Additive Manufacturing with Clay and Ceramics: Materials, Modeling, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- Material and rheological behavior: including subjects such as fresh-state rheology, structuration, shrinkage, and interlayer bonding, among others.

- (ii)

- Numerical modeling approaches: including finite element methods (FEM) for strength and deformation, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for flow and pressure fields, and multiphysics coupling.

- (iii)

- Parametric and computational design strategies: rule-based modeling, toolpath-aware logic, performance-driven, and nature-inspired structures.

2. Clay and Ceramic-Based Materials for Additive Manufacturing

2.1. Clay Materials and Their Role in AM

2.2. Geopolymers and Ceramic Pastes

2.3. Material Parameters Governing Fresh-State and Early-Age Behavior

2.4. Current Uses and Practical Challenges in Paste-Based AM

3. AM Technologies for Clay and Ceramic Systems

3.1. Extrusion-Based AM for Clay and Ceramics

3.1.1. Direct Ink Writing (DIW)

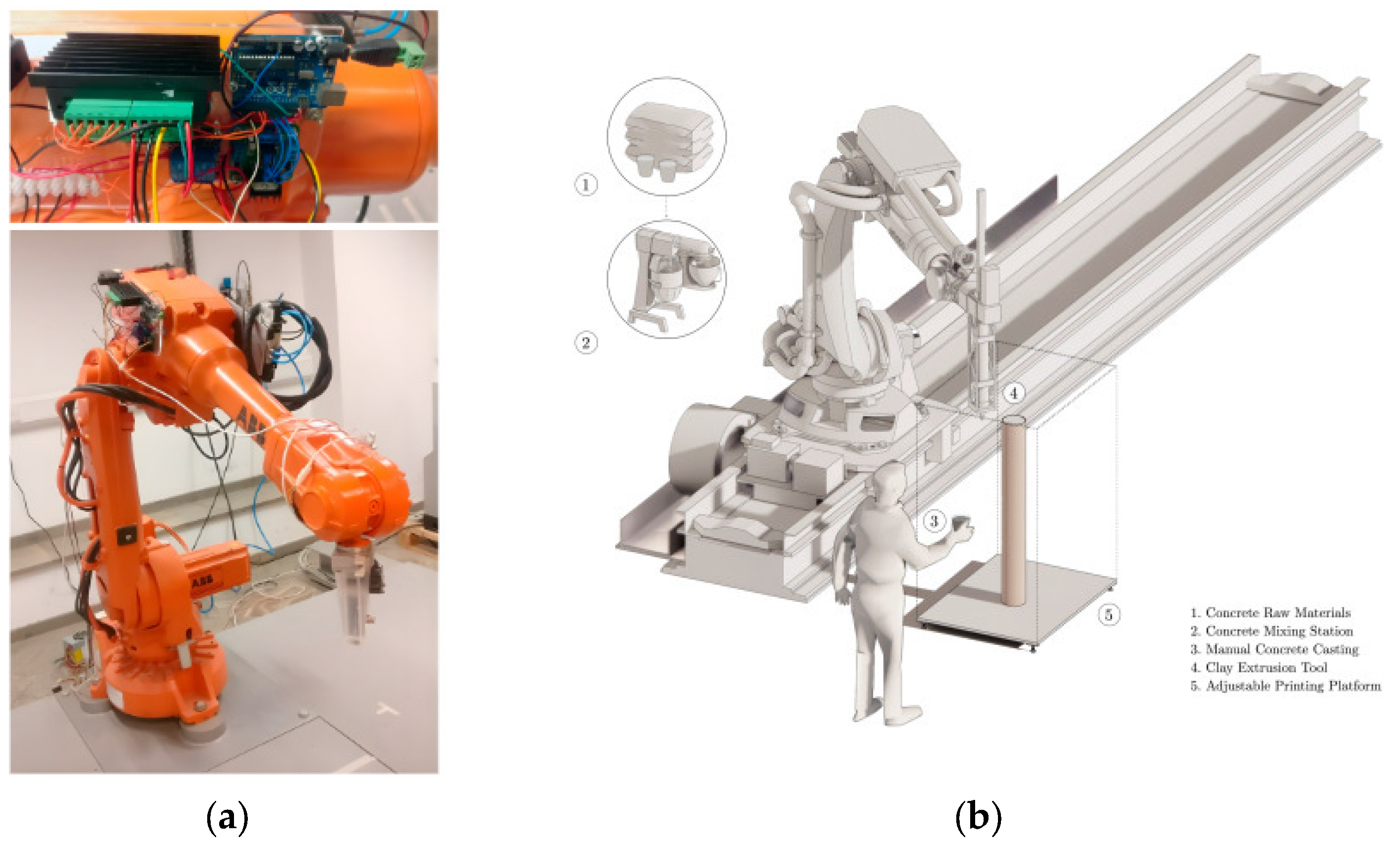

3.1.2. Large-Scale Robotic Extrusion

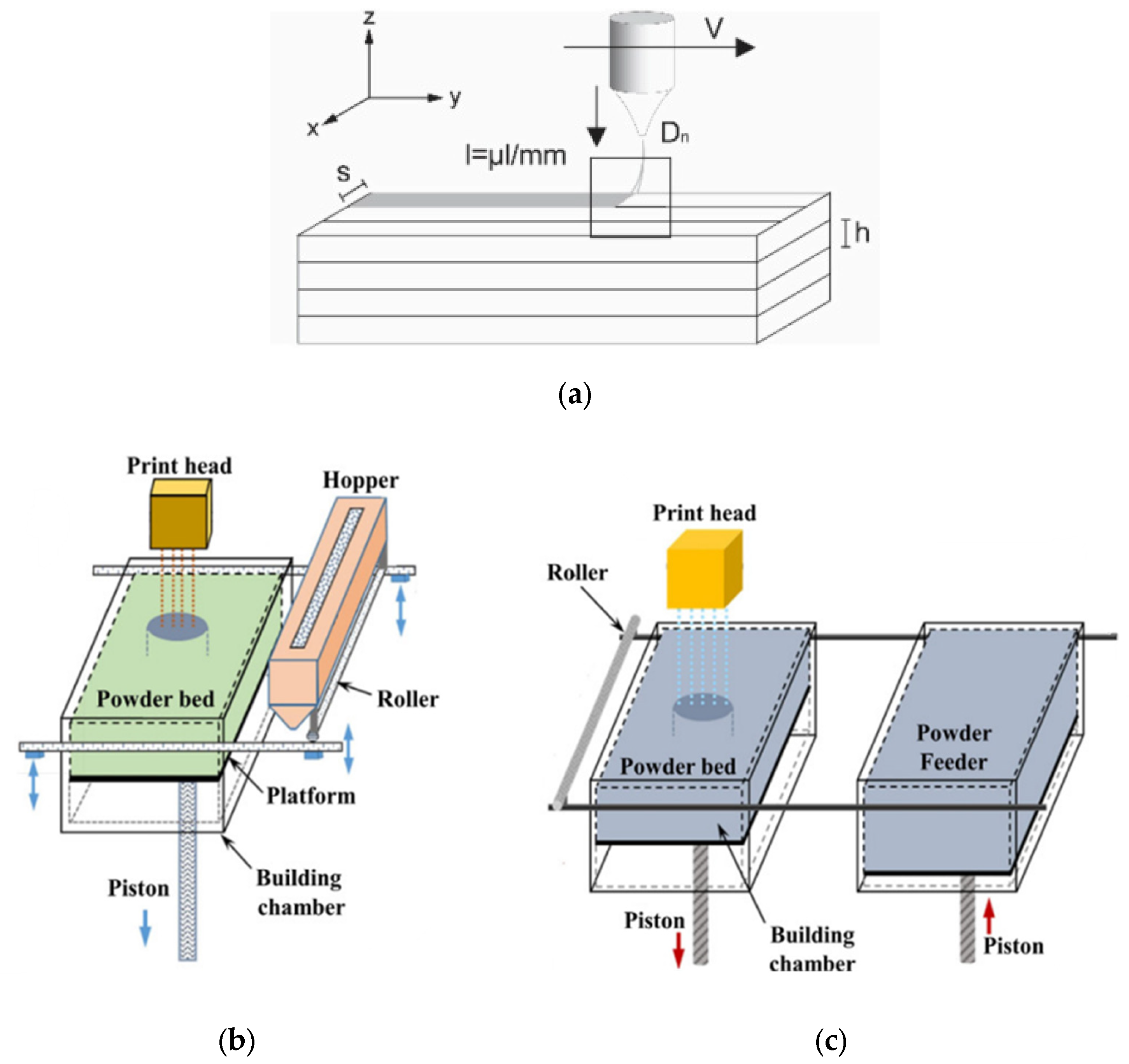

3.2. Binder Jetting

4. Mathematical Modeling of Clay and Ceramic-Based Additive Manufacturing

4.1. Rheological Foundations for Clay and Ceramic AM

4.2. Constitutive Models for Clay and Ceramic Pastes in AM

4.3. Thixotropic and Time-Dependent Modeling Approaches

4.4. Multiphysics Modeling in Clay-Based AM

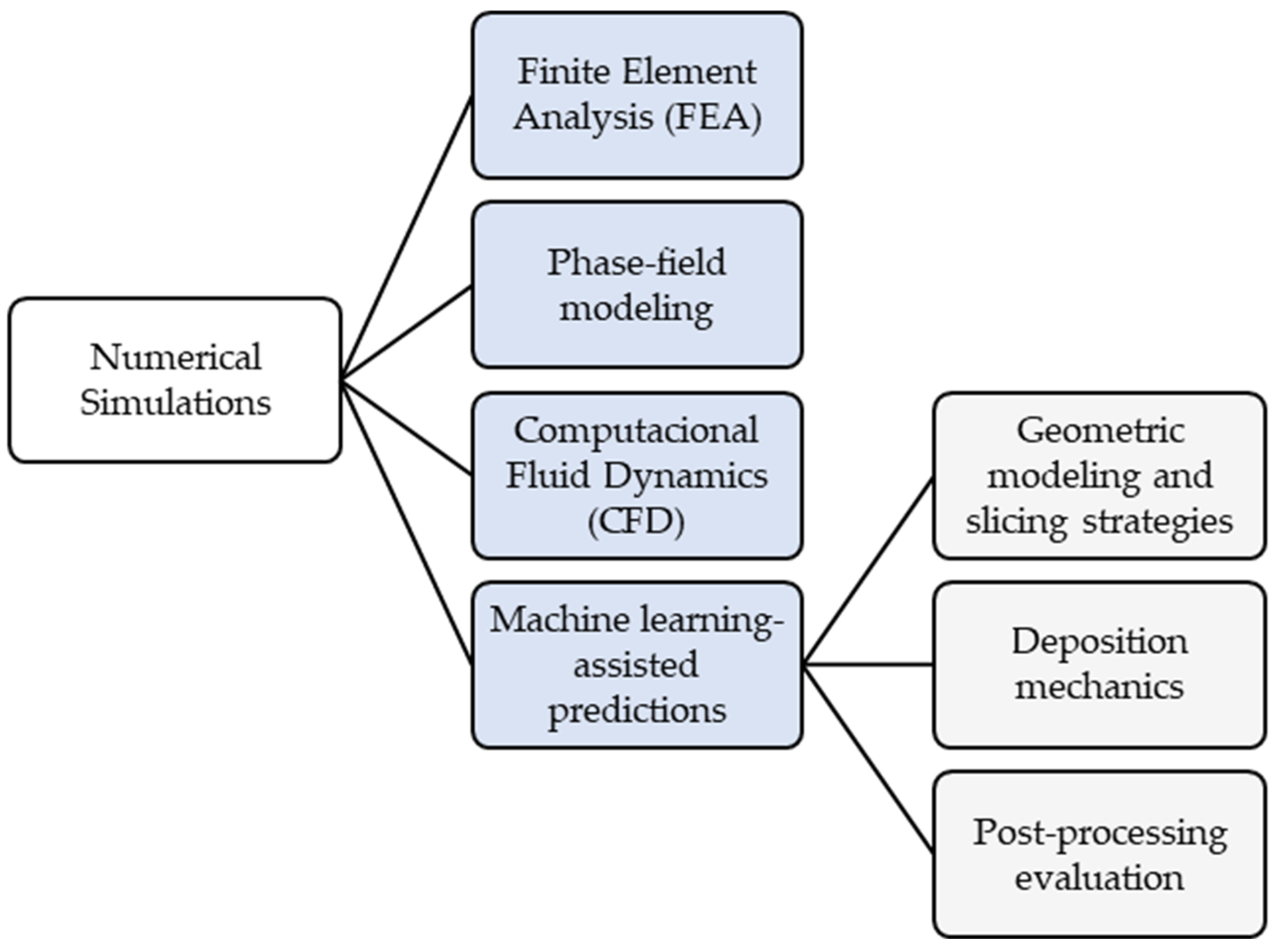

5. Computational Modeling for Clay-Based Additive Manufacturing

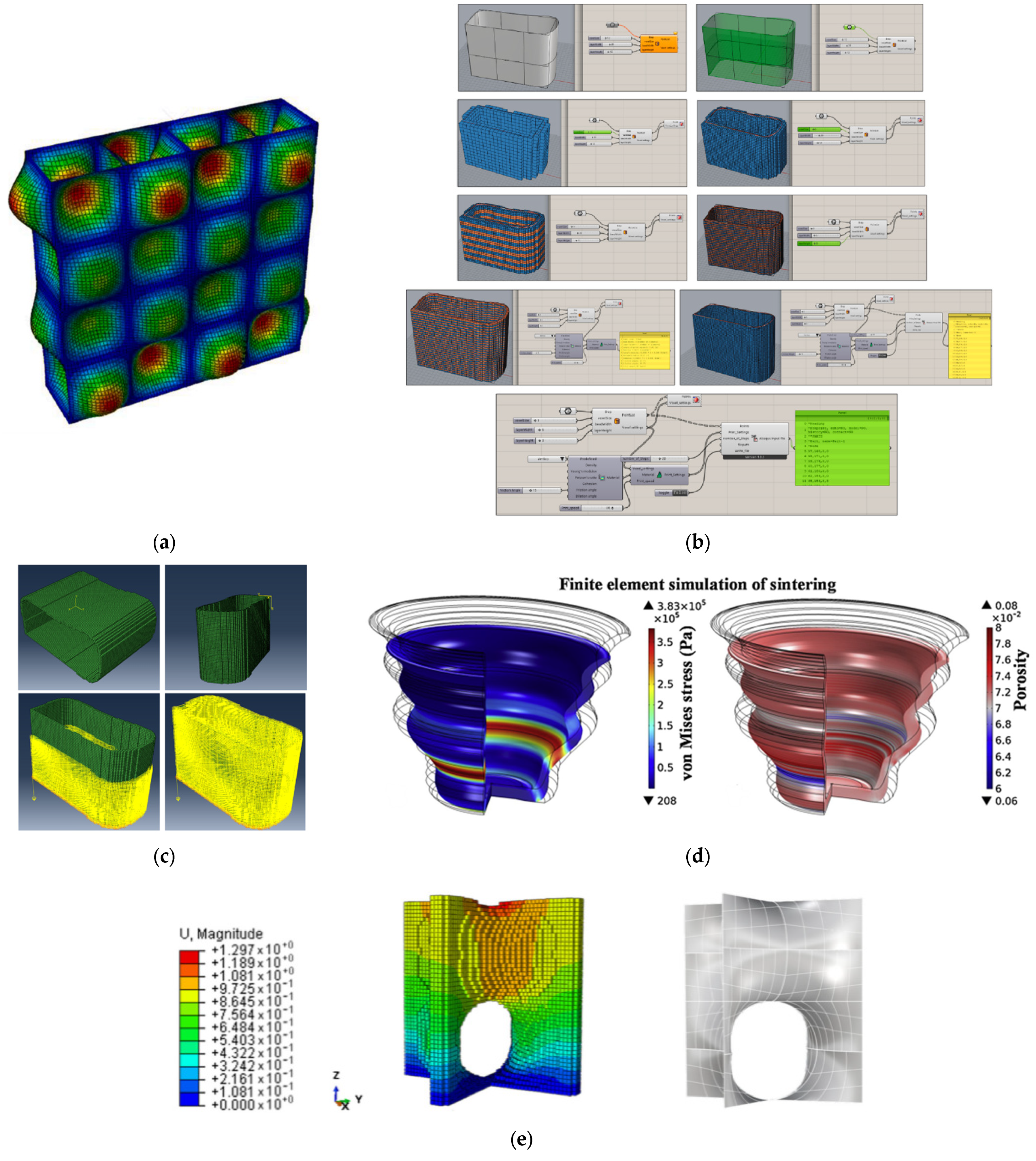

5.1. Finite Element Analysis (FEA): From Fresh-State to Structural Behavior

5.1.1. Background and the Role of FEM

5.1.2. Advances and Challenges in FEM for Clay and Ceramic Extrusion-Based AM

5.2. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

5.2.1. Role of CFD in Extrusion-Based AM

5.2.2. Current Applications in Clay and Ceramic AM

5.2.3. Insights from Other Extrusion Systems

5.2.4. Coupling CFD with Rheology and Drying Physics

5.3. Geometric and Parametric Modeling

5.3.1. Rule-Based and Parametric Workflows

5.3.2. Material-Driven and Bioinspired Design

5.3.3. Process-Aware and Toolpath-Driven Design

5.3.4. Performance- and Sustainability-Oriented Parametric Workflows

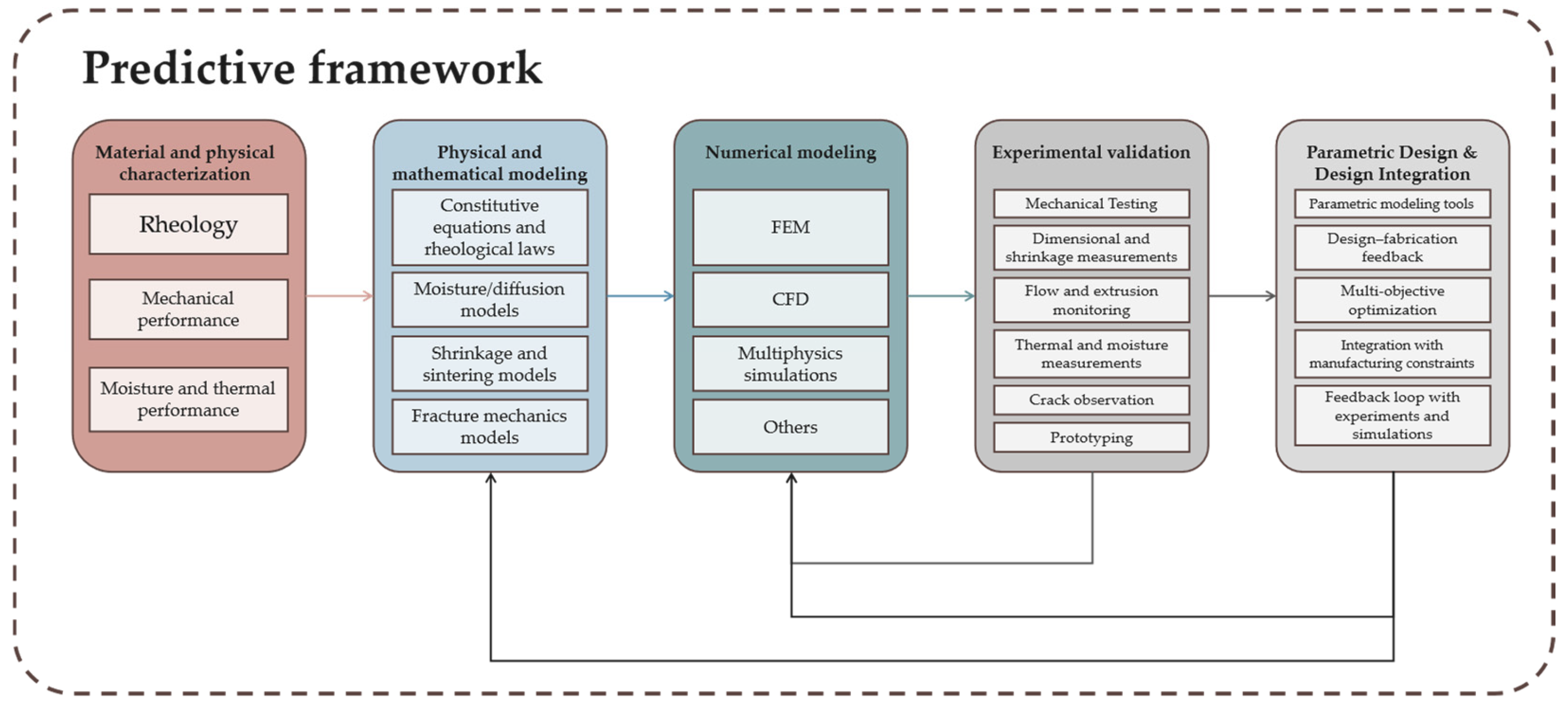

6. Numerical Modeling in Clay-Based Additive Manufacturing: Toward Predictive Frameworks

6.1. Mechanical Behavior Simulations

6.2. Predicting Deformation and Shrinkage

6.3. Modeling Cracking and Failure

6.4. Drying and Curing Simulations (Time-Dependent Behavior)

6.5. Thermo-Mechanical Sintering Simulations

6.6. Multiphysics Modeling

7. Conclusions

- Standardized rheological protocols and shared benchmark datasets.

- Multiscale modeling frameworks linking nozzle-scale flow to drying, sintering, and structural performance.

- Robust experimental validation pipelines pairing computation with controlled testing.

- Integration of sustainability and circularity metrics into design and fabrication workflows.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdalla, H.; Fattah, K.P.; Abdallah, M.; Tamimi, A.K. Environmental Footprint and Economics of a Full-scale 3D-printed House. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinian, S.M.; Sabouri, A.G.A.; Carmichael, D.G. Sustainable Production of Buildings Based on Iranian Vernacular Patterns: A Water Footprint Analysis. Build. Environ. 2023, 242, 110605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.S.; Shema, A.I.; Ibrahim, A.U.; Abuhussain, M.A.; Abdulmalik, H.; Dodo, Y.A.; Atakara, C. Assimilation of 3D Printing, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Internet of Things (IoT) for the Construction of Eco-Friendly Intelligent Homes: An Explorative Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Environment Programme, Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction. Not Just Another Brick in the Wall: The Solutions Exist—Scaling Them Will Build on Progress and Cut Emissions Fast. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2024/2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/global-status-report-buildings-and-construction-20242025 (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- KC, A.K.; Mainali, B.; Ghimire, A.; Adhikari, B.; Lohani, S.P.; Baral, B. Role of Vernacular Architecture in Enhancing the Environmental Sustainability of the Building Sector. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 86, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, S.; Li, D.; Thurairajah, N. Uncertainties in Whole-Building Life Cycle Assessment: A Systematic Review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyawali, B.; Haghnazar, R.; Akula, P.; Alba, K.; Nasir, V. A Review on 3D Printing with Clay and Sawdust/Natural Fibers: Printability, Rheology, Properties, and Applications. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Teng, F.; Yu, J.; Yu, S.; Du, H.; Zhang, D.; Ruan, S.; Weng, Y. Development of 3D Printable Engineered Cementitious Composites with Incineration Bottom Ash (IBA) for Sustainable and Digital Construction. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyildizi, H.; Seloglu, M.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Abdul Razak, R.; Mydin, M.A.O. The Rheological and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Geopolymers: A Review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshram, R.B.; Mohapatra, A.; Malakar, S.; Gupta, P.K.; Sahoo, D.P.; Nath, S.K.; Alex, T.C.; Kumar, S. Environmental Impact Analysis of Geopolymer Based Red Mud Paving Blocks. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupa, M.; Rao, V.M.; Sethy, K. Revealing the Potential of Red Mud and Recycled Water: A Review of Geopolymer Concrete. Int. J. Eng. 2025, 38, 1019–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balizi, B.; Karim Serroukh, H.; Aziz, A.; Benaicha, M.; Bellil, A.; El Khadiri, A.; Laaroussi, N. Thermo-Mechanical Characterization and Numerical Modeling of Lightweight Mortars Incorporating Natural Pozzolan and Expanded Clay. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappai, M.; Pia, G. Sustainable Earthen Plasters: Surface Resistance Enhancement via Thermal Treatments. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; El Attar, M.E.; Zouli, N.; Abutaleb, A.; Maafa, I.M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Yousef, A.; Ragab, A. Improving the Thermal Performance and Energy Efficiency of Buildings by Incorporating Biomass Waste into Clay Bricks. Materials 2023, 16, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wi, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, S. Biochar-Red Clay Composites for Energy Efficiency as Eco-Friendly Building Materials: Thermal and Mechanical Performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 373, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, A.; Rangeard, D.; Courteille, E. 3D Printing of Earth-Based Materials: Processing Aspects. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 172, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhao, H.; Liu, W.; Jiang, J.; Lu, L. Shell Thickening for Extrusion-Based Ceramics Printing. Comput. Graph. 2021, 97, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asapu, S.; Ravi Kumar, Y. Design for Additive Manufacturing (DfAM): A Comprehensive Review with Case Study Insights. JOM-J. Miner. Met. Mater. Soc. 2025, 77, 3931–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, N.; Gaspar, M.B.; Pascoal-Faria, P. Computer-Aided Optimization in Additive Manufacturing: Processing Parameters and 3D Scaffold Reconstruction. In Proceedings of the Central European Symposium on Thermophysics (CEST), Banska Bystrica, Slovakia, 16–18 October 2019; Volume 2116. [Google Scholar]

- Bahoria, B.V.; Bhagat, R.M.; Pande, P.B.; Raut, J.M.; Dhengare, S.W.; Mankar, S.H.; Vairagade, V.S.; Shelare, S.D. Design Optimization of 3D Printed Concrete Elements Considering Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Costing. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2024, 19, 2183–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Kong, J.H.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, S. Recent Advances of Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing Industrial Sectors: A Review. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 23, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Jough, F.K.G.; Dastres, R.; Arezoo, B. Additive Manufacturing Modification by Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning: A Review. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2025, 4, 200198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnabi, S.; Moslemy, N.; Taghvaei, H.; Zia, A.W.; Askarinejad, S.; Shalchy, F. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Data-Centric Additive Manufacturing Processes for Biomedical Applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 166, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, G.X.; Chen, C.-T.; Richmond, D.J.; Buehler, M.J. Bioinspired Hierarchical Composite Design Using Machine Learning: Simulation, Additive Manufacturing, and Experiment. Mater. Horiz. 2018, 5, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzhirov, A.V.; Lychev, S. Mathematical Modeling of Additive Manufacturing Technologies. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, London, UK, 2–4 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Motamedi, M.; Mesnil, R.; Tang, A.-M.; Pereira, J.-M.; Baverel, O. Structural Build-up of 3D Printed Earth by Drying. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 95, 104492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.M.; Campoli, G.; Amin Yavari, S.; Sajadi, B.; Wauthle, R.; Schrooten, J.; Weinans, H.; Zadpoor, A.A. Mechanical Behavior of Regular Open-Cell Porous Biomaterials Made of Diamond Lattice Unit Cells. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 34, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragaglia, M.; Cecchini, F.; Paleari, L.; Ferrara, M.; Rinaldi, M.; Nanni, F. Modeling the Fracture Behavior of 3D-Printed PLA as a Laminate Composite: Influence of Printing Parameters on Failure and Mechanical Properties. Compos. Struct. 2023, 322, 117379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbairn, E.M.R.; Santos, L.D.F.; Farias, M.B.; Reales, O.A.M. Numerical Modeling of New Conceptions of 3D Printed Concrete Structures for Pumped Storage Hydropower. In Proceedings of the RILEM International Conference on Numerical Modeling Strategies for Sustainable Concrete Structures, Marseille, France, 4–6 July 2022; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 38, pp. 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Tay, Y.W.D.; Weng, Y.; Wong, T.N.; Tan, M.J. Rotation Nozzle and Numerical Simulation of Mass Distribution at Corners in 3D Cementitious Material Printing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Singh, R.; Sharma, S. Effect of Processing Parameters on Mechanical Properties of FDM Filament Prepared on Single Screw Extruder. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ketan, O.; Rowshan, R.; Abu Al-Rub, R.K. Topology-Mechanical Property Relationship of 3D Printed Strut, Skeletal, and Sheet Based Periodic Metallic Cellular Materials. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 19, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M.; Zinovieva, O.; Ferrari, F.; Ayas, C.; Langelaar, M.; Spangenberg, J.; Salajeghe, R.; Poulios, K.; Mohanty, S.; Sigmund, O.; et al. Holistic Computational Design within Additive Manufacturing through Topology Optimization Combined with Multiphysics Multi-Scale Materials and Process Modelling. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 138, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, M.; Tran, P.; Xia, L.; Ma, G.; Xie, Y.M. Topology Optimization for 3D Concrete Printing with Various Manufacturing Constraints. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 57, 102982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, N.; Wang, Q. Topology Optimization Design of Porous Infill Structure with Thermo-Mechanical Buckling Criteria. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2022, 18, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, R.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Lietaert, K.; Pouran, B.; Li, Y.; Weinans, H.; Rans, C.D.; Zadpoor, A.A. Isolated and Modulated Effects of Topology and Material Type on the Mechanical Properties of Additively Manufactured Porous Biomaterials. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 79, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shubbar, A.A.; Sadique, M.; Kot, P.; Atherton, W. Future of Clay-Based Construction Materials—A Review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 210, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscitti, A.; Tapia, C.; Rendtorff, N.M. A Review on Additive Manufacturing of Ceramic Materials Based on Extrusion Processes of Clay Pastes. Ceramica 2020, 66, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossin, D.; Montón, A.; Navarrete-Segado, P.; Özmen, E.; Urruth, G.; Maury, F.; Maury, D.; Frances, C.; Tourbin, M.; Lenormand, P.; et al. A Review of Additive Manufacturing of Ceramics by Powder Bed Selective Laser Processing (Sintering/Melting): Calcium Phosphate, Silicon Carbide, Zirconia, Alumina, and Their Composites. Open Ceram. 2021, 5, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.; Jabi, W.; Soebarto, V.; Xie, Y.M. Digital Manufacturing for Earth Construction: A Critical Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Guo, C.; Sun, B.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Li, A. The State of the Art in Digital Construction of Clay Buildings: Reviews of Existing Practices and Recommendations for Future Development. Buildings 2023, 13, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velde, B. Uses of Clays. In Introduction to Clay Minerals: Chemistry, Origins, Uses and Environmental Significance; Velde, B., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 164–176. ISBN 978-94-011-2368-6. [Google Scholar]

- Worasith, N.; Goodman, B.A. Clay Mineral Products for Improving Environmental Quality. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 242, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, H.H. Applied Clay Mineralogy: Occurrences, Processing and Applications of Kaolins, Bentonites, Palygorskitesepiolite, and Common Clays; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; ISBN 978-0-08-046787-0. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.B. Clays and Clay Minerals in the Construction Industry. Minerals 2022, 12, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Noaimat, Y.A.; Chougan, M.; Al-kheetan, M.J.; Al-Mandhari, O.; Al-Saidi, W.; Al-Maqbali, M.; Al-Hosni, H.; Ghaffar, S.H. 3D Printing of Limestone-Calcined Clay Cement: A Review of Its Potential Implementation in the Construction Industry. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, S.; Kamravafar, R.; Li, Y.; Mata-Falcón, J.; Adel, A. Leveraging Clay Formwork 3D Printing for Reinforced Concrete Construction. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2024, 19, e2367735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega Del Rosario, M.D.L.A.; Medina, M.; Duque, R.; Ortega, A.A.J.; Castillero, L. Advancing Sustainable Construction: Insights into Clay-Based Additive Manufacturing for Architecture, Engineering, and Construction. In Developments in Clay Science and Construction Techniques; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2024; ISBN 978-1-83769-606-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Fan, W.; Li, Q. Application of Nanofibrous Clay Minerals in Water-Based Drilling Fluids: Principles, Methods, and Challenges. Minerals 2024, 14, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratkievicius, L.A.; Cunha Filho, F.J.V.D.; Barros Neto, E.L.D.; Santanna, V.C. Modification of Bentonite Clay by a Cationic Surfactant to Be Used as a Viscosity Enhancer in Vegetable-Oil-Based Drilling Fluid. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 135, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falode, O.A.; Ehinola, O.A.; Nebeife, P.C. Evaluation of Local Bentonitic Clay as Oil Well Drilling Fluids in Nigeria. Appl. Clay Sci. 2008, 39, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candeias, C.; Santos, I.; Rocha, F. Characterization and Suitability for Ceramics Production of Clays from Bustos, Portugal. Minerals 2025, 15, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk, M.; Marzec, J.; Leśniewski, T.; Krawczyk, J.; Madej, Ł.; Perzyński, K. Analysis of the Wear of Forming Tools in the Process of Extruding Ceramic Bands Using Selected Research Methods for Evaluating Operational Durability. Materials 2025, 18, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrygiannis, I.; Karalis, K.; Tzampoglou, P. Enhancing the Thermal Insulation Properties of Clay Materials Using Coffee Grounds and Expanded Perlite Waste: A Sustainable Approach to Masonry Applications. Ceramics 2025, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos da Silva, A.M.; Delgado, J.M.P.Q.; Guimarães, A.S.; Barbosa de Lima, W.M.P.; Soares Gomez, R.; Pereira de Farias, R.; Santana de Lima, E.; Barbosa de Lima, A.G. Industrial Ceramic Blocks for Buildings: Clay Characterization and Drying Experimental Study. Energies 2020, 13, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalendova, A.; Kupkova, J.; Urbaskova, M.; Merinska, D. Applications of Clays in Nanocomposites and Ceramics. Minerals 2024, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Wang, C.; Dong, Z.; Yao, J.; Dong, F.; Dai, X. Fabrication of Polylactic Acid Bilayer Composite Films Using Polyvinyl Alcohol Based Coatings Containing Functionalized Carbon Dots and Layered Clay for Active Food Packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, M.I.; Pozo, M. Clay and Non-Clay Minerals in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Part I. Excipients and Medical Applications. Appl. Clay Sci. 2009, 46, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamoudi, S.; Manai, J.; Kanhounnon, W.G.; Mendoza-Castillo, D.I.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Foucaud, Y.; Christidis, G.E.; Srasra, E.; Badawi, M. Assessment of Tunisian Clays for Their Potential Application as Excipient in Pharmaceutical Preparations: 2-Amino-5-Chlorobenzophenone Adsorption. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 269, 107760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, I.M.; de Melo Barbosa, R.; García-Villén, F.; Ramírez, I.M.; Massaro, M.; Riela, S.; López-Galindo, A.; Viseras, C.; Sánchez-Espejo, R. Technological Study of Kaolinitic Clays from Fms. Escucha and Utrillas to Be Used in Dermo-Pharmaceutical Products. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 255, 107422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ami, I.J.; Nasrin, S.; Akter, F.; Halder, M. Potential Agricultural Waste Management Modes to Enhance Carbon Sequestration and Aggregation in a Clay Soil. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzaghi, K. Principles of Soil Mechanics: A Summary of Experimental Studies of Clay and Sand; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.K.; Soga, K.; O’Sullivan, C. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-1-119-83231-7. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Ghayoomi, M.; Newell, P. Effects of 3D Printing on Clay Permeability and Strength. Transp. Porous Med. 2023, 148, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Tong, H.; Yuan, J.; Fang, Y.; Gu, R. Permeability Prediction Model Modified on Kozeny-Carman for Building Foundation of Clay Soil. Buildings 2022, 12, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sutejo, I.A.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.-J.; Park, H.; Yun, H. Three-Dimensional Complex Construct Fabrication of Illite by Digital Light Processing-Based Additive Manufacturing Technology. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 3827–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Shimai, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, S. A Novel Experimental Approach to Quantitatively Evaluate the Printability of Inks in 3D Printing Using Two Criteria. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, S.A.E.; Jandet, L.; Burr, A. 3D-Extrusion Manufacturing of a Kaolinite Dough Taken in Its Pristine State. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 582885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daguano, J.K.M.B.; Giora, F.C.; Santos, K.F.; Pereira, A.B.G.C.; Souza, M.T.; Dávila, J.L.; Rodas, A.C.D.; Santos, C.; Silva, J.V.L. Shear-Thinning Sacrificial Ink for Fabrication of Biosilicate® Osteoconductive Scaffolds by Material Extrusion 3D Printing. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 287, 126286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Gupta, S. 3D Printable Earth-Based Alkali-Activated Materials: Role of Mix Design and Clay-Rich Soil. In Bio-Based Building Materials: Proceedings of ICBBM 2023; Amziane, S., Merta, I., Page, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, Y.K.; Estévez, A.T. 3D-Printed Biodigital Clay Bricks. Biomimetics 2021, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Camargo, I.L.; Morais, M.M.; Fortulan, C.A.; Branciforti, M.C. A Review on the Rheological Behavior and Formulations of Ceramic Suspensions for Vat Photopolymerization. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 11906–11921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, H.; Dong, D.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, H.; Guo, Y.; Liu, H.; Fan, G.; et al. Enhanced Comprehensive Properties of Stereolithography 3D Printed Alumina Ceramic Cores with High Porosities by a Powder Gradation Design. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 131, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Manivannan, E.; Rizwan, M.; Gopan, G.; Mani, M.; Kannan, S. 3D Printed Polylactide-Based Zirconia-Toughened Alumina Composites: Fabrication, Mechanical, and in vitro Evaluation. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2024, 21, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qutaifi, S.; Nazari, A.; Bagheri, A. Mechanical Properties of Layered Geopolymer Structures Applicable in Concrete 3D-Printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, H.; Li, H.; Jin, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, D.; Liang, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L. 3D-Printed SiC Lattices Integrated with Lightweight Quartz Fiber/Silica Aerogel Sandwich Structure for Thermal Protection System. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 454, 140408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, A.; Rangeard, D.; Pierre, A. Structural Built-up of Cement-Based Materials Used for 3D-Printing Extrusion Techniques. Mater. Struct. 2016, 49, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelo, C.F.; Colorado, H.A. 3D Printing of Kaolinite Clay with Small Additions of Lime, Fly Ash and Talc Ceramic Powders. Process. Appl. Ceram. 2019, 13, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, T.J.; McCaw, J.C.S.; Son, S.F.; Gunduz, I.E.; Rhoads, J.F. Characterizing the Vibration-Assisted Printing of High Viscosity Clay Material. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, V.; Balasubramaniam, B.; Yeh, L.-H.; Li, B. Recent Advances in In Situ 3D Surface Topographical Monitoring for Additive Manufacturing Processes. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2025, 9, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriat, A.; Bach, J.S.; Gunduz, I.; Rhoads, J.F.; Son, S.F. Comparing the Capabilities of Vibration-Assisted Printing (VAP) and Direct-Write Additive Manufacturing Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 8231–8241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitayachaval, P.; Baothong, T. An Effect of Screw Extrusion Parameters on a Pottery Model Forming by A Clay Printing Machine. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2022, 14, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wi, K.; Suresh, V.; Wang, K.; Li, B.; Qin, H. Quantifying Quality of 3D Printed Clay Objects Using a 3D Structured Light Scanning System. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 100987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, A.; Aşut, S.; van der Spoel, W. An Integrated Workflow for Designing and Fabricating Multi-Functional Building Components through Additive Manufacturing with Clay. Buildings 2023, 13, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Pan, Y.-T. Three-Dimensional Printing of Large Ceramic Products and Process Simulation. Materials 2023, 16, 3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, O.; Bentur, A.; Larianovsky, P.; Sprecher, A. From Soil to Printed Structures: A Systematic Approach to Designing Clay-Based Materials for 3D Printing in Construction and Architecture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, K.; Jiang, X.; Singh, A.A.; Li, B.; Qin, H. Effects of Nozzle Geometries on 3D Printing of Clay Constructs: Quantifying Contour Deviation and Mechanical Properties. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 48, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.S.L.; Pennings, R.M.; Edwards, L.; Franks, G.V. 3D Printing of Clay for Decorative Architectural Applications: Effect of Solids Volume Fraction on Rheology and Printability. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Madrid, J.; Sotorrío Ortega, G.; Gorostiza Carabaño, J.; Olsson, N.O.E.; Tenorio Ríos, J.A. 3D Claying: 3D Printing and Recycling Clay. Crystals 2023, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, F. A 3D Printed Pop-Up Store by WASP for Dior. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/en/3d-printed-pop-up-store-wasp-dior/ (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Moretti, F. 3D Printed Houses for a Renewed Balance Between Environment and Technology. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/en/3d-printed-houses-for-a-renewed-balance-between-environment-and-technology/ (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Moretti, F. 3D Print Coral Reef. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/en/3d-print-coral-reef/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Chiusoli, A. 3D Printed House TECLA—Eco-Housing. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/en/3d-printed-house-tecla/ (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Chiusoli, A. The First 3D Printed House with Earth|Gaia. Available online: https://www.3dwasp.com/en/3d-printed-house-gaia/ (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC) Projects; Development Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC). Projects Repository. 2024. Available online: https://iaac.net/projects-development/ (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Caldwell, B. Printing with Wet Clay: Architecture Team Produces Showpiece Privacy Wall for High-Rise Office Using 3D-Printed Bricks. Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/news/printing-wet-clay (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Abedi, M.; Waris, M.B.; Al-Alawi, M.K.; Al-Jabri, K.S.; Al-Saidy, A.H. From Local Earth to Modern Structures: A Critical Review of 3D Printed Cement Composites for Sustainable and Efficient Construction. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 100, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

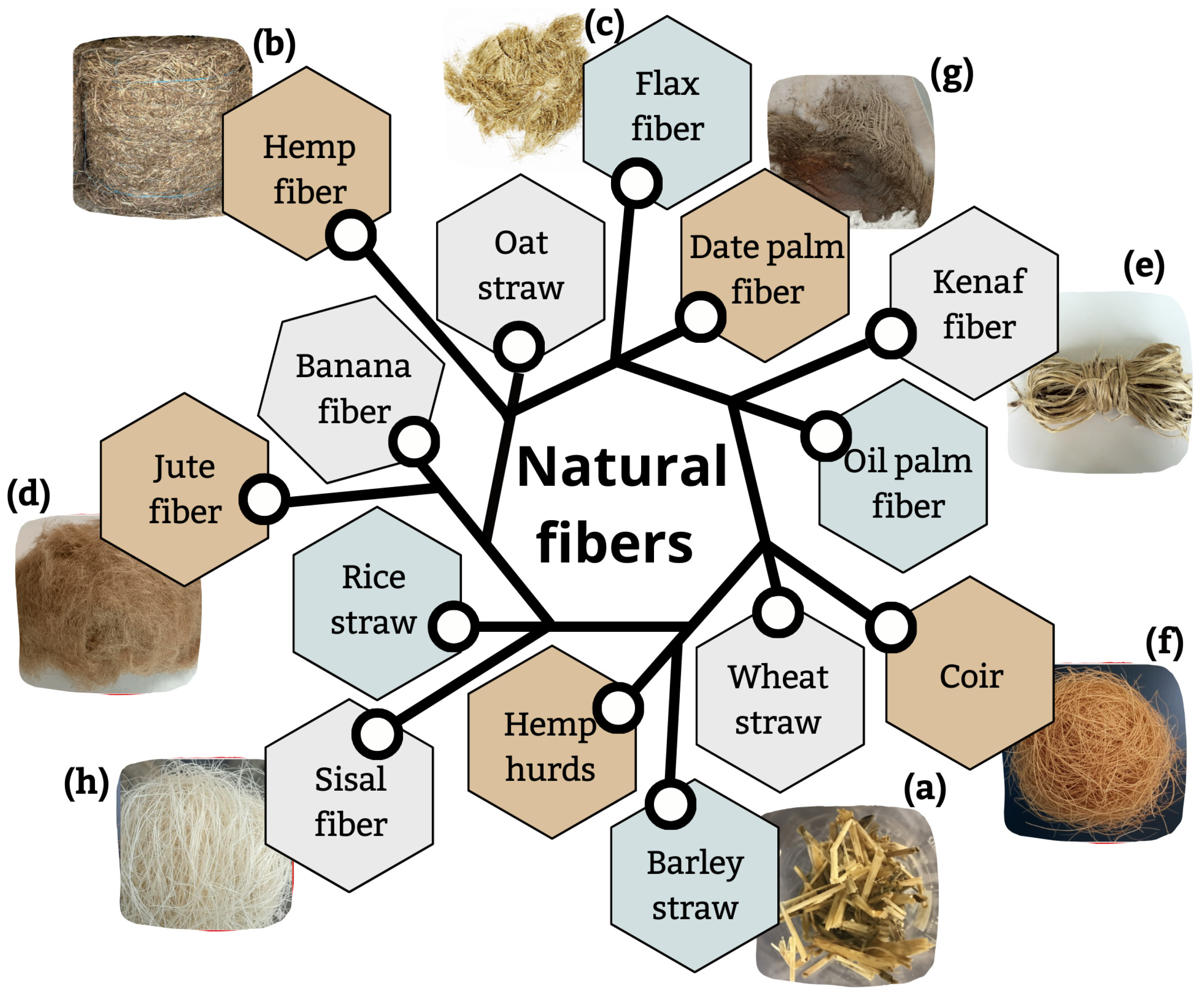

- Carcassi, O.B.; Maierdan, Y.; Akemah, T.; Kawashima, S.; Ben-Alon, L. Maximizing Fiber Content in 3D-Printed Earth Materials: Printability, Mechanical, Thermal and Environmental Assessments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 135891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curth, A.; Alvarez, E.G.; Sass, L.; Norford, L.; Mueller, C. Additive Energy: 3D Printing Thermally Performative Building Elements with Low Carbon Earthen Materials. In 3D Printing for Construction in the Transformation of the Building Industry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 28–45. ISBN 978-104015512-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Lao, C.; Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, P.; He, Y. 3D Printing of Ceramics: A Review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2019, 39, 661–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Roux, C.; Ouellet-Plamondon, C.; Caron, J.-F. Life Cycle Assessment of Limestone Calcined Clay Concrete: Potential for Low-Carbon 3D Printing. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 41, e01119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, A.; Jacquet, Y.; Caron, J.F.; Mesnil, R.; Ducoulombier, N.; De Bono, V.; Sanjayan, J.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Kloft, H.; Gosslar, J.; et al. Snapshot on 3D Printing with Alternative Binders and Materials: Earth, Geopolymers, Gypsum and Low Carbon Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 185, 107651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcassi, O.B.; Akemah, T.; Ben-Alon, L. 3D-Printed Lightweight Earth Fiber: From Tiles to Tessellations. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 12, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanifa, M.F.; Mendonça, P.; Figueiredo, B. Additive Manufacturing with Environmentally Sustainable Materials for Shell Envelop System. In Materials Science Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Bäch, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1082, pp. 290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Maury Njoya, I.Q.; Lecomte-Nana, G.L.; Barry, K.; Njoya, D.; El Hafiane, Y.; Peyratout, C. An Overview on the Manufacture and Properties of Clay-Based Porous Ceramics for Water Filtration. Ceramics 2025, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Chen, X.; Cao, D.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Koenders, E. Mathematical Modeling of Initial Exothermic Behavior and Thixotropic Properties in Nanoclay-Enhanced Cementitious Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomayri, T. Effect of Glass Microfibre Addition on the Mechanical Performances of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Composites. J. Asian Ceram. Soc. 2017, 5, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, M.D.M.; Fonseca Rocha, L.D.; Castrillon Fernandez, L.I.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Silva, E.C.C.M.; Neumann, R.; Mendoza Reales, O.A. Rheological Properties of Metakaolin-Based Geopolymers for Three-Dimensional Printing of Structures. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barve, P.; Bahrami, A.; Shah, S. A Comprehensive Review on Effects of Material Composition, Mix Design, and Mixing Regimes on Rheology of 3D-Printed Geopolymer Concrete. Open Constr. Build. Technol. J. 2024, 18, e18748368292859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugunov, S.; Adams, N.A.; Akhatov, I. Evolution of SLA-Based Al2O3 Microstructure During Additive Manufacturing Process. Materials 2020, 13, 3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Ennab, L.; Dixit, M.K.; Birgisson, B.; Pradeep Kumar, P. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Large-Scale 3D Printing Utilizing Kaolinite-Based Calcium Sulfoaluminate Cement Concrete and Conventional Construction. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2022, 5, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, P.; Borunda, L. Additive Manufacturing of Variable-Density Ceramics, Photocatalytic and Filtering Slats. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Berlin, Germany, 16–17 September 2020; Volume 1, pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Beregovoi, V.A.; Beregovoi, A.M.; Lavrov, I.Y. Technology of 3d Printing of Light Ceramics for Construction Products. Solid State Phenom. 2021, 316, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revelo, C.F.; Colorado, H.A. 3D Printing of Kaolinite Clay Ceramics Using the Direct Ink Writing (DIW) Technique. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 5673–5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, C.; Mata, J.J.; Renteria, A.; Gonzalez, D.; Gomez, S.G.; Lopez, A.; Baca, A.N.; Nuñez, A.; Hassan, M.S.; Burke, V.; et al. Direct Ink-Write Printing of Ceramic Clay with an Embedded Wireless Temperature and Relative Humidity Sensor. Sensors 2023, 23, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, E.; Gallego, J.M.; Colorado, H.A. 3D Printing via the Direct Ink Writing Technique of Ceramic Pastes from Typical Formulations Used in Traditional Ceramics Industry. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 182, 105285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothra, P.; Tiwari, S.; Kumar, S.; Verma, G.K. 3D Printing of Clay Ceramics Using Direct Ink Writing (DIW) Technique. In Proceedings of the Advances in Additive Manufacturing Volume—II; Kumar, S., Prabhu Raja, V., Sharma, P., Karthik, G.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Peng, Y.; Cheng, H.; Mou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liang, D.; Chen, M. Direct Ink Writing of 3D Cavities for Direct Plated Copper Ceramic Substrates with Kaolin Suspensions. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 12535–12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del-Mazo-Barbara, L.; Ginebra, M.-P. Rheological Characterisation of Ceramic Inks for 3D Direct Ink Writing: A Review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 18–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lan, J.; Wu, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y. Rheology and Printability of a Porcelain Clay Paste for DIW 3D Printing of Ceramics with Complex Geometric Structures. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 26450–26457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontovourkis, O.; Tryfonos, G. Integrating Parametric Design with Robotic Additive Manufacturing for 3D Clay Printing: An Experimental Study. In Proceedings of the International Association for Automation and Robotics in Construction, Berlin, Germany, 20–25 July 2018; pp. 918–925. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, S.; Bruce, M.; Clune, G.; Xie, R.; McGee, W.; Adel, A. Digital Design and Fabrication of Clay Formwork for Concrete Casting. Autom. Constr. 2023, 154, 104969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, A.; Ahmed, A. Ceramic Components—Computational Design for Bespoke Robotic 3D Printing on Curved Support. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Education and Research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Lodz, Poland, 9–21 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dielemans, G.; Lachmayer, L.; Khader, N.; Hack, N.; Raatz, A.; Dörfler, K. Robotic Repair: In-Place 3D Printing for Repair of Building Components Using a Mobile Robot. In Construction 3D Printing; Tan, M.J., Li, M., Tay, Y.W.D., Wong, T.N., Bartolo, P., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 156–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sauter, A.; Nasirov, A.; Fidan, I.; Allen, M.; Elliott, A.; Cossette, M.; Tackett, E.; Singer, T. Development, Implementation and Optimization of a Mobile 3D Printing Platform. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 6, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maierdan, Y.; Armistead, S.J.; Mikofsky, R.A.; Huang, Q.; Ben-Alon, L.; Srubar, W.V.; Kawashima, S. Rheology and 3D Printing of Alginate Bio-Stabilized Earth Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 175, 107380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akemah, T.; Ben-Alon, L. Developing 3D-Printed Natural Fiber-Based Mixtures. In Proceedings of the Bio-Based Building Materials, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 17–20 June 2023; Amziane, S., Merta, I., Page, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 555–572. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević, Z.; Strgačić, S.; Bischof, S. Barley Straw Fiber Extraction in the Context of a Circular Economy. Fibers 2023, 11, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.d.S.; Casetta, D.A.; Simon, L.C.; Kulay, L. Assessment of the Environmental Feasibility of Utilizing Hemp Fibers in Composite Production. Polymers 2025, 17, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gębarowski, T.; Jęśkowiak, I.; Wiatrak, B. Investigation of the Properties of Linen Fibers and Dressings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, A.A.; Sankarapandian, S.; Avudaiappan, S.; Flores, E.I.S. Mechanical Behaviour and Impact of Various Fibres Embedded with Eggshell Powder Epoxy Resin Biocomposite. Materials 2022, 15, 9044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millogo, Y.; Aubert, J.-E.; Hamard, E.; Morel, J.-C. How Properties of Kenaf Fibers from Burkina Faso Contribute to the Reinforcement of Earth Blocks. Materials 2015, 8, 2332–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.E.; Adamu, M.; Marouf, M.L.; Ahmed, O.S.; Drmosh, Q.A.; Malik, M.A. Mechanical Performance of Date-Palm-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Containing Silica Fume. Buildings 2022, 12, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhrif, I.; Oulkhir, F.Z.; El Jai, M.; Rihani, N.; Igwe, N.C.; Baalal, S.E. Earth-Based Materials 3D Printing, Extrudability and Buildability Numerical Investigations. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 6873–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhusal, S.; Sedghi, R.; Hojati, M. Evaluating the Printability and Rheological and Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Earthen Mixes for Carbon-Neutral Buildings. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voney, V.; Odaglia, P.; Brumaud, C.; Dillenburger, B.; Habert, G. From Casting to 3D Printing Geopolymers: A Proof of Concept. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 143, 106374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Camargo, I.L.; Fortulan, C.A.; Colorado, H.A. A Review on the Ceramic Additive Manufacturing Technologies and Availability of Equipment and Materials. Cerâmica 2022, 68, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, B.; Torres, S.; Yu, T.; Wu, D. A Review on Additive Manufacturing of Ceramics. In Proceedings of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Volume 1: Additive Manufacturing; Manufacturing Equipment and Systems; Bio and Sustainable Manufacturing, Erie, PA, USA, 10–14 June 2019; p. V001T01A001. [Google Scholar]

- Karl, D.; Duminy, T.; Lima, P.; Kamutzki, F.; Gili, A.; Zocca, A.; Günster, J.; Gurlo, A. Clay in Situ Resource Utilization with Mars Global Simulant Slurries for Additive Manufacturing and Traditional Shaping of Unfired Green Bodies. Acta Astronaut. 2020, 174, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, A.; Elliott, A.M.; Barnes, J.E.; Li, F.; Tan, W.; Cramer, C.L.; Nandwana, P.; Chmielus, M. Binder Jet 3D Printing—Process Parameters, Materials, Properties, Modeling, and Challenges. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 119, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odaglia, P.; Voney, V.; Dillenburger, B.; Habert, G. Advances in Binder-Jet 3D Printing of Non-Cementitious Materials. In RILEM Bookseries; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 28, pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, W. High-Fidelity Modeling of Binder–Powder Interactions in Binder Jetting: Binder Flow and Powder Dynamics. Acta Mater. 2023, 260, 119298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Bharathan, B.; Kermani, M.; Hassani, F.; Hefni, M.A.; Ahmed, H.A.M.; Hassan, G.S.A.; Moustafa, E.B.; Saleem, H.A.; Sasmito, A.P. Evaluation of Rheology Measurements Techniques for Pressure Loss in Mine Paste Backfill Transportation. Minerals 2022, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamee, P.K.; Aggarwal, N. Explicit Equations for Laminar Flow of Bingham Plastic Fluids. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2011, 76, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Khan, M.; McNally, C. A Comprehensive Review of Rheological Dynamics and Process Parameters in 3D Concrete Printing. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, E.C. Fluidity and Plasticity; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Dou, R.; Tang, W.; Hu, K.; Wang, L. Ceramic Paste for Space Stereolithography 3D Printing Technology in Microgravity Environment. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 3968–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschel, W.H.; Bulkley, R. Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi-Benzollösungen. Kolloid-Z. 1926, 39, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, I.; Shahare, H.; Bhandarkar, V.; Tandon, P. Numerical Study of Non-Newtonian Ceramic Slurry Flow in Extrusion Based Additive Manufacturing. Comput.-Aided Des. Appl. 2024, 21, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggerstaff, A.O.; Lepech, M.; Loftus, D. A Study on the Flow Behavior and Thixotropy of Biopolymer-Bound Soil Composite. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04024487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Chen, E.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Z. The Model of Ceramic Surface Image Based on 3D Printing Technology. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 5850967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihani, N.; Oulkhir, F.-Z.; Igwe, N.C.; Akhrif, I.; El Jai, M. 3D Clay Printing: A Taguchi Approach to Rheological Properties and Printability Assessment. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 601, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffrault, A.; Bessaies-Bey, H.; Roussel, N.; Coussot, P. Printing by Yield Stress Fluid Shaping. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 75, 103752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanastasiou, T.C. Flows of Materials with Yield. J. Rheol. 1987, 31, 385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, K.; Wang, C.; Chang, Q. The Rheological Performance of Aqueous Ceramic Ink Described Based on the Modified Windhab Model. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 075103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Gupta, M.K. Extrusion-Based 3D Printing of Ceramic Pastes: Mathematical Modeling and In Situ Shaping Retention Approach. Materials 2021, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzieri, G.; Ferrara, L.; Cremonesi, M. Numerical Simulation of the Extrusion and Layer Deposition Processes in 3D Concrete Printing with the Particle Finite Element Method. Comput. Mech. 2024, 73, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, B.; Chourasia, A.; Kapoor, A. Intricacies of Various Printing Parameters on Mechanical Behaviour of Additively Constructed Concrete. Archiv. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2024, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayswal, A.; Liu, J.; Harris, G.; Mailen, R.; Adanur, S. Creep Behavior of 3D Printed Polymer Composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2023, 63, 3809–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kladovasilakis, N.; Pemas, S.; Pechlivani, E.M. Computer-Aided Design of 3D-Printed Clay-Based Composite Mortars Reinforced with Bioinspired Lattice Structures. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Blanco, M.; Abali, B.E.; Völlmecke, C. An Experimental Methodology to Determine Damage Mechanics Parameters for Phase-Field Approach Simulations Using Material Extrusion-Based Additively Manufactured Tensile Specimens. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2443099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahdy, D.; Abd ElRahim, M.; AlAtassi, A. Robotic Fabrication of 3D Printed Clay Opening as a Passive Cooling System. Archit. Eng. 2023, 75, 468–473. [Google Scholar]

- Serdeczny, M.P.; Comminal, R.; Pedersen, D.B.; Spangenberg, J. Numerical Simulations of the Mesostructure Formation in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Sun, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Tao, Y. Geometric Quality Evaluation of Three-Dimensional Printable Concrete Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2024, 18, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadeh, S.; Comminal, R.; Serdeczny, M.P.; Bayat, M.; Bahl, C.R.H.; Spangenberg, J. Geometric Characterization of Orthogonally Printed Layers in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing: Numerical Modeling and Experiments. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovetova, M.; Kaiser Calautit, J. Thermal and Energy Efficiency in 3D-Printed Buildings: Review of Geometric Design, Materials and Printing Processes. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, A.T.; Abdallah, Y.K. The New Standard Is Biodigital: Durable and Elastic 3D-Printed Biodigital Clay Bricks. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Hassan, A.; Siadat, A.; Yang, G.; Chen, Z. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Validation of Deposited Corners of Any Angle in Direct Ink Writing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vele, J.; Prokop, S.; Ciganik, O.; Kurilla, L.; Achten, H.; Sysova, K. Non-Planar 3D Printing of Clay Columns: A Method for Improving Stability and Performance. In Proceedings of the Education and research in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe, Nicosia, Cyprus, 9–13 September 2024; Volume 1, pp. 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Ye, F.; Chen, F.; Yuan, W.; Yan, W. Numerical Investigation on the Viscoelastic Polymer Flow in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 81, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Lopez-Anido, R.A. Coupled Thermo-Mechanical Numerical Model to Minimize Risk in Large-Format Additive Manufacturing of Thermoplastic Composite Designs. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birosz, M.T.; Andó, M.; Jeganmohan, S. Finite Element Method Modeling of Additive Manufactured Compressor Wheel. J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. D 2021, 102, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matúš, M.; Križan, P.; Kijovský, J.; Strigáč, S.; Beniak, J.; Šooš, Ľ. Implementation of Finite Element Method Simulation in Control of Additive Manufacturing to Increase Component Strength and Productivity. Symmetry 2023, 15, 2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binega Yemesegen, E.; Memari, A.M. A Review of Experimental Studies on Cob, Hempcrete, and Bamboo Components and the Call for Transition towards Sustainable Home Building with 3D Printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 399, 132603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manière, C.; Harnois, C.; Marinel, S. 3D Printing of Porcelain and Finite Element Simulation of Sintering Affected by Final Stage Pore Gas Pressure. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 102063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, V.; Parisi, F.; Fieni, F.; Parisi, N. The New Boundaries of 3D-Printed Clay Bricks Design: Printability of Complex Internal Geometries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lin, X.; Kang, N.; Ma, L.; Wei, L.; Zheng, M.; Yu, J.; Peng, D.; Huang, W. A Novel High-Efficient Finite Element Analysis Method of Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, B.; Sofia, D.; Barletta, D.; Poletto, M. Review on Modeling Techniques for Powder Bed Fusion Processes Based on Physical Principles. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiges, J.; Chiumenti, M.; Moreira, C.A.; Cervera, M.; Codina, R. An Adaptive Finite Element Strategy for the Numerical Simulation of Additive Manufacturing Processes. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzaraa, I.; Ayrilmis, N.; Kuzman, M.K.; Belhouideg, S.; Bengourram, J. Micromechanical Models for Predicting the Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Wood/PLA Composite Materials: A Comparison with Experimental Data. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2022, 29, 6755–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, O.D.A.; De Los, Á.; Ortega Del Rosario, M.; Brischetto, S. Mechanical Properties Enhancement for Additive Manufactured Short Fiber Composites with Salt Remelting Post-Processing Mejora de Las Propiedades Mecánicas Para Compuestos de Fibras Cortas Fabricados Por Manufactura Aditiva Con Post-Procesamiento de Recocido En Sal. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Engineering, Sciences and Technology Conference (IESTEC), Panama City, Panama, 19–21 October 2022; pp. 723–727. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, R.; Brischetto, S.; Dipietro, I.R. Buckling Developed in 3D Printed PLA Cuboidal Samples under Compression: Analytical, Numerical and Experimental Investigations. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, M.H.; Maiaru, M. A Novel Higher-Order Finite Element Framework for the Process Modeling of Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 76, 103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giolu, C.; Pupăză, C.; Amza, C.G. Exploring Polymer-Based Additive Manufacturing for Cost-Effective Stamping Devices: A Feasibility Study with Finite Element Analysis. Polymers 2024, 16, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Promaue, C.; Das, S.; Nassehi, A. Finite Element Based Mechanical Properties Prediction for Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing to Enable Rapid Production System Design. Procedia CIRP 2024, 130, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C. Finite Element Analysis of Additively Manufactured Continuous Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Composites. JOM 2023, 75, 4150–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Van, V. Mechanical Evaluations of Bioinspired TPMS Cellular Cementitious Structures Manufactured by 3D Printing Formwork. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction Digitalisation for Sustainable Development: Transformation Through Innovation, Hanoi, Vietnam, 24–25 November 2020; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2428. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen-Van, V.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Nguyen, K.; Tran, P. Modelling of 3D Concrete Printing Process: A Perspective on Material and Structural Simulations. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 61, 103333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Van, V.; Nguyen-Xuan, H.; Panda, B.; Tran, P. 3D Concrete Printing Modelling of Thin-Walled Structures. Structures 2022, 39, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinold, J.; Gudžulić, V.; Meschke, G. Computational Modeling of Fiber Orientation during 3D-Concrete-Printing. Comput. Mech. 2023, 71, 1205–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntharalingam, T.; Upasiri, I.; Nagaratnam, B.; Poologanathan, K.; Gatheeshgar, P.; Tsavdaridis, K.D.; Nuwanthika, D. Finite Element Modelling to Predict the Fire Performance of Bio-Inspired 3D-Printed Concrete Wall Panels Exposed to Realistic Fire. Buildings 2022, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantyghem, G.; Ooms, T.; De Corte, W. FEM Modelling Techniques for Simulation of 3D Concrete Printing. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.06907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfs, R.J.M.; Bos, F.P.; Salet, T.A.M. Early Age Mechanical Behaviour of 3D Printed Concrete: Numerical Modelling and Experimental Testing. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 106, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.; Vaculik, J.; Soebarto, V.; Griffith, M.; Jabi, W. Feasibility of 3DP Cob Walls under Compression Loads in Low-Rise Construction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasi, H.; Mollah, M.T.; Marla, D.; Saffari, H.; Spangenberg, J. Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling of Top-Down Digital Light Processing Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2023, 15, 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedermann, M.; Meboldt, M. Computational Design Synthesis of Additive Manufactured Multi-Flow Nozzles. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Abbaoui, K.; Al Korachi, I.; El Jai, M.; Šeta, B.; Mollah, M.T. 3D Concrete Printing Using Computational Fluid Dynamics: Modeling of Material Extrusion with Slip Boundaries. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 118, 448–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinloye, T.M.; Yoon, W.B. Application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) in the Deposition Process and Printability Assessment of 3D Printing Using Rice Paste. Processes 2022, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.T.; Comminal, R.; Serdeczny, M.P.; Šeta, B.; Spangenberg, J. Computational Analysis of Yield Stress Buildup and Stability of Deposited Layers in Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, B.; Cruz, P.J.S.; Carvalho, J.; Moreira, J. Challenges of 3D Printed Architectural Ceramic Components Structures: Controlling the Shrinkage and Preventing the Cracking. In Proceedings of the IASS Annual Symposia, Barcelona, Spain, 7–10 October 2019; pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gleiser, L.; Pierer, R.; Markin, S.; Butler, M.; Mechtcherine, V. Additive Manufacturing with Earth Based Materials—Minimization of Shrinkage Deformation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Earthen Construction, Edinburgh, UK, 8–10 July 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 52, pp. 12–21, ISBN 978-3-031-62689-0. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mahdy, D.; AbdelRahim, M.; Alatassi, A. Assessment of Airflow Performance Through Openings in 3D Printed Earthen Structure Using CFD Analysis. In Proceedings of the RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication, Munich, Germany, 4–6 September 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 53, pp. 423–430, ISBN 978-3-031-70030-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Jin, Z.; Hu, G.; Gu, J.; Yu, S.-Y.; Lee, J.-H.; Gu, G.X. Machine Learning and Experiments: A Synergy for the Development of Functional Materials. MRS Bull. 2023, 48, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Nguyen, D.S.; Le-Hong, T.; Van Tran, X. Machine Learning-Based Optimization of Process Parameters in Selective Laser Melting for Biomedical Applications. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 33, 1843–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Wen, W.; Wang, K.; Peng, Y.; Ahzi, S.; Chinesta, F. Tailoring Interfacial Properties of 3D-Printed Continuous Natural Fiber Reinforced Polypropylene Composites through Parameter Optimization Using Machine Learning Methods. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, V.; Vargas Velasquez, J.D.; Fantucci, S.; Autretto, G.; Gabrieli, R.; Gianchandani, P.K.; Armandi, M.; Baino, F. 3D-Printed Clay Components with High Surface Area for Passive Indoor Moisture Buffering. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, F.; Liu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, X.; Wan, Y.; Lu, L. Ceramic 3D Printed Sweeping Surfaces. Comput. Graph. 2020, 90, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.-Q.; Klug, C.; Schmitz, T.H. Fiber-Reinforced Clay: An Exploratory Study on Automated Thread Insertion for Enhanced Structural Integrity in LDM. Ceramics 2023, 6, 1365–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiorgio, V.; Bianchi, I.; Forcellese, A. Advancing Decarbonization through 3D Printed Concrete Formworks: Life Cycle Analysis of Technologies, Materials, and Processes. Energy Build. 2025, 332, 115444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Fratello, V.; Rael, R. Innovating Materials for Large Scale Additive Manufacturing: Salt, Soil, Cement and Chardonnay. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 134, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, M.; Teixeira, F.F.; Zhu, G. Structural Performance of Bio-Clay Cobot Printed Blocks. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA), Ahmedabad, India, 18 March 2023; Koh, I., Reinhardt, D., Makki, M., Khakhar, M., Bao, N., Eds.; The Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia: Hong Kong, China, 2023; Volume 2, pp. 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, B.; Noor Mohamed, N.A.; Tay, Y.W.D.; Tan, M.J. Bond Strength in 3D Printed Geopolymer Mortar. In Proceedings of the RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication, Zurich, Switzerland, 10–12 September 2018; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 19, pp. 200–206, ISBN 978-3-319-99518-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti, E.; Moretti, M.; Chiusoli, A.; Naldoni, L.; De Fabritiis, F.; Visonà, M. Mechanical Properties of a 3D-Printed Wall Segment Made with an Earthen Mixture. Materials 2022, 15, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, N.C.; Ozkan Ekinci, M.; Sahin, O.; Ilcan, H.; Kul, A.; Yildirim, G.; Sahmaran, M. Mechanical Anisotropy Evaluation and Bonding Properties of 3D-Printable Construction and Demolition Waste-Based Geopolymer Mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 134, 104814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tan, J.; Sun, J.; Guo, H.; Bai, J.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, D.; Liu, G. Effect of Sintering Temperature on the Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of ZrO2 Ceramics Fabricated by Additive Manufacturing. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 11392–11399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isachenkov, M.; Chugunov, S.; Akhatov, I.; Shishkovsky, I. Regolith-Based Additive Manufacturing for Sustainable Development of Lunar Infrastructure—An Overview. Acta Astronaut. 2021, 180, 650–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

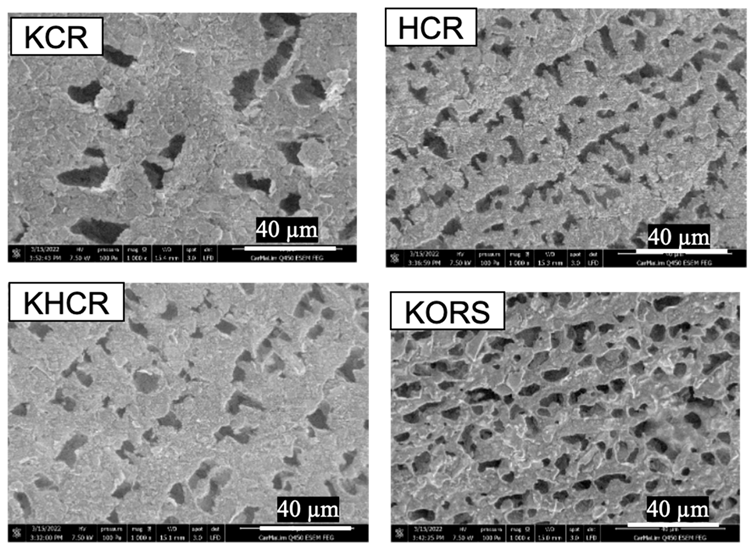

| Material | Key Properties | Processing Requirements | Advantages | Challenges | Illustrative SEM Micrographs | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay-based pastes (e.g., Kaolinite, illite, bentonite, earthen mixes with sand and silt, grog-reinforced clay bodies) | Plasticity, capillarity, thixotropy, and moisture-dependent shrinkage | Water-based mixing, rheology, and drying control, optional firing depending on application. | Abundant, low-carbon when unfired, recyclable, bio-compatible (to some extent) | Moisture sensitivity, shrinkage, and cracking during drying, compositional variability |  SEM of porous kaolin- and halloysite-based ceramic (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) [105].

SEM of porous kaolin- and halloysite-based ceramic (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) [105]. | [44,68,71,89,106] |

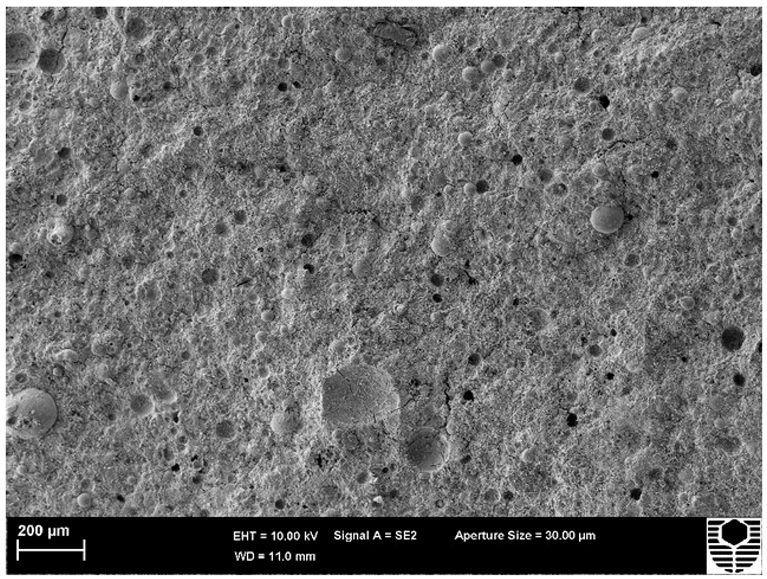

| Geopolymers (e.g., fly-ash geopolymer, metakaolin-based geopolymer, slag-based binders) | Alkaline activation and fast early-strength development | Controlled alkaline activation, curing conditions | Low-carbon alternative with high mechanical strength | Chemical handling and long-term durability are still under study |  SEM of a fly ash-based geopolymer (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) [107].

SEM of a fly ash-based geopolymer (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) [107]. | [108,109] |

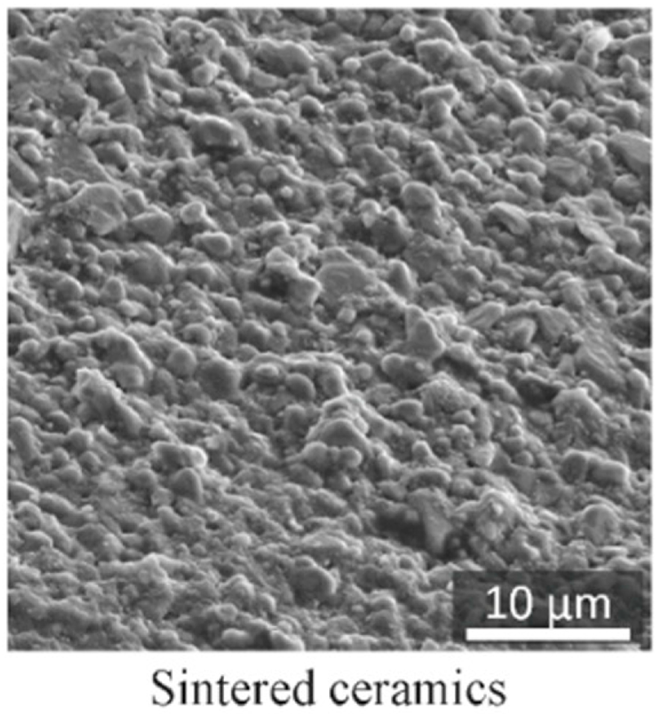

| Technical ceramics (e.g., Alumina (Al2O3), zirconia (ZrO2), porcelain, silica-based ceramics) | High stiffness and thermal stability, brittle fracture behavior | Slurry control, drying, high-temperature sintering | High durability, precise functional performance | Shrinkage, energy-intensive firing, and cracking risk |  Al2O3 Microstructure (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) [110].

Al2O3 Microstructure (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) [110]. | [110,111,112,113] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duque-Castro, R.G.; Berrocal, D.I.; Medina Pérez, M.N.; Castillero-Ortega, L.E.; Jaén-Ortega, A.A.; Blandón Rodríguez, J.; Ortega-Del-Rosario, M.D.L.A. Additive Manufacturing with Clay and Ceramics: Materials, Modeling, and Applications. Ceramics 2025, 8, 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040148

Duque-Castro RG, Berrocal DI, Medina Pérez MN, Castillero-Ortega LE, Jaén-Ortega AA, Blandón Rodríguez J, Ortega-Del-Rosario MDLA. Additive Manufacturing with Clay and Ceramics: Materials, Modeling, and Applications. Ceramics. 2025; 8(4):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040148

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuque-Castro, Rafael G., Diana Isabel Berrocal, Melany Nicole Medina Pérez, Luis Ernesto Castillero-Ortega, Antonio Alberto Jaén-Ortega, Juan Blandón Rodríguez, and Maria De Los Angeles Ortega-Del-Rosario. 2025. "Additive Manufacturing with Clay and Ceramics: Materials, Modeling, and Applications" Ceramics 8, no. 4: 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040148

APA StyleDuque-Castro, R. G., Berrocal, D. I., Medina Pérez, M. N., Castillero-Ortega, L. E., Jaén-Ortega, A. A., Blandón Rodríguez, J., & Ortega-Del-Rosario, M. D. L. A. (2025). Additive Manufacturing with Clay and Ceramics: Materials, Modeling, and Applications. Ceramics, 8(4), 148. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics8040148