Abstract

This paper presents the results of a study on gender roles and gender restrictions within a certain type of festival in Japan—the Yama Hoko Yatai float festivals—taking place in various regions throughout the country. In addition to mapping gender roles, the study was also focused on mapping changes that have occurred in these gender roles and identifying the reasons for the changes. A survey was conducted among the preservation associations connected to the 36 concerned festivals in the form of a questionnaire sent by post. The results of the survey show the differences between the festivals in terms of gender roles and gender restrictions. While some festivals display a more gender-inclusive approach, others are reportedly performed exclusively by men, and some display gender-based role divisions. Approximately half of the replies reported that some changes in the gender roles had occurred, and the primary direction of change was towards increased inclusion (increased female participation). Concerning the reasons behind the increased female participation, the replies suggest that a primary trigger of change was a shortage of people to participate, caused by declining birth rates. A change in attitude/consciousness towards female participation was mentioned in a few cases.

1. Introduction

Intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is often said to have a strong connection to gender. For example, some traditions are gender-coded and participation is linked to the participants assigned gender. The goal of this study is to map the gender circumstances (gender roles and gender restrictions and changes to these) within a certain type of festival in Japan, with the aim of deepening the understanding of the interaction between ICH and gender, and especially how changes to traditional gender roles within practices occur.

The Yama Hoko Yatai float festivals are an interesting arena to study changes in gender roles and gender restrictions. Traditionally, the float festivals are/have been male events, and a large number of the festivals have restrictions regarding female participation. While a number of festivals have opened up to allow for women to participate in some roles, men are generally the ‘main’ participants. How come changes to the gender roles and rules have occurred in some of the festivals, while not in others? What triggered the changes? This study seeks to: (a) map the current gender roles (tendencies and rules), (b) map changes that have occurred in the gender roles, and (c) identify reasons for the changes. Data was collected through a survey conducted among the preservation associations (hozonkai) connected to the festivals. The study, conducted as part of the author’s doctoral research, is one part of a larger research design. The results of the survey are followed up by an interview study conducted with a number of preservation associations, focused on festivals that have undergone changes in the gender roles and gender restrictions, in order to examine the circumstances surrounding the changes in-depth. The results of the interview study will be presented in a separate paper.

Japanese festivals are typically organized and performed by the local communities. Nowadays, these local festival communities also have an official organizational structure, in the form of preservation associations. The preservation associations are engaged in the continuation of the practice in question and are generally constituted of active practitioners and stakeholders. The National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals represents the preservation associations of 36 different Yama Hoko Yatai festivals, and this study is targeted to these festivals.

The Yama Hoko Yatai float festivals are a type of festival taking place in various regions of Japan. At the centre of the festivals are processions of large floats being pulled, pushed or other ways manoeuvred around town (or on water), usually with some form of performance taking place atop the floats, such as hayashi music. While the festivals all have some key features in common, there are large variations between them, and yama, hoko, and yatai are words used to describe different kinds of festival floats. This type of festival developed in Kyōto, and later spread to other regions [1]. The festivals developed as distinctly urban festivals, different from festivals found in the rural areas, and later spread to provincial and rural towns [2]. Some commonly occurring roles/assignments include: pulling the floats, playing music, handling the poles used for manoeuvring the floats, supervising the procession, etc. Apart from the front-stage roles, there is also work going on ‘behind-the-scenes’, including preparations of the floats as well as preparing food and looking after the children who are participating. Visitors coming to watch the festivals also play a part. Who (which roles) should be considered as participants is an open question. In this study, the term participation is primarily used in the meaning of formal participation, recognized by the preservation associations. As such, the results of the survey will indicate who are considered as participants according to the preservation associations.

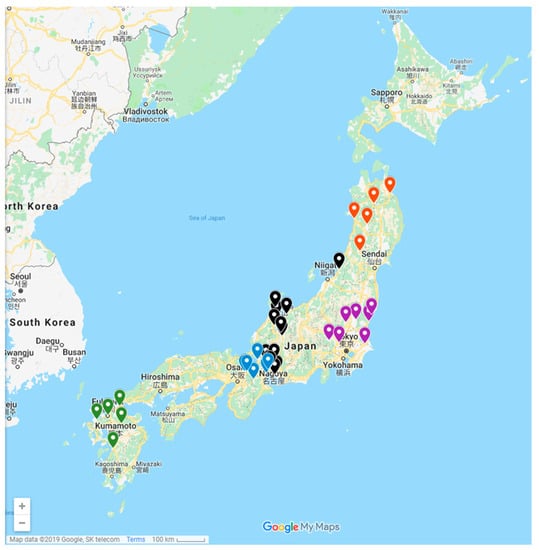

The 36 festivals examined in this study are protected cultural properties under Japanese heritage legislation. They are all individually designated as Important Intangible Folk Cultural Properties under the Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties. Furthermore, 33 of the 36 festivals are also inscribed as a group on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity (RL) under the name ‘Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan’. In terms of geographical spread, the festivals take place in various regions, from the Tōhoku region in the north to Kyūshū in the south. See Table 1 for a list of all 36 festivals. A map can be found in Appendix A.

Table 1.

Overview of the 36 festivals examined: location, name, and year of designation as Important intangible folk cultural property under Japanese heritage legislation.

Matters of gender within ICH can be complex, and more research on this subject is needed. In particular, more research is needed on the dynamics of gender in ICH—on how gender can be a factor is the reiteration of traditional practices, and how traditional practices influence the reiteration of gender.

Within the heritage field in general, gender is, as Wilson points out, a perspective that is often treated as a ‘niche topic’ [3] (p. 3). At the same time, gender warrants attention as a factor in the production of cultural heritage. Heritage is, as Smith argues, gendered [4]. Smith writes that “it is gendered in the way that heritage is defined, understood and talked about and, in turn, in the way it reproduces and legitimizes gender identities and the social values that underpin them” [4] (p. 161) and points out that heritage is too often male-centred. This is also part of what Smith calls the authorized heritage discourse (AHD) [5], a notion of the professional discourse permeating ‘Western’ international as well as national debates on heritage, influencing the way heritage practitioners handle and talk about heritage. Smith writes that “one of the many consequences of this discourse is that it has been masculine values and perceptions, particularly masculine values from the elite social classes, that have tended to dominate how heritage has been defined, identified, valued and preserved” [4] (p. 162). This means that what is identified as valuable, as heritage, are things and places that correspond to the AHD. The AHD itself is influenced by certain “social experiences and values”, since the AHD was “built not only on professional values and concerns, but also on certain class and gender experiences and social and aesthetic values” [4] (ibid.).

How to approach gender within the field of ICH, and perhaps in particular the role that gender plays in traditional practices, seems to be problematic. The difficulties in how to approach gender within ICH can be seen reflected in the way gender matters have been handled within the framework of UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Within the context of the 2003 convention, matters regarding gender have until recently been treated as somewhat of a grey area, easier to avoid than to address. How to address gender discrimination within the context of the convention has been an unspoken issue [6]. The convention’s definition of ICH contains criteria pertaining to human rights considerations [7] (article 2.1). However, Blake points out that in the case of traditional cultural practices it can be difficult to determine “on which side of the ‘human rights line’ a cultural manifestation falls” [8] (p. 286). A 2013 evaluation of the convention, conducted by UNESCO’s Internal Oversight Service, pointed to the under-addressed gender equality aspect as the ‘elephant in the room’ [9] (paragraph 72). Blake writes that the reluctance to address issues pertaining to gender might stem from a nervousness from the state parties and other stakeholders of the convention of having to ‘deal with ICH elements—some of which may already be inscribed on the RL—that may pose a challenge to the principles of non-discrimination and equality’ [8] (p. 182). Moghadam and Bagheritari expressed concern that the convention could fail to protect the human rights of women, due to the lack of reference to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) as well as due to its gender-neutral language [10]. They argue that ‘culture’ should not be used as a justification for gender inequality [10]. While not specifically addressing the 2003 convention, concern that culture is used to defend gender discrimination has also been expressed by Shaheed, former UN Special Rapporteur on cultural rights [11]. In recent years, gender matters have started receiving increased attention within the context of the 2003 convention. In the years following the aforementioned evaluation of the convention in 2013, revisions of the tools and official forms of the convention were made to add a gender aspect to the material.

It seems clear that the issue of gender within tradition practices—such as the float festivals—needs more research. One part of this is examining the gender roles and gender restrictions being upheld, recreated and renegotiated within the festivals. While previous research exists concerning the individual festivals, the availability of information on gender roles and gender restrictions vary. Furthermore, to the author’s knowledge, and according to the National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals (reference to a meeting with a representative of the National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals, Chichibu city, Saitama Prefecture, 9 May 2018), there are no previous studies specifically mapping the gender roles of the festivals.

Float festivals are common in Japan, and women are traditionally denied participation, for reasons of religious concerns about purity [12] (p. 13). The Kyōto Gion festival is arguably the most famous of the float festivals. While the Kyōto Gion festival of today is in many ways a predominately male festival, research suggests that the festival might have had female participants in its early days, based on early Edo period depictions of women riding on hoko floats [13]. According to Wakita, the custom of nyonin kinsei (prohibition of female participation) gained foothold in the mid to late Edo period society, and came to affect festivals as well [13] (p. 215). Wakita writes that this was connected to the kegare belief, involving the idea that blood from menstruation and childbirth is defiled/defiling, leading to rejection and discrimination of women [13] (ibid.). In that sense, the nyonin kinsei tradition of the Kyōto Gion festival is an invented tradition [12] (p. 13). The modern-day gender restrictions of the Kyōto Gion festival have received some attention as they have been challenged and debated. How the discussions proceeded has been described by Brumann [14].

Concerning the social significance of festival participation, Roemer [15] has described how participation in the Kyōto Gion festival is associated with a positive sense of community, yielding lasting social support networks. Noting the limitations in roles available to women compared to men, Roemer writes that “the kinds of communal bonds formed and social support received reflect the predominantly paternalistic nature of this traditional festival hierarchy” [15] (p. 190).

The social significance of the festivals is also mentioned in the nomination file for inscribing ‘Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan’ on the RL. The file describes how the float festival “lies at the heart of the lives of all members of the concerned community as the main event of each region” [16] (p. 5) and how the festivals “also have significance in the spiritual lives of the community members as sources of their vitality” [16] (ibid.). The nomination file goes on to describe how the festivals “fulfill the social functions of uniting all community members and allowing them to reaffirm their identities as members of the community every year” [16] (ibid.).

Morinaga’s and Doi’s [17] study on men’s and women’s perception of the Hakata Gion Yamakasa festival found that the awareness differed between men and women, having different roles. The study found that men were more focused on ‘the festival itself’ (matsuri sono mono), while women were more focused on support and on looking after the family [17].

The nomination file of ‘Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan’ for the RL contains only general mentions of gender and does not mention gender restrictions specifically. The festivals are described as events where all members of the concerned communities take part [16].

The festivals’ most significant feature is the communities’ devotion to the preparation and celebration of the festivals. Community members including men, women, the young and the elders share their tasks and responsibilities all year around preparing for the float festivals, the most important event of the year for them. Float festivals therefore foster communication and teamwork between community members, and play vital roles in uniting them. […] The festivals are planned in a way that reflects the diversity of ages among members of the local communities and includes all genders. […] All members of the community look forward to and practice the float festivals. […] In order to successfully prepare for and celebrate the festivals, each member of the communities takes charge of his/her specific role and works together. Such cooperation creates bonds within the communities that transcend age, status and gender.[16] (pp. 4–5)

This study seeks to examine the current gender roles and gender restrictions of the 36 float festivals, as well as changes in these roles and restrictions. As such, the results will also provide useful information for future studies.

2. Materials and Methods

Regarding methodology, a survey (approval obtained from the University of Tsukuba Arts Division Conflict of Interest Committee in July 2018, file no: Gei 30-3) was conducted among the 36 preservation associations affiliated with the target festivals, using a questionnaire sent by post. The questionnaire was sent out in September 2018. The questionnaire was sent to the 36 preservation associations in one (1) copy per association. The survey was, in other words, addressed to each association as a group, and not to its individual members. The questionnaire was sent out with the support of the National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals. The contents to be sent out to each preservation association (questionnaire, reply envelope addressed to the University, request letter, practical instructions) was first sent to the National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals, who posted the contents to the preservation associations. The replies were sent directly from the preservation associations to the University (i.e., not via the National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals) by post. The response rate was 64 percent (23 out of 36 festivals). The replies were received between 28 September and 2 November 2018 (postmark date).

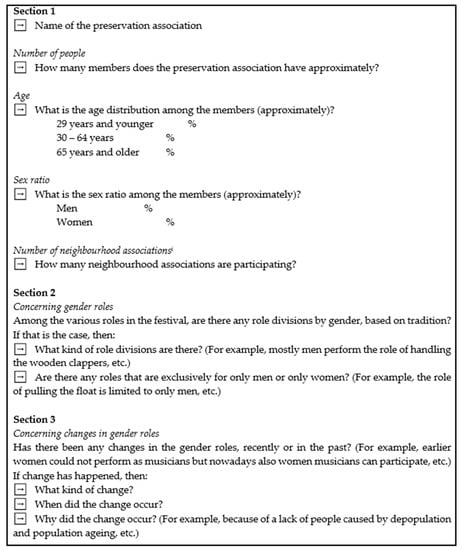

The questionnaire had three sections: basic information, gender roles, and changes in gender roles. See questions in Figure 1. The section on gender roles was designed to identify indications of the severity of the role divisions, by making a distinction between tendencies and rules. The first question of this section concerned all types of role divisions by gender, while the second question specifically concerned roles performed by one gender group exclusively.

Figure 1.

Questions posed in the questionnaire. Translation to English.

It should be noted that some of the questions in Sections 2 and 3 are accompanied by examples (see above). It should be taken into consideration the possibility that these examples might have had an influence on the replies. However, it should also be noted that the examples were selected to reflect common patterns, based on prior knowledge about the festivals.

The survey was conducted in Japanese. The replies have been translated to English by the author. In making the translations, the author chose to prioritize keeping the wording close to that of the original text, rather than considering eloquence, and as a result, the language in the translations may appear awkward.

This study is focused on the results of the survey. The results of the survey are compared to other sources of information, for example, official descriptions pertaining to the designation decisions, in the author’s doctoral thesis. It may also be noted that while the received information is to some extent dependent on the informant who answered the questionnaire, the survey requested information solely on facts, and not on opinions.

It may also be noted that, while arguably problematic, a binary gender system is used in the questionnaire. As for the usage of the terms gender and sex, it may be noted that the English translation of the questionnaire uses both the terms sex ratio and gender roles. In the Japanese version of the questionnaire, the term danjohi is used in Section 1, which can be translated to either sex ratio or gender ratio. In Sections 2 and 3, the terms danjo no yakuwari and danjo no yakuwari buntan are used, which can be roughly translated to ‘the roles of men and women’ and ‘the role division of men and women’. In terms of the categorization of people into the two groups ‘women’ and ‘men’, this study is interested in the social significance and implications connected to these categories. It may also be mentioned that while a distinction is often made between biological sex and socially constructed gender, Butler has argued that the notion of sex itself is already gendered [18].

3. Results

The response rate was 64% (23 of 36 festivals). See Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A for compilations of the received replies. Key observations are presented below.

3.1. Observations: Concerning Changes in Gender Roles

Approximately half of the replies reported that some changes in the gender roles had occurred. The primary direction of change was towards increased inclusion, but exceptions exist. In other words, it is more common that festivals are opening up for more inclusive participation (allowing women to participate in roles previously open only to men), rather than becoming more restricted.

The most common trigger of change was a shortage of people who could participate. The most commonly mentioned reasons hind the shortages were shōshika (declining birth rates) and shōshikōreika (declining birth rates combined with an ageing population). Another reason mentioned was fixed dates for the festival, causing the festival to some years fall on weekdays. Regarding other triggers of change apart from a shortage of people, the replies from three of the festivals mentioned a change in attitude/consciousness towards female participation in some form (all three of them in combination with a shortage of people). It can also be noted that all of the three festivals where a change in awareness concerning female participation was mentioned as a reason for the change in gender roles all changed around the same time. The Inuyama festival changed around 1997, Hitachi Furyūmono around 1998, and Seihakusai around 1999 and 2001.

3.2. Observations: Concerning Participation and Current Gender Roles

Around one fourth (slightly more if the Sunari festival is included) of the festivals (from where replies were received) are reportedly restricted to only male participants. The rest are mixed to some extent. It can also be noted that none of the festivals are restricted to only female participants. In the reply from Handa (the Kamezaki festival), the word nyonin kinsei, a term used to describe customary prohibitions of women from entering religious sites and performing religious practices, was used.

Women are often active in roles ‘behind-the-scenes’ (sometimes referred to as urakata). In the Yatsushiro festival, many women are participating as caretakers and helpers. In the Inuyama festival, mothers are in charge of taking care of the drummer children. In the Uozu festival, the behind-the-scenes roles, such as preparing tea, are performed by women. In the Takaoka festival, women take part in preparations and producing parts for the floats. In the Ōtsu festival, the woman of the family often handles costume matters. Women help with costume matters in the Sunari festival as well.

In the two festivals where the role of dancer was described, this role was reportedly performed by women. This was the case of the Kakunodate festival in Senboku, as well as the Hanawa festival in Kazuno. The roles most commonly performed by both men and women are pulling the floats and that of musicians. The role of festival officer and roles involving the steering of the floats are often done by only men. This was the case in several of the festivals. In general, men are the ‘main’—or arguably front-stage—participants.

3.3. Observations: Other Characteristics

The preservation associations are, with few exceptions, male-dominated. The Takaoka festival is interesting for several reasons. This festival has the preservation organization with the largest number of members, and also with the largest diversity among its members, both in terms of age and gender. It is also the only preservation association with a roughly equal number of female and male members. However, this gender balance is not visible in the performance of “the festival itself” (sairei sono mono), where women do not participate, at least not front-stage. The operations and the management of the floats are entirely limited to men, and women participate only in the preparations.

The views on religiosity and gender differed between the festivals. The reply from Inuyama, where the festival used to be nyonin kinsei (prohibited for women) but is not anymore, expressed a change in the perception of religiosity and gender. The reply said that while declining birth rates might also have been a factor, it was the view of the preservation association that forbidding women from religious matters was groundless, writing that “it doesn’t make sense to ostracize women from religious matters such as festivals in the first place, and also, as a result of many discussions in the preservation association we concluded that the custom to abhor women is no more than a convention” (Shōshikōreika ni yori kodaikoren no jidō no kakuho ga konnan ni natta koto mo arimasu ga, somo somo shinji to shite no matsuri ni josei haiseki no kangae ha nai wake de aru shi, josei wo imikirau fūshū ha inshū ni suginai to hozonkai de giron wo kasaneta kekka de aru.). The reply from Ōgaki expressed a different view. The reply said that while it is not a rule, it is “a tacit understanding that women are not involved in religious matters” (Kimari ga aru wake de ha nai ga, anmoku no ryōkai de, josei ha shinji ni kakawatteinai.).

3.4. Observations: Regional Tendencies

The response rate varied between regions. Concerning the Tōhoku region, replies were received from four of the five festivals. Regarding the Kantō region, replies from three out of seven festivals were received. Eleven replies were received from the thirteen festivals of the Chūbu region. One reply was received from the six festivals in the Kinki region. As for Kyūshū, replies were received from four of the five festivals.

In terms of regional tendencies, the Kyūshū festivals appeared to be largely male events. Regarding the four replies received from Kyūshū, two festivals were performed by only men. In one festival, school girls were allowed to participate in some neighbourhoods while adult women’s participation had become restricted. One festival was mixed.

The festivals of the Tōhoku region featured a comparatively high frequency of reported role divisions affecting both women and men. There were indications of role divisions (dancing and shamisen is reportedly mostly handled by women while operating the floats is mostly handled by men) in three of the festivals. None of the festivals (from where replies were received) were all male.

The replies from the Chūbu region showed the greatest variation in gender rules. Some festivals reportedly did not have any gender roles in particular, while other festivals were performed by only men. More than half of the festivals had undergone changes in the gender roles/rules, opening up for female participation in roles that had previously been restricted to men. Furthermore, in one festival there have been discussions about allowing girls in case no boys are available for one particular role (no girls have come to participate yet). In another festival, performed only by men, the rules reportedly might change in the future to allow for girls in one particular role (since the number of boys has declined recently), but probably not for another ten years.

4. Discussion

The results of the survey show significant differences between the festivals in terms of gender roles and gender rules. While some festivals display a more gender-inclusive approach, others are reportedly performed exclusively by men, and some display gender-based role divisions. While changes towards greater gender inclusion have occurred in some festivals, in general, the festivals are still largely male arenas. The results show that, in general, men are the ‘main’—or arguably front-stage—participants while women’s participation is more conditioned and auxiliary. In terms of formal participation, it is interesting to note that nearly all of the preservation associations are male-dominated, and more than half of the preservation associations have only male members.

Concerning change, approximately half of the festivals have undergone changes in the gender rules. The primary direction of change was towards increased inclusion—i.e., opening up for women and girls to participate in the festivals in various roles. According to the replies, the changes were primarily triggered by practical reasons, namely because of a shortage of people to participate in the festivals. Gender equality considerations or similar were reportedly a contributing factor in some festivals. It could be noted that, while a shortage of people was written as an example in the questionnaire form (regarding the question concerning the reason for the change), gender awareness was not.

The results lead to further questions: what happens after a change has occurred to allow women to participate—how is the change perceived by the local/festival community? Does female participation become naturalized, and in that case, how long does it take? How is the perceived value and meaning of the festival affected? These questions are addressed by the author in a follow-up interview study which will be presented in a separate paper.

5. Conclusions and Remarks

The results of this study provide valuable information on the gender structures present within the float festivals and new knowledge about how changes in the gender roles and gender restrictions of these festivals occur. As such, in a wider context, the results offer insights into the role of gender in the practice of ICH.

To sum up, the results of the survey show that approximately half of the festivals (from where a reply was received) have undergone changes in terms of gender roles. The primary direction of change was towards increased gender inclusion. The primary reason for the change to allow women to participate in roles that had earlier been limited to men was reportedly a shortage of people to participate in the festivals, while a change in attitude/consciousness towards female participation was mentioned in a few cases. Consequently, seeing the advance in declining birth rates and the ageing population in Japan, there might be reason to assume that more festivals may change the restrictions on female participation in the coming years to allow for women to participate in more roles.

Funding

The research was made possible by the author receiving the Japanese government (Monbukagakusho: MEXT) scholarship.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the National Association for the Preservation of Float Festivals for their kind assistance in conducting the survey. The author would also like to thank all the preservation associations that participated. Finally, the author would like to thank her academic advisor, Nobuko Inaba, as well as the reviewers, for their valuable feedback and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. While the author is a recipient of the Japanese government (Monbukagakusho: MEXT) scholarship, the founding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Location of the 36 festivals. Colour coded by region: Tōhoku—red, Kantō—purple, Chūbu—black, Kinki—blue, Kyūshū—green.

Table A1.

Results of survey. Basic information. (Festivals from where no reply was received have been omitted).

Table A1.

Results of survey. Basic information. (Festivals from where no reply was received have been omitted).

| Name of Festival | Name of Preservation Association | Number of Members | Distribution of Members by Age Group | Distribution of Members by Gender Group | Number or Neighbourhood Associations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage Young (29 Yrs. and Younger) | Percentage Middle (30–64 Years) | Percentage Senior (65 Yrs. and Older) | Percentage Women | Percentage Men | |||||

| (text) | (text) | (no.) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (no.) | |

| 1 | Hachinohe Sansha Daisai no Dashi Gyōji | Hachinohe Sansha Daisai Dashi Matsuri Gyōji Hozonkai | |||||||

| 2 | Kakunodate Matsuri no Yama Gyōji | Kakunodate no Omatsuri Hozonkai | 100 | 0 | 80 | 20 | 5 | 95 | 18 |

| 4 | Hanawa Matsuri no Yatai Gyōji | Hanawa Bayashi Saiten Iinkai | 180 | 0 | 95 | 5 | 0 | 100 | 10 |

| 5 | Shinjō Matsuri no Yatai Gyōji | Shinjō Matsuri Yatai Gyōji Hozonkai | 12 (* 1) | 0 | 17 | 83 | 17 | 83 | 37 (* 2) |

| 6 | Hitachi Furyūmono | Hitachi Kyōdo Geinō Hozonkai (* 3) | 160 | 5 | 15 | 85 | 2 | 98 | 4 (* 4) |

| 10 | Kawagoe Hikawa Matsuri no Dashi Gyōji | Kawagoe Hikawa Matsuri no Dashi Gyōji Hozonkai | 16 (* 5) | 0 | 19 | 81 | 0 | 100 | 13 |

| 12 | Takaoka Mikurumayama Matsuri no Mikurumayama Gyōji | Takaoka Mikurumayama Hozonkai | 450 | 25 | 45 | 30 | 52 | 48 | 10 |

| 13 | Uozu no Tatemon Gyōji | Uozu Tatemon Hozonkai | 350 (* 6) | 20 | 50 | 30 | 10 | 90 | 7 |

| 14 | Jōhana Shinmeigūsai no Hikiyama Gyōji | Jōhana Hikiyama Matsuri Hozonkai | 70 | 0 | 10 | 90 | 0 | 100 | 9 |

| 15 | Seihakusai no Hikiyama Gyōji | Seihakusai Dekayama Hozonkai | 45 (* 7) | 0 (* 7) | 50 (* 7) | 50 (* 7) | 0 (* 8) | 100 (* 8) | 3 (* 9) |

| 17 | Furukawa Matsuri no Okoshidaiko Yatai Gyōji | Furukawa Matsuri Hozonkai | 65 | 0 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 100 | 12 |

| 18 | Ōgaki Matsuri no Yama Gyōji | Ōgaki Matsuri Hozonkai | 12 | 0 | 44 | 56 | 0 | 100 | 10 |

| 20 | Chiryū no Dashi Bunraku to Karakuri | Chiryū Dashi Rengō Hozonkai | 20 | 0 | 30 | 70 | 0 | 100 | 5 |

| 21 | Inuyama Matsuri no Yama Gyōji | Inuyama Matsuri Hozonkai | 34 | 0 | 44 | 56 | 3 | 97 | 16 |

| 22 | Kamezaki Shiohi Matsuri no Dashi Gyōji | Kamezaki Shiohi Matsuri Hozonkai | 95 | 0 | 56 | 43 | 0 | 100 | 5 teams |

| 23 | Sunari Matsuri no Danjiribune Gyōji to Miyoshi Nagashi | Sunari Bunkazai Hogo Iinkai | 68 (* 10) | 0 | 60 | 40 | 0 (* 11) | 100 (* 11) | 1 |

| 30 | Tobata Gion Ōyamagasa Gyōji | Tobata Gion Ōyamagasa Shinkōkai | 48 | 0 | 90 | 10 | 2 | 98 | 4 |

| 31 | Karatsu Kunchi no Hikiyama Gyōji | Karatsu Hikiyama Torishimarikai | 60 | 0 | 62 | 38 | 0 | 100 | 14 |

| 32 | Yatsushiro Myōkensai no Shinkō Gyōji | Yatsushiro Myōkensai Hozon Shinkōkai | 67 | 0 | 57 | 43 | 6 | 94 | 28 |

| 33 | Hita Gion no Hikiyama Gyōji | Hita Gion Yamaboko Shinkōkai | Circa 500 | 15 | 80 | 5 | 0 | 100 | 10 |

| 34 | Ōtsu Matsuri | Ōtsu Matsuri Hozonkai | (* 12) | (* 13) | (* 13) | (* 13) | (* 14) | (* 14) | 16 |

| 35 | Hitachi Ōtsu no Ofunematsuri | Hitachi Ōtsu no Ofunematsuri Hozonkai | 138 | 18 | 62 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 3 |

| 36 | Murakami Matsuri no Yatai Gyōji | Murakami Matsuri Hozonkai | 90 | 0 | 77 | 23 | 0 | 100 | 19 |

Additional information: (* 1) Officers only, the number of other participants is unknown. (* 2) 20 floats, 17 orchestras. (* 3) The reply concerns Hitachi Furyūmono. (* 4) 4 float branches. (* 5) However, 13 people are neighbourhood representatives. So formally it is 13 neighbourhoods + 3 people. (* 6) Number of households in the parish of Suwa Shrine in Uozu, Toyama pref. (* 7) Seihakusai Dekayama hozonkai (excluding the young lads/people [association] etc.). (* 8) Seihakusai Dekayama hozonkai. (* 9) Uochō Dekayama hozonkai, Fuchūchō Dekayama hozonkai, and Kajichō Dekayama hozonkai. (* 10) Composed of the Sunari ward assembly, Sunari reverance assembly, and drum and flute assembly. (* 11) However, there are 11 people registered in the women’s division in the Sunari reverance assembly dealing mainly with helping people dress. (* 12) The Ōtsu festival preservation association is made up of only the directors of each neighbourhood, and therefore there are no preservation association members as such. (* 13) Same as previous. (* 14) Same as previous. There are no female members in any of the neighbourhoods.

Table A2.

Results of survey: replies. Concerning gender roles and changes in gender roles. (Festivals from where no reply was received have been omitted.).

Table A2.

Results of survey: replies. Concerning gender roles and changes in gender roles. (Festivals from where no reply was received have been omitted.).

| Concerning Gender Roles | Concerning Changes in Gender Roles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Festival | Gender Tendencies | Gender Restrictions | What Change? | When? | Why? | |

| 1 | Hachinohe Sansha Daisai no Dashi Gyōji | Apart from the festival floats, the Hachinohe Sansha Daisai festival also includes folk performing arts and various processions. Many of the participants are only involved on the actual day of the festival, so it is difficult to assess the number of participants and their age distribution. Regarding gender roles, each group deals with that in their own way and it varies between the groups. Please see the reference material enclosed. | ||||

| 2 | Kakunodate Matsuri no Yama Gyōji | Both men and women can participate in pulling the festival floats [hikiyama], but only men can be festival officers (supervisor, deputy supervisor, traffic negotiator). | - Festival officers → limited to only men. - Teodori [hand dance] → women shoulder [this task] (especially young women under the age of 30) (the youngest start learning from around the age of 3). - Both men and women—it is irrelevant—can participate in pulling the festival floats [hikiyama]. | The musicians were only men in the old days. Women did teodori [hand dance]. Now, women who can do both teodori and be musicians have increased. Teodori dancers and musicians have different ‘kumi’ [teams], with team leaders. In some cases, the teodori dancers and the musicians can have the same team leader and in other cases they are different. | A few years ago (about 5 to 10 years ago). | The local children are learning how to play the music and dance the teodori, but it was decided that the date of the festival is 7–9 September, meaning that in some cases the festival is held on weekdays, with a shortage of people. |

| 4 | Hanawa Matsuri no Yatai Gyouji | Nothing in particular. | It’s not a written rule but, - Operations (Commands, instructions) → men. - Dancing → women. | None. | ||

| 5 | Shinjō Matsuri no Yatai Gyōji | - Shamisen is [played by] mostly women. - Steering the pulling of the festival floats is [done by] mostly men. | None. | None. | ||

| 6 | Hitachi Furyūmono | Out of the 4 branches, 1 branch admits women to participate in narimono (a music instrument performance) only. | See previous. Concerning hikiyama (moving the festival float around by pulling the ropes), ordinary visitors coming to view the festival are admitted to participate. | Before, all 4 branches didn’t admit women’s participation, but now 1 branch admits participation. | Approximately 20 years ago. | Shortage of people, and a change in consciousness towards female participation |

| 10 | Kawagoe Hikawa Matsuri no Dashi Gyōji | In the case of Kawagoe, the circumstances of the role divisions between men and women vary completely between the different districts. The preservation association does not have a clear picture. (The same goes for the following questions.) | ||||

| 12 | Takaoka Mikurumayama Matsuri no Mikurumayama Gyōji | Concerning the festival itself, women don’t participate in the operations or the management. Women’s assignment is to manufacture parts for the floats. The hanagasa [‘flower parasols’] of the Takaoka Mikurumayama are produced by men and women together. Women only participate in the preparation stages before the festival. | Concerning the buei [procession], everything is limited to men. The approximately 10 people in formal dress doing the role of attendant/companion are men, and the role of bodyguard/escort sitting on the float, done by kids, is limited to men. | Presently it’s limited to men but in the future, there is a possibility women might be accepted for the role children do as bodyguards/escorts sitting on the float. This is because the number of boys has declined considerably recently. That being said, it will probably not change for at least 10 years. | ||

| 13 | Uozu no Tatemon Gyōji | Traditionally, earlier it was a men’s festival. However, because of the progression of declining birth rates and population ageing, about 20 years ago (approximately) women started participating as musicians playing flute and drums. That elementary school students, regardless of sex, learned [flute and drums] in school also had an influence. | - Carriers and handlers of the ropes to secure the stability: men. - Flute and drums: men and women. - People pulling the ropes of the festival float: women are in majority (because of a shortage of people, since men are concerned with the roles described above). - Preparing tea etc, people behind the scenes: women. | See previous answers. | See previous answers. | See previous answers. |

| 14 | Jōhana Shinmeigūsai no Hikiyama Gyōji | 100% men. Each district decides the roles. | Entirely limited to men. | |||

| 15 | Seihakusai no Hikiyama Gyōji | - There are 3 festival floats. - Preservation association (in every neighbourhood/town there is a representative, vice representative, accountant etc.) - Wakai shu [Young lads/people] (Head of the young lads/people, work song singers, handlers of the levers, handlers of the stop levers, handlers of rope, etc.) | - Pulling the floats are for both men and women and open to the public to participate. - I believe it is safe to say that the area closest to the festival float is restricted to only men. - Among the 3 floats, concerning the pulling of the ropes of the floats, there are 2 women’s groups. | See previous answer but, among the 3 floats, there are 2 neighbourhoods/towns with women’s groups. | For the 2 neighbourhoods/towns it was around 1999 and 2001, I believe. | For example, a shortage of people caused by depopulation and population ageing etc. was [also] happening, but, to liven up the festival and to let girls participate even a little was [also] a purpose. |

| 17 | Furukawa Matsuri no Okoshidaiko Yatai Gyōji | None. | None. | Previously, women couldn’t even get close to the festival floats. Now, elementary school and junior high school girls are participating as musicians, and also women participate in pulling the ropes of the festival float. | Around 1989. | Shortage of people. |

| 18 | Ōgaki Matsuri no Yama Gyōji | In general, men shoulder many tasks. | It’s not a rule but, it’s a tacit understanding that women are not involved in religious matters. | Earlier, women were not allowed to touch the sanryōyama [three particular festival floats]. | After the war approximately. | Unknown. |

| 20 | Chiryū no Dashi Bunraku to Karakuri | Nothing in particular. | Nothing in particular (However, women are not involved in handling the kajibō [the poles used to manoeuvre and turn the festival float]). | Nothing in particular. | ||

| 21 | Inuyama Matsuri no Yama Gyōji | - The role pulling the festival floats (called ‘teko’ in Inuyama) is impossible for other than men. 20–25 people. - There are 10–15 musicians. Among them, the small drum group consists of 6–8 children, about half of them girls. There are 6–8 mothers as caretakers of the children of the small drum group. - The other various roles are performed by 10–15 men from the neighbourhood. - 5–8 people handle the karakuri [mechanical dolls and devices], all men. | In principle, there are no gender based divisions but, considerable strength is required for pulling the festival float, so presently they are all men. | For a long time, it was nyonin kinsei [prohibited for women], but the preservation association lifted the ban formally. | 1997 (Heisei year 9). | That it got hard to secure children for the small drum group because of the declining birth rates was one factor, but it doesn’t make sense to ostracize women from religious matters such as festivals in the first place, and also, as a result of many discussions in the preservation association, we concluded that the custom to abhor women is no more than a convention. |

| 22 | Kamezaki Shiohi Matsuri no Dashi Gyōji | Nyonin kinsei [prohibited for women]. | Nyonin kinsei [prohibited for women]. | |||

| 23 | Sunari Matsuri no Danjiribune Gyōji to Miyoshi Nagashi | - In the Sunari festival about 60 people board the boats, all of them men. - The music on the boat is performed by 4 out of 6 pages/children/ boys and 3 flute players. The pages are boys from 3 years old to 6th year of elementary school. 2 boys between 4th and 6th year of elementary school play big drums and small drums, and 2 boys between 5 to 7 years old play tsuzumi [drums] using drumsticks. The pages are accompanied by 4–8 people. - Apart from the above, on the boats there are also around 6 wakashu [youths/lads] (20 years old men), 3 matsuri sanyaku [leader role] and 4 boatmen, and people in charge of the paper lanterns. | - Since it’s an old custom it’s been conducted by only men. - Ever since it became possible to loan the festival costumes, women have helped with dressing, but so far no women have participated in the actual festival. (Not counting the miko [shrine maidens] at the shrine and the miko daiko [drum performance]. | For reasons connected to the declining birth rate, in case there are no boys available to consider for the role of page, discussions have developed on approving also girls, but [since] the [age range of the] children to consider for the role has been extended to elementary/primary school, no girls have participated. | About 15 years ago. | |

| 30 | Tobata Gion Ōyamagasa Gyōji | Generally, women can’t participate in the festival. | ||||

| 31 | Karatsu Kunchi no Hikiyama Gyōji | Since there are ‘0′ women, there are no role divisions. | It varies between the neighbourhoods, but some neighbourhoods admit elementary school girl to participate. | In all neighbourhoods, the number of people pulling the floats have grown, so before adult women are involved in an accident or similar, their participation has been prohibited. | Latter Showa period. | In all neighbourhoods there are many people pulling the floats, so contrarily the restrictions are getting stricter. |

| 32 | Yatsushiro Myōkensai no Shinkō Gyōji | About 1700 people participate in the Shinkō procession. The sex ratio varies between the festival floats but in general a large proportion are men. Many women participate as so called caretakers or helpers, as persons behind the scenes. | Around 40 festival floats participate in the Shinkō procession but, among them, regarding the ‘Yakko’, only men are allowed. Afraid that the transmission of techniques might leak to the outside, in the neighbourhood dedicated to Yakko, previously only the eldest son was allowed to participate but, due to the impact of declining birth-rates etc. it has become hard to transmit [the techniques] if only inherited by the oldest son so, it has opened up to people other than the oldest son. | There has been no particular change to gender roles. | ||

| 33 | Hita Gion no Hikiyama Gyōji | 100% men. | 100% men. | None. | None. | None. |

| 34 | Ōtsu Matsuri | There is no particular division of roles based on gender. On an individual level, the woman of the family often handles costume matters. | In all the festival floats, the guards, musicians, and float builders are men only. | The recruitment of people to pull the festival floats used to be done from the neighbourhoods, but now there are volunteers. From some years ago, one division become open for the participation of women. However, pulling the floats requires strength, so we are trying to decrease the ratio of women of as much as possible. Now the ratio is about 10%. | Tens of years ago. | Due to the enthusiastic requests of some people, the director in charge of the volunteers pulling the festival floats (Hikiyama federation) at the time lost, and after starting admitting [volunteers] it became not possible to refuse women. |

| 35 | Hitachi Ōtsu no Ofunematsuri | Only men. | ||||

| 36 | Murakami Matsuri no Yatai Gyōji | Women riding the festival floats (musicians). From the forties of the Showa era, it became ok for women (elementary school students) to ride the festival floats. | From the forties of the Showa era. | Declining birth rate. | ||

References

- Ueki, Y. Yama Hoko Yatai No Matsuri: Furyūmono No Kaika; Hakusuisha: Tokyo, Japan, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, M. Yama Hoko Yatai Gyōji no Hozon to Katsuyō. Gekkan Bunkazai 2017, 4, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, R.J. The Tyranny of the Normal and the Importance of Being Liminal. In Gender and Heritage: Performance, Place and Politics; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Heritage, Gender and Identity. In The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Ashgate Publishing Limited: Aldershot, UK, 2008; pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. Seven Years of Implementing UNESCO’s 2003 Intangible Heritage Convention—Honeymoon Period or the “Seven-Year Itch”? Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2014, 21, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, J. International Cultural Heritage Law; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Internal Oversight Service Evaluation of UNESCO’s Standard-Setting Work of the Culture Sector: Part I—2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Internal Oversight Service, Evaluation Section; Final Report; IOS/EVS/PI/129 REV; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam, V.; Bagheritari, M. Cultures, Conventions, and the Human Rights of Women: Examining the Convention for Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage, and the Declaration on Cultural Diversity. Mus. Int. 2007, 59, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Gender Equality, Heritage and Creativity; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, M. Nyonin Kinsei; Yoshikawa Kobunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wakita, H. Chūsei Kyōto to Gion Matsuri: Ekijin to Toshi no Seikatsu; Yoshikawa Kobunkan: Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brumann, C. Tradition, Democracy and the Townscape of Kyoto: Claiming a Right to the Past; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roemer, M.K. Ritual Participation and Social Support in a Major Japanese Festival. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2007, 46, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomination File for the Inscription of ‘Yama, Hoko, Yatai, Float Festivals in Japan’ on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. 2016, File No. 01059. Accessible through the UNESCO ICH Website. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists (accessed on 1 May 2019).

- Morinaga, C.; Doi, M. A Study on Difference of Cognitive Structure of Male Members and Female Members about “Hakata Gion Yamakasa”. Bull. Kyushu Women’s Univ. 2016, 53, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).