Trace the Untraceable: Online Image Search Tools for Researching Late Antique Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. The Value of Examining the Use of Digital Image Libraries by Scholars of Less Prominent Disciplines

1.3. Metadata Standards in the Field of Archaeology and Art History and Their Aplicability for Less Prominent Fields of Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Online Repositories under Examination

2.2. Types of Conducted Searches and Search Terms Used

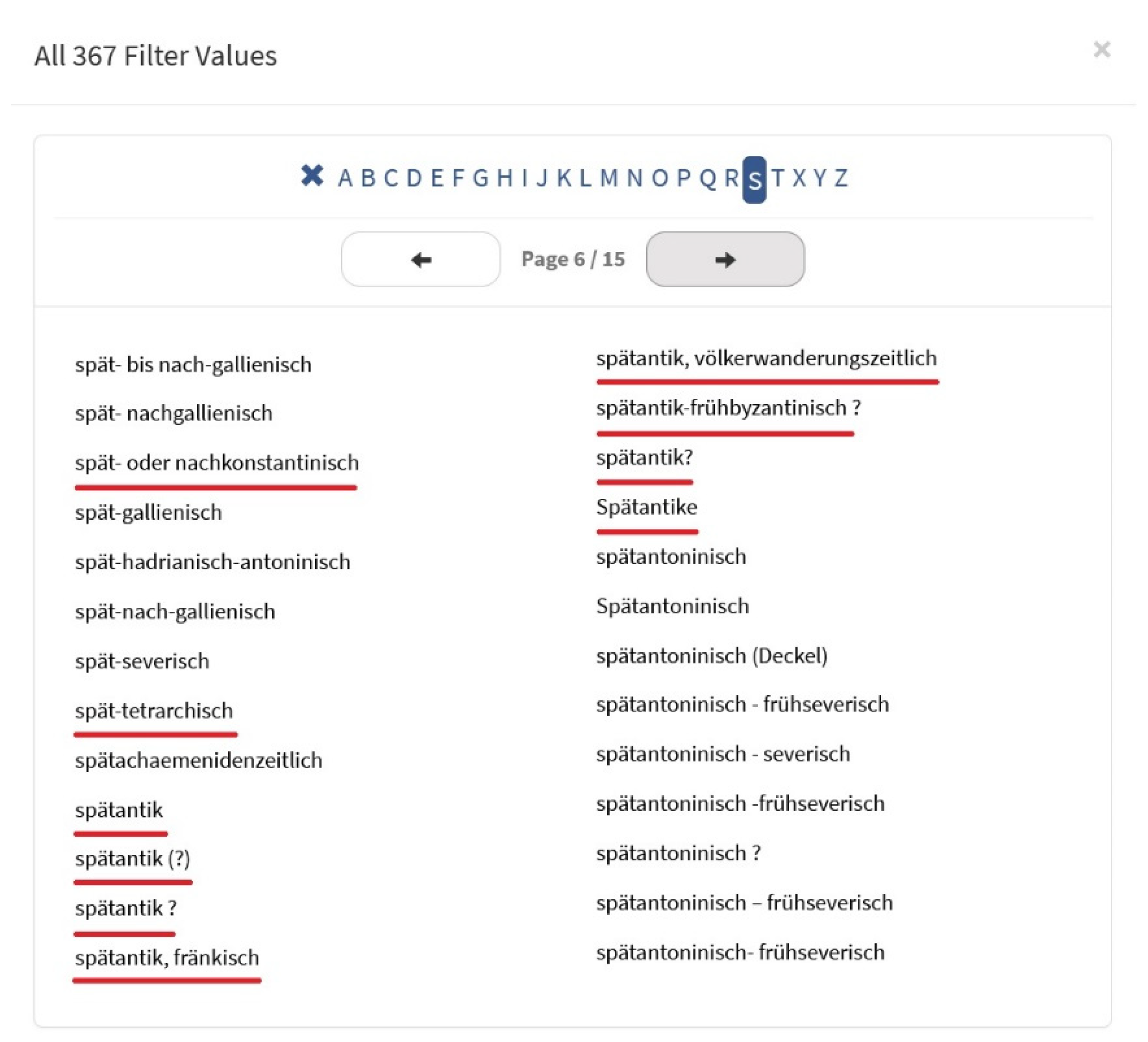

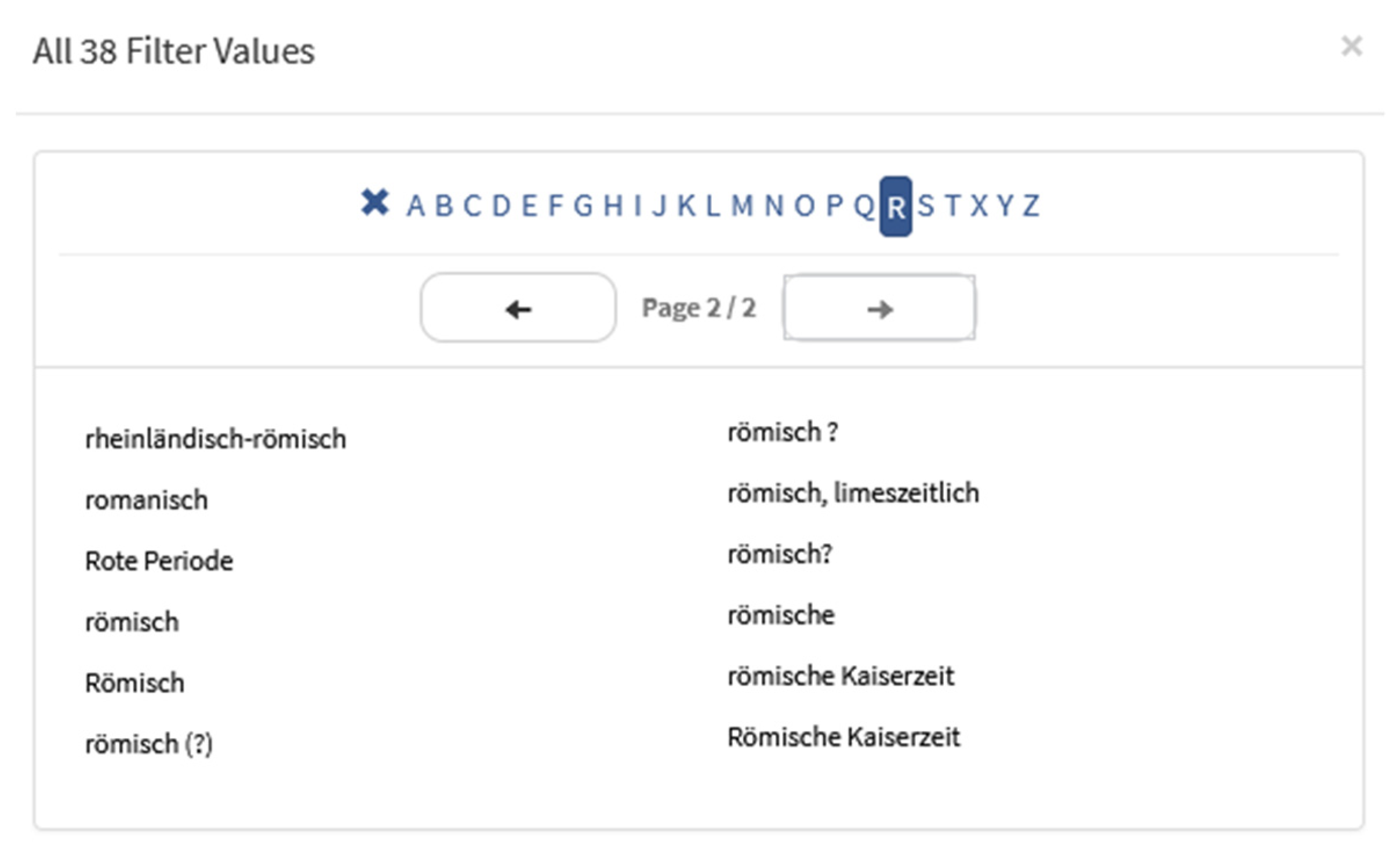

2.3. Issues of Definition Regarding the Search Terms Used

2.4. Alternative Search Method Based on Chronology Alone

3. Results

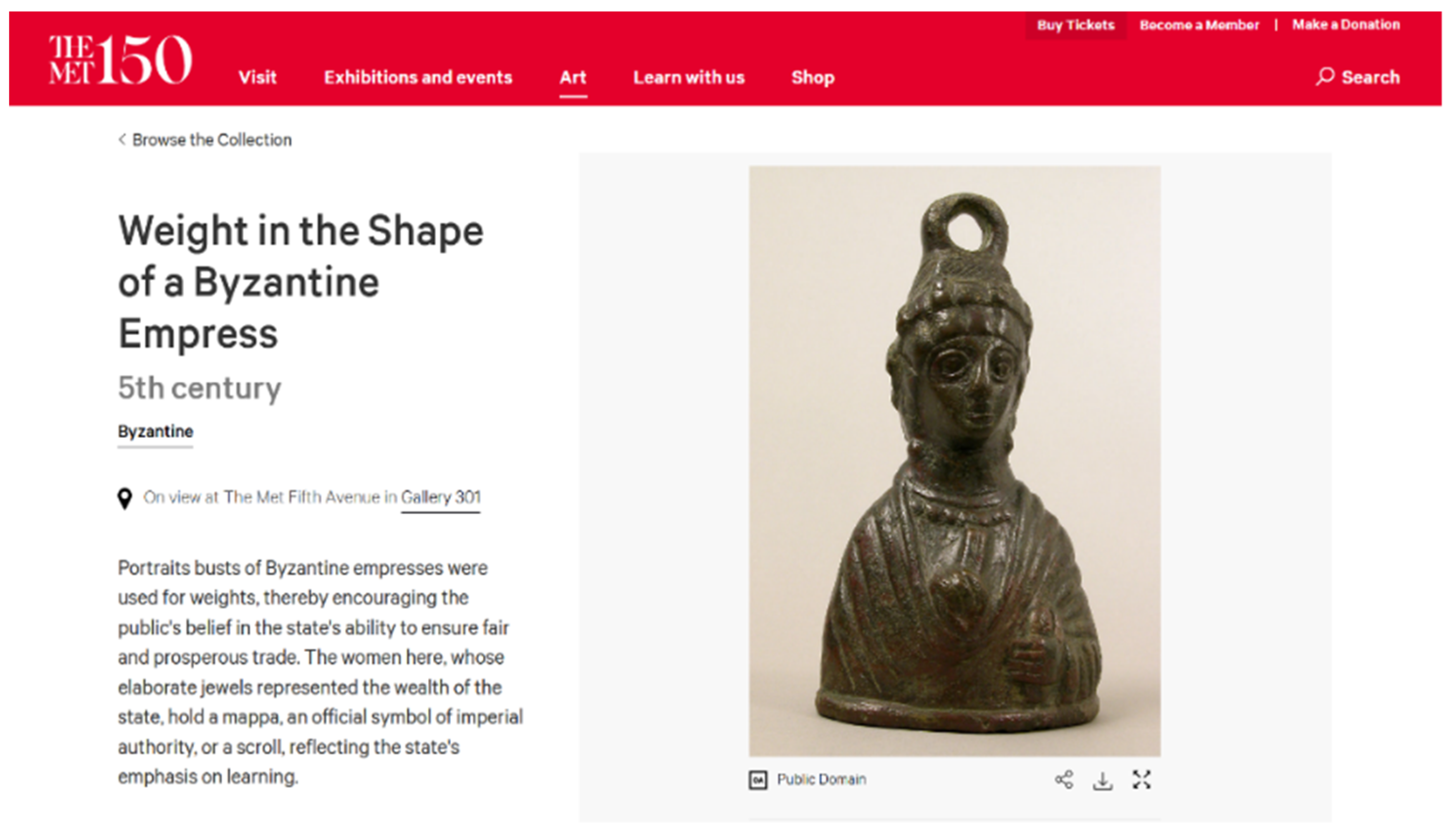

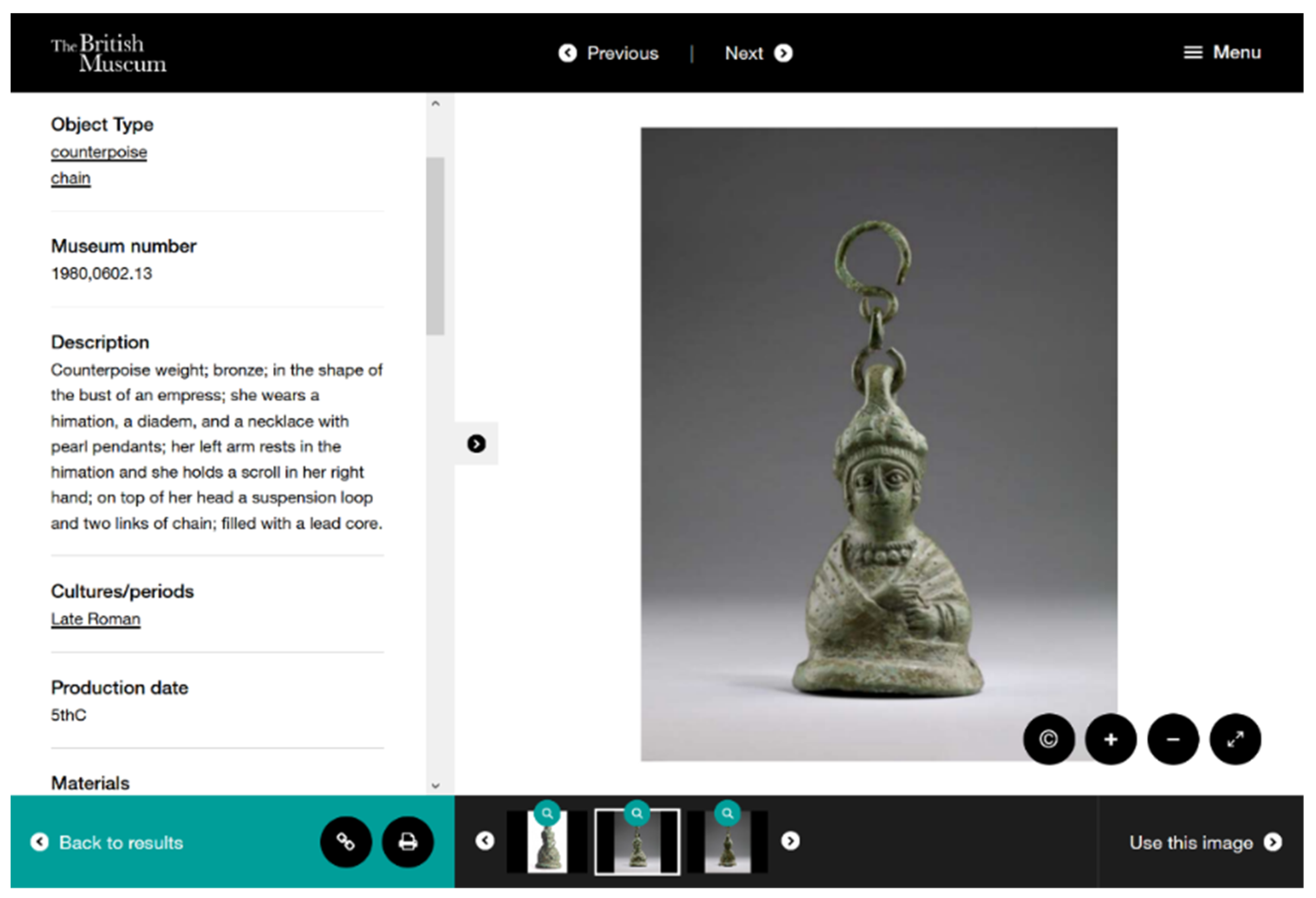

3.1. Online Museum Collections

3.1.1. General Observations

3.1.2. Results Based on Keyword Searches

3.1.3. Results Based on Chronological Searches

3.2. Archaeological and Art Historical Databases

3.2.1. Brief Descriptions of the Repositories under Examination

3.2.2. General Observations

3.2.3. Results Based on Keyword Searches

3.2.4. Results Based on Chronological Searches

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- British Museum, London (BM), https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/search (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), http://www.clevelandart.org/art/collection/search (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Getty Museum, Los Angeles, http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Harvard Art Museums, https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (KHM), https://www.khm.at/objektdb/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MfA), https://collections.mfa.org/collections (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Princeton University Art Museum, https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/search/collections (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SBM), http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (MET), https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Victoria and Albert Museum, London (VAM), http://collections.vam.ac.uk/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- ACOR Photo Archive, https://acor.digitalrelab.com (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Arachne, https://arachne.dainst.org/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

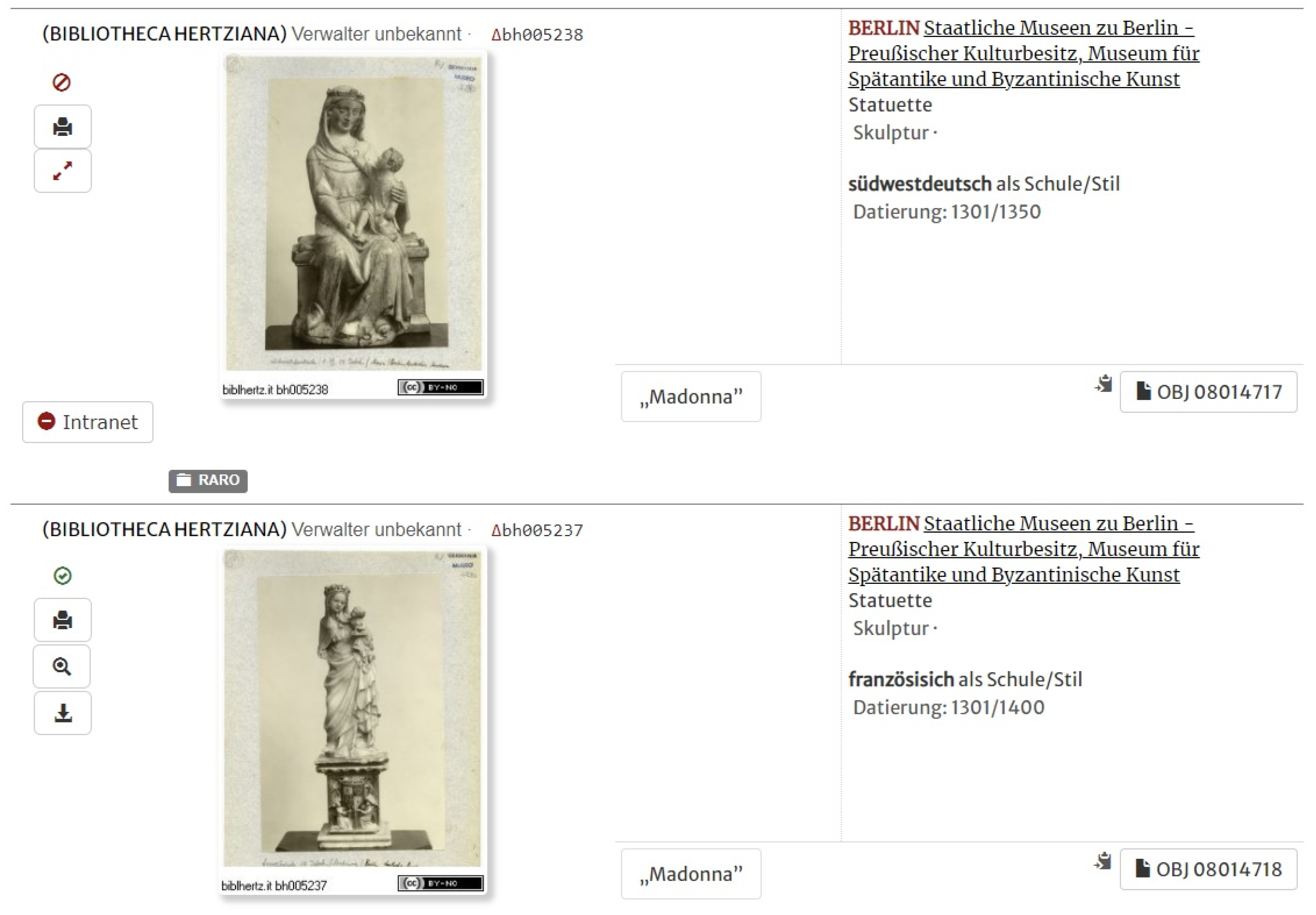

- Bibliotheca Hertziana, http://foto.biblhertz.it/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Bildindex der Kunst & Architektur, https://www.bildindex.de/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

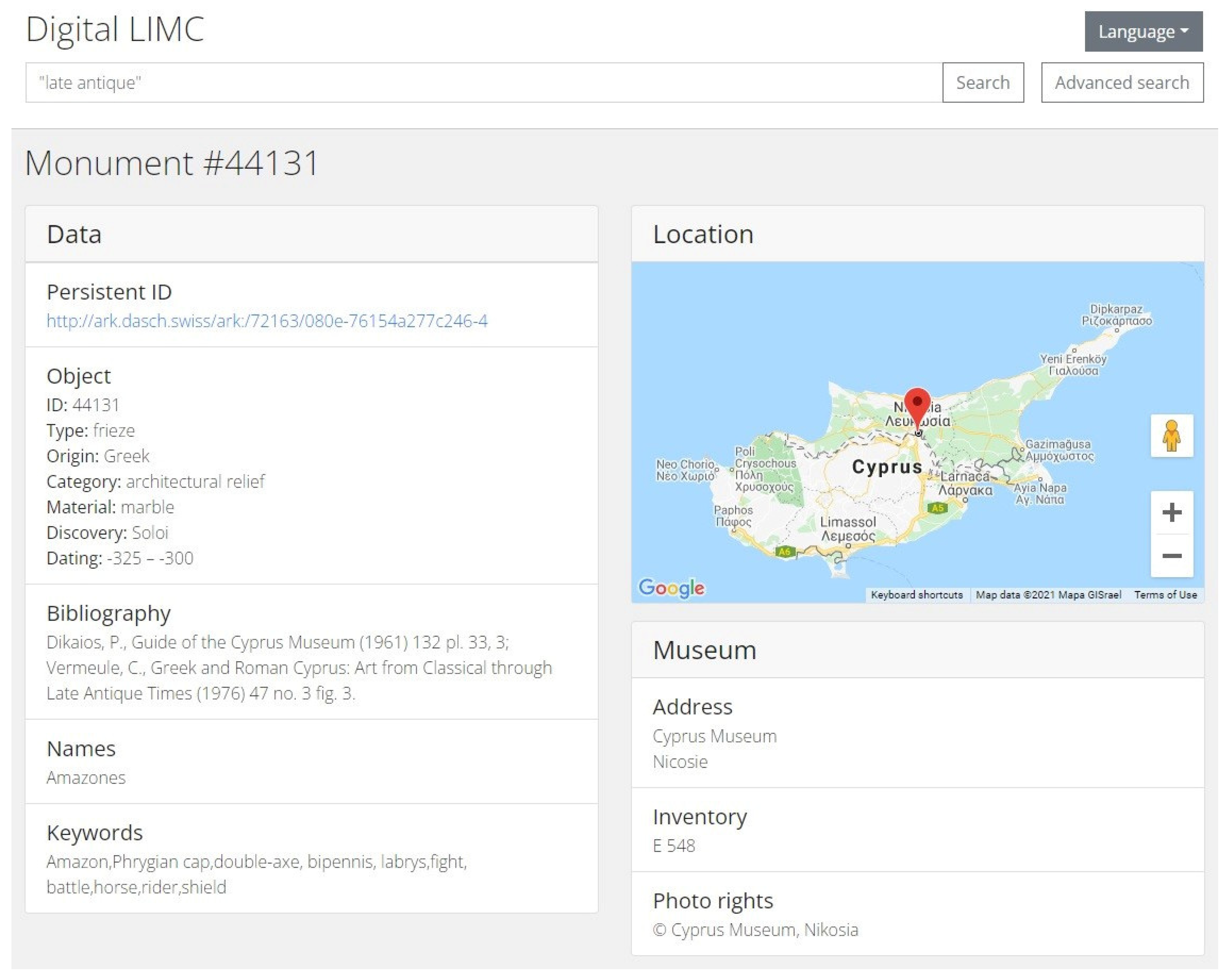

- Digital LIMC, https://weblimc.org/page/home (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Europeana, https://www.europeana.eu (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- KHI Photothek, http://photothek.khi.fi.it/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

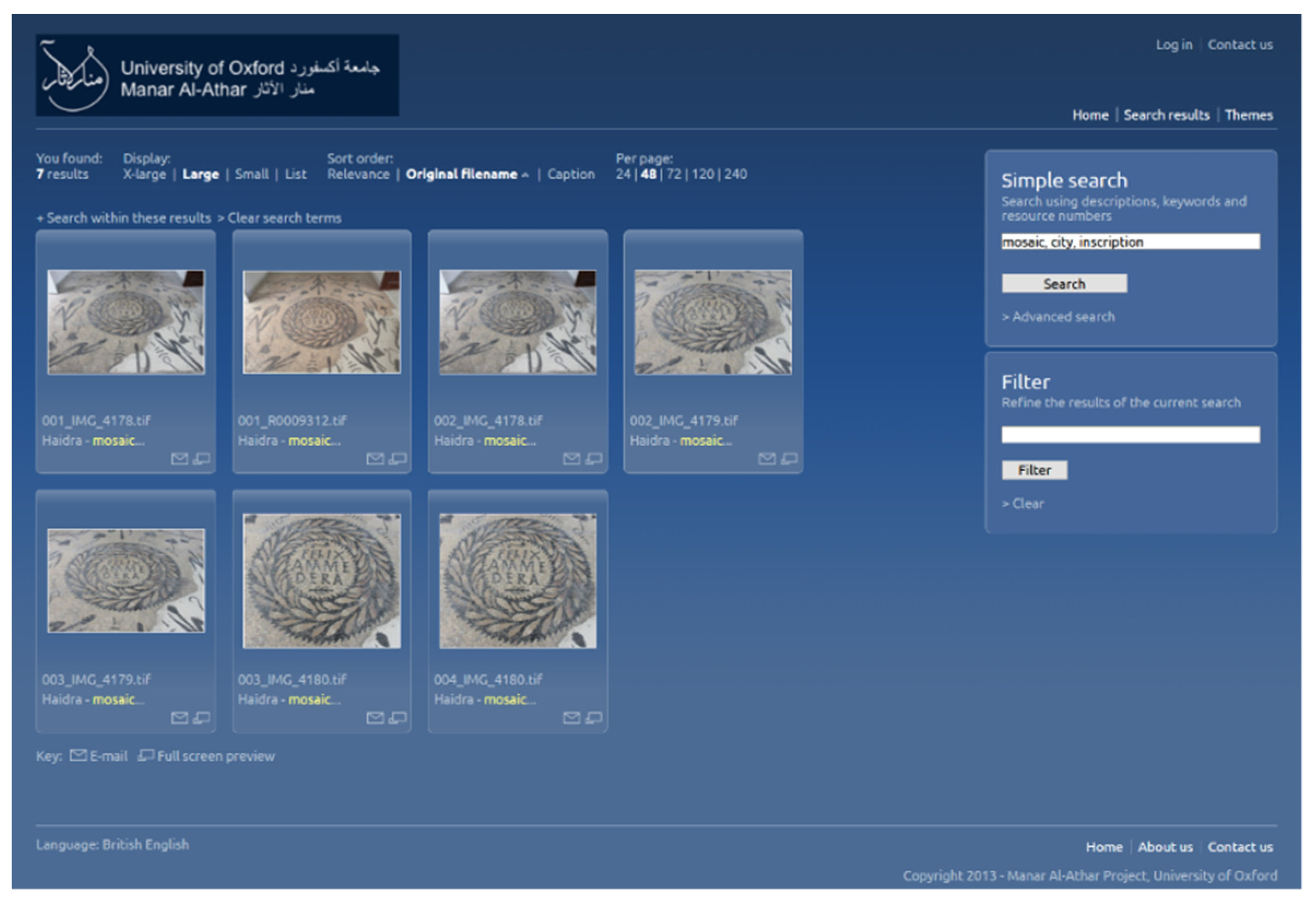

- Manar Al-Athar, http://www.manar-al-athar.ox.ac.uk/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Princeton Archaeological Archives, http://vrc.princeton.edu/archives/ (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Ubi Erat Lupa, http://lupa.at (accessed on 10 February 2021);

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (WI-ID), https://iconographic.warburg.sas.ac.uk/vpc/VPC_search/main_page.php (accessed on 10 February 2021).

Appendix B

| Site | Image Only 1 | On View | Object Title/Name | Object Type | Culture/Artist/Maker | Date/Period | Place of Origin | Material/Technique/Medium | Other Advanced Search Options/Filters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | [cb] | [cb] | [dd] | - | [dd] Culture/Period/Dynasty | [dd] Production Date | [dd] Place | [dd] Material [dd] Technique | [dd] Person/Organisation [dd] Ethnic group [dd] Ware [dd] Escapement [dd] Denomination [dd] School/Style [dd] Subject |

| CMA | - | [cb] | [ft] | [dd] | [ft] Culture [ft] Artist | [ft] After Before | - | [ft] Medium | [dd] Location [dd] Collection [dd] Department [ft] Credit line [ft] Accession number [ft] Catalogue raisonné [ft] Provenance [ft] Citation [ft] Exhibition history [dd] Rights [cb] Highlights [cb] Open Access [cb] With videos [cb] In 3-D |

| Getty | [cb] | [cb] | [ft] | - | [ft] Maker/Artist [ft] Culture/Country | - | - | [ft] Medium/ Materials | [ft] Object Number [ft] Provenance Name [ft] Collecting Area [cb] Open Content Program |

| Harvard | - | [cb] | - | [dd] | [dd] Culture | [dd] Century [dd] Period | [dd] Place | [dd] Technique/Medium | [dd] Classification [dd] Gallery |

| KHM | [cb] | [cb] | [dd] | - | - | [dd] Period | - | - | [dd] Person |

| MfA 2 | [cb] | [cb] | [ft] | - | [ft] Artist/Maker [ft] Culture | [ft] Date Range | - | [ft] Medium/ Technique | [ft] Accession Number [ft] Credit Line [ft] Provenance [ft] Description [dd] Collection(s) [dd] Classification(s) [dd] Location(s) [cb] Has Audio/Video [cb] Collection Objects Only [cb] Deaccessioned Objects Only |

| Princeton | [cb] | - | - | [dd] | [dd] Artist [dd] Culture | [dd] Date [dd] Period | - | - | - |

| SMB | - | - | [ft] | - | - | [ft] Date [ft] Year from ... to | - | [ft] Material | [ft] Full Text Search [ft] Collection [ft] Name/Person [ft] Object/Term [ft] Geographical Reference |

| MET | [cb] | [cb] | [ft] | [dd] 3 | [ft] Artist/Culture | [dd] Date/Era | [dd] Geographic Location | - | [ft] All Fields [ft] Description [ft] Gallery [ft] Accession Number [dd] Department [cb] Highlights [cb] Open Access |

| VAM | [rb] | - | [ft] | - | [ft] Artist/Maker | [ft] Earliest year (YYYY) [ft] Latest year (YYYY) | [ft] Place of origin | [ft] Material/ techniques | [ft] Museum object number [ft] Current location [rb] All Records [rb] Best quality records including image and detailed description |

| Site | Culture/Artist/Maker | Chronological Filters | Geographical Filters | Type/Material/Technique/Medium | Other Advanced Search Options/Filters | Filter Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACOR Photo Archive | - | - | [dd] Place name [dd] Country [dd] Arabic place name | - | [dd] Theme [dd] Keywords [dd] Collection name | simultaneously |

| Arachne | - | [dd/index] Dating, Epoch (1554 options) | [dd/index] Place (5149 options) [dd/index] Location Type (20 options) [dd/index] City (5060 options) [dd/index] Subregion (190 options) [dd/index] Country (105 options) [dd/index] Region (153 options) | - | [dd] Category [dd] Contains Images (2 options) [dd/index] Literature (19420 options) | simultaneously |

| Bibliotheca Hertziana | [ft] artist [obj] [dd] school/style (anonymous) [img] [dd] photographer/photo archive | [obj] [dd] date [img] [dd] acquisition date | [ft] City [obj] [dd] city | [obj] [dd] technique/material [img] [dd] color/technique | [dd] Object categories (7 further options): building/collection; title; classification; person/portrait; role; bibliography; inventory n.; [dd] Image categories (1 further option): file/photo/neg. n.; [tag cloud] Person, Portrait, Private Collection [tag cloud] Photo Archive, Photographer | filters can be used simultaneously, but the user can choose only one of the ‘Object categories’ [obj] and ‘Image categories’ [img] while the two ‘tag cloud’ options immediately redirect to an index |

| Bildindex der Kunst & Architektur | [obj] [ft + tag cloud] Arist | [obj] [ft] Date | [obj] [ft + tag cloud] Location | [obj] [ft + tag cloud] Technique [obj] [tag cloud] Type/ Genre | Image filters: [ft + tag cloud] Photographer [ft + tag cloud] Topic [ft + tag cloud] Technique [date] Date [ft + tag cloud] Image provider [ft + tag cloud] Collection | user has to choose between searching for images [img] or for objects [obj]; filters can be used simultaneously |

| Digital LIMC | [ft] Artist | - | [ft] Place of discovery [ft] Museum name [ft] Museum city | [ft] Technique | [ft] ID [ft] Category [ft] Description [ft] Mythological figure [ft] Object [ft] Inventory Number [ft] LIMC article [ft] LIMC article number [ft] ThesCRA chapter name [ft] ThesCRA article name | one at a time |

| Europeana | - | - | [cb] Providing country (45 options) [cb] Institution (50 options) | [cb] Type of Media (5 options) | [rb] Collection (13 options) [cb] Can I use this? (3 options) [cb] Language (37 options) [cb] Aggregator (50 options) [cb] Color (50 options) [cb] Image orientation (2 options) [cb] Image size (2 options) [cb] File format (33 options) [cb] Item quality (1 option) | simultaneously |

| KHI Photothek | [ft] Artist/Manufacturer [ft] Photographer | - | [ft] Location [ft] Location represented | [ft] Object type [ft] Material/Technique | [ft] Title [ft] Full Index [ft] Document number [ft] Subject [ft] Person depicted [ft] Copyright holder [ft] Negative Number [ft] Acquisition type [ft] Owner Scan | user has to choose between searching for images [img] or for objects [obj]; filters can be used one at a time |

| Manar Al-Athar | [ft] Credit | [dd] By date | [cb] Country (18 options) | [rb] Resources of all types | [rb] Photo [rb] Collections [ft] Title [ft] Caption [ft] Resource ID(s) [ft] Original filename [ft] Keywords [ft] Extracted text | simultaneously |

| Princeton Archaeological Archives | - | - | - | [dd] Search by Type | [ft] Search for Keywords [ft] Narrow by Specific Fields (89 options in combination with Boolean operators) [ft] Search by a range of ID#s [dd] Search by Collection [ft] Search by Tags [dd] Featured/Non-Featured | simultaneously |

| Ubi Erat Lupa | - | [dd] Date (Phase) [ft] Date from (year) to (year) | [dd] Place of discovery [dd] Ancient place of discovery, Province [dd] Current location | [ft] Inscription text, Type | [ft] Title, Object, Iconography [ft] Number [ft] Museum, Inventory number [ft] Image rights [ft] Literature [ft] Full text search (except place of discovery, current location, museum, ancient place of discovery) | simultaneously |

| WI-ID | [dd] Artist | [dd] Limit by [century] (earliest)–(latest) [dd] Auction date | [dd] Location | - | [ft] Search by subject keyword(s) [dd] Manuscript number [dd] Author/book [dd] Special collection + [ft] Number | simultaneously |

| Site | Custom Date Range | Epoch/Period |

|---|---|---|

| British Museum, London | yes | yes |

| Cleveland Museum of Art | yes | no |

| Getty Museum, Los Angeles | no | no |

| Harvard Art Museums | no | yes |

| Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna | yes | yes |

| Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | yes | no |

| Princeton University Art Museum | yes | yes |

| Staatliche Museen zu Berlin | yes | no |

| The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York | no | yes |

| Victoria and Albert Museum, London | yes | no |

| Site | Browse by Time Period 1 | Browse by Search Term 2 | Number of Results | Total Number of Listed Items 3 | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Museum, London | - | Roman | 317,456 | 4,500,000 | 7.05% |

| Roman | - | 248,533 | 5.52% | ||

| - | Renaissance | 5682 | 0.13% | ||

| Cleveland Museum of Art | - | Roman | 1258 | 63,754 | 1.97% |

| - | Renaissance | 472 | 0.74% | ||

| Getty Museum, Los Angeles | - | Roman | 13,064 | 157,493 | 8.29% |

| - | Renaissance | 1263 | 0.80% | ||

| Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA | - | Roman | 10,262 | 235,878 | 4.35% |

| Roman periods 2 | - | 8042 | 3.41% | ||

| - | Renaissance | 50 | 0.02% | ||

| Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (KHM) 3 | - | Roman | 1937 | 23,963 | 8.08% |

| - | römisch* | 791 | 23,963 | 3.30% | |

| - | Renaissance | 117 | 23,963 | 0.49% | |

| Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | - | Roman | 9955 | 439,557 | 2.26% |

| - | Renaissance | 489 | 0.11% | ||

| Princeton University Art Museum | - | Roman | 2319 | 55,692 | 4.16% |

| Roman Imperial | - | 244 | 0.44% | ||

| - | Renaissance | 76 | 0.14% | ||

| Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB) | - | Roman | 699 | 261,679 | 0.27% |

| - | römisch* | 22,020 | 8.41% | ||

| - | Renaissance | 657 | 0.25% | ||

| The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (MET) | - | Roman | 31,426 | 406,000 | 7.74% |

| - | Renaissance | 4241 | 1.04% | ||

| Victoria and Albert Museum, London | - | Roman | 9603 | 1,230,805 | 0.78% |

| - | Renaissance | 19,839 | 1.61% |

| Site | Focus | Custom Date Range | Epoch/Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACOR Photo Archive | Cultural Heritage, Jordan | no | no |

| Arachne | Archaeology | no | yes |

| Bibliotheca Hertziana | Art History, Italy | no 1 | no |

| Bildindex | Art History, predominantly Europe | yes | no |

| Digital LIMC | Art History, iconography, classical mythology | no | no |

| Europeana | Cultural Heritage | no | no |

| KHI Photothek | Art History, Italy | no | no |

| Manar Al-Athar | Archaeology/Art History, Eastern Mediterranean | no 2 | no |

| Princeton Archaeological Archives | Archaeology | no 2 | no |

| Ubi Erat Lupa | Archaeology, Roman Empire | yes | yes |

| WI-ID | Art History, iconography | yes | no |

| Site | Browse by Time Period 1 | Browse by Search Term | Number of Results | Total Number of Listed Items | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACOR Photo Archive (images) | Roman | 4831 | 31,830 | 15.18% | |

| Renaissance | 20 | 0.06% | |||

| Arachne (objects) | Roman | 18,644 | 4,520,856 | 0.41% | |

| römisch* | 129,430 | 2.86% | |||

| Renaissance | 595 | 0.01% | |||

| Römisch | 1 | 0.00% | |||

| Renaissance | 4 | 0.00% | |||

| Bibliotheca Hertziana (images) | Roman | 692 | 395,099 | 0.18% | |

| römisch* | 18,428 | 4.66% | |||

| Renaissance | 310 | 0.08% | |||

| Bildindex (objects) | Roman | 10,462 | 1,833,998 | 0.57% | |

| römisch | 118,630 | 6.47% | |||

| Renaissance | 547 | 0.03% | |||

| Digital LIMC (objects) | Roman | 11 | unknown | unknown | |

| Renaissance | 3 | ||||

| Europeana (images) | Roman | 140,807 | 52,046,985 | 0.27% | |

| Römisch* | 53,306 | 0.10% | |||

| Renaissance | 13,872 | 0.03% | |||

| KHI Photothek (objects) | Roman | 545 | 28,851 | 1.89% | |

| römisch* | 659 | 2.28% | |||

| Renaissance | 27 | 0.09% | |||

| Manar al-Athar (images) | Roman | 1284 | 87,528 | 1.47% | |

| Renaissance | 58 | 0.07% | |||

| Princeton Archaeological Archives (images) | Roman | 425 | 10,366 | 4.10% | |

| Renaissance | 4 | 0.04% | |||

| Ubi Erat Lupa 2 (images) | Roman | 1533 | 31,906 | 4.80% | |

| römisch* | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Renaissance | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| WI-ID (images) | Roman | 11,501 | 105,880 | 10.86% | |

| Renaissance | 5020 | 4.74% |

References

- Simon, H.; Hohmann, G.; Verstegen, U. Prometheus—Das verteilte digitale Bildarchiv für Forschung & Lehre. Synergetische Nutzung heterogener Datenbasen in den Geisteswissenschaften. Inf. Wiss. Prax. 2002, 6, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H. “prometheus” und Justitia—Bildarchive der Kunst- und Kulturwissenschaften im Spannungsfeld des medialen Umbruchs hin zu einer digitalen Informationsgesellschaft. In Forschung und Lehre im Informationszeitalter—Zwischen Zugangsfreiheit und Privatisierungsanreiz; Pfeifer, K.-N., Gersmann, G., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germay, 2007; Volume 4, pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Förtsch, R.; Keuler, M. Cologne Digital Archaeology Laboratory—Arbeitsstelle Für Digitale Archäologie. Köln. Bonn. Archaeol. 2011, 1, 174–176. [Google Scholar]

- Scheding, P.; Krempel, R.; Remmy, M. “Vom Computer Reden Ist Nicht Schwer...”. Projekte Und Perspektiven Der Arbeitsstelle Für Digitale Archäologie. Köln. Bonn. Archaeol. 2013, 3, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Scriba, G.; Stockinger, U. Timeo Interretem et Dona Ferentem. On ARACHNE and the Potential and Limits of Publishing Archaeological Catalogues Online. In Proceedings of the Entre ciência e cultura: Da interdisciplinaridade à transversalidade da arqueologia. Actas das VIII Jornadas de Jovens em Investigação Arqueológica; Pinto Coelho, I., Bento Torres, J., Serrão Gil, L., Ramos, T., Eds.; CHAM: Lissabon, Portugal, 2016; pp. 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Dobreva, M.; O’Dwyer, A.; Konstantelos, L. User needs in digitization. In Evaluating and measuring the value, use and impact of digital collections; Hughes, L.M., Ed.; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2012; pp. 73–102. ISBN 978-1-85604-720-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.; Terras, M. Scholarly Information-Seeking Behaviour in the British Museum Online Collection. In Museums and the Web 2011: Proceedings; Trant, J., Bearman, D., Eds.; Archives & Museum Informatics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.; Terras, M.; Motyckova, V. Measuring impact and use: Scholarly information-seeking behaviour. In Evaluating and Measuring the Value, Use and Impact of Digital Collections; Hughes, L.M., Ed.; Facet Publishing: London, UK, 2012; pp. 85–102. ISBN 978-1-85604-720-3. [Google Scholar]

- Villaespesa, E. Who Are the Users of The Met’s Online Collection? Metrop. Mus. Art 2017. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/collection-insights/2017/online-collection-user-research (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Pandey, S.; Kumar, S. A Study of Information Seeking Behavior of Users in Rajasthani Art and Culture. Libr. Waves—Biannu. Peer Rev. J. 2019, 5, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudoin, J.E.; Brady, J.E. Finding Visual Information: A Study of Image Resources Used by Archaeologists, Architects, Art Historians, and Artists. Art Doc. J. Art Libr. Soc. N. Am. 2011, 30, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Münster, S.; Kamposiori, C.; Friedrichs, K.; Kröber, C. Image Libraries and Their Scholarly Use in the Field of Art and Architectural History. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2018, 19, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.S. The Map of Art History. Art Bull. 1997, 79, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, D. Byzantinism: The Imaginary and Real Heritage of Byzantium in Southeastern Europe. In New approaches to Balkan studies; Keridis, D., Elias-Bursać, E., Yatromanolakis, N., Eds.; Brassey’s: Dulles, VA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1-57488-724-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. The Absence of Byzantium. Nea Estia 2008, 1807, 4–59. [Google Scholar]

- Marsili, G.; Orlandi, L.M. Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage Preservation: The Case of the BYZART (Byzantine Art and Archaeology on Europeana) Project. Stud. Digit. Herit. 2019, 3, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannharter, N.; Teetor, S. Challenges of Building and Maintaining an Image Database: A Use Case Based on the Digital Research Archive for Byzantium (BIFAB). Mitteilungen Ver. Österr. Bibl. Bibl. 2017, 70, 208–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Knaus, G. Leitfaden für digitales Sammlungsmanagement an Kunstmuseen; Bracht, C., Ed.; Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte—Bildarchiv Foto Marburg; Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte, Philipps-Universität Marburg: Marburg, Germay, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIDOC CRM. Available online: http://www.cidoc-crm.org/ (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Categories for the Description of Works of Art (CDWA) (Getty Research Institute)—16. Subject Matter. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/cdwa/18subject.html (accessed on 17 November 2020).

- The Getty Research Institute. Getty Vocabularies. Available online: https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/index.html (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Metadata and Vocabularies for Archaeological Datasets—ARIADNEplus Training Hub. Available online: https://training.ariadne-infrastructure.eu/metadata-and-vocabularies-for-archaeological-datasets/ (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Sbarbati, S. About the Project. Available online: https://www.parthenos-project.eu/about-the-project-2 (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Lewis, M.J. Islam by Any Other Name: On the Met’s Reopening of the Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia. New Criterion 2011, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shalem, A. What Do We Mean When We Say ‘Islamic Art’? A Plea for a Critical Rewriting of the History of the Arts of Islam. J. Art Hist. 2012, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, W.M.K. What Is “Islamic” Art?: Between Religion and Perception; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-108-47465-8. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, N.; Robson, G.; Howard, J.B.; Manguinhas, H.; Isaac, A. Cultural Heritage Metadata Aggregation Using Web Technologies: IIIF, Sitemaps and Schema.Org. Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2020, 21, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fafalios, P.; Holzmann, H.; Kasturia, V.; Nejdl, W. Building and Querying Semantic Layers for Web Archives (Extended Version). Int. J. Digit. Libr. 2020, 21, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commare, L. Social Tagging als Methode zur Optimierung Kunsthistorischer Bilddatenbanken—Eine empirische Analyse des Artigo-Projekts. Kunstgesch. Open Peer Rev. J. 2011. Available online: https://www.kunstgeschichte-ejournal.net/160/ (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Earle, E.F. Crowdsourcing Metadata for Library and Museum Collections Using A Taxonomy of Flickr User Behavior; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA.

- Payant, A.; Skeen, B.; Arnljots, A.-M.; Williams, R. Beyond Crowdsourcing: Working with Donors, Student Fieldworkers, and Community Scholars to Improve Cultural Heritage Collection Metadata. J. Digit. Media Manag. 2020, 8, 242–253. [Google Scholar]

- Salmi, H.; Laine, K.; Römpötti, T.; Kallioniemi, N.; Karvo, E. Crowdsourcing Metadata for Audiovisual Cultural Heritage: Finnish Full-Length Films, 1946–1985. In Proceedings of the CEUR-WS Digital Humanities in the Nordic Countries Conference (DHN 2020), Riga, Latvia, 21–23 October 2020; pp. 325–332. [Google Scholar]

- Avgousti, A.; Papaioannou, G.; Gouveia, F.R. Content Dissemination from Small-Scale Museum and Archival Collections: Community Reusable Semantic Metadata Content Models for Digital Humanities. Code4Lib J. 2019, 43. Available online: https://journal.code4lib.org/articles/14054 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Riley, J. Understanding Metadata: What Is Metadata, and What Is It For?: A Primer | NISO Website; National Information Standards Organization (NISO): Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-937522-72-8. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Lee, T. Linked Data—Design Issues. Available online: https://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html (accessed on 6 January 2021).

- Linked Open Data. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/page/linked-open-data (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Haslhofer, B.; Isaac, A. Data.Europeana.Eu—The Europeana Linked Open Data Pilot. 6 October 2011, pp. 94–104. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268428958_The_Europeana_Linked_Open_Data_Pilot (accessed on 4 September 2021).

- Community—IIIF | International Image Interoperability Framework. Available online: https://iiif.io/community/ (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Broder, A. A Taxonomy of Web Search. ACM SIGIR Forum 2002, 36, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Prometheus Image Archive: High-Quality Images from the Fields of Arts, Culture and History. Available online: https://www.prometheus-bildarchiv.de/ (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Artstor. Available online: https://www.artstor.org/ (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Agapitos, P. Late Antique or Early Byzantine? The Shifting Beginnings of Byzantine Literature. Rendiconti Cl. Lett. E Sci. Morali E Stor. 2012, 146, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A. Late Antiquity and Byzantium: An Identity Problem. Byzantine Mod. Greek Stud. 2016, 40, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurković, M. Quo Vadis Late Antiquity? Quo Vadis Middle Ages? Hortus Artium Mediev. 2019, 25, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byzantine (Culture and Style). Available online: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300020669 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Clarke, M. Early Christian. In The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-19-956992-2. [Google Scholar]

- Early Christian. Available online: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300020665 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Late Antique. Available online: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300020666 (accessed on 24 August 2021).

- Kaldellis, A. Late Antiquity Dissolves. Available online: https://marginalia.lareviewofbooks.org/late-antiquity-dissolves-by-anthony-kaldellis/ (accessed on 29 December 2020).

- Roman (Ancient Italian Culture or Period). Available online: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300020533 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Renaissance. Available online: http://vocab.getty.edu/page/aat/300021140 (accessed on 25 August 2021).

- Manar Al-Athar الصفحة الرئيسية. Available online: http://www.manar-al-athar.ox.ac.uk/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Ikonen Museum: Sammlung. Available online: https://ikonen-museum.com/ikonen-museum/sammlung (accessed on 30 November 2020).

- Museo dell’alto Medioevo “Alessandra Vaccaro”. Available online: http://museocivilta.beniculturali.it/museo-vaccaro/ (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Museo Nazionale Del Bargello. Available online: https://www.bargellomusei.beniculturali.it/musei/1/bargello/ (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Barsanti, C. The Fate of the Antioch Mosaic Pavements: Some Reflections. Uludag Univ. J. Mosaic Res. 2012, 5, 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fountain Mosaic: Erotes Riding Dolphins and Fishing, Late 3rd Century A.D. Available online: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/21662 (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Digital Photo Library—Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz. Available online: http://photothek.khi.fi.it/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Photographic Collection. Available online: https://www.biblhertz.it/en/photographic-collection (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- The Photographic Collection. Available online: https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/library-collections/photographic-collection (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database. Available online: https://iconographic.warburg.sas.ac.uk/vpc/VPC_search/main_page.php (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Digital LIMC. Available online: https://www.weblimc.org/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Bildindex der Kunst und Architektur. Available online: https://www.uni-marburg.de/de/fotomarburg/recherchieren/bildindex (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Über Uns—Bildindex Der Kunst & Architektur. Available online: https://www.bildindex.de/cms/homepage/ueber-uns/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Das Projekt—Bildindex Der Kunst & Architektur. Available online: https://www.bildindex.de/cms/homepage/ueber-uns/das-projekt/ (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Europeana. Available online: https://www.europeana.eu/en (accessed on 2 November 2020).

- Europeana Pro—Our Mission. Available online: https://pro.europeana.eu/about-us/mission (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- About IDAI.Objects Arachne. Available online: https://arachne.dainst.org/info/about (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Ubi Erat Lupa—Bilddatenbank Zu Antiken Steindenkmälern. Available online: http://lupa.at (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- ACOR Photo Archive. Available online: https://photoarchive.acorjordan.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Summary—ACOR Photo Archive. Available online: https://photoarchive.acorjordan.org/about-our-collections/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Archaeological Archives. Available online: http://vrc.princeton.edu/archives/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Dumbarton Oaks Online Collections. Available online: https://www.doaks.org/resources/online-collections (accessed on 22 November 2020).

- The Digital Research Archive for Byzantium (DiFaB). Available online: https://difab.univie.ac.at/en/difab/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- BYZART—Byzantine Art Thematic Collection. Available online: https://byzart.eu/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Metadata Modelling—BYZART. Available online: https://byzart.eu/helpdesk/helpdesk-metadata-modelling (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Vocabulary—BYZART. Available online: https://byzart.eu/vocabulary (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- FOTOTHEK | FOTOTECA | PHOTO COLLECTION | PHOTOTHÈQUE: OPAC—Version 2.4.0 2007–2020 (Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max-Planck-Institut Für Kunstgeschichte, Rom)—Startseite. Available online: http://foto.biblhertz.it/exist/foto/search.html (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Jagdmosaik, S. Megalopsychia-Mosaik. Available online: https://arachne.dainst.org/entity/1376477 (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- ARIADNE: The Way Forward to Digital Archaeology in Europe. Available online: https://arachne.dainst.org/project/ariadne (accessed on 10 February 2021).

- Pamir, H. Antakya Kent İçi Kurtarma Kazıları. In Uluslararası Çağlar Boyunca Hatay ve Çevresi Arkeolojisi Sempozyumu Bildirileri, 21–24 Mayıs 2013 Antakya/The Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Archeology of Hatay and Its Vicinity through the Ages, 21–24 May 2013 Antakya; Özfırat, A., Uygun, Ç., Eds.; Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi Yayınları: Antakya, Turkey, 2014; pp. 101–114. ISBN 978-975-7989-50-9. [Google Scholar]

| Site | Browse by Time Period 1 | Browse by Search Term 2 | Number of Results | Total Number of Listed Items 3 | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Museum, London | 250–750 CE 4 | - | - | 4,500,000 | - |

| - | late antique | 1316 | 0.03% | ||

| Late Antique | - | 19,810 | 0.44% | ||

| - | byzantine | 15,909 | 0.35% | ||

| Byzantine | - | 4179 | 0.09% | ||

| - | early christian | 4455 | 0.10% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantine | 9407 | 0.21% | ||

| Cleveland Museum of Art | 250–750 CE | - | 1254 | 63,754 | 1.97% |

| - | late antique | 1 | 0.00% | ||

| - | byzantine | 275 | 0.43% | ||

| - | early christian | 32 | 0.05% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantine | 105 | 0.16% | ||

| Getty Museum, Los Angeles 5 | - | late antique | 83 | 15,7493 | 0.05% |

| - | byzantine | 564 | 0.36% | ||

| - | early christian | 80 | 0.05% | ||

| Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA 5 | - | late antique | 3 | 235,878 | 0.00% |

| Late Antique period | - | 8 | 0.00% | ||

| - | byzantine | 3319 | 1.41% | ||

| Byzantine period | - | 912 | 0.39% | ||

| - | early christian | 5 | 0.00% | ||

| Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (KHM) | 250–750 CE | - | 2974 | 23,963 | 12.41% |

| - | late antique | 3 | 0.01% | ||

| - | spätantik* | 43 | 0.18% | ||

| Spätantik | - | 27 | 0.11% | ||

| Spätantike Zeit | - | 4 | 0.02% | ||

| - | byzantine | 18 | 0.08% | ||

| - | byzantinisch* | 39 | 0.16% | ||

| Byzantinisch-provinziell | - | 2 | 0.01% | ||

| - | early christian | 3 | 0.01% | ||

| - | frühchristlich* | 6 | 0.03% | ||

| Christliche Zeit | - | 3 | 0.01% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantinisch* | 8 | 0.03% | ||

| Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | 250–750 CE | - | 2357 | 439,557 | 0.54% |

| - | late antique | 19 | 0.00% | ||

| - | byzantine | 1515 | 0.34% | ||

| - | early christian | 33 | 0.01% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantine | 440 | 0.10% | ||

| Princeton University Art Museum | 250–750 CE | - | 1617 | 55,692 | 2.90% |

| - | late antique | 323 | 0.58% | ||

| Late Antique | - | 275 | 0.49% | ||

| - | byzantine | 6120 | 10.99% | ||

| Byzantine | - | 88 | 0.16% | ||

| - | early christian | 58 | 0.10% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantine | 840 | 1.51% | ||

| Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB) | 250–750 CE | - | 17,760 | 261,679 | 6.79% |

| - | late antique | 0 | 0.00% | ||

| - | spätantik* | 14 | 0.01% | ||

| - | byzantine | 278 | 0.11% | ||

| - | byzantinisch* | 2530 | 0.97% | ||

| - | early christian | 2 | 0.00% | ||

| - | frühchristlich* | 141 | 0.05% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantinisch* | 934 | 0.36% | ||

| The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (MET) 5 | A.D. 1–500 6 | - | 6209 | 406,000 | 1.53% |

| - | late antique | 310 | 0.08% | ||

| - | byzantine | 3153 | 0.78% | ||

| - | early christian | 269 | 0.07% | ||

| A.D. 1–500 6 | byzantine | 448 | 0.11% | ||

| Victoria and Albert Museum, London | 250–750 CE | - | 4582 | 1,230,805 | 0.37% |

| - | late antique | 529 | 0.04% | ||

| - | byzantine | 1067 | 0.09% | ||

| - | early christian | 280 | 0.02% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantine | 210 | 0.02% |

| Site 1 | Browse by Custom Date Range | Number of Results | Total Number of Listed Items | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Museum of Art | 250–750 CE | 1254 | 63,754 | 1.97% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 202 | 0.32% | ||

| 1400–1600 CE | 7169 | 11.24% | ||

| Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (KHM) | 250–750 CE | 2974 | 23,963 | 12.41% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 5541 | 23.12% | ||

| 1400–1600 CE | 4062 | 16.95% | ||

| Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | 250–750 CE | 2357 | 439,557 | 0.54% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 9935 | 2.26% | ||

| 1400–1600 CE | 8474 | 1.93% | ||

| Princeton University Art Museum | 250–750 CE | 1617 | 55,692 | 2.90% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 1183 | 2.12% | ||

| 1400–1600 CE | 2146 | 3.85% | ||

| Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB) | 250–750 CE | 17,760 | 261,679 | 6.79% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 21,123 | 8.07% | ||

| 1400–1600 CE | 13,528 | 5.17% | ||

| Victoria and Albert Museum, London | 250–750 CE | 1725 | 1,239,668 | 0.14% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 24,825 | 2.00% | ||

| 1400–1600 CE | 55,845 | 4.50% | ||

| Sum all museums | 250–750 CE | 27,687 | - | - |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 62,819 | |||

| 1400–1600 CE | 91,224 |

| Site | Browse by Time Period 1 | Browse by Search Term 2 | Number of Results | Total Number of Listed Items 3 | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACOR Photo Archive (images) | - | late antique | 978 | 30,789 | 3.21% |

| byzantine | 3895 | 12.65% | |||

| early christian | 203 | 0.66% | |||

| Arachne (objects) | spätantik | - | 1362 | 3,933,071 | 0.03% |

| - | spätantik* | 18,662 | 0.47% | ||

| byzantinisch | - | 280 | 0.01% | ||

| - | byzantinisch* | 7816 | 0.20% | ||

| frühchristlich | - | 270 | 0.01% | ||

| - | frühchristlich* | 1526 | 0.04% | ||

| Bibliotheca Hertziana 4 (images) | - | late antique | 0 | 391,390 | 0.00% |

| spätantik* | 44 | 0.01% | |||

| tardo antico | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| antique tardive | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| byzantine | 2 | 0.00% | |||

| byzantinisch* | 688 | 0.18% | |||

| bizantin* | 53 | 0.01% | |||

| early christian | 4 | 0.00% | |||

| frühchristlich* | 175 | 0.04% | |||

| paleocristian* | 8 | 0.00% | |||

| Bildindex (objects) | 250–750 CE | - | 6829 | 1,825,568 | 0.37% |

| - | spätantik | 218 | 0.01% | ||

| - | byzantinisch | 1738 | 0.10% | ||

| 250–750 CE | byzantinisch | 165 | 0.01% | ||

| - | frühchristlich | 159 | 0.01% | ||

| Digital LIMC (objects) | - | late antique | 8 | unknown | unknown |

| byzantine | 1 | ||||

| early christian | 3 | ||||

| Europeana 5 (images) | - | late antique | 1742 | 52,025,992 | 0.00% |

| - | spätantik* | 861 | 0.00% | ||

| - | byzantine | 88,151 | 0.17% | ||

| - | byzantinisch* | 80,299 | 0.15% | ||

| Byzantine Art 6 | - | 75,895 | 0.15% | ||

| early christian | 1734 | 0.00% | |||

| frühchristlich* | 379 | 0.00% | |||

| KHI Photothek (objects) 7 | - | spätantik | 2 | 68,646 | 0.00% |

| byzantinisch | 101 | 0.15% | |||

| frühchristlich | 2 | 0.00% | |||

| Manar al-Athar (images) | - | late antique | 44 | 77,955 | 0.06% |

| byzantine | 174 | 0.22% | |||

| early christian | 0 | 0.00% | |||

| Princeton Archaeological Archives (images) | - | late antique | 0 | 10,366 | 0.00% |

| byzantine | 87 | 0.84% | |||

| early christian | 57 | 0.55% | |||

| Ubi Erat Lupa 8 (images) | spätantik | - | 314 | 31,903 | 0.98% |

| - | spätantik* | 502 | 1.57% | ||

| byzantinisch | - | - | - | ||

| - | byzantinisch* | 3 | 0.01% | ||

| frühchristlich | - | 526 | 1.65% | ||

| - | frühchristlich* | 564 | 1.77% | ||

| 250–750 CE | - | 1401 | 4.39% | ||

| WI-ID (images) | 3rd–8th century | - | 1130 | 105,880 | 1.07% |

| - | late antique | 472 | 0.45% | ||

| - | byzantine | 413 | 0.39% | ||

| 3rd–8th century | byzantine | 10 | 0.01% | ||

| - | early christian | 28 | 0.03% |

| Site | Focus | Browse by Custom Date Range | Number of Results | Total Number of Listed Items | Share |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bildindex (objects) | Art History | 250–750 CE | 6931 | 1,833,228 | 0.38% |

| 1400–1600 CE | 225,746 | 12.31% | |||

| Ubi Erat Lupa (images) | Archaeology | 250–750 CE | 1401 | 31,903 | 4.39% |

| 27 BCE–249 CE | 10,073 | 31.57% | |||

| WI-ID (images) | Art History | 3rd–8th century | 1130 | 105,880 | 1.07% |

| 15th–16th century | 48,984 | 46.26% |

| No. | Proposed improvement |

|---|---|

| 1 | Addition of a customizable (numerical) date filter. |

| 2 | Optimization of existing metadata to account for different search strategies. |

| 3 | Translation of metadata entries on multilingual repositories. |

| 4 | Addition of sufficient metadata entries regarding materials, subject matter and further relevant details to improve informational searches. |

| 5 | Collaboration with scholars from different, especially less prominent, fields of art history and archaeology, to improve ontologies and metadata practices. |

| 6 | Inclusion of recently excavated and published material, perhaps by allowing scholars to make submissions to an online repository. |

| 7 | More transparency in respect of implemented metadata standards and ontologies. |

| 8 | Better collaboration between different repository providers to agree on major standardized search filters. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Decheva, P. Trace the Untraceable: Online Image Search Tools for Researching Late Antique Art. Heritage 2021, 4, 4076-4104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040225

Decheva P. Trace the Untraceable: Online Image Search Tools for Researching Late Antique Art. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):4076-4104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040225

Chicago/Turabian StyleDecheva, Prolet. 2021. "Trace the Untraceable: Online Image Search Tools for Researching Late Antique Art" Heritage 4, no. 4: 4076-4104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040225

APA StyleDecheva, P. (2021). Trace the Untraceable: Online Image Search Tools for Researching Late Antique Art. Heritage, 4(4), 4076-4104. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040225