The Medieval Town of Óbidos (Portugal): Restoration, Reutilisation and Tourism Challenges from 1934 to the Present Day

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Critical reading of the available studies, on Óbidos, namely those based on interviews and surveys conducted by other authors.

- -

- Research of historical archives, mainly unpublished documents.

- -

- Analysis of the minutes of meetings, reports and other publications of the municipality, as well as published interviews with mayors.

- -

- In situ observation of the town heritage (both from the point of view of its conservation and its tourist enjoyment).

- -

- Attendance of festivals and events promoted throughout the year by the town council, in order to formulate our own opinion based on experience).

- -

- Informal contact with some residents and merchants of Óbidos.

- -

- Establishment of a theoretical framework of the various issues.

- -

- A critical analysis of the results of this research.

- -

- What were the prevailing criteria in the conservation and restoration of the town of Óbidos from the 1930s to the 1950s?

- -

- How did those interventions impact tourism during the Estado Novo?

- -

- Does tourism currently play an active role in the preservation and conservation of the historic buildings and monuments of the town?

- -

- Do the tours to the town and the attendance of the events currently included in the cultural and tourism programme facilitate a deeper knowledge of the town, its history and its monuments?

- -

- Can we speak of authenticity in Óbidos, both in the restoration works it has undergone and in its tourist management strategies?

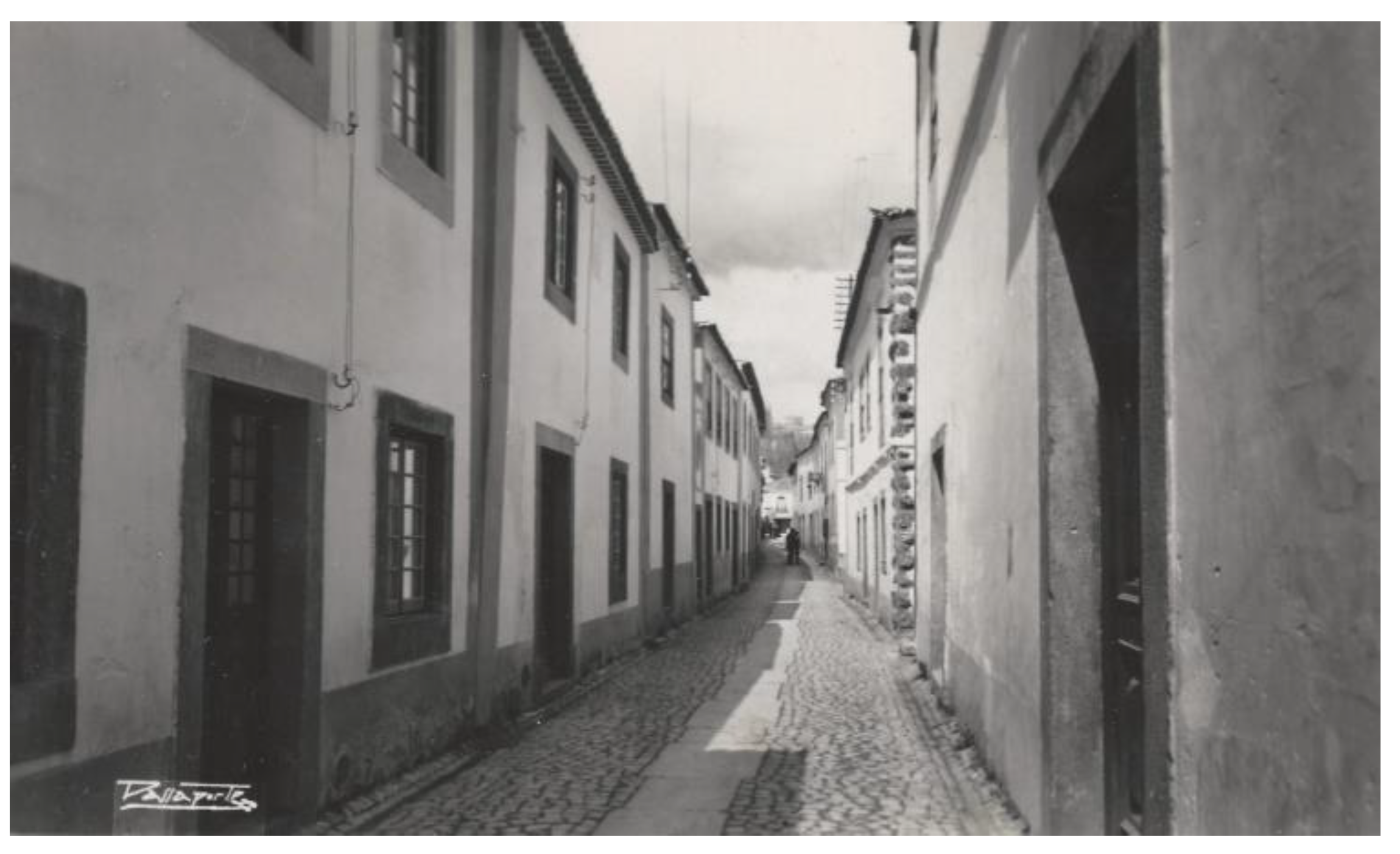

2. Case Study and Contextualisation

3. Research Results

3.1. A Restoration Programme for Medieval Óbidos (1934–1949)

3.1.1. ‘Reintegration’ Criteria

3.1.2. International Recognition. Baron Henck van Tuyll Serooskerken’s and Cesare Brandi’s Accounts

That visit was not only a success, but also a great accomplishment on every level. We could learn about major moments of your national history in the realm of both archaeology and history…I can…recognise the care and work that the Portuguese State has devoted to its cultural heritage.[34]

Now one could argue: is it really necessary to travel to Portugal for such an inexpensive immersion in the past? Perhaps there is no such thing in Italy…and how do I yearn for it. Because in Italy there is no place as well preserved as Óbidos, as is the norm in Portugal, regardless of Óbidos’ unique and modest features. In Italy, any small town like Óbidos (if there is one) suddenly has a ridiculous quasi-skyscraper, the presumptuous little houses that had to be built near the fortress wall, graceless, disrespectful, lacking concern for both people and things.[35]

3.2. Óbidos in the Context of the Tourism Policies of the Estado Novo

3.3. Current Challenges Posed in the Management of Óbidos Heritage

3.3.1. Growth of Cultural Tourism: Development, Innovation, Creativity and (Un)sustainability

3.3.2. Conservation, Restoration and Promotion of Cultural Heritage Concerns

Conservation and Rehabilitation of the Castle Wall

Repurposing of Ruined Buildings into Creative Hubs

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neto, M.J. Memória, Propaganda e Poder: O Restauro dos Monumentos Nacionais (1929–1960), 1st ed.; FAUP: Porto, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P.A. Castelo de Óbidos e todo o Conjunto Urbano da vila. Nota Histórico-Artística. Available online: http://www.patrimoniocultural.gov.pt/pt/patrimonio/patrimonio-imovel/pesquisa-do-patrimonio/classificado-ou-em-vias-de-classificacao/geral/view/70427 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Fidalgo, S.; Fernandes, J.L. Marketing territorial, inovação, paisagem e património: O estudo de caso de Óbidos. In Atas do XII Colóquio Ibérico de Geografia; Faculdade de Letras (Universidade do Porto): Porto, Portugal, 2010; pp. 1–18. Available online: http://web.letras.up.pt/xiicig/comunicacoes/158.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Selada, C.; Cunha, I.V.; Tomaz, E. Creative-based strategies in small cities: A case-study approach. REDIGE 2011, 2, 79–111. Available online: https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/14268/1/Creative-based%20strategies%20in%20small%20cities.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Santos, J. As Cidades Criativas Como Modelo Dinamizador do Destino Turístico. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Tomar-Escola Superior de Gestão, Tomar, Portugal, 2012. Available online: https://comum.rcaap.pt/bitstream/10400.26/5733/1/As%20Cidades%20Criativas%20como%20modelo%20dinamizador%20do%20destino%20tur%C3%ADstico.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Centeno, M.J. Óbidos, Literary Village: Innovation in the creative industries? In Proceedings of the 7th Annual Research Session ENCATC-Cultural Management Education in Risk Societies—Towards a Paradigm and a Policy Shift; Imperiale, F., Vecco, M., Eds.; ENCATC: Valencia, Spain, 2016; pp. 41–51. Available online: https://repositorio.ipl.pt/handle/10400.21/6487 (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Musikyan, S. The Influence of Creative Tourism on Sustainable Development of Tourism and Reduction of Seasonality—Case Study of Óbidos. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, ESTM-Escola Superior de Turismo e Tecnologias do Mar, Peniche, Protugal, 2016. Available online: https://iconline.ipleiria.pt/handle/10400.8/2147?locale=en (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Miguéis, I.G.; Fernandes, F.; Ribeiro, R.B. Place Branding—Óbidos e os eventos culturais: Estudo de caso sobre Óbidos Vila Natal e Festival do Chocolate. RTD 2017, 1, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reino, V. A Imagem do Destino Turístico de Óbidos do Ponto de Vista do Visitante de Eventos. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico de Leiria, ESTM-Escola Superior de Turismo e Tecnologia do Mar, Peniche, Portugal, 2013. Available online: https://iconline.ipleiria.pt/bitstream/10400.8/1090/1/Disserta%C3%A7%C3%A3o%20Vera%20Reino.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Santos, P. O Turismo em Óbidos: Dos anos 70 ao Presente. Master’s Thesis, ISCTE/Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2011. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10071/4207 (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Prista, M.L. Turismo e sentido de lugar em Óbidos: Uma pousada como metáfora. Etnográfica 2013, 17, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silveira, L.; Tretin, F.; Ferreira, V. Tourim development in small destinations through creativity and innovation in events—The cases of Óbidos (Portugal) and Paraty (Brazil). In Local Identity and Tourism Management on World Heritage Sites—5th UNESCO UNITWIN Conference; Cravidão, F., Santos, N., Moreira, C.O., Ferreira, R., Nossa, P., Silveira, L., Eds.; CEGOT—Centro de Estudos de Geografia e Ordenamento do Território: Coimbra, Portugal, 2017; Volume I, pp. 493–514. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10316/43476 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Ribeiro, R.; Dias, F.; Almeida, A. Fatores Intensificadores da Experiência Turística: O Caso do Mercado Medieval de Óbidos, Portugal. Rev. Port. Estud. Reg. 2020, 53, 35–54. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7220882 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Flor, P. O Túmulo de D. João de Noronha e de Isabel de Sousa na Igreja de Santa Maria de Óbidos, 1st ed.; Edições Colibri: Lisbon, Portugal, 2002; ISBN 9789727723010. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.R. Anamnesis del Castillo como Bien Patrimonial. Construcción de la Imagen, Forma y (Re)Funcionalización en la Rehabilitación de Fortificaciones Medievales en Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alcalá, Departamento de Arquitectura, Alcalá, Spain, 2012. Available online: https://ebuah.uah.es/dspace/handle/10017/14021 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Soares, C.M.; Neto, M.J. Óbidos. De «Vila Museu» a «Vila Cultural», 1st ed.; Caleidoscópio: Casal de Cambra, Portugal, 2013; ISBN 9789896582241. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Beyond Authenticity and Commodification. Ann. Tour. Res. 2007, 34, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, A. The Authenticity Hoax: How We Get Lost Finding Ourselves; Scribe: Carlton North, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, H. Heritage and Authenticity. In The Palgrave Handbook of Contemporary Heritage Research; Waterton, E., Watson, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2015; pp. 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletim da Direção Geral dos Edifícios e Monumentos Nacionais. Castelo de Óbidos; Ministério das Obras Públicas e Comunicações: Lisboa, Portugal, 1952; pp. 68–69.

- Fernandes, J.M. Pousadas de Portugal. Obras de raiz e em Monumentos. In Caminhos do Património (1929–1999), 1st ed.; Vieira, J., Alçada, M., Grilo, M.T., Eds.; DGEMN: Lisbon, Portugal, 1999; pp. 159–177. ISBN 9729763828. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, S. Pousadas de Portugal. Reflexos da Arquitectura Portuguesa do Século XX, 1st ed.; Imprensa da Universidade: Coimbra, Portugal, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Athens Charter for the Restoration of Historic Monuments. 1931. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/167-the-athens-charter-for-the-restoration-of-historic-monuments (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Direção-Geral dos Edifícios e Monumentos Nacionais/Direção Geral do Património (DGEMN/DGPC) Archive, Castelo de Óbidos, DSID 001/010-1136, p. 373, Record Dated 09-06-1962. Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPAArchives.aspx?id=092910cf-8eaa-4aa2-96d9-994cc361eaf1 (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- DGEMN/DGPC Archive, Castelo de Óbidos, DSID 001/010-1137, p. 298, Technical Description Dated 10-03-1972. Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPAArchives.aspx?id=092910cf-8eaa-4aa2-96d9-994cc361eaf1 (accessed on 5 June 2021).

- Tomé, M. Património e Restauro em Portugal (1920–1995), 1st ed.; FAUP: Porto, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, L. Restauro versus conservação: Castelos em Portugal no Estado Novo: Breve nota sobre o papel da DGEMN. Estud. Século XX 2009, 9, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission—Restoration to put Karytaina Castle on the tourist map, European Regional Development Fund (2007–2013). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/projects/greece/restoration-to-put-karytaina-castle-on-the-tourist-map (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter 1964). Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Neto, M.J. A propósito da Carta de Veneza (1964–2004). Um olhar sobre o património arquitectónico nos últimos cinquenta anos. Rev. Património. Estud. 2006, 9, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- DGEMN/DGPC Archive (Forte de Sacavém); DSARH–010/000-0183, letter dated 17-08-1964; International Burgen Institute (IBI): Houston, TX, USA, 1964; p. 163.

- DGEMN/DGPC Archive (Forte de Sacavém); DSARH–010/000-0183, letter dated 25-06-1965; International Burgen Institute (IBI): Houston, TX, USA, 1965; pp. 355–356.

- Brandi, C. Portogallo. In A passo d’uomo; Col. Bompani: Milan, Italy, 1970; pp. 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ferro, A. Turismo, Fonte de Riqueza e Poesia; Secretariado Nacional de Informação: Lisbon, Portugal, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Mariz, V. O desenvolvimento do Turismo em Portugal pela “política do espírito” de António Ferro (1932–1949). RTD 2011, 16, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadavez, M.C. A Bem da Nação. As Representações Turísticas no Estado Novo entre 1933 e 1940. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8401 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Cipriano, C.; Ferreira, F. Óbidos deverá ser repovoada ter vida própria ou está bem assim. Gazeta das Caldas, 9 February 2013. Available online: https://gazetadascaldas.pt/sociedade/obidos-repovoada-vida-propria-cenario-eventos/ (accessed on 12 September 2021).

- DGEMN/DGPC Archive, DSARH-010/173-0073—Vila de Óbidos, Sale of Properties in Óbidos. Available online: http://www.monumentos.gov.pt/Site/APP_PagesUser/SIPAArchives.aspx?id=092910cf-8eaa-4aa2-96d9-994cc361eaf1 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Garcia, L.M. Óbidos: 20 anos de Intervenção Autárquica 1980–2000; Câmara Municipal de Óbidos: Óbidos, Portugal, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McKercher, B.; Cross, H. Cultural Tourism. The Partnership between Tourism and Cultural Heritage Management, 1st ed.; The Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780789011060. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Ruiz, M. Trivialidad y trascendencia. Usos sociales y políticos del turismo cultural. In Turismo Cultural: El Patrimonio Histórico como Fuente de Riqueza; Herrero Prieto, L., Ed.; Fundación del Patrimonio Histórico de Castilla y Léon: Valladolid, Spain, 2000; pp. 31–52. ISBN 8493116319. [Google Scholar]

- Choay, F. A Alegoria do Património, 13th ed.; Edições 70: Lisboa, Portugal, 2006; ISBN 9789724412054. [Google Scholar]

- Balibrea, M.P. Memória e espaço público na Barcelona pós-industrial. Rev. Crítica Ciências Sociais 2003, 67, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AlSayyad, N. Editor’s Note. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2006, 18, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero Carot, F.; Zamora Baños, F.; Mesa Ruiz, J.I. La Dinamización del Patrimonio Cultural. In La Gestión del Patrimonio Cultural: La Transmisión de un Legado; Arias Martínez, M., Ed.; Fundación del Patrimonio Histórico de Castilla y Léon: Valladolid, Spain, 2002; pp. 255–280. ISBN 8493116394. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Kong, J. (Eds.) Creative Economies, Creative Cities; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 978-90-481-8226-8. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Creativity and tourism—The state of the art. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1225–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta del Turismo Sostenible. Conferencia Mundial de Turismo Sostenible, Lanzarote, Islas Canarias, España. 1995. Available online: https://www.biospheretourism.com/assets/arxius/cc909a3b8279ee1838274c43114f54a2.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Bruner, E.M. Tourism, Creativity and Authenticity. Stud. Symb. Interact. 1989, 10, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. The Ethics of Sightseeing, 1st ed.; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter. Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance. 1999. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/tourism_e.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Santos, J.R. Pleito Contra um Turismo (Tendencialmente) Insustentável: A Disneyficação de Óbidos. Lisboa: GECoRPA | Grémio do Património—Canto Redondo. Anuário Património 2018, 3, 276–281. Available online: https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/38107/1/Pleito_Contra_um_Turismo_Insustentavel.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- ICOMOS. The Declaration of San Antonio, Texas. 1996. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/188-the-declaration-of-san-antonio (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- ICCROM. Riga Charter on Authenticity and Historical Reconstruction in Relationship to Cultural Heritage. 2000. Available online: https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020-05/convern8_07_rigacharter_ing.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Picard, D.D.; Robinson, P.M. Emotion in Motion: Tourism, Affect and Transformation; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- García, M. Ávila: Planificación gestión turística local en una ciudad património de la humanidad. In Casos de Turismo Cultural: De la Planificación Estratégica a la Gestión del Producto, 2nd ed.; Font Sentías, J., Ed.; Editorial Ariel: Barcelona, Spain, 2004; pp. 413–441. ISBN 8434452022. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Interpretation and Presentation of Cultural Heritage Sites, Québec. 2008. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/interpretation_e.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Creative Footprint: The Next Big Step Will be a Lot of Small Steps. Óbidos. Local Action Plan; Creative Clusters in Low Density Urban Areas—URBACT Programme; Câmara Municipal de Óbidos, 2011; Available online: https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/lap_final_obidos_01.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Orbasli, A. Tourists in Historic Towns: Urban Conservation and Heritage Management, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RIO: Revista Informativa de Óbidos; Câmara Municipal de Óbidos. 2002; Volume 2. Available online: www.cm-obidos.pt/rio-02 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- RIO: Revista Informativa de Óbidos; Câmara Municipal de Óbidos. 2018; Volume 48. Available online: https://www.cm-obidos.pt/rio-48 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- RIO: Revista Informativa de Óbidos; Câmara Municipal de Óbidos. 2019; Volume 49. Available online: https://www.cm-obidos.pt/rio-49 (accessed on 2 July 2021).

- Começaram as Obras que vão Permitir dar uma Nova Centralidade a Óbidos. Óbidos Diário, 4 October 2011. Available online: https://obidosdiario.com/2011/10/24/comecaram-as-obras-que-vao-permitir-dar-uma-nova-centralidade-a-obidos/(accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Leiria, M. Óbidos Investe Para Converter Edifícios Degradados em Espaços Criativos. J. Região Leir. 2011. Available online: https://www.regiaodeleiria.pt/2011/10/obidos-investe-14-milhoes-na-transformacao-de-edificios-degradados-em-espacos-criativos/ (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Almeida, B. As Cidades Criativas e a sua Importância no Desenvolvimento Local: Óbidos, Uma Estratégia de Desenvolvimento Criativo. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10362/64810 (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist. A New Theory of the Leisure Class; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Beban, A.; Ok, H. Contribution of Tourism to the Sustainable Development of the Local Community: Case studies of Alanya and Dubrovnik; Master’s Programme in European Spatial Planning; Bleking Institute of Technology: Karlskrona, Sweden, 2006; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Contribution-of-Tourism-to-the-Sustainable-of-the-%3A-Beban-Ok/bf174560865d997e1c507674af299fc40d209ee1 (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Soldano, S.; Borlizzi, P.; Valle, M. Project RUINS CE902: Sustainable Re-Use, Preservation and Modern Management of Historical Ruins in Central Europe—Elaboration of Integrated Model and Guidelines Based on the Synthesis of the Best European Experiences; Report on Current State-of-Art of Use and Re-Use of Medieval Ruins, Interreg Central Europe Ruins; European Union, 2017. Available online: https://www.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/RUINS/D.T2.1.1---Report-on-the-current-state-of-art-on-contempo-1-.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Tavares, E.; Cardoso, M. A Receita de Óbidos. Exame. 2017. Available online: https://visao.sapo.pt/exame/2017-03-06-negocios-de-chocolate/ (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Bowdin, G.; Allen, J.; O’Toole, W.; Harris, R.; McDonnell, I. Events Management, 3rd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pes Seguer, M.C. Albarracín: Un Caso Único de Éxito Turístico. Grade in Marketing and Market Research, Universidad Zaragoza, Faculdad de Economía y Empresa, España. 2018. Available online: https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/77946 (accessed on 7 July 2021).

- Doroz-Turek, M. Revitalization of Small Towns and the Adaptive Reuse of Its Cultural Heritage. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 052006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroczynska, J. Enhancing the Attractiveness of Architectural Monuments as Tourist Attractions: Medieval Castle Ruins in the Area of Jura Krakowsko-Czestochowska in Poland as a Case Study. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 082062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, M.J. Óbidos, Vila Literária: Inovação nas Indústrias Criativas? In Actas ICONO14—V Congresso Internacional Cidades Criativas, 1st ed.; Alves, L.M., Alves, P., García García, F., Eds.; CITCEM: Porto, Portugal, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 1109–1123. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.21/7573 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Creaco, S.; Querini, J. The role of tourism in sustainable economic development. In 43rd Congress of the European Regional Science Association: Peripheries, Centres, and Spatial Development in the New Europe; European Regional Science Association (ERSA): Jyväskylä, Finland, 2003; pp. 1–17. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/115956 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Amin, A.; Roberts, J. (Eds.) Community, Economic Creativity, and Organization, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soares, C.M.; Neto, M.J. The Medieval Town of Óbidos (Portugal): Restoration, Reutilisation and Tourism Challenges from 1934 to the Present Day. Heritage 2021, 4, 2876-2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040161

Soares CM, Neto MJ. The Medieval Town of Óbidos (Portugal): Restoration, Reutilisation and Tourism Challenges from 1934 to the Present Day. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):2876-2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoares, Clara Moura, and Maria João Neto. 2021. "The Medieval Town of Óbidos (Portugal): Restoration, Reutilisation and Tourism Challenges from 1934 to the Present Day" Heritage 4, no. 4: 2876-2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040161

APA StyleSoares, C. M., & Neto, M. J. (2021). The Medieval Town of Óbidos (Portugal): Restoration, Reutilisation and Tourism Challenges from 1934 to the Present Day. Heritage, 4(4), 2876-2902. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040161