1. The Gavdos Project and the Bronze Age Building at Katalymata

Gavdos is the largest and most remote of the isles that surround Crete (

Figure 1a,b). Together with its neighbouring islet of Gavdopoula, it lies 36 and 22 nautical miles south of Paleochora and Chora Sfakion respectively, and is only 160 nautical miles north of the African coast. This apparently isolated dot of land in the Libyan Sea nevertheless holds a strategic position on age-old Mediterranean routes which connect the island to Crete and, apparently, to much more distant places. Its fragile small-insular environment is very individual, with rough and dry terrain, but it also has green, and at times even wooded, landscapes [

1] (pp. 70–73). Extensive sand dunes are combined with cedars and pine trees, especially on its northern part, while the entire western coast is comprised of a very steep cliff. The often much eroded interior is wrinkled with dried up gorges and includes numerous rock-shelters. Today, the island has approximately 50 permanent inhabitants but hosts hundreds of visitors in the summer months, most of them campers on its beaches [

2].

Hardly touched by modern development, Gavdos’s natural and man-made features shape an ideal “laboratory” for archaeological, viz. interdisciplinary, research [

3]. This has encouraged a series of activities conducted since the early 1990s by the Department of History and Archaeology of the University of Crete and coordinated by K. Kopaka, which were rather innovative for their time [

4,

5]. More specifically, these include:

An intensive archaeological survey (1992–2000, in collaboration with the Chania Ephorate of Antiquities) that revealed dense surface distributions of architectural remains and artefacts: Gavdos’s first archaeological map was its result. This illustrates a human presence from early in the Paleolithic [

6], through the Neolithic and Bronze Ages to the Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Venetian and Ottoman periods, and down to contemporary times [

7,

8,

9,

10].

A multi-disciplinary project (1993–1997) that brought together biologists, geologists, geographers and social anthropologists who studied Gavdos’s natural and cultural history. This is when the University’s field station was also created in a restored traditional farmstead (metochi), inland, at the site called Siopata on the Tsirmiris hill.

A training excavation (since 2003), in the wider region of the University’s field station. This is focused on a large architectural complex (of about 1400 sq.m.) of the Bronze Age at the site of Katalymata (

Figure 2) [

5] (pp. 64–66), [

11]. This building covers two successive terraces, has several rooms and some open spaces. It was occupied for a rather extended chronological sequence, and was apparently destroyed by an earthquake and fire in the mid-2nd millennium BC (i.e., the end of the Late Minoan IB period in Crete).

The character, quantity and quality of the finds at Katalymata (namely, abundant pottery and several stone vases, plenty of grinding and pounding tools, a number of metal finds, and beads and a couple of seals, along with good quantities of plant and animal remains, etc.) show manifold activities such as storing, food-preparing, cooking and consuming, but also important industrial work apparently related to the processing of grain (and grapes?) and maybe of raw materials such as clay, stone and metal. They also reveal a significant degree of ease and comfort enjoyed by the building’s residents, and indeed by the whole island, which agrees with the prosperity of contemporary palatial Crete [

5] (p. 66)—in fact, Katalymata can be compared to a Minoan “rural villa” [

12].

Because our whole research has a deeply educational character, most of the tasks, from the fieldwork to the study and even the publication of the finds, are taken on by both undergraduate and post-graduate students, who gain experience, with the help of the team’s senior archaeologists, both on conducting research and sharing life with their excavation group and the islanders. Building and maintaining relations of mutual respect with the Gavdiots, and encouraging their visits to our dig and friendly discussions on our finds, have been of priority to us (

Figure 3). The islanders thus provide steady and generous moral support to our project and entrust to us, especially to our social anthropologist G. Nikolakakis, their memories and their “natives’ point of view” (cf. [

13]). Some follow our fieldwork with particular interest, and their remarks and overall knowledge provide precious [ethnoarchaeological] clues to our decoding of ancient and modern findings from the island.

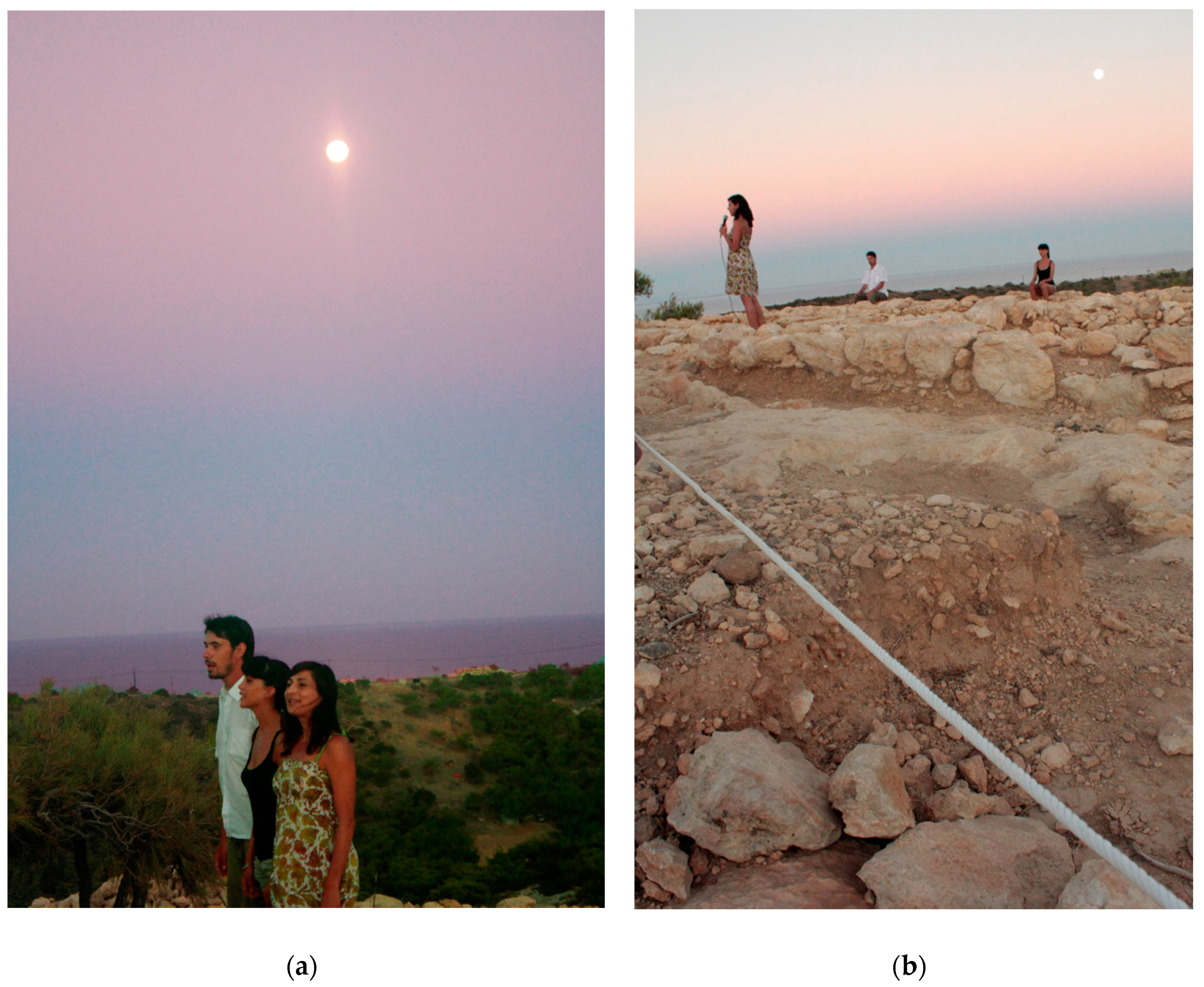

In our effort to further engage with both the local community and the summer visitors, E. Theou, who is a prehistorian and long-term partner of the archaeological project, but also an actor, conceived and staged the theatre/archaeology performance [

14] entitled ‘Gavdos: The House’ [

15]. This was first presented inside the Bronze Age building at Katalymata during the 2012 excavation

season—at twilight, against the backdrop of the rising full moon of August.

This endeavor responds to recent insights that “hybrid” practices in-between art, archaeology and ethnography can provide, among other things, tools for the most efficient dissemination of archaeological knowledge and insightful engagement with the material past, as suggested in the inspiring works by M. Pearson and M. Shanks [

14], D. Gheorghiu, [

16] and others. Two similar interdisciplinary projects by Theou held in Greece are those at the sanctuary of Poseidon on the island of Poros (“Kalaureia”, 2009) and at the Neolithic tell of Koutroulou Magoula in Thessaly (“The Meal”, 2011)—[

17], [

18] (p. 127), and [

19] (51–53).

2. The Creation of the Performance

There is nothing new in hosting an artistic event in an archaeological site. From the beginning of the 20th century, Greek tragedies and other theatrical pieces have been presented in ancient theatres. In the last decade, the archaeological community has proven to be most willing to encourage the public to engage with historical heritage monuments, e.g., by inviting people to musical concerts and other events held in them [

20] (pp. 66, 102–111), while excavation material has frequently inspired works of art [

21,

22,

23]. What is different in our performance at and for Katalymata is the extremely close relationship of its creative process with archaeological practice and research. In fact, by following the standard archaeological methodology (study of the relevant literature, fieldwork, and study of the finds), we have tried to explore how it could contribute to shaping a theatrical play, in the anthropological/ethnoarchaeological perspective of our research.

The “construction” of our performance took almost two years. It was the fruit of the collaboration of six actors/performance makers, three of whom are also archaeologists—(post)graduates of the University of Crete and members of the Gavdos excavation team. It all began in the summer of 2010, when a month was spent on the island to collect archival material through the interviews of a number of inhabitants, visitors, and archaeologists and other researchers of the multi-disciplinary project. We focused on their ties with the place and its antiquities, as well as on local (and more remote) memories of houses and attitudes to living in them. Our aim was to engage the extended Gavdiot community with this artistic project, and build a primary narrative on which our script would be based. We also conducted our everyday rehearsals in public spaces, where everyone was free to watch [

24,

25]. The artists participated, moreover, in the fieldwork at Katalymata, to experience the digging process and become familiar with the content of their scenic narrations to come. They even provided fresh insights and triggered interesting discussions, e.g., on the importance of integrating volunteers in excavation programmes [

26] (pp. 136–139), [

27,

28,

29].

Much time was spent, later, in studying the literature on both Gavdos and its tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and the meanings and connotations of the concept of ‘house’ through the lenses of archaeology, art and architecture, sociology and philosophy. Our approach to the archaeological space is mainly in line with Gaston Bachelard’s phenomenology of the dwelling—according to which, for example, the corners of a house function as a cradle and a nest for its inhabitants and their poetic daydreaming and creativity [

30]. Similarly, we believe, an excavation site is “inhabited” by its excavators (and their actions) who are shaping and suggesting narratives for the past following the material evidence that they uncover, but who are also drawing upon their own/personal embodied and cognitive experiences. This insight meets Tim Ingold’s suggestion that although native dwellers and archaeologists engage in different ways with the landscape, as do the stories they tell, “nevertheless, insofar as both seek the past in the landscape, they are engaged in projects of fundamentally the same kind”. To him, as to us, “the practice of archaeology is itself a form of dwelling” [

31] (189–190).

All this oral and written information provided the material for our dramaturgy and script. The method used was that of the ‘devised theatre’, where the different parts of the final piece are not produced by individual artists, but are the collective creation of a whole team [

32,

33].

The last round of rehearsals and the premiere were realised with the important contribution of the archaeologists, who prepared the excavated site, acted as a test audience, received and guided the spectators (

Figure 4), etc. Printed posters, announcements on Radio Gavdos and on social media platforms, together with a number of wider press releases and interviews, which included information on the ancient finds, informed the audience about the upcoming event [

34,

35,

36].

3. The Performance

Immediate preparations included an overnight stay at Katalymata for the actors and some of the archaeologists, for a deeper engagement with the site and its natural and spatial components. In the morning before the play, Gavdiots and visitors were invited to assist to our work on the field—in accordance with the welcoming general attitude adopted by our team, and as an antidote to the all-too-frequent perception of excavation sites as non-accessible, secluded spaces. Visitors were guided by team members who also explained different aspects and stages of the archaeological “performance” to them—also to recall Tilley’s observation that “excavation has a unique role to play as a theatre where people may be able to produce their own pasts, pasts which are meaningful to them …” [

37] (p. 280).

The premiere of the theatrical play took place in the late afternoon of the same day, as was dictated by the full moon which indeed provided an ideal setting, but also light in a place that still lacks electricity. Some 200 people attended this final event (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). They either sat on the natural bedrock or were free to move and watch the actors from different angles. The sloping hillside allowed a good view of both the excavated building and the splendid natural landscape down to the sea (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6a,b).

For one hour, the three performers moved in and out of the ancient building, sharing stories, experiences, and ideas drawn from the excavation since 2005, ethnographic interviews and philosophical and literary citations about houses and diachronic dwelling habits—on the island and beyond. They explored the musical qualities of the spoken word, varying from prose to rhythmical speech and singing. The dramaturgy was organized in four cycles that dealt with: the construction of a house, everyday routine at home, dwelling as a security zone, and the destruction of a house.

Our performance (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6a,b) did not aim to transport the audience to the prehistoric period. The narration was structured through a multileveled and diachronic perspective and focused on the multi-temporality of the archaeological

topos: in antiquity, certainly, but also in modern times, on into the 20th century, and up to the very excavation event, and the evening of the happening itself [

17] (pp. 191–193). The locals witnessed live artistic reflections of their home lives and household experiences—and in their own words, as they had shared them in their interviews with us—and saw how old many of these practices are in the light of our Bronze Age finds on the island: for example, on hearing of the long lasting use of rock-shelters for storage, or of the diachronic character of their [painful] encounters with the numerous Gavdiot scorpions, as shown by the depiction of one on a sealing on the rim of a prehistoric clay basin.

Nor did we tell a linear story or evoke a continuous sequence of facts. The script was highly fragmented into short, stand-alone passages which dealt with: a. theoretic, material and cultural aspects of house structures, domestic activities, and habitation habits, b. scientific archaeological and other information cited from the excavation notebooks of 2005–2012, and c. native memories of traditional life instances ‘at home’ on the island, as recorded in the interviews with its inhabitants. This disjointed scenic language was chosen as the most efficient way to express and communicate properly the character of the archaeological knowledge: where the past is revealed through small, if not tiny, and definitely fragmentary pieces of evidence.

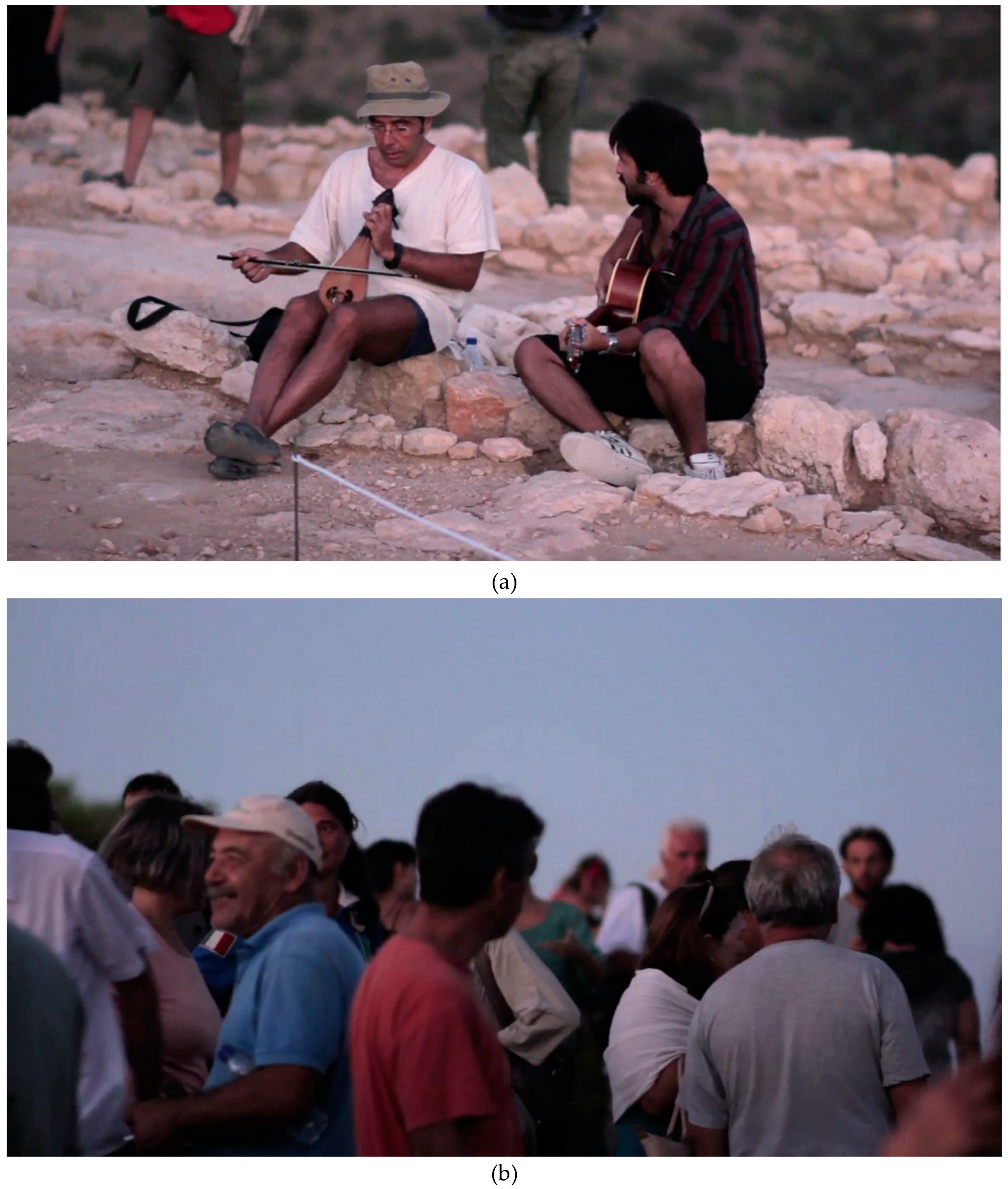

In the small feast which followed the performance, wine was offered, and music was played (

Figure 7a,b), in agreement with local customsof social gathering, as still somewhat reflected in the modern festival and celebration of Ai Giannis (Agios Ioannis/Saint John) on the 29th of August. Thus, participants did not experience, we trust, our event as a “foreign body”, the individualistic expression of a particular off-island group of people. They experienced it much more as a cultural construction organically integrated into island life and focused on the re-animated ancient monument at Katalymata and its archaeological exploration—and definitely not on a fenced-off/confined domain vaguely named ‘cultural heritage’.

4. Aftermath and Diffusion

The performance indeed left a strong impression on both the locals and foreigners, and brought many purposeful visitors to the excavation in the same year, as well as later. Many returned to the site in August 2018, when ‘Gavdos: The House’ was repeated at Katalymata, this time in the framework of the European Year of Cultural Heritage [

38]. Some of them even noticed, to our surprise, the changes we had made to the original script, which was inevitable given that the excavated site itself had changed a lot in the six intermediary years.

Since its premiere, this work has been touring in Greece and elsewhere in Europe, as an independent theatrical piece, but also as an alternative, embodied narrative of both the excavation at Katalymata and the whole island of Gavdos. Each time, the performance is of course adapted to be compatible with different scenic forms and media, in our continuing efforts to explore how such a project can function even outside the archaeological space which inspired it, and how it can develop as the future unfolds. Thus,

It has been presented at historic houses and other lived-in monuments, namely: in an abandoned apartment in the centre of Athens [

39]; in a house of refugees from the 1920s, the dormitory of Aristotle University, and an artist’s studio apartment in Thessaloniki (

Figure 8) [

40,

41]; as well as in a mansion of the 19th century Muslim community in Irakleio, Crete [

42]. In all these instances, the original performance was re-organised and adapted to the different rooms and spaces of each building, and to their functions and history: we used an analogy with those of the Bronze Age building at Katalymata, our first source of inspiration.

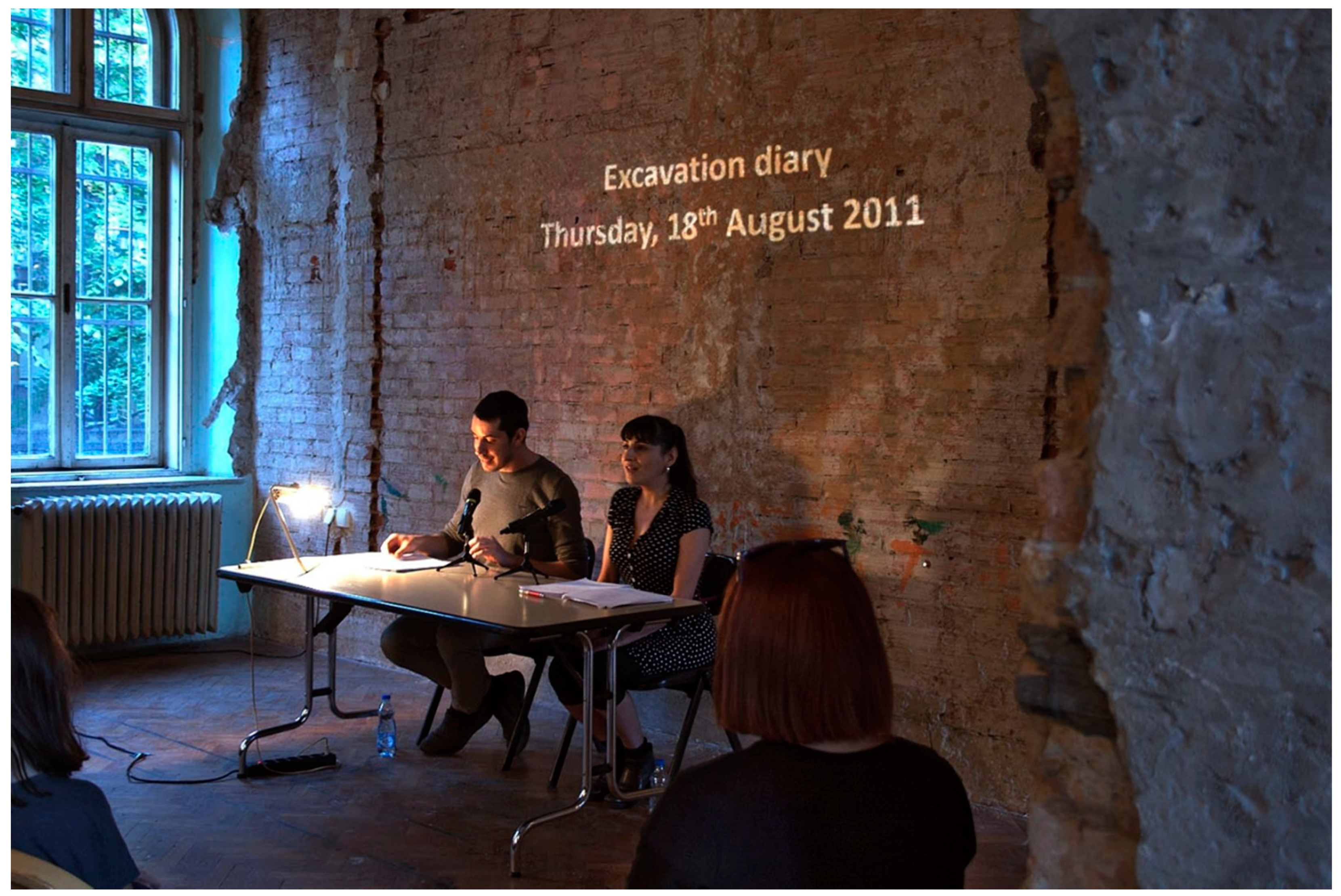

Invited by the Goethe Institute, The Temporary Academy of Arts and the

Actopolis—The Art of Action project, the work was presented as a lecture performance in Germany, Serbia and Greece (

Figure 9). In all these cases, the Gavdos excavation remains the key reference, but the script is enriched with new texts which permit to explore alternative modes of dwelling and contemporary urban living—the main theme of the

Actopolis project [

43,

44].

The video of the 2012 performance was displayed in the framework of three exhibitions of contemporary art, in Thessaloniki [

40] and Athens [

45,

46], together with documentation material—photographs, printed texts and archaeological drawings and reports, as well as audio tracks, which illustrated its birth, but also the methodology that we suggest when adopting such a “different” approach to the monuments and other ancient finds.

As a parallel event to the latter exhibition (Benaki Museum, October 2016), Theou organised the first round table in Greece on the interplay between archaeology and the performing arts [

46].

Finally, parts of the original script and the collected archival material were used by Theou, together with the artist Cristina Mejias, to create a series of visual installations which were presented in two other exhibitions, respectively in Madrid [

47,

48] and on the island of Tenerife (

Figure 10) [

49,

50]. This application shows the project’s potential to serve as a platform for diverse artistic creations.

5. Discussion

Modern archaeologists can no longer ignore local communities, nor continue to neglect the public’s perception of their work and acquired knowledge. This awareness has resulted in the development of new fields such as community archaeology [

51], archaeological ethnography [

52], and activist archaeology [

53]. Similarly, in order to redefine its role in society, contemporary theatre has escaped from the conventional stage to meet the audience and interact with it in non-conventional places within the public sphere, mainly in the framework of the so-called community theatre [

54], and site-specific theatre [

55]—here performances are hosted in culturally significant sites which are also used as sources of material for their narratives.

The conjunction of theatre with archaeology (and anthropology) that we are still developing on Gavdos employs the successful audience-engaging strategies of community site-specific theatre. It starts with the prehistoric site at Katalymata and is initiating various publics in the excavation process and the overall cultural sequence of the island. This melding and fusing is not—or is not only—making use of the tools of the theatre and its power to produce appealing spectacles, and hence tempting archaeological narrations too. We do not just seek a new multisensorial language for archaeology. Nor do we believe that history needs to become a spectacle to better “communicate” with people. Instead, we employ the theatre’s potential to create comprehensive collective experiences and trigger local creative abilities regarding the past and present. Indeed, on the evening of the performance, islanders, visitors and researchers met on the Tsirmiris hill, at the University’s excavation site at Katalymata, to take part as equals in a staged narrative, which had been rather evenly informed by all of them—and thus, they made the first step toward sharing the use of the archaeological space in a way that will be meaningful to the local community today and in the years to come, when the research will eventually have ceased.

Moreover, the suggested interplay of theatre and archaeology, these two major contributors to cultural creation, is far from being unilateral. The project that we are presenting here also explores the possibility of using excavation sites as artistic residencies, i.e., places where in-house artists can create and present relevant theatrical work, as well as other work. They would profit, thus, from both the vast existing networks of archaeological projects which often reach remote and/or neglected regions, and the archaeologists’ precious and usually interdisciplinary knowledge on local monuments, and would in turn provide their effective engagement and skillful sharing to the public.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, E.T.; methodology, E.T.; investigation, E.T.; supervision, K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T. and K.K.

Funding

Financial support of the Gavdos project is provided by the University of Crete. The 1996–99 study seasons were kindly supported by the Institute for Aegean Prehistory (INSTAP).

Acknowledgments

Warm thanks are due to: Elektra Angelopoulou and Anthi Efstratiadou who put both their talent and amazing work in this performance; Giorgos Nikolakakis, professor of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Crete; our colleagues Gerald Cadogan, Thanasis Deligiannis, Cristina Mejias, Panagiotis Katsolis, Philippa Karamolegkou, Marianna Tzani, Hong Rui Choo, Maria Ilvanidou, Thodoris Thomadakis and Christina Papoulia; and the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. Last but not least, we are grateful to the people of Gavdos who shared generously with us their memories and experiences—and inspired and made this whole work happen.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Grove, A.T.; Moody, J.; Rackham, O. Gavdhos, Crete. In Threatened Landscapes: Conserving Cultural Environments; Green, B., Vos, W., Eds.; Spon Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Andriotis, K. The ‘antinomian’ travel counterculture of Gavdos: An alternative mode of travelling. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 40–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.D. Islands as laboratories for the study of culture process. In The Explanation of Culture Change: Models in Prehistory; Renfrew, C., Ed.; Duckworth: London, UK, 2007; pp. 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Kopaka, K. Surface Survey on Gavdos. Approaches to an Insular Microcosm on the Edge. In Proceedings of the 8th International Cretological Congress, Irakleio, Greece, 9–14 September 1996; EKIM: Irakleio, Greece, 2001; Volume A1, pp. 62–80. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Kopaka, K. The Gavdos Project. An island culture on the Cretan and Aegean fringe. Eur. Archaeol. 2015, 46, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kopaka, K.; Matzanas, C. Palaeolithic industries from the island of Gavdos, near neighbour to Crete in Greece. Antiquity 2009, 83, 321. Available online: http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/kopaka321 (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Kopaka, K. From the life of a prehistoric word: ka-u-da and the products of the land of Gavdos. In SEMA, Volume in Honour of Menelaos Parlamas; Tzedaki Apostolaki, L., Ed.; EKIM: Irakleio, Greece, 2002; pp. 1–43. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Kopaka, K.; Papadaki, C. Prehistoric Pottery from Gavdos. The Case of a Small Island’s Industrial Production. In Proceedings of the 9th International Cretological Congress, Elounta, Greece, 1–6 October 2001; EKIM: Irakleio, Greece, 2006; Volume A1, pp. 63–78. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Kossyva, A.; Moschovi, G.; Yangaki, A. Surface Survey on Gavdos: Evidence for Roman and Early Byzantine Occupation. In Proceedings of the Creta Romana e Protobizantina, Atti Del Congresso Internazionale, Iraklion, Greece, 23–30 September 2000; Livadiotti, M., Simiakaki, I., Eds.; Bottega d’Erasmo: Padova, Italy, 2004; Volume 2, pp. 397–414. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Kopaka, K.; Theou, E. Gavdos or living on the southernmost Aegean island in the Neolithic cultural horizons. In Communities in Transition: The Circum-Aegean Area during the 5th and 4th Millennia BC; Dietz, S., Mavridis, F., Tankosić, Ž., Takaoglu, T., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 441–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kopaka, K.; Theou, E. Bronze Age pottery and other clay finds from Katalymata, Gavdos. In Proceedings of the Archaeological Work in Crete 4, Rethymno, Greece, 24–27 November 2016. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, P.P.; Marinatos, N. The Minoan Villa. In The Function of the ‘Minoan Villa’, Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium, Athens, Greece, 6–8 June 1992; Hägg, R., Ed.; Svenska Institutet i Athen: Stockholm, Sweden, 1997; pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. ‘From the native’s point of view’: On the nature of anthropological understanding. In ID, Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M.; Shanks, M. Theatre/Archaeology; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gavdos: The House.

Concept/Direction: Efthimis Theou; performance: Elektra Angelopoulou, Anthi Efstratiadou. Efthimis Theou; Assistance: Panagiotis Katsolis, Philippa Karamolegkou, Marianna Tzani; photographs: Christina Papoulia, Thodoris Thomadakis; video: Thodoris Thomadakis; graphic design: Hong Rui Choo. Premiere: Katalymata Bronze Age building complex, Gavdos Island, Greece. 2012. Available online: https://vimeo.com/130125018 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Gheorghiu, D. Artchaeology. A Sensorial Approach to the Materiality of the Past; UNArtre: Bucharest, Romania, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilakis, Y.; Theou, E. Enacted multi-temporality: The archaeological site as a shared, performative space. In Reclaiming Archaeology: Beyond the Tropes of Modernity; Ruibal, A.G., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Plantzos, D. Review of Yannis Hamilakis’s Archaeology and the Senses: Human Experience, Memory, and Affect; Alfredo Gonzàles-Ruibal (ed.), Reclaiming Archaeology: Beyond the Tropes of Modernity. Historein 2014, 14, 124–127. (In Greek) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demou, V. The Present of the Past at a Time of No Future: A Synergistic Art Archaeology of the Athenian Acropolis. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sofiadou, K. European Conscience and Greek Identity: The Reception of Ancient Drama in Greece Through Contemporary Foreign Productions (1980–2010). Ph.D. Dissertation, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece, 2015. (In Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, J.H., Jr.; Ehrenhard, J.E.; Finn, C.A. (Eds.) Ancient Muses: Archaeology and the Arts; The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, I.A.; Cochrane, A. (Eds.) Art and Archaeology: Collaborations, Conversations, Criticisms; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Momigliano, N.; Farnoux, A. (Eds.) Cretomania. Modern Desires for the Minoan Past; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rohd, M.; Towey, M. Open and roving rehearsals. In The Penelope Project: An Arts-Based Odyssey to Change Elder Care; Basting, A., Towey, M., Ellie, R., Eds.; University of Iowa Press: Iowa City, IA, USA, 2016; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Haapala, A. ‘Insider-other’: Spectator-Dancer Relationships Fostered Through Open Rehearsals. Ph.D. Dissertation, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colley, S. Uncovering Australia: Archaeology, Indigenous People and the Public; Allen & Unwin: Crow’s Nest, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.; Beale, A. Volunteers in archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology; Smith, C., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 7666–7669. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, N. Archaeology from below. Public Archaeol. 2000, 1, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.; Lelong, O.; Shearer, I. Local community groups and Aeolian archaeology: Shorewatch and the experience of the Shetland Community Archaeology Project. In Aeolian Archaeology: The Archaeology of Sand Landscapes in Scotland; (Scottish Archaeological Internet Report 48); Ashmore, P.J., Griffiths, D.W., Eds.; Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: Edinburgh,UK, 2011; pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, G. La Poétique de l’Espace; Presses Universitaires de France—PUF: Paris, France, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment. Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oddey, A. Devising Theatre: A Practical and Theoretical Handbook; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, D. A Practical Guide to Ensemble Devising; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Archaeological Performance on Gavdos! Available online: http://www.athinorama.gr/theatre/article.aspx?id=120640&seourl=arxaiologiki_performance_sti_gaudo! (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Greek).

- Gavdos. Museum of Nature and Culture. Available online: http://www.haniotika-nea.gr/105445-mouseio-tis-fusis-kai-tou-politismou/ (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Greek).

- A Performance-Archaeology Space. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/Performance.Archaeology (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Tilley, C. Excavation as theatre. Antiquity 1989, 63, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavdos. European Year of Cultural Heritage 2018. Available online: https://www.culture.gr/el/service/SitePages/view.aspx?iID=3524 (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Greek).

- MIRfestival 2012. Available online: http://www.mirfestival.gr/12/en/programme.html (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art 6. Efthimis Theou and Elektra Angelopoulou—Gavdos: The House. Available online: https://biennale6.thessalonikibiennale.gr/en/event/gavdos_to_spiti (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- The ‘House, as Imaginary Concept and Construction’ and the Performance That I Do Not Want to Forget. Available online: www.elculture.gr/blog/article/ένας-περίπατος-6η-μπιενάλε (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Greek).

- MonitorFest. Available online: http://monitorfest.gr (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Assmann, K.; Fitz, A.; Fritz, M. (Eds.) Actopolis: The Art of Action; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Metropoleis in Crisis. Available online: https://www.efsyn.gr/arthro/mitropoleis-se-krisi (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Greek).

- Fever of Antique. The Exhibition at the Association of Greek Archaeologists. Available online: http://avgi-anagnoseis.blogspot.com/2014/06/blog-post_2441.html (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Greek).

- Benaki Museum. [OUT]TOPIAS: Performance and Public/Outdoor Space. Available online: https://www.benaki.gr/index.php?option=com_events&view=event&type=&id=4737&lang=en (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Matadero Madrid. YEMA. Available online: http://www.mataderomadrid.org/ficha/9142/yema.html (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Cristina Mejias. For What Cannot Be Recovered Can at Least Be Reenacted. Available online: http://cristina-mejias.com/forwhatcannot/ (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes of Site. La Tierra Tiembla. Available online: https://teatenerife.es/index.php/exposicion/la-tierra-tiembla/164 (accessed on 22 January 2019). (In Spanish).

- Cristina Mejias. An Other History. Available online: http://cristina-mejias.com/anotherhistory/ (accessed on 22 January 2019).

- Marshall, Y. Community archaeology. In The Oxford Handbook of Archaeology; Gosden, C., Cunliffe, B., Joyce, R.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 1078–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilakis, Y.; Anagnostopoulos, A. What is archaeological ethnography? Public Archaeol. 2009, 8, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, S.; Clauss, L.R.; McGuire, R.H.; Welch, J.R. (Eds.) Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Van Erven, E. Community Theatre: Global Perspectives; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, M. Site-Specific Performance; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).