Type IV High-Pressure Composite Pressure Vessels for Fire Fighting Equipment: A Comprehensive Review and Market Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

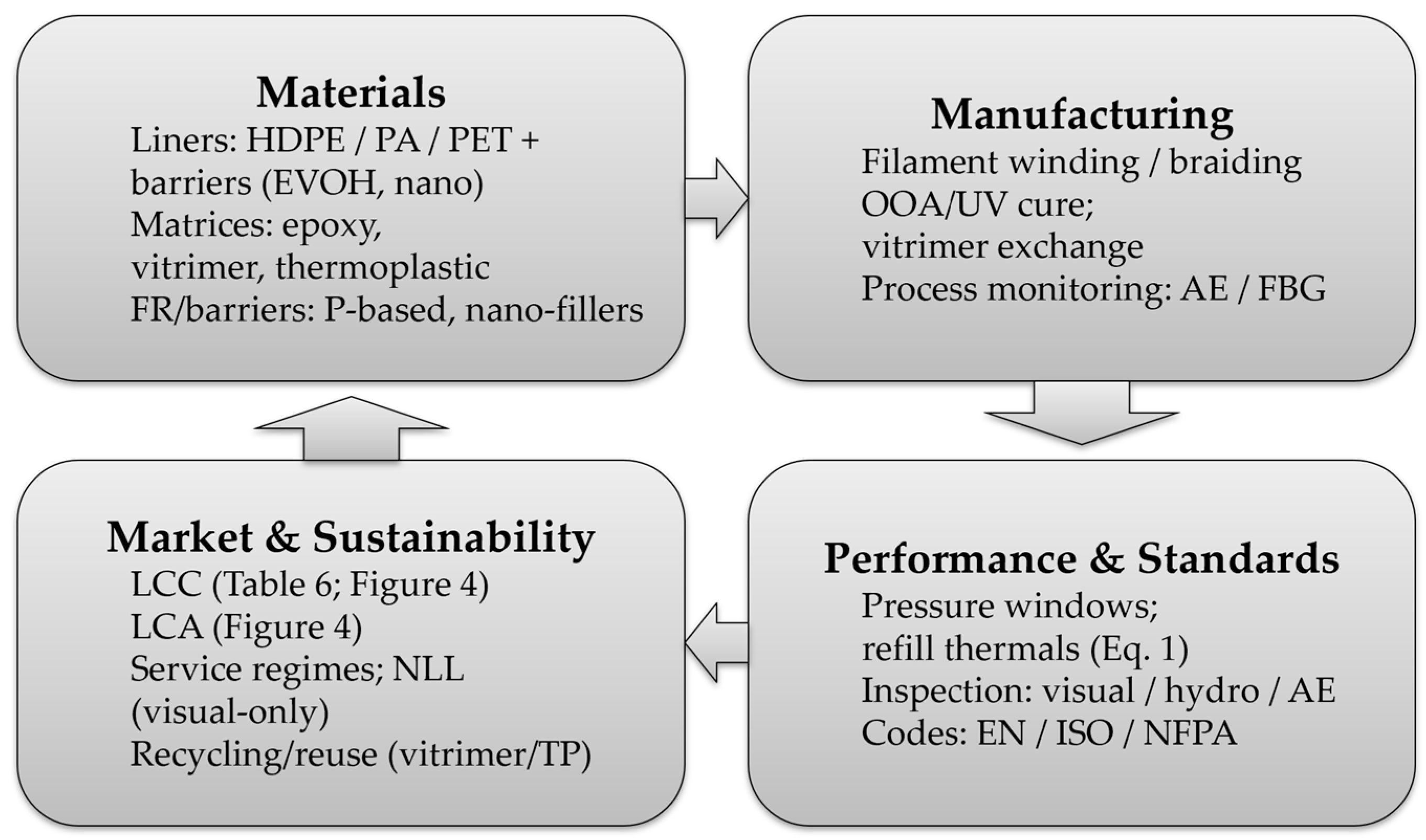

2. Material and Manufacturing Innovations

2.1. Liner Innovations

2.1.1. High-Performance Polymers

2.1.2. Polymer Nanocomposites

2.1.3. Multilayer Liner Systems

2.2. Composite Shell Advances

2.2.1. Hybrid Fiber Overwraps

2.2.2. Toughened and Fire-Resistant Resins

2.2.3. Emerging Vitrimer and Thermoplastic Matrices

2.3. Manufacturing Developments

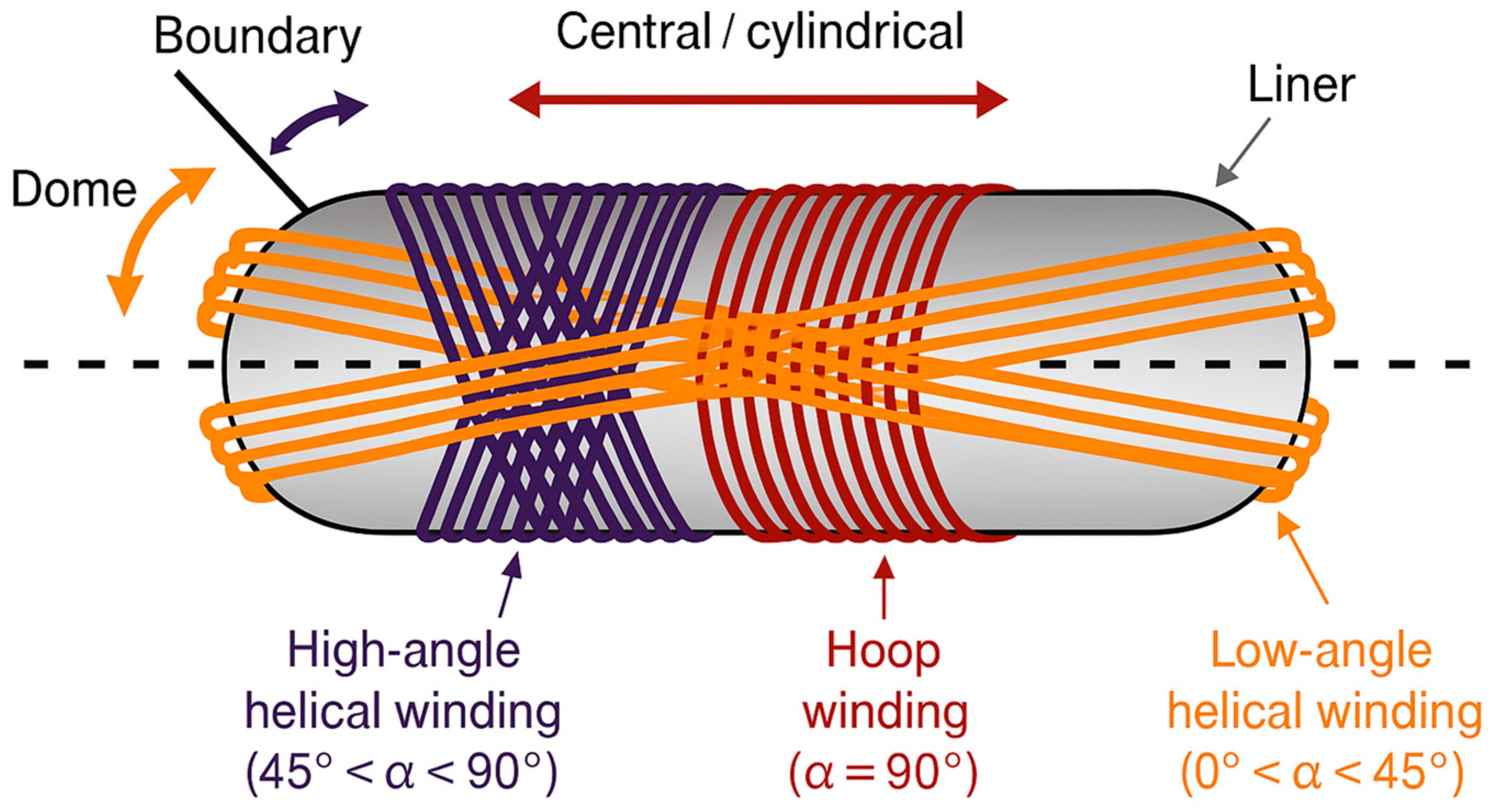

2.3.1. Advanced Filament Winding and Braiding

2.3.2. Out-of-Autoclave Curing

2.3.3. In-Line Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

3. Technical Review of Type IV Cylinders for Fire Applications

3.1. Standards and Certification (EU and Non-EU)

3.2. Design Pressures and Performance Considerations

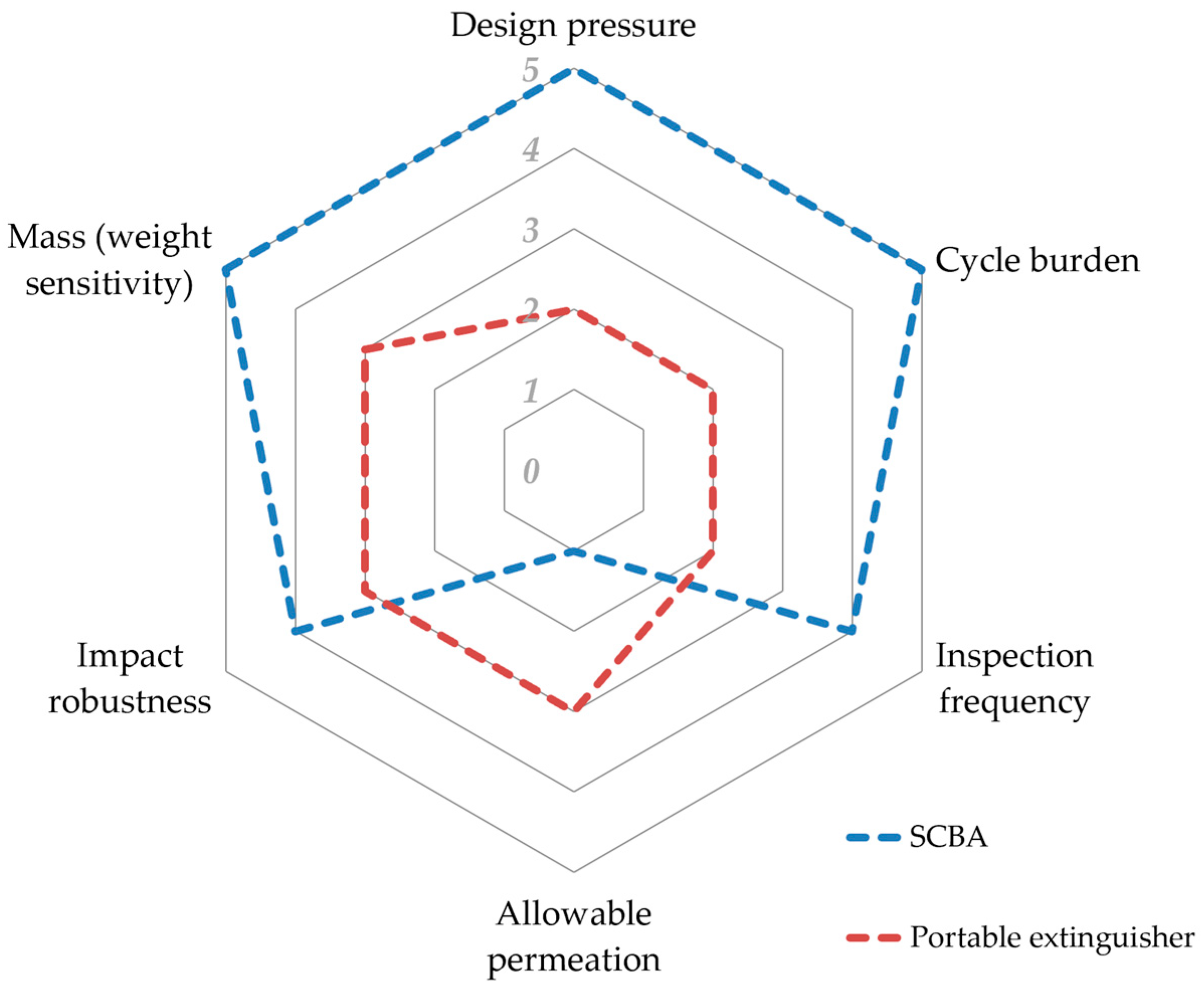

3.2.1. SCBA Cylinders

3.2.2. Portable Extinguishers

3.2.3. Design Factor and Stress Rupture

3.2.4. Thermal Performance

3.2.5. Refill and Cycle Performance

3.3. Failure Modes and Inspection Criteria

3.3.1. Fiber Breakage and Fatigue

3.3.2. Matrix Cracking and Delamination

3.3.3. Liner–Composite Interface Debonding

3.3.4. Environmental Degradation

- Visual external inspection: Look for cuts, gouges, or abrasions. Any fiber exposure or cut that goes deeper than the outer resin and cuts fiber is cause for rejection. Thresholds may be given (e.g., if cut length > 25 mm or depth > 1.5 mm, reject) [16].

- Check for soft spots or bulges: Press the surface with a thumb; a spongy feel in one area can indicate delamination. A bulge that remains when depressurized indicates a blister or liner collapse.

- Inspect the neck and boss: Remove the valve during periodic test; check the liner’s lip for cracks or deformation. Make sure the metal boss has not loosened or shifted (which could indicate loss of structural support).

- Hydrostatic test results: During hydro test, note the permanent expansion. Composite cylinders typically have slightly higher expansion than steel, but it should be mostly elastic. If permanent expansion exceeds a certain percentage of the total (often 5% of total expansion), the cylinder fails. This can catch fiber/matrix damage not visible externally.

- Leak check: After reassembly, a sensitive leak test (e.g., helium sniff test or soapy water) around the boss and overwrap surface ensures no through-wall leaks. While rare, a penetrating impact can cause a leak path without obvious external damage.

- Acoustic emission (optional): Some advanced service facilities do AE testing at 1.1× working pressure. If the pattern of AE events matches that of a known good cylinder, it passes. Unusual bursts of AE energy could indicate evolving damage inside, prompting further evaluation.

3.4. Comparison with Hydrogen Storage Cylinders

- Pressure Level: Hydrogen automotive tanks operate at 35 MPa or 70 MPa (350–700 bar), far above the 200–300 bar of SCBA cylinders. This means hydrogen tanks require thicker overwraps (often > 60% fiber by weight) and typically use only carbon fiber due to its high strength. SCBA cylinders at 300 bars can incorporate some glass or aramid and still meet burst requirements. The higher pressure also intensifies issues like permeation and liner stress. For instance, ISO 19881 limits hydrogen permeation to 46 NmL/h/L at 1.15 × NWP, whereas for SCBA (air) there is no equivalent permeation safety issue—a slight air leak is not dangerous, though it affects capacity [43]. Thus, hydrogen Type IV designs reflect a focus on permeation barriers, often favoring polyamide liners with <0.05 cm3·mm/m2·day hydrogen permeability [55]. Firefighting cylinders, conversely, may use HDPE which permeates more, but as the gas is air or CO2 and the pressures lower, it is acceptable (standards typically allow a small pressure-drop over time for extinguishers) [15].

- Cycle Life vs. Shelf Life: A fuel tank in a vehicle sees daily pressure cycles (fill and empty) and hundreds of cycles per year, whereas an SCBA cylinder sees fewer full cycles—maybe one per use/training, so on the order of dozens per year—and an extinguisher sees almost none (it is rarely discharged, ideally never) [14]. This means hydrogen tanks are more prone to cyclic fatigue and require design features to handle pressure swings (like fiber prestressing via autofrettage to reduce stress ranges) [2]. Fire cylinders are more concerned with long shelf life—holding pressure for years. Hence, the focus for extinguishers is on preventing slow leaks and corrosion, which Type IV excels at. On the other hand, hydrogen tanks undergo thousands of cycles and are usually end-of-life after 15–20 years, regardless of condition (hydrogen standards often mandate retirement at 15 years) [43,44,45]. SCBA cylinders have historically had a 15-year life as well, but, as noted, some Type IV designs now advertise NLL [5].

- Environmental Extremes: Hydrogen tanks in vehicles may see wider temperature swings (−40 °C park overnight to +85 °C under hood, plus sun heating), and they must survive crash scenarios (gunfire, etc.) [43,44,45]. Fire equipment cylinders see rough handling but not quite the same sustained extremes. One extreme specific to firefighting is flame contact: a hydrogen tank is somewhat protected in a vehicle, whereas an SCBA on a firefighter’s back might be briefly exposed to flames. Both have PRDs to handle such a scenario. Interestingly, the bonfire test for SCBA (e.g., NFPA standards) is often undertaken with the cylinder as part of the SCBA pack, requiring the cylinder to vent safely without rupturing while the pack is engulfed for a short period—very similar to the ISO vehicle tank bonfire test [1,45]. So, in terms of fire behavior, the two applications converge. Conversely, embrittlement is a concern of hydrogen tanks (metallic bosses can suffer hydrogen embrittlement, though Type IV liners avoid that issue) and fuel quality (no polymerization or contamination of hydrogen).

- Design Margin and Inspection Philosophy: Hydrogen tanks are typically designed with minimal margin (to save weight) but then tested intensively (every batch is burst tested for certification) [45]. They do not get routine in-use re-testing beyond visual inspection and maybe leak checks in vehicles [8]. In contrast, SCBA cylinders are often slightly overbuilt (weight is important, but safety factors might be a bit higher than absolute minimum) and then they are regularly tested (every 5 years) [16]. This difference in approach means a composite SCBA cylinder might actually have a higher reliability over time because any that start to degrade will be caught and removed. In effect, fire service cylinders are maintained more like life-critical gear, with frequent inspection, whereas hydrogen tanks are treated more like automotive components with fixed lifespan.

- Boss and Sealing Design: Both use metal bosses for the valve interface, but hydrogen bosses have to seal against hydrogen (small molecule) and often incorporate high-pressure internal valves, etc. SCBA bosses are simpler (basically a neck thread for the valve) [43,53]. However, lessons from hydrogen have led to improved boss designs for SCBA too—e.g., using conical sealing surfaces and O-rings that account for the liner’s viscoelasticity. A recent polymer science study (Zha et al. 2025) modeled the sealing at the boss of Type IV hydrogen vessels and found that liner thickness and creep can significantly affect leak tightness [53]. That insight is equally applicable to an air cylinder: ensuring the boss–liner interface has an annular groove or feature to concentrate seal pressure can prevent slow leaks over years. Indeed, the P50 extinguisher uses a patented locking neck ring to keep the boss tightly attached to the liner [9].

4. Market Potential and Key Players

4.1. SCBA Cylinders on the Market

4.2. Portable Extinguishers on the Market

4.3. Market Potential

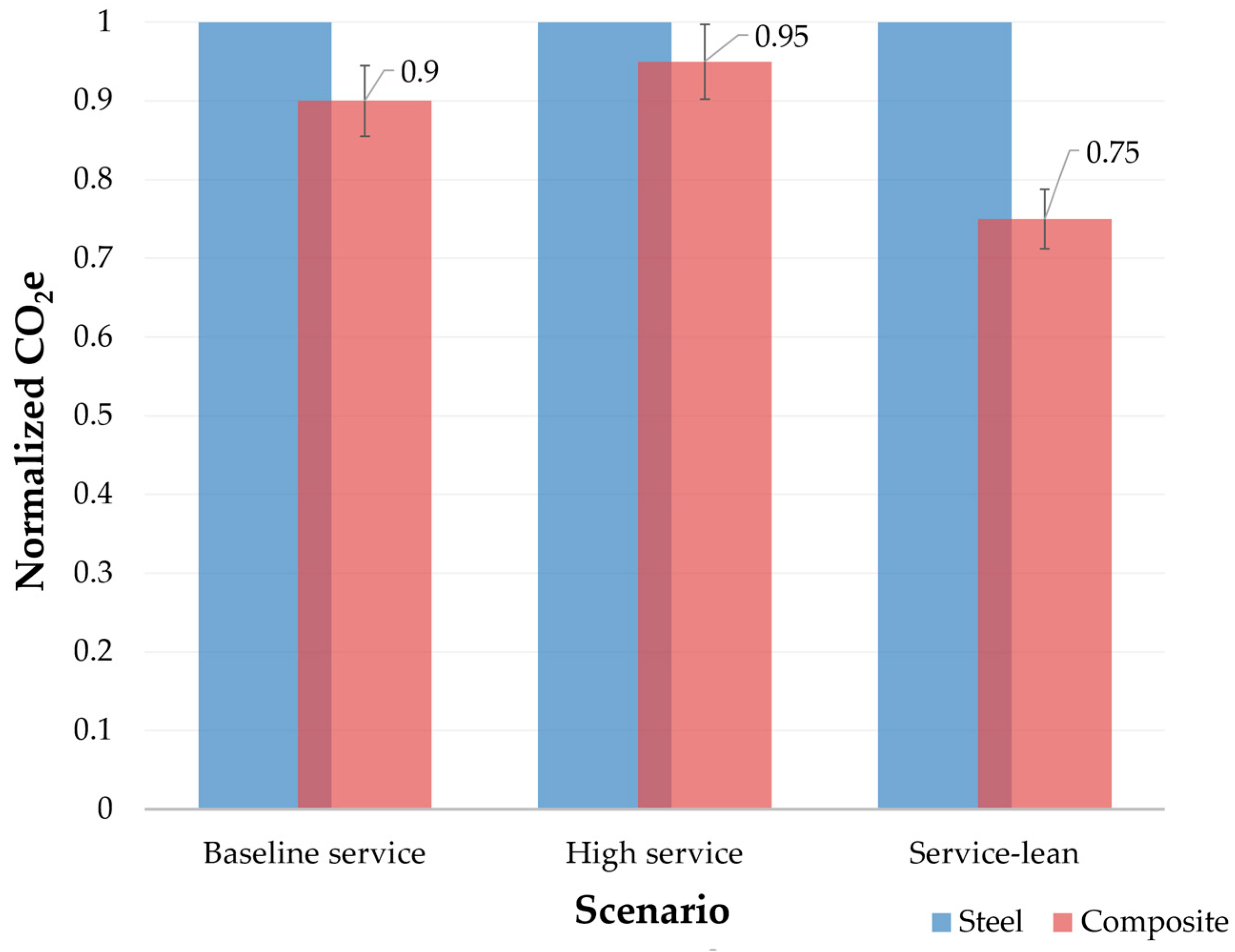

4.4. Environmental and End-of-Life Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COPV | Composite overwrapped pressure vessel |

| SCBA | Self-contained breathing apparatus |

| PED | Pressure Equipment Directive (EU 2014/68/EU) |

| TPED | Transportable Pressure Equipment Directive (EU 2010/35/EU) |

| NFPA | National Fire Protection Association |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| DOT | U.S. Department of Transportation |

| CGA | Compressed Gas Association |

| UL | Underwriters laboratory |

| PRD | Pressure relief device |

| NDT | Non-destructive testing |

| AE | Acoustic emission |

| SHM | Structural health monitoring |

| FO | Fiberoptic (sensing) |

| RTM | Resin transfer molding |

| VARTM | Vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding |

| OOA | Out of autoclave (processing) |

| EVOH | Ethylene–vinyl alcohol (barrier layer) |

| FR | Flame retardant |

| NLL | Non-limited life (service life) |

| STP | Standard temperature and pressure |

| scc/h | Standard cubic centimeter per hour |

References

- Burks, B.; Ziola, S.; Gorman, M. Environmental Exposure Effects on DOT-CFFC Cylinders with Modal Acoustic Emission Examination; Acoustic Emission Examination: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Magliano, A.; Perez Carrera, C.; Pappalardo, C.M.; Guida, D.; Berardi, V.P. A Comprehensive Literature Review on Hydrogen Tanks: Storage, Safety, and Structural Integrity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dräger Dräger Compressed Air Breathing Cylinders Accessories for Breathing Apparatus. Available online: https://www.draeger.com/en-us_us/Products/Compressed-Air-Breathing-Cylinders (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- MSA Safety Inc. G1 SCBA Cylinders. Available online: https://us.msasafety.com/Supplied-Air-Respirators-%28SCBA%29/Cylinders/G1-SCBA-Cylinders/p/000010000800002001?locale=en (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Luxfer Composite Inspection Manual. 2021. Available online: https://www.luxfercylinders.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Luxfer_SCBA_Carbon_Composite_PED-TPED_A4_2024.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hoey, I. Saving Made Simple: How Composite Extinguishers Are Replacing Metal Worldwide with Britannia Fire. 2025. Available online: https://internationalfireandsafetyjournal.com/saving-made-simple-how-composite-extinguishers-are-replacing-metal-worldwide-with-britannia-fire/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- NFPA 1981:2019; Standard on Open-Circuit Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) for Emergency Services. NFPA: Quincy, MA, USA, 2019.

- EN 12245:2022; Transportable Gas Cylinders—Fully Wrapped Composite Cylinders 2022. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- BRITANNIA FIRE The P50 Range in Safe Hands. Available online: https://www.britannia-fire.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/P50-Brochure-2023-1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Li, X.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, B.; Li, J. Review of the Hydrogen Permeation Test of the Polymer Liner Material of Type IV On-Board Hydrogen Storage Cylinders. Materials 2023, 16, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ding, G.; Feng, P.; Wu, C. High-Pressure Hydrogen Effects on Thermoplastics: A Comprehensive Review of Permeation, Decompression Failure, and Mechanical Properties. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2025, 8, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11119-3:2013; Gas Cylinders—Refillable Composite Gas Cylinders—Design, Construction and Testing—Part 3: Fully Wrapped Fibre Reinforced Composite Cylinders with Non-Load-Sharing Metallic or Non-Metallic Liners 2013. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). NFPA 10 Standard for Portable Fire Extinguishers 2026; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kis, D.I.; Kókai, E. A Review on the Factors of Liner Collapse in Type IV Hydrogen Storage Vessels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 50, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinella, A.; Capurso, G.; Zanocco, M.; Basso, F.; Calligaro, C.; Menotti, D.; Agnoletti, A.; Fedrizzi, L. Study of the Failure Mechanism of a High-Density Polyethylene Liner in a Type IV High-Pressure Storage Tank. Polymers 2024, 16, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CGA C-6.2-2019; Standard for Visual Inspection and Requalification of Fiber Reinforced High Pressure Cylinders 2019. Compressed Gas Association: Chantilly, VA, USA, 2019.

- Li, Y.; Barzagli, F.; Liu, P.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Huang, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, C.; Luo, H.; et al. Mechanism and Evaluation of Hydrogen Permeation Barriers: A Critical Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 15752–15773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zou, Y.; Xia, Q.; Cao, L.; Zhang, M.; Shen, T.; Du, J. Simulation Analysis and Optimization Design of Dome Structure in Filament Wound Composite Shells. Polymers 2025, 17, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, D.I.; Hansághy, P.; Bata, A.; Nemestóthy, N.; Gerse, P.; Tajti, F.; Kókai, E. Gas Barrier Properties of Organoclay-Reinforced Polyamide 6 Nanocomposite Liners for Type IV Hydrogen Storage Vessels. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yersak, T.A.; Baker, D.R.; Yanagisawa, Y.; Slavik, S.; Immel, R.; Mack-Gardner, A.; Herrmann, M.; Cai, M. Predictive Model for Depressurization-Induced Blistering of Type IV Tank Liners for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 28910–28917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habel, C.; Tsurko, E.S.; Timmins, R.L.; Hutschreuther, J.; Kunz, R.; Schuchardt, D.D.; Rosenfeldt, S.; Altstädt, V.; Breu, J. Lightweight Ultra-High-Barrier Liners for Helium and Hydrogen. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7018–7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Han, H.S.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, J.; Seong, D.G. EPDM Rubber-Reinforced PA6/EVOH Composite with Enhanced Gas Barrier Properties and Injection Moldability for Hydrogen Tank Liner. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 2327–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.; Runka, J. Multilayer Liner for a High-Pressure Gas Cylinder 2014. Available online: https://patentscope2.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2012129701 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Tariq, M.; Nisar, S.; Shah, A.; Akbar, S.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, S.Z. Effect of Hybrid Reinforcement on the Performance of Filament Wound Hollow Shaft. Compos. Struct 2018, 184, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrinho, L.L.; Calado, V.M.A.; Bastian, F.L. Effects of Rubber Addition to an Epoxy Resin and Its Fiber Glass—Reinforced Composite. Polym. Compos. 2012, 33, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varley, R.J. Toughening of Epoxy Resin Systems Using Low—viscosity Additives. Polym. Int. 2004, 53, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Peng, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, P. Recent Developments in the Flame-Retardant System of Epoxy Resin. Materials 2020, 13, 2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Song, L.; Xing, W.; Lu, H.; Lv, P.; Jie, G. Flame Retardancy and Thermal Degradation Mechanism of Epoxy Resin Composites Based on a DOPO Substituted Organophosphorus Oligomer. Polymer 2010, 51, 2435–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alms, J.; Sambale, A.K.; Fuchs, J.; Lorenz, N.; von den Berg, N.; Conen, T.; Çelik, H.; Dahlmann, R.; Hopmann, C.; Stommel, M. Qualification of the Vitrimeric Matrices in Industrial-Scale Wet Filament Winding Processes for Type-4 Pressure Vessels. Polymers 2025, 17, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Fring, L.D.; Pallaka, M.R.; Simmons, K.L. A Review of the Fabrication Methods and Mechanical Behavior of Continuous Thermoplastic Polymer Fiber–Thermoplastic Polymer Matrix Composites. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 694–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hien, D.; Ngoc Thanh, T.; Tung Lam, V.; Thi Thanh Van, T.; Van Hao, L. Design of Planar Wound Composite Vessel Based on Preventing Slippage Tendency of Fibers. Compos. Struct 2020, 254, 112854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eryilmaz, O.; Oz, M.E.; Jois, K.C.; Sackmann, J.; Gries, T. FEA and Experimental Ultimate Burst Pressure Analysis of Type IV Composite Pressure Vessels Manufactured by Robot-Assisted Radial Braiding Technique. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toray Out of Autoclave Curing of Prepreg. Available online: https://www.toraycma.com/applications/ooa-out-of-autoclave/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Mitchell, S.A. UV Curing: Cure on Demand for Filament Winding. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019. Available online: https://www.noblelight.com/media/media/hng/doc_hng/industries_and_applications_1/uv_technology_1/case_stories_1/Technical_Paper_-_UV_Curing_Cure_on_Demand_for_Filament_Winding.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ekuase, O.A.; Anjum, N.; Eze, V.O.; Okoli, O.I. A Review on the Out-of-Autoclave Process for Composite Manufacturing. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmene, F. Use of acoustic emission for inspection of composite pressure vessels subjected to mechanical impact. In Proceedings of the 33th European Working Group on Acoustic Emission, Senlis, France, 12–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Son, D.-S.; Hong, J.-H.; Chang, S.-H. Determination of the Autofrettage Pressure and Estimation of Material Failures of a Type III Hydrogen Pressure Vessel by Using Finite Element Analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 12771–12781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaznavi, A.; Kästle, E.D.; Popiela, B.; Duffner, E. Damage Monitoring of Hydrogen Composite Pressure Vessels Using Acoustic Emission Technique and Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the SCHALL 25—Schallemissionsanalyse und Zustandsüberwachung Mit Geführten Wellen, Dresden, Germany, 27–28 March 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E2191/E2191M-16; Standard Practice for Examination of Gas-Filled Filament-Wound Composite Pressure Vessels Using Acoustic Emission. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://store.astm.org/e2191_e2191m-16.html (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Rocha, H.; Antunes, P.; Lafont, U.; Nunes, J.P. Processing and Structural Health Monitoring of a Composite Overwrapped Pressure Vessel for Hydrogen Storage. Struct. Health Monit. 2024, 23, 2391–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehls, G. Shearography Equipment Well Suited to Composites NDT. 2025. Available online: https://www.compositesworld.com/products/shearography-equipment-well-suited-to-composites-ndt (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- British Standard BS EN 3-7:2004+A1:2007; Portable Fire Extinguishers Part 7: Characteristics, Performance Requirements and Test Methods. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2008.

- ISO 19881:2018; Gaseous Hydrogen—Land Vehicle Fuel Containers. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Global Technical Regulation No. 13. Global Technical Regulation on Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Vehicles 2013; UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Regulation No 134 of the Economic Commission for Europe of the United Nations (UN/ECE) Uniform Provisions Concerning the Approval of Motor Vehicles and Their Components with Regard to the Safety-Related Performance of Hydrogen-Fuelled Vehicles (HFCV); UNECE: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- UL 299. Dry Chemical Fire Extinguishers. 2025. Available online: https://www`.shopulstandards.com/ProductDetail.aspx?productId=UL299 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- UL 2129. Halocarbon Clean Agent Fire Extinguishers. 2025. Available online: https://www.shopulstandards.com/ProductDetail.aspx?productId=UL2129 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Firesafe History of Fire Extinguishers. Available online: https://www.firesafe.org.uk/history-of-fire-extinguishers/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- ISO/TR 4673:2022; Gas Cylinders—Service Life Performance of Composite Cylinders and Tubes. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kis, D.I.; Bata, A.; Takács, J.; Kókai, E. Mechanical Properties of Clay-Reinforced Polyamide 6 Nanocomposite Liner Materials of Type IV Hydrogen Storage Vessels. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miguel, N.; Mair, G.; Acosta, B.; Szczepaniak, M.; Moretto, P. Hydraulic and Pneumatic Pressure Cycle Life Test Results on Composite Reinforced Tanks for Hydrogen Storage. In Proceedings of the Volume 1A: Codes and Standards; American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, NY, USA, 17 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hasiotis, T.; Badogiannis, E.; Tsouvalis, N.G. Application of Ultrasonic C-Scan Techniques for Tracing Defects in Laminated Composite Materials. Stroj. Vestn. J. Mech. Eng. 2011, 2011, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Xie, P.; Yang, W. Optimizing Sealing Structure Design for Enhanced Sealing Performance in Type IV Hydrogen Storage Vessels. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e57050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankle, R.S. Investigation of the Failure of an SCBA Cylinder; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 1996.

- Sun, Y.; Lv, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, C. Research on Hydrogen Permeability of Polyamide 6 as the Liner Material for Type Ⅳ Hydrogen Storage Tank. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 24980–24990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, P.; Bengaouer, A.; Cariteau, B.; Molkov, V.; Venetsanos, A.G. Allowable Hydrogen Permeation Rate from Road Vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2742–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAFER SAFER® 9.0L NANO., Product Information. Available online: https://www.safercylinders.com/products/9-0l-nano-11n (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- DAASNAV the Composite Fire. Product Information. Available online: https://daasnav.com/foam-type-fire-extinguisher/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- ASKA ASKA MFCF 10 MAINTENANCE FREE, Corrosion Free Fire Extinguishers. 2025. Available online: https://askagroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/ASKA-fire-pdf.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Raksha Sharma, D. Composite SCBA Cylinders Market. 2025. Available online: https://dataintelo.com/report/global-carbon-composite-scba-cylinders-market (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus Market Size, Share, Growth, and Industry Analysis, By Type (Open-Circuit SCBA, Closed-Circuit SCBA), By Application (Fire Fighting, Industrial Use, Other Use), Regional Insights and Forecast to 2034; Market Growth Reports; Grand View Research: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2025.

- Zion Market Research Global Fire Extinguishers Market Size, Share, Growth Analysis Report—Forecast 2034; Zion Market Research: New York City, NY, USA, 2025.

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

| Matrix | Tg/Tm | Toughness (qual.) | Weld/Repair | FR Options | Process Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy (toughened) | Tg 90–130 °C | Medium | No | P-based, nano-fillers | Mature OOA; good stiffness |

| Vitrimer (epoxy-like) | Tg 80–120 °C; exchange 120–180 °C | Medium–high | Yes (bond exchange) | P-based/nano | Repairable; Tg margin vs. refill thermals |

| Thermoplastic (PA12/PPS/PEEK) | Tm 175/285/343 °C | High | Yes (fusion) | Halogen-free FR, nano | Heat-input must protect liner |

| Liner | Softening Window | Barrier | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE | ~80–110 °C (softening)/melt ≈130 °C | Fair | Easy processing; higher permeation; good impact |

| PA6/PA12 | ~120–160 °C (HDT band) | Good | Better adhesion; better high-T retention |

| PET | ~70–90 °C (HDT)/Tg ~75 °C | Good–very good | Stiffer; good barrier; process temp higher |

| EVOH barrier (layer) | — | Excellent | Multilayer liners; strong permeation cut |

| Nano-barrier (GNP/MMT) | — | Good | Tortuous path; raises modulus locally |

| Liner Material | Notable Properties | H2 Permeability | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HDPE (PE 100) | Semi-crystalline polyolefin | High (baseline) | Tough, impact-resistant; inexpensive; no moisture absorption. | High gas permeability; significant thermal expansion. |

| PA6/PA66 (nylon) | Semi-crystalline polyamide | ~5× lower than HDPE | Low gas permeability; high strength; tolerates −40 °C. | Absorbs moisture (plasticization); more costly; needs impact modifiers. |

| EVOH (copolymer) | Amorphous ethylene–vinyl alcohol | ~100× lower than HDPE | Extremely low permeability (to H2, O2); good adhesion to polyamides. | Brittle, especially when moist; cannot be used alone as structural liner. |

| PET (polyester) | Semi-crystalline thermoplastic | Low (similar to PA) | Good barrier (esp. CO2); high stiffness; low creep; no corrosion. | Higher processing temperature; less ductile than HDPE. |

| PA–nanocomposite | PA matrix + clay or graphene filler | 2–4× lower than neat PA | Greatly reduced permeation if well dispersed; can improve mechanical properties. | Filler dispersion challenges; potential voids; higher viscosity complicates molding. |

| Parameter | Typical Range | Rationale/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hoop angle | 85–90° | Membrane (hoop) stress capacity |

| Helical angles | ±15–30° | Axial load share; dome stability |

| Tow tension (carbon) | 20–60 N per tow | Compaction vs. slippage control |

| Winding speed | 0.3–1.0 m·s−1 | Path accuracy vs. resin flow |

| Overwrap thickness (belt) | ~2.5–4.0 mm | Size and MAWP dependent |

| Shell mass (6.8 L/300 bar) | 2.5–2.8 kg | Type IV; −20 … −40% vs. Type III |

| Cure route | OOA epoxy/vitrimer; post-cure 80–120 °C | Tg margin to refill thermals |

| Process monitoring | AE/FBG during autofrettage | Early damage screening |

| Standard/Code | Region | Applicable Equipment | Key Provisions for Type IV COPVs |

|---|---|---|---|

| EN 12245:2022 | EU | Transportable gas cylinders (general, including SCBA) | Design and prototype tests for fully wrapped composite cylinders. Requires batch tests, bonfire test with PRD activation, drop tests from 1.2 m (vertical) and 3.3 m (angled) without burst. Fifteen-year design life unless otherwise justified. |

| BS EN 3-7:2004 (+EN 3-8) | EU | Portable fire extinguishers | Construction and testing of extinguisher bodies. Implicitly expects metal cylinders but composite can comply via equivalent testing. Requires 35 bar minimum test pressure for stored-pressure extinguishers, corrosion resistance, and impact resistance (e.g., falling from mounting bracket). |

| ISO 11119-3:2013 | International | Fully wrapped composite cylinders with non-metallic liner | Global design standard mirrored in UN Model Regulations. Similar tests to EN 12245 plus environmental conditioning (thermal cycling, humidity) and more detailed liner permeation requirements. |

| ISO 19881:2018 | International | On-board hydrogen tanks (70 MPa Type IV) | Very stringent testing: permeation limit of 46 Nml/h/L at 1.15 × NWP 55 °C, hydraulic sequential tests (drop, vibration, pendulum impact before burst), gunfire test, etc. Demonstrates extreme safety margin (burst > 2.25× NWP). Relevant to SCBA by analogy (similar stress rupture requirements. |

| DOT-SP (Special Permits) | USA | SCBA composite cylinders, others | DOT permits like SP 10915, SP 14232 allow the use of Type IV cylinders for SCBA with specific conditions (e.g., 30-year life, certain fiber and resin). They mandate refill cycle limits and visual inspections per CGA C-6.2 (guidelines for composite cylinder inspection). |

| NFPA 1981 (2019) | USA | SCBA (overall system) | Requires SCBA cylinders meet DOT and CGA standards. Mandates SCBA function tests (e.g., drop tests of the pack, flame impingement test for the whole SCBA). If a composite cylinder is used, it must remain intact and not cause pack failure in these tests. |

| Marine Equipment Directive (MED) | EU | Marine-use fire equipment (including extinguishers) | MED approval for composite extinguishers (e.g., Britannia P50) required showing compliance with EN 3 and additional corrosion and vibration tests for ship environments. Composite design benefits (no corrosion) actually help in salt-spray tests. |

| Item | Steel | Composite | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAPEX/unit (year 0) | 150 | 240 | EUR, example |

| Annual service visit | 50/y | 20/y | Contractor vs. in-house |

| Hydrotest/periodic | 30/y | 10/y | Local code dependent |

| Corrosion remediation | 15/y | 0 | Repaint/grit-blast |

| Residual value (y10) | 10 | 30 | Liner reuse/fiber recovery |

| PV total (10 y) | ~670 | ~490 | Composite −27% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kun, K.; Kis, D.I.; Zhang, C. Type IV High-Pressure Composite Pressure Vessels for Fire Fighting Equipment: A Comprehensive Review and Market Assessment. Fire 2025, 8, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120465

Kun K, Kis DI, Zhang C. Type IV High-Pressure Composite Pressure Vessels for Fire Fighting Equipment: A Comprehensive Review and Market Assessment. Fire. 2025; 8(12):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120465

Chicago/Turabian StyleKun, Krisztián, Dávid István Kis, and Caizhi Zhang. 2025. "Type IV High-Pressure Composite Pressure Vessels for Fire Fighting Equipment: A Comprehensive Review and Market Assessment" Fire 8, no. 12: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120465

APA StyleKun, K., Kis, D. I., & Zhang, C. (2025). Type IV High-Pressure Composite Pressure Vessels for Fire Fighting Equipment: A Comprehensive Review and Market Assessment. Fire, 8(12), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire8120465