Abstract

This paper describes the public archaeology approach and placemaking experiment at the Etruscan and Roman site of Podere Cannicci in Tuscany (Italy), drawing from the previous experience at three other archaeological sites along the Tyrrhenian coast. After three years of excavations at the IMPERO Project (Interconnected Mobility of People and Economy along the River Ombrone), the team has begun a side project to develop new strategies for communicating the results of the research. These include, but are not limited to, an app which displays augmented reality and 3D reconstructions of both the site and the material culture. The project uses digital narratives to engage local communities and scholars in the interpretation and reconstruction of ancient landscapes along with the middle valley of the Ombrone river. This approach also has the potential to support and sustain local tourism, providing an original experience for visitors. Moreover, the solution allows people from all over the world to be connected with the ongoing research and its results, as everything will be published on a dedicated website.

1. Introduction

The world of cultural heritage is changing rapidly, and new approaches for its sustainability are needed to face the challenges that the 21st century is presenting to our communities nowadays. Unfortunately, we are responsible for having created a gap between academia and public communities, and for some decades we failed altogether to transmit our knowledge of the past to vast audiences. New challenges are arising in our discipline, much more related to how to preserve and make our monuments accessible, rather than producing more datasets from newly open excavations. It is time to put a damper on investigating and digging up more sites of excavation and to instead concentrate on what had already been uncovered. As Richard Hodges writes, “…will there be the means to challenge great questions about the past or will archaeologists increasingly concentrate upon making sense of and re-assessing discoveries made by our baby-boomer generation? A major aspect of the future of studying the past is to make it accessible to our communities [] we cannot afford any longer the inevitable. Public interest is becoming insatiable as global tourism and a global hunger for history reduces the import of mere reporting of digs” [].

Obviously, archaeological excavations continue and new sites are brought to light daily. However, approaches for relating to cultural heritage have changed. With the beginning of a new research expedition, the scholar’s eye is aimed almost immediately at the enhancement of a site and the construction of narratives around which to base tourist experiences as well as the involvement of local communities. Archaeologists are becoming placemakers [], providing historical identities to critical waypoints of the past (whether these are major or “minor” archaeological sites) and [] transmitting these identities through a number of different strategies and narratives to wider audiences.

Digital archaeology represents one of the many approaches to engage with wider audiences and to make our narratives be accessible to the most. 3D models and reconstructions, as well as the extensive use of virtual and augmented reality play a crucial role in our 21st century approach to monuments, archaeological sites and research and global tourism [,,,].

It is under this lens that our IMPERO project (Interconnected Mobility of People and Economy along the River Ombrone) in south Tuscany, Italy has begun to employ a strategy of placemaking, as we shall see in the next paragraphs. It is a journey that began in 2009, and like all challenges, it has seen moments of success alternating with some sudden setbacks. Each autumn, however, has allowed the development of new and unexpected directions in an attempt to achieve the development of innovative approaches in the management and transmission of cultural heritage.

2. The Impero Project

In 2016, a new archaeological project started at the University of Sheffield and continued under the Department of Classics at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) [,].

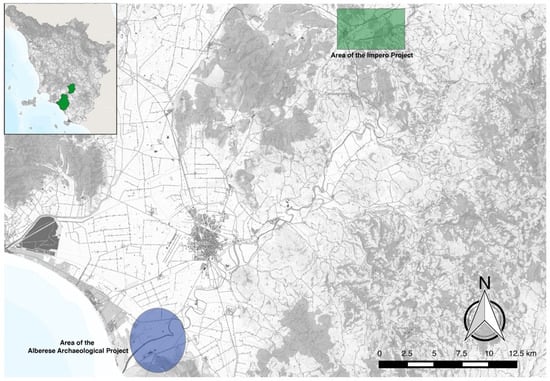

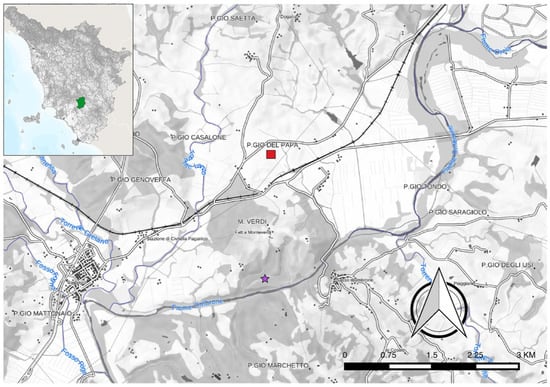

The IMPERO Project aims at reconstructing the historical landscape of the middle valley of the Ombrone river in south Tuscany from the Etruscan period until the end of the Middle Ages. Since last year, it has also included the data available from the Alberese Archaeological Project that was carried out between 2009 and 2016 on the coastal area of the ancient territory of the Etruscan-Roman city of Rusellae []. In this way, the research intends to fully document the intermittent changes that came into being in an under-investigated riverine landscape and to promote the discovery of ancient historical sites to local communities and global tourism (Figure 1). It is a path, as mentioned, which began in 2009 within the Maremma Regional Park, where the enhancement of historical and artistic attractions is accompanied by the preservation and protection of the natural environment. As we will see in the next paragraph, several strategies developed in the context of the Maremma Regional Park were put in place at Alberese and served as the starting point for a much more elaborated placemaking project for the inland area. Stemming from this effort, the IMPERO Project began with investigations into two archaeological sites located along the middle stretch of the Ombrone river, belonging to two different historical phases: on the one hand, the late Etruscan sanctuary and Roman Republican village of Podere Cannicci, and on the other, the ruins of the medieval fortified settlement of Castellaraccio di Monteverdi [], both within the modern Municipality of Civitella Paganico (Grosseto) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Map showing the geographical areas of research discussed in the paper.

Figure 2.

Map showing the area of the IMPERO Project. The red square indicates the location of Podere Cannicci, the late Etruscan and Republican sanctuary and vicus; the purple star indicates the location of the deserted medieval village of Castellaraccio di Monteverdi.

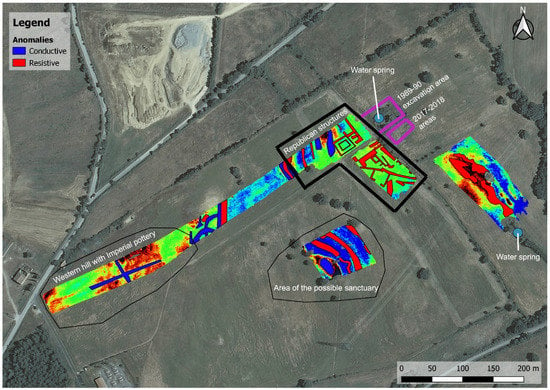

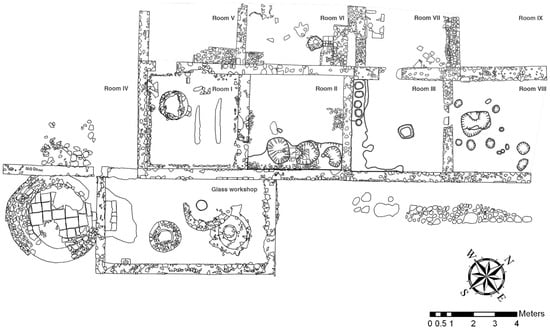

Located at the feet of gentle slopes of a Tuscan hill, Podere Cannicci represents quite an intriguing Etruscan to late Republican site (5th century BCE—early 1st century BCE) (Figure 3). Its story begins with a natural sacred place, attested by the abundance of votive offerings recovered in the 1980s during some rescue excavations carried out by the Soprintendenza Archeologica della Toscana [,], and continues with the construction of a possible vicus, the economic strategy of which relied heavily on its strategic location along riverine and terrestrial trade routes [,]. The village grew economically and, most likely, socially to the point of becoming a reference point within the surrounding territory. The excavations and geophysical surveys have clearly shown that the settlement extended on a wide area of at least 4 ha, with a number of different complexes (Figure 4), including dwellings for the villagers, as well as manufacturing structures and storage facilities, all of which point to a thriving and flourishing settlement. Apparently, its fortune was also determined by proximity to the religious area. Although monumental or substantial remains are not yet visible (if any were ever constructed!), the votive sphere at Cannicci clearly revolved around fertility cults and offerings [,]. Terracotta uteri were predominant in the ancient votive deposits and were accompanied by small terracotta heads and statuettes (Figure 5). The settlement relied on agrarian economy, and also on craftsmanship. The proximity to the sanctuary also meant that the inhabitants could produce some of the necessary offerings and special requests of the sacred place: black gloss ware and ex-votos, both in metal and pottery, were produced here in specialized and seasonal workshops. The excavations brought back to light the heavy background noise of these activities. A large amount of waste testifies to the intense production of metal objects, domestic ware and luxury black gloss ware vessels (Figure 6). As the excavations grew bigger in 2019, another dwelling of the village was investigated; the remains of a large facility appeared, with one room containing at least 7 dolia (Figure 7) [].

Figure 3.

Aerial view of the late Etruscan and Republican settlement at Podere Cannicci.

Figure 4.

Results of the geophysical investigations at Podere Cannicci. Remains of underground structures are clearly visible through the ARP resistivity, showing a wider settlement covering some 4 ha.

Figure 5.

Some of the votive offerings collected during the 1989–1990 excavations at Podere Cannicci; (a) represents a terracotta face; (b) represents one uterus; (c) is a clay statuette, maybe representing Minerva.

Figure 6.

Some of the pottery wastes recovered during the last two excavations seasons at Podere Cannicci.

Figure 7.

Aerial view of excavations trench (Area 1000) showing the remains of a dwelling with seven dolia still in situ. The structure was shown in the results of the geophysical campaigns.

This vibrant community of worshipping and industrious farmers and artisans came to an end when the Social War between Marius and Sulla reached this part of Etruria []. Sulla’s troops showed no mercy and the settlement at Cannicci was set on fire, its houses never rebuilt, and people dispersed in the surrounding territory if not killed. What was once a dynamic settlement in between religion, agriculture and craftsmanship, was, at this point, destroyed and never occupied again.

The IMPERO Project also investigates a medieval site. As one of the tasks of the research is to understand the changes that occurred between the classical and the modern world along the valley of the Ombrone river, it was necessary to excavate the remains of Castellaraccio di Monteverdi, a fortified hilltop settlement facing the river and a collapsed medieval bridge that crossed it [,,] (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Aerial view of the remains of the deserted medieval village of Castellaraccio di Monteverdi.

The excavations revealed the existence of a much larger settlement, developing over at least three main terraces molded across the slopes of the hill. At this stage, parts of the manor house/tower are under investigation, as well as one of the dwellings located on the hilltop. A general mapping of the fortification and of all the visible walls of the castle was carried out, allowing a preliminary understanding of the topography. The thick deposits of rubble that seal the occupation layers of the structures naturally slow down the excavations at this site and, together with the minimal collection of material culture available, at this stage it is still rather early to advance significant hypotheses on the chronology of the settlement, as well as on the structures it contained and their original functions. An interesting aspect was the discovery of a number of fragments of a late 4th century BC dolium amidst and at the bottom of a rubble context. This may hint at the possibility that a late Etruscan phase can be documented one day on the hilltop of Castellaraccio, providing a unique case for this territory. Although Etruscan settlements are quite often present at the very bottom of medieval stratigraphies and structures, the area of Civitella Paganico, as well as all the middle valley of the Ombrone river, is rather devoid of Etruscan sites.

Academically then, the IMPERO Project sits at the intersection of a number of large debates, spanning from the organization of the historical landscape and its settlement networks to the rise and fall of ancient economies. It investigates commerce and trade along riverine and terrestrial routes and embraces the wider Mediterranean and its micro and macro ecologies to reconstruct the historical identity of a place, Paganico, and its territory. In engaging with these crucial questions of research, the project also attempts to involve local communities in the interpretative process. Interestingly enough, this second task proves to be the most challenging, requiring us to seek new narratives and tools for transmitting the history of a settlement, the construction of historical identities, and the sense of authenticity that comes from our archaeological research to local communities and wider audiences. Despite its challenging nature, the communication and dissemination of authentic stories about the places we investigate remains a fundamental responsibility that we, as a scientific community, must fulfill.

3. A Digital Venture for the Project

As mentioned in the brief introduction of this paper, archaeologists are currently facing new challenges in providing for the kinds of authentic experiences that international tourists and local communities increasingly seek while visiting historical sites.

Undoubtedly then, our discipline is now engaging with new methods, practices and approaches to disseminating our interpretations of sites and settlements. Engagement with local communities, placemaking, the accessibility of archaeological areas, and the visual dissemination of artifacts and structures are just a few examples of a new vocabulary that archaeology must integrate into its research.

In this spirit, an increasing number of archaeological projects is committed to public archaeology. We have the moral duty to open the doors of our sites and to shape new narratives that might attract wider audiences, helping to produce sustainable economic strategies for archaeological places. We are experiencing a new revolution in the use of visual art that is no longer confined to scholarly publications and academic treatments of the past. Visual art and the possibility of personal interaction may be one of the keys to engage with local communities and imbue our work as historians with authenticity and identity. The moment could not be better: as we witness a growing trend of nationalistic movements, whose propaganda is based on falsified myths and misrepresented historical reconstructions, in a world that seems to prefer to erect walls and barriers, archaeology has the power to address the reality of the past and to construct bridges between history and local communities, to make places in lieu of non-places.

Following Marc Augé’s definition of non-places as spaces of vulnerability where members of society are helpless, since the non-place neither provides nor transmits any sense of belonging to a culture or authentic history [], at the IMPERO Project we have started to build these bridges between the academic community of archaeologists and specialists, and the local, wider community. We believe that the latter are the final recipients of our work. Our research should produce an authentic reconstruction of the historical changes that occurred, in our specific case, along the flow of the middle valley of the Ombrone river. Our two sites, the late Etruscan and Republican sanctuary area and the medieval deserted hilltop village, serve the purpose of our experiment with placemaking. As we have seen, each settlement tells stories of different social and cultural identities, struggling and melting together in the crucial passages between the Etruscan period, the Roman era and the transformations of the intricate world of the Middle Ages. It is challenging, however, to relay our research to the modern community of farmers and rural inhabitants who live in the area around Paganico. This community, who might well represent the very descendants of the ancient settlement we study, will always experience barriers in learning about its past unless we create the means to disseminate our results and help them construct their identities, making Cannicci a place for their stories and narratives. How can we transform an archaeological landscape of destruction and abandonment, with scattered elements, into something tangible and understandable for wider audiences? How can we transmit the importance of those rubble contexts in terms of social and historical identities?

Our experience at the IMPERO Project has its roots in a previous attempt that, although much more traditional in its approach, had the chance to quantify the interest of a general audience and to seize the opportunity of creating a place. It is fair to conclude that the attempt was successful overall, but it also failed to develop into something more structural and substantial.

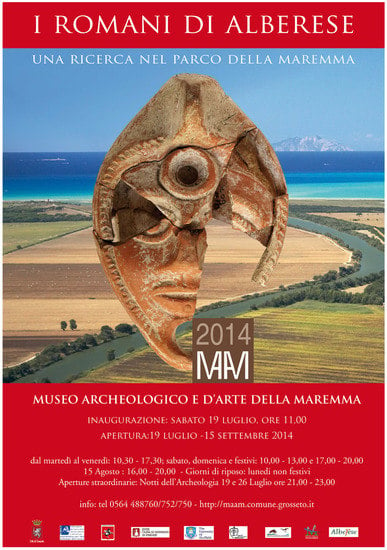

Back in 2009, an independent research project began in the area of the Maremma Regional Park in south Tuscany. Known as the Alberese Archaeological Project, it led to the excavation of three important Roman sites along with the Tyrrhenian coast: the sanctuary area of Diana Umbronensis [], the manufacturing district at Spolverino [,], and the positio of Umbro flumen [,] (Figure 9). In 2014, when these excavations were almost completed, the research team decided to organize an archaeological exhibit to display some of the objects and to disseminate the results of the project. This was of vital importance, as the sites were not accessible nor open to visitors but operated on public land and used public funds. Moreover, the project took place in the protected landscape of a regional park whose coasts and nature trails attract thousands of tourists annually. The exhibition was also a first opportunity to introduce local communities and regional institutions to the cultural heritage present within this protected area. Titled “I Romani di Alberese” (Romans at Alberese), the exhibit opened on 19 July 2014 at the Archaeological Museum of Grosseto (Figure 10) and was by all measures a success. Although reduced in size to only 10 display cases and a variety of Roman objects, it managed to attract the attention of some thousands of tourists and was, as a result, extended three times before moving to the headquarters of the regional park in Alberese for another year. Unfortunately, we were not able to capitalize fully on the results and allurement that the exhibit provoked in almost two and a half years and about 10,000 visitors. What we created was supposed to be the first step towards the development of a series of archaeological trails within the regional park, starting from the area of the sanctuary of Diana Umbronensis located on the main road leading tourists to one of the most beautiful and crowded beaches of Tuscany. We began to plan an archaeological area that could guide visitors through the meanders of the historical stratigraphy that was patiently removed and interpreted. Smart panels were to provide the necessary link between a traditional interaction with the archaeological site and the use of mobile devices (smartphones and tablets) to view 3D reconstructions and models of the Roman architecture and objects (Figure 11 and Figure 12). In essence, we hoped to migrate the physical exhibition onto any personal device, so that the experience of discovering and learning about an archaeological site could follow the visitors to their homes. Tags and specific targets would have been used to recreate the otherwise hidden settlement at Spolverino, a stunning Roman manufacturing district sealed under almost two meters of alluvial clay. Unable to be left in open-air, the idea was to use virtual reality to represent it visually and engender appreciation of its history (Figure 13 and Figure 14). Finally, at Umbro flumen our intention was to use digital means to recreate the settlement and the original Roman coastline on which it sat in the 2nd century BC. Nowadays the sea is more than 4 km away from the Roman positio, as far as our possibilities of bringing these plans to fruition. The attempt failed for a number of reasons. Most likely, however, it was due to fact that the project was too ambitious to be realized. The time was not yet right, and the costs of such a move were too high to be covered by a humble, independent project. None of the main political actors believed in the potential of this idea, seen as too grand for a provincial location that aspires to survive rather than advance.

Figure 9.

Aerial views of the three sites investigated in the area of Alberese. (a) shows the sanctuary dedicated to Diana Umbronensis; (b) shows the manufacturing district at Spolverino, while (c) shows the remains of Umbro flumen.

Figure 10.

Banner of the Exhibit “I Romani di Alberese” opened in 2014 and showing the results of the excavations at Alberese.

Figure 11.

Masterplan for the creation of a smart panel using tablets and GPS at Alberese.

Figure 12.

3D reconstructions of the area at Alberese in the Roamn period. In the front, the sanctuary area of Diana Umbronensis, looking north towards Umbro flumen and Spolverino. Note that also the landscape and natural environment were reconstructed to show the original seacoast line.

Figure 13.

Archaeological plan of the excavations at the manufacturing district of Spolverino–Alberese.

Figure 14.

3D rendering of the manufacturing district of Spolverino–Alberese.

As too often happens, the archaeological interest in Alberese began to dwindle. Settlements were studied, most of them published or soon to be, and historical questions (for the moment) answered. It was time, then, to abandon this part of Tuscany and try to make some places somewhere else.

As the IMPERO Project continues its main scientific research, a different approach to communicating and placemaking is happening. Having learned from previous failures at Alberese, the project decided to invest even more into future technologies.

We decided to make extensive use of 3D modeling, augmented reality reconstructions, and web-based information to make our research accessible to everyone.

Our new experiment with placemaking started at Podere Cannicci. Its more accessible location and lower density of archaeological contexts immediately allowed for a more rapid extension of research which could expose much of the settlement in just three years of investigations. Unfortunately, the presence of heavy collapses of wall structures (some even up to over two meters deep) led to a logistical slowdown of the ongoing investigations at Castellaraccio, where we hope to initiate a project redeveloping the area as a tourist attraction in the immediate future. Furthermore, as we had anticipated, a series of data regarding the function and possible interpretation of the classical site was already available due to the rescue excavations in the late 1980s.

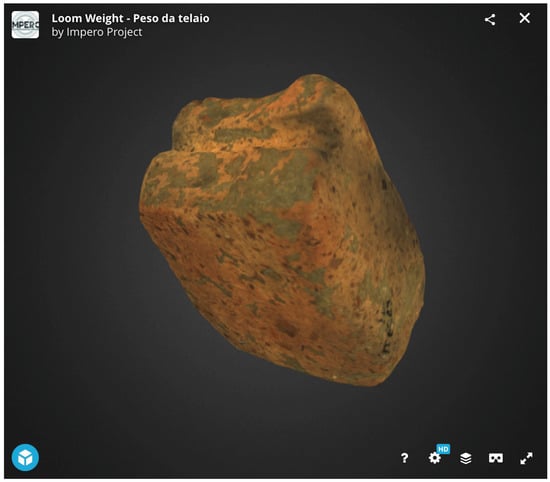

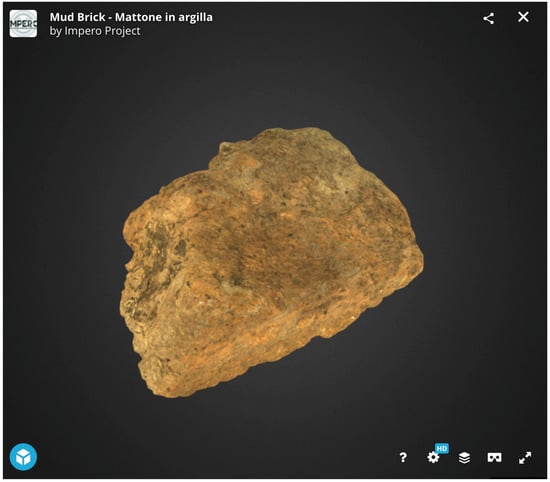

Once the site was chosen, the first step was to identify the assemblages that we may use to support our placemaking project; in other words, we needed to define a strategy for artistic visual design. The choice fell on using building materials, votive offerings and peculiar objects as inspiration. These all represent quintessential elements of our site: they describe the way rural dwellings were built, showcasing skills and techniques that are still present in Tuscan landscapes of the countryside, as well as representing everyday objects that functioned to sustain the communities in the past (Figure 15 and Figure 16). They serve to create a bridge between the past and the present of our rural communities, a trait d’union of cultural identities that are handed down from generation to generation. The votive offerings, mainly terracotta uteri, symbolize prosperity and fertility, as we have seen previously. We attempt to match this cult with the need for descendants (mostly men as they were necessary for working the land and joining the army), although we can also address these objects as a request for fertility for the fields (keeping in mind that in the Etruscan and Roman times, economy was largely based on agricultural goods). Those votive offerings bonded ancient Etruscans and Roman colonists to a land and fertile soils that still guarantee incomes and revenues to the local communities today. The skilled artisans that molded terracotta objects and forged bronze statuettes of bovines were protected by Minerva, and their tradition and heritage has survived into modern Paganico and its environs. The land and the fields around Podere Cannicci, for example, produced grape, olives and wheat that were stored and managed by patient farmers. Archaeology was able to retrieve the traces of these forms of production. Dolia still in situ tell a story of seasonal work, of the process of transforming grape into wine, olives into oil (Figure 17), a tradition that is still present and vivid in Tuscany. 3D reconstructions helped us visualize these practices, connecting the local, modern communities to their past and their ancestors.

Figure 15.

3D model of a loom weight founds during the excavations at Podere Cannicci.

Figure 16.

3D model of a mud brick recovered during the excavations at Podere Cannicci.

Figure 17.

3D reconstruction of the dwelling at Podere Cannicci where seven dolia were found still in situ during the 2019–2020 excavation seasons. The picture shows an overlay between the archaeological deposits (the earth-beaten floor and remains of the walls) and the 3D reconstruction built on top of it.

Our 3D models and reconstructions followed two different methods and perspectives [,,].

Some of the material culture that we decided to digitalize was selected in order to represent, as previously mentioned, particular aspects of everyday life at Roman Cannicci that can still be experienced in modern Paganico. Once the selection was done, we used a portable Artec Spider 3D scanner to digitalize the artefacts and Artec Studio Pro 11 to create the digital models; we then uploaded the final renderings onto SketchFab (https://sketchfab.com/imperoproject). By navigating the website, the visitor will notice also the presence of almost the entire collection of votive offerings retrieved during the excavations in 1989–1990. This decision was made as the objects are currently displayed at the Archaeological Museum in Grosseto but we wanted to make them available to everyone.

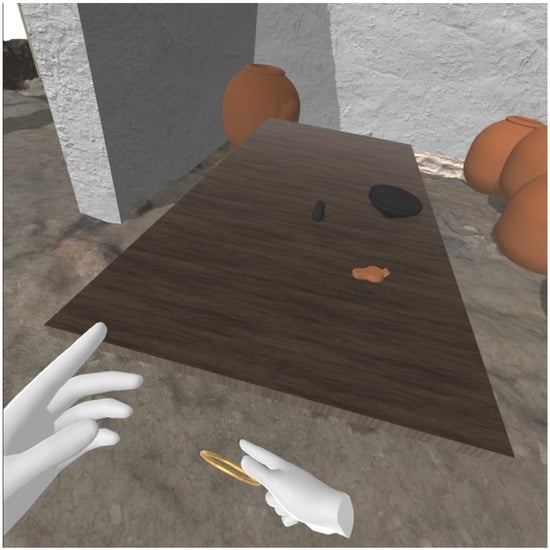

Our 3D reconstructions are a little more subjective, as one can easily expect. We started with the precise recording of the archaeological strata and evidence during the excavations at Podere Cannicci. As we excavated the different deposits, we mapped the material culture retrieved and created a digital plan of the room with dolia. Our very first attempt to visualize this particular space included the elevation of the clay walls on top of the physical remains and the juxtaposition of 3D models of dolia on the actual remains that were still in situ. The carbonized wooden table was 3D reconstructed on the exact place of its rediscovery in 2019, while the objects that we decided to render were those collected during its excavations. As for the architectural reconstruction of the possible porticoed area, we utilized once again the real data coming from the excavations. Two stone pillar bases were exposed in 2019, with a carbonized beam in between them; hence, we decided to render this type of construction as shown in Figure 17. Obviously, we collected some of the rooftiles that allowed us to hypothesize the final reconstruction and we relied on previous renderings of similar facilities [].

Finally, we needed to make our work as archaeologists understandable. Why should public institutions fund our research? What are we giving back to the public in terms of monuments and art?

Once again, we relied heavily on digital tools. We faced the necessity of allowing people to visualize our work, how we date structures and sites, how we reconstruct historical landscapes, and how we uncover identities and make places. Think for a second of Pompeii or Herculaneum, or the Coliseum. These are quintessential, authentic places that transmit certain values from the past, identities that are preserved and shown daily to hundreds of thousands of tourists. Then we return to Podere Cannicci: humble stone foundations, melted mud bricks and shattered pottery vessels filling a large drain. The task of transmitting value to these features in terms of historical authenticity is enormous. Our rural settlement, the place where Sulla sealed his conquest of the ager Rusellanus, has no monumentality. Augmented reality helped us fill this void. Through the use of this technique, we were able to start a process of communicating our research and our historical vision of the past, our visual art. People now can see where votive offerings were found, or how we date our strata and why we use stratigraphy (Figure 18). We wanted to make our research reliable and understandable to everyone. This task will continue during the next seasons, when we will implement our holistic and technological approach to the historical reconstruction and dissemination of visual art.

Figure 18.

The picture shows one Roman drain at Podere Cannicci with a tag. Our experimental app proposes an augmented reality reconstruction of the archaeological stratigraphy there contained and of the material culture used to date it. In this way, the user will see the physical remains of the drain (upper part of the picture) and the reconstructed facility in augmented reality with details of the archaeological deposits (lower part of the picture). The app will be accessible via personal devices such as tablets and smartphones.

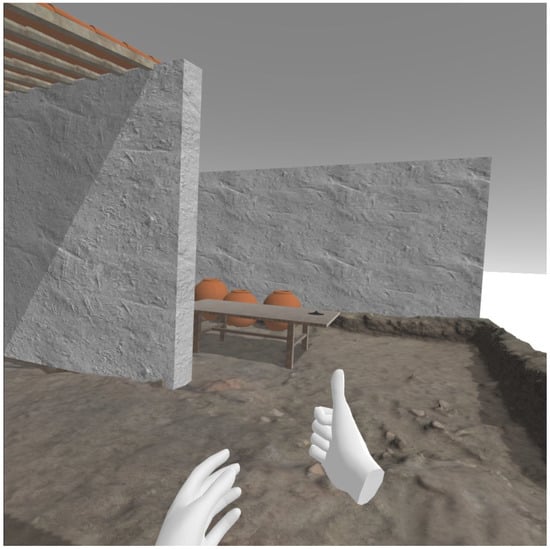

It is for this reason that we open a new direction in our development project for Podere Cannicci. Thanks to the generous support of a research grant from the Digital Scholarship Studio and Network (DSSN) at the University at Buffalo, in fact, the project was able to purchase two Oculus Quests. Our idea is to recreate a virtual and augmented reality environment, perfectly interactable for the user, where the Etruscan and Republican settlement comes back to life. The idea was suggested by a number of other applications of this technique or attempts to [,,]. The user should be able to walk through the different spaces that archaeology uncovered during the excavations, picking up objects, seeing and experiencing a virtual scenario where all the details are based on a precise, scientific reconstruction of the material culture and buildings. By developing a specific app for the Oculus Quest, visitors will be able to use their own devices, although some will be available onsite. In this way, by recreating the structures and life of the site, the project will overcome the limits that a humble settlement like Cannicci presents. The lack of monumentality can be compensated for by the virtual reconstruction of the spaces, of the people, and of the objects, still allowing some flexibility in updating the data (Figure 19 and Figure 20). In fact, we must keep in mind that this solution will allow for updates and ongoing development as we increase the number of reconstructions and keep pace with excavations. In this way, the maintenance and printing costs of traditional panels will certainly be reduced. At the same time, since virtual experiences do not require physical presence onsite, visitors will be able to interact with the Etruscan and Roman site at Cannicci remotely, from the comfort of their home. This part of the project was set to start during the 2020 research season at the Impero Project; however, the outbreak of Covid-19 forced us to cancel all activities. Nonetheless, our team is already working on the app and the reconstructions. We hope to deliver this innovative experience in summer 2021.

Figure 19.

Our Oculus Quest experiment—In this case the user can navigate inside the virtually reconstructed Roman buildings at Podere Cannicci. Here the user interacts with objects found on the remains of a carbonized Roman table.

Figure 20.

Our Oculus Quest experiment—The user is navigating through the 3D reconstruction of one of the rooms at Podere Cannicci, where archaeology retrieved the remains of a wine cellar with 7 dolia still in situ as well as a carbonized wooden table.

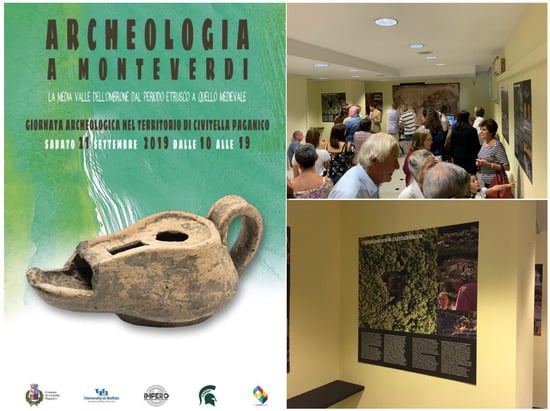

In the meantime, in September 2019, we opened an archaeological exhibit in Paganico where visitors could interact with artifacts and sites. The exhibition was possible through the generous support of a research grant by the Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development of the University at Buffalo.

The exhibition was divided into a series of rooms with panels where the various stories related to the excavations at Podere Cannicci and Castellaraccio di Monteverdi were explained (Figure 21). Moreover, through the use of QR codes, visitors were able to visualize artifacts that could not be displayed, learn their stories, and assimilate and appropriate their historical identities. Technology also allowed us to disseminate our preliminary results through the establishment of a web-based virtual exhibit. People from all over the world can still visualize our work, debate our theories and study our artifacts (www.imperoproject.com/archeologia-a-monteverdi). Our intention is to renovate the exhibition every year, showing different aspects of our research, as well as of the historical landscapes of the municipality of Civitella Paganico.

Figure 21.

The exhibition “Archeologia a Monteverdi”at Paganico in September 2019.

4. Measure of Success and Public Opinion

Since day one of our project, we decided to have an open access profile, and to extensively use the Internet as a way to communicate and measure the success of our research. In 2017, the website of the project was set up (www.imperoproject.com). This serves as a collector of all the information gravitating around the excavations and the historical sites we investigate annually. Almost immediately after, our Facebook page was created (https://www.facebook.com/imperoproject) while Twitter, Instagram and Youtube accounts were added only during the summer of 2017 as we began the excavations at Podere Cannicci. Social media have finally acquired their primary role in the field of humanities and the communication of archaeological research has certainly benefited in terms of visibility and access to information. Our social media approach at the Impero project took advantage, once again, of our previous experience at Alberese. During the excavation campaigns, the website and social pages are updated on a daily basis to make our research transparent and immediately reviewed and commented on. The excavation journals are published at the end of each day, as well as all the 3D models, including those in progress, in order to receive possible feedback from external users. We have chosen to use English as the official language, instead of the more comfortable Italian, to favor a wider dissemination and understanding of the contents we publish. This way of conveying raw excavation data immediately (without waiting for the publication of each single final report) and of showing the subsequent steps towards the interpretation of our contexts is certainly inspired by previous ventures, such as the pivotal project at Miranduolo, in the municipality of Chiusdino, Siena (http://archeologiamedievale.unisi.it/miranduolo/); here, the team of the University of Siena has always made available all the excavation information. It is a method of data-sharing that not only inspired us, but the philosophy and application of which we share and engage with [].

The large involvement of digital technologies and of the Internet is also useful to measure and understand public engagement with our project. The website is accessed from all the continents, especially in the summer time when we have fresh new contents to share. It is the moment when we publish our daily journals of excavations (from both Podere Cannicci and Castellaraccio) and digital interactions spike. In absolute terms, every year saw an increment of visitors: we started with 286 visitors and 997 visualizations in 2016, to reach 3699 visitors and 11,887 visualizations in 2019. The last set of numbers was boosted by the opening of the virtual exhibition in September 2019, allowing us to understand that people from all over the world were able to virtually visit the exhibition, as well as interact with our 3D models and reconstructions. Due to the Coronavirus outbreak in 2020, we were not able to constantly update our contents; the number of both visitors and visualizations decreased accordingly, unfortunately. Finally, we will implement our methods of measuring public engagement, especially when we organize our archaeological open days; these events are usually attended by hundreds of local people and they can turn into a unique occasion to collect feedback and comments on our job as placemakers.

5. Conclusions

I would like to conclude this paper with a few additional remarks. Only three years ago, the territory of Civitella Paganico was confined to amateur studies, where, however, some of the great potentials of a multi-faceted and stratified landscape were already emerging. The few data on the Etruscan period were accompanied by the excavation of the large Roman thermal complex of Pietratonda [,], but still lacked the ability to identify the more complex and ramified settlement dynamics. The Middle Ages were isolated to a few publications on the birth of the “borgo franco” at Paganico, and only some works attempted a broader reading in light of extensive field surveys []. The archaeological activities of our project almost immediately intersected with those undertaken in the nearby necropolis of Casenovole by the Ass. Arch. Odysseus, where a group of local archaeologists is discovering some late Etruscan and Republican tombs [,,]. We entered into a composite archaeological and historical scenario where data was fragmented, and we are pushing to create synergies among the different agents. Without jeopardizing the necessary independence of individual research projects, we are trying to find a reasoned solution to the management, enhancement and transmission of the cultural heritage of the entire municipal area. It is for this reason that we are planning the possibility of a Diffused Museum for the territory, open to a classic showcasing of historical areas as well as to innovative digital communication techniques. What we are trying to create is a complete and constant interaction between the visitor and the places of the historical identity of this territory and its stratified landscapes. Furthermore, through the integration of an augmented reality platform (Oculus Quest), I want to immerse the visitor inside the settlements and material culture that we investigate annually. Through this project, we want to convey the historical identity and authenticity that emanate directly from the archaeological knowledge of the territory. The challenge is to be able to connect local communities to their cultural roots, to the economic aspects of a landscape that have spanned the centuries unchanged. At the same time, we intend to connect tourists to landscapes and historical realities through the possibility of visiting, studying and coming to know the places we have investigated even remotely. For this reason, our website is already transforming itself into an information portal and, over the years, we will develop it in order to have different educational and interaction levels appropriate for a variety of user experiences.

The task is as arduous as it is fascinating. Being able to connect global tourism and local communities to the authentic narratives of a territory so rich in history can only emerge as a generational goal. In other words, we are preparing to become placemakers for the municipality of Civitella Paganico. We are sure that it will be an engaging journey to rediscover the historical memories and cultural identities of a precious corner of the middle valley of the Ombrone river.

Funding

This research was funded by the University at Buffalo, Office of the Vice-President for Research and Development (OVPRED), as well as by the University at Buffalo Digital Scholarship Studio and Network (DSSN). The archaeological excavations and geophysics at Podere Cannicci were also supported by the New York Community Trust.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the forthcoming publication of monographs and articles related to the ongoing project.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Michelle Hobart (The Cooper Union, New York) and Todd Fenton (Michigan State University) for their constant help, support and commitment with the IMPERO Project. Josef Souček (National Museum of Prague) diligently provided all the 3D models and augmented reality data and pictures. Tyler Johnson (University of Michigan) kindly edited the initial version of this paper, providing feedback and useful comments; it goes without saying that all the possible remaining mistakes are all my fault. The Giannuzzi Savelli family allows the excavations at both Podere Cannicci and Castellaraccio di Monteverdi and I am always grateful to them. A special thank you goes to Alessandro Carabia (University of Birmingham) and Edoardo Vanni (University of Siena) who direct the excavations at our archaeological sites. The mayor of Civitella Paganico, Alessandra Biondi, has been always supportive of the project, and thanks to her encouragement we were able to set up the archaeological exhibition in Paganico in 2019–2020. Last, but not the least, a thank you to all the students who took part in our excavations between 2017 and 2020; without their efforts we would not have any story to tell.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Hodges, R. The Archaeology of Mediterranean Placemaking: Butrint and the Global Heritage Industry; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, R. Archaeologists as Placemakers: Making the Butrint National Park. In Butrint 4: The Archaeology and Histories of an Ionian Town; Hansen, I.L., Hodges, R., Leppard, S., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Holtorf, C. On Pastness: A Reconsideration of Materiality in Archaeological Object Authenticity. Anthr. Q. 2013, 86, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondio, F.; Campana, S. 3D Recording and Modelling in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage: Theory and Best Practices; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, M.; Siliotti, A. Virtual Archaeology: Re-Creating Ancient Worlds; Harry N. Abrams: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, B.R.; Caraher, W.R.; Heath, S. Visions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean Archaeology; University of North Dakota: Grand Forks, ND, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gaitatzes, A.; Christopoulos, D.; Roussou, M. Reviving the Past: Cultural Heritage Meets Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2001 Conference on Virtual Reality, Archeology and Cultural Heritage—VAST ’01, Glyfada, Greece, 28–30 November 2001; ACM Press: Glyfada, Greece, 2001; pp. 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A. From Villa to Village. Late Roman to Early Medieval Settlement networks in the ager Rusellanus. In Encounters, Excavations and Argosies: Essays for Richard Hodges; Moreland, J., Mitchell, J., Leal, B., Eds.; Archaeopress Archaeology: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A.; Hobart, M. Scavi nella tenuta di Monteverdi a Civitella Paganico. Boll. Archeol. Online 2019, 10, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A. New data for a preliminary understanding of the Roman settlement network in south coastal Tuscany. The Case of Alberese (Grosseto, IT). Res. Antiq. 2016, 13, 243–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hobart, M.; Carabia, A. Excavation at Castellaraccio (Civitella Paganico—GR) 2018. J. Fasti Online 2020, 459, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, G. Aspetti del popolamento della media Valle dell’Ombrone nell’antichità: Indagini recenti nel territorio di Civitella Paganico. J. Anc. Topogr. 2005, 15, 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, F. La stipe votiva di Podere Cannicci (Civitella Paganico, Grosseto). In Un’anima Grande e Posata. Studi in Memoria di Vincenzo Saladino Offerti dai Suoi Allievi; Bazzecchi, E., Parigi, C., Eds.; Scienze e Lettere: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 106–122. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A.; Vanni, E.; Morelli, G.; Woldeyohannes, E.; Hobart, M. The second archaeological season at Podere Cannicci (Civitella Paganico—GR). J. Fasti Online 2019, 451, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, F. La stipe votiva di Podere Cannicci a Paganico (Civitella Paganico). In Le Vie del Sacro. Culti e Depositi Votivi Nella Valle Dell’albegna; Rendini, P., Ed.; Nuova Immagine: Siena, Italy, 2009; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, F. Votivi Anatomici Fittili. Uno Straordinario Fenomeno di Religiosità Popolare dell’Italia Antica; Ricerche; Ante Quem: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A.; Vanni, E.; Brando, M.; Woldeyohannes, E.; McCabe, M.D., III. The Third Archaeological Season at Podere Cannicci (Civitella Paganico—GR). J. Fasti Online 2020, 491, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Keaveney, A. The Social War 90 BC. In Rome and the Unification of Italy; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 2005; pp. 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Farinelli, R. La valle dell’Ombrone dalla tarda antichità al basso Medioevo. Il contributo delle indagini storico-archeologiche alla storia del popolamento e dei flussi di traffico. In Ombrone. Un Fiume Tra due Terre; Resti, G., Ed.; Pacini: Ospedaletto, Pisa, Italy, 2009; pp. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Augé, M. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity; Verso: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A.; Chirico, E.; Colombini, M.; Cygielman, M. Diana Umbronensis a Scoglietto. Santuario, Territorio e Cultura Materiale; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A. Spolverino (Alberese—GR). The 4th Archaeological Season at the Manufacturing District and revi-sion of the previous archaeological data. J. Fasti Online 2014, 320, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A.; Derrick, T. A regional economy of recycling over four centuries at Spolverino (Tuscany) and environs. In Recycling and the Ancient Economy; Duckworth, C., Wilson, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 359–382. [Google Scholar]

- Sebastiani, A.; Chirico, E.; Colombini, M. Grosseto Località Alberese: Indagini nel sito marittimo di età romana nell’area di Prima Golena. Not. Della Soprintend. Ai Beni Archeol. Della Toscana 2016, 11, 451–454. [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, E. Prima Golena (Alberese, GR): Umbro flumen una mansio-positio a servizio della viabilità. Boll. Archeol. Online 2019, 10, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Garstki, K. Virtual Representation: The Production of 3D Digital Artifacts. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 2016, 24, 726–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, S. Challenging Heritage Visualisation: Beauty, Aura and Democratisation. Open Archaeol. 2015, 1, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherron, S.P.; Gernat, T.; Hublin, J.-J. Structured light scanning for high-resolution documentation of in situ archaeological finds. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009, 36, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.; Vermeulen, F.; Corsi, C. Radiography of the Past—Three Dimensional, Virtual Reconstruction of a Roman Town in Lusitania. Int. J. Herit. Digit. Era 2012, 1, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyttleton, J.; Herron, T. Through the Virtual Keyhole. Archaeol. Irel. 2019, 33, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Knabb, K.A.; Schulze, J.P.; Kuester, F.; Defanti, T.A.; Levy, T.E. Scientific Visualization, 3D Immersive Virtual Reality Environments, and Archaeology in Jordan and the Near East. Near East. Archaeol. 2014, 77, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.H. Virtual Heritage. J. East. Mediterr. Archaeol. Herit. Stud. 2014, 2, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, M. La “Live Excavation”. In Proceedings of the VI Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Medievale, L’Aquila, Italy, 12–15 September 2012; Redi, F., Forgione, A., Eds.; All’Insegna del Giglio: Florence, Italy, 2012; pp. 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, G. Civitella Paganico (GR). Scavi alle terme romane di Pietratonda. Not. Della Soprintend. Ai Beni Archeol. Della Toscana 2005, 1, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Cabarrou, M.; Darles, C.; Pisani, P. Essai de description d’un bâtiment des eaux de Toscane, l’édifice mystérieux de Pietratonda (Gr). L’antique Partag. 2012, 90, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcocci, A. Contributo alla Carta Archeologica del Comune di Civitella Paganico (GR); Università degli Studi di Siena: Siena, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, G.; Lippi, B.; Mallegni, F. Civitella Paganico (GR). La tomba del Tasso di Casenovole presso Pari. Not. Della Soprintend. Ai Beni Archeol. Della Toscana 2007, 3, 446–451. [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri, G. Tomba del Tasso di Casenovole presso Pari (Civitella Pganaico). In L’occhio Dell’archeologo. Ranucci Bianchi Bandinelli nella Siena del Primo ’900; Barbanera, M., Ed.; Silvana: Milano, Italy, 2009; pp. 125–126. [Google Scholar]

- Turchetti, M.A. Civitella Paganico (GR). Casenovole: La Tomba delle tre Uova. Not. Della Soprintend. Ai Beni Archeol. Della Toscana 2011, 7, 370–371. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).