1. Introduction

Electrical conduction in aluminum nitride (AlN) has been studied since the 1970s [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. In addition to the material’s susceptibility to incorporating trace amounts of oxygen [

6,

7], intrinsic (nitrogen and aluminum vacancies [

8]) and extrinsic point defects (e.g., interstitial carbon) [

1,

2] can influence electrical conduction. The reported values for electrical conductivity in AlN exhibit significant variation, further complicating the understanding of this phenomenon [

2,

9]. Because aluminum scandium nitride (Al

1−xSc

xN) based ferroelectric materials are promising for non-volatile switching in neuromorphic computing applications due to their high remanent polarization, wide memory window, and non-toxicity [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], understanding the structural origins of electrical behavior in this material is crucial for mitigating deleterious effects on devices. Typically, electrical leakage in Al

1−xSc

xN is regarded as undesirable and is often attributed to structural defects, including nitrogen vacancies [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In this study, we systematically investigate the electrical conduction in Al

1−xSc

xN from the point of view that its electrical properties are influenced by point defects incorporated during growth. Point defect incorporation during growth, be it intrinsic, like vacancies or interstitials, or extrinsic, like impurity elements, can originate from either thermodynamic or kinetic processes. For Al

1−xSc

xN films that are sputter deposited at high temperatures and naturally cooled under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions, the cooling rate may be sufficiently high to kinetically preserve higher concentrations of point defects incorporated during growth. Such phenomena are commonly observed in complex oxides, where sputtered materials must undergo slow cooling under a high oxygen partial pressure to prevent oxygen deficiency [

22,

23]. In addition, vacancies can bind with extrinsic impurities when the interaction is energetically favorable [

24,

25].

We observe an Arrhenius-type dependence of electrical conductivity in sputtered Al1−xScxN films on the growth temperature, suggesting correlation with equilibrium point defect concentration. Despite significant direct current (DC) electrical leakage, these films demonstrate ferroelectric behavior, indicating that polarization and free charge carriers can behave independently under external electric fields in this material. Ferroelectric behavior was independently characterized using two different experimental methods. The combined structural characterization, optical property measurements, and physics-based simulations support our contention that the presently observed electrical leakage dependence on the Al1−xScxN growth temperature arises from point defects within the material.

2. Materials and Methods

Al1−xScxN thin films on epitaxial TiN(111) buffered Si(111) substrates were grown with UHV reactive sputtering at substrate temperatures ranging from 446 °C to 805 °C. Current–voltage characteristics were obtained from capacitor structures, which were comprised of Si(111)/TiN(111)/Al1−xScxN(0002)/poly-W layers. These structures underwent a comprehensive analysis employing various structural characterization techniques, including X-ray diffraction (XRD), time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) in a plasma focused ion beam/scanning electron microscope (PFIB/SEM), and X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) in a scanning electron microscope (SEM). In addition, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were used to estimate the formation energies of the relevant point defect for comparison with experimental data. Finally, ferroelectric properties of the Al1−xScxN films were measured using electrical measurements and piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM).

Growth

Si(111) wafers (2”, arsenic (As) doped, 0.001–0.005 Ω cm) were cleaned in repeated cycles of 15.7 M HNO

3(aq), deionized water, and 18.4 M HF(aq). Al

1−xSc

xN films were deposited using reactive sputtering in a load-locked UHV system with a base pressure of <5 × 10

−10 Torr. The substrate temperature, as measured by a thermocouple, was calibrated using direct optical access infrared pyrometry with the Si emissivity set to 0.68 [

10]. Wafers were heated to 805 °C for 30 min prior to growth. Approximately 200 nm thick epitaxial TiN(111) buffer layers were deposited by sputtering an elemental Ti target (99.995%, Kurt Lesker) in the dc mode at 1.4 A gun current while flowing 4.5 sccm N

2 (99.999+%, Airgas) at a total pressure of 9.5 mTorr. Following growth of the TiN(111) buffer layer, the sample was cooled to the film growth temperature, which ranged from 805 °C to 446 °C. Al

1−xSc

xN films were deposited by simultaneously sputtering elemental Al (99.9995%, Kurt Lesker) and Sc (99.99%, Matsurf Technologies, St. Paul, MN, USA) targets in the dc mode at 1.2 A and 0.4 A gun currents, respectively, under an input flow of Ar (20 sccm, 99.999%) and N

2 (5.5 sccm, 99.999%), resulting in a total pressure of 5.5 mTorr. The resulting Al:Sc ratio is approximately 30:4 (

Table S1); we choose this to avoid Sc compositional segregation at higher Sc concentrations [

10]. A substrate bias of −100 V was applied during growth of both TiN and Al

1−xSc

xN. After growth, samples were cooled naturally in UHV. Tungsten (W) top electrodes were defined by sputtering at room temperature through a stainless-steel shadow mask with a square array of 500 µm holes (Stencils Unlimited, Tualatin, OR, USA) using an elemental W (99.95%, Kurt Lesker, Jefferson Hills, PA, USA) target under 20.0 sccm Ar (99.999+%, Airgas, Radnor, PA, USA) input flow at a total pressure of 10.0 Torr in a growth system with a base pressure of <1 × 10

−9 Torr.

Property Measurement

Quasi-DC electrical properties of Al1−xScxN films were probed using two electrode measurements taken from the degenerately doped Si substrate to the W top electrode. Current voltage characteristics were obtained using a Keithley 4200A-SCS with the samples mounted on a microprobe station (Nextron, Yongin-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). The substrate voltage was ramped from 0 V to 20 V, then from 20 V to –20 V, and finally from –20 V to 0 V at a 40 mV step size and an approximately 8 ms interval. Limited current auto-ranging was used to accommodate the potential for large changes in material resistivity due to resistive switching and dielectric breakdown. Successive positive and negative 25 kHz triangle pulses (rise/fall time = 10 μs, no delay) were used to measure the polarization–voltage (P–V) responses. Positive-up negative-down (PUND) measurements were performed using trapezoidal pulses with 10 µs rise/fall time, 10 µs pulse duration, and 10 µs delay between pulses.

Defect fluorescence was characterized at room temperature using a home-built confocal microscope. A 532-nm laser at 10 mW power was used to excite the point defects, and a 550 nm long-pass filter suppressed the residual excitation laser. Fluorescence was collected into a single-mode fiber for spatial filtering and then recorded on a photon detector (SPD). The sample was raster-scanned using a piezoelectric stage and galvanometric mirrors to locate defect clusters. Once identified, their photoluminescence spectra were collected with a Princeton Instruments spectrometer covering 500–1000 nm.

Piezoresponse force microscopy (PFM) was performed using a Bruker Dimension Icon atomic force microscope (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) (AFM) with a lock-in frequency of 60 kHz and an ac bias drive amplitude of 10 V applied to the sample. Out-of-plane piezoresponse coefficient (d33) was measured through height changes as a function of the AFM tip bias in pristine films. Residual changes to piezoresponse due to ferroelectricity were probed using DC poling experiments, which were performed in the PFM mode by setting the AC bias drive amplitude applied to the sample to 100 mV while applying DC bias values of ±3 V, ±6 V, and ±12 V to the AFM tip separately in different regions of the sample respective to the sample chuck.

Structural Characterization

Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) in a ThermoFisher (Hillsboro, OR, USA) Helios Hydra PFIB/SEM was used to measure signal intensity for detection of trace elements in Al1−xScxN films through depth profiling. Xe+, Ar+, and N2+/N+ plasma sources for the ion beam were employed with a 30 kV accelerating voltage in the positive polarity mode, with the N plasma source chosen to reduce the amount of ion beam induced mixing. For the N source, 30 µm horizontal field width and 2.4 nA nominal beam current (2.82–2.97 nA actual) were used; for the Ar source, 30 µm horizontal field width and 2.0 nA nominal beam current (2.91 nA actual) were used; and for the Xe source, 30 µm horizontal field width and 1.0 nA nominal beam current (1.07 nA actual) were used. Actual beam current varied on the order of 0.01 nA during the course of the experiments. ToF-SIMS experiments were conducted under ~9 × 10−7 Torr vacuum. Bulk composition measurements using X-ray energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) in SEM were performed using an FEI Quanta 600F Environmental SEM (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA) in high vacuum mode equipped with a Bruker Xflash 6 SDD EDS detector. Structural characterization using XRD was performed using a Panalytical Empyrean diffractometer with a χ-φ-x-y-z stage using Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 1.540598 Å) selected through a 4-bounce Ge(220) monochromator. Symmetric θ/2θ, asymmetric φ, and ω rocking curve scans were collected using a PIXcel-3D detector (Malvern Panalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands).

Theory and Calculations

The vacancy formation energy

for crystalline AlN and Al

1−xSc

xN systems with charge state

was calculated using the equation [

26,

27],

In Equation (1),

is the total energy of the system with one nitrogen vacancy in the charge state

. Note that here

is the multiple of the charge quantum (e.g.,

) and is unitless.

represents the energy of the corresponding bulk nitride without vacancies,

is the chemical potential of nitrogen in the bulk system,

is the valance band maximum energy of the bulk system, and

is the electron chemical potential. The value of

for the system is not fixed and depends on the chemical environment. Thus, in our calculations we have taken the value of

in the range from the valance band maximum (VBM) to the conduction band minimum (CBM). The chemical potential of nitrogen,

, is calculated using the relation [

28]:

where

is the chemical potential of nitrogen in a reference state taken to be solid hcp nitrogen, which is the ground state at 0 K,

is the enthalpy of formation of the bulk crystalline nitride without vacancies, and the parameter

specifies the stoichiometric condition such that

defines the Al-rich condition and

defines the N-rich condition. We have also calculated the electrostatic potential alignment differences arising from the presence of the vacancy for the charge states q = 0, +1, +2, and +3 and found the effect to be very small (

Figure S1 in Supporting Information (SI)).

We have performed DFT calculations in Quantum Espresso [

29] using a plane wave-pseudopotential basis set using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange correlation functional [

30]. Ultrasoft pseudopotentials [

31] were used for all atoms (Al, Sc, and N) in the calculations. For all calculations, the plane wave cut-off energy was set at 70 Ry (~952 eV) after optimization, and k-space integrations were performed with a k-mesh of

using the Monkhorst-Pack sampling scheme. A

sized supercell of pristine wurtzite-type AlN was constructed using the experimental lattice constant a = 3.11 Å [

32], and the optimized value of the c/a ratio was found to be 1.62. Using this ratio, the calculated value of c is 5.038 Å, which agrees with the experimental result (4.98 Å) to within a few percent [

32]. The supercell contained a total of 32 atoms (16 Al and 16 N). One nitrogen atom was then removed from the system to create a N vacancy. After creating a vacancy, the system was again fully relaxed and the lattice parameter

was optimized while fixing the c/a ratio at 1.62. The optimized value of the lattice parameter after introducing the vacancy was found to be a = 3.12 Å. Self-consistent field (

scf) calculations were performed for pristine AlN, AlN with one neutral N vacancy, and for AlN with a charged N vacancy with charge states of +1, +2, and +3.

A Sc-containing system was then created by replacing three of the Al atoms in the structure with Sc atoms to form Al13Sc3N16 (Al0.8125Sc0.1875N). Corresponding Sc-containing systems with one neutral vacancy and with one charged vacancy with charge states of +1, +2, and +3 were also made. These systems (pristine Al0.8125Sc0.1875N, Al0.8125Sc0.1875N with one neutral vacancy, and Al0.8125Sc0.1875N with one charged vacancy with charge states +1, +2, and +3) were also relaxed and optimized lattice parameters were used for scf calculations. To investigate the effect of proximity of the nitrogen vacancy to a Sc atom on the formation energy, we constructed a larger Sc-alloyed AlN (Al0.79Sc0.21N) supercells having 48 (2 × 2 × 3) atoms. Two configurations were considered: one in which the nitrogen vacancy is located close to a Sc atom, and another where the vacancy is positioned farther away. Each system with and without a nitrogen vacancy was relaxed and optimized parameters were used for scf calculations. The scf calculations were run for neutral as well as charged vacancies with charge states +1, +2, and +3 for both systems.

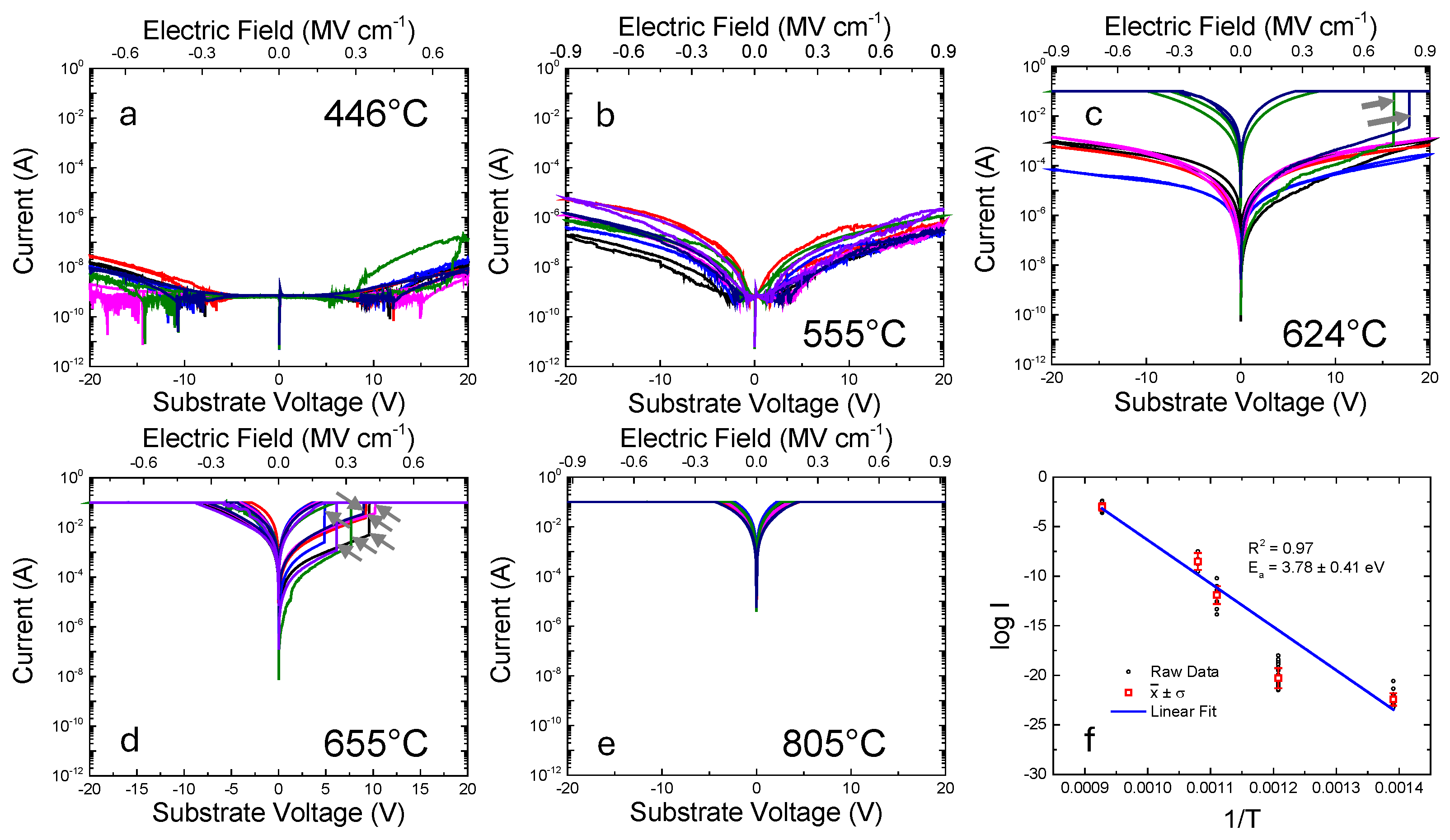

3. Results

Figure 1a–e illustrate the current–voltage characteristics of multiple devices, each composed of one ~200–300 nm thick Al

1−xSc

xN film deposited at different temperatures on an epitaxial TiN(111) buffer layer on Si(111). While there is some variability in the electrical behavior observed among different devices under the same growth conditions (

Figure 1a,b,e), it is notable that the electrical conductivity remains relatively consistent, differing by no more than one order of magnitude for growth temperatures of 446 °C, 555 °C, and 805 °C. We hypothesize that device-to-device variation is influenced by differences in spatial distribution of point defects in the Al

1−xSc

xN films. For growth temperatures of 624 °C and 655 °C, several devices exhibit an irreversible increase in current beyond a certain threshold voltage. In

Figure 1f, the current at 2 V (or an equivalent current for the film grown at 446 °C, where the current at 2 V is too low, so the current at 10 V divided by 5 is used instead) is plotted on a logarithmic scale against the inverse of the growth temperature. Fitting the data using an Arrhenius law yields an apparent activation energy of 3.78 eV, with a correlation coefficient of R

2 = 0.97. The significant increase in conductivity observed in some devices made from Al

1−xSc

xN films grown at 624 °C and 655 °C is consistent with dielectric breakdown.

Figure 2 shows typical current–voltage characteristics from two devices grown at each of these two temperatures. The threshold voltage at which the current exhibits a substantial increase is likely to correspond to the breakdown voltage. Notably, the film grown at 624 °C exhibits a significantly higher breakdown voltage compared to the one grown at 655 °C. These data indicate that Al

1−xSc

xN films with lower electrical conductivity tend to exhibit higher breakdown voltages.

We note that the current–voltage characteristics for Al

1−xSc

xN films grown at 555 °C and higher temperatures differ significantly from reports in the literature as the current increases significantly even for lower applied electric fields < 0.1 MV/cm, independent of dielectric breakdown. The data are consistent with the semiconducting behavior in Al

1−xSc

xN arising from free charge carrier conduction. While electrical leakage can be problematic in ferroelectrics, semiconducting ferroelectrics hold potential for various applications as multifunctional materials [

33,

34,

35]. Structural characterization of the Al

1−xSc

xN films was performed using XRD.

Figure 3a,b show symmetric θ/2θ and asymmetric φ scans of Al

1−xSc

xN films on epitaxial TiN(111) buffer layers on Si(111). In the θ/2θ scans, only the Si (111) and TiN (111) family of peaks are observed. In the asymmetric φ scans, six Si (513) peaks and six TiN (042) peaks are observed at the same φ values. This confirms that the TiN buffer layers were grown on Si(111) substrates epitaxially in the cube-on-cube orientation, with TiN(111)∥Si(111) and TiN(

)∥Si(

). Al

1−xSc

xN films grown at temperatures above 600 °C exhibit only the (0002) family of peaks in the θ/2θ scan and show six

peaks offset 30° from the TiN (042) peaks in the asymmetric φ scan. These films are, thus, epitaxial with Al

1−xSc

xN(0002)∥TiN(111)∥Si(111) and Al

1−xSc

xN

∥TiN(

)∥Si(

). However, for growth temperatures below 600 °C, the asymmetric φ scans show that the in-plane registry of the Al

1−xSc

xN film with respect to the epitaxial TiN buffer layer is lost. This loss of Al

1−xSc

xN epitaxy at growth temperatures below 600 °C is consistent with previous observations on growth of AlN on Si(111) [

36]. Reciprocal space maps (RSM) depicting the peaks corresponding to the film (0002) and buffer (111) reflections for different film growth temperatures are shown in

Figure S2 of the Supplemental Information (SI) section. Notably, the width of the film peak in the in-plane direction increases as the film growth temperature decreases.

To ascertain the bulk composition of the Al

1−xSc

xN films, SEM-EDS analysis was used. In

Figure 4a, spectra from Al

1−xSc

xN films grown at temperatures ranging from 446 °C to 805 °C are presented, and the corresponding compositional data are summarized in

Table S1 (in Supporting Information). The results indicate that the primary constituents of the film are aluminum, scandium, and nitrogen, with trace amounts of oxygen also detected. The film compositions exhibit no statistically significant variation with respect to the growth temperature. Due to the interaction volume of the electron beam, a Ti signal from the TiN buffer layer is also present. Through FIB/ToF-SIMS depth profiling (

Figure 5a–e) of the capacitor devices, we can discern the layers, including the tungsten (W) top electrode, the Al

1−xSc

xN film, and the TiN buffer layer. Here we note that the ToF-SIMS intensity does not necessarily scale linearly with the concentration due to differences in sputter yield and ionization cross section [

37] and cannot be used to quantitatively determine the concentration [

38]. Nonetheless, trace element detection and the comparison of relative intensities are possible. In the W layer, there is minimal detection of the Al, Sc, N, Ti, and O signal. The EDS and ToF-SIMS data are consistent in showing the main components of the Al

1−xSc

xN films to be Al, Sc, and N. When the depth profile reaches the top electrode/Al

1−xSc

xN film interface, we observe that Al, Sc, N, Ti, and O signals rise. This indicates that the Al

1−xSc

xN films contain trace Ti and O at a level detectable through ToF-SIMS. Within the Al

1−xSc

xN films grown at 624 °C, 655 °C, and 805 °C, there are small variations in the signal intensity that may stem from minor fluctuations in ion beam current, local variations in the sputter yield of the film, or uneven re-sputtering at the edge of the ion beam milled crater. Finally, we observe that the Ti:(Al+Sc) intensity ratio within the film at a fixed distance from the top electrode/film interface exhibits an approximately linear increase as a function of Al

1−xSc

xN film growth temperature (

Figure 5f). The integrated mass spectra corresponding to

Figure 5a–e are shown in

Figure S3. Projected top view (

Figure S4) and side view (

Figure S5) images of the ToF-SIMS data are also shown in the

Supporting Information section.

The ferroelectric properties of the Al

1−xSc

xN thin films were characterized using both polarization-electric field hysteresis and positive-up negative-down (PUND) measurements (

Figure 6). These measurements were only performed on Al

1−xSc

xN grown at 446 °C and 555 °C because films grown at higher temperatures exhibited significant electrical leakage, impeding the measurement. Both of these films exhibit a remanent polarization (P

r)~0.13 μC cm

−2 (

Figure 6a,c,d,f), which is significantly lower than what is reported for Al

1−xSc

xN [

39]. There are several potential factors contributing to the low P

r. First, the Sc composition of Al

1−xSc

xN films in the current study are not optimized as the focus is on the origins of electrical leakage. Previously we found compositional segregation consistent with spinodal decomposition for Sc compositions above 20 at%, so, for this study, we chose a Sc composition below this value to avoid possible complications related to phase separation [

10]. Second, an electrical leakage induced IR drop in the ferroelectric properties can decrease the effective electric field in the material and, therefore, the P

r. Finally, the electrical leakage increases significantly when the applied electric field approaches 0.2–0.3 MV/cm, at which point the polarization saturates; on the other hand, some works report higher coercive fields~2–4 MV/cm [

39]. The relationship between the onset electric field for increased electrical leakage and the electrical breakdown point may play a role. For the current study, even though the samples grown at 446 °C and 555 °C do not undergo dielectric breakdown up to 0.8 MV/cm, the electrical leakage onset is significantly lower (~0.3 MV/cm). However, we demonstrate that there is a ferroelectric response even in the presence of significant electrical leakage, indicating that Al

1−xSc

xN is potentially a semiconducting ferroelectric material. The PUND measurements at saturation show comparable leakage currents for Al

1−xSc

xN grown at 446 °C and 555 °C; remanent polarization of the 555 °C samples begins to decrease after saturation. This indicates that the leakage current increases faster than the polarization current beyond a threshold voltage for the higher temperature growth. These results are also consistent with the electrical leakage results, showing that increased growth temperature lowers the breakdown voltage.

Room temperature photoluminescence (PL) was measured on Al

1−xSc

xN grown both with inductively coupled plasma (ICP) assist in the absence of substrate heating and at 805 °C without ICP assist (

Figure 7a). Both samples exhibit broad emission that is peaked at wavelengths between 600 nm and 700 nm. This is consistent with radiative recombination from oxygen substitutional defects [

40,

41]. Furthermore, the two samples exhibit similar oxygen concentrations, as indicated through EDS (

Figure 4) and ToF-SIMS (

Figure 5). Photoluminescence imaging of the two samples shows similar features: bright emission from small clusters and weaker emission from the surrounding field regions. In both the clusters and the surrounding field regions, the PL intensity of Al

1−xSc

xN grown at higher temperature is significantly lower than that of Al

1−xSc

xN grown at lower temperature. Because trace oxygen content in the two samples is very similar, the difference in PL intensity indicates increased non-radiative recombination in the Al

1−xSc

xN grown at higher temperature. This is consistent with increased point defect concentration, which can result in higher rates of Shockley–Read–Hall recombination through trap-assisted non-radiative processes [

42,

43,

44].

Ferroelectric behavior was also confirmed through DC poling PFM experiments. The piezoresponse amplitude and phase of the pristine sample (

Figure 8a and

Figure 8c, respectively) and of the same area of the sample after poling at ±3 V, ±6 V, and ±12 V (

Figure 8b and

Figure 8d, respectively) are consistent with changes in piezoresponse due to ferroelectricity, although we note that this response can also arise from ionic conductivity. Opposite signs of the piezoresponse phase are observed for positive and negative DC poling voltages, as expected for a ferroelectric material. Also, the change in the piezoresponse amplitude and phase is more apparent in the films grown at lower temperatures (446 °C and 555 °C). This is primarily because these samples exhibited less electrical leakage, resulting in a higher ratio of the polarization current to the shunting current, which, in turn, manifests as an increased piezoresponse.

Figure 8 shows piezoresponse measured in low voltage mode, in which the maximum tip bias in the AFM is ±12 V, limiting the electric field in the Al

1−xSc

xN to ~1.2 MV cm

−1 without considering shunting currents, which is slightly lower than the reported coercive field of Al

1−xSc

xN [

39]. High voltage poling data was also collected (DC bias: ±15 V, ±30 V); details are provided in the

Supporting Information (Supporting Information, Figure S6).

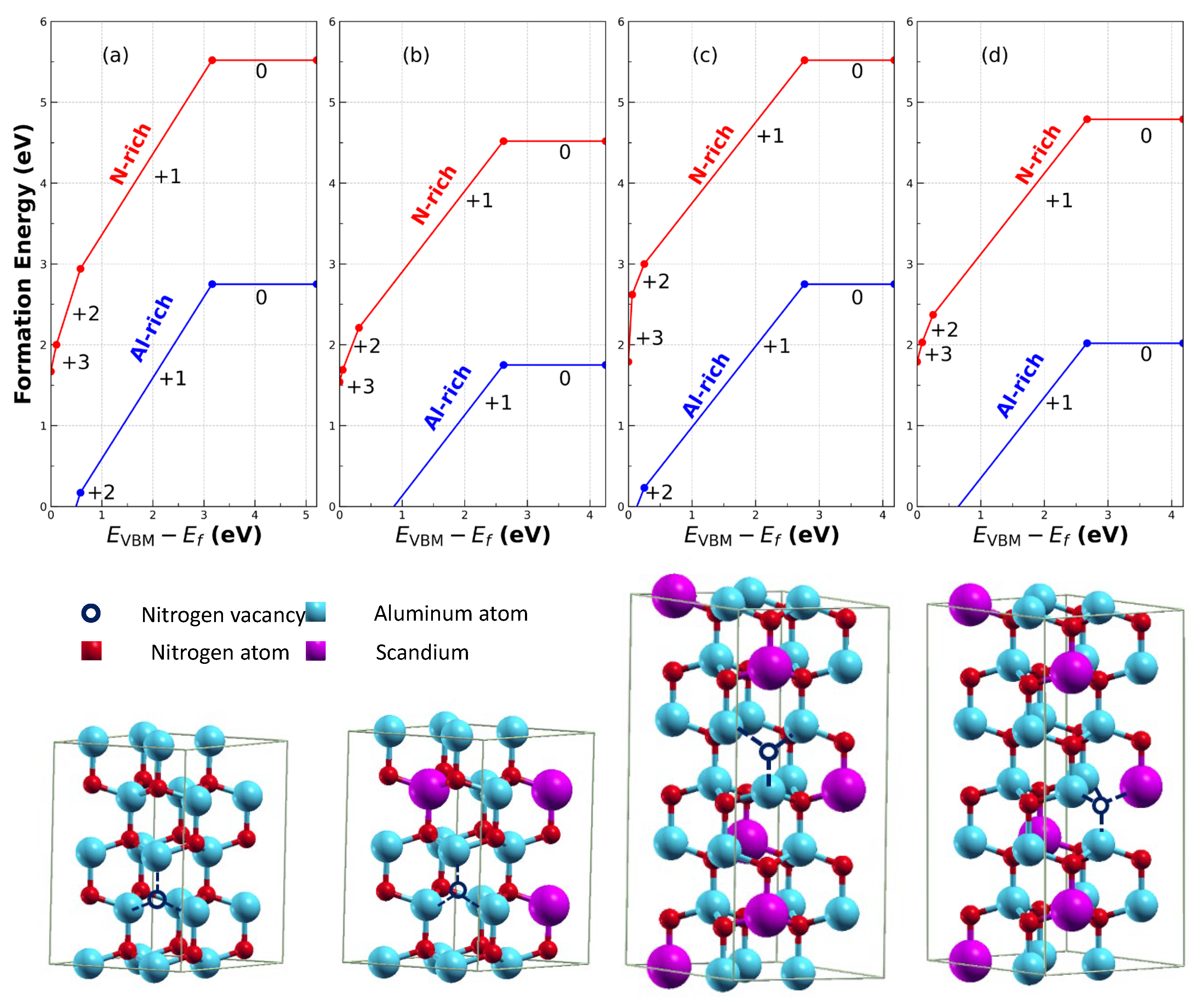

The bandgap energies for pristine AlN and Al

0.8125Sc

0.1875N were calculated to be 5.21 eV and 4.25 eV, respectively, using the PBE functional. Underestimation of the bandgap in the generalized gradient approximation is well known [

45]. The N-vacancy formation energy of AlN and Al

0.8125Sc

0.1875N as a function of Fermi energy are plotted in

Figure 9a,b. In both systems, kink discontinuities arise because the formation energy of a nitrogen vacancy with charge states +3, +2, and +1 decreases as the Fermi energy approaches the valence band maximum (VBM). Increasingly positively charged configurations of the vacancy have a lower formation energy and are energetically preferred closer to the VBM. Furthermore, the N-vacancy formation energy is 2.77 eV lower under Al-rich conditions compared to N-rich conditions. At the VBM, the formation energies for a N-vacancy with +3 charge state are 1.67 eV and 1.54 eV for AlN and Al

0.8125Sc

0.1875N, respectively, under N-rich conditions. Conversely, the neutral N-vacancy formation energies for pristine AlN and Al

0.8125Sc

0.1875N are 5.52 and 4.52 eV, respectively, for N-rich conditions. The values of neutral N-vacancy formation energies in pristine AlN for N-rich (5.52 eV) and Al-rich (2.75 eV) conditions are consistent with previous calculations on wurtzite Al

1−xSc

xN [

46]. These findings suggest that the formation energy of a N-vacancy in Sc-alloyed AlN is less than in pristine AlN for all charge states, irrespective of whether the system is under N- or Al-rich conditions. Thus, the formation of N vacancies in Al

1−xSc

xN is more energetically favorable than in AlN. Finally, the N-vacancy formation energy in Al

0.79Sc

0.21N for a nitrogen vacancy with one Sc nearest neighbor and a nitrogen vacancy with no Sc nearest neighbors is shown in

Figure 9c and

Figure 9d, respectively. The N vacancy with a Sc nearest neighbor exhibits a formation energy nearly 1 eV lower than the N vacancy with no Sc nearest neighbors. This preference can be attributed to the larger size of Sc atoms compared to Al atoms, as vacancies adjacent to Sc atoms help alleviate local strain and are energetically favored.

4. Discussion

One important consideration is the significantly lower than expected value of remanent polarization we measured in the sputtered Al

1−xSc

xN films. First, we emphasize that the remanent polarizations obtained through PUND measurements subtract out all leakage current contributions. To rationalize such low remanent polarization values, we considered a circuit model for a leaky ferroelectric thin film that includes one resistance in series with the ferroelectric material. We saw that the leakage current measured by PUND was approximately 40 µA for a 5 V pulse (

Figure 6e), which yields 1.25 × 10

5 Ω. This is a series resistance because it is obtained from the U (second) pulse of the PUND measurement, which has no contribution from the polarization current. When a voltage is applied to the leaky ferroelectric thin film, the current passing through the series resistance results in a voltage drop that reduces the electric field across the ferroelectric film in a similar way to a voltage divider. Because the leakage current is much larger than the polarization current, a larger fraction of the applied voltage will be dropped across the series resistance than across the ferroelectric film. As a result, the effective electric field across the ferroelectric film could be reduced by more than half. This is consistent with the observation that the observed remanent polarization is significantly muted.

Our results on the dependence of Al1−xScxN electrical properties on the film growth temperature are quite surprising. We observed increased electrical leakage in films with higher crystallinity (lower in-plane peak width in XRD RSM). This runs counter to expectations that films with higher crystallinity should exhibit a stronger ferroelectric response. Observations of point defect signatures (electrical conductivity Arrhenius dependence on growth temperature, SIMS, photoluminescence, and DFT) provide the missing explanation.

The equilibrium vacancy concentration in a crystal governed by thermodynamics follows an Arrhenius law and can be derived by balancing the configurational entropy gained from vacancies with their enthalpy of formation. In the case of Al1−xScxN films, the observed Arrhenius relationship between electrical conductivity and growth temperature indicates an apparent activation energy of 3.78 eV. Using this activation energy to calculate the vacancy concentration in the dilute regime yields a vacancy fraction of approximately 1.7 × 10−20 at 805 °C. This may not be the actual vacancy concentration because (1) the vacancies may not fully equilibrate at the growth temperature and (2) the change in vacancy concentration when the film naturally cools to room temperature could be kinetically controlled. Nevertheless, it is worth emphasizing that the range of N-vacancy formation energies calculated by DFT is in the range of several electron volts, which aligns with the observed electrical behavior and suggests a connection between vacancy formation and the electrical properties of the material.

Although we were unable to directly measure vacancy concentrations, several experiments provide supporting evidence for the involvement of nitrogen vacancies in the electrical conduction of Al

1−xSc

xN. First, the observed dielectric breakdown behavior closely resembles previous reports of electrical conduction induced by nitrogen vacancies [

47]. Second, bulk composition measurements using STEM-EDS indicate a nitrogen deficiency in the film/buffer/substrate system consistent with the presence of nitrogen vacancies in either the Al

1−xSc

xN film [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], the TiN buffer [

48], or, potentially, both layers. Finally, the SIMS data indicate an increased Ti concentration in the Al

1−xSc

xN films as a function of growth temperature. We know that the proximity of N vacancies to Sc atoms reduces the vacancy formation energy, which is consistent with an argument based on atomic radius [

49]. Assuming the same applies for the presence of trace Ti, which has a similar atomic size to Sc (they are adjacent in the periodic table), the increased Ti concentration can also lead to an increased N-vacancy concentration due to vacancy-impurity binding. We noted that compared to other characterization methods such as EDS, SIMS has a detection threshold that is significantly lower (~10

16 cm

−3) [

50]. Because point defect concentrations are typically very low, this makes SIMS uniquely well suited for their characterization due to the sensitivity of the measurement. Note that while a DFT simulation including trace Ti is possible, the system size required would be too large—therefore, we offer, instead, a conjecture based on a physical argument rooted in atomic size. Collectively, the data are consistent with electrical conduction in the Al

1−xSc

xN films that is dominated by N vacancies.

We observed the ferroelectric response in Al

1−xSc

xN films with electrical conductivities spanning several orders of magnitude. While recent results showing a positive correlation between the rocking curve full width at half maximum (FWHM) and electrical leakage in Al

1−xSc

xN films [

51] suggest that improved crystallinity could lead to increased ferroelectric response, our results present a contrasting perspective. Specifically, the epitaxial films grown at 805 °C and 655 °C exhibit significantly higher electrical leakage and weaker ferroelectric response, as measured by PFM, compared to the films grown at 624 °C, 555 °C, and 446 °C. While we note that piezoelectric materials that are not ferroelectric also exhibit piezoresponse, they do not support nonzero strains and polarizations in the absence of an external electric field. Thus, changes in piezoresponse arising from DC poling PFM experiments verify that Al

1−xSc

xN films exhibit behavior consistent with remanent polarization in a ferroelectric material. In order to rationalize this observation, it is crucial to consider that many prior studies on ferroelectric Al

1−xSc

xN films have dealt with columnar nanocrystals grown at similar temperatures (near 300 °C) to satisfy back-end-of-line (BEOL) integration requirements [

52]. In this context, slight deviations from that growth regime may not necessarily result in substantial alterations in nitrogen-vacancy concentrations. Conversely, electrical conduction in those polycrystal films may still be affected by nitrogen vacancies. In the current study, film thickness effects were not considered. In general, electrical leakage increases as Al

1−xSc

xN film thickness decreases [

53]. By exploring a wide range of growth temperatures, our study highlights that the concentration of N vacancies (or other point defects) may play an important role in the determination of electrical properties, overshadowing the influence of crystallinity. The data are consistent with enhanced leakage at higher growth temperatures arising primarily from thermally activated formation of point defects such as nitrogen vacancies. These results underscore the importance of addressing and minimizing detrimental point defects in Al

1−xSc

xN as a crucial step toward achieving enhanced performance in ferroelectric devices.