Compression Molding of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites for Shape Memory Polymer Actuation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Manufacturing of TPU Composite

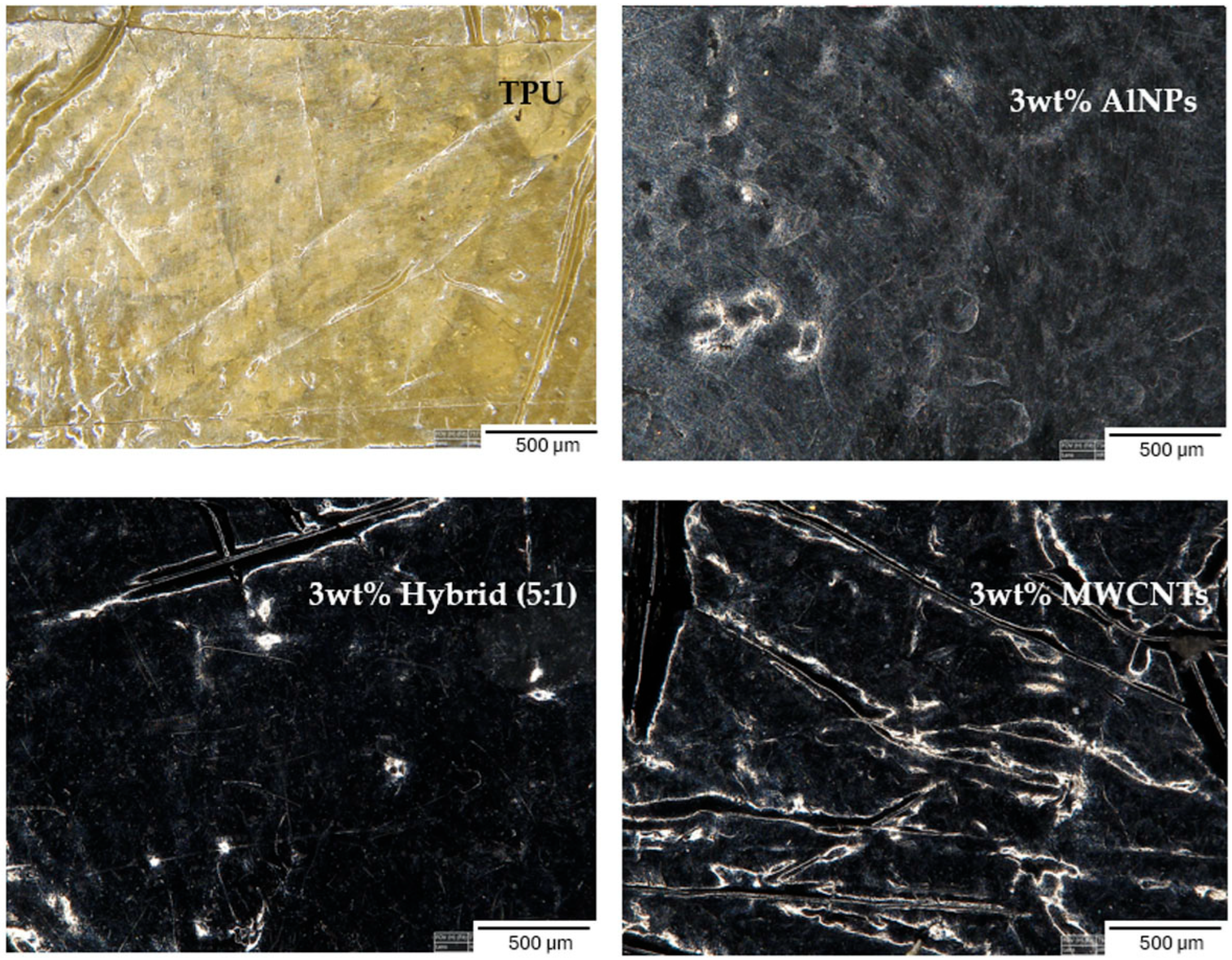

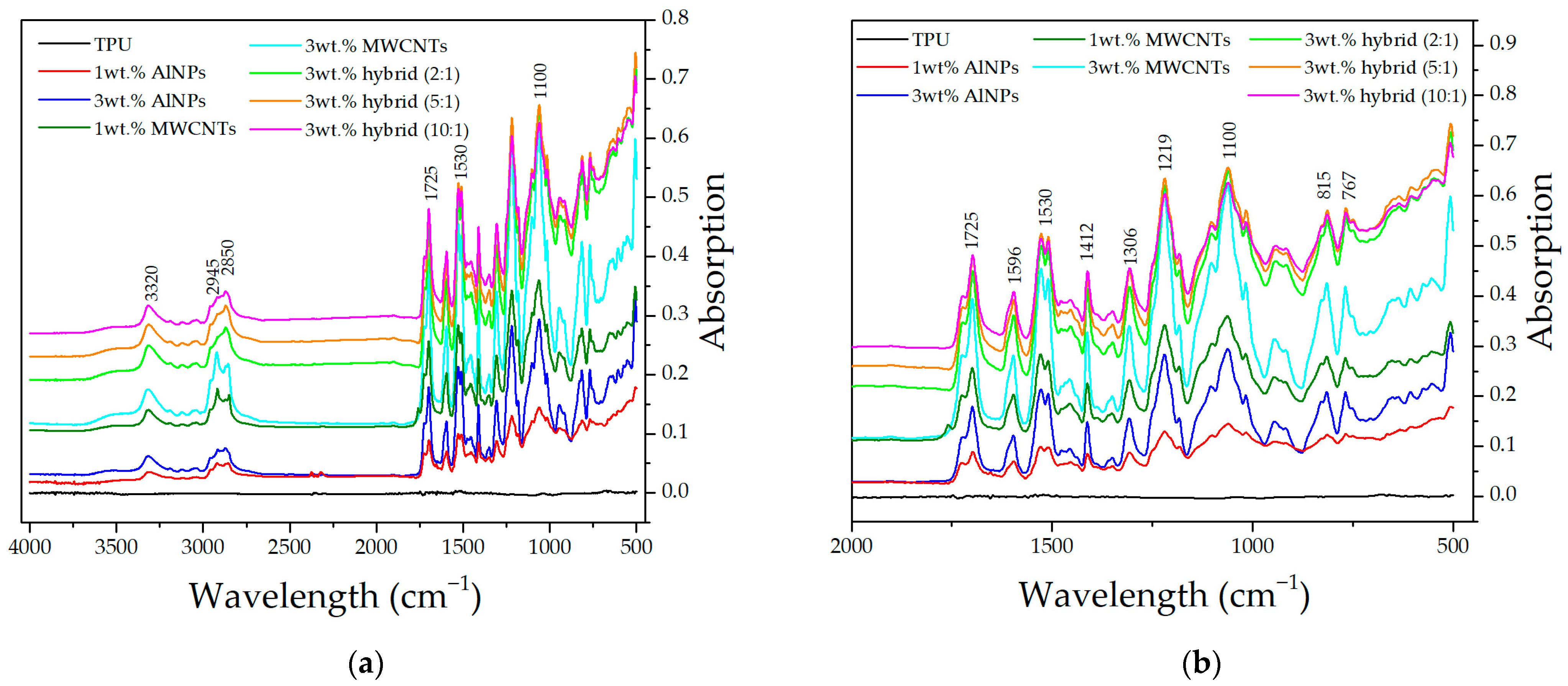

2.2.2. Microscopic and Spectroscopic Analysis

2.2.3. Thermal Properties Testing

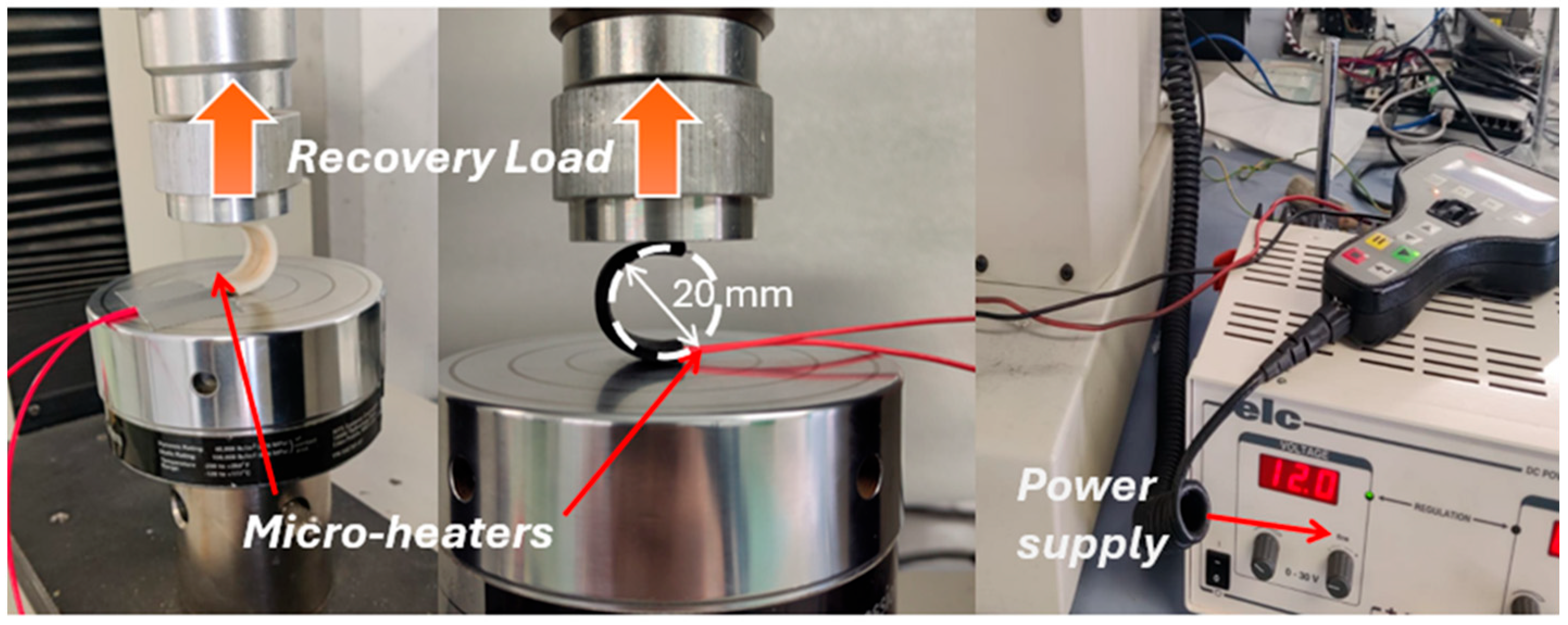

2.2.4. Mechanical and Thermo-Mechanical Recovery Tests

2.2.5. Electrical and Thermal Conductivity Testing

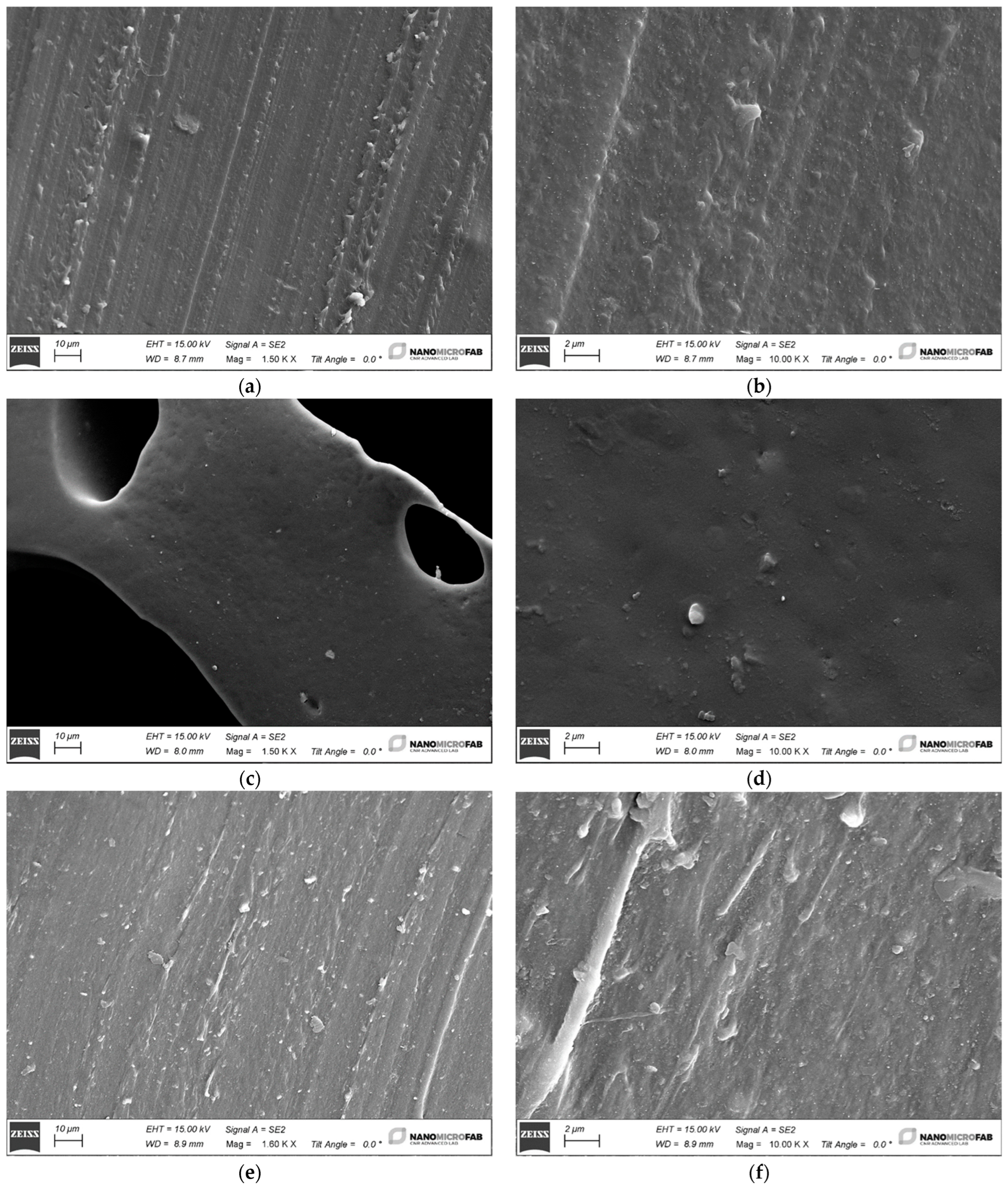

2.2.6. Surface Spectroscopy and Morphology

3. Results

3.1. Superficial Observations and Spectroscopic Analysis

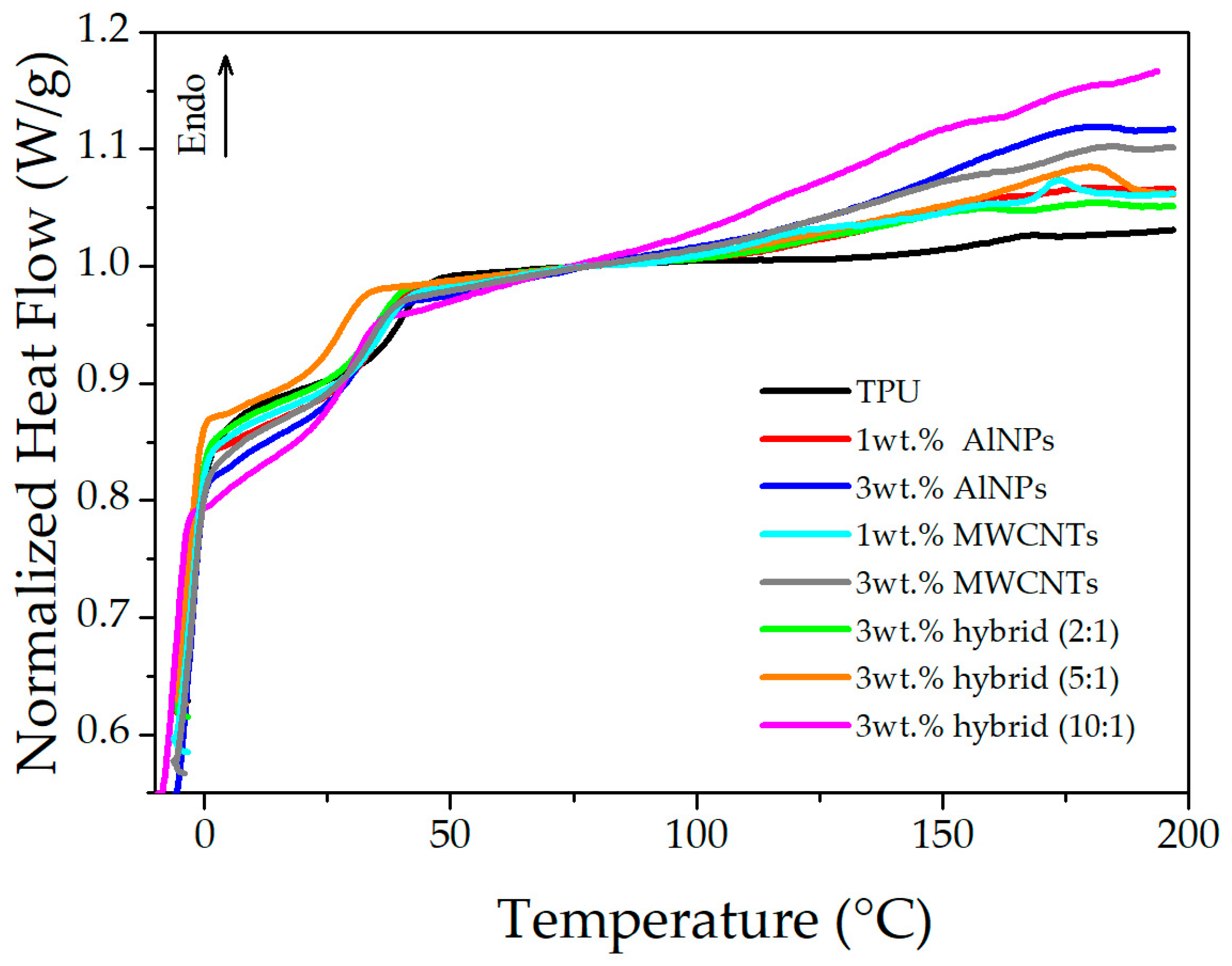

3.2. Thermal Properties Evaluation

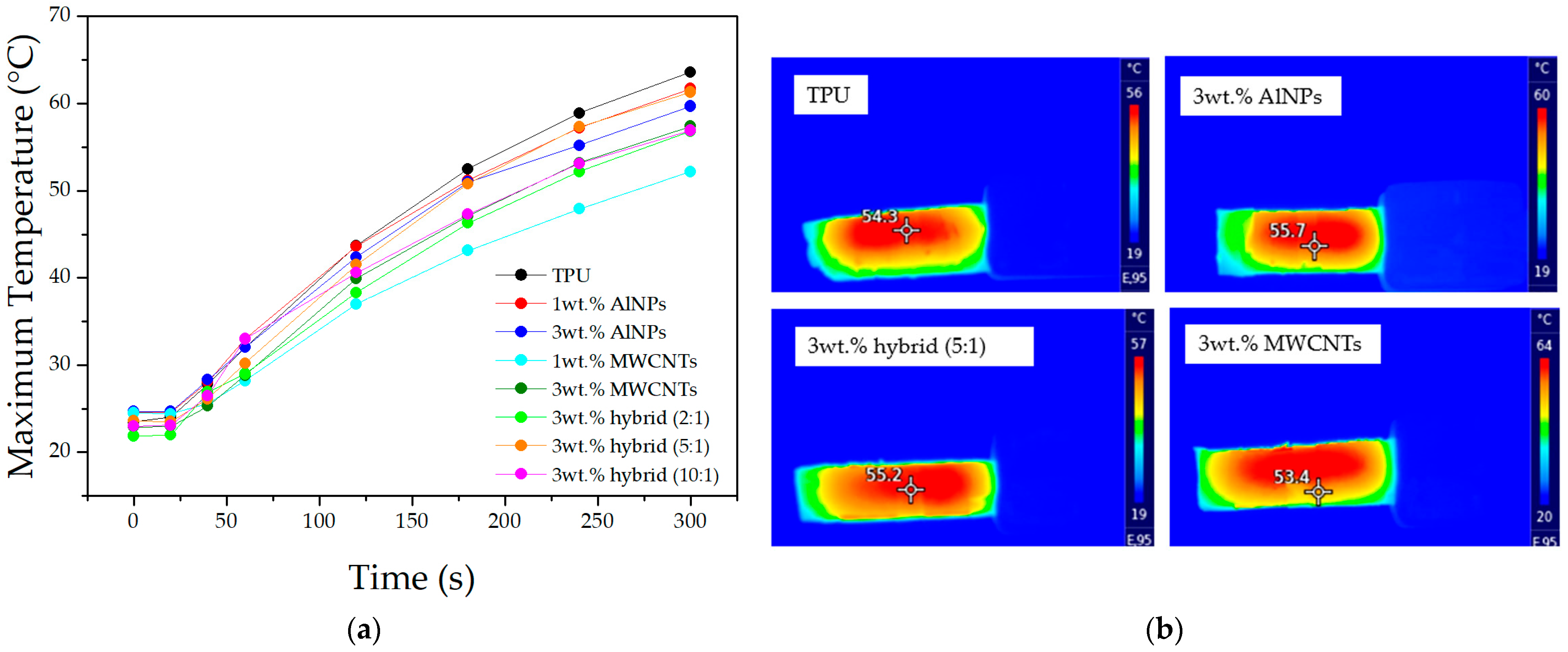

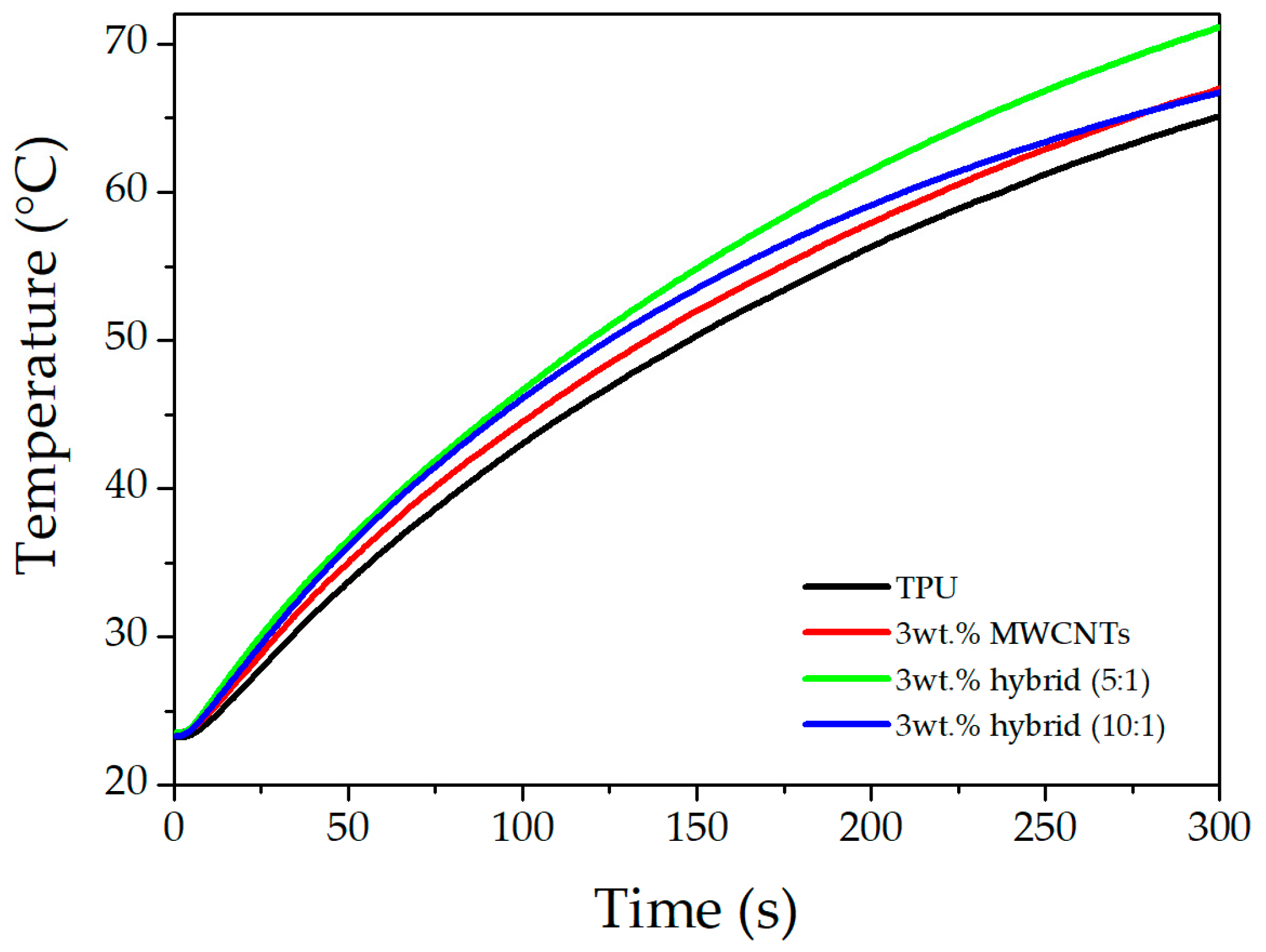

3.3. Surface Temperature Monitoring

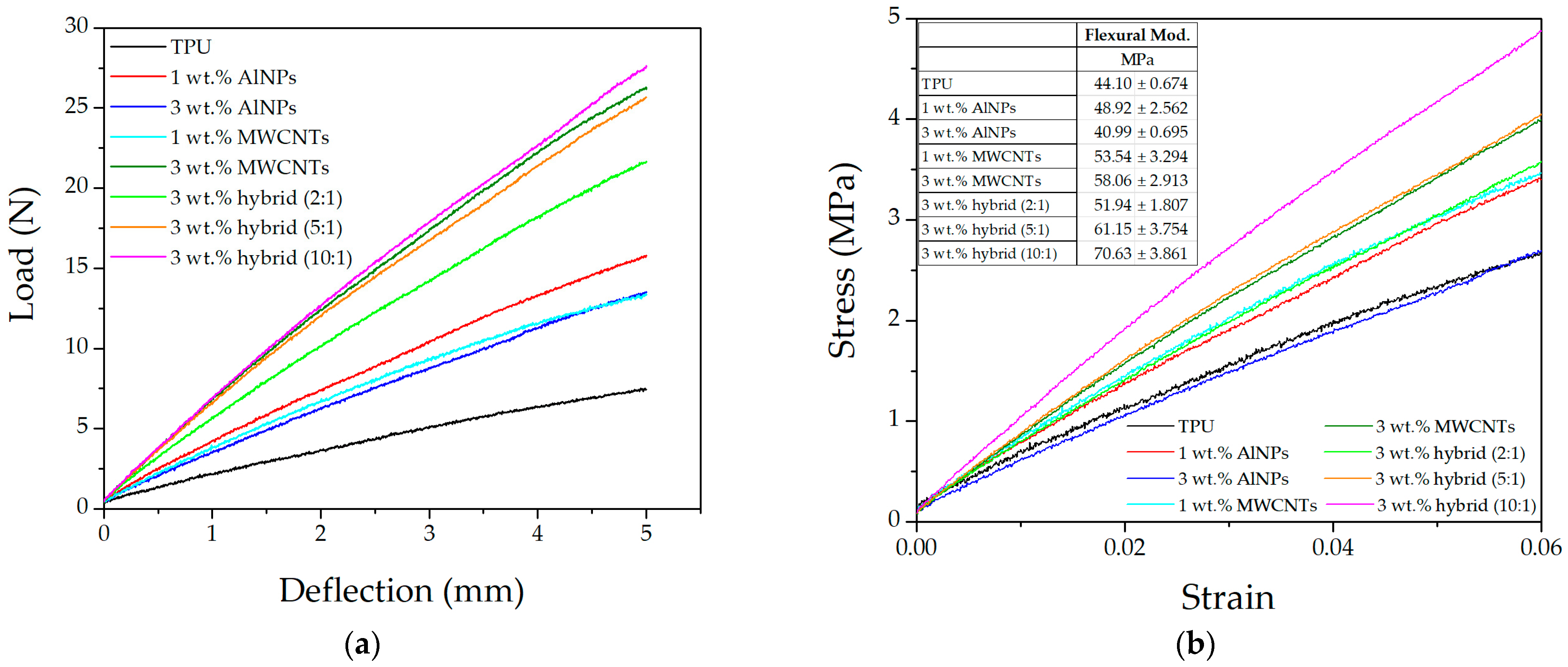

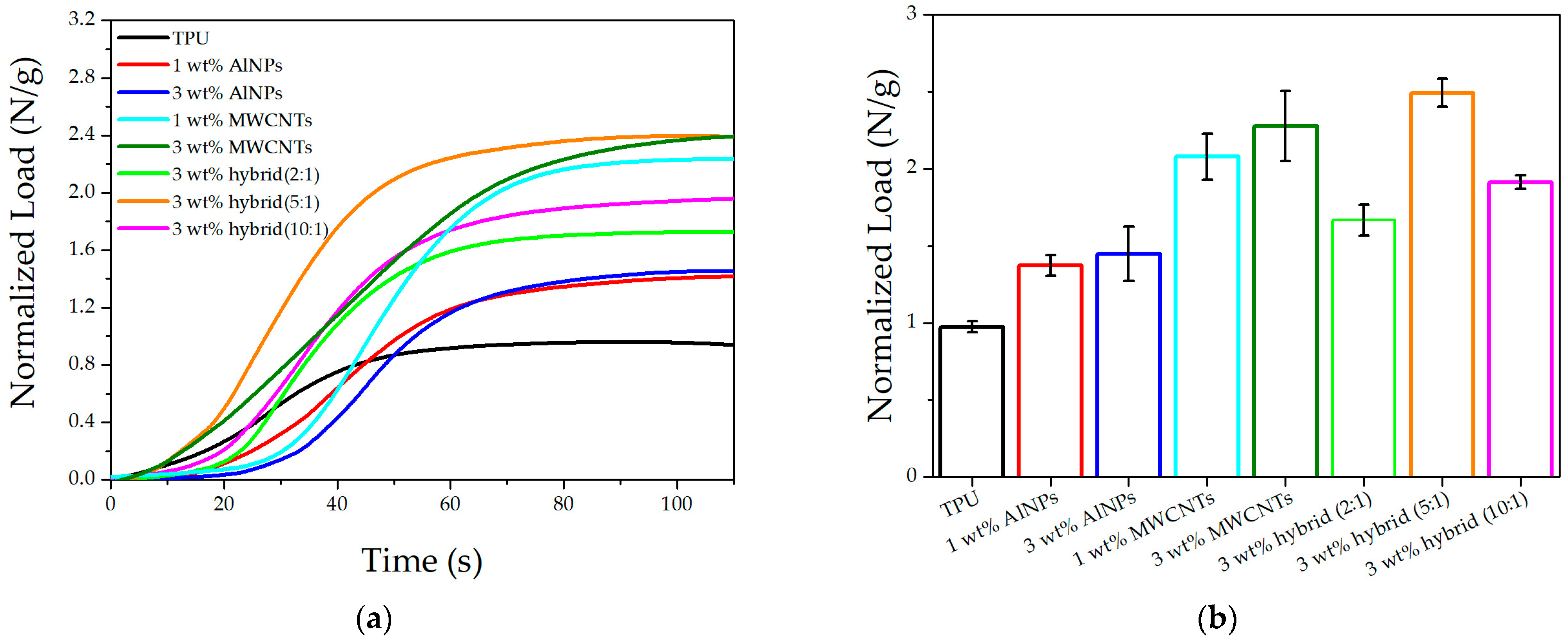

3.4. Mechanical Evaluation and Thermo-Mechanical Recovery

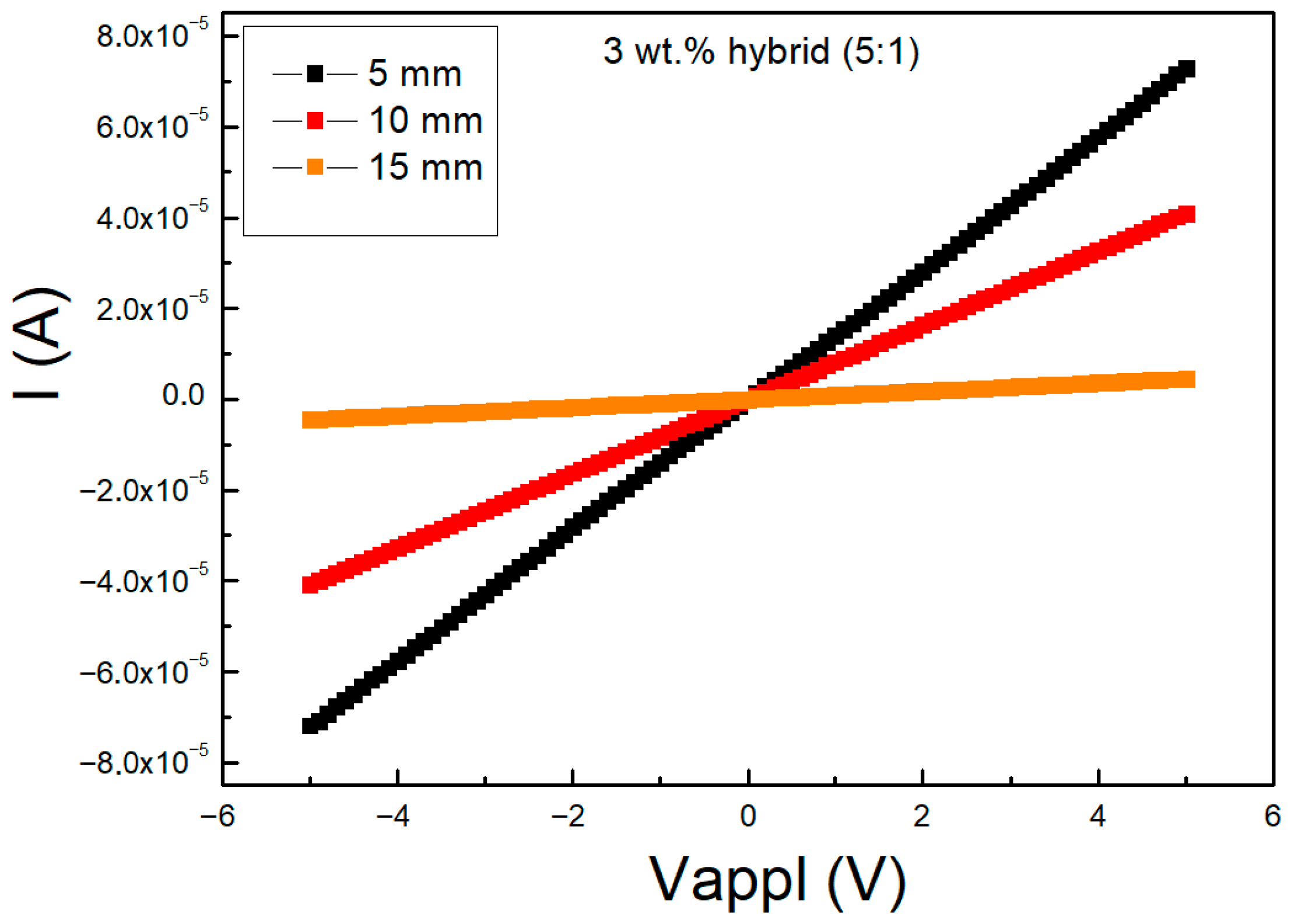

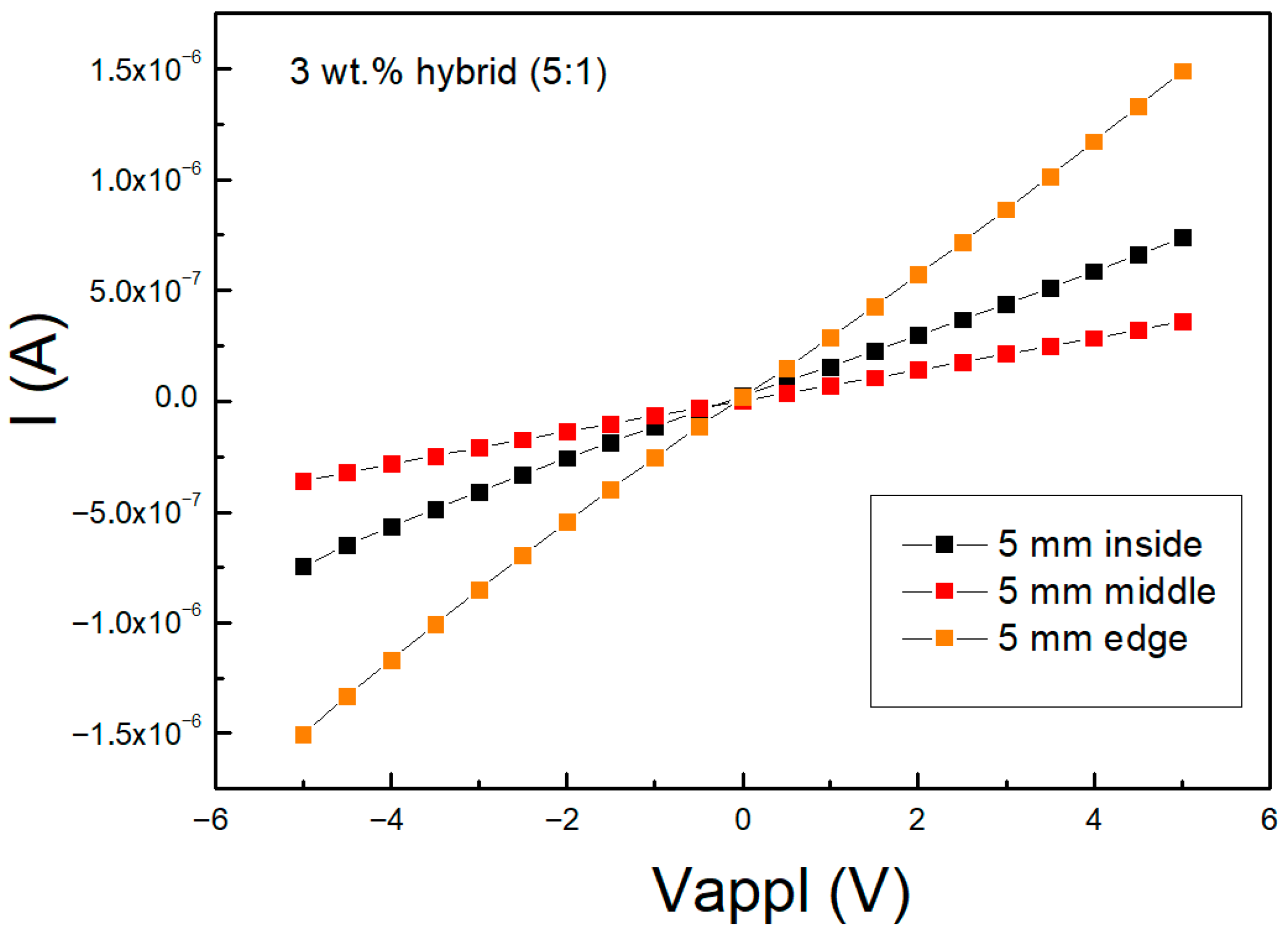

3.5. Electrical and Thermal Conductivity

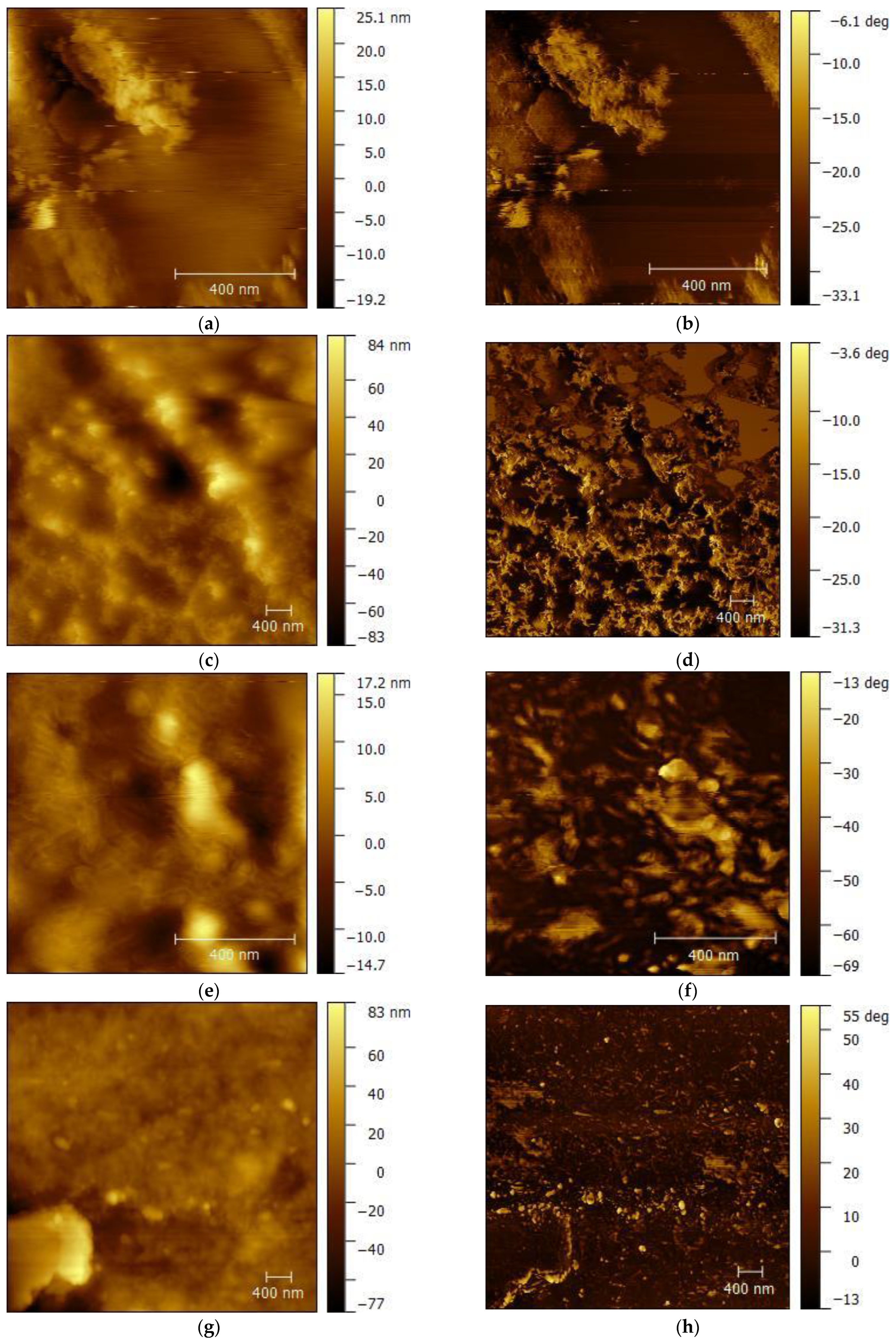

3.6. Morphological Observations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hassan, M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Wang, T.; Dhakal, H.N.; Misra, M. Current status and future outlook of 4D printing of polymers and composites-A prospective. Compos. C Open Access 2025, 17, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zende, R.; Ghase, V.; Jamdar, V. A review on shape memory polymers. Polym. Technol. Mater. 2023, 62, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y. Shape memory effect of thermoplastic segmented polyurethanes with self-complementary quadruple hydrogen bonding in soft segments. Eur. Phys. J. E 2009, 28, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, F.; Li, J.; Weng, Y.; Ren, J. Synthesis of PLA-based thermoplastic elastomer and study on preparation and properties of PLA-based shape memory polymers. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 015315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, M.R.; McKinzey, K.G.; Roth, A.A.; Grunlan, M.A. PCL-Based Shape Memory Polymer Semi-IPNs: The Role of Miscibility in Tuning the Degradation Rate. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 2493–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, P.; Banerjee, S.S. Construction of stimuli-responsive and mechanically-adaptive thermoplastic elastomeric materials. Polymer 2022, 259, 125338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.-Y.; Jing, X.; Napiwocki, B.N.; Hagerty, B.S.; Chen, G.; Turng, L.-S. Biocompatible, degradable thermoplastic polyurethane based on polycaprolactone-block-polytetrahydrofuran-block-polycaprolactone copolymers for soft tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 4137–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nakib, R.; Toncheva, A.; Fontaine, V.; Vanheuverzwijn, J.; Raquez, J.; Meyer, F. Thermoplastic polyurethanes for biomedical application: A synthetic, mechanical, antibacterial, and cytotoxic study. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Bengue, M.-S.; Mesnard, T.; Chai, F.; Maton, M.; Gaucher, V.; Tabary, N.; García-Fernandez, M.-J.; Sobocinski, J.; Martel, B.; Blanchemain, N. Evaluation of a Medical Grade Thermoplastic Polyurethane for the Manufacture of an Implantable Medical Device: The Impact of FDM 3D-Printing and Gamma Sterilization. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojio, K.; Furukawa, M.; Nonaka, Y.; Nakamura, S. Control of Mechanical Properties of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Elastomers by Restriction of Crystallization of Soft Segment. Materials 2010, 3, 5097–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, A.; Haddar, N.; Elleuch, K.; Bienvenu, Y. Impact of aging conditions on mechanical properties of thermoplastic polyurethane. Mater. Des. 2010, 31, 4194–4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, A.P.; Wei, Y. Three-dimensional printed thermoplastic polyurethane on fabric as wearable smart sensors. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2023, 237, 1678–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, J.; Kasprzyk, P. Thermoplastic polyurethanes derived from petrochemical or renewable resources: A comprehensive review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2018, 58, E14–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Seethamraju, K.; Delaney, J.; Willoughby, P.; Faust, R. Long-term in vitro hydrolytic stability of thermoplastic polyurethanes. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 3798–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzens, D.; Ojha, U.; Kulkarni, P.; Faust, R.; Desai, S. Long term in vitro biostability of segmented polyisobutylene-based thermoplastic polyurethanes. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2010, 95A, 774–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yan, L.; Zeng, Z.; Chen, L.; Ma, M.; Luo, R.; Bian, J.; Lin, H.; Chen, D. TPU/PLA nanocomposites with improved mechanical and shape memory properties fabricated via phase morphology control and incorporation of multi-walled carbon nanotubes nanofillers. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2020, 60, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Ge, J.; Qi, D.; Gao, J.; Chen, Y.; Liang, J.; Fang, D. A multiscale elasto-plastic damage model for the nonlinear behavior of 3D braided composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2019, 171, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zan, Y.; Piedrahita-Bello, M.; Alavi, S.E.; Molnár, G.; Tondu, B.; Salmon, L.; Bousseksou, A. Soft Actuators Based on Spin-Crossover Particles Embedded in Thermoplastic Polyurethane. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 202200432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xia, H.; Yao, J.; Ni, Q.-Q. Electrically induced soft actuators based on thermoplastic polyurethane and their actuation performances including tiny force measurement. Polymer 2019, 180, 121678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasa, O.; Toshimitsu, Y.; Michelis, M.Y.; Jones, L.S.; Filippi, M.; Buchner, T.; Katzschmann, R.K. An Overview of Soft Robotics. Annu. Rev. Control Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.J.; Hong, N.; Ryu, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S. Soft robot review. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2017, 15, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Patel, K.; Purohit, R. Improved shape memory and mechanical properties of microwave-induced thermoplastic polyurethane/graphene nanoplatelets composites. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 285, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albozahid, M.; Naji, H.Z.; Alobad, Z.K.; Saiani, A. TPU nanocomposites tailored by graphene nanoplatelets: The investigation of dispersion approaches and annealing treatment on thermal and mechanical properties. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 8269–8307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, P.; Ceseracciu, L.; Marras, S.; Athanassiou, A.; Bayer, I.S. Electrical conductivity enhancement in thermoplastic polyurethane-graphene nanoplatelet composites by stretch-release cycles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, J.; Jafari, S.H.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Sadeghi, G.M.M.; Zohuri, G.; Hejazi, I.; Simon, F. Fabrication of robust and thermally stable superhydrophobic nanocomposite coatings based on thermoplastic polyurethane and silica nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 347, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Shi, J.; Shen, B.; Huang, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Lai, Y. A superhydrophobic TPU/CNTs@SiO2 coating with excellent mechanical durability and chemical stability for sustainable anti-fouling and anti-corrosion. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 434, 134605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, A.; Guermazi, N.; Elleuch, K.; Ayedi, H.F. Study of UV-aging of thermoplastic polyurethane material. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Guo, J.; Shao, C.; Chen, C. Flexible Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites with Ultraviolet Resistance for Fused Deposition Modeling 3D Printing. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 11, e1810–e1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Sheng, J.; Yin, X.; Yu, J.; Ding, B. Functional modification of breathable polyacrylonitrile/polyurethane/TiO2 nanofibrous membranes with robust ultraviolet resistant and waterproof performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 508, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. Improved thermal conductivity of thermoplastic polyurethane via aligned boron nitride platelets assisted by 3D printing. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 120, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A.; Maqbool, M.; Lv, R.; Usman, A.; Guo, H.; Aftab, W.; Niu, H.; Liu, M.; Bai, S.-L. Surface modified boron nitride towards enhanced thermal and mechanical performance of thermoplastic polyurethane composite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 218, 108871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.-H.; Su, C.-Y.; Chi, P.-W.; Chandan, P.; Cho, C.-T.; Chi, W.-Y.; Wu, M.-K. Generation of Self-Assembled 3D Network in TPU by Insertion of Al2O3/h-BN Hybrid for Thermal Conductivity Enhancement. Materials 2021, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabuani, D.; Bellucci, F.; Terenzi, A.; Camino, G. Flame retarded Thermoplastic Polyurethane (TPU) for cable jacketing application. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 2594–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Deng, C.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Huang, S.-C.; Wei, W.-C.; Yang, A.-H.; Zhao, H.-B.; Wang, Y.-Z. Flame-retarded thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer: From organic materials to nanocomposites and new prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 417, 129314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, R.; Kausar, A.; Siddiq, M. Advances in thermoplastic polyurethane composites reinforced with carbon nanotubes and carbon nanofibers: A review. J. Plast. Film Sheeting 2015, 31, 186–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambuken, P.V.; Stretz, H.A.; Koo, J.H.; Messman, J.M.; Wong, D. Effect of addition of montmorillonite and carbon nanotubes on a thermoplastic polyurethane: High temperature thermomechanical properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 102, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbur, Y.; Tayfun, U. Investigating mechanical, thermal, and flammability properties of thermoplastic polyurethane/carbon nanotube composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2018, 31, 1661–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, P.; Lavorgna, M.; Piscitelli, F.; Acierno, D.; Di Maio, L. Thermoplastic polyurethane films reinforced with carbon nanotubes: The effect of processing on the structure and mechanical properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Weng, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Guan, L.; Shi, J.; Liu, L. Enhanced dielectric performance of TPU composites filled with Graphene@poly(dopamine)-Ag core-shell nanoplatelets as fillers. Polym. Test. 2020, 90, 106671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzah, Z.F.; Fakhry, S.; Allami, T.G.; Yuhana, N.Y.; Alamiery, A. Enhancement of the Properties of Hybridizing Epoxy and Nanoclay for Mechanical, Industrial, and Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayil, R.; Arumugaprabu, V.; Das, O.; Lenin, A. A Brief Review on Effect of Nano fillers on Performance of Composites. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1059, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, R.; Malucelli, G. Rheological Behavior of Polymer/Carbon Nanotube Composites: An Overview. Materials 2020, 13, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alasfar, R.; Ahzi, S.; Wang, K.; Barth, N. Modeling the mechanical response of polymers and nano-filled polymers: Effects of porosity and fillers content. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenta, E.W.; Mebratie, B.A. Advancements in carbon nanotube-polymer composites: Enhancing properties and applications through advanced manufacturing techniques. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.C. Infrared Spectroscopy of Polymers XIII: Polyurethanes. Spectroscopy 2023, 38, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.M.K.; Rajavelu, M.S.; Mandal, A.B. Thermoplastic polyurethane/single-walled carbon nanotube composites for low electrical resistance surfaces. High Perform. Polym. 2012, 25, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Abeykoon, C.; Karim, N. Investigation into the effects of fillers in polymer processing. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2021, 4, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkina, W.; Dudzik, S. Infrared Thermography: Errors and Uncertainties; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Allami, T.; Alamiery, A.; Nassir, M.H.; Kadhum, A.H. Investigating Physio-Thermo-Mechanical Properties of Polyurethane and Thermoplastics Nanocomposite in Various Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ngo, I.-L.; Jeon, S.; Byon, C. Thermal conductivity of transparent and flexible polymers containing fillers: A literature review. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 98, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.M.A.; Felisberti, M.I. Thermal conductivity of PET/(LDPE/AI) composites determined by MDSC. Polym. Test. 2004, 23, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bai, Y.; Yu, K.; Kang, Y.; Wang, H. Excellent thermal conductivity and dielectric properties of polyimide composites filled with silica coated self-passivated aluminum fibers and nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 252903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, Z.; Ali, M.; Lee, E.-J.; Zubair, Z.; Lee, K.H. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Nano-Carbon-Reinforced Polymeric Nanocomposites: A Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilito, J.M.; Bonavides, J.; Hurtado, S.; De La Pava, E.E.; De Jesús, A.M. Thermal, Viscoelastic, and Electrical Properties of MWCNT-Doped Thermoplastic Polyurethane. Polymers 2024, 16, 11225840. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Byun, J.H.; Oh, Y.; Jung, Y.J.; Chou, T.W. Fast Triggering of Shape Memory Polymers Using an Ultrathin CNT Sponge–Polymer Composite. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24148. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Rahman, M.; Shuvo, M.A.I.; Kim, H.C.; Choi, H.J. A Review of Electro-Active Shape Memory Polymer Composites. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Description | Sample Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Neat TPU | TPU |

| 2 | TPU with 1 wt.% of AlNPs | 1 wt.% AlNPs |

| 3 | TPU with 3 wt.% of AlNPs | 3 wt.% AlNPs |

| 4 | TPU with 1 wt.% of MWCNTs | 1 wt.% MWCNTs |

| 5 | TPU with 3 wt.% of MWCNTs | 3 wt.% MWCNTs |

| 6 | TPU with 3 wt.% of MWCNTs and AlNPs with a ratio of 2:1 | 3 wt.% hybrid (2:1) |

| 7 | TPU with 3 wt.% of MWCNTs and AlNPs with a ratio of 5:1 | 3 wt.% hybrid (5:1) |

| 8 | TPU with 3 wt.% of MWCNTs and AlNPs with a ratio of 10:1 | 3 wt.% hybrid (10:1) |

| Sample | Length (mm) | Width (mm) | Thickness (mm) | Density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPU | 62.8 ± 0.46 | 63.0 ± 0.19 | 4.3 ± 0.09 | 1.21 ± 0.002 |

| 1 wt.% AlNPs | 63.2 ± 0.31 | 62.5 ± 0.71 | 4.7 ± 0.16 | 1.20 ± 0.004 |

| 3 wt.% AlNPs | 62.8 ± 1.31 | 62.4 ± 1.05 | 4.9 ± 0.72 | 1.21 ± 0.009 |

| 1 wt.% MWCNTs | 62.5 ± 0.46 | 62.6 ± 0.53 | 5.3 ± 0.38 | 1.20 ± 0.03 |

| 3 wt.% MWCNTs | 62.2 ± 1.18 | 62.6 ± 0.28 | 5.3 ± 0.32 | 1.21 ± 0.03 |

| 3 wt.% hybrid (2:1) | 62.8 ± 0.53 | 62.6 ± 0.38 | 4.9 ± 0.28 | 1.21 ± 0.004 |

| 3 wt.% hybrid (5:1) | 62.7 ± 0.71 | 63.1 ± 0.21 | 5.2 ± 0.21 | 1.21 ± 0.01 |

| 3 wt.% hybrid (10:1) | 62.6 ± 0.75 | 62.7 ± 0.44 | 4.8 ± 0.21 | 1.22 ± 0.01 |

| Sample Name | Tg (°C) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| TPU | 39.7 | 157.9 |

| 1 wt.% AlNPs | 36.3 | 169.8 |

| 3 wt.% AlNPs | 33.8 | 171.7 |

| 1 wt.% MWCNTs | 36.0 | 163.5 |

| 3 wt.% MWCNTs | 34.1 | 173.9 |

| 3 wt.% hybrid (2:1) | 34.9 | 168.2 |

| 3 wt.% hybrid (5:1) | 30.8 | 169.8 |

| 3 wt.% hybrid (10:1) | 32.9 | 171.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellisario, D.; Burratti, L.; Maiolo, L.; Maita, F.; Lucarini, I.; Quadrini, F. Compression Molding of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites for Shape Memory Polymer Actuation. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120681

Bellisario D, Burratti L, Maiolo L, Maita F, Lucarini I, Quadrini F. Compression Molding of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites for Shape Memory Polymer Actuation. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120681

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellisario, Denise, Luca Burratti, Luca Maiolo, Francesco Maita, Ivano Lucarini, and Fabrizio Quadrini. 2025. "Compression Molding of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites for Shape Memory Polymer Actuation" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120681

APA StyleBellisario, D., Burratti, L., Maiolo, L., Maita, F., Lucarini, I., & Quadrini, F. (2025). Compression Molding of Thermoplastic Polyurethane Composites for Shape Memory Polymer Actuation. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 681. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120681