1. Introduction

Within this paper, we examine and frame the connection between the past and the present, particularly the archaeological past and present heritage within Maya anthropological archaeology in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. The past is not a simple, single temporal line, but rather one that is complex and twisted—one that starts and stops—and one that is differentially identified and recognized in the present. One of Yucatan’s pasts is a distant past focused upon the ancient Maya—the pre-16th century Maya of Chichen Itza, Uxmal, Coba, and Tulum [

1]. This past is identified as the definitive story of the Maya people and the Yucatan Peninsula. The second past is a more recent vision, following Spanish contact and focusing upon the past 200 years—including the rebellion, often called the Caste War of the Yucatan (or the Maya Social War) [

2]. When we turn to the present, we see a landscape of modern Maya towns connected to the growing city of Cancun and the rising tourism industry stretching further south along the east coast of the peninsula to Tulum and beyond. The current promotion of the region by tour agents and government actors alike links the ancient past with the heritage of the Maya people today, disregarding the more recent past [

3].

Mexico, as a nation-state, engages this flexibility in both time and temporality in the creation and maintenance of its national narrative [

4]. The past helped create a state connected to its fight for independence, its revolution, and its deep indigenous past. Mexico’s indigenous history is complex and tends to emphasize the Aztec or Mexica as foundational. The concept of mestizaje is a critical one, that combines an indigenous and Spanish past in the creation of a modern “mixed” population.

However, as we turn to the Yucatan and the southeastern part of Mexico, we find an even more complex connectivity of Mexico to both ancient Maya culture and living Maya within the region. The stories and heritage of the past and present in the southern states of Mexico are framed and negotiated within Maya communities, as well as within the context of tourism and the powerful state and federal governments [

5]. This framing and negotiation has resulted in a story of Maya heritage within the communities of the Yucatan, often more connected to the 19th century rebellion than the ancient past. Heritage stories are flexible and are not based upon an absolute linkage between the past and the present. The Tihosuco Heritage Preservation and Community Development Project, described in detail later in this article, highlights this more recent past, and examines how it can be put to use in the present and future.

2. Background: Anthropological Archaeology

Since the 19th century, archaeology has always been considered a central part of the anthropology discipline in the United States, but it was in the middle of the 20th century when a long and complex conversation was initiated about the role and function of archaeology within anthropology.

Conversations about the goals and methods of archaeology, between Walter Taylor [

6], Gordon R. Willey and Philip Phillips [

7], began to focus and identify the role that archaeology should have within anthropology of the 20th century. This conversation was then extended by the pivotal writings of Lewis Binford, starting in the 1960s [

8]. Binford and other proponents of “New Archaeology” shifted the conversation to one that positioned archaeology as a science with a defined and clear set of goals and methods. We will not recount these debates here. [

9] From the cultural historical approach, to processual archaeology, post-processual, and more recent views, anthropological archaeology remains focused upon the past and the nature of how we, today, interpret that past. This focus upon the past did not change even with the acknowledgement, within post-processual and more recent theoretical and methodological insights, that the positionality of archaeologists in the modern-day world has an impact upon how we view and interpret past communities [

10]. As a result, the field has witnessed a growing tension that relies on a key temporal division: archaeology is about the past; heritage is about the present [

11,

12,

13].

We see a paradox in archaeologists’ views of their own roles. On the one hand, they are scientists. On the other, they are stewards of the human past and thus stewards of human heritage [

14]. Archaeological sites are thus assumed to be the heritage sites of people and communities living today. However, heritage is not just a study of the past—it is how the past is used to structure the present and create the future. [

15]. We cannot assume that interpretations of archaeological sites of the past are directly connected to the heritage of a community or group. That connection might be historically correct, but accuracy is not how identity and heritage are constructed. There is an important and distinctive contrast between archaeological work and interpretations and the way those views are utilized in the construction of the present. If archaeologists desire our work to be meaningful in the here and now, we must embrace all the temporal dimensions of our work—past, present, and future. [

3].

3. Maya Archaeology and Maya Heritage

Following the previous section, we want to make a clear and definable contrast between Maya archaeology and Maya heritage.

Maya archaeology has been, and continues to be, a part of anthropological archaeology, defined by the study of a cultural group that begins to be identifiable around 1500 BCE and continues changing and developing into the present. It has focused on the time period from 1500 BCE to the beginning of the 16th century BCE, with the arrival of the Spanish [

1]. There is a growing field of Maya historic archaeology, focused upon the 530 years following contact [

16,

17]. In addition, there has been extensive ethnographic work with modern Maya people to understand the cultural, social, and economic position of the Maya in the modern world [

18].

A frequent false assumption is that the heritage of Maya people today is directly related to their ancient past—with “the Maya” of the past often described as one of the “great civilizations” of the world. Clearly, there is a direct historical connection between the ancient Maya with modern Maya people today [

19]; however, we must demonstrate, rather than assume, that the heritage construction by people today utilizes and is built upon that ancient past. Modern day nation-states, such as Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Belize, all utilize the ancient Maya past as part of their heritage stories for the creation of and existence of their countries [

4].

However, as we discuss below, not all Maya communities identify the ancient Maya as a primary part of their heritage and modern day identity. This is not to say that Maya people and communities are disconnected from the ancient stories and culture identified and defined by Maya archaeology. The direct linkage is acknowledged and understood, but Maya heritage is not about historical connections nor about truth in history. Rather, it is about how modern day people, in this case people who identify themselves as Maya, construct the stories of their past and history to create a Maya heritage in the 21st century [

3].

Yucatan: Past and Present

The Mexican government and tourist business have co-opted Maya narratives to suit their promotional needs. This framing emphasizes the glories of ancient Maya culture but also eliminates modern Maya people from the present-day landscape.

In Cancun and throughout the Maya Riviera, the story of the ancient Maya abounds. Many cultural and financial resources go towards codifying that story, as is made evident by two large new museums in the Yucatan—Museo Maya de Cancun and the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya in Merida. Today’s Maya communities, at worst, make no appearance or, at best, are a minor appendage to the story of a once great Maya civilization that collapsed and/or disappeared around 900AD. Archaeologists (both Mexican and US American) helped create this story of the Maya past—one that also contributes to the trope that Maya people were dramatically reduced as a culture or civilization by the time the Spanish arrived in the 16th century. This is not just a story for the tourists. The Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) and other forces of the Mexican government often present this to Mexican citizens, including Maya school children, as their heritage. The complexities of this story are seldom explained within a broader context of political and social development and change.

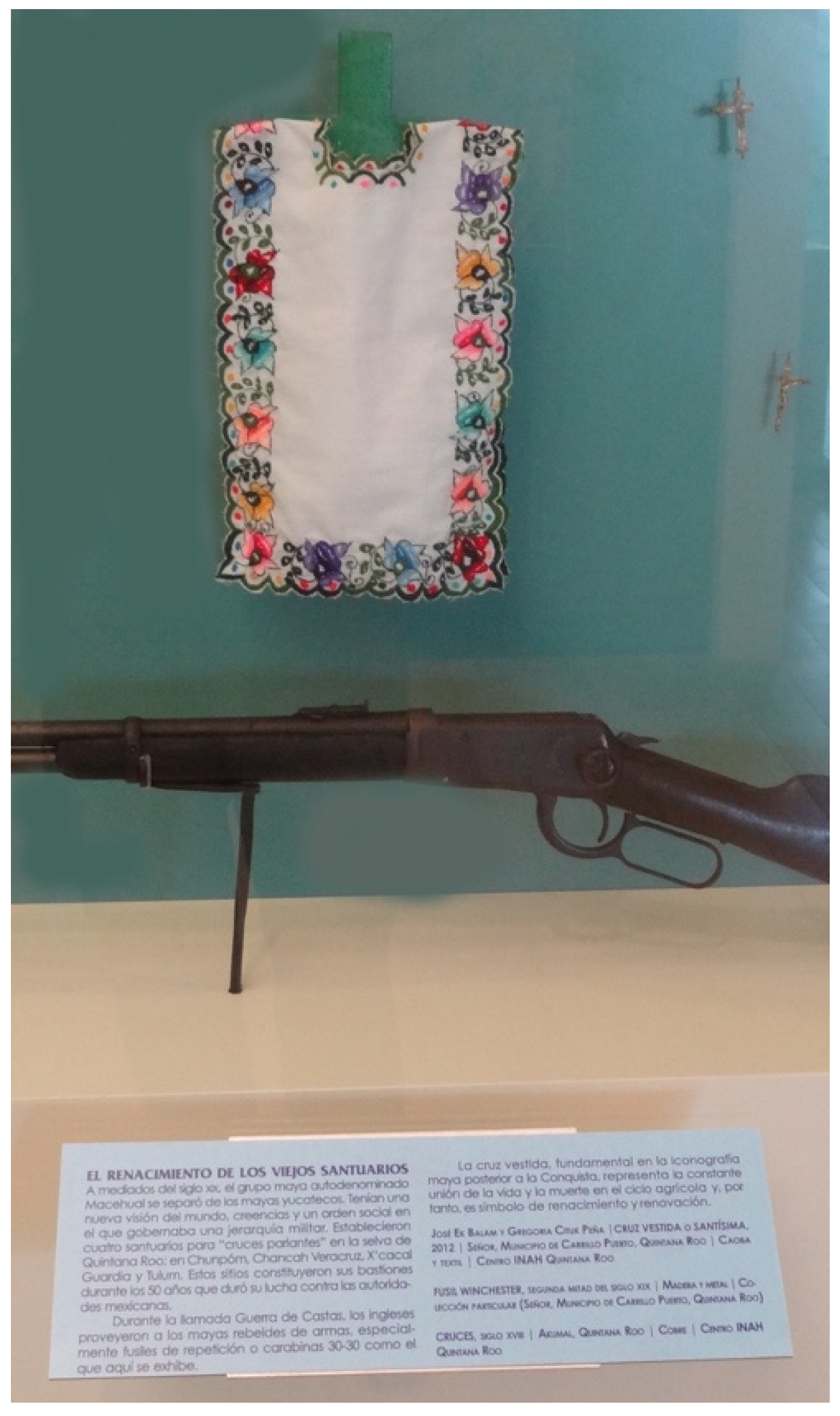

We find that post-revolutionary Mexican national identity reinforces and justifies these structural inequities. Mexico’s identity centers on a romanticized pre-Hispanic indigenous culture, overlaid by a history of Spanish creoles that valorizes an imagined view of mestizaje. Within the Yucatan, part of this national story, often reinforced through archaeology, is the idea that the ancient Maya have disappeared, leaving no real descendants. In fact, the two previously mentioned museums emphasize this cultural framing. The Museo Maya de Cancún is almost entirely about the ancient world, focusing upon the finds and excavations from sites throughout Quintana Roo. There is one vitrine that presents a single photograph and statement about the 19th century Caste War (

Figure 1). There is a slightly larger presence of modern Maya people in the Merida Gran Museo del Mundo Maya.

These modern people, from whom an identity and past have been removed, consist of millions of Maya who form the core of the underclass, providing labor for the construction of and service work within the hotels of Cancun and the Maya Riviera. In the end, the emphasis on a Mexican national identity and a simplistic story for the tourists in Cancun disregards the millions of Maya service people in the region. Modern Maya, unrecognized by those constructing hegemonic narratives about the past, have become an almost invisible cultural group, a service underclass [

20].

4. Historical Background: Tihosuco and the Caste War of Yucatan

4.1. The Caste War (1847–1901)

The “Guerra de Castas (the Caste War)”, also called the “Guerra Social Maya (Maya Social War)”, began in the Tihosuco Parish (where we currently participate in a collaborative heritage initiative, described in detail below) in 1847. The Caste War was one of the most successful indigenous uprisings in the history of the Americas and led to the existence of a Maya state that remained semi-autonomous for over 50 years. Yet, the Caste War was a war of factions—Maya against Mexican, Maya against British, Mexican against British, and Maya against Maya [

21]. Inhabited by Maya peoples for well over three thousand years, the Yucatan had become a political and economic focus for the Spanish colonial powers centered in Merida. By the early 1800s, traditional Maya extended-family networks were breaking down as village political identities and local economic interests increasingly guided the administrative organization of Maya villages and towns across the Yucatan Peninsula [

2,

22].

Following a series of events in the summer of 1847, “the conflagration swept over the eastern three-quarters of the peninsula…as the rebels drew to their cause possibly a fourth of the entire peninsula population” [

22] (p. 3). The demands of the insurrectionists included the abolition of all taxes and the guaranteed right to sufficient land. Despite their success, the Maya forces were never truly united, but multiple Maya factions worked in concert to push their way to the outskirts of Merida. By mid-1848, the Yucatan elite population had been driven to Merida, where preparations were being made to flee the peninsula, leaving it entirely in Maya hands.

For unknown reasons, the rebel forces did not complete their advance upon Merida. Instead, the rebels retreated, many of whom simply returned to their villages. In late 1848, the remaining Maya forces were driven eastward by a renewed Yucatecan military, beginning a 50-year period of isolated fighting and ongoing resistance by the rebels. By the end of that year, it is estimated that over 200,000 people had been killed or displaced by the war.

In late 1850, a small group of Maya witnessed a divine visitation in the form of a talking cross. Though little is known about the establishment of the “cult” of the cross, a new town, Noj Kaj (Chan) Santa Cruz was founded in the eastern Yucatan as the home of this divine miracle. Giving the rebels new hope, the cross reportedly spoke the words of God directly to them, calling for Maya independence and religious autonomy. With newly identified Maya priests, the Talking Cross united a beleaguered population of war-weary Maya with a resurgence of religious hope and rebel spirit. These Maya established control over eastern Yucatan and, through friendly trading networks with the British, managed to maintain political autonomy for almost 50 years [

2,

22].

4.2. Contemporary Heritage Values

The predominantly Maya communities of Quintana Roo, similar to the one we have worked in since 2011, clearly understand their lineal connection to the ancient Maya cultures represented at many local archaeological sites. However, the relatively recent history of the Caste War seems to resonate more strongly throughout the region. The Caste War was a critical period in the creation of the modern Maya as an independent and identifiable cultural group in Central America. It is one of the most important regional events of the Yucatan in terms of the creation of a modern Maya identity. Thus, it is easy to understand the connection people in today’s post-war Tihosuco community have created with the architectural remains from the 19th century that structure their town. The partially reconstructed church remains a reminder of the “blood spilled during the war”, to use the words often heard in Tihosuco (

Figure 2). The 19th century houses, found throughout the center of town, provide a direct physical link of the present to the past. These heritage spaces are seen as harbingers for a brighter future through their preservation.

There is a sort of stretching and snapping back of the fibers of history that is commonly encountered in Tihosuco. The rebellion is often constructed as an almost recent event. The elders of the town, none of whom could have been alive for even the final stages of the rebellion, tell stories of the war as if they had been there. The leaders of the rebellion, Jacinto Pat, Cecilio Chi, Manuel Antonio Ay, and Bernardino Ken, inhabit Tihosuco and the surrounding land today.

For the majority of the region, the future is based upon a mix of economic and social factors: tourism from Cancun or the Maya Riviera and a spirit of continued rebellion and maintenance of a local identity in contrast to Mexican culture, as defined by the nation-state. The future is imbued with both the physical remains of this past war and the spirits of the leaders who brought the Maya to the battlefield. It is a future filled with Maya people, with the growth and development of Maya communities, inhabited by the spirits of the rebellion.

It is a future that people are fighting for. The local state government (Quintana Roo) and the federal government envision very different futures for the region. As stated before, one story de-emphasizes the existence of the descendants of the ancient Maya, and this is the story told to the millions of tourists who visit the coast and the ancient Maya sites. However, the Quintana Roo state and Mexican federal governments have begun to enter the towns and communities located away from the tourists, where this subversive and powerful Maya heritage has taken hold. In entering these towns, the government entities are not just bringing financial resources (or more often, promises of financial resources) but also a new image for the future— an image that domesticates and capitalizes on the story of rebellion and indigeneity in the region.

Every year in late July, Tihosuco hosts a five-day festival to celebrate and honor the start of the Caste War. For many years, this was an internal celebration, structured and organized by the town and neighboring local communities, including Tepich. A few local government officials might have come for the opening or closing, but it was quite contained in its form and nature. Stories of the war and the heroes of the Caste War were presented through plays, music, photographs, and presentations. It was a celebration looking at the past in the present with an eye to the future.

Beginning in 2013, this celebration began to take on a more overtly political edge. Rousing speeches highlighted the importance of Maya culture and the war, often ending in a cry of “Viva los Mayas! Viva los Heroes de la Guerra!”

However, at almost the same moment, state politicians arrived and presented a very different picture of the Maya and the rebellion. We remember one tall Quintana Roo official saying, “The Maya Caste War or Maya Social War is important for all Mexicans and all people of Quintana Roo. For this rebellion teaches all of us how to be good Mexicans and good people of Quintana Roo.” The Caste War was a rebellion against Mexico and against the government. The future, as presented by this government official, domesticates the rebellion and brings it into the imaginary for Mexico and Quintana Roo—not as a rebellion against the system, but as a teaching moment for the enactment of good citizenship in the present and the future. This sort of co-optation is, perhaps, inevitable, but our collaborative heritage work shows that it is possible for people to take charge of their local histories and resist through the work of self-representation and advocacy for the futures of their communities.

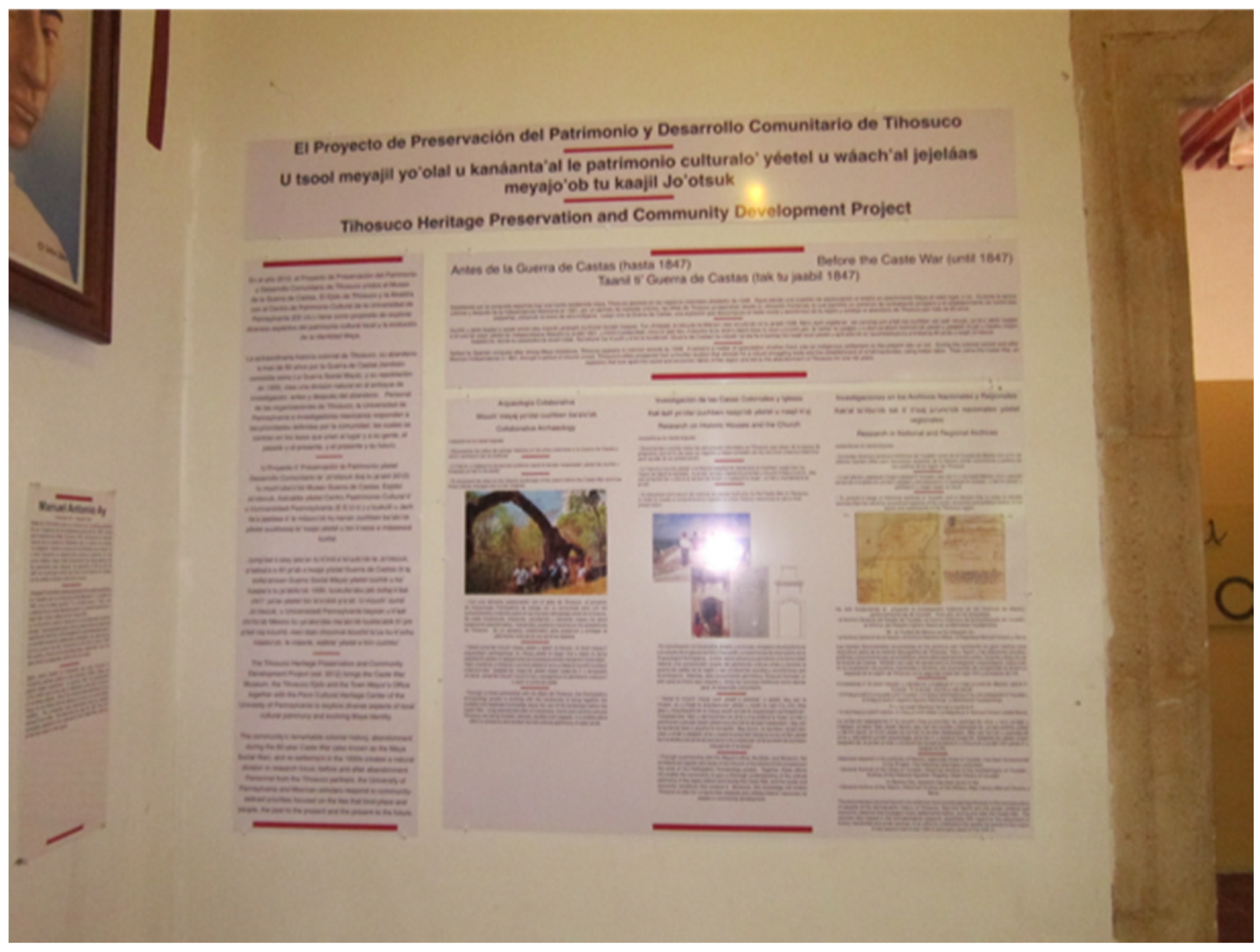

5. The Tihosuco Project: Overview

Today, an ongoing umbrella heritage project between affiliates of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center at the University of Pennsylvania and members of the Maya community of Tihosuco is working to create a kind of heritage engagement in the region that centers on people’s relationships with anti-colonial movements, such as the Caste War, while also promoting small-scale economic projects and future cultural development. This is a major shift in how archaeology is conducted because it acknowledges the importance of, not just stories about the past, but the impact of heritage upon the creation and existence of communities in the 21st century. In addition, it is a bottom-up model of heritage-based cultural and economic development. The project centers on building collaborative relationships over the long-term and eschews some of the continued academic emphasis on gathering data, creating publications, and interpreting the past as the primary aim of archaeological fieldwork.

The remainder of this article will provide an update on the progress of the Tihosuco Heritage Preservation and Community Development Project—hereafter the Tihosuco Project—since its inception in 2011 [

3]. It will provide an overview of the current work being done, with a focus on the process and outcomes, both positive and negative, that this work has engendered over the past nine years.

The project started as a collaborative effort to better understand the history of the Caste War and how it disrupted the social, economic, political, and physical landscape of the Yucatan peninsula for almost 60 years. While initially grounded in the archaeological study of the past, the project has always maintained a focus on present conditions and the needs of the community, with an eye to the future. It is grounded in a forward-looking present, which makes the most of anthropological archaeological practices.

The study of the Caste War remains one of the central aims of the overall project, with an archaeological sub-project that documents the historic vestiges of the era, including towns, haciendas, ranches, and road systems across the ejido of Tihosuco (cooperative land tenure organization common in Mexico). Branching out from the three initial project foci—Caste War Museum, Caste War era sites of XCulumpich (a hacienda), and Tela (Lal Kaj’; a town) on the ejido land, and general activities regarding engagement, education, and collaboration with the people in town—the project now has nine fully developed sub-projects. Based upon numerous community meetings and requests, these sub-projects include oral histories of the current community, the documentation of historic structures within the central core of the town, the preservation of old photographs, the revitalization of the Maya language, as well as broader tourism and development concerns. We will touch on a few of them here, speaking specifically to how the process has evolved over time, and the challenges we have faced in implementing our project goals.

This project is focused upon the community of Tihosuco, which is created by both a physical concentration of people but also through the shared emotions and expressions of the community that are constantly changing [

6]. As such, our research questions and methods are constantly evolving to meet the current needs and practices of anthropology. If we were to estimate, at least 25% of our time in the field is devoted to meetings and outreach within the town of Tihosuco, with another 25–50% consisting of constant conversations and exchanges of ideas even in the middle of work within the field. What this entails varies by sub-project, which we will discuss further in subsequent sections.

The premise of the project has not changed, however our approaches have evolved and adapted over time. Community development and preservation, both cultural and economic, have become long-term goals of the overall project, which is why they have been integrated into the name. It reflects our investigations and conversations about what is important to the community, and that certainly extends well beyond archaeological inquiry. A project with such breadth and depth is often chaotic and difficult to manage and maintain—but necessary ethically. The benefit of the past should surely not just be for those of us in the ivory tower of academia, nor those within the upper reaches of the socio-economic system. This type of work involves inverting the power relationships regarding the past, particularly with questions of ownership and control of access or narrative. Understanding the impact that this work has on the community and the people with which we work is paramount to how we frame our project [

23].

Unfortunately, much of the hierarchy of power over the past has not been changed, particularly with regard to who in Mexico controls access to archaeological sites and resources, but we are trying to change this with our model. The power structures in place continue to have hold over the ability for people in Tihosuco to truly benefit from the past, but by encouraging more bottom-up projects and control over resources, slow changes are being made in how control is communicated on the ground and who gets a seat at the table when decisions are being made. We continue to stake the community as the primary place where decisions about our work are done and where ideas for the future are developed [

3]. We endeavor each day to forge equitable stakes in the work—economically, socially, culturally, and educationally.

6. The Sub-Projects: Challenges and Logistics, Surprises and Setbacks

Overall, the primary steps in constructing this project have been about collaboration, deep engagement, and relationship building. Each graduate student or scholar who joins the project is there on a trial basis their first season. The community has to embrace them as a collaborator, and through extended conversations, a project is developed that will turn into a dissertation, thesis, or sub-project. This new program must be identified as having a demonstrated benefit for all parties involved. If it is not seen as interesting, feasible, or valuable by those that will be participating from Tihosuco, it does not move forward. Only then do we decide on more concrete research questions and set up a plan for work. The overall project has not been without its pitfalls; most notably, it is a slow-moving process for gaining approvals, buy-ins, and cooperation between the many groups. The leadership of the town, both the mayor and the head of the ejido, changes every three years, and with that change comes an entirely new administration and group of people, some of whom are familiar with our work, and some whom are not. Local politics and federal recognition of Tihosuco have also complicated matters, as the battle over who controls the narrative of the past is constantly negotiated.

For the sake of clarity, we have broken down our sub-projects by those that focus on the past, and those that are more present and future oriented. However, that is not to say that the archaeological component does not have impact in the present, or that the project to revitalize Maya language does not have roots in the past. Our model of work focuses on bridging these temporalities and demonstrating that true anthropological archaeology is never just about the past.

6.1. The Study of the Past

Anthropological archaeology, as defined above, necessarily focuses on the past, understanding how that past may still exist in the present, and uncovering stories and histories that may have been otherwise silenced in the historical record. The Caste War is no exception. Between its marginalization as both a successful but ultimately failed indigenous rebellion and the belief that, perhaps, it never truly ended, it occupies that liminal space bridging the past and the present.

6.1.1. Historical Archaeology

We are sitting in front of the casa ejidal (the administrative offices for the Tihosuco ejido) after a long day in the field. Large bottles of Coca-Cola and Fanta and packages of cookies are being passed around as we discuss the work that we have done during the week, and what the future looks like for Tihosuco. The discussion starts slowly, but some of the younger generation have started to chime in. “Patrimony is going to help us keep jobs here.” “We need to learn more about the past so we can tell it to the tourists when they come.” “This is an important story to share.” These quotes represent paraphrases of common themes that occur in our designated platica sobre patrimonio (a chat about patrimony), hours that we have with the entire team each week. This conversation can address anything related to heritage, but it often comes back to the use of these stories and sites for the future of Tihosuco. We have spoken of the UNESCO world heritage list, the ways to protect heritage, the development of tourism and what that might look like, the history of the Caste War, and many other related subjects. These talks are held in the museum with a tour of the galleries or, in a more informal setting, such as the front of the casa ejidal. These conversations are essential for understanding how residents of Tihosuco view the concept of patrimony at a larger scale, but also how they see it in relation to their daily lives as the place where they live. Many of the younger generation we work with have lived and worked in the coastal tourist industry. They have seen first-hand the benefits and pitfalls of tourism, and they would like to see what would happen if it was a bit closer to home. Perhaps the most important outcome of these meetings is the collective decisions made about how to move forward with the project, and opinions on the use of these sites in the future. Some weeks the conversation flows, other weeks it is a struggle to get participation, but we persist in having them, because it provides an opportunity to be clear about our goals for the project and get input on the goals of the community. It solidifies, for ourselves and for the community, that this project is as much about the social and economic benefit of the research to the community as it is about uncovering more information about the history of the rebellion.

The historical archaeology sub-project of the Tihosuco project seeks to understand the lived experiences of the war, while also understanding how that historical memory impacts people in the region today [

24]. On the data collection side of the project, since the first year of the documentation of Caste War sites, Tiffany C. Fryer and the team (headed by Co-PIs: Secundino Cahum Balam, Elias Chi Poot, Bartolome Poot Moo, and several others) have documented and mapped one large and two small town sites within the ejido that were likely abandoned during the war, an additional ten hacienda sites that contain a few large structures and houses, and over thirteen smaller ranch sites, usually identified by their water systems and wall systems for the management of livestock or crops [

25]. Additionally, a concerted effort has been made to document the road systems that go between these sites, as well as identifying roads that appear on old maps, such as the road to the bahía de Asunción to the south of Tihosuco, which was a well-known entry port for pirates and illicit goods as early as the 17th and 18th centuries [

26].

Some excavation was undertaken in 2017 at the site of Tela’ or Lal Kaj, the largest of the abandoned town sites on the ejido land. Five crew leaders from Tihosuco were integral in leading a rotating crew of ejido members in these excavations. Through collaboration and discussion, the Tihosuco team identified where to excavate, conducted the excavation work, wrote notes, and created detailed maps. Each week, the crew leaders were tasked with training and educating the new members of the team and explaining what had been found in their excavation unit to date (

Figure 3). The work took time because of weekly team rotation but was exciting and meaningful for all involved, as we uncovered the tangible remains of this local history. At first, the ejido members were hesitant about excavation, but they now ask when we will be doing it again.

There are still sites we have not visited or documented because their current ejido representative is uninterested in participating, or no one was available to take the team there during the planned work weeks. However, our constant presence in town and the years spent building relationships have served us well in opening up a few more spaces yearly. This is the true collaborative point of this project—that trust and relationships allow us, not only to get permission to see and conduct research at these sites, but to understand the desires of use and access by the local community.

6.1.2. Casas Coloniales or Pre-War Houses

El primer paso (the first step) is how the collaborators on the colonial house sub-project have come to see the project since its inception. The first step started in 2013 and 2014 with a concerted effort to document, through measured drawings, photographs, and oral histories, the numerous historic sites in the “urban” core of Tihosuco. This complements the documentation work being done on the sites that are outside the town center and fall under the purview of the archaeological sub-project. The division between the two is arbitrary and mostly relates to the necessity of managing large amounts of data, the difference in who has jurisdiction over modern space, and individual dissertation projects. The ultimate goal of this documentation is to understand the history of these houses and ancillary structures in relation to the formation of Tihosuco and its role in the Caste War. In addition, it provided a way to start a conservation about these buildings and about the past. The project came about as a request from within the town to better understand the breadth of historical material that exists within Tihosuco. This sub-project is focused upon a large group of buildings, mostly houses, within Tihosuco that were originally built in the 18th and 19th centuries (

Figure 4). These buildings, and the town, were abandoned during the Caste War and then reoccupied in the 1920s–1930s. These standing structures (often without roofs) were used as the houses for the first families reoccupying the town and remain a primary part of the modern day community.

Kasey (co-author) joined the project with a plan to conduct a systematic historic resource survey and to take oral histories of the houses following the reoccupation of Tihosuco in the 1930s in order to understand how the buildings have evolved and changed over time. This project simply could not have been done if there had not been extensive participation by the town’s committee on the colonial houses, formed by a previous mayor, and if there had not been a co-lead, Socorro Poot Dzib, who is from Tihosuco and is also female. This allowed Kasey and Socorro to enter the houses during the day when many men were out in the field [

27].

However, with increased attention being paid to the buildings and the history of the Caste War by politicians, the project quickly changed course. The initial report produced by Kasey and Socorro was used by a group of state representatives to request that Tihosuco be declared a zona histórica (historic zone) at the national level. This zone provides additional protection for historic structures, while bringing national attention to the history of the town. However, resources for the actual restoration of the structures, many of which are in various states of repair, have been slow to come. The facades of a select few houses close to the central plaza were repainted in 2018 with funds from the state of Quintana Roo, but that work has already begun to fail, and the interiors have not been touched.

Now, a large portion of the study involves waiting for information from government officials, understanding where resources for restoration might come from, putting together reports and information that might help people in Tihosuco request those resources, and more generally being an advocate for the people of Tihosuco when government officials tend to want to bring in blanket programs that do little in terms of real benefit to the town. This wait-and-see model is both frustrating and rewarding—frustrating in that resources or restoration programs are slow to come, and when they do, are inadequate or poorly executed, and rewarding in that we have built strong relationships with the local Tihosuco government and committees, which have allowed us to generate new ideas for how to move forward. It has become a project focused on politicking as much as a study of the past. In some ways, we are able to watch and examine how the heritage story of the Caste War is being created, manipulated, and solidified into a more national narrative, and to explore who really benefits from this increased attention.

The hope for the future of this project is that the updated reports produced by Socorro and Kasey, highlighting the real conditions of the structures, can be used by the local authorities to request funding and projects that will make the buildings more functional as dwellings. The report focuses on the real needs of the buildings and goes beyond requesting façade repair. The connections built with INAH and local politicians also build a stronger platform for these requests, and people in town have made it clear that they want a seat at the table when discussing the future of their town and the uses of the heritage assets that exist within it.

6.2. Implications in the Present and Future: Modern Community Needs

What has become evident in our work over the past decade is that, while the legacy of the Caste War is important, there are other pasts and histories that the people of Tihosuco value equally. During the rebellion, the town was abandoned and remained largely unoccupied until the 1930s when it was resettled by people coming in from other areas of the peninsula seeking land and opportunities to create new communities [

28]. The histories of the repoblación (repopulation) come up in most conversations, with families tracing their histories back to a few intrepid men and women who came from the north and settled where they found available land. Many of these stories tie to the vestiges of built heritage we discuss above, because finding land with useable infrastructure enabled new settlements to form faster by employing these remains for temporary shelter. Documenting and exploring this newer chapter in Tihosuco has been the focus of a lot of oral history and photographic work as a complement to the archaeological work.

6.2.1. Photographs, Oral Histories, and Publications

The Caste War lies just beyond the lived experiences of the oldest generation in Tihosuco. When we began the oral history sub-project, we asked the town elders to recount what their grandparents and great grandparents might have told them about the war and the movements of people throughout the landscape of the peninsula. We were also looking for old photographs that might provide information about the architecture that remained on the landscape, and what the town looked like in the past. We have built up a large database of photographs, with the earliest probably dating to the 1950s, and recorded oral histories about the repopulation of the town and life in Tihosuco up to the present. We scan the photographs and return them to their owners, often with printed and digital copies that have been slightly retouched and repaired (a hot and humid climate is unkind to paper photographs).

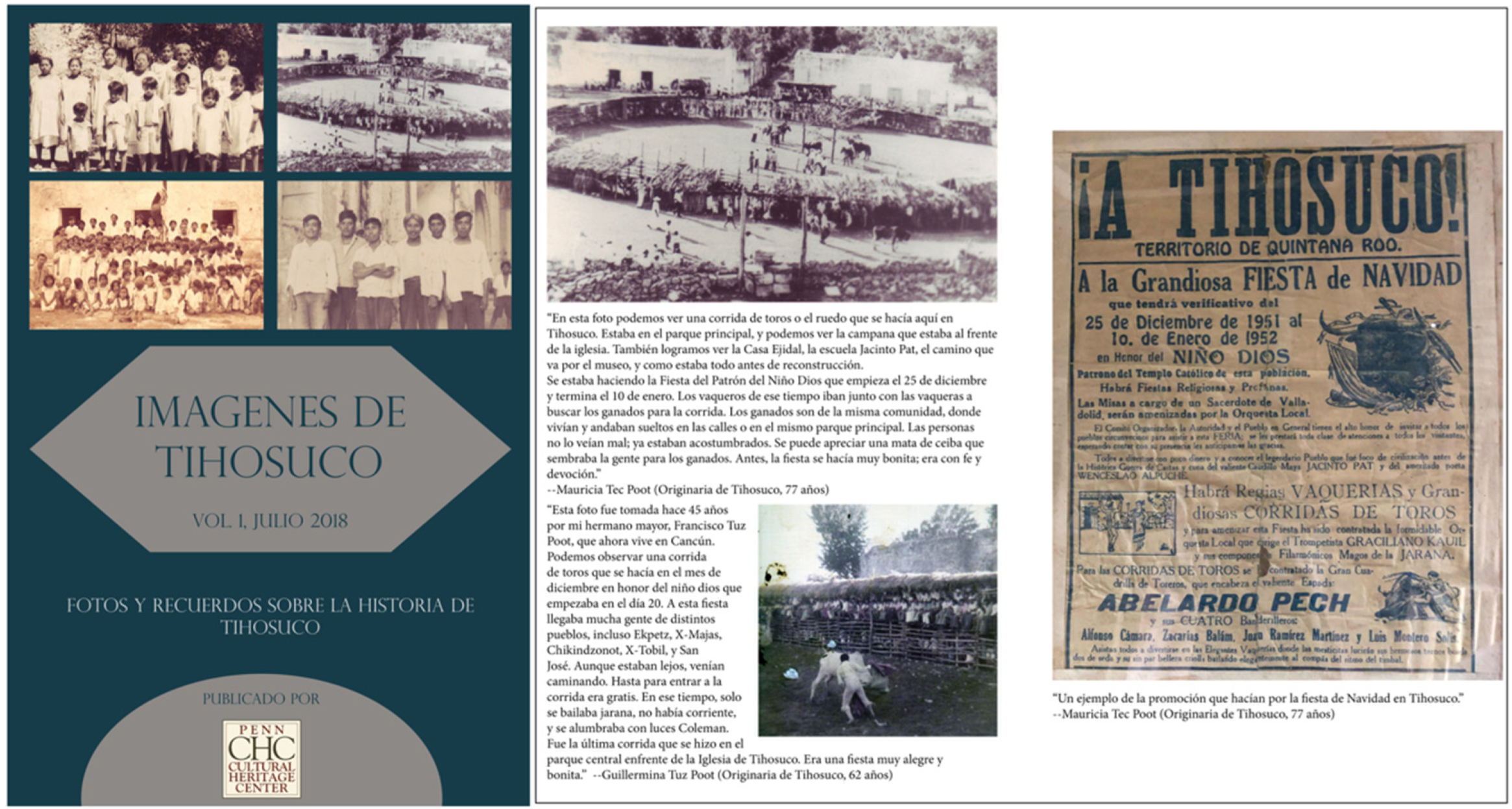

We were sitting and catching up one afternoon with Marcelina Chan Canche, a resident of Tihosuco and member of the project since 2013. She has been working with us to collect old photographs and conduct oral histories from people in Tihosuco. We were discussing who she was going to interview and what she thought about her work on the project. She stressed that we needed to do something with this material, not just collect them and give digital or hard copies of the photos back to the families. What we were missing, she said, was a concrete way to show the product of this work, and to provide something the community could react to and share. Marcelina suggested that we pull together some of the photographs and their corresponding histories and create thematic volumes for publication and local distribution (

Figure 5).

Thus, Imágenes de Tihosuco was born. The first volume (2018) focused on some of the oldest images we had, including scenes of local festivals and portraits of some of the repobladores. The second volume (2019) focused on the lineages of those people, tracing certain branches of their family trees into the present. The response to these volumes has been tremendously positive, with many requests for inclusion in future issues. These photographs do not represent the deep past, or even the past of the Caste War, but they do represent how Tihosuqueños think about their immediate past and highlight what they see as critical in telling their story to a broader public.

6.2.2. Maya Language Revitalization

“If you are going to do a true heritage project here in town, you need to do something about the Maya language.” Early on in the project, Carlos Chan Espinosa, then director of the Caste War Museum in Tihosuco, was adamant that any project talking about Maya heritage needed to have a language component. This sentiment was shared by many members of the older generation in Tihosuco, for there is a fear that the Yukatek Maya language is being lost, particularly among the younger generations—it was not being taught in schools, and it was a struggle to speak it with their children and grandchildren, who appeared embarrassed to use it. A particularly effective tool developed for this has been a series of historietas (historical comic books) describing, in comic book form, the lives of three of the leaders of the Caste War. Written in collaboration by members of the museums’ staff, especially Beatriz Poot Chable and Antonia Poot Tuz, along with Aldo Anzures Tapia (Penn), the stories of Jacinto Pat, Manuel Antonio Ay, and Cecilio Chi appear in both Maya and Spanish (

Figure 6). With Spanish on one side of the fold and Maya on the other, children and other interested readers can use the comics as both a teaching tool for Maya and a way to learn about the history of the rebellion. This comic book form proved very popular and has helped provide a tool for language instruction within the Caste War Museum, schools, and homes. They are also a tool for broader outreach about our project, and the aims of a more localized heritage program that goes beyond traditional archaeology.

6.2.3. Museum Work

There is a room at the Caste War Museum in Tihosuco that is littered with local artifacts. Some are ancient Maya pottery, some are firearms and ammunition, and some are tools from chicle harvesters. Further still, there are record players, CD players, old adding machines, and glass bottles. This room is used by the residents of Tihosuco as a repository for things that show the history of their community. Residents of Tihosuco know what a museum is and what it can be, and when the rigid structure of the other galleries in the museum did not reflect that, or the history they thought should be displayed, they worked around the official government structure of the museum and created a separate gallery (

Figure 7). With input from our project, and the creation of signage, the community room now has information about heritage and patrimony, profiles of the leaders of the Caste War, signs about our project and the sub-projects, in addition to a now curated and labeled display of those artifacts that have been donated by community members—all with signs now in three languages (Maya, Spanish, and English). The room, with its artifacts and signs, is a perfect demonstration of the fluidity with which Tihosuqueños view heritage, and what stories and objects are important to them from both the distant and recent pasts.

As one of the primary partners of the project, the museum, which is located in the center of town, has proved a fruitful place from which to initiate our community outreach and to connect the story of the rebellion to the artifacts and archaeological survey we are doing on ejido land. One of the benefits of this partnership was that we were able to begin the project with an already established institution, which helped us disseminate information about the goals of the project and the nature of our work. Officially, the museum is under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of Culture for the state of Quintana Roo, but it is managed and staffed by people who live in Tihosuco. The museum has become a community center within the town. The presence of a museum in town has also made logistics easier for the project: the museum has been identified as the official repository for any artifacts found during the project. Eventually, we hope to display these materials more permanently in the museum. We have also received permission from INAH to exhibit the artifacts during the anniversary celebration of the rebellion each July, which helps broaden the visibility of our work in town.

6.2.4. Exhibits and Public Outreach

Every year during the anniversary celebration of the rebellion in July, we put on a large exhibition of photographs of our work, printed on massive banners and displayed on the facades of buildings throughout the town center. We create an outdoor museum of sorts, showcasing work from each of the sub-projects (

Figure 8). During the events of the anniversary, people wander through the town center, looking at the photographs of their friends and relatives who have been on our weekly teams, seeing old pictures of family, and looking at copies of letters written by the leaders of the Caste War. These exhibits are a focal point in our effort to disseminate our research to the larger Tihosuco community and beyond.

In addition, people from Tihosuco are part of the presentation team when academic papers are given at international conferences held in Mexico, such as the Third International Conference of the Society for American Archaeology, held in Oaxaca in 2017, and the Eleventh International Congress of Mayistas that was held in 2019 in Chetumal, Mexico. Our collaborators, therefore, are full partners within this project, not just with excavating or clearing settlements in the jungle, but also in the interpretation and presentation of ideas within academic settings.

This is an area where we most struggle with groups outside Tihosuco. Our exhibitions and public speeches often conflict with or overshadow the political desires of those seeking to benefit from the use of the Caste War narrative in their campaigns for election or job advancement. One year, we had to remove our exhibit from the main plaza in Tihosuco because it conflicted with an external exhibition of photographs that a local politician brought to Tihosuco, even though the photographs had little connection to the community. That was a struggle for our entire team, especially those from Tihosuco, because it was understood that the community exhibition reflected the activities within Tihosuco and was important to the people in town. In the end, after much discussion with the local authorities and the people of Tihosuco, we agreed to remove the community exhibit to a less public place in order to not directly conflict with political authorities from outside the town.

6.2.5. Tourism

Finally, being so close to Cancun and the Maya Riviera, residents of Tihosuco have seen the benefits and pitfalls of tourism. As a struggling farming community, they see tourism as a potential industry that could bring jobs and stability to their lives. However, there is great anxiety about tourism, which is seen as a powerful outside force that can change and control a small community, such as Tihosuco. Today, many of the young people of Tihosuco leave after high school or university in search of work along the coast, upsetting the town and family dynamics.

Our Tihosuco project is focused on both community and economic development. Part of our project is to work with local authorities and community members to create a small-scale and locally led tourism industry, focused on the history of the Caste War. The primary focus of this program is to attempt to bring some internal economic stability to the community while, at the same time, ensure that the story of the Caste War rebellion that is told to tourists is that of the people of Tihosuco, not one structured and controlled by the state and federal governments.

7. Conclusions

As we have demonstrated, creating a collaborative anthropological archaeology and heritage project requires us to frequently deal with issues of control and ownership over the heritage of the recent past and the present. A primary goal of the Tihosuco project is to broaden the definition of heritage and create a more inclusive picture of, not only the past, but how that past is employed, protected, and disseminated over time. We use this approach to better help us understand the dynamic between temporalities, as well as make sure that our study is not simply interesting research but, in fact, useful for the community within which we, as outsiders, live and work. The past needs to relate to the present and the future. This approach for anthropological archaeology foregrounds the very pressing issues of social and economic inequality that directly impact marginalized communities that live in association with historic and archaeological sites.

Our approach also changes how we define heritage practice and its link to anthropological archaeology. Sites that we, as archaeologists, assume to be part of a community’s heritage may not necessarily matter to people as we would expect. To prioritize only those pasts that fit neatly within our own research interests and programs is an injustice to our collaborators, the field, and the study of the past in the present. Instead, our objective should be to engage with the sites and stories that are important for communities today. That understanding can only be determined through deep collaboration and conversation and the ability to open up the past for new views of heritage and interpretations of the past. To write off those pieces of heritage that do not meet specific research aims or questions is to do a gross injustice to our collaborators, the field, and the study of the past in the present.

Author Contributions

This article was written jointly by both authors and they accept all responsibility for its content and limitations. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Penn Cultural Heritage Center, Penn School of Arts and Sciences, The Penn Museum, The Department of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, the National Science Foundation # 1640392, the Penn Latin American and Latino Studies Program, and the Louis J. Kolb Society of Fellows: Greenewalt Funds.

Acknowledgments

We are exceedingly grateful to all the collaborators we have mentioned in the text of this article, as well as the rest of the Tihosuco community, particularly those who work in the Museo de la Guerra de Castas, the ejido of Tihozuco, and the Alcaldia of Tihosuco. We appreciate the support of INAH for our work, and continued permissions for it. We thank Julian Siggers, Director of the Penn museum, for his belief in this project, and Brian I. Daniels and Gracie Golden of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center, for their countless hours of administrative work and moral support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharer, R.J.; Traxler, L.P. The Ancient Maya, 6th ed.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780804748162. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, N. The Caste War of Yucatan; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, R.M.; Espinosa, C.C.; Pat, E.M.; Cahun, D.P. The Community Heritage Project in Tihosuco, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Public Archaeol. 2014, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, C. The Pursuit of Ruins: Archaeology, History, and the Making of Modern Mexico; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2016; ISBN 9780826357335. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, Q.E. In the Museum of Maya Culture: Touring Chichén Itzá; 2. print; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996; ISBN 9780816626724. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W. A Study of Archeology; Memoir 69; American Anthropological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Willey, G.R.; Phillips, P. Method and Theory in American Archaeology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Binford, L.R. Archaeology as Anthropology. Am. Antiq. 1962, 28, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigger, B.G. A History of Archaeological Thought; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, T.C. Reflecting on Positionality: Archaeological Heritage Praxis in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Archaeol. Pap. Am. Anthropol. Assoc. 2020, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Willey, G.R.; Sabloff, J.A. A History of American Archaeology; W.H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780716723707. [Google Scholar]

- Hodder, I. The Archaeological Process: An Introduction; Repr.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1999; ISBN 9780631198857. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, H.; Waterton, E.; Watson, S. Heritage in Action: Making the Past in the Present; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 1997; ISBN 978-3-319-42868-0. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Archaeological Theory and the Politics of Cultural Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 1134367961. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C.J. Heritage or Heresy: Archaeology and Culture on the Maya Riviera; University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780817316358. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.D.; Kautz, R. The Transition to Statehood in the New World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981; ISBN 9780521240758. [Google Scholar]

- Diserens Morgan, K.; Fryer, T.C. Coloniality in the Maya Lowlands: Archaeological Perspectives; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, E.Z. Fieldwork among the Maya: Reflections on the Harvard Chiapas Project, 1st ed.; University of New Mexico Press: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 1994; ISBN 082631502X. [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, E.Z. Tortillas for the Gods: A Symbolic Analysis of Zinacanteco Rituals; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1993; ISBN 9780806125596. [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, M.B. A Return to Servitude: Maya Migration and the Tourist Trade in Cancún; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010; ISBN 9780816656158. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbert, W. Violence and the Caste War of Yucatán; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 9781108491747. [Google Scholar]

- Dumond, D.E. The Machete and the Cross: Campesino Rebellion in Yucatan; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, UK, 1997; ISBN 0803217064. [Google Scholar]

- Ardren, T. Conversations about the production of archaeological knowledge and community museums at Chunchucmil and Kochol, Yucatán, México. World Archaeol. 2002, 34, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cain, T.C. Materializing Political Violence: Segregation, War, and Memory in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, T.C. Confronting Violence in the Layered Landscapes of East-Central Quintana Roo. In Coloniality in the Maya Lowlands: Archaeological Perspectives; Diserens Morgan, K., Fryer, T.C., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2020; pp. 153–182, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Olan de la Cruz, F.A.; Garcia Lara, F.D. Piracy and Smuggling on the Eastern Colonial Frontier of the Yucatan Peninsula during the 18th Century. In Coloniality in the Maya Lowlands: Archaeological Perspectives; Diserens Morgan, K., Fryer, T.C., Eds.; University Press of Colorado: Denver, CO, USA, 2020; pp. 114–145, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Fryer, T.C.; Diserens Morgan, K. Heritage Activism in Quintana Roo, Mexico: Assembling New Futures through an Umbrella Heritage Practice. In Trowels in the Trenches: Archaeology as Social Activism; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, G.D. Anthropology and History in Yucatán; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1977; ISBN 9780292703148. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).