1. Introduction

Waste heat recovery is currently one of the most studied solutions for increasing the efficiency in the energy production field and to reduce the carbon emissions related to fossil fuel combustion. Several technologies for waste heat recovery were proposed and studied. Analyses of the most relevant solutions—organic Rankine cycle (ORC), isobaric expansion engines, turbo compounding, steam Rankine cycles, thermoelectric generation, organic flash cycles, and Kalina cycles—are presented in [

1,

2,

3]. ORC systems are one of the most widely used technologies for power generation from waste heat sources with low temperatures. The typical temperature of the heat source is between 150 °C and 350 °C [

4]. However, ORC systems can also be used at temperatures even lower than 100 °C, as indicated by the numerous studies referred to in [

2]. Flexibility is another significant advantage of the ORC systems. They can operate with different heat sources (e.g., waste/renewable heat, air, seawater) and heat sink temperatures, which can be lowered even into the cryogenic range (e.g., in facilities for regasification of the liquefied natural gas) [

2,

3]. According to [

1], the ORC systems have efficiencies higher than almost all of the other alternative technologies (usually up to 25%) and can cover a wide range of output powers.

This low temperature is why the performance of ORC units is not remarkable. Performance improvement requires waste sources with higher temperatures, which in turn imply different, more suitable working fluids. According to an analysis of 129 fluids by Wang et al. [

5], toluene, benzene, and vinyl cyclohexane are the most promising working fluids. For higher-temperature waste heat sources, ORC systems become competitors for steam Rankine cycle (SRC) systems. Selecting the most appropriate working fluid for the ORC system is very important in any application and depends on technical, safety, and environmental issues, as shown in [

6,

7].

Typical ORC configurations have one pressure level; however, cycles with two levels have also been analyzed [

8]. The influence of the main ORC parameters (vaporization temperature, condensation temperature, and degree of superheat) on the performance of the power system was analyzed in [

9], while Braimakis and Karellas studied and parametrically optimized three ORC configurations with the aim of maximizing performance [

10]. An exergoeconomic procedure for optimizing the benefits of a two-pressure-level regenerative ORC system was performed by Samadi and Kazemi [

11]. The rate of investment in such a unit was analyzed in this study for fifteen countries, considering corporate tax and average electricity price. The highest profitability was observed in Germany, and the lowest was in India.

Usually, turbines are used as expanders in ORC systems of all sizes. A theoretical study of a micro-ORC unit using a turbine as an expander and operating with acetone and cyclopentane was conducted in [

12]. The maximum turbine and system efficiencies were estimated at 71% and 9.5%, respectively. An experimental study on a micro-ORC unit using a turbine as an expander and operating with R245fa as the working fluid was performed in [

13]. This study indicated that the maximum turbine and system efficiencies were less than 35% and 3.5%, respectively. Large- and medium-scale gas-organic combined cycle units based on commercial gas turbines were analyzed in [

14].

In a micro-ORC unit, a piston expander can be used instead of a turbine. A study of a micro-ORC system with a thermal input of 30 kW and a piston expander was performed in [

15], indicating an average efficiency of 40% for the expander and a net efficiency of 2.2% for the ORC system.

A common waste heat source for the ORC is the flue gas of reciprocating engines. There are also studies that used the flue gas of boilers operating in cogeneration units [

16] or poly-generation systems [

17], and low-pressure steam has also been considered as a potential heat source [

18].

Adding an ORC system downstream of a reciprocating internal combustion engine (ICE) or gas turbine is a solution for recovering waste heat, but it does increase the backpressure in the exhaust system, which has a negative impact on the engine’s performance. The influence of backpressure on the performance of a diesel engine with the ORC was analyzed in [

19]. This study indicates an average net benefit in power of 5.5% due to the ORC, in spite of the higher backpressure. The usage of ORC systems as additional power sources for an ICE was taken into consideration not only for stationary power units but also in the transportation sector. The limiting factors induced by the additional size and weight of the main components (heat recovery vapor generator (HRVG) and condenser) of the ORC system that is generating energy from the flue gas of a diesel engine equipped with a turbocharger were analyzed in [

20]. The economic impact of ORC implementation in the transportation sector was assessed by Pili et al. [

21], who took into consideration the benefits (efficiency improvements and fuel savings), as well as the drawbacks (reductions in the transport capacity due to the size and weight of the ORC system’s components).

The exhaust gas from a gas turbine represents a waste heat source in addition to those mentioned above. The waste heat from the exhaust gas of a gas turbine is typically recovered by connecting an SRC system downstream of the gas turbine. This configuration is used in conventional gas–steam combined cycle power plants (CCPPs), which have the highest efficiencies and are the most environmentally friendly medium- to large-scale power systems, being able to operate with efficiencies of up to 60%, a value estimated on the basis of a lower heating value [

22].

One possible way to recover and convert even more waste energy from the exhaust gas of the gas turbine into power is to add an ORC system downstream of the SRC system. This addition of the ORC system generates a novel power plant scheme. In this scheme, three elements are successively connected: a gas turbine unit, an SRC system, and the ORC system. This defines a gas–steam–organic combined cycle power plant (O-CCPP). A preliminary study on this scheme was conducted by the authors in 2018 [

23], involving an Orenda OGT 15000 gas turbine manufactured by Orenda Aerospace Corporation, Mississauga, Canada (with a rated output power of 16.5 MW, a pressure ratio of 20, and a turbine inlet temperature of 1348 K) as the core of the installation and the refrigerants R134a and R123 as the working fluids in the ORC system. A mathematical model was proposed, and an example calculation was performed for a single set of imposed parameters. The results proved the feasibility of using an ORC system downstream of the CCPP to enhance overall performance.

The current theoretical study on an O-CCPP delves into more complex aspects of this topic. The main goal of this paper is to identify the optimal values of the main parameters of the ORC that lead to the maximum performance of the plant. The targeted parameters were the degree of superheat, the pinch point temperature difference, vaporization pressure, and organic fluid mass flow rate. Establishing the correlations between these parameters and their influence on the ORC system’s performance were also targeted. Another objective is to evaluate the financial benefits and the CO

2 emission savings of the new plant scheme under optimum operation conditions. This is a novel approach of an ORC system operating on such levels of temperature and waste heat flow rate. The plant is based on a low-power gas turbine, namely the Solar Centaur 40 gas turbine with a rated output power of 3.5 MW (five time less than in [

23]), which was produced by Solar Turbines, a Caterpillar Company (San Diego, CA, USA). This class of gas turbines also has a significantly lower pressure ratio and turbine inlet temperature (10 and 1189 K, respectively). Consequently, the gas turbine’s performance is significantly lower, which makes waste heat recovery more interesting.

Implementation of the ORC technology at the level of the waste heat potential of O-CCPP with Solar Centaur 40 gas turbine (roughly 1.6 MW heat flow rate and flue gas temperature of roughly 190 °C) is novel. Several examples of ORC implementation highlight the applicability of this technology at similar temperatures of the waste heat across different industrial context but for larger power units. The following representative projects can be mentioned [

24,

25]: Holcim, Romania (installed electric power of 4000 kW, started up in 2012); Carpatcement (Heidelberg Cement), Romania (installed electric power of 3800 kW, started up in 2015); Holcim Suisse (Eclépens), Switzerland (installed electric power of 1300 kW, started up in 2019); Ludwigsburg, Germany (installed electric power of 2100 kW, started up in 2009); Varna, Bozen, Italy (installed electric power of 800 kW, started up in 2008). These examples illustrate the versatility of ORC implementations, emphasizing the adaptability of the technology to various industrial processes and operating conditions. Other technologies used at the similar flue gas temperature are the Stirling engine and the thermoelectric batteries, but for much lower power. The solution with Stirling engine is investigated in [

26], where the temperature of the residual flue gas is 214 °C, the waste heat flow rate is 627.5 kW, and the output power of the engine is 85.2 kW, resulting in an efficiency of 0.136. The use of the thermoelectric batteries for recovering waste heat from residual flue gases with the temperature ranging between 200 and 400 °C is studied in [

27]. A single thermoelectric cell produces only a few tens of watts, so thermoelectric batteries are assembled into modules. The paper investigates fully thermoelectrically lined chimneys, capable of generating up to approximately 7.5 kW of electric power with an efficiency of 0.045.

The current study was conducted using the latest-generation refrigerants in the ORC system, namely R1336mzz (Z), R1233zd (E), and R601a instead of R134a and R123, which were used in [

23]. This is due to the phasing out of R134a and R123 for new installations in 2022 and 2020, respectively, outdating the results in [

23]. R1336mzz (Z) belongs to the hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) class of organic working fluids. HFO represents an environmentally friendly alternative to hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which have a high Global Warming Potential (GWP). R1336mzz (Z) has zero Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP) and low Global Warming Potential (ODP = 0, GWP = 2) [

28]. It is non-flammable, has lower toxicity, reduced lifespan into the atmosphere and high chemical stability at high temperature [

29]. Due to its great environmental and thermal properties, R1336mzz (Z) is one of the most highly recommended working fluids for ORC systems [

30]. A disadvantage of R1336mzz (Z) is that it can decompose and form hydrogen fluoride (HF) if exposed to temperatures around 300 °C for more than 24 h [

31]. HF is an extremely toxic and corrosive gas that, when in contact with moisture, forms hydrofluoric acid, a substance dangerous to the respiratory system, skin, and eyes.

R1233zd (E) belongs to the hydro-chloro-fluoro-olefins (HCFO) family and has ODP = 0.00034 and GWP = 1. It is non-flammable and has lower toxicity. R601a (isopentane, C5H12) is a hydrocarbon with ODP = 0 and GWP = 3. It has high flammability and may affect the central nervous system when inhaled in high concentration.

3. Results and Discussion

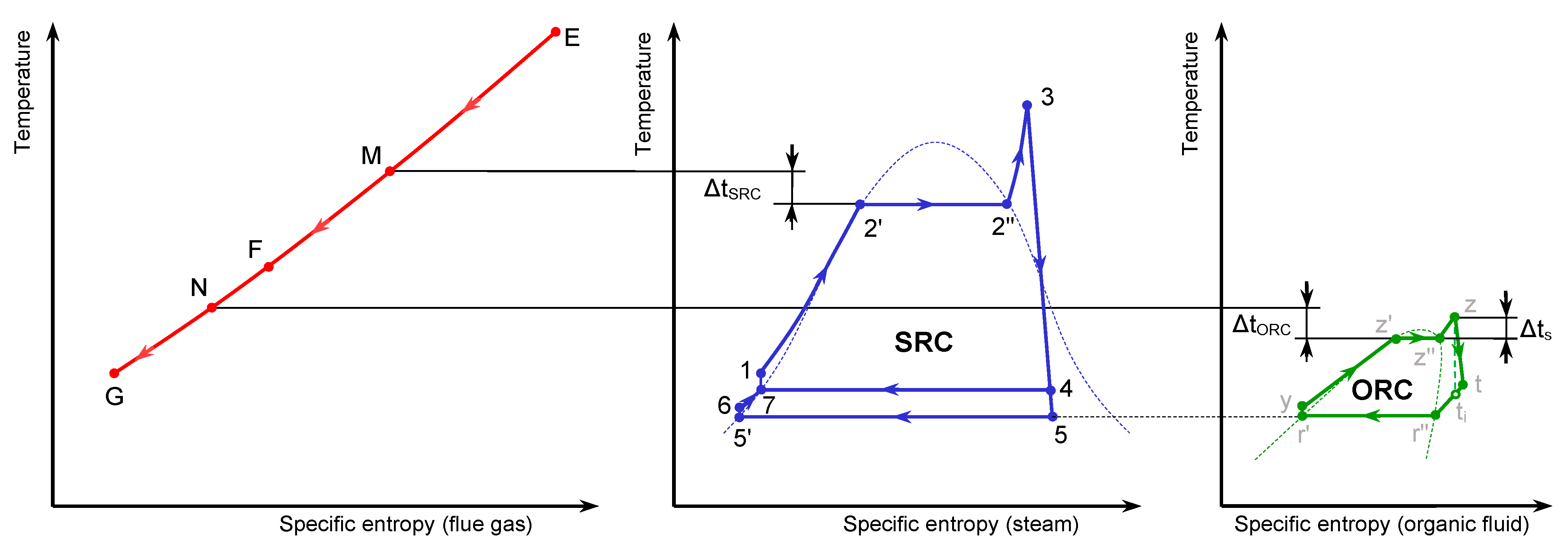

To validate the calculation method for the performance parameters of the flue gas and gas turbine, the calculated parameters of the Solar Centaur 40 gas turbine were compared with the values from the gas turbine’s specifications. The calculations were performed considering the data provided by the manufacturer, as presented in

Table 1.

The reference conditions for calculating the heating values were assumed to be 1.013 bar and 0 °C. The volumetric composition of the natural gas is CH4 = 95.17%, C2H6 = 0.69%, C3H8 = 0.69%, C4H10 = 0.53%, C5H12 = 1.59%, and N2 = 1.33%. Accordingly, the lower heating value of the fuel is LHV = 36339 kJ/Nm3. The higher heating value is HHV = 40336 kJ/Nm3. The carbon content is gC = 0.743 kg carbon/kg fuel. The density is ρNG = 0.747 kg/Nm3, and the stoichiometric air–fuel ratio is AFR = 16.82 kg air/kg fuel.

The calculated values of the Solar Centaur 40 gas turbine’s performance parameters, as well as design values from the producer’s specifications, are presented in

Table 2. The close agreement of values indicates that the calculation procedure is valid.

Furthermore, the performance parameters of the CCPP were calculated. This requires the HRSG gas exhaust temperature and steam mass flow rate to be known. Both parameters were determined from the thermal balance of the HRSG by imposing a certain value of the pinch point temperature difference in the SRC system. The calculations were performed assuming the parameters presented in

Table 3, where subscripts have the same definition as the notations used in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. In addition, a flue gas pressure drop of 1% was considered in the HRSG, a steam pressure drop of 5% was considered in the superheater, a water pressure drop of 5% was considered in the economizer, and a heat exchanger efficiency of 0.98 was used. These values are consistent with the values in [

39].

The values of the condensing pressure and extracted steam pressure in the SRC unit (

Table 3) were set in accordance with the recommendations from [

41,

43]. The corresponding steam condensing temperature is

t5 = 32.9 °C while the temperature of the saturated water delivered by the deaerator is

t7 = 104.8 °C. The condensing temperature of the organic working fluid in the ORC plant (

tr’,

tr”) was also assumed 32.9 °C facilitating the use of a single cooling tower for both SRC unit and ORC unit. The superheated steam pressure value corresponds to a boiler model, widespread in Romania, namely CR16 [

43].

Isentropic efficiency of the steam turbine was assumed in accordance with [

44], where values in the range 0.85–0.95 are recommended. For the pinch point temperature difference in SRC system, usually of 11–28 °C [

45], was assumed the value from [

46]. In similar approach, the same value was considered for the minimum accepted pinch point temperature difference in ORC system, as indicated below.

The results of the performance analysis of the CCPP are presented in

Table 4. Due to the slightly higher backpressure caused by the presence of the HRSG and HRVG downstream of the gas turbine, the performance of this turbine is slightly lower in combined cycle operation than in simple cycle operation.

The ORC system’s performance was analyzed assuming the parameters in

Table 5, where subscripts have the same definition as the notations in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Only the non-condensing mode was considered for O-CCPP operation, so the HRVG exhaust flue gas temperature was admitted, accordingly, within the recommended limits for gaseous sulfur-free fuels [

41]. The study in [

47] on exergetic optimization of a power trigeneration system with a bottoming ORC unit considers the same value of the flue gas temperature. The generator efficiency was assumed in accordance with [

37].

The flue gas pressure drop in the HRVG was 1%. According to the condensing temperature indicated in

Table 5, the condensing pressure was

pr’ = 0.992 bar.

The main goal of the ORC system analysis was to study its performance and to find optimum values of the following parameters: the working fluid degree of superheat Δts = tz − tz”, the pinch point temperature difference, and the vaporization pressure.

Investigation was performed using two different approaches.

In the first case (first approach), the vaporization pressure was imposed as a constant. The value used in the calculations was

pvap =

pz’ =

pz” = 8.23 bar (

tvap = 106.7 °C), which was obtained by imposing the lowest admitted values for two temperature differences, namely HRVG terminal temperature difference

tF −

tz = 40 °C (out of which the maximum admitted superheated vapor temperature was

tz max = 146.5 °C) and pinch point Δ

tORC = 25 °C, respectively. Lowest admitted HRVG terminal temperature difference is within the recommended range for flue gas-vapor heat exchangers avoiding a size excessively large [

39].

In the second case (second approach), the pinch point temperature difference was set as a constant (the minimum and maximum accepted values are ΔtORC = 25 °C and ΔtORC = 40 °C, respectively), so the vaporization pressure in the ORC was obtained from the thermal balance of the HRVG.

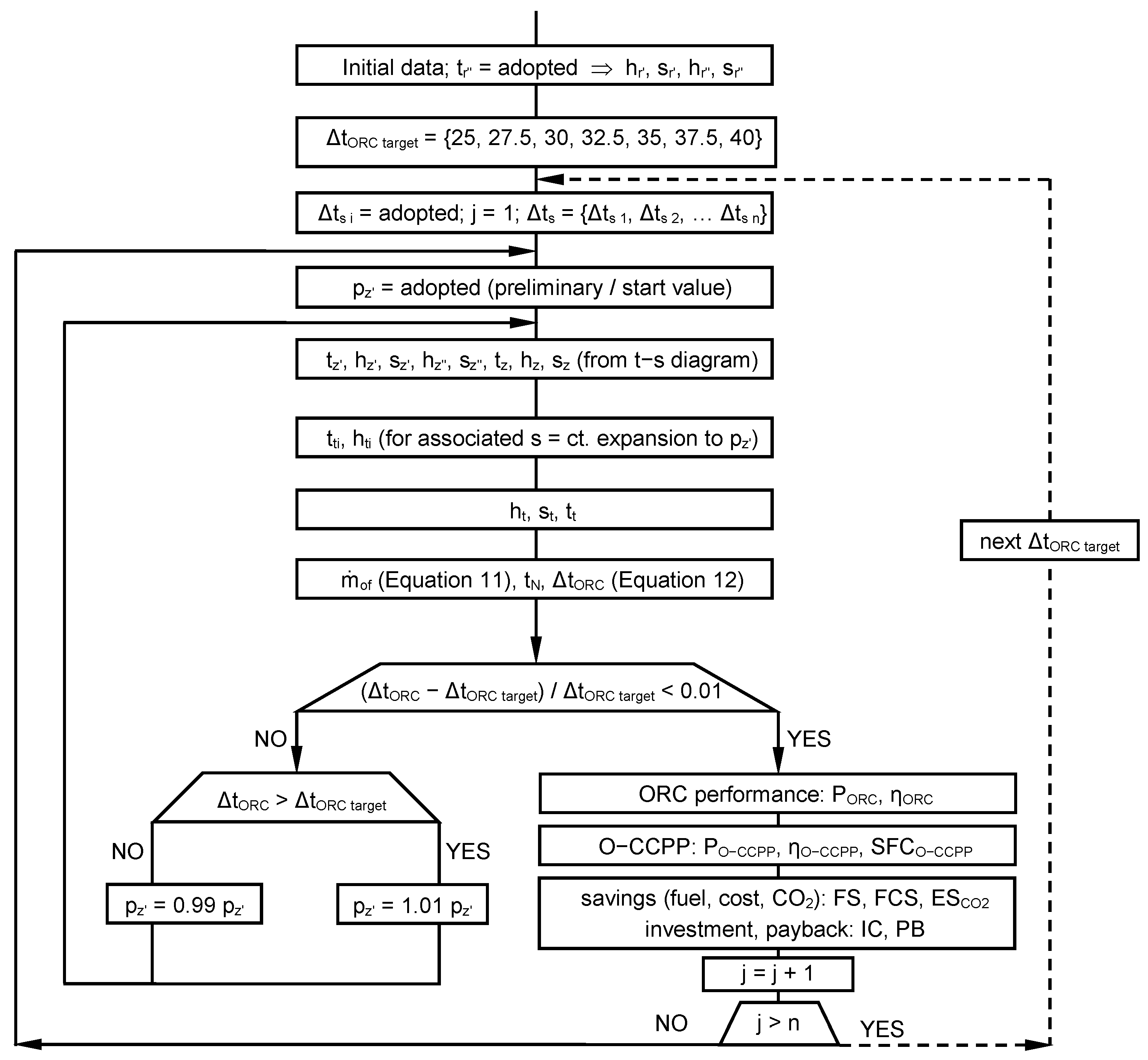

A flowchart of the calculation algorithm in the second case, which is more complex, is presented in

Figure 3.

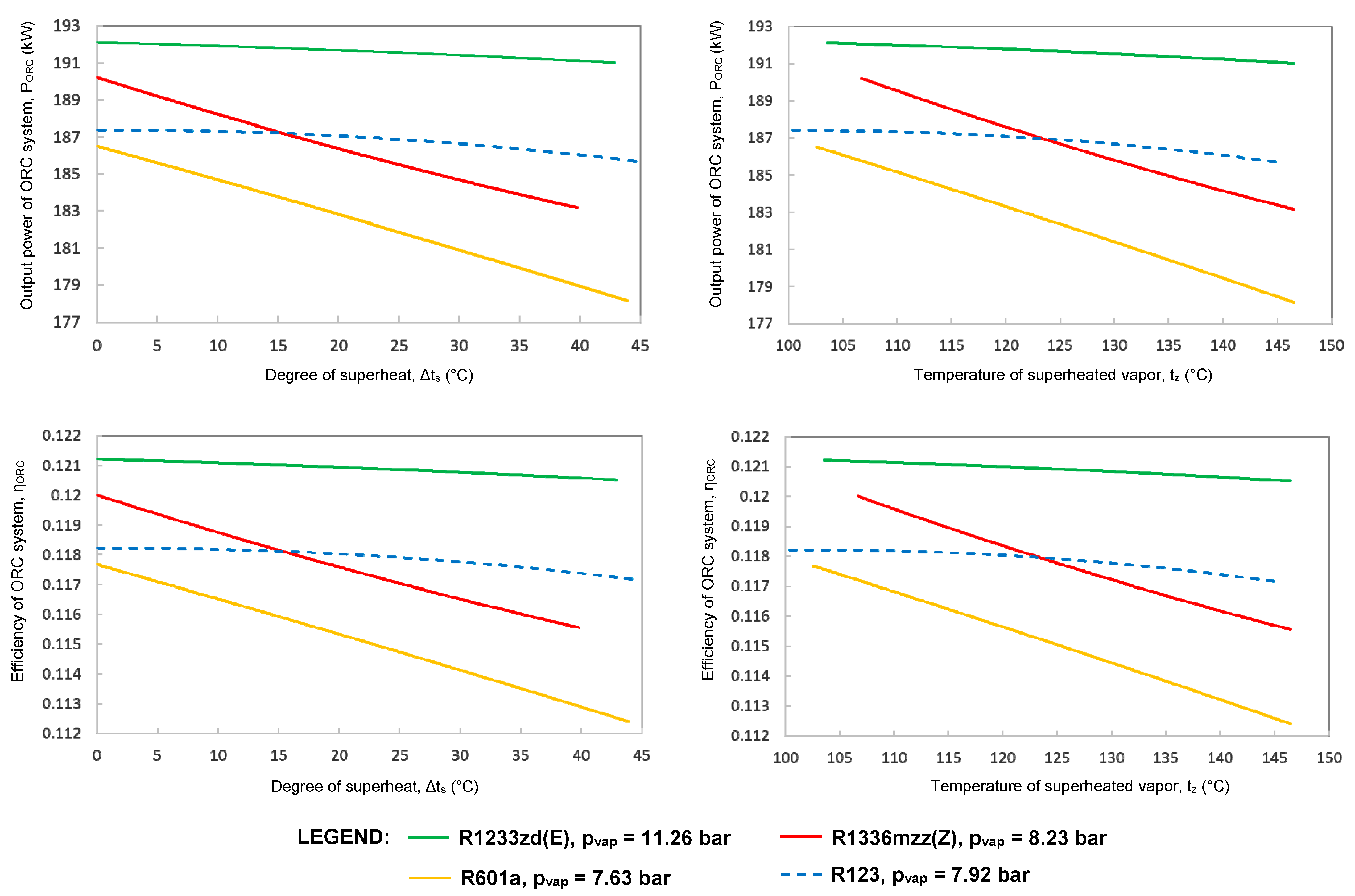

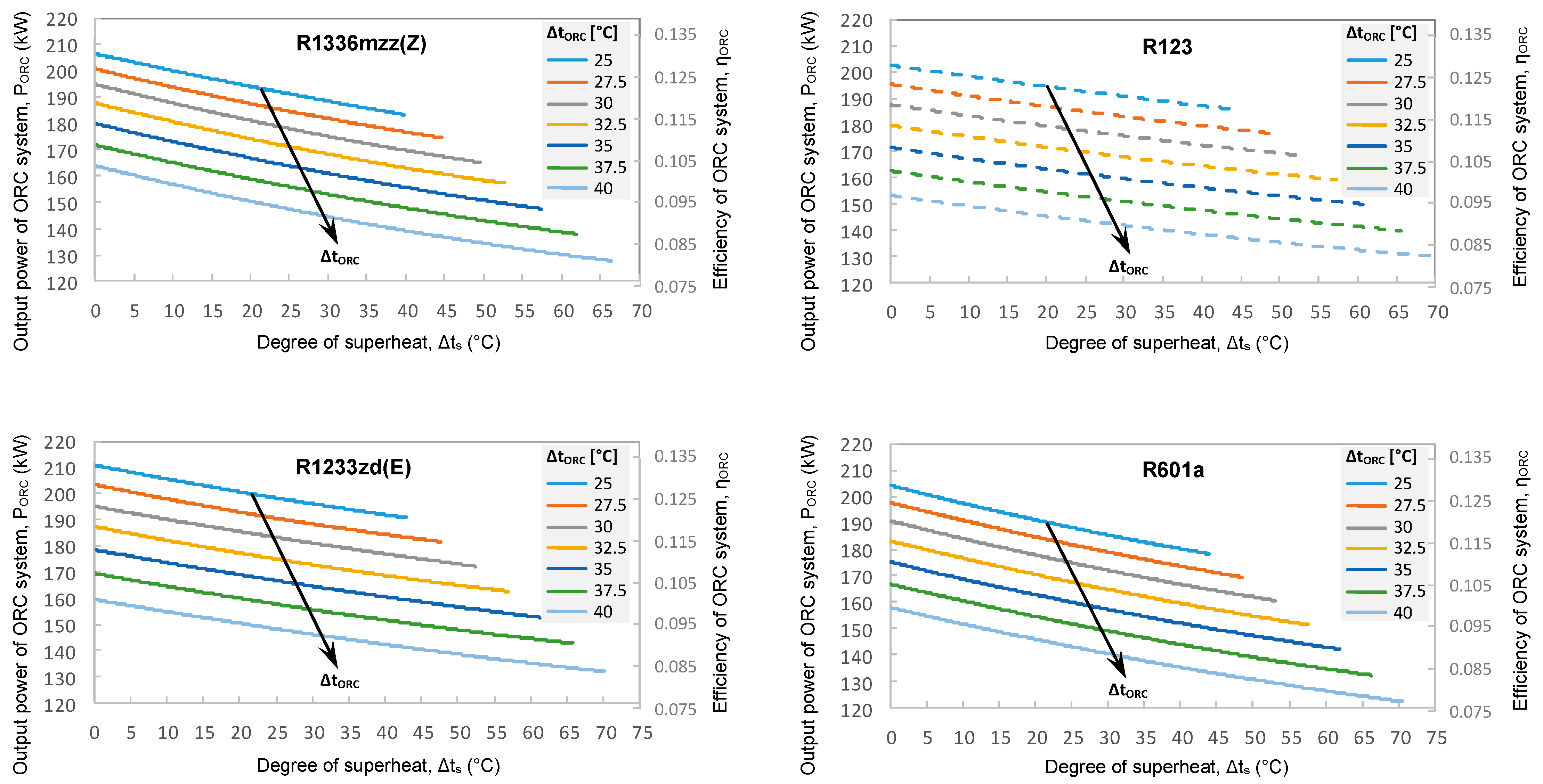

The dependences of the output power and efficiency of the ORC system operating with R1336mzz (Z), R1233zd (E), and R601a on the degree of superheat, in the first case, are presented in

Figure 4. The dashed blue curves are used for reference and comparison and correspond to the phased-out organic fluid R123, which was used in the previous study of the authors [

23]. The vaporization pressure and temperature of R123 are 7.92 bar and 100.4 °C, respectively, when

tz max = 146.5 °C and Δ

tORC = 25 °C (conditions in the first case).

It can be observed that the ORC system’s performance diminishes with the increase in the degree of superheat and, consequently, with superheated vapor temperature. The highest performance is achieved with R1233zd (E) and the lowest with R601a. Both output power and efficiency decrease by roughly 0.6% when R1233zd (E) is used (output power decreases from 192.1 kW to 191.0 kW, and efficiency decreases from 0.1212 to 0.1205) upon varying the degree of superheat from 0 to 42.9 °C.

Output power and efficiency decrease by roughly 3.5% when R1336mzz (Z) is used (output power, from 190.2 kW to 183.2 kW, and efficiency from 0.1200 to 0.1155) upon varying the degree of superheat from 0 to 39.8 °C.

The performance is lower in the case of R123 when the degree of superheat is zero (output power of 185.7 kW and efficiency of 0.1171). The performance for R123 becomes higher than for R1336mzz (Z) at a higher degree of superheat due to the different slopes of the curves.

The decrease in the ORC system’s performance with the increase in the degree of superheat in the first case (

pvap = const.) is due to the consequent decrease in the organic fluid mass flow rate. This is explained by Equation (11). It should be noticed that

hz is the only variable in this equation (

,

hF,

hG, and

hy are constants in current assumptions) and is inversely related to

. Obviously, the enthalpy

hz increases with the superheated vapor temperature

tz and, consequently, with the degree of superheat Δ

ts. Hence, the higher the

tz and Δ

ts, the lower

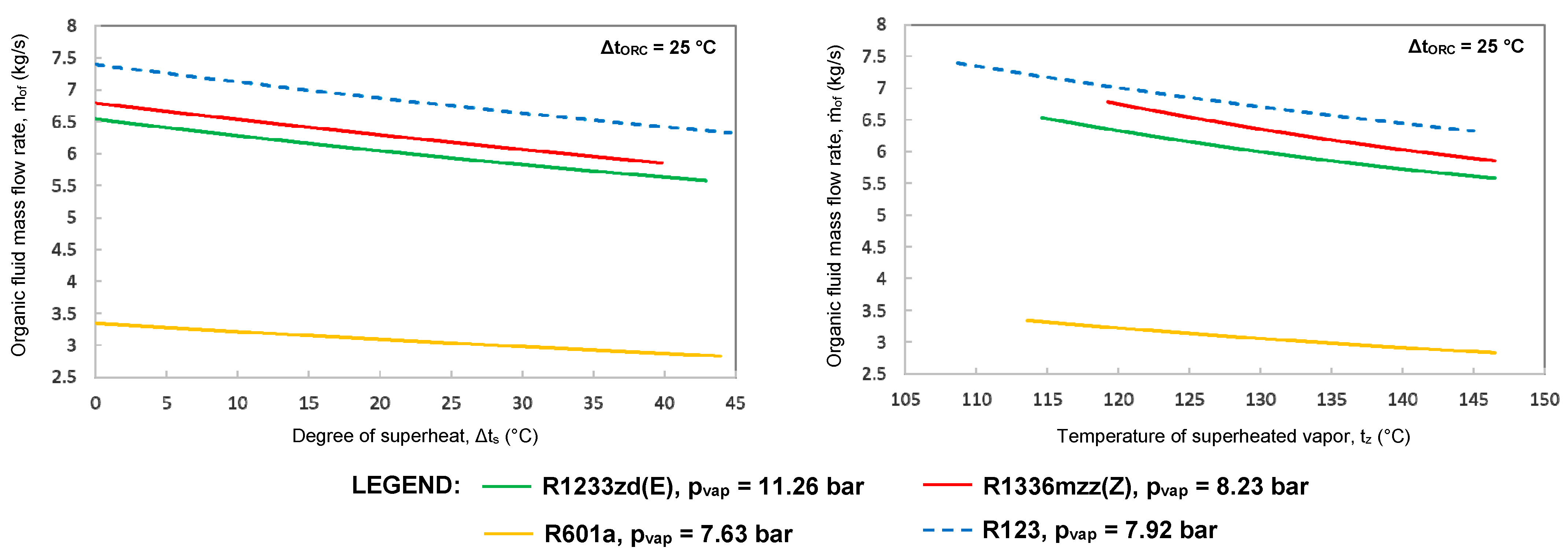

and the lower the ORC performance. As shown in

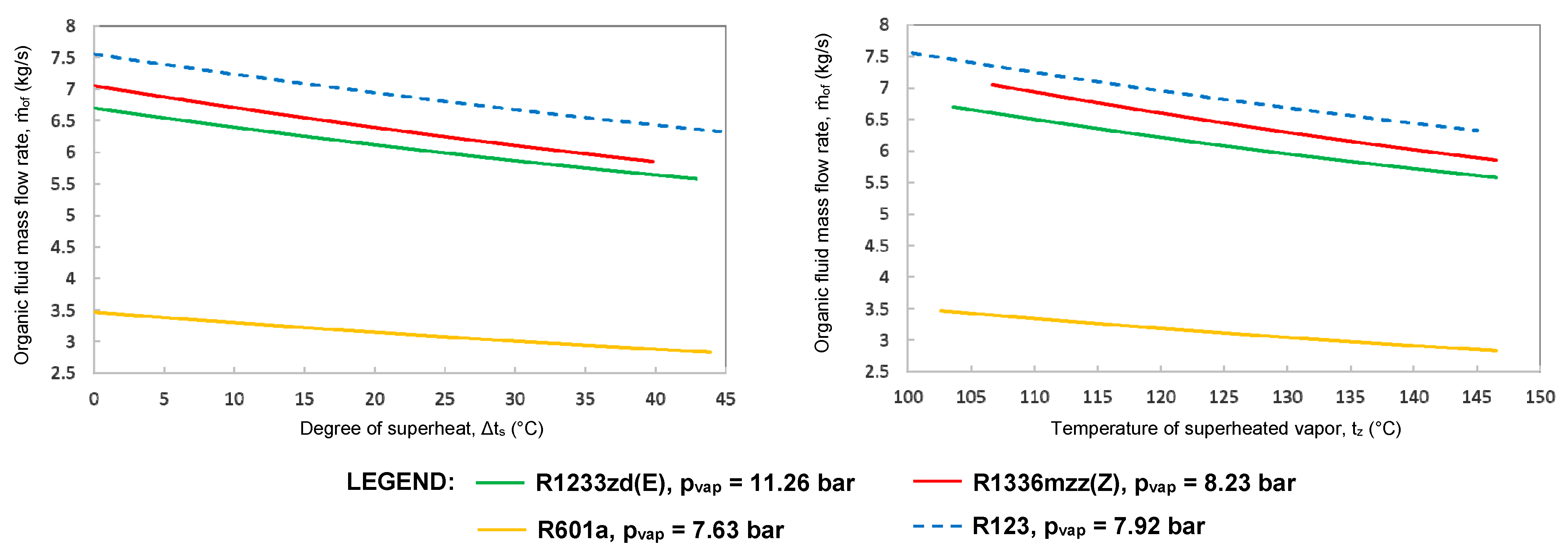

Figure 5, the mass flow rates of R1336mzz (Z), R1233zd (E), and R601a decrease with 17.0% (from 7.051 kg/s to 5.855 kg/s), 16.8% (from 6.701 kg/s to 5.577 kg/s), and 18.3% (from 3.467 kg/s to 2.833 kg/s), respectively, when

tz and Δ

ts vary from minimum to maximum values. The mass flow rate of the reference working fluid R123 decreases with 16.3%, from 7.555 kg/s to 6.324 kg/s.

The dependences of the output power and the efficiency of the ORC system on the degree of superheat in the second case are presented in

Figure 6. The dependences were determined at pinch point temperature differences between 25 and 40 °C. The organic fluid R123 was also used for reference. The curves show that the ORC system with R1233zd (E) has the highest performance at zero degrees of superheat not only for Δ

tORC = 25 °C but also for Δ

tORC = 27.5 °C and Δ

tORC = 30 °C, while for Δ

tORC ≥ 32.5 °C, the highest performance is achieved with R1336mzz (Z).

The performance of the ORC system diminishes when the parameter Δ

tORC increases. Consequently, the optimum value of Δ

tORC is the minimum one, namely 25 °C. Increasing the performance by reducing the pinch point temperature difference is typical for the waste heat recovery boilers (e.g., [

41,

44]). The present analysis was focused on quantifying this effect. The minimum admitted value of the pinch point temperature difference in power plants is decided by economic considerations: the lower the pinch point temperature difference, the larger the heat exchanger size and cost.

Figure 6 also illustrates that the decrease in the output power and efficiency of the ORC system as the degree of superheat increases occurs for all values of Δ

tORC. When Δ

tORC has the optimum value (25 °C), the performance of the ORC system with R1233zd (E), R1336mzz (Z), and R601a diminishes by 9.4%, 11.3%, and 12.8%, respectively, when the degree of superheat increases from 0 to maximum. Thus, the output power decreases from 210.8 kW to 191.0 kW for R1233zd (E), from 206.6 kW to 183.2 kW for R1336mzz (Z), and from 204.3 kW to 178.1 kW for R601a. The efficiency varies from 0.1330 to 0.1205, from 0.1303 to 0.1156, and from 0.1289 to 0.1124, respectively. The vaporization pressure varies between 14.15 bar and 11.26 bar in the case of R1233zd (E), 10.83 bar and 8.23 bar in the case of R1336mzz (Z), and between 9.60 bar and 7.63 bar in the case of R601a.

As shown in

Figure 7, the mass flow rates of R1233zd (E), R1336mzz (Z), and R601a decrease with 14.8% (from 6.543 kg/s to 5.577 kg/s), 13.6% (from 6.774 kg/s to 5.855 kg/s), and 15.2% (from 3.342 kg/s to 2.833 kg/s), respectively, when

tz and Δ

ts vary from minimum to maximum values. The mass flow rate of R123 varies with 14.5% (from 7.396 kg/s to 6.324 kg/s).

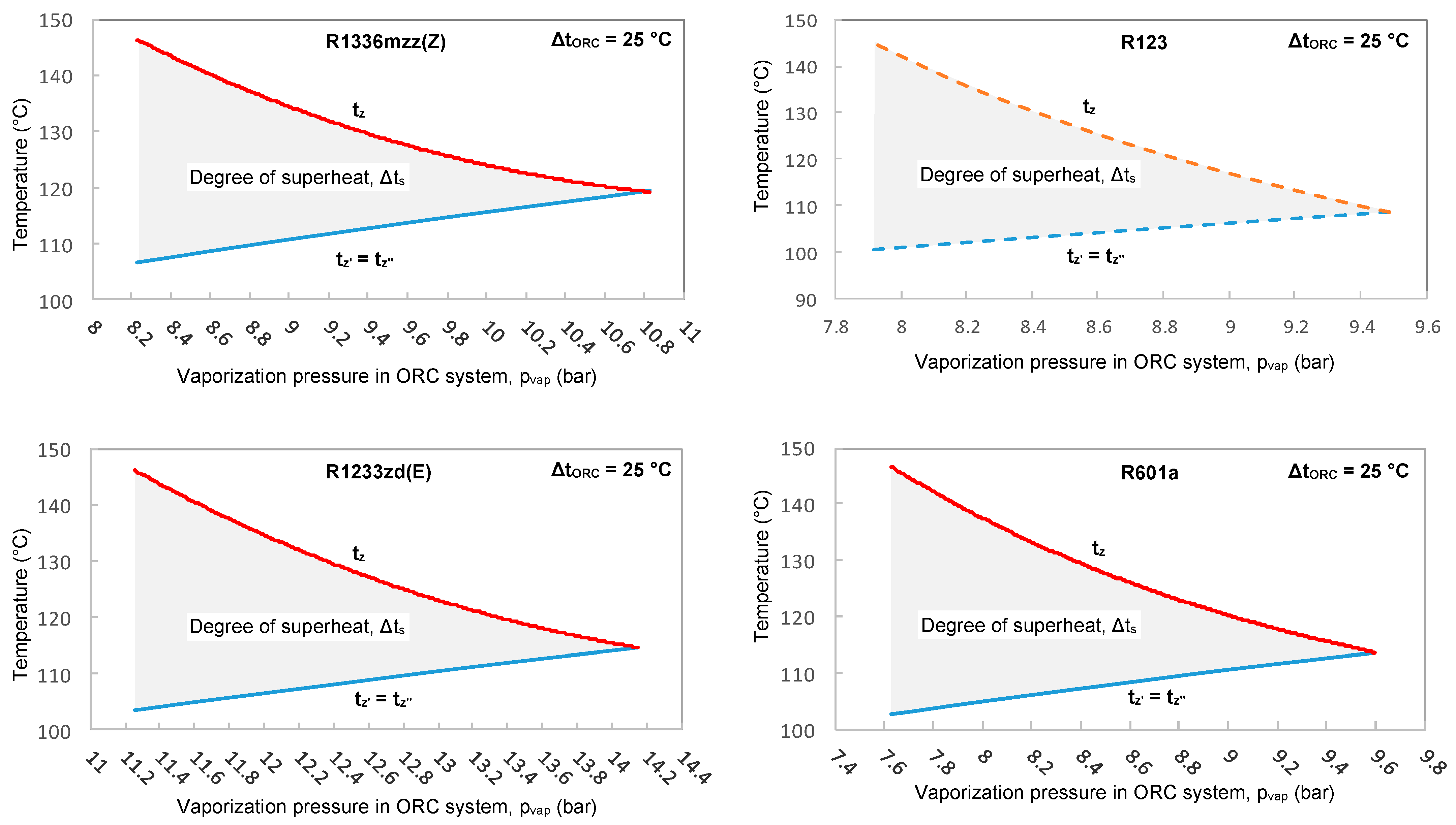

The dependences of the vaporization temperature and superheated vapor temperature on the vaporization pressure in the second case are presented in

Figure 8 for the optimum pinch point temperature difference of Δ

tORC = 25 °C. The difference in these two temperatures gives the degree of superheat. The figure shows that the lower the degree of superheat, the higher the vaporization pressure. So, the lower degree of superheat implies higher vaporization pressure besides higher organic fluid mass flow rate and higher performance. The higher performance reduces the energy production costs, so that the higher vaporization pressure, the lower the energy production costs. This was also reported in [

1], where the ORC system operates using waste heat from a marine diesel engine. In addition, higher vaporization pressure means lower latent heat of vaporization, which is linked to the size of the evaporator and, consequently, to the investment costs.

For the optimum pinch point temperature difference, ΔtORC = 25 °C, the vaporization pressure increases from 8.23 to 10.83 bar in the case of R1336mzz (Z), from 11.26 to 14.15 in the case of R1233zd (E), and from 7.63 to 9.60 bar in the case of R601a upon varying the degree of superheat/temperature of superheated vapor from maximum to minimum. The variation is from 7.92 to 9.49 in the case of the reference working fluid R123.

The low efficiency of the ORC system, covering the range 0.1205–0.1330 for R1233zd (E), 0.1156–0.1303 for R1336mzz (Z), 0.1124–0.1289 for R601a, and 0.1171–0.1280 for R123 in the two analyzed cases, is caused by the low temperature difference between the two heat sources. (The temperature of the HRVG inlet flue gas—the hot source—is

tF = 186.5 °C, and the temperature of ambient air—the cold source—is 15 °C.) Obviously, the efficiency improves when the flue gas temperature entering HRVG is higher. The study in [

48], indicates an increase from roughly 0.121 to 0.161 of the efficiency of an ORC unit with R41 organic fluid when the flue gas temperature entering HRVG increases from 150 °C to 200 °C. An increase in the performance can be achieved by using an ultra-critical ORC system instead of a subcritical ORC system, as shown in [

47]. This study estimates a maximum increase of 19% (from 2322 kW to 2769 kW) when R1234yf is used as working fluid in the ORC system. Another solution is to use the partially evaporated ORC systems with dry working fluids, which can provide up to 4% more efficiency than basic ORC or superheated ORCs [

2,

3].

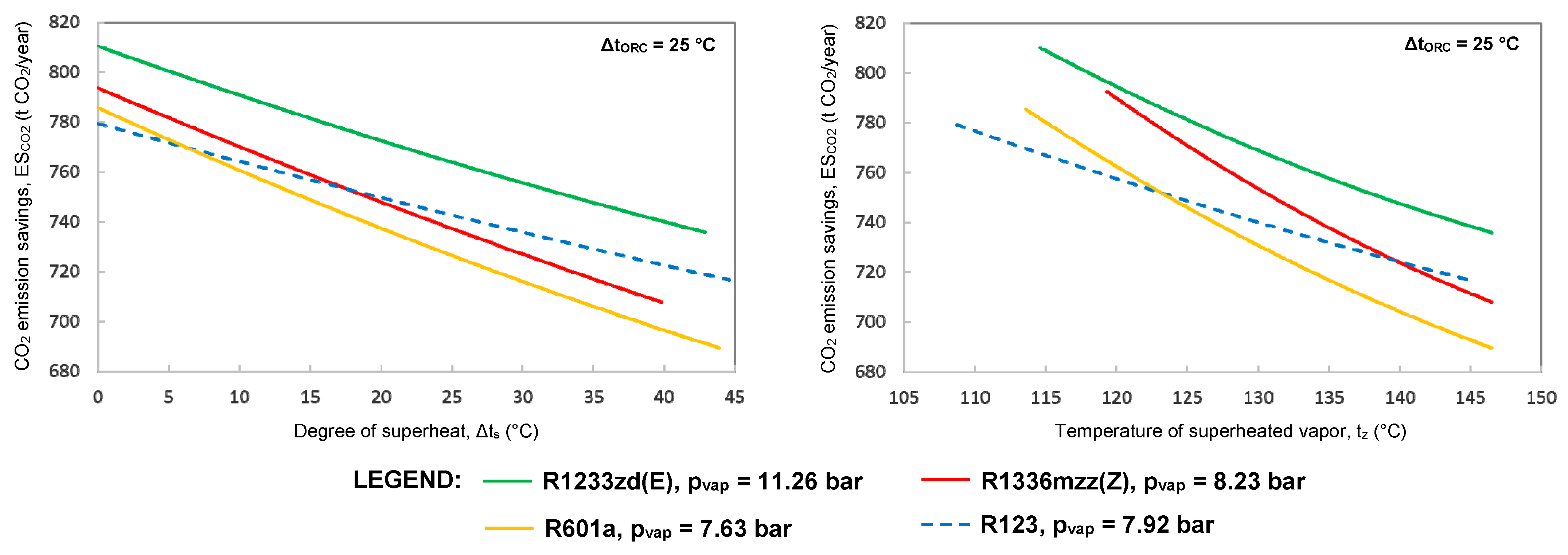

Figure 9 illustrates that maximum CO

2 emission savings are obtained for Δ

tORC = 25 °C and without superheating (the optimum value) when R1233zd (E) is used as working fluid. This correlates with

Figure 6, which shows that R1233zd (E) offers the highest performance in the same conditions. CO

2 emission savings decrease from 809.9 to 736.9 t CO

2/year when

tz and Δ

ts vary from minimum to maximum values.

For all the analyzed working fluids, maximum performance of the ORC system is achieved in the second case (where Δ

tORC = 25 °C) in the absence of superheating. This situation is also convenient from a construction point of view since the HRVG and condenser have smaller heat exchange surfaces. The most convenient working fluid is R1233zd (E), which offers the highest output power and efficiency of the ORC system in these conditions, namely 210.8 kW and 0.1330, respectively. Accordingly, calculations for the O-CCPP specific parameters were performed assuming these optimum conditions: R1233zd (E) as working fluid, Δ

tORC = 25 °C, and no superheating. The results are presented in

Table 6.

The annual fuel saving was calculated by considering the number of operating hours in one year (

τop = 8100 h). According to [

49], this value was assumed as 8760 −

τms, where 8760 is the number of hours in one year (365 days × 24 h/day) and

τms = 320–720 h is the number of hours for maintenance and service.

By using the ORC system, the efficiency of the power plant increases from 0.411 to 0.425 (see

Table 4 and

Table 6), which results in a benefit of 0.014 (1.4%). The output power delivered by the ORC system is 210.8 kW, which represents 4.2% from the output power of O-CCPP. A similar configuration of subcritical ORC system is analyzed in [

47]. In this case, the ORC turbine delivers 2.9 MW when R152a is used as working fluid while the gas turbine and steam turbine generate 150 MW and 85.6 MW, respectively. Thus, in [

47], the ORC system contributes with 1.2% on the output power generated by the power plant.

Specific fuel consumption is reduced from 0.2433 Nm

3/kWh to 0.2332 Nm

3/kWh. This difference is apparently negligible; however, it generates impressive savings in full-load operations. For example, the annual fuel savings are about 398,000 Nm

3/year, which implies roughly 810 t less CO

2 emissions (see

Table 6) and annual cost savings of roughly 269,000 EUR/year. The annual fuel cost savings are calculated by considering the natural gas price to be

NGP = 60.37 EUR/MWh (in Romania, July 2025, with all taxes included). This price was derived by averaging the prices for non-household consumers of the largest natural gas providers across all 42 counties of the country, which are listed on the official website of the Romanian Energy Regulatory Authority.

According to [

50,

51], the estimated value of SPC for ORC systems operating at similar temperatures of the waste flue gas ranges between 3500 and 5000 EUR/kWe. The investment cost for the O-CCPP with optimum parameters is between EUR 0.69 and 0.98 million in these conditions. Considering the average electricity price EP = 0.280 EUR/kWh (in Romania, July 2025, with all taxes included) and the number of operating hours in one year

τop = 8100 h, the payback period for the investment in ORC system is 1.6 to 2.3 years.

4. Conclusions

The calculated performance parameters were close to the specifications of the Solar Centaur 40 gas turbine, thus proving the method used to calculate the temperatures and enthalpies of the flue gas, as well as the performance parameters of the gas turbine, as accurate.

It was found that both the ORC system’s efficiency and output power diminish with the degree of superheat in both analyzed cases (constant vaporization pressure and constant pinch point temperature difference, respectively), which means that superheating is not beneficial. This is due to the decrease in the organic fluid mass flow rate with the increase in the degree of superheat.

The mass flow rate of organic fluid increases with the decrease in the degree of superheat and with the increase in the vaporization pressure when the pinch point temperature difference is constant.

The most convenient of the three analyzed working fluids is R1233zd (E), which offers the highest performance. At constant vaporization pressure of 11.26 bar, the output power of the ORC system operating with R1233zd (E) diminishes from 192.1 kW to 191.0 kW and efficiency decreases from 0.1212 to 0.1205 when the degree of superheat increases from 0 to 42.9 °C. The mass flow rate of organic fluid decreases from 6.701 kg/s to 5.577 kg/s.

The numerical simulation, based on the proposed mathematical model, allowed for the optimization of the ORC system regarding maximum efficiency. The maximum efficiency and maximum output power of the ORC system are achieved in the study when the pinch point temperature difference has the lowest admissible value of 25 °C, in the absence of superheating, at maximum vaporization pressure. In the case of R1233zd (E), the maximum efficiency is 0.1330, maximum output power is 210.8 kW, and the maximum vaporization pressure is 14.15 bar. This led to an improvement in the O-CCPP’s efficiency of 0.014, from 0.411 to 0.425.

The absence of the superheater and the maximum vaporization pressure at maximum performance are convenient from technical and economic considerations leading to the reduction in the HRVG’s size.

The calculated maximum performance of the ORC system is apparently small, which is due to the small temperature difference between the two sources of heat in the system; however, the financial and environmental benefits are significant. The numerical analysis shows a reduction in annual fuel consumption of 398,185 Nm3/year under optimum conditions. This equates to an annual cost saving of 269,319 EUR/year, as well as a reduction in CO2 emissions of 809,900 kg CO2/year for the studied case.

Further research should focus on the scalability of the O-CCPP and on the optimization of the ORC system design by considering the various energy losses generated by each component. Detailed economic analysis including capital and operational expenditure for assessing the large-scale economic viability and for quantifying the potential financial benefits of implementing the ORC system should also be investigated.