Abstract

Masses of heavy baryons are calculated in the framework of the relativistic quark-diquark picture and QCD. The obtained results are in good agreement with available experimental data including recent measurements by the LHCb Collaboration. Possible quantum numbers of excited heavy baryon states are discussed.

1. Introduction

Recently, significant experimental progress has been achieved in studying heavy baryon spectroscopy. Many new heavy baryon states have been observed. The main contribution was made by the LHCb Collaboration. Thus, last year the amplitude analysis of the decay was performed in the region of the phase space containing resonant contributions which revealed three excited states and allowed precise measurement of their masses and decay widths [1]—the with the preferred spin ;—the new state with quantum numbers , its parity was measured relative to that of the ;—the with the most likely spin-parity assignment , but other solutions with spins from to were not excluded. Then five new, narrow excited states decaying to were observed [2]—the , , , , and . These states were later confirmed by Belle [3]. Soon the discovery of the long-awaited doubly charmed baryon was reported [4,5]. In 2018, the new resonance was observed as a peak in both the and invariant mass spectra [6]. The first observation of two structures , consistent with resonances in the final states and was reported by the LHCb [7] and two new resonances and were found in the system [8].

In this paper, we compare these new data with the predictions of the relativistic quark-diquark model of heavy baryons [9,10,11,12].

2. Relativistic Quark-Diquark Model of Heavy Baryons

Our approach is based on the relativistic quark-diquark picture and the quasipotential equation. The interaction of two quarks in a diquark and the quark-diquark interaction in a baryon are described by the diquark wave function of the bound quark-quark state and by the baryon wave function of the bound quark-diquark state respectively. These wave functions satisfy the relativistic quasipotential equation of the Schrödinger type [9,10]

where is the relativistic reduced mass, is the center-of-mass relative momentum squared on the mass shell, are the off-mass-shell relative momenta, and M is the bound state mass (diquark or baryon).

The kernel in Equation (1) is the quasipotential operator of the quark-quark or quark-diquark interaction, which is constructed with the help of the off-mass-shell scattering amplitude, projected onto the positive energy states. We assume that the effective interaction is the sum of the usual one-gluon exchange term and the mixture of long-range vector and scalar linear confining potentials, where the vector confining potential contains the Pauli term. The vertex of the diquark-gluon interaction takes into account the diquark internal structure and effectively smears the Coulomb-like interaction. The corresponding form factor is expressed as an overlap integral of the diquark wave functions. Explicit expressions for the quasipotentials of the quark-quark interaction in a diquark and quark-diquark interaction in a baryon can be found in Reference [11]. All parameters of the model were fixed previously from considerations of meson properties and are kept fixed in the baryon spectrum calculations.

The quark-diquark picture of heavy baryons reduces a very complicated relativistic three-body problem to a significantly simpler two step two-body calculation. First we determine the properties of diquarks. We consider a diquark to be a composite system. Thus diquark in our approach is not a point-like object. Its interaction with gluons is smeared by the form factor expressed through the overlap integral of diquark wave functions. These form factors enter the diquark-gluon interaction and effectively take diquark structure into account [11,12]. Note that the ground state diquark composed from quarks with different flavours can be both in scalar and axial vector state, while the ground state diquarks composed from quarks of the same flavour can be only in the axial vector state due to the Pauli principle. Solving the quasipotential equation numerically we calculate the masses, determine the diquark wave functions and use them for evaluation of the diquark form factors. Only ground-state scalar and axial vector diquarks are considered for heavy baryons. While both ground-state as well as orbital and radial excitations of heavy diquarks are necessary for doubly heavy baryons, since the lowest excitations of such baryons originate from the excitations of the doubly heavy diquark.

Next we calculate the masses of heavy baryons in the quark–diquark picture [11,12]. The heavy baryon is considered as a bound state of a heavy-quark and light-diquark. All excitations are assumed to occur between heavy quark and light diquark. On the other hand, the doubly heavy baryon is considered as a bound state of a light-quark and heavy-diquark. Both excitations in the quark-diquark system and excitations of the heavy diquark are taken into account. It is important to note that such approach predicts significantly less excited states of baryons compared to a genuine three-quark picture. We do not expand the potential of the quark–diquark interaction either in or in and treat both diquark and quark fully relativistically.

3. Masses of Heavy Baryons

The calculated masses of heavy baryons are given in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. In the first column we show the baryon total isospin I, spin J and parity P. The second column lists the quark-diquark state. The next three columns refer to the charm and the last three columns to the bottom baryons. There we first give our prediction for the mass, then available experimental data [13]—baryon status and measured mass. For the status of the state we use the Particle Data Group (PDG) [13] star notations. With the number of the stars it ranges from * meaning “Evidence of existence is poor”, to **** meaning “Existence is certain, and properties are at least fairly explored”. The combined experimental error values are taken form PDGLive. The charm and bottom baryon states recently discovered by the LHCb Collaboration [1,2,4,5,6,7] are marked as new.

Table 1.

Masses of the () heavy baryons (in MeV).

Table 2.

Masses of the () heavy baryons (in MeV).

Table 3.

Masses of the () heavy baryons with the scalar diquark (in MeV).

Table 4.

Masses of the () heavy baryons with the axial vector diquark (in MeV).

Table 5.

Masses of the () heavy baryons (in MeV).

Note that the orbitally excited states of heavy baryons () containing the axial vector diquark and having the same total angular momentum J and parity P but different light diquark total momentum mix due to the presence of the spin-orbit () and tensor interactions [11]. Two mixed states for each and emerge. Thus there are two states for and for , two states for and for in Table 2, Table 4 and Table 5.

From Table 1 and Table 2 we see that the (or ), if it is indeed the state, can be interpreted in our model as the first radial () excitation of the . If instead it is the state, then it can be identified as its first orbital excitation () with (see Table 2). The baryon corresponds to the second orbital excitation () with in accord with the LHCb analysis [1]. The other charmed baryon, denoted as , probably has , since it was discovered in the mass spectrum and not observed in channel, but is not ruled out [13]. If it is really the state, then it could be both an orbitally and radially excited () state with , whose mass is predicted to be about 40 MeV heavier. A better agreement with experiment (within few MeV) is achieved, if the is interpreted as the first radial excitation () of the with . The can be identified with one of the first orbital () excitations of the with or which have very close masses compatible with experimental value within errors (see Table 2). The new state with quantum numbers [1] can be well interpreted as second orbital excitation ( state). In the bottom sector the and correspond to the first orbitally excited () states with and , respectively. The new state [7] can be the first orbital excitation () with quantum numbers , while and can be states with and , respectively.

In the baryon sector, as we see from Table 3 and Table 4, the and can be assigned to the first orbital () excitations of the containing a scalar diquark with and , respectively. On the other hand, the charmed baryon can be considered as either the , or state (all these states are predicted to have close masses) corresponding to the first orbital () excitations of the with an axial vector diquark. While the can be viewed as the first radial () excitation with of the . The and baryons can be interpreted as a second orbital () excitations of the containing a scalar diquark with and , and the can be viewed as the corresponding () excitation of the with . The recently observed excited bottom baryon [6] can be one of the first radially excited states () of the baryon with the axial vector diquark and quantum numbers , , which are predicted to have very close masses.

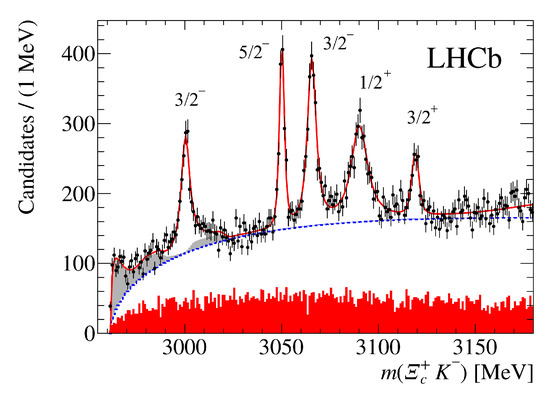

Masses of the and baryons are given in Table 5. The ground state () masses were predicted [9,10] before experimental discovery and agree well with measured values. Recently the LHCb observed [2] five new, narrow excited are also in accord with our predictions. Three lighter states , and are well described as first orbital () excitations with , and , respectively. These states are expected to be narrow. The remaining states with are expected to be broad and thus can escape detection. The small peak in the low end of mass distribution (see Figure 1) can correspond to state with the predicted mass 2966 MeV (see Table 5). The remaining two heavier states and are naturally described as first radial () excitations with quantum numbers and , respectively. Their predicted masses coincide with the measured ones within a few MeV. The proposed assignment of spins and parities of excited states observed by the LHCb Collaboration is given in Figure 1. In Table 6 we compare different quark model (QM), QCD sum rules (QCD SR), lattice QCD predictions and available experimental data for the masses of the states.

Figure 1.

Proposed assignment of spins and parities of excited states observed by LHCb Collaboration.

Table 6.

Comparison of theoretical predictions for the masses of the states (in MeV).

4. Doubly Heavy Baryons

Mass spectra of doubly heavy baryons were calculated in the light-quark–heavy-diquark picture in Reference [12]. The light quark was treated completely relativistically, while the expansion in the inverse heavy quark mass was used. Table 7 shows the mass spectrum. Excitaions inside doubly heavy diquark and light-quark–heavy-diquark bound systems are taken into account. We use the notations , where we first show the radial quantum number of the diquark () and its orbital momentum by a capital letter (), then the radial quantum number of the light quark () and its orbital momentum by a lowercase letter (), and at the end the total angular momentum J and parity P of the baryon. In Table 8 we compare different theoretical predictions for the ground state masses of the doubly heavy baryons. Our prediction (2002) for the mass of the baryon [12] excellently agrees with its mass recently measured (2017) by the LHCb Collaboration [4,5]:

Table 7.

Mass spectrum of baryons (in MeV).

Table 8.

Mass spectrum of ground states of doubly heavy baryons (in MeV). denotes the diquark in the axial vector state and denotes diquark in the scalar state.

5. Conclusions

Recent observations of excited charm and bottom baryons confirm predictions of the relativistic quark–diquark model of heavy baryons [9,10,11]. The new state is in accordance with the predicted - state with . The experimentally preferred quantum numbers of agree with our assignment of this state to - state with . The and are well described as the first orbitally excited () states with and , respectively. The new state can be the first orbital excitation () with quantum numbers . The recently observed excited bottom baryon can be one of the first radially excited states () of the baryon with the axial vector diquark and quantum numbers , , which are predicted to have very close masses. Observation of five new narrow states in the mass range 3000-3200 MeV agrees with our prediction of orbitally excited -states and radially excited -states in this mass region: , , can be -states with while and states are most likely the first radially excited states with .

In the doubly heavy baryon sector, the mass of the recently observed baryon is in excellent agreement with our prediction made more than 15 years ago [12]. Masses of ground state doubly charm baryons are predicted to be in 3.5–3.9 GeV range. Masses of ground state doubly bottom baryons are predicted to be in the 10.1–10.5 GeV range. Masses of ground state bottom-charm baryons are predicted to be in the 6.8–7.2 GeV range. Rich spectra of narrow excited states below the strong decay thresholds are expected. We strongly encourage experimenters to search for new heavy baryons and especially for doubly heavy baryons.

Author Contributions

Investigation, R.N.F. and V.O.G., Writing—original draft, R.N.F. and V.O.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russian Federation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to D. Ebert, J. Körner and M. Ivanov for valuable discussions. We thank the organizers of the Helmholtz International Summer School “Quantum Field Theory at the Limits: From Strong Fields to Heavy Quarks” for the invitation to participate in such a pleasant and productive meeting.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Study of the D0p amplitude in → D0pπ− decays. JHEP 2017, 1705, 030. [Google Scholar]

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Observation of five new narrow states decaying to . Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 118, 182001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yelton, J.; et al.; [Belle Collaboration] Observation of Excited Ωc Charmed Baryons in e+e− Collisions. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 051102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Observation of the doubly charmed baryon . Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, 119, 112001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Precision measurement of the mass. JHEP 2020, 2002, 049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Observation of a new resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 072002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Observation of two resonances in the systems and precise measurement of and properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaij, R.; et al.; [LHCb Collaboration] Observation of New Resonances in the System. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 152001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D.; Faustov, R.N.; Galkin, V.O. Masses of heavy baryons in the relativistic quark model. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 034026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.; Faustov, R.N.; Galkin, V.O. Masses of excited heavy baryons in the relativistic quark model. Phys. Lett. B 2008, 659, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.; Faustov, R.N.; Galkin, V.O. Spectroscopy and Regge trajectories of heavy baryons in the relativistic quark-diquark picture. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 014025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.; Faustov, R.N.; Galkin, V.O.; Martynenko, A.P. Mass spectra of doubly heavy baryons in the relativistic quark model. Phys. Rev. D 2002, 66, 014008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabashi, M.; et al.; [Particle Data Group] Review of particle physics. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 030001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.M.; Pervin, M. Heavy baryons in a quark model. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2008, 23, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Z.; Thakkar, K.; Rai, A.K.; Vinodkumar, P.C. Mass spectra and Regge trajectories of , , , and baryons. Chin. Phys. C 2016, 40, 123102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rubio, P.; Collins, S.; Bali, G.S. Charmed baryon spectroscopy and light flavor symmetry from lattice QCD. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 92, 034504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; et al.; [TWQCD Collaboration] Lattice QCD with Nf = 2 + 1 + 1 domain-wall quarks. Phys. Lett. B 2017, 767, 193. [Google Scholar]

- Agaev, S.S.; Azizi, K.H.; Sundu, H. Interpretation of the new states via their mass and width. Eur. Phys. J. C 2017, 77, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershtein, S.S.; Kiselev, V.V.; Likhoded, A.K.; Onishchenko, A.I. Spectroscopy of doubly heavy baryons. Phys. Rev. D 2000, 62, 054021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncaglia, R.; Lichtenberg, D.B.; Predazzi, E. Predicting the masses of baryons containing one or two heavy quarks. Phys. Rev. D 1995, 52, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narodetskii, I.M.; Trusov, M.A. The Heavy baryons in the nonperturbative string approach. Phys. Atom. Nucl. 2002, 65, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynenko, A.P. Ground-state triply and doubly heavy baryons in a relativistic three-quark model. Phys. Lett. B 2008, 663, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karliner, M.; Rosner, J.L. Baryons with two heavy quarks: Masses, production, decays, and detection. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 094007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).