1. Introduction

The understanding of heritage conservation has evolved over the past two decades from “management of change,” as articulated in the Charter of Krakow, to “management of continuity” [

1] (p. 254) or “management of continuity and change” [

2] (p. 2), [

3] (p. 30) then, more recently, to “management of continuity and compatible change” in scholarly literature [

4] (endnote 4), [

5] (p. 243). The underlying idea is not only to sustain the significance of heritage places, but also to accommodate and harmoniously integrate contemporary interventions that have no or minimal adverse impact on the attributes of significance. Attributes are aspects of a heritage place that convey values. They can be tangible or intangible such as materials, form, design, setting, function, techniques, and traditions. This article takes this idea a step further by exploring the nexus between continuity, compatibility (compatible change), and integrity in the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. This property-based Convention was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO on 16 November 1972 [

6]. It remains the most important international legal instrument and disseminator of discourses, policies, and practices in the heritage field. It is ratified worldwide by 193 States Parties that can nominate properties for inscription on the World Heritage List [

6] (Article 11).

The World Heritage Committee, composed of representatives from 21 States Parties, is the main decision-making body in charge of the implementation of this Convention, assisted by its Advisory Bodies, namely the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The Operational Guidelines for the implementation of this Convention describe the requirements that must be met in order for properties to obtain and maintain international recognition—from nomination, through inscription on the World Heritage List, to post-inscription. “Integrity” is not mentioned in the text of the Convention. It became a requirement for the nomination of natural properties in 1977 [

7]. From 2005 onwards, it also became a requirement for the nomination of cultural properties [

8]. Yet, its application remains unclear as presently worded in the Operational Guidelines [

9] (Paragraph 88). The discussion about “integrity for cultural heritage” in particular is not over [

10,

11]. There are many unresolved issues that need to be addressed. For instance, “examples of the application of the conditions of integrity” to cultural properties have been “under development”’ since 2005 [

8] (Note next to Paragraph 89). ICOMOS has not yet developed statements on integrity for each cultural criterion equivalent to those developed by IUCN for each natural criterion [

9] (Paragraphs 89–95, see also Paragraph 77 for the list of criteria). Lack of “certainty, clarity, and consistency” in the treatment of cultural and natural heritage creates a problem for an international “system of collective protection” that claims to uphold the principles of credibility, effectiveness, and scientific excellence enshrined in the Convention [

12] (p. 17), [

6] (Preamble, Paragraph 8).

This article proposes an alternative conceptual and operational framework for nomination, evaluation, protection and management to strengthen the requirement of integrity and, therefore, to improve certainty, clarity, and consistency in the implementation of the Convention. More specifically, it gradually explains why continuity and compatibility should become qualifying conditions of integrity in the Operational Guidelines. In doing so, it makes many significant contributions not only to the body of knowledge and literature on World Heritage, but also to World Heritage policy formulation. It shows how to bridge the culture/nature divide, keep properties in a good state of conservation, sustain their cultural-natural significance including Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), and enable sustainable development. Sustainable development has become a central aspiration, especially since 2015 when the General Assembly of States Parties adopted a policy document [

13] that builds on Articles 4 and 5 of the Convention [

6] and Goal 3 of the Strategic Action Plan 2012–2022 [

14].

It is noteworthy that the Operational Guidelines can be revised and have been revised almost thirty times between 1977 and 2019 to reflect new concepts, knowledge and experiences. Therefore, the World Heritage Committee can adopt and operationalize the concepts recommended in this article, namely continuity and compatibility. Their inclusion in the Operational Guidelines can not only strengthen the requirement of integrity, but can also help the World Heritage Leadership Programme achieve its aim, which is “to improve conservation and management practices for culture and nature” [

15] (online). Their inclusion can also facilitate the application of the Historic Urban Landscape Approach and its tools [

16], especially to harmonize the implementation of the Convention with that of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

17]. This article, therefore, will be of interest to a broad readership and will stimulate discussion about the practical application of the proposed conceptual and operational framework to existing World Heritage properties and management plans, as well as to future nominations.

3. Integrity

An informal consultation meeting on the implementation of the World Heritage Convention was convened in Morges, Switzerland, in 1976, to allow an exchange of views about the criteria for the inclusion of properties in the World Heritage List, the format and content of documentation to be requested from States Parties, and the criteria for the determination of an order of priorities for awarding international assistance [

18] (p. 1). ICOMOS, IUCN, and ICCROM had already prepared recommendations in advance. Interestingly, they did not mention the notion of authenticity. ICOMOS recommended “unity and integrity of quality (deriving from setting, function, design, materials, workmanship and condition)” for the nomination of cultural properties [

18] (Annex III). IUCN also recommended integrity for the nomination of natural properties [

18] (Annex IV).

During the discussion, the participants considered integrity “of particular importance for all natural properties and for those cultural properties that were to be judged according to the criteria of artistic value, associative value and typicality” and “strongly recommended that the World Heritage Committee should have the right to remove property from the WHL that had been destroyed or suffered a loss of integrity” [

18] (p. 2, see also pp. 5, 22). It must be observed that the notion of “integrity” is not mentioned in the text of the Convention, but the idea of loss of integrity is obvious. The Convention aims at protecting both cultural and natural heritage of Outstanding Universal Value from “destruction,” “decay,” “damage,” “deterioration,” “disappearance,” “major alterations,” and “changes” among other dangers [

6] (Preamble, Article 11.4). Concern over loss of integrity is also clear in the Recommendation adopted on the same day as the Convention, through the words “disappearance,” “not to impair the intrinsic character,” “deterioration,” “impair,” “damage,” “drastically alter,” “derelict,” “despoiled,” “affect its appearance,” “destroys, mutilates or defaces” [

19] (Preamble, Items 15, 19, 23, 25, 27, 28, 36, 39, 42, 47). The Venice Charter, i.e., the foundational doctrinal text of ICOMOS, also accords great importance to the protection of integrity, noting that “Replacements of missing parts must integrate harmoniously with the whole,” “The material used for integration should always be recognizable,” and “there should always be precise documentation” of “Every stage of the work of [...] integration [...]” [

20] (Articles 12, 15, 16).

In preparation for the Morges meeting, ICOMOS had also “recommended that a nomination form similar to that used by the U.S. National Register of Historic Places serve as the basis for the documentary reports” of cultural properties nominated for inscription on the World Heritage List [

18] (Annex III). This shows that ICOMOS was inspired by the American approach. It is also noteworthy that the U.S. National Register Criteria for Evaluation links attributes to integrity (not authenticity): “The quality of significance [...] is present in districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects that possess integrity of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, feeling, and association” [

21] (p. 2). ICOMOS Secretary-General Ernest Allen Connally, who spoke on behalf of ICOMOS at the Morges meeting (with Ann Webster-Smith), brought the American approach “to the World Heritage table,” which “was readily accepted [...] as an important consideration” [

22] (p. 23).

However, shortly thereafter, an ICOMOS pioneer, namely Raymond Lemaire, who was not present at the Morges meeting, “proposed changing

integrity to

authenticity out of concern that the rule might seem to restrict eligibility of monuments to those with purity of original design or form,” which explains why “American

integrity became World Heritage

authenticity” [

23] (p. 12), see also [

24] (p. 7). The World Heritage Committee approved this change of vocabulary despite the fact that authenticity is neither defined, nor mentioned, nor obviously implied (as is the case for loss of integrity) in the text of the Convention [

6]. ICOMOS’ initial recommendation was also amended by removing “function” and “condition” [

18] (Annex III). The other attributes found their way into the Operational Guidelines for the implementation of the Convention. This explains why cultural properties had to “meet the test of authenticity in design, materials, workmanship and setting” whereas natural properties had to “meet the conditions of integrity” to be considered for inclusion in the World Heritage List [

7] (Paragraphs 9, 11). This decision divided the treatment of cultural and natural heritage under the Convention. It reinforced the culture/nature divide created by the two separate definitions of cultural and natural heritage in the text of the Convention [

6] (Articles 1, 2) and the two separate sets of criteria for cultural and natural properties in the Operational Guidelines [

7] (Paragraph 5(iii)). This divide continues to pose “policy and institutional challenges” and to present “States Parties and heritage practitioners with implementation complexities in their everyday work” even after the criteria for cultural and natural properties were unified in 2005 [

25] (p. 1), [

8] (Paragraph 77). The lack of a precise linguistic equivalent to authenticity in many languages and the lack of a clear definition in the Operational Guidelines also pose a problem for its application to nominations of cultural properties. States Parties have not understood authenticity “in completely consistent fashion” for “over 30 years of nominations” [

22] (p. 30).

Integrity, in relation to cultural properties, found its way into the Operational Guidelines nonetheless. It appeared for the first time in the 1983 version: “the factor or factors which are threatening the integrity of the property must be those which are amenable to correction by human action. In the case of cultural properties, both natural factors and man-made factors may be threatening” [

26] (Paragraph 50). This sentence establishes a link between the integrity and the state of conservation of a property. The role of management was later articulated in the 1988 version: “in order to preserve the integrity of cultural sites, particularly those open to large numbers of visitors, the State Party concerned should be able to provide evidence of suitable administrative arrangements to cover the management of the property” [

27] (Paragraph 24(b)(ii)).

Concern over the culture/nature divide continued to grow despite these revisions. During the expert meeting on Evaluation of General Principles and Criteria for Nominations of Natural World Heritage Sites, convened in Parc National de la Vanoise, France, in 1996, the participants noted the existence of “separate conditions of authenticity defined as ‘test of authenticity’ [...] for cultural heritage and ‘conditions of integrity’ [....] for natural heritage” in the Operational Guidelines, and suggested reviewing these two notions to “develop one common approach to integrity”, which, it was argued, “would lead to a more coherent interpretation of the Convention and its unique strength in bringing the protection of both nature and culture together” [

28] (p. 4). They also recalled the need “to establish the basis for an holistic, integrated global strategy, which represents the continuum of culture and nature in conformity with the Convention” [

28] (p. 12). These ideas were revisited during the expert meeting on the World Heritage Global Strategy for Natural and Cultural Heritage in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, in 1998. The participants discussed “the application of the ‘conditions of integrity’ versus the ‘test of authenticity’” among other topics, such as the unification of the two separate sets of criteria for cultural and natural properties [

29] (p. 1). Bing Lucas, speaking on behalf of IUCN, argued in favor of “a common approach to integrity to apply to all sites” adding that it is important “to ensure the continuing integrity of World Heritage sites” whether cultural or natural [

29] (p. 3). Intentionally or not, his statement explicitly linked continuity to integrity, but not a single participant picked up the concept of continuity. Carmen Anon, speaking on behalf of ICOMOS, “agreed with IUCN that the ‘test of authenticity’ could be replaced by ‘conditions of integrity’” [

29] (p. 3). However, it appears that some participants believed “the test of authenticity should not be deleted entirely as it has importance for certain cultures and types of cultural heritage”, which, counterproductively, are not specified in the report of the meeting [

29] (p. 12). This vagueness may explain why the test of authenticity was kept for all cultural properties in later versions of the Operational Guidelines.

The participants also recommended combining the two sets of criteria for cultural and natural properties into one list of ten criteria, but this recommendation did not materialize until 2005, which is the same year when nominations of cultural properties had to satisfy the “conditions of integrity” in addition to the “conditions of authenticity,” formerly known as the “test of authenticity,” in the Operational Guidelines [

8] (Paragraphs 77, 79, 87). A definition of integrity was finally provided. This definition remained unchanged in subsequent versions, including the latest one, issued in 2019:

Integrity is a measure of the wholeness and intactness of the natural and/or cultural heritage and its attributes. Examining the conditions of integrity, therefore requires assessing the extent to which the property:

- (a)

includes all elements necessary to express its Outstanding Universal Value;

- (b)

is of adequate size to ensure the complete representation of the features and processes which convey the property’s significance;

- (c)

suffers from adverse effects of development and/or neglect.

This should be presented in a statement of integrity.

The original state of a property is not mentioned in this definition, which implies that changes made over the years or recently do not necessarily disqualify a property from being accepted for inclusion in the World Heritage List. What is clear is that “Integrity must necessarily be related to the qualities that are valued in a particular property” [

30] (p. 12). These qualities are “attributes” or “features.” According to the World Heritage resource manual that explains how to prepare nominations, “it is more common to speak of ‘features’” for natural properties, which could include visual or aesthetic significance, scale of the extent of physical features or natural habitats, intactness of physical or ecological processes, naturalness and intactness of natural systems, viability of populations of rare species, and rarity [

31] (p. 32), see also [

9] (Paragraphs 92-95). For cultural properties, attributes could include form, design, materials, substance, use, function, traditions, techniques, management systems, location, setting, language, other forms of intangible heritage, spirit and feeling, which are listed under “conditions of authenticity” in the Operational Guidelines [

31] (p. 61), [

9] (Paragraph 82). These attributes are derived from the 1994 Nara Document on Authenticity [

32] (Article 13) and the recommendations of the expert meeting on authenticity and integrity in an African context held in Great Zimbabwe in 2000 as explained in the Operational Guidelines [

9] (Annex 4). Attributes/features must be identified to determine the boundaries of a property and to justify its inscription on the World Heritage List (in line with the selected criteria). They must continue to be the focus of protection and management post-inscription [

31] (pp. 32, 59). The resource manual further explains, with regard to integrity:

The key words are “wholeness”, “intactness” and “absence of threats”. These can be understood as follows:

Another World Heritage resource manual, dedicated to management, provides slightly different key words:

boundaries—does the property contain all the attributes to sustain the property’s Outstanding Universal Value?

completeness—is the property of adequate size to ensure the complete presentation of the processes and features that convey its significance?

state of conservation—are the attributes conveying Outstanding Universal Value at risk from neglect or decay? [

33] (p. 37), see also [

34] (p. 21).

One cannot help but notice the relevance of the concept of

continuity in maintaining wholeness—i.e., the attributes continue to be within the boundaries of the property; maintaining intactness—i.e., the attributes continue to be intact and completely present; and preventing decay/deterioration/neglect over time—i.e., the state of conservation continues to be monitored. “Monitoring,” it must be noted, is “seen as a benchmark statement of integrity” and is important for the continuing protection and management of properties, especially attributes, to sustain OUV [

29] (p. 16), [

9] (Paragraphs 96, 111(c)(d), 130.6, 132.6). Despite its great practical utility, the concept of continuity is overlooked in the Operational Guidelines.

Continuity, however, cannot alone prevent “adverse effects of development” [

9] (Paragraph 88(c)), which are threats to OUV. According to a statistical analysis, “buildings and development” were the second most reported category of threats after “management and institutional factors” in state of conservation reports between 1979 and 2013 [

35] (p. 22). Projects that may cause, or have caused, problems include reconstruction projects, new construction projects such as high-rise buildings, bridges, changes to land use and urban planning policies, roads or road networks, large dams, large-scale commercial agriculture developments, landscape-scale mining, and energy projects such as wind-farms [

36,

37,

38,

39]. How to assess the impact of development projects in and around World Heritage properties, especially in cities, is still under discussion [

40]. Nonetheless, the Operational Guidelines request States Parties to inform the World Heritage Committee “of their intention to undertake or to authorize” development projects including “major restorations or new constructions” in or around World Heritage properties, and to carry out impact assessments before taking any decision “so that the Committee may assist in seeking appropriate solutions to ensure that the Outstanding Universal Value of the property is fully preserved” [

9] (Paragraphs 110, 172, 118bis). Appropriate solutions imply that development projects and interventions—i.e., change—“must integrate harmoniously with the whole” as per the Venice Charter [

2] (Article 12) and have no or minimal adverse impact on the attributes of significance as per the Burra Charter [

41] (Article 1.11). In other words, change must be compatible. Compatibility can prevent “adverse effects of development” while continuity can prevent “adverse effects of neglect” through ongoing maintenance and monitoring [

9] (Paragraph 88(c)). Together, they can keep World Heritage properties in a good state of conservation. Compatibility, however, is not even mentioned in the Operational Guidelines. It briefly appears in the World Heritage resource manual on the management of cultural properties, which explains that management should permit “continuing compatible land uses or economic activity,” promote “compatible local development” that “contributes to the sustainability of the heritage,” and “ensure that interventions are thoughtfully designed” and “are compatible with protecting OUV” [

33] (pp. 23, 101, 125). It also briefly appears in the World Heritage resource manual on the management of natural properties [

34] (pp. 17, 29, 60).

Two international World Heritage expert meetings are worth mentioning here to further show the relevance of continuity and compatibility to the strengthening of the requirement of integrity. The first meeting took place in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates, in 2012, to contribute to a better understanding of the notion of integrity and to develop examples of its application to cultural properties [

10]. However, the examples developed by the participants were not included in the Operational Guidelines [

11] (pp. 4, 5). This section of the Operational Guidelines is still in progress [

9] (Note next to Paragraph 89). The participants also “considered that the management of change has to be taken into account” and that “integrity” may “be understood as the ability of the property to secure and sustain its significance over time”—a definition proposed by Herb Stovel [

11] (p. 3), [

22] (p. 21). One may argue that “sustain” and “over time” echo continuity. This observation suggests that the management of continuity should also be taken into account. The second meeting took place in Agra, India, in 2013, to review the question of visual integrity whilst discussing cases of adverse effects of development, such as high-rise buildings and bridges [

38]. The participants recommended that nomination files should include “Measures to ensure that future developments will be compatible with the conservation of attributes and relationships supporting the property’s OUV” and suggested “impact assessments” [

39] (p. 3), which are tools that can help determine compatibility. The following section examines these two concepts in more detail to establish their relation to integrity, protection and management requirements, and sustainable development.

4. Continuity and Compatibility

Continuity has the advantage of being an easy concept to understand—simply allow for something to last over time. It is a fundamental concept nonetheless. The Convention explains that it is the responsibility of States Parties “to continue to protect, conserve and present” (manage) the properties situated on their territories [

6] (Article 26). Properties must continue to convey OUV to remain on the World Heritage List. The Convention, however, does not define OUV. This concept remained “too vague” [

42] (p. 232) until a definition was included in the 2005 version of the Operational Guidelines [

8] and additional clarification was published [

43]. Its definition is worth repeating here to make a point: OUV “means cultural and/or natural significance which is so exceptional as to transcend national boundaries and to be of common importance for present and future generations of all humanity” [

9] (Paragraph 49). First, this definition implies that OUV is a value added to the national (and sub-national) “significance” of a property. Yet, only the provision of a Statement of OUV is compulsory for nomination, evaluation, protection and management in the Operational Guidelines. The provision of a comprehensive Statement of Significance is not a mandatory requirement as though the values ascribed to a property, other than OUV, are not essential. Second, and most importantly for the purpose of this article, “present and future” imply that OUV should continue over time; yet, the concept of continuity has not been operationalized.

The practical utility of this concept in the implementation of the Convention was explored in scholarly literature nonetheless. A study suggested continuity as a sub-aspect of authenticity/integrity, but only in relation to the attributes of function and setting [

22] (pp. 32-34). Continuity was also suggested as a third qualifying condition, in addition to authenticity and integrity, but only in relation to historic cities given that a well-managed historic city should “maintain and strengthen its sources of continuity” such as “continuity of form, layout, living traditions, and patterns of use” [

44] (pp. 114, 115). More recently, a different study explained why continuity should replace authenticity altogether, arguing that this replacement can bridge the culture/nature divide, facilitate the application of people-centred approaches to conservation, enhance the role of communities [

4] and strengthen synergies between the World Heritage Convention and the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage “in which the notion of authenticity was deliberately ousted from the entire text whereas the notion of continuity was explicitly included in the definition of intangible cultural heritage,” which, interestingly, embraces tangible “instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces” [

5] (p. 249), [

45] (Article 2). This replacement implies that the attributes listed under “conditions of authenticity” in the Operational Guidelines [

9] (Paragraph 82) would become the attributes of continuity. In fact, the same study has found that “at least 263 properties were inscribed on the World Heritage List not because their values are truthfully and credibly expressed through a variety of attributes as per the Operational Guidelines (Paragraph 82), but because their values and attributes continue to exist” [

5] (p. 243). Although the World Heritage resource manual on management of cultural properties links the concept of continuity to “living heritage” and the attribute of “function” in particular [

33] (pp. 19, 28), the same study has found that continuity is not only relevant to living heritage or to function [

5]; it is in fact a qualifying condition that underpins the OUV of many cultural properties that belong to different heritage categories [

5] (pp. 251-271). One may add that it necessarily underpins the OUV of many natural properties as well because the concept of continuity is embedded in the wording of the inscription criteria itself, notably (vii) “natural phenomena” that happen or continue to exist, (viii) “on-going geological processes,” (ix) “on-going ecological and biological processes,” and (x) “biological diversity” that continues to exist [

9] (Paragraph 77), see also [

4] (p. 4).

As mentioned in the previous section of this article, IUCN discussed the importance of ensuring “the continuing integrity” of all World Heritage sites at the Amsterdam meeting in 1998 [

29] (p. 3). This article takes this idea further, arguing that continuity is what maintains wholeness, maintains intactness, and prevents adverse effects of neglect through maintenance and monitoring over time [

9] (Paragraph 88(a)(b)(c)). Continuity is what sustains values and attributes, as well as cultural and natural diversity. Although it is not mentioned in the “Protection and Management” section of the Operational Guidelines, continuity is implied: “Protection and management of World Heritage properties should ensure that the Outstanding Universal Value, including the conditions of integrity and/or authenticity at the time of inscription, are sustained or enhanced in the future” [

9] (Paragraph 96), see also [

31] (p. 89). The words “sustained” and “in the future” echo continuity. They echo “the ability to last or continue for a long time” —which is the basic definition of “sustainable (also sustainability)” provided in the UNESCO policy [

13] (p. 17). This observation suggests that continuity is not only a conservation principle, but also a sustainable development principle.

One may argue that the concept of sustainable development was anticipated in Articles 4 and 5 of the Convention [

6], see also [

46] (p. 77), [

47] (p. 84). It is also implied in Goal 3 of the Strategic Action Plan 2012–2022 for the implementation of this Convention [

14] (p. 2). The Operational Guidelines mention it many times, but provide little guidance to States Parties on how to contribute to sustainable development. They simply indicate, “States Parties [...] have the responsibility to [...] contribute to and comply with the sustainable development objectives, including gender equality, in the World Heritage processes and in their heritage conservation and management systems” and “Sustainable development principles should be integrated into the management system, for all types of natural, cultural and mixed properties, including their buffer zones and wider setting” [

9] (Paragraphs 15(o), 132.5). The Operational Guidelines do not spell out what the other “objectives” are and what the “principles” are.

What is certain is that sustainable development has three pillars that were consolidated at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit)—i.e., environmental protection, economic growth, and social equity—but a fourth pillar, advocated by UNESCO, can be added, i.e., culture [

48]. One cannot help but notice that the word “sustainable” echoes continuity (e.g., to exist, endure, persist) and the word “development” echoes change (e.g., to advance, grow, progress). A simple observation, but an important one nonetheless: sustainable development unites the need for continuity with the benefits of change. This change, however, should be compatible with its surrounding context and with the objective of allowing future generations to meet their own needs. In the World Heritage context, change/development must also be compatible with the objective of protecting OUV as noted (albeit briefly) in the UNESCO policy [

13] (Paragraph 25), the World Heritage resource manual on management [

33] (pp. 12, 23, 101, 125), and the Advisory Bodies’ guidance on impact assessments [

36] (Paragraph 5.11), [

37] (p. 5).

Compatibility refers to the harmonious co-existence of change with its surrounding context or to the harmonious integration of change into its surrounding context. If change is compatible, it is contextual, harmonious, sensitive, sympathetic, appropriate, acceptable, and thoughtful, which are relevant synonyms. This concept appears in ICOMOS Charters, some of which must be mentioned here to make a point. For example, “Replacements of missing parts must integrate harmoniously with the whole” according to the Venice Charter [

20] (Article 12); “The introduction of contemporary elements in harmony with the surroundings should not be discouraged” and “New functions and activities should be compatible with the character of the historic town or urban area” according to the Washington Charter [

49] (Articles 8, 10); “compatible use” is encouraged in the Burra Charter [

41] (Articles 1.11, 7.2); and “The characteristics of materials used in restoration work (in particular new materials) and their compatibility with existing materials should be fully established” as per the ICOMOS Charter—Principles for the Analysis, Conservation and Structural Restoration of Architectural Heritage [

50] (Article 3.10). This concept is also evident in other ICOMOS documents, such as the New Delhi Declaration on Heritage and Democracy, which encourages developing design guidelines because “Specific guidance is necessary to ensure the harmonious insertion of contemporary interventions into heritage settings” and to “secure cultural continuity” [

51] (pp. 3, 4). The Madrid-New Delhi Document, moreover, explains that integrity must be protected from “unsympathetic change or interventions,” adding that these “should be discernible as new, identifiable upon close inspection, but work in harmony with the existing,” for example, “character, scale, form, siting, landscape, materials, colour, patina and detailing” [

52] (Articles 2.1., 7.1, 7.2). Despite all these Charters and documents, ICOMOS has not introduced compatibility into the conceptual and operational framework of the World Heritage system. To this day, it is not mentioned in the Operational Guidelines.

Many ICOMOS Charters and documents, however, overlook the intangible aspects of compatibility. For instance, the Venice Charter suggests “new construction” can be harmoniously integrated if it does not “alter the relations of mass and colour,” and suggests “additions” can be allowed if “they do not detract from the interesting parts of the building, its traditional setting, the balance of its composition and its relation with its surroundings” [

20] (Articles 6, 13). This Charter ignores the fact that while new projects may fit into the physical, visual or spatial context, they may not necessarily fit into the social or cultural context. Contrary to what is implied in this Charter, compatibility is not only a matter of achieving physical or visual or spatial connectivity between existing buildings and proposed change. Proposals for change should not “be accepted or rejected solely on the basis of style” and appearance [

53] (p. 4), see also [

54], because the sense of what is compatible in a given context is beyond pre-determined expectations of what buildings built at a certain time ought to look like. Compatibility is environmentally, economically, socially and culturally dependent [

55]. For example, a building may be deemed environmentally and economically compatible if its construction involves careful use of resources and money and if it is beneficial (e.g., local employment); climate compatible if it is designed and constructed in response to the prevailing climatic conditions of the locality; socially or culturally compatible if it meets the needs of users in the present. It is not only about respecting the physical or visual legacy of the past, but also about meeting the needs of the present and reaching out to communities. This explains why compatibility is an expression of sustainability; it underpins sustainable development.

Achieving the goal of compatible change in heritage places is a challenge, as many authors have noted [

56], and yet ICOMOS barely addresses the issue of compatibility in its guidance on heritage impact assessments [

36] (Paragraph 5.11). The World Heritage resource manuals and the Operational Guidelines also discuss impact assessments [

31] (p. 89), [

33] (p. 86), [

9] (Paragraphs 110, 118bis), but they do not make clear to States Parties that the main purpose of undertaking an impact assessment is to ensure that a proposed project is compatible with the objective of protecting OUV. Here, it is worth noting that an impact assessment is not entirely objective, because whether a proposed project “results in negligible, minor, moderate or major change to a particular attribute of the OUV is left to the interpretation of the assessor” [

57] (p. 343). This is not to say that a sound judgement is not possible, but that the Operational Guidelines should acknowledge the impossibility of preparing purely objective heritage impact reports.

Compatibility is also a recurring concept in UNESCO Recommendations. For example, the Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas promotes “functions that are compatible with [the] specific character” of the urban and rural fabric, and accepts the application of “security standards [...] provided that this be compatible” with the “preservation of cultural heritage” [

58] (Items 21, 27, 33). The Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL), furthermore, promotes the HUL approach to “ensure that contemporary interventions are harmoniously integrated with heritage,” adding that urban planning policies and practices should place “Special emphasis” “on the harmonious integration of contemporary interventions into the historic urban fabric” [

16] (Items 12, 22). It was created as a result of the Vienna Memorandum, which is a transitional document that invited the possibility of formulating a new Recommendation “with special reference to the contextualization of contemporary architecture” in order to prevent adverse “impact on the integrity of a World Heritage property” and to maintain “continuity of culture through quality interventions” [

59] (Recommendations(A)(C), Paragraphs 29, 21). The word “contextualization” suggests that the design of contemporary architecture should be context-specific. In other words, the design should establish continuities with the surrounding context and be compatible. This is an important point because it clarifies “the reason for this Recommendation,” which was “motivated by increasing problems that threaten the integrity and the traditional continuity” of historic urban areas [

60] (p. 213), such as the construction of high-rise buildings in and near these areas. Accordingly, the HUL approach aims more at securing the integrity and continuity of the attributes of urban heritage than at protecting the authenticity of these attributes.

In fact, the pioneers of the HUL approach explain that interventions “need to respect integrity and the continuity of the design features of a given place, a basic ‘rule’ of intervention in historical settings” [

61] (p. 73), see also [

62] (p. 54). Scholars agree that ensuring “the continuity” of “attributes is important” and “finding ways to address development needs and potentials in a way that is compatible with the heritage character is equally important in this approach” [

63] (p. 257). For this reason, one may argue that the HUL approach is about managing continuity and compatible change [

4] (endnotes 3, 4). Although the notion of “compatibility” is not mentioned in the Recommendation, its importance is evident through the expressions “harmoniously integrated” and “harmonious integration”, which, of course, echo integrity [

16] (Items 12, 22). The notion of “continuity” is not mentioned either, but it is discussed in scholarly literature about the HUL approach, as explained earlier, see also [

64]. The HUL Guidebook relates this notion to knowledge and planning tools, noting that “impact assessments should be used to support sustainability and continuity in planning and design” [

65] (p. 14), see also [

16] (Item 24(b)). One may argue that continuity is relevant to the application of the other three tools mentioned in the Recommendation as well: continued civic engagement to identify values, develop visions, set goals, agree on actions to safeguard heritage and promote sustainable development (Item 24(a)); continued review of regulatory systems to better address the conservation vs. development struggle over time (Item 24(c)); continued provision of financial aid to build capacities and to support income-generating development, local enterprise, and partnerships so that the HUL approach can remain financially sustainable (Item 24(d)) [

16]. This approach is not only applicable to urban heritage or historic cities, but to other heritage categories, as some authors have argued [

4] (p. 7). Despite growing interest in this approach, it is not yet included in the Operational Guidelines. One may argue that its inclusion and application can be facilitated if the concepts of continuity and compatibility are operationalized.

The application of this approach requires the identification of values. It is difficult to identify values, especially at the urban scale where the heritage in question encompasses an entire city. It is also difficult to determine the balance between continuity and change. One needs to weigh the desirability of maintaining the integrity of a property against the benefits, e.g., social and economic, of a proposed development project. A Statement of Significance can help clarify what needs to continue, and what might be the tolerance for change. It captures all the identified values and attributes of a property—not just its OUV. It is an important tool in heritage planning and management [

66] (p. 200) and “the key to the broad landscape approach that is encapsulated in the concept of historic urban landscapes” [

67] (p. 102). In accordance with the Burra Charter [

41], the World Heritage resource manual on management of cultural properties recommends formulating a comprehensive Statement of Significance that captures the OUV and the other values of a property, and using it as the basis for its management [

33] (pp. 25, 137). This implies that “all cultural and natural values of the [property] to be listed should be a mandatory part of the listing submission” even if the property will only be inscribed as cultural World Heritage or only as natural World Heritage because a property is often “an inextricable mixture of natural and cultural values” that should be acknowledged in the management plan to maintain their continuity [

68] (pp. 54, 50). However, a comprehensive Statement of Significance is not a mandatory requirement for the nomination of properties for inscription on the World Heritage List as mentioned earlier in this article. The Operational Guidelines only request a Statement of OUV [

9] (Paragraph 132, Annex 10).

Speaking of the Burra Charter, it must be observed that this internationally recognized Charter was updated many times between 1979 and 2013, and yet the notion of “authenticity” was never mentioned in its various versions. One may argue that the Burra Charter accords greater importance to honesty—which is why “new work should be readily identifiable” [

41] (Article 22.2) and why “reconstruction should be identifiable on close inspection or through additional interpretation” [

41] (Article 20.2) to prevent the observer from thinking that what she/he is observing is old or original as opposed to new or reconstructed work—than truth. One may add that the Venice Charter also accords great importance to honesty because new work “must be distinct from the architectural composition and must bear a contemporary stamp” [

20] (Article 9) and “must be distinguishable from the original” [

20] (Article 12). In fact, honesty is “A second meaning of the word ‘integrity’ [...] which ventures into the realm of ethics” [

66] (p. 206). In the historic environment, honesty implies the legibility of the intervention, and therefore the absence of deception [

69], which is a philosophy central to the values of John Ruskin. According to Ruskin, “the principle of honesty must govern our treatment” given that “everybody wants integrity” in this world [

70] (pp. 42, 97). Ruskin was a preservation purist who opposed restoration, but “the principle of honesty” was embedded in Charters to guide restoration work nonetheless, such as the Venice Charter. This explains why interventions, such as restorations, reconstructions, and additions to historic buildings, should be distinct/distinguishable/identifiable/recognizable. They should be obvious to lay people (or to the trained eye of specialists depending on the nature of the intervention). Distinction, therefore, is about honesty, which is the other meaning of integrity, rather than authenticity [

69]. This is an important point because it shows that by embracing the full meaning of integrity—i.e., wholeness, intactness, absence of threats, and honesty—in concert with continuity and compatibility, the requirement of authenticity for cultural properties in the Operational Guidelines becomes redundant.

5. Discussion

ICOMOS Secretary-General Ernest Allen Connally recommended integrity (and unity) in preparation for the Morges meeting, in 1976, to nominate cultural properties for inscription on the World Heritage List [

18]. ICOMOS pioneers, such as Raymond Lemaire, however, preferred authenticity [

23,

24], which found its way into the Operational Guidelines [

7]. The decision of the World Heritage Committee to operationalize authenticity only for cultural properties reinforced the culture/nature divide. The application of the conditions of integrity to both cultural and natural properties, and therefore the application of one common approach for nomination, was discussed at the Parc National de la Vanoise and the Amsterdam meetings, in 1996 and 1998 [

28,

29]. Although ICOMOS “agreed with IUCN that the ‘test of authenticity’ could be replaced by ‘conditions of integrity’” [

29] (p. 3), this replacement did not happen, and the culture/nature divide persisted despite the unification of the two sets of criteria for cultural and natural properties in 2005 [

8].

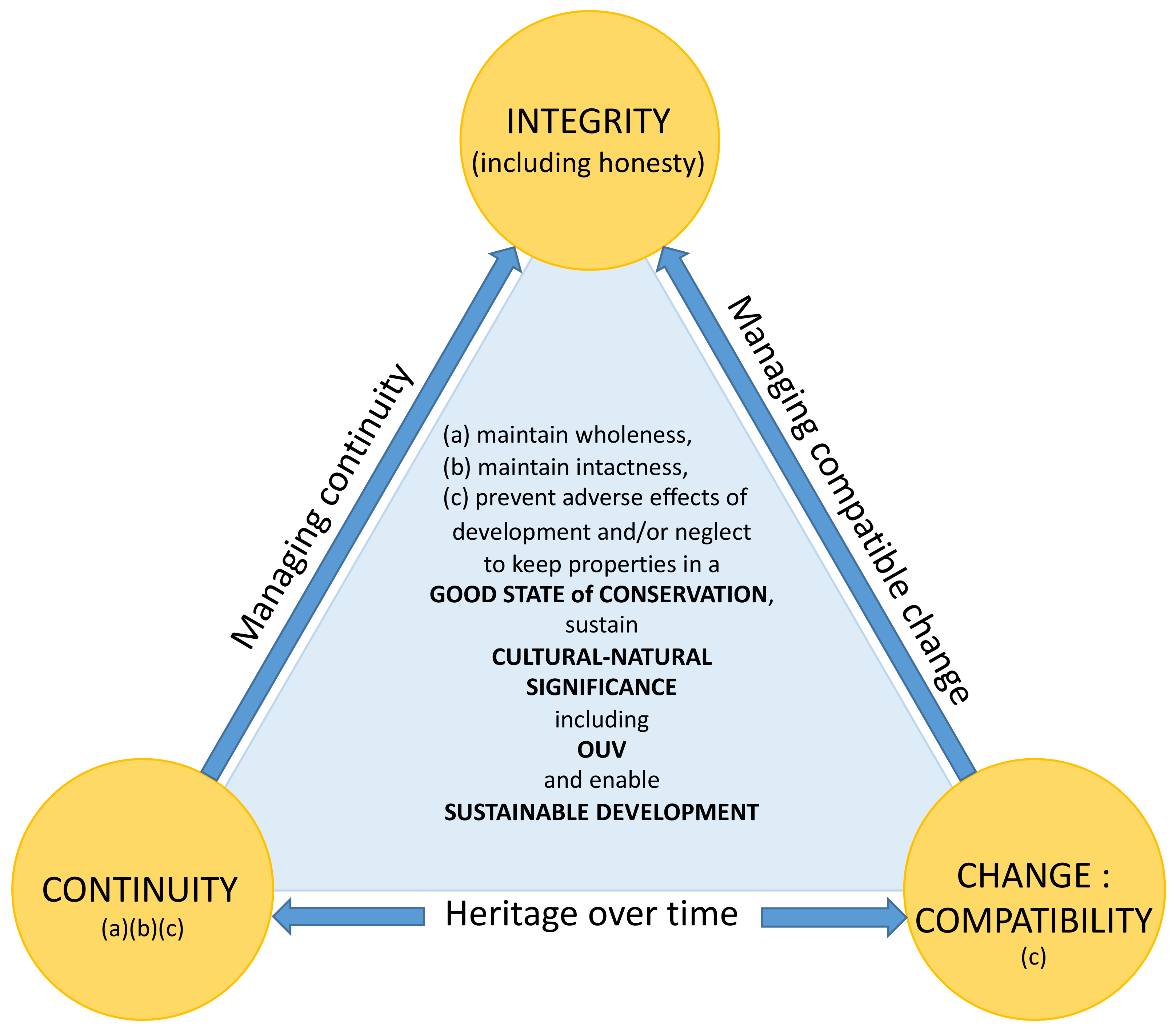

An alternative conceptual and operational framework for nomination, evaluation, protection and management that bridges the culture/nature divide is proposed in this article. Here, the “attributes” and “features” identified in the Operational Guidelines and the World Heritage resource manual [

9] (Paragraphs 82, 92-95), [

31] (pp. 31, 32) are the attributes/features of continuity and, where change is involved or proposed, compatibility. Continuity and compatibility are qualifying conditions of integrity. The former maintains wholeness, maintains intactness, and prevents adverse effects of neglect [

9] (Paragraph 88(a)(b)(c)) and the latter mainly prevents adverse effects of development/change [

9] (Paragraph 88(c)). Here, “integrity” encompasses the values and meanings that people attach to tangible and intangible attributes, and includes the principle of honesty. For example, a reconstruction project may be proposed to re-establish the wholeness and intactness of a destroyed property, but the project should not only enable the continuity of attributes if possible or suggest compatible attributes (e.g., materials, functions) to regenerate values and meanings, but should also be distinguishable from the original for honesty and legibility purposes to prevent people from thinking that destruction did not happen. Different indicators of distinction can be explored [

69]. Together, continuity and compatibility strengthen the requirement of integrity and guide the protection and management of properties to keep them in a good state of conservation, to sustain their cultural-natural significance including OUV, and to enable sustainable development. A comprehensive Statement of Significance that captures the OUV and the other identified values and attributes of a property at the national, local, and community levels is here essential. This Statement should not be fixed; it should be open to review because “our appreciation” of the significance of a property “may change as a result of new research, changing values or the continuing history” of the property [

71] (p. 6).

This alternative conceptual and operational framework places heritage between continuity and change over time. It acknowledges that “Cultural heritage, just like natural heritage, is a continuously evolving process, not a legacy that was in any way complete” [

72] (p. 3). Continuity and change are necessary so that heritage can remain relevant to people, but proposed change such as new development projects should be compatible to prevent adverse effects. Moreover, because continuity and compatibility already underpin many Statements of OUV [

5], the practical application of this policy proposal to existing World Heritage properties and management plans will not be as technically challenging as the reader may assume. This proposal can also facilitate the integration of the HUL approach [

16] into the Operational Guidelines, through the management of continuity and compatible change, which, as a consequence, would harmonize the implementation of the Convention with that of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

17]. It can also complement the work of the World Heritage Leadership Programme [

15] and the joint initiative between ICOMOS and IUCN, known as the “Connecting Practice” project [

73,

74], because it shows how to bridge the culture/nature divide. If adopted, the “system of collective protection of the cultural and natural heritage of Outstanding Universal Value” established by the Convention would become more credible, practical, and effective [

6] (Preamble, Paragraph 8). This policy proposal is illustrated in

Figure 1.

To demonstrate the practical application of this policy proposal, an example from the World Heritage List is given here: Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley in Afghanistan [

75] (online). Most readers will be familiar with this property because it was inscribed after the Taliban destroyed the two standing Buddha statues. There is general agreement among scholars that “authenticity becomes even murkier when it is applied to the category of cultural landscapes” [

76] (footnote 99), especially because of the dynamic interaction between people and their environment [

9] (Annex 3). In addition, many believe authenticity is “less relevant” than integrity, “particularly for living cultural landscapes” [

77] (p. 48).

The section dedicated to authenticity in the Statement of OUV does not even mention authenticity; it is based on continuity:

The cultural landscape and archaeological remains of the Bamiyan Valley continue to testify to the different cultural phases of its history. Seen as a cultural landscape, the Bamiyan Valley, with its artistic and architectural remains, the traditional land use and the simple mud brick constructions continues to express its Outstanding Universal Value in terms of form and materials, location and setting, but may be vulnerable in the face of development and requires careful conservation and management.

[

75] (online, emphasis added).

The attributes (form, materials, location, setting) are explicitly linked to the qualifying condition of continuity—not authenticity. Moreover, the end of the last sentence suggests that any proposed development/change, which may include the envisioned reconstruction of the destroyed Buddha statues, should be compatible to prevent adverse effects. The section dedicated to integrity in the Statement of OUV is also brief:

The heritage resources in Bamiyan Valley have suffered from various disasters and some parts are in a fragile state. A major loss to the integrity of the site was the destruction of the large Buddha statues in 2001. However, a significant proportion of all the attributes that express the Outstanding Universal Value of the site, such as Buddhist and Islamic architectural forms and their setting in the Bamiyan landscape, remain intact at all 8 sites within the boundaries, including the vast Buddhist monastery in the Bamiyan Cliffs which contained the two colossal sculptures of the Buddha.

These two sections can be merged into one piece to describe the integrity of the property whilst explaining why continuity and compatibility support its inscription, protection and management in line with

Figure 1. In fact, the property’s “Authenticity and Integrity” were addressed together in the ICOMOS evaluation report [

78] (p. 3), parts of which was used to draft two separate sections in the Statement of OUV for integrity and for authenticity (or rather continuity), as shown above.