1. Introduction

Materials used in the critical parts of hypersonic vehicles—such as leading edges, nose tips, and propulsion system components—must withstand extreme heat, rapid thermal cycling, very high mechanical stresses, and chemically aggressive environments caused by plasma exposure and oxidation [

1]. Polymer-derived ceramics (PDCs), particularly SiMBCN and SiMCN (where M = Hf, Zr, Ti, Ta, or their combinations), are classified as ultra-high temperature ceramics (UHTCs) and have emerged as promising candidates for aerospace applications in such extreme environments [

2]. In PDCs, the relatively low processing temperatures and innovative fabrication methods, compared to traditional ceramic processing, enable the production of near-net-shaped ceramic components. Moreover, the chemical composition can be precisely tailored, and the properties of the final material (e.g., thermal stability) can be optimized through the careful design and selection of suitable organic precursors [

3].

For SiCN polymer precursors, pyrolysis above 1000 °C generally yields an amorphous microstructure, typically described as a random Si–C–N network consisting of SiC

xN

(4−x) units (1 ≤ x ≤ 4), with the relative volume fractions depending on the starting precursor compositions [

3,

4]. In carbon-rich precursors, the final product contains both the amorphous Si–C–N network and an additional phase of “free” (excess) carbon. Upon further heating above 1000 °C, the amorphous network undergoes structural rearrangements. One of the key objectives in PDCs is to maintain the amorphous state to the highest possible temperature. SiCN is notable in this respect, with a relatively high crystallization temperature (~1400 °C), beyond which the metastable SiCN glass transforms into thermodynamically stable SiC and/or Si

3N

4 phases (depending on precursor chemistry and pyrolysis atmosphere), together with free amorphous and/or turbostratic carbon [

5]. The thermal stability of SiCN PDCs within the ternary Si–C–N system is limited by the carbothermal reduction of Si

3N

4, which occurs at 1484 °C under 1 atm N

2, as shown in Equation (1). In compositions without significant excess carbon, the upper stability limit is instead governed by the direct decomposition of Si

3N

4 at 1841 °C in 1 atm N

2 (Equation (2)) [

6,

7].

Thus, the presence of excess carbon can influence the system’s thermal stability by enabling carbothermal reduction in a N

2 atmosphere. However, the actual role of carbon depends on how it is incorporated into the amorphous structure. Kleebe et al. [

8] reported that a carbon-rich precursor remained amorphous after heat treatment, while a less carbon-rich precursor crystallized into large Si

3N

4 grains within the amorphous matrix at 1540 °C in N

2, due to structural rearrangements involving SiN

4 and SiC

4 units. To overcome these limitations, strategies such as precursor blending [

9,

10,

11] and the incorporation of active fillers [

12] have been investigated to suppress carbothermal reactions and enhance the high-temperature stability of SiCN PDCs above 1400 °C in N

2 atmospheres.

Mixing SiCN precursor with Hf and/or Ti and pyrolysis in Ar and N

2 results in the formation of UHTC nanocomposites due to the formation of high melting nano-crystalline carbide or carbonitride (HfC, HfCN, TiC, TiN, TiCN) distributed within amorphous SiCN and crystalline SiC/Si

3N

4 matrix [

13,

14,

15], which makes them attractive candidates for aerospace and hypersonic applications [

2]. Furthermore, in recent years, mixing polymer precursors with two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials has gained attention, as it enables combining the unique functionalities of 2D materials with the intrinsic high-temperature stability and oxidation resistance of PDCs [

16]. Among two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials, MXenes are an ideal nanofiller due to their high thermal and mechanical stability, which enables the fabrication of high-performance UHTC nanocomposites through the PDC strategy [

17,

18]. MXenes are ternary carbides and nitrides with a formula of M

n+1X

nT

x, where M is an early transition metal, X is carbon or nitrogen, and n= 1–3. T represents the surface termination groups that are mostly =O, −F, and −OH, and x in T

x represents the number of surface functionalities [

19,

20].

Although numerous studies have investigated polymer-derived SiHfCN ceramics, the influence of the side groups attached to silicon atoms in the starting precursors on the rearrangement of the amorphous network and the final crystalline products remains poorly understood [

4,

10]. To our knowledge, no study has reported the synthesis of SiHfCN ceramics from a single-source precursor prepared by reacting Durazane 1800 with TDMAH, and only a limited number of studies have addressed MXene-modified polymer-derived ceramics, particularly for non-oxide PDCs [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Moreover, the role of MXene surface functional groups in modifying the amorphous PDC network and controlling crystallization has not been fully elucidated.

In this work, we aim to address these gaps by investigating the effects of Ti3C2 MXene incorporation on the thermal stability and crystallization behavior of SiHfCN ceramics. We hypothesize that MXene addition can enhance the stability of amorphous SiCN against crystallization into Si3N4 and suppress carbothermal reduction of Si3N4 into SiC. To test this hypothesis, SiHfCN and Ti3C2–SiHfCN composite ceramics were synthesized via pyrolysis at 1000 °C, followed by heat treatment at 1600 °C in N2. The amorphous-to-crystalline transformations were systematically characterized using TEM, SEM, and XRD, enabling a detailed understanding of the structural and compositional evolution of these materials.

2. Materials and Methods

The starting materials for synthesizing SiHfCN ceramics were Durazane 1800 ((SiCHCH

2NHCH

3)0.2n(SiHCH

3NH)0.8n, Merck KGaA, Frankfurter Strasse 250, 64293 Darmstadt, Germany) and TDMAH (Sigma-Aldrich, Eschenstr. 5, 82024 Taufkirchen, Germany, ≥99.99%). We used the procedure reported in Ref. [

26] for the synthesis and delamination of Ti

3C

2T

x MXene and the methodology previously reported [

27] for surface functionalization of Ti

3C

2T

x using [3-(2-aminoethylamino)-propyl]trimethoxysilane (AEAPTMS; ≥80%). All mixing of polymer precursors and cross-linking operations were conducted under an Ar atmosphere in the glovebox. For clarity, the samples without adding Ti

3C

2T

x MXene were labeled SiHfCN, while those with Ti

3C

2T

x addition were labeled MXene-SiHfCN.

For the synthesis of SiHfCN samples, 1.5 g TDMAH (30 wt.%) was dissolved in 6 mL anhydrous toluene and then added dropwise to a solution of 3.5 g Durazane 1800 in 5 mL anhydrous toluene with stirring (110 rpm) at room temperature for 2 h. The weight ratio of Durazane 1800 to TDMAH was 7/3. The obtained solution was heated to 80 °C and held for 0.5 h, and subsequently subjected to vacuum (2 × 10−2 mbar) for 45 min. The solution was heated to 110 °C and held for an additional hour in Ar to ensure the toluene was removed entirely. The obtained product was cross-linked at 250 °C for 3 h to form a yellow preceramic solid, which was then ground using an alumina mortar and pestle to produce a fine powder.

For the synthesis of the MXene-SiHfCN precursor, 4.6 g of Durazane 1800 was mixed with 2.01 g TDMAH and 0.30 g of Ti3C2Tx MXene. The MXene was incorporated at approximately 13 wt.% relative to the TDMAH content. The total MXene content in the mixture corresponds to approximately 4.34 wt.% of the total system mass. The MXene-SiHfCN sample preparation was similar to SiHfCN. That is, 0.3 g Ti3C2Tx MXene was mixed with a solution of 4.5 g Durazane 1800 in 30 mL anhydrous toluene with stirring (300 rpm) at room temperature for 5 h. 2.01 g TDMAH was dissolved in 9 mL anhydrous toluene and then added dropwise to a (Mxene + Durazane) mixture and mixed for another 14 h (300 rpm/room temperature). The obtained mixture was heated to 80 °C and held for 1 h, and subsequently subjected to vacuum (2 × 10−2 mbar) for 5 h. The mixture was heated to 100 °C, held for 2 h, followed by heating to 120 °C and holding for 2 h in Ar. The obtained product was cross-linked at 250 °C for 3 h to form a black preceramic solid, which was then ground using an alumina mortar and pestle to produce a fine powder.

The crosslinked powders were warm pressed in a 12.7 mm steel die. The die, loaded with polymer powder, was placed between the platens of a hydraulic press equipped with a digital temperature controller. The polymer powders were pressed at 39.5 MPa at room temperature and then heated to 265 °C with a heating rate of 3.5 °C/min, followed by a 30 min hold at the peak temperature. After the assembly cooled to room temperature within two hours, the green bodies were removed from the die. The warm-pressed green bodies were pyrolyzed at 1000 °C, 1200 °C, and 1600 °C (heating rate of 1 °C/min) in an electric furnace (1370-20 Horizontal Tube Furnace, CM Furnaces Inc., Bloomfield, NJ, USA) under a nitrogen atmosphere with a 2 h hold at the peak temperature. The final products were analyzed using Raman spectroscopy (mIRage-LS optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) microscope) with a wavelength of 785 nm within the spectral range of 700–2000 cm−1; multiple spots (≥3) were measured on each sample to ensure reproducibility. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed on a NETZSCH, Selb, Germany, STA 449 F3 Jupiter in N2 with a heating rate of 1 °C/min. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was conducted using Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands, with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) images were performed using Helios 5 UX DualBeam, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, with a working distance of 4 mm. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) using PHI 5000 VersaProbe II (Physical Electronics, Chanhassen, MN, USA) equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) operated at 25 W. The spectra were collected in the survey mode with a pass energy of 187.85 eV and in the high-resolution mode with a pass energy of 23.5 eV. All binding energies were calibrated with reference to the C 1s peak at 284.8 eV. The spectra were processed and deconvoluted using Multipak software (v9.7, Physical Electronics) with the Gaussian–Lorentzian peak shape. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using Talos 200i TEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with an operating voltage of 200 kV was used for high-resolution microstructural characterization. TEM samples were prepared using a focused ion beam (FIB) lift-out technique (Helios 5 UX DualBeam, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). All measurements were performed on multiple areas or replicates to ensure reproducibility. Instruments were calibrated using standard references where applicable, and experimental conditions were carefully controlled and documented to allow accurate replication of the study.

3. Results

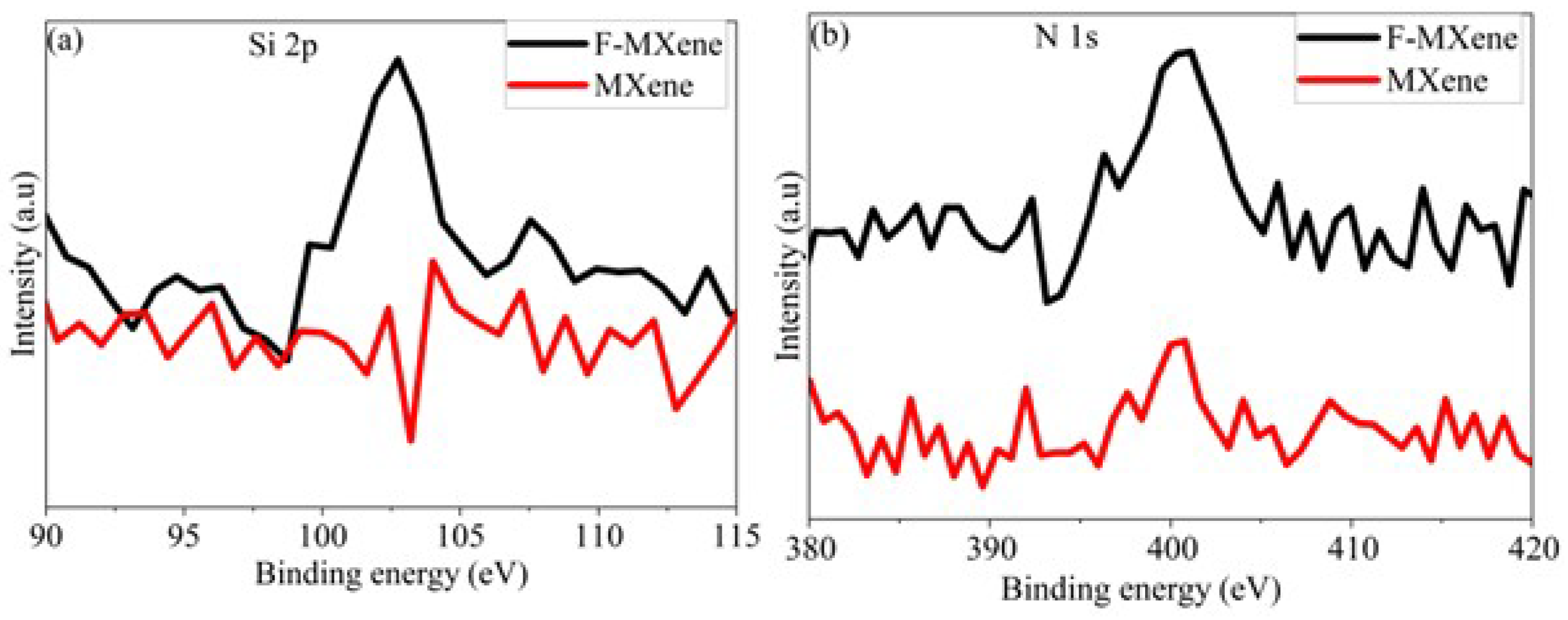

Figure 1 and

Figure S1 show the XPS spectra of Ti

3C

2T

x MXene before (MXene) and after functionalization (F-MXene). The presence of O and F in the survey spectrum (

Figure S1a) indicates the surface termination during etching. Furthermore, the appearance of a more intense N 1s peak, together with the presence of the Si 2p peak after functionalization, indicates the successful functionalization of the MXene surface by AEAPTMS. The high-resolution O 1s and C 1s spectra (

Figure 1c,d) show deconvoluted peaks corresponding to Ti–O, Ti–OH, and C–O/Si–O components in O 1s, and to C–Ti, C–C, C–O, and O–C=O species in C 1s. These chemical states indicate the presence of oxygen- and silicon-containing groups on the surface, consistent with the expected interaction between AEAPTMS and MXene. Similar results were reported in studies where MXene was functionalized with amine-containing silane coupling agents [

27,

28]. It should be noted that XPS is a semi-quantitative, surface-sensitive technique probing only the top few nanometers of the sample; therefore, the observed signals only reflect surface chemistry.

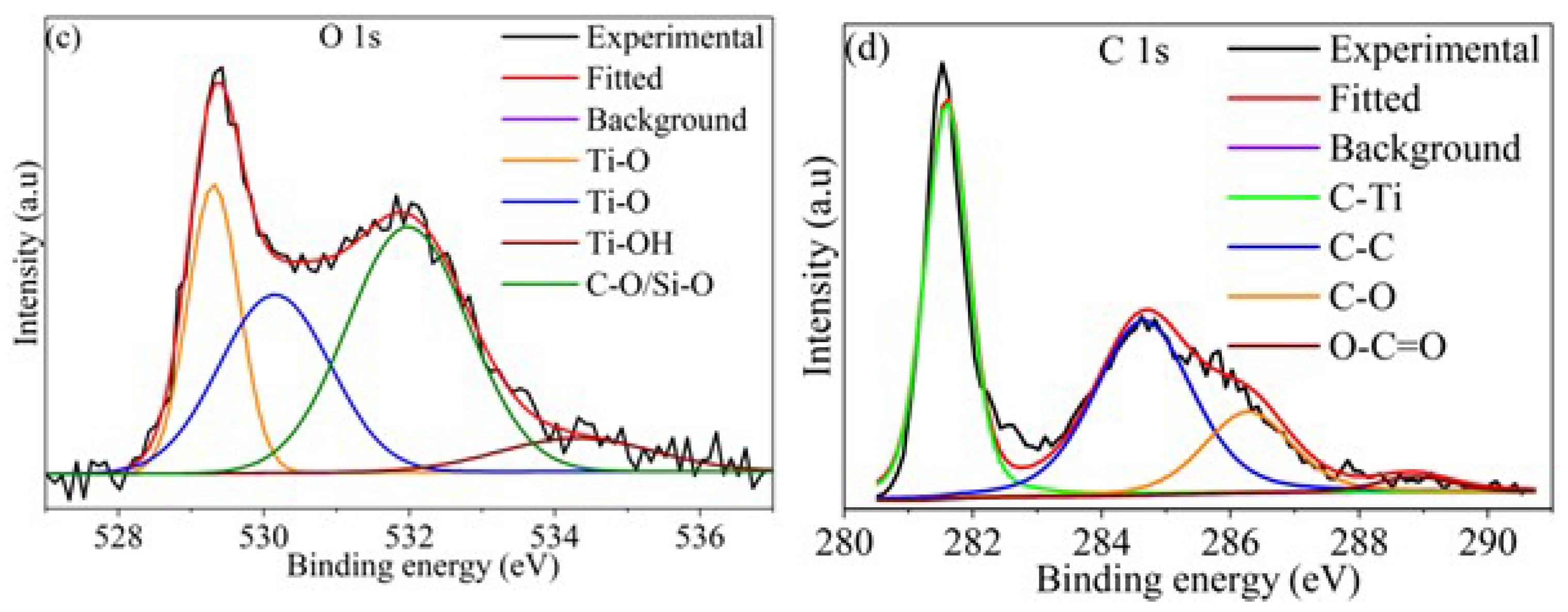

Figure 2 shows the TGA–differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves of SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN, revealing thermal behaviors during polymer-to-ceramic conversion under nitrogen. The ceramic yield is about 87 wt.% for both samples, which is comparable with the ceramic yield reported for polymer-derived SiHfCN (~80 wt.%) [

15], SiZrBCN (~78 wt.%) [

12], SiZrCN (~77 wt.%) [

12], and SiHfBCN (~80 wt.%) [

29], and higher than that reported for Durazane 1800 (~70 wt.% in N

2 up to 1700 °C) [

29]. In both samples, an initial mass loss of 4% from room temperature to about 300 °C could be due to the volatilization of oligomers. A significant mass loss (~9 wt.% ) accompanied by two exothermic peaks at 300 and 800 °C from 300 to 800 °C might be due to the release of ammonia gas and CH

4 due to rearrangement processes based on reactions between ≡Si-CH

3 and =N-H groups in the ceramization process of Durazane 1800 [

12,

29]. These exothermic peaks are more pronounced in the MXene-SiHfCN samples. An additional endothermic peak at ~600 °C is observed only in the MXene-SiHfCN case, which might be attributed to the Ti

3C

2T

x phase [

30]. Furthermore, previous results in the literature show an improvement in thermal and mechanical properties due to the crosslinking effect between MXene Ti

3C

2T

x nanosheets and the molecular chains of the polymer [

18,

31] or the interfacial interaction between MXene Ti

3C

2T

x and other ceramics, e.g., TiC [

32] or ZrB

2 [

33].

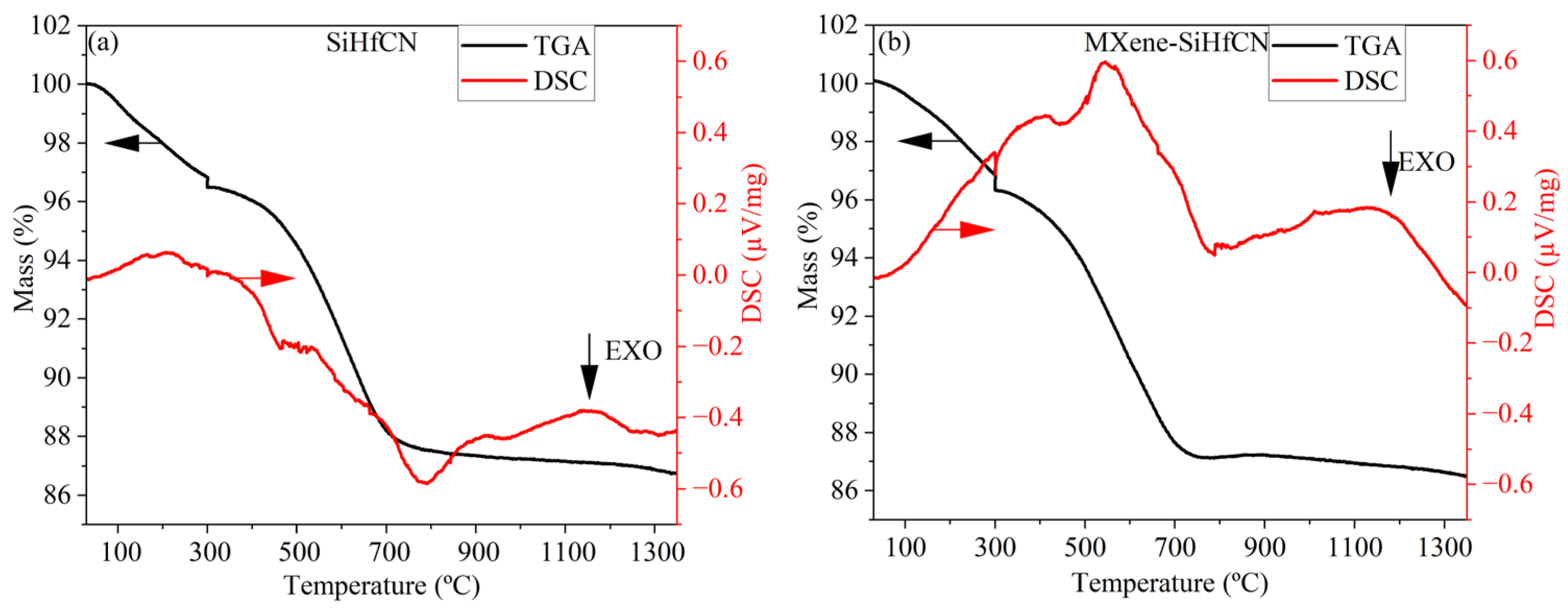

Figure 3 presents the XRD patterns of SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN samples after pyrolysis in N

2 at 1000, 1200, and 1600 °C. For both samples, the XRD results indicate that the ceramics remain amorphous after pyrolysis at 1000 and 1200 °C. At 1600 °C, distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to α/β-Si

3N

4 and HfC

xN

1−x phases appear, while the broad halo observed at 2θ ≈ 30.6° after pyrolysis at 1000 and 1200 °C becomes sharper, indicating partial crystallization of the amorphous matrix. In addition, a weak diffraction signal corresponding to SiCN is observed near 35°, consistent with the reported reference pattern (PDF 01-074-2308). Notably, no SiC peaks are detected in either sample, indicating that α/β-Si

3N

4 remains stable up to 1600 °C. In the MXene-SiHfCN sample, additional peaks corresponding to Si

2N

2O, HfO

2, TiN, and TiC are observed. Moreover, the Si

2ON

2 peaks are more pronounced and exhibit higher intensity than the α/β-Si

3N

4 peaks in MXene-SiHfCN compared to SiHfCN, suggesting that Si

2N

2O preferentially forms or crystallizes from the SiCN matrix rather than α/β-Si

3N

4.

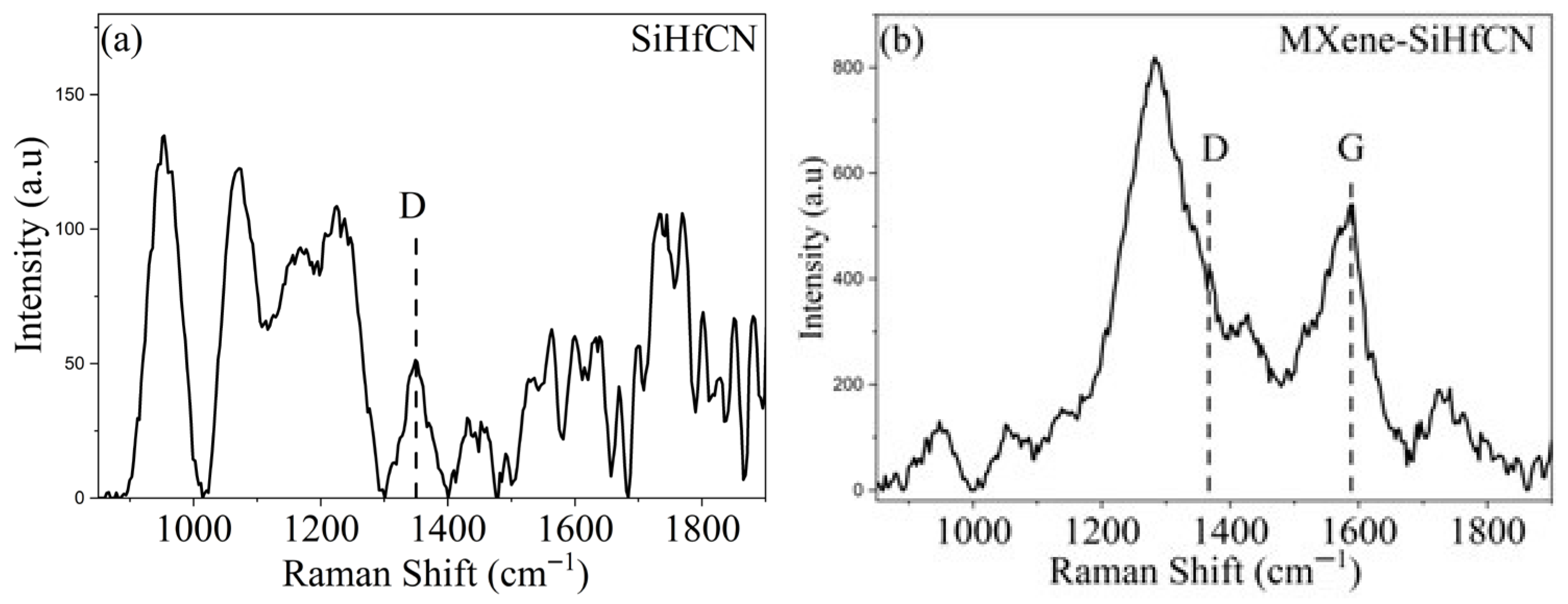

Figure 4 shows the Raman spectra of SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN samples pyrolyzed at 1600 °C in N

2. The dashed lines indicate the typical features of disordered and graphitic carbon, namely the D band (~1350 cm

−1) and the G band (~1580 cm

−1), which signify carbon segregation into disordered or nanocrystalline graphitic clusters [

34]. In MXene-SiHfCN, a broad G band centered near ~1580 cm

−1 is observed, while the intensity feature in that region for SiHfCN is weak and complex (multiple small peaks/noise). Therefore, a definitive graphitic G band is not resolved in this sample. Moreover, the Raman band intensities of MXene-SiHfCN are higher compared to those of SiHfCN, indicating enhanced carbon-related features. The results further imply that free disordered carbon detected by Raman spectroscopy may be partially incorporated into the silicon backbone, which can enhance the thermal stability of amorphous SiCN and promote local crystallization of Si

3N

4 [

8]. This interpretation is consistent with the XRD results, which reveal peaks of Si

3N

4 along with an amorphous SiCN matrix. Furthermore, the absence of SiC peaks in the XRD patterns, despite the presence of free carbon in the Raman spectra, indicates that Si

3N

4 does not react with free carbon to form SiC up to 1600 °C in N

2. In contrast, previous studies on the pyrolysis of polyvinylsilazane (SiN

1.25C

1.5H

4.75) at 1600 °C [

5] and on a single-source precursor of Durazane 1800 containing zirconium and boron (SiZrBCN) at 1700 °C [

12] in N

2 reported β-SiC formation, where both the D and G bands decreased and eventually disappeared due to the consumption of free carbon by reaction with Si

3N

4. The bands observed around 1000 cm

−1 might be assigned to Si-O and/or Si-N stretching vibrations, consistent with previous reports [

35,

36]. The region between 1100 and 1300 cm

−1 is likely associated with Hf-N vibrational mode [

37,

38]. The broad features appearing between 1700 and 1850 cm

−1 are most likely noise or artifacts arising from sample handling or instrumental effects.

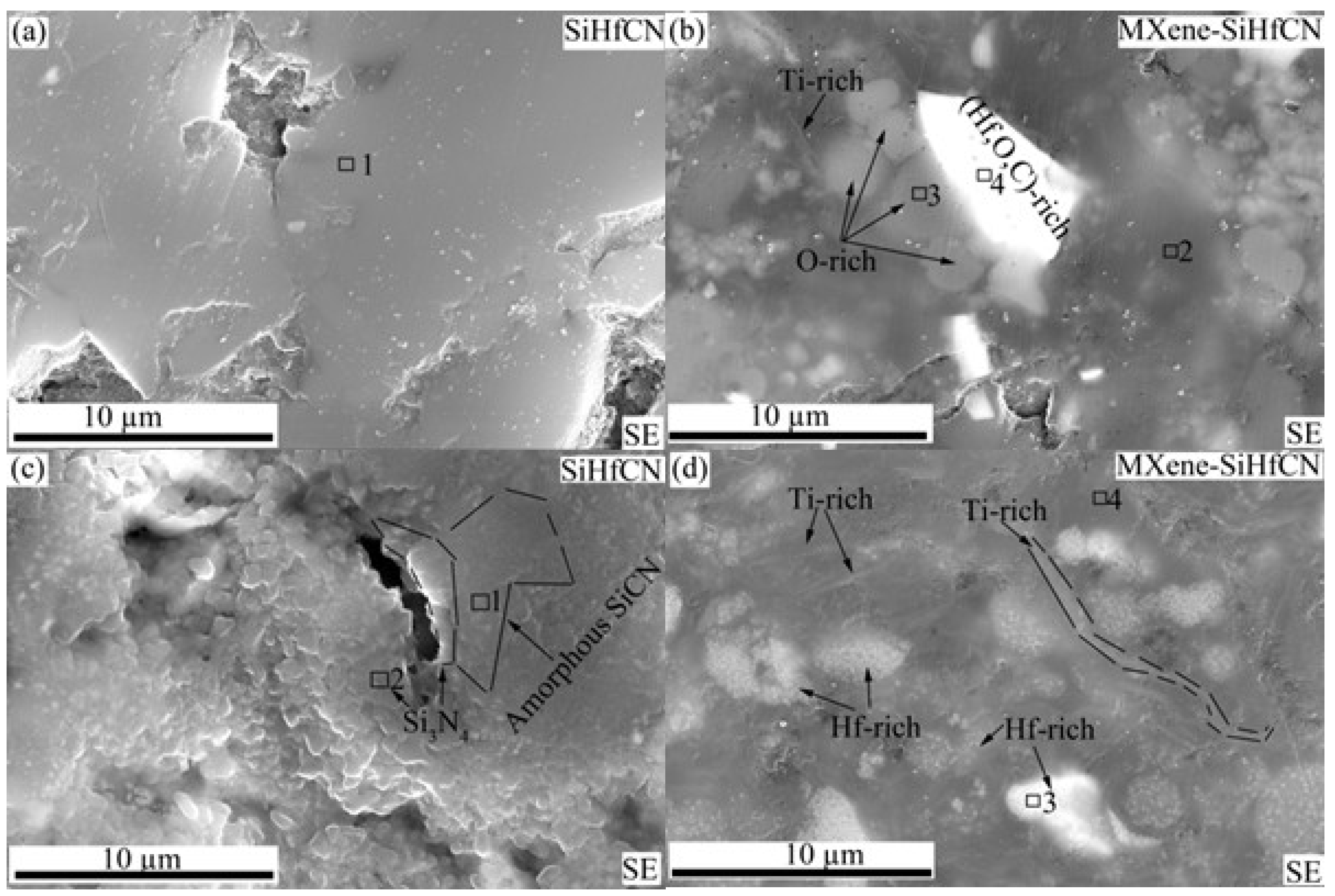

Figure 5a,b show SEM images of SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN after pyrolysis at 1200 °C. In SiHfCN (

Figure 5a), the microstructure appears relatively uniform with no obvious contrast. SEM/energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) analysis (Box 1 in

Figure 5a and

Table 1) confirms that the material is mainly composed of C, Si, and N, with a small amount of Hf. The detected oxygen likely originates from exposure during transfer processing from the glovebox to the warm press. In contrast, MXene-SiHfCN (

Figure 5b) exhibits clear contrast variations, reflecting chemical segregation into regions of different compositions. EDS results show that the darker regions (Box 2) are similar in composition to SiHfCN with a small amount of Ti. The gray circular regions (Box 3) are enriched in O, Si, and C, while the very bright inclusions (Box 4) are rich in Hf, C, and O, suggesting the formation of Hf-rich oxide domains. In addition, faint line-like features correspond to Ti-rich regions. Although these areas exhibit distinct elemental compositions, the absence of sharp peaks in the XRD patterns at 1200 °C confirms that they remain amorphous. Upon further heating to 1600 °C, these segregated domains crystallize into phases such as Si

3N

4, HfO

2, TiN, and TiC, as revealed by XRD.

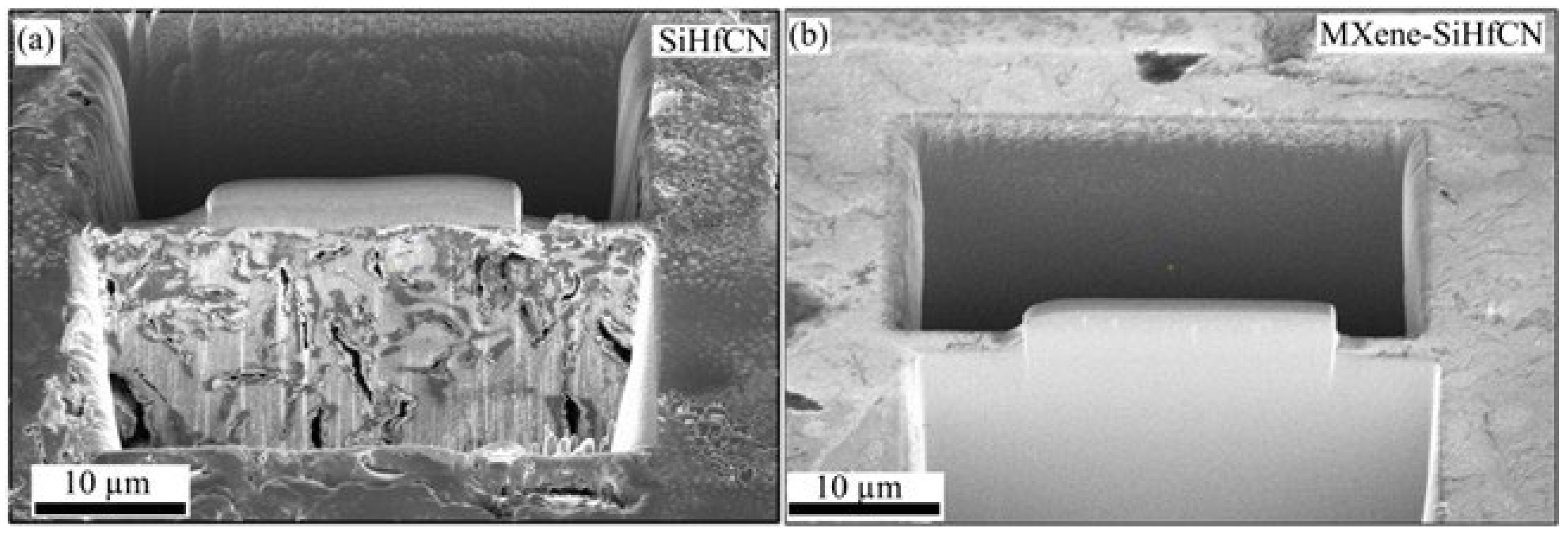

SEM images of SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN after pyrolysis at 1600 °C in N

2 are shown in

Figure 5c,d and

Figures S2–S4. After pyrolysis, the surface of SiHfCN is covered with white whisker-like features (

Figure S1a), which can be easily removed by brushing and were identified as Si

3N

4 by XRD and SEM/EDS (

Figure S1). Similar Si

3N

4 whisker formation has been reported for SiCN precursors pyrolyzed above 1500 °C in N

2 [

6,

7,

11,

39,

40,

41]. In addition, macroscopic cracks visible to the naked eye were observed on the surface of SiHfCN but not in MXene-SiHfCN (

Figure S1b). SEM analysis (

Figure 5c) shows that SiHfCN exhibits longitudinal cracks and pores with typical dimensions of ~5 µm in length and ~1 µm in width. Adjacent to these cracks, grains of 0.5–1 µm are observed, whereas regions farther away display a relatively smooth and uniform morphology. SEM/EDS of the uniform regions (Box 1 in

Figure 5c,

Table 2) indicates a composition of mainly Si, C, and N, consistent with amorphous SiCN. By contrast, the grainy features near cracks (Box 2 in

Figure 5c,

Table 2) contain more nitrogen and less carbon, with an atomic N/Si ratio of 1.4, suggesting the formation of Si

3N

4. Across different locations, the oxygen content remained below 10.0 at.%. In MXene-SiHfCN, the surface is more uniform, and the longitudinal cracks characteristic of SiHfCN are absent (

Figure 5d), as further confirmed by the focused ion beam microscopy (FIB)-SEM cross-section in

Figure 6. SEM/EDS analyses (Box 3 in

Figure 5d and

Figures S3 and S4) reveal Hf-rich and Ti-rich regions with distinct contrast within the microstructure. Additionally, oxygen levels in MXene-SiHfCN were at least twice those of SiHfCN (Box 4 in

Figure 5d and

Table 2), suggesting that the matrix evolves toward SiOCN rather than SiCN, with Hf-rich and Ti-rich phases incorporated within the SiOCN structure. It should be noted that the SEM/EDS results are qualitative and are used here to highlight compositional contrasts between regions rather than to provide exact atomic ratios.

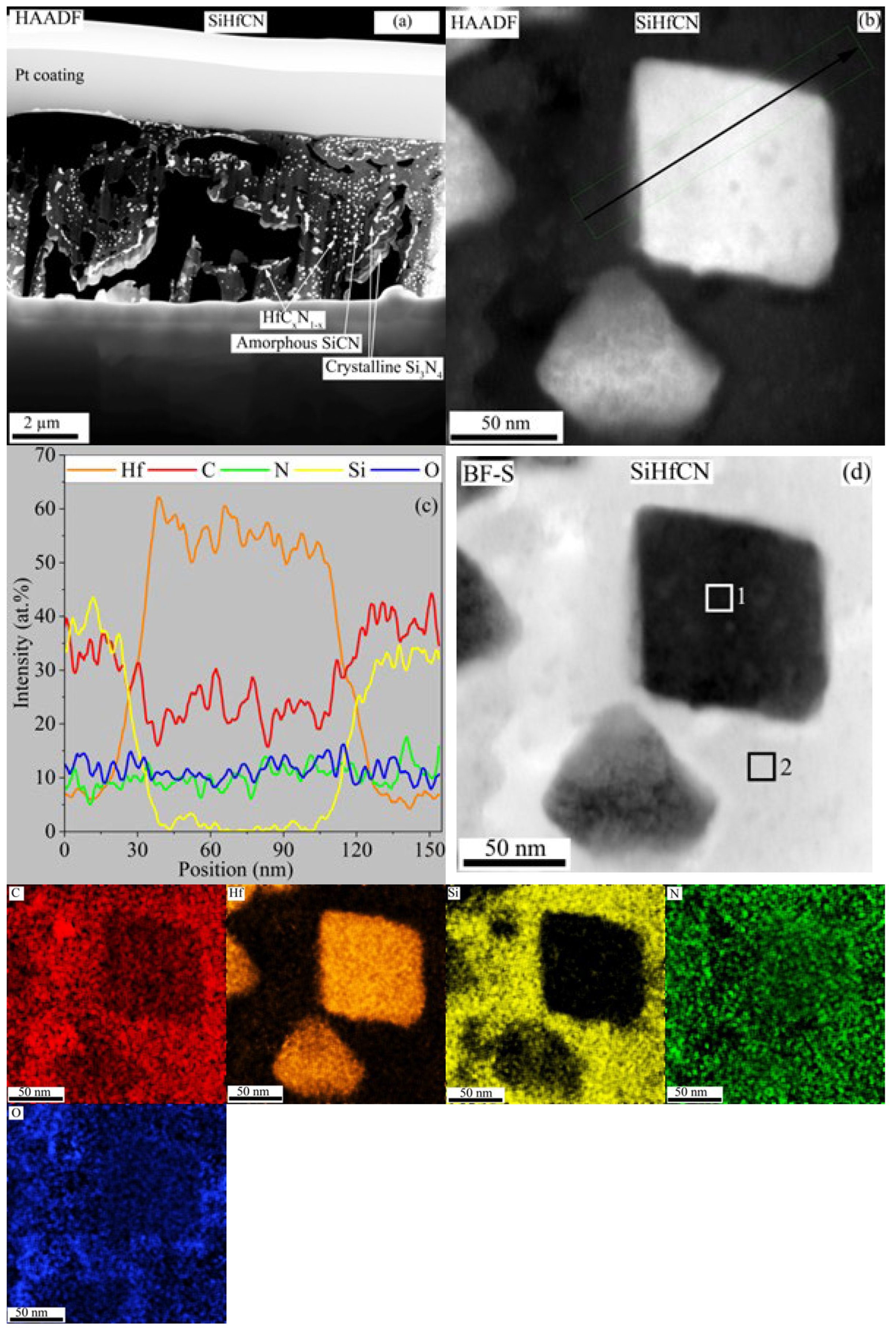

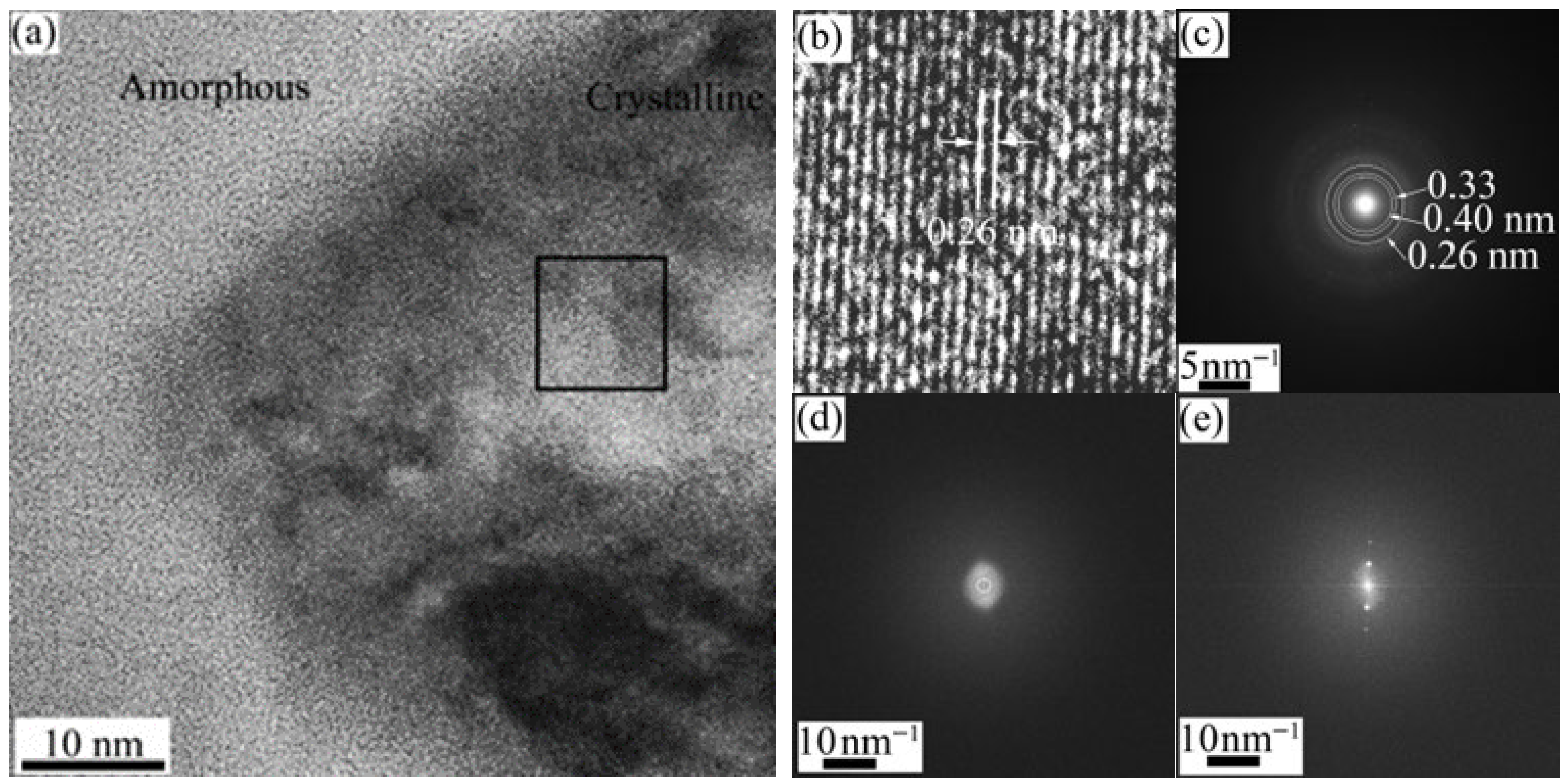

TEM analysis of SiHfCN after pyrolysis at 1600 °C in N

2 is shown in

Figure 7. In regions near cracks and pores (

Figure 7a), crystalline Si

3N

4 was observed, whereas the areas farther from the cracks remained amorphous SiCN, in agreement with the SEM and XRD results. Within the amorphous matrix and adjacent to Si

3N

4, fine HfC

xN

1−x nanoparticles were detected. A higher-magnification view (

Figure 7b) reveals slightly faceted HfC

xN

1−x particles (50–100 nm). The corresponding line scan across one particle (

Figure 7c) shows that the Hf-rich regions are strongly enriched in Hf with lower Si and C, while the surrounding SiCN matrix contains more Si and C, relatively less N, and ~10 at.% O. The EDS elemental maps of

Figure 7b are presented in

Figure 7d, confirming the compositional differences between the Hf-rich particles (HfC

0.14N

0.10O

0.14) and the surrounding SiCN (SiHf

0.12C

1.02N

0.30O

0.25) matrix (Box 1, 2, and

Table 3). High-resolution TEM (

Figure 8a) shows that the SiCN matrix is amorphous, while the HfCN nanoparticles are crystalline with a measured lattice spacing of ~0.26 nm (

Figure 8b). The corresponding selected area diffraction (SAD) pattern (

Figure 8c) exhibits a diffuse ring typical of amorphous phases, along with distinct rings. The first ring at ~0.40 nm is consistent with SiN

4 units [

42], the second ring at ~0.33 nm can be attributed to SiN

xC

y [

42], and the third ring at ~0.26 nm close to the lattice distance for the (111) plane of HfC (0.267 nm) and/or HfN (0.262 nm), in good agreement with the XRD results. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) from the amorphous SiCN area in

Figure 8a is shown in

Figure 8d, while the FFT from the crystalline region is shown in

Figure 8e.

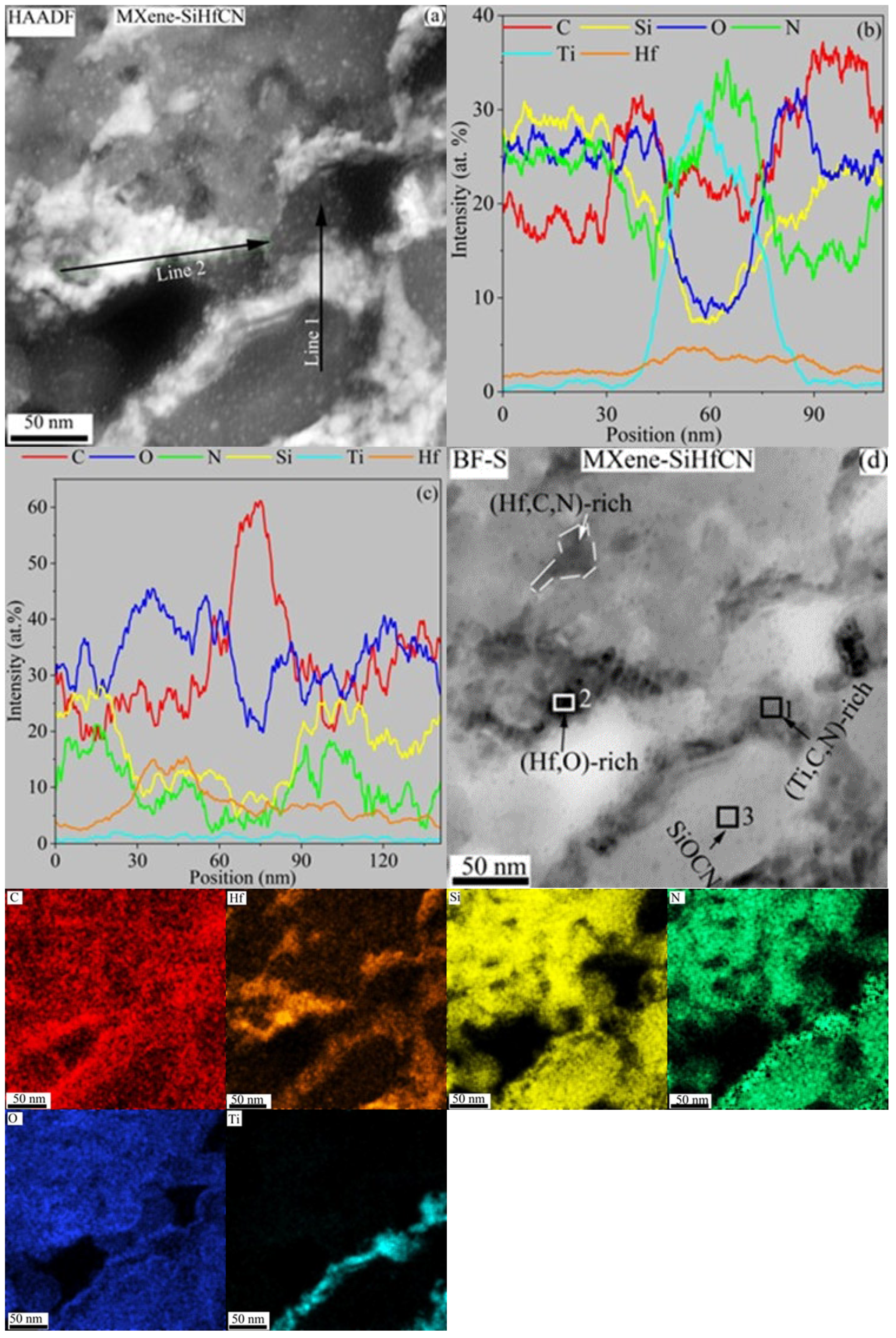

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show TEM analysis of MXene-SiHfCN after pyrolysis at 1600 °C in N

2.

Figure 9a shows the HAADF-TEM image of the MXene-SiHfCN composite, where the majority of the matrix is amorphous (HRTEM in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11) compared to the crystalline Si

3N

4 features observed in the SiHfCN sample (

Figure 7). Unlike the SiHfCN sample that revealed slightly faceted Hf-rich particles, here fine particles and their accumulations are visible within the amorphous SiCNO matrix. In particular, Ti within the amorphous phase does not form distinct particles but rather appears as elongated line-like features. The EDS line profiles confirm these observations: line 1 (

Figure 9b) across the Ti-rich region and line 2 (

Figure 9c) across the Hf-rich area. Moreover, the EDS line profiles (

Figure 9b) reveal that the matrix has comparable concentrations of Si, N, and O, but lower C, indicating the presence of silicon oxynitride phases such as Si

2N

2O, in agreement with XRD analysis.

Figure 9d further supports these findings, showing the bright field (BF)-TEM and corresponding EDS elemental maps of the area in

Figure 9a. TEM/EDS point analysis on dark regions (Box 2 in

Figure 9d, and

Table 4) within the Hf-rich zones indicates carbon and higher oxygen content, suggesting Hf oxides and/or Hf oxycarbide. This also agrees with the Hf oxide observation from the XRD analysis, while the surrounding gray areas are relatively oxygen-deficient, suggesting the formation of Hf carbonitride. Analysis of the Ti-rich region (Box 1 in

Figure 9d, and

Table 4) shows that it is not purely TiC but contains small amounts of Si (3.63 at%) and O (5.73 at%), along with a dominant composition of Ti (32.49 at%), N (34.55 at%), and C (20.38 at%), suggesting TiC

0.63N

1.06O

0.18Si

0.99Hf

0.11 formation. Box 3 (in

Figure 9d, and

Table 4) indicates the SiCN region contains a significant amount of oxygen (24.05 at%), suggesting a SiOCN phase rather than SiCN, which is consistent with the SEM results. The overall composition of the amorphous matrix is close to SiC

0.64N

0.9O

0.78Hf

0.06Ti

0.01.

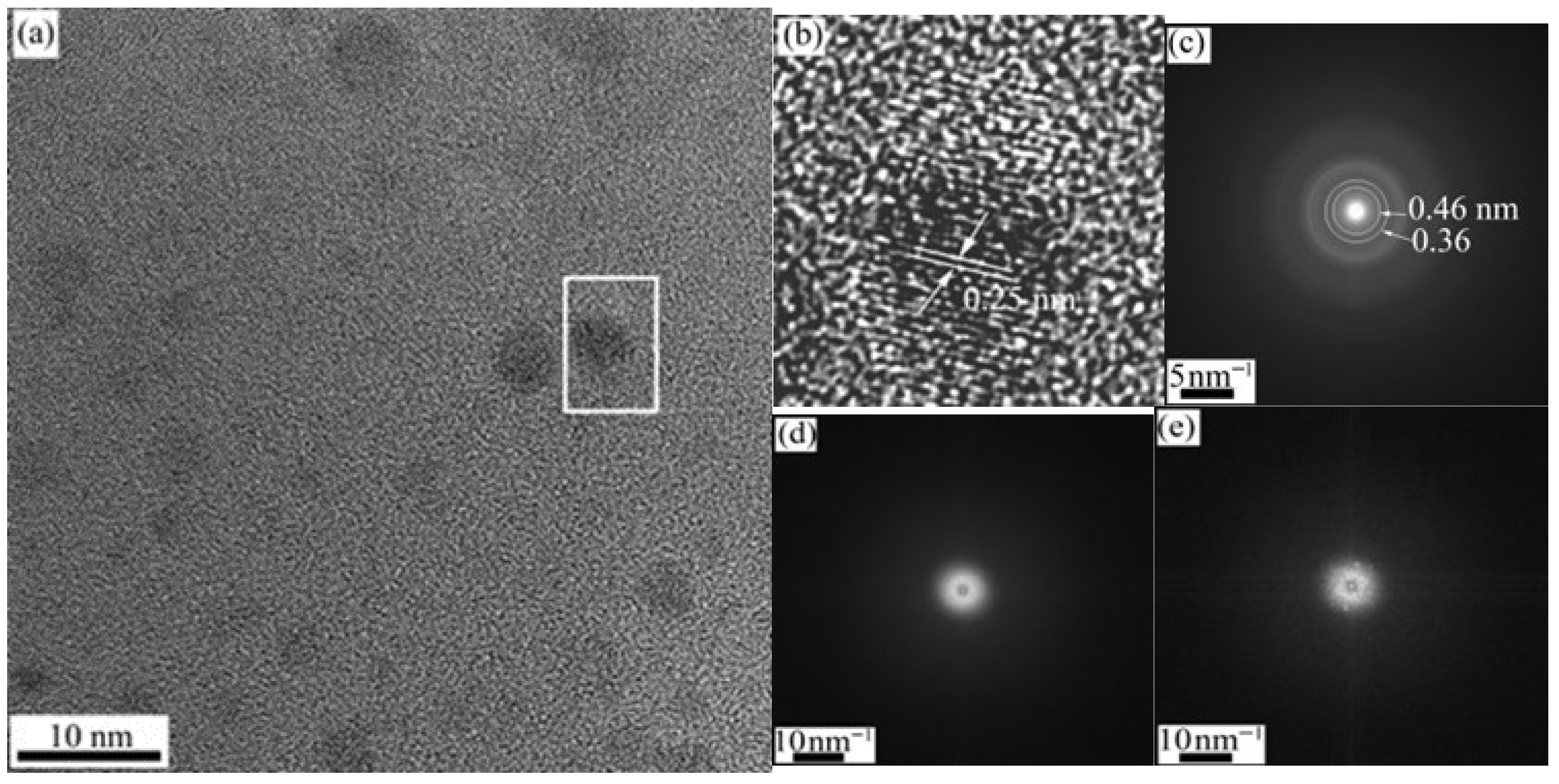

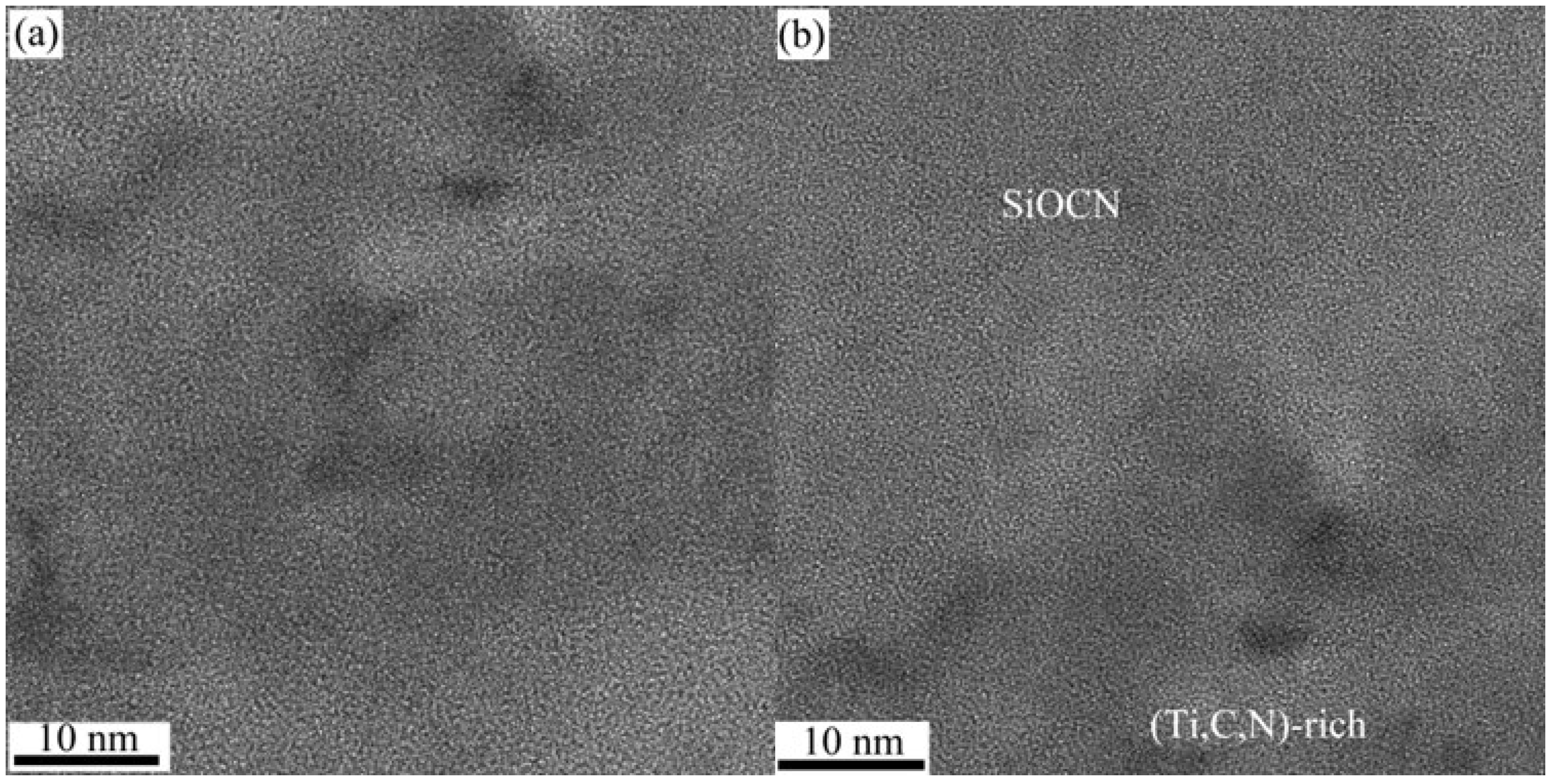

HRTEM results in

Figure 10 show the amorphous SiOCN matrix along with embedded Si

2ON

2 crystals (

Figure 10a), where a lattice spacing of 0.25 nm is identified (

Figure 10b). The corresponding SAED pattern (

Figure 10c) displays expanded first and second diffraction rings at 0.46 and 0.36 nm, respectively, compared to that of the SiHfCN sample (

Figure 8c). FFT analysis (

Figure 10d,e) distinguishes the coexistence of amorphous and crystalline regions. Additionally,

Figure 11 highlights the microstructure of the Ti-rich areas and their interface with the SiOCN matrix. The Ti-rich region is not fully crystalline, while the interface between the Ti-rich zone and the surrounding SiCNO shows good and stable interfacial bonding between the two phases.

4. Discussion

Functionalization of the MXene surface with AEAPTMS increases the hydrophobicity of Ti

3C

2T

x, enabling its dispersion in the single precursor for SiHfCN. The XPS results (

Figure 1) of functionalized MXene (F-MXene) confirm covalent bonding between silanol groups and surface hydroxyls on Ti

3C

2T

x. Previous studies [

27] also suggest that AEAPTMS can interact with Ti

3C

2T

x through covalent silanol bonding and electrostatic interactions via amine groups.

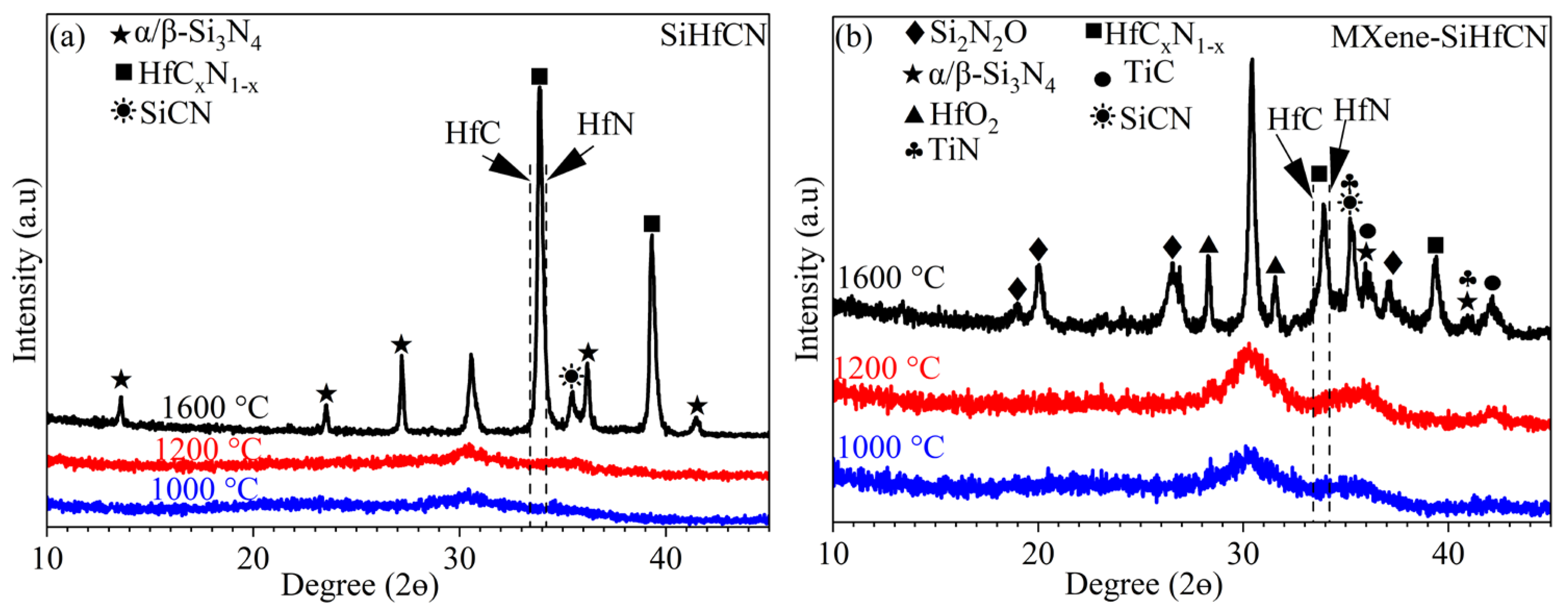

As shown in

Figure 3, the pyrolysis of both crosslinked samples for SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN results in an amorphous single phase at 1000 °C, with a ceramic yield of 87 wt.% (

Figure 2). This high yield is comparable to values reported for SiHfCN-based systems synthesized from similar precursors [

12,

15], confirming efficient cross-linking and limited mass loss during polymer-to-ceramic conversion. Subsequent heating to 1600 °C promotes ceramic crystallization (

Figure 3). The polymer-to-ceramic transformation process can be understood in terms of the following considerations. The high ceramic yield of 87 wt.% might be due to the presence of vinyl and Si-H units, which limit the evaporation of oligomers during pyrolysis [

43]. The major reactions in the thermal crosslinking of polysilazanes are hydrosilylation, dehydrocoupling, transamination, and vinyl group polymerization [

43,

44]. Hydrosilylation, which happens at low temperatures, might be faster in multi-element composite ceramics such as SiHfCN [

15,

43]. Transamination and dehydrogenation via Si-H/N-H or Si-H/Si-H groups occur at higher temperatures (300–450 °C). Dehydrogenation leads to Si-N and Si-Si bond formation and H

2 evolution. Transamination involves the rearrangement of the backbone of the Si-N bonds, which might cause the escape of structural units from the polysilazane network, resulting in large weight loss and nitrogen reduction from the final ceramic material [

43]. The negligible weight loss along with the exothermic peak at ~300 °C in

Figure 3 might be mainly due to dehydrogenation, while the larger weight loss at 300–500 °C suggests transamination reaction, in agreement with the SEM/EDS results (

Figure 5a,b and

Table 1) that show the nitrogen content is less than 6 at.%. Vinyl polymerization, which does not influence weight loss, might occur at this stage. At higher temperatures, the carbon chain formed due to cross-linking among the vinyl groups transformed into sp

2 carbon, while the number of Si-N bonds increases due to reactions between Si-H or Si-CH

3 and N-H groups. At the same time, SiN

4 might form by the replacement of methyl groups reacting with N-H groups. Furthermore, the elimination of Si-CH

3 and Si-H groups results in the release of methane. No mass loss is observed beyond 900 °C, suggesting that the ceramization process is complete.

For the SiHfCN sample, annealing at 1600 °C in N

2 resulted in HfC

xN

1−x formation within the crystalline α/β-Si

3N

4 and amorphous SiCN matrix (

Figure 3a,

Figure 5c,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). In the case of MXene-SiHfCN, the matrix was mainly amorphous, and different phases, including HfC

xN

1−x, Ti carbonitride, TiC, Hf-oxide/-oxycarbide, and Si

2N

2O, formed within the SiOCN matrix (

Figure 3b,

Figure 5d,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). Depending on the nitrogen pressure and temperature, the crystallization of amorphous SiCN might lead to the formation of α/β-Si

3N

4, α/β-SiC, and free carbon through the following reactions [

43]:

In the presence of oxygen in the SiCN system, reactions involving oxygen-containing species such as CO(g), SiO(g), and SiO

2 (s,l) must also be considered. This is due to the oxygen content in SiHfCN (originating from the sample preparation, see

Table 1) and in MXene-SiHfCN (introduced by the functionalized MXene, see

Table S1). The possible reactions are as follows [

43]:

SiC was not detected in either the SiHfCN or MXene-SiHfCN samples. Longitudinal cracks were observed in the SiHfCN samples, where Si

3N

4 formed adjacent to the cracks, while the regions farther away remained amorphous SiCN. After pyrolysis at 1200 °C, both SiHfCN and MXene-SiHfCN samples exhibited a similar oxygen content (~30 at.%) (

Figure 5a,b, and

Table 1). However, upon heat treatment up to 1600 °C, the oxygen content in the SiHfCN matrix decreased to ~10 at.%, whereas in the MXene-SiHfCN sample it remained close to ~30 at.% (

Figure 5c,d,

Figure 7 and

Figure 9,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4). The formation of Si

3N

4 near cracks in SiHfCN and Si

2ON

2 in MXene-SiHfCN may follow mechanisms similar to those reported for silicon nitridation [

45]. The relevant reactions are:

At 1600 °C (1873 K), the Gibbs free energy values indicate that SiO

2 formation is more favorable than Si

3N

4 formation (

for Equation (11) vs.

for Equation (12)). In SiHfCN, once SiO

2 forms, the oxygen partial pressure

decreases gradually because Si diffusion from the SiCN matrix becomes limited. This promotes the transition from passive to active oxidation, leading to the formation of volatile SiO gas between the matrix and the SiO

2 layer. When P

SiO exceeds a critical threshold, the SiO

2 layer cracks, allowing SiO(g) to escape. Meanwhile, residual Si from the SiCN matrix reacts with atmospheric N

2 to form Si

3N

4 near the cracks, as shown in

Figure 5c and

Figure 7a. In MXene-SiHfCN, the oxygen supply is higher due to the MXene contribution, favoring the formation of Si

2N

2O through Equation (13) as shown in

Figure 10. It is also possible that Si

2N

2O forms initially in SiHfCN as well. However, in this case, Si

2N

2O eventually transforms into Si

3N

4 via carbon-consuming reactions, as shown below:

This interpretation aligns with the Raman spectroscopy results (

Figure 4), which show that the D- and G-band intensities are much lower in SiHfCN compared to MXene-SiHfCN, indicating greater carbon consumption in the SiHfCN sample. While techniques such as TGA-MS/FTIR, FT-IR of ceramics, and solid-state MAS NMR would provide more detailed confirmation of the reaction pathways, the present interpretations are consistent with established mechanisms reported for analogous polymer-derived ceramics [

15,

43,

46] and are supported by the TGA, XRD, Raman, and SEM/EDS results in this study.

TEM results (

Figure 9) revealed that the matrix of MXene-SiHfCN consisted mainly of Si, C, N (~25 at.%), and O (~20 at.%), whereas the SiHfCN matrix (

Figure 7) contained primarily Si and C (~35 at.%) and was depleted in O and N (~10 at.%). This indicates that MXene-SiHfCN exhibits higher crystallization resistance, likely due to the formation of Si

2ON

2 within the amorphous matrix (

Figure 10), which acts as a diffusion barrier. It is generally proposed that in amorphous Si-based polymer-derived ceramics (SiC, SiCN, SiOC, and SiOCN), free carbon is the first phase to nucleate, followed by the crystallization of SiC [

10]. Kleebe et al. [

8] reported that the crystallization temperature of SiCN depends on the carbon distribution: structural rearrangement through incorporation of carbon into the silicon backbone lowers thermal stability, whereas a fine dispersion of carbon within the matrix enhances thermal stability. A recent study [

46] further demonstrated that the thermal stability of amorphous oxygen-containing silicon nitride increases due to the formation of Si

2ON

2. The authors suggest that the incorporation of O atoms into the amorphous SiN

x network results in the formation of SiO

xN

y through the replacement of nitrogen atoms in SiN

4 units by oxygen. Their investigation of nucleation and crystallization kinetics also revealed a lower energy barrier for the formation of SiO

xN

y compared to that for α-Si

3N

4. These findings are consistent with the HRTEM results (

Figure 8 and

Figure 10), which showed diffraction rings corresponding to SiN

4 (0.40 nm) and SiC

xN

y (0.30 nm) in the SiHfCN sample, shifting to 0.46 nm and 0.36 nm, respectively, in the MXene-SiHfCN sample. This shift suggests oxygen incorporation into the amorphous network.