Atomically Dispersed Pt–Sn Nanocluster Catalysts for Enhanced Toluene Hydrogenation in LOHC Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Catalyst Preparation

2.3.1. Pt/TiO2 Atomically Dispersed Nanocluster Catalyst

2.3.2. Sn/TiO2 Atomically Dispersed Nanocluster Catalyst

2.3.3. Pt–Sn/TiO2 Atomically Dispersed Nanocluster Catalyst

2.4. Catalyst Performance Analysis Methods

2.4.1. Toluene Hydrogenation

2.4.2. Catalyst Stability

2.4.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

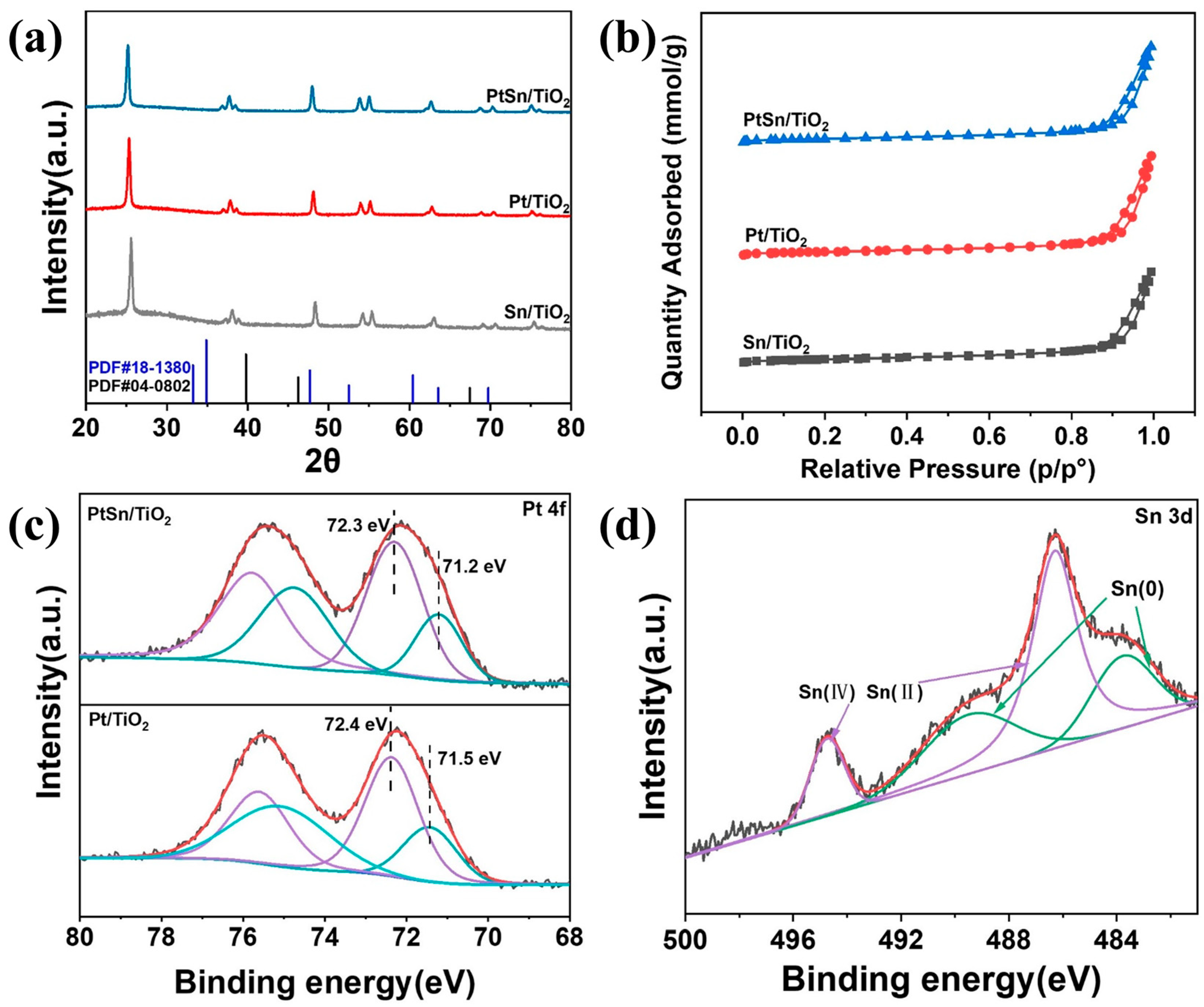

3.1. Catalyst Characterization

3.2. Catalytic Performance Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brandon, N.P.; Kurban, Z. Clean Energy and the Hydrogen Economy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2017, 375, 20160400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarhan, C.; Çil, M.A. A Study on Hydrogen, the Clean Energy of the Future: Hydrogen Storage Methods. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, L.; Daiyan, R.; Amal, R. A Green Hydrogen Credit Framework for International Green Hydrogen Trading Towards a Carbon Neutral Future. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ahn, J.; Choi, D.G.; Park, S.Y. Analysis of the Role of Hydrogen Energy in Achieving Carbon Neutrality by 2050: A Case Study of the Republic of Korea. Energy 2024, 304, 132023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, R.T.; Schrag, D.P. Carbon Abatement Costs of Green Hydrogen across End-Use Sectors. Joule 2024, 8, 3281–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Keoleian, G.A.; Cooper, D.R. The Role of Hydrogen in Decarbonizing U.S. Industry: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 214, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampai, M.M.; Mtshali, C.B.; Seroka, N.S.; Khotseng, L. Hydrogen Production, Storage, and Transportation: Recent Advances. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 6699–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, M.K.; Singh, T.P.; Kalita, P.; Dewan, A. Sustainable Hydrogen Generation and Storage—A Review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 25253–25275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Uratani, J.; Huang, Y.; Xu, L.; Griffiths, S.; Ding, Y. Hydrogen Liquefaction and Storage: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176, 113204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Tang, S.; Sha, F.; Han, Z.; Feng, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Insights into the Selectivity Determinant and Rate-Determining Step of CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 10399–10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, W.; Seidel, A.; Herzog, S.; Bösmann, A.; Schwieger, W.; Wasserscheid, P. Macrokinetic Effects in Perhydro-N-Ethylcarbazole Dehydrogenation and H2 productivity Optimization by Using Egg-Shell Catalysts. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3013–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modisha, P.M.; Ouma, C.N.M.; Garidzirai, R.; Wasserscheid, P.; Bessarabov, D. The Prospect of Hydrogen Storage Using Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 2778–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-H.; Tran, N.; Lee, H.-J. Development of Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers for Hydrogen Storage and Transport. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider, J.L.; Su, J.; Verma, P.; El Gabaly, F.; Sugar, J.D.; Chen, L.; Chames, J.M.; Talin, A.A.; Dun, C.; Urban, J.J.; et al. Stabilized Open Metal Sites in Bimetallic Metal-Organic Framework Catalysts for Hydrogen Production from Alcohols. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 10869–10881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modisha, P.; Bessarabov, D. Aromatic Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers for Hydrogen Storage and Release. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 42, 100820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meda, U.S.; Raikar, O.M.; Acharya, A.; Kashyap S G, A.; Mahesh, R.; Shetty, T. Nuances in Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yu, H.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, Y.; Fu, K.; Xie, L.; Li, G.; Zheng, J.; et al. Nonstoichiometric Yttrium Hydride–Promoted Reversible Hydrogen Storage in a Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 974–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, G. Economic Analysis of the Seasonal Storage of Electricity with Liquid Organic Hydrides. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1999, 24, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.; Kirk, J.; Moon, S.; Ohm, T.; Lee, Y.-J.; Jang, M.; Park, L.-H.; Ahn, C.-I.; Jeong, H.; Sohn, H.; et al. Hydrogen Production from Homocyclic Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs): Benchmarking Studies and Energy-Economic Analyses. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 239, 114124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gao, R.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.-J.; Pan, L. Intrinsic Kinetics of Dibenzyltoluene Hydrogenation over a Supported Ni Catalyst for Green Hydrogen Storage. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 63, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lin, X.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Huang, J. Supported Mesoporous Pt Catalysts with Excellent Performance for Toluene Hydrogenation under Low Reaction Pressure. Mol. Catal. 2022, 524, 112341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppino, R.S.; Landers, R.; Cobo, A.J.G. Influence of Noble Metals (Pd, Pt) on the Performance of Ru/Al2O3 Based Catalysts for Toluene Hydrogenation in Liquid Phase. Appl. Catal. A 2016, 525, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Chen, H.; Cheng, Y.; Peng, M.; Qin, X.; Ji, H.; et al. Building up Libraries and Production Line for Single Atom Catalysts with Precursor-Atomization Strategy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Li, W.; Ryabchuk, P.; Junge, K.; Beller, M. Bridging Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis by Heterogeneous Single-Metal-Site Catalysts. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, B.; Wang, A.; Yang, X.; Allard, L.F.; Jiang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, T. Single-Atom Catalysis of Co Oxidation Using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Qin, Q.; Li, J.; Li, B.; He, X.; Ji, H. Comparative Study of Ptm (M=Cu, Zn, Ga, Mn, Fe, in, Ce) Bimetals on Zincosilicate for Propane Dehydrogenation Reaction. Chemistry 2024, 30, e202402764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; Liang, Z.; Chuai, H.; Wang, H.; Lou, S.N.; Su, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X. Ceria-Mediated Dynamic Sn0/Snδ+ Redox Cycle for CO2 Electroreduction. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 5033–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Kang, L.; Ma, J.; Jiang, Q.; Su, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Li, L.; Wang, A.; Liu, Z.-P.; et al. Sn1pt Single-Atom Alloy Evolved Stable PtSn/Nano-Al2O3 Catalyst for Propane Dehydrogenation. Chin. J. Catal. 2023, 48, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champness, N.R. The Future of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Dalton Trans. 2011, 40, 10311–10315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Verma, P.; Hou, K.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.S.; Guo, J.; Stavila, V.; Allendorf, M.D.; Zheng, L.; et al. Reversible Dehydrogenation and Rehydrogenation of Cyclohexane and Methylcyclohexane by Single-Site Platinum Catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.H.; Jang, K.; Kim, H.J.; Son, S.U. Near-Monodisperse Tetrahedral Rhodium Nanoparticles on Charcoal: The Shape-Dependent Catalytic Hydrogenation of Arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007, 46, 1152–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, J.N.G.; Heinroth, F.; Weber, C.C.; Masters, A.F.; Maschmeyer, T. Robust Bimetallic Pt–Ru Catalysts for the Rapid Hydrogenation of Toluene and Tetralin at Ambient Temperature and Pressure. Appl. Catal. A 2013, 454, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Wu, P. Ru Nanoparticles Entrapped in Mesopolymers for Efficient Liquid-Phase Hydrogenation of Unsaturated Compounds. Catal. Lett. 2009, 133, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Lin, H.; Chan, Q.; Zhao, Y.; He, X. Atomically Dispersed Pt–Sn Nanocluster Catalysts for Enhanced Toluene Hydrogenation in LOHC Systems. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060085

Wang J, Lin H, Chan Q, Zhao Y, He X. Atomically Dispersed Pt–Sn Nanocluster Catalysts for Enhanced Toluene Hydrogenation in LOHC Systems. Colloids and Interfaces. 2025; 9(6):85. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060085

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jun, Hao Lin, Qizhong Chan, Yaohong Zhao, and Xiaohui He. 2025. "Atomically Dispersed Pt–Sn Nanocluster Catalysts for Enhanced Toluene Hydrogenation in LOHC Systems" Colloids and Interfaces 9, no. 6: 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060085

APA StyleWang, J., Lin, H., Chan, Q., Zhao, Y., & He, X. (2025). Atomically Dispersed Pt–Sn Nanocluster Catalysts for Enhanced Toluene Hydrogenation in LOHC Systems. Colloids and Interfaces, 9(6), 85. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060085