1. Introduction

The diversified development of the socioeconomy has led to a steady increase in the number of small business premises. While these establishments inject vitality into urban growth, they also introduce numerous safety concerns [

1,

2,

3]. On 21 June 2023, a severe liquefied petroleum gas leak triggered a major explosion at a barbecue restaurant in Fuyang, Yinchuan, Ningxia, resulting in 31 fatalities and 7 injuries. Shortly afterward, on 24 January 2024, a fire broke out in a street-level shop in Xinyu, Jiangxi, caused by the unauthorized conversion of a basement in a mixed-use building into a rented cold storage facility, leading to 39 deaths and 9 injuries. Characterized by their diversity, widespread distribution, high tenant turnover, limited spatial capacity, and dense occupancy, small business premises pose significant safety challenges and have increasingly become a focus of public and academic attention [

4,

5].

Numerous scholars have conducted extensive research on safety management in typical environments, yielding substantial outcomes. Zhang Hui [

6] proposed countermeasures based on case studies of large commercial complex accidents and safety management experience, focusing on improving regulations, enhancing personnel and technical prevention, and strengthening daily management. Wang Wei [

7] investigated fire safety management in high-rise buildings, identifying common prominent issues and elucidating their causes. Wang Xuanwen [

8] examined the current state and problems of urban safety management in Lüliang City, highlighting issues such as inadequate regulations, ineffective grid-based management, and weak grassroots supervision. Yang Jing [

9] studied fire safety management in specialized markets in the Wuhou District, pointing out deficiencies in the regulatory system, inherent limitations in fire prevention conditions, ineffective fire safety education and training, and insufficient fire rescue capabilities, while proposing targeted measures for improvement. Zhan Pinfang [

10] employed literature review and field surveys to study fire safety supervision in rental housing in Dongguan, revealing widespread problems such as separation of ownership and management rights and non-standard fire safety practices. Dubukumah et al. [

11] focused on fire prevention and control in market shops, designing a real-time monitoring and automatic fire suppression system integrated with remote alarm functionality using temperature, gas, and smoke sensors. Hassanain et al. [

12] explored risk assessment methods for workplace fire safety through case studies, emphasizing the importance of raising fire safety awareness and standardizing management systems. Ali et al. [

13] addressed the applicability of fire protection standards in the conversion of hotel buildings in Malaysia, discussing how existing structures can comply with current codes. Kanyesigye [

14] assessed the fire safety preparedness of retail businesses in Kampala, Uganda, evaluating employees’ capabilities in identifying and eliminating fire hazards, extinguishing initial fires, organizing evacuations, and conducting fire safety training. Huo et al. [

15] conducted full-scale burning experiments to investigate smoke dispersion patterns in atrium spaces due to shop fires, proposing a plume model suitable for fires in shops with limited width. Zalok et al. [

16] systematically analyzed the fire load density distribution characteristics across various types of commercial premises based on a survey of 168 establishments, examining its relationship with floor area. Rabiei et al. [

17] applied the FRAME methodology to assess fire risk in commercial and shopping centers, identifying insufficient ventilation systems, lack of emergency exits, and absence of automatic fire alarm systems as major risk factors. Gairson [

18] demonstrated through field investigations the positive impact of annual fire prevention inspections on reducing the incidence of fires in commercial occupancies. Yao H.W. et al. [

19,

20,

21] conducted a study on small business premises located within underground commercial streets. In summary, existing research has primarily concentrated on key fire safety units and high-risk premises, often relying on relatively small sample sizes.

This study focuses on small restaurants, supermarkets, convenience stores, and hotels as research subjects. Through field investigations conducted in an urban area, it identifies and analyzes prominent issues in current safety management practices. The findings aim to provide evidence-based support for relevant government departments in the formulation of policy documents.

2. Survey Content and Results Analysis

This study adopted a comprehensive survey approach, conducting a census of all small business premises within the urban area to ensure data completeness and accuracy. The investigation covered all administrative streets in the urban area, including small restaurants, supermarkets, and hotels. The total initial survey sample consisted of 2375 small restaurants, 239 supermarkets, and 236 small hotels. Due to closures, business transfers, or refusal to participate, the final valid samples obtained were 1822 restaurants, 203 supermarkets, and 187 hotels. Data collection was carried out using a structured on-site checklist combined with field observations and recordings. All investigators received standardized training to ensure consistency in evaluation criteria. The checklist covered key indicators including: administrative permits and qualifications, safety officers and training records, firefighting facilities and emergency equipment, electrical and gas safety, evacuation routes and signage systems, emergency plans and drill records, among others. All data were entered into electronic spreadsheets on-site and subjected to a dual-verification mechanism by two personnel to ensure accuracy. Sensitive information (such as business license numbers and names of responsible persons) was recorded with verbal consent and anonymized.

2.1. Small Restaurants

The survey primarily encompassed the following areas: administrative permits, safety production responsible personnel, gas safety inspections, emergency evacuation plans and drills, safety evacuation protocols, equipment and facilities, electrical safety, and gas safety compliance.

Regarding administrative licensing, 11.53% (n = 210) of the surveyed catering venues were found to operate with either missing or expired business licenses, while 19.32% (n = 352) lacked valid or current food operation permits. With respect to safety production responsibilities, most managers at these venues concurrently held the roles of safety administrators or fire safety officers. Although these individuals had attended gas safety training sessions organized by district- or street-level authorities, the effectiveness of such training was limited due to its short duration, lack of systematic content, and poor knowledge retention among participants. Accordingly, safety responsibility systems in these establishments continue to be poorly implemented and need improvement. In the area of gas safety inspections, in response to the analysis of multiple gas explosion incidents in recent years, natural gas supply companies have implemented regular on-site inspections of user premises, gas facilities, and equipment. In contrast, emergency preparedness was severely lacking: over 90% of the catering establishments had not developed emergency response plans, conducted evacuation drills, or maintained relevant documentation.

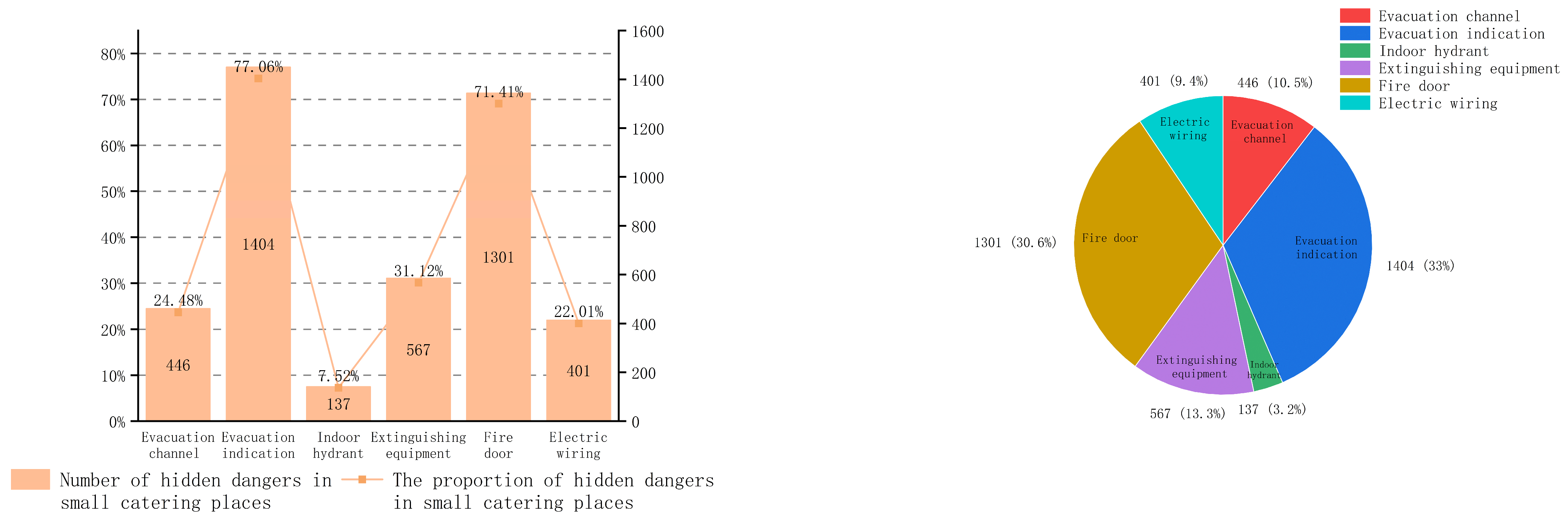

The inspection identified critical deficiencies in emergency evacuation preparedness across multiple dimensions. Key findings include: (1) obstructed emergency exits or evacuation routes, observed in 24.48% (n = 446) of venues, posing immediate egress risks; (2) non-compliant evacuation signage—including missing, obstructed, or non-functional illuminated signs—in 77.06% (n = 1404) of establishments; (3) absent or defective emergency lighting systems in 76.29% (n = 1390) of venues, resulting from missing fixtures, malfunctions, or failure to install required equipment; (4) most notably, over 90% of premises lacked prominently displayed evacuation route diagrams in public areas, significantly increasing the risk of spatial disorientation during emergencies.

Significant deficiencies in fire protection infrastructure were identified across the surveyed establishments. Indoor fire hydrant systems were deficient in 7.52% (n = 137) of venues, exhibiting issues such as non-functional water supply, incomplete assemblies, obscured identification, or access obstructions. Fire extinguisher violations were observed in 31.12% (n = 567) of establishments, including insufficient quantities, expired or depressurized units, and lack of mandatory inspections. The most prevalent issue—identified in 71.41% (n = 1301) of venues—was the absence of adequate fire-rated separation between kitchen and customer areas. Additional hazards included non-compliant smoke exhaust system installations and the use of flammable decorative materials in dining spaces.

In terms of electrical safety, 22.01% (n = 401) of the catering establishments were found to have non-compliant electrical wiring installations, including unauthorized circuit extensions, improperly installed wiring, and a lack of fire-rated conduit protection. Additionally, 14.82% (n = 270) exhibited distribution board violations, such as missing covers on electrical panels or non-functional residual current devices (RCDs). Other observed hazards included electrical switches and sockets mounted on combustible materials, as well as daisy-chained power strips.

Gas safety violations contributed significantly to operational hazards. Specifically, twenty-four establishments (1.32%) were found to have either failed to install gas leak detectors, or possessed malfunctioning or improperly positioned devices. Among liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) users, frequent non-compliances involved the use of non-compliant hose types, faulty installations, and hazardous configurations—including hoses exceeding 2 m in length or passing through walls, ceilings, or floors. Such configurations not only breach safety regulations but also pose serious risks by creating potential leak pathways and ignition sources within occupied areas.

In summary, the prominent safety risks in small-scale food service establishments are characterized by: malfunctioning or missing emergency lighting and evacuation signage; faulty or absent fire-rated doors; indoor fire hydrants with insufficient water supply, missing components, or obstruction by debris; blocked or locked evacuation routes; and non-compliant electrical wiring installations (see

Figure 1). It is therefore recommended that administrative regulators implement targeted interventions to address these critical hazards and enhance overall fire safety protocols in such operations.

2.2. Small Supermarkets and Convenience Stores

Owing to their independent operational nature and spatial constraints, this survey of small supermarkets and convenience stores focused on fire compartmentation, safe evacuation, equipment and facilities, and electrical safety.

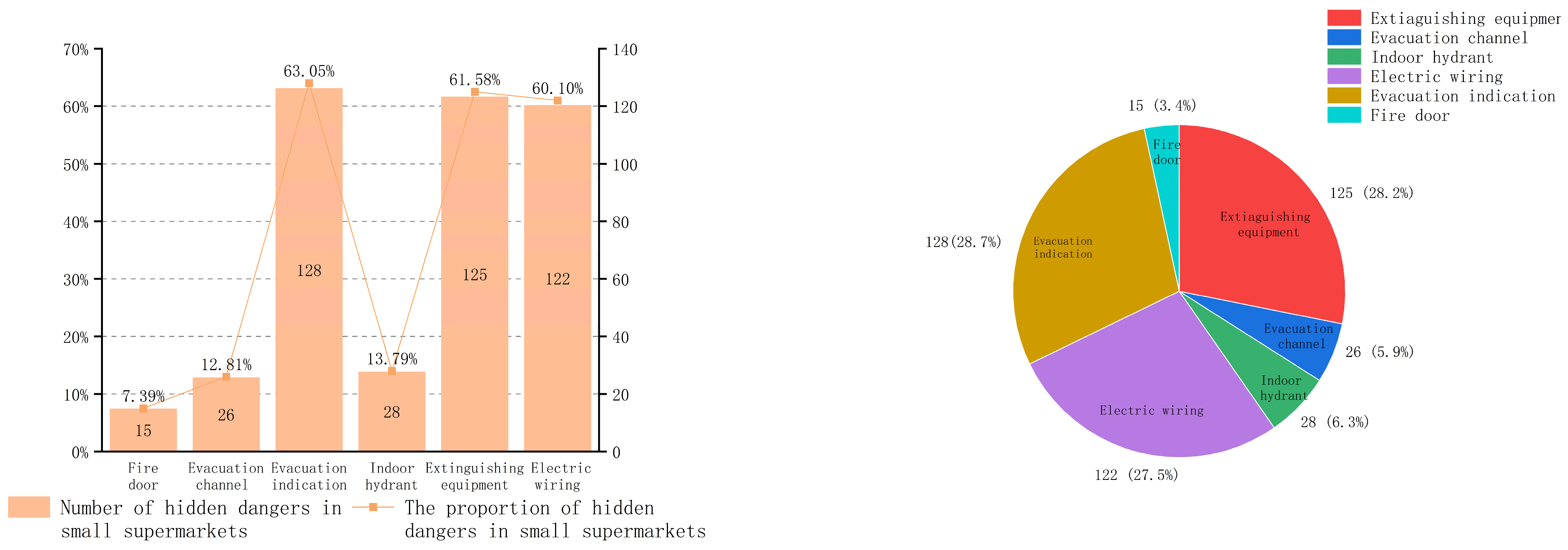

Inspection of fire compartmentation measures revealed significant deficiencies in both material selection and installation. Specifically, 7.39% (n = 15) of establishments used non-compliant fire-rated sealing materials—such as non-fire-rated expanding foam—and exhibited unsealed penetrations through wall assemblies. These deficiencies compromise the structural fire integrity between operational and adjacent areas.

The assessment revealed significant non-compliances in evacuation safety. Specifically, 12.81% (n = 26) of the establishments were found to have locked emergency exits or evacuation routes obstructed by stored items. A more widespread issue involved illuminated evacuation signage: 63.05% (n = 128) of venues exhibited missing, obstructed, or non-functional signage, failing to comply with regulatory requirements. Furthermore, 59.11% (n = 120) lacked properly installed or functional emergency lighting systems. Additional deficiencies included incorrectly oriented evacuation signs and missing safety markings at exit points, further increasing occupants’ disorientation risks during emergencies.

Regarding fire protection infrastructure, the limited scale of these establishments typically precludes the installation of automatic fire alarm systems, with most relying exclusively on indoor fire hydrants and portable fire extinguishers. The survey identified several critical deficiencies in these installations. Among the inspected sites, 13.79% (n = 28) exhibited issues with indoor fire hydrants, including absent water supply, incomplete assemblies, obstructed access, blocked identification labels, or materials stored in front of the hydrants. Furthermore, 61.58% (n = 125) of establishments showed non-compliances related to fire extinguishers, such as missing units, expired or under-pressurized equipment, and poorly visible or inaccessible placement.

In terms of electrical safety, 60.10% (n = 122) of the establishments were identified with non-compliant electrical wiring installations, including unauthorized circuit modifications, non-standard wiring practices, and a lack of non-combustible conduit protection. Additionally, 32.51% (n = 66) exhibited improperly configured electrical distribution boards, while 25.12% (n = 51) were found using daisy-chained power strips. Furthermore, 13.79% (n = 28) had electrical switches or sockets mounted on combustible materials. Regarding gas safety, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) was used in some venues without safety shut-off valves or functional gas leak detection alarms.

To conclude, the prominent risks identified in small supermarkets and convenience stores primarily include: missing or non-functional emergency lighting and evacuation signage; absent, under-pressurized, or inconspicuously placed fire extinguishers; and non-compliant electrical wiring installations. Each of these safety deficiencies was identified in over 60% of the surveyed establishments, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.3. Small Hotels and Inns

This study investigated several critical safety aspects, including building fire prevention, safety management, and fire protection facilities.

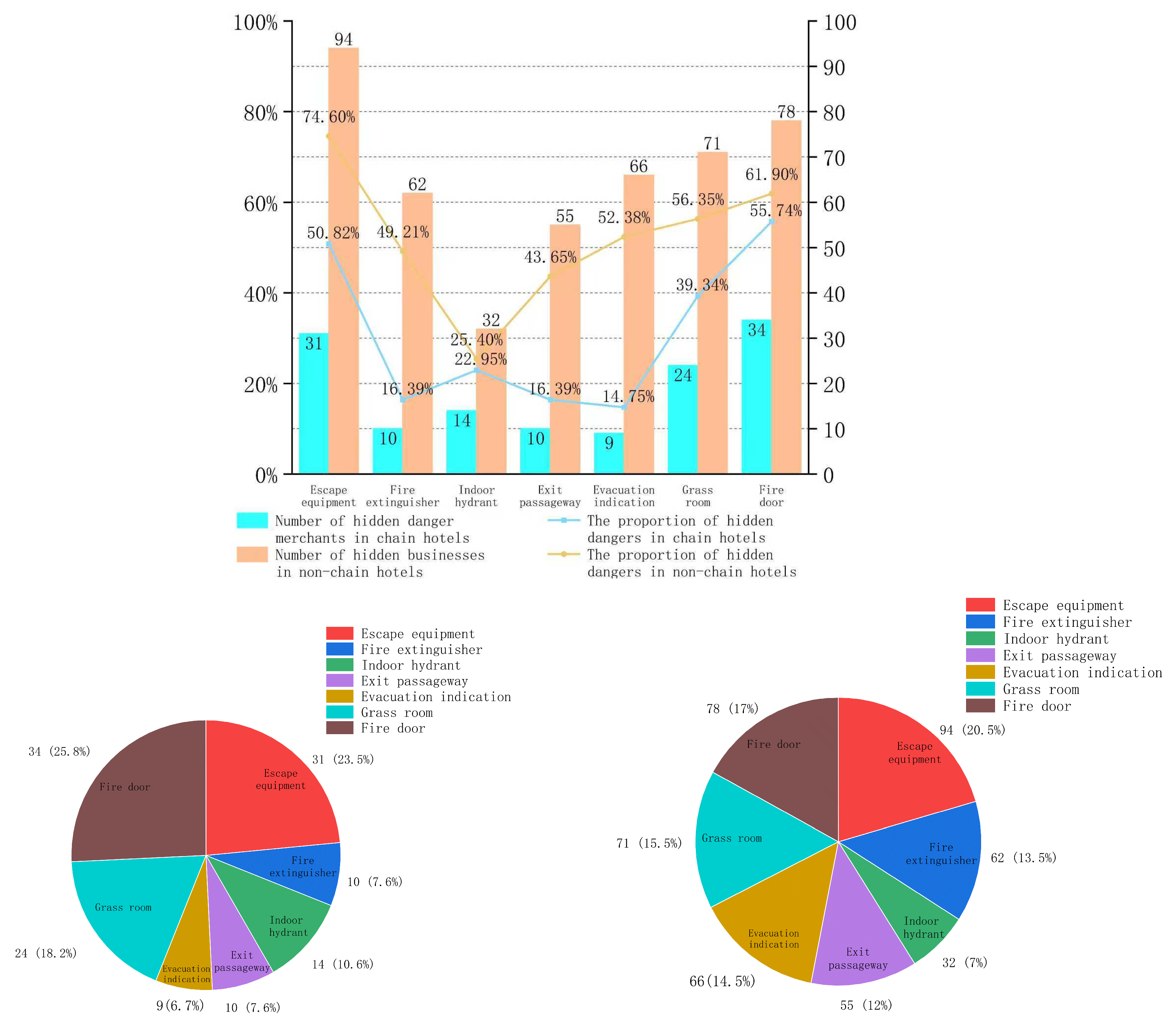

In terms of building fire protection, the assessment revealed significant deficiencies in fire compartmentation: 50.80% (n = 95) of establishments failed to install fire-rated doors for linen storage rooms; 59.89% (n = 112) exhibited non-compliant fire doors, including missing doors, unfilled door cores, absent certification labels, and faulty or missing door closers or sequential closing devices; 18.72% (n = 35) had inadequate fire sealing measures in electrical distribution rooms, cable shafts, pipeline penetrations, or cable trays; 19.79% (n = 37) utilized shared spaces among front desks, linen storage, fire control rooms, or warehouses without implementing appropriate fire separation measures; Additionally, some venues lacked compliant fire-rated separation between open-flame cooking areas and public dining zones.

The survey also identified serious deficiencies in safety management practices. Specifically, 34.76% (n = 65) of establishments had emergency exits or evacuation routes obstructed by stored items, impairing safe egress during emergencies. Additionally, 21.39% (n = 40) failed to display evacuation diagrams in guest rooms, limiting occupants’ awareness of exit routes. Furthermore, 7.49% (n = 14) had not developed emergency evacuation plans, conducted drills, or maintained relevant documentation. Compounding these issues, most fire control room operators lacked nationally certified qualifications for fire safety equipment operation, raising concerns regarding their capacity to respond effectively in crisis situations. The absence of these essential measures significantly undermines emergency preparedness and increases operational risks.

The assessment revealed critical deficiencies in fire protection infrastructure across the surveyed establishments. Key issues include: 66.84% (n = 125) of sites either lacked self-contained breathing apparatuses, emergency flashlights, and other escape equipment in guest rooms, or stored expired apparatuses in centralized locations; 38.50% (n = 72) exhibited non-compliant fire extinguisher installations, including insufficient quantities, overdue inspections, under-pressurized units, damaged cabinet doors, or poorly identifiable placement; 40.11% (n = 75) had missing, non-functional, or unpowered illuminated evacuation signs; 12.83% (n = 24) failed to install or maintain functional emergency lighting systems; 24.60% (n = 46) showed impaired indoor fire hydrants due to absent water supply, low pressure, severe corrosion, incomplete components, obstructed access, or blocked identification signs. Some establishments entirely lacked required hydrant systems. These deficiencies collectively undermine early fire response capabilities and safe egress during emergencies.

Additionally, although automatic fire alarm and sprinkler systems were installed in some establishments, they were frequently found to be non-operational or poorly maintained. Common deficiencies included dry or low-pressure water supply networks, insufficient coverage of fire detectors and sprinkler heads, unacknowledged alarm or fault signals on control panels, malfunctioning fire pump control cabinets, and systems set to manual rather than automatic mode. These failures significantly compromise the functionality of the fire suppression and alarm systems, thereby increasing the potential for uncontrolled fire spread during emergencies.

The survey identified a significant disparity in safety risk distribution between chain hotels and small, independently operated non-chain hotels. Among the 61 chain hotels inspected, a total of 224 hazards were recorded, averaging 3.67 hazards per establishment. In contrast, the 126 non-chain hotels exhibited markedly higher risk levels, with 944 hazards identified—averaging 7.49 per establishment. A comparative analysis of representative hazards is presented in

Figure 3.

3. Enhancing Safety in Small Business Premises: Countermeasures and Recommendations

3.1. Establishing a Grid-Based and Community Co-Management Mechanism for Fire Safety Supervision

First, clarify the overarching principle of coordination at the district/county level and implementation by sub-district/township administrations. Define the responsibilities of the four key stakeholders [

22]—local governments, industry departments, fire and rescue agencies, and business operators—and develop separate duty lists for fire supervision to be incorporated into government performance evaluations for high-quality development.

Second, establish a grid-based fire supervision mechanism underpinned by granular urban management grids. Adopt a zoned, fixed-point, and responsibility-contract approach to assign fire safety inspections within each designated area to specific grid supervisors, ensuring rigorous implementation.

Third, expand the grassroots fire supervision workforce by setting up physical comprehensive fire supervision stations at the sub-district/township level. Utilize measures such as delegated enforcement powers at the local level and government-procured services to carry out regular hazard identification and remediation, comprehensively identifying and dynamically monitoring current fire safety risks within the jurisdiction.

3.2. Building a Smart Fire Prevention and Control System for Small Business Premises

First, a grid-based information management platform for fire safety should be established to develop an open and shared database of fire hazards. This platform would enhance data sharing within government departments and with the public, facilitate the processing of issues reported by grid personnel and grassroots delegated law enforcement officers, and enable fully digitalized and visual management. By leveraging information technologies such as the Internet of Things and big data, hazards identified during daily supervision and specialized governance by various industry departments, as well as rectification progress, can be disclosed in the database in real time. This will gradually form an information-sharing framework characterized by multi-source input, standardized management, and collective access to information [

23].

Second, efforts should be made to comprehensively implement an integrated “human-based + technology-based” prevention and control system in small business premises. This includes installing independent smoke fire detection alarms and simple sprinkler devices in business venues, as well as setting up centralized automatic fire alarm systems in streets or communities [

24]. Dedicated personnel should be arranged for 24 h duty and periodic inspections to promote the dynamic elimination of major fire safety hazards and substantially enhance the intrinsic safety level of such premises.

3.3. Sustaining Special Campaigns for Fire Safety Improvement

Given their small scale, large quantity, and high turnover of operators, small business premises remain prone to the cyclic pattern of “rectification and relapse” in safety hazards. Regulatory authorities should implement comprehensive campaigns to address issues such as inadequate fire compartmentation, obstructed evacuation routes, non-compliant electrical wiring installations, and missing or dysfunctional firefighting equipment, emergency lighting, and evacuation signage. Inspection records and rectification progress should be logged into a grid-based fire safety information management platform to establish a dynamic mechanism encompassing inspection, correction, and data sharing.

Furthermore, grassroots fire supervision teams—including delegated law enforcement officers, auxiliary supervisors, and grid personnel—should be mobilized to conduct door-to-door inspections and targeted electrical fire safety campaigns. Emphasis should be placed on small restaurants, convenience stores, and hotels to eliminate blind spots and gaps in fire safety oversight, thereby preventing and reducing the occurrence of fire incidents.

3.4. Building a Multi-Dimensional “Theory + Scenario + Practice” Fire Safety Education Model

First, multimedia technologies should be integrated to recreate fire scenarios through typical case studies and VR-based escape simulations, thereby enhancing participants’ perceptual engagement and situational awareness.

Second, develop micro-learning modules covering contextualized topics such as improper use of fire, electricity, and gas; inadequate fire compartmentation; non-compliant electrical wiring; unauthorized parking and charging of electric bicycles; and obstructed evacuation routes. This flexible format helps overcome scheduling conflicts that often prevent people from attending traditional training.

Third, effectively combine scenario-based exercises with targeted guidance by establishing an intelligent drill platform leveraging big data, IoT, and VR technologies. Using smoke generators and thermal simulators to mimic real fire conditions, and smart bracelets to monitor the correctness of escape actions in real time, trainees can systematically master standard emergency procedures—including alarm response, operation of firefighting equipment, and emergency evacuation—under professional supervision.

Fourth, strengthen specialized training for key personnel such as safety production managers, grassroots grid workers, and mini fire station teams. Develop tailored contingency response plans for different venues, shifts, and roles, and conduct regular evacuation drills to ensure operational readiness.

3.5. Limitations of the Study

It should be noted that this study has several limitations. The field survey was conducted exclusively within a specific urban area, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions with different socioeconomic conditions, regulatory frameworks, or safety cultures. Additionally, the research primarily employed observational methods and checklist-based assessments, which may not fully capture underlying organizational or behavioral factors affecting safety practices. These constraints suggest that caution should be exercised when extrapolating the results to broader contexts.