Valorisation of Eggshell Waste for Effective Biosorption of Congo Red Dye from Wastewater

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eggshell Waste Biosorbent Preparation

2.2. ESW Characterisation

2.3. Model CR Solutions and Synthetic Wastewater Preparation

2.4. Batch Biosorption Experiments

2.5. Isotherm and Kinetic Modelling of Batch Biosorption Data

2.6. Desorption Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

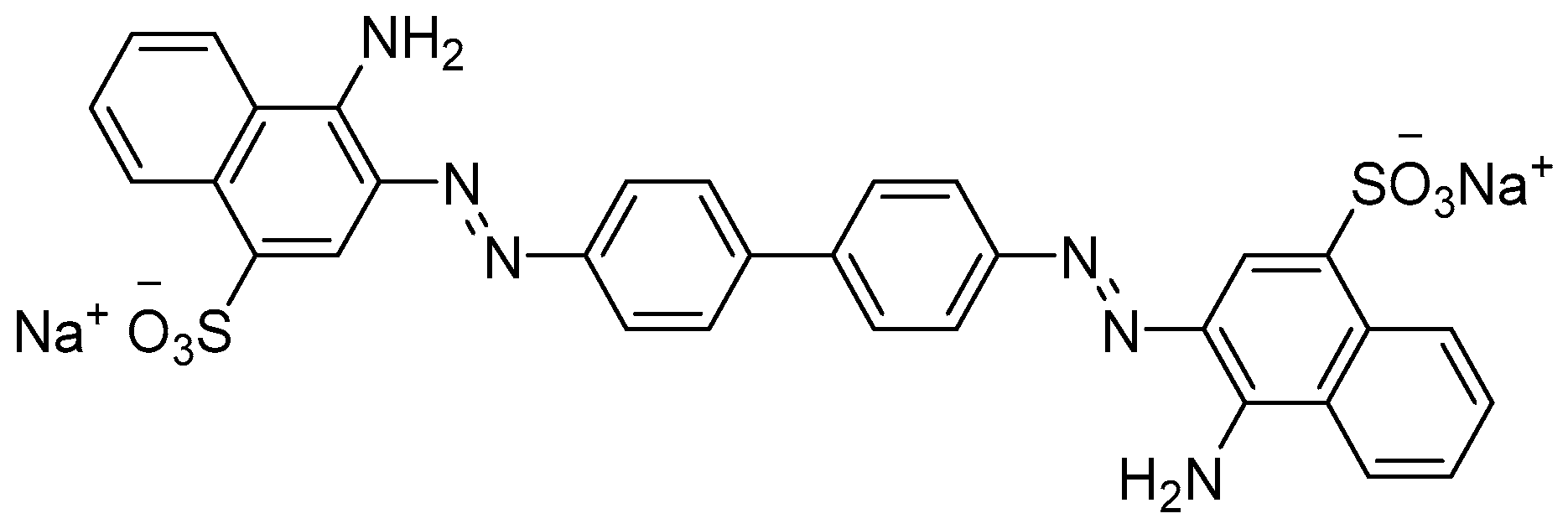

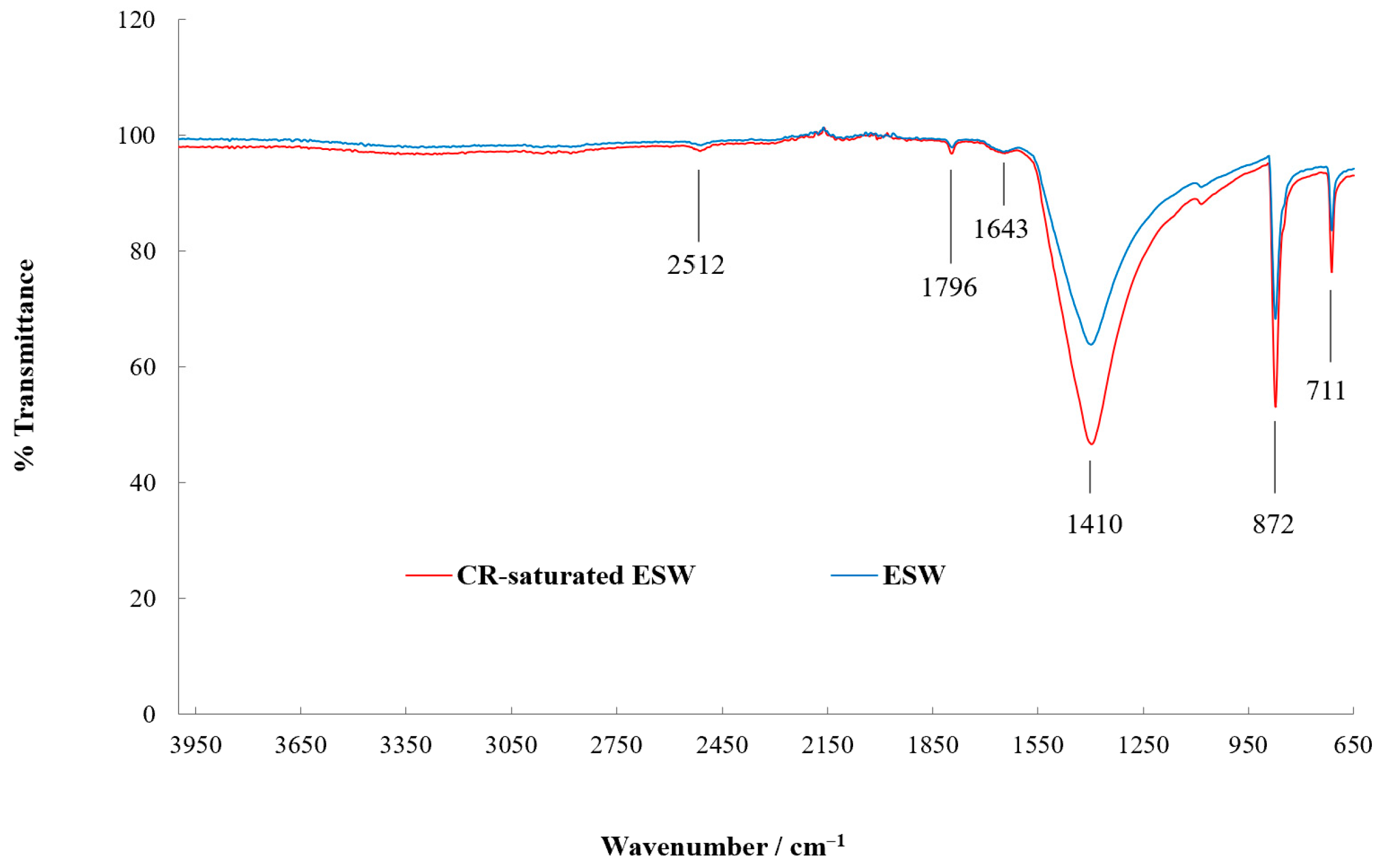

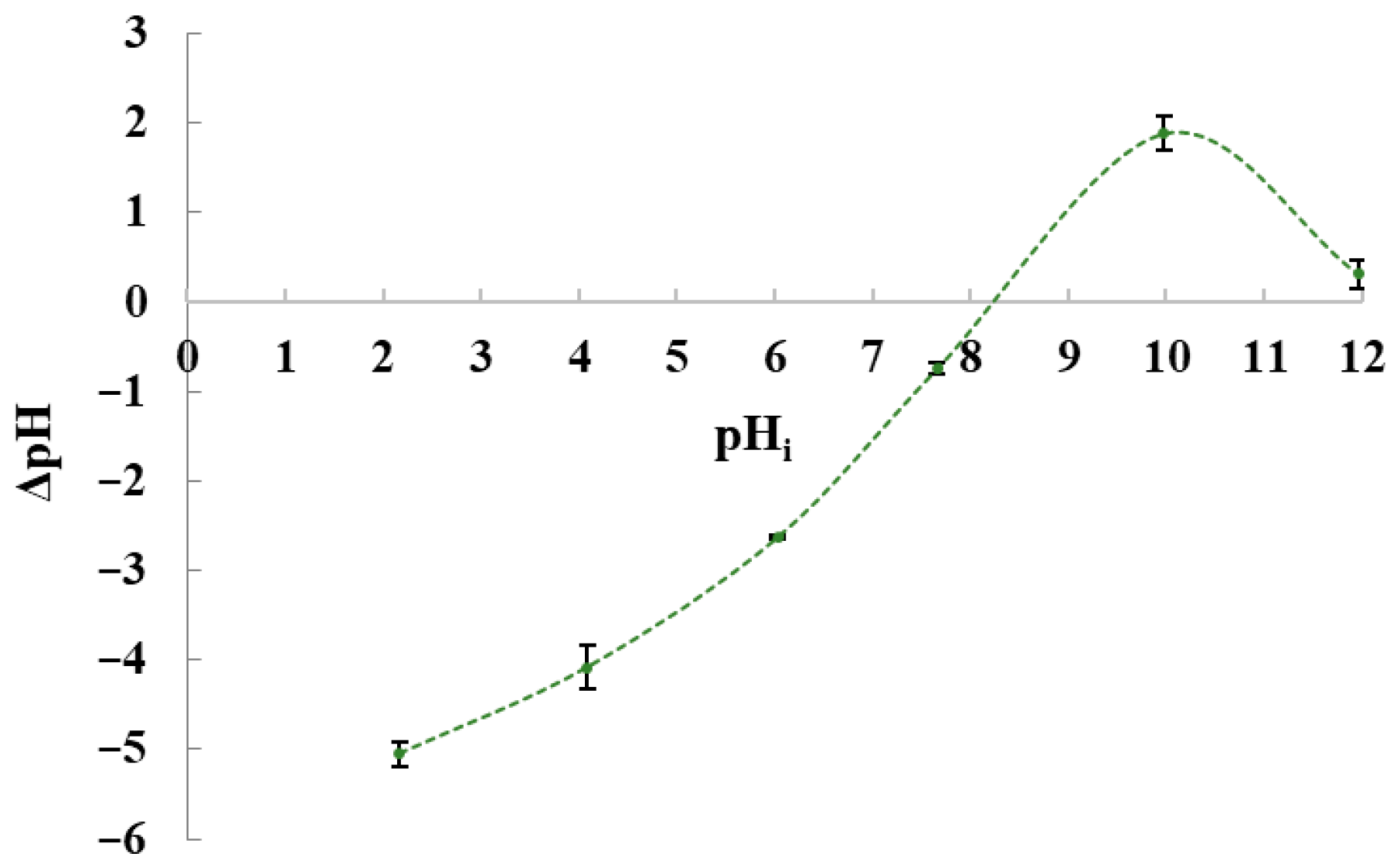

3.1. ESW Characterisation

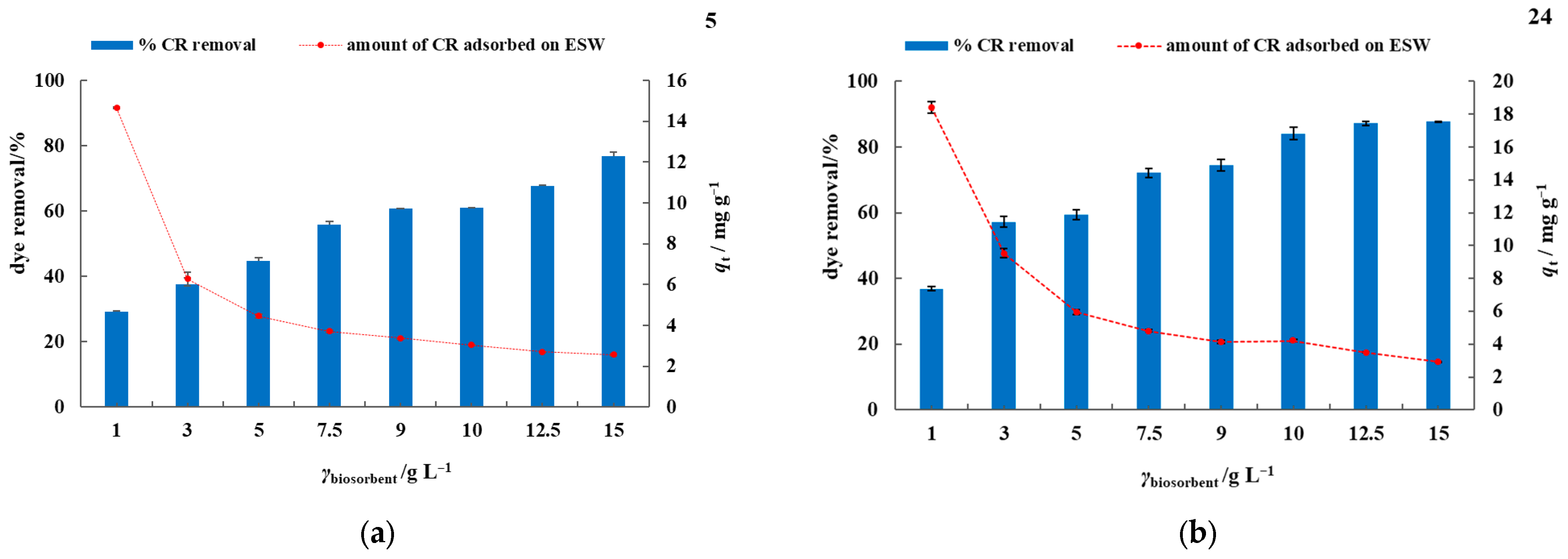

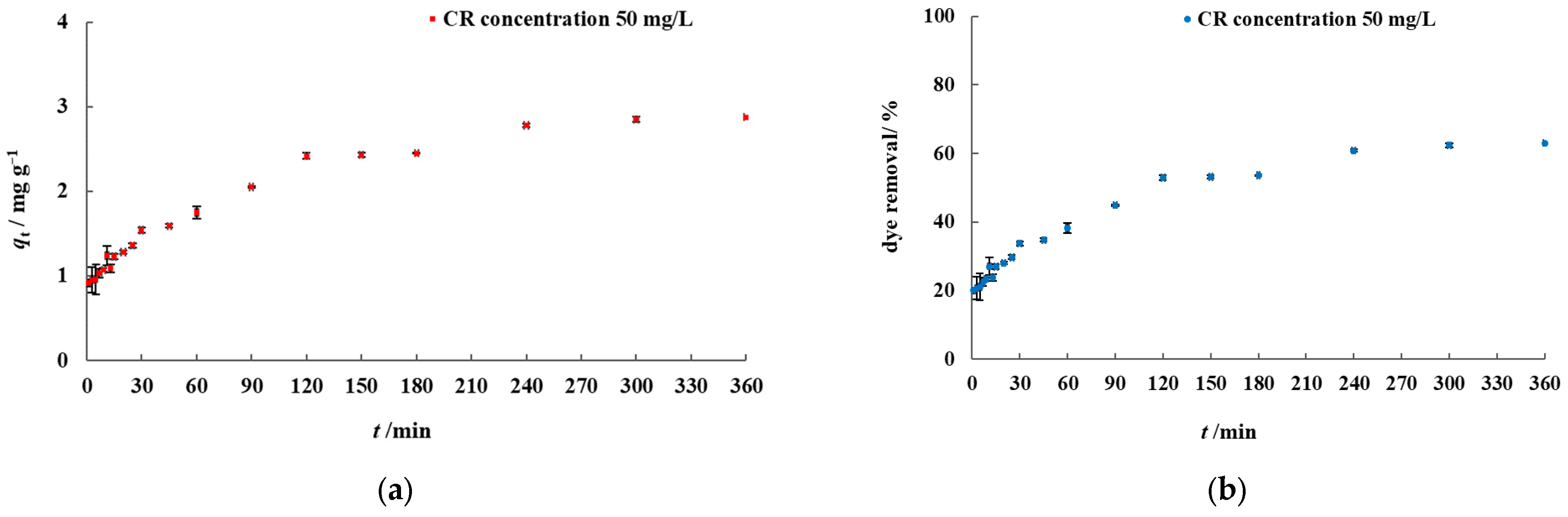

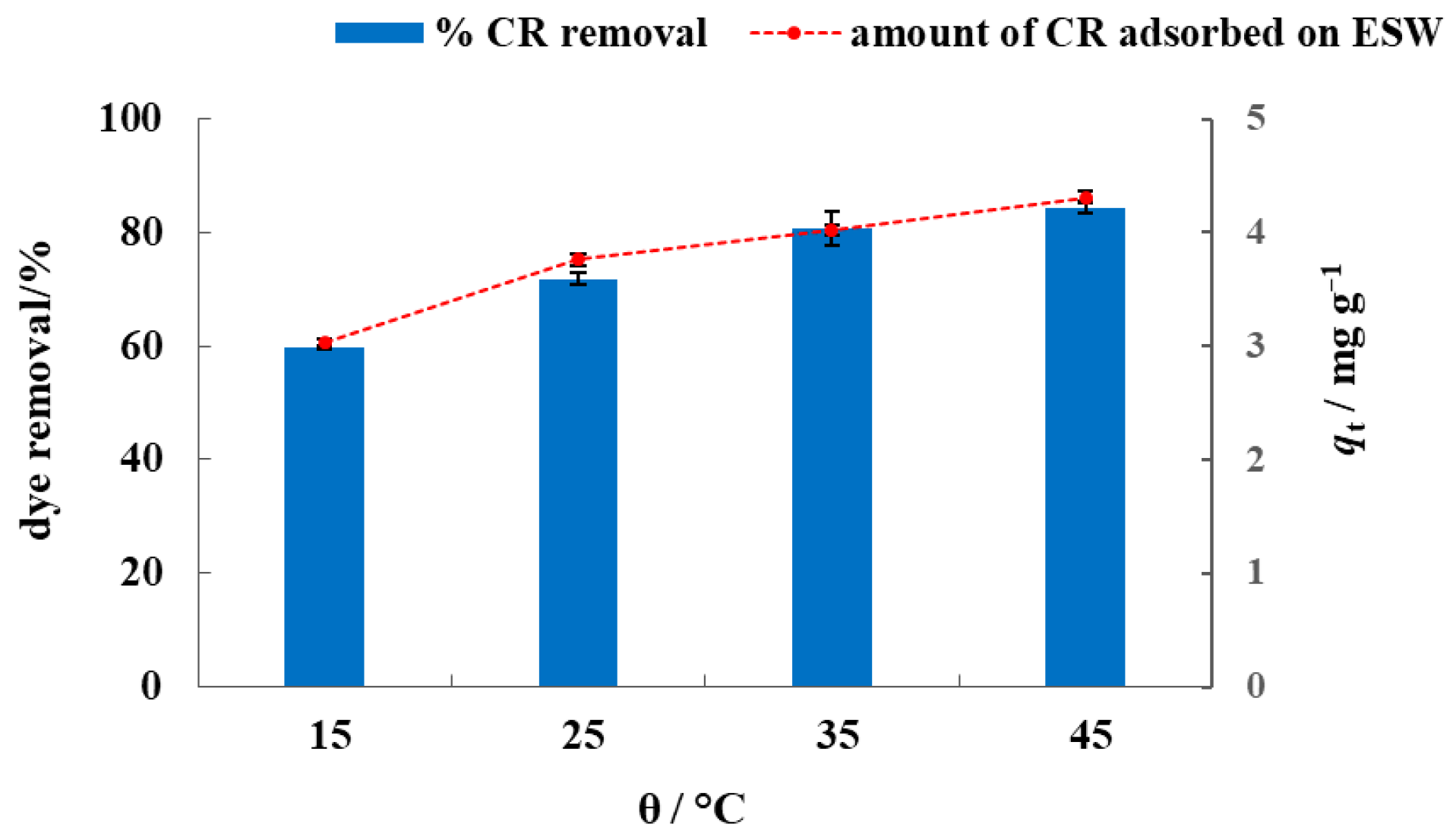

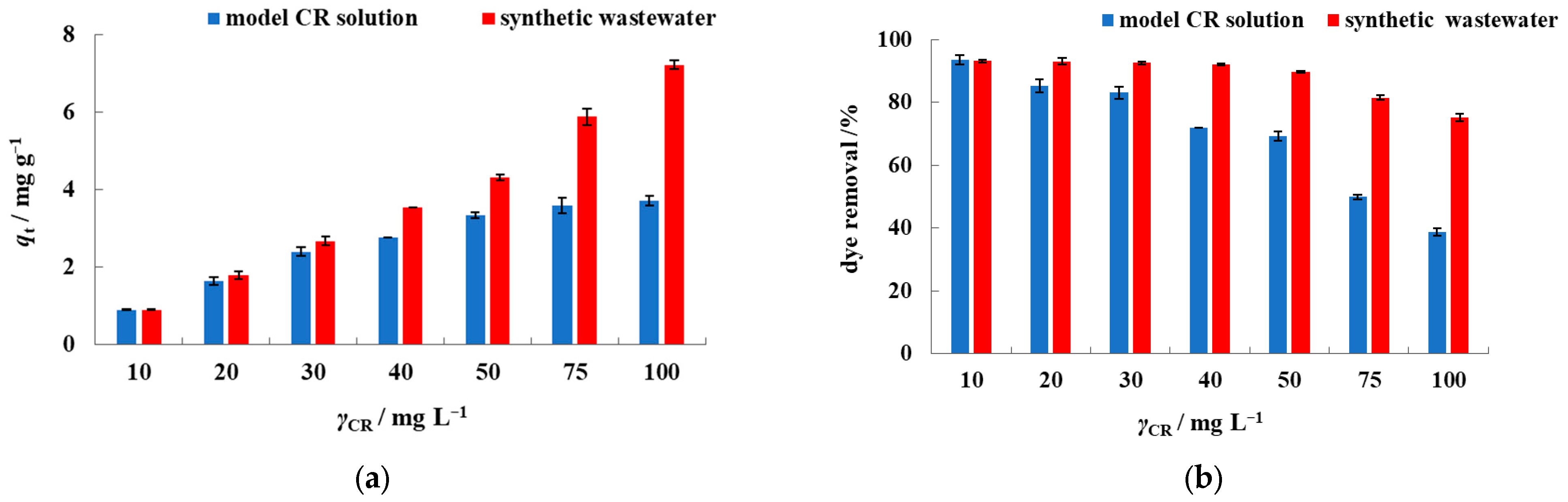

3.2. Batch Biosorption Studies in Model Dye Solution and Synthetic Wastewater

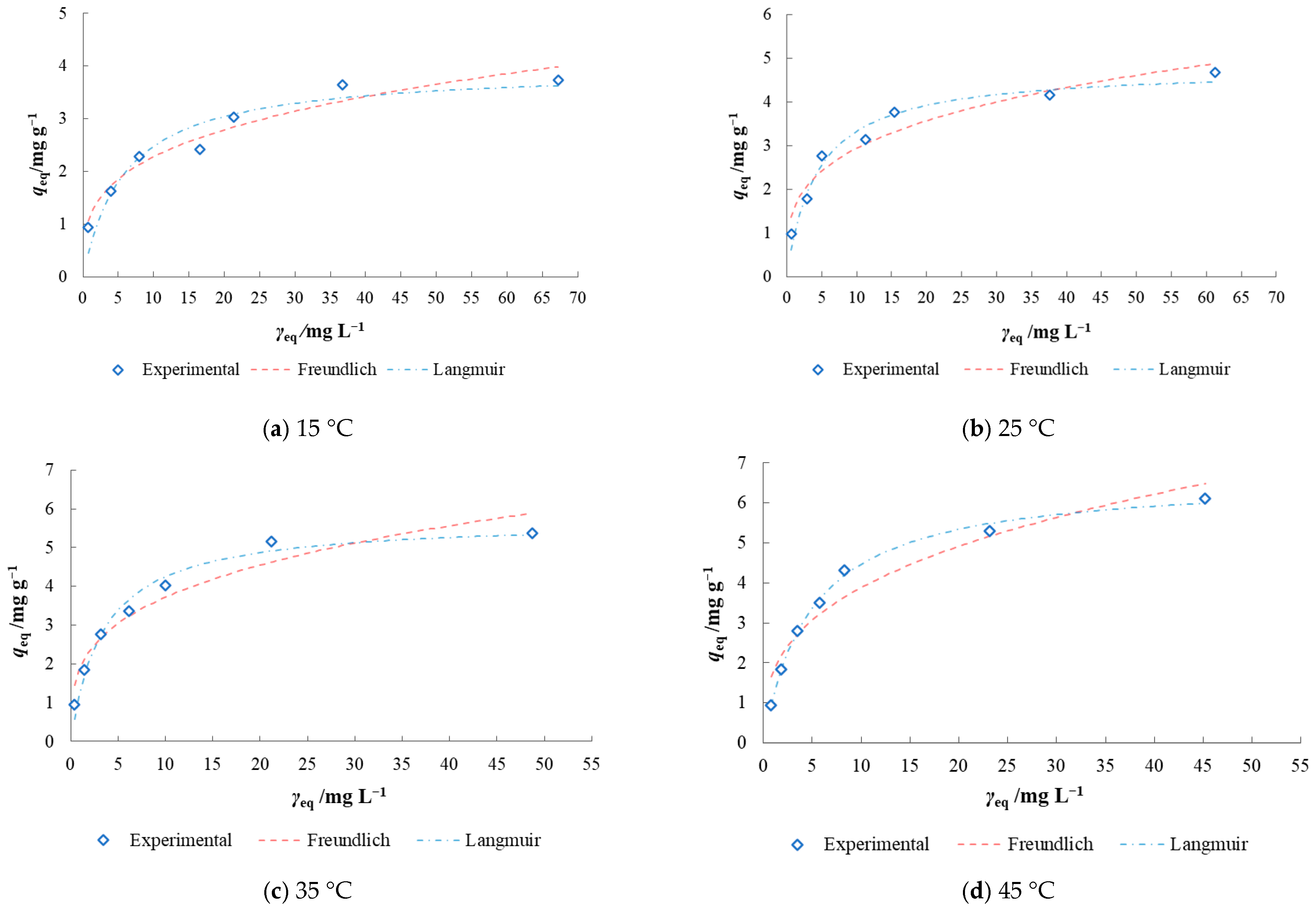

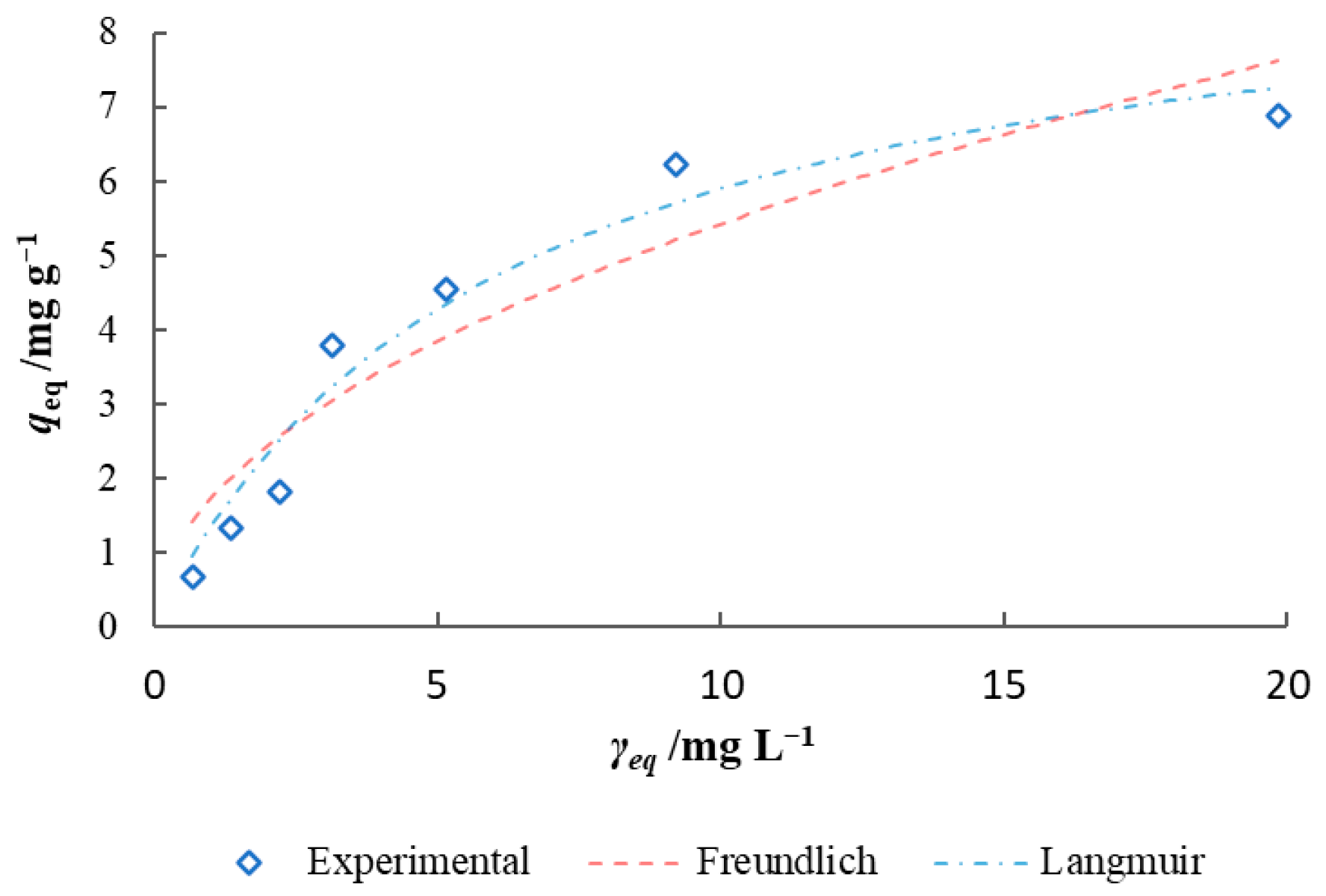

3.3. Isotherm and Kinetic Modelling of Batch Biosorption Data

3.4. Adsorption Capacities of Eggshell Waste and Other Waste-Derived Biological Materials Toward Synthetic Dyes

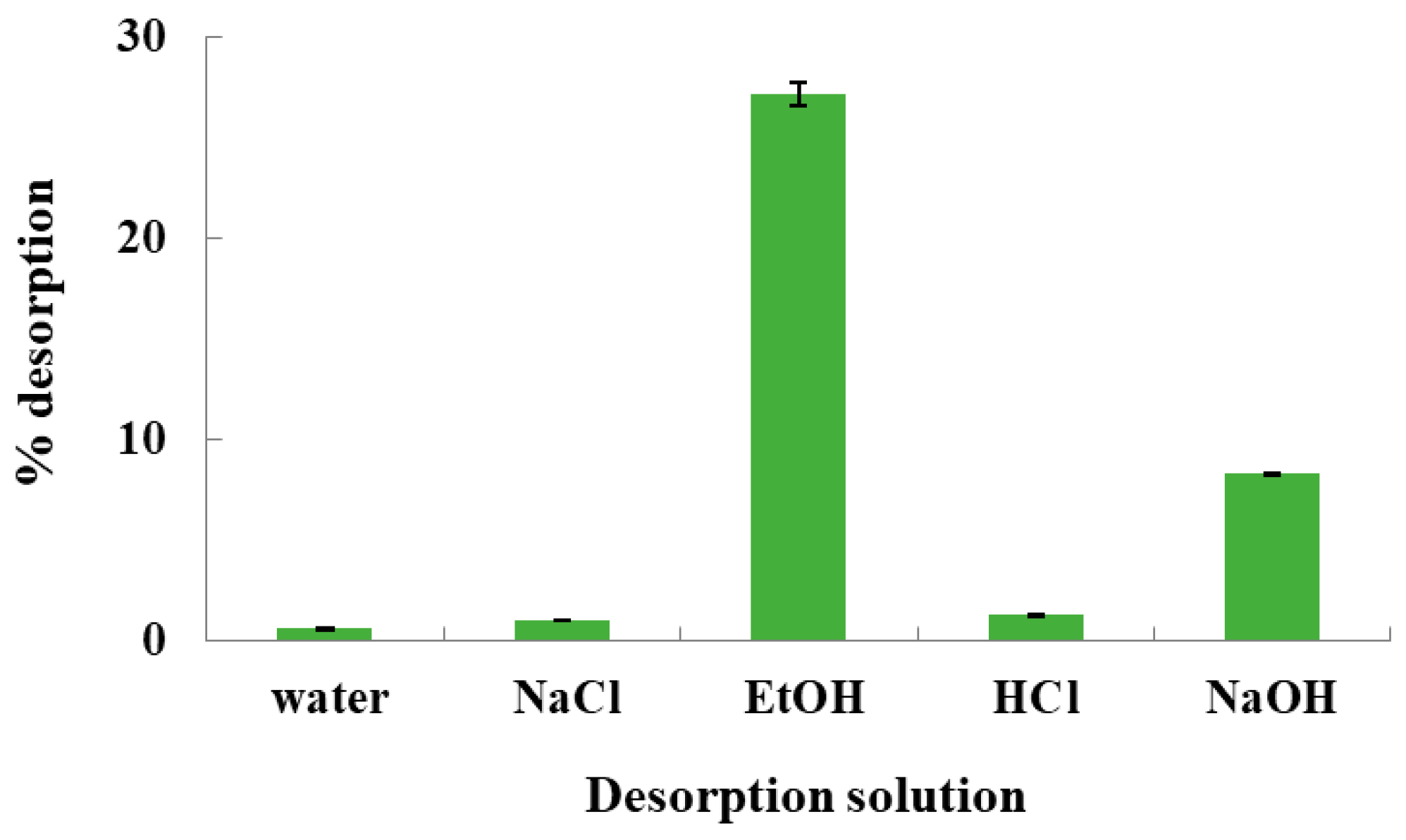

3.5. Desorption Experiments

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abín, R.; Laca, A.; Laca, A.; Díaz, M. Environmental Assesment of Intensive Egg Production: A Spanish Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignardi, S.; Archilletti, L.; Medeghini, L.; De Vito, C. Valorization of Eggshell Biowaste for Sustainable Environmental Remediation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babalola, B.M.; Wilson, L.D. Valorization of Eggshell as Renewable Materials for Sustainable Biocomposite Adsorbents—An Overview. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeginste, V. Food Waste Eggshell Valorization through Development of New Composites: A Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 29, e00317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelec, I.; Tomičić, K.; Zajec, M.; Ostojčić, M.; Budžaki, S. Eggshell-Waste-Derived Calcium Acetate, Calcium Hydrogen Phosphate and Corresponding Eggshell Membranes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolińska, B.; Jelińska, M.; Szulc-Musioł, B.; Ryszka, F. Use of Eggshells as a Raw Material for Production of Calcium Preparations. Czech J. Food Sci. 2016, 34, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y. Preparation of Calcium Magnesium Acetate Snow Melting Agent Using Raw Calcium Acetate-Rich Made from Eggshells. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2020, 11, 6757–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hincke, M.T.; Nyes, Y.; Gautron, J.; Mann, K.; Rodriguez-Navarro, A.B.; McKee, M.D. The Eggshell: Structure, Composition and Mineralization. Front. Biosci. 2012, 17, 1266–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridi, H.; Arabhosseini, A. Application of Eggshell Wastes as Valuable and Utilizable Products: A Review. Res. Agric. Eng. 2018, 64, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, M.; Butt, M.S.; Shehzad, A.; Adzahan, N.M.; Shabbir, M.A.; Rasul Suleria, H.A.; Aadil, R.M. Eggshell Calcium: A Cheap Alternative to Expensive Supplements. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Sen, R. A Comparative Performance Evaluation of Jute and Eggshell Matrices to Immobilize Pancreatic Lipase. Process Biochem. 2012, 47, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, H.P.S.; Sharma, O.P. Egg Shell as a Carrier for Enzyme Immobilization. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1983, 25, 595–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salleh, S.; See, Y.S.; Serri, N.A.; Hena, S.; Tajarudin, H.A. Synthesis of Butyl Butyrate in 93% Yield by Thermomyces Lanugonisus Lipase on Waste Eggshells. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2016, 14, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, I.; Chojnacka, K.; Witek-Krowiak, A. State of the Art for the Biosorption Process—A Review. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 170, 1389–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, M.A.; Abdel Rahman, M.K.; Francis, A.A. Exploring the Adsorption Behavior of Cationic and Anionic Dyes on Industrial Waste Shells of Egg. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nasir, H.A.; Mohammed, S.S. Experimental Investigation on Adsorption of Methyl Orange Using Eggshells as Adsorbent Surface. Ibn AL Haitham J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2023, 36, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, H.A.; Mohammed, M.M.; Sultan, A.J.; Abbas, M.N.; Ibrahim, T.A.; Aljaafari, H.A.S.; Alminshid, A.A. Adsorption of Methyl Green Stain from Aqueous Solutions Using Non-Conventional Adsorbent Media: Isothermal Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2021, 14, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevira, L.; Rahmi, A.; Zein, R.; Zilfa, Z.; Rahmayeni, R. The Fast and of Low-Cost-Adsorbent to the Removal of Cationic and Anionic Dye Using Chicken Eggshell with Its Membrane. Mediterr. J. Chem. 2020, 10, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadam, S.; Javed, T.; Jilani, M.I. Adsorptive Exclusion of Crystal Violet Dye from Wastewater Using Eggshells: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Study. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 268, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murcia-Salvador, A.; Pellicer, J.A.; Rodríguez-López, M.I.; Gómez-López, V.M.; Núñez-Delicado, E.; Gabaldón, J.A. Egg By-Products as a Tool to Remove Direct Blue 78 Dye from Wastewater: Kinetic, Equilibrium Modeling, Thermodynamics and Desorption Properties. Materials 2020, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofudje, E.A.; Sodiya, E.F.; Ibadin, F.H.; Ogundiran, A.A.; Alayande, S.O.; Osideko, O.A. Mechanism of Cu2+ and Reactive Yellow 145 Dye Adsorption onto Eggshell Waste as Low-Cost Adsorbent. Chem. Ecol. 2021, 37, 268–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, S.; Mamun, A.; Rubbi, M.F.; Ruman, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Biswas, B.K. Utilization of Egg-Shell, a Locally Available Biowaste Material, for Adsorptive Removal of Congo Red from Aqueous Solution. Aceh Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajoriya, S.; Saharan, V.K.; Pundir, A.S.; Nigam, M.; Roy, K. Adsorption of Methyl Red Dye from Aqueous Solution onto Eggshell Waste Material: Kinetics, Isotherms and Thermodynamic Studies. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonato, R.D.O.; Estevam, B.R.; Perez, I.D.; Aparecida Dos Santos Ribeiro, V.; Boina, R.F. Eggshell as an Adsorbent for Removing Dyes and Metallic Ions in Aqueous Solutions. Clean. Chem. Eng. 2022, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatan, O.G.; Alaba, P.A.; Oni, B.A.; Akpojevwe, K.; Efeovbokhan, V.; Abnisa, F. Performance of Eggshells Powder as an Adsorbent for Adsorption of Hexavalent Chromium and Cadmium from Wastewater. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Salih, N.R. Application of Eggshell Wastes for Boron Remediation from Water. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 256, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.-Y.; Lee, T.-A.; Lin, Y.-S.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Wang, M.-F.; Li, P.-H.; Huang, P.-H.; Lu, W.-C.; Ho, J.-H. On the Removal Efficiency of Copper Ions in Wastewater Using Calcined Waste Eggshells as Natural Adsorbents. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabbas, S.; Mandi, L.; Berrekhis, F.; Pons, M.N.; Leclerc, J.P.; Ouazzani, N. Removal of Cr(III) from Chrome Tanning Wastewater by Adsorption Using Two Natural Carbonaceous Materials: Eggshell and Powdered Marble. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 166, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraei, H.; Mittal, A.; Noorisepehr, M.; Daraei, F. Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies of Adsorptive Removal of Phenol onto Eggshell Waste. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 4603–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwakeel, K.Z.; Yousif, A.M. Adsorption of Malathion on Thermally Treated Egg Shell Material. Water Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfikar, M.A.; Novita, E.; Hertadi, R.; Djajanti, S.D. Removal of Humic Acid from Peat Water Using Untreated Powdered Eggshell as a Low Cost Adsorbent. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 1357–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutavdžić Pavlović, D.; Ćurković, L.; Macan, J.; Žižek, K. Eggshell as a New Biosorbent for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals From Aqueous Solutions. Clean Soil Air Water 2017, 45, 1700082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafatullah, M.; Sulaiman, O.; Hashim, R.; Ahmad, A. Adsorption of Methylene Blue on Low-Cost Adsorbents: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 177, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourhakkak, P.; Taghizadeh, M.; Taghizadeh, A.; Ghaedi, M. Adsorbent. In Adsorption: Fundamental Processes and Applications; Ghaedi, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 71–210. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Jiang, X.; Li, T. Adsorption Behavior of Direct Red 80 and Congo Red onto Activated Carbon/Surfactant: Process Optimization, Kinetics and Equilibrium. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 137, 1126–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgacs, E.; Cserháti, T.; Oros, G. Removal of Synthetic Dyes from Wastewaters: A Review. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 953–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, R. Textile Dyeing Industry an Environmental Hazard. Nat. Sci. 2012, 04, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkurt, E.A.; Ünyayar, A.; Kumbur, H. Decolorization of Synthetic Dyes by White Rot Fungi, Involving Laccase Enzyme in the Process. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naushad, M.; Govarthanan, M.; Iqbal, J.; Alfadul, S.M. Emerging Contaminants of High Concern for the Environment: Current Trends and Future Research. Environ. Res. 2022, 207, 112609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, A.; Mitrowska, K.; Posyniak, A. Synthetic Organic Dyes as Contaminants of the Aquatic Environment and Their Implications for Ecosystems: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 717, 137222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, D.A.; Scholz, M. Textile Dye Wastewater Characteristics and Constituents of Synthetic Effluents: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 1193–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laing, I.G. The Impact of Effluent Regulations on the Dyeing Industry. Rev. Prog. Color. Relat. Top. 1991, 21, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gähr, F.; Hermanutz, F.; Oppermann, W. Ozonation—an important technique to comply with new german laws for textile wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 1994, 30, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, A.; Ananthashankar, R.; Alhattab, M.; Ramakrishnan, V. Production, Characterization and Treatment of Textile Effluents: A Critical Review. Chem. Eng. Process Technol. 2013, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H. Biodegradation of Synthetic Dyes—A Review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2010, 213, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilada, O.; Asma, D.; Cing, S. Decolorization of Textile Dyes by Fungal Pellets. Process Biochem. 2003, 38, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoor, S.; Karayil, J.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Siengchin, S. Removal of Anionic Dye Congo Red from Aqueous Environment Using Polyvinyl Alcohol/Sodium Alginate/ZSM-5 Zeolite Membrane. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asses, N.; Ayed, L.; Hkiri, N.; Hamdi, M. Congo Red Decolorization and Detoxification by Aspergillus Niger: Removal Mechanisms and Dye Degradation Pathway. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladoye, P.O.; Bamigboye, M.O.; Ogunbiyi, O.D.; Akano, M.T. Toxicity and Decontamination Strategies of Congo Red Dye. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 19, 100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strelec, I.; Ostojčić, M.; Brekalo, M.; Hajra, S.; Kim, H.-J.; Stanojev, J.; Maravić, N.; Budžaki, S. Transformation of Eggshell Waste to Egg White Protein Solution, Calcium Chloride Dihydrate, and Eggshell Membrane Powder. Green Process. Synth. 2023, 12, 20228151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, N.; Villaescusa, I. Determination of Sorbent Point Zero Charge: Usefulness in Sorption Studies. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2009, 7, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 302B: Inherent Biodegradability: Zahn-Wellens/EVPA Tes. In OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; Section 3; OECD: Paris, France, 1992; ISBN 978-92-64-07038-7. [Google Scholar]

- Freundlich, H.M.F. Over the Adsorption in Solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1906, 57, 385–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surface of Glass, Mica and Platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.M.; Hamad, H.A.; Hussein, M.M.; Malash, G.F. Potential of Using Green Adsorbent of Heavy Metal Removal from Aqueous Solutions: Adsorption Kinetics, Isotherm, Thermodynamic, Mechanism and Economic Analysis. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 91, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pap, S.; Radonić, J.; Trifunović, S.; Adamović, D.; Mihajlović, I.; Vojinović Miloradov, M.; Turk Sekulić, M. Evaluation of the Adsorption Potential of Eco-Friendly Activated Carbon Prepared from Cherry Kernels for the Removal of Pb2+, Cd2+ and Ni2+ from Aqueous Wastes. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 184, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. The Sorption of Lead(II) Ions on Peat. Water Res. 1999, 33, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S. Review of Second-Order Models for Adsorption Systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellenz, L.; De Oliveira, C.R.S.; Da Silva Júnior, A.H.; Da Silva, L.J.S.; Da Silva, L.; Ulson De Souza, A.A.; De Souza, S.M.D.A.G.U.; Borba, F.H.; Da Silva, A. A Comprehensive Guide for Characterization of Adsorbent Materials. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 305, 122435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, V.-P.; Huynh, T.-D.-T.; Le, H.M.; Nguyen, V.-D.; Dao, V.-A.; Hung, N.Q.; Tuyen, L.A.; Lee, S.; Yi, J.; Nguyen, T.D.; et al. Insight into the Adsorption Mechanisms of Methylene Blue and Chromium (III) from Aqueous Solution onto Pomelo Fruit Peel. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 25847–25860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hanafy, H.; Zhang, L.; Sellaoui, L.; Schadeck Netto, M.; Oliveira, M.L.S.; Seliem, M.K.; Luiz Dotto, G.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Li, Q. Adsorption of Congo Red and Methylene Blue Dyes on an Ashitaba Waste and a Walnut Shell-Based Activated Carbon from Aqueous Solutions: Experiments, Characterization and Physical Interpretations. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-97670-7. [Google Scholar]

- Salah, S.B.; Attia, A.; Ben Amar, R.; Heran, M. Eggshell Waste as a Sustainable Adsorbent for Effective Removal of Direct Dyes from Textile Wastewater. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e202500149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizo, M.S.; Blanco, L.A.V.; Cagas, A.C.Q.; Dela Cruz, B.R.B.; Encoy, J.C.; Gunting, J.V.; Arazo, R.O.; Mabayo, V.I.F. Efficiency of Calcium Carbonate from Eggshells as an Adsorbent for Cadmium Removal in Aqueous Solution. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaycı, T.; Altuğ, D.T.; Kınaytürk, N.K.; Tunalı, B. Characterization and Potential Usage of Selected Eggshell Species. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awogbemi, O.; Inambao, F.; Onuh, E.I. Modification and Characterization of Chicken Eggshell for Possible Catalytic Applications. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, W. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy in Sample Preparation: Material Characterization and Mechanism Investigation. Adv. Sample Prep. 2024, 11, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praipipat, P.; Ngamsurach, P.; Pratumkaew, K. The Synthesis, Characterizations, and Lead Adsorption Studies of Chicken Eggshell Powder and Chicken Eggshell Powder-Doped Iron (III) Oxide-Hydroxide. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annane, K.; Lemlikchi, W.; Tingry, S. Efficiency of Eggshell as a Low-Cost Adsorbent for Removal of Cadmium: Kinetic and Isotherm Studies. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2023, 13, 6163–6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, S.; Biswas, B.K.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.H.; Anik, M.S.; Uddin, M.R. Study on Adsorption of Congo Red onto Chemically Modified Egg Shell Membrane. Chemosphere 2019, 236, 124326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rápó, E.; Aradi, L.E.; Szabó, Á.; Posta, K.; Szép, R.; Tonk, S. Adsorption of Remazol Brilliant Violet-5R Textile Dye from Aqueous Solutions by Using Eggshell Waste Biosorbent. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gündüz, F.; Bayrak, B. Biosorption of Malachite Green from an Aqueous Solution Using Pomegranate Peel: Equilibrium Modelling, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 243, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfikar, M.A.; Setiyanto, H. Adsorption Of Congo Red From Aqueous Solution Using Powdered Eggshell. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2013, 5, 1532–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P.D.; Chowdhury, S.; Mondal, M.; Sinha, K. Biosorption of Direct Red 28 (Congo Red) from Aqueous Solutions by Eggshells: Batch and Column Studies. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Sikarwar, S. Adsorption and Desorption Studies of Congo Red Using Low-Cost Adsorbent: Activated de-Oiled Mustard. Desalin. Water Treat. 2014, 52, 7400–7411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, R.G.; Sun, Q.; Munagapati, V.S.; Saratale, G.D.; Park, J.; Kim, D.-S. The Use of Eggshell Membrane for the Treatment of Dye-Containing Wastewater: Batch, Kinetics and Reusability Studies. Chemosphere 2021, 281, 130777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-T.; Hsien, K.-J.; Hsu, H.-C.; Lin, C.-M.; Lin, K.-Y.; Chiu, C.-H. Utilization of Ground Eggshell Waste as an Adsorbent for the Removal of Dyes from Aqueous Solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, X.Z.; Qin, P.; Pan, M.Y. Remove of Congo Red from Wastewater by Adsorption onto Eggshell Membrane. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 599, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, N.K.; Kar, S. Potentiality of Banana Peel for Removal of Congo Red Dye from Aqueous Solution: Isotherm, Kinetics and Thermodynamics Studies. Appl. Water Sci. 2018, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanyonyi, W.C.; Onyari, J.M.; Shiundu, P.M. Adsorption of Congo Red Dye from Aqueous Solutions Using Roots of Eichhornia Crassipes: Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies. Energy Procedia 2014, 50, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjepanović, M.; Velić, N.; Galić, A.; Kosović, I.; Jakovljević, T.; Habuda-Stanić, M. From Waste to Biosorbent: Removal of Congo Red from Water by Waste Wood Biomass. Water 2021, 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velić, N.; Stjepanović, M.; Pavlović, S.; Bagherifam, S.; Banković, P.; Jović-Jovičić, N. Modified Lignocellulosic Waste for the Amelioration of Water Quality: Adsorptive Removal of Congo Red and Nitrate Using Modified Poplar Sawdust. Water 2023, 15, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelaja, O.A.; Bankole, A.C.; Oladipo, M.E.; Lene, D.B. Biosorption of Hg(II) Ions, Congo Red and Their Binary Mixture Using Raw and Chemically Activated Mango Leaves. Int. J. Energy Water Res. 2019, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezerle, A.; Velić, N.; Hasenay, D.; Kovačević, D. Lignocellulosic Materials as Dye Adsorbents: Adsorption of Methylene Blue and Congo Red on Brewers’ Spent Grain. Croat. Chem. Acta 2018, 91, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahim, A.R.; Mohsin, H.M.; Chin, K.B.L.; Johari, K.; Saman, N. Promising Low-Cost Adsorbent from Desiccated Coconut Waste for Removal of Congo Red Dye from Aqueous Solution. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsan, S.; Murugesan, G.; Varadavenkatesan, T.; Vinayagam, R.; Selvaraj, R. Efficient Adsorptive Removal of Congo Red Dye Using Activated Carbon Derived from Spathodea Campanulata Flowers. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkika, D.A.; Tolkou, A.K.; Poulopoulos, S.G.; Kalavrouziotis, I.K.; Kyzas, G.Z. Cost-Effectiveness of Regenerated Green Materials for Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Wastewater. Waste Manag. 2025, 204, 114952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omorogie, M.O.; Babalola, J.O.; Unuabonah, E.I. Regeneration Strategies for Spent Solid Matrices Used in Adsorption of Organic Pollutants from Surface Water: A Critical Review. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 518–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawy, T.; Rashad, E.; El-Qelish, M.; Mohammed, R.H. A Comprehensive Review on the Chemical Regeneration of Biochar Adsorbent for Sustainable Wastewater Treatment. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Lee, U.; Kim, H.-W.; Cho, M.; Lee, J. Zero Discharge of Dyes and Regeneration of a Washing Solution in Membrane-Based Dye Removal by Cold Plasma Treatment. Membranes 2022, 12, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| The Effect of Different Biosorption Parameters | Biosorbent Concentration γ/g L−1 | Adsorbate Concentration γ/mg L−1 | Contact Time t/min | Temperature θ/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosorption in model CR solution | ||||

| Biosorbent concentration | 1–15 | 50 | 300, 1440 | 25 |

| Contact time | 10 | 50 | 1–360 | 25 |

| Temperature | 10 | 10–100 | 360 | 15–45 |

| Initial dye concentration | 10 | 10–100 | 360 | 25 |

| Biosorption in synthetic wastewater with the addition of CR | ||||

| Contact time | 10 | 50 | 1–360 | 25 |

| Initial dye concentration | 10 | 10–100 | 360 | 25 |

| Model | 15 °C | 25 °C | 35 °C | 45 °C | 25 °C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model CR Solution | Synthetic Wastewater | ||||

| qexp/mg g−1 | 3.74 | 4.68 | 5.38 | 6.12 | 5.62 |

| Freundlich | |||||

| KF/(mg g−1 (L/mg)1/n) | 1.155 | 1.545 | 1.911 | 1.775 | 1.733 |

| n | 3.398 | 3.579 | 3.451 | 2.942 | 2.017 |

| R2 | 0.954 | 0.941 | 0.939 | 0.937 | 0.884 |

| RMSE | 0.205 | 0.295 | 0.375 | 0.431 | 0.764 |

| MSE | 0.042 | 0.087 | 0.140 | 0.185 | 0.583 |

| SQE | 0.295 | 0.611 | 0.983 | 1.297 | 4.082 |

| Chi-square | 0.108 | 0.272 | 0.343 | 0.530 | 1.382 |

| Langmuir | |||||

| qcal/mg g−1 | 3.947 | 4.767 | 5.714 | 6.639 | 9.476 |

| KL/L mg−1 | 0.168 | 0.231 | 0.291 | 0.206 | 0.165 |

| R2 | 0.910 | 0.966 | 0.977 | 0.996 | 0.958 |

| RMSE | 0.287 | 0.224 | 0.229 | 0.105 | 0.457 |

| MSE | 0.082 | 0.050 | 0.053 | 0.011 | 0.209 |

| SQE | 0.577 | 0.350 | 0.370 | 0.077 | 1.465 |

| Chi-square | 0.670 | 0.284 | 0.309 | 0.016 | 0.532 |

| Model | Model CR Solution | Synthetic Wastewater |

|---|---|---|

| qt,exp/mg g−1 | 3.033 | 3.390 |

| Pseudo-first order model (PFO) | ||

| qt1/mg g−1 | 2.489 | 3.051 |

| k1/min−1 | 0.401 | 0.066 |

| R2 | 0.686 | 0.828 |

| RMSE | 0.391 | 0.266 |

| MSE | 0.152 | 0.071 |

| SQE | 3.049 | 0.989 |

| Chi-square | 9.936 | 0.551 |

| Pseudo-second order model (PSO) | ||

| qt2/mg g−1 | 2.765 | 3.248 |

| k2/g mg−1 min−1 | 0.019 | 0.03 |

| R2 | 0.803 | 0.938 |

| RMSE | 0.309 | 0.159 |

| MSE | 0.096 | 0.025 |

| SQE | 1.913 | 0.356 |

| Chi-square | 5.706 | 0.185 |

| Adsorbent (Preparation) | Adsorbate | Adsorption Efficiency/% Langmuir Adsorption Capacity/mg g−1 | Experimental Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eggshell waste (H2O, sodium dodecyl sulfate, acetone) | Congo Red anionic dye | 3.95–6.64 mg g−1 (model CR solution) 9.47 mg g−1 (synthetic wastewater) | γdye = 10–100 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 10 g L−1, 360 min, 15–45 °C | This study |

| Eggshell Waste | Congo Red anionic dye | 49.50 mg g−1 | γdye = 50–1000 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 10 g L−1, 120 min, 25 °C | [15] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Congo Red anionic dye | 64.25–69.46 mg g−1 | γdye = 10–100 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 3 g L−1, 240 min, 20–40 °C | [74] |

| Eggshell waste (H2O, activation with 0.1 M H2SO4) | Congo Red anionic dye | 99.5% 153.85 mg g−1 | γbiosorbent = 10 g L−1, 120 min, 25 °C | [22] |

| Eggshell Waste without membrane (H2O) | Congo Red anionic dye | 95.25 mg g−1 | γdye = 20–80 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 100 g L−1, 20 min, 25 °C | [73] |

| Eggshell membrane (modification with HCl/NaOH) | Congo Red anionic dye | 95% 117.65 mg g−1 | γdye = 25–500 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 10 g L−1, 180 min, 20–40 °C | [70] |

| Eggshell membrane | Congo Red anionic dye | 99.17% 112.30 mg g−1 | γdye = 25–100 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 0.1–0.5 g L−1, 30–240 min, 20–40 °C | [79] |

| Encapsulated eggshell membrane (polyvinyl alcohol/sodium alginate) | Congo Red anionic dye | 98.86% | γdye = 12.63 mg L−1, mbiosorbent = 6.12 g, 12.83 min, pH 2.19 | [80] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Methyl Red anionic dye | 1.66 mg g−1 | γdye = 20–100 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 26.7 g L−1, 180 min, 25 °C | [23] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Methyl Orange anionic dye | 62.33% 5.58–135.13 mg g−1 | γdye = 20–120 mg L−1, mbiosorbent = 0.4 g, 25 min, 20–40 °C | [16] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Direct Blue 78 anionic dye | 13 mg g−1 | γdye = 25–300 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 12.5 g L−1, 140 min, 29 °C | [20] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Reactive Blue 198 anionic dye | 96.41% 0.8 mg g−1 | γdye = 0.5–30 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 20 g L−1, 60 min, 25 °C | [24] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Direct Black 22 anionic dye | 96.67% 1.99 mg g−1 | γdye = 0.5–30 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 20 g L−1, 120 min, 25 °C | [24] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Remazol Brilliant Violet-5R anionic dye | <90% 9.94 mg g−1 | γdye = 20–100 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 15 g L−1, 20 °C | [71] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O, HCl, NaOH) | Reactive Red 120 anionic dye | 160.8–191.5 mg g−1 | γdye = 100–1000 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 15 g L−1, 25–45 °C | [76] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O, 0.1 M NaOH) | Reactive Yellow 145 anionic dye | 84.05% 88.45 mg g−1 | γdye = 10–150 mg L−1, mbiosorbent = 0.025 g, 80 min, 45 °C | [21] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O, activation with HNO3) | Indigo Carmine anionic dye | 64.34% 8.04 mg g−1 | γdye = 10–50 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 20 g/L, 15 min | [18] |

| Eggshell Waste | Methylene Blue cationic dye | 94.9 mg g−1 | γdye = 50–1000 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 10 g L−1, 105 min, 25 °C | [15] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Methyl Green cationic dye | 69.38% | γdye = 1–100 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 16 g L−1, 120 min, 20–50 °C | [17] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O) | Crystal (Methyl) Violet cationic dye | 25.73 mg g−1 | γdye = 5–120 mg L−1, mbiosorbent = 0.6 g, 120 min, 10 °C | [19] |

| Eggshell Waste (H2O, activation with HNO3) | Methylene Blue cationic dye | 92.34% 11.54 mg g−1 | γdye = 10–50 mg L−1, γbiosorbent = 40 g L−1, 30 min | [18] |

| Biosorbent (Waste-Derived Biological Material) | Adsorbate | Langmuir Adsorption Capacity/mg g−1 (CR Concentration Range) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eggshell waste | Congo Red | 4.77 mg g−1 (10–100 mg L−1) | This study |

| Banana peel | 1.73 mg g−1 (20–40 mg L−1) | [79] | |

| Roots of Eichhornia Crassipes | 1.58 mg g−1 (10.45–104.45 mg L−1) | [80] | |

| Poplar sawdust | 8.00 mg g−1 (10–100 mg L−1) | [81] | |

| Modified poplar sawdust (through quaternisation) | 70.30 mg g−1 (25–250 mg L−1) | [82] | |

| Chemically activated mango leaves | 21.28 mg g−1 (30–120 mg L−1) | [83] | |

| Brewers’ spent grains | 19.65 mg g−1 (15–150 mg L−1) | [84] | |

| Activated de-oiled mustard | 34.73 mg g−1 (6.97–69.97 mg L−1) | [75] | |

| Desiccated coconut waste | 48.76 mg g−1 (10–50 mg L−1) | [85] | |

| Activated carbon derived from Spathodea campanulata flowers | 59.27 mg g−1 (20–60 mg L−1) | [86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Velić, N.; Stjepanović, M.; Ostojčić, M.; Švarc, H.; Strelec, I.; Budžaki, S. Valorisation of Eggshell Waste for Effective Biosorption of Congo Red Dye from Wastewater. Clean Technol. 2026, 8, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010002

Velić N, Stjepanović M, Ostojčić M, Švarc H, Strelec I, Budžaki S. Valorisation of Eggshell Waste for Effective Biosorption of Congo Red Dye from Wastewater. Clean Technologies. 2026; 8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelić, Natalija, Marija Stjepanović, Marta Ostojčić, Helena Švarc, Ivica Strelec, and Sandra Budžaki. 2026. "Valorisation of Eggshell Waste for Effective Biosorption of Congo Red Dye from Wastewater" Clean Technologies 8, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010002

APA StyleVelić, N., Stjepanović, M., Ostojčić, M., Švarc, H., Strelec, I., & Budžaki, S. (2026). Valorisation of Eggshell Waste for Effective Biosorption of Congo Red Dye from Wastewater. Clean Technologies, 8(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol8010002