Seismic Assessment of an Existing Precast Reinforced Concrete Industrial Hall Based on the Full-Scale Tests of Joints—A Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

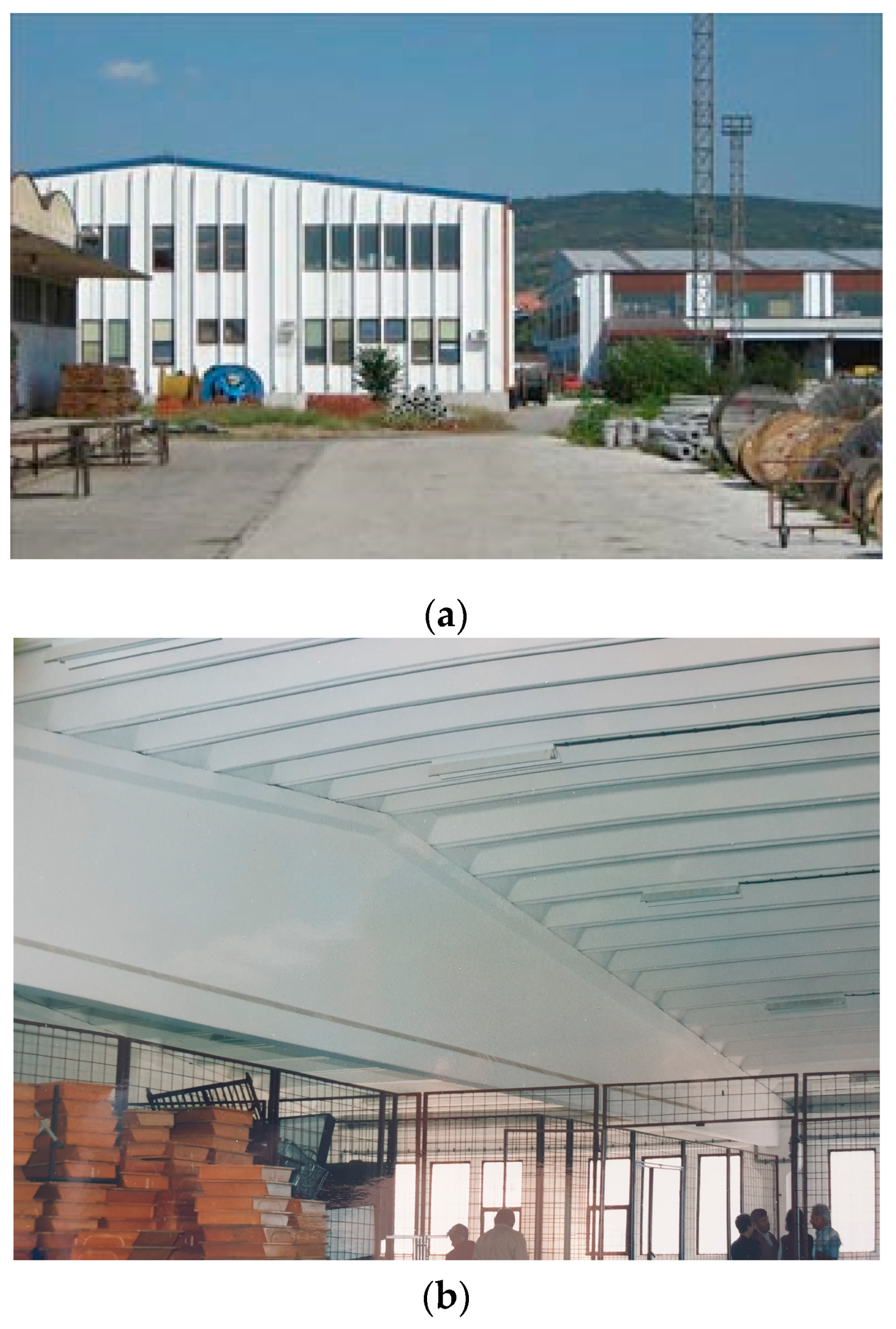

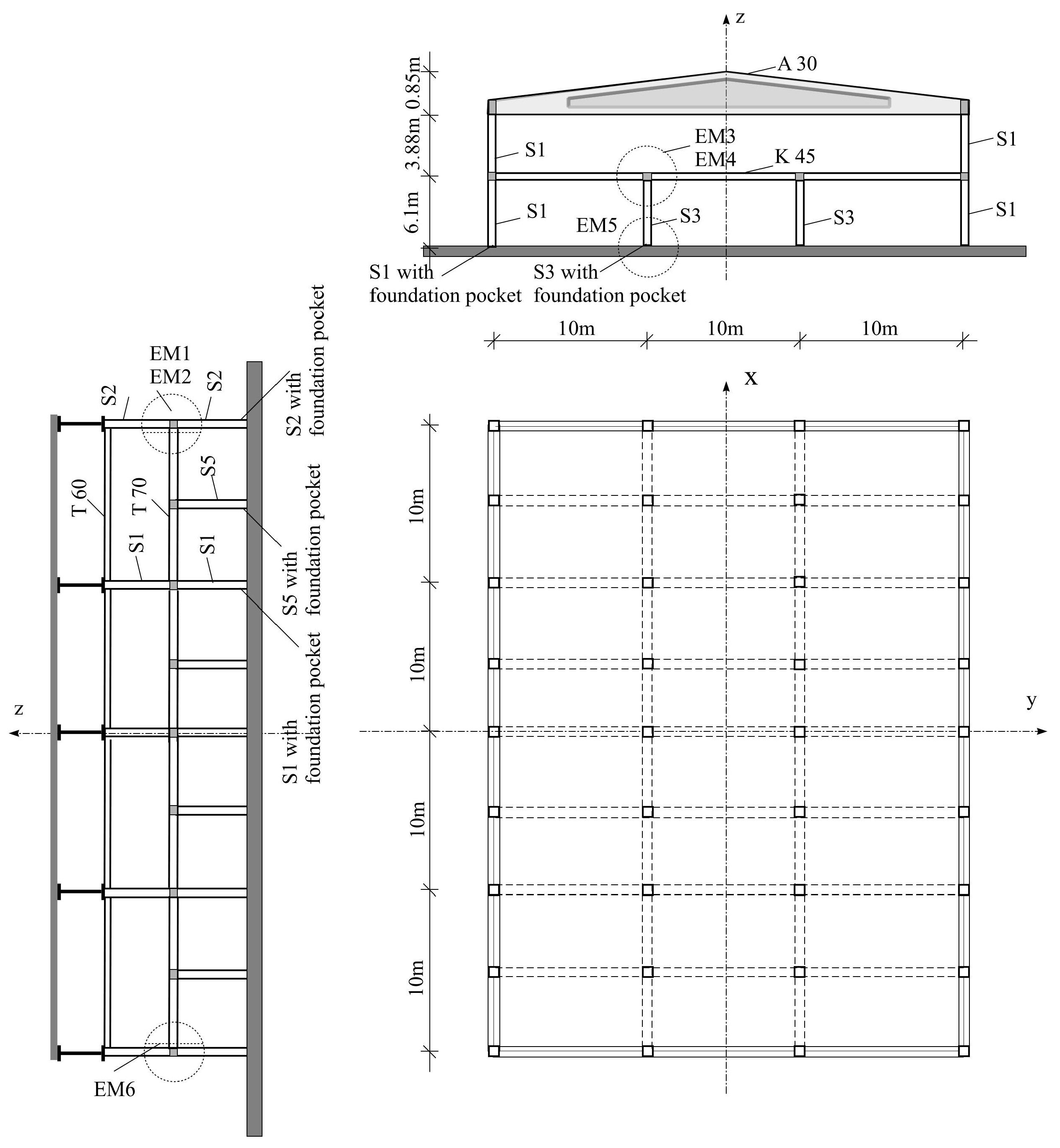

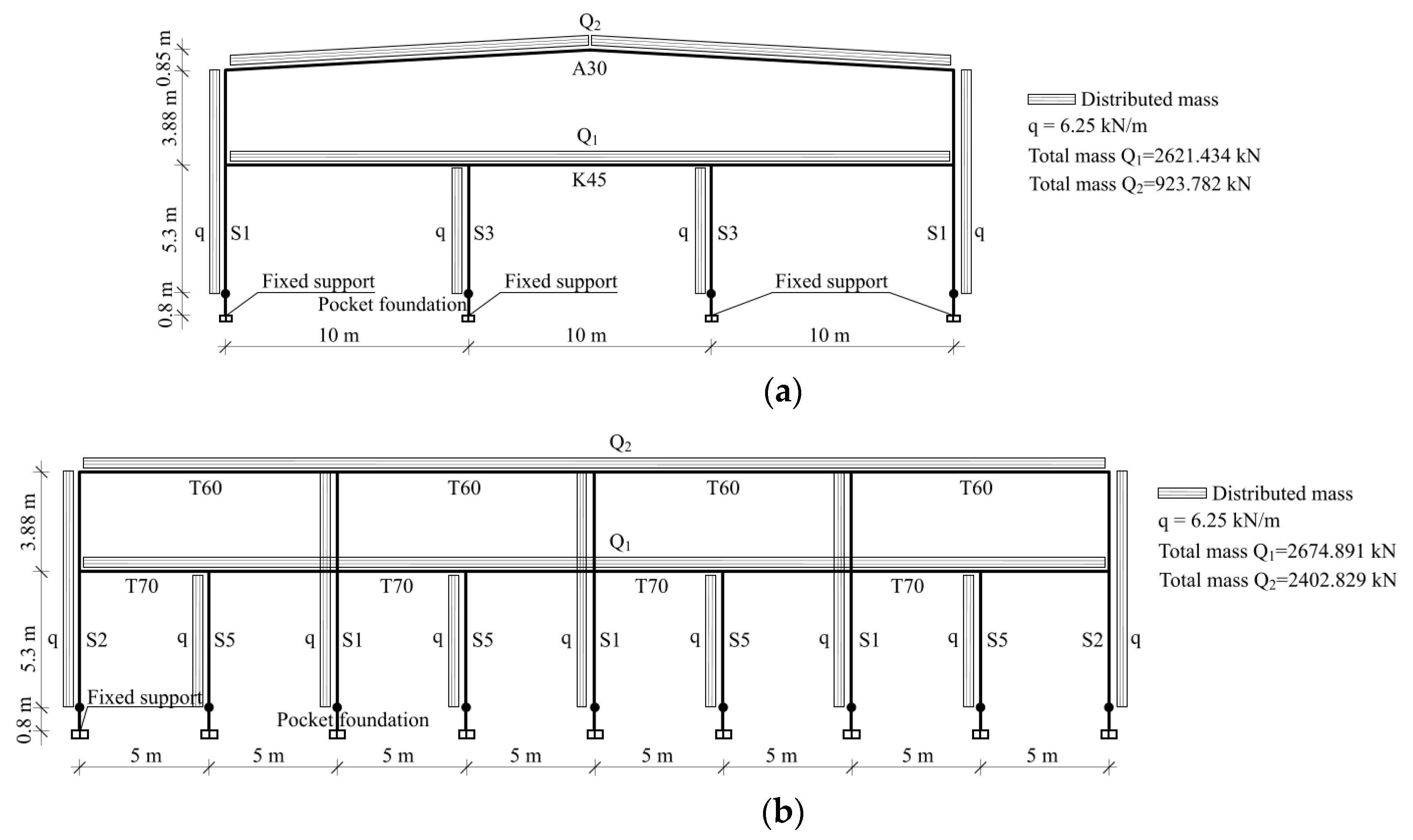

2. Case Study

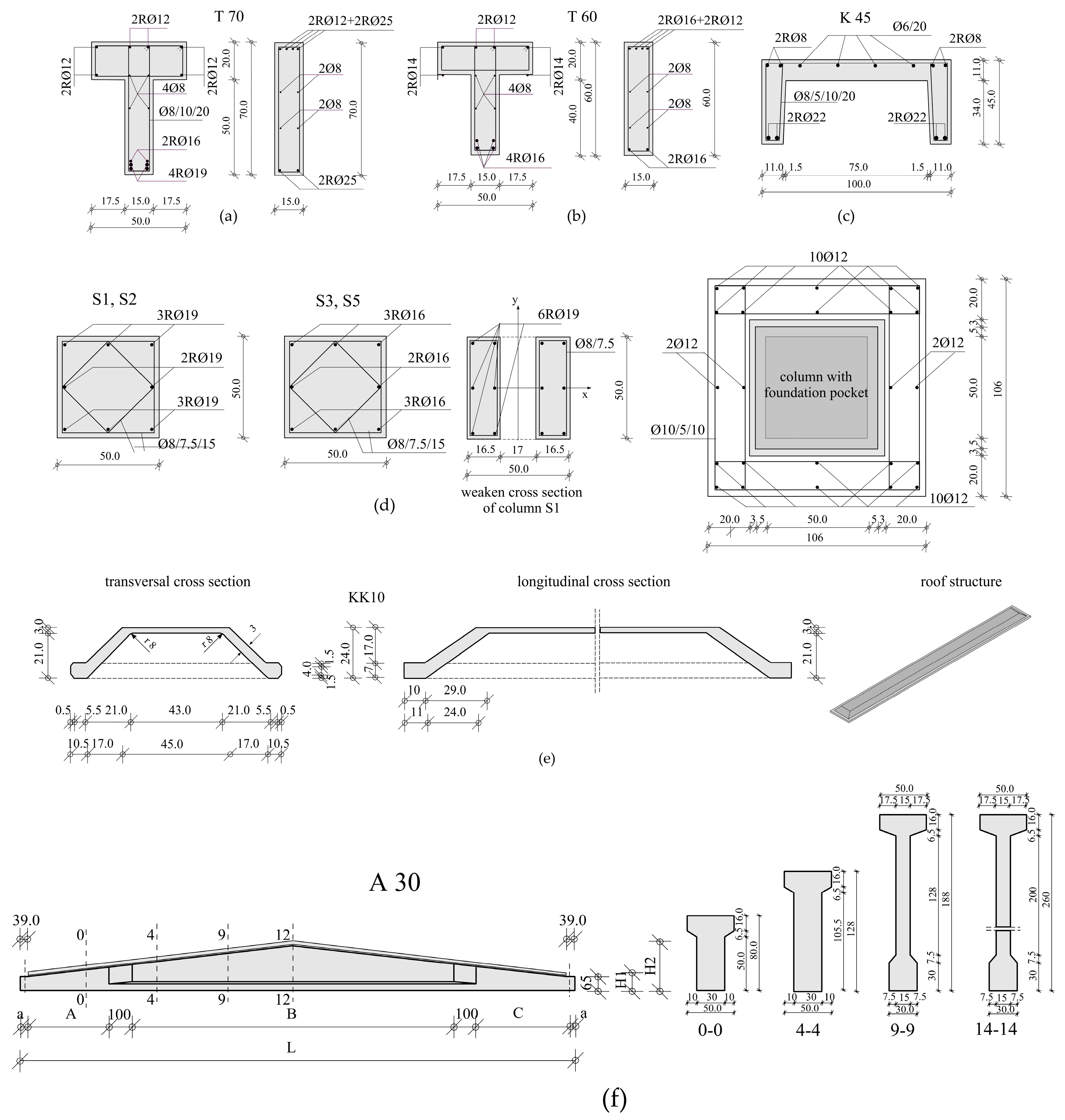

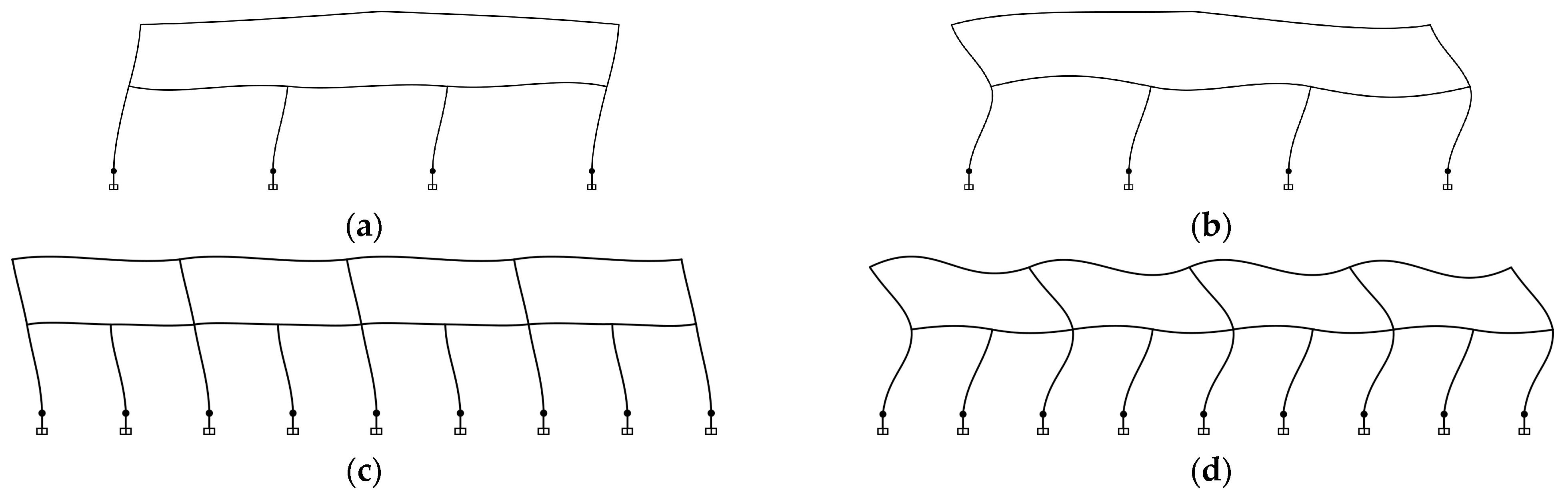

2.1. Structure Description

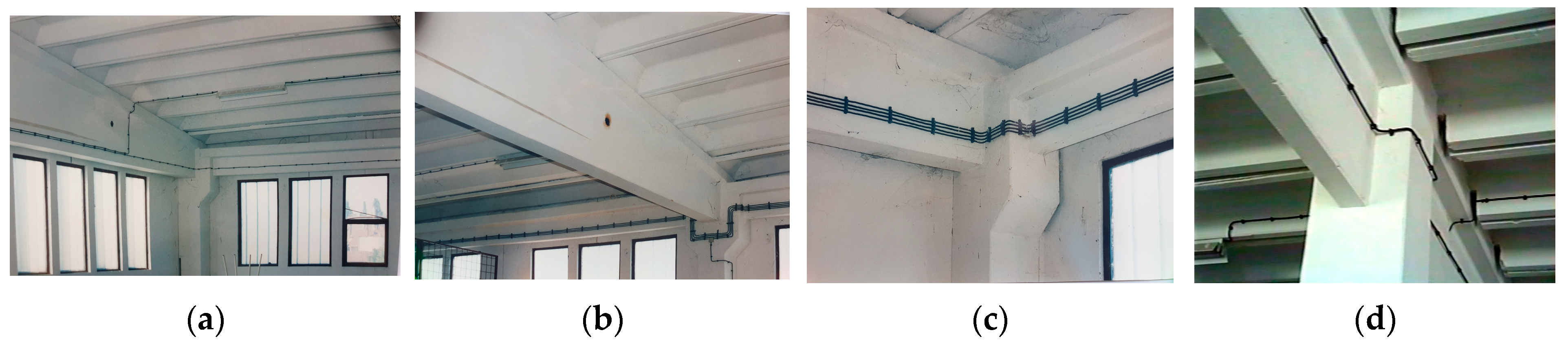

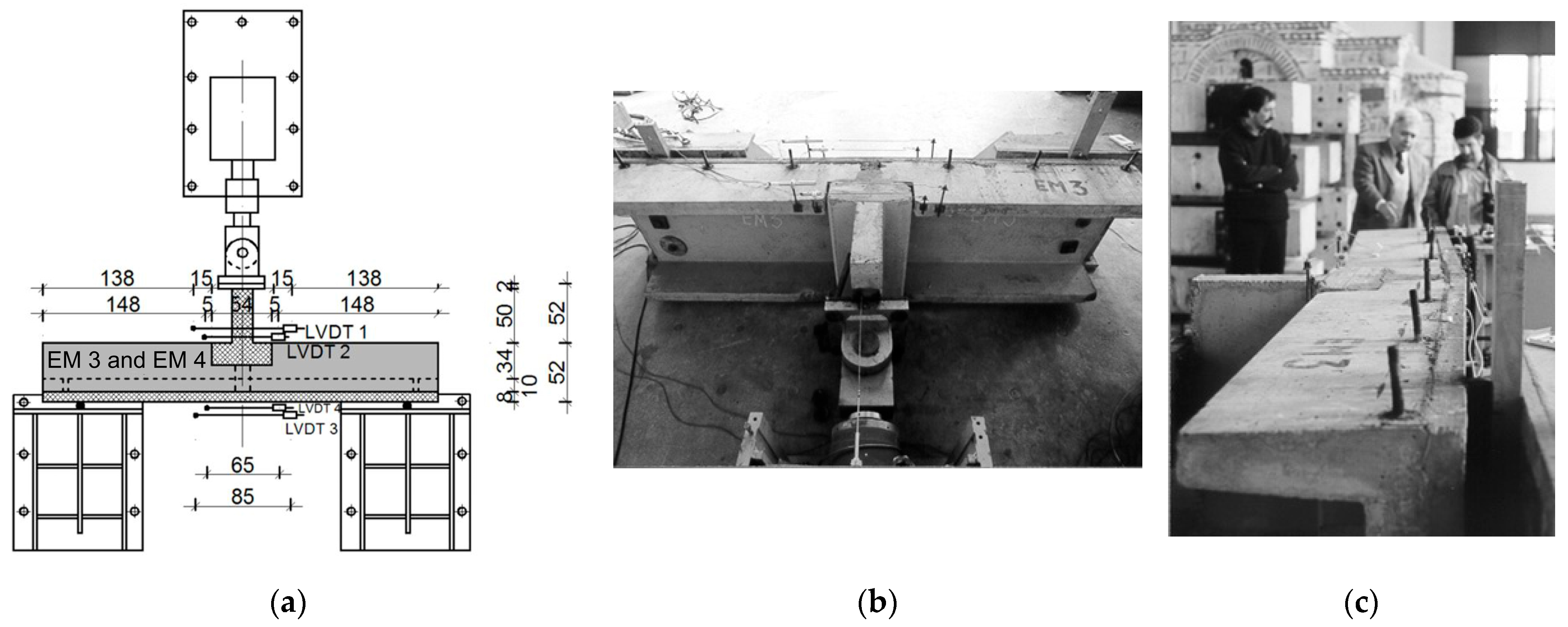

2.2. Quasi-Static Tests of the Full-Scale Models of Connections up to Failure

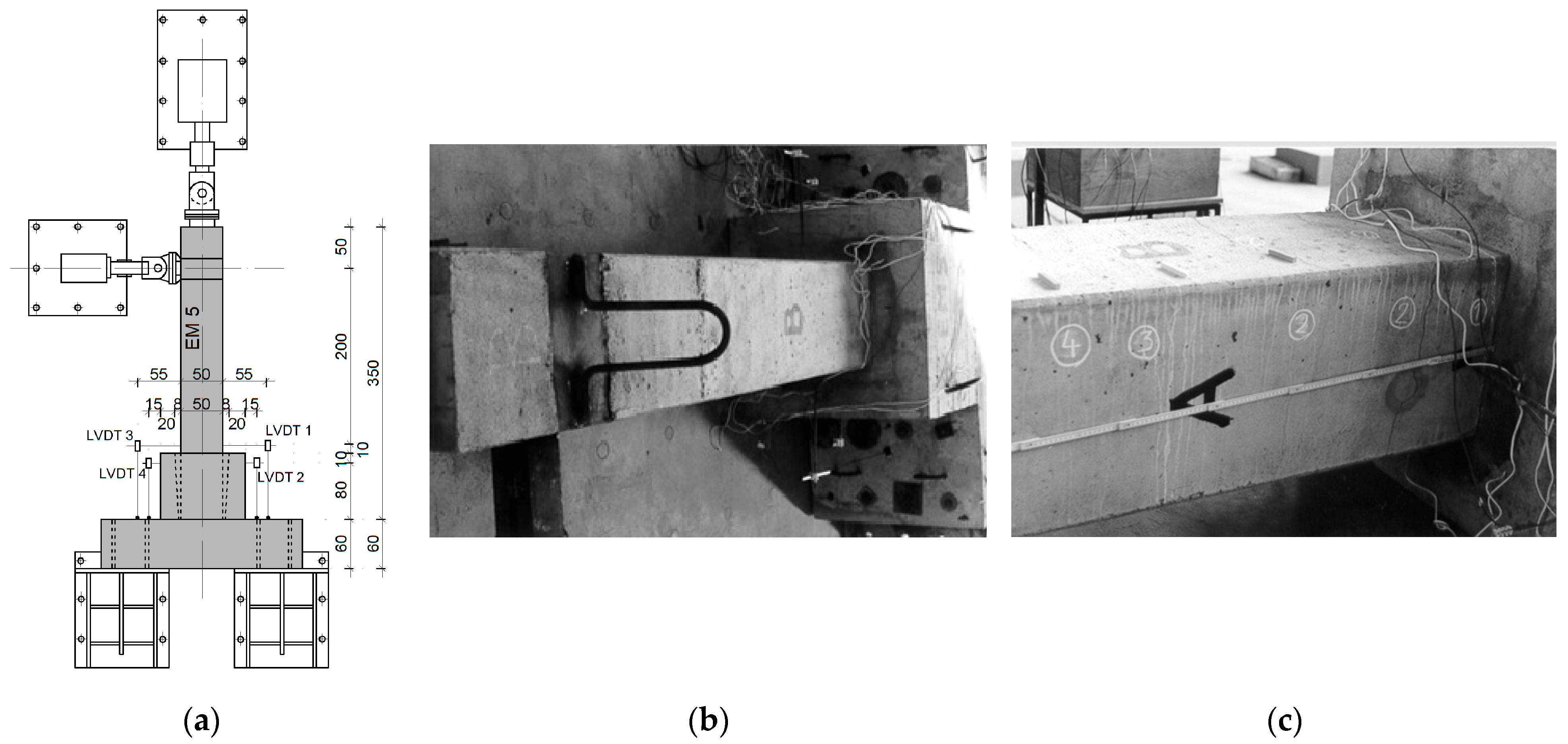

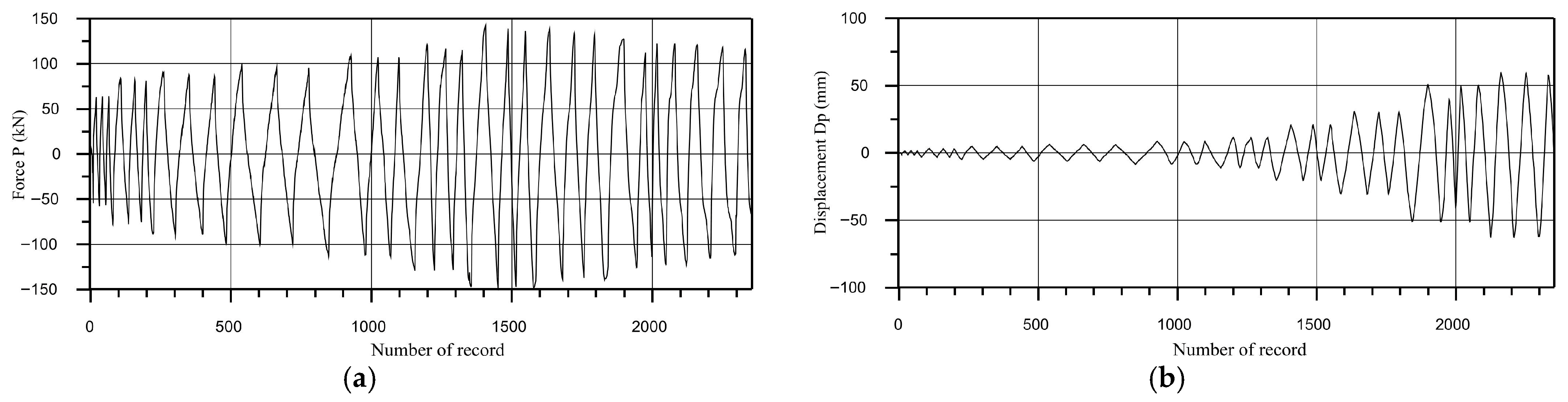

2.2.1. Procedure of Quasi-Static Tests

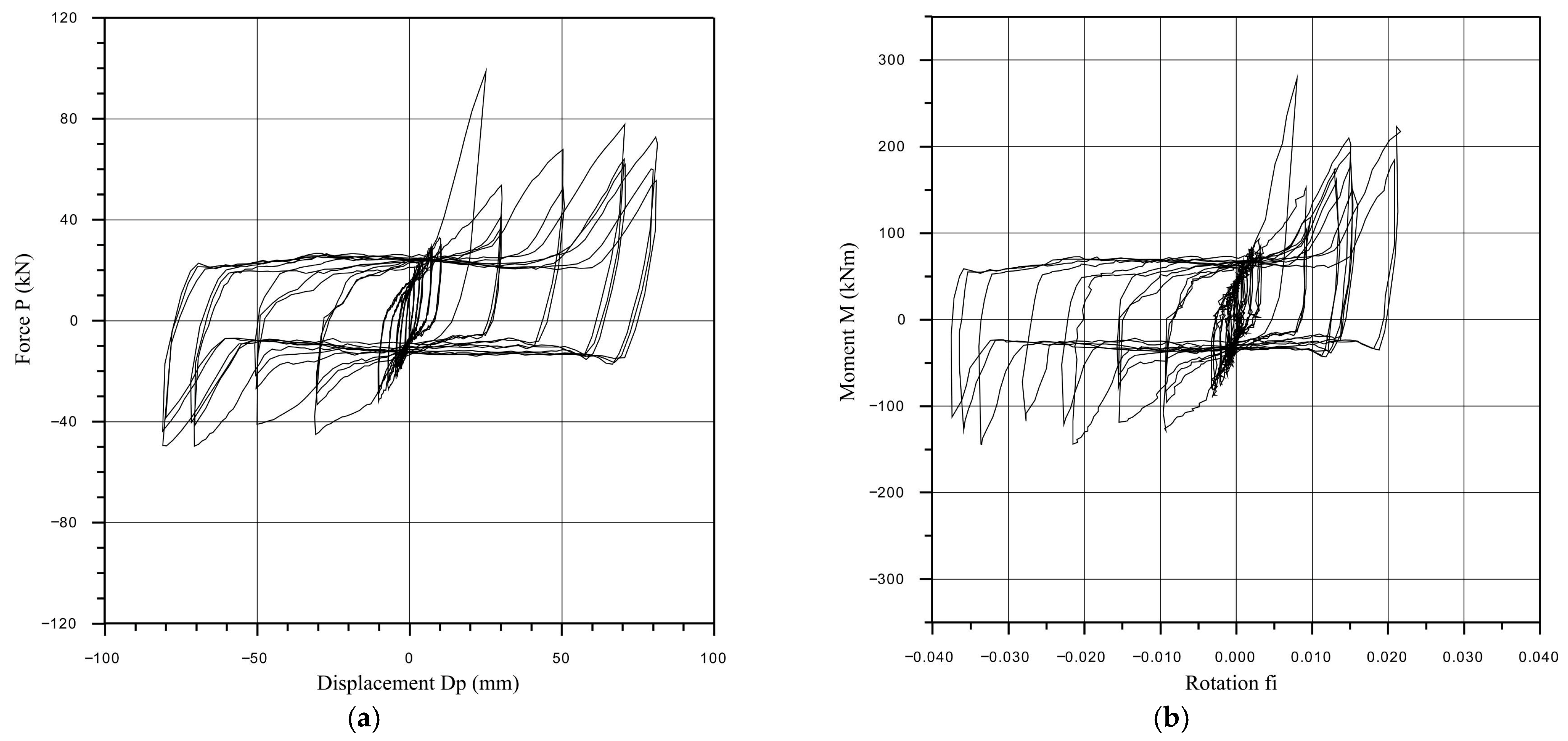

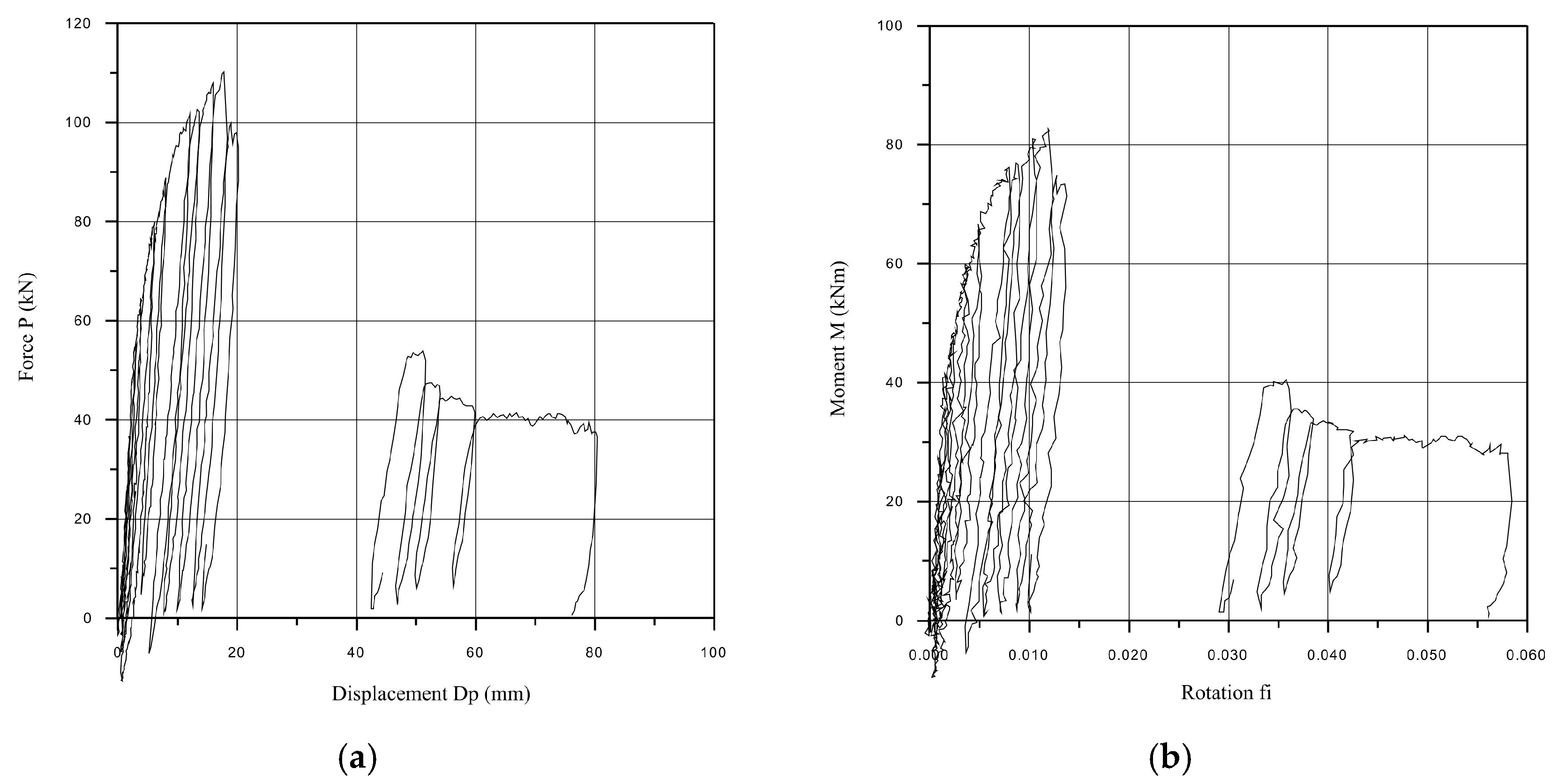

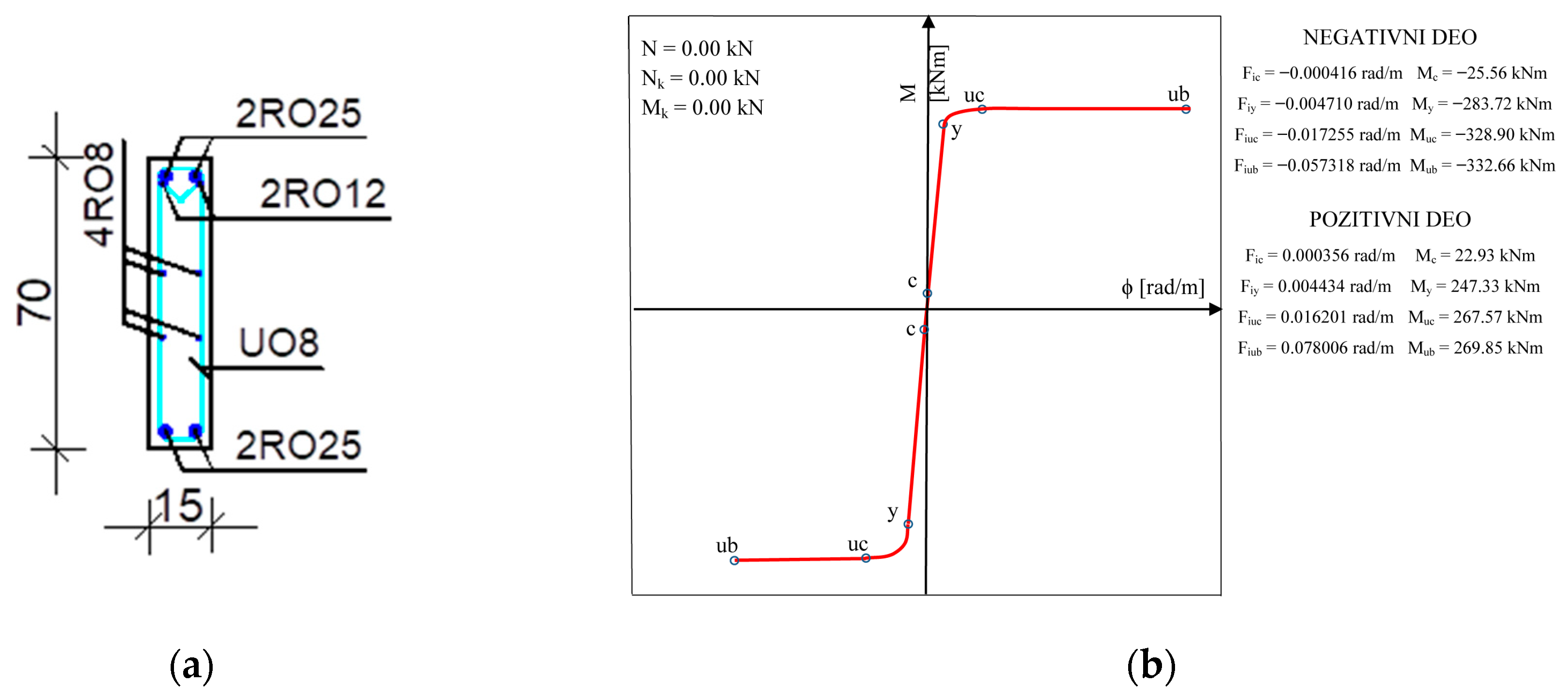

2.2.2. Corner Column to Girder of Floor Structure Connection

2.2.3. Floor Structure to Floor Beam Connection

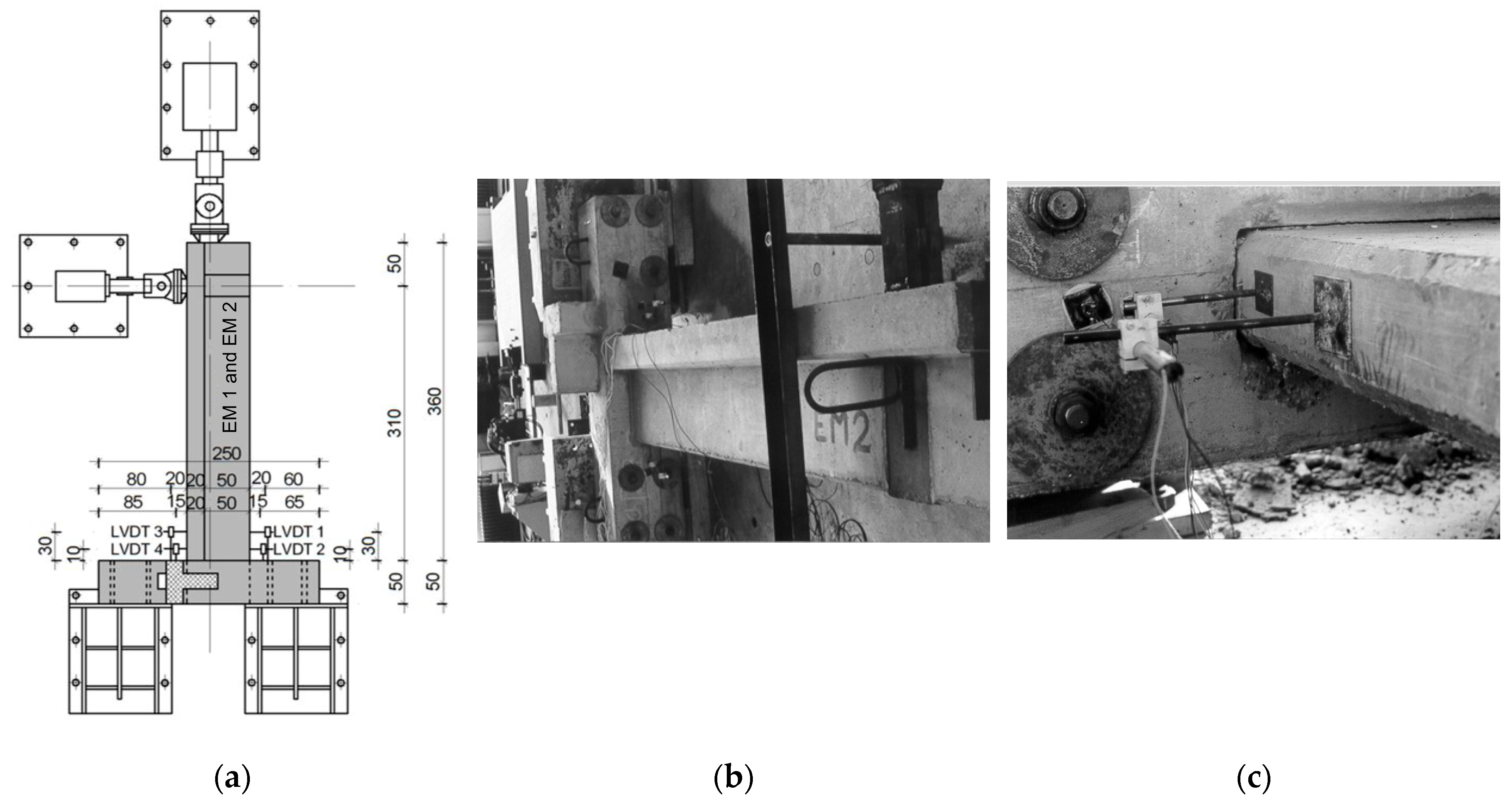

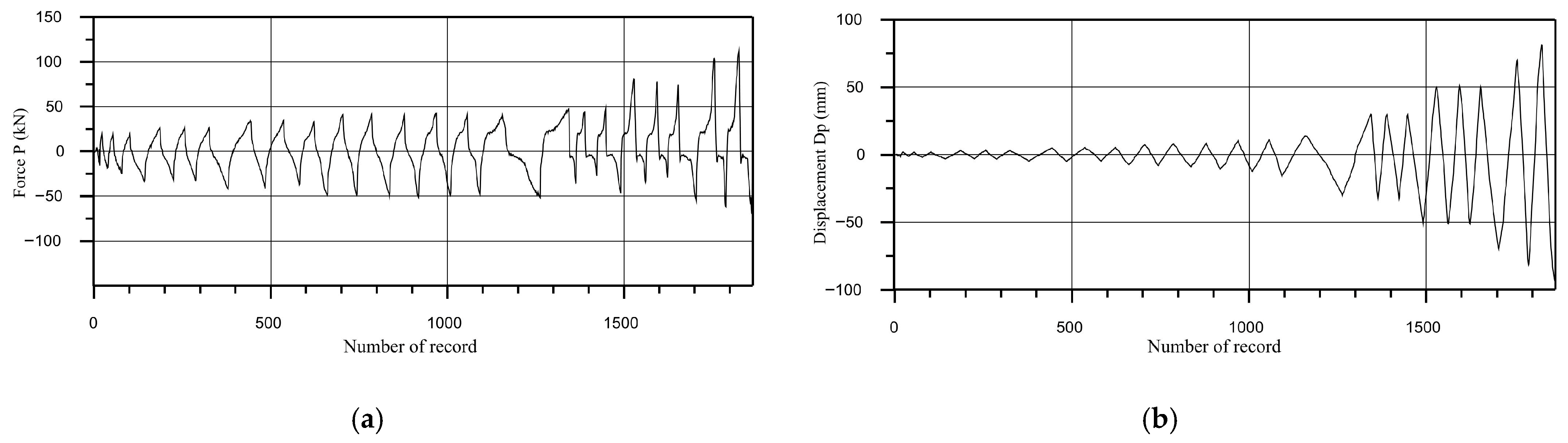

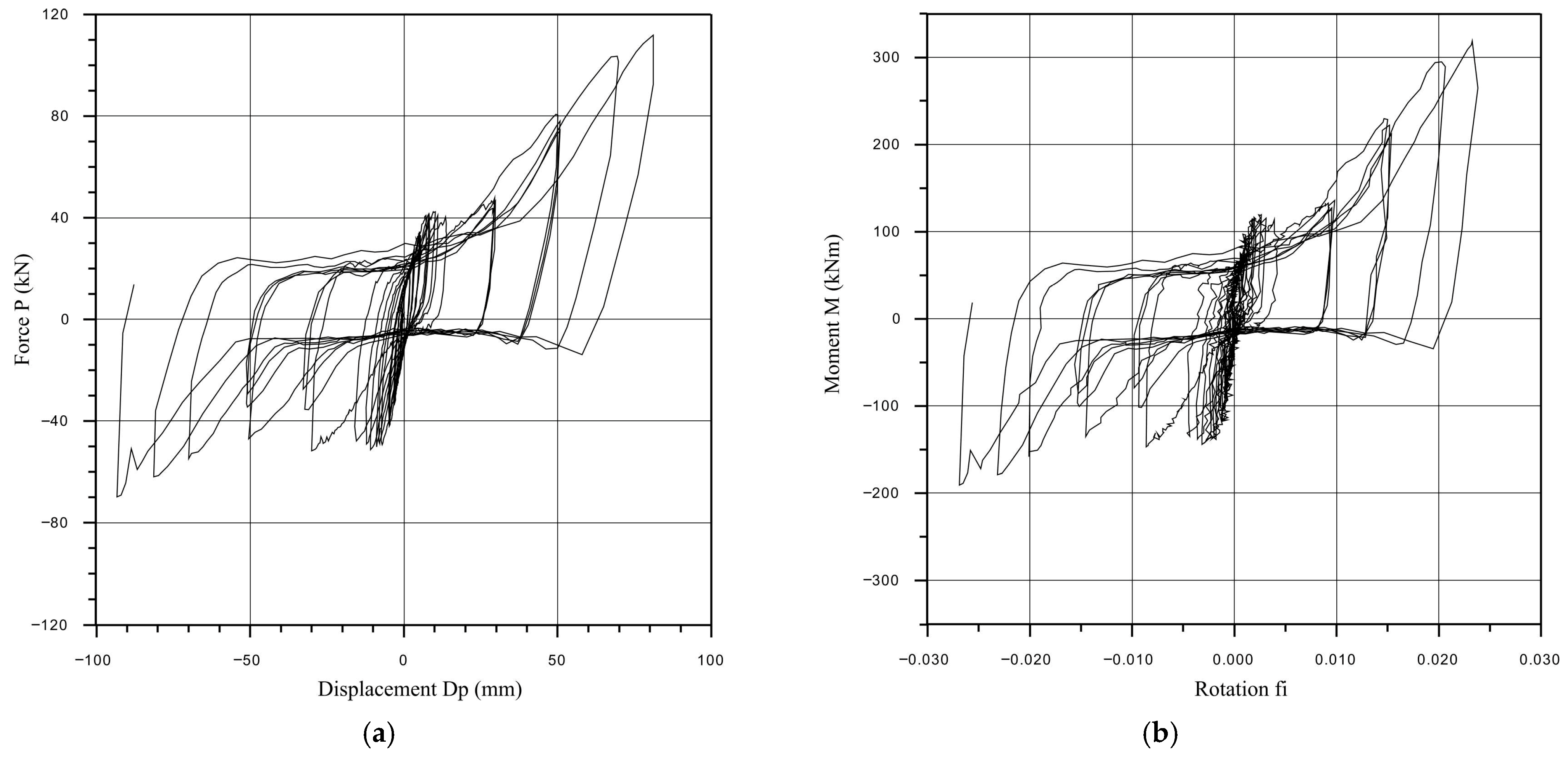

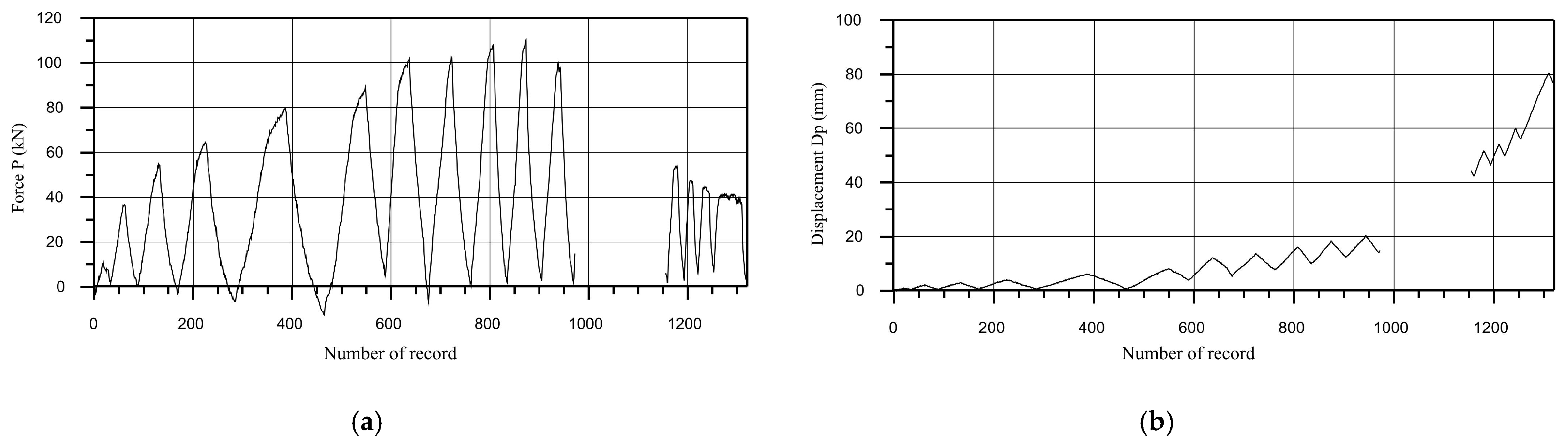

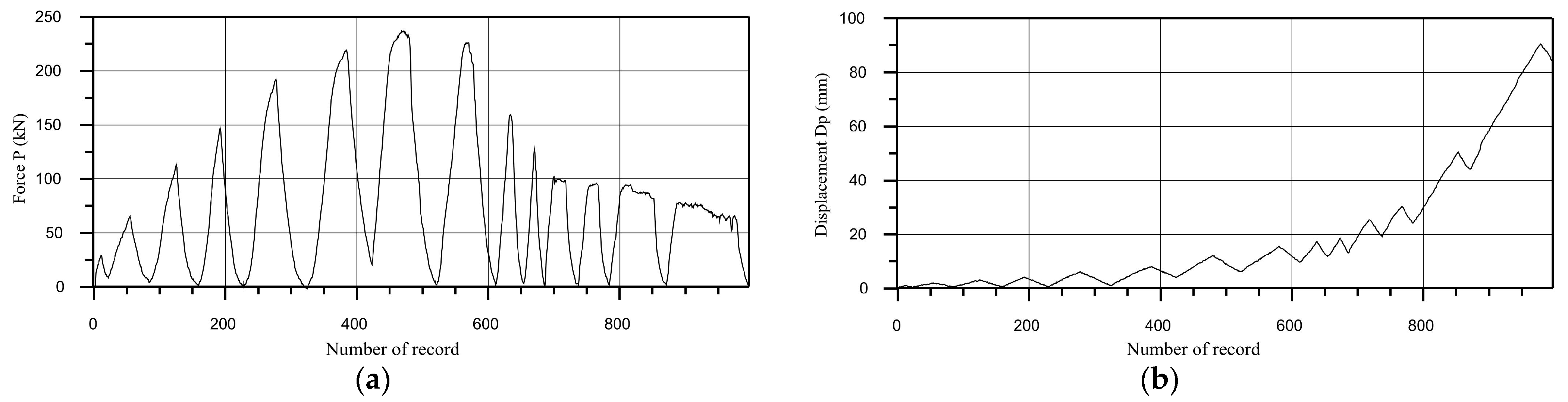

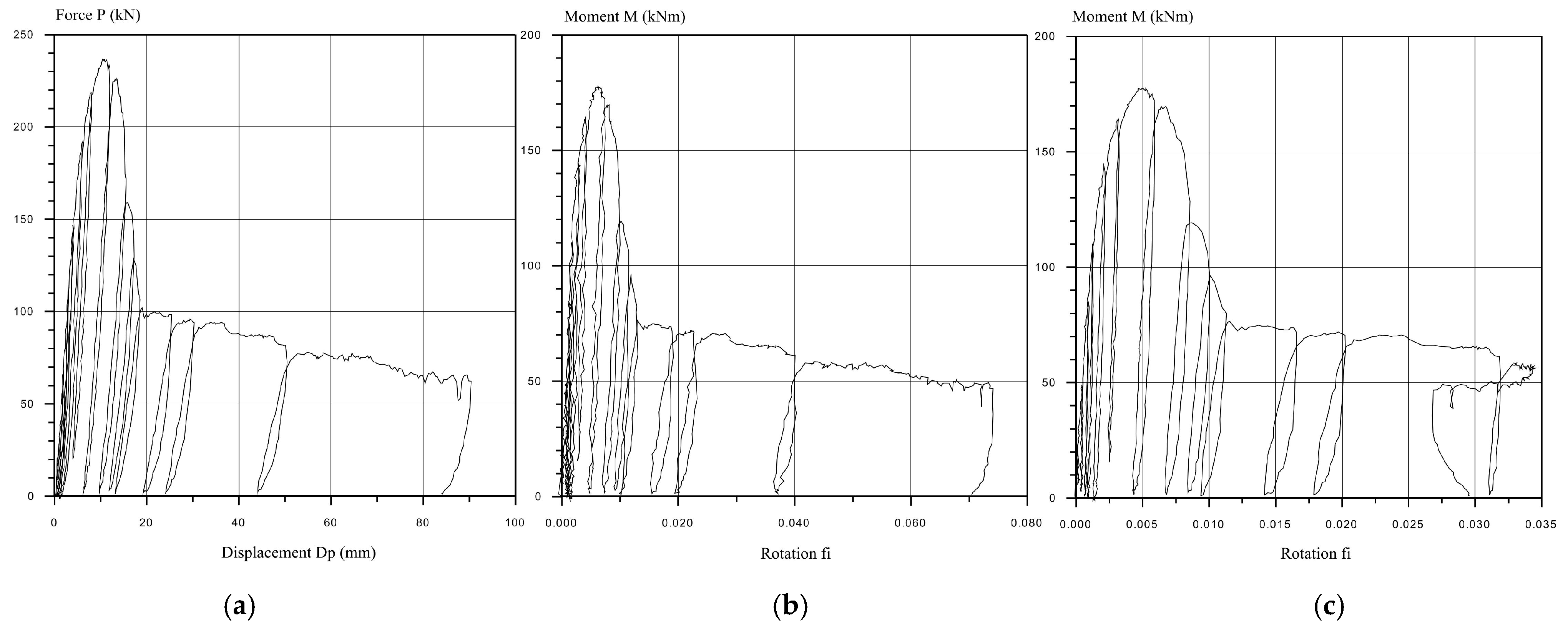

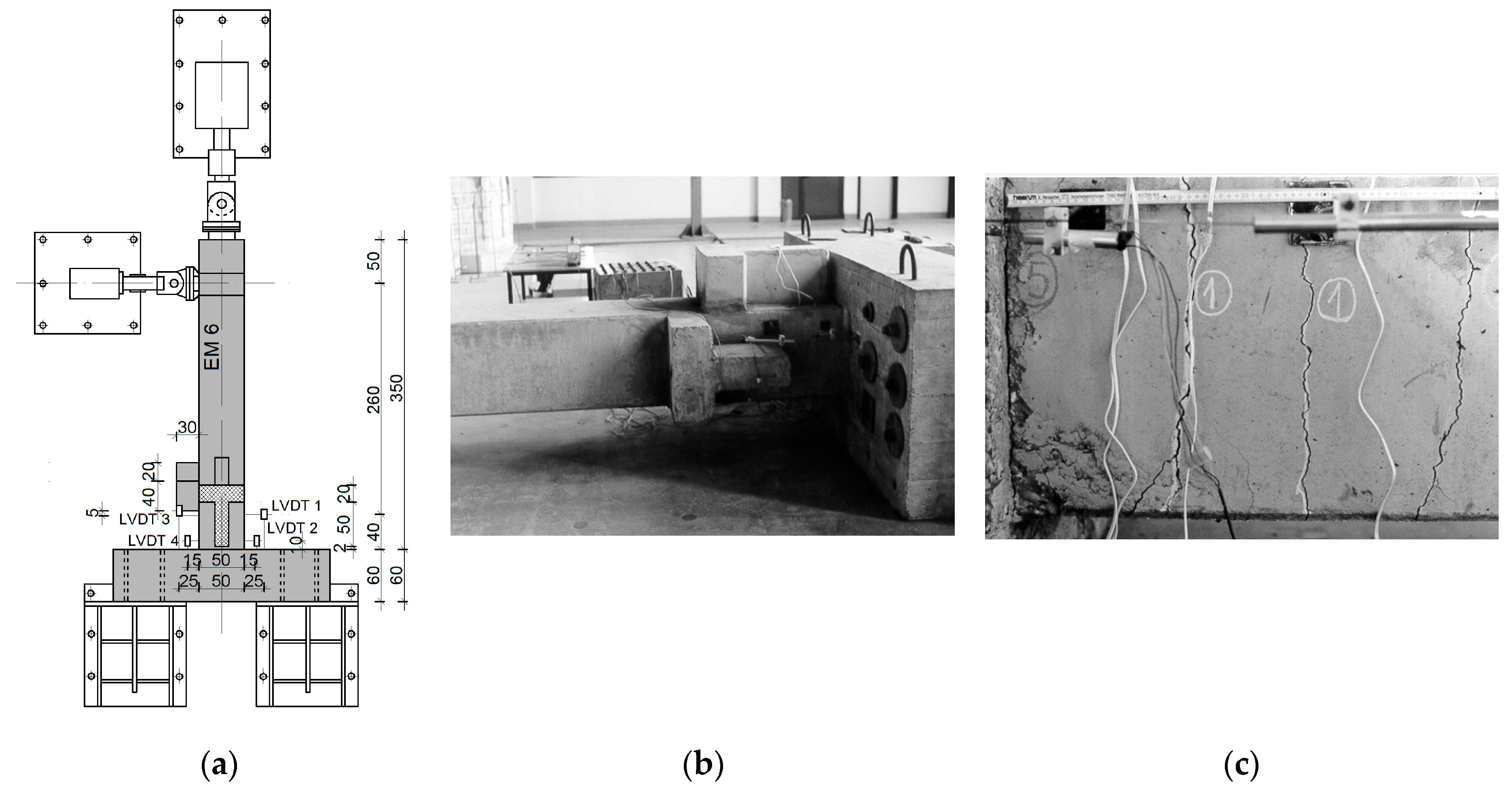

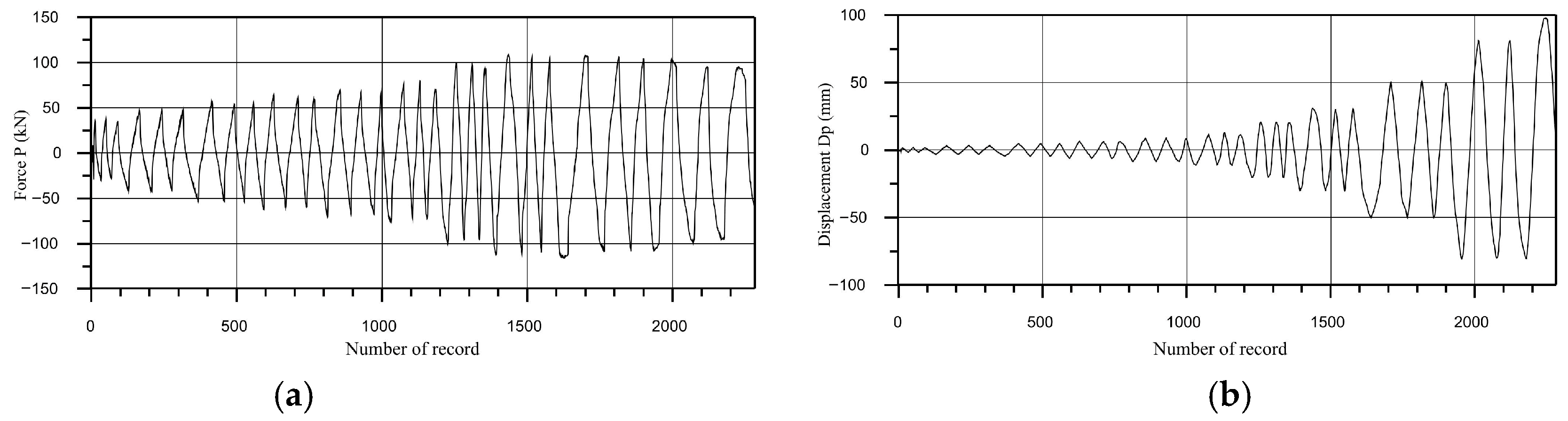

2.2.4. Column to Foundation Connection

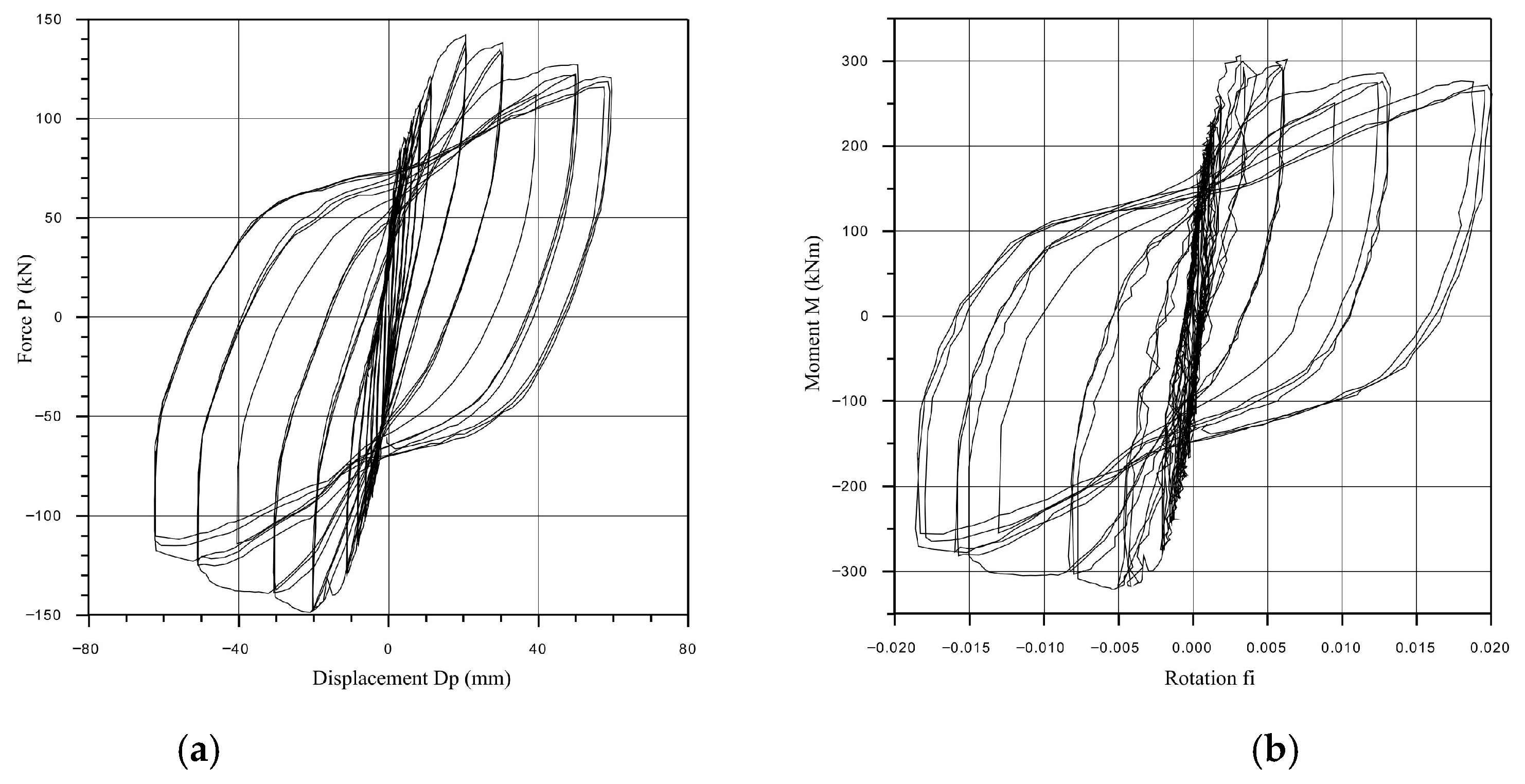

2.2.5. Corner Column to Beam Connection

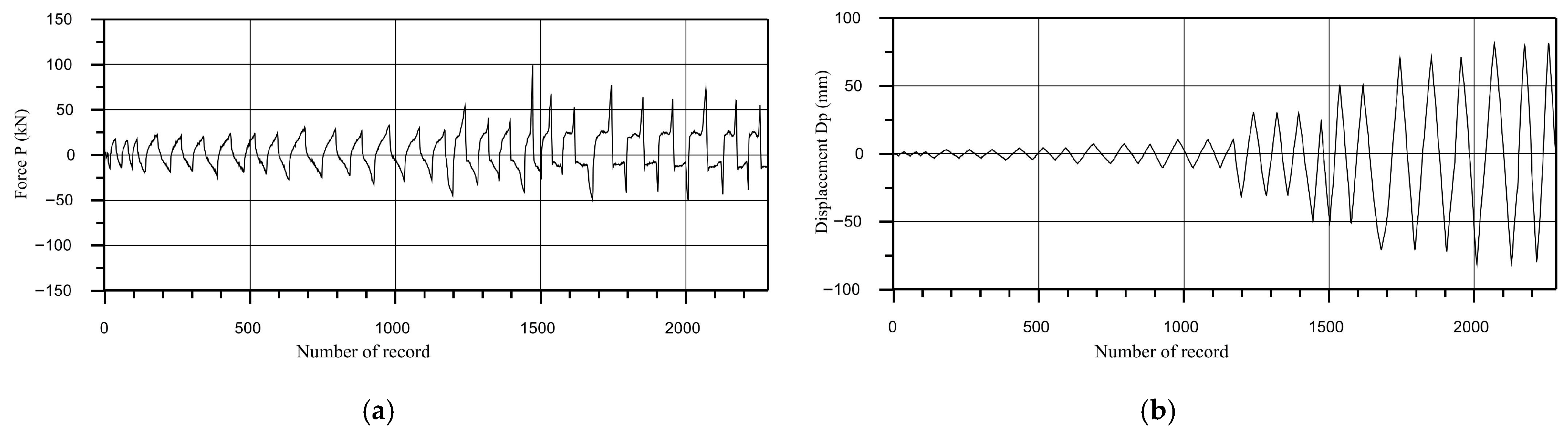

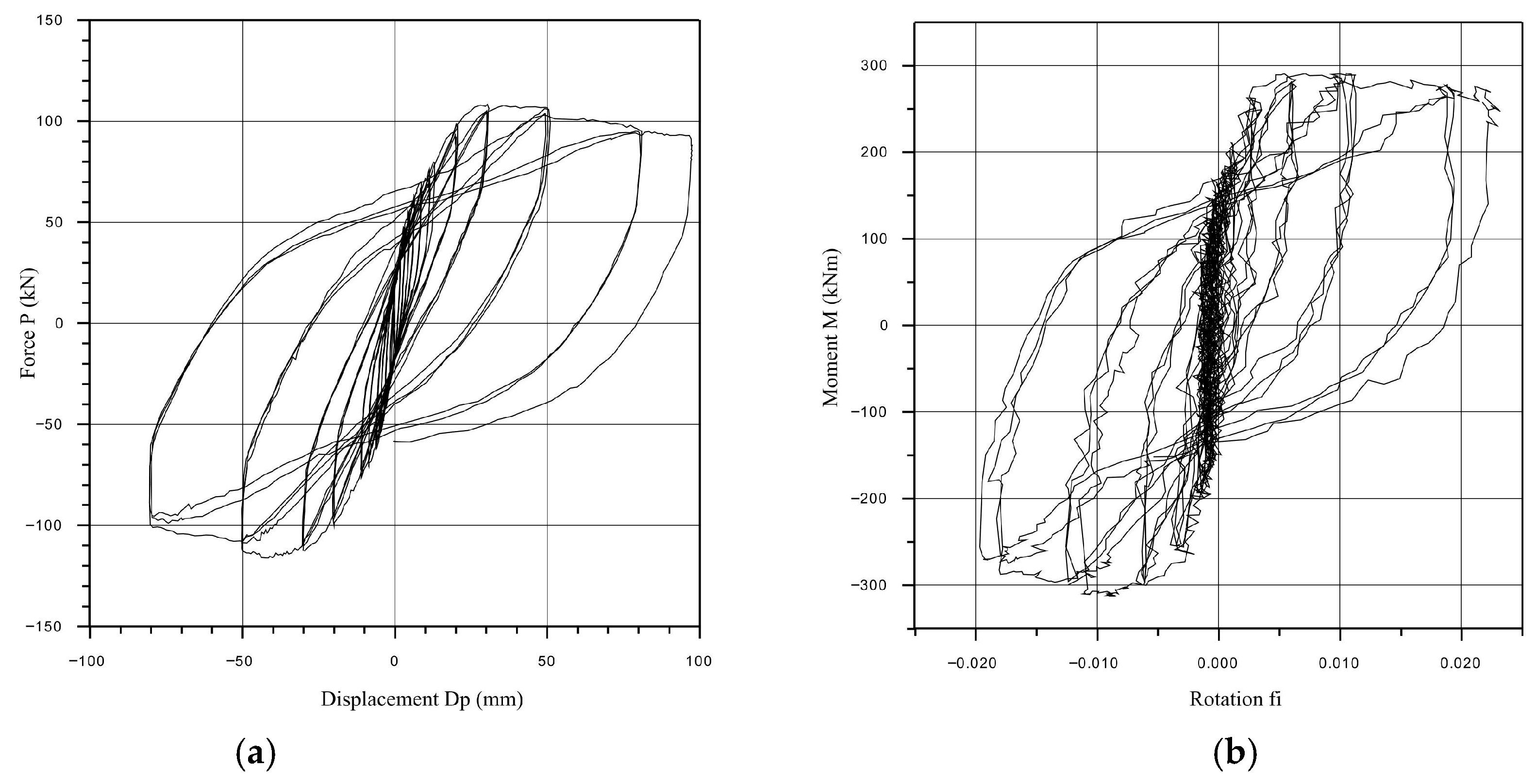

2.2.6. Frame Beam to the Column Connection

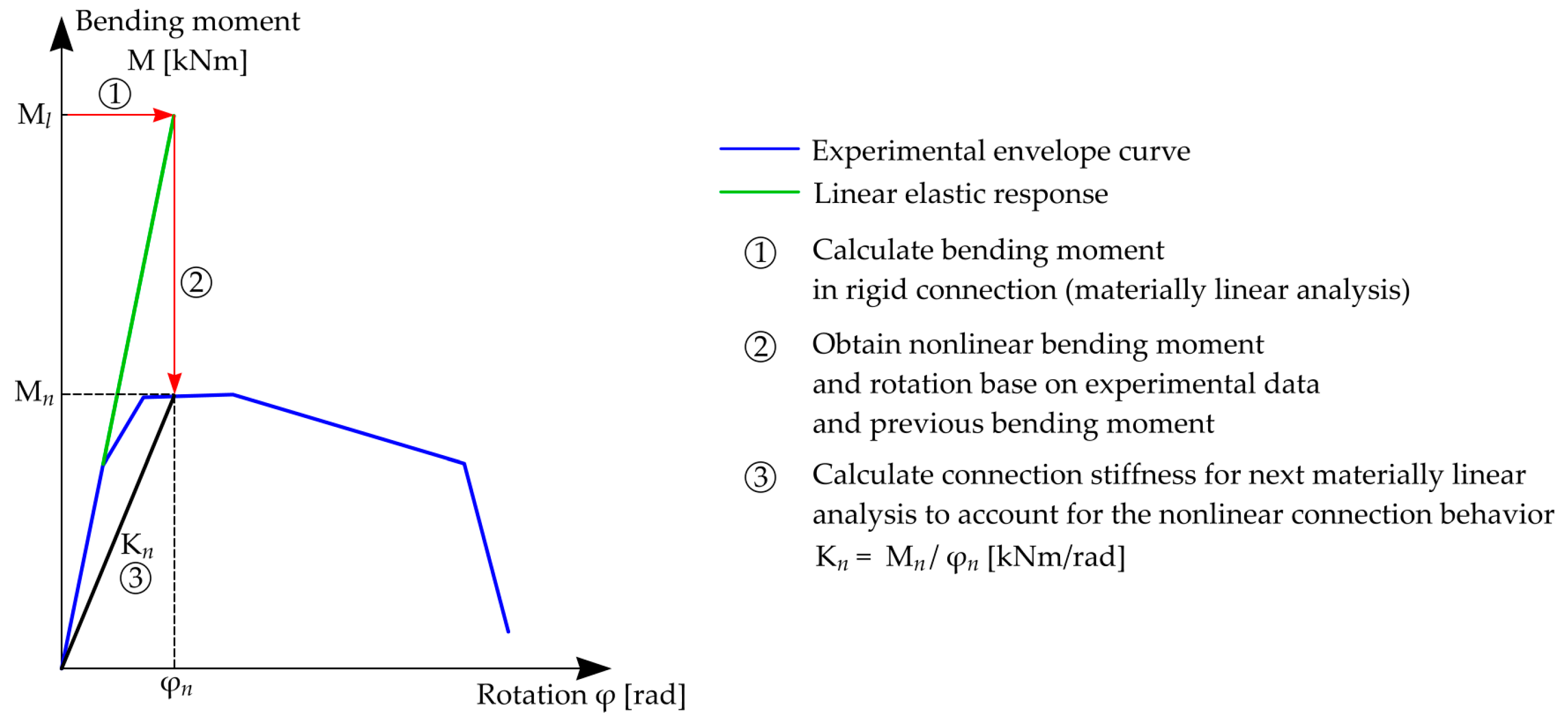

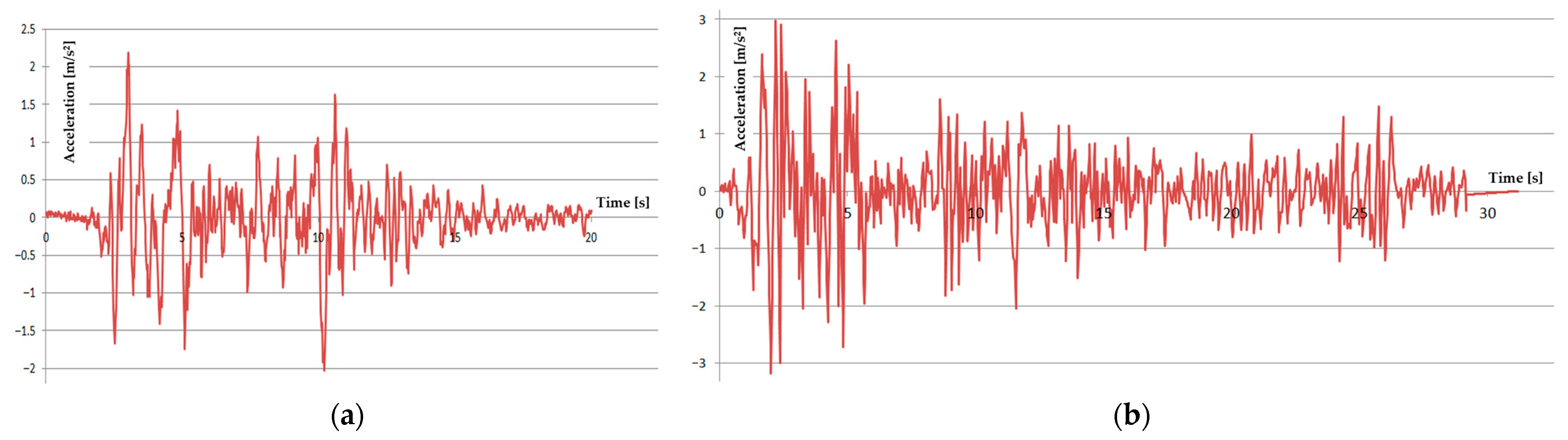

3. Modeling of the Structure and Numerical Analysis

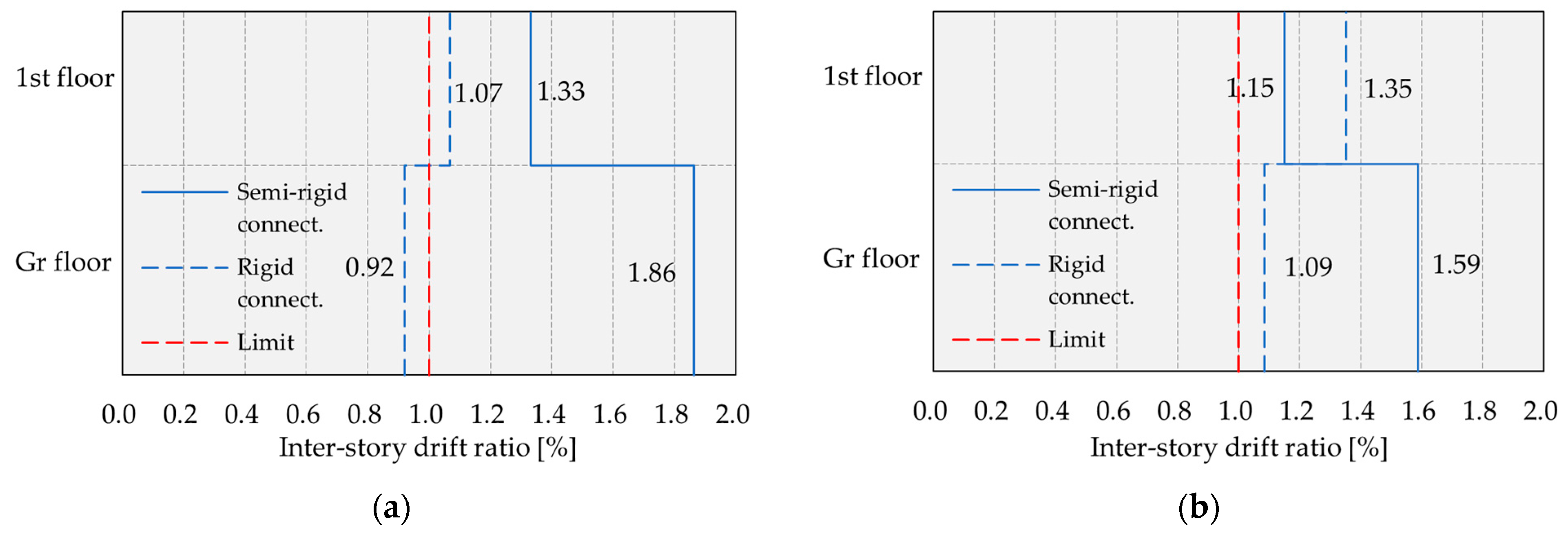

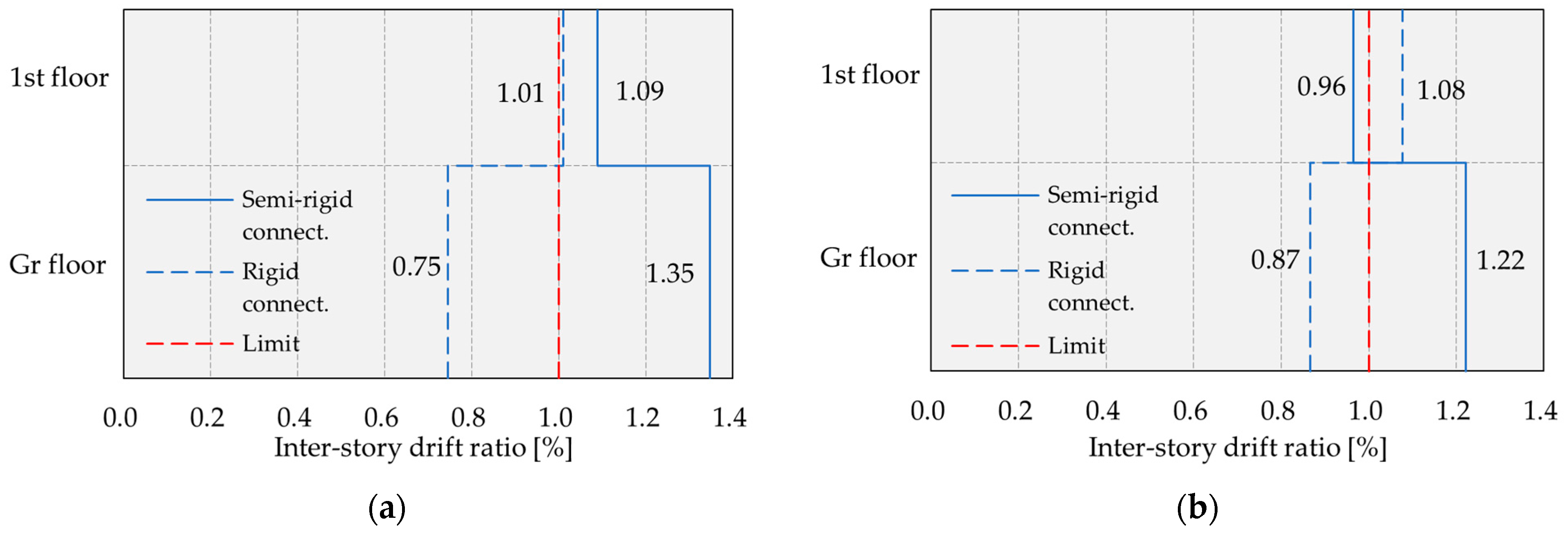

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

- All the experimentally tested connection overlays showed satisfying nonlinear behavior with certain specifics regarding failure. The connection of the floor beam to the corner column is prone to the bond slippage of the tenon from the column during a strong earthquake. The connection of the floor element with the floor beam is characterized by a reduction in the resistance up to 60% after the load-bearing limit force, which can be characterized as brittle fracture. The column–foundation connection and the weakened column–floor beam connection showed stable nonlinear hysteretic behavior with slight stiffness degradation after reaching the ultimate load-bearing capacity, which can be accepted as favorable in the seismic-prone regions.

- These results confirm the necessity of considering the nonlinear behavior and stiffness of connections in precast frame structures when determining displacements, which is particularly important for the verification of the serviceability limit state of structures in seismic regions.

- The simplified approach for taking into account stiffness reduction due to nonlinear behavior of element connections is proposed in the paper.

- The proposed model is validated considering that the roof top displacements differ in the range of 2.33–8.91% compared to nonlinear direct dynamic analysis results.

- Roof top displacements of the considered structure are larger by 16.53–66.93% when the stiffness of the connections is taken into account, compared to the case where the connections are treated as rigid. In the case of inter-story drift ratios, the values are larger by 10–100%, highlighting that inter-story drift ratios are larger than the limit value provided by standard EN 1998-1 when the real stiffnesses of connections are considered. This is especially important from the aspect of the serviceability limit state of structures in seismic regions.

- The simplified approach and proposed modeling of the connections are applicable for seismic risk assessment of existing industrial halls and commercial buildings constructed in the considered structural system, and for other PCR systems which are produced industrially in large series and which are designed in zones of seismic activity VIII or IX.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ristic, D. Observed Damage Industrial Structures Due to Friuli, Italy Earthquake of 1976; IZIIS-Skopje: Skopje, North Macedonia, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Marzo, A.; Marghella, G.; Indirli, M. The Emilia-Romagna earthquake: Damages to precast/prestressed reinforced concrete factories. Ing. Sismica 2012, 30, 132–147. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259911421 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Avğın, S.; Köse, M.M.; Çınar, M. Critical review of design practices and observed damages in precast industrial buildings: Evidence from the February 2023 Türkiye earthquakes. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, M.; Al-Washali, H. Damage Due to Earthquakes and Improvement of Seismic Performance of Reinforced Concrete Buildings in Japan. In Seismic Hazard and Risk Assessment; Vacareanu, R., Ionescu, C., Eds.; Springer Natural Hazards; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; London, UK, 2018; pp. 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeborough, A.; Merriman, P.A.; Williams, M.S. (Eds.) The Northridge California Earthquake of 17 January 1994, a Field Report by EEFIT; Institution of Structural Engineers: London, UK, 1994; Available online: https://www.eeri.org/1994/01/northridge-california/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Muguruma, H.; Nishiyama, M.; Watanabe, F. Lessons learned from the Kobe earthquake, A Japanese perspective. PCI J. 1995, 40, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, M.; Wood, S.L. Seismic performance of precast industrial buildings in Turkey. In Proceedings of the Seventh U.S. National Conference on Earthquake Engineering, Boston, MA, USA, 21–25 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, B.; Taucer, F.; Rossetto, T. Field investigation on the performance of building structures during the 12 May 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in China. Eng. Struct. 2009, 31, 1707–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senel, S.M.; Kayhan, A.H. Fragility based damage assessment in existing precast industrial buildings: A case study for Turkey. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2010, 34, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić-Brzev, S.; Marko Marinković, M.; Ivan Milićević, I.; Blagojević, N.; Isufi, B. Consequences of the Earthquake in Albania from November 26, 2019 on Facilities and Infrastructure; Serbian Association for Earthquake Engineering; Akademska misao: Belgrade, Serbia, 2020; ISBN 978-86-7466-843-6. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Kurama, Y.C.; Sritharan, S.; Fleischman, R.B.; Restrepo, J.I.; Henry, R.S.; Cleland, N.M.; Ghosh, S.K.; Bonelli, P. Seismic-Resistant Precast Concrete Structures: State of the Art. J. Struct. Eng. 2018, 144, 03118001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucuoglu, H. Effect of connection rigidity on seismic response of precast concrete frames. PCI J. 1995, 40, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatkov, D.; Zdravković, S.; Mladenović, B.; Mijalković, M. Seismic analysis of frames with semi-rigid connections in accordance with EC8. Facta Univ. Ser. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2020, 18, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.S.; Davies, G.; Ferreira, M.; Gorgun, H.; Mahdi, A.A. Can precast concrete structures be designed as semi rigid frames? Part 1—The experimental evidence. Struct. Eng. 2003, 81, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pampanin, S.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Sritharan, S. Analytical modelling of the seismic behaviour of precast concrete frames designed with ductile connections. J. Earthq. Eng. 2001, 5, 329–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremmyda, G.D.; Fahjan, Y.M.; Psycharis, I.N. Analytical prediction of the shear resistance of precast RC pinned beam-to-column connections. In Proceedings of the 4th ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering (COMPDYN 2013), Kos Island, Greece, 12–14 June 2013; pp. 1502–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Song, B.; Du, D.; Li, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Feng, D. Analytical investigation of the differences between cast-in-situ and precast beam-column connections under seismic actions. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, H.; Rodriguez, V.; Escobar, J.A.; Alcocer, S.M.; Bennetts, F.; Suarez, M. Experimental tests of precast reinforced concrete beam-column connections. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2019, 124, 105743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimbene, R.; Bianco, L. Cyclic response of column to foundation connections of reinforced concrete precast structures: Numerical and experimental comparisons. Eng. Struct. 2021, 247, 113214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemamathi, L.; Jaya, K.P. Behaviour of precast column foundation connection under reverse cyclic loading. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6677007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischinger, M.; Zoubek, B.; Isaković, T. Seismic Response of Precast Industrial Buildings. In Perspectives on European Earthquake Engineering and Seismology; Ansal, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 34, pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremmyda, G.D.; Fahjan, Y.M.; Tsoukantas, S.G. Nonlinear FE analysis of precast RC pinned beam-to-column connections under monotonic and cyclic shear loading. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2014, 12, 1615–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremmyda, G.D.; Fahjan, Y.M.; Psycharis, I.N.; Tsoukantas, S.G. Numerical investigation of the resistance of precast RC pinned beam-to-column connections under shear loading. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 46, 1511–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubek, B.; Fahjan, Y.M.; Fischinger, M.; Isaković, T. Nonlinear finite element modelling of centric dowel connections in precast buildings. Comput. Concr. 2014, 14, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubek, B.; Fischinger, M.; Isakovic, T. Estimation of the cyclic capacity of beam-to-column dowel connections in precast industrial buildings. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 13, 2145–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.-C.; Wu, G.; Lu, Y. Finite element modelling approach for precast reinforced concrete beam-to-column connections under cyclic loading. Eng. Struct. 2018, 174, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.; Batalha, N.; Rodrigues, H. Numerical simulation of beam-to-column connections in precast reinforced concrete buildings using fibre-based frame models. Eng. Struct. 2020, 203, 109845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabia, A.M.; Etman, E.E.; Allam, S.M.; Aboelhassan, M.G. Modeling of precast reinforced concrete beam-column joints under cyclic loading. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 26, 7626–7655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawileh, R.A.; Rahman, A.; Tabatabai, H. Nonlinear finite element analysis and modeling of a precast hybrid beam-column connection subjected to cyclic loads. Appl. Math. Model. 2010, 34, 2562–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozden, S.; Ertas, O. Modeling of pre-cast concrete hybrid connections by considering the residual deformations. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2010, 5, 781–792. [Google Scholar]

- Nzabonimpa, J.D.; Hong, W.-K.; Kim, J. Nonlinear finite element model for the novel mechanical beam-column joints of precast concrete-based frames. Comput. Struct. 2017, 182, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, M.N.; Ferreira, M.A.; El Debs, A.L.H.C. Nonlinear FE analysis of slab-beam-column connection in precast concrete structures. Eng. Struct. 2017, 143, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunesi, E.; Nascimbene, R.; Bolognini, D.; Bellotti, D. Experimental investigation of the cyclic response of reinforced precast concrete framed structures. PCI J. 2015, 60, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Yang, X. Seismic tests of precast concrete, moment-resisting frames and connections. PCI J. 2010, 55, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourasia, A.; Kajale, Y.; Singhal, S.; Parashar, J. Seismic performance assessment of two-storey precast reinforced concrete building. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 2011–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, A.S.; Bharti, S.D.; Shrimali, M.K.; Datta, T.K. Modeling of Precast Building Frames for Seismic Response Analysis. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 8419–8436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Feng, D.-C.; Cao, X.; Wu, G. Seismic performance assessment of code-conforming precast reinforced concrete frames in China. Earthq. Struct. 2021, 21, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, G.; Bellotti, D.; Cimmino, M.; Nascimbene, R. Modeling and Seismic Response Analysis of RC Precast Italian Code-Conforming Buildings. J. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 22, 140–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, M.E.; Belleri, A.; Riva, P.; Magliulo, G.; Bellotti, D.; Dal Lago, B. Effects of modeling assumptions on the evaluation of the local seismic response for RC precast industrial buildings. In Proceedings of the 7th ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Methods in Structural Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering (COMPDYN 2019), Crete, Greece, 24–26 June 2019; pp. 182–195. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, H.; Vitorino, H.; Batalha, N.; Sousa, R.; Fernandes, P.; Varum, H. Influence of Beam-to-Column Connections in the Seismic Performance of Precast Concrete Industrial Facilities. Struct. Eng. Int. 2022, 32, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, M.E.; Bellotti, D.; Belleri, A.; Cavalieri, F.; Riva, P.; Nascimbene, R. Influence of Modelling Assumptions on the Seismic Risk of Industrial Precast Concrete Structures. Front. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 629956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, M.; Di Salvatore, C.; Bellotti, D.; Capacci, L.; Belleri, A.; Piccolo, V.; Cavalieri, F.; Dal Lago, B.; Riva, P.; Magliulo, G.; et al. Modelling and seismic response analysis of nonresidential single-storey existing precast buildings in Italy. J. Earthq. Eng. 2022, 27, 1047–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, M.; Labò, S.; Riva, P.; Belleri, A. Seismic risk and finite element modelling influence of an existing one-storey precast industrial building. J. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 27, 4182–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalha, N.; Rodrigues, H.; Sousa, R.; Varum, H. Seismic assessment of existing precast RC industrial buildings in Portugal. Struct. 2022, 41, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristic, D.; Micov, V.; Zisi, N.; Dimitrovski, T.; Zdravkovic, S. Attesting of Static and Seismic Stability of Typified Moduli of the Hall Programme of Precast RC Structural System “AMONT”, Krusce: Volume II: Quasi-Static Testing of Bearing and Deformability Chracteristics up to Failure of Characteristic Full-Scale Models of Joints of “AMONT” System; IZIIS Report 98-37; Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Seismology (IZIIS): Skopje, North Macedonia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ristic, D.; Sesov, N.; Zisi, N.; Micov, V.; Zdravkovic, S. Attesting of Static and Dynamic Stability of Typified Modules of Hall Programme of Precast RC Structural System “AMONT”, Krusce: Volume IV: Attesting Analysis of Nonlinear Dynamic Behaviour of Two-Storey Hall in AMONT System under Effect of Actual Earthquakes by Application of Verified Completely Nonlinear Model; IZIIS Report 98-39; Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Engineering Seismology (IZIIS): Skopje, North Macedonia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, I.; Velchev, D. Comparative Study of Different Linear Analysis for Seismic Resistance of Buildings According to Eurocode 8. Vibration 2025, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, E.; Cayci, B.T.; Inel, M. Comparative Study on the Linear and Nonlinear Dynamic Analysis of Typical RC Buildings. Rev. Constr. 2024, 23, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1998-1:2005; Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance—Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 1992-1-1:2004; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- ACI Committee 318. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19); American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE). Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures (ASCE/SEI 7-22); ASCE: Reston, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Computers and Structures Inc. CSI Analysis Reference Manual; Computers and Structures Inc.: Berkley, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zorić, A.; Zlatkov, D.; Trajković-Milenković, M.; Vacev, T.; Petrović, Ž. Analysis of the seismic response of an RC frame structure with lead rubber bearings. Build. Mater. Struct. 2022, 65, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatkov, D. Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Frame Structures with Semi-Rigid Connections. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Niš, Niš, Serbia, 2015. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Ristic, D. Nonlinear Behaviour and Stress-Strain Based Modeling of Reinforced Concrete Structures Under Eartquake Induced Bending and Varying Axial Loads. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Civil Engineering, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan, June 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Low, S.-G.; Tadros, M.K.; Einea, A.; Magaña, R.A. Seismic Behavior of a Six-Story Precast Concrete Office Building. PCI J. 1996, 41, 56–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Connection Type | Ulcinj–Albatros | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ml [kNm] | Mn [kNm] | φn [rad] | Kn [kNm/rad] | |

| EM4 | 764.20 | 162.74 | 0.002732 | 59,568.08 |

| EM5 (end columns) | 1249.52 | 300.00 | 0.003250 | 92,307.69 |

| EM5 (middle columns) | 972.61 | 300.00 | 0.002530 | 118,577.10 |

| EM6 | 881.53 | 233.60 | 0.000626 | 373,282.20 |

| Connection type | El Centro | |||

| Ml [kNm] | Mn [kNm] | φn [rad] | Kn [kNm/rad] | |

| EM4 | 864.37 | 167.31 | 0.003090 | 54,145.63 |

| EM5 (end columns) | 1489.64 | 300.00 | 0.003879 | 77,339.52 |

| EM5 (middle columns) | 1098.40 | 300.00 | 0.002857 | 105,005.30 |

| EM6 | 1020.24 | 243.49 | 0.000724 | 336,172.86 |

| Connection Type | Ulcinj–Albatros | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ml [kNm] | Mn [kNm] | φn [rad] | Kn [kNm/rad] | |

| EM4 (end connections) | 1164.64 | 130.12 | 0.002309 | 56,358.28 |

| EM4 (middle connections) | 934.20 | 116.07 | 0.001851 | 62,696.48 |

| EM5 (end columns) | 1046.71 | 300.00 | 0.002722 | 11,021.31 |

| EM5 (middle columns) | 1278.12 | 300.00 | 0.003324 | 9025.27 |

| EM6 | 671.13 | 306.93 | 0.011155 | 27,515.02 |

| Connection type | El Centro | |||

| Ml [kNm] | Mn [kNm] | φn [rad] | Kn [kNm/rad] | |

| EM4 (end connections) | 1294.08 | 145.51 | 0.002566 | 56,711.36 |

| EM4 (middle connections) | 1033.05 | 122.10 | 0.002048 | 59,630.79 |

| EM5 (end columns) | 1232.91 | 300.00 | 0.003207 | 93,545.37 |

| EM5 (middle columns) | 1475.09 | 300.00 | 0.003837 | 78,186.08 |

| T70 | 693.82 | 308.29 | 0.011532 | 26,733.44 |

| Earthquake | Rigid Connect. (1) | Proposed Model (2) | Nonlinear Dynamics (3) | (3)/(2) | (2)/(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ulcinj–Albatros | 0.0901 m | 0.1504 m | 0.1539 m | 1.0233 | 1.6693 |

| El Centro | 0.1099 m | 0.1287 m | 0.1242 m | 0.9650 | 1.1711 |

| Earthquake | Rigid Connect. (1) | Proposed Model (2) | Nonlinear Dynamics (3) | (3)/(2) | (2)/(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ulcinj–Albatros | 0.0787 m | 0.1137 m | 0.1168 m | 1.0273 | 1.4447 |

| El Centro | 0.0877 m | 0.1022 m | 0.0931 m | 0.9109 | 1.1653 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mladenović, B.; Zorić, A.; Zlatkov, D.; Ristic, D.; Ristic, J.; Slavković, K.; Milošević, B. Seismic Assessment of an Existing Precast Reinforced Concrete Industrial Hall Based on the Full-Scale Tests of Joints—A Case Study. Vibration 2026, 9, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010007

Mladenović B, Zorić A, Zlatkov D, Ristic D, Ristic J, Slavković K, Milošević B. Seismic Assessment of an Existing Precast Reinforced Concrete Industrial Hall Based on the Full-Scale Tests of Joints—A Case Study. Vibration. 2026; 9(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleMladenović, Biljana, Andrija Zorić, Dragan Zlatkov, Danilo Ristic, Jelena Ristic, Katarina Slavković, and Bojan Milošević. 2026. "Seismic Assessment of an Existing Precast Reinforced Concrete Industrial Hall Based on the Full-Scale Tests of Joints—A Case Study" Vibration 9, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010007

APA StyleMladenović, B., Zorić, A., Zlatkov, D., Ristic, D., Ristic, J., Slavković, K., & Milošević, B. (2026). Seismic Assessment of an Existing Precast Reinforced Concrete Industrial Hall Based on the Full-Scale Tests of Joints—A Case Study. Vibration, 9(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration9010007