1. Introduction

The success of a region-wide project to connect historic buildings, monuments, and archeological sites, in the context of “cultural routes”, can be catalytic in the successful development of Cultural Tourism [

1], proving that funding the preservation of our architectural and cultural heritage is a high-yield investment, able to finance further projects on its own, within a Circular Economy.

The promotion and utilization of historic buildings, monuments, and archaeological sites, as the core element of cultural tourism, should not be accomplished through an arbitrary and fragmented approach. Neither should be approached merely from the point of preservation of our Cultural Heritage as a societal obligation. Instead, the preservation, protection, and sustainability of the cultural heritage assets and the values they represent [

2] should be dynamically interlinked with the socio-economic development of the region examined. Thus, the relevant studies and conservation and rehabilitation works should be performed within an integrated management program, in order to optimize the utilization of available financial and technical resources and maximize their impact on the cultural tourism product and regional development.

Cultural heritage and to a lesser degree natural heritage are often perceived by tourists as one of the reasons to visit an area or a region, but often not the main one. The contribution of cultural heritage in formulating the “brand” of an area or a country does not solely depend on the quality and quantity of its cultural heritage assets, but on the other available touristic attraction elements. The island of Ibiza, for example, well known for its association with nightlife, electronic dance music, and the summer club scene, is also an UNESCO World Heritage Site; it is doubtful that the millions of tourists visiting the island concentrate mainly on its natural or cultural heritage. To a large degree, this is also the case with Greece, especially the Greek islands, which is arguably perceived as a cheap, sun-sea destination, although with important cultural heritage; the majority of tourists influx, nonetheless, regards the sun-sea product rather than the cultural content of their vacation.

The distinction between the cultural and the recreation elements of tourist vacations is not always clear, nor desirable. Certainly, in European cities (e.g., Rome, Paris, Berlin, Madrid) with important architectural and cultural heritage and large museums, the cultural element is stronger, whereas in other areas (e.g., coastal areas in the Mediterranean Sea, mountain resorts) the recreational element of the vacations is instead stronger. The recreational element strongly influences tourism seasonality [

3].

The strategies and the strategic directions for each region are set by the National Strategic Reference Framework for the Tourism Sector [

4]. In the case of Greece, in particular, there is observed an obvious imbalanced distribution of the tourist product. A few renowned islands (e.g., Rhodes, Crete, Corfu, Mykonos, Santorini) function as very popular summer tourist destinations. Emblematic Greek cities such as Athens, with a strong archaeological footprint (Acropolis of Athens, Ancient Agora, National Archaeological Museum, etc.) have, instead, a balanced cultural-recreational tourist product, acting either as the main destination or as an important transient station. However, neither of the above is readily applicable in rural areas that do not adhere to the concept of a sun-sea style tourism. These areas have limited and non-competitive tourist products. This is the case of the rural area of Aitoloakarnania, in Western Greece, for which this work discusses the applicability and benefits of cultural routes as a tool for the region’s development efforts.

Specifically, despite the existence of important touristic attractions in Aitoloakarnania, such as important cultural heritage assets spanning from antiquity to modern times, important natural heritage (Messolongi-Aitoliko lagoons complex, Acheloos and Amvrakikos Rivers, Trichonida Lake, etc.), and extensive shoreline with high-quality accessible beaches, the region has limited tourism activities, that arguably do not reflect its potential. This is exemplified by the rather small number of hotel units (78) and their small total capacity (1901 rooms/3619 beds), according to recent data from the Hellenic Chamber of Greece [

5]. Even more characteristic is the distribution of the ratings of the hotels, with no 5-star hotel being available in the region, seven 4-star hotels, thirty-six 3-star hotels, twenty-four 2-star hotels, and one 1-star hotel, according to records. This distribution of hotel ratings reflects both the level of tourism as well as the tourism product value. Such a “discrepancy” between the potential for touristic development and the actual touristic influx must be analyzed in the framework of regional development strategies to remedy the current situation.

In this context, the regional unit of Aitoloakarnania can act as a use-case where an underdeveloped region which, nonetheless, has significant development potential, may be able to fruitfully and sustainably exploit its cultural and natural heritage assets in order to support an overall development effort that preserves the region’s values, history, and natural environment.

However, the region’s development approach should not be just a recurrence of similar development cases of other regions or areas in Greece or in the greater Mediterranean Sea area [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], but instead should be adapted to the needs and capacity of the Aitoloakarnania region. In parallel, it should “learn” from mistakes of the past from other cases that demonstrated touristic over-development or destruction of the character of an area due to the “wrong-type” of tourism influx and products [

8,

9,

10]. In this context, the region of Aitoloakarnania, at the level of regional and local authorities and inhabitants, does not aim to base its development model solely on tourism (as for example in the case of certain islands of the Aegean Sea) [

7,

10,

13] but instead integrate cultural tourism in an overall development scheme that includes other resources and priorities [

14,

15].

This work aims to propose cultural roads, within the context of cultural tourism, in an underdeveloped region, with limited financial and technical resources available, while preserving the character and history of the region, and while adhering to the principles of the circular economy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultural Heritage Management According to the Principles of Circular Economy

The integrated protection and management of a region’s cultural assets depends on many factors and requires an interdisciplinary approach. From urban planning to the sustainable management of the built environment, proper planning is a prerequisite to addressing societal interests and priorities. The spatial planning and decision-making for a circular economy are, to a large extent, a regulator of the success of such a venture [

16]. Construction of new infrastructures or maintenance/upgrade of existing infrastructures must conform to the boundaries and aims set by integrated municipal or regional urban plans. In turn, this requires a clear definition of area and land use that takes into account and protects the sensitive structures and sites of cultural heritage.

To this effect, the management of the existing technical and social infrastructures, as well as the management of the municipal and community property, can be carried out in terms of a circular economy. The application of circular economy methods in management aims to extend the life cycle of structures and their building materials, improve construction and maintenance techniques of the building assets and infrastructures of the municipality and upgrade their designs [

16]. The benefits of circular management are cost savings, utilization of existing infrastructure and buildings, and maximization of the value of materials and resources. The management of building assets and infrastructures traditionally requires significant funding and technical resources to keep them safe, up-to-date, and operational. In circular management, emphasis is given to the design that will reduce costs and environmental footprint. In order to carry out the circular design, both for new constructions and for the maintenance and repair of older ones, the flows (materials, resources, products, etc.) must be recorded in detail and evaluated economically on a macro-scale. Thus, the design leads to the creation of more durable and modular structures and to the minimization of maintenance requirements in the future.

Although the above may initially sound irrelevant or non-feasible to cultural heritage assets—which mainly regard existing structures and buildings designed and constructed centuries ago—in reality, the principles of circular economy, within the context of local or regional development, are applicable. The protection of built cultural heritage entails conservation, maintenance, strengthening, and rehabilitation interventions utilizing compatible and performing materials and techniques subject to the same principles of circular economy as those for new constructions.

In order to exploit the benefits of a circular economy, the reveal, restoration, and reuse of cultural and environmental assets should be integrated into the plan of each region’s development. The Helsinki Declaration of 1996 on the political dimension of Cultural Heritage conservation recognized cultural heritage as an economic factor for local development, and thus the need to include it in activities and policies for sustainable development [

17]. Moreover, it identified the need for cross-sectoral strategies and balanced utilization of cultural heritage for touristic development, through close cooperation between the private sector and the government authorities. The Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society, at Faro 2005 [

18], further emphasized that the conservation of cultural heritage and its sustainable use have human development and quality of life as their goal. It was recognized that all processes of economic, political, social, and cultural development and land-use planning, should take into account cultural heritage impact assessments and adopt mitigation strategies where necessary. The sustainable use of the cultural heritage necessitates respect of its integrity and special character and ensuring that decisions about changes entail an understanding of the cultural values involved. Within this framework, cultural heritage can act as a beneficial factor of sustainable economic development when the economic potential of cultural heritage is fully realized by the general public, the relevant authorities, and private investors.

The main challenge for authorities, stakeholders and the scientific community is how to ensure the preservation of cultural heritage while enhancing its accessibility and sustainable utilization for development purposes. This is accomplished by the adoption of cultural heritage assets management processes that reflect the three main scales of management [

19].

At the macro-scale, the management of cultural heritage is performed by the government (Ministry of Culture, etc.) providing the institutional framework, high-level strategies, and country-wide planning for activities and interventions relevant to the protection, preservation, and utilization of cultural heritage.

At the mesoscale, the role of regional authorities is enhanced. They provide human and financial resources more focused on the protection and utilization of cultural heritage assets that can contribute to regional development while conforming to the regulation, strategies, and planning set by the central governmental authorities. This is achieved by the inclusion of cultural heritage assets in the regional spatial plans, not just as limiting factors but rather as crucial elements and focal points of these plans. The mesoscale also regards the creation and active adoption of strategies for the beneficial use of cultural heritage assets, which establish and support the economic attributes of cultural heritage within the framework of cultural tourism. Regional plans for cultural heritage are then developed for the sustainable management, preservation, maintenance, and rehabilitation of regional cultural heritage assets. These assets relate to the region’s cultural heritage (monuments, historic buildings and structures, and archaeological and historic sites), natural heritage (natural features and sites, e.g., mountains, rivers, lakes, forests, coastlines, etc.), and cultural landscapes (designed landscapes such as parks and artificial lakes, organically evolved landscape resulting from the interaction between society and the environment), and associative cultural heritage (landscapes of religious or traditional importance, e.g., emblematic mountains, rivers, and religious sites) [

20].

At the local scale, the management of cultural heritage assets is bestowed to local communities and authorities. Such local management relates to the appropriate tools and measures utilized by local authorities in order to merge the protection and reveal of the cultural heritage of the local community with the requirements and strategies set for the community’s socioeconomical development. It involves documentation of all cultural heritage assets, at a local scale, a preliminary identification of their interrelationships, and a comprehensive clarification of their legal status. It also requires the preparation of assessment reports for the state of preservation of the cultural heritage assets and strategic plans for the fusion of the cultural heritage assets’ usage or even adaptive reuse with the socioeconomic capacity and priorities of the community.

The adoption of the integrated management of cultural heritage is arguably more necessary in the case of underdeveloped regions and rural areas. These have experienced detrimental pressure from abandonment due to the migration of population and concentration of socioeconomic activities into other large urban areas. This “drainage” of human and financial resources is functioning in a “vicious circle” approach. Rural structures, infrastructure, and landscapes are abandoned due to technological developments and different market needs which the region or area cannot address or sustain. Funding becomes more difficult to attain and even if it becomes available it is channeled to more immediate needs than the preservation and rehabilitation of cultural heritage. The subsequent diminishing of the cultural identity of the region further weakens its resilience to the ever-increasing pressures from an evolving socioeconomic environment.

The situation for underdeveloped regions and areas can be reversed if society and the relevant authorities realize the importance of cultural heritage and the role it can play in the strategic regional and local revitalization plans. Cultural heritage assets can provide landmarks and centers of local and economic development and be transformed into poles of interest for the enhancement of Tourism [

21]. The presence of such “attractions” will augment the regional and local tourism infrastructure (small hotels, houses for rent, restaurants, markets, craft shops, art galleries, etc.), which in turn will stop the migration drainage, create job opportunities, and improve the quality of life at a regional and local scale. This impact is even stronger in underdeveloped regions, where the small and medium-sized tourism accommodation enterprises (SMTE) are dominant. In these regions, the touristic influx is not primarily controlled by organized large tour operators (which generally prefer adequately sized tourism accommodation enterprises and well-established tourist destinations), but instead is largely driven by the “brand name” of the region and the capabilities of the SMTEs to sustain and serve the tourist influx [

22]. The active utilization of cultural heritage assets can lead to the creation of more opportunities for the local community, the attraction of investments (usually related to the touristic sector, but also to Innovation). Within this context, cultural heritage may also be related to the local environment protection plan or local tourism development strategy as well as to the encouragement of entrepreneurship [

23]. Entrepreneurship has a significant impact in rural and underdeveloped areas [

24]. Due to the limited resources in rural areas, at least compared with urban regions or destinations with well-established tourist products, entrepreneurship focusing on small and medium-sized enterprises present an increased likelihood of being successful. In parallel, SMEs are more attractive for local inhabitants, compared to larger enterprises, as they generally offer a working environment more closely relevant to the local traditions and quality of life. An entrepreneurship that is focusing on the sustainable creation and operation of SMEs in rural or underdeveloped regions can be introduced easier to the principles of circular economy and exploit its benefits since it is largely based on sustaining and supporting the local and regional societal matrix.

In order to implement such integrated plans, funding needs to be provided. This is often limited in cases of underdeveloped regions or areas, which do not often attract the interest or the efforts of the central government. In such cases, the role of regional and local authorities is critical, as they are called upon to search for and provide the necessary funds, not only for the development plans but also for the protection and sustainability of the region’s cultural heritage assets. This process involves many stakeholders within the public, private and non-government sectors [

25]. In fact, public-private partnerships (PPP) emerge as indispensable funding tools to achieve ambitious development plans. However, PPPs must address long-standing societal “concerns” regarding the involvement of the private sector in the field of cultural heritage protection, which is widely accepted by the general public to be an “ethical obligation” of our Society to future generations. Therefore, it is essential for stakeholders to disseminate and communicate to the general public the benefits and necessity of PPPs for the protection of cultural heritage within an overall development scheme. Such an approach will strengthen the participation of Society in these strategic plans and ensure that their implementation is embraced by the local communities.

2.2. Cultural Routes in Underdeveloped and Rural Areas

Cultural routes have long been utilized as an effective development tool to promote a country’s or a region’s cultural heritage. At the European level, The Council of Europe, in the framework of strengthening the common European cultural identity, initially promoted exhibitions of European works of art through specially designed European programs. This was a means of supporting the idea that Europe, despite its diversity, has a common heritage. The

Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe program was launched in 1987 [

26]. The first application was the Declaration of Santiago de Compostela pilgrim routes. The cultural routes function as an institutional tool for the promotion of the rich and diverse heritage of Europe, by bringing people and places together in networks of shared history and heritage. Currently, there exist 45 certified

Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe. They actively promote human rights, cultural diversity, intercultural dialogue, and mutual exchanges across borders, and offer the framework for responsible tourism and sustainable development. The participating areas and cities in these networks are involved in activities and projects that promote co-operation in R&D, preserve the European heritage, facilitate cultural and educational exchanges, enable cross-border contemporary cultural creation, and support cultural tourism. As a result, these cultural routes act as a model of cultural and tourism management at transnational levels, and as the means for the realization of synergies of various European authorities and stakeholders.

Following the international recognition and on the occasion of the proposal of Spain in 1993 to include the Pilgrimage Route of Santiago de Compostela in the UNESCO World List, a scientific discussion began at the international level, at the initiative of the International Council of Monuments and Sites-ICOMOS, in order to: define the concept of cultural routes as a distinct category of cultural goods; highlight the methodology and criteria for the recognition of a cultural route; organize the basic mechanisms for the investigation, documentation, protection, and promotion of cultural routes; establish the necessary conditions for research and recognition of cultural routes at national and international level [

27].

Through their successful implementation during the past decades, the cultural routes and their heritage content were connected with the tourism sector through various tourism programs in many European countries. In this way, the cultural route is nowadays perceived as a tourist “product” [

28]. As an attractive tourist product, cultural routes offer the “medium” to respect the social and environmental matrix of an area, relative autonomy to the visitor, and a tour with little or no use of organized tourism services. Of interest to underdeveloped or rural areas is the trend/criterion for cultural routes to include accommodation units that must be small in capacity, and local operators, so that the economic benefits remain in the local communities.

Cultural routes and cultural tourism are interconnected and complementary concepts because cultural routes are institutional tools for the development and promotion of cultural tourism, whereas cultural tourism acts as the utilization and beneficial exploitation framework of cultural heritage [

29]. Additionally, cultural routes are one of the most widespread management tools for the development of cultural tourism and offer a predetermined course (visit) to monuments of natural and cultural heritage, within a defined thematic, historical, or conceptual context.

Cultural routes highlight the heritage of an area or a region by means of a journey through space and time. Based on the international and in particular European experience, cultural routes typically provide a complete agenda that covers the needs and interests of a wide range of visitors. The wide range of interests of visitors should not be considered a challenge, but instead, an implementation advantage in order to attract a large number of visitors. International and national experience have demonstrated that when cultural routes focus on limited aspects of cultural heritage (e.g., religious assets), the area generally attracts visitors only with relevant interests (e.g., pilgrims), often hindering other visitor groups (e.g., youth).

In this framework, it is important for regional and local development strategies to identify early in the design process the “target” groups that are considered relevant to the regional cultural routes. Depending on the cultural heritage of a region or an area, various historic periods can be covered, spanning from antiquity to modern times. In reality, only a few established heritage sites and cities (e.g., Rome) offer such an abundance of cultural diversity that can address a wide range of interests.

In the case of underdeveloped or rural regions, the situation becomes more challenging, due to the typical lack of infrastructure and limitations to accessibility. Even if a region presents significant heritage assets (e.g., archaeological sites), these—with a few exceptions—are typically not well organized to sustain extensive numbers of visitors. Often, when a heritage site experiences a limited number of visitors, the relevant central authorities (Ministries, government) are reluctant to “invest” significant financial resources to sustain and develop these sites, despite their historic importance. This is arguably a pragmatic approach, especially in countries like Greece with a wealth of cultural heritage assets but with very limited financial resources to address all the emerging needs for their protection and promotion. For underdeveloped and rural areas this is indeed a “vicious circle” situation, where they cannot fully utilize their heritage due to a lack of adequate funding, which in turn is not available due to the limited state of organization and exploitation of the region’s heritage assets.

One approach to remedy this situation, as well as to address a wider “audience”, is to include many points of interest in cultural routes, of varying states of preservation, organization, and importance, covering various historic periods, through time and space. In due time, as the cultural routes contribute to the region’s development and funding becomes more available, those points of interest that attract the most visitors and have the largest impact on the local economy and social coherence are the ones that are prioritized for comprehensive protection, preservation, and further revealing their values. Although such an approach may be perceived as “market-driven”, in the sense that it reacts to the needs of the visitors, in reality, it is just a pragmatic approach focusing on maximizing the beneficial impact of cultural routes to the regional development. Once the cultural routes generate enough income for the regional and local societies, focused interventions and preservation works can be implemented to the remaining heritage assets to increase their “attractiveness” to visitors of the cultural routes, but most importantly to preserve the cultural heritage of the region in its entirety. This pragmatic approach is in fact a gradual approach, coherent to the capacities and traditions of the local societies, without the need for and associated risks of significant investments.

The impact of this gradual approach in the design of cultural routes in underdeveloped or rural regions and areas can be increased through the focused use of technology and innovation. Technology and innovation “infusion” can be arguably easier in the case of cultural routes of underdeveloped areas, as compared to well-established popular touristic areas and cultural routes. For example, in the Medieval City of Rhodes, Greece, visitors expect to experience a well-preserved medieval fortifications complex, with a live old city, supported by high-level infrastructure (hotels, restaurants, international airports, etc.) within the old and the modern city of Rhodes. The strong medieval character of the City of Rhodes is supplemented by other important heritage assets in the vicinity (e.g., Acropolis of Rhodes, Acropolis of Lindos), whereas the visitors’ experience is additionally supported by significant leisure infrastructure (e.g., beaches) and a lifestyle attractive to many types of visitors (ranging from the very wealthy visitors to the budget-conscious tourist). Within this well-established cultural route, visitors expect to see rather well-preserved monuments and architectural assets pertinent to the culture of the city. In this framework, virtual tours, or IT solutions such as AR reconstructions may be less attractive to tourists that expect and can actually visit the monuments first-hand, fully incorporated into the character of the city. Instead, an isolated archaeological site which mostly consists of ruins, along a cultural route in an underdeveloped area, has a higher potential for technology and innovation infusion, as it can benefit more from technological solutions that can supplement and augment the visitors’ otherwise limited experience and attractiveness. Therefore, Technology infusion should be taken into account during the design phase of a cultural route in an underdeveloped or rural area, as it can allow the addition of points of interest that would otherwise seem unsuitable for inclusion into the cultural route. Moreover, technology and innovation present improved “value-for-money” as compared to traditional resource-intensive activities such as comprehensive protection interventions of heritage assets, or construction of significant infrastructures (e.g., transportation network, accommodation ecosystem, museums). Combined with the increased importance of social media, the infusion of technology and innovation can function as a reliable alternative to heavy-investment solutions for the creation of a cultural route and the corresponding development of the region.

Based on international and European experience, the development of cultural routes tailored to the needs and the capacity of underdeveloped or rural regions and areas should be implemented through a gradual approach.

The initial stage regards the design of the cultural routes, which is achieved through the preparation of initial strategy documents, optimized after public consultation through social participation, and approved by the relevant regional authorities.

The second stage regards the creation of an integrated cultural route program that includes the limited/ad-hoc upgrading and/or addition of the required infrastructure (e.g., interventions to heritage assets, accessibility enhancement activities, operational issues) according to the resources available to the underdeveloped or rural region; the development and implementation of marketing and IT activities; the fostering of the participation of entrepreneurship, through the creation of local or regional enterprise clusters in order to blend the cultural route with the regional and local economic activities.

The third stage regards the operation/exploitation of the cultural route product through the establishment and operation of a dedicated cultural route management organization that coordinates activities with regional and local authorities, end-users, and other stakeholders.

Through the above gradual approach, the development and successful operation of cultural routes can be feasible even for regions with limited resources, as they need not involve upfront significant financial and human resources, instead of remaining within their own priorities, capacities, and development goals.

2.3. Methodology

The methodology is based on the necessity for the development of a cultural route that is not only tourist/entrepreneurship oriented but also includes in its core conception an Integrated Environmental Management for the Protection of Monuments and Sites. As will be described further below for the case of the prefecture of Aitoloakarnania, a crucial stage regards the assessment of the cultural heritage ecosystem, its relation to the environment (natural and socioeconomic), and its state of preservation. The achievement of systematic documentation is based on the utilization of integrated documentation protocols [

30,

31] that follow the classification in two levels of increasing analysis and deepening of information, covering all scales of each monument (micro-scale, medium-scale) and its state of protection (monitoring-diagnosis-interventions).

The methodology encompasses quality control principles for data collection, documentation, and management. The documentation protocols contain information relevant to the life cycle of a heritage asset: (a) general information and documentation of topography (b) history of the asset and its surroundings (c) architectural values and importance of the asset (d) type and distribution of building materials (e) structural issues (f) evaluation of the asset’s state of preservation through integrated diagnostic studies and analysis of degradation mechanisms (g) assessment of risk indicators (h) documentation of past preservation interventions and evaluation of their effectiveness. The data collection is supplementally accomplished through a literature survey, on-site observations, and tests/measurements as well as through cooperation with local bodies and the local authorities.

In the case of the prefecture of Aitoloakarnania, the natural environment of the prefecture and the special character and importance of its rivers and coasts (that have defined to a large degree the region’s history), in combination with the high density and variety of the cultural and environmental reserve led to the selection of specific riverside, lakeside, and coastal cultural routes. This option ensures the simultaneous revealing of the natural and cultural environment and elucidates the “dialogue” and interrelationship between the region’s distinct natural environment and its cultural heritage. It includes a variety of points of interest while at the same time it is a mild, low-cost intervention, easily implemented by demarcating local accesses (using the existing road network) and appropriate information points. The selected points of interest were captured on maps depicting the proposed cultural routes.

The “balance” between emphasizing a region’s cultural reserve and its natural environment is obviously case-specific. However, it can follow certain general guidelines:

Extreme emphasis on either character (cultural heritage or natural heritage) may be avoided in the design of cultural routes since it may fully “exclude” certain categories of visitors.

The cultural assets and the natural heritage areas of interest should be somehow connected through a “continuum concept”, i.e., a continuous path that reveals information about the history of a region and highlights its evolution through time. The importance of the sites for the region should be well-described.

The dialogue between cultural heritage and the natural environment should be clear and adequately presented through the selection of the appropriate points of interest.

Cultural or natural heritage assets should be adequately accessible in order to maximize visitors’ experience.

The points or sites of interest along a cultural route should be selected such that they do not require prolonged visits.

A cultural route should be supported by appropriate accommodation and food services facilities along the route.

The cultural heritage or the natural heritage points of interest should function as alternative/equivalent focal points. For example, a monastery within a forest area may function as the main focal point for pilgrims, with the natural environment acting as a “secondary” attraction; alternatively, the forest area may function as the main focal point for naturalists, with the monastery acting as a secondary point of interest.

Entrepreneurship and local business should adapt to the local character of the cultural route, attending to the needs of the travelers while promoting the regional and local heritage and traditions. For example, enterprises around a monastery or a religious site should adapt the services they provide to cater to the needs of pilgrims. Similarly, enterprises around a river or a lake should provide services that allow visitors to experience the beauty of the scenery and the natural environment.

The balance between cultural heritage and natural heritage may be seasonal. For example, rural areas that include sites that are of interest to winter tourism (e.g., ski resorts), or summer tourism (e.g., seaside enterprises) should design the cultural route in such a way that the points along the routes are complemental to allow the operation and visitor attraction of the route on an annual basis. The balance, thus, can shift accordingly, in order to address the seasonality of the route.

The utilization of the cultural and architectural heritage at the regional and local levels can be achieved by creating and promoting cultural tourism routes connecting properly selected roads, with the parallel maintenance-restoration of characteristic monuments and archeological sites, along these cultural routes, which can be visited and contribute to the overall touristic product as well as directly influence the socio-economic development of the region.

3. The Case Study of Aitoloakarnania

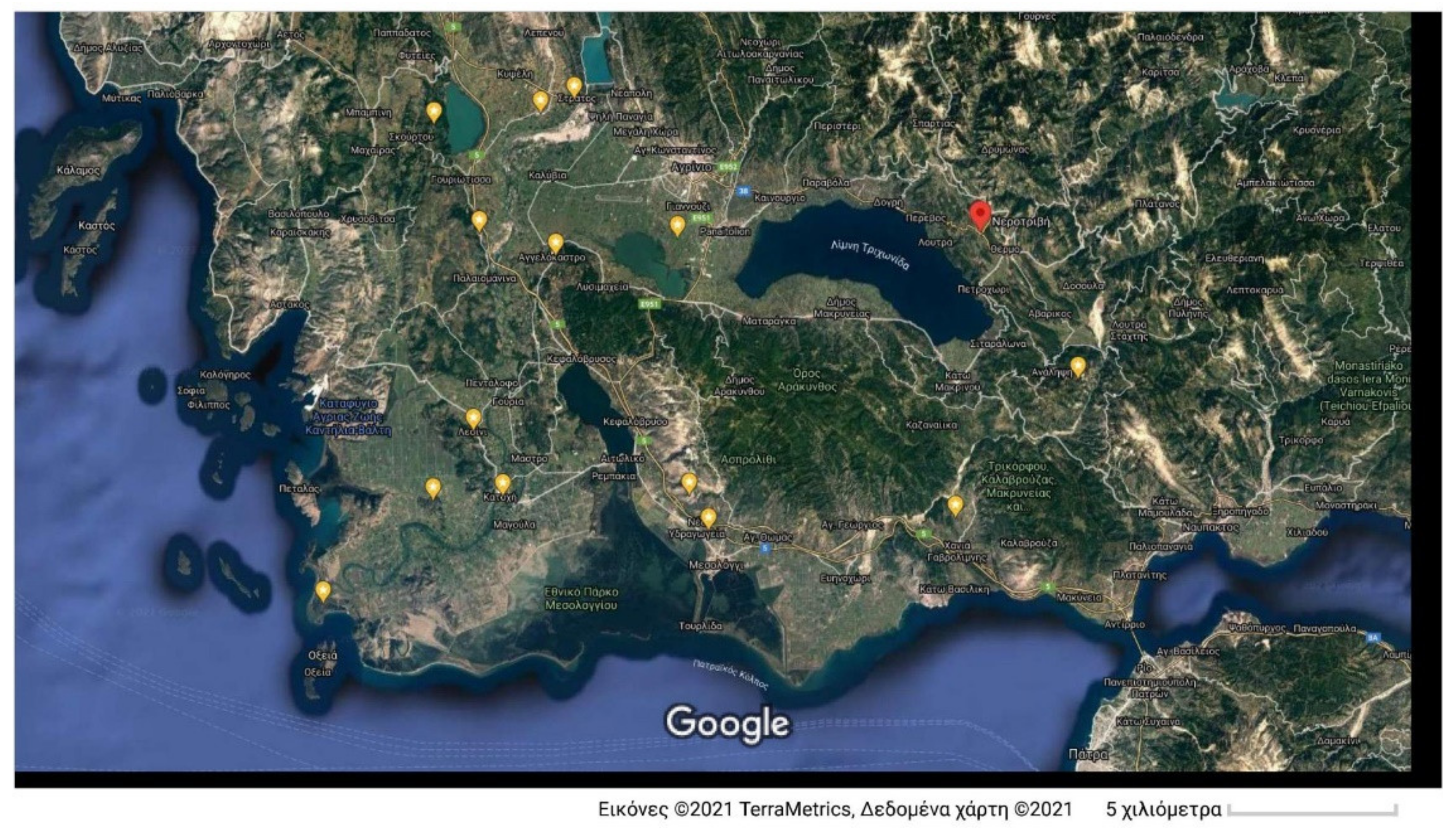

The regional unit of Aetolia-Acarnania (Aitoloakarnania) in Greece, is a combination of the historical regions of Aetolia and Acarnania. It is currently the largest (5.423 km2) regional unit in Greece and is located in the western part of the country. According to the 2020 census of the National Statistical Service, it has a population of 228.069 or 2.3% of the total population of the country. As a result, Aitoloakarnania presents one of the lowest population densities in Greece. The capital of Aetolia-Acarnania is Messolonghi for historical reasons (historic city of the Greek Independence Revolution), whereas its largest city and economic center is Agrinio.

The region of western Greece and in particular Aitoloakarnania has historically acted as a crossroad connecting Peloponnese and Attica with the region of Epirus and Europe. Although the port of Patras, at Peloponnese, plays a crucial role in the transfer of goods to the Adriatic Sea and Europe, the region of Aitoloakarnania is influential in the surface transfer of people and goods to Europe. As a result, Aitoloakarnania was mainly regarded as a transit region as compared to the nearby region of Achaia in Peloponnese and the important port of Patras. The construction (2004) of the Rio-Antirrio Bridge, one of the world’s longest multi-span cable-stayed bridges and longest of the fully suspended type, over the Gulf of Corinth near Patras, provides a crucial and effective link between the region of Peloponnese and the region of Aitoloakarnania. The associated construction of the A5 highway that connects Patras (through the Rio-Antirrio Bridge) with Ioannina and then further to the north through Albania with Europe, has evolved into an effective alternative route from the mega-urban city of Athens towards Europe, compared to the path through central Greece. This infrastructure, however, has enhanced even more the “transient” character of the Aitoloakarnania region, without fully exploiting the infrastructures’ development potential.

The economy of Aitoloakarnania, largely agricultural, is one of the poorest regional economies in Greece. It is significantly influenced by the geography of the area. The area is characterized by a flat and fertile coastal region, but a mountainous interior. The Panaitoliko mountains and the Acarnanian mountains dominate the interior area. The Messolongi-Aitoliko lagoons complex, located in the southwest part of the region is protected by the Ramsar Convention and is also included in the Natura 2000 network. The Trichonida natural lake, the largest lake (95.8 km2) in Greece, and the Kremasta artificial lake (80.6 km2) and the region’s two main rivers, Acheloos and Evinos, significantly influence the geography of the Aitoloakarnania.

The coastal cities of Nafpaktos, Messolonghi, and Vonitsa have experienced important development based on Tourism. However, the interior of Aitoloakarnania has yet to develop significant touristic infrastructure. In this framework, Cultural Tourism emerges as an excellent tool to exploit the region’s historic areas, cities, and sites and diminish the development gap between its interior and its coastal areas.

It is important for the region to utilize its environmental and cultural assets [

32,

33,

34], in order to fill the gaps of de-industrialization and to strengthen the competitiveness of the region in terms of convergence of its internal inequalities. The utilization of the cultural and architectural heritage of Aitoloakarnania can be achieved by the mapping, identification, and promotion of cultural tourism routes on the coastal and riverside axes, as well as by the parallel maintenance-restoration of characteristic heritage assets in order to improve their accessibility and visitation potential and ensure their sustainability. These characteristic landmarks and sites along these cultural tourism routes can be accompanied and interlinked with existing or new cultural and social events within the region, within the priorities and guidelines set by regional and local development plans. This will enhance the provided touristic product as well as improve social cohesion.

The proposal consists of six individual routes, across the rivers, the lakes, and the coastlines of Aitoloakarnania. The emphasis of the cultural routes on the dialogue between the region’s cultural heritage and its natural heritage is justified due to the strong environmental footprint (river, lakes, mountainous areas, seashore areas) of the region, and the impact of the environment on the historic and socioeconomic evolution of Aitoloakarnania throughout time. Therefore, the six cultural routes generally follow the main natural attractions of the region, i.e., its rivers and lakes, the coastline, and the mountainous areas. Integrated to these natural environment attractions are monuments of different historical periods, points of religious interest, or areas of important environmental value.

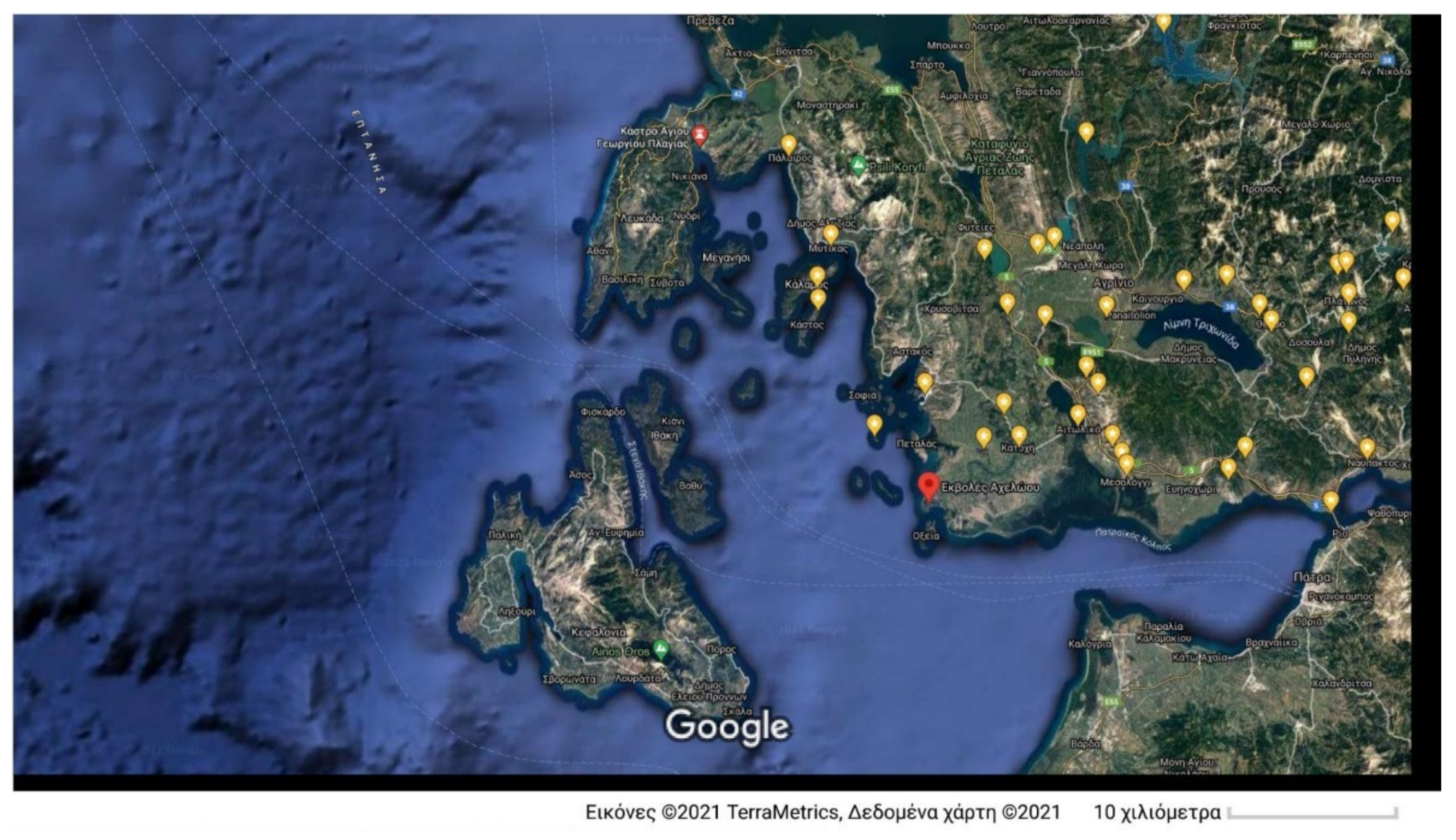

3.1. The Riverside Cultural Route of the Acheloos River

The first cultural route (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) is the riverside route of Acheloos, adjoining fifteen monuments, archeological sites, medieval fortifications, and churches as well as lakes and sites of natural beauty. The Acheloos River was a celebrated river in antiquity and formed the natural boundary of Aetolia and Acarnania. As such, a cultural route along the riverside of the Acheloos River serves to highlight the historic evolution of the region and its relation to its environment. Specifically, the cultural route connects: (1) The estuary of the Acheloos River (natural heritage); (2) The ancient Corinthian city of Iniades (archaeological site); (3) Katochi–Koulia of Kyra Vassiliki (Medieval castle with Byzantine remnants); (4) Monastery of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Lesini–Palaiokoutouna (Byzantine Monastery); (5) Ancient Sauria (Palaiomanina: Archaeological site, ancient city and fortifications, tombs); (6) Acarnanian Metropolis at Rigani (archaeological Cyclopean fortifications); (7) The Monastery of the Dormition of the Theotokos (Ligovitsi: meta-byzantine monastery complex); (8) Chrysovitsa (archaeological site of Koronta–tholos tombs); (9) Church of St. George and the Castle at Aggelokastro; (10) Church of the Holy Trinity of Mavrika (9th c. Byzantine church, 18th c. metabyzantine wall paintings); (11) Ochthia; (12) Stratos–Spolaita (remains of an ancient city, acropolis and settlement); (13) Lake Kastraki (Artificial lake–landmark); (14) Lake Kremasta (largest artificial lake in Greece–landmark); (15) Church of St. Andrew the Hermit (14th c. cave church new Chalkiopoulo village).

The selected points of interest regard a fusion of characteristic cultural heritage assets (archaeological sites, medieval castles, monasteries, churches) as well as landmarks of natural heritage (estuary of river, lakes). The compilation of these two groups of points of interest serves to highlight the interrelationship between the natural environment and the cultural heritage of the region. For example, even since antiquity, important settlements of the Acarnania (e.g., archaeological sites of Iniades, Sauria, Stratos) were built along the famous Acheloos River, and their evolution was closely interlinked with the natural environment. Due to their importance, thus, this cultural route has a strong archaeological character, at least compared to the other routes described below.

Accommodation facilities along this riverside route are rather limited. Accommodation is mainly served by the nearby city of Agrinio, which has various hotels and motels and is located approximately at the center of this route. In fact, the city of Agrinio can also provide accommodation to support the lakeside cultural route of Lake Trichonida (see below). Food services are provided throughout the various villages along the route, as well as at the city of Agrinio. The points of interest can be accessed either by car (preferable) or by bus services (KTEL network from Agrinio).

This riverside cultural route effectively trans-cuts the main national transportation route from Patras to Ioannina, in western Greece. Therefore, it can serve as a “cultural” or “scenic” bypass for travelers along this national road network, to offer them daily excursion or shortstop options. Similarly, for tourists and visitors residing in the greater Mesolonghi area, this riverside route can provide them with an accessible alternative to the coastline cultural route of Aitoloakarnania (see below), as well as with a representative experience of the wealth of cultural and natural assets of the interior of the region.

This riverside cultural route can address the interests of various visitors. It offers important archaeological sites (for visitors interested in the ancient history of the region), various monasteries and churches (for those interested in the Byzantine and medieval history of Aitoloakarnania), and sites of natural beauty (for visitors interested in the natural environment of the region). The combination of large-significant points of interest (e.g., archaeological site of Iniades) with small-sized architectural assets (e.g., church and castle ruins at Aggelokastro), as well as scenic routes (lakes and estuaries), provides visitors with the opportunity to go to multiple points of interest (in a mix-and-match approach) along the route in daily excursions. It is estimated that the whole riverside cultural route can be completed in a three- or four-day timeframe, depending on the interests of the visitors. The seasonality of the cultural route is rather spread on an annual basis since it does not contain any significant summer or winter resort or point of interest. However, in summer, the southern part of the cultural route is relevant to the tourism at the Messolonghi area, whereas the northern part of the cultural route is relevant to the tourism at the Preveza–Vonitsa greater area.

3.2. The Riverside Cultural Route of the Evinos River

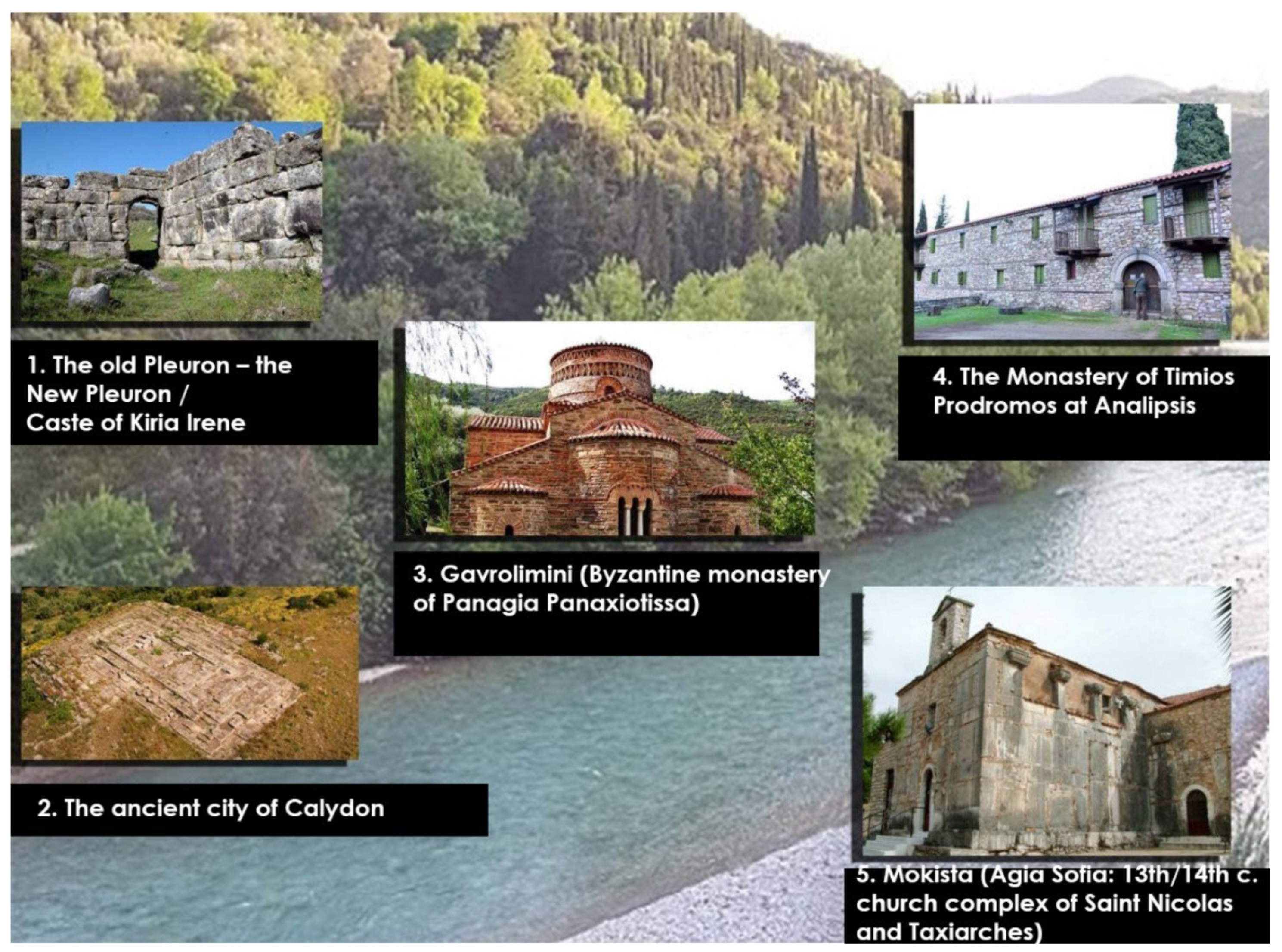

The second cultural route (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) is analogous to the riverside route of the Acheloos River, in the sense that it connects points of interest spanning many periods of history. Specifically, it follows the river Evinos, with five points of interest revealing the historical testimonies from prehistoric times to the Byzantium. It connects: (1) The old Pleuron–the New Pleuron/Caste of Kiria Irene (archaeological site and Cyclopean walls); (2) The ancient city of Calydon (archaeological site and acropolis); (3) Gavrolimini (Byzantine monastery of Panagia Panaxiotissa); (4) The Monastery of Timios Prodromos at Analipsis (Dervekista: 12th c. monastery); (5) Mokista (Agia Sofia: 13th/14th c. church complex of Saint Nicolas and Taxiarches) (

Figure 6).

The route is supported in terms of accommodation by the city of Messolonghi (which is close to its southern end) or alternatively by the city of Nafpaktos (closer to its northern end), whereas food services are available throughout its course. Its location, effectively, between the cities of Messolonghi and Nafpaktos enables the route to serve as an “inland” cultural route supplementing the tourist facilities of these two cities. Its vicinity to the Rio-Antirrio bridge allows additional visitors from the greater Achaia region to visit this cultural route. Its seasonality is similar to the riverside cultural route of Acheloos. This cultural riverside route does not contain any points of interest relevant to natural heritage, however, it is closely interlinked with the lakeside cultural routes described below. It is estimated that the whole riverside cultural route can be completed in a two-day timeframe. Similarly, this riverside cultural route is accessible by car (preferable) or bus.

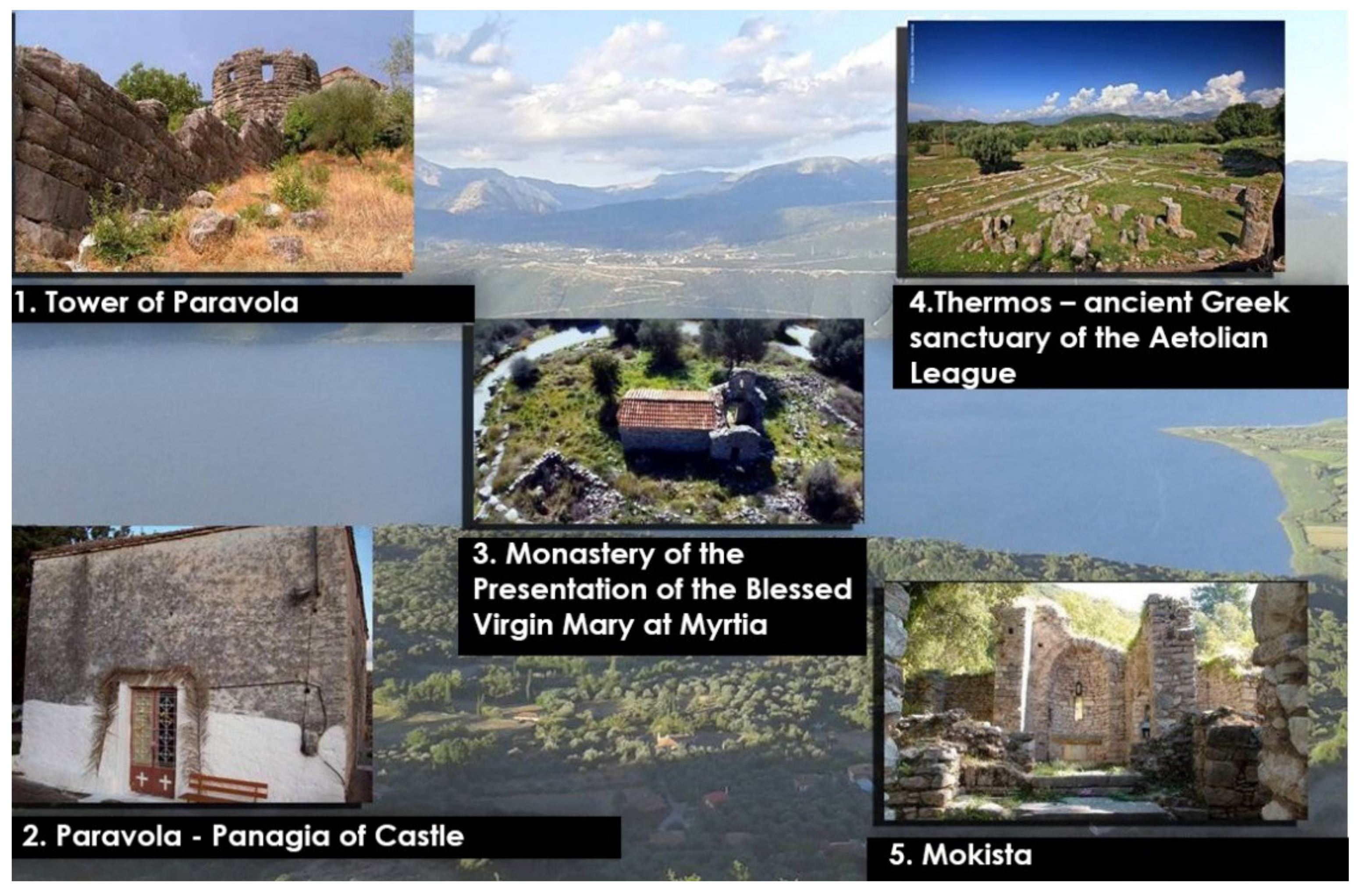

3.3. The Lakeside Cultural Route of Lake Trichonida

The third cultural route (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8) is connected to the riverside cultural route of the Evinos River and corresponds to the lakeside cultural route of Lake Trichonida. Initiating at the city of Agrinio, it connects: (1) Tower of Paravola (remnants of fortifications including ruins of the ancient city of Voukatio with additional byzantine towers); (2) Paravola-Panagia of Castle (Palaeochristian church); (3) Monastery of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Myrtia (11th -16th c. Byzantine church) and the ruins of Saint Apostles Monastery at Neromanna; (4) Thermos—ancient Greek sanctuary of the Aetolian League (archaeological site)—Temple of Apollo Thermios; (5) Mokista (Agia Sofia: 13th/14th c. church complex of Saint Nicolas and Taxiarches).

This cultural route offers a balanced range of sites relevant to the ancient and Byzantine history of Aitoloakarnania, with emphasis on the latter. The city of Agrinio offers the opportunity (in terms of accommodation) to combine this cultural route with the aforementioned riverside route of Acheloos, or alternatively to combine it with the riverside cultural route of Evinos, within a circular path (i.e., Agrinio, Trichonida Lake, Evinos River towards the south and back to Agrinio). As an option, especially during the summer season, this cultural route can serve as an alternative path from Nafpaktos to the northwest part of Aitoloakarnania and the Epirus regions, instead of the national network. Depending on the interests of the visitors, this cultural route can be completed within a two-day timeframe (being based in Agrinio or Nafpaktos), or certain sites within a daily excursion or by-pass along the Agrinio–Nafpaktos travel axis.

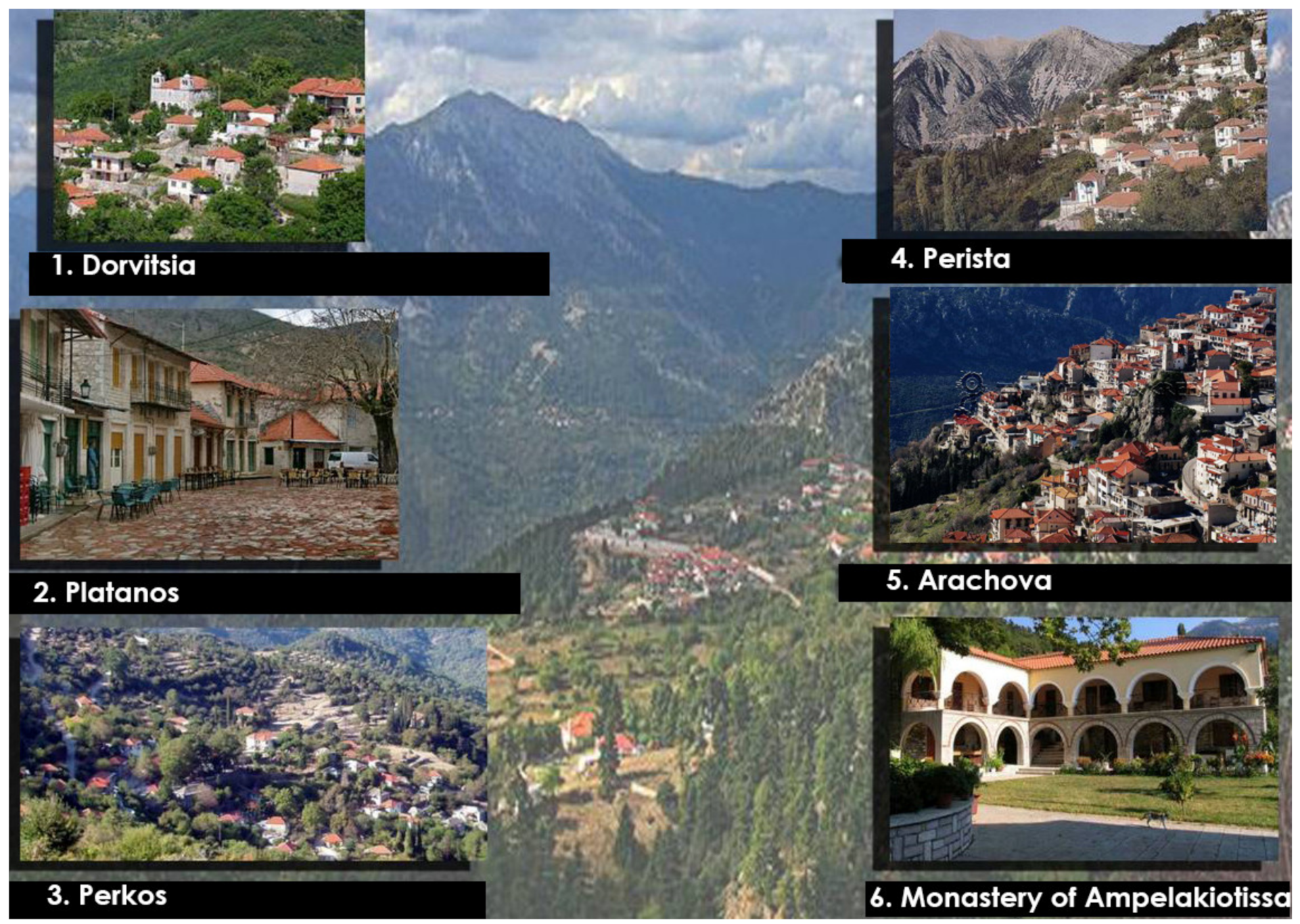

3.4. The Cultural Route Diversion to the Mountainous Nafpaktia

The fourth cultural route (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10) is also connected to the riverside cultural route of the Evinos River but diverts towards the mountainous Nafpaktia area. The route connects five traditional settlements: (1) Dorvitsia; (2) Platanos; (3) Perkos; (4) Perista; (5) Arachova (Arachova of Nafpaktia does not refer to the famous Arachova Mountain town at Viotia, a famous winter tourist destination close to the Parnassos ski resort); and (6) Monastery of Ampelakiotissa (15th c. Monastery).

This cultural route emphasizes the traditional settlements in the mountainous region. It is mainly addressed to winter tourism, especially to those tourists that prefer a less-busy traditional destination. Accommodation is rather limited, though, with very few small hotels. However, Airbnb is increasingly available in these traditional settlements, supporting the influx of visitors. Alternatively, these traditional settlements can be reached either from Agrinio or from Nafpaktos, both of which offer adequate accommodation facilities throughout the year.

3.5. The Coastline Cultural Route of Aitoloakarnania

The fifth cultural route (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12) regards the coastline of the prefecture of Aitoloakarnania, along the Gulf of Corinth and the Ionian Sea. Due to its historic significance and touristic infrastructure, this cultural route initiates at the city of Nafpaktos. Specifically, it connects: (1) Venetian Fortress of Napfaktos; (2) Castle of Antirrio; (3) Caves at Varasova mountain (Byzantine hermitages, 9th-18th c. cave monastery of Agios Nikolaos); (4) Sacred Town of Messolonghi (Fortifications, bastions, etc.); (5) Messolongi-Aitoliko lagoons complex (Natura 2000 habitat, natural heritage, bird watching); (6) Aetoliko (traditional settlement, natural heritage, fish huts, fishing); (7) Church of the Dormition of Theotokos at Aetoliko (metabyzantine church); (8) Agios Nikolaos Kremastos (Byzantine cave monastery of St. Nicolas-hermitage); (9) Agios Ilias of Aetoliko (tholos tombs); (10) Echinades islets (natural heritage); (11) Platigiali of Astakos (Gulf of Astakos, Kantilia-Valti wildlife habitat); (12) Remnants of Byzantine churches at Graves of Astakos; (13) Agia Eleousa at Mytikas (Byzantine monastery, hermitage); (14) Alyzia (Remnants of the harbour of the ancient Acarnanian city of Alyzia); (15) Island of Kalamos—Island of Kastos (the Homeric islands of Tafos and Karnos); (16) Paleros (ancient city of Paleros-Acropolis—Castle of Kechropoula); (17) Sollion (Ancient Corinthean city—the flee of Sellians); (18) Fortress of Plagia.

This cultural route is arguable a sizeable route with many points of interest. As in the case of the Acheloos riverside cultural route, the coastline route offers a balanced range of points of interest addressing interests related to antiquity, the Byzantine era, modern history as well as natural heritage. In effect, it serves as a timeline of Aitoloakarnania from antiquity to the Greek independence war, all intertwined with a unique ecosystem (lagoons, gulf, islets).

Due to the route being a coastline path, it is understandable that it is mainly addressed to summer tourism when the coastline cities and resorts are full of visitors. However, the inclusion of main historic cities like Nafpaktos and Messolonghi, which exhibit touristic activities throughout the year, ensures that these cities can serve as regional departure points to attend this cultural route in a modular manner, focusing on those points of interests closer to these cities.

The diversification of thematic interests that these sites along the route offer, enables the attraction of a wide range of visitors, from the typical summer resort tourist, to pilgrims, and to naturalists. The cultural route can function as a “scenic” or “cultural” alternative route from Peloponnese to the Epirus region, for those travelers that would like to avoid the rather uninspiring national road network in this region. In the summer, this cultural route can be promoted as a daily excursion route for tourists at the island of Lefkada since the latter comprises a well-established destination of international tourism.

3.6. The Southern Coastline Cultural Route of Amvrakikos Gulf

The final cultural route (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) regards the southern coastline of the Amvrakikos Gulf. It connects: (1) Fortress of Actium; (2) Ancient Anaktorion—Sanctuary of the Acarnanian League; (3) Fortress of Vonitsa; (4) Church of Panagia Alichniotissa (Byzantine church); (5) Monastiraki—Church of Pantocratoras (Byzantine church); (6) Romvos Monastery (Metabyzantine monastery complex); (7) Thyrreio (Ruins of the ancient city of Thyrreio, Fortifications, museum); (8) Ancient city of Heraclia (ruins); (9) Echinos (ancient port of Thyrreio); (10) Limnaia (Fortress of Amfilochia)—ruins of ancient city—Acropolis and walls towards the coast; (11) Church of Agios Stefanos at Rivio; (12) Archaeological site of the ancient city Amphilohicon Argos; (13) Bouka—Archaeological site of Olpes; (14) Monastery of Retha (metabyzantine monastery complex); (15) Menidi (coastal village, historic place of WWII).

This cultural route also offers various sites of archaeological or byzantine importance, to highlight the history of the area around the Amvrakikos Gulf. It is mainly addressed to visitors with relevant interests, rather than to resort-conscious tourists, despite the natural environment of the region (Amvrakikos Gulf). It is best accessible from the cities of Preveza, Aktio, and Vonitsa, or even Arta, which offer adequate accommodation facilities, or as in the case of the coastline route, as an alternative daily-excursion option for tourists from the island of Lefkada.

3.7. The “Dialogue” of the Cultural Routes with the Boundaries of the Aitoloakarnania Region

As is evident from the definition and design of the above cultural routes, they cover most of the region of Aitoloakarnania. However, the selection and design of these routes were not based solely on this criterion, i.e., to cover as much area as possible. Instead, these cultural routes aim to present to the visitors the “dialogue” between the cultural heritage assets, the environment of Aitoloakarnia as well as the boundary regions and paths of culture.

The scope of the riverside cultural route of the Acheloos River is to highlight the continuity of the region from antiquity to modern times, and how this continuity is affected, as well as “bounded” by the path of this emblematic river. In antiquity, the Acheloos River functioned as the physical boundary between Aetolia (east part of the region) and Acarnania (west part of the region), as well as the natural connecting path, to the north, with Epirus and Thessaly and the corresponding civilizations. Nowadays, the Acheloos River simply transects the main transportation path from continental Greece (Attica region) to the Balkans and Europe. The selected points of interest along this riverside path are simple “memories” of a bygone era.

The riverside cultural route of the Evinos River and the lakeside cultural route of Lake Trichonida, as well as the diversion to the mountainous areas, are all interlinked and represent the cultural diversity and natural beauty of the eastern part of the region. In antiquity, this general area separated Aetolia from Ozolian Locrians. Nowadays, the area that these cultural routes refer to is simply the interior eastern area of the prefecture of Aitoloakarnania, most of the socioeconomic activities focusing outside its boundaries (e.g., cities of Agrinio, Messolonghi, Nafpaktos). Thus, these routes aim to reinstate the importance of this area to the interior development of the prefecture.

The coastline route of Aitoloakarnania aims to highlight the dialogue between the region and its surrounding Ionian Sea and Corinthian Gulf. This coastline has for centuries acted as the natural boundary for societal interactions between Peloponnese and Aitoloakarnania and between Ionian islands (and corresponding western European influence) and Aitoloakarnania. The strategic position of the coastline of Aitoloakarnania, effectively “guarding” the entrance to the Corinthian Gulf, and in particular, the historic city of Messolonghi and the lagoon functioned as a vital bastion to the Greeks in the War of Independence. The dramatic “Exodus of Messolonghi” was instrumental in promoting the ideas of the Greek independence war throughout Europe.

The lakeside cultural route of the Amvrakikos Gulf, within its southern side, aims to identify and highlight the cultural differences as well as the cultural interactions (especially during the Byzantine period) between the regions of Epirus and Aitoloakarnania.

4. “Smart” Approaches to Promote the Cultural Routes of Aitoloakarnania

The above-described cultural routes, part of the wide-ranging cultural and environmental reserve of Aitoloakarnania, serve to promote the cultural heritage of the region and aid in its development. However, in order to achieve this, three main issues should be addressed: Information, accessibility, Tourism infrastructure. In fact, it is crucial for regional and local stakeholders to find “smart” ways to address these long-standing deficiencies.

Knowledge of the wealth of cultural heritage of the region is crucial not only to visitors but also to the locals. Education can promote a sense of proudness in the local communities and inhabitants. The information power of social media should be fully exploited, whereas relevant information websites that promote relevant local events (traditional fairs, religious events, musical shows, etc.) should be encouraged and supported (e.g., funded through advertisements). The quality and content of the official websites of all regional and local authorities should be improved and interlinked with the local radio and TV channels, promoting events of the region with emphasis along the aforementioned cultural routes. Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) can also play an important role, through the utilization of mobile telephony applications that enhance the dissemination of information relevant to the region. The authorities should improve their efforts in supporting mobile telephone ICT applications and install and support a region-wide Wi-Fi network, at least at public spaces and the aforementioned cultural sites. “Smart” electronic advertisements along the main transportation network (e.g., electronic signs) can highlight the virtues of “scenic routes” within the region and inform visitors of the cultural and natural heritage of Aitoloakarnania.

The issue of accessibility [

35] is very important for Aitoloakarnania. Due to the limited transport infrastructure of the region (especially rural roads), access to many of these heritage assets is hindered. Accessibility should not be approached only through the improvement of road infrastructure. In fact, due to the current economic situation in Greece, it is highly improbable that the road network relevant to the aforementioned cultural routes can be properly maintained or even be improved. Instead, Aitoloakarnania should focus on “smart accessibility”, by exploiting ICTs and the latest digital technological advancements. “Virtual tours” within the aforementioned cultural assets can be developed, accessible through central information kiosks within the region. For example, although it would be difficult to climb a mountain to access a cave monastery, a central information kiosk in the nearby village can alternatively provide a virtual tour of the site at the comfort of the local café or plaza. This would have the added advantage of consolidating commerce activities in selected locations improving the motivation for relevant investments. Other alternative smart approaches could include drone “aerial virtual tours” (e.g., around Fortresses). However, a balance should be drawn between virtual tours and in-situ accessibility, since “hands-on” experience is indispensable in appreciating the cultural heritage of the region. Moreover, the in-situ visits are obviously more desirable from the development point of view as the tourist influx provides wide-ranging advantages to the region. However, in cases where accessibility is limited, IT can offer beneficial solutions.

Tourism infrastructure is an issue that must be carefully addressed. Cultural Tourism needs to be gradually and sustainably developed, in order to avoid excessive investments without the desired socio-economic impact. Authorities and stakeholders in Aitoloakarnania should coordinate their strategic planning and efforts by providing an initial “nucleus” of touristic infrastructure along the aforementioned cultural routes. Nafpaktos, Mesollonghi, and Vonitsa are among the few traditional cities in the region that have already developed significant touristic infrastructures, such as hotels, houses for rent, restaurants, museums, craft shops, etc. Similar facilities in other cities and villages should be enhanced. The airport at Aktio should be better exploited to play a vital role for touristic development, acting as the direct gateway of Aitoloakarnania from Europe and abroad. Additionally, PPPs should encourage the adaptive reuse of traditional buildings for touristic utilization, while ensuring their compatible and sustainable preservation. This has the additional “collateral” advantage of sustaining local construction companies and supporting a workforce of specialized builders and experts. Most importantly, the adaptive reuse of the regional cultural heritage assets will ensure that the architectural heritage of Aitoloakarnania will be preserved and promoted.

5. The Role of the Cultural and Environmental Reserve

The cultural and environmental reserve includes the entire cultural reserve, (monuments, ensembles, historic buildings and sites, archaeological sites, traditional settlements, architectural heritage, and others), the intangible heritage, the environmental assets (landscapes, seascapes, and areas of natural beauty) as well as authentic products of local production and fisheries. The effective management of collaborations at all levels and especially the elaboration, through dialogue with the local communities, of flexible educational programs for adaptation to the new development actions, results in the local society receiving the maximum added value. This mechanism attracts external economies and invests in endogenous development, strengthening social cohesion and improving the quality of life of local populations. The added value does not only concern the local and social development, as mentioned above, but also creates a national advantage in the whole region of Aitoloakarnania by highlighting and strengthening its cultural and environmental identity (National Brand Name). The emergence of a distinct brand identity [

36], is crucial for tourism (and its associated impact on regional development, and a process in which the prefecture of Aitoloakarnania needs to pay attention in order to assist their efforts in diversifying themselves from established tourist destinations and tourist products. The collection and correlation of analysis/documentation/management data of the cultural and environmental reserve (CER), with its integration into the local economy, will be a valuable tool for its promotion and utilization with added value in the local economy and will contribute to the creation of innovative methodologies for sustainable development.

At present, the architectural heritage and cultural assets are at risk, the assimilation capacity of the natural environment is violated, whereas the natural and built environment is altered with arbitrary non-planned interventions and overexploitation. Nevertheless, the innovative know-how of conservation and protection of the CER by strengthening its resilience can allow the development of the necessary strategies, measures, and politics for its sustainability. Innovative ICT applications will allow the reveal and promotion of the special characteristics of the CER of Aitoloakarnania, with end-users the stakeholders, the touristic operators, the local financial players, the citizens, and the visitors.

The design of a Circular Economy model that utilized the region’s CER, within the fundamental prerequisites of social cohesion and sustainability, can be achieved with PPPs for the promotion and utilization of the CER as investments in the local economy and in Tourism for the creation of new resources, products, and infrastructures that infer an added value to the local economy and impart multiplying effects on jobs and on social cohesion. The circular economy model is achieved since investments in the utilization of the region’s CER generate revenue that allows the maintenance, preservation, and protection of the CER itself. The design, planning, and implementation of local development are carried out as a function of the central regional strategies and in the framework and within the limitations of the financial support for the Region of Aitoloakarnania [

25].