1. Introduction

This article explores local perceptions and attitudes of a small community in Greece on the island of Antikythera towards one of the main archaeological sites of the island known as the ‘Castle of Antikythera’. This site has been regarded by the excavations’ director and representatives of the local community as hugely important for tourism potential on the abandoned and declined island. Antikythera is located in the proximity of Crete and has been recognized by rapid depopulation and decline over the years partly due to its isolated location. In this paper, we focus on the perceptions and attitudes of the few permanent residents who inhabit the island as well as those who were born on the island but currently live elsewhere visiting Antikythera over the summer. We argue that these types of studies are critical for informing the future use of heritage places for sustainable development, especially in the context of tourism development.

Recent research manifests that public attitudes towards archaeological sites can range from emotions of supreme national pride to absolute indifference and negligence [

1,

2,

3,

4]. National and local pride is, to a great extent, projected to monuments of worldwide reputation often functioning as ‘national emblems’ [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11] whereas depreciation, indifference and negligence often emerge from antagonism between archaeologists and landowners whose properties are occasionally expropriated by the state in the name of protecting national heritage [

2]. In addition, as we will further stress, negation and indifference towards archaeological heritage can mirror the projection of feelings of negation and indifference placed by outsiders towards a specific place.

Despite the growing number of ethnographic studies on local perceptions of archaeological heritage in Greece in recent years [

12,

13,

14], the recurrent, underlying argument revolves around the role of heritage in shaping a sense of place. This article adopts a different approach by looking at how senses of place frame perceptions of the material culture of the past in order to acquire a more holistic approach to the reciprocal relationship of material culture with a sense of place. The investigation of the interplay between heritage and place on Antikythera was conducted through the adoption of an ethnographic approach that combined understandings of the archaeological values in association with the wider place.

We will argue that the ways (positive or negative) in which the local community discuss or sense the island of Antikythera are projected in how the archaeological ‘Castle’ is perceived. In detail, feelings of depreciation against the archaeological remains of the ‘Castle’ reflect similar feelings and views expressed by Antikytherians against their island. It is worth stressing though that negative feelings against the archaeological site, when they are expressed, refer mainly to official interpretations of the past that contradict local myths and stories around the site of the Castle. In the context of tourism development, we observe, that the general feeling of depreciation cultivates a ‘pessimistic’ attitude of locals claiming that this place is not ‘attractive’ enough for tourists. Involving the local communities in heritage projects may thus enable cultivating an optimistic attitude for tourism development that is socially and culturally sustainable.

The first set of data of this article stems from an ethnographic study carried out during two summer periods, in 2007 (during archaeological fieldwork with the University College London) and 2010, respectively, the latter period funded by the post-doctoral scheme of the Greek State Foundation Scholarship. Our conversations with the local communities took place in the two main taverns of the island, the beach and front yards of the houses. We intentionally did not use a voice recorder during our conversations. Our method of recording included keeping notes in the form of a diary at different breaks of the day. We also recorded our reflections at the end of each day on a voice recorder. Over the remaining years, we also collected supplementary material drawn from websites and videos uploaded by Antikytherians on YouTube.

2. The Island of Antikythera: History and Cultural Heritage

Antikythera is a small Greek island located half-way between the island of Kythera and Western Crete in the southwest Aegean [

15]. It is considered to be one of the smallest and most remote inhabited places in the insular Mediterranean [

16] (Bevan et al. 2007:32). The island belongs administratively to the region of Attica and the prefecture of Piraeus, despite its remote geographical location in relation to the Greek capital. Since the 2011 local government reform, Antikythera forms part of the municipality of Kythira (the latter being a much larger island at the south-eastern tip of the Peloponnese). According to the national census of 2011, Antikythera had 34 permanent residents constituting demographically one of the smallest communities in the country [

17] while most residents are aged over 65 [

18]. The vast majority of the island’s population is concentrated on the settlements of Potamos (River), which also serves as the main port and the administrative capital), Galaniana and Harhaliana. During the summer period, however, the population is estimated to reach around 300–400 with non-permanent residents of Antikytherian origin spending time on the island. Antikythera is usually accessible through two boat connections: One running a route from Piraeus to Kastelli-Kissamos in Crete and another from Gytheion and Neapoli in Laconia (Peloponnese) with both connections stopping at Kythira.

Despite the small size of the island, Antikythera is positioned on a key axis of maritime movement between the Peloponnese and Crete and between the eastern and central Mediterranean [

15]. Archaeological research has revealed the earliest human activity to span from the Late and Final Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age periods, from the 5th millennium to around 3000 BC [

15]. The island was known in ancient times as Aegila or Aegilia and historical evidence shows the importance of a fortified town occupied by a pirate community during the Hellenistic period (4th–1st Century BC) [

15].

After the Romans invaded this ‘pirate town’ in about 69–67 BC there appears to have been a significant decline in human activity until the formation of smaller communities in the Late Roman and Byzantine periods (ca. 5th–7th century AD) [

16,

19]. Antikythera was later occupied by Arab pirates and came under Venetian (early 13th–late 18th century) and the British rule (1815–1864) until its final inclusion to the modern state of Greece in 1864 [

20].

Antikythera has had a difficult modern history as both a place of exile and refuge/immigration. From the eighteenth to the nineteenth century several families from Crete (then under Ottoman occupation) fled to the island along with some fugitives from the Peloponnese during the Greek War of Independence (1821–1832) [

20]. During the British rule, Antikythera became a place of exile for revolutionaries from the Ionian Islands [

21] while in 1944, during the Second World War, the Nazi Germans deported the entire population to Crete [

20]. Finally, from the late 1940s until 1964, the island received several political exiles (affiliated mainly with left-wing ideologies). During this period many Antikytherians immigrated to other parts of Greece or abroad (mainly to the USA and Australia) but the diaspora population has maintained strong connections with Antikythera [

20]. As will be argued in this paper, the ‘dark’ and ‘negative’ history of being a place of exile in conjunction with the remoteness of the island has contributed significantly to the emergence of local beliefs that the island is inferior in comparison with surrounding islands (such as the one of Kythera).

Nevertheless, Antikythera has also received some global attention. The island became famous worldwide in 1901 after the discovery of the famous ‘Antikythera mechanism’, an astronomical device that dates back to 100 BC, which was recovered by Greek sponge-divers of a Roman shipwreck near the island [

22]. The finds of the shipwreck aroused the national and international interest towards Antikythera and subsequently several research projects have taken place [

23]. In recent years the Antikythera Survey Project, an interdisciplinary programme of the Trent University (Canada), the University College London and the 26th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities (EPCA) has provided very interesting insights to the long-term history and human ecology of the island [

24]. This is indeed an archaeological find mentioned regularly in our conversations with the community, and yet, they acknowledged that despite the international reputation of this object, the island is not a major tourist attraction pointing also that the object is currently displayed at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, instead of its original location (which might further attract more tourists).

Today, the Archaeological Service of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture is responsible for all cultural heritage-related activity on the island and therefore supervision and activity regarding antiquities belongs to its regional service of the Ephorate of Western Attica, Piraeus and the Islands (formerly 26th Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and 7th Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities). Apart from the main attraction of the island, the fortified town of Aegila or ‘Castle’ (presented in the following section), there are remains of an early Byzantine settlement near the village of Harhaliana, remains of five windmills and a watermill dating to the nineteenth century as well as a lighthouse built in 1926 [

20] (

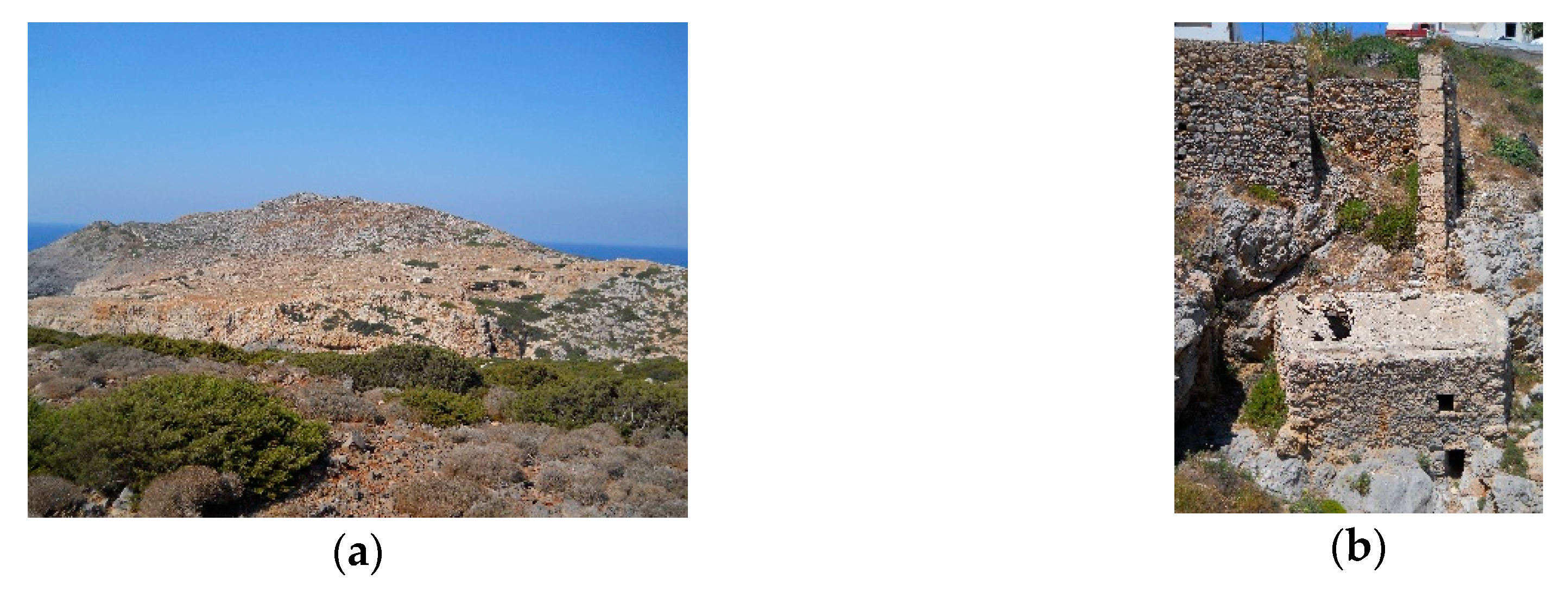

Figure 1).

3. Ancient Aegila: The ‘Castle’ of Antikythera

The most important archaeological site of Antikythera is a fortified Hellenistic settlement situated on the northern coast of the island, on the top of a hill overlooking the bay of Xeropotamos. The bay used to function as the naturally protected main harbour of the island in antiquity [

20]. The site, which covers approximately seven hectares (ca. 75 acres), has been known among the local community as the ‘Castle’ (Kastro) since the mid-nineteenth century [

25]. Archaeological investigations suggest a life-span from the late 4th to mid-1st century BC [

16,

26]. The archaeological excavations on the Castle have been taking place on an annual basis since 2000 under the supervision of Mr Aris Tsaravopoulos [

27,

28]—former responsible archaeologist of the Archaeological Service on the islands of Kythera and Antikythera. Overall, the excavations on the Castle have highlighted the significant role of Antikythera in maritime routes and interactions [

16]. This complies with the hypothesis that the island functioned as a pirate town under the control of Falasarna, a well-known city of pirates in Western Crete [

29].

The landscape of the Castle today is dominated by agricultural terraces formed predominantly by dry stone risers [

30,

31,

32]. Among the most interesting archaeological features are the multiple construction phases of the fortified city, a cemetery, the very well preserved remains of a rock-cut ship-shed, one of the few surviving in Greece [

26], and the remains of a sanctuary dedicated to the god Apollo which was discovered in 1889 in the innermost corner of the Xeropotamos bay [

26,

33].

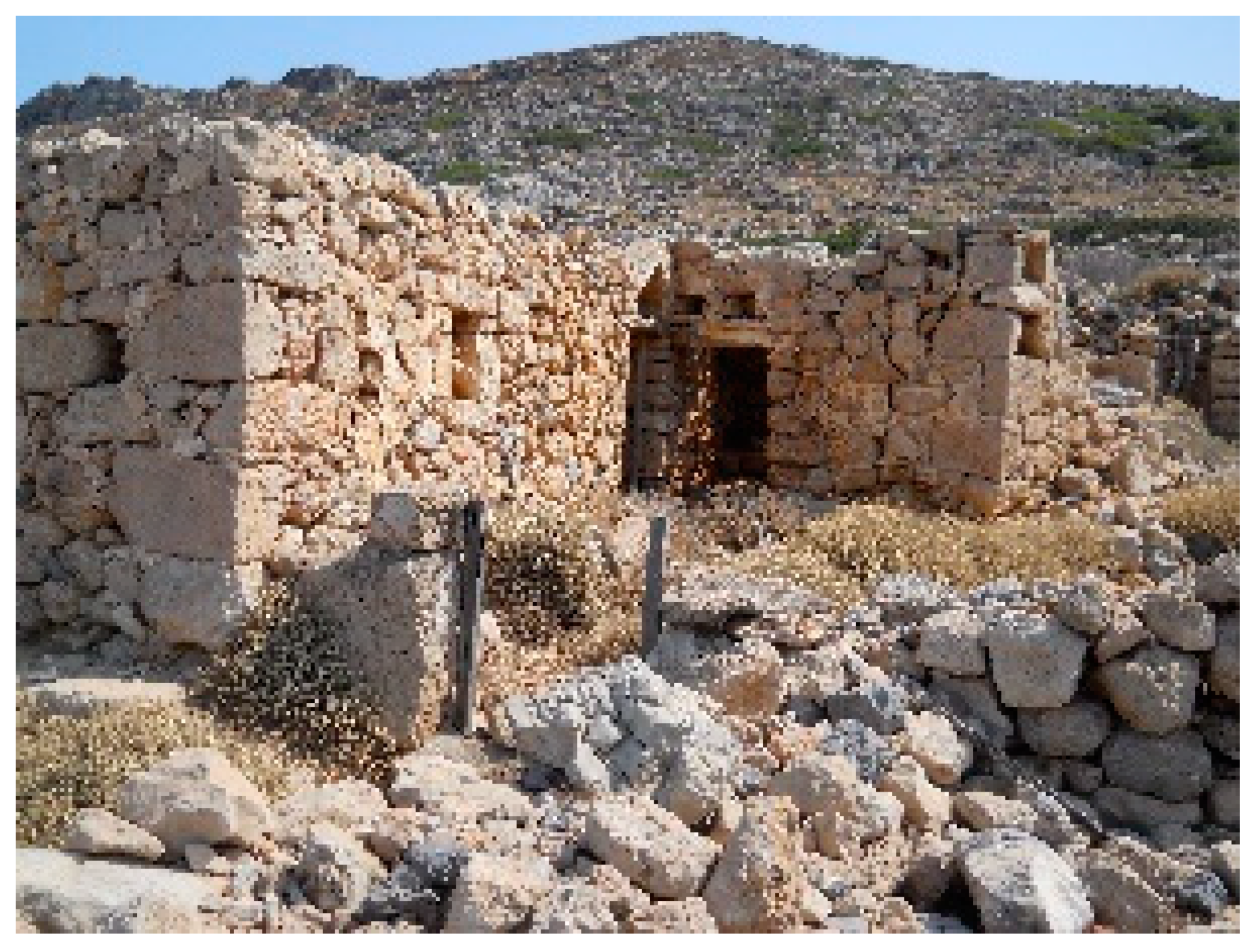

According to personal communications with local people, before the designation of the Castle area as an archaeological site (and therefore as a protected area) by the Greek state, the hill was inhabited until the 1980s by members of a local family (the Ploumidis family). The family also owned the land plot, which currently contains the remains of the sanctuary of Apollo. The remains of the family’s houses date to the 19th century [

34] and are still visible on the site (

Figure 2).

Archaeologist Aris Tsaravopoulos has suggested the rehabilitation of the houses under an alternative tourism scheme that would utilise volunteers from potential visitors to the island [

20,

26]. Furthermore, this rehabilitation is viewed as an opportunity to create a museum space for the exhibition of the moveable excavation finds [

34]. In other words, this alternative tourist scheme could attract tourists who have a special interest in participating in archaeological excavations for which they would pay a fee for their participation. It is worth pointing out here that this idea has not been materialised partly due to logistic issues related to the Ministry of Culture. In any case, an in-depth understanding of how local communities appropriate or not the site would also be invaluable in informing this future plan.

4. ‘Placing’ Heritage on Antikythera

The interplay between heritage and place has thoroughly been discussed in different fields including geography, cultural anthropology and cultural heritage studies. One of the recurrent arguments is that heritage constitutes a key determinant for the distinct character of places and that a place in itself is a heritage product [

35,

36,

37]. A strong interrelationship between senses of places and senses of time has also been identified. Ashworth and Graham [

35] (p. 4), for instance, state that the key linkage in the process of sensing time and place is heritage while Laurajane Smith [

38] has stressed that heritage must be understood as a process rather than as a ‘thing from the past’. During this process material artefacts, mythologies, memories and traditions [

35] are selected to become resources for the present. Interestingly, while great emphasis has been placed on the role of heritage as a medium in shaping places and related identities the reverse, i.e., the role of place as a medium in constructing heritage has been overlooked.

Before the analysis of the role of ‘place’ as a medium in heritage construction it is important to conceptualize the notion of ‘place’, as it is often used with multiple meanings. Indeed as Relph [

39] (p. 4) states ‘the confusion about the meaning of the notion of place’ is the result of ‘a naïve and variable expression of geographical experience’. The identification also of the ‘place’ with other similar notions, such as landscape or space, emerges from the evolution of the latter concepts. For example, the word ‘landscape’, when it was introduced into the English language during the late sixteenth century as a technical term used by painters [

40] (p. 2) was often imbued with the notion of aesthetics [

41]. Recent attempts to define landscape have shifted from the pure aesthetic connotations to include meanings assigned by local people to their cultural and physical surroundings [

40]. Consequently, there is ‘a landscape we initially see and a second landscape which is produced through local practice and which we come to recognize and understand through fieldwork and through ethnographic description and interpretation’ [

40] (p. 2). Accordingly, ‘the landscape entails a relationship between an ordinary, workaday life and an ideal, imagined existence, vaguely connected to but still separate from that of the everyday’ [

40] (p. 3). As a result, landscapes are viewed as ‘aggregate mixes of multiple material pasts’ [

42] (p. 196). These pasts constitute the ‘polychronic ensemble of landscape and have actions in people’s lives’ [

42].

Since the concept of ‘landscape’ has evolved from the traditional emphasis on aesthetics to include intangible meanings attached to places, it becomes difficult to isolate the concept of landscape from concepts such as ‘place and space, inside and outside, image and representation’ [

40]. As Hirsch [

40] (p. 4) affirms these concepts are related in that place, inside and image accords to what we would comprehend as the form of everyday while the space, outside and representation connote the ‘experience that extends beyond the everyday, the imagined, the potential’. In view of this, the landscape is not a thing but rather a cultural process [

40]. The notions of outsideness and insideness, place and space have been eloquently analysed by Relph in his seminal work entitled Place and Placelessness. According to the author, the more powerfully an environment generates a sense of belonging the more strongly does the environment become a place [

39]. Similarly, the more strongly a person feels alienated from a space, the more strongly does this space reinforce an experience of outsideness and an experience of division from the ‘world’ [

39]. It becomes apparent that place, space and landscape are not being treated as static, fixed entities but rather as dynamic, fluid processes. Definitions that have been given to those terms strongly interrelate and the boundaries are not distinct.

More significantly, when place and landscape are translated into other languages they acquire additional meanings. The equivalent Greek translations of these terms, for instance, would be topos (τόπος), choros (χώρος) and topio (τοπίο) respectively. Since ‘choros’ and ‘topio’ refer narrowly to a physical space and aesthetic scenery, it is the notion of topos that will be used in this article because this term contains particular ideological and symbolic connotations [

43]. Indeed, the word topos not only marks a physical place, a site where the past makes its presence felt [

43], but it also invokes the self-presence of Hellenism [

43] (p. 69). Therefore the notion of topos signifies both the real, physical topos and an imagined topos, a heteros topos (that means an ‘other place’) [

44]. The heteros topos constitutes a socially created space, which is often ‘obscured from view by excessive emphasis on their empirical opaqueness or their ideational transparency’ [

45]. A heterotopia is ‘conceived as being otherwise and existing outside normative social and political space’ [

43]. Thus, heterotopias can function as ‘countersites’ in which ‘the real sites … are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted’ [

44]. In retrospect, heterotopias are eventually more of an idea about space than any actual place [

46].

If we synthesize the above key elements of approaches to place, space, ‘topos’, the emerging analytical framework for understanding our findings on Antikythera comprises of the following interrelated dimensions: (a) Physical/material culture and natural elements that shape a sense of place (topos); (b) images, mythologies and stories that the ‘topos’ of Antikythera evoke among locals and ‘expatriated’ locals and (c) ways in which such images shape certain perceptions and ideas about the archaeological ‘Castle’, creating ‘heterotopias’ (imagined spaces). By doing so, we will then be able to draw the emerging possible implications of making the ‘Castle’ a site for tourist consumption.

5. Imagining and Sensing the Antikytherian Topos

As mentioned before, the island of Antikythera is a remote, rather inaccessible island, which, in contrast to the idealised image of a Greek island, lacks beautiful, sandy and easily accessible beaches as well as attractive flora and geological features. It was, thus, often described during our conversations with local residents as ‘xeroniso’ (dry island) or ‘agriotopos’ (wild topos). While the wilderness of Antikythera is perceived by the locals as a burden for tourism development, it is nevertheless being promoted on web media as a distinctive characteristic, which needs to be experienced by its visitors since it provides an authentic experience of an island that has not been appropriated by tourism. One of the municipality’s websites reads, for instance:

‘Antikythira fascinates visitors with its wild beauty. This small island is an oasis of tranquillity, an ideal destination for those who seek moments of absolute relaxation far away from big cities’.

The emphasis on the wild nature of the island is common among the language used by both the authorities of the municipality and the local community. However, on this (and other) websites this wilderness is intermixed with beauty and aesthetics while for locals, the island of Antikythera was viewed as a wild but not necessarily a beautiful island. Interestingly, there was often a comparison with the more ‘beautiful’ and ‘attractive’ island of Kythera, which lies close to Antikythera. The island of Kythera was often mentioned as an island with better landscapes, beaches and antiquities.

It becomes evident that wilderness is linked by local authorities with notions of beauty, authenticity and quietness. These notions have also occurred in similar studies beyond Greece. A study was carried out by Sandra Wall-Reinius in the Laponian World Heritage Area where the author investigated how the ‘wild’ Laponian landscape was viewed and experienced by tourists [

48] (Wall-Reinius 2012). It was revealed that notions of wilderness link with notions of quietness and peacefulness. To the question ‘‘To you, what characterizes a wilderness area?’, ‘untouched nature’, ‘silence’, ‘peace and quiet’ and ‘a feeling of being far away from civilization’ were found to be the most frequently used definitions or descriptions [

48].

Although, the afore-mentioned study focused on tourists rather than the local community, it is interesting to observe how the feeling of ‘being away from civilization’ reoccurs on Antikythera either in ironic local commentaries or as a positive and distinct attribute of the island on local promotion materials and tourist guides: ‘

In the middle of the sea, forgotten by gods and humans, inaccessible to common tourists, Antikythera constitutes the ‘Holy Grail’ of those seekers who are not satisfied with the usual excitements of the tamed landscapes’ [

49]. It is due to the peacefulness that the landscape of Antikythera elicits, that one of the youngest inhabitants of the island decided to move from a big city in Greece to Antikythera. As he stated: ‘I was attracted by the relaxed topos of Antikythera… when you know what you want, you discover it even

in these dead places’ (our emphasis). As above, this statement contains contradictory and mixed feelings, negative and positive. The ‘dead place’ of Antikythera becomes a place of tranquillity, peacefulness and quietness. The ‘wild’ landscape of Antikythera becomes beautiful scenery that is authentic, pure and unique. The ‘beautiful peacefulness’ that the wild landscape of Antikythera invokes is one of the main attributes that contribute to local pride. One of the local inhabitants, for instance, stressed that: ‘

I am proud of living on this rock, my ancestors moved in 1913 and they first lived in a cave, I was abroad but came back due to my love for this rock….’ (our emphasis).

There is thus a mixture of antithetical local emotions about the ‘topos’ of Antikythera. On the one hand, locals negated their surroundings and tended to develop discursive ironies about them. At the same time, however, they were permeated with feelings of pride and nostalgia of their topos as it used to be in the past. Their sense of the past was strongly crystallized by their senses of their topos as well as by the senses of ‘others’ for their topos. Antikytherians, for instance, claim that Kytherians view their island as inferior to Kythira, a popular tourist destination. Since the eighteenth and nineteenth century the island was also described by travellers as ‘uninhabited, naked and dry’ and [

50] ‘ugly and open to northern winds’. Ancient authors also claimed that the island ‘did not deserve much to say’ [

50]. Similarly, Valerios Stais, during his excavations on the island in 1888 wrote: ‘the construction of such fortification in this unimportant island which is highly unreferenced by ancient authors is rather strange to me’ [

33]. Hence, the island of Antikythera evokes images of the actual, current topos (what we see) and images of an imagined, heteros topos (what we would like to see or how we feel about what we see). Such mixed perceptions of the topos of Antikythera are clearly projected on the archaeological castle, as described below.

6. Sensing the Antikythera Castle

Interestingly, and possibly unsurprisingly, views related to the archaeological site differ among the local community. Although there are as many different perspectives as there are inhabitants, we were able to identify a distinction between the permanent residents of the island who have been or are involved in its governance; the permanent residents who live isolated in their settlements and those who have Antikytherian origin but live permanently in other places (mostly big cities). Conventionally, we will name the first group as the ‘official locals’ in that they represent and support ‘official’ archaeological narratives. The second group constructs ‘unofficial’ or ‘alternative’ archaeologies while the last group lies between the two aforementioned groups. For the local governors of the island the archaeological site forms a driving source for tourism development that will bring ‘the youth’ (as they often mentioned) back. For them, the actual topos signified by the archaeological remains of the ‘Castle’ is regarded as significant, and is valued for its tangible attributes of archaeological significance, integrity, uniqueness and monumentality. The excavator of the archaeological site, Mr Aris Tsaravopoulos, and his team were also perceived with great respect. The archaeological work was viewed as a great opportunity for boosting tourism and the local economy.

The second group, on the contrary, expressed less interest in the archaeological ‘ruins’ but a greater interest in the stories and tales associated with the wider area where the archaeological ‘Castle’ is located. The material culture associated with the site was mainly viewed as a ‘source of building material for their houses’ or a ‘source of potsherds for drying up their wells’. The actual, archaeological site was conceived as an alienated territory owned by archaeologists and, potentially, by tourists. Although they did not view the ‘owners’ of this territory with hostility, they were simply not interested in engaging with them. Furthermore, they often affirmed with inferiority the significance of the site arguing that the ‘proper castle’ is located on Kythera, which attracts more tourists. Their belief was that the archaeological remains on the site of Antikythera constitute ‘old stones’, which are ‘unimportant’. Hence, they had often reused stone materials in construction projects.

Despite the lack of interest of this particular group in the archaeological site, ‘alternative’ histories and stories were developed by this group in relation to the site. These stories clearly mirror the negative or dark aspects of the island’s history. An indicative example of local resistance to accept an ‘official’ archaeological interpretation is the so-called cave which was excavated by both Valerios Staes and Tsaravopoulos. This example, which proved to be a prehistoric tomb and a sanctuary, respectively, is known among the local community since the end of the nineteenth century as ‘prison’. For Antikytherians the ‘prison’ is a horrific place in which people in exile were kept and beaten. Back in 1888 it seems that the so-called ‘prison’ for exiled citizens used to function as a place housing children and women who fled from Crete during the uprisings against the Ottomans [

33]. This name may also echo the history of the island as a place of exile and prison during the English occupation (1815), the Greek Civil War (1945-1949) and the most recent military dictatorship (1967–1974). The archaeological interpretation of the cave as a sanctuary was not welcomed by the permanent residents despite the fact that the identification of the place as an ancient sanctuary provides a purified, peaceful and comforting version of the past. It becomes apparent that, while the residents acknowledge the territorial ownership of the material site by archaeologists they refuse to relinquish the ownership of the ‘imagined topos’ and its associated tales to the ‘official archaeologies’. Despite the ‘dark nature’ of the alternative stories, there is local resistance in replacing their story with comforting archaeological interpretations. Resistance to accept official archaeological interpretations indicates Ashworth’s and Graham’s [

35] argument that ‘the naming of places is both a necessary means of recognition and communication but also a fundamental means of laying claim to territory’.

The third group of ‘locals’, those who are Antikytherians by birth or by origin but do not live on the island, are more receptive of ‘official’ archaeological interpretations and willing to participate and find more about their archaeology. In our discussions, a sense of pride about the unique and rare ship-shed, the well-preserved and monumental fortification walls and the role of the island as a pirate city was apparent. This group focused on the materiality of the site and they also criticized the appropriation of the ‘Antikythera mechanism’ by the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. They view the shipwreck’s findings as their ‘local’ heritage, which is also of great touristic potential. Emotions of bitterness for a nostalgic past that is lost were also explicated in relation to modern monuments, such as the nineteenth century water mill, the remains of which are preserved in the area of Potamos.

What are then the implications of the findings for the future tourist development of the island? Our research shows that the archaeological site of the ‘Castle’ is viewed by the local authorities and the community as a potential tourist resource. As such, there is a desire for this resource to be utilized for tourist consumption. For those local residents who are not employed in the public services there are alternative forms of heritage that they would not like to share with the tourism community. This is indeed a recurrent behavioural pattern among local residents, at least in the context of Greece [

51]. ‘Official’ forms of heritage (such as archaeological monuments) are viewed by locals as acceptable forms of heritage accessible to tourism. However, forms of heritage with which local residents are connected on a personal or a community level are regarded by the community as belonging to themselves and, thus, they resist to share with external tourists.

7. Conclusions

This article argued that perceptions, attitudes and behaviours projected towards an archaeological site are interdependent with perceptions, attitudes and behaviours projected towards a particular place (‘topos’). We stressed that it is not only heritage which delineates a place, as has usually been emphasized in heritage literature, but also a place that forms, defines and shapes heritage. In other words, we aimed to unpack the dialectical, reciprocal relationship between heritage and place in greater depth by using the case of an isolated, declining and remote island. The case of the archaeological ‘castle’ on Antikythera, a remote island marked by a long-term negative history of isolation and exile, provided an indicative example that illustrates this interplay between place and heritage. Very few studies in rural areas exist that look at the interrelationship. Heritage is often linked with ‘beautiful’, ‘monumental’, ‘comfortable’ pasts. And yet, the case of Antikythera shows that a place marked with decline and negative histories, although may influence how its official heritage is viewed by locals and tourists, it also evokes positive memories and alternative forms of heritage that the locals keep for themselves.

While we acknowledge the potential diversity and uniqueness of the views held by each inhabitant on the island, we identified three main groups of opinions including: The permanent residents who are involved in the governance of the island; the permanent residents who are not involved in the governance of the island; and the temporary residents (of Antikytherian origin) who live in bigger cities and visit the island during the summer. All three groups have developed different and often contradictory perceptions and behaviours towards the ‘actual archaeological topos’, which is visually and physically signified by the archaeological remains, and the ‘heteros topos’ that is demarcated by the stories and the local names that have been given by the community. The ‘local governors’ shared feelings of appreciation and pride about the island and the archaeological site. The second group, which is not interested in tourism development through heritage or any other means, has constructed an ‘heteros topos’, which, although constitutes a projection of negative feelings about the actual topos, it is a topos that fosters a sense of belonging. This heteros topos is marked by local names, which function as territorial signifiers or symbols of belonging and ownership. The group of non-permanent Antikytherians have constructed an idealized heterotopia that relies on the nostalgic past of childhood. In this case, the ‘castle’ functions as a medium for reviving these heterotopias.

It thus becomes apparent that an archaeological site is potentially a dissonant topos. Its dissonance will most likely be exacerbated by the future ‘touristification’ of the island as a new community, that of the tourists will impose their own ideas and ways of experience the archaeological castle as a heteros topos. The castle is also a heteros topos, a socially constructed space, which can constitute both an imagined, positive heterotopia and a negative, imagined topos that is forcefully owned by the local community. For understanding and managing this dissonance, it is vital that perceptions of ‘topoi’ and ‘heterotopias’ associated with an archaeological site are investigated. Indeed, more research needs to be done on exploring how people identify or disassociate themselves with their place, and how such processes shape perceptions of archaeological sites especially when utilized for the economic development of declined areas. Current studies, especially by practitioners, do not contextualize perceptions of archaeological heritage within wider perceptions of the place on which archaeological remains are located. We believe that this approach will unfold ‘alternative’ archaeologies, histories and stories, which can be incorporated into the management of archaeological sites. It needs to be acknowledged though that the lead archaeologist has been conducting an ambitious and rather innovative approach for Greek archaeological standards, by not only inviting volunteers and conducting living tours on the site but also by holding a series of seminars and lectures open to the public related to the findings at the end of each excavation period. More work needs to be done towards this direction since archaeological sites can provide a space for dialogue, collaboration, creativity, sustainable development as well as a source for connection, pride, identity and belonging. This should be a collective, collaborative effort with local authorities, which can bridge archaeologists with local communities. In the context of tourism, participatory approaches to sustainable tourism development will benefit greatly by carrying out in-depth ethnographic studies such as the one proposed in this paper. This is because this type of studies can uncover what heritage elements local communities are willing to ‘share’ with tourists and which heritage they wish to retain for themselves. By doing so, in tourism development plans, local communities are not alienated; local cultures keep thriving; and local lifestyles and traditions continue to underpin the everyday lives of the local population.