Measuring Students’ Satisfaction on an XAI-Based Mixed Initiative Tutoring System for Database Design

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

- What are the challenges faced by students in designing ERDs?

- 2.

- Will the mixed-initiative approach improve the explanation and reasoning modules in ERD-PRO?

- 3.

- What are the perceptions of students about ERD-PRO’s features related to explanation and reasoning?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intelligent Tutoring System for Database

2.2. Explainable AI (XAI)

2.3. XAI and ITS

- Why explanations: describing the reasons a particular hint was given (e.g., why the student was classified as a “lower learner” at that point).

- How explanations: describing the processes to generate the hint (e.g., how the system scored user behavior and ranked possible hints).

- Why am I delivered this hint? → explained the user’s classification and related behaviors.

- Why am I predicted to be lower learning? → linked the student’s actions to specific rules and weights.

- How was my hint chosen? → showed the ranking process among candidate hints.

2.4. Research Gap

3. Research Methodology

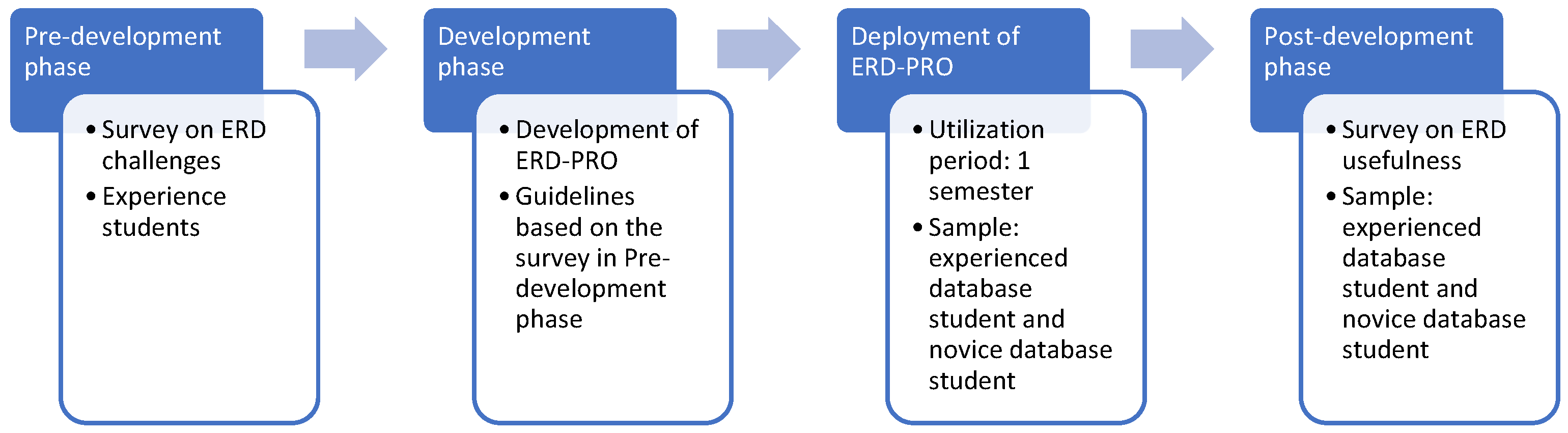

3.1. Theoretical or Conceptual Framework

3.2. Participant’s Sampling

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Analysis

3.5. Survey Instrument

3.6. Survey Content

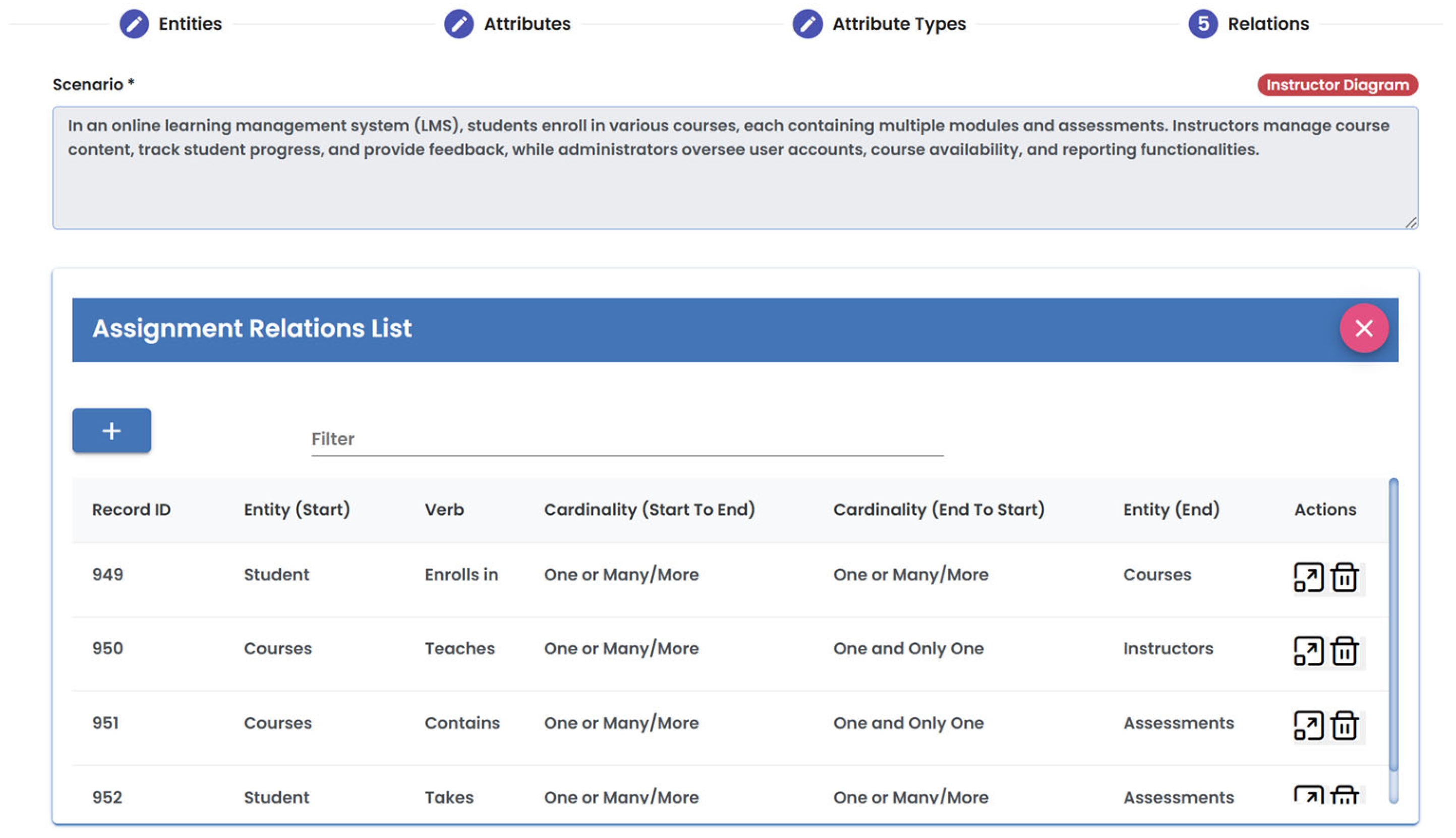

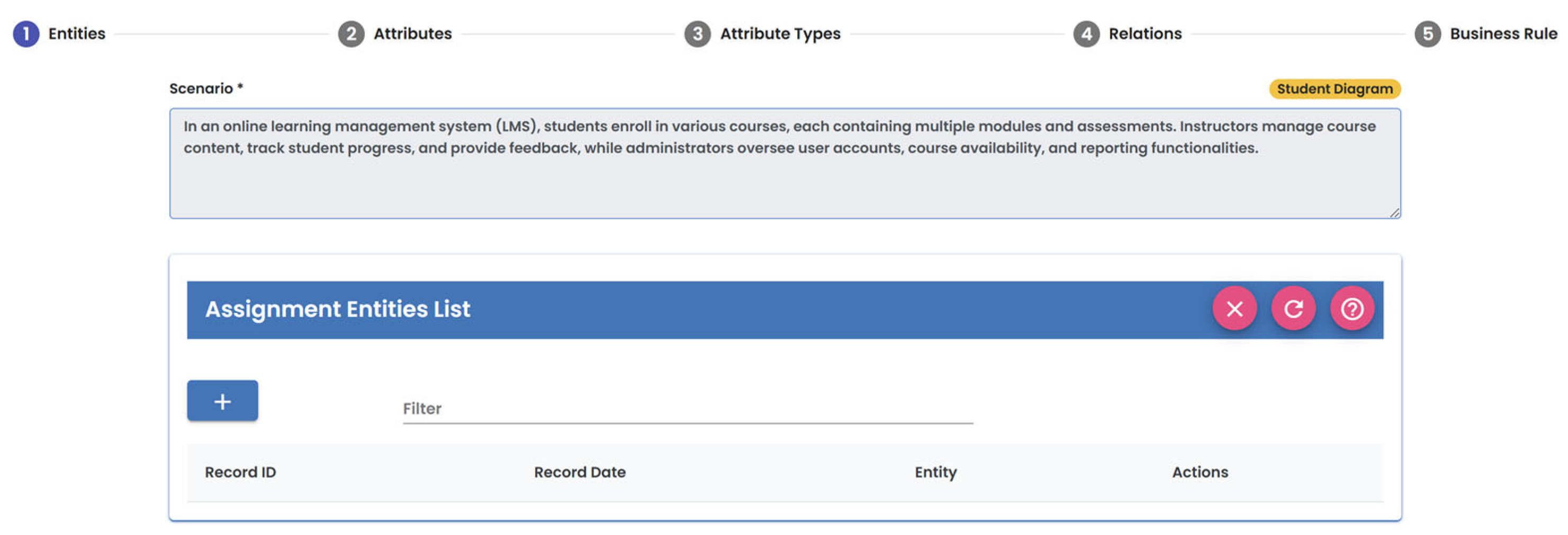

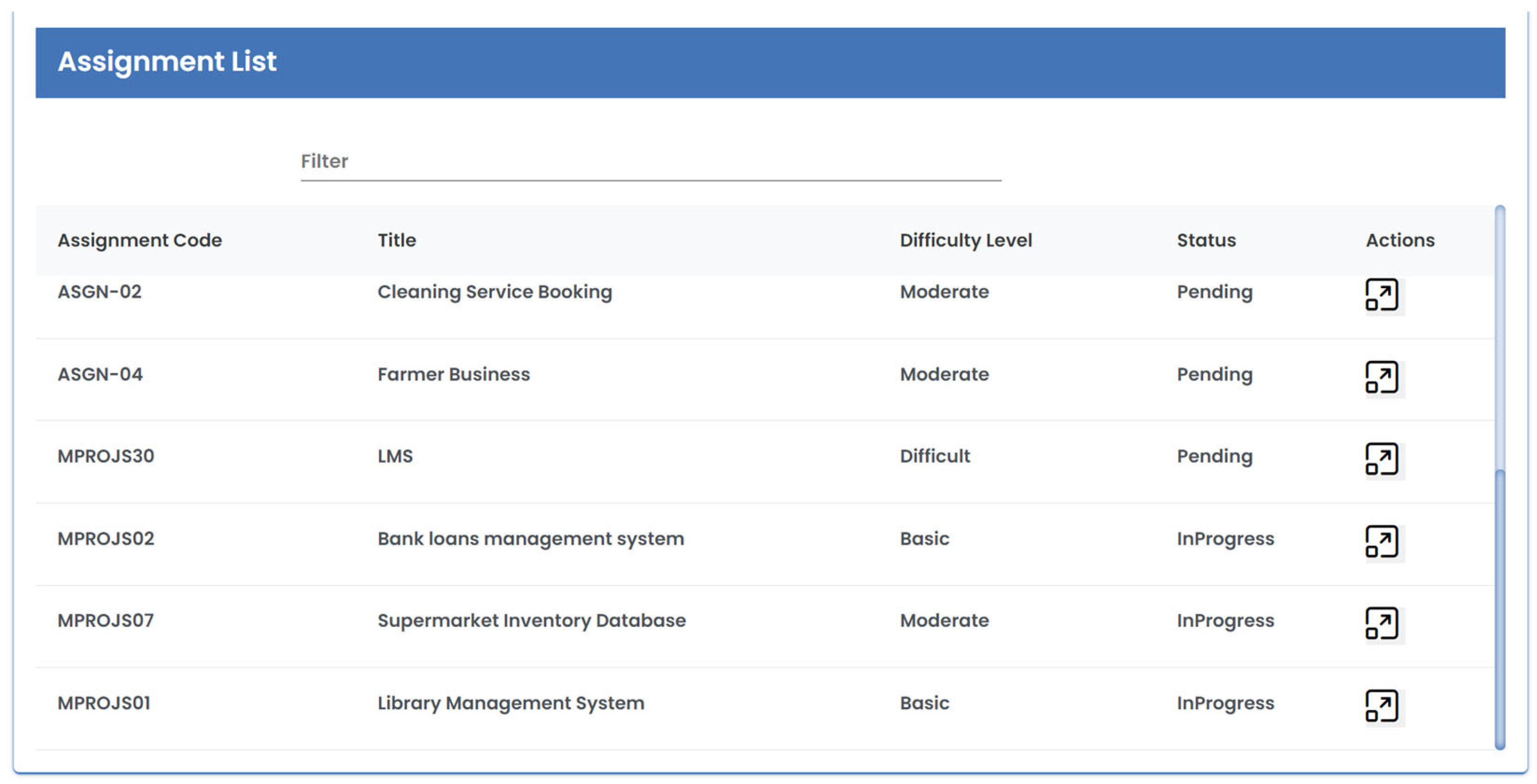

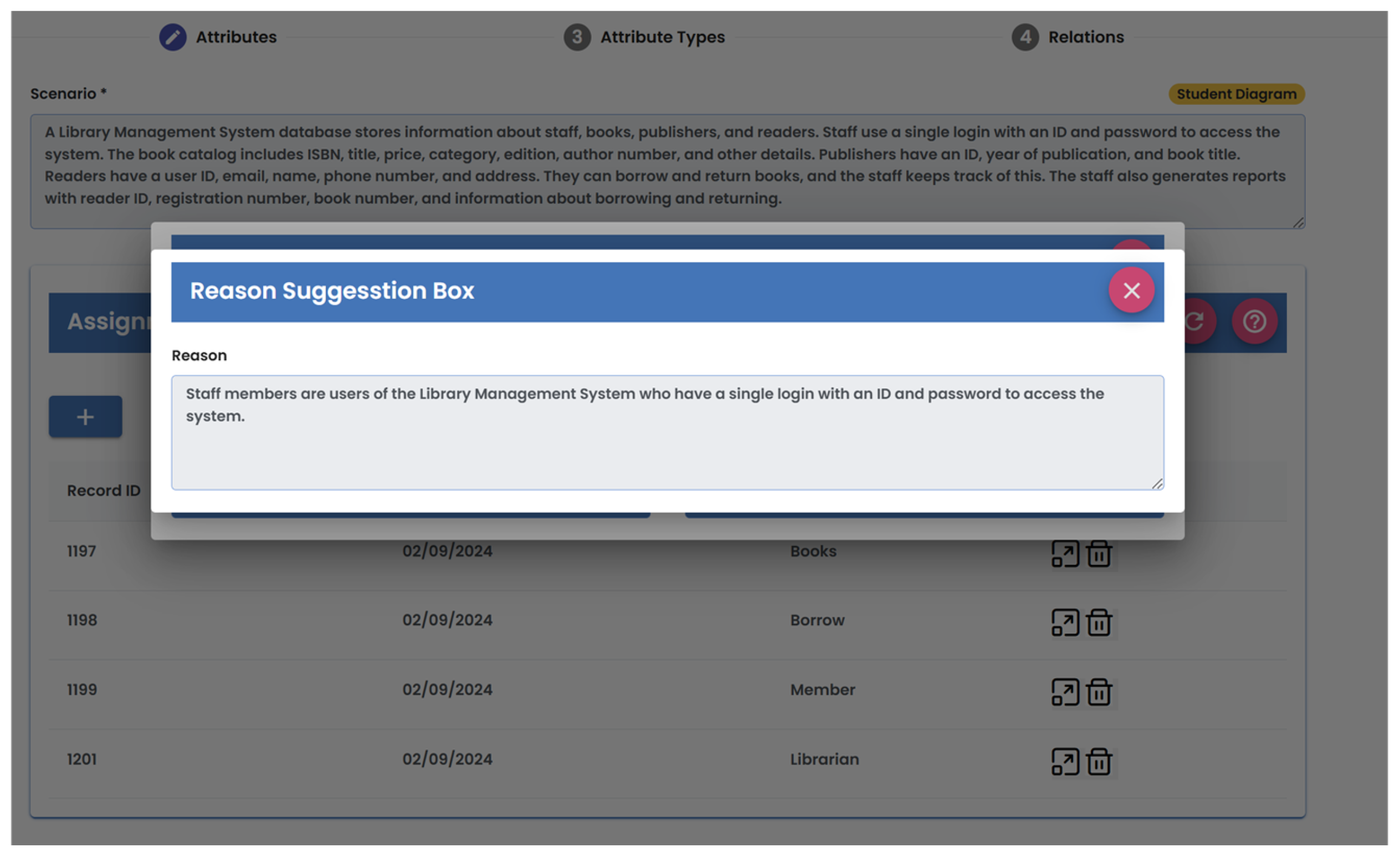

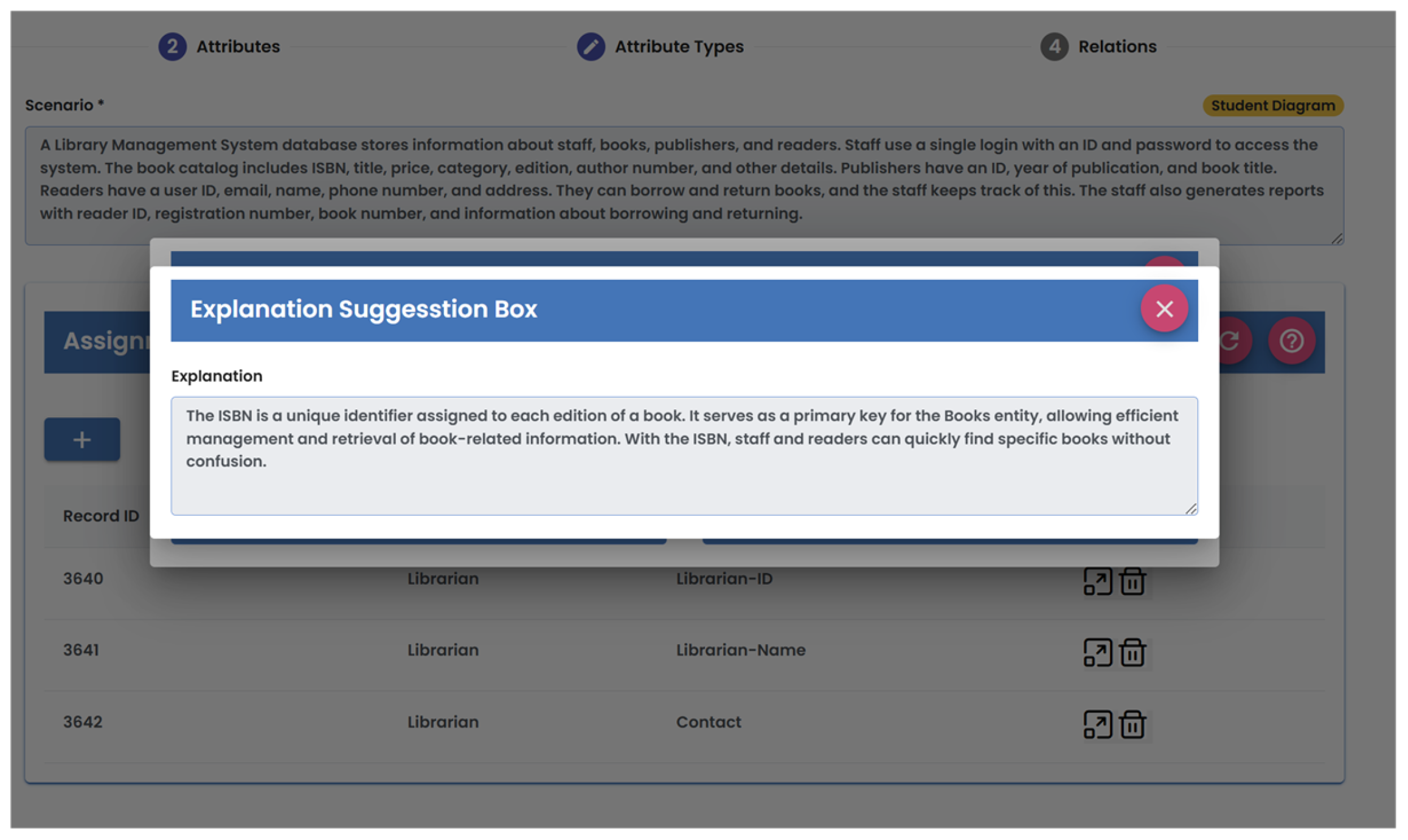

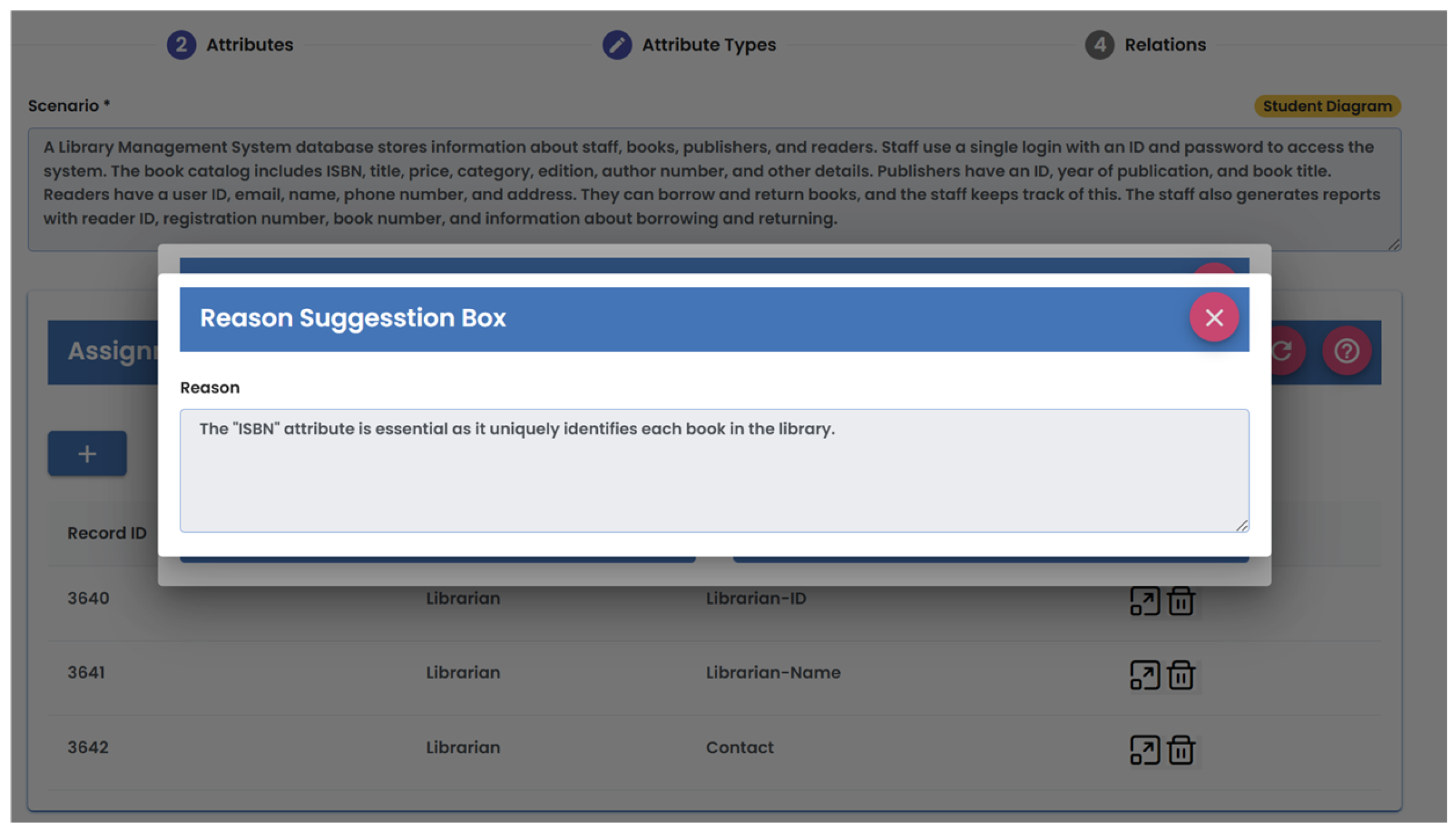

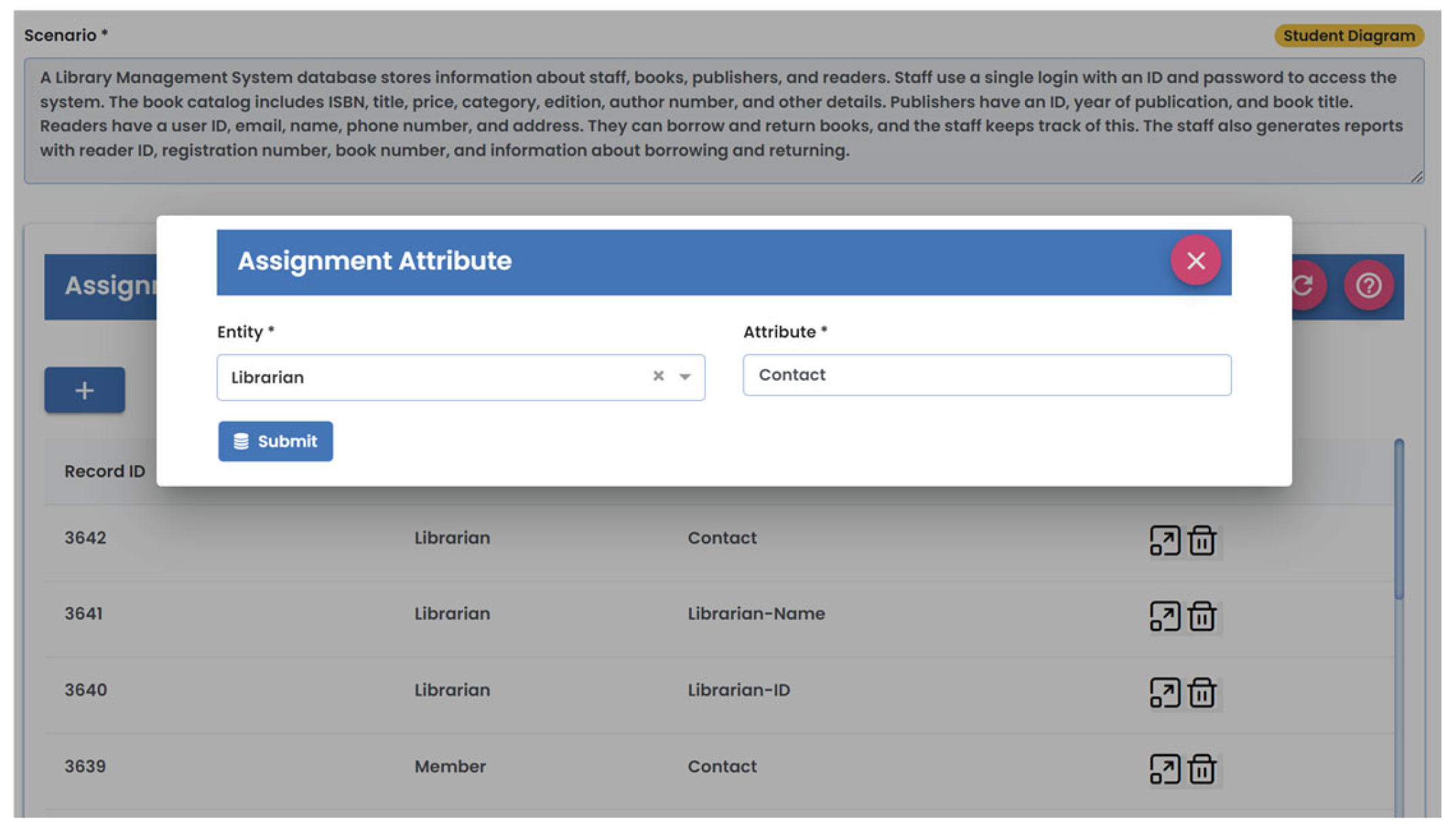

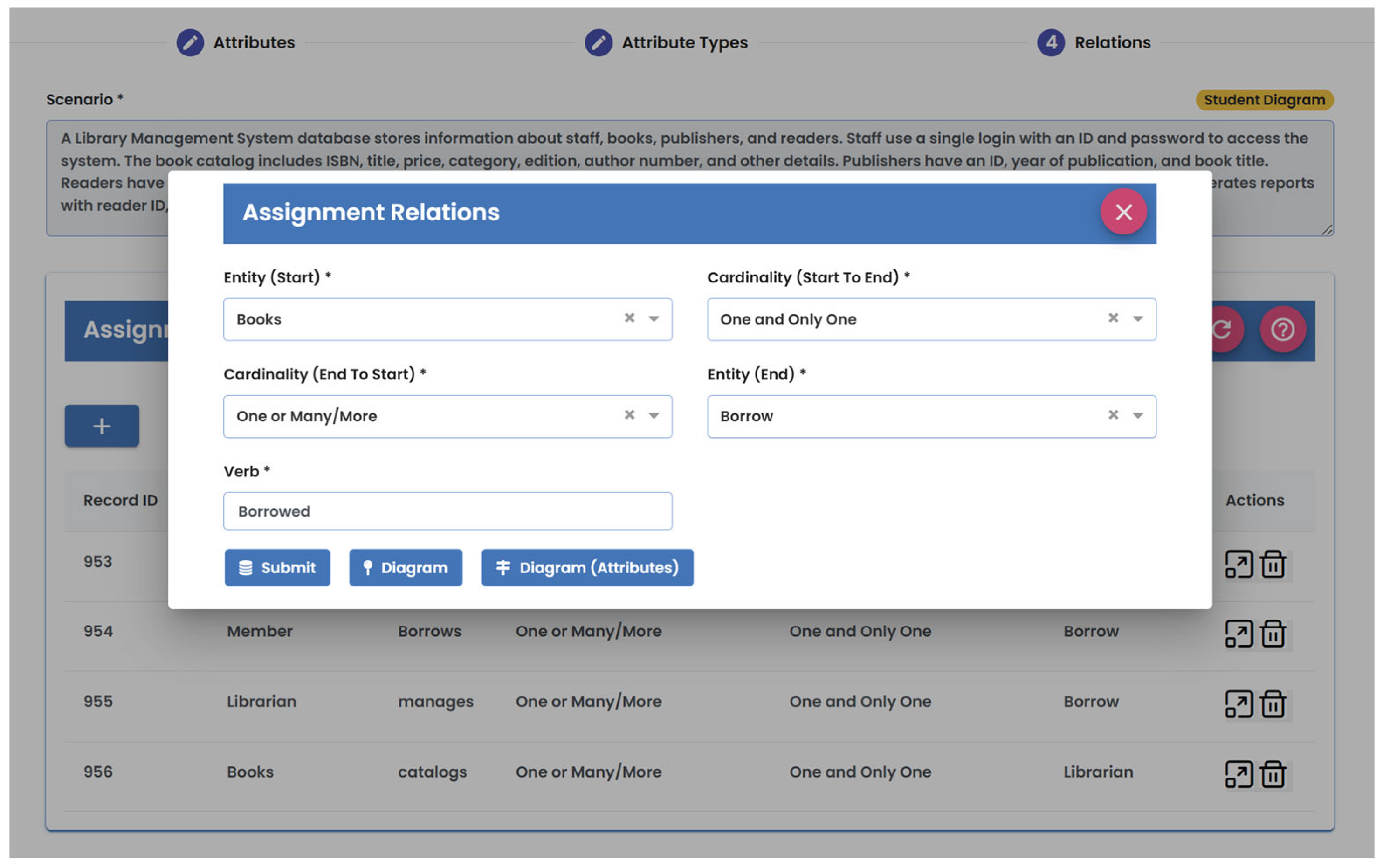

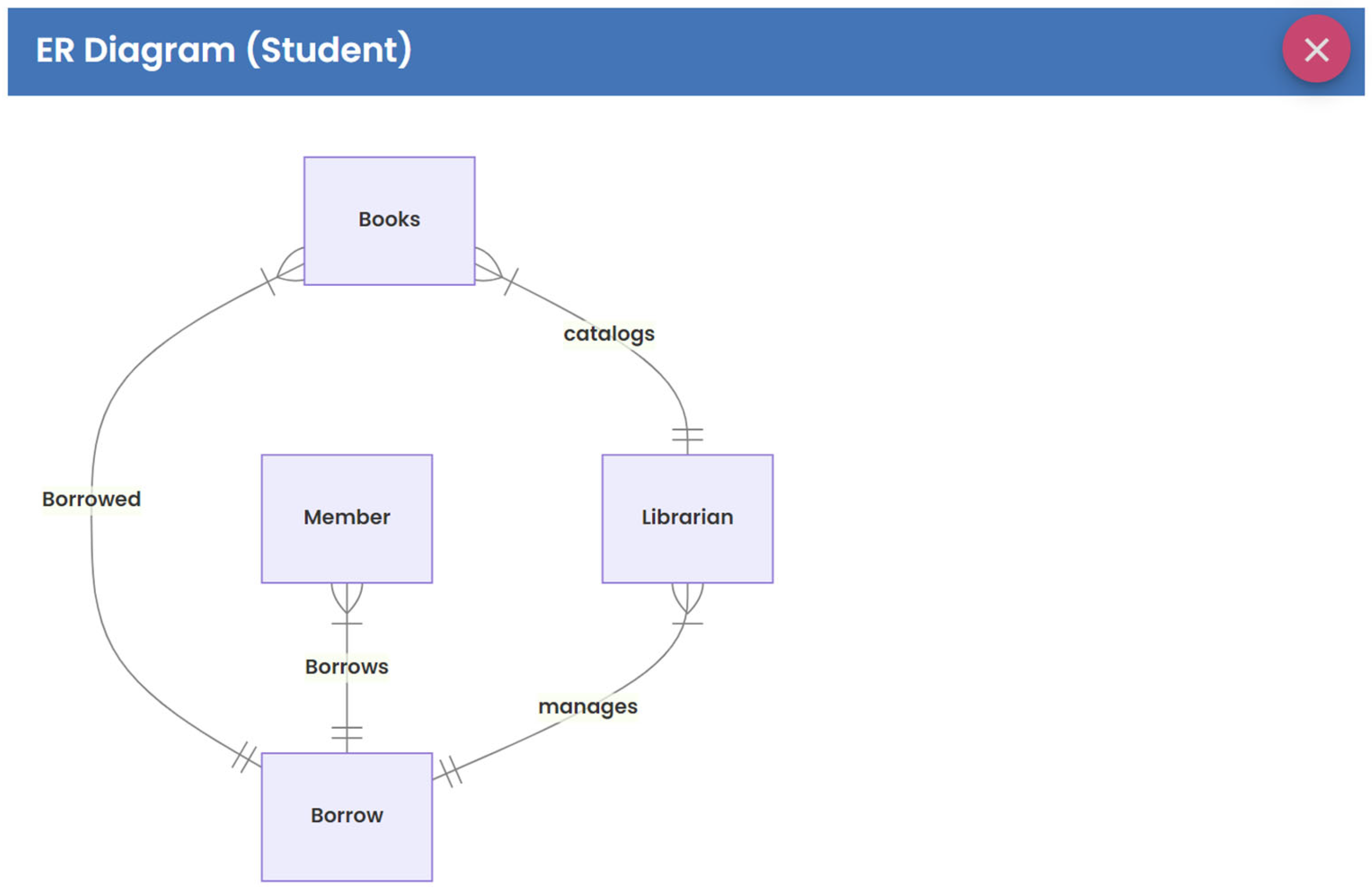

4. ERD-PRO

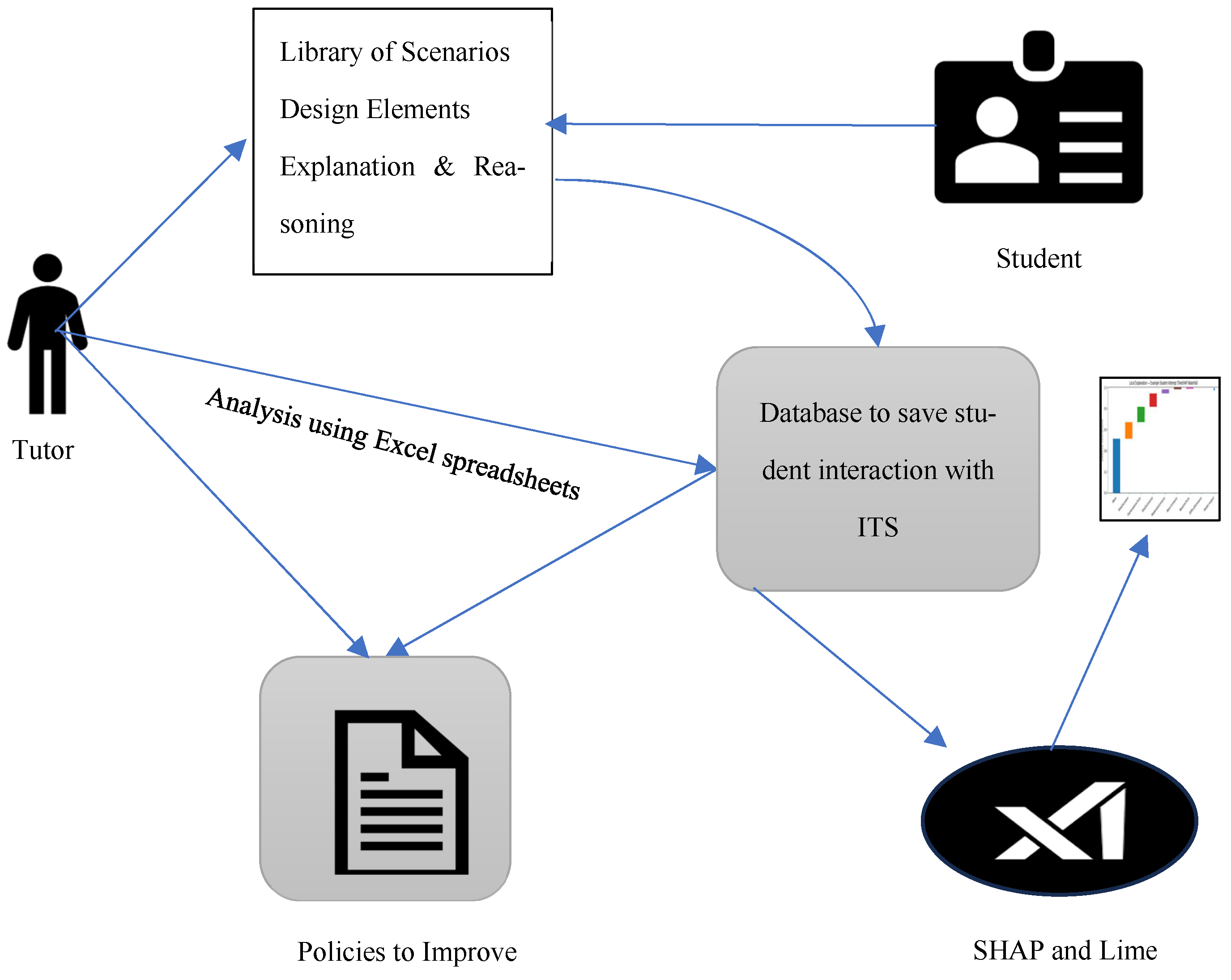

ERD-PRO Framework with XAI Concept

5. Research Findings and Discussion

5.1. Pre-Development Survey

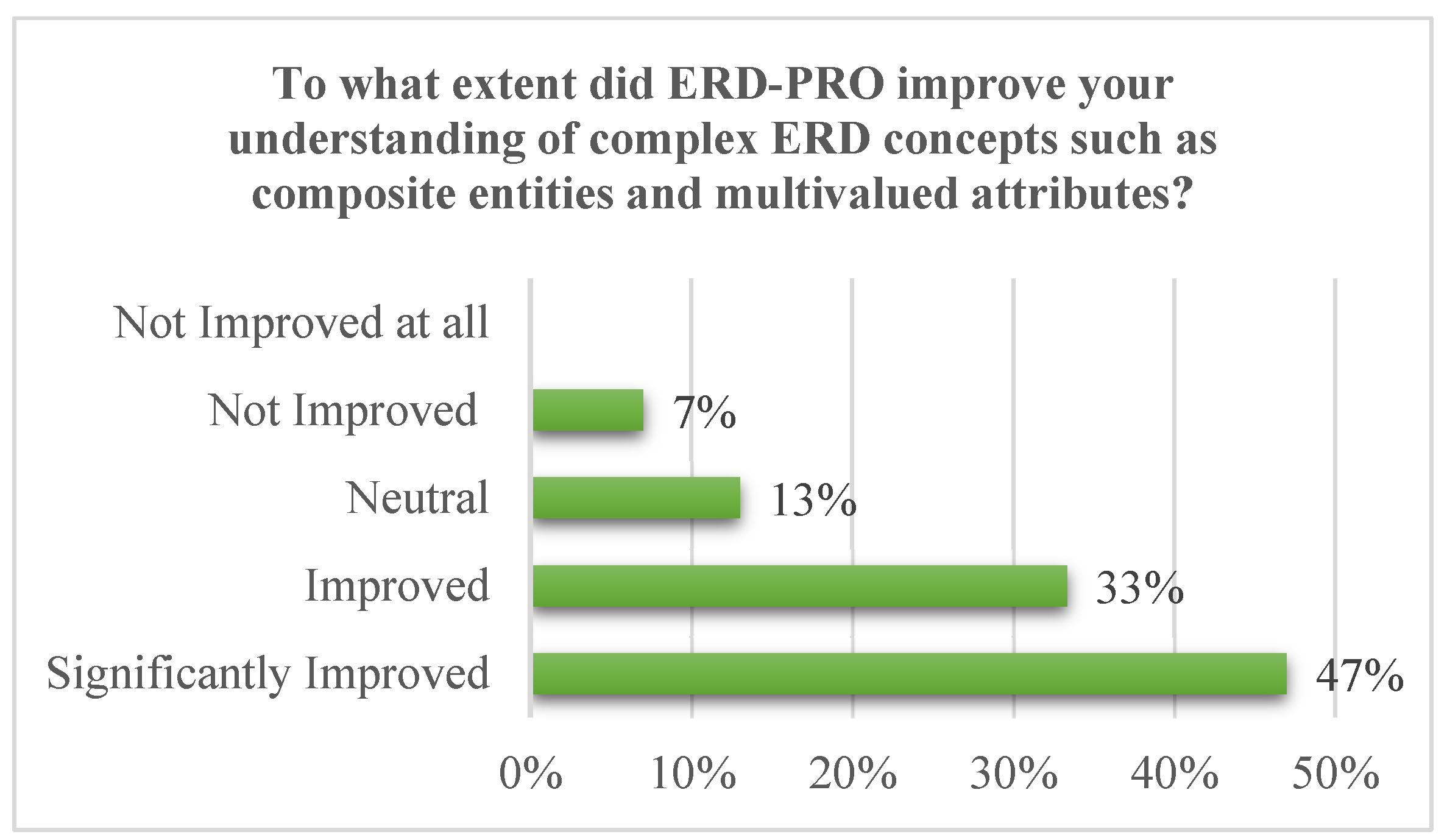

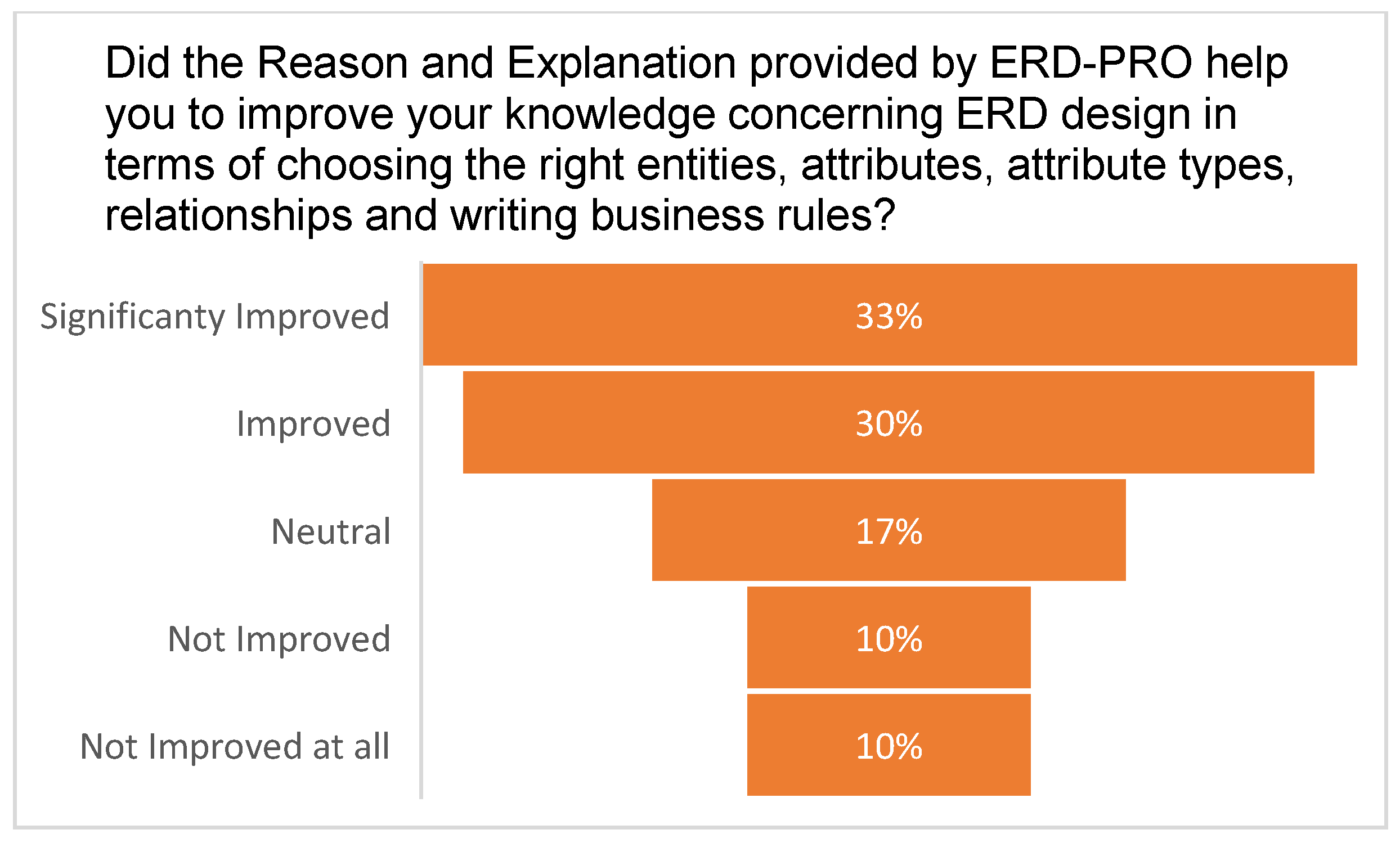

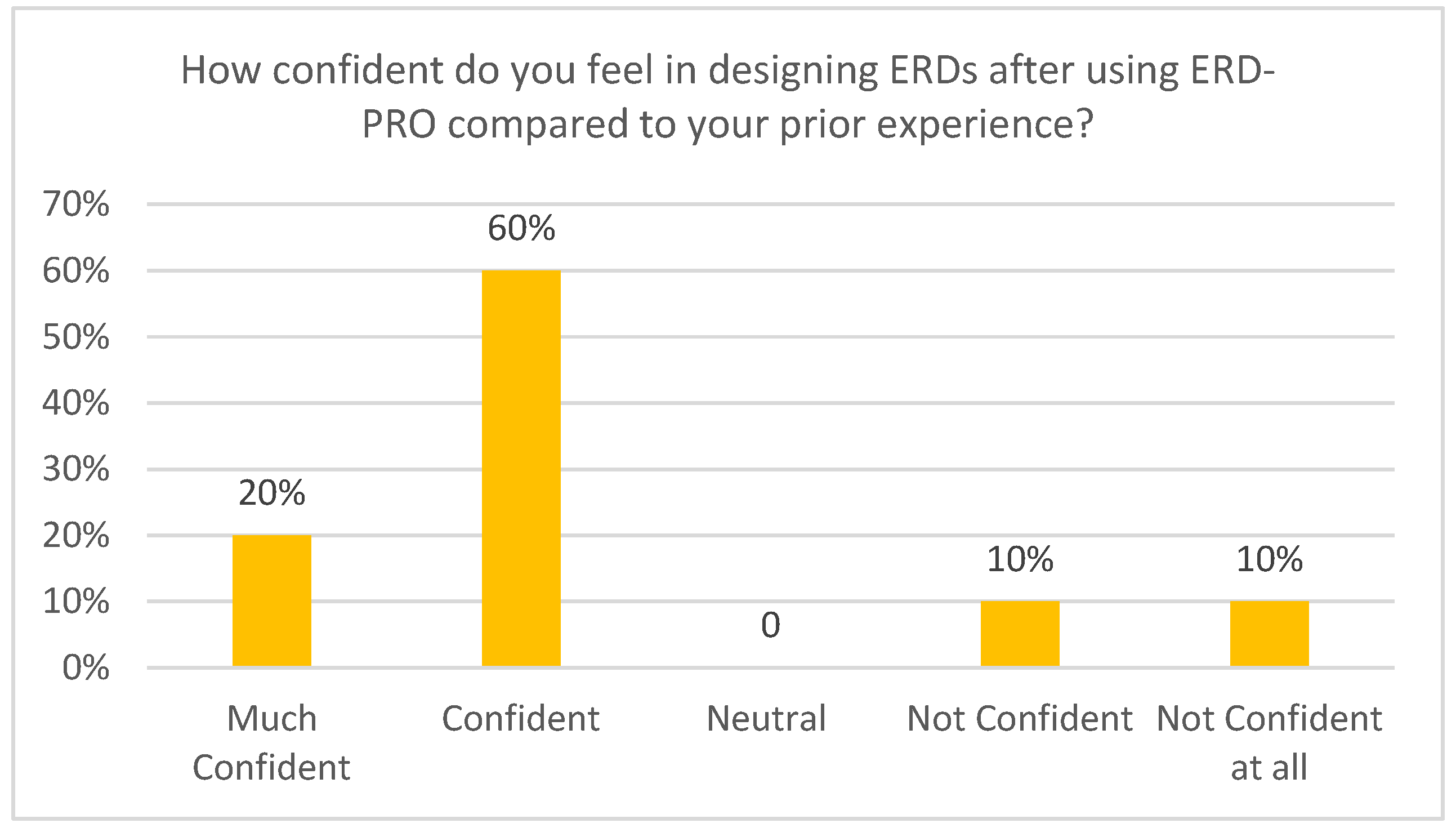

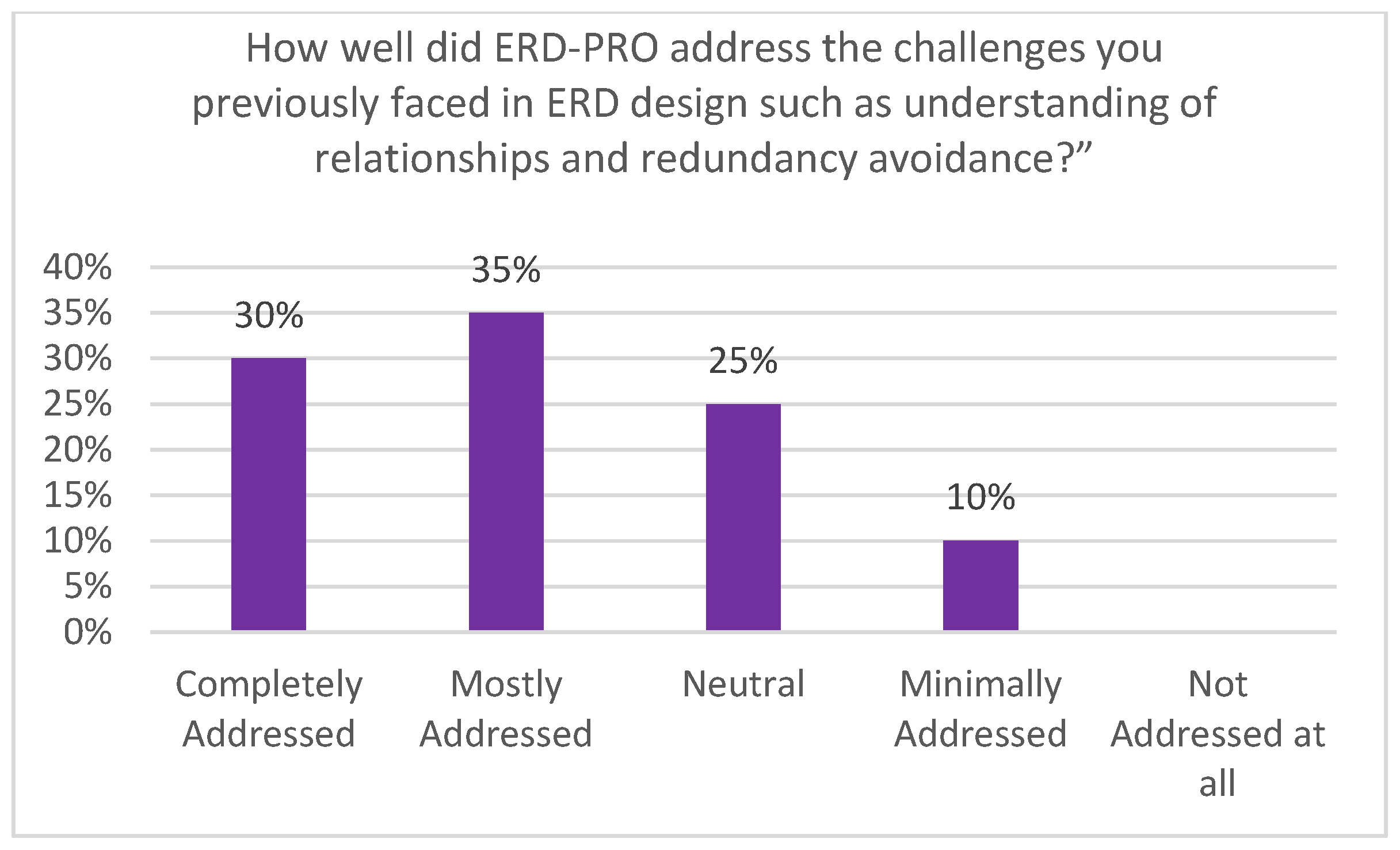

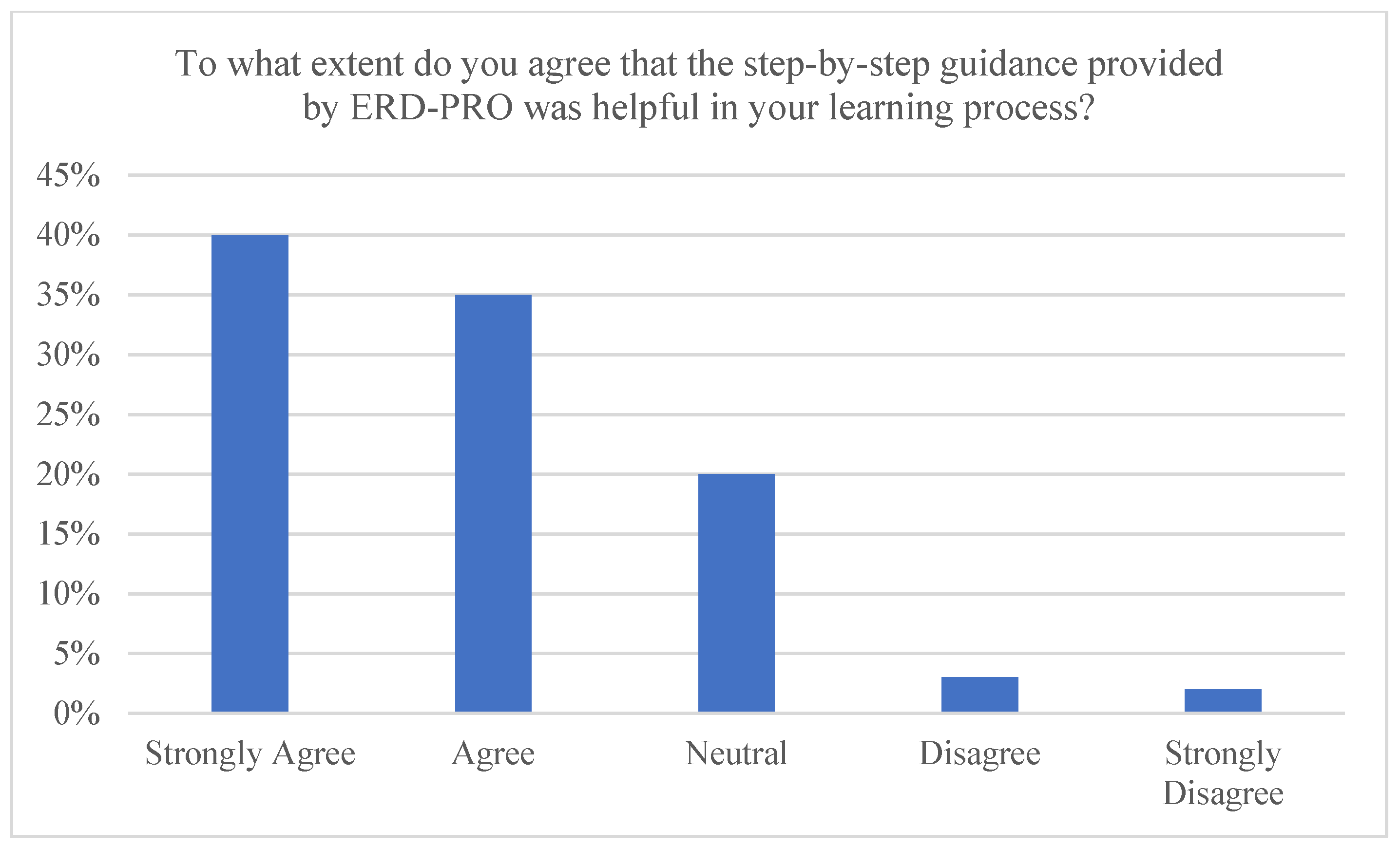

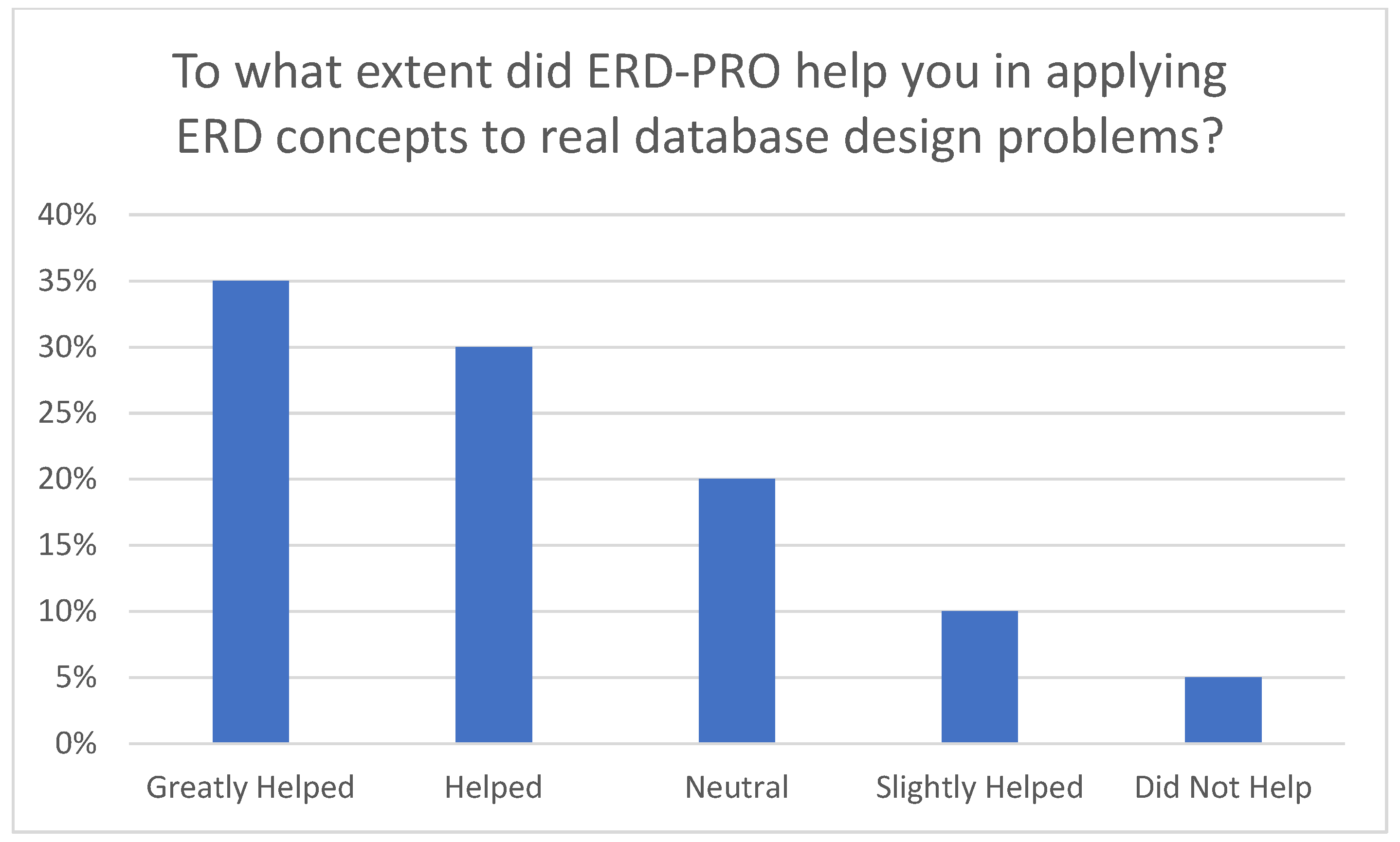

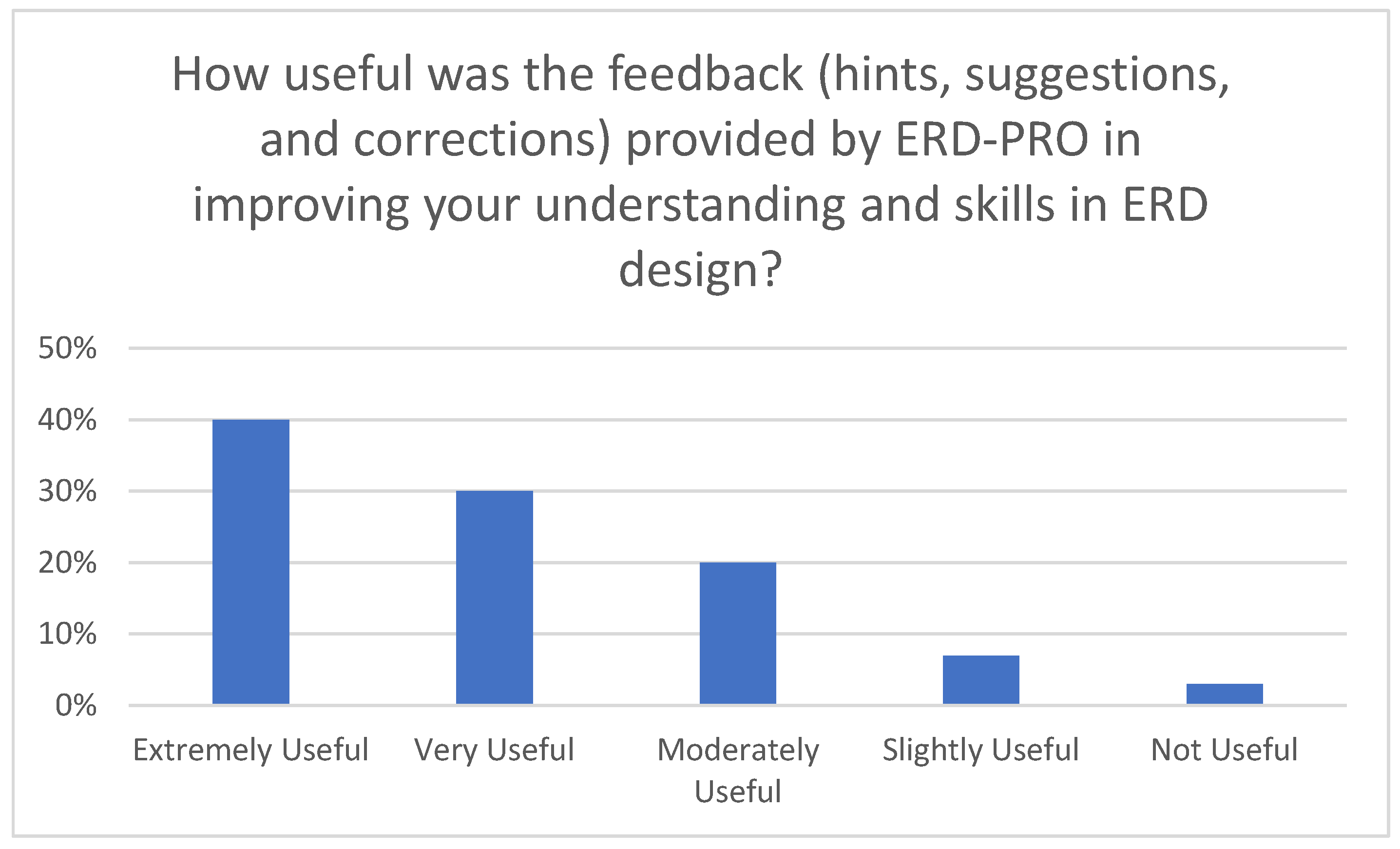

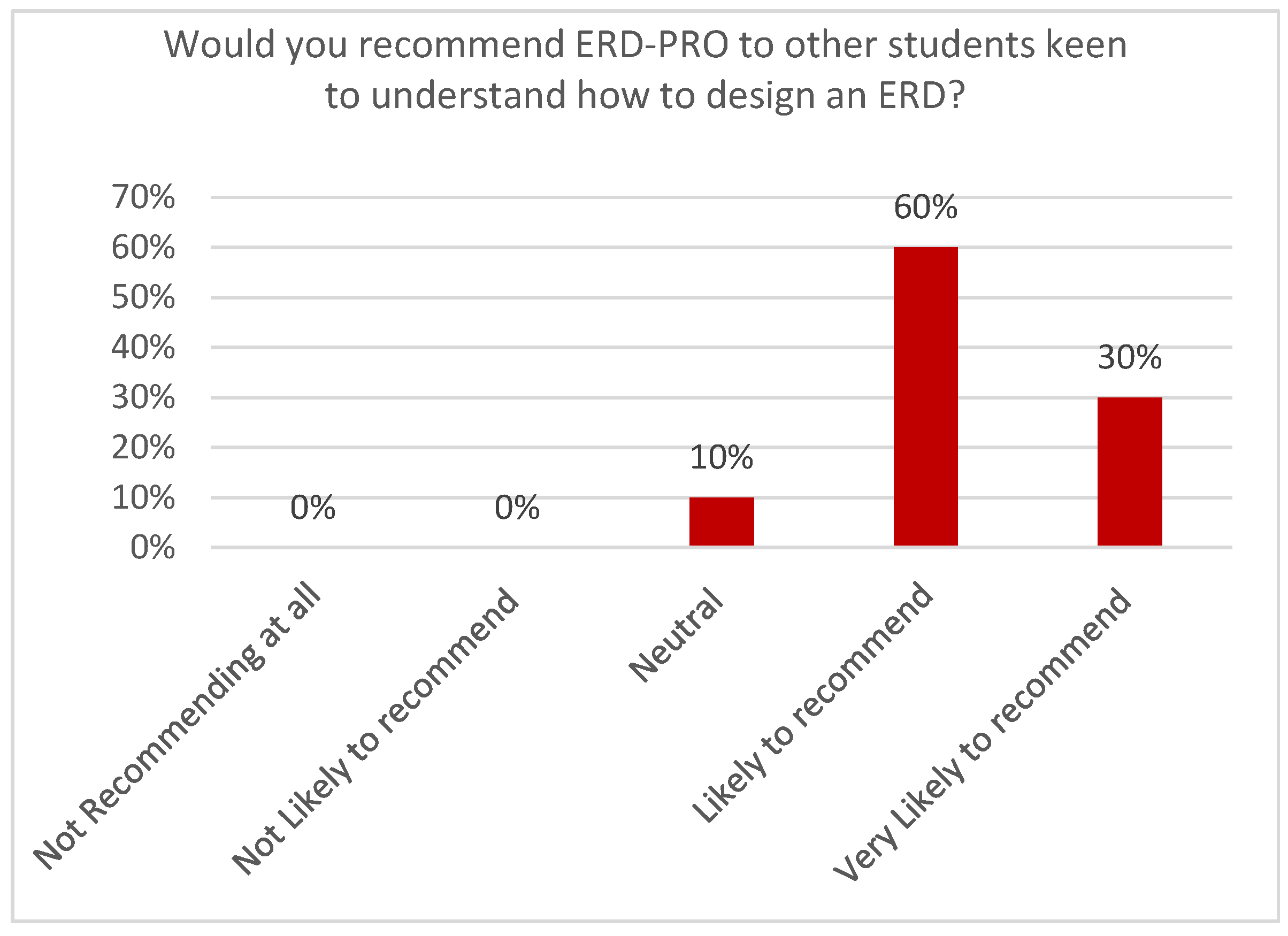

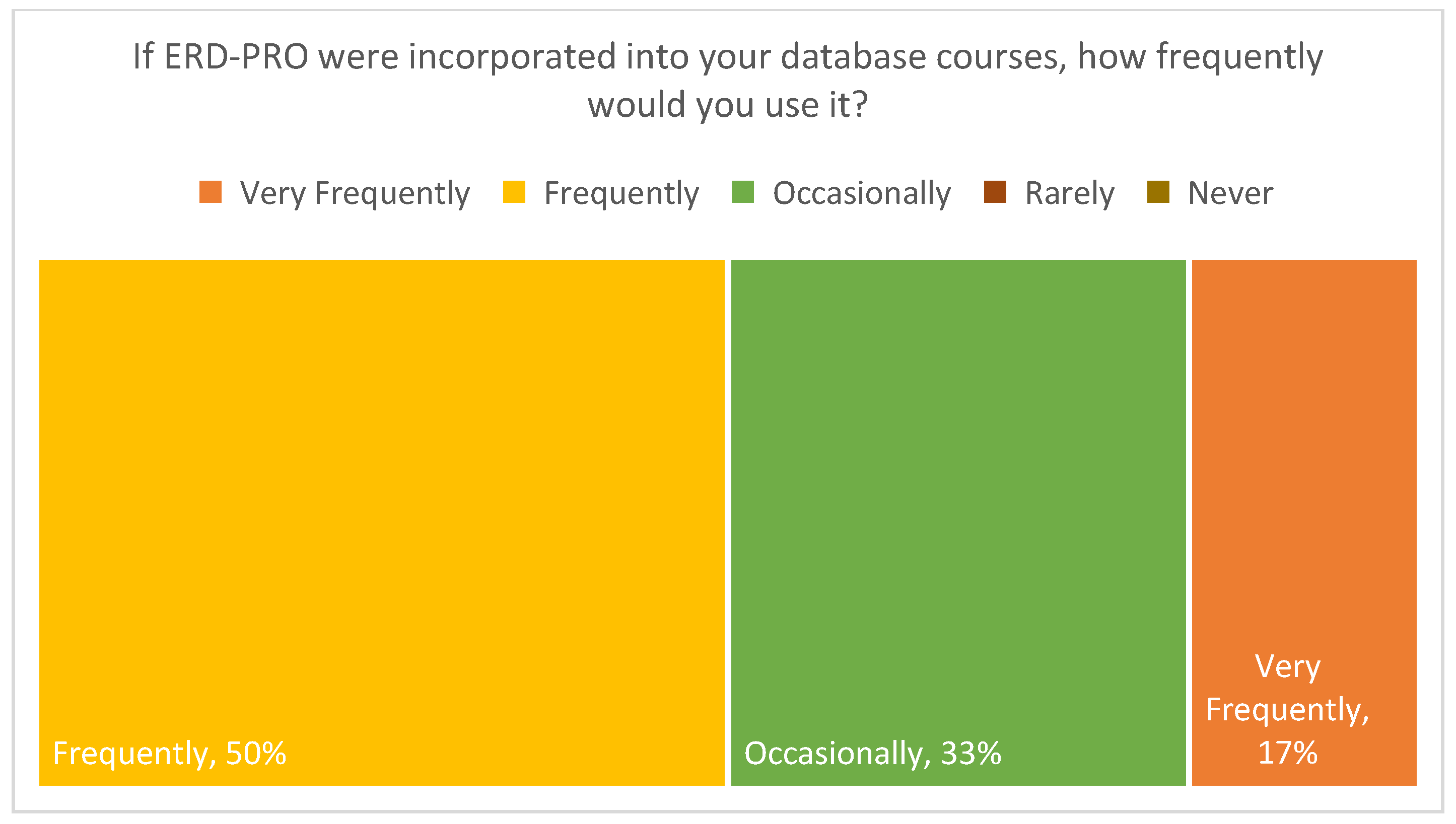

5.2. Post-Development Findings

6. Implications for Practitioners

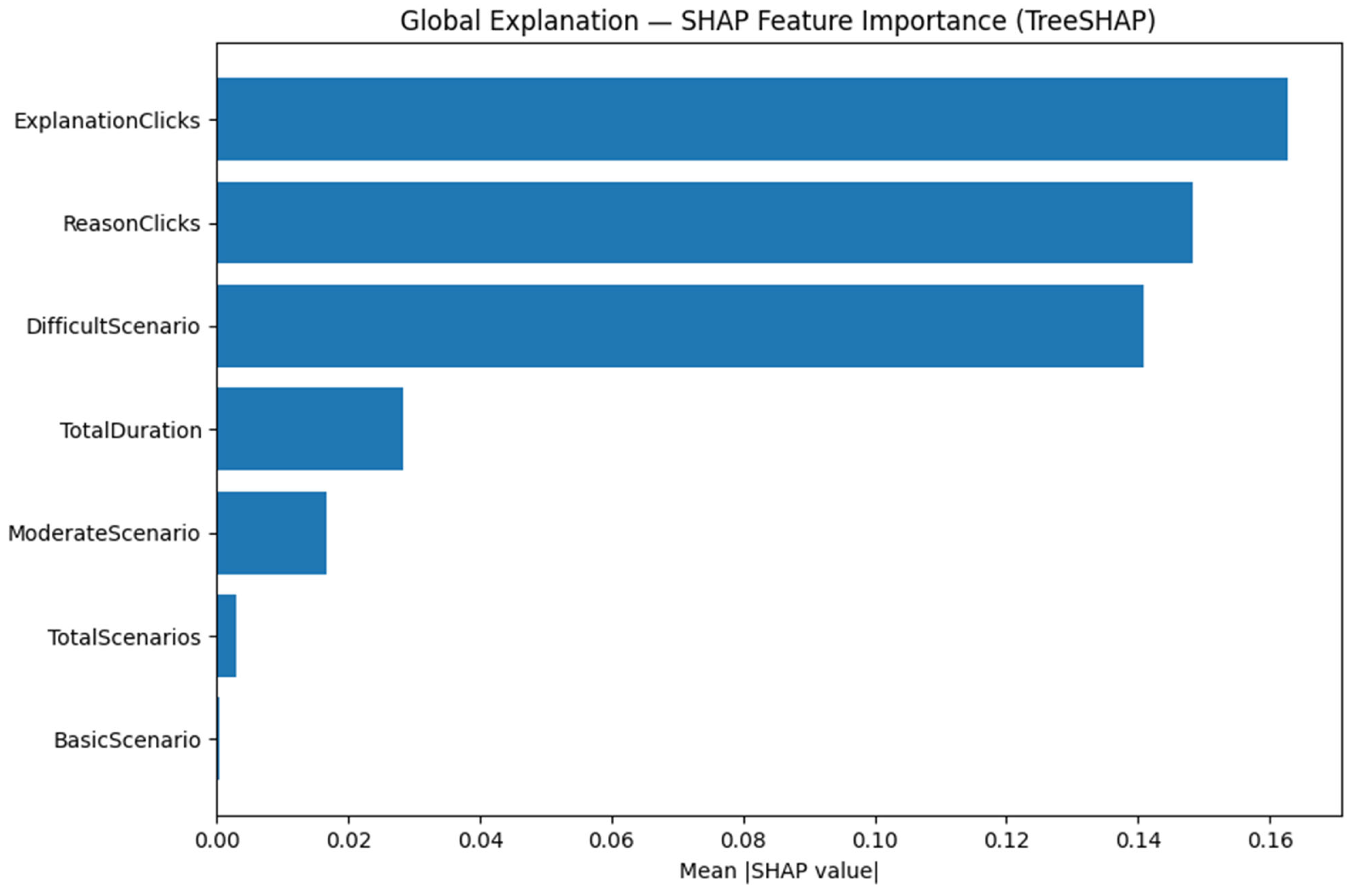

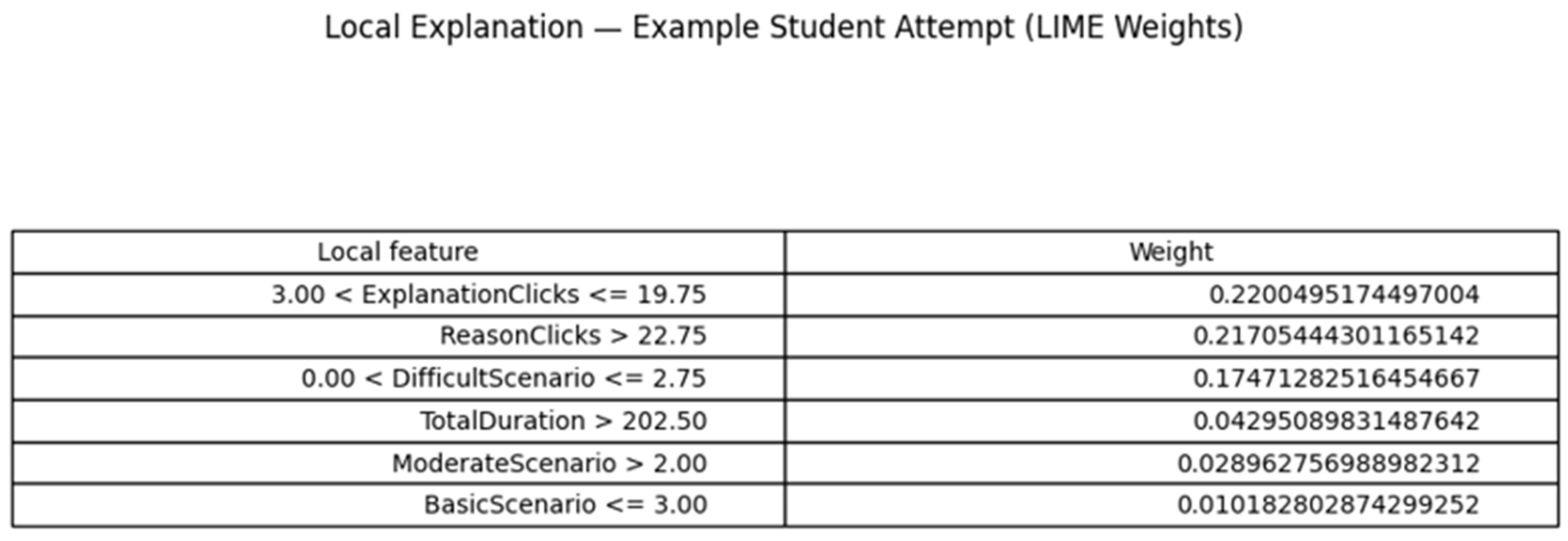

6.1. Student Activities and XAI Interpretation

6.2. XAI Interpretation

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

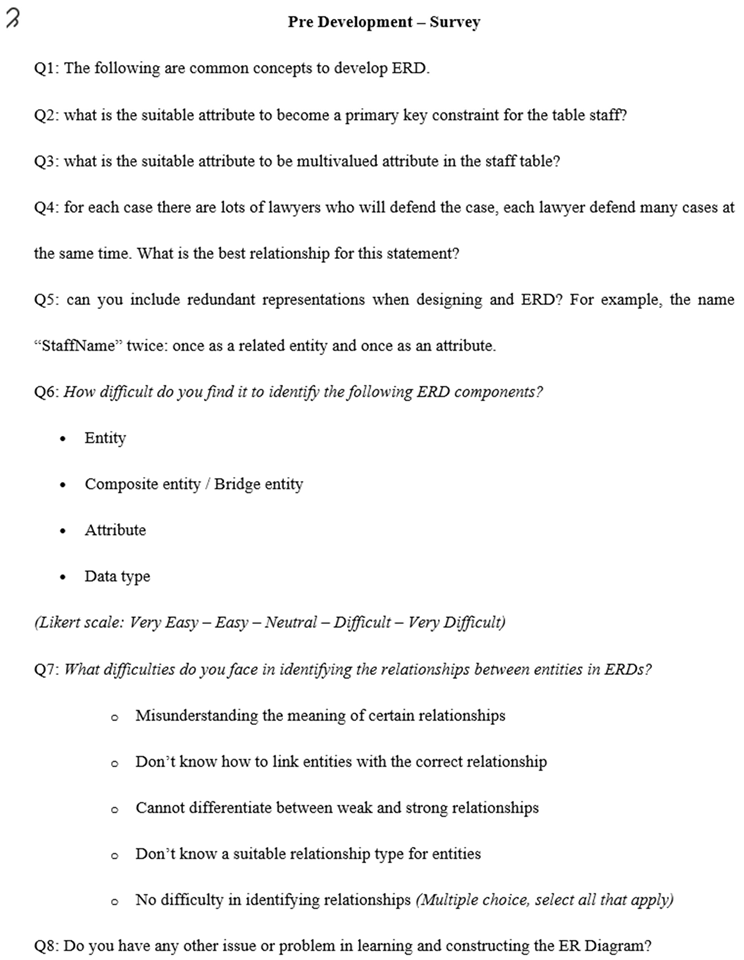

Appendix A. Pre-Development Survey

Appendix B. Post-Development Survey

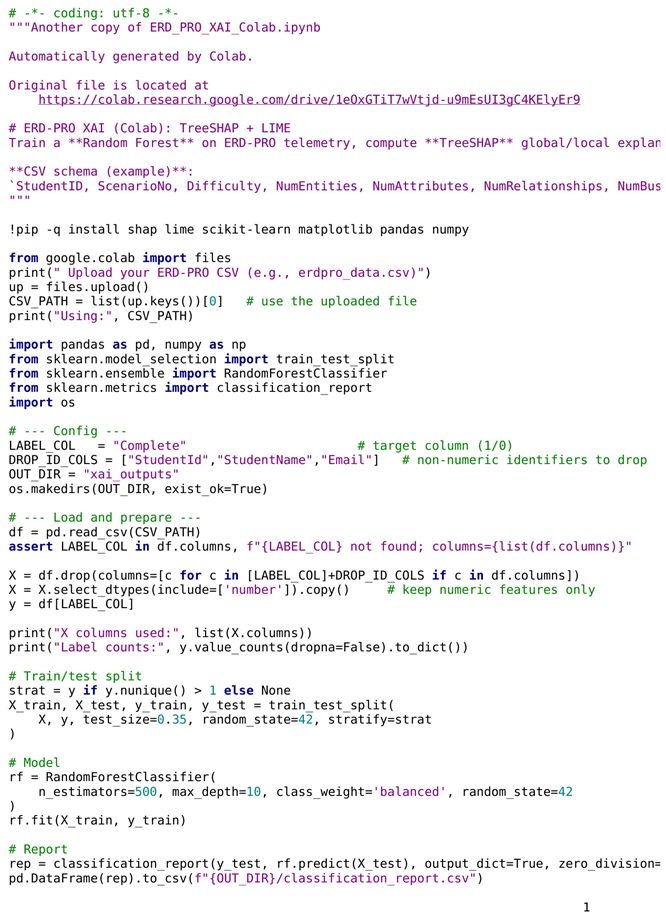

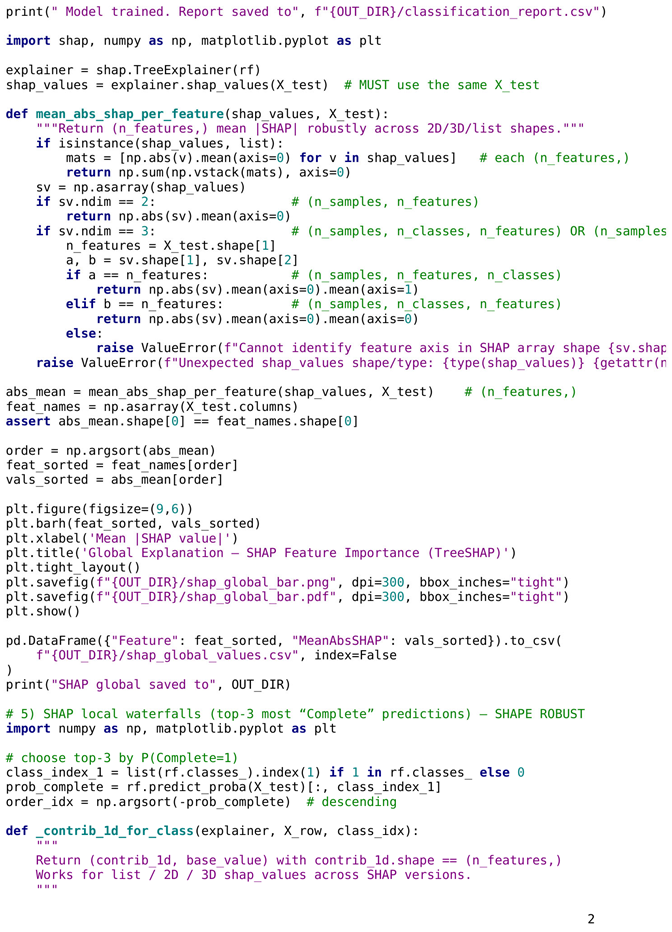

Appendix C. XAI Source Code for SHAP and LIME

References

- Mousavinasab, E.; Zarifsanaiey, N.; Kalhori, S.R.N.; Rakhshan, M.; Keikha, L.; Ghazi Saeedi, M. Intelligent Tutoring Systems: A Systematic Review of Characteristics, Applications, and Evaluation Methods. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2021, 29, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeksha, S.M. Database Management System and Types of Build Architecture. Math. Stat. Eng. Appl. 2022, 71, 1380–1388. Available online: https://www.philstat.org/index.php/MSEA/article/view/630 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Hingorani, K.; Gittens, D.; Edwards, N. Reinforcing database concepts by using entity relationships diagrams (erd) and normalization together for designing robust databases. Issues Inf. Syst. 2017, 18, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, A. An Intelligent SQL Tutor on the Web. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Ed. 2003, 13, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.; Zachary, W. Intelligent Tutoring for Team Training: Lessons Learned from US Military Research. In Research on Managing Groups and Teams; Johnston, J., Sottilare, R., Sinatra, A.M., Shawn Burke, C., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2018; Volume 19, pp. 215–245. ISBN 978-1-78754-474-1. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, R.M.; Lima, R.M.; Mesquita, D. Teacher Competences for Active Learning in Engineering Education. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcael, E.; Garcés, G.; Bastías, E.; Friz, M. Theory of Teaching Techniques Used in Civil Engineering Programs. J. Prof. Issues Eng. Educ. Pract. 2019, 145, 02518008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Y.-L. Entity-Relationship Diagram. In Modeling and Analysis of Enterprise and Information Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 125–139. ISBN 978-3-540-89555-8. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L. The Effect of MySQL Workbench in Teaching Entity-Relationship Diagram (ERD) to Relational Schema Mapping. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 2016, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D. IEEE VIS 2021 Virtual: A Mixed-Initiative Approach to Reusing Infographic Charts. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2021, 28, 173–183. Available online: https://virtual-staging.ieeevis.org/year/2021/paper_v-full-1637.html (accessed on 24 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Pister, A.; Buono, P.; Fekete, J.-D.; Plaisant, C.; Valdivia, P. Integrating Prior Knowledge in Mixed Initiative Social Network Clustering. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 27, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelikyürek, H.; Karakuş, K.; Aygün, T.; Taş, A. Database Usage and Its Importance in Livestock. Manas J. Agric. Vet. Life Sci. 2019, 9, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, A.; Eng, N. Database Design, 2nd ed.; The BC Open Textbook Project: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rashkovits, R.; Lavy, I. Mapping Common Errors in Entity Relationship Diagram Design of Novice Designers. Int. J. Database Manag. Syst. 2021, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavana, M. Enterprise Information Systems and the Digitalization of Business Functions. In Advances in Business Information Systems and Analytics; IGI Global: Palmdale, PA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5225-2382-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rashkovits, R.; Lavy, I. Students’ Difficulties in Identifying the Use of Ternary Relationships in Data Modeling. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Educ. 2020, 16, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, A.; Subhashini, R. A Systematic Review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence Models and Applications: Recent Developments and Future Trends. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 7, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShaikh, F.; Hewahi, N. AI and Machine Learning Techniques in the Development of Intelligent Tutoring System: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), Zallaq, Bahrain, 29–30 September 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, S.B.; Dorneich, M.C.; Walton, J.; Winer, E. Five Lenses on Team Tutor Challenges: A Multidisciplinary Approach. In Research on Managing Groups and Teams; Johnston, J., Sottilare, R., Sinatra, A.M., Shawn Burke, C., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2018; Volume 19, pp. 247–277. ISBN 978-1-78754-474-1. [Google Scholar]

- Clancey, W.J.; Hoffman, R.R. Methods and Standards for Research on Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Lessons from Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Appl. AI Lett. 2021, 2, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, H.; Shum, S.B.; Chen, G.; Conati, C.; Tsai, Y.-S.; Kay, J.; Knight, S.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Sadiq, S.; Gašević, D. Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Education. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Chu, X.; Chai, C.S.; Jong, M.S.Y.; Istenic, A.; Spector, M.; Liu, J.-B.; Yuan, J.; Li, Y. A Review of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education from 2010 to 2020. Complexity 2021, 2021, 8812542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunning, D.; Aha, D.W. DARPA’s Explainable Artificial Intelligence Program. AI Mag. 2019, 40, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmadani, M.; Mitrovic, A.; Weerasinghe, A.; Neshatian, K. Investigating Student Interactions with Tutorial Dialogues in EER-Tutor. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2015, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, P.; Lee, H.; Bhat, S.; Bosch, N. Using Machine Learning Explainability Methods to Personalize Interventions for Students. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Educational Data Mining, Durham, UK, 24–27 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjoa, E.; Guan, C. A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Toward Medical XAI. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4793–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conati, C.; Barral, O.; Putnam, V.; Rieger, L. Toward Personalized XAI: A Case Study in Intelligent Tutoring Systems. Artif. Intell. 2021, 298, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.R.; Eberle, W.; Ghafoor, S.K.; Ahmed, M. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Approaches: A Survey. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.09429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamy, J.-B.; Sekar, B.; Guezennec, G.; Bouaud, J.; Séroussi, B. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Breast Cancer: A Visual Case-Based Reasoning Approach. Artif. Intell. Med. 2019, 94, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, R. The Possibilities and Limits of Explicable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Education: A Socio-Technical Perspective. Learn. Media Technol. 2023, 48, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, E.; Silva, I.; Costa, D.G.; Viegas, C.M.D.; Barros, T.M. On the Use of eXplainable Artificial Intelligence to Evaluate School Dropout. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetter, J.W.; Conati, C.; Yang, X.; Abdelshiheed, M.; Barnes, T.; Chi, M. XAI to Increase the Effectiveness of an Intelligent Pedagogical Agent. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Würzburg, Germany, 19 September 2023; ACM: Würzburg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Fiok, K.; Farahani, F.V.; Karwowski, W.; Ahram, T. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Education and Training. J. Def. Model. Simul. 2022, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, H.C.; Core, M.G.; Van Lent, M.; Solomon, S.; Gomboc, D. Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Training and Tutoring. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (12th), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 18–22 July 2005; ResearchGate: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. Smart Education Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). In Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Smart Community; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 101–110. ISBN 978-1-003-40950-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wasilewski, A.; Kolaczek, G. One Size Does Not Fit All: Multivariant User Interface Personalization in E-Commerce. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 65570–65582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. The Limitations of Online Surveys. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2020, 42, 575–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeeh, Z.; Syed Mustapha, S.; Mohamad, R. Healthcare Knowledge Sharing Among a Community of Specialized Physicians. Cogn. Technol. Work 2018, 20, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processe; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, B.S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives the Classification of Educational Goals Handbook I Cognitive Domain; Longmans, Green and Co., Ltd.: London, UK, 1956; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2924447 (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- WES WES iGPA Calculator—WES.Org. Available online: https://applications.wes.org/igpa-calculator/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustapha, S.M.F.D.S. Measuring Students’ Satisfaction on an XAI-Based Mixed Initiative Tutoring System for Database Design. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2025, 8, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8060189

Mustapha SMFDS. Measuring Students’ Satisfaction on an XAI-Based Mixed Initiative Tutoring System for Database Design. Applied System Innovation. 2025; 8(6):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8060189

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustapha, S. M. F. D. Syed. 2025. "Measuring Students’ Satisfaction on an XAI-Based Mixed Initiative Tutoring System for Database Design" Applied System Innovation 8, no. 6: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8060189

APA StyleMustapha, S. M. F. D. S. (2025). Measuring Students’ Satisfaction on an XAI-Based Mixed Initiative Tutoring System for Database Design. Applied System Innovation, 8(6), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/asi8060189