yet implemented. Through visualization of the application, stakeholders can determine the requirements and workflow of the system. Further, prototyping reduces cost and time because errors are detected in the early stages, providing high levels of user satisfaction at the end.

3.3.1. UI Design Method Methodology

The design of the system was carried out in iterations following the principles of user-centered design, a design process in which designers focus on users and their needs throughout the process. According to user-centered design, users are included in all phases of the process through a range of research and design techniques to create useful and accessible products for them.

User-centered design is an approach to the software development process that focuses on the user rather than technology. The involvement of the end-users of the platform begins from the first stages of the design and continues until the end of the development. The method of iterative design and development is followed, which includes multiple evaluations by end-users at various stages of application design and development.

User-centered design is based on the use of techniques for communication, interaction, empathy, and encouragement of participants, to understand their needs, desires, and experiences. Thus, user-centered design is focused on the questions, ideas, and activities of the people for whom the product, system, or service is targeted, rather than on the creator’s creative process or the characteristics of the technology. As a result, following the process of user-centered design, the creation of easy-to-use and intuitive products, systems, and services is achieved [35].

More specifically, the human-centered design process is iterative, with a focus on the human being, and consists of four phases (Figure 1): (i) understanding and defining the context of use, (ii) defining user requirements, (iii) creating design solutions, and (iv) design evaluation [36].

Figure 1.

User-centered design process.

The benefits of the iterative design are that it involves user testing, thus providing valuable user feedback, and that it can identify problems early in the development life cycle, thus improving usability. All the above constitute iterative design, an efficient and cost-effective process for the development of UIs, ensuring a high-quality user experience.

3.3.2. Co-Design Workshops

Based on the functional requirements identified, two co-design workshops were held with 2 groups of 10 end users each, from which the initial design prototypes emerged. During the co-design workshops, the participants were initially introduced to the scope of the project in order to get them familiarized with ICH concepts and boost active participation. Following the briefing, a series of activities were coordinated by the workshop organizers, as described below:

- Post-it notes—Categories of Intangible Cultural Heritage: During this activity (Figure 2), participants were asked to note down and later grade categories of ICH.

Figure 2. Post-it notes—categories of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Figure 2. Post-it notes—categories of Intangible Cultural Heritage. - Key—moments of user experience: During this activity (Figure 3), participants were given a specific persona and were asked to visualize a usage scenario in order to achieve a predefined goal. At the end of this activity all solutions were discussed among participants.

Figure 3. Key moments of the user experience.

Figure 3. Key moments of the user experience. - Voting—Pros and Cons of user communities: During this activity, participants were presented with the notion of user communities and were asked to note down ideas for user collaboration and vote for some predefined features as pros or cons.

Based on the results of the collaborative design workshops, a first version of high-fidelity prototypes was designed, which included the basic functionality of the system, both for desktop computers and mobile devices. These prototypes were then evaluated by usability experts, following the heuristic evaluation method. Later, the same prototypes were also evaluated by representative end-users. The prototypes were modified based on the evaluation results, resulting in the final application design (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The homepage of the InCulture web application.

4. System Architecture

The InCulture platform aims to support multimedia narratives that are implemented as a combination of web-based technologies and a standalone mobile application that features on-the-go content exploration and delivers AR experiences. The functional architecture of the InCulture platform, presented in this section (Figure 5), describes the fundamental architectural components.

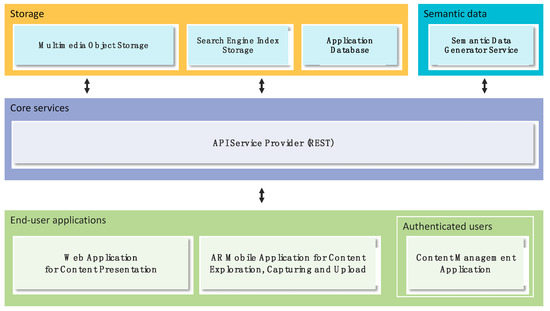

Figure 5.

Functional architecture of the InCulture system.

4.1. End-User Applications

The InCulture platform aims to acquire, preserve, and present ΙCH content in the form of narratives, which are captured and uploaded to the system by users. End-user applications, offered as a website and a standalone mobile application, have a significant role in the success of the platform, as they are the tools via which users interact with the system. Within the InCulture platform, three applications are created, each of which focuses on a specific range of overall functionality, namely the public content presentation website, the content exploration mobile application offering capturing tools, and the online content management application.

4.1.1. Web Application for Content Presentation

The web application for content presentation includes a series of graphical user interfaces to facilitate the discovery, browsing, and viewing of the available ICH content by end-users. The homepage (Figure 4) aims, on the one hand, to present to the user the topic of the page (i.e., ICH), and on the other hand, to promote featured content. A number of narratives are selected by the system administrators to be featured on the homepage.

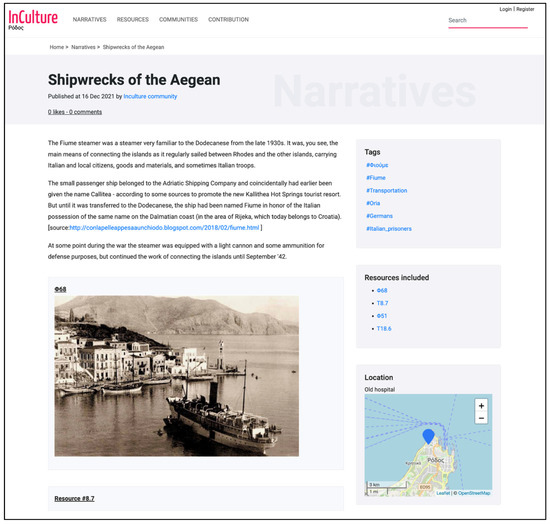

Since narratives are a fundamental element of the InCulture platform, their visualization is of significant importance. A narrative consists of one or more ICH entries, accompanied by multiple texts and multimedia elements, to form a longer, added-value story (Figure 6). The ICH resources included in a narrative aim to support the story with facts/evidence. They can either be referenced by their title and a corresponding link or be included as is (full content). The authors of the narrative have full control in regard to the final structure of the narrative.

Figure 6.

Single narrative view.

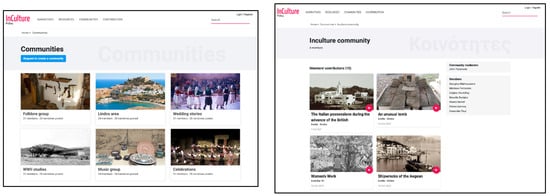

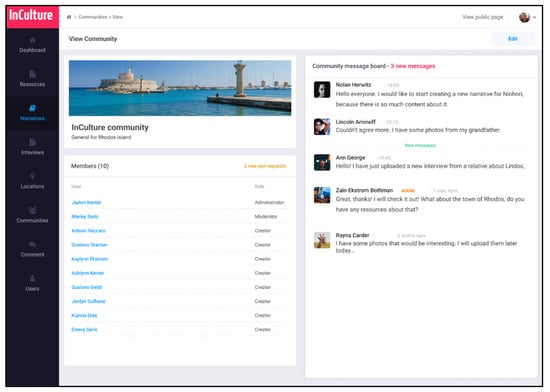

InCulture is a collaboration platform that promotes the formation of user communities. Users that share common interests can become members of a community and work together towards collecting pieces of ICH and creating narratives. Communities (Figure 7) are visible to the public and any registered user can apply to become a member.

Figure 7.

(left) Communities list, (right) detailed view of a community.

The web application retrieves and posts data via a defined REST API supported by the API service provider. It is implemented using Angular [37], an open-source framework for web applications, supported by Google and a large community of contributors. Frameworks such as Angular support the development of complex single-page applications by providing mechanisms for managing and presenting the data arriving from the data provider.

4.1.2. AR Mobile Application for Content Exploration, Capturing, and Upload

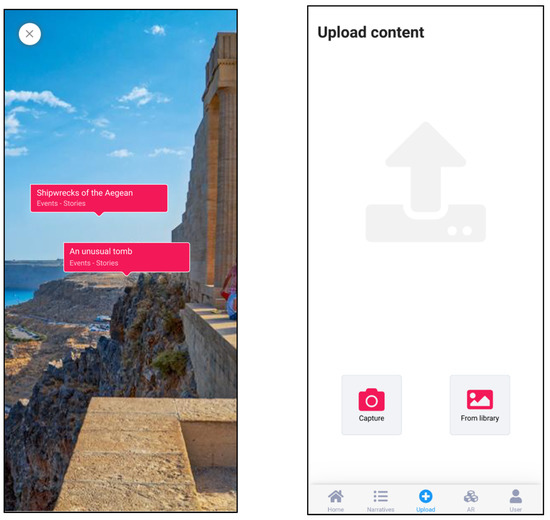

The use of mobile applications is increasingly common, and users have high expectations of these applications, in terms of how easy they are to use and how quickly content is loaded on them (i.e., performance). However, designing for mobile devices is a very demanding process because of the smaller screen sizes. Consequently, several parameters must be taken into account (e.g., minimizing the cognitive load, removing unnecessary visual elements, easy navigation, etc.) while designing mobile applications so that the content is presented in the best way. Thus, although the web application is designed to have a responsive layout (support multiple screen resolutions), a complementary mobile app is implemented to offer a clean, mobile-centric design (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Mobile application (left) home screen, (right) single narrative presentation screen.

Additionally, the mobile application features a location-based AR view (Figure 9 left), where narratives appear in the real world through the user’s mobile device. To achieve this, the application exploits the location metadata of narrative entries and the sensors of the mobile device (GPS, gyroscope, compass) in order to draw a real-time visual representation of them on the screen. The graphical elements are displayed in such a way that the nearest is at the top of the projection stack, while the farthest is placed behind it with a smaller size.

Figure 9.

AR view (left), content capture and upload screen (right).

Finally, since the InCulture platform aims to support the role of the user as creator too, the mobile application facilitates tools for multimedia capturing and upload. Via a dedicated content uploading screen (Figure 9 right), users can capture multimedia content and upload it to the platform. Importing already captured material from the device’s library is also supported. In both cases, users add some basic description of the uploaded content, while the platform extracts further metadata from it, such as location, size, time, etc., and stores them accordingly.

To support multiple platforms (iOS, Android, etc.) the mobile application for InCulture is implemented as a Progressive Web App (PWA) [38], a modern technology that allows the development of platform-agnostic applications. PWAs are based on open technologies such as HTML5 [39], CSS3 [40], and JavaScript [41] and do not need an App Store for distribution since this can be achieved just by entering a URL. With PWAs multiple heterogeneous mobile platforms are supported using a single codebase. Some of the features offered by PWAs include (i) local databases, (ii) content capturing using the camera application of the device, (iii) offline content viewing, (iv) local caching, and more.

4.1.3. Content Management Application

Since the ICH content hosted by the InCulture platform needs to be constantly enriched and extended, a management application is implemented, on which creators can upload, create, and edit content. The management application can be accessed by authorized members only. Access to the views of the Content Management Application is controlled via a hierarchy of user roles, each one granting access to specific views and functionality. For example, a user with a creator role will only be able to upload and edit content, a user with a community moderator role will be able to coordinate community actions and edit its members, while a user with a general administrator role will be able to appoint community moderators and edit the list of users, publish and reject the content, etc.

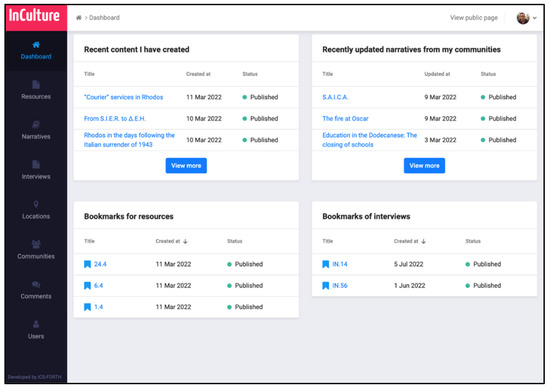

The homepage of the management tool (i.e., Dashboard) presents an overview of the content that is most important and relevant to the user (Figure 10), specifically, the recently created content, recently created narratives by the communities to which the user belongs, bookmarks for ICH resources, and bookmarks for narratives.

Figure 10.

Content Management Application dashboard.

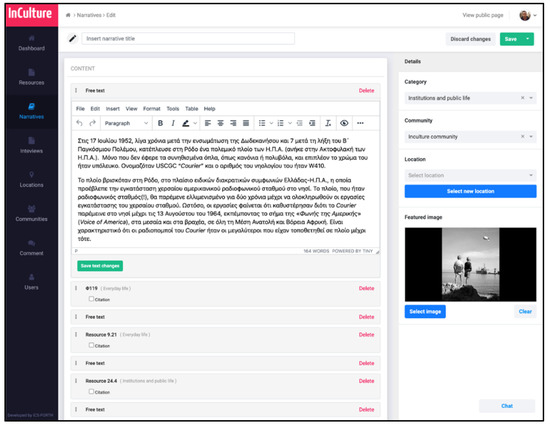

The content management application features a rich web editor (HTML) on which creators can author their ICH resources (Figure 11). The editor supports font formatting, html elements, such as dividers, tables, etc. and multimedia. In addition, the ICH resources include a number of descriptive metadata, such as (i) title, (ii) type, (iii) category, (iv) tags, (v) featured image, (vi) location, (vii) time, and (viii) source.

Figure 11.

Edit page of a single ICH resource (content area contains original text in Greek from the use case).

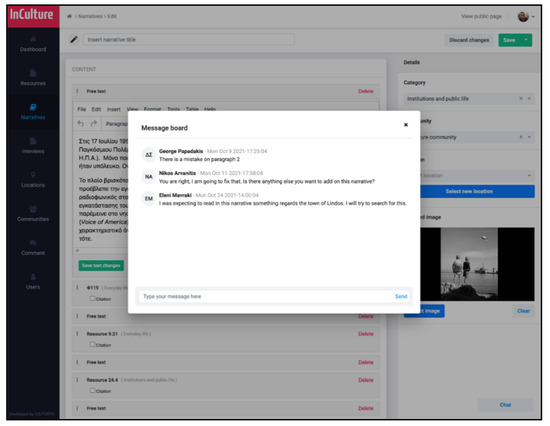

Accordingly, creators can view, edit, and create narratives by combining single ICH resources with additional text and multimedia (Figure 12). The narrative consists of a series of blocks that each includes a reference to a single ICH resource or free text along with the use of multimedia. Blocks can be arranged at the creator’s preference using a drag-and-drop mechanism. The final result is an extended story presenting an ICH topic in a versatile way by combining multiple ICH resources, wrapped with additional blocks of text and multimedia. Moreover, since narratives are meant to be formed collaboratively, a special message board is integrated into this view to support open discussions between the members who are working on it (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Edit page (content area contains original text from the use case in Greek).

Figure 13.

Message board for a narrative.

The management application also facilitates the communities’ administration. Administrators can create, edit, and delete communities and appoint community moderators (Figure 14). A community moderator is responsible for accepting or rejecting member requests. A message board is also featured on this page towards promoting discussions between members of the community, e.g., about upcoming events, planned narratives, etc.

Figure 14.

Community page showing the members and a message board.

The content management application, like the web application, is implemented using Angular [37] for content presentation.

4.2. API Service Provider

The API Service Provider is the core foundation of the system. Its main purpose is to manage and serve content to end-user applications and maintain the synergies between the system components. The API service provider connects to and retrieves data from the database and object storage, performs data manipulation, and exposes content to end-user applications via a well-defined REST API [42]. The same applies to content production, where the content originating from the content management application is posted to the API service provider, which then performs the data-storing procedures. In general, the operations supported by this service include (i) Creating, Reading, Updating, and Deleting (CRUD) resources, (ii) handling uploads and downloads of multimedia content, and (iii) text-based search functionality for content and metadata.

The API service provider is implemented with Node.js [43], a popular open-source technology for building web applications based on JavaScript [41]. Node.js applications are based on asynchronous events, resulting in efficiency and performance.

4.3. Multimedia Object Storage

Multimedia files are essential for the project as they serve as supporting material for the ICH narratives. Multimedia Object Storage is the platform’s central media storage service. Images, videos, audio clips, 3D models, etc. are uploaded and kept organized appropriately for quick access by the system. To support this, the Min.IO [44] solution was integrated, which offers S3-compatible object storage facilities. Min.IO supports high performance, availability, and scalability.

4.4. Database

To maintain and preserve the system’s data and metadata, there is a need for a permanent storage solution that will be responsible for data storage and retrieval within the system. To this end, a MongoDB [45] database is integrated to handle the collections of data and to provide a fast storage solution with instant access. In contrast to relational databases, NoSQL [46] databases like MongoDB offer significant performance increases on queries and efficient large-scale data management.

4.5. Search Engine Index Storage

To support further content exploration within the InCulture platform, a powerful search mechanism is required to enable instant keyword-based text search on the content. To this end, a full-text search engine based on Elasticsearch [47] is integrated to facilitate the efficient storage and searching of big volumes of textual keywords in near real-time. Indexes are stored in a JSON format as key-value pairs.

4.6. Semantic Data Generator Service

To preserve and promote the ICH resources produced within the platform, InCulture supports the modeling and publishing of data collections using semantic web technologies. According to this, ICH resources are modeled using classes and relationships, which are described in popular ontologies created by the scientific community. Through this modeling and classification, both humans and computers can interpret the data and their relationships, thus supporting automated information discovery. Thus, the ICH content created for the InCulture platform is not isolated, but is interconnected to and publicly accessible by related semantic data services and sources.

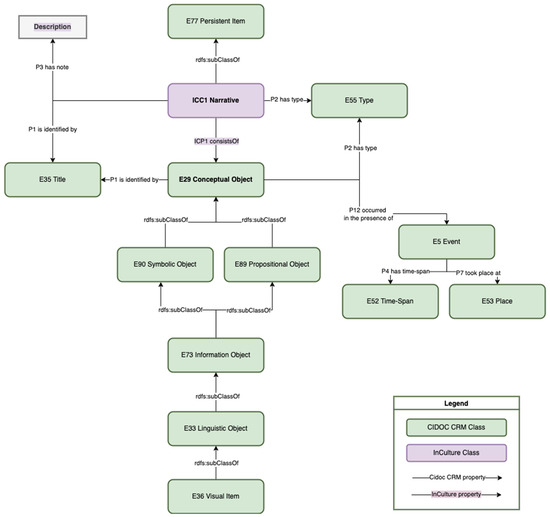

Specifically, for the representation of cultural content, InCulture introduces a representation model, based on and extending CIDOC CRM [5], an ISO standard [48], which aims to support the exchange of information between heterogeneous cultural heritage data sources. In this direction, it offers semantic definitions to transform disparate local data sources into a coherent and general information center.

In particular, CIDOC CRM acts as a best-practice guide for conceptual modeling, while supporting information systems engineers to effectively structure and associate heritage objects in the systems they implement. It also acts as a common language for domain experts and technical teams when analyzing a system’s requirements, ensuring the correct use of concepts for cultural objects. As a common language, it allows the identification of common elements of content that exist in different forms. CIDOC CRM defines a number of base classes and relationships between them. According to this, it supports queries on different sources and consolidates the related data. In addition, CIDOC CRM is extensible, allowing users to create relevant extensions for their application needs.

At the top of the class hierarchy in CIDOC CRM is the “E1 CRM Entity” and below are the (i) “E77 Persistent Item” class, which represents something permanent (e.g., people, animals, things, ideas or products) and the (ii) “E2 Temporal Entity” class, which represents elements that have a duration (e.g., a period of time or an event). “E77 Persistent Item” includes subclasses for physical objects, e.g., the “E22 Human-Made Object” but also for intangible concepts, such as the “E28 Conceptual Object” [49]. The latter and its subclasses are adopted by the InCulture data representation model for ICH resources.

The “E28 Conceptual Object” class can describe intangible objects created or invented by someone and then referred to or discussed between people. Objects of this class can exist simultaneously in several media, such as paper, audio, photographs, paintings, human memory, etc. They cannot be destroyed and exist as long as they can be found in at least one medium or at least one human memory. Their existence ends when the last carrier and last memory is lost.

To model the categories (types) of ICH resources in InCulture, the class “E55 Type” is used. Accordingly, for each defined ICH category an object of the class “E55 Type” is created and ICH resources will be linked to the corresponding category using the relation “P2 has type”.

In addition, each object can optionally refer to a specific geographic point with the use of the “E53 Place” class. ICH resources referring to events are modeled using the “E5 Event” class and the corresponding relationship “P4 has time-span” and class “E52 Time-Span” are utilized accordingly.

Finally, the InCulture representation model (Figure 15) extends CIDOC CRM with the addition of the class “ICE1 Narrative”, which is used to represent narratives. Specifically, using the “ICP2 consists of” property, a narrative can include one or more conceptual (cultural) objects and events that are related in some way, for example, geographically, temporally, or thematically.

Figure 15.

The InCulture ontology.

Content modeling is based on metadata provided by the creators (e.g., time of an event) or has been automatically extracted by uploaded files (e.g., the location where an image is captured, time, etc.). The Semantic Data Generator Service aims to exploit the data and metadata of content entries to generate semantic information. The generated data are produced in the form of N3 RDF triplets [50] and are stored in a graph database to be made publicly available. Third parties can perform queries across the available knowledge graphs using the SPARQL query language [51].

5. Deployment

The InCulture platform consists of multiple heterogeneous services, such as multimedia object storage, an API service provider, an HTTP server (used to serve the web applications), a database, etc. The deployment of such a platform is a challenging task as each service requires a specific environment, settings, or libraries to run. Moreover, services need to run in isolation to maintain the security and integrity of each one. To this end, Docker [52] was utilized, a solution based on the containerization paradigm for virtualization, according to which a container consists of an entire runtime environment, an application, its dependencies (libraries and executables), and configuration files. Docker is an open-source project providing tools for developers to create software and share their development environment as well as for system administrators to deploy software. Docker meets all the requirements for the deployment of a platform like InCulture i.e., (i) components isolation and self-containment, (ii) scalability, (iii) high availability, and (iv) data persistence. The Docker containers for the InCulture services can be deployed on VMs of a cloud infrastructure or any enterprise-level infrastructure such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) [53], based on business demands.

6. System Evaluation

Following the implementation and deployment of the InCulture platform, an evaluation series took place in order to validate its usability. Specifically, the evaluation was conducted in two phases with two different evaluation techniques as described below.

The first phase involved a cognitive walkthrough [54], a technique used to evaluate the learnability of a system from the view of a new user. A team of internal users who had limited or no prior contact with the platform participated in this phase. The participants were provided with a set of data including (i) one interview, (ii) three ICH items sourced out of the interview, (iii) one draft narrative related to the provided resources, (iv) one related photo and (v) one related audio clip. Next, the participants were asked to review the provided material and were given a number of tasks to work on. Some of the tasks were simple, such as (i) creating an account, (ii) content browsing, and (iii) searching for a specific topic, while others were more complex, such as (i) writing a comment for a narrative, (ii) creating a new interview transcription entry, (iii) editing an ICH resource, and (iv) authoring a narrative using feedback from other users. During the walkthrough, the evaluators were present in order to keep notes about the discovered issues reported by the participants. At the end of this evaluation phase, a focus group was held in which the participants and the evaluators discussed the comments and formed a final list of technical issues that were forwarded to the design and development teams.

A heuristic evaluation [55] was later conducted on the updated version of the system with external participants, professionals, and academics in the domains of history, museums, and literature. The participants were given a set of data and tasks to work on and later were asked to fill in a questionnaire and discuss their experience with the evaluators. The results of the heuristic evaluation showed that the platform is effective in supporting the collaborative authoring of ICH resources and narratives and provides attractive graphical user interfaces to promote its content to the visitors. In addition, a series of issues were identified, which were categorized and given to the design and development teams. Based on the reports, an updated final version of the platform was released, which included a public page with detailed instructions on how users can contribute content, the introduction of an automated numbering mechanism for ICH resources created within the system, the development of a featured images suggestion mechanism for narratives, more detailed error messages, and more.

7. Use Case

The recent history of the island of Rhodes, Greece was used as a use case for validating the results of the InCulture platform. The definition of a use case for InCulture is of significant importance because the platform gets populated with content and users; thus, the designers have the chance to watch the ecosystem work in real life and define any areas for improvement. The target of this use case involved the capturing, collection, organization, transcription, translation, and presentation of personal stories and items of local ICH for the historical period in question, with the use of the InCulture platform. The content produced within the use case is valuable for promotional reasons as well, towards the possible commercial exploitation of the platform. The use case acted as the proof of concept for the product tested at a small scale before going to a large scale.

The use case focuses on the period between 1912 and 1948 (WWII): the former date signals the beginning of the Italian administration through the military occupation of the Dodecanese; the latter indicates the date of the island’s annexation to the Greek state. This period has been selected not only for its historical interest but also because it is at the limits of living memory (first level witnesses). Since the events are now eight decades away, people who have memories of the Italian period are constantly decreasing. Furthermore, the surviving memory of that time is not only of local importance, as these people are the last in all of Greece to have experienced foreign sovereignty (not just occupation) and the process of annexation and integration into Greece.

In the period between 1912 and 1943, the Dodecanese islands came under Italian control, initially in the form of military occupation, and later as an internationally recognized Italian possession. The Italian capitulation of September 1943, however, changed the situation and resulted in Nazi Germany occupying the islands. At the end of the war in 1945, the islands temporarily passed into the hands of Britain and from there, in 1947, to Greece.

Initially, Greece was not given sovereignty over the islands, but only their administration, which was carried out by the Dodecanese Military Administration. Annexation by Greece took place in 1948, the islands coming under the civilian General Administration of Dodecanese. This transitional status lasted until 1955, at which time the Dodecanese islands became a regular part of the Greek administrative structure. To this day, the Dodecanese remains the final addition to Greek territory.

7.1. Methodology

The collection of CH resources and population of the InCulture platform took place in three steps: (i) conducting interviews, (ii) production of ICH resources, most of them extracted out of the interviews, and (iii) synthesis of narratives based on the ICH items produced. During the first phase, several unstructured interviews were conducted, with people having first-level testimonies and memories from the period in question. Interviewees not only referred to significant and crucial historic events and facts but also portrayed aspects of everyday life that are rarely recorded in research studies and official documents. After all, ICH is part of everyday life and any discussion about the daily life of a subject also provides information of this nature. Thus, even though oral history is not identical to ICH, methodologically, the use of interviews in the context of ICH research is widespread and has a long history [56]. The relationship of history with collective identity and ICH is emphasized in the very definition of ICH by UNESCO: “This intangible cultural heritage, transmitted from generation to generation, is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, […]” [2].

The interviews, although unstructured, remained organized with a beginning, middle, and end, while simultaneously providing an opportunity for the interviewees themselves to ask questions. The questions asked by the interviewers were clear, using terminology appropriate to the educational level of the interviewees. Transcripts from the interviews were then produced and uploaded to the InCulture platform via the Content Management application. The core user group of the use case studied the transcriptions and extracted multiple atomic pieces of information out of the interviews (ICH resources), for example, what courses were taught in school, how many students there were per class, in what languages they were taught, and so on. Any photos provided during the interviews were also uploaded to the InCulture platform as CH resources.

This analysis and deconstruction of personal stories created the fundamental material used later in building the narratives. Following the interview analysis, the InCulture initial user group formed narratives by combining the atomic ICH resources produced. The pieces of information were wrapped with additional text or multimedia blocks to form an interesting, versatile, story-based narrative.

7.2. Results

In the context of the project trials, eight individuals formed a user community in the InCulture system and collaborated toward producing ICH content. An individual from the initial user group was appointed by the system administrators as the community moderator and was responsible for coordinating the actions of the group. In total, during the content creation process, over 100 messages were exchanged through the collaboration tools of the platform, i.e., the community-wide and the narrative-specific message boards. The data collected and produced during the island of Rhodes use case covered a wide variety of topics and resulted in recording and transcribing 29 open-type interviews, producing 375 single ICH resources and 119 photos documenting the period in question. ICH resources were organized by the creators in four main categories:

- Events—Personal stories

- Ethnography—Folklore

- Everyday life

- Institutions and public life

In addition, each ICH item was characterized by the following attributes:

- Source (interview, online article, book, etc.)

- Location (specific geographic location or area)

- Date (specific or approximate)

- Tags

Unlike single ICH resources, narratives are semantically complete, with a beginning, middle, and end. Narratives consist of a combination of ICH resources (textual, photographic, etc.) and may be supplemented with secondary sources and references. In the context of the use case, 15 narratives were authored using the available ICH resources in the system. The content is uploaded on the online InCulture platform and is publicly available to visitors (in the Greek language, available at https://explore.inculture-project.gr (accessed on 15 September 2022)).

8. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we presented the InCulture platform that features tools and applications to support the creation and presentation of narratives of intangible CH resources through the formation of communities. The platform has considerable potential to improve the quality and learning value of digital cultural resources through the introduction of an affordable, ready-to-use, and cost-effective theoretical and technological framework for the representation and experiential presentation of cultural elements. The adopted approach for storage and semantic data annotation and production ensures that content generated within the platform can be perceived and understood by humans as well as third-party systems, towards creating a network of ICH resources.

In addition, the mobile application created supports AR presentation capabilities and has the potential to increase the awareness of citizens regarding the cultural environment and further engage them to actively participate in the creation of CH resources. Tourism can also benefit from the InCulture platform, as ICH resources can be explored in a location-centric manner, allowing visitors to explore the cultural history of an area during their visits.

Following the initial release of the system, two user evaluations were conducted, producing valuable insights, a cognitive walkthrough with internal users, and a heuristic evaluation with field experts. The feedback gathered from the evaluations was analyzed by the system’s design and development teams towards improving several features. The use case for the island of Rhodes resulted in content population and acted as the proof of concept for the InCulture platform.

At the time of writing, both the platform and mobile application are officially online and accessed by users as part of the dissemination activities of the InCulture project. It is expected that this will provide the possibility of evaluating, in the future, the combination of web-based and location-based narrative provision in terms of user experience and user satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M., I.K. and N.P.; Formal analysis, G.M, N.P., I.K.; Funding acquisition, N.P. and M.A.; Methodology, G.M.; Project administration, G.M., I.K., C.S.; Software, G.M., E.P., K.V. and N.A.; Supervision, M.A. and C.S.; Validation, I.P. and S.A.P.; Visualization, G.M., E.P., K.V. and N.A.; Writing—original draft, G.M. and N.P.; Writing—review & editing, I.K., C.S., M.A., N.P., I.P., S.A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted in the context of the InCulture project, funded by the EPAnEK Greek national co-funded operational program “Competitiveness Entrepreneurship and Innovation”.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The project InCulture would like to thank the participants of the knowledge collection activities for the provision of testimonies, memories, and valuable information for the representation of the fifteen narratives of the InCulture use case.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- What Is Intangible Cultural Heritage? Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003 (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- UNESCO; ICH. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- InCulture Platform. Available online: https://explore.inculture-project.gr (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- InCulture Project. Available online: http://www.inculture-project.gr/ (accessed on 7 June 2022).

- Doerr, M.; Ore, C.-E.; Stead, S. The CIDOC conceptual reference model: A new standard for knowledge sharing. In Proceedings of the Tutorials, Posters, Panels and Industrial Contributions at the 26th International Conference on Conceptual Modeling, Auckland, New Zealand, 5–9 November 2007; Australian Computer Society, Inc.: Darlinghurst, Australia, 2007; Volume 83, pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- NARRATIVE|Definition of NARRATIVE by Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com also the meaning of NARRATIVE. (n.d.). Lexico Dictionaries|English. Retrieved 9 March 2021. Available online: https://www.lexico.com/definition/narrative (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Aristotle, Poetics. In Oxford World’s Classics; Kenny, A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0191635809. [Google Scholar]

- Shklovsky, V. Art as technique. In Twentieth-Century Literary Theory; Newton, K.M., Ed.; Palgrave: London, UK, 1997; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavliakis, K.N.; Karagiannis, G.T.; Mitkas, P.A. Semantic Web in cultural heritage after 2020. In Proceedings of the International Semantic Web Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 11–15 November 2012; pp. 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Doerr, M.; Gradmann, S.; Hennicke, S.; Isaac, A.; Meghini, C.; Van de Sompel, H. The Europeana Data Model (EDM). In Proceedings of the World Library and Information Congress, Gothenburg, Sweden, 10–15 August 2010; Volume 10, p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, C.; Tryfonopoulos, C.; Weikum, G. MinervaDL: An Architecture for Information Retrieval and Filtering in Distributed Digital Libraries. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Research and Advanced Technology for Digital Libraries, ECDL, Budapest, Hungary, 16–21 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomberg, R.; Dekkers, M.; Gradmann, S.; Lindquist, M.; Lupovici, C.; Meghini, C.; Verleyen, J. Functional Specification for Europeana Rhine Release, D3.1 of Europeana v1.0 project (public deliverable). Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/files/Europeana_Professional/Projects/Project_list/Europeana_Version1/Deliverables/D3.2%20%20%20%20%20Functional%20specification%20for%20the%20Europeana%20Danube%20release_370704.pdf (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Meghini, C.; Bartalesi, V.; Metilli, D. Representing narratives in digital libraries: The narrative ontology. Semant. Web 2021, 12, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalesi, V.; Meghini, C.; Metilli, D. Steps towards a formal ontology of narratives based on narratology. In Proceedings of the 7th Workshop on Computational Models of Narrative (CMN 2016), Krakow, Poland, 11–12 July 2016; Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik: Wadern, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bartalesi, V.; Meghini, C.; Metilli, D. A conceptualisation of narratives and its expression in the CRM. Int. J. Metadata Semant. Ontol. 2017, 12, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerr, M.; Bekiari, C.; nationale de France, B. FRBRoo, a conceptual model for performing arts. In Proceedings of the 2008 Annual Conference of CIDOC, Athens, Greece, 15–18 September 2008; pp. 6–18. Available online: http://www. cidoc2008.gr/cidoc/Documents/papers/drfile (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Hobbs, J.R.; Pan, F. Time Ontology in OWL, W3C Recommendation. 2017. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/owl-time/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Available online: https://www.w3.org/Submission/SWRL/ (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Meghini, C.; Bartalesi, V.; Metilli, D.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X. Mingei Crafts Ontology. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3742828 (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Dimitropoulos, K.; Manitsaris, S.; Tsalakanidou, F. Capturing the Intangible: An Introduction to the i-Treasures Project. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–8 January 2014; pp. 773–781. [Google Scholar]

- Partarakis, N.; Doulgeraki, V.; Karuzaki, E.; Galanakis, G.; Zabulis, X.; Meghini, C.; Bartalesi, V.; Metilli, D. A Web-Based Platform for Traditional Craft Documentation. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2022, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partarakis, N.N.; Doulgeraki, P.P.; Karuzaki, E.E.; Adami, I.I.; Ntoa, S.S.; Metilli, D.D.; Bartalesi, V.V.; Meghini, C.C.; Marketakis, Y.Y.; Kaplanidi, D.D.; et al. Representation of socio-historical context to support the authoring and presentation of multimodal narratives: The Mingei Online Platform. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021, 15, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partarakis, N.; Kaplanidi, D.; Doulgeraki, P.; Karuzaki, E.; Petraki, A.; Metilli, D.; Bartalesi, V.; Adami, I.; Meghini, C.; Zabulis, X. Representation and Presentation of Culinary Tradition as Cultural Heritage. Heritage 2021, 4, 612–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghini, C.; Bartalesi, V.; Metilli, D.; Benedetti, F. A software architecture for narratives. In Proceedings of the Italian Research Conference on Digital Libraries, Udine, Italy, 25–26 January 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Metilli, D.; Bartalesi, V.; Meghini, C. A Wikidata-based tool for building and visualising narratives. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2019, 20, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabulis, X.; Partarakis, N.; Meghini, C.; Dubois, A.; Manitsaris, S.; Hauser, H.; Magnenat Thalmann, N.; Ringas, C.; Panesse, L.; Cadi, N.; et al. A Representation Protocol for Traditional Crafts. Heritage 2022, 5, 716–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathioudakis, G.; Klironomos, I.; Partarakis, N.; Papadaki, E.; Anifantis, N.; Antona, M.; Stephanidis, C. Supporting Online and On-Site Digital Diverse Travels. Heritage 2021, 4, 4558–4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partarakis, N.; Patsiouras, N.; Evdemon, T.; Doulgeraki, P.; Karuzaki, E.; Stefanidi, E.; Ntoa, S.; Meghini, C.; Kaplanidi, D.; Fasoula, M.; et al. Enhancing the educational value of tangible and intangible dimensions of traditional crafts through role-play gaming. In Proceedings of the International Conference on ArtsIT, Interactivity and Game Creation, Aalborg, Denmark, 10–11 December 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Partarakis, N.; Karuzaki, E.; Doulgeraki, P.; Meghini, C.; Beisswenger, C.; Hauser, H.; Zabulis, X. An approach to enhancing contemporary handmade products with historic narratives. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2021, 16, 124–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zidianakis, E.; Partarakis, N.; Ntoa, S.; Dimopoulos, A.; Kopidaki, S.; Ntagianta, A.; Ntafotis, E.; Xhako, A.; Pervolarakis, Z.; Kontaki, E.; et al. The invisible museum: A user-centric platform for creating virtual 3D exhibitions with VR support. Electronics 2021, 10, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, H.; Beisswenger, C.; Partarakis, N.; Zabulis, X.; Adami, I.; Zidianakis, E.; Patakos, A.; Patsiouras, N.; Karuzaki, E.; Foukarakis, M.; et al. Multimodal Narratives for the Presentation of Silk Heritage in the Museum. Heritage 2022, 5, 461–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuzaki, E.; Partarakis, N.; Patsiouras, N.; Zidianakis, E.; Katzourakis, A.; Pattakos, A.; Kaplanidi, D.; Baka, E.; Cadi, N.; Magnenat-Thalmann, N.; et al. Realistic virtual humans for cultural heritage applications. Heritage 2021, 4, 4148–4171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meghini, C.; Bartalesi, V.; Metilli, D.; Benedetti, F. Introducing narratives in Europeana: A case study. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2019, 29, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, A. Writing Effective Use Cases; Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomin, J. What is human centred design? Des. J. 2014, 17, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9241-210:2019. Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction—Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Angular. Available online: https://angular.io/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Progressive Web App Definition. Available online: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Progressive_web_apps (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- HTML 5 Specification. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/2011/WD-html5-20110405/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- CSS3. Available online: https://www.w3.org/Style/CSS/specs.en.html (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- JavaScript. Available online: https://www.javascript.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- What is REST. Available online: https://restfulapi.net/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Node.js. Available online: https://nodejs.org/en/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Min.IO. Available online: https://min.io/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- MongoDB. Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- What Is NoSQL? Available online: https://www.mongodb.com/nosql-explained (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- ElasticSearch. Available online: https://www.elastic.co/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- ISO 21127:2014. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/57832.html (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- E28 Conceptual Object. Available online: https://cidoc-crm.org/Entity/e28-conceptual-object/version-6.2 (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- N3 RDF Triplets. Available online: https://www.w3.org/2001/sw/RDFCore/ntriples/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- SPARQL Query Language for RDF. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-sparql-query (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Docker. Available online: https://www.docker.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- AWS. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/ (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Blackmon, M.H.; Polson, P.G.; Muneo, K.; Lewis, C. Cognitive Walkthrough for the Web. CHI 2002, 4, 463–470. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Heuristic evaluation. In Usability Inspection Methods; Nielsen, J., Mack, R.L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Carmezim Gonçalves, Μ. A life worth remembering. Thoughts on Oral History and community’s collective memory, MEMORIAMEDIA Review 6. Art. 6. 2021. Available online: https://review.memoriamedia.net/index.php/6-article-6 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).