Study on the Risk Zone of Hydrogen Leak Diffusion in High-Pressure Hydrogen Transmission Pipeline Station Fields

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model

2.1. Model Assumptions

- (1)

- Hydrogen and air are treated as ideal gases, undergoing no chemical reactions with other substances and obeying the ideal gas equation of state. This assumption provides reasonable accuracy at ambient temperatures and pressures below 10 MPa, focusing on the leakage and dispersion phase for flammable gas cloud assessment. Modifications would be necessary for scenarios involving extremely low temperatures, very high pressures, or combustion.

- (2)

- Leakage from the hydrogen pipeline station is modeled as a continuous release, and internal pipeline flow dynamics are not considered.

- (3)

- During continuous leakage, the mass flow rate and velocity of hydrogen at the leakage orifice remain constant.

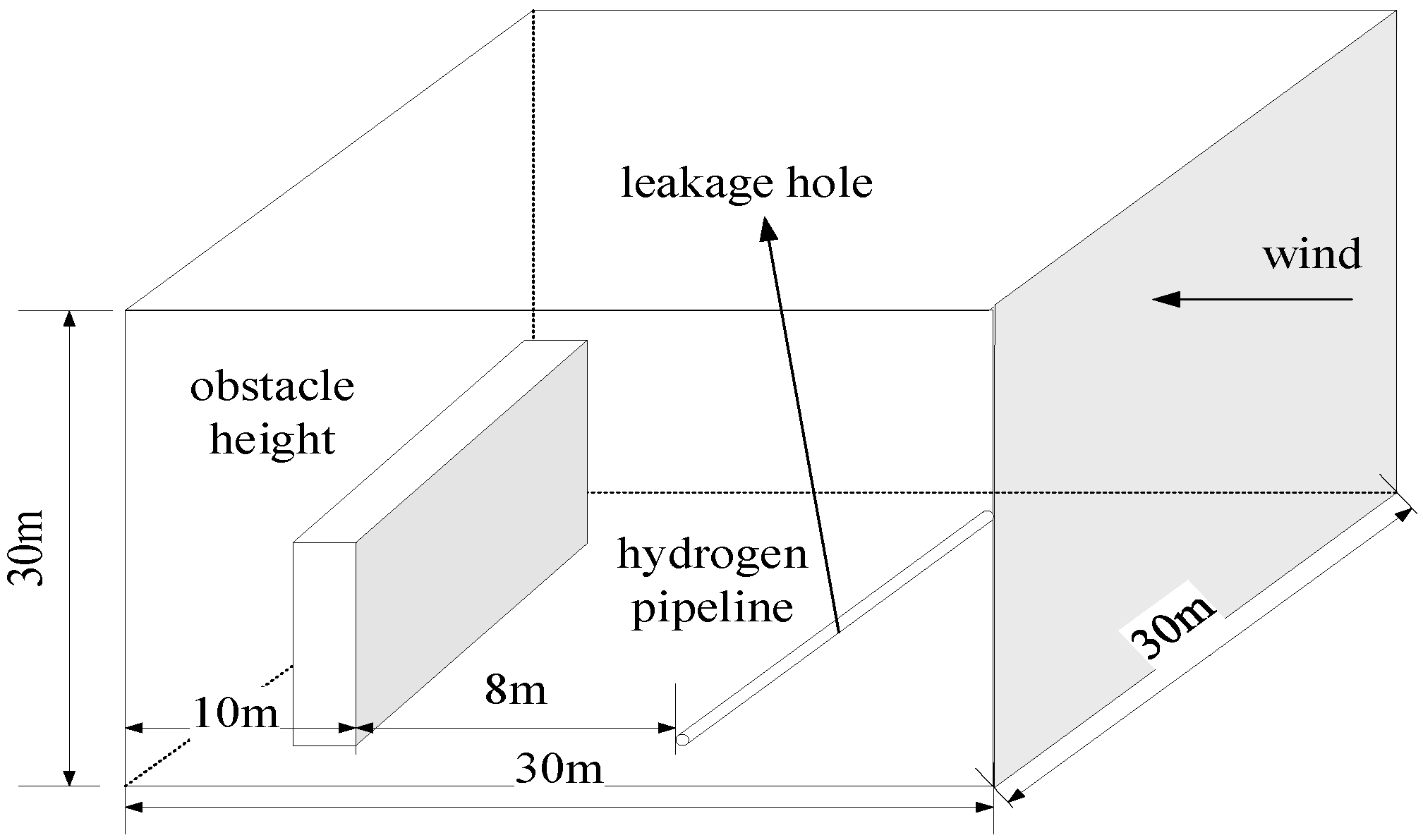

2.2. Physical Model

2.3. Mathematical Model

- ●

- Continuity Equation:

- ●

- Momentum Equation:

- ●

- Energy Equation:

- ●

- Gas State Equation:

- ●

- Component Transport Equation:

2.4. Boundary Conditions

- ●

- A pressure inlet at the leakage point, set to the pipeline operating pressure.

- ●

- A velocity inlet on the right-side boundary of the domain.

- ●

- Pressure outlets on the surrounding boundaries, set to atmospheric pressure.

- ●

- Wall boundaries for the pipeline, ground, and structures.

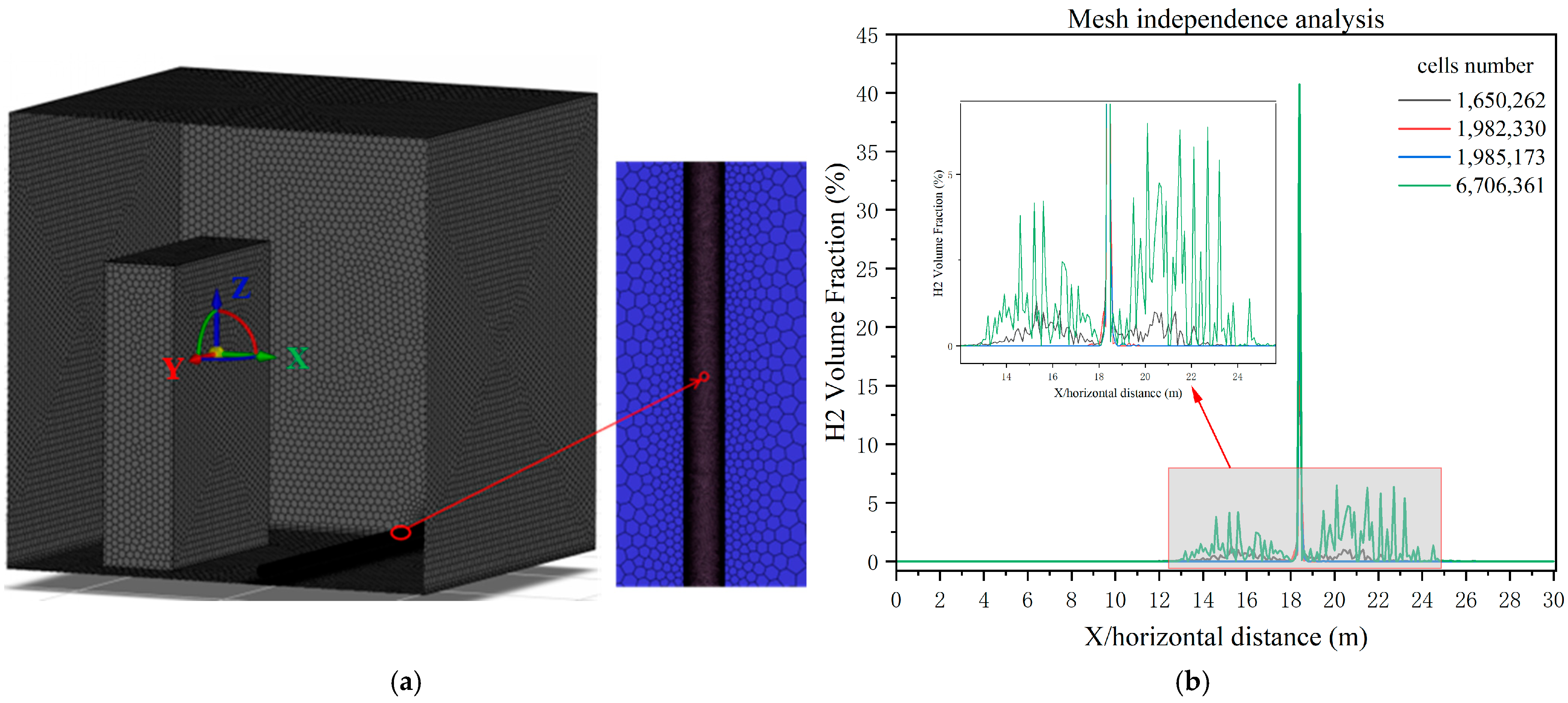

2.5. Mesh Generation and Computational Setup

- ●

- Solver Type: Pressure-based transient solver

- ●

- Pressure-Velocity Coupling: PISO scheme

- ●

- Spatial Discretization: Second-order upwind scheme for momentum and species transport

- ●

- Multiphase Model: Volume of Fluid (VOF) method for simulating hydrogen dispersion in air

- ●

- Turbulence Model: Standard k–ε model with scalable wall functions

- ●

- Gravity: Enabled to account for buoyancy effects due to the low density of hydrogen (0.08988 kg/m3 under standard conditions)

- ●

- Time Step Size: Set to 0.1 s to adequately capture hydrogen concentration variations while accommodating computational performance constraints.

2.6. Scenarios

3. Hydrogen Leakage Dispersion Patterns

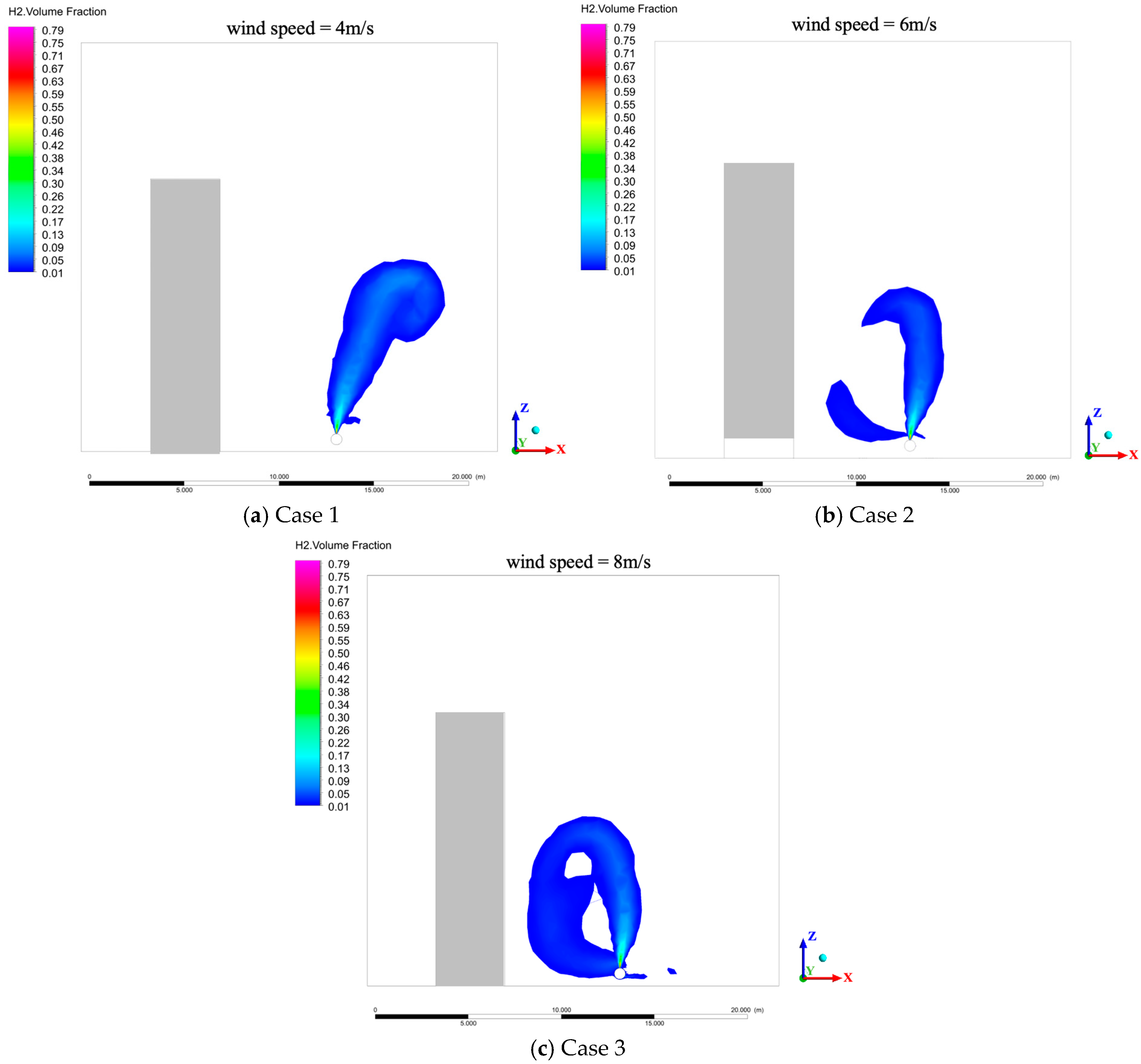

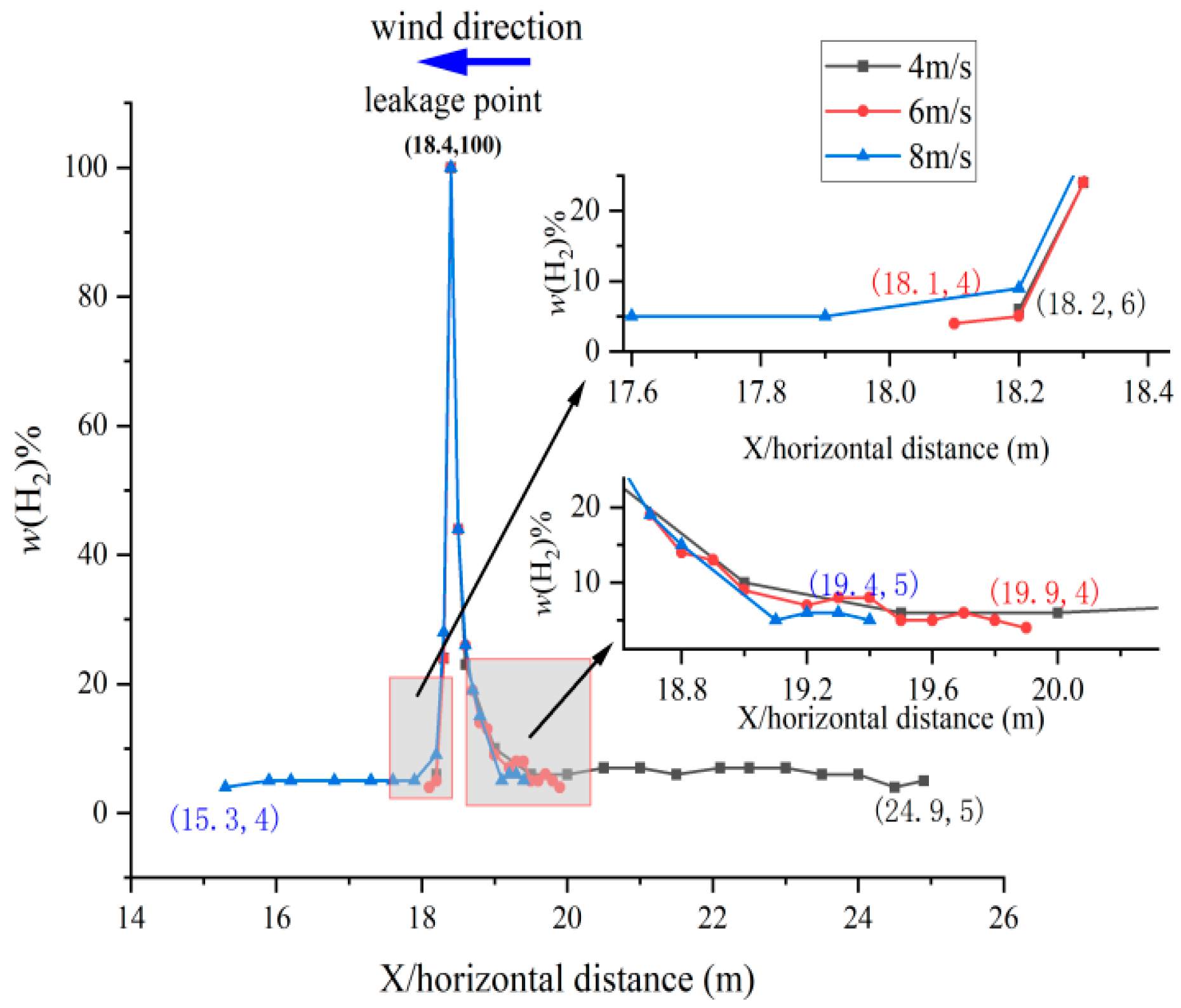

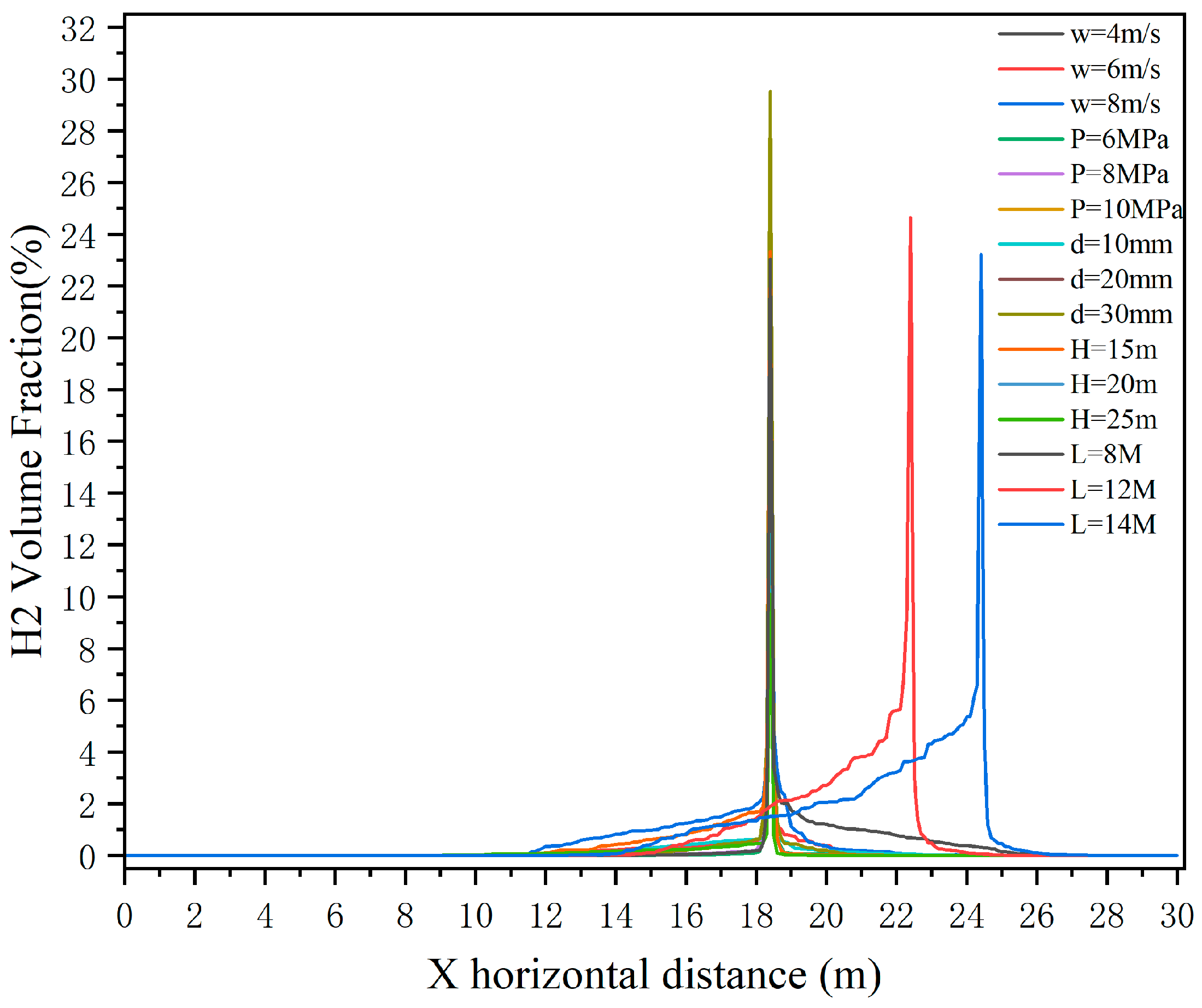

3.1. Effect of Wind Speed

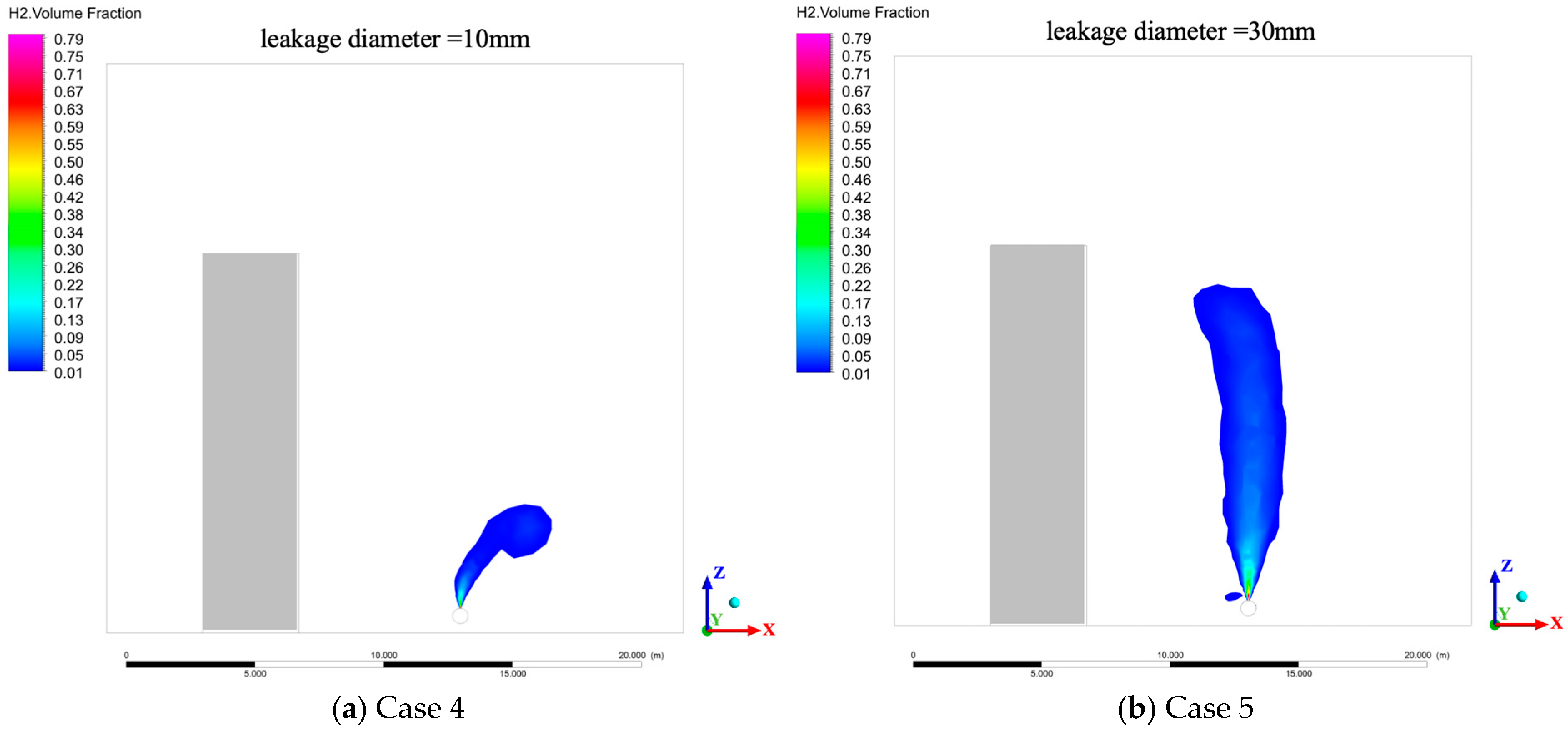

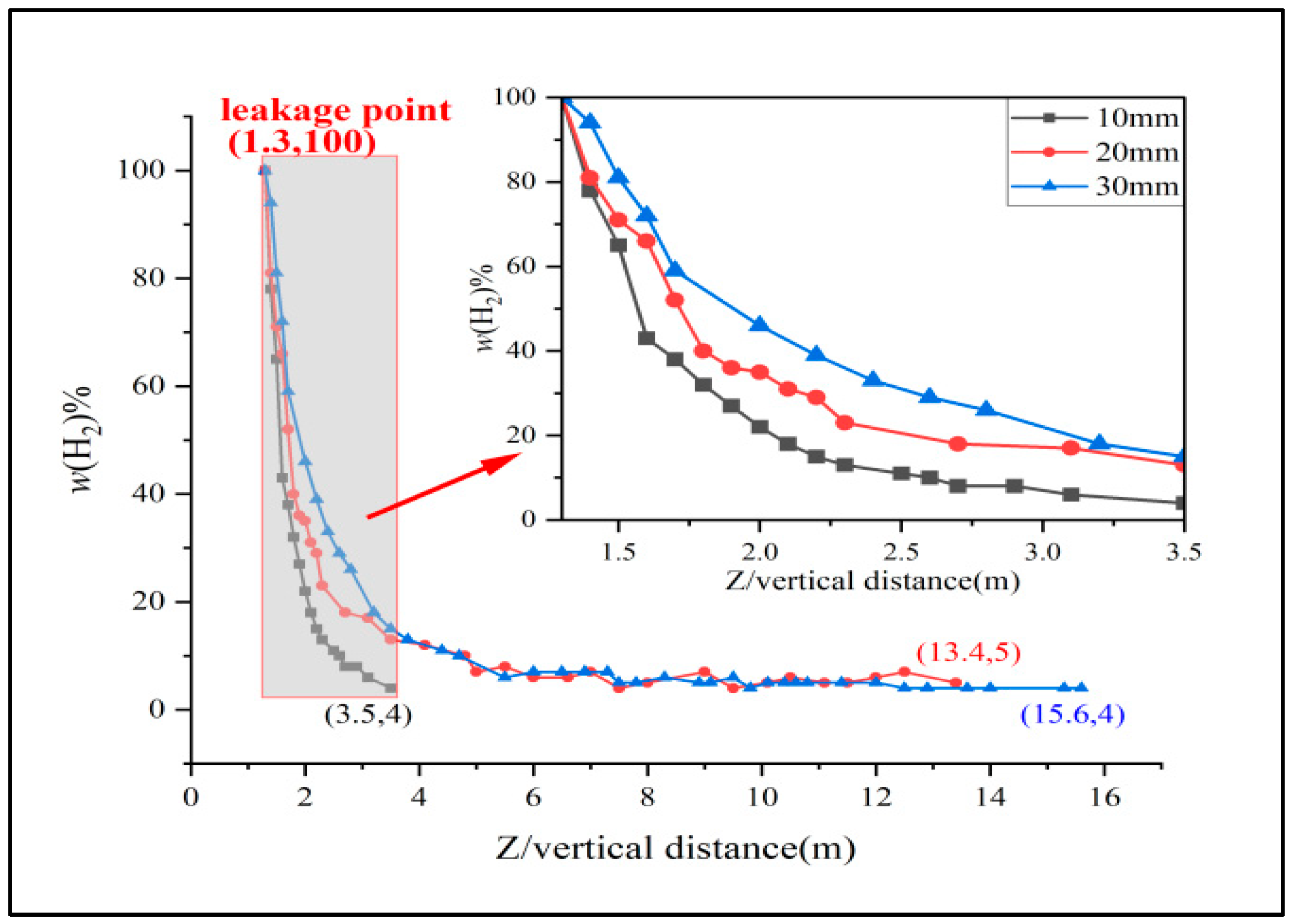

3.2. Effect of Leakage Orifice Diameter

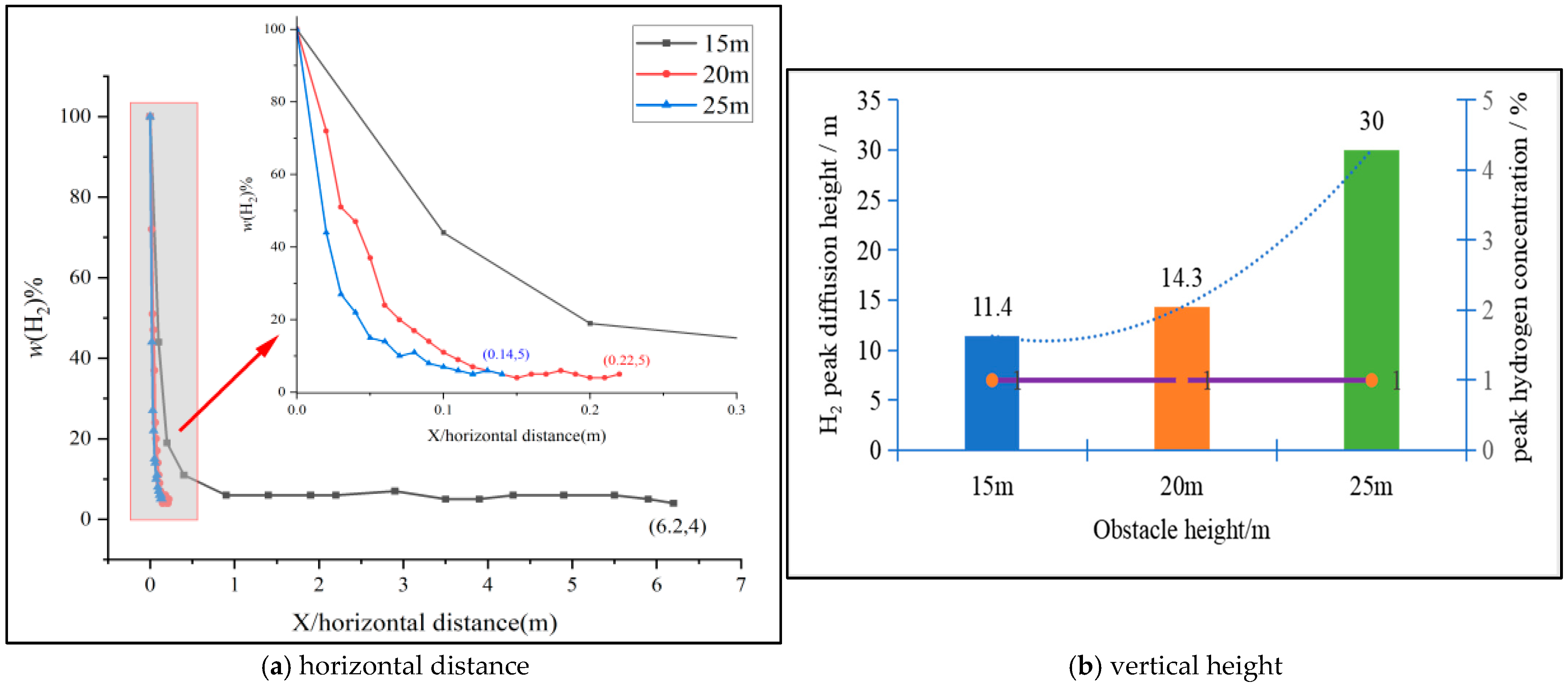

3.3. Effect of Obstacle Height

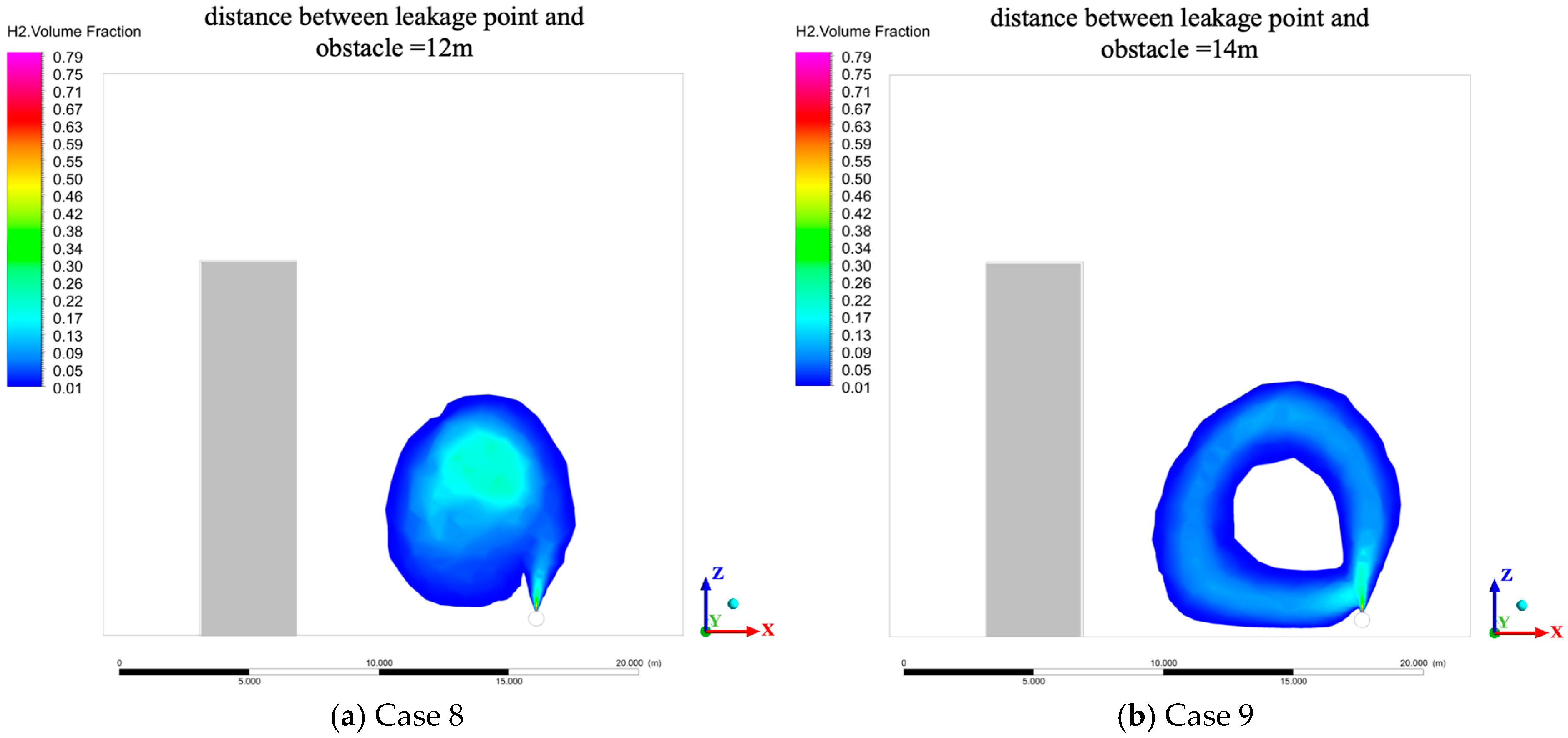

3.4. Effect of Leakage Source-Obstacle Spacing

3.5. Effect of Pipeline Operating Pressure

3.6. Hazard Radius Prediction

3.6.1. Model Form

3.6.2. Model Development Based on Statistical Significance

- ●

- Obstacle blocking effect: The obstacles within the station significantly alter the flow structure and turbulent transport process, creating a pronounced physical blockage to the dispersion of the hydrogen cloud. This effect is identified as a critical engineering factor in controlling the hazard radius.

- ●

- Identification of dominant parameters: Obstacle height and its relative distance to the leakage source are confirmed as the two controlling variables influencing the evolution of the hazard radius. Their interaction governs the spatial distribution pattern and dispersion path of the flammable cloud.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Obstacle-Dominated Dispersion Mechanisms: The presence and structural parameters of obstacles (height H and leakage-obstacle distance L) are identified as the dominant factors governing the evolution of the hazard radius, overshadowing the direct influences of wind speed, leakage diameter, and operating pressure in scenarios with complex station layouts. Obstacles fundamentally reshape the leakage flow field by inducing physical blockage, guiding vertical deflection, and enhancing turbulent mixing, which collectively control the flammable cloud’s dispersion path and accumulation pattern.

- (2)

- Development of a Novel Predictive Model: Moving beyond traditional empirical correlations that rely on source and environmental parameters, this research innovatively established a simplified yet highly accurate hazard radius prediction model based on multivariate nonlinear regression. Its high accuracy, validated against independent scenarios, demonstrates robust predictive capability and superior engineering applicability.

- (3)

- Quantification of Parametric Influences: The effects of key operating and environmental factors were quantitatively elucidated. Increases in wind speed and pipeline pressure were found to enhance the initial jet momentum, leading to extended downwind dispersion distances and higher local concentrations. Conversely, larger leakage orifice diameters promoted vertical diffusion and increased the volume of the near-field flammable cloud. A critical finding is that a larger leakage-obstacle distance, while reducing immediate concentration buildup, ultimately results in a broader hazardous area due to reduced flow obstruction.

- (4)

- Guidance for Establishing Safety Distances: The simulation results demonstrate significant practical value for engineering safety design. The maximum hazardous horizontal dispersion distance (to the 4%vol. hydrogen concentration contour) observed across all simulated scenarios is 10.9 m. This empirically derived distance is notably smaller than the fire separation distances stipulated in the Chinese national standard GB 50516-2021 [28] Technical Code for Hydrogen Refueling Stations (e.g., 50 m from storage equipment to important public buildings, and 30–40 m from open flames). Crucially, this maximum predicted distance aligns with the code’s provision that safety distances may be reduced by half, but to no less than 8 m, when qualified physical protection walls are installed. This concordance confirms that the proposed model and findings provide a scientifically grounded and practical methodology for optimizing safety distances in hydrogen pipeline stations and refueling stations, enabling more efficient land use without compromising safety.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lebrouhi, B.E.; Djoupo, J.J.; Lamrani, B.; Benabdelaziz, K.; Kousksou, T. Global hydrogen development—A technological and geopolitical overview. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 7016–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.B.; Xiu, G.L.; Wu, S.Z. Experimental study on the explosion characteristics of methane/air mixtures with hydrogen addition. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 120, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, D.; Xydis, G. A literature review on hydrogen refuelling stations and infrastructure. Current status and future prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 113, 109292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Wang, C.X.; Han, M.X.; Xu, Z. A study on the characteristics of the deflagration of hydrogen-air mixture under the effect of a mesh aluminum alloy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 299, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.B.; Wang, Q.S.; Xiao, H.H.; Sun, J. Experimental study on the characteristics stages of premixed hydrogen-air flame propagation in a horizontal rectangular closed duct. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 12028–12038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makoto, H.; Hiroki, S.; Naoya, K.; Otaki, T. Comparative risk study of hydrogen and gasoline dispensers for vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 12584–12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.Y.; Yuan, Y.P.; Liang, T.; Shen, B. Numerical simulation of hydrogen leakage diffusion in seaport hydrogen refueling station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 24521–24535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Azuma, T.; Ecans, J.A.; Cronin, P.M.; Johnson, D.M.; Cleaver, R.P. Experimental study on hydrogen explosions in a full-scale hydrogen filling station model. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 2162–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjold, T.; Siccama, D.; Hisken, H.; Brambilla, A.; Middha, P.; Groth, K.M.; LaFleur, A.C. 3D risk management for hydrogen installations. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 7721–7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.F.; Liang, P.; Yu, H.S.; Dai, M.; Li, Y. Modeling the diffusion of flammable hydrogen cloud under different liquid hydrogen leakage conditions in a hydrogen refueling station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 25849–25863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, U.; Oh, J.; Lee, H. Safety investigation of hydrogen charging platform package with CFD simulation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 13687–13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Park, J.; Cho, J.; Moon, I. Simulation of hydrogen leak and explosion for the safety design of hydrogen fueling station in Korea. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 1737–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.X.; Chen, S.Q.; Liu, Y.; Guan, B.; Wang, X.; Shi, Z.; Hao, G. CFD analysis and calculation models establishment of leakage of natural gas pipeline considering real buried environment. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 3789–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Yang, Y.L.; Wu, F.G.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Che, D.; Huang, Z. Numerical investigation on pinhole leakage and diffusion characteristics of medium-pressure buried hydrogen pipeline. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.Y.; Yang, S.Y.; Yuan, Y.L.; Jia, H.; Zheng, L.; Liang, C. Study on the difference of dispersion behavior between hydrogen and methane in utility tunnel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 8130–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, X.W.; Du, H.M.; Teng, L.; Shao, Y.; Bian, J. Numerical simulation of leakage and diffusion distribution of natural gas and hydrogen mixtures in a closed container. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 35928–35939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.L.; Pan, J.; Zhang, Y.X.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Feng, H.; Chen, D.; Kou, Y.; Yang, R. Leakage and diffusion behavior of a buried pipeline of hydrogen-blended natural gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 11592–11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, K.; Song, B.; Jiao, W.L.; Yu, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H.; Du, J. Quantitative risk assessment of gas leakage and explosion accidents and its security measures in open kitchens. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 130, 105763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Jiao, W.L.; Cen, K.; Tian, X.; Zhang, H.; Lu, W. Quantitative risk assessment of gas leakage and explosion accident consequences inside residential buildings. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 122, 105257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, R.S.; Patrick, F.; Eric, S.G.; Swain, M.N. Hydrogen leakage into simple geometric enclosures. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2003, 28, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Pan, X.M.; Zhang, C.M.; Xie, B.; Liu, S. The simulation and analysis of leakage and explosion at a renewable hydrogen refuelling station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 22608–22619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.Y.; Li, X.J.; Gao, Z.X.; Jin, Z.-J. A numerical study of hydrogen leakage and diffusion in a hydrogen refueling station. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 25, 14418–14439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Chen, T.; Liu, Z. Real-Time Global Optimal Energy Management Strategy for Connected PHEVs Based on Traffic Flow Information. In Proceedings of the 2024 World Congress on Internal Combustion Engines, Tianjin, China, 19–23 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Hao, G.; Guan, B. Analysis of natural gas leakage diffusion characteristics and prediction of invasion distance in utility tunnels. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 96, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.C.; Yang, Q.S.; Zhang, J. LES study of turbulent boundary layers over three-dimensional hills. Eng. Mech. 2019, 36, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D. Numerical Simulation of Natural Gas Pipeline Leakage; An Hui University of Science and Technology: Huainan, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, B.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Li, J.; Li, P.; Liu, N.; Yang, J.; Chen, X. Study on the hydrogen leakage and diffusion behavior of long-distance high-pressure buried pure-hydrogen pipelines. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 141, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50516-2021; Technical Code for Hydrogen Refueling Stations. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China & State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2021.

| Case | Wind Speed (m/s) | Leak Diameter (mm) | Obstacle Height (m) | Leak-Obstacle Spacing (m) | Operating Pressure (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Reference) | 4 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 10 |

| 2 | 6 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 10 |

| 3 | 8 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 10 |

| 4 | 4 | 10 | 20 | 8 | 10 |

| 5 | 4 | 30 | 20 | 8 | 10 |

| 6 | 4 | 20 | 15 | 8 | 10 |

| 7 | 4 | 20 | 25 | 8 | 10 |

| 8 | 4 | 20 | 20 | 12 | 10 |

| 9 | 4 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 10 |

| 10 | 4 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 8 |

| 11 | 4 | 20 | 20 | 8 | 6 |

| Case | Wind Speed (m/s) | Leak Diameter (mm) | Obstacle Height (m) | Leak-Obstacle Spacing (m) | Operating Pressure (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 4 | 20 | 17 | 5 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Sun, B.; Chu, S.; Zhao, T.; Li, N.; Zhang, L. Study on the Risk Zone of Hydrogen Leak Diffusion in High-Pressure Hydrogen Transmission Pipeline Station Fields. Fire 2025, 8, 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120464

Wang Y, Sun B, Chu S, Zhao T, Li N, Zhang L. Study on the Risk Zone of Hydrogen Leak Diffusion in High-Pressure Hydrogen Transmission Pipeline Station Fields. Fire. 2025; 8(12):464. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120464

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yajie, Bingcai Sun, Shengli Chu, Tao Zhao, Na Li, and Laibin Zhang. 2025. "Study on the Risk Zone of Hydrogen Leak Diffusion in High-Pressure Hydrogen Transmission Pipeline Station Fields" Fire 8, no. 12: 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120464

APA StyleWang, Y., Sun, B., Chu, S., Zhao, T., Li, N., & Zhang, L. (2025). Study on the Risk Zone of Hydrogen Leak Diffusion in High-Pressure Hydrogen Transmission Pipeline Station Fields. Fire, 8(12), 464. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120464