1. Introduction

The Milia faunal association dates to the earliest part of Villafranchian, which is a period of geologic time (3.5–1.0 Ma) overlapping with the end of the Pliocene and the beginning of the Pleistocene. Dramatic changes in the climate and environment of the Northern Hemisphere mark the transition from the Pliocene to the Pleistocene, the so-called Ice Ages. However, this is a story that starts even earlier, in the period between 3.6 and 2.58 million years, the Piacenzian Stage (Late Pliocene), a stage that also includes the Early Villafranchian. Generally, the climate during the Piacenzian was wetter and warmer (a 2 to 3 °C global mean annual surface temperatures higher than today) than present [

1]. In this warm world, however, several short episodes of glaciation took place before the final Northern Hemisphere Glaciation ([

2] and references therein). A significant glaciation event in the Northern Hemisphere occurred approximately at 3.3 Ma (MIS M2), followed by the so-called mid-Piacenzian Warm Period (MPWP; 3.27–2.97 Ma) with a 2 to 3 °C global mean annual surface temperatures higher than today, whereas after 2.7 Ma, the Northern Hemisphere glaciation intensifies ([

2] and references therein). Our interest focuses on the MPWP, a period signaled by many as essential for understanding the present and future warming periods of our planet (see [

1,

2] for reviews and references therein).

Faunal assemblages that survived during this period are commonly grouped in the Early Villafranchian biochronological unit, a concept with a long and complicated history [

3]. Milia joins the list of a handful of localities in the Late Pliocene and can offer valuable insights on the fauna composition in southeastern Europe before the Quaternary.

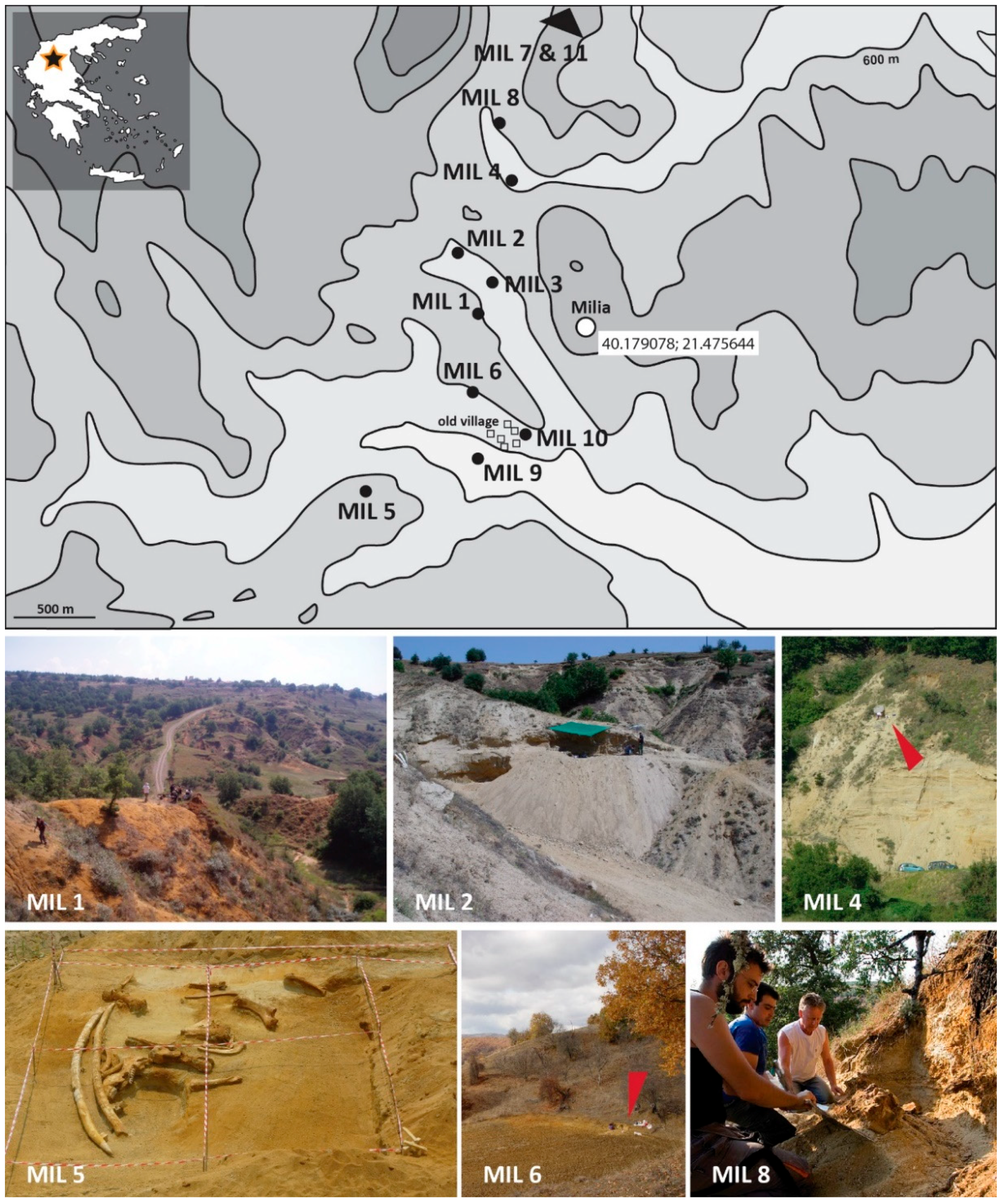

The Milia fossils are scattered in yellow/brownish unconsolidated sand to muddy sand deposits of fluvial origin [

4]. The fossils are quite dispersed and span over a distance of more than 20 km around the village of Milia. Practically, the fossils are organized in at least 11 collection spots around Milia, all of which are grouped into larger localities, i.e., MIL 1–11 (

Figure 1).

Following the first study of the mastodon fossils from Milia [

4], the faunal composition of Milia has been under investigation in recent years, with a series of papers describing the various taxa that were recovered and identified in the fossil record: the proboscideans in Τsoukala [

4] and Τsoukala and Mol [

5], the tapirs, rhinoceroses, and suids in Guérin and Tsoukala [

6], the bovids and cervids in Crégut-Bonnoure and Tsoukala [

7], carnivores in Tsoukala et al. [

8], hipparions in Lazaridis and Tsoukala [

9], and turtles in Vlachos and Tsoukala [

10]. Based on all these studies mentioned above (and references therein), the composite fauna of Milia can be summarized as follows: (Proboscidea)

Mammut borsoni and

Anancus arvernensis; (Perissodactyla)

Tapirus arvernensis arvernensis,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Hipparion sp. (

H. crassum group); (Suidae)

Sus arvernensis arvernensis; (Bovidae)

Grevenobos antiquus,

Alephis sp., Bovini indet.,

Gazella borbonica, Antilopinae indet.; (Cervidae)

Croizetoceros ramosus, Cervidae indet.,

Praeelaphus cf.

lyra; Ruminantia indet.; (Felidae)

Homotherium crenatidens; (Ursidae)

Ursus etruscus,

Agriotherium sp.; Aves indet.; (Testudines)

Mauremys sp.,

Titanochelon sp. and

Testudo brevitesta. Additionally, the presence of a porcupine,

Hystrix cf.

refossa can be inferred by a few fossils and some gnawing marks [

8].

The emerging Milia fauna allowed for the dating of the locality from a biochronological point of view. The association of

S. jeanvireti,

T. a. arvernensis and

S. a. arvernensis allowed Guérin and Tsoukala [

6] to propose an Early Villafranchian (MN16) age. They also notably indicated that the degree of development of the rhino teeth would imply an age that is slightly younger than Vialette (MN16a, 3.14 Ma [

11]). The study of the ruminants added taxa with an MN16 distribution, including

C. ramosus and

G. borbonica, but also identified taxa like

Alephis sp. that point out to an older, Ruscinian (MN15), temporal distribution [

7]. In particular, they proposed that Milia assemblage dates to the transitional period between MN15 and MN16a, or between the Ruscinian and Early Villafranchian, and that is older than Vialette [

7]. The presence of the

Hipparion in Milia [

9] agrees with this expansion to the Ruscinian. Furthermore, the absence of more “modern” faunal elements present in other MN16a assemblages, like

Canis and

Equus in Vialette, France [

11], and

Mammuthus in Bulgaria and Romania [

12] corroborate the ‘archaic’ features of Milia assemblage within MN16a.

Therefore, the age correlations provided by the study of mammalian remains and the mixture of species from both MN15 and MN16a biozones raise an intriguing question: is Milia dated indeed in the boundary between the Ruscinian and the Early Villafranchian (MN15/MN16a), or do these fossils represent a time-averaged fauna ranging from MN15 to MN16a? As the Milia fossils are found in several localities around Milia, all in undifferentiated sand deposits with limited stratigraphic information (see below), one might argue that they could represent a composite fauna of at least two faunas: a Ruscinian and a Late Villafranchian one. It is, therefore, necessary to analyze the assemblages of the various sub-localities of Milia in detail and to try to answer this question. In any case, Milia would represent an important assemblage that documents the onset of the Early Villafranchian in southeastern Europe.

The primary objective of this work is to analyze the faunal composition of Milia quantitatively, with a particular emphasis on describing the composition of each of the main collection points in Milia (

Figure 1). Up to now, most of the previous works describing the Milia fossils and taxa treated Milia assemblage as coming from a single composite locality. As such, we provide, for the first time, information on each collection spot, its main characteristics and the recovered fauna. Then, we estimate the minimum number of individuals for each locality and Milia as a whole. This information, including the presence/absence data from each locality, is used to produce estimates of alpha and beta diversity across the Milia collections. Finally, we summarize our results and provide testable hypotheses for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

Almost 3300 fossil specimens have been collected in Milia as a result of investigations that lasted over twenty years (1996 to the present day). A total of 40 participants (researchers, students and collaborators) participated in seventeen systematic excavations, resulting in the collected material of large mammals, a micromammal, and turtles. All specimens form part of the LGPUT collection (Laboratory of Geology and Paleontology, School of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece), joined with the acronym MIL (MILia; as LGPUT-MIL). The fossils are currently stored and exhibited in the new Paleontological Exhibition in the village of Milia, Grevena (

Figure 2).

Upon discovery, one of us (ET) entered each specimen into a digital database in Microsoft Access. The database also included historical (date of collection; collector), anatomical and taxonomic data, updated regularly following the detailed description and study of the various groups over the recent years (see

Section 1). This database formed the basis of the analyses herein by the calculation of the Pivot Tables in Microsoft Access and Excel. Preliminary diagrams were created in Microsoft Excel and PAST 3.03 [

13], and then further edited in Adobe Illustrator for final presentation purposes. For the analyses herein, the following database records have been excluded as not relevant to this study: two well preserved rhino specimens (a mandible and ulna) from the Priporos site, which is an old sandpit between the Milia and Agios Georgios villages (SGP, 40.171834 N, 021.437836 E) of the former Municipality of Herakleotes [

6] and 30 fossilized wood specimens from MIL 1, 5, 6, and broader MIL sites. Rarefaction curves are calculated following Lyman [

14] and references therein. The minimum number of individuals is estimated based on Badgley [

15], utilizing a range between the Number of Identified Specimens (NISP) and the Minimum Number of Individuals (MNI) counting techniques.

Beta diversity is based on Koleff et al. [

16] and references therein.

3. Localities

For clarity, all points where the fossil specimens have been collected are called “collections”, grouped into larger localities, each of which is marked by the systematic excavations by our team (

Table 1). The main collection points, where full documented excavations took place, are indicated with a single number (e.g., MIL 1), whereas other collections in their vicinity with the addition of one letter (e.g., MIL 1a).

The Milia fossils are scattered in the sand deposits of the Aliakmon River (or Haliakmon, the longest river in Greece, 297 km). The various collections (

Table 1) are organized in eleven main localities (MIL 1–MIL 11). Among these, the most important are MIL 1, MIL 2, MIL 4, and MIL 5, in which since 1996, systematic excavations have yielded three partial skeletons of

Mammut borsoni, among other fossils. On a small scale, excavations have also been carried out in the other localities as well, but with fewer specimens. A variety of collection methods were employed in Milia, including standard systematic paleontological excavations, the collection of surface findings during prospection, vertical emergency excavations with the use of ropes and caving techniques, as well as sieving in small (during the systematic excavations and fieldwork) and large-scale (during the works of commercial sandpits). Finally, numerous shepherds, farmers, and locals have accidentally discovered several specimens and donated them to the collection of the Milia Museum.

Unfortunately, there is limited stratigraphic information available linking the various collections of Milia. In all cases, the fossils are found in undifferentiated loose sands stones. Only in a few cases are some sections available (e.g., MIL 4 and MIL 5) where changes in the stratigraphy can be observed, but all our attempts to perform magnetostratigraphy have been unsuccessful. The only available sedimentological analysis is based on the preliminary results reported by Lazaridis et al. [

17] from their collection of data from MIL 5 during the excavation of 2007 (note that the 2007 section is no longer available because of the commercial activity on the sandpit). They reported that the fossils in MIL 5 were found in sand and muddy sand deposits, whereas they also identified a lacustrine layer containing fossil plants and mollusks above the mastodon fossils [

17]. The results of the sampling of Lazaridis et al. [

17] are not published yet, but the preliminary information of the plant identifications provide further support for a limit of the Pliocene/Pleistocene age for the vertebrate fossils.

3.1. Milia-1 Locality (MIL 1)

The Milia-1 locality (MIL 1) is located across the village of Milia (

Figure 1) and was discovered in 1996 by a member the Thessaloniki Aristotle University (AUTH) team at the top of a hill with these typical loose sand-deposits of Aliakmon River that dominate in the area. After a rain, the trochlea of a mastodon humerus was revealed and spotted by the team, leading to the excavation of a partial skeleton of

Mammut borsoni. Twenty-one specimens were recorded from three systematic excavation campaigns, which revealed the following: in 1997, the skull fragment (maxilla area) with M2 and M3, the two complete upper tusks in a position crosswise and anatomical direction, and the complete right humerus, together with a lower molar of

Grevenobos antiquus; in 1998, the complete mandible with full dentition, right and left m2, m3, and i2, and the complete right ulna and right tibia; whereas in 1999, thoracic vertebra, the complete left ulna, six ribs, and four indeterminable bone fragments. Species list:

Mammut borsoni, Grevenobos antiquus. 3.2. Milia-1a Collection (MIL 1a)

The collected fossils grouped into the MIL 1a collection spot come from the surroundings of MIL 1, and specifically from the outskirts of Milia village and north of the Tsartsarakos area. It is the area between the MIL 2 and MIL 3 localities. Species list: Mammut borsoni, Hipparion sp. (“crassum” group), Croizetoceros ramosus, Stephanorhinus jeanvireti, Grevenobos antiquus, Sus arvernensis, Testudo brevitesta and Homotherium crenatidens.

3.3. Milia-2 Locality (MIL 2)

The MIL 2 site was also discovered by members of the AUTH team in 2002, in a small ravine between two hills (

Figure 1). Four main systematic excavation campaigns took place and brought to light 51 specimens: in 2002, a complete right humerus and left pelvis of a female individual found at the base of the ravine; in 2003, two maxilla fragments with M3 right and M2 left and an almost complete mandible with left and right middle worn m2, m3 of a male individual; in 2004, a cranium fragment with very robust occipital area and condyles, ten ribs, an almost complete thoracic vertebra, spina, arcus and a complete very long left femur; in 2005, six ribs, three thoracic vertebrae, and a lumbar vertebra found in the middle of the right hill. Species list:

Mammut borsoni,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Hipparion sp. (“

crassum” group),

Gazella borbonica,

Croizetoceros ramosus,

Sus arvernensis,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti.

3.4. Milia-2a Collection (MIL 2a)

Outside the systematic excavation area of MIL 2, at least 105 specimens have been collected following prospection, either by the members of the AUTH team or by the locals. From this collection spot, we have been able also to discover the first occurrence of a tapir in Greece, represented by a mandible of a juvenile. Species list: Mammut borsoni, Grevenobos antiquus, Hipparion sp. (“crassum” group), Gazella borbonica, Croizetoceros ramosus, Sus arvernensis, Ursus etruscus, Homotherium crenatidens, Anancus arvernensis, Stephanorhinus jeanvireti, Tapirus arvernensis and Mauremys sp.

3.5. Milia-3 Locality (MIL 3)

The MIL 3 site is located on the hillside between the MIL 1 and MIL 2 sites (

Figure 1). The most important findings include the complete skull and mandible with the dentition of a rhino, found in 2002 and the skull (holotype) of the large bovid

Grevenobos antiquus, which was found in 2005. Species list:

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Sus arvernensis,

Croizetoceros ramosus,

Mammut borsoni.

3.6. Milia-4 Locality (MIL 4)

The MIL 4 locality is the main vertical outcrop of an old abandoned sandpit, about 25 m high (

Figure 1), yielding about 90 specimens. The main findings include a complete

M. borsoni calcaneum (2005 excavation, at a depth of 12 m from the surface), remains of a

M. borsoni female individual, with tusks and ribs, associated with a

Grevenobos antiquus mandible (2010 excavation, at a depth of 19 m from the surface), and the type-specimen of

Testudo brevitesta (2006 excavation, at a depth of 13 m from the surface). Because of the steep slope, these vertical excavations are often made with the help of ropes and caving harnesses. More fossils found in the broader area, behind MIL 4 and towards the Kokkinia village, were collected in small outcrops by the locals and by the AUTH team; these are grouped under the Milia-4a (MIL 4a) collection spot. Species list:

Mammut borsoni,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Testudo brevitesta. MIL 4a:

Mammut borsoni,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Hipparion sp. (“

crassum” group),

Croizetoceros ramosus,

Gazella borbonica,

Testudo brevitesta.

3.7. Milia-5 Locality (MIL 5)

The MIL 5 site was discovered in 2006 by a crane operator during commercial work in the area (

Figure 1). The systematic excavations in 2007 yielded important findings such as the partial skeleton of

M. borsoni and other fossils found about 14 m below the surface. The excavation followed the paleontological rules with the orientated block of squares, the reference point, the measure of the coordinates and the photographic documentation. The partial skeleton comprises of two cranium fragments, a left maxilla fragment with M2, two complete upper tusks, an almost complete mandible with left and right m2 and m3, a thoracic vertebra spina, 13 ribs, right scapula, right and left humerus and radius, complete right ulna, pisiform, and unciform. The two complete tusks were found in parallel position, but opposite direction (

Figure 1): the tip of the one was near the pulp cavity of the other. Thus, we interpreted that the animal died nearby, the tusks were subsequently transported for several meters and formed a barrier that sustained several bones of the skeleton. In addition, right before the entrance to the sandpit of the main excavation of MIL 5, a robust proximal femur with caput and the first and the fourth ribs was discovered and excavated in 2012. This outcrop was named Milia 5’ (MIL 5’). Furthermore, numerous fossils have been collected in the surroundings of MIL 5 by the AUTH team during prospection, by local shepherds as accidental findings, and as the result of the sieving process during the commercial works in the sandpit. The latter works were supervised for three years (2006–2008) by local authorities, yielding abundant fossils (approximately 1100 specimens, including some petrified wood fragments). These findings are grouped under the Milia-5a and 5b collection spots (MIL 5a, MIL 5b). Species list:

Mammut borsoni,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Hipparion sp. (“

crassum” group),

Gazella borbonica,

Praeelaphus cf.

lyra,

Alephis sp.,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Croizetoceros ramosus,

Sus arvernensis,

Ursus etruscus,

Tapirus arvernensis,

Homotherium crenatidens,

Agriotherium sp.,

Anancus arvernensis,

Hystrix cf.

refossa,

Testudo brevitesta,

Titanochelon sp.,

Mauremys sp.

3.8. Milia-6 Locality (MIL 6)

The Milia-6 collection spot is located in the vineyards between MIL 1 and the old village of Milia (

Figure 1) and was discovered during the field plowing. The systematic excavation took place in November 2005 and yielded parts of a tusk of a female Borson’s mastodon. In the broader area (Milia-6a, MIL 6a, Arkoudolakkos) few fossils were also collected by a shepherd. Species list:

Mammut borsoni (MIL 6). MIL 6a:

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Mammut borsoni.

3.9. Milia-7 Locality (MIL 7)

The Milia-7 (MIL 7) collection spot is located at the foothills of an old sandpit, near the village of Kivotos (

Figure 1). In 2006, a pelvic fragment with the right acetabulum of a mastodon was excavated. In addition, specimens of a rhino and a cervid were collected by shepherds. Species list:

Mammut borsoni,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Croizetoceros ramosus.

3.10. Milia-8 Locality (MIL 8)

The Milia 8 site is located at the foot of a hill, towards the village of Kokkinia (

Figure 1). In 2008, a well-preserved dorsal part of a rhino skull was excavated. In addition, few specimens of proboscideans and artiodactyls were subsequently discovered. Species list:

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Mammut borsoni,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Anancus arvernensis.

3.11. Milia-9 Locality (MIL 9)

The Milia-9 (MIL 9) collection spot is located near the old village of Milia, which was abandoned many years ago after a landslide. A local shepherd collected fossils from the Vrissi area. The most important finding is an extremely rare lower deciduous tusk of Mammut borsoni. In the broader area of MIL 9, in the areas of Mezaria and Livadia, some bovid and hipparion fossils have been found; both are grouped under Milia-9a (MIL 9a) collection spot. Species list: Mammut borsoni, Stephanorhinus jeanvireti, Grevenobos antiquus, Hipparion sp. (“crassum” group).

3.12. Milia-10 Locality (MIL 10)

The Milia 10 site is located near the church of the old village of Milia (

Figure 1). A local shepherd collected twelve fossils of various animals, including some plastral fragments of a tortoise. Following the delivery of these first specimens, members of the AUTH team visited the place and, through sieving, discovered the remaining fragments of the tortoise plastron. Species list:

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Mammut borsoni,

Grevenobos antiquus,

Hipparion sp. (“

crassum” group),

Testudo brevitesta.

3.13. Milia-11 Locality (MIL 11)

The Milia 11 is located near the village of Kokkinia (

Figure 1). Local people collected few fossils of various taxa. Following this information, members of the AUTH team collected a scapula of

M. borsoni. Species list:

Mammut borsoni,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti,

Hipparion sp. (“

crassum” group).

5. Concluding Remarks

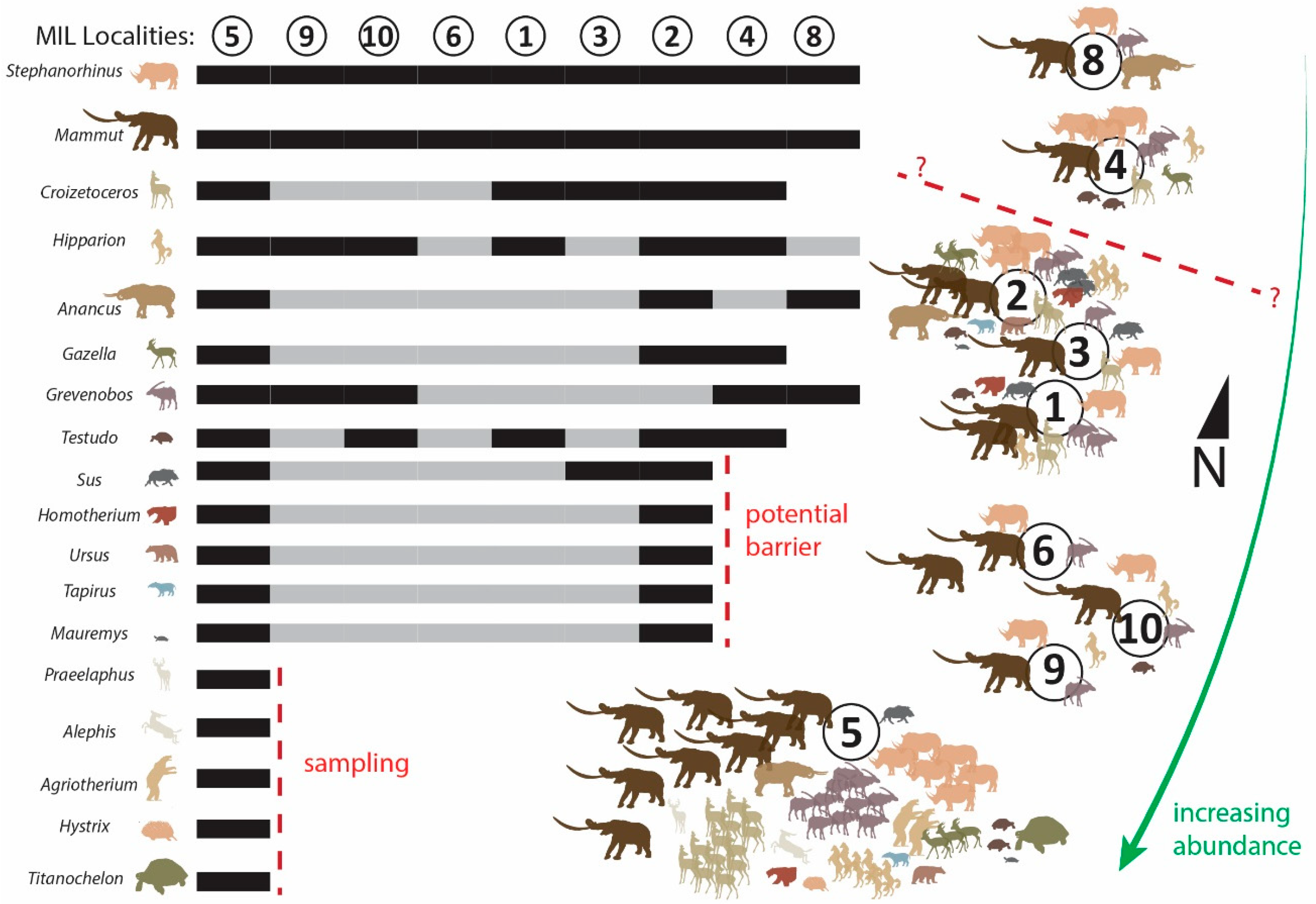

Paleontological investigations in the area of Milia during the last 20 years have brought to light more than 3200 fossil specimens of mammals, birds, and turtles of at least 19 different taxa. Based on previous systematic works (see Introduction), we are now able to summarize the taxonomic catalog of Milia and further analyze it in the regional context within the sub-localities of Milia. Although the taxonomic composition and species richness vary among the various collections of Milia, the wide distribution of Stephanorhinus jeanvireti, Mammut borsoni, Croizetoceros ramosus, Hipparion sp. (H. crassum group), Anancus arvernensis, Gazella borbonica, Grevenobos antiquus and Testudo brevitesta allow us to correlate them clearly. The presence of partial skeletons in several localities, pairs of tusks and associated specimens indicate that there is a considerable degree of association between the recovered fossils. At the same time, there is also clear evidence of moderate fluvial transport and the further modification of the original assemblages. Thus, we can argue with considerable evidence that the collections made in the various localities around Milia represent a single assemblage; as the majority of the localities are surface collections of small extension, both horizontally and vertically, we conclude that most likely the Milia assemblage had a short temporal distribution. In any case, this conclusion should be backed by more stratigraphical, sedimentological, and chronological data in the ongoing research in Grevena.

The abundance of the rhino

S. jeanvireti and the mastodon

M. borsoni confirms the MN16 character of the Milia fauna, further corroborated by the solitary findings of

Tapirus a. arvernensis and

Sus a. arvernensis (

Figure 4). The presence of

Agriotherium would instead constrain the age of the Milia assemblage to the MN16a; indeed, the Milia fauna is quite similar to Vialette (France) and Triversa (Italy) faunas. Interestingly, the presence of

Hipparion sp. and

Alephis sp. indicate an older MN15 temporal distribution as these taxa are typically found up to MN15 (e.g., Perpignan, France)—still, Milia is undoubtedly different from Perpignan, as the rhino, suid, cervid, bear, and tapir belong to different species or subspecies compared to the French locality.

As far as the estimation of the age of the Milia fauna from a biochronological point of view is concerned, we strongly re-affirm the Early Villafranchian (MN16) affinities of Milia and we even suggest that it represents an MN16a fauna. The presence of Ruscinian (MN15) elements in the assemblage is intriguing and based on the available evidence can be explained with the extended survival of Ruscinian taxa in Greece, either in the boundary between the Ruscinian and the Early Villafranchian or to the earliest Villafranchian. In any case, and from a biochronological point of view, Milia should be older than Vialette (<3.14 Ma), in agreement with Crégut-Bonnoure and Tsoukala [

7]. However, we would like to point out that the refinement of the age estimation of Milia is based on three taxa identified only up to the genus level. Although for our conclusion herein this level of identification is enough, the discovery of more specimens belonging to these taxa that could lead to a more detailed identification would be of paramount importance for the ongoing research in Milia.

Milia joins a handful of Late Pliocene localities that allow documenting the onset of the Villafranchian, including Vialette (MN16a) and Etouaires (MN16b) from France, Triversa (MN16a) and Montopoli (MN16b) from Italy, Villaroya (MN16) from Spain, and Hajnacka (MN16) from Slovakia ([

3,

11,

20,

21] and references therein). These localities demonstrate the latest chapters of the long evolutionary history of successful and widespread species such as

Mammut borsoni,

Stephanorhinus jeanvireti and

Tapirus arvernensis that became extinct at the end of the Pliocene. Milia and the localities mentioned above also provide evidence of the typical Late Neogene faunas of Europe that changed drastically in the Pleistocene. In Milia, we have fantastic evidence of the favorable conditions that existed in the Late Pliocene, as several taxa are found to reach larger-than-expected and even record-breaking sizes. Of course, the mastodon

M. borsoni is, beyond any doubt, a true giant surviving in Milia, having the longest tusks discovered so far that reach 5 m in length. However, most of the other species known from Milia also reached large sizes: the dimensions of the rhino bones are closer to the highest values of this species and in some cases exceed them, whereas the tapir is among the largest as well [

6]; the turtles were also large, with a giant tortoise, a robust small-sized tortoise and probably the largest member of

Mauremys known [

10]. Therefore, the Milia fossils could provide valuable evidence on the life history of these species, and suggest the presence of exceptionally favorable conditions in Milia at the beginning of the Villafranchian.

The quantitative analysis herein shows that sampling in Milia is sufficient to provide some robust estimates of the species richness in the area. In other words, it seems that our investigations have already led to the discovery of the vast majority of the taxa represented in the fossil record of Milia. Besides the identification of well-known and widespread taxa, we have been able also to discover some new taxa, including the bovid

Grevenobos antiquus [

7] and the tortoise

Testudo brevitesta [

10]. The most abundant and widespread taxa were the rhino

S. jeanvireti, the bovid

G. antiquus, and the cervid

C. ramosus, followed closely by the mastodon

M. borsoni, together tallying up to a total of at least 74–137 individuals. The remaining species were less frequent with only a handful or isolated occurrences. Overall, we estimate that the Milia fossils represent at least 129 to 192 different individuals.

The analysis of alpha and beta diversity confirmed the importance of the MIL 5 locality, the richest and most diverse collection in Milia. However, our analysis highlights for the first time that future research should focus on both MIL 2 and MIL 4 localities. These localities show a significant potential of providing an even more diverse record than they already have. Additionally, the analysis of beta diversity suggests a potential barrier between these two localities (currently divided by the hill of the Milia village), as several species that are more adapted to wet environments (Sus, Tapirus, and Mauremys) and two carnivores (Homotherium and Ursus) fail to cross this potential barrier. Further sampling in these localities would be of paramount importance to help identify potential biogeographical barriers in the composite Milia assemblage and to exclude other types of bias (taphonomical, sampling) that could alter our interpretations. Our work further identifies the area south of MIL 5 as having enormous potential for future discoveries because of the following observations: (a) the various collections are placed, almost, on a line of north-to-south orientation; (b) MIL 5 is the southernmost, richest and most diverse locality; (c) even with the sampling bias of MIL 5, the abundance (seen as minimum number of individuals) increases towards the south. Consequently, future research should focus on the discovery of more fossil collection points towards the south. Additionally, based on the first results expressed herein, future research in Milia should also focus on detailed taphonomical analyses of the fossils.

The abundance and richness of the fossil record summarized herein place Milia as the richest Pliocene locality in Greece and among the richest in Europe, dating back to a crucial period for the faunal evolution in the Palearctic region. Although this work focuses on what is going on within the Milia assemblage, we hope that it culminates an initial period of research of this important paleontological paradise. During this initial period, we have been able to confidently identify the taxic diversity in Milia (see previous works in Introduction) and analyze the diversity of this composite assemblage in quantitative terms (this work). Several of the questions raised above will set the basis for our future research in Milia. We also hope that this basis will serve others to include the Milia assemblage in future discussions surrounding the faunal changes during the Early Villafranchian and Quaternary. We anticipate that the fossil record of Milia will hold a significant place in these discussions and could be considered as a reference point for the MN16a biozone in southeastern Europe. It should also be recognized as the best-preserved fossil record of the mastodon Mammut borsoni, a species with a broad distribution temporally and geographically, but never known by such complete fossils that allow detailed documentation of its anatomy.

Shortly after their co-occurrence in Milia, the giants of the Early Villafranchian, including M. borsoni, and S. jeanvireti, survived a bit longer but never crossed to the Quaternary. Instead, A. arvernensis, G. borbonica, C. ramosus, H. crenatidens, and Titanochelon managed to survive a little more at the beginning of the Quaternary before they became, eventually, extinct. Milia paints with vivid colors the calmness before the Quaternary “storm” that brought dramatic and shocking faunal and climate changes. As its unique fossils indicate, around 3 Ma Milia was a paradise for these animals without water or food shortage, allowing them to reach record-breaking sizes and a remarkable diversity—a paradise lost following the climate changes in the Quaternary.