Abstract

Accurate forecasting of inbound visitor numbers is crucial for effective planning and resource allocation in the tourism industry. Preceding forecasting algorithms primarily focused on time series analysis, often overlooking influential factors such as economic conditions. Regression models, on the other hand, face challenges when dealing with high-dimensional data. Previous autoencoders for feature selection do not simultaneously incorporate feature and target information simultaneously, potentially limiting their effectiveness in improving predictive performance. This study presents a novel approach that combines a target-concatenated autoencoder (TCA) with ensemble learning to enhance the accuracy of tourism demand predictions. The TCA method integrates the prediction target into the training process, ensuring that the learned feature representations are optimized for specific forecasting tasks. Extensive experiments conducted on the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets demonstrate that the proposed TCA method significantly outperforms traditional feature selection techniques and other advanced algorithms in terms of the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE), and coefficient of determination (R2). The results show that TCA combined with XGBoost achieves MAPE values of 3.3947% and 4.0059% for the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets, respectively, indicating substantial improvements over existing methods. Additionally, the proposed approach yields better R2 and MAE metrics than existing methods, further demonstrating its effectiveness. This study highlights the potential of TCA in providing reliable and accurate forecasts, thereby supporting strategic planning, infrastructure development, and sustainable growth in the tourism sector. Future research is advised to explore real-time data integration, expanded feature sets, and hybrid modeling approaches to further enhance the capabilities of the proposed framework.

1. Introduction

Tourism has become an essential industry in an increasingly interconnected world, significantly driving economic expansion and progress [1]. Precise predictions of inbound tourist arrivals are crucial for efficient planning and resource management within the tourism sector. These forecasts guide various strategic decisions, including infrastructure development and marketing initiatives. They are essential for optimizing the economic advantages of tourism while minimizing adverse effects on local communities and the environment.

Recent studies have proposed various methods to improve tourism demand forecasting. Xin Li et al. [2] introduced a comprehensive decomposition algorithm that effectively handles seasonality, trends, and outliers, outperforming existing methods. Shilin Xu et al. [3] developed the temporal fusion encoder–decoder (TFED) network, which enhances interpretability and accuracy through deep learning and attention mechanisms. Another study by Xin Li et al. [4] presented a transformer-based framework that integrates decomposition and Bayesian optimization for improved reliability and accuracy. Zhixue Liao et al. [5] combined empirical mode decomposition (EMD) with cooperative training to optimize neural networks for complex, nonlinear data, demonstrating superior stability and accuracy. Yunxuan Dong et al. [6] created the deep spatial–temporal enhancement tourism demand forecasting (DSTE-TDF) model, which uses convolutional filters to capture intricate spatial–temporal features, significantly outperforming traditional methods.

Despite their widespread adoption, previous tourism forecasting methods demonstrate significant drawbacks. Although proficient at detecting temporal trends, time series analysis techniques often overlook external factors such as economic indicators, social trends, and policy changes, which can substantially affect tourism demand. Conversely, regression models, while able to incorporate multiple features, often face challenges with high-dimensional data, resulting in problems like overfitting and increased computational complexity [7]. This makes models expensive to run and obscures which features are critical, complicating the interpretation and application of forecasts. These limitations underscore the need for more advanced models that integrate various influencing factors while effectively managing high-dimensional datasets.

Conventional methods like principal component analysis (PCA), non-negative matrix factorization (NMF), independent component analysis (ICA), and genetic algorithms (GAs) each have their uses but also distinct limitations in handling complex, non-linear tourism data [8]. PCA reduces dimensionality by transforming features into linearly uncorrelated components; however, it often misses non-linear relationships [9]. NMF, which produces parts-based, non-negative representations, struggles with data containing negative values, potentially missing intricate interdependencies [10]. ICA separates signals into independent subcomponents but assumes statistical independence and requires large data samples [11]. GAs optimize feature subsets through natural evolution simulation but are computationally intensive and dependent on the choice of fitness function and genetic operators [12].

Related studies on autoencoder-based feature selection have introduced innovative frameworks for enhancing supervised learning. Lei Wang et al. [13] proposed a video classification system using the loss switching fusion network (LSFNet), which combines a five-layer autoencoder with a multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifier, alternating between mean squared error (MSE) and cross-entropy to produce discriminative feature vectors. Jarrett et al. [14] introduced target-embedding autoencoders (TEAs) for high-dimensional target spaces, where the autoencoder learns latent representations that are both predictable from features and predictive of targets, improving generalization through joint optimization. Another study by Yigit et al. [15] presented a novel autoencoder-based feature selection method for predicting drug–target interactions This method focuses on human-interpretable feature weights. It effectively addresses high-dimensional data challenges, enhancing prediction accuracy and outperforming traditional methods. Thus, this method is valuable for drug discovery and design.

However, it is crucial to note that the compressed representation obtained from an autoencoder does not necessarily improve the performance of subsequent classification and regression tasks. The effectiveness of the latent representation depends on how well it captures the underlying structure of the data relevant to the specific predictive task. If the autoencoder fails to encapsulate the critical features needed for prediction, the resulting model may perform poorly. Furthermore, a notable drawback of the previous autoencoders used for feature selection is their inability to integrate both feature and target information concurrently, leading to suboptimal representations for supervised learning tasks.

To address the limitations of previous tourism forecasting algorithms and autoencoders for feature selection, this study proposes a novel target-concatenated autoencoder (TCA) combined with ensemble learning for tourism visitor forecasting. This approach effectively integrates the prediction target into the training process, ensuring that the learned feature representations are optimized for specific forecasting tasks. By doing so, it overcomes the common issues of high-dimensional data and the inability of traditional methods to consider diverse influencing factors simultaneously.

Numerous factors influence inbound tourism, including economic conditions, sociopolitical stability, exchange rates, visa policies, and flight availability [16]. Economic prosperity in a tourist’s home country typically boosts travel, while downturns reduce discretionary spending. Additionally, cultural attractions, natural landscapes, and safety perceptions are vital in attracting visitors. Seasonal trends and special events cause fluctuations in visitor numbers, necessitating dynamic tourism strategies. Emerging trends like eco-tourism and wellness tourism further evolve travel preferences and demand.

The proposed TCA method tackles the challenges of autoencoders for feature selection by concatenating the target variable with the features during the autoencoder training. This ensures that the compressed representations retain the most relevant information for the predictive task. Furthermore, by incorporating ensemble learning algorithms such as XGBoost, LightGBM, and deep neural networks (DNNs), the approach leverages the strengths of multiple models to enhance prediction accuracy and reliability. This integration effectively handles complex, high-dimensional data, leading to more accurate and reliable tourism forecasts.

The experimental results demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed TCA combined with ensemble learning algorithms in forecasting inbound tourism demand. The TCA method consistently achieved a lower mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) across various datasets, significantly outperforming traditional feature selection techniques and other advanced models. For instance, TCA combined with XGBoost achieved a MAPE of 3.39% for the Taiwan dataset and 4.00% for the Hawaii dataset, indicating substantial improvements in predictive accuracy. These results underscore the efficacy of integrating target information into the feature selection process, thereby enhancing the relevance and quality of the compressed representations. Moreover, the computational efficiency of the TCA method, along with its resilience to different hyperparameter configurations, makes it a practical solution for real-world applications. The implications of these findings are far-reaching, enabling tourism managers and policymakers to make more informed decisions regarding infrastructure development, marketing strategies, and resource allocation. This, in turn, supports the sustainable growth of the tourism sector by optimizing economic benefits while minimizing adverse impacts on local communities and environments.

The contributions of this study are threefold.

- Integration of Diverse Influencing Factors: This study addressed the challenges of previous tourism forecasting algorithms by integrating economic conditions, sociopolitical stability, and other external factors into the forecasting model. This comprehensive approach enhanced the model’s ability to capture and predict tourism demand accurately, overcoming the limitations of time series and regression models that often fail to consider these diverse influencing factors.

- Introduction of TCA for Feature Selection: This study resolved the limitations of related autoencoders for feature selection by introducing the TCA. Unlike traditional autoencoders that do not incorporate target information, TCA integrates the prediction target during the training process, ensuring that the learned representations are optimized for the specific forecasting task. This leads to more relevant and informative feature selection, improving the model’s predictive performance.

- Significant Implications for the Tourism Industry: By achieving lower MAPE and demonstrating computational efficiency, the proposed method provides a practical tool for tourism managers and policymakers. It enables accurate forecasts; facilitates better infrastructure development, marketing strategies, and resource allocation; supports sustainable growth; and minimizes negative impacts on local communities and environments.

The remainder of this paper is organized into five main sections to thoroughly explore and evaluate the proposed model. Section 2 reviews the existing literature on tourism forecasting and feature selection techniques, highlighting their applications and limitations. Section 3 details the framework of the proposed approach. Section 4, presents a comprehensive analysis of the model’s performance using a realistic tourism dataset, comparing it with conventional methods to underscore its efficacy and efficiency. Section 5 delves into the implications of the findings, addressing potential challenges and limitations of the model within broader forecasting applications. Lastly, Section 6 summarizes the key contributions of this study and suggests directions for future research in terms of improving feature selection and dimension reduction for predictive modeling in tourism and other complex domains.

2. Related Work

This section reviews the existing literature in several key areas relevant to the proposed work. First, it examines tourism demand factors and forecasting algorithms, including traditional time series analysis methods and regression models such as linear regression, support vector machines (SVMs), XGBoost, LightGBM, and various deep learning approaches. Then, it discusses the use of autoencoders for feature selection.

2.1. Tourism Demand Factors

Tourism demand is influenced by various factors. Economic indicators are significant, as an economic boom with positive consumption trends can lead to more people willing to spend on travel. Therefore, economic indicators objectively reflect economic prospects and expected consumption trends. The exchange rate plays a crucial role in the number of tourists. One study [17] noted that a country’s exchange rate system (volatility) can have both positive and negative impacts on tourism flows. Lower exchange rate volatility has a greater positive impact on tourism flows [18], especially since currency depreciation can affect inbound tourism prices [19]. Additionally, [20] used the gross domestic product (GDP), relative consumer price index (CPI), population, trade volume, and foreign exchange rate of the country of origin to predict changes in the number of arrivals. Another study [21] utilized the Purchasing Managers Index (PMI), Consumer Confidence Index (CCI), and Real Effective Exchange Rate Index (REERI) to predict the number of cruise tourists in China.

The quality and price of tourism resources significantly impact tourism motivations and destinations. One article [22] pointed out that service quality positively impacts the number of tourists; [23] highlighted that ski resort size, terrain elevation, ski lift capacity, ski lift quality, average annual snowfall, ticket costs, and accommodation costs all affect the number of tourists. One study [24] emphasized that hotel service quality has an important impact on the number of tourists, indicating that tourists consider the quality and price of hotels when choosing travel destinations [25]. The authors of [26] forecasted tourism demand using accommodation and food service prices.

Weather is a crucial condition for travel and a key attraction [27]. Generally, climate and weather conditions can motivate people to travel to resorts for vacations [28], and weather can affect the profitability of the tourism industry by influencing customer satisfaction and loyalty to the destination [29,30]. Negative weather experiences have a greater impact on tourist satisfaction than positive weather experiences [28,31].

People often search online before choosing a travel destination, resulting in a strong positive correlation between the number of online searches for a travel destination and the number of visitors to that destination. Trend data from Google and Baidu are currently used to predict the number of tourists at destinations [32,33,34] and tourist attractions [35], as well as hotel room demand [36,37]. The authors of [36] used Google to search for travel-related keywords to predict hotel room demand, while [38] used 211 Google and 45 Baidu keywords to obtain search engine data and predict travel demand in Macau.

Based on the above, numerous factors affect tourism demand. This study used the official statistics of the Republic of China as the main basis for predicting the number of tourists in Taiwan. This study refers to the exchange rate, CPI, GDP, price index, and other economic indicators; accommodation capacity; and climate factors as the main variables in predicting tourist arrivals.

2.2. Tourism Forecasting Algorithm

The accurate prediction of inbound visitor numbers significantly depends on the selection of suitable forecasting methods. Various approaches have been utilized in the literature, ranging from time series analysis to machine learning models.

Common time series techniques include exponential smoothing [39], which assigns exponentially decreasing weights to past observations, making it responsive to recent changes while considering historical data. Weighted moving average assigns different weights to past data points to smooth out short-term fluctuations and emphasize longer-term trends [40]. The grey model (GM), suitable for forecasting with limited and uncertain data, has been applied in diverse fields including tourism [41]. The autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, which integrates autoregression, differencing, and moving average components to capture various data patterns, is widely recognized for its reliability [41].

In addition to time series methods, regression or associative models are employed in tourism forecasting [42]. SVMs are effective for both classification and regression tasks, modeling complex relationships between input features and tourism demand. Ensemble learning methods like XGBoost [43] and LightGBM [44] enhance performance through gradient-boosted decision trees, efficiently and accurately handling large-scale data. Neural networks, particularly deep learning models, excel in learning complex non-linear relationships, making them highly suitable for forecasting tourism demand [42].

Xin Li et al. [2] introduced a comprehensive decomposition algorithm for tourism demand forecasting, dividing data into sub-series and applying suitable models. The framework, tested on monthly tourist arrivals in Hong Kong, outperforms existing methods in terms of accuracy, effectively handling seasonality, trends, and outliers.

Shilin Xu et al. [3] proposed the TFED network with Bayesian optimization for daily tourism demand forecasting. This deep learning model uses an encoder–decoder architecture and attention mechanisms to enhance interpretability and accuracy by analyzing factors like weather and search queries, demonstrating significant improvements in empirical studies.

Xin Li et al. [4] presented a transformer-based framework for tourism demand forecasting, integrating the tree-structured Parzen estimator, a decomposition method, and Bayesian optimization. This model improves accuracy and reliability, effectively handling outliers and enhancing interpretability with attention mechanisms, making it valuable for tourism managers.

Zhixue Liao et al. [5] introduced a framework combining EMD and a cooperative training mechanism, optimizing neural networks for each decomposed sub-series. The model, tested on tourism demand data, shows superior accuracy and stability, effectively handling complex, nonlinear time series data.

Yunxuan Dong et al. [6] developed the DSTE-TDF model, which enhances spatial–temporal features by converting data into images using convolutional filters. Tested with Zhuhai tourism data, this model outperforms traditional methods in accuracy, capturing intricate spatial–temporal features and effectively predicting dynamic tourism demand.

Despite their widespread use, previous tourism forecasting algorithms exhibit notable limitations. While effective at observing temporal patterns, time series analysis methods fail to consider external influencing factors such as economic indicators, social trends, and policy changes, which can significantly impact tourism demand. On the other hand, regression models, although capable of incorporating various features, often struggle with high-dimensional data, leading to issues like overfitting and increased computational complexity. These limitations highlight the need for more effective models that can integrate diverse influencing factors while efficiently handling high-dimensional datasets.

2.3. Autoencoder for Feature Selection

Autoencoders, a type of artificial neural network, provide a powerful non-linear feature selection and dimensionality reduction method. An autoencoder consists of an encoder and a decoder, where the encoder condenses input data into a latent-space representation and the decoder reconstructs the input from this condensed form. By learning to compress and reconstruct data, autoencoders can identify the most critical features, effectively reducing dimensionality.

Variational autoencoders (VAEs) introduce a probabilistic perspective, offering a structured latent space that is beneficial for generating new data points and enhancing feature representation [45]. Sparse autoencoders apply a sparsity constraint on hidden units, prompting the network to learn a more efficient and compact representation.

Lei Wang et al. [13] proposed a video classification system using a lightweight LSFNet that integrated a five-layer autoencoder with an MLP classifier, sharing the encoder component. Using MSE for reconstruction and cross-entropy for classification performance, the LSFNet produced discriminative feature vectors. The system processes fused spatiotemporal descriptors through similarity search and soft voting, achieving superior results on industry datasets.

Jarrett et al. [14] introduced TEA for supervised representation learning for high-dimensional target spaces. They proposed a framework where the autoencoder learns an intermediate latent representation that is predictable from features and predictive of targets. This joint optimization, minimizing both prediction and reconstruction errors, regulates and improves generalization. The TEA framework shows advantages in multivariate sequence forecasting through theoretical validation and empirical experiments.

Yigit et al. [15] introduced a novel autoencoder-based feature selection method for predicting drug–target interactions, emphasizing human-interpretable feature weights. The method addresses the challenge of high-dimensional data by using an autoencoder to identify the most relevant features, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy. This approach offers superior performance compared to traditional feature selection methods, making it a valuable tool for drug discovery and design.

However, it is important to note that the compressed representation learned by an autoencoder does not necessarily enhance the performance of subsequent classification and regression tasks. The quality of the latent representation depends on how effectively it captures the underlying structure of the data pertinent to the specific predictive task. If the autoencoder fails to encapsulate essential features required for the predictive task, the resulting model may underperform. Additionally, a significant limitation of previous autoencoders for feature selection is their simultaneous incorporation of features and target information, leading to suboptimal representation for supervised learning tasks.

3. Proposed Method: Target-Concatenated Autoencoder and Ensemble Learning

This study proposes a TCA and ensemble learning as a novel approach to enhance the performance of predictive models in tourism forecasting by combining the strengths of feature selection techniques and autoencoders. This method addresses the limitations of traditional autoencoders in feature selection by incorporating the prediction target into the training process, ensuring that the learned representations are optimized for specific forecasting tasks.

3.1. Overview of the Target-Concatenated Autoencoder and Ensemble Learning Approach

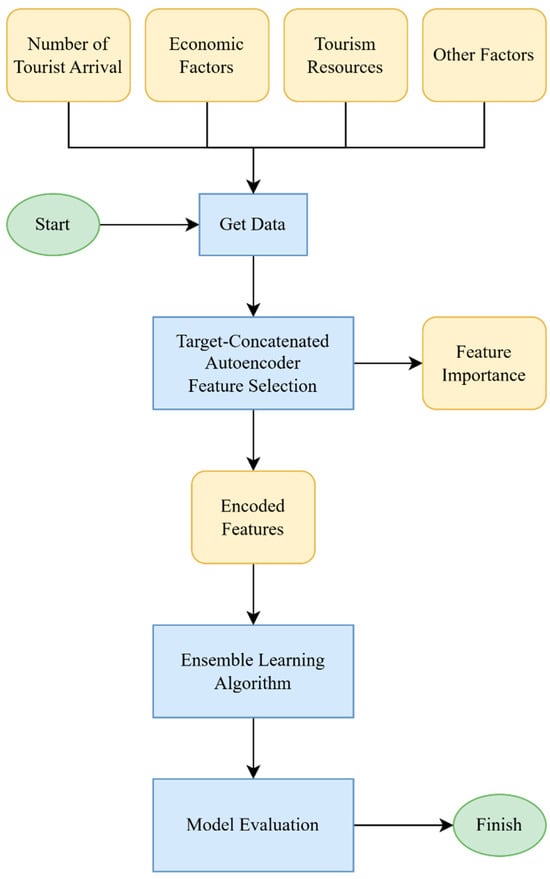

Figure 1 illustrates a step-by-step workflow of the TCA and ensemble learning approach for visitor forecasting.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the TCA and ensemble learning approach for enhanced visitor forecasting.

- Start and Obtain Data: The process begins with data collection, encompassing key variables such as the number of tourist arrivals, economic factors, tourism resources, and other influencing factors. These data points form the foundation for the forecasting model.

- Target-Concatenated Autoencoder Feature Selection: The TCA is employed at this stage. The encoder component of the autoencoder compresses the input data into a latent representation, while the decoder attempts to reconstruct the original input from this compressed form. By incorporating the target variable (e.g., visitor numbers) during training, the autoencoder learns features that represent the input data and predict the target, ensuring that the encoded features are highly relevant to the forecasting task.

- Feature Importance and Encoded Features: The encoded features generated by the autoencoder are then analyzed for their importance in predicting the target variable. This step helps identify and select the most significant features, which reduces dimensionality and enhances model interpretability.

- Ensemble Learning Algorithm: The selected encoded features are subsequently fed into an ensemble learning algorithm. Ensemble learning methods, such as XGBoost, LightGBM, or a combination of neural networks, aggregate the predictions of multiple models to improve overall prediction accuracy and reliability.

- Model Evaluation: The final step involves evaluating the performance of the ensemble model using various metrics (e.g., mean absolute error, root mean squared error, mean absolute percentage error). This evaluation ensures that the model meets the desired accuracy and reliability standards.

- Finish: The process concludes with the finalization of the model, which is ready to be deployed for forecasting visitor numbers accurately.

Combining the strengths of autoencoders and ensemble learning, this structured approach aims to provide a comprehensive solution for accurate and reliable visitor forecasting.

3.2. Architecture of Target-Concatenated Autoencoder

The architecture of the TCA was designed to enhance the representation of input features by incorporating target information during the training process. This integration ensured that the learned features represented the input data and predicted the target, leading to improved performance in forecasting tasks.

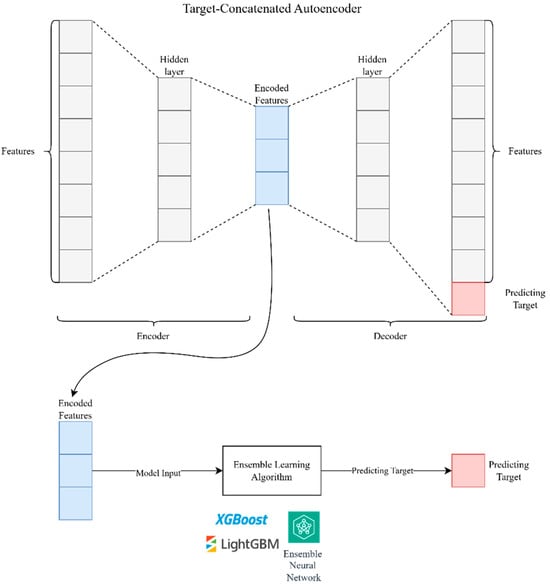

Figure 2 illustrates the detailed architecture of the TCA. The process began with the model input, which included various features relevant to visitor forecasting, such as economic factors, tourism resources, and other influencing variables.

Figure 2.

The TCA architecture for enhanced visitor forecasting.

- Encoder: The encoder component of the autoencoder compresses the input features into a latent representation. This process involves multiple layers:

- ○

- The first layer processes the original input features through a dense layer with activation functions to capture non-linear relationships.

- ○

- Subsequent layers further compress the data, reducing its dimensionality while retaining essential information.

- Target Concatenation: At a specific stage within the encoding process, the target variable (e.g., the number of tourist arrivals) is concatenated with the intermediate features. This step ensures that the autoencoder considers the target information while learning the compressed representation. By doing so, the model learns to emphasize features that are more predictive of the target, enhancing the quality of the latent representation.

- Decoder: The decoder reconstructs the original input from the latent representation, ensuring that the encoded features retain enough information to reconstruct the input accurately. This reconstruction process helps the model learn a compact yet informative data representation.

- Feature Extraction: The encoded features are extracted from the autoencoder and used for further analysis. These features are now optimized to represent the input and predict the target, making them highly valuable for subsequent modeling tasks.

In summary, the architecture of the TCA integrates the target variable during the encoding process, ensuring that the learned features are optimized for prediction tasks. Combined with ensemble learning, this approach provides a comprehensive framework for accurate and reliable visitor forecasting.

3.3. Feature Importance with Target-Concatenated Autoencoder

The TCA not only aids in dimensionality reduction and feature selection but also provides a mechanism to determine the importance of each feature in the context of the target prediction. This is achieved by analyzing the weights learned by the autoencoder during the training process.

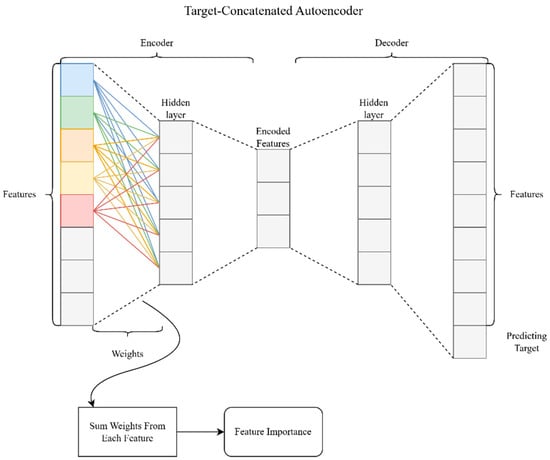

Figure 3 illustrates the process of calculating feature importance using the TCA. The workflow begins with the input features, which include various factors relevant to visitor forecasting, such as economic indicators, tourism resources, and other influencing variables.

Figure 3.

Visualization of feature importance calculation in the TCA.

- Encoder: As the input features pass through the encoder, they are transformed into a lower-dimensional latent space. During this transformation, the network learns weights that capture the relationships between the input features and the target variable. These weights are crucial as they reflect the contribution of each input feature to the encoded representation.

- Weight Analysis: To determine feature importance, this study analyzed the weights connecting the input layer to the first hidden layer of the encoder. By summing the absolute values of these weights for each feature, the impact of each feature on the latent representation could be quantified. This sum represented the overall importance of the feature in predicting the target variable.

- Feature Importance Calculation: The summed weights were then normalized to provide a relative measure of feature importance. Features with higher summed weights were deemed more significant, indicating their crucial role in the prediction task. Conversely, features with lower weights had a lesser impact.

- Output: The final output was a ranked list of features based on their importance scores. This ranking helped identify the most relevant forecasting predictor, allowing for a more focused and efficient modeling process.

To summarize, the TCA facilitates the calculation of feature importance by leveraging the weights learned during the encoding process. This method provides a clear and interpretable measure of which features are most influential in predicting the target variable, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of the forecasting model.

4. Experiment and Results

This section presents a detailed examination of the experiments conducted to assess the efficacy of the TCA and ensemble learning approach. It encompasses a description of the datasets utilized, the hyperparameters and experimental configuration, the evaluation metrics applied, an ablation study, and a comparison of the results with related works. The aim is to showcase the reliability and efficiency of the TCA and ensemble learning in forecasting inbound visitor numbers.

4.1. Dataset

Two datasets were employed in this study: the Taiwan Visitor Dataset and the Hawaii Visitor Dataset.

The Taiwan Visitor Dataset used in this study was sourced from various open and governmental data repositories:

- Taiwan National Statistics Database

- Taiwan Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Tourism Statistics

- Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Visitor Statistics

- Ministry of Transportation and Communications: Transportation Statistics

- Google Trends

- Data Taiwan

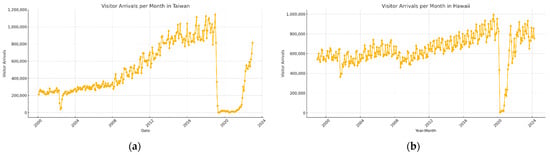

The study period spanned from 1 January 2001 to 1 December 2023, as shown in Figure 4a. Initially, 145 features were considered, covering various economic, tourism resource, and other factors potentially influencing the number of tourists arriving in Taiwan.

Figure 4.

Time series of visitor arrivals per month. (a) Visitor arrivals per month in Taiwan (2001–2023). (b) Visitor arrivals per month in Hawaii (1999–2024).

The features were categorized into three main classes: Economic Factors, Tourism Resource Factors, and Other Factors. Table 1 lists the ten most important features of each category.

Table 1.

Classification of features influencing the number of tourists arriving in Taiwan.

These classifications influence tourism for various reasons:

- Economic Factors: Economic stability and growth directly affect tourists’ disposable income and purchasing power, influencing their ability to travel. Exchange rates impact the cost of traveling to a destination, while GDP and GNI provide an overall economic context [46].

- Tourism Resources: The availability and quality of accommodation, transport infrastructure, and tourism facilities are crucial for attracting and retaining tourists. High occupancy rates indicate a healthy tourism sector, while the number of tourist establishments reflects the capacity to accommodate visitors [47,48].

- Other Factors: Weather conditions (e.g., precipitation days), crime rates, and economic indicators (e.g., export and import growth rates) also play significant roles. Favorable weather and safety enhance a destination’s appeal, while economic indicators reflect overall market conditions that can influence travel decisions.

The Hawaii Visitor Dataset sourced from the Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, covered the period from 1999 to April 2024, as shown in Figure 4b.

4.2. Hyperparameters and Experimental Setup

The experiments evaluating the TCA and ensemble learning approach were conducted on two comprehensive datasets, incorporating various features from economic indicators to tourism statistics. Data preprocessing involved several critical steps to ensure that the datasets were complete and standardized for analysis. Missing values were imputed using the median value of each column, an effective method for handling missing data. The datasets were then normalized to a feature range of 0 to 1, ensuring uniformity in the scale of all features contributing to the model training process. Following normalization, the data were split into training and testing sets at a 90:10 ratio, providing a substantial portion of data for model training while reserving a part for unbiased evaluation.

Dimensionality reduction was performed using PCA, NMF, and ICA, with the Taiwan dataset reduced to 64 components and the Hawaii dataset reduced to 12 components. This step was essential for mitigating the complexity of the datasets while retaining their most informative features.

A genetic algorithm (GA) was employed with specific settings to optimize the feature set effectively for feature selection. The GA was configured using the DEAP library [49], where attributes, individuals, population, evaluation functions, mating, mutation, and selection operators were registered. The initial population comprised 50 individuals, each represented by a binary vector indicating the presence or absence of features. Individuals were evaluated based on a custom function assessing model performance. The GA utilized a two-point crossover with a probability of 0.5 and a bit-flip mutation with a probability of 0.2 to maintain genetic diversity. Tournament selection with a size of three was employed to choose individuals for the next generation, and the algorithm ran for 40 generations to iteratively optimize the feature set. The essential hyperparameters for the GA included a population size of 50, a crossover probability of 0.5, and a mutation probability of 0.2, with the number of generations set to 40.

Linear regression, support vector machines (SVMs), XGBoost, LightGBM, and deep neural networks (DNNs) are widely used regression models for tourism demand forecasting, each offering unique strengths and challenges. Linear regression is a fundamental technique that models the relationship between independent and dependent variables linearly, but it often struggles with non-linear data patterns. Support vector machines, on the other hand, can handle non-linear relationships by using kernel functions, although they can be computationally intensive and require careful parameter tuning. XGBoost and LightGBM are gradient-boosting frameworks that build ensembles of decision trees, known for their high accuracy and efficiency, particularly in handling large-scale datasets with complex patterns. Deep neural networks excel at capturing intricate non-linear relationships due to their multi-layered architectures, but they demand substantial computational resources and risk overfitting.

To optimize the performance of these models, this study employed a grid search to tune their hyperparameters systematically. A grid search exhaustively explores the hyperparameter space, adjusting settings such as the learning rate, number of trees, maximum depth for XGBoost and LightGBM, and the number of layers and neurons for DNNs, to minimize the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE). This rigorous tuning process ensures that each model operates at its best, providing the most accurate and reliable forecasts.

The computation time for the experiments was measured on an Ubuntu 18.04.6 LTS machine equipped with a 56-core Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2690 v4 @ 2.60 GHz. Each program that was run was repeated ten times, and the average and standard deviation of the computation time were reported to ensure reliability and consistency.

This comprehensive experimental setup provided an effective framework for evaluating the effectiveness of the TCA and ensemble learning approach in forecasting inbound visitor numbers, integrating advanced preprocessing, feature selection, and predictive modeling techniques.

4.3. Evaluation Metric

The performance of the predictive models was assessed using widely recognized evaluation metrics for tourism forecasting: the MAPE, MAE, MSE, and coefficient of determination (R2). These metrics offered a comprehensive understanding of the model’s accuracy and reliability.

- Mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) quantifies prediction accuracy as a percentage, providing a scale-independent measure of error. It is computed as the average absolute percentage difference between the predicted and actual values, represented by the below formula:MAPE is particularly useful in scenarios where understanding the relative size of errors is essential. However, it can be sensitive to small actual values, potentially resulting in extremely high percentage errors.

- Mean absolute error (MAE) measures the average magnitude of errors in a set of predictions, without considering their direction. It is calculated as the average absolute difference between the predicted and actual values, represented by the below formula:MAE provides a straightforward interpretation of prediction errors, reflecting the average error magnitude in the same units as the data.

- Mean squared error (MSE) is a quadratic scoring rule that measures the average magnitude of errors. It squares the differences between predicted and actual values, averages them, and then takes the square root, represented by the below formula:MSE is particularly useful for identifying larger errors due to its quadratic nature, which penalizes significant deviations more than smaller ones. This makes MSE sensitive to outliers and provides a comprehensive measure of model accuracy.

- The coefficient of determination (R2) indicates the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables, represented by the below formula:where is the mean of the observed data. R2 values range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better model performance.

These evaluation metrics were selected to provide a balanced assessment of model performance, capturing both absolute and relative prediction errors and highlighting the models’ ability to handle large deviations while offering reliable forecasts. By employing MAPE, MAE, MSE, and R2, this study ensured a thorough evaluation of the predictive model’s effectiveness in forecasting inbound visitor numbers.

4.4. Ablation Study

This study conducted a series of ablation experiments to evaluate the contributions of various components in the TCA and ensemble learning approach. These experiments involved varying the encoding dimension of the target-concatenated autoencoder to assess the impact of different latent space sizes on model performance. Additionally, this study explored different learning rates to determine the optimal balance between training speed and stability for the autoencoder. Furthermore, various modifications to the autoencoder structures were tested, incorporating batch normalization and adjusting dropout rates to assess their impact on the model’s accuracy and reliability. Through these ablation studies, this study aimed to isolate and identify the most effective configurations for enhancing visitor forecasting.

4.4.1. Impact of Encoding Dimensions on Model Performance

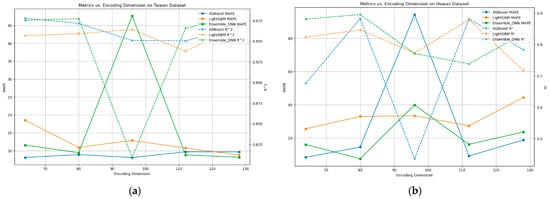

This section discusses the impact of varying encoding dimensions on the performance of the predictive models, as illustrated in Figure 5. The figure compares the MAPE and R2 across different encoding dimensions for three models: XGBoost, LightGBM, and an ensemble deep neural network (DNN) on the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets.

Figure 5.

Metrics vs. encoding dimension of target-concatenated autoencoder. (a) Metrics vs. encoding dimension on the Taiwan dataset for various models. (b) Metrics vs. encoding dimension on the Hawaii dataset for various models.

Figure 5a shows that the MAPE for XGBoost remained relatively stable across different encoding dimensions, indicating effective utilization of the encoded features irrespective of the latent space size. LightGBM exhibited more variability, with noticeable peaks and troughs, suggesting moderate sensitivity to encoding dimensions. The ensemble DNN exhibited significant fluctuations in MAPE, with a sharp increase around an encoding dimension of approximately 85, indicating poor performance at this size. However, its performance stabilized at higher dimensions, aligning more closely with the other models. The R2 values for XGBoost were consistently high, showing that it maintained a strong fit across encoding dimensions, whereas LightGBM and the ensemble DNN exhibited more variability, especially at lower encoding dimensions.

Figure 5b illustrates the MAPE and R2 for the Hawaii dataset across varying encoding dimensions. XGBoost displayed significant variability, with a sharp spike around an encoding dimension of 85, where MAPE exceeded 90%, indicating substantial performance degradation. In contrast, LightGBM demonstrated more consistent performance, with MAPE values generally ranging between 20% and 40%, indicating better stability across different encoding dimensions. The ensemble DNN exhibited fluctuations peaking around an encoding dimension of 100 but achieved lower errors beyond 110. The R2 values reflected this trend, with the ensemble DNN showing improved R2 at higher dimensions, indicating better predictive accuracy when the encoding dimension was suitably tuned.

Both figures highlight the critical role of selecting appropriate encoding dimensions to achieve optimal model performance. XGBoost’s performance was highly variable, requiring careful tuning to avoid significant errors. LightGBM exhibited greater stability but still benefited from attention to encoding dimensions. The ensemble DNN demonstrated the potential for lower errors and higher R2 with precise tuning of encoding dimensions, emphasizing the importance of finetuning to enhance the accuracy and reliability of visitor forecasting models. These findings indicate that while some models are more sensitive to encoding dimensions than others, all models can benefit from the careful selection of encoding dimensions to optimize performance.

4.4.2. Impact of Learning Rate on Model Performance

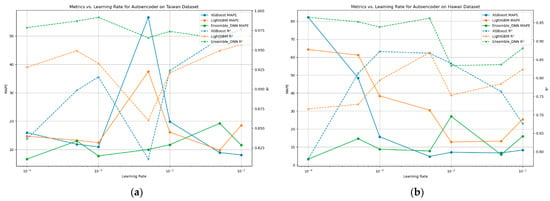

This section discusses the impact of varying learning rates on the performance of the predictive models, as shown in Figure 6. The figure compares the MAPE and R2 across different learning rates for three models: XGBoost, LightGBM, and an ensemble DNN on the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets.

Figure 6.

Metrics vs. learning rate for TCA. (a) Metrics vs. learning rate for autoencoder on Taiwan dataset for various models. (b) Metrics vs. learning rate for autoencoder on Hawaii dataset for various models.

Figure 6a shows that the performance of XGBoost demonstrated significant sensitivity to learning rate variations. A sharp increase in MAPE occurred at a learning rate of , where the error exceeded 50%, indicating that a higher learning rate leads to severe performance degradation for XGBoost. Conversely, lower learning rates ( to ) resulted in a more stable and lower MAPE, suggesting that XGBoost benefits from smaller learning rates for optimal performance. The R2 values followed an inverse trend, decreasing with higher learning rates, highlighting the model’s decreased accuracy.

LightGBM also showed variability in performance across different learning rates. Higher errors were observed at intermediate learning rates, while both lower () and higher () learning rates yielded better performance. This indicated moderate sensitivity to learning rate changes, emphasizing the need for careful tuning to achieve consistent results. The R2 values for LightGBM remained relatively stable across the learning rates but tended to improve at the lower and higher extremes.

The ensemble DNN, on the other hand, demonstrated the least variability in MAPE across different learning rates. It maintained relatively stable performance, with MAPE values generally below 20% across learning rates from to . This stability suggested that the ensemble DNN was less sensitive to changes in the learning rate, indicating reliability in its training process. The R2 values for the ensemble DNN also showed stability, reinforcing its consistent performance.

Figure 6b shows a similar trend for the Hawaii dataset. XGBoost exhibited a steep decline in MAPE as the learning rate decreased. At higher learning rates (), the MAPE was significantly high, around 80%, indicating poor performance. As the learning rate decreased to , the MAPE stabilized at around 10%, suggesting that XGBoost performs optimally at lower learning rates. The R2 values increased with lower learning rates, corroborating the improved performance.

LightGBM also showed a declining trend in MAPE with decreasing learning rates. At higher learning rates, the MAPE started at around 60% and gradually decreased, with the lowest MAPE observed at lower learning rates (), stabilizing at around 10–20%. This indicated that LightGBM benefits from smaller learning rates for better performance. The R2 values for LightGBM also improved with lower learning rates, indicating enhanced predictive accuracy.

The ensemble DNN continued to demonstrate the most stable performance across different learning rates. The MAPE remained consistently low, ranging from 10% to 20%, regardless of the learning rate. This stability further underscored the reliability of the ensemble DNN model in handling varying training conditions. The R2 values remained high and stable, further emphasizing the model’s resilience.

Both figures highlight the critical role of selecting suitable learning rates for achieving optimal model performance. XGBoost and LightGBM showed significant improvements in MAPE with lower learning rates, indicating their sensitivity to this hyperparameter. In contrast, the ensemble DNN demonstrated stable performance across all learning rates, highlighting its reliability. These findings emphasize that while tuning the learning rate is critical for models like XGBoost and LightGBM, the ensemble DNN offers a more resilient alternative, performing well even without extensive hyperparameter tuning. This insight is crucial for ensuring reliable and accurate visitor forecasting in practical applications.

4.4.3. Impact of Autoencoder Configurations on Model Performance

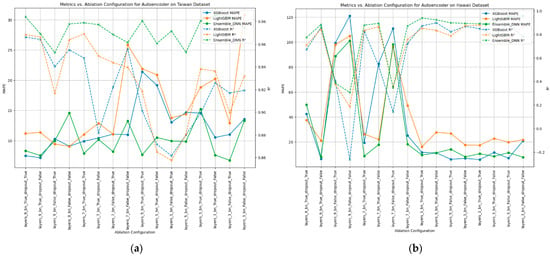

This section discusses the impact of varying ablation configurations on the performance of the predictive models, as illustrated in Figure 7. The figure compares the MAPE and R2 across different ablation configurations for three models: XGBoost, LightGBM, and an ensemble DNN on the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets.

Figure 7.

Metrics vs. ablation configuration for TCA. (a) Metrics vs. ablation configuration for autoencoder on Taiwan dataset for various models. (b) Metrics vs. ablation configuration for autoencoder on Hawaii Dataset for various models.

Figure 7a shows that XGBoost’s performance was highly variable across different ablation configurations, with MAPE ranging from around 10% to 30%. This indicated that the model was sensitive to changes in the autoencoder configuration. The R2 values for XGBoost followed a similar trend, fluctuating with the different configurations, which highlighted the importance of selecting appropriate configurations for optimal performance.

LightGBM also showed variability in performance with different ablation configurations. The MAPE ranged between approximately 10% and 25%, with the highest errors observed in configurations with fewer layers and without dropout. The R2 values for LightGBM also exhibited variability, improving with configurations that included more layers and dropout, suggesting that these configurations helped stabilize the model’s performance.

The ensemble DNN demonstrated the most stability across different ablation configurations. The MAPE remained relatively low, generally below 15%, regardless of the configuration, indicating reliability to changes in the autoencoder structure. The R2 values for the ensemble DNN were consistently high, further emphasizing the model’s ability to maintain performance across varying configurations.

Figure 7b shows similar trends for the Hawaii dataset. XGBoost’s MAPE varied significantly, with peaks reaching as high as 120%, indicating poor performance for certain configurations. The R2 values for XGBoost were correspondingly low for these configurations, underscoring the model’s sensitivity.

Similarly, LightGBM displayed a more consistent performance on the Hawaii dataset, with MAPE values mostly between 20% and 40%. The R2 values for LightGBM were relatively stable, though they improved with configurations that included dropout and more layers, indicating that these settings enhanced model reliability.

In contrast, the ensemble DNN continued to show the most consistent performance, with MAPE values generally below 20% across all configurations. The R2 values for the ensemble DNN remained high, reinforcing the model’s resilience to different ablation settings.

Both figures highlight the importance of selecting suitable ablation configurations to optimize model performance. XGBoost and LightGBM showed significant variability in performance with different configurations, indicating the need for careful tuning. Conversely, the ensemble DNN demonstrated stable performance across all configurations, demonstrating resilience even without extensive hyperparameter tuning. These findings emphasize that tuning the learning rate is critical for models like XGBoost and LightGBM. This insight is essential for ensuring reliable and accurate visitor forecasting in practical applications.

4.4.4. Performance Evaluation of the TCA + XGBoost Model on the Taiwan Dataset

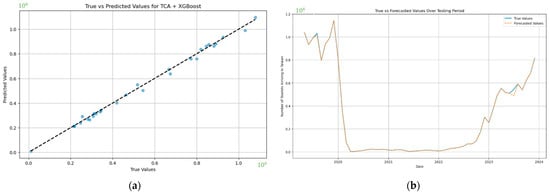

Figure 8a illustrates the performance of the TCA combined with the XGBoost model in predicting the number of tourists in Taiwan. The scatter plot compares the true values of tourist arrivals (x-axis) against the predicted values (y-axis), with the dashed line representing perfect predictions (where true values equaled predicted values). The close alignment of data points along the dashed line indicates the model’s high accuracy and effectiveness in forecasting tourism demand.

Figure 8.

(a) True vs. predicted values for the TCA + XGBoost model on the Taiwan dataset. (b) True vs. forecasted values over the testing period for the Taiwan dataset.

Figure 8b displays the comparison between the actual number of tourists arriving in Taiwan (blue line) and the forecasted values (orange dashed line) by the TCA + XGBoost model over the testing period. The x-axis represents the date, while the y-axis shows the number of tourists arriving in Taiwan. The close alignment between the true and forecasted values demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately predict tourism demand over time.

These figures illustrate the accuracy and reliability of the TCA combined with XGBoost in predicting tourism demand. The Figure 8a demonstrates a high correlation between the predicted and true values, indicating the model’s precision in capturing the underlying patterns of the data. The Figure 8b shows the model’s performance over the testing period, with the forecasted values closely aligning with the actual number of tourists arriving in Taiwan. These visualizations confirm that the TCA + XGBoost model effectively generalizes and accurately forecasts future visitor numbers, proving its utility for strategic planning in the tourism sector.

4.5. Comparison Result

This section comprehensively evaluates the proposed TCA and ensemble learning method against various benchmarks. This section presents a detailed comparison with non-ensemble algorithms and traditional feature selection techniques, highlighting the advantages of the proposed approach. Additionally, it presents a computation time analysis of ensemble learning after applying different feature selection methods, demonstrating the efficiency of the proposed method. Furthermore, this section compares the performance of the proposed method with existing tourism forecasting algorithms, underscoring its effectiveness in predicting tourism. Lastly, a comparison with other autoencoder-based feature selection algorithms is provided, showcasing the superior performance and resilience of the TCA in enhancing forecasting accuracy.

4.5.1. Comparison with Non-Ensemble and Feature Selection Algorithm

Table 2 compares the MAPE, R2, MAE, and MSE across different machine learning algorithms and feature selection techniques for the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets. The table is divided into two main sections: non-ensemble algorithms and ensemble algorithms, showcasing the performance of linear regression, SVR, XGBoost, LightGBM, and an ensemble DNN under various feature selection methods.

Table 2.

Metrics for various machine learning algorithms and feature selection methods on Taiwan and Hawaii datasets.

For the non-ensemble algorithms, linear regression and SVR, the results indicate that both algorithms generally performed poorly compared to ensemble methods. Linear regression showed a high MAPE across most feature selection methods, with significant errors observed for both datasets. SVR, in particular, exhibited exceptionally high MAPE values, especially for the Taiwan dataset without any feature selection. The R2 values for these algorithms were relatively low, further indicating their limited effectiveness.

Among the ensemble algorithms, XGBoost, LightGBM, and the ensemble DNN revealed markedly better performance. XGBoost demonstrated the lowest MAPE values with the GA and the proposed TCA on the Taiwan dataset, achieving 3.97% and 3.39%, respectively. Similarly, LightGBM and the ensemble DNN exhibited improved performance with the proposed TCA method, indicating their effectiveness in reducing prediction errors. For instance, LightGBM achieved a MAPE of 4.01% on the Taiwan dataset with TCA, while the ensemble DNN achieved 3.82%. These models also displayed higher R2 values, signifying better predictive accuracy and model fit.

The table also highlights the variability in performance across different feature selection methods. For instance, PCA and ICA generally resulted in higher MAPE values for ensemble algorithms, suggesting that these traditional dimension reduction techniques may not be as effective in this context. In contrast, the proposed TCA consistently provided lower MAPE values across both datasets and all ensemble algorithms, demonstrating its reliability and superiority. This was further supported by lower MAE and MSE values, which indicated fewer prediction errors and better overall model performance.

Additionally, the table includes results for NMF and autoencoder-based feature selection (AE), which illustrated mixed performance. NMF yielded relatively high MAPE values for the ensemble methods, while AE provided better results, though not as consistently as the proposed TCA. The R2 values for AE were also comparatively lower, indicating less reliable predictive power.

Overall, the table underscores the significant improvements in forecasting accuracy achieved by the proposed TCA, particularly when used with ensemble learning algorithms. These findings highlight the importance of effective feature selection in enhancing the performance of predictive models in tourism demand forecasting.

4.5.2. Computation Time Comparison of Ensemble Learning after Feature Selection Techniques

Table 3 presents the computation time required for various ensemble learning algorithms—XGBoost, LightGBM, and a DNN—when using different feature selection methods. The table compares the performance without any feature selection (N/A), with GA, autoencoder-based feature selection (AE), and the proposed TCA.

Table 3.

Computation time (in seconds) for ensemble learning algorithms with different feature selection methods.

The results indicate that the proposed TCA method consistently provided the shortest computation times across all three algorithms. For XGBoost, the computation time with TCA was 0.2429 s, which was significantly lower than the time of 0.6702 s without any feature selection. Similarly, LightGBM also demonstrated reduced computation times with TCA, clocking in at 0.0410 s compared to 0.0582 s without feature selection. The most substantial reduction in computation time was observed for the DNN, where TCA achieved a time of 20.6280 s, which was significantly lower than the time of 28.073 s without feature selection.

The table demonstrates that GA also improved computation efficiency, particularly for XGBoost and LightGBM, though not as effectively as the TCA. The AE method provided moderate improvements in computation times but still fell short of the efficiency achieved by the TCA.

These findings highlight the efficiency of the proposed TCA in reducing the computational overhead of ensemble learning algorithms. By selecting and reducing the dimensionality of features more effectively, the TCA enhances prediction accuracy and accelerates the training process, making it a valuable method for large-scale and time-sensitive predictive modeling tasks, such as tourism demand forecasting.

4.5.3. Comparison with Tourism Forecasting Algorithms

Table 4 provides a comparative analysis of the MAPE, R2, MAE, and MSE for different forecasting algorithms applied to the Taiwan and Hawaii datasets. The table includes results from several studies, such as those by Xin Li et al. [2], Shilin Xu et al. [3], Xin Li et al. [4], Zhixue Liao et al. [5], and Yunxuan Dong et al. [6], alongside the proposed TCA combined with XGBoost.

Table 4.

Comparison of various forecasting algorithms on Taiwan and Hawaii datasets.

The proposed TCA + XGBoost method significantly outperformed the other algorithms, achieving the lowest MAPE values for both datasets. Specifically, it recorded a MAPE of 3.3947% for the Taiwan dataset and 4.0059% for the Hawaii dataset, demonstrating its superior accuracy in forecasting visitor numbers. Additionally, the proposed method yielded high R2 values of 0.99 for the Taiwan dataset and 0.95 for the Hawaii dataset, indicating excellent predictive accuracy. The MAE and MSE values for the proposed method were also significantly lower, at 17,546.36 and 572,043,855.45 for the Taiwan dataset and 24,622.89 and 1,511,766,621.07 for the Hawaii dataset, respectively, highlighting the model’s reliability and precision.

In contrast, the other algorithms exhibited higher MAPE values, indicating less accurate predictions. For example, Xin Li et al. [2] reported MAPE values of 11.7960% for the Taiwan dataset and 8.2054% for the Hawaii dataset, with corresponding R2 values of 0.59 and 0.62. The MAE and MSE for their method were substantially higher, reflecting poorer performance. In contrast, Shilin Xu et al. [3] reported even higher errors, with MAPE values of 18.7761% and 14.7302%, and relatively low R2 values of 0.42 and 0.05, further emphasizing the limitations of their approach.

The performance of Xin Li et al. [4] and Zhixue Liao et al. [5] varied significantly, with MAPE values ranging from 15.9470% to 56.3386%, indicating substantial room for improvement. Their methods also showed lower R2 values and higher MAE and MSE, underscoring the challenges in achieving accurate forecasts with these approaches.

Yunxuan Dong et al. [6] also reported moderate performance, with MAPE values of 32.5634% for the Taiwan dataset and 13.9422% for the Hawaii dataset, which are higher than those of the proposed method. Their R2 values were also lower, indicating less reliable predictions.

Overall, the table underscores the effectiveness of the proposed TCA + XGBoost method in delivering more accurate forecasts. The proposed approach consistently achieves lower error rates by integrating advanced feature selection with ensemble learning, higher R2 values, and lower MAE and MSE, highlighting its potential as a robust solution for tourism demand forecasting. These results emphasize the importance of incorporating sophisticated feature selection techniques like TCA to enhance the predictive power of machine learning models in real-world applications.

4.5.4. Comparison with Autoencoder for Feature Selection Algorithms

Table 5 compares the MAPE, R2, MAE, and MSE for different feature selection algorithms when used with various ensemble learning models: XGBoost, LightGBM, and a DNN. The table includes results from LSFNet [13], TEA [14], and Yigit et al. [15], alongside the proposed TCA.

Table 5.

Comparison of various autoencoders for feature selection algorithms with ensemble models.

The proposed TCA method consistently achieved the lowest MAPE values across all three ensemble algorithms, demonstrating its superior performance. Specifically, TCA recorded a MAPE of 3.3947% for XGBoost, 4.1990% for LightGBM, and 3.8246% for the DNN. These results highlight the effectiveness of the TCA in enhancing the predictive accuracy of ensemble models. Furthermore, the TCA showed high R2 values (0.99 across all models), indicating excellent predictive accuracy, with significantly lower MAE and MSE values compared to other methods.

TEA [14] also performed well, particularly with LightGBM, where it achieved a MAPE of 5.0711% and an R2 of 0.99. However, its performance for XGBoost and DNN, with MAPE values of 6.2099% and 7.7560%, respectively, was not as strong as the TCA. TEA also showed lower MAE and MSE compared to other methods but was still higher than the TCA.

LSFNet [13] exhibited higher MAPE values across all ensemble models, particularly with LightGBM, where it recorded a MAPE of 20.0276%. This indicates that while LSFNet is useful, it is less effective than the TCA in reducing prediction errors. LSFNet also had higher MAE and MSE values, reflecting its lower accuracy.

Yigit et al. [15] reported mixed performance, with a notable MAPE of 7.7506% for DNN, which was competitive but still higher than the results achieved by the TCA. However, its performance with XGBoost and LightGBM was less impressive, with MAPE values of 14.5297% and 22.5313%, respectively. The corresponding R2, MAE, and MSE values further underscored the variability in its performance.

Overall, the table clearly demonstrates the advantages of the proposed TCA method in improving the accuracy of ensemble learning algorithms. By providing lower MAPE values consistently across different models, along with high R2 and lower MAE and MSE values, the TCA proves to be a more reliable and effective feature selection technique for enhancing tourism demand forecasting. These findings underscore the potential of integrating advanced feature selection methods like the TCA to optimize the performance of machine learning models in various predictive tasks.

4.6. Feature Importance Analysis Using Target-Concatenated Autoencoder

Table 6 provides a detailed list of feature importance scores calculated from the TCA. These scores reflect the significance of each feature in predicting the target variable, which was the number of tourist arrivals.

Table 6.

Feature importance calculated from target-concatenated autoencoder.

The top three features with the highest importance scores were related to hotel occupancy rates: General Tourist Hotel Occupancy Rate (980.2686), Tourist Hotel Occupancy Rate (890.6157), and International Tourist Hotel Occupancy Rate (880.665). These high scores indicate that the occupancy rates of various types of hotels are critical factors in predicting tourism demand, likely because they directly reflect tourism activity and infrastructure utilization.

Following the occupancy rates, the Hualien Port Vessel Number (606.4426) was identified as another significant feature, suggesting that maritime activity at Hualien Port is a strong indicator of tourism trends, possibly due to the port’s role in facilitating tourist access.

Economic indicators also play a crucial role, as evidenced by the U.S. NAS Annual Growth Rate (593.4832) and the Singapore Annual Growth Rate (528.6199). These features likely capture the broader economic conditions that influence international travel decisions.

Other essential features included the number of tourist hotel rooms, average room rates, and midterm population figures. For instance, the International Number of Tourist Hotel Rooms (586.5709) and Tourist Hotels Average Room Rate (549.1753) were crucial, highlighting the significance of accommodation capacity and pricing in tourism forecasting.

Seasonal indicators such as ” Is December” (517.9967), ” Is November” (485.3672), and ” Is January” (485.2595) were also prominent. These variables underscore the seasonal patterns in tourism, with certain months showing higher or lower tourist arrivals.

Additionally, stock indices like the Shenzhen Composite Index (489.9534) and revenue figures (524.0346) were included, suggesting that financial market conditions and business revenues are relevant for predicting tourism demand.

Overall, the table highlights the diverse factors, from hotel occupancy and room numbers to economic growth rates and seasonal indicators, which the TCA identified as significant for forecasting tourist arrivals. This comprehensive approach ensured that the model captured a broad spectrum of influences, leading to more accurate and reliable predictions.

5. Discussion and Future Works

The experimental results presented in this study highlight the effectiveness of the proposed TCA combined with ensemble learning algorithms for forecasting tourist arrivals. A comprehensive comparison of MAPE across various models and feature selection techniques highlights the TCA’s consistent superiority, significantly improving predictive accuracy.

5.1. Performance Comparison

Table 4 and Table 5 demonstrate that the TCA achieves lower MAPE values compared to other forecasting algorithms and feature selection methods. For instance, TCA combined with XGBoost achieved a MAPE of 3.3947% for the Taiwan dataset and 4.0059% for the Hawaii dataset, significantly outperforming other state-of-the-art methods such as those proposed by Xin Li et al. [2], Shilin Xu et al. [3], and Yunxuan Dong et al. [6]. This highlights the TCA’s ability to effectively capture and leverage relevant features for accurate predictions.

5.2. Computational Efficiency

Table 3 illustrates that the TCA enhances computational efficiency, achieving the shortest computation times across XGBoost, LightGBM, and the DNN. This efficiency is crucial for real-world applications demanding quick and accurate forecasts.

5.3. Ablation Study

Figure 5 and Figure 6, which analyze the impact of different encoding dimensions, learning rates, and autoencoder configurations on MAPE, respectively, reinforce the reliability of the TCA. The ensemble DNN, in particular, demonstrated stable performance across various configurations, highlighting the TCA’s resilience to hyperparameter variations. Furthermore, the ablation study on autoencoder configurations (Figure 7) confirmed that the TCA maintained low error rates, even with different architectural setups, further validating its reliability.

5.4. Feature Importance Analysis

The feature importance scores derived from the TCA, as shown in Table 6, underscore the critical role of hotel occupancy rates, maritime activity, economic growth indicators, and seasonal factors in tourism demand prediction. High importance scores for features like General Tourist Hotel Occupancy Rate, Tourist Hotel Occupancy Rate, and International Tourist Hotel Occupancy Rate emphasize the criticality of accommodation availability and utilization for accurate tourism forecasting. Additionally, indicators such as port vessel numbers and economic growth rates from the U.S. and Singapore highlight the influence of infrastructure and macroeconomic conditions on tourist arrivals.

5.5. Future Work

Based on these promising results, future research could explore several avenues to further enhance the proposed method:

- Integration with Real-Time Data: Incorporating real-time data streams and online learning techniques could further improve the responsiveness and accuracy of tourism forecasts. This approach could enable more dynamic and adaptive models.

- Expanded Feature Sets: Exploring additional features, such as social media trends, global travel advisories, and tourist sentiment analysis, could provide deeper insights into the factors influencing tourism demand. Incorporating these features could enhance the model’s predictive capabilities.

- Cross-Region and Cross-Sector Applications: Extending the application of the TCA to other regions and sectors, such as hospitality, retail, and transportation, could validate its versatility and effectiveness in different contexts. This broader application could uncover unique insights and improve forecasting accuracy across various domains.

- Hybrid Models: Combining the TCA with other advanced techniques, such as reinforcement learning and hybrid neural network architectures, could further improve prediction accuracy and reliability. These hybrid approaches could leverage the strengths of different methodologies to optimize forecasting performance.

- Explainability and Transparency: Developing methods to enhance the interpretability of the model’s predictions is valuable for stakeholders. Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values could be integrated to provide clearer insights into feature importance and model decision-making processes. By addressing these areas, future research can continue to refine and extend the capabilities of the TCA and ensemble learning framework, solidifying its role as a powerful tool for tourism demand forecasting and beyond.

6. Conclusions

The accurate prediction of inbound visitor arrivals is crucial for the tourism industry, facilitating effective planning and resource allocation. Enhanced forecasting models empower tourism managers and policymakers to make informed decisions on infrastructure development, marketing strategies, and service provision. The benefits of precise predictions extend beyond immediate economic gains, fostering strategic planning and ensuring long-term sustainability in tourism development. For instance, understanding visitor trends can guide investments in new tourist attractions, improve disaster preparedness and response strategies, and promote the growth of eco-tourism initiatives that prioritize environmental conservation.

The proposed TCA combined with ensemble learning algorithms demonstrated superior performance in forecasting tourism demand. The experimental results highlight the TCA’s ability to achieve a lower MAPE than traditional methods and other advanced algorithms. Moreover, the TCA’s computational efficiency and reliability make it a valuable tool for real-world applications where timely and accurate forecasts are essential.

Future research should focus on integrating real-time data, expanding feature sets, applying the method to different regions and sectors, developing hybrid models, and improving the interpretability of predictions. Pursuing these avenues will allow the TCA and ensemble learning framework to further enhance the accuracy and applicability of tourism demand forecasting, thereby fostering sustainable growth in the tourism industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.-I.C. and C.-Y.T.; methodology, C.-Y.T.; software, Y.-W.C.; validation, C.-Y.T. and Y.-W.C.; formal analysis, C.-Y.T.; investigation, C.-Y.T. and Y.-W.C.; resources, R.-I.C.; data curation, Y.-W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-Y.T. and Y.-W.C.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y.T. and Y.-W.C.; visualization, C.-Y.T. and Y.-W.C.; supervision, R.-I.C.; project administration, R.-I.C.; funding acquisition, R.-I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Council grant number 103-2511-S-845-006-.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nguyen, L.Q.; Fernandes, P.O.; Teixeira, J.P. Analyzing and forecasting tourism demand in Vietnam with artificial neural networks. Forecasting 2021, 4, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, S. Forecasting tourism demand with a novel robust decomposition and ensemble framework. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Jin, C. Forecasting daily tourism demand with multiple factors. Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 103, 103675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Law, R.; Wang, S. Enhancing tourism demand forecasting with a transformer-based framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 107, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Ren, C.; Sun, F.; Tao, Y.; Li, W. EMD-based model with cooperative training mechanism for tourism demand forecasting. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 244, 122930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhou, B.; Yang, G.; Hou, F.; Hu, Z.; Ma, S. A novel model for tourism demand forecasting with spatial–temporal feature enhancement and image-driven method. Neurocomputing 2023, 556, 126663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbiah, S.S.; Chinnappan, J. Opportunities and challenges of feature selection methods for high dimensional data: A review. Ing. Syst. d’Information 2021, 26, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Sun, M.; Lian, J.; Hou, S. Feature dimensionality reduction: A review. Complex Intell. Syst. 2022, 8, 2663–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebari, R.; Abdulazeez, A.; Zeebaree, D.; Zebari, D.; Saeed, J. A comprehensive review of dimensionality reduction techniques for feature selection and feature extraction. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2020, 1, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Xu, D.; Chen, D. Robust distribution-based nonnegative matrix factorizations for dimensionality reduction. Inf. Sci. 2021, 552, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Meng, F.; Sun, T. Material recognition using robotic hand with capacitive tactile sensor array and machine learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G. Feature selection algorithm based on optimized genetic algorithm and the application in high-dimensional data processing. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Huynh, D.Q.; Mansour, M.R. Loss switching fusion with similarity search for video classification. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 974–978. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, D.; van der Schaar, M. Target-embedding autoencoders for supervised representation learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.08345. [Google Scholar]

- Yigit, G.O.; Baransel, C. A novel autoencoder-based feature selection method for drug-target interaction prediction with human-interpretable feature weights. Symmetry 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidebo, H.B. Factors determining international tourist flow to tourism destinations: A systematic review. J. Hosp. Manag. Tour. 2021, 12, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.-L.; McAleer, M. Aggregation, heterogeneous autoregression and volatility of daily international tourist arrivals and exchange rates. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2012, 63, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Gallego, M.; Ledesma-Rodríguez, F.J.; Pérez-Rodríguez, J.V. Exchange rate regimes and tourism. Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.-C.; Lu, L.-J.; Lai, C.-C.; Hu, S.-W.; Wang, V. Devaluation, pass-through and foreign reserves dynamics in a tourism economy. Econ. Model. 2013, 30, 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.; Law, R. Incorporating the rough sets theory into travel demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Qian, Y.; Wang, S. Forecasting chinese cruise tourism demand with big data: An optimized machine learning approach. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo, I.; González-Martínez, M. A nonlinear dynamic model for international tourism demand on the Spanish Mediterranean coasts. Econ. Manag. 2018, 21, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englin, J.; Moeltner, K. The value of snowfall to skiers and boarders. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2004, 29, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Juwaheer, T.D.; Hu, H.-H. The influence of a hotel firm’s quality of service and image and its effect on tourism customer loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]