Experimental Investigation of Ring-Type Resonator Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Working Principle of ASRG and Experimental Setup

3. Results

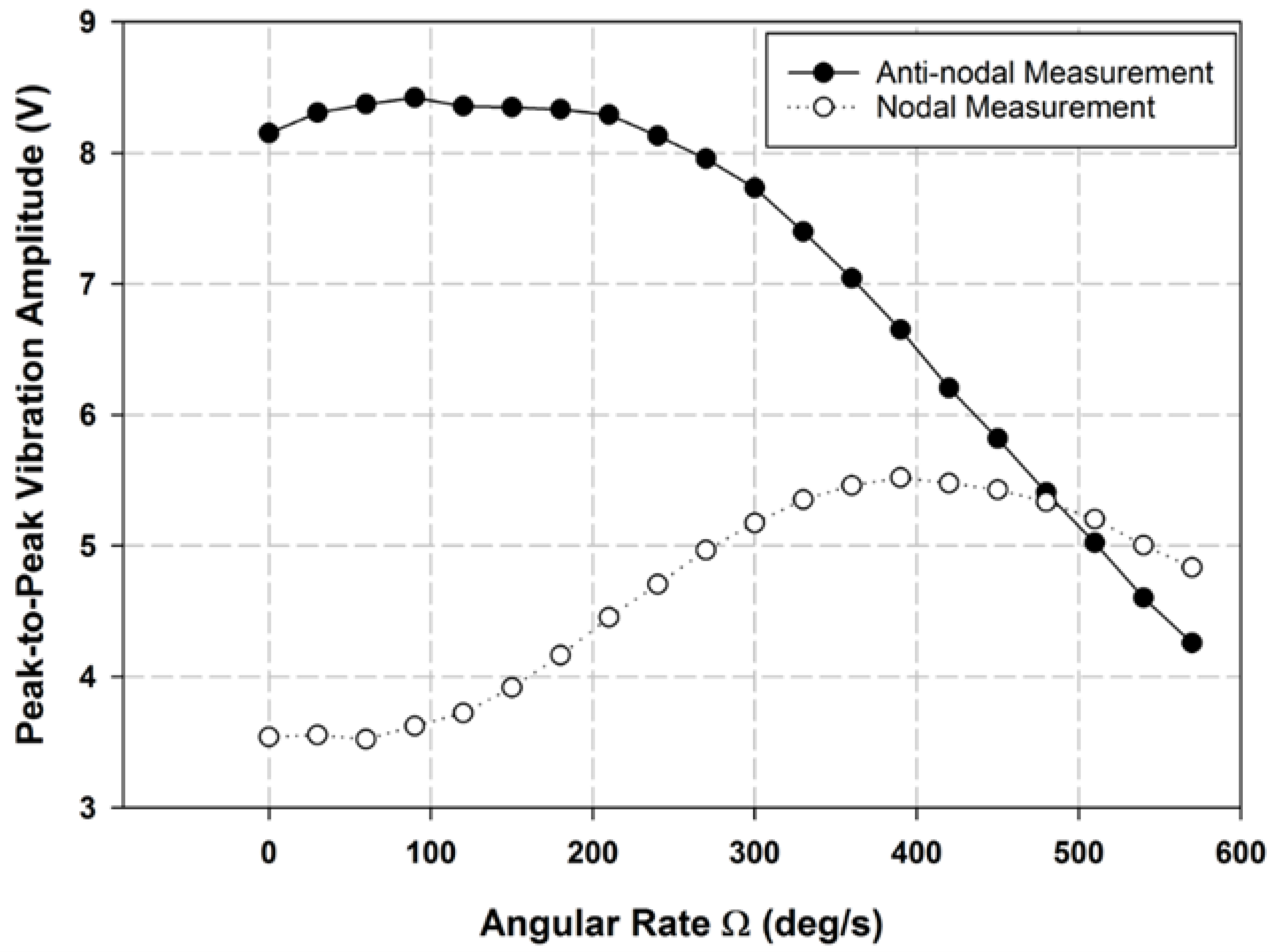

3.1. Experimental Natural Frequency Variation Due to Input Angular Rate

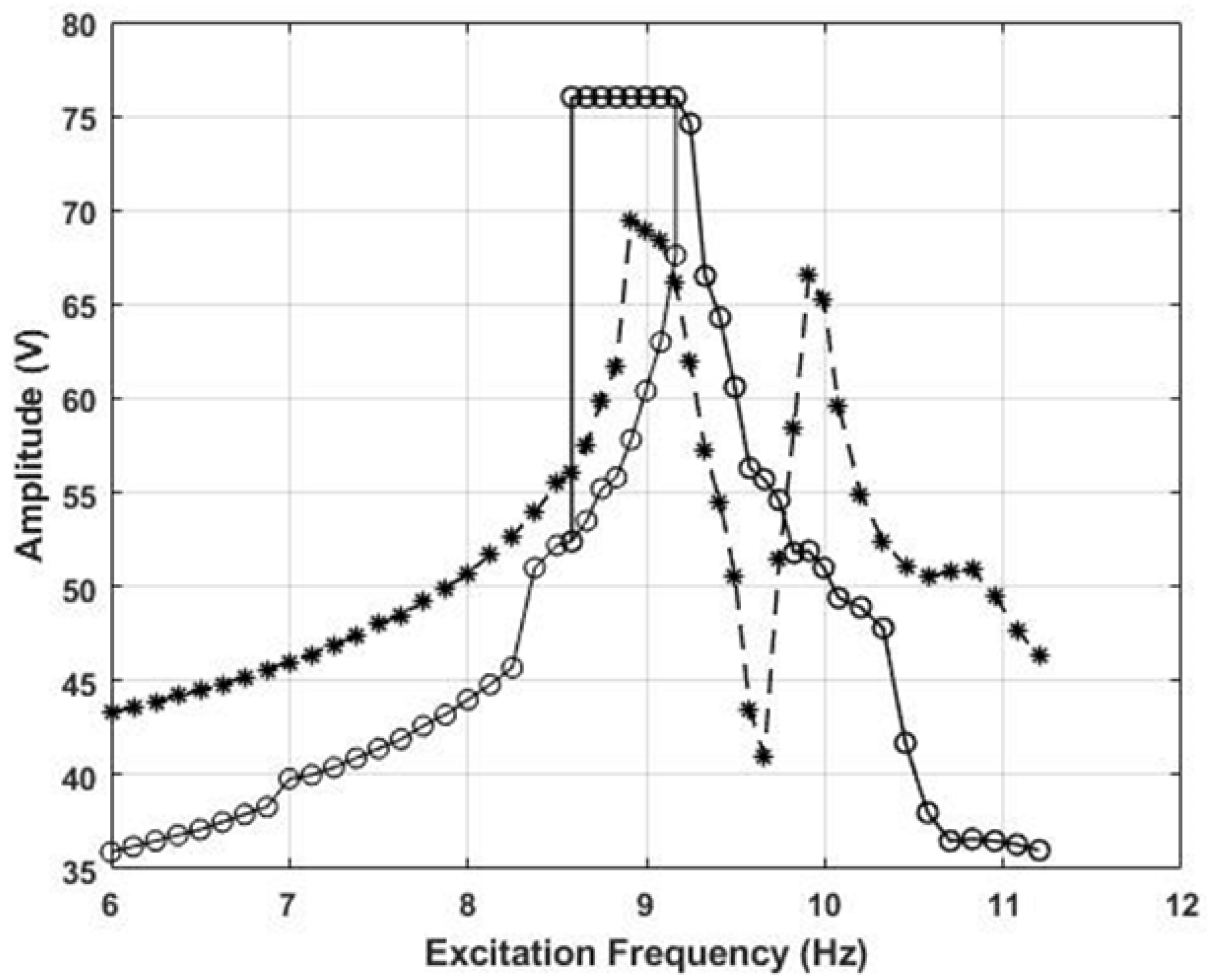

3.2. Nonlinear Frequency Response Experiments

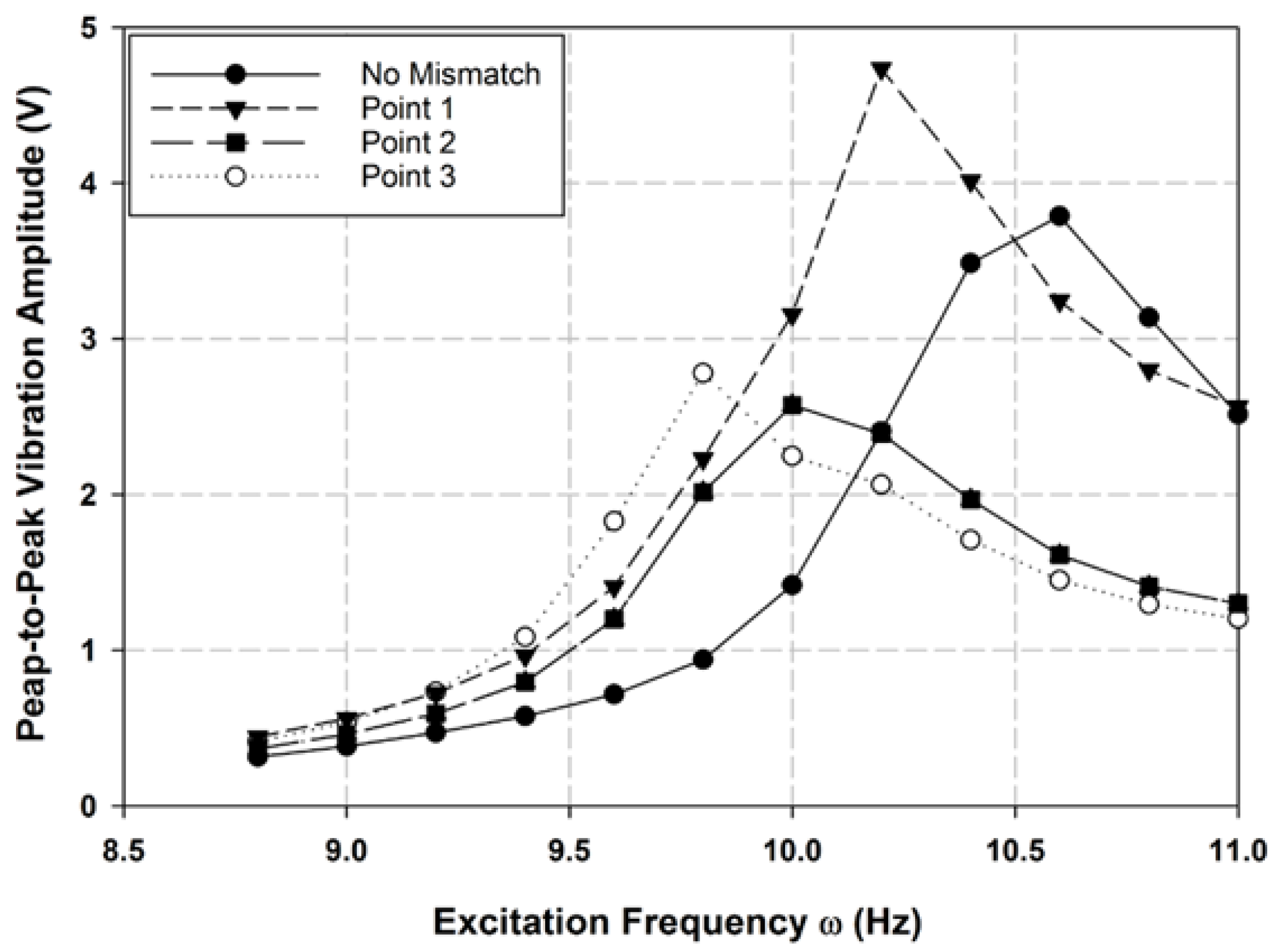

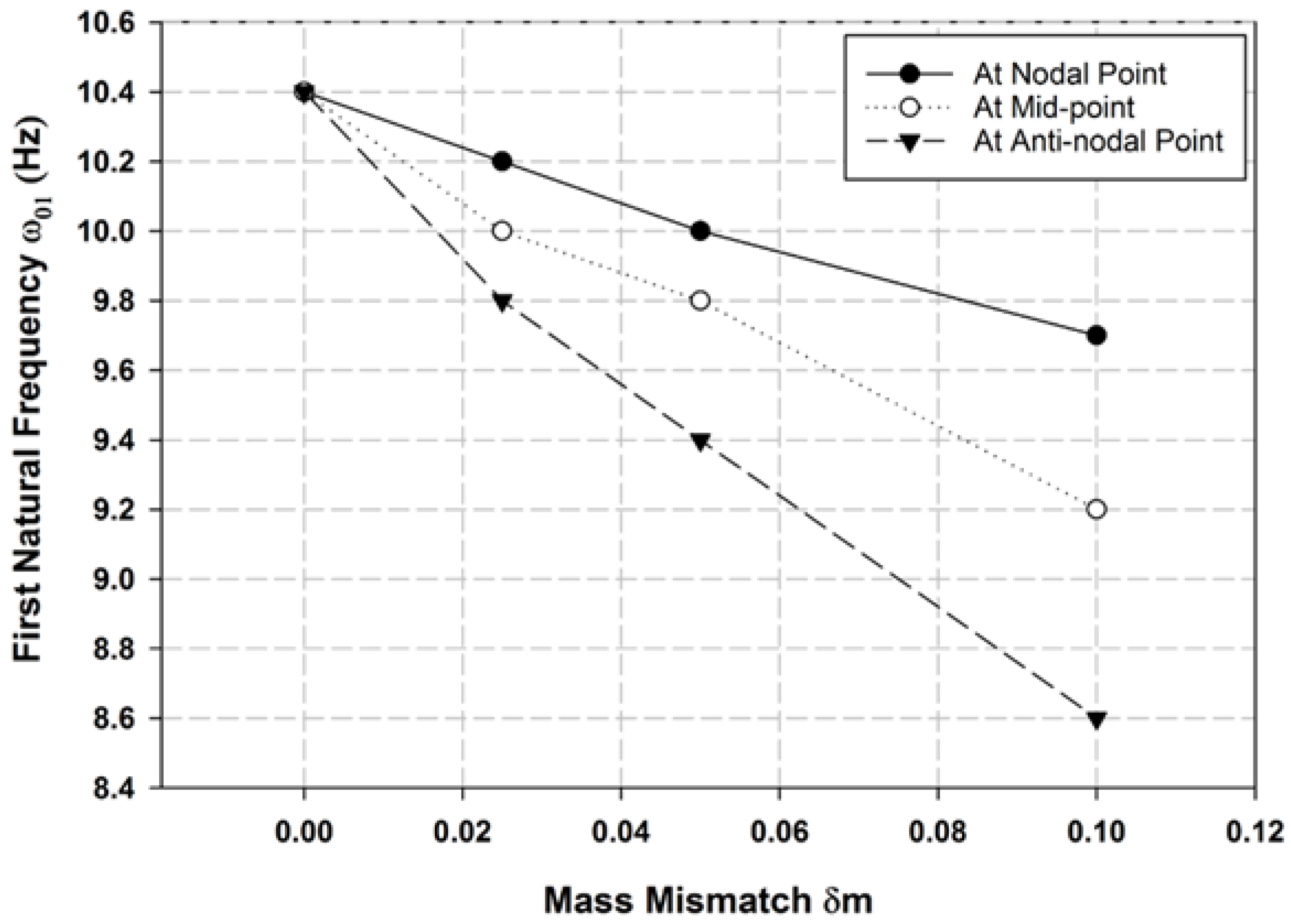

3.3. Natural Frequency Variation Due to Mass Mismatch

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Evensen, D.A. Nonlinear flexural vibrations of thin circular rings. J. Appl. Mech. 1966, 33, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, M.; Sakata, K.; Taniguchi, O. Flexural vibration of a thin rotating ring. J. Sound Vib. 1984, 92, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluf, N.; Williams, K. An Introduction to Microelectromechanical Systems Engineering; Artech House: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Asokanthan, S.; Cho, J. Dynamic stability of ring-based angular rate sensors. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 295, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A. Modern Inertial Technology—Navigation, Guidance, and Control; NASA STI/Recon Technical Report A; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Volume 93, p. 39795. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, H.; Yaralioglu, G.G. Analysis of Vibratory Gyroscopes: Drive and Sense Mode Resonance Shift by Coriolis Force. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Soedel, W. Effects of Coriolis acceleration on the free and forced in-plane vibrations of rotating rings on elastic foundation. J. Sound Vib. 1987, 115, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eley, R.; Fox, C.; McWilliam, S. Coriolis coupling effects on the vibration of rotating rings. J. Sound Vib. 2000, 238, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammer, C.; Schlack, A., Jr. Effects of nonconstant spin rate on the vibration of a rotating beam. J. Appl. Mech. 1987, 54, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, C.G.; Parker, R.G. Limitations of an inextensible model for the vibration of high-speed rotating elastic rings with attached space-fixed discrete stiffnesses. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2015, 54, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokanthan, S.; Ariaratnam, S.; Cho, J.; Wang, T. MEMS vibratory angular rate sensors: Stability considerations for design. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2006, 13, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokanthan, S.; Wang, T. Instabilities in a MEMS gyroscope subjected to angular rate fluctuations. J. Vib. Control 2009, 15, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Qu, T.; Yang, K.; Luo, H. Monolithic Cylindrical Fused Silica Resonators with High Q Factors. Sensors 2016, 16, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhou, G.; Qu, T.; Luo, H.; Zhang, B. Annealing Experiments on the Quality Factor of Fused Silica Cylindrical Shell Resonator. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Inertial Sensors and Systems (INERTIAL), Naples, FL, USA, 1–5 April 2019; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gebrel, I.; Bognash, M.; Pan, Y.; Liu, F.; Asokanthan, S.; Luo, H.; Qu, T. Dynamic Response and Frequency Split Predictions for Cylindrical Fused Silica Resonators. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 20, 3460–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Qiu, Z.; Pan, Y.; Li, S.; Qu, T.; Tan, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Zhao, W.; Luo, H.; et al. Influence of Electrostatic Forces on the Vibrational Characteristics of Resonators for Coriolis Vibratory Gyroscopes. Sensors 2020, 20, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Pan, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Fan, Z.; Xiao, G.; Yu, X.; Luo, H.; Asokanthan, S. Observation and Prediction for Frequency Split of Cylindrical Resonator Gyroscopes Subject to Varying Angular Velocity. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Inertial Sensors and Systems (INERTIAL), Hiroshima, Japan, 23–26 March 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhong, H.; Lu, Y.; Duan, J.; Sun, X. Laser Trimming Method for Reducing Frequency Split of Cylindrical Vibrating Gyroscope. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 793, 12027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhlyarsky, D.; Sorokin, F.; Gouskov, A.; Basarab, M.; Lunin, B. Approximation Method For Frequency Split Calculation of Coriolis Vibrating Gyroscope Resonator. J. Sound Vib. 2022, 526, 116733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarab, M.; Lunin, B.; Vakhlyarskiy, D.; Chumankin, E. Investigation of Nonlinear High-Intensity Dynamic Processes in a Non-ideal Solid-State Wave Gyroscope Resonator. In Proceedings of the 27th Saint Petersburg International Conference on Integrated Navigation Systems (ICINS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 25–27 May 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Fu, M.; Deng, Z.; Liu, N.; Liu, H. Frequency Split Elimination Method for a Solid-State Vibratory Angular Rate Gyro with an Imperfect Axisymmetric-Shell Resonator. Sensors 2015, 15, 3204–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, K.; Hu, Y.; Deng, G.; Sun, X.; Su, W.; Lu, Y.; Duan, J. Investigation on Eigenfrequency of a Cylindrical Shell Resonator under Resonator-Top Trimming Methods. Sensors 2017, 17, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarab, M.A.; Lunin, B.S.; Matveev, V.A. Static balancing of metal resonators of cylindrical resonator gyroscopes. Gyroscopy Navig. 2014, 5, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Tao, Y.; Pan, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Luo, H. Experimental Study on Variation of Surface Roughness and Q Factors of Fused Silica Cylindrical Res onators with Different Grinding Speeds. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, T.; Shen, C.; Cao, H. Research on Frequency Splitting Analysis and Tuning Methods of Six-Antinode Cylindrical Resonator Gyroscope. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 2568–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Xie, Y.; Qi, Z.; Xi, B. Modeling of acceleration influence on hemispherical resonator gyro forcing system. Math. Probl. Eng. 2015, 2015, 104041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempe, V. Inertial MEMS: Principles and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, J. Nonlinear Instabilities in Ring-Based Vibratory Angular Rate Sensors. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arghavan, S. Stochastic Stability and Uncertainty Quantification of Ring-Based Vibratory Gyroscopes. Master’s Thesis, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Density, ⍴ | 7833.41 kg/m3 |

| Young’s modulus, E | 206.84 × 109 N/m2 |

| Mean radius, r | 92.5 mm |

| Radial thickness, h | 0.1016 mm |

| Thickness-to-Radius Ratio, h/r | 0.001 |

| Axial Length, L | 150 mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdulla, A.F.; Arghavan, S.; Cho, J.; Gebrel, I.F.; Bognash, M.; Asokanthan, S.F. Experimental Investigation of Ring-Type Resonator Dynamics. Vibration 2025, 8, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040067

Abdulla AF, Arghavan S, Cho J, Gebrel IF, Bognash M, Asokanthan SF. Experimental Investigation of Ring-Type Resonator Dynamics. Vibration. 2025; 8(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulla, Ali F., Soroush Arghavan, Jihyun Cho, Ibrahim F. Gebrel, Mohamed Bognash, and Samuel F. Asokanthan. 2025. "Experimental Investigation of Ring-Type Resonator Dynamics" Vibration 8, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040067

APA StyleAbdulla, A. F., Arghavan, S., Cho, J., Gebrel, I. F., Bognash, M., & Asokanthan, S. F. (2025). Experimental Investigation of Ring-Type Resonator Dynamics. Vibration, 8(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/vibration8040067