Hydrogels as Reversible Adhesives: A Review on Sustainable Design Strategies and Future Prospects

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. History of Adhesion and Adhesives

1.2. Relevance of Adhesion in Today’s Landscape

1.3. Content of This Review

2. Theory of Adhesion

2.1. Fundamental Concepts

2.2. Mechanisms of Adhesion

2.3. Types of Adhesives and Bonding Modes

- Reversible or stimuli-responsive adhesives: systems capable of switching between adhesive and non-adhesive states when triggered by temperature, pH, light, hydration, or other stimuli [58].

- Natural adhesives offer an additional category, as biological systems provide inspiration for strong, reversible adhesion under challenging conditions. Examples include mussel foot proteins that form covalent catechol bonds in wet environments, and gecko footpads that rely on hierarchical fibrillar structures for van der Waals adhesion [37,59].

2.4. Commercially Available Adhesive Products

2.5. Adhesive Landscape in Market and Research Perspectives

3. Reversible Adhesion

3.1. Already Explored Strategies

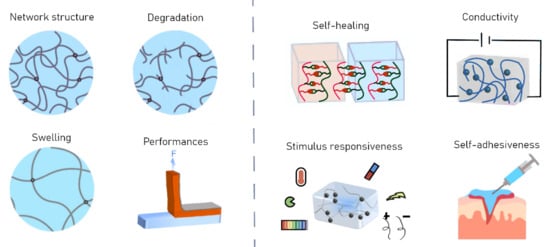

3.2. Hydrogels

4. Formulation of Adhesives Towards Sustainability

4.1. From Conventional to Sustainable Formulations

4.2. End of Life, Recyclability, and Environmental Footprint

4.3. Regulatory Aspects

5. Characterization and Performance Evaluation

5.1. Conventional Adhesion Tests

5.1.1. Peel Tests

5.1.2. Tack Tests

5.1.3. Shear and Lap Shear Tests

5.1.4. Compression and Tensile Tests

5.2. Surface and Interfacial Characterization

5.2.1. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

5.2.2. Surface Energy and Contact Angle Measurements

5.2.3. Rheology and Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

5.2.4. Spectroscopic and Microscopic Analyses

5.2.5. Emerging Techniques

5.3. Metrics for Reversibility and Reusability

5.3.1. Cyclic Adhesion–Debonding Tests

5.3.2. Fatigue and Creep Resistance

5.3.3. Environmental Stability

5.3.4. Self-Healing and Recovery Metrics

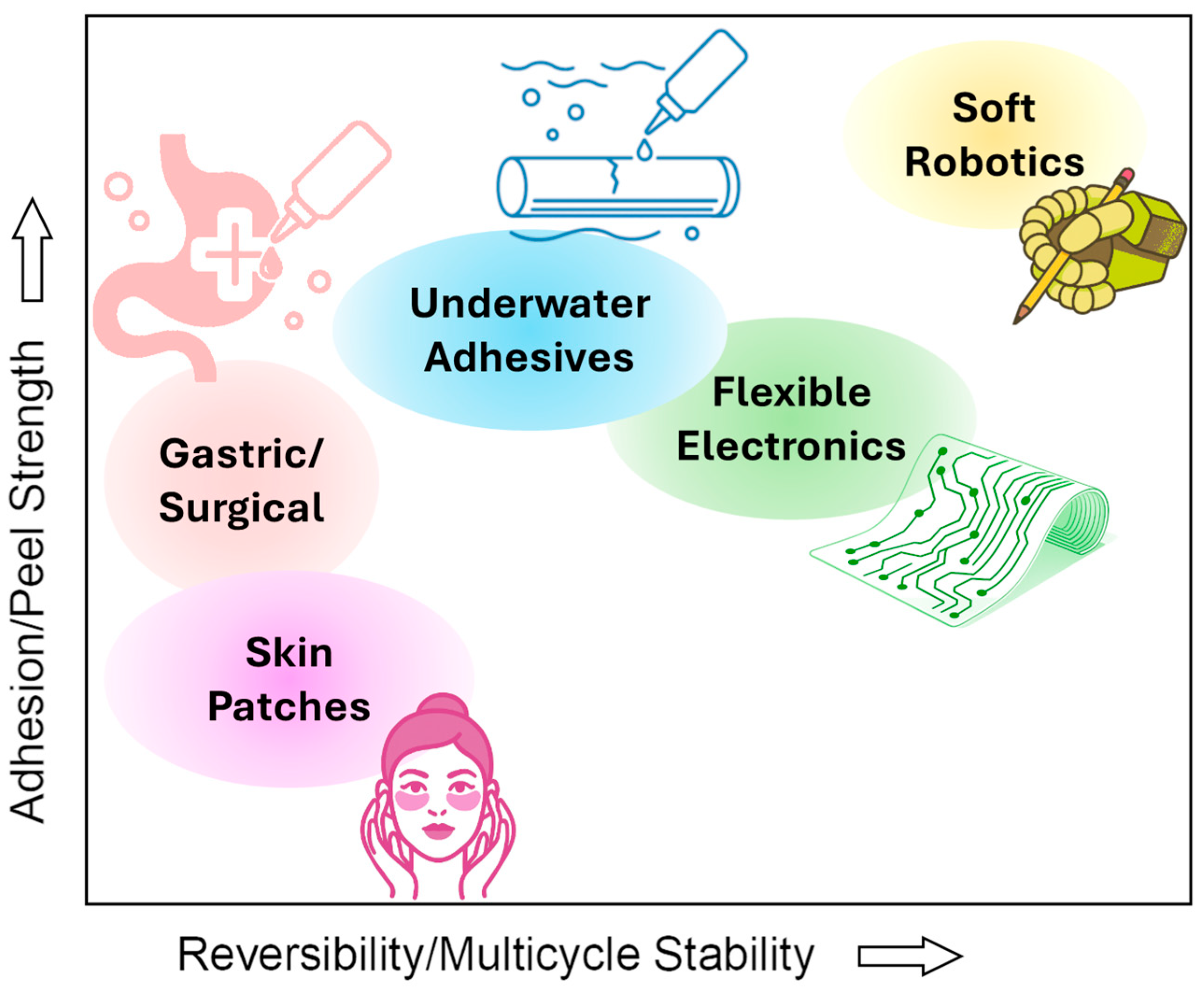

6. Latest Developments in Hydrogel-Based Adhesives

6.1. Bioinspired Hydrogel Adhesives

6.2. Biomedical Hydrogel Adhesive

6.3. Hydrogel Adhesives in Soft Robotics and Flexible Electronics

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

- Sustainable Material Development: the transition toward bio-derived, biodegradable, and non-toxic hydrogel networks is essential. Renewable polymers such as polysaccharides, proteins, and microbial biopolymers should be explored to replace petrochemical or metal-based components. As evidenced by our survey, only a small fraction of current systems fully integrates sustainability considerations at the material and process level, evidencing the need for design frameworks that balance performance with environmental impact. Integrating LCA and end-of-life analysis into early design stages will ensure a realistic path toward environmentally responsible adhesives.

- Mechanistic Understanding and Standardization: although numerous chemistries and formulations have been proposed, a clear structure–property–function relationship is still lacking. In fact, the variety of testing procedures and environmental conditions documented in this review evidenced that cross-study comparisons can be extremely challenging. Establishing standardized adhesion testing protocols, predictive models, and inter-laboratory benchmarks will be vital to enable meaningful comparison and industrial translation.

- Integration with Smart and Hybrid Technologies: the next generation of hydrogel adhesives should incorporate multifunctionality, such as electrical conductivity, self-healing, or antimicrobial activity, without compromising reversibility or sustainability. Hybrid architectures combining organic networks with bioactive fillers, nanocellulose, or biodegradable conductive components could bridge mechanical adaptability with advanced functionality.

- Environmental Stability and Durability: Improving hydrogel performance in humid, saline, or dynamically loaded environments remains a major challenge. Strategies such as hierarchical crosslinking, hybrid nanofiller reinforcement, and double-network formation may enhance mechanical resilience while maintaining reusability and biocompatibility. Yet, as shown in this review, most high-performance systems still rely on laboratory-scale methods with limited prospects for scale-up, indicating a need for process-oriented innovation.

- Scalability and Circularity: To enable real-world application, synthetic routes must be simplified, energy use reduced, and compatibility with scalable manufacturing (e.g., printing or coating) ensured. Developing chemically recyclable or stimuli-debondable hydrogel adhesives could support circular economy models and extend material lifetime.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Acrylic acid |

| AAm | Acrylamide |

| AFM | Atomic force microscopy |

| ATGel | Acid-tolerant hydrogel |

| CAGR | Compound annual growth rate |

| CD | β-cyclodextrin |

| CNF | Cellulose nanofibril |

| CNT | Carbon nanotubes |

| CS | Chitosan |

| DOPA | 3,4-dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine |

| Gel | Gelatin |

| HEMA | Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| LCA | Life-cycle assessment |

| LCST | Lower critical solution temperature |

| MEA | Methoxyethyl acrylate |

| NHS | N-hydroxysuccinimide |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| NVP | N-vinylpyrrolidone |

| PA | Phytic acid |

| PAA | Poly(acrylic acid) |

| PAAm | Polyacrylamide |

| PEGDA | poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate |

| PDMS | Poly(dimethylsiloxane) |

| PENRT | Primary Energy Non-Renewable Total |

| pNIPAM | poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) |

| PSA | Pressure-sensitive adhesives |

| PVA | Poly(vinyl alcohol) |

| REACH | European Chemicals Agency’s Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals |

| UTM | Universal testing machine |

| VOC | Volatile organic compounds |

References

- Upadhyaya, S.; Devi, M.; Borah, S.; Sarma, N.S. Organic Polymers for Adhesive Applications: History, Progress, and the Future. In Organic Polymers in Energy-Environmental Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 491–512. ISBN 978-3-527-84281-0. [Google Scholar]

- Fay, P.A. A History of Adhesive Bonding. In Adhesive Bonding, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Welding and Other Joining Technologies; Adams, R.D., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 3–40. ISBN 978-0-12-819954-1. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza, P.P.A.; Martini, F.; Sala, B.; Magi, M.; Colombini, M.P.; Giachi, G.; Landucci, F.; Lemorini, C.; Modugno, F.; Ribechini, E. A New Palaeolithic Discovery: Tar-Hafted Stone Tools in a European Mid-Pleistocene Bone-Bearing Bed. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, A.F.; Thissen, J.P. Hafted Armatures and Multi-Component Tool Design at the Micoquian Site of Inden-Altdorf, Germany. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, R.J.; Dunne, J.; Brunning, S.; Devièse, T.; Mortimer, R.; Ladd, S.; Parfitt, K.; Evershed, R.; Bull, I. Birch Bark Tar in Early Medieval England—Continuity of Tradition or Technological Revival? J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2020, 29, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niekus, M.J.L.T.; Kozowyk, P.R.B.; Langejans, G.H.J.; Ngan-Tillard, D.; Van Keulen, H.; Van Der Plicht, J.; Cohen, K.M.; Van Wingerden, W.; Van Os, B.; Smit, B.I.; et al. Middle Paleolithic Complex Technology and a Neandertal Tar-Backed Tool from the Dutch North Sea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 22081–22087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urem-Kotsou, D.; Stern, B.; Heron, C.; Kotsakis, K. Birch-Bark Tar at Neolithic Makriyalos, Greece. Antiquity 2002, 76, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauter, F.; Varmuza, K.; Werther, W.; Stadler, P. Studies in Organic Archaeometry V1: Chemical Analysis of Organic Material Found in Traces on an Neolithic Terracotta Idol Statuette Excavated in Lower Austria. Arkivoc 2002, 2002, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solazzo, C.; Courel, B.; Connan, J.; Van Dongen, B.E.; Barden, H.; Penkman, K.; Taylor, S.; Demarchi, B.; Adam, P.; Schaeffer, P.; et al. Identification of the Earliest Collagen- and Plant-Based Coatings from Neolithic Artefacts (Nahal Hemar Cave, Israel). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rackham, H. (Translator) Pliny, Natural History, Volume II: Books 3–7; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1942; ISBN 978-0-674-99388-4. [Google Scholar]

- Donkerwolcke, M.; Burny, F.; Muster, D. Tissues and Bone Adhesives—Historical Aspects. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-I.; Grobelny, J.; Pradeep, N.; Cook, R.F. Origin of Adhesion in Humid Air. Langmuir 2008, 24, 1873–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buwalda, S.J.; Boere, K.W.M.; Dijkstra, P.J.; Feijen, J.; Vermonden, T.; Hennink, W.E. Hydrogels in a Historical Perspective: From Simple Networks to Smart Materials. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A. Joining Composites with Adhesives: Theory and Applications; DEStech Publications, Inc.: Lancaster, PA, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-60595-093-8. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, S.; Bonin, H.W.; Bui, V.T.; Weir, R.D. Modification of High-Performance Polymer Composite through High-Energy Radiation and Low-Pressure Plasma for Aerospace and Space Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 1959–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, S.; Benedictus, R.; Poulis, J.A.; Bonin, H.W.; Bui, V.T. High-Performance Nanoadhesive Bonding of Titanium for Aerospace and Space Applications. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2009, 29, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, R.J.; Cochran, M.A.; Allen, K.W. Adhesives in Packaging. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 1995, 15, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versino, F.; Ortega, F.; Monroy, Y.; Rivero, S.; López, O.V.; García, M.A. Sustainable and Bio-Based Food Packaging: A Review on Past and Current Design Innovations. Foods 2023, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Song, H.; Chen, L.; Li, W.; Yang, D.; Cheng, P.; Duan, H. 3D Printed Ultrasensitive Graphene Hydrogel Self-Adhesive Wearable Devices. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 5199–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lai, J.; Jin, X.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Chen, W.; Ma, A.; Zhou, X. Intrinsically Adhesive, Highly Sensitive and Temperature Tolerant Flexible Sensors Based on Double Network Organohydrogels. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, X.; Wu, X.; Dai, K.; Wan, P. Flexible conformally adhesive hydrogel electronics. Matter 2025, 8, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hedenqvist, M.S.; Chen, C.; Cai, C.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Fu, J. Multifunctional Conductive Hydrogels and Their Applications as Smart Wearable Devices. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 2561–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T. III. An Essay on the Cohesion of Fluids. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1805, 95, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupré, A. Théorie Mécanique de la Chaleur; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1869. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J.W. On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances. Am. J. Sci. 1878, s3-16, 441–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, N.L.; Harrison, W.J. The Stresses in an Adhesive Layer. J. Adhes. 1972, 3, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, E.P. Nonuniform Pressure Device for Bonding Thin Slabs to Substrates. J. Adhes. 1972, 3, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wool, R.P.; O’Connor, K.M. Craze Healing in Polymer Glasses. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1981, 21, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowkes, F.M. Role of Acid-Base Interfacial Bonding in Adhesion. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1987, 1, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciferri, A. Molecular Recognition at Interfaces. Adhesion, Wetting and Bond Scrambling. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1088613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Kang, Z.; Hirahara, H.; Li, W. Interfacial Nanoconnections and Enhanced Mechanistic Studies of Metallic Coatings for Molecular Gluing on Polymer Surfaces. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Ishida, K.; Okada, K. Investigation of Micro-Adhesion by Atomic Force Microscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2001, 169–170, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, S. Electron Microscopy for Visualization of Interfaces in Adhesion and Adhesive Bonding. In Interfacial Phenomena in Adhesion and Adhesive Bonding; Horiuchi, S., Terasaki, N., Miyamae, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 17–112. ISBN 978-981-99-4456-9. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, J.H.; Tanzer, M.L. Polyphenolic Substance of Mytilus Edulis: Novel Adhesive Containing L-Dopa and Hydroxyproline. Science 1981, 212, 1038–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autumn, K.; Liang, Y.A.; Hsieh, S.T.; Zesch, W.; Chan, W.P.; Kenny, T.W.; Fearing, R.; Full, R.J. Adhesive Force of a Single Gecko Foot-Hair. Nature 2000, 405, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesel, L.F.; Greiner, C.; Arzt, E.; del Campo, A. Gecko-Inspired Surfaces: A Path to Strong and Reversible Dry Adhesives. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2125–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, B.P.; Messersmith, P.B. A Reversible Wet/Dry Adhesive Inspired by Mussels and Geckos. Nature 2007, 448, 338–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamino, K. Mini-Review: Barnacle Adhesives and Adhesion. Biofouling 2013, 29, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Strickland, J.; Ye, Z.; Wu, W.; Hu, B.; Rittschof, D. Biochemistry of Barnacle Adhesion: An Updated Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzmann, C.; Weder, C.; Espinosa, L.M. de Supramolecular Polymer Adhesives: Advanced Materials Inspired by Nature. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, D.J. (Ed.) Theories and Mechanisms of Adhesion. In Handbook of Adhesive Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, K.W. “At Forty Cometh Understanding”: A Review of Some Basics of Adhesion over the Past Four Decades. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2003, 23, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wake, W.C. Theories of Adhesion and Uses of Adhesives: A Review. Polymer 1978, 19, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinloch, A.J. Adhesion and Adhesives; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1987; ISBN 978-90-481-4003-9. [Google Scholar]

- Langmuir, I. The Adsorption of Gases on Plane Surfaces of Glass, Mica and Platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N. (Ed.) Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; p. iii. ISBN 978-0-12-375182-9. [Google Scholar]

- Verwey, E.J.W.; Overbeek, J.T.G.; van Nes, K. Theory of the Stability of Lyophobic Colloids: The Interaction of Sol Particles Having an Electric Double Layer; Elsevier Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wolloch, M. Interfacial Charge Density and Its Connection to Adhesion and Frictional Forces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 026804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voyutskii, S.S.; Vakula, V.L. The Role of Diffusion Phenomena in Polymer-to-Polymer Adhesion. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1963, 7, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plueddemann, E.P. Silane Coupling Agents; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-1-4899-2072-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kinloch, A.J.; Young, R.J. Fracture Behaviour of Polymers; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; ISBN 978-94-017-1596-6. [Google Scholar]

- Good, R.J. Contact Angle, Wetting, and Adhesion: A Critical Review. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 1992, 6, 1269–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalucha, D.J.; Abbey, K.J. The Chemistry of Structural Adhesives: Epoxy, Urethane, and Acrylic Adhesives. In Kent and Riegel’s Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology; Kent, J.A., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 591–622. ISBN 978-0-387-27843-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorn, S.R. (Ed.) Structural Adhesives; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1986; ISBN 978-1-4684-7783-2. [Google Scholar]

- Aronovich, D.A.; Boinovich, L.B. Structural Acrylic Adhesives: A Critical Review. In Progress in Adhesion and Adhesives; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 651–708. ISBN 978-1-119-84670-3. [Google Scholar]

- Mapari, S.; Mestry, S.; Mhaske, S.T. Developments in Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives: A Review. Polym. Bull. 2021, 78, 4075–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, S.V.; Kandasubramanian, B.; Sidharth, S. A Review on Recent Trends in Bio-Based Pressure Sensitive Adhesives. J. Adhes. 2023, 99, 2145–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blelloch, N.D.; Yarbrough, H.J.; Mirica, K.A. Stimuli-Responsive Temporary Adhesives: Enabling Debonding on Demand through Strategic Molecular Design. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 15183–15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, B.K. Perspectives on Mussel-Inspired Wet Adhesion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10166–10171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebnesajjad, S. Handbook of Adhesives and Surface Preparation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4377-4461-3. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, E.M. Handbook of Adhesives and Sealants, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-260-44044-7. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Celiz, A.D.; Yang, J.; Yang, Q.; Wamala, I.; Whyte, W.; Seo, B.R.; Vasilyev, N.V.; Vlassak, J.J.; Suo, Z.; et al. Tough Adhesives for Diverse Wet Surfaces. Science 2017, 357, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, I.; Ola, S.K.; Priyanka; Dhayal, V.; Shekhawat, D.S. Recent Advances in Epoxy Coatings for Corrosion Protection of Steel: Experimental and Modelling Approach-A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 1658–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornima Vijayan, P.; Formela, K.; Saeb, M.R.; Chithra, P.G.; Thomas, S. Integration of Antifouling Properties into Epoxy Coatings: A Review. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2022, 19, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, M.; Perini, I.; Ridi, F.; Baglioni, P. Improving the Properties of Antifouling Hybrid Composites: The Use of Halloysites as Nano-Containers in Epoxy Coatings. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 623, 126779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldan, A. Adhesively-Bonded Joints and Repairs in Metallic Alloys, Polymers and Composite Materials: Adhesives, Adhesion Theories and Surface Pretreatment. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, M.F. Polyurethanes: Science, Technology, Markets, and Trends, 2nd ed.; Wiley Series on Polymer Engineering and Technology Ser; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-66947-0. [Google Scholar]

- Creton, C. Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives: An Introductory Course. MRS Bull. 2003, 28, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedek, I.; Feldstein, M.M. Technology of Pressure-Sensitive Adhesives and Products; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4200-5941-0. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, P.R. Cyanoacrylate Adhesives: A Critical Review. Rev. Adhes. Adhes. 2016, 4, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bré, L.P.; Zheng, Y.; Pêgo, A.P.; Wang, W. Taking Tissue Adhesives to the Future: From Traditional Synthetic to New Biomimetic Approaches. Biomater. Sci. 2013, 1, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, C.; Zetterlund, P.B.; Aldabbagh, F. Radical Polymerization of Alkyl 2-Cyanoacrylates. Molecules 2018, 23, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharde, S.; Sharma, G.; Kandasubramanian, B. Hot-Melt Adhesives: Fundamentals, Formulations, and Applications: A Critical Review. In Progress in Adhesion and Adhesives; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-1-119-84670-3. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Bouzidi, L.; Narine, S.S. Current Research and Development Status and Prospect of Hot-Melt Adhesives: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 7524–7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; González-Rodríguez, S.; Vetroni Barros, M.; Salvador, R.; de Francisco, A.C.; Moro Piekarski, C.; Moreira, M.T. Recent Developments in Bio-Based Adhesives from Renewable Natural Resources. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A. Recent Developments in Eco-Efficient Bio-Based Adhesives for Wood Bonding: Opportunities and Issues. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2006, 20, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandra Heinrich, L. Future Opportunities for Bio-Based Adhesives—Advantages beyond Renewability. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1866–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovone, G.; Dudaryeva, O.Y.; Marco-Dufort, B.; Tibbitt, M.W. Engineering Hydrogel Adhesion for Biomedical Applications via Chemical Design of the Junction. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 4048–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Song, S.; Ren, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, Y. Supramolecular Adhesive Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5604–5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Huang, Z.; Haq, F.; Teng, L.; Jin, M.; Ding, B. Recent Advances on Designs and Applications of Hydrogel Adhesives. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Wang, J.; Cong, Y.; Fu, J. Recent Progress in Polymer Hydrogel Bioadhesives. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 1312–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEICA (Association of the European Adhesive &Sealant Industry). The European Adhesive and Sealant Industry Facts & Figures 2014. Available online: https://www.feica.eu/application/files/4315/4089/9443/factandfigures14.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- FEICA (Association of the European Adhesive & Sealant Industry). The European Adhesive and Sealant Industry Facts & Figures 2020. Available online: https://www.vlk.nu/stream/feica-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- The Business Research Company. Adhesives Market Report 2025—Key Trends and Growth Insights. Available online: https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/adhesives-global-market-report (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence. Adhesives Market Size & Share Analysis—Industry Research Report—Growth Trends. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/global-adhesives-market (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Expert Market Research. Adhesives and Sealants Industry Trends and Innovations. Available online: https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/reports/adhesives-and-sealants-market-innovations (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Expert Market Research. Sealants and Adhesives Market Size, Share, Trends, 2034. Available online: https://www.expertmarketresearch.com/reports/sealants-adhesives-market (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Straits Research. Adhesives and Sealants Market|Forecast, Drivers, and Challenges By 2033. Available online: https://straitsresearch.com/report/adhesives-and-sealants-market (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Mordor Intelligence. Adhesives Market Share, Size & Growth Outlook to 2030. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/global-adhesives-market (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Future Market Insights. Industrial Adhesives Market|Global Market Analysis Report—2035. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/industrial-adhesives-market (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Market Data Forecast. Automotive Adhesives & Sealants Market Size Report, 2033. Available online: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/automotive-adhesives-and-sealants-market (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Market Data Forecast. Europe Adhesives and Sealants Market Size & Growth, 2033. Available online: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/europe-adhesives-sealants-market (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Market Data Forecast. Surgical Sealants and Adhesives Market Size, 2033. Available online: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/surgical-sealants-and-adhesives-market (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Global Market Insights. Adhesives and Sealants Market Report (2024). Available online: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/adhesives-and-sealants-market-report (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Ceresana. Adhesives Market Analysis 2032—Global. Available online: https://ceresana.com/en/produkt/adhesives-market-report-world (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Pal, T.S.; Raut, S.K.; Singha, N.K. Mussel-Inspired Catechol-Functionalized EVA Elastomers for Specialty Adhesives; Based on Triple Dynamic Network. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 2516–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Z.; Rui, Z. Dynamic Covalent Adhesives and Their Applications: Current Progress and Future Perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 497, 154710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condò, I.; Giannitelli, S.M.; Lo Presti, D.; Cortese, B.; Ursini, O. Overview of Dynamic Bond Based Hydrogels for Reversible Adhesion Processes. Gels 2024, 10, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, M.; Fan, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Z. Bio-Inspired Reversible Underwater Adhesive. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.L.; Wong, Y.J.; Ong, N.W.X.; Leow, Y.; Wong, J.H.M.; Boo, Y.J.; Goh, R.; Loh, X.J. Adhesion Evolution: Designing Smart Polymeric Adhesive Systems with On-Demand Reversible Switchability. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 24682–24704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Feng, K.; Yang, R.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H.; Shi, N.; Wei, Z.; Ren, H.; Ma, Y. Multifunctional Adhesive Hydrogels: From Design to Biomedical Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2403734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.Y.; Bei, H.P.; Zhao, X. Underwater and Wet Adhesion Strategies for Hydrogels in Biomedical Applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Advances in Crosslinking Strategies of Biomedical Hydrogels. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, V.G.; Burdick, J.A. Chemically Modified Biopolymers for the Formation of Biomedical Hydrogels. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 10908–10949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, A.S.; Premanand, R.; Ragupathi, I.; Bhaviripudi, V.R.; Aepuru, R.; Kannan, K.; Shanmugaraj, K. Comprehensive Review of Hydrogel Synthesis, Characterization, and Emerging Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Gelli, R.; Tamantini, S.; Bonini, M. Alginate Crosslinking beyond Calcium: Unlocking the Potential of a Range of Divalent Cations for Fiber Formation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordi, P.; Ridi, F.; Samorì, P.; Bonini, M. Cation-Alginate Complexes and Their Hydrogels: A Powerful Toolkit for the Development of Next-Generation Sustainable Functional Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelli, R.; Del Buffa, S.; Tempesti, P.; Bonini, M.; Ridi, F.; Baglioni, P. Multi-Scale Investigation of Gelatin/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Interactions in Water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 532, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugnaini, G.; Gelli, R.; Mori, L.; Bonini, M. How to Cross-Link Gelatin: The Effect of Glutaraldehyde and Glyceraldehyde on the Hydrogel Properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 9192–9202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirtzel, J.; Leks, G.; Favre, J.; Frisch, B.; Talon, I.; Ball, V. Strongly Metal-Adhesive and Self-Healing Gelatin@Polydopamine-Based Hydrogels with Long-Term Antioxidant Activity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Cui, T.; Xu, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Liu, S.; Tang, J.; Tang, L. Smart Antifreeze Hydrogels with Abundant Hydrogen Bonding for Conductive Flexible Sensors. Gels 2022, 8, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Sariola, V.; Zhao, J.; Ding, H.; Sitti, M.; Bettinger, C.J. Composition—Dependent Underwater Adhesion of Catechol—Bearing Hydrogels. Polym. Int. 2016, 65, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Duan, X.; Su, X.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, A.; Wan, Z.; Wang, H.; Wei, P.; Zhao, B.; Liu, X.; et al. Catch Bond-Inspired Hydrogels with Repeatable and Loading Rate-Sensitive Specific Adhesion. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 21, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bai, R.; Chen, B.; Suo, Z. Hydrogel Adhesion: A Supramolecular Synergy of Chemistry, Topology, and Mechanics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1901693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polymeric Tissue Adhesives|Chemical Reviews. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00798 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Bouten, P.J.M.; Zonjee, M.; Bender, J.; Yauw, S.T.K.; van Goor, H.; van Hest, J.C.M.; Hoogenboom, R. The Chemistry of Tissue Adhesive Materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1375–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Lao, J.; Gao, H.; Yu, J. Hydrogels for Flexible Electronics. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 9681–9693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Q.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, D. Adhesion Mechanism and Application Progress of Hydrogels. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 173, 111277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Dean, K.; Li, L. Polymer Blends and Composites from Renewable Resources. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packham, D.E. Adhesive Technology and Sustainability. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2009, 29, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, K.R.; Kilpatrick, A.F.R.; Harper, G.D.J.; Walton, A.; Abbott, A.P. Debondable Adhesives and Their Use in Recycling. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 36–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Wan, G. Sustainable Adhesives: Bioadhesives, Chemistries, Recyclability, and Reversibility. In Advances in Structural Adhesive Bonding, 2nd ed.; Woodhead Publishing in Materials; Dillard, D.A., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 953–985. ISBN 978-0-323-91214-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zöller, K.; To, D.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Biomedical Applications of Functional Hydrogels: Innovative Developments, Relevant Clinical Trials and Advanced Products. Biomaterials 2025, 312, 122718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, A.; Bussa, M.; Röder, H. A Review of Environmental Assessments of Biobased against Petrochemical Adhesives. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Understanding REACH—ECHA. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/regulations/reach/understanding-reach (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- McDonough, K.; Hall, M.J.; Wilcox, A.; Menzies, J.; Brill, J.; Morris, B.; Connors, K. Application of Standardized Methods to Evaluate the Environmental Safety of Polyvinyl Alcohol Disposed of down the Drain. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 1693–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Ren, X.; Zhu, X.; Fan, D. A Fully Bio-Based Adhesive with High Bonding Strength, Low Environmental Impact, and Competitive Economic Performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 153198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhesive Standards—Standards Products—Standards & Publications—Products & Services. Available online: https://store.astm.org/products-services/standards-and-publications/standards/adhesive-standards.html (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Tonelli, M.; Gelli, R.; Giorgi, R.; Pierigè, M.I.; Ridi, F.; Baglioni, P. Cementitious Materials Containing Nano-Carriers and Silica for the Restoration of Damaged Concrete-Based Monuments. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 49, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raos, G.; Zappone, B. Polymer Adhesion: Seeking New Solutions for an Old Problem. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 10617–10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, Z.; Qu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, Y.; Xu, W.; Ren, C. A Review on Recent Advances in Gel Adhesion and Their Potential Applications. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 325, 115254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiral, M. Strength in Adhesion: A Multi-Mechanics Review Covering Tensile, Shear, Fracture, Fatigue, Creep, and Impact Behavior of Polymer Bonding in Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.; Tsai, L.-C.; Haider, M.I.; Yazdi, A.; Sanatizadeh, E.; Salowitz, N.P. Quantitative Peel Test for Thin Films/Layers Based on a Coupled Parametric and Statistical Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Fleury, A.; Villey, R.; Creton, C.; Ciccotti, M. Linking Peel and Tack Performances of Pressure Sensitive Adhesives. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 3267–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Hwang, D.; Wan, G.; Niu, Z.; Ellison, C.J.; Francis, L.F.; Calabrese, M.A. Mechanics of Peeling Adhesives from Soft Substrates: A Review. J. Appl. Mech. 2025, 92, 020801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, M.D.; Case, S.W.; Kinloch, A.J.; Dillard, D.A. Peel Tests for Quantifying Adhesion and Toughness: A Review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 137, 101086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.-Y.; Hwang, S.-K.; Cho, K.-H.; Kim, H.-J.; Cho, C.-S. Progress of Tissue Adhesives Based on Proteins and Synthetic Polymers. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.D.Q.; Dejean, S.; Nottelet, B.; Gautrot, J.E. Mechanical Evaluation of Hydrogel–Elastomer Interfaces Generated through Thiol–Ene Coupling. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandin, A.; Murugesan, Y.; Torresan, V.; Ulliana, L.; Citron, A.; Contessotto, P.; Battilana, G.; Panciera, T.; Ventre, M.; Netti, A.P.; et al. Simple yet Effective Methods to Probe Hydrogel Stiffness for Mechanobiology. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghuwanshi, V.S.; Garnier, G. Characterisation of Hydrogels: Linking the Nano to the Microscale. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 274, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Amiery, A.A.; Fayad, M.A.; Abdul Wahhab, H.A.; Al-Azzawi, W.K.; Mohammed, J.K.; Majdi, H.S. Interfacial Engineering for Advanced Functional Materials: Surfaces, Interfaces, and Applications. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Fu, Q.-Q.; Wang, M.-H.; Gao, H.-L.; Dong, L.; Zhou, P.; Cheng, D.-D.; Chen, Y.; Zou, D.-H.; He, J.-C.; et al. Designing Nanohesives for Rapid, Universal, and Robust Hydrogel Adhesion. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megone, W.; Roohpour, N.; Gautrot, J.E. Impact of Surface Adhesion and Sample Heterogeneity on the Multiscale Mechanical Characterisation of Soft Biomaterials. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetter, F.W.S.; Kienle, S.; Krysiak, S.; Hugel, T. Investigating Single Molecule Adhesion by Atomic Force Spectroscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 96, 52456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Han, J.-Q.; Yan, Y.; Yu, M.-N.; Feng, Q.-Y.; Xie, L.-H. Nanomechanical Characterization via Atomic Force Microscopy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 55689–55705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioinspired Chemical Design to Control Interfacial Wet Adhesion: Chem. Available online: https://www.cell.com/chem/fulltext/S2451-9294%2823%2900082-7?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Eral, H.B.; ’T Mannetje, D.J.C.M.; Oh, J.M. Contact Angle Hysteresis: A Review of Fundamentals and Applications. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2013, 291, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyen, M.L. Mechanical Characterisation of Hydrogel Materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 2014, 59, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Zuo, A.; Guo, J. Bioadhesion Design of Hydrogels: Adhesion Strategies and Evaluation Methods for Biological Interfaces. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2023, 37, 335–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.F.; Kiefer, H.; Dalgliesh, R.; Gradzielski, M.; Netz, R.R. Nanoscopic Interfacial Hydrogel Viscoelasticity Revealed from Comparison of Macroscopic and Microscopic Rheology. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 4758–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Water as a Probe of the Colloidal Properties of Cement|Langmuir. Available online: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02304 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Voinova, M.V.; Rodahl, M.; Jonson, M.; Kasemo, B. Viscoelastic Acoustic Response of Layered Polymer Films at Fluid-Solid Interfaces: Continuum Mechanics Approach. Phys. Scr. 1999, 59, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, M.C. Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring: Enabling Real-Time Characterization of Biological Materials and Their Interactions. J. Biomol. Tech. 2008, 19, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tonda-Turo, C.; Carmagnola, I.; Ciardelli, G. Quartz Crystal Microbalance with Dissipation Monitoring: A Powerful Method to Predict the in Vivo Behavior of Bioengineered Surfaces. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, Z.; Hakobyan, K.; Li, W.; Gu, Z.; Peng, S.; Liang, K.; Xu, J. Rapid, Tough, and Trigger—Detachable Hydrogel Adhesion Enabled by Formation of Nanoparticles In Situ. Small 2024, 20, 2310572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Yang, J.; Suo, Z. Fatigue of Hydrogels. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2019, 74, 337–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvinen, J.; Kellomäki, M. Characterization of Self-Healing Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 181, 111641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Huang, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhuang, D.; Liu, H.; Huang, C.; Wu, X.; Cui, X. A Strong Underwater Adhesive That Totally Cured in Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wei, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, C.; Peng, H.; Wang, D.; Yuan, J.; Waite, J.H.; Zhao, Q. A Cation—Methylene—Phenyl Sequence Encodes Programmable Poly (Ionic Liquid) Coacervation and Robust Underwater Adhesion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2105464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, D.; Zhao, X.; Luo, J.; Wang, H.; Jia, P. Underwater Adhesive HPMC/SiW-PDMAEMA/Fe3+ Hydrogel with Self-Healing, Conductive, and Reversible Adhesive Properties. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Jia, Y.; Sun, S.; Xu, Y.; Minsky, B.B.; Stuart, M.A.C.; Cölfen, H.; Von Klitzing, R.; Guo, X. Mineral-Enhanced Polyacrylic Acid Hydrogel as an Oyster-Inspired Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Adhesive. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 10471–10479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, S.; Li, B.; Yu, B.; Lee, H.; Cai, M.; Gorb, S.N.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Gecko’s Feet-Inspired Self-Peeling Switchable Dry/Wet Adhesive. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 2785–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, C.; Wu, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, X.; Sun, C.; Jiang, P.; Wang, X. 3D Printing of Octopi-Inspired Hydrogel Suckers with Underwater Adaptation for Reversible Adhesion. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 457, 141268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Um, D.; Lee, Y.; Lim, S.; Kim, H.; Ko, H. Octopus—Inspired Smart Adhesive Pads for Transfer Printing of Semiconducting Nanomembranes. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7457–7465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.; Sun, T.L.; Chen, L.; Takahashi, R.; Shinohara, G.; Guo, H.; King, D.R.; Kurokawa, T.; Gong, J.P. Tough Hydrogels with Fast, Strong, and Reversible Underwater Adhesion Based on a Multiscale Design. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Lee, S.H.; Seong, M.; Kwak, M.K.; Jeong, H.E. Bioinspired Reversible Hydrogel Adhesives for Wet and Underwater Surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. B 2018, 6, 8064–8070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Shi, K.; Yang, B.; Liu, S.; Wu, Z.; Xue, L. Switchable Adhesion of Micropillar Adhesive on Rough Surfaces. Small 2019, 15, 1904248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Hao, L.; Qiu, X.; Wu, J.; Chang, H.; Kuang, G.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Dai, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. An Injectable Rapid—Adhesion and Anti—Swelling Adhesive Hydrogel for Hemostasis and Wound Sealing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2207741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Baidya, A.; Annabi, N. Molecular Design of an Ultra-Strong Tissue Adhesive Hydrogel with Tunable Multifunctionality. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 29, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuk, H.; Varela, C.E.; Nabzdyk, C.S.; Mao, X.; Padera, R.F.; Roche, E.T.; Zhao, X. Dry Double-Sided Tape for Adhesion of Wet Tissues and Devices. Nature 2019, 575, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Hakamivala, A.; Xu, C.; Hariharan, P.; Radionov, B.; Huang, Z.; Liao, J.; Tang, L.; Zimmern, P.; Nguyen, K.T.; et al. Biodegradable Nanoparticles Enhanced Adhesiveness of Mussel—Like Hydrogels at Tissue Interface. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2018, 7, 1701069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, D.; Chen, X.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, D.; Kaneko, D.; Kaneko, T.; Hua, Z. Mussel-Inspired Epoxy Bioadhesive with Enhanced Interfacial Interactions for Wound Repair. Acta Biomater. 2021, 136, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R. Robust-Adhesion and High-Mechanical Strength Hydrogel for Efficient Wet Tissue Adhesion. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 2469–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, G.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Lei, I.M.; Lin, J.; Xu, B.B.; Liu, J. Hydrogel Bioadhesives with Extreme Acid—Tolerance for Gastric Perforation Repairing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2202285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiguchi, A.; Kurihara, Y.; Taguchi, T. Underwater-Adhesive Microparticle Dressing Composed of Hydrophobically-Modified Alaska Pollock Gelatin for Gastrointestinal Tract Wound Healing. Acta Biomater. 2019, 99, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y. Robust Hydrogel Adhesives for Emergency Rescue and Gastric Perforation Repair. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 19, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Xiang, L.; Liu, C.; Diaz-Dussan, D.; Du, Z.; Asha, A.B.; Yang, W.; Peng, Y.-Y.; Pan, M.; et al. Injectable Self-Healing Hydrogel via Biological Environment-Adaptive Supramolecular Assembly for Gastric Perforation Healing. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 9913–9923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Grinstaff, M.W. Advances in Hydrogel Adhesives for Gastrointestinal Wound Closure and Repair. Gels 2023, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xie, R.; Zhu, J.; Wu, J.; Hui, J.; Zheng, X.; Huo, F.; Fan, D. A Temperature Responsive Adhesive Hydrogel for Fabrication of Flexible Electronic Sensors. npj Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Tian, Z. Temperature-Mediated Phase Separation Enables Strong yet Reversible Mechanical and Adhesive Hydrogels. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 13948–13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Hu, T.; Lei, Q.; He, J.; Ma, P.X.; Guo, B. Stimuli-Responsive Conductive Nanocomposite Hydrogels with High Stretchability, Self-Healing, Adhesiveness, and 3D Printability for Human Motion Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 6796–6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, K.; Liu, J. Thermoresponsive Dynamic Wet-Adhesive Epidermal Interface for Motion-Robust Multiplexed Sweat Biosensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 290, 117949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, W. Highly Adhesive, Stretchable, and Antifreezing Hydrogel with Excellent Mechanical Properties for Sensitive Motion Sensors and Temperature-/Humidity-Driven Actuators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 38205–38215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Han, H.; Zheng, H.; Xu, W.; Wang, Z. Dopamine-Triggered Hydrogels with High Transparency, Self-Adhesion, and Thermoresponse as Skinlike Sensors. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelli, R.; Del Buffa, S.; Tempesti, P.; Bonini, M.; Ridi, F.; Baglioni, P. Enhanced Formation of Hydroxyapatites in Gelatin/Imogolite Macroporous Hydrogels. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 511, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Gelli, R.; Ridi, F.; Bonini, M. A Bioinspired and Sustainable Route for the Preparation of Ag-Crosslinked Alginate Fibers Decorated with Silver Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 326, 121586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Ridi, F.; Bonini, M. A Green and Sustainable Approach for the Preparation of Cu-Containing Alginate Fibers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 677, 132396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Montes-García, V.; Tamayo, A.; Bonini, M.; Samorì, P.; Ciesielski, A. Ionically Tunable Gel Electrolytes Based on Gelatin-Alginate Biopolymers for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Small 2025, 21, 2503937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Tordi, P.; Tamayo, A.; Han, B.; Bonini, M.; Samorì, P. Mimicking Synaptic Plasticity: Optoionic MoS2 Memory Powered by Biopolymer Hydrogels as a Dynamic Cations Reservoir. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e09607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Tamayo, A.; Jeong, Y.; Bonini, M.; Samorì, P. Multiresponsive Ionic Conductive Alginate/Gelatin Organohydrogels with Tunable Functions. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tordi, P.; Tamayo, A.; Jeong, Y.; Han, B.; Al Kayal, T.; Cavallo, A.; Bonini, M.; Samorì, P. Fully Bio-Based Gelatin Organohydrogels via Enzymatic Crosslinking for Sustainable Soft Strain and Temperature Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e20762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Song, W.; Yu, B.; Liu, H. Rational Design in Functional Hydrogels towards Biotherapeutics. Mater. Des. 2022, 223, 111086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mao, A.; Guan, Q.; Saiz, E. Nature-Inspired Adhesive Systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 8240–8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Yang, X.; Lai, P.; Shang, L. Bio-inspired Adhesive Hydrogel for Biomedicine—Principles and Design Strategies. Smart Med. 2022, 1, e20220024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Meng, J.; Gu, Z.; Wan, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, S. Bioinspired Multiscale Wet Adhesive Surfaces: Structures and Controlled Adhesion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1905287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H. Getting Glued in the Sea. Polym. J. 2023, 55, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Norikane, Y.; Nishibori, E. Biomimetic Adhesion/Detachment Using Layered Polymers with Light—Induced Rapid Shape Changes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202503748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.H.; Van Hilst, Q.; Cui, X.; Ramaswamy, Y.; Woodfield, T.; Rnjak-Kovacina, J.; Wise, S.G.; Lim, K.S. From Adhesion to Detachment: Strategies to Design Tissue--Adhesive Hydrogels. Adv. NanoBiomed. Res. 2024, 4, 2300090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dai, C.; Fan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Guan, P.; Tian, Y.; Xing, J.; Li, X.; et al. Injectable Self—Healing Natural Biopolymer—Based Hydrogel Adhesive with Thermoresponsive Reversible Adhesion for Minimally Invasive Surgery. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2007457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, H.; Cui, X.; Shao, J.; Yao, P.; Huang, J.; Qiu, X.; Huang, C. A Multi-Functional Reversible Hydrogel Adhesive. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 593, 124622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, T.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, R.; Fu, J. Tough, Adhesive, Self-Healable, and Transparent Ionically Conductive Zwitterionic Nanocomposite Hydrogels as Skin Strain Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 3506–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, L.; Fu, J. Stretchable, Self-Healing and Tissue-Adhesive Zwitterionic Hydrogels as Strain Sensors for Wireless Monitoring of Organ Motions. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 1872–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Zhao, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ma, P.X.; Guo, B. Antibacterial Adhesive Injectable Hydrogels with Rapid Self-Healing, Extensibility and Compressibility as Wound Dressing for Joints Skin Wound Healing. Biomaterials 2018, 183, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Li, L.; Gao, S.-Y.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, S.; Chen, P.-F.; Lai, W.-Y. 3D Printable Conductive Polymer Hydrogels with Ultra-High Conductivity and Superior Stretchability for Free-Standing Elastic All-Gel Supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, B.; Sun, S.; Wu, P. Peeling–Stiffening Self—Adhesive Ionogel with Superhigh Interfacial Toughness. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shioya, M.; Kuroyanagi, Y.; Ryu, M.; Morikawa, J. Analysis of the Adhesive Properties of Carbon Nanotube- and Graphene Oxide Nanoribbon-Dispersed Aliphatic Epoxy Resins Based on the Maxwell Model. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2018, 84, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanism | Description | Typical Systems/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical interlocking | Adhesive penetrates surface roughness, pores, or undercuts, providing anchoring once hardened | Porous/rough substrates. Wood, textiles, etched metals. Nanocellulose-based wood adhesives, starch/protein blends, bio-inspired micropillar or fibrillar surfaces. |

| Adsorption/Wetting | Molecular forces (van der Waals, H-bonding, dipole–dipole, acid–base) dominate; spreading governed by surface energy and contact angle | Liquid adhesives on smooth surfaces, coatings, and sealants. Chitosan or gelatin hydrogels, catechol-functional adhesives, bio-polyurethane dispersions, plant-derived polysaccharide adhesives. |

| Electrostatic | Adhesion arises from formation of an electrical double layer, generating Coulombic attraction | Polymers, ceramics, charged surfaces. Alginate–chitosan polyelectrolyte complexes, charged hydrogel interfaces, ionic coordination hydrogels |

| Diffusion | Polymer chains interpenetrate across interface, forming entangled interphase | Polymer–polymer interfaces. Thermoplastics, hydrogel adhesives. Interpenetrating-network hydrogels, reversible hydrogels, thermoresponsive systems. |

| Chemical bonding | Covalent, ionic, or coordination bonds form between adhesive and substrate functional groups | Epoxy resins on hydroxylated surfaces, metal–organic adhesives, catechol–metal coordination hydrogels, Schiff-base chitosan/gelatin adhesives, enzyme-cured bioadhesives. |

| Thermodynamic | Adhesion interpreted as minimization of interfacial free energy; spreading coefficient governs stability | General principle for liquid spreading and interface energetics. Bio-emulsified adhesive systems, surfactant-modified biopolymers, low-surface-tension bio-derived formulations |

| Mechanism | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supramolecular assembly | Catechol-metal coordination, boronic ester covalent bonding and hydrogen bonding [96]. | Strong wet adhesion, reversibility. | Environmental sensitivity. |

| Dynamic covalent bonds | Transesterification, disulfide bond, boronic ester bonds, Schiff base, Diels-Alder, and others [97]. | Self-healing, shape-memory, stress-relaxation, enhanced malleability and recycling. | Environmental sensitivity, chemical and engineering complexities |

| Self-healing polymer networks | H-bonding, host–guest interaction, metal–ligand coordination, π-π stacking, and electrostatic interactions [20,21,98]. | Versatility, reversibility. | Limited strength of adhesion and mechanical robustness. |

| Interfacial adaptability (van der Waals forces) | Gecko-inspired micro- and nano-structured fibrillar surfaces [36]. | No chemical modification required, reversibility upon mechanical action, adaptability to irregular surfaces | Low load capacity; environmental sensitivity. |

| Test Type | Geometry | Measured Property | Typical Instrumentation | Typical Application | Relevance for Hydrogels |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peel | 90° or 180° separation | Peel strength (N m−1) | UTM with peel fixture, texture analyzer | Thin films, biomedical patches | Sensitive to viscoelastic dissipation and hydration |

| Tack | Contact/ retraction | Peak adhesion force (N) | Probe-tack tester, rheometer (tack mode) | Instant bonding (skin, robotics) | Captures rapid reversible bonding |

| Shear/Lap Shear | Parallel loading | Shear strength (MPa) | UTM with lap joint clamps | Structural, cohesive tests | Evaluates durability and cyclic recovery |

| Tensile/Compression | Uniaxial loading | Stress–strain behavior, modulus | UTM, microforce tester | Bulk mechanical performance | Relates network elasticity to adhesion stability |

| System Examples | Typical Characterization | Experimental Details | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underwater adhesives [158,159,160,161] | Underwater adhesion strength | UTM lap-shear test, 5–50 mm/min, different adhesion times, various substrates | 15–300 kPa |

| Bioinspired structured hydrogels [162,163,164,165,166,167] | Adhesion strength | Various devices, dry and wet environment | ~50–280 kPa |

| Self-healing adhesives for wound closure [168,169,170,171,172,173] | Lap-shear strength, porcine skin tissue | ASTM F2255 | 33–160 kPa |

| Burst pressure | ASTM F2392 | >200 mmHg | |

| Acid-tolerant injectable bioadhesives [174,175,176,177,178] | Adhesion strength | Various devices and tissues | 6–120 kPa |

| Burst pressure | Custom-made setup | ~250 mm Hg | |

| Physically responsive wearable adhesives [179,180,181,182,183,184] | Lap-shear adhesion strength | Self-adhesion, UTM, tensile test machine; skin tissues or solid substrates | 3–120 kPa adhesion force, load-bearing capacity of 100–200 g |

| Adaptability | Tests on volunteers | Good adhesion, easy peel off without residue/irritation | |

| Cyclic retention | 3–10 cycles, 2–3 days tests | Little adhesion strength fluctuations (0–15%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tonelli, M.; Bonini, M. Hydrogels as Reversible Adhesives: A Review on Sustainable Design Strategies and Future Prospects. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060084

Tonelli M, Bonini M. Hydrogels as Reversible Adhesives: A Review on Sustainable Design Strategies and Future Prospects. Colloids and Interfaces. 2025; 9(6):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060084

Chicago/Turabian StyleTonelli, Monica, and Massimo Bonini. 2025. "Hydrogels as Reversible Adhesives: A Review on Sustainable Design Strategies and Future Prospects" Colloids and Interfaces 9, no. 6: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060084

APA StyleTonelli, M., & Bonini, M. (2025). Hydrogels as Reversible Adhesives: A Review on Sustainable Design Strategies and Future Prospects. Colloids and Interfaces, 9(6), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060084