1. Introduction

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) aims to maintain the integrity of composite structures by performing activities such as monitoring, control, and inspection. SHM methods rely on fundamental knowledge of mechanics, materials, and electronics. They are used to support the preventive maintenance of systems and structures. It is a combined discipline of different areas: sensor technologies, non-destructive testing (NDT), and condition monitoring (CM). NDT techniques and their applications to identify damage in composite structures have gained popularity in several fields, including aviation, astronautics, spacecraft, power plants, buildings, metallurgy, mechanical engineering, and civil engineering [

1,

2]. NDT techniques attempt to find the existence of damage and its classification in the interior or on the surface of the composite structure without making a ‘cut’ or ‘break’. They may be broadly classified based on several parameters, such as the type of composite required to be examined [

3,

4]. NDT techniques, such as acoustic emission, ultrasonics, X-ray imaging, radiography, eddy–current testing, and thermography, are widely used to detect and characterize various types of damage, including matrix cracking, fiber failure, and delamination [

5]. The most effective damage-identification techniques in composite materials are thermography and ultrasonic testing [

4]. The application of nonlinear dynamics and acoustic emission to monitor progressive damage in polymer-based composites was investigated in [

6]. Local damage in sandwich composites has been analyzed using acoustic emission data [

7].

A composite structure can be monitored using either global or local monitoring [

8]. The authors of [

9] presented an overview of SHM strategies for fault detection, including fault taxonomy, operational evaluation using a hierarchical damage identification scheme, sensor prescription, and optimization with data processing. Vibration-based SHM (VBSHM), embedded sensing, lamb wave methods, and acoustic emissions are among the techniques reviewed for their efficiency in damage identification in composites [

10,

11].

More recently, a novel VBSHM technique was introduced in [

12] to identify and estimate geometrical damage properties using a frequency shift coefficient and a damage library [

13]. In addition, the efficiency and sensitivity of the frequency shift coefficient were examined through numerical and experimental testing for various damage cases, based on vibration monitoring [

14]. The authors of [

15] introduced a general assessment of SHM approaches that use structural dynamic parameters. These parameters are used to analyze the health state of structures by combining algorithms and modal analysis techniques. In such methods, accelerometers or piezoelectric sensors are commonly used to capture vibration responses [

16].

The fundamental assumption in vibration-based damage identification is that any defect or stiffness reduction alters the structural dynamic response, allowing defects to be detected and localized [

17,

18]. Most vibration-based approaches operate by comparing the dynamic behavior of a reference (undamaged) structure to that of a damaged one. The authors of [

19] proposed the earliest comprehensive review on vibration-based damage detection, localization, and quantification. The authors of [

8] discussed the evolution of vibration-based techniques over time from classical signal processing to recent techniques based on machine learning. Similarly, the authors of [

20] reviewed advancements in damage identification in composites, emphasizing hybrid and data-driven strategies.

Other notable contributions include piezoelectric wafer active sensors in [

21] to monitor the growth of structural deterioration, such as fatigue cracks and corrosion in aircraft structures, wave-based defect estimation in composite beams [

22], and guided lamb wave tools for assessing and characterizing damage in composite materials [

23]. Collectively, these studies indicate a shift in SHM from traditional vibration analysis toward intelligent, multi-sensor, and computationally aided systems for real-time damage assessment in composite structures.

This paper aims to present a review of several computational methods and the use of machine learning to identify and estimate damage in composite structures. Although previous reviews have considered either computational modeling or machine learning to analyze damages, this paper brings the two fields together in a combined solution to identify composite damage. The paper highlights the overview of different computational techniques, including physics-based methods (signal processing techniques, modal analysis, and finite element model updating) and optimization methods (inverse problems, particle swarm optimization (PSO), topology optimization, genetic algorithms (GAs), time series analysis, and hybrid numerical methods) as well as supervised or unsupervised machine learning, neural networks and deep learning methods for damage identification in composite structures. The review also examines the types of composite structures investigated in the literature, along with the advantages and limitations of each computational approach in assessing damage. The increasing reliance on combined computational and data-driven methods provides a reason to examine their performance and complementary potential. Each technique has a corresponding damage identification level, and their combined potential allows for a comprehensive diagnosis of damage in composite structures. The presented overview is illustrated by offering several steps that specify the conditions for applying these methods to composite structures. Through comparison of different computational methods and machine learning models, this review predicts the advantages, limitations and research opportunities of developing next-generation intelligent SHM system-based damage identification technologies for composite structures.

The paper is organized in five sections:

Section 1 presents a detailed overview of NDT and a background on SHM for the identification of damage in composites. Structural models, degree-of-freedom (DOF) and developments of FE models are illustrated. In addition, data acquisition and sensor characterization for damage identification are presented in this section.

Section 2 presents a detailed overview of computational methods, including physics-based method (FE model updating, signal processing techniques) and optimization-based methods (inverse problem, PSO, topology optimization, GAs, time series analysis, hybrid methods) for damage identification in composites.

Section 3 presents an overview of machine learning techniques (supervised and unsupervised learning techniques) and their application in identifying damage in composite structures. This section also presents a step-by-step procedure for implementing a machine learning algorithm for the application to composite damage identification. In

Section 4, we discuss conceptual mapping, critical comparison and research trends for damage identification in composites between computational methods and machine learning techniques.

Section 5 shows a brief conclusion based on our findings regarding contributions to SHM in terms of their applicability to composites.

This overview was conducted through a systematic search across peer-reviewed research studies referenced in the main databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, Science Direct, MDPI and SpringerLink during the period 2000–2024. Keywords were used to represent all the significant themes of this paper, such as SHM, vibration-based SHM, signal processing, physics-based, optimization, machine learning, and deep learning, restricting the search to research works focusing on composite damage identification.

1.1. Background of Structural Health Monitoring

In engineering, the load-carrying ability of composite or hybrid structures is crucial for distributing loads effectively. Composite health monitoring should be performed regularly at an early stage to avoid machining failures. It helps limiting the impact of fluctuations resulting from internal pressurization, stiffness reduction, or changes in the structure’s dynamic properties [

11]. It is essential to determine the structure’s ability to withstand external forces using preventive measures. This technique is called prognostic health monitoring (PHM) in [

24]. The first challenge for PHM is to identify the structural condition and the ability to support loads. It is possible to prevent this by conducting a systematic assessment and evaluation of the facility before it reaches a critical point. This strategy helps in reducing the influence of damage and aging on the structure during examination.

SHM is one of the subcategories of PHM, used to diagnose the health status of a structure. The primary purpose of SHM is to confirm the ability to identify the location of defects or cracks in a structure that are often difficult to avoid first, but are essential for safety purposes [

25]. The health monitoring of composites dramatically improves safety by identifying damage modes such as cracking of the composite matrix, fiber failure, and delamination, and is required to prevent further structural failures [

26,

27]. By placing sensors within composites such as thin-ply hybrid composites or laminated materials, including Bragg fiber grating sensors, hidden internal damage can be identified [

2,

28]. SHM enables the monitoring of the critical condition of composite structures. It reduces maintenance expenses and minimizes the safety factor specified by aviation standards. Thus, SHM improves safety and efficiency in the aerospace field [

29]. Works focusing on SHM and its application for assessing damaged structures have emerged rapidly in the last two decades. SHM incorporates the following benefits: increased reliability, enhanced safety, lower life-cycle costs, and ease of use. SHM is the simultaneous or cyclic observation of infrastructures to identify damage without having regular inspections.

The authors of [

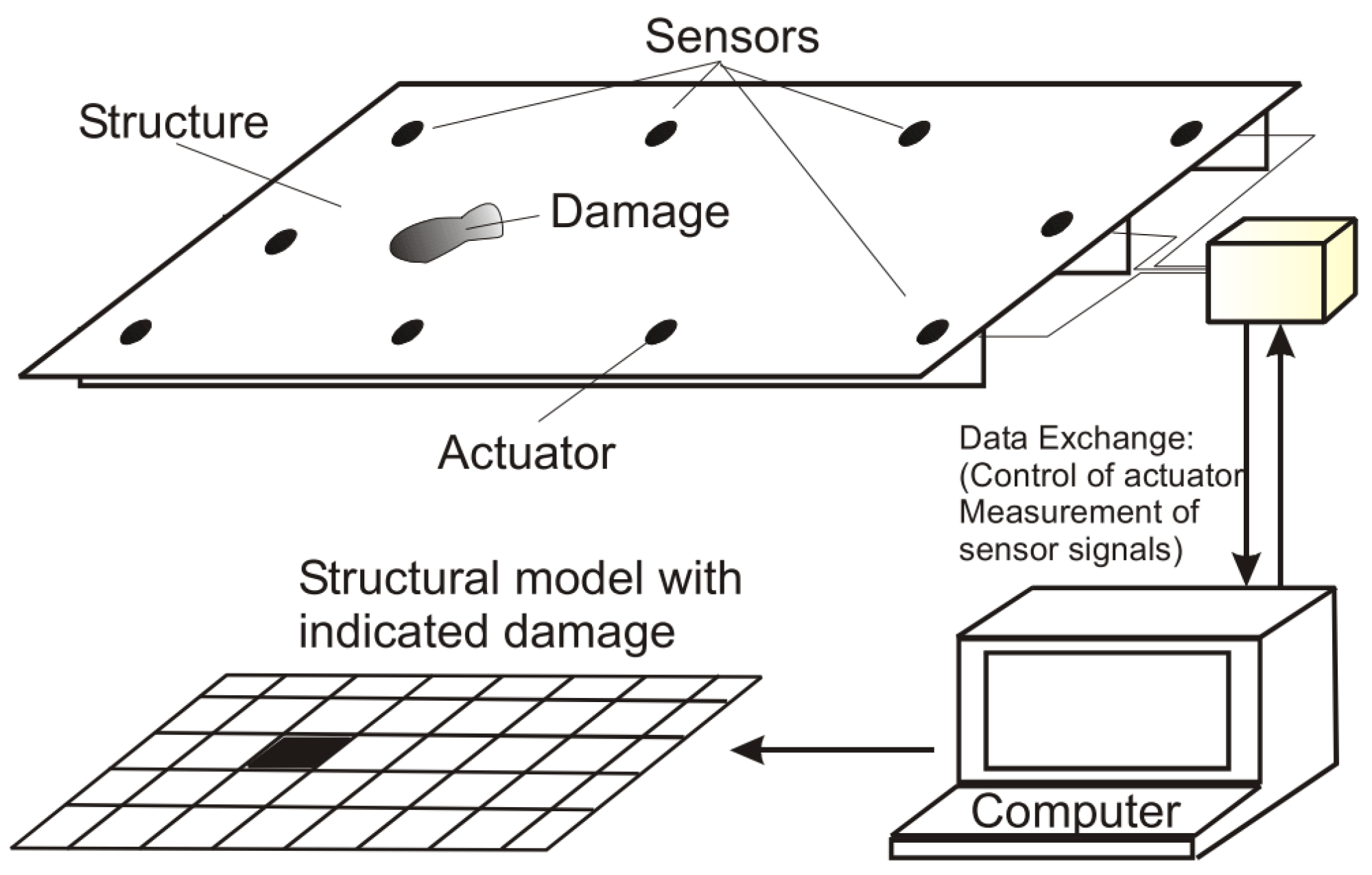

30] presented an overall perspective of an SHM procedure, illustrated in

Figure 1, designed for a structure tested with the integration of a sensor or actuator. The SHM system involves the real-time or periodic assessment of the condition of the composite structure to determine any signs of degradation. Composite structures can be monitored in two ways, globally or locally, depending on their complexity and size. Both global and local methods can be applied, depending on whether machine learning is used with input and output parameters or only with output parameters. Local SHM techniques employ a variety of approaches. They include guided waves, digital image correlation, ultrasonic testing, acoustic emissions, laser testing, and radiography. An example of a global method is VBSHM.

The example presented in

Figure 2 illustrates the use of unknown and reference states for comparison with a dynamic or material parameter to detect damage. SHM monitors the behavior of composite structures through various metrics and damage-sensitive features (dynamic characteristics and time domain coefficients) [

31]. SHM can evaluate the structural integrity of a building by analyzing various measurements and damage-sensitive factors, including vibration parameters and time domain model coefficients [

32]. The authors of [

20] examined the historical development of several damage-identification techniques in the field of composite structures. Other comprehensive reviews [

33,

34,

35] of SHM have discussed notable progress in the area of damage identification. Wave-propagation-based SHM techniques for studying simple harmonic motion utilize a cyber–physical co-design approach based on wireless sensor networks [

36]. The authors of [

37] presented the use of SHM for cyber–physical systems based on wireless sensor networks. The authors of [

38] examined the efficiency of feature selection and its use for learning inspection patterns for SHM. The authors of [

39] addressed the state of the art of guided waves for SHM of aerospace composite structures.

1.2. Vibration-Based Structure Condition Monitoring

Several approaches for detecting, locating, and evaluating the extent of composite structural damage have been reported on in the literature. Vibration methods rely on the structural change, as damage causes a noticeable change in the dynamic behavior of the structure. There is a demand for a fully automatic SHM system based on vibration signals. The authors of [

40] offered an overview of damage detection methods and condition monitoring for bridge structures. The authors of [

41] reviewed damage detection approaches that account for linear and nonlinear variations in vibration measurements. SHM provides five steps for monitoring and maintaining structural integrity (detection, localization and classification, assessment, and prediction). The various stages are depicted in

Figure 3. The authors of [

42] classified damage-identification methods according to the level of damage identification; the aims are described here:

- 1.

Detection: Indication of the presence of structural damage.

- 2.

Localization: Estimation of the damage location.

- 3.

Classification: Determination of the damage type.

- 4.

Quantification: Assessment of the damage extent.

- 5.

Prognosis: Prediction of the remaining service life of the structure.

Vibration-based damage monitoring methods can be broadly categorized based on structural dynamic characteristics. Frequency-based methods (frequency shift analysis, frequency change ratios, frequency sensitivity methods, etc.) exploit variations in natural frequencies due to reduced stiffness. For example, the authors of [

43] used vibration analysis based on frequency shifts from three inverse methods, namely a graphical technique, surrogate-assisted optimization and an artificial neural network (ANN), to forecast the position and size of delamination cracks in a composite beam. Mode-shape-based methods (mode shape curvature, modal strain energy, mode shape derivatives, modal assurance criterion, etc.) exploit variations in mode shapes and mode shape curvatures to localize and quantify damage [

44]. Damping-based methods (log decrements, half-power bandwidth, modal damping ratio, nonlinear damping indicators, etc.) are based on variations in energy dissipation due to either crack opening–closing or frictional effects. VBSHM can assess the changes in natural frequencies and mode shapes. At the same time, it further determines the overall health state of composites [

45].

The authors of [

15] reviewed SHM approaches using dynamic testing-based damage detection and demonstrated the application of SHM techniques in a bridge system. The authors of [

46] described experimental tests based on the evaluation of resistance and tolerance to impact damage, as well as the characterization and quantification of damage, which were carried out to identify damage in composite structures caused by impacts and further investigate the feasibility of using vibration-based methods. The authors of [

47] presented an SHM system to estimate fatigue damage by considering operational vibration measurements in a high-fidelity FE model.

The authors of [

48] investigated statistical methods based on dynamic testing in a small-scale wind turbine blade with accelerometers and further detected low-level induced damage. The authors of [

49] assessed the multi-criteria-based vibration method to detect and locate damage by numerical models of flexural members with varying boundary conditions. The authors of [

50] proposed a hybrid damage detection method that improved both the sensitivity of damage identification and damage quantification. The authors of [

51] applied a damage detection method using structural dynamic parameters. Environmental and operational factors can influence these dynamic responses [

52,

53]. These techniques benefit enormous structures such as wind turbines and spacecrafts, for which identifying damage at the global level is crucial [

54].

1.3. Composite Structures and SHM Challenges

Composite structures present significant challenges for SHM due to their anisotropy, nonlinear behavior, and hidden damage mechanisms such as delamination or microcracks. Moreover, due to the susceptibility of composites to hidden impact damage that cannot be detected through visual inspection, unlike metals [

5].

Several sensing technologies, such as piezoelectric wafer active sensors, fiber optics, strain gauges, and composite electrical property monitoring [

55] have been used for monitoring. Fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensors have been used as a promising tool due to their lightweight properties and multiplexing. Still, these types of sensors face the problem of temperature–strain discrimination during the curing process [

56]. Existing inspection tools have difficulty inspecting large composite regions, and there is a desire to adopt inspection tools such as acousto-ultrasonic technique [

57] and thermography [

58,

59,

60]. There are several SHM techniques available; however, no single method can be applied to all composites and service conditions, and research gaps remain for curved structures and natural fiber composites [

61]. Composites require robust SHM schemes that combine modeling with data-driven schemes. Several challenges must be overcome, including integrating sensors, addressing environmental impacts, property variability, and variability in damage detection.

1.4. Finite Element Method Discretization

In FE models, each DOF represents the specific displacement or rotation at the node within the mesh. The discretization of the structure into an FE model is a process that enables the simulation of the structure’s behavior under different loads. In the context of SHM, the number of DOFs at specific regions of interest enables the detection of defects or structural damage. It is achieved by comparing the predicted real-time data with the measured modal characteristics from the FE model. The equation of motion for a structure can be expressed as follows:

where

is the mass matrix,

is the stiffness matrix,

is the damping matrix,

is the displacement vector,

is the velocity vector,

is the acceleration vector, and

is the external force vector.

The following eigenvalue problem can be solved to acquire frequencies and mode shapes:

where

is the natural frequency and

is the mode shape vector.

An objective function

Q can be defined to minimize changes between measured and predicted data:

where

is the weight assigned to the

i-th measurement,

is the

i-th measurement value,

N is the number of measurements and

is the

i-th predicted value based on the parameters

.

Sensitivity analysis allows to understand how stiffness reduction and changes in parameters affect the structural response:

where

is the sensitivity matrix,

is the response vector and

is the parameter vector.

Furthermore, the numerical reduction in stiffness in composite beams is commonly caused by the occurrence of damage, defects, or degradation of the structure over time. One of the standard methods for modeling this stiffness reduction involves modifying the FE stiffness matrix. Damage in a composite structure can be represented by reducing the elemental stiffness or by changing the elastic modulus.

The stiffness reduction can be expressed as follows:

where

and

are the reduced and real Young’s modulus of elasticity, respectively, and

D is the damage parameter between 0 and 1. A value of

means no damage and

indicates complete damage.

As an alternative to the FE method, the iso-geometric collocation method is very effective in laminated composite beams. It provides two DOFs per node for higher-order shear deformation theory [

62]. The substructuring scheme where the structure is divided into substructures and the DOF-based reduction method were used in [

63]. This study detailed how a complete structure was given in the form of condensed substructures, which were then assembled to reduce computational complexity. The authors of [

64] presented an optimization technique using surrogate models. This technique reduces computational requirements and maintains accuracy in DOF calculations for laminated composite structures.

1.5. Data Acquisition and Sensor Characterization

Various sensors have been used to collect data for the surveillance of composite structures. However, several challenges remain in data acquisition and sensor characterization. Reliable sensing is essential for detecting damage and preventing early-stage catastrophic failures. For example, FBG sensors incorporated into compliant structure samples (very lightweight structures) have demonstrated high sensitivity in the micro-scale bond testing of synthetic and natural filaments, providing measured force resistance output for bonded filament droplet specimens [

65]. Automated data interpretation is highly dependent on the specifics of the sensor setup and the considered composite materials [

66].

Several inspection techniques (ultrasounds, X-ray imaging, and thermography) are critical for providing early insight into damage in composites. By incorporating on-board inspection technologies, these techniques can reduce downtime and enhance safety [

2]. The authors of [

67] presented a comparison of results from fatigue tests with FBG and acoustic emission data, in the form of indicators to monitor damage growth in composite panels.

Table 1 shows the application of different types of sensors, their advantages, limitations, and measurement areas.

The measurement of strain in composite structures is commonly made using strain gauges. The strain () is related to the change in resistance () of the strain gauge: where is the change in resistance, G is the strain gauge factor and R is the initial resistance.

FBG sensors can be placed inside the composite body of the structure, providing data on strain under any applied load. However, temperature variations and vibrations may influence the sensors [

4,

29,

69]. FBG sensors have been used to measure changes in both strain and temperature of a composite structure, as reported in [

70]. The change in wavelength (

) of the reflected light is dependent on the strain (

) and temperature (

):

where

is the change in Bragg wavelength,

is the initial (unstrained) Bragg wavelength,

is the effective photoelastic coefficient,

is the thermal expansion coefficient of the fiber,

is the thermo-optic coefficient (change in refractive index with temperature), and

is the temperature change.

Vibration analysis is another prominent tool for fault diagnosis in composite structures. The authors of [

71] utilized accelerometers that generate signals to identify defects through analysis of the time and frequency domains. The study employed a defect identification method for an automatic press machine used with soft thermoplastic polymers. For example, in several cases, VBSHM and VBSHM-based accelerometers use signals to extract natural frequencies of a structure (

). Changes in these frequencies can indicate defects:

where

k indicates the stiffness of the structure,

indicates the natural frequency, and

m indicates the mass of the structure.

Of all composite sensors, guided-wave-based composite sensors are essential in SHM because they can detect barely visible impact damage in composite structures. These sensors take advantage of guided ultrasonic waves propagating through composites, depending on their anisotropic characteristics of wave speed and energy in the fiber directions [

72]. The wave propagation equation is written as follows:

where

indicates displacement,

A indicates amplitude,

k indicates wave number, and

indicates angular frequency. Damage can lead to changes in wave amplitude, speed, and mode shapes, which the sensors detect and measure through data acquisition.

Likewise, guided-wave-based SHM systems have also implemented machine learning techniques to cope with variations in sensor placement and environmental factors, as demonstrated for high classification accuracy [

73]. Various SHM scenarios have been introduced with machine learning algorithms used in conjunction with sensor networks to enhance the reliability of SHM. For example, a newly developed SHM system based on enhanced convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and FBG sensors has been reported to achieve high potential for early damage identification in composite pipelines [

74]. Machine learning algorithms are used to detect and classify damage [

75]. Ref. [

76] tested real-time damage monitoring from flight-worthy SHM systems installed with sensor networks, showing that they could dramatically lower maintenance and time-off costs for aircraft structures. Ref. [

77] used piezoelectric wafer networks to generate and sense lamb waves in carbon fiber reinforced laminates for the evaluation of delamination.

2. Computational Methods for Damage Identification in Composite Structures

Computational methods have led to multiple improvements over time in the efficiency and dependability of damage detection in various composite structures [

20]. In many cases, conventional inspection and monitoring methods do not meet the growing needs due to the size and complexity of composite structures. So, several computational methods are pivotal in the growing discipline of SHM for identifying and evaluating damages in various composite structures.

2.1. Physics-Based Computational Methods

To identify damage in composite structures, physics-based computational techniques are extensively used. These techniques are incorporated into composite structures, considering material behavior, geometry, and loading conditions, thereby building upon existing predictive models [

78]. The damage mechanisms generally based on FE simulations include the cracking of matrices, delamination, and fracture of fibers. The correlation between measured responses and potential damage states can be achieved by combining model updating [

79] with inverse problem techniques [

80].

Multiscale models provide detailed information on progressive failure, whereas reduced-order models are more efficient in computational operations in real-world scenarios [

78]. Physics-based approaches are frequently constrained by high computational costs and the need for accurate material parameters, as well as challenges in considering environmental and operational variability. To address these difficulties, hybrid models that combine physics modeling with data modeling and high computing are being developed to provide a more effective SHM system for composites.

2.1.1. Signal Processing Techniques

Signal processing techniques are effective for identifying damage in composite structures, especially delamination and impact damage. Time–frequency approaches based on Lamb wave analysis provide a robust damage detection system, as demonstrated in guided-wave-based studies of composite panels [

23]. This technique pursues decomposition algorithms which can be effectively used to achieve good time–frequency resolution while remaining computationally efficient for extracting damage features from complex wave signals [

81].

Signal processing has been continuously employed in physics-based damage identification, as raw signals can be noisy and contain environmental and overlapping modal contributions, requiring separation before numerical or model-based analysis [

82]. Classical approaches such as Fourier analysis, filtering and spectral decomposition are used to extract dominant frequency components associated with structural modes [

83]. Transient or localized features produced by cracks or delamination are typically captured using advanced time–frequency techniques such as wavelet transforms, Hilbert–Huang transforms, and empirical mode decomposition (EMD) [

84,

85]. Piezoelectric-patch-based wavelet-active sensing systems have also been developed. They can produce specific wavelet waveforms and process response signals. This process uses wavelet transforms to detect damage-sensitive features under different environmental conditions [

86].

Signal processing is an essential factor for extracting dynamic features from measured dynamic responses for damage-identification techniques. The Fourier transform is the most popular technique. It transforms the signal in the time domain to its spectral representation for identifying changes in modal frequencies:

where

represents measured vibration signal and

represents frequency content of measured signal. Damage-induced stiffness changes are typically reflected as shifts in these dominant frequency peaks.

For identification of cracks or delamination, time–frequency methods such as the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) are used:

where

represents the mother wavelet,

a represents the scaling parameter, and

b represents the translation parameter. The CWT provides multi-resolution analysis. It is suitable for identifying sudden changes in stiffness or nonlinear dynamic signatures, such as cracks.

Modal identification algorithms including peak-picking, frequency domain decomposition, and stochastic subspace identification are used to estimate natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes under ambient or controlled excitation [

87,

88]. These extracted dynamic features feed numerical models, support the computation of modal strain energy, and provide inputs to optimization methods for localizing and quantifying structural damage.

Overall, signal processing techniques form a critical interface between measured responses and physics-based computational models. They plays an important role in extracting damage-sensitive information from complex structural responses. By considering frequency domain analysis and advanced time–frequency and decomposition methods, these techniques allow the detection of structural changes caused by cracks, delamination, and impact damage. Signal processing in combination with modal analysis and numerical models provides a robust framework for SHM.

2.1.2. Modal Analysis

Modal analysis is among the most common physics-based methods for identifying damage by analyzing changes in a structure’s dynamic characteristics [

19,

89]. Methods such as operational modal analysis (stochastic subspace identification, frequency domain decomposition, etc.) can identify damage in the presence of ambient excitation when the input force is unknown [

87], making them applicable to real-life structures. The authors of [

90] used experimental modal analysis and a laser vibrometer to investigate the structural response of several fiber-reinforced composite components. Recent advancements include time–frequency and wavelet methods [

82] for capturing local transients, as well as data-driven and machine-learning methods that learn damage information from measured vibration responses. The authors of [

91] identified the location and extent of delamination in homogeneous and composite laminates. The authors analyzed the data patterns using modal analysis methods.

Modal analysis is based on the structural dynamics formulation presented in Equation (

1) using the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices. There are modal parameters, namely natural frequencies and mode shapes, which are also derived from the eigenvalue problem in Equation (

2). The modal quantities serve as damage sensitive indicators which reflect stiffness loss in composite structures [

92]. In modal analysis, frequency shifts provide limited spatial resolution. Therefore, mode shapes should be used to enhance sensitivity to local defects. The modal curvature equation is given by the central finite-difference approximation:

where

represents the

i-th mode shape at sensor location

n. Local stiffness reductions typically produce sharp variations in

. This makes modal curvature highly effective for damage localization.

Based on comparison between measured mode shapes with numerical or baseline healthy modes, the modal assurance criterion (MAC) is commonly used to identify defects:

It quantifies the consistency between two mode shapes. MAC values close to 1 indicate similarity, and reductions suggest potential damage or modeling errors.

Modal analysis can serve as an effective tool for global monitoring of composite structures. It provides valuable data on stiffness loss through changes in modal parameters. However, it is sensitive to minor defects and susceptible to environmental and operational variability. Indicators based on modal analysis are best used in combination with FE updating, optimization methods, or hybrid data-driven approaches to enhance damage identification.

2.1.3. Finite Element Model Updating

Damage identification in composite structures, based on the update of FE models, is commonly used to minimize the differences between experimental measurements and numerical estimations [

12,

13,

14]. They are widely used to update model parameters (sometimes stiffness, mass, or damping) to identify the existing condition of the structure [

47,

93]. FE sensitivity-based methods utilize structural response derivatives to solve structural problems based on model parameters, and further combine optimization-based methods to solve problems by minimizing error functions. FE updating is especially useful in composite structures to estimate stiffness degradation due to matrix cracking, delamination, or fiber breaking [

50,

94]. Still, there are challenges related to computational cost, the local minimum problem, and the need for high-quality experimental data. The combination of FE updating and machine learning [

79] and reduced-order models is a new direction that can enhance scalability and reliability in SHM applications. The research by [

94] has been applied to natural fiber reinforced composites (i.e., kenaf fiber-epoxy plates) and to the optimization of both geometrical and material properties by combining experimental modal analysis with FE analysis.

Figure 4 illustrates the workflow of FE model updating used to localize and quantify damage in composite structures using an iterative updating approach based on minimizing the difference between experimental data and numerical calculations.

Based on the FE equation of motion in Equation (

1), the dynamic behavior of a structure can be described. Here, damage is usually represented as a change in stiffness

, with

representing damage parameters. The FE formulation of structural dynamics is, as explained in the previous

Section 1.4, formulated in terms of the eigenvalue formulation, optimization objective function (Q), the sensitivity matrix (S), and material degradation law

. It is based on these foundations that FE model updating can be used to localize and estimate damage in composite structures.

On an element level, the stiffness contribution of an element

e is represented as follows:

where

is the undamaged element stiffness matrix and

is a damage index that quantifies the severity of stiffness reduction (with

for undamaged and

for fully damaged).

The global stiffness matrix of the structure can then be assembled as follows:

where

is the total numbers of FEs and

is the element-wise damage index.

This equation defines correlation between the degradation of materials and global dynamic response. It supports the FE updating process which is not only aligned with the measured and predicted responses but which also localizes and quantifies damage in composite structures. Iterative model updating is a process that uses the minimization of the difference between measured model data and model prediction by varying the parameters .

2.2. Optimization-Based Computational Methods

Optimization-based techniques have emerged as a powerful tool for identifying damage in composite structures. Optimization techniques [

95] can be used to solve multi-engineering structural problems, as well as for the critical requirement of SHM. Several studies in the literature have identified composite damages using optimization methods. These identifications can be performed to minimize the difference between experimentally tested and predicted responses, as shown in

Figure 2, and hence indicate the presence of delamination, matrix cracking, or fiber breakage. Damage identification optimization is often framed as minimizing the objective function using an inverse problem approach [

96,

97]. Here, the damage parameters are defined as design variables and the objective functions are defined by dynamic or steady-state structural responses.

Several optimization techniques have been introduced, such as some smooth optimization, GAs [

98] in the global search for multimodal or complex problems, PSO [

99,

100] in global search, and inverse problem methods [

101], where the damage state is estimated based on measured responses. In addition, topology optimization [

102] has been developed for composite monitoring, including damage detection and sensor placement. Forecasting the optimal locations of sensors or structural damage diagnostics by linking stiffness loss to structural topology changes has become a valuable tool in identifying changes due to structural damage.

Optimization techniques are performed using multiple response parameters, such as natural frequencies, mode shapes, modal flexibility matrices, and static displacements, to identify and estimate damage. The goals of achieving the best detection accuracy and the lowest computational cost [

103] were successfully resolved using multi-objective optimization methods [

104]. It has also been necessary to utilize advanced optimization techniques to address the numerous complex damage problems [

105].

2.2.1. Inverse Problem in Optimization Algorithm

The application of the inverse problem is based on the fact that damages inside composite structures can be identified from their dynamic responses. Inverse problems are solved using various optimization techniques, including PSO [

99], sunflower optimization [

106], the marine predators algorithm [

80], the time reversal approach [

96], and ultrasonic SHM methods [

107]. These techniques are used to determine unknown loads, identify delamination in carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer composites, and reconstruct the impact force exerted on the composite part. Modal response, modal strain energy change ratio, and structural transfer functions based on sensor data are used to quantify, measure, and monitor defects in composite structures. The authors of [

106] investigated optimization algorithms for detecting damage in large-scale truss-type structures. The authors of [

108] mentioned a method based on the inverse FE method (iFEM) for SHM and damage detection. They were focused on detecting internal/external defects in composite materials using iFEM. The study showcases iFEM’s remarkable accuracy in evaluating the presence, extent, and morphology of damage, making it a promising technology for shape sensing and damage assessment in laminated composites. The application of inverse problems in different SHM-based optimization techniques used for damage identification is listed in

Table 2.

The authors of [

96] are concerned with the need for SHM techniques for carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer plates. Their method utilizes modal responses by solving an inverse problem. The first observation is that the proposed approach is evident in detecting delamination, which can save time and money in aircraft maintenance by providing a more localized definition of the problem area. The authors of [

109] described a numerical technique using an inverse homogenization approach for the problem of minimizing compliance subject to point-wise stress constraints. This was used to manage stress intensity at the local level due to the microstructure with multiscale quantities.

Table 2.

Application of inverse problem in different computational damage-identification techniques and their advantages, disadvantages, and limitations.

Table 2.

Application of inverse problem in different computational damage-identification techniques and their advantages, disadvantages, and limitations.

| Technique | Advantage | Disadvantage | Limitation | Ref. |

|---|

| Differential evolution (DE) enhanced with radial basis functions | Improved search performance, accurate damage detection | High computational cost, sensitive parameter tuning | Requires complex integration, depends on initial problem formulation | [110] |

| Bayesian inference | Provides probabilistic solutions, robust predictions, data-driven model | Computationally expensive | Requires prior distribution knowledge | [111] |

| Inverse problems with hybrid algorithms | Combines strengths of multiple techniques | Complex implementation | Balancing different methods can be challenging | [101] |

| Robust optimization techniques | Provides solutions under uncertainty, | Computationally intensive | Solutions may be conservative | [95] |

| Stochastic methods | Handles uncertainties and randomness effectively | Requires extensive computational resources | May lead to approximate solutions | [112] |

The equation of the inverse problem to determine the location and severity of damage from the measured data (vibration, stress and strain) in composite SHM is written as follows:

where

is the vector of measured responses,

is the vector representing the internal state of the structure (e.g., damage parameters),

is the forward model that maps the internal state to the measured responses, and

is the vector of measurement errors or noise. The inverse problem aims to estimate

given

. It is written as follows:

The inverse problem may not have a unique solution. The solution may be independent of the data. Regularization techniques can be essential and valuable, leading to a regularized form of the inverse problem:

where

is a data fidelity term,

is a regularization term, which imposes prior information or constraints on the solution, and

is a regularization parameter that balances the data fidelity and regularization terms.

Several computational methods have been proposed for the inverse problem, incorporating optimization steps. The authors of [

113] presented an inverse problem using a recurrent neural network (RNN) to predict crack location and depth in graphene fiber-reinforced polymer cantilever beams by minimizing the error between the actual and predicted natural frequencies using FE analysis data. Another method is the time-reversal method [

106], which may present a solution where dynamic output data are used to identify the location of the damage. Some methods, such as reduced-order models and sparse proper generalized decomposition, have also been employed to solve the inverse problem of determining fiber and matrix failure in 3D woven composite plates.

Lamb waves in an FE analysis environment (NDT method) have been used to detect and estimate the location of damage in composite plates [

114]. Some metaheuristic optimization algorithms such as self-adaptive quasi-oppositional stochastic fractal search and sunflower optimization have been successfully implemented to solve inverse problems by using modal data and optimizing the objective functions [

115,

116,

117].

Several techniques, particularly those involving the application of inverse problems, typically help improve the health monitoring of composites. The inverse problem offers an efficient, accurate, and noninvasive technique for identifying damage in composites, although it requires regularization methods to obtain fixed points and best-fit solutions.

2.2.2. Particle Swarm Optimization

PSO is used as a tool for optimization issues, particularly in the identification of damage. It has most applications in SHM-based damage identification. PSO is used to locate damage by modeling the structure’s responses (dynamic and static) using FEM [

118,

119]. The PSO algorithm was employed to find damage in composite structures using remote sensing FBG sensors, thereby further improving the computational time required to identify damage in real-time [

120]. Several reviews have demonstrated that PSO is effective in identifying damage and assessing composite structures. The authors of [

100,

121] tested the PSO to detect delamination in laminated beams and composite laminated plates with high precision. The authors of [

122] extended the application of PSO to estimate the frequency changes of the members in a damaged structural system. The authors of [

123] employed the PSO algorithm to optimize sensor placement, thereby increasing the reliability of damage assessment in ultrasonic-based SHM systems. In [

124], real-time computation was achieved through the implementation of PSO with FBG sensors involved in damage localization to reduce computation time.

Applications of different PSO techniques for identifying damage in composite structures (tested structures, advantages, and limitations) are listed in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The authors of [

125] introduced a new approach using PSO–support vector regression to successfully manage self-healing FBG sensor networks. The approach was installed in an aircraft wing box to increase system reliability and reduce cost. The authors of [

126] adopted a 3D structure, improving reliability and robustness based on the wireless sensor network and advanced PSO. The authors of [

121] found that combining PSO with the simplex method had a higher detection accuracy for delamination in composites and had the potential to be used in real time. PSO integrated with ANNs was employed in [

127] for estimating damages in laminated plates, and it was found promising in terms of model accuracy and efficiency. The authors of [

128] provided a systematic review focused on the PSO variants used in SHM and their positive impacts, and discussed possible further research avenues. In the paper by [

105], the authors reported an improvement in an algorithm using PSO and GAs to identify damage in aerospace composites. The authors of [

129] introduced a hybrid PSO technique for identifying structural damage in steel beams.

Several works have been collated here, demonstrating the effectiveness of PSO-based algorithms. The authors of [

130] compared various metaheuristic algorithms and illustrated that, among the algorithms, the PSO had the performance most suitable for detecting structural damage. In addition, Ref. [

131] highlighted the characterization of damage based on guided ultrasonic waves and achieved a higher level of precision in identifying the position of the damage using PSO. Midspan de-bonding was detected in RC beams in [

132] based on the impedance-based method using piezoelectric sensors and PSO optimization. A spectral element model and adaptive mesh scheme enhance detection accuracy in the early stage through experimental validation.

Table 3.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of PSO-based algorithms for damage identification in different types of tested composite structures (first half).

Table 3.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of PSO-based algorithms for damage identification in different types of tested composite structures (first half).

| Algorithms | Structure Tested | Advantages | Limitation | Ref. |

|---|

| mPSO and RNN | Composite cantilever beam. | Detects multiple transverse cracks | RNN locates cracks, mPSO refines crack parameters | [133] |

| PSO and ANN | Composite plates | PSO optimizes frequency, ANN predicts dynamics and delamination | Clamped boundaries, FE simplifications affecting delamination accuracy | [134] |

| Mixed unified PSO (MUPSO) | Composite beams and plates | Detects and quantifies delamination using vibration responses. | Assuming linear delamination may misrepresent vibration responses amid noise. | [135] |

| Quantum behaved PSO (QPSO) | Laminated composite components | Failure criteria, QPSO optimizes composite design for weight, cost, strength across loading | In-plane loading only, ignores other real-world constraints | [136] |

Table 4.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of PSO-based algorithms for damage identification in different types of tested composite structures (second half).

Table 4.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of PSO-based algorithms for damage identification in different types of tested composite structures (second half).

| Algorithms | Structure Tested | Advantages | Limitation | Ref. |

|---|

| Kappa coefficient + PSO + FAN (Fuzzy ARTMAP Network) | Composite plate | Achieves over 75% hit rate and 20% improvement in damage identification | Depends on FAN setup, may struggle across SHM scenarios. | [137] |

| PSO and DTW (Dynamic Time Wrapping) | Composite truss structure with aluminum connectors | Identifies damage, minimizes modeling error, improves damage detection | Relies on accurate FE models, computationally intensive, sensitive. | [118] |

| Impedance-based de-bonding detection and PSO optimization | Composite beams strengthened with fiber-reinforced polymer strips | Detects early midspan de-bonding in beams accurately | Sensitive to environment; requires precise spectral element modeling | [132] |

The PSO algorithm considers each particle,

i, in the swarm as a potential solution and possesses the following characteristics: position—

; velocity—

; personal best position—

. In addition, the fitness function

can be used to evaluate the quality of each particle’s position. This function measures the possibility of damage at a given position,

. The

is written as follows:

The velocity of each particle undergoes an update using the following standard equation:

where

w indicates the weight of inertia,

and

indicate the acceleration coefficients,

and

indicate the random numbers distributed uniformly in

, and

indicates the best global position found by the swarm. The position of each particle is updated using the following equation:

Figure 5 shows a flowchart of the PSO-based damage localization method [

138]. It shows several levels to implement the PSO method for damage localization. All particles have initial positions

and velocities

, which are randomly assigned at the start of the structural simulation. Subsequently, the fitness function

of the particles can be computed. Then, the best personal position of each particle, denoted

, is adjusted by its fitness assessment. From the personal best position of all particles, the global best position

can be determined. Afterwards, the velocity and position of each particle can be updated using the respective PSO update equation. This series of evaluations, updating velocities, and updating positions can be achieved iteratively until a stopping criterion is reached.

SHM systems have incorporated several optimization techniques to ensure the identification of damage. The authors of [

131] suggested that the intelligent colony optimization imaging technique can transform ultrasonic-guided wave damage imaging into a scattering source search problem by the application of PSO for detecting cracks and delamination in composites. The authors of [

139] used quantum PSO to identify damage in laminated composite structures. The author showed that the model could reach high accuracy and convergence even with fewer sensors and noisy measurements.

The use of PSO with artificial intelligence approaches has been proven effective in solving challenging SHM problems. These tools have emerged as the most preferred approach. PSO-based optimization algorithms have played a crucial role in enhancing SHM systems. These advanced techniques have enhanced damage identification, computational efficiency, and system robustness.

2.2.3. Topology Optimization

Topology optimization is a mathematical tool that optimizes material properties within a given design space, subject to a set of boundary conditions, loads, and constraints, to identify damage in composite materials. Several studies have shown the application of the topology optimization method for damage identification. The authors of [

102,

140] are concerned with utilizing topology optimization to identify damage in structural systems and composite laminates, respectively.

Table 5 presents various reviews based on the techniques of topology optimization (type of algorithm used, structure tested, its benefits, and limitations) to detect damage in composite structures. In several cases, topology optimization can be used to identify damage in composite structures by locating regions where material properties have been lost.

The equilibrium equation for a composite structure (linear elastic) is written as follows:

where

indicates the global stiffness matrix,

indicates displacement vector, and

indicates force vector.

In minimization problems, the objective function for topology optimization is typically defined to minimize the compliance of the structure.

where

C indicates compliance and

indicates the vector of design variables that represent the density distribution in the structure.

The material properties of each element are given using a density variable

:

where

indicates Young’s modulus of the element

e,

indicates Young’s modulus of the base material, and

p indicates the penalization factor.

The sensitivity of the objective function to the design variable

is given by:

where

indicates the elemental stiffness matrix.

Figure 6 represents the flowchart of the damage identification strategy using topology optimization as introduced by [

141]. The author implemented ultrasonic wave propagation and the FE model to update the damage parameters to identify damage. The optimization problem of the topology was defined using the square error minimization problem between the estimated ultrasonic characteristic

and the target data

at node

i. The equation is given as follows:

where the damage varies within the range of

for j

and

m and

n are the total number of elements and nodes, respectively. Here, a slight reduction in stiffness is assigned to damaged elements.

Table 5.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of topology-optimization-based algorithms for damage identification in different tested composite structures.

Table 5.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of topology-optimization-based algorithms for damage identification in different tested composite structures.

| Algorithm | Structure Tested | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|

| Statistical topology optimization | 1-D and 2-D beam structures | Clustering, local optima for single and multiple damage identification | Minor damages identification, local optima issues | [142] |

| Topology optimization and lasso regularization | Cantilever plate | Identified damage using noisy frequency response functions | Sensitivity to noise and ill-posed inverse problem | [143] |

| Topology optimization using MSC.Nastran | Composite laminate cantilever beam | Damage localization through numerical and experimental validation | Requires high-quality vibration tests | [144] |

| Topology optimization | Composite plates | Sensitivity to delamination, optimized sensor placement | Complexity in sensor placement, varying damage scenarios | [140] |

| Solid shell-element-based topology optimization | Large composite structures | Enhanced defect tolerance and explicit topology tracking | Complexity in managing large models and computation | [145] |

In addition, gradient-based methods, such as the method of moving asymptotes, are used to solve [

146] the optimization problem:

where

is the material volume and

is the maximum allowable volume.

The authors of [

147] applied topology optimization, where the sensitivity to damage can be further maximized by comparing the healthy and the damaged responses from macroscopic to microscopic scales. Topology optimization in SHM depends on numerical methods and sensors to enhance the ability to identify the position of the damage in composite structures.

The authors of [

141] presented a damage-identification approach based on topology optimization combined with visualization of the propagation of ultrasonic waves, which is capable of providing the actual state of the damage with high precision by searching the optimum distribution of the damage parameters in an FE model. Hence, this method demonstrates the feasibility of applying topology optimization to predict damage in composite materials. Topology-optimization techniques have been previously employed in [

148] to enhance the fracture properties of particle–matrix composites by identifying optimal unit cell topologies that maximize fracture energy under specific boundary conditions, thereby improving the fracture toughness of the investigated structures.

Furthermore, topology optimization based on multiple materials, combined with adjoint sensitivity analysis, can enable the use of various plasticity and hardening models and predict how these models affect the topology and potential damage of composite structures [

149]. The rational approximation of material properties concept within topology optimization has also been shown to reduce peak stresses in adhesive overlap joints, which are areas of concern for potential damage in composite structures [

150].

These works highlight the role of topology optimization in understanding failure in composite structures and further improving and defining the optimized SHM system. Topology optimization provides an efficient tool for identifying damage by updating the stiffness distribution to match observed structural responses. Being computationally intensive, it provides high spatial resolution and serves as an effective tool when used in combination with FE analysis or data-driven SHM methods.

2.2.4. Genetic Algorithms

GAs have been used as a significant tool for identifying damage in composite structures. Several studies suggest that GAs can be employed as an optimization-based method for damage identification in composite structures. The authors of [

151] suggested an interval wavelet multi-population GA to locate and quantify the damage in cantilever structures through numerical simulation. FE updating with GA has been applied to the damage detection of laminated composite plates [

50]. Performance comparison of GA and PSO with traditional signal processing techniques has been established to detect single and multiple damage scenarios in composite beams [

152]. The authors of [

153] presented a multi-objective GA with a fuzzy logic data fusion method, which enhances convergence speed and precision for the identification of large-scale structural damage. The authors of [

154] used GA for the identification of damage in 3D frame structures based on FE modal analysis with high precision to determine the location and size of single and multiple damage. Several GA-based damage-identification methods and their applications, in terms of the composite structure tested, along with their advantages and limitations, are listed in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

The primary objective of the GA is to minimize an objective function that defines the error between the measured and predicted response of the damaged structure. The objective function

for the identification of damage can be written as follows:

where

represents the measured response (e.g., displacement, strain),

represents the predicted response of the model, and

n represents the number of data points.

In GAs, potential solutions or chromosomes need to be encoded. A typical representation might be a binary string or a vector of real values that represents damage to particular locations in the composite structure. For example:

where

m represents the number of locations that are considered for damage and

represents the level of damage at location

j.

Fitness

can be evaluated for each member of the population. The equation of fitness follows:

where a low value of the objective function indicates a higher fitness score.

Furthermore, selection promotes as a process that shows the selection of better performing individuals in the population. In this case, one may use the selection of the tournament as an example, where

individuals are randomly chosen. The best among them can be selected:

Crossover combines parts of two parent solutions to create offspring. For real-valued representation, a single-point crossover can be defined as

where

represents the probability of crossover,

r represents a random number.

Mutations introduce variability into the population by randomly altering genes. For example:

where

is the mutated damage level and

is a random number drawn from a normal distribution.

Finally, the standard termination criteria are based on a predefined maximum number of generations and a tolerance on the fitness level.

GAs are used to minimize the changes between the analytical and measured vibration data. They offer more advantages than conventional gradient optimization techniques [

161]. It is possible to identify the location of the damage and its extent by comparing the changes in frequency and mode shape [

44]. Microgenetic algorithms have been used for incomplete and noisy modal test data [

162]. In addition, genetic fuzzy systems have been introduced to identify matrix cracks in thin-walled composite beams using a combination of fuzzy logic for uncertainty representation and GA learning ability. GAs show a reliable identification of damage in the presence of noise [

163]. Damage identification has been investigated [

164], using GAs based on bivariate Gaussian functions for micromechanical damage identification, where degradation of stiffness due to fiber damage was considered in laminated composite plates. The authors of [

165] proposed a proper orthogonal decomposition method with a radial basis function for crack identification in carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer composites; the authors used genetic and Cuckoo search algorithms. The adopted approach can accurately estimate the size of the crack and maintain stability with low noise levels. The authors of [

97] suggested a method based on a multi-objective GA, ANN, and fuzzy decision making. These works show that GAs can be used for damage localization and quantification in various composite structures.

2.3. Time Series Analysis

Time series analysis is a statistical data tool that considers variations over time, and can be used, for example, for sensor readings in SHM [

166]. Time series analysis has emerged as an essential method of SHM in structures, especially in aerospace industries, where the complexity of materials is critical. The time series approach utilizes temporal data collected from various sensors to identify, locate, and quantify the extent of damage. The authors of [

167] developed a method that utilizes a sparse piezoelectric sensor network and a two-step methodology to localize impact events and estimate the impact energy on aircraft structures. The authors of [

168] presented a time series analysis for damage detection that analyzes acceleration with time histories to identify damage in mechanical systems. It requires data pre-processing to identify a reference undamaged signal, followed by two-stage auto-regressive models with an exogenous variable input model. Higher residual error values between the forecast and actual signals show the damage and help locate the cause near precise sensors. The integration of time series analysis with the seasonal auto-regressive integrated moving average model [

169] has been shown beneficial for simulating the behavior of bridge structures. The authors of [

170] highlighted the role of vibration-based inspection techniques in SHM in predicting deviations in model coefficients or residual error values for damage detection. Time-series-based damage-identification methods and their applications are listed in

Table 8 according to the type of tested composite structure, along with their advantages and limitations. The use of time series analysis in SHM for composite structures not only improves the precision of damage identification, but also promotes the industrialization and accreditation of intelligent structures, which plays an important role in the development of sectors utilizing composite materials [

4,

167,

171,

172].

A basic representation of a time series

at a given time

t is decomposed into its components: trend term (

), seasonal fluctuation term (

) and random error term (

). This decomposition is usually captured by an additive model defined by

. Some of the most popular time series models are the auto-regressive integrated moving average models. The general form for such model can be written as follows:

where

B indicates the back-shift operator,

indicates the time series,

indicate parameters of the auto-regressive model,

indicate parameters of the moving average model,

d indicates the degree of differencing, and

is the random error term. SHM can enhance the interpretation of sensor data by leveraging the features of the such model, enabling it to detect and assess potential anomalies in structural health perception.

The above scheme in

Figure 7 illustrates a two-phase statistical time series method (i.e., a baseline and inspection phase) [

173]. This involves using statistical decision techniques to analyze acquired data, modeled as time series, and identify operating conditions that comprise healthy and different forms of damaged states. By comparing the characteristic quantities derived from structural data in the inspection phase, damage can be identified, and more importantly, specific types of damage can be distinguished. Among other techniques, time series analysis substantially contributes to the health monitoring of composite structures by analyzing vibration responses and other dynamic data to detect and predict damage [

170]. Previously, raw high-dimensional time series sensory signals had several complications. The application of time series analysis is more beneficial in SHM for composite structures. These structures are predominantly required in the aerospace, automotive, and civil engineering fields due to their properties such as high stiffness and low density [

11].

Time series analysis offers a complex and efficient methodology for diagnosing various composite structures. Hence, implementing sophisticated statistical models, artificial intelligence systems, and real-time data to promote structural and safe operations in numerous distinct engineering domains [

11,

168,

170,

174].

Adaptive auto-regressive integrated moving average models incorporate adaptability to better respond to changes in the data over time. In these models, parameters such as auto-regressive moving coefficients (

) and moving average moving coefficients (

) are used and developed over time to fit the pattern of change in the data stream. This self-adaptation is especially useful in areas like SHM, where the behavior of the target structures constantly evolves with such aspects as age, environmental conditions, and operational use. The general form of these adaptive models is:

where

and

indicate the adaptation parameters that can be time-dependent

t. Due to the abilities of such parameters, these adaptive models can be considered useful for the analysis of time series, particularly in SHM, where data change over time.

Ref. [

175] proposed a damage identification scheme that utilizes electromechanical impedance and auto-regressive models with piezoelectric sensors. The authors of [

176] applied a vector-based approach using seasonal auto-regressive integrated moving average models with adaptive Kalman filtering for time series analysis, utilizing strain data. Several studies have demonstrated that time series analysis, machine learning, and data fusion can be used simultaneously in SHM to improve the identification of damage and life prediction for composite structures [

166,

177].

Time series analysis allows the extraction of damage-sensitive features from vibration, acoustic emission, and guided-wave signals under different temperature and operational conditions. It assists in early anomaly detection and in developing robust, data-driven SHM models by characterizing temporal and spectral trends. Its performance requires proper preprocessing to reduce noise effects and environmental impact.

Table 8.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of time series analysis based algorithm for damage identification in composite structures.

Table 8.

Applications, advantages, and limitations of time series analysis based algorithm for damage identification in composite structures.

| Algorithm | Structure Tested | Advantages | Limitations | Ref. |

|---|

| Recurrence and entropy methods with time series measurement | Glass-fiber-reinforced polymer composites during milling | Detects subtle signal changes, accurate, sensitive damage detection | Sensitive to noise, computationally intensive, complex analysis required | [178] |

| Auto-regressive moving average models with statistical process control | Lightweight structures with piezoceramic patches | Accurate damage detection, time series analysis, nondestructive | Complex model calibration, sensitivity to noise, limited generalizability | [179] |

| Gaussian mixture model with auto-regressive moving-average processes and Mahalanobis distance | Benchmark Structure | Accurate damage detection, extent assessment, robust data fusion framework | Sensitive to model assumptions, complex feature extraction, computationally intensive | [180] |

| Auto-regressive models with singular value decomposition | Composite coupons | Effective damage detection, no mode extraction, robust, automated | Computational complexity, sensitive to noise, requires sensor alignment | [181] |

| Auto-regressive time domain identification | Composite rotor blades of helicopters | Accurate modal parameter identification, damage localization, validated experimentally | Sensitive to signal noise, requires extensive experimental setup | [182] |

2.4. Hybrid-Based Computational Methods

Recent advances in hybrid methods have significantly improved damage identification in composites. The delamination in composite structures was investigated in the work of [

121], where a hybrid algorithm was proposed by combining the PSO with the simplex method. This hierarchical approach effectively illustrated improved accuracy in the identification of delamination and showed the efficiency of this method in damage identification in laminated composite structures. The authors of [

127] developed an approach in which PSO integrates with an ANN to evaluate the extent of damage in laminated composite plates. In their work, they employed iso-geometric analysis and the Cornwell indicator, highlighting the benefits of using various computational methods and to achieve excellent mathematical precision while reducing computational time. Metaheuristic optimization has been discussed in several areas in the last few years. The authors of [

130] reviewed advances in metaheuristic optimization techniques for SHM, where the authors covered PSO, imperialist competitive algorithm and ant colony optimization. They noted that, despite several algorithms, PSO is computationally efficient in global optimization; however, it often requires assistance with local optimization in complex search spaces.

Figure 8 from [

121] presents an example of a hybrid optimization algorithm that combines PSO and the simplex method for delamination detection in laminated beams. It used modal frequencies to optimize delamination variables. The algorithm finds a hierarchical and cooperative regime of global search and local search from the objective function to find the delamination.

Other population-based optimization techniques, including artificial immune systems and firefly algorithms, were also considered for SHM applications. The authors of [

183] proposed a PSO and butterfly optimization algorithm with an ANN for progressive identification of structural damage and reported better accuracy compared to other methods when applied to aluminum beams. Intelligent hybrid methods can be used for neural networks, time series data, and fuzzy inference systems [

184]. The combined hybrid systems can compute the health indices of the compound structure, giving a decision level necessary for future risk assessment [

185]. Different procedures for employing distributed sensor networks and dynamic mechanical models enable accurate real-time impact force estimations on a time series basis, without the need for widespread training or precise structural diagrams [

174]. Several hybrid-based damage-identification methods, along with their applications in terms of the type of composite structure tested, advantages, and limitations, are listed in

Table 9.

The fundamental stages of hybrid computational methods include the following:

Step 1: The cost function can be represented by . The objective is to either minimize or maximize this function.

Step 2: The design constraints can be represented by , and include structural constraints.

Step 3: The fitness function, , gives a measure of the quality of a best-fit solution x by the general goals of health monitoring, including the location of the defect or the quality of the collected data.

Step 4: In cases with conflicting objectives, for instance, cost versus reliability function, multi-objective optimization is introduced to find Pareto optimal solutions subject to , where .

Step 5: The decision variables can be denoted by x, and they refer to the designated locations and types of sensors to be implemented, as well as other operating parameters subject to the optimization algorithm.

Step 6: Hybrid optimization methods are used to find the optimal decision variables. They include evolutionary algorithms and the application of gradient techniques, or predictive modeling through machine learning algorithms.

These steps highlight the increased importance and efficiency of integrating the analytical and numerical applications of hybrid optimization techniques to improve the accuracy and credibility of composite SHM systems.

5. Conclusions

Computational methods and machine learning have been improved and revolutionized for SHM and the identification of damage in composite structures. When integrating these techniques, a significant leap has been demonstrated over existing damage-identification methods in composites in terms of accuracy, practicality, and robustness. Applying inverse problem, PSO, topology optimization, hybrid optimization, and time series analysis, in combination with machine learning, has opened new possibilities for data-driven damage identification and composite monitoring. These computational methods, which combine physics-based approaches with optimization algorithms, can be employed to assess data collection, damage detection and estimation, sensor placement, and the system’s overall performance.

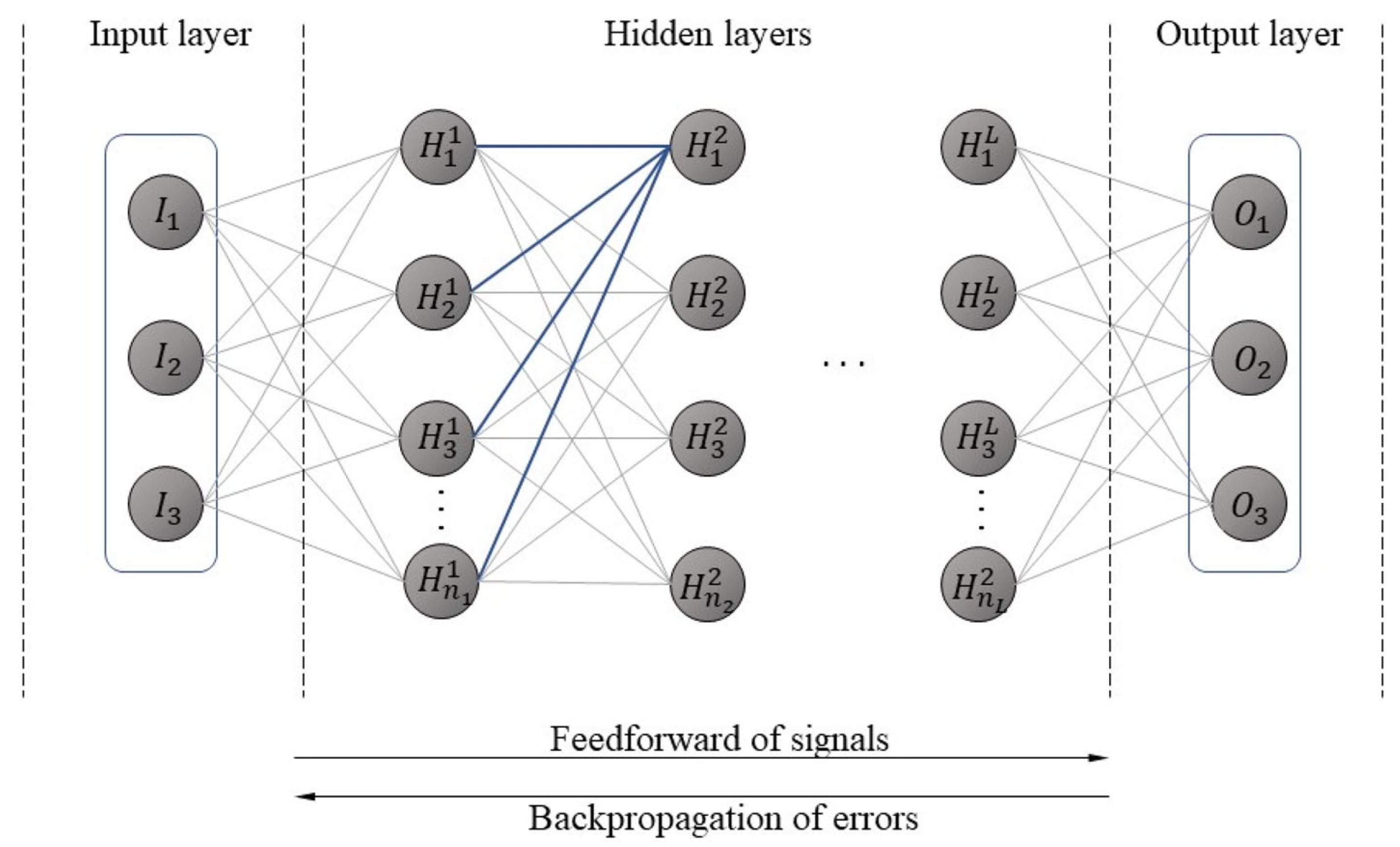

Physics-based methods (signal processing techniques, modal analysis, and finite element model updating) and various optimization-based techniques have long served as the foundation (as conventional methods) for analyzing damage in composite responses under different environmental and loading conditions. Recent advances in integrating machine learning (supervised learning and unsupervised learning) and neural networks have further enhanced real-time damage detection, predictive maintenance, and early failure prevention of composites. In several cases, ANNs and anomaly detection algorithms are used to process large sensor data sets and detect subtle variations in structural behavior, as well as predict possible failures at an early stage.

Based on this overview, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- 1.

A range of computational methods, including physics-based methods and optimization algorithms (inverse problem, PSO, topology optimization, GAs, hybrid optimization, and time series analysis), provide accurate, physics-based information on damage response. These techniques can vary depending on the type of optimization algorithm and the complexity of the considered composite materials. These algorithms can be both instrumental and limited, depending on the type of structure.

- 2.

Machine learning with neural networks, including anomaly detection techniques, has revolutionized composite surveillance by making it possible to predict the early onset of damage, deploy predictive maintenance strategies, and improve safety through real-time monitoring.

- 3.