Abstract

This study investigates the axial electron density distribution in two plasma antenna configurations excited by a surface wave microwave discharge and its influence on the radiation pattern of antennas. The axial plasma electron density profiles were characterized using two non-invasive diagnostic techniques: the resonant cavity measurements in the TM110 mode and the waveguide transmission analysis. A linear decrease in the plasma electron density along the antenna was observed. The effective electrical length of the plasma antennas, accounting for this density distribution, is found to be approximately half the physical plasma column length. Numerical simulations employing COMSOL Multiphysics based on the Drude model revealed that a realistic nonuniform axial plasma electron density distribution markedly modifies the antenna radiation characteristics. For the wave-type plasma monopole antenna, this results in a shift in the emission maximum, a reduction in the main lobe amplitude, a nearly twofold broadening of the main lobe, and the disappearance of the side lobe. For the quarter-wave-type plasma asymmetric dipole antenna, there is a reduction in the main lobe amplitude without a shift in the maximum and a broadening of the main lobe due to an increase in the side-lobe level and its merging with the main lobe.

1. Introduction

Plasma antennas use partially or fully ionized gas or semiconductor-based plasmas as the conducting medium instead of metal to create an antenna. These antennas offer several advantages over conventional metal antennas, including electronic tunability, reduced radar cross-section, and others. The antenna characteristics can be controlled by varying the plasma electron density or modifying its spatial configuration (such as the presence of plasma, length, radius, etc.) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. A distinctive feature of plasma antennas is the necessity to generate and sustain plasma with appropriate density, as well as the importance of accurately measuring this density, considering the specific characteristics of the antenna structure. Plasma electron density is determined by both the antenna configuration and the method of plasma generation.

The most common plasma antennas use low-pressure gas-discharge tubes filled with noble gases, including commercial fluorescent lamps. The most studied configuration is the plasma asymmetric dipole antenna (PADA), also called a “monopole antenna.” Plasma in these antennas can be generated by various sources: using DC discharges [8,9,10,12,13], AC discharges [8,9,14], or radio frequency (RF) and microwave (MW) surface-wave discharges [3,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], either from a dedicated signal source [1,2,18] or from a single RF/MW signal source used for both plasma generation and signal transmission [3,20].

Surface-wave discharges are particularly advantageous for creating extended plasma columns with electron densities on the order of 1011–1012 cm−3 while consuming relatively low power (approximately 5–40 W). However, in such discharges, the plasma electron density typically decreases linearly along the axis as the distance from the wave source increases [17,21], which is critical when defining the antenna’s effective electrical size. The effective electrical length is determined by the current distribution that shapes the antenna’s far-field radiation at the resonant frequency.

Previous research on the influence of spatial plasma electron density variations for antenna characteristics of plasma antennas has employed diverse approaches, often with specific limitations. FDTD simulations in [22] focused primarily on analyzing the radial and axial density profile and its effect on input impedance, gain, and efficiency. While works on self-consistent [23] and three-dimensional [24] numerical models, based on the Boltzmann equation, provided physical insight but focused primarily on effects of plasma electron density distribution on near-field characteristics. In the specialized case of a magnetized plasma antenna [25], axial non-uniform distribution was modeled. Dorbin et al. [26] developed an analytical model for estimating monopole plasma antenna efficiency but acknowledged that discrepancies with experiments arose from difficulties in accurately simulating end-column density variations. Experimental measurements of the axial density distribution for plasma antennas were conducted with some configurations of surface wave discharges at 6 MHz and 2400 MHz in works [27,28].

It is also relevant to consider studies on plasma sources that provide insights into radiation behavior. Nowakowska et al. [29], in their numerical study of an atmospheric-pressure surfatron source, demonstrated that the direction of space-wave radiation shifts with variations in plasma column length. While their research aimed at optimizing plasma generation efficiency, it underscores the fundamental relationship between plasma distribution and radiation properties that is crucial for antenna design.

Notably, many existing studies on plasma antennas still either neglect spatial density variations in their models or treat them with simplified approximations. This oversight can lead to substantial discrepancies between simulated and experimental antenna performance, ultimately resulting in suboptimal antenna design.

This study combines experimental and numerical approaches to how axial plasma electron density distributions in surface-wave sustained discharges affect the effective electrical length and radiation patterns of two plasma antenna configurations.

2. Plasma Monopole and Asymmetric Dipole Antennas

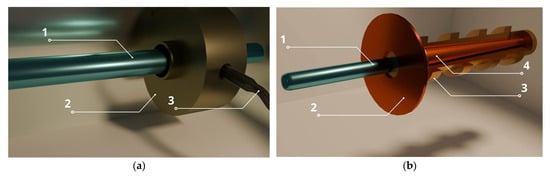

This study investigates two plasma-based antennas: the first is a wave-type plasma monopole antenna (PMA) without a ground plane (Figure 1a), and the second is a quarter-wave-type plasma asymmetric dipole antenna (PADA) with a circular ground plane (Figure 1b). In both cases, the plasma is generated inside the discharge tube by a microwave surface wave discharge powered by a Vertex VX-2100 transceiver (Vertex Standard Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), operating at frequencies of 445 MHz with a maximum output power of 45 W.

Figure 1.

Schemes: (a) wave-type PMA with a surfatron: 1—gas-discharge tube with plasma, 2—surfatron, 3—coaxial cable; (b) PADA with circular ground plane: 1—gas-discharge tube with plasma, 2—disk ground plane, 3—outer conductor of coaxial connector, 4—inner conductor of coaxial connector.

The first antenna (Figure 1a) consists of a transparent bactericidal lamp that is a quartz glass tube (1) with a length of 900 mm and an inner diameter of 24 mm (outer diameter is 26 mm), a surfatron (2), the design of which is described in detail in [30,31], and a coaxial cable (3). The second antenna (Figure 1b) consists of a commercial fluorescent lamp that is a quartz glass tube (1) with a length of 160 mm and an inner diameter of 10 mm (outer diameter is 12 mm), a copper shield (2), and a coaxial connector with an inner conductor (3) and outer conductor (4). The lamps used in both antennas are filled with argon at a pressure of approximately 1–5 Torr and mercury vapor at a pressure of around 10−2 Torr [32,33]. A distinctive feature of the described antennas is that a portion of the supplied RF energy is consumed to sustain the discharge within the lamps: for the PADA, up to 5 W is required to maintain the plasma, while for a PMA, up to 20 W is needed. A bactericidal lamp, which lacks a phosphor coating and emits primarily in the UV range (~254 nm), was utilized in the wave-type PMA. The commercial fluorescent lamps, featuring a phosphor that converts UV radiation to visible light, were employed in the quarter-wave-type PADA.

3. Experimental Setup and Numerical Model

To evaluate the electron density of plasma in a gas discharge, both contact (probe-based) and non-contact (radio-frequency and optical) diagnostic methods are employed. Contact methods involve various types of probes, such as Langmuir probes and grid probes. However, these techniques can significantly distort the electric field distribution in the near-field region of the plasma antenna.

Among non-contact methods for determining plasma electron density, cavity and waveguide techniques are widely used [27,28,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. These approaches utilize cylindrical and rectangular microwave cavities, as well as different types of waveguides and resonant waveguide structures functioning as filters. A key advantage of microwave cavity methods is that they do not require the insertion of probes into the plasma and are independent of prior knowledge about the type of gas or its pressure.

Cavity and waveguide methods differ in the principle of interaction between the electromagnetic field and the plasma. In the cavity method, the plasma tube is placed inside the resonator, and the measured parameters (frequency shift, quality factor) depend on changes in the dielectric permittivity within the field volume of a specific mode. This provides high sensitivity to local variations in electron density but imposes restrictions on the geometry and size of the plasma tube, which must match the field distribution inside the cavity. In the waveguide method, the plasma tube is inserted into the propagation path of the electromagnetic wave, and diagnostics are based on measuring transmission and reflection coefficients. This approach allows the use of tubes with larger diameters and lengths, but the sensitivity is averaged over the entire waveguide cross-section and depends on boundary matching conditions. Thus, the difference lies not only in the tube diameter but also in the nature of wave–plasma interaction: in a cavity, the effect is determined by the perturbation of the resonant mode, while in a waveguide, it results from changes in the parameters of the propagating wave. Both microwave methods determine the volume-averaged electron density of a plasma part placed in the resonant cavity or in the waveguide cross-section.

In the present study, to experimentally investigate the axial distribution of electron density in the radiating element of the antenna, we employed both cavity and waveguide methods (similar to those described in [36,37,38]), using TM110(E110) mode. The plasma in the radiating elements was generated by different excitation schemes: in the case of the wave plasma monopole antenna, microwave power from the generator was coupled through a coaxial input to a loop antenna placed around the discharge tube inside a metallic resonator (surfatron), providing inductive heating of the gas; in the case of the asymmetric dipole antenna with a circular screen, plasma was sustained by direct microwave power delivery via a coaxial feed, similar to conventional metallic dipole antennas. Previous work with rectangular cavities has shown that accounting for higher-order modes and boundary effects can significantly improve the precision of complex permittivity measurements, which is especially important when dealing with materials of high dielectric permittivity [27,41].

3.1. Cavity Method

The resonant cavity method employs a microwave resonator (hollow resonant cavity) to characterize a plasma column enclosed within a dielectric tube. The complex permittivity of the plasma is determined by measuring the shift in the resonator’s fundamental frequency. For a gas-discharge plasma in an electromagnetic field, the real part of the permittivity is given by the Drude model:

For the condition of weakly collisional plasma (ω ≫ ν), the average volumetric electron density <ne> can be derived from the resonant frequency shift. This relationship is expressed as [35,36]:

here ω0 is the resonant frequency of the empty cavity, Δω—is the frequency shift induced by the plasma, Vpl and Vcav are the volumes of the plasma and cavity, respectively, ncr—is the critical plasma electron density at which ωp = ω0. The coefficient Cv is a geometry-dependent form factor that relates the measured frequency shift to the electron density. This factor is governed by the spatial configuration of the electric field within the cavity.

In our experiments, a microwave cylindrical resonance cavity with a radius of 45 mm and height of 30 mm was used in the TM110 (E110) mode with f0 = 3.78 GHz (ncr = 17.7 × 1010 cm−3). The typical plasma electron density is 1011–1012 cm−3 for microwave surface wave low-pressure discharges, and the electron-electron collision frequency for plasma in both tubes is about 107 s−1, which allowed us to use a collisionless approach.

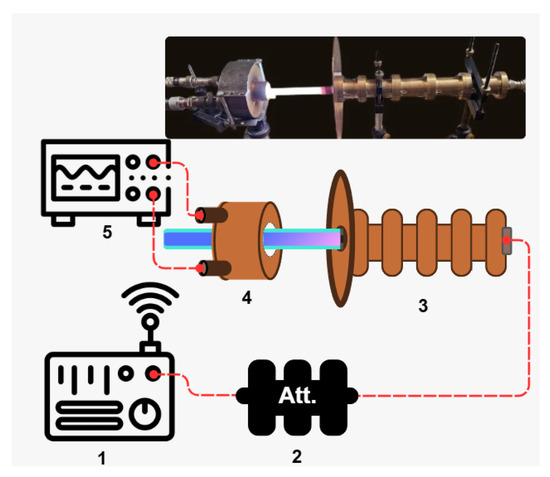

The schematic and photograph of the experimental setup for the cavity method are shown in Figure 2. The setup includes a plasma antenna with a coaxial matching device (CMD) connected either directly or via a 3 dB attenuator (to reduce power) to the Vertex StandardVX-2100 radio transceiver (Vertex Standard Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), as well as the 10 cm cylindrical cavity. The cavity’s scattering parameter S21 (forward transmission coefficient between two ports) was measured over the 2–4 GHz frequency range using a Keysight N9912A vector network analyzer (Keysight Technologies, Inc., Santa Rosa, CA, USA). From the measured S21 curves, the resonant frequency ω0 and its shift Δω were determined and used to calculate the average electron density ⟨ne⟩ in the plasma tube.

Figure 2.

Schematic and photo of the stand for measuring the plasma concentration in the plasma antenna using a cylindrical cavity: 1—VX-2100 transceiver, 2—attenuator, 3—plasma antenna with coaxial matching device, 4—cylindrical cavity, 5—vector circuit analyzer Keysight N9912A.

The typical inaccuracy of estimation of electron density value by this method is up to 20% [36,39,40].

3.2. Waveguide Method (Transmission Method)

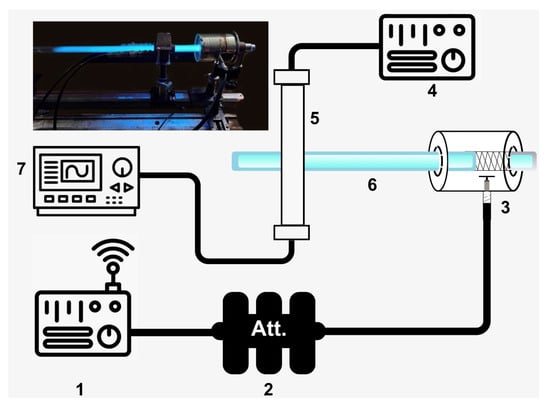

In the waveguide method, also known as the transmission method, introducing a plasma object with a refractive index different from that of air into the waveguide cross-section leads to a measurable change in the transmission of the waveguide section. At a fixed frequency, the change in transmission ΔT(ne) or the scattering parameter ΔS21(ne) can be correlated with the electron density [43,44]. To implement this method (Figure 3), a waveguide section was fabricated using a rectangular waveguide with cross-sectional dimensions of 35 × 15 mm2. A 15 mm-radius through-hole was made in the center of the wide walls, where the antenna’s discharge tube was positioned with its axis perpendicular to the waveguide wide walls. The waveguide could be moved along the tube axis.

Figure 3.

Schematic and photo of a stand for measuring plasma concentration in a plasma antenna using a waveguide: 1—VX-2100 transceiver, 2—attenuator, 3—surfatron, 4—SK4-61 super heterodyne spectrometer (RIAP, Nizhniy Novgorod, Russia), 5—35 × 15 mm2 rectangular waveguide, 6—discharge tube, 7—high-frequency signal generator G4-82 (Nizhny Novgorod Scientific and Production Association named after M.V. Frunze, Nizhniy Novgorod, Russia).

Diagnostic microwave radiation in the frequency (fd = 5.5–7.5 GHz) was transmitted through the waveguide. The corresponding critical electron density lies within the range ncr = 3.75 × 1011–6.98 × 1011 cm−3. The transmission coefficient of the diagnostic signal was recorded using a superheterodyne receiver. This method is suitable for discharge tubes with a diameter exceeding 20 mm. The normalization procedure for this method is detailed in [44]. The measurement uncertainty associated with this method is approximately 50%.

The potential influence of the resonant cavity and waveguide on the surface wave propagation was carefully considered. While partial wave reflection from the metallic boundaries of both diagnostics is expected, several factors mitigate its impact on the measured results. The transverse dimensions of the diagnostics (9 cm for the cavity, 3.5 cm for the waveguide) are substantially smaller than the excitation wavelength (67 cm). Furthermore, for the given plasma parameters, a significant fraction of the surface wave energy is localized within the plasma column and the near-wall region, reducing its susceptibility to external perturbation. Monitoring of the plasma luminosity confirmed that while the diagnostics, especially the longer cavity, could cause a local shortening of the plasma column, this effect was spatially confined. The perturbation influenced the density profile downstream of the measurement point but did not alter the locally measured value or the overall axial trend, which was the primary focus of this study.

3.3. Numerical Models of Plasma Antennas in COMSOL Multiphysics

A numerical simulation model was developed using the COMSOL Multiphysics software (Version 5.4). Maxwell’s equations were solved using the finite element method with a tetrahedral mesh. Given that the electromagnetic wavelength was approximately 70 cm, much larger than the individual structural elements, the mesh was set to 50 elements per wavelength to ensure adequate spatial discretization and computational accuracy.

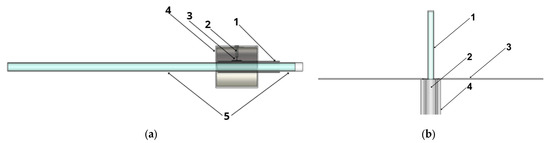

Two models were created to replicate the configurations of the experimental setups (Figure 4). In the first model, representing the traveling-wave PMA (Figure 4a), the surfatron was excited by a TEM wave delivered through a coaxial cable. In the second model, corresponding to the quarter-wavelength PADA with a ground plane, a coaxial matching device was used, also powered by a TEM wave. The geometric dimensions of the models fully correspond to the dimensions of real antennas.

Figure 4.

Antenna models in COMSOL Multiphysics: (a) wave-type PMA with 1—metal tube, 2—coaxial feed, 3—microwave connector, 4—surfatron launcher, 5—glass discharge tube with plasma; (b) quarter-wave-type PADA with 1—gas discharge tube with plasma, 2—inner conductor of coaxial feed, 3—ground plane disc, 4—outer conductor of coaxial feed.

Metallic components were modeled using the perfect electric conductor (PEC) approximation, and quartz glass tubes were modeled as a dielectric-like medium with constant ε = 4. The plasma behavior was described using the Drude model, which accounts for its dispersive and conductive properties. The Drude model is a classic and widely used approximation for describing the behavior of free electrons in plasmas and metals. The model’s main advantages lie in its simplicity and clarity. It effectively describes electrical conductivity by taking into account the free motion of electrons between collisions with ions, which helps explain the electrodynamic properties of plasma. To describe plasma, the Drude model considers an electron gas in which electrons move in straight lines until random collisions with ions. The time between collisions is stable and described by memoryless statistics. This approach significantly simplifies calculations and yields solutions that are consistent with more complex and resource-intensive modeling methods, such as the PIC method. Because of this, the Drude model is often used to quickly estimate the dielectric properties of plasma and its electrical conductivity. The Drude model also has significant limitations. It does not take into account interactions between electrons and between electrons and ions, with the exception of simple collisions. This approach does not account for quantum effects, collective excitations, and nonlinear processes in plasma, which are important in some cases. The model also cannot describe processes associated with nonequilibrium states. Furthermore, the lack of consideration of real particle dynamics and interactions limits the model’s accuracy for complex and inhomogeneous plasmas.

The electron-electron collision frequency corresponds to experimental data. The axial distribution of the plasma electron density was assumed to be uniform and with measured gradients, while the radial distribution was assumed to be uniform in all studied cases. The computational domain was enclosed by boundary conditions simulating open space, placed sufficiently far from the active region to minimize their effect on the electromagnetic field distribution. After solving for the electromagnetic field in the near-field region, a near-to-far-field transformation was performed to obtain the antenna radiation pattern.

4. Results and Discussion

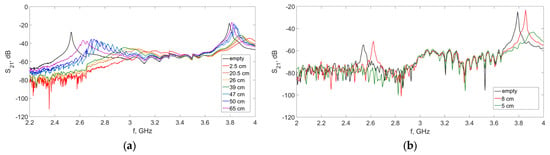

Figure 5 shows the S21 spectra of a 10 cm cavity for two types of antennas: a wave-type antenna (tube diameter 24 mm) and a quarter-wave-type antenna (tube diameter 12 mm), measured at different positions along the discharge tubes from the power feed point. The S21 parameter was recorded for two levels of input power: the nominal value of 45 W and a reduced level of 22.5 W (−3 dB). Figure 5 presents an example of the S21 spectrum obtained at the nominal power of 45 W.

Figure 5.

Experimental S21 spectra measured at different cavity positions relative to the feeding point of plasma antennas at maximum power: (a) wave-type PMA with a tube diameter of 24 mm; (b) quarter-wave-type PADA with a tube diameter of 12 mm.

As shown in Figure 5a,b, when the cavity is moved closer to the excitation point (surfatron or the antenna ground plane), the resonance characteristics of the TM110 (E110) mode change noticeably, while the lower-frequency mode TM010 (E110) becomes undetectable as its resonance curve drops below the noise level of the vector network analyzer (Figure 5b). Therefore, for the quarter-wave-type PADA, measurements were performed using the TM110 (E110) mode. The measured frequency shifts were used to calculate the axial electron density distribution in the studied antennas by Formula (2) (Figure 6a and Figure 7).

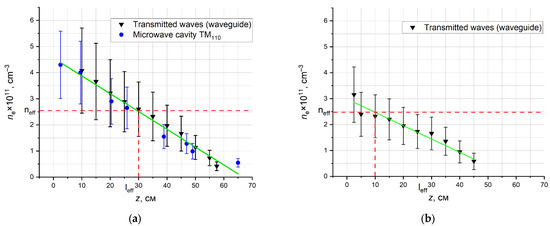

Figure 6.

Axial distribution of electron density in the wave-type PMA: (a) at maximum input power 45 W; (b) at reduced power 22.5 W. Red dotted line shown effective plasma electron densities neff and corresponds them effective antenna lengths.

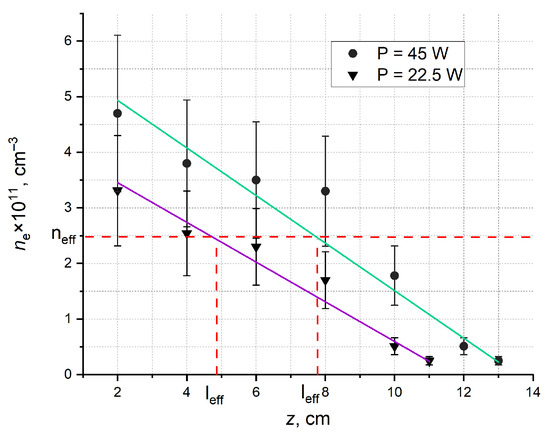

Figure 7.

Axial distribution of electron density in the quarter-wave-type PADA operating in the E110 mode at maximum (45 W) (green line) and reduced −3 dB (22.5 W) (purple line) input power. Red dotted line shown effective plasma electron densities neff and corresponds them effective antenna lenghts.

Plasma electron density measurements under 45 W nominal power (without attenuation) reveal an axial density gradient from 4–5 × 1011 cm−3 near the surfatron to near 5 × 1010 cm−3 at the distal end (60–70 cm, Figure 6b). The observed intermodal differences originate from electromagnetic field inhomogeneities within the resonator. All three diagnostic methods demonstrate good mutual consistency, particularly at axial positions beyond 40–50 cm from the plasma source.

With 3 dB additional attenuation (corresponding to 22.5 W input power to the discharge tube), the plasma electron density decreases by a factor of 1.5–2 along the entire tube length (Figure 6b). While the full-power operation yields ne = 3–4 × 1011 cm−3 near the microwave input, the reduced-power conditions produce initial densities of 2.5–3.5 × 1011 cm−3. The axial density profile maintains an approximately linear decay, with end-point values decreasing to 0.5–1 × 1011 cm−3. This consistency confirms the dominant role of axial distance from the plasma generation point, in agreement with previous surface-wave discharge [21] and plasma antenna studies under different conditions [42]. Quantitative analysis of Figure 6 yields a plasma electron density gradient of k = −0.07 ± 0.02 × 1011 cm−4 for both 45 W and 22.5 W input powers.

Under the same experimental conditions, the electron density near the ground plane of the quarter-wave-type plasma antenna (Figure 7) was found to be near 4.7 × 1011 cm−3 at an input power of 45 W and near 3.2 × 1011 cm−3 at 22.5 W. These values are within the measurement uncertainty and are consistent with the results obtained for the wave-type antenna. The density decrease also remains approximately linear but occurs more rapidly due to the shorter tube length. The axial plasma electron density gradient in the discharge tube of the quarter-wave-type antenna was determined to be k = −0.45 ± 0.13 × 1011 cm−4 for both power levels, 45 W and 22.5 W.

According to [45,46], for the PADA operating at the frequency f0 = 445 MHz (ω0 = 2.8·1010 rad/s), the minimum required plasma electron density is ne = 2.5 × 1011 cm−3 (corresponding to ωp = 10·ω0). To achieve radiation parameters comparable to those of a metallic antenna, the plasma electron density should be ne = 2.3 × 1012 cm−3 (ωp = 30·ω0). Based on the minimum required density, the effective electrical length of the antennas was estimated. For the wave-type antenna at 45 W, the effective length was approximately 30 cm, which is close to half the wavelength of the microwave generator at f = 445 MHz, and about 5 cm at 22.5 W input power. For the quarter-wave-type antenna, the effective electrical length was about 8 cm and 4 cm at 45 W and 22.5 W, respectively. These values are significantly shorter than the resonance length of 16.5 cm at f = 445 MHz, indicating that the antenna operates in a weakly directional mode unless the shortening effect of plasma antennas is taken into account [46].

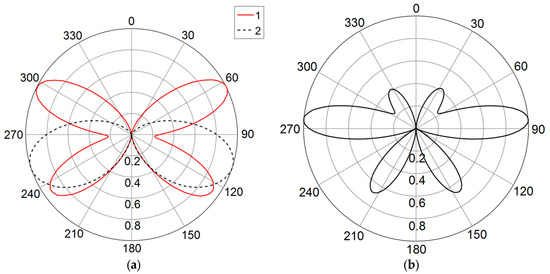

COMSOL Multiphysics simulations were employed to analyze the radiation patterns of wave-type PMA and quarter-wave-type PADA under varying plasma electron density distributions. The E-plane radiation patterns for different plasma profiles are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. The value of 0° of the angle phi on all patterns coincides with the axis of the gas discharge tube of the plasma antenna in the direction from the surfatron or screen. For the PMA with uniform plasma distribution on Figure 8a (radiation pattern 1), the radiation pattern exhibits a main lobe at 127° with a 36.3° half-power beamwidth (−3 dB level) and an effective length of 70 cm, demonstrating slight rear-hemisphere radiation dominance. Implementing a linearly decaying plasma electron density profile at 45 W input power (radiation pattern 2) reduces the antenna’s effective length by more than half (to 30 cm) and significantly alters the radiation characteristics: the main lobe shifts by 19° (to 106°), broadens to 54°, and completely suppresses side lobes. Quantitative pattern parameters are provided in Table 1. Figure 8b shows the radiation pattern for an effective antenna length of 30 cm with uniform plasma electron density distribution. This radiation pattern appears intermediate between graphs 1 and 2 in Figure 8a. The radiation pattern for the uniform distribution in Figure 9a is very similar to the experimental and modeling results for a plasma antenna at 2.45 GHz generated by an AC discharge at 10 kHz obtained in [47].

Figure 8.

Radiation patterns (numerical simulation) of the wave-type PMA for different axial plasma electron density distributions (a): 1—uniform distribution; 2—axial linear decrease at 45 W, (b) for effective antenna length 30 cm with uniform plasma electron density distribution.

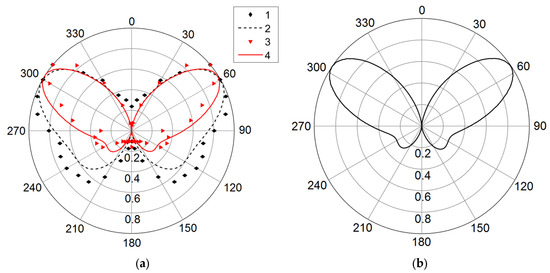

Figure 9.

Radiation patterns for: (a) 1—metal antenna (experiment [20]); 2—PADA with axial linear decrease in the plasma electron density at 45 W (simulation); 3—PADA (experiment [20]); 4—PADA with uniform plasma electron density distribution (simulation); (b) effective antenna length 8 cm with uniform plasma electron density distribution.

Table 1.

Parameters of the radiation patterns of the wave-type PMA for different axial plasma electron density distributions.

Similar effects are observed for the quarter-wave-type plasma antenna (Figure 9). Radiation pattern (1) corresponds to the experimental radiation pattern of the metallic antenna [20], radiation pattern (2) represents the simulated pattern for the PADA with a uniform plasma electron density distribution, radiation pattern (3) shows the experimental pattern of the plasma antenna [20], and radiation pattern (4) corresponds to the simulation with a linear decrease in electron density along the antenna length at 45 W input power.

For the uniform 16 cm plasma column (line 2), the main lobe is directed at 58° with a beamwidth of 58.8°. Introducing a linear density gradient (line 4) effectively reduces the radiating length by half (to 8 cm), broadens the main lobe to 107.4°, and shifts its direction slightly to 61°. This configuration causes merging of the main and side lobes, forming a radiation pattern that closely matches the experimental data for the metallic antenna (line 1) [20]. Quantitative radiation pattern parameters are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of radiation pattern of the quarter-wave-type PADA for different axial plasma electron density distributions.

The physical mechanism involves three interrelated effects: the reduced effective length alters the current distribution along the antenna, phase relationships in the radiating system are modified, and the electrical size decreases relative to the operating wavelength. These results demonstrate that plasma inhomogeneity critically impacts antenna performance—linear density gradients cause: 1.5–2× beamwidth broadening, main lobe angular shift and 2–3× reduction in effective electrical length. This finding has important implications for reconfigurable antenna designs, where precise control of plasma electron density profiles may enable dynamic beam steering without mechanical components.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates two configurations of the plasma antennas using gas-discharge tubes, where a microwave discharge both sustains the plasma and provides the high-frequency signal, enabling electronic control of the antenna’s radio-frequency properties. Two diagnostic techniques were employed: (1) a method using a cylindrical microwave resonance cavity operating in the TM110 mode and (2) a transmitted waves method with a rectangular waveguide. Near-linear decay from 4–5 × 1011 cm−3 to ~0.5–1 × 1011 cm−3 occurred along both the antennas’ lengths. A 3 dB reduction in input power reduced the plasma electron density by a factor of 1.5–2. The axial density gradient was defined as k = −0.07 ± 0.02 × 1011 cm−4 for PMA and k = −0.45 ± 0.13 × 1011 cm−4 for PADA. The antenna’s effective electrical length decreased with power attenuation, falling below resonant values for these antenna types.

Numerical simulations in COMSOL Multiphysics based on the Drude model revealed that a realistic nonuniform axial plasma electron density distribution, ne(z), markedly modifies the antenna radiation characteristics. For PMA, this results in a shift in the emission maximum, a reduction in the main lobe amplitude, nearly a twofold broadening, and the disappearance of the side lobe. For PADA, there is a reduction in the main lobe amplitude without a shift in the maximum and a broadening of the main lobe due to an increase in the side-lobe level and its merging with the main lobe. These effects lead to reduced directivity, broadening of the main lobe, and, in the case of PMA, a shift in the emission maximum. Good agreement between experimental data and simulation results is achieved when the actual axial density profile is incorporated, emphasizing the necessity of accounting for realistic plasma distributions in both analysis and design of plasma-based radiating structures. These findings underline the significance of plasma electron density control and gradient compensation in the development of next-generation plasma antennas with improved performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N.B., V.P.S., M.S.U. and N.G.G.-z.; Methodology, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z., S.E.A., D.M.K., M.S.U. and E.M.K.; Software, S.E.A.; Validation, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z., S.E.A. and D.M.K.; Formal analysis, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z. and S.E.A.; Investigation, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z., S.E.A., D.M.K., M.S.U. and E.M.K.; Resources, E.M.K.; Data curation, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z. and S.E.A.; Writing—original draft, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z., S.E.A., M.S.U., E.M.K. and N.G.G.-z.; Writing—review and editing, N.N.B., V.P.S., V.I.Z., S.E.A., M.S.U., E.M.K. and N.G.G.-z.; Visualization, V.P.S., V.I.Z. and S.E.A.; Supervision, N.N.B. and N.G.G.-z.; Project administration, N.G.G.-z.; Funding acquisition, E.M.K. and N.G.G.-z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the RUDN University Scientific Projects Grant System, project №025323-2-000.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to S.N. Zamuruev, L.V. Simonchik, and K.F. Sergeichev for their support in organizing and conducting the experimental measurements, as well as for their valuable suggestions and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | Alternating Current |

| CMD | Coaxial matching device |

| DC | Direct Current |

| FDTD | Finite Difference Time Dom9ain |

| MW | Microwave |

| PADA | Plasma asymmetric dipole antenna |

| PEC | Perfect electric conductor |

| PMA | Plasma monopole antenna |

| RF | Radio frequency |

| TEM | Transverse electromagnetic (wave) |

| UV | Ultraviolet radiation |

References

- Borg, G.G.; Harris, J.H.; Martin, N.M.; Thorncraft, D.; Milliken, R.; Miljak, D.G.; Kwan, B.; Ng, T.; Kircher, J. Plasmas as antennas: Theory, experiment and applications. Phys. Plasmas 2000, 7, 2198–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.P.; Whichello, A.P.; Cheetham, A.D. Physical characteristics of plasma antennas. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2004, 32, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istomin, E.N.; Karfidov, D.M.; Minaev, I.M.; Rukhadze, A.A.; Tarakanov, V.P.; Sergeichev, K.F.; Trefilov, A.Y. Plasma asymmetric dipole antenna excited by a surface wave. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2006, 32, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.Q.; Gao, M.; Tang, C.J. Radiation theory of the plasma antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2011, 59, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bora, D. A reconfigurable plasma antenna. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 053303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Sakai, O. Analytical formulation for radiation characteristics of a surface wave sustained plasma antenna. Phys. Plasmas 2019, 26, 073506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, T.; Greig, J.; Murphy, D.; Perin, J.; Pechacek, R.; Raleigh, M. On the feasibility of using an atmospheric discharge plasma as an RF antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1984, 32, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T. PlasmaAntennas; Artech House: Norwood, MA, USA, 2020; 352p. [Google Scholar]

- Magarotto, M.; Sadeghikia, F.; Schenato, L.; Rocco, D.; Santagiustina, M.; Galtarossa, A.; Horestani, A.K.; Capobianco, A.D. Plasma antennas: A comprehensive review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 80468–80490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ja’afar, H.; Abdullah, R.; Omar, S.; Shafie, R.; Ismail, N.; Rustam, I. Design and development of plasma antenna for Wi-Fi application. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2017, 9, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jha, M.; Panghal, N.; Pandey, A.K.; Patel, U.; Kumar, R.; Pathak, S.K. Wideband frequency reconfigurable plasma antenna launched by surface wave coupler. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2024, 176, 155113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Yamaura, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Tanaka, T.; Chiba, H.; Ogino, H.; Takahagi, K.; Kitagawa, S.; Taniguchi, D. Theoretical and experimental investigation of plasma antenna characteristics on the basis of gaseous collisionality and electron density. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 54, 016001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usachonak, M.S.; Simonchik, L.V.E.; Bogachev, N.N.; Andreev, S.E.E. Application of gas-discharge plasma at reduced pressure as a radiating body of an asymmetrical dipole antenna. Zhurnal Tekhnicheskoi Fiz. 2024, 94, 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, Q. Plasma antennas driven by 5–20 kHz AC power supply. AIP Adv. 2015, 5, 127114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivelpiece, A.W.; Gould, R.W. Behavior of Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) under High Pressures. J. Appl. Phys. 1959, 30, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granatstein, V.L.; Schlesinger, S.P. Observation of nonquasistatic plasma surface waves. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 36, 3503–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.; Shivarova, A.; Trivelpiece, A.W. Experimental investigations of the propagation of surface waves along a plasma column. Plasma Phys. 1982, 24, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghikia, F.; Noghani, M.T.; Simard, M.R. Experimental study on the surface wave driven plasma antenna. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2016, 70, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Yamaura, S.; Fukuma, Y.; Sakai, O. Radiation characteristics of input power from surface wave sustained plasma antenna. Phys. Plasmas 2016, 23, 093504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogachev, N.N.; Gusein-zade, N.G.; Nefedov, V.I. Radiation pattern and radiation Spectrum of the plasma asymmetrical dipole antenna. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2019, 45, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.; Zakrzewski, Z. Plasma sources based on the propagation of electromagnetic surface waves. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1991, 24, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghikia, F.; Hodjat-Kashani, F.; Rashed-Mohassel, J.; Ghayoomeh-Bozorgi, J. Characteristics of plasma antennas under radial and axial density variations. In Proceedings of the Electromagnetics Research Symposium Proceedings, Moscow, Russia, 19–23 August 2012; pp. 1212–1215. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z. A Self-consistent model on cylindrical monopole plasma antenna excited by surface wave based on the Maxwell-Boltzmann equation. J. Electromagn. Anal. Appl. 2011, 3, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- CHen, Z.; Zhu, A.; Junwei, L.V. Three-dimensional model of cylindrical monopole plasma antenna driven by surface wave. Wseas Trans. Commun. 2013, 12, 63–72. Available online: https://www.wseas.com/journals/communications/2013/56-325.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2025).[Green Version]

- Li, X.S.; Hu, B.J. FDTD analysis of a magneto-plasma antenna with uniform or nonuniform distribution. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2010, 9, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbin, M.R.; Mohassel, J.A.R.; Sadeghikia, F.; Ja’afar, H.B. Analytical estimation of the efficiency of surface-wave-excited plasma monopole antennas. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2022, 70, 3040–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbin, M.R.; Mohassel, J.A.R.; Sadeghikia, F.; Ja’afar, H.B. Determination of the plasma electron density in a plasma antenna based on image analysis and LIVPD graphs. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 120721–120727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghikia, F.; Dorbin, M.R.; Mohassel, J.A.R.; Ja’Afar, H.B. Measurement of the plasma parameters using the stationary method in a resonant cavity. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2023 17th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Florence, Italy, 26–31 March 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, H.; Lackowski, M.; Moisan, M. Radiation losses from a microwave surface-wave sustained plasma source (surfatron). IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2020, 48, 2106–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.; Chaker, M.; Zakrzewski, Z.; Paraszczak, J. The waveguide surfatron: A high power surface-wave launcher to sustain large-diameter dense plasma columns. J. Phys. E Sci. Instrum. 1987, 20, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisan, M.; Levif, P.; Nowakowska, H. Space-wave (antenna) radiation from the wave launcher (surfatron) before the development of the plasma column sustained by the EM surface wave: A source of microwave power loss. AMPERE Newsl. 2019, 98, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, G.G.; Waymouth, J.F. Light Sources. Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; Robert, A.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 557–595. [Google Scholar]

- The Fluorescent Lamp—Gas Fillings. Available online: https://lamptech.co.uk/Documents/FL%20Gases.htm (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Thomassen, K.I. Microwave plasma density measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 36, 3642–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, M.A.; Wharton, C.B.; Furth, H.P. Plasma Diagnostics with Microwaves; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965; Available online: https://archive.org/details/plasmadiagnostic0000heal/page/n479/mode/2up (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Golant, V.E. Microwave Methods for Plasma Diagnostics; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1968. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Wellenstein, H.F.; Frommhold, L.; Robertson, W.W. Calibration procedure to correct for the effects of dielectric containers in microwave plasma density measurements. J. Appl. Phys. 1972, 43, 3716–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyskocil, J.; Musil, J. Microwave measurement of electron density and temperature in plasmas produced by a surfatron at atmospheric pressure. J. Phys. D App. Phys. 1980, 13, L25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Bosisio, R.G. Composite hole conditions on complex permittivity measurements using microwave cavity perturbation techniques. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 1982, 30, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, A.S.; Frolov, K.S.; Shevchenko, Y.I. High-frequency discharge in a flow of molecular gases at medium pressures. Sov. Phys. Tech. Phys. 1988, 33, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Astafiev, A.M.; Kudryavtsev, A.A.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X. The possibility of measuring electron density of plasma at atmospheric pressure by a microwave cavity resonance spectroscopy. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2021, 49, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usachonak, M.S.; Akishev, Y.S.; Kazak, A.V.; Petryakov, A.V.; Simonchik, L.V.; Shkurko, V.V. Electron density in dielectric barrier discharge argon plasma jet determination by using a microwave waveguide filter. Tech. Phys. 2023, 68, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, V.I.; Karfidov, D.M.; Sergeichev, K.F. Propagation of microwave discharge sustained by surface wave in quartz tube filled with low-pressure air. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2020, 46, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, V.I.; Karfidov, D.M. Microwave Low-Pressure Gas Discharge Sustained by a Standing Surface Wave in the Dipolar Mode. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2023, 49, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogachev, N.N.; Bogdankevich, I.L.; Gusein-zade, N.G.; Sergeychev, K.F. Operation modes and characteristics of plasma dipole antenna. Acta Polytech. 2015, 55, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdankevich, I.L.; Gusein-zade, N.G.; Rukhadze, A.A. Surface wave and linear operating mode of a plasma antenna. Plasma Phys. Rep. 2015, 41, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, R.R.; Sinha, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Pathak, S.K.; Shah, S.N. Numerical design and experimental characterization of reconfigurable leaky wave plasma antenna. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 152347–152357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).