3.1. Thermal Characterisation

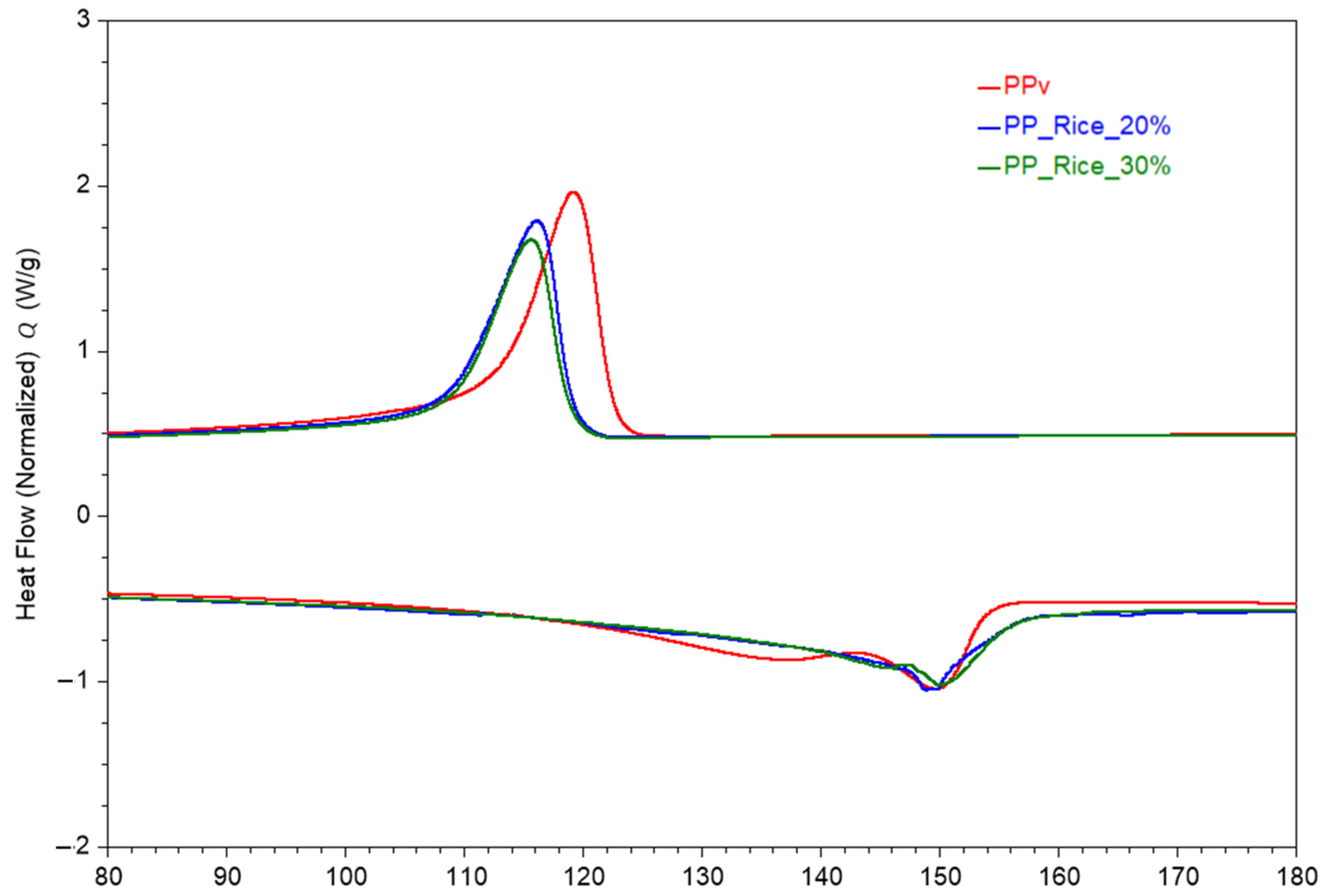

The DSC thermograms (

Figure 1) show that the melting temperature exhibited minimal variation with increasing filler content. The numerical results are presented in

Table 1, while

Table 2 shows the relative variation in thermal properties compared with virgin PP. Similar trends have been reported in the literature by Rosa et al. [

6], Zhiltsova et al. [

4], and Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9]. As shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1 and

Table 2, the crystallisation temperature decreased with the incorporation of rice husk compared to virgin PP, a trend also reported by Zhiltsova et al. [

4] and Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9]. However, Rosa et al. [

6] noted a slight increase in

in the composite with 30% rice husk content. Regarding the enthalpies of melting and crystallisation, both decreased with increasing rice husk content, as documented in the works of Zhiltsova et al. [

4] and Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9]. Despite these changes, the degree of crystallinity significantly increased with the introduction of particles as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. This increase confirms that the micronised rice husk particles act as nucleating agents, promoting PP crystallisation around the particles, as previously demonstrated by Zhiltsova et al. [

4] and Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9]. Furthermore, the increase in crystalline is also related to a greater rigidity of the material [

4,

29], suggesting that all the tested composites had a higher modulus of elasticity and lower ductility.

A comparison of the melting and crystallisation enthalpies between the composites containing micronised rice husk and those with 0.5 mm particle size [

4], as shown in

Table 1, indicates that both exhibit similar thermal behaviour, particularly at 20% fibre content. Likewise, the melting (

) and crystallisation (

) temperatures showed no significant differences, with only a slight decrease observed in the composites with micronised rice husk. These results suggest that particle size distribution significantly impacts the composites’ thermal properties.

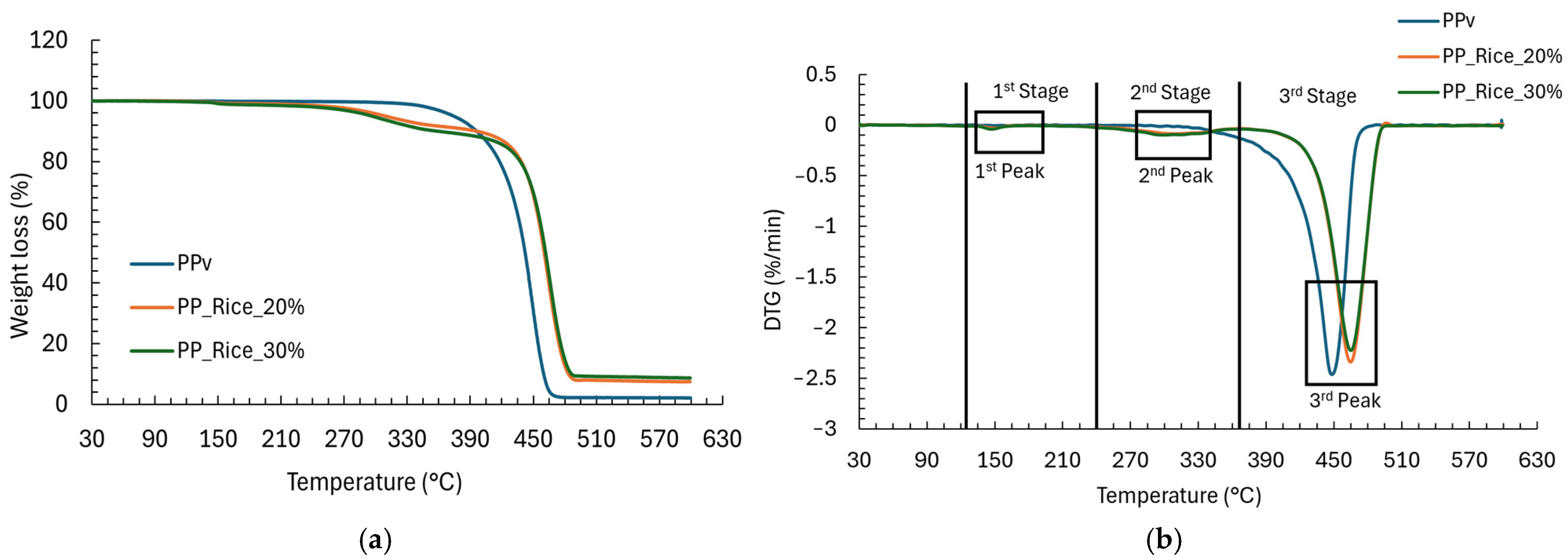

The thermogravimetric analysis of PP composites with micronised rice husk particles (

Figure 2a) revealed three main stages of mass loss, which were further clarified by the derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curve (

Figure 2b). The first stage, occurring between 30 °C and approximately 230 °C, shows a slight mass loss, initially attributed to water evaporation. However, a distinct DTG peak around 148–149 °C (

Figure 2b) suggests the volatilisation of organic extractives from the rice husk, a process likely enhanced by its micronised nature. The second stage, between 230 °C and 370 °C, presents a more pronounced mass loss associated with the thermal degradation of hemicellulose and cellulose, as well as the early stages of lignin decomposition. The DTG peak temperatures observed around 303–310 °C (

Figure 2b) further confirm the occurrence of these degradation processes in both composites. Moreover, these initial signs of the composites’ thermal degradation were further confirmed by comparing the temperatures at 5% mass loss, a widely accepted and quantifiable indicator of the onset of thermal degradation. As shown in

Table 3, the 20% and 30% composites exhibited temperatures of 309.2 °C and 296.2 °C, respectively, whereas neat PP showed 5% mass loss at a much higher temperature (374.1 °C), indicating greater thermal stability at the onset of thermal degradation.

The third stage, from 370 °C to 495 °C, corresponds to the main degradation of the PP matrix, characterised by a sharp mass loss and a DTG peak (

Figure 2b) that is between 464 and 466 °C, typical of rapid polymer decomposition. Beyond 500 °C, the TGA curve (

Figure 2a) stabilises, indicating the presence of a residual mass around 7.3% for the PP_Rice_20% and 8.7% for the PP_Rice_30% that is mainly attributed to inorganic ash, such as silica, and partially resistant lignin. The virgin PP co-polymer exhibited a single thermal degradation event. Decomposition began at 313.7 °C with only one peak observed in the derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curve (

Figure 2b) at 448.2 °C, referred to in

Table 3 as third stage DTG peak, which was subtantially lower than the homologe values of 464.1 °C for PP_Rice_20% and 465.8 °C for PP_Rice_30%. Above 500 °C, the ash content showed only a minor change, indicating that the PPv had nearly fully volatilized by 600 °C, leaving just 0.8% residue [

13].

Overall, the TGA and DTG analyses show that most of the mass loss in the composites occurs between 400 °C and 500 °C, and the addition of rice husk appears to enhance the resistance to thermal degradation of the PP matrix, in agreement with previous studies [

6,

9,

13]. The silica present in rice husk forms a thermally stable layer that restricts heat transfer and volatile diffusion during polymer degradation [

31]. The earlier onset of thermal degradation observed in the micronised rice husk composites, compared with neat PP, can be attributed to the decomposition of the lignocellulosic components of the filler, namely hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, which degrade at lower temperatures than the PP matrix. Nevertheless, during the main degradation stage of the polymer, the thermally stable silica phase enhances thermal resistance by forming a protective barrier that limits heat and mass transfer. This behaviour is evidenced by the shift in the third-stage DTG peaks to higher temperatures, reduced mass loss, and increased residual ash content, confirming the effective barrier and reinforcement roles of the rice husk filler in enhancing the overall thermal stability of the PP matrix.

The comparison between the present results and those from the study by Zhiltsova et al. [

13] (

Table 3) shows that polypropylene composites with micronised rice husk exhibit slightly different thermal behaviour compared to 0.5 mm rice husk fibres. In both cases, it is observed that increasing the rice husk content leads to greater mass loss during the second stage of thermal degradation, which is associated with the breakdown of biomass components such as hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, and to lower mass loss during the third stage, corresponding to the degradation of the PP matrix. This occurs because composites with higher rice husk content contain less polymer matrix. However, micronised rice husk particles, due their better dispersion in the PP matrix and larger surface contact area, promotes more efficient interfacial adhesion, which restricts polymer chain mobility and consequently delays the thermal degradation of PP, particularly at higher temperatures. As a result, composites containing micronised rice husk particles show reduced mass loss in the final stage.

Although the PP composite with 20% non-micronised rice husk presents a slightly higher onset temperature in the second stage, it exhibits greater mass loss during this phase and a lower degradation peak in the third stage. Therefore, the composite containing 20% micronised rice husk demonstrates better overall thermal stability, as evidenced by lower mass loss, a higher degradation peak in the third stage, and a greater percentage of residual ash. These findings confirm the protective role of silica and the barrier effect of the micronised particles, which hinder heat and mass transfer during degradation and thereby delay the thermal decomposition of the polymer matrix.

3.2. Mechanical Characterisation

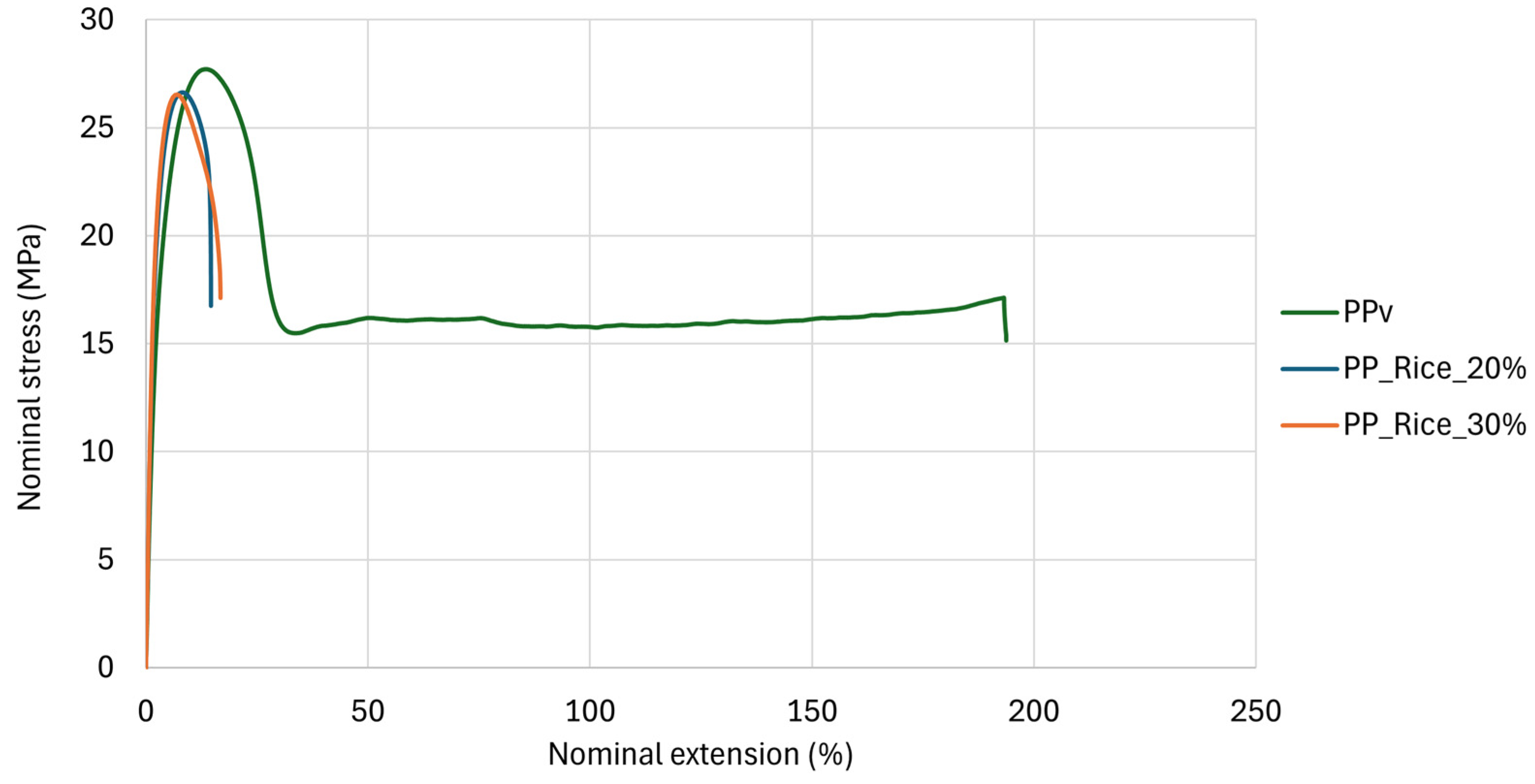

Regarding mechanical properties, as illustrated in

Figure 3 and summarised in

Table 4, the Young’s modulus (E) increased about 4% for PP_Rice_20% and 10% for PP_Rice_30% (

Table 5), in line with the results of Zhiltsova et al. [

4], Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9] and Erdogan and Huner [

11]. The increase in viscosity observed in the discussed further rheological tests and the increase in the degree of crystallinity suggests an enhancement in the stiffness of the polymer matrix, which naturally results in a higher Young’s modulus [

32].

This stiffening effect was statistically validated through one-way ANOVA (the results are shown in

Table 6), which revealed a highly significant difference between the three groups (PPv, PP_Rice_20%, and PP_Rice_30%) with a

p-value < 0.0001 and an F-value of 31.73. The coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.75) indicated that a large proportion of the variability in Young’s modulus was explained by the filler content. Post hoc analysis using Tukey’s HSD test confirmed that all pairwise comparisons between groups were statistically significant (α = 0.05), showing a clear and progressive increase in stiffness with increasing filler content.

As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 5, both composites exhibited a slight decrease in yield stress (

) when compared to PPv. This trend has been reported by several authors [

4,

9,

11] and is attributed to the poor adhesion between the hydrophobic matrix and the hydrophilic fibres. Statistical analysis ANOVA (

Table 6) confirmed that this decrease is significant (F(2, 21) = 37.19,

p < 0.0001), with all groups showing statistically different means according to Tukey’s test. In this notation, 2 and 21 represent the degrees of freedom between and within groups, respectively. The R

2 value of 0.78 indicates that filler content explains a substantial proportion of the variance in yield stress, reinforcing the conclusion that the reduction is systematic and not due to random error. This result indicates that the addition of rice husk particles consistently reduces the yield stress, likely due to stress concentration points and weak interfacial bonding. As for the stress at break (

), a slight increase (15%) was observed, particularly in the composite containing a higher filler content, as evidenced by Zhiltsova et al. [

4] and Nourbakhsh et al. [

12]. The ANOVA results presented in

Table 6 support this observation (F(2, 15) = 6.21,

p = 0.011), with a statistically significant difference only between the virgin PP and the PP_Rice_30% (

p = 0.008). No significant difference was found between the 20% composite and the other groups. The coefficient of determination for this property was R

2 = 0.45, suggesting that filler content explains less than half of the variability in the stress at break. This suggests that only at higher fibre content is the interfacial reinforcement sufficient to improve the material’s tensile performance at fracture.

Finally, the yield strain (

and the nominal strain at break (

) decreased with the addition of rice husk particles, revealing a more brittle behaviour in the composites, especially in those with 30% of rice husk, which was also noted by Zhiltsova et al. [

4]. The yield strain was reduced by 38% in PP_Rice_20% and by 49% in PP_Rice_30%. An even more substantial reduction was observed in the strain at break, which decreased by 87% and 93%, respectively. These substantial losses in ductility reflect significant molecular-level changes, likely associated with restricted polymer chain mobility and limited capacity for plastic deformation due to the presence of rigid lignocellulosic fillers.

To assess the influence of fibres’ granulometry on the mechanical properties of the composites, a comparison was made with the results reported by Zhiltsova et al. [

4] included in

Table 4. Regarding Young’s modulus, a decrease was observed with reduced particle size, contrary to what other authors reported [

15,

16]. This discrepancy may be attributed to the distinct morphology and interface characteristics of micronised particles, which, despite offering better dispersion, are not aligned and oriented to provide effective tensile reinforcement [

33]. Xu et al. [

34] concluded that very fine, powder-like fibres lead to lower stiffness due to reduced structural continuity. In contrast, yield strength increased with decreasing particle size. This may be explained by the improved dispersion and stress transfer provided by micronised particles, which promote better fibre–matrix interaction. Larger particles, on the other hand, tend to agglomerate and introduce micro voids during processing, acting as stress concentrators and weakening the composite [

15,

16,

34]. Stress at break was only slightly influenced by particle size, showing a small decrease in the composites with micronised filler. When rice husk filler are micronised, their reduced size improves dispersion in the matrix but also reduces their aspect ratio and structural reinforcement capacity. As a result, although dispersion is increased, the smaller fibres are less effective in resisting fracture under tensile stress. This leads to a slight decrease in the breaking stress. Finally, composites with 0.5 mm fibres exhibited lower nominal strain at break, indicating a more brittle behaviour compared to the more ductile fracture of composites with micronised rice husk particles.

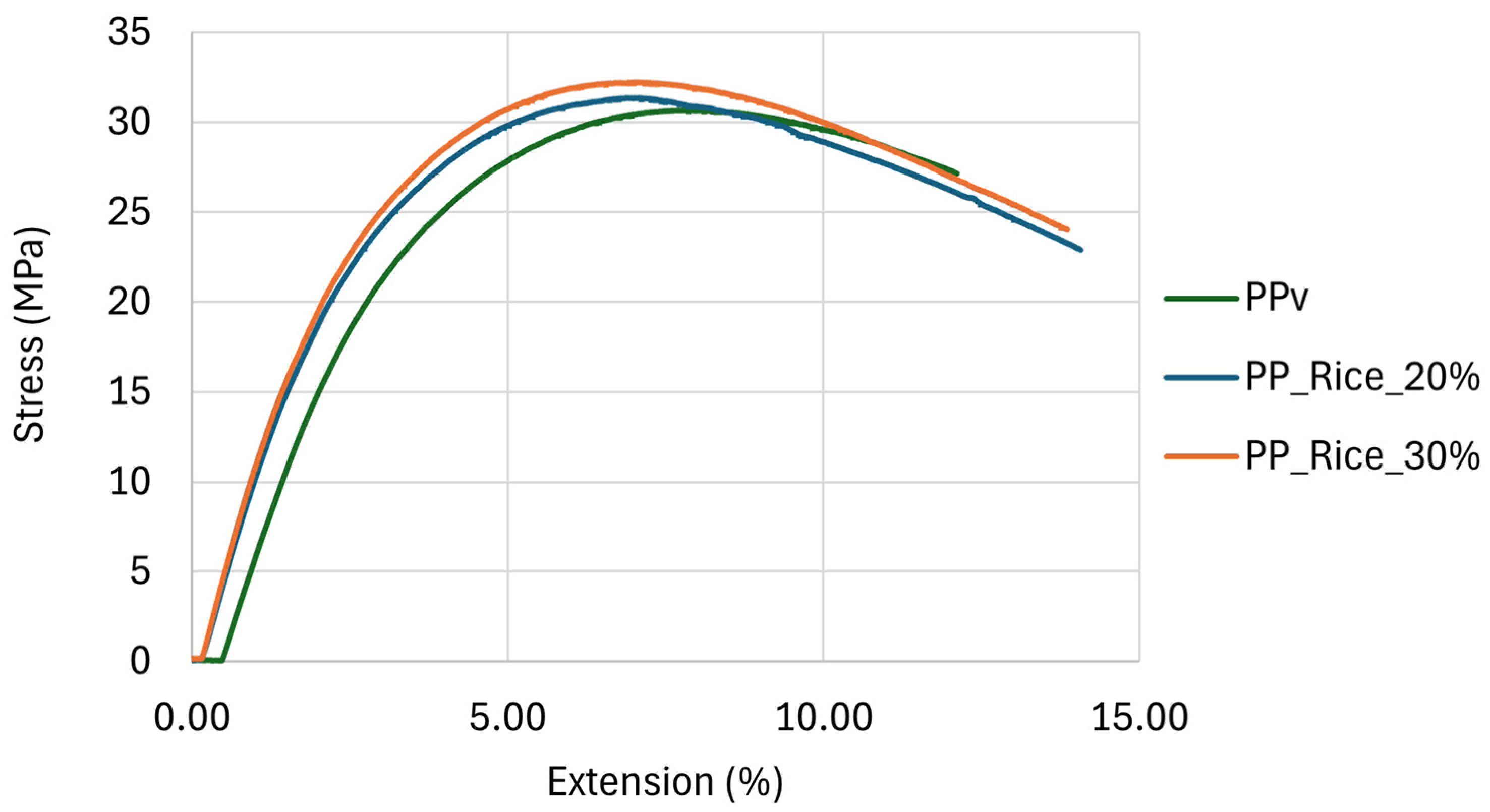

According to the data presented in

Figure 4 and

Table 7, the incorporation of micronised rice husk particles led to a slight enhancement of the flexural properties. The flexural modulus (E

f) increased by approximately 11% in the composite PP_Rice_30%, a result that is consistent with the studies of Zhiltsova et al. [

4], Nourbakhsh et al. [

12], Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9], and Erdogan and Huner [

11], who attributed this Flexural stress–strain curves of virgin PP (PPv) and PP/rice fibre composites (20 and 30 wt%) strain curve shown in

Figure 4, where a steeper initial slope is observed in the samples with higher filler content, indicating a stiffer behaviour.

The results of statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA (significance level: α = 0.05) presented in

Table 8 confirmed that this increase in flexural modulus is significant (F(2, 27) = 32.40,

p < 0.0001), indicating that the addition of rice husk particles effectively enhances the stiffness of the PP matrix. In this test, the values in parentheses represent the degrees of freedom: 2 for the number of groups minus one (between-group variation), and 27 for the total number of observations minus the number of groups (within-group variation). Post hoc Tukey tests further revealed that both 20% and 30% filler content composites were significantly different from the neat PP, although no significant difference was found between the 20% and 30% groups. Moreover, the coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.71) indicates that 71% of the variance in flexural modulus can be explained by the filler content, suggesting a strong relationship between the independent variable (filler percentage) and the mechanical response.

Similarly, the flexural strength (

σf) also showed a slight increase, as reported by Nourbakhsh et al. [

12] and Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9]. However, ANOVA results (

Table 8) indicated that these differences were not statistically significant (F(2, 27) = 2.34,

p = 0.115), suggesting that the observed variation in flexural strength may be due to experimental variation rather than a consistent effect of particle reinforcement. This interpretation is supported by the low R

2 value (0.15), which indicates that only 15% of the variability in flexural strength is explained by filler content. Some studies, such as those by Zhiltsova et al. [

4], Erdogan and Huner [

11], and Aridi et al. [

10], reported a decrease in this property, which was explained by the formation of agglomerates, moisture absorption, and poor adhesion between the fibres and the matrix.

A comparison between the composites with micronised rice husk particles and those with 0.5 mm particles from Zhiltsova et al. [

4] (

Table 7) shows that the flexural modulus is lower for the micronised composites, while their flexural strength is higher. Flexural strength, which indicates a material’s ability to resist stress before fracture, is improved in composites with micronised particles due to better load dispersion and, hence, better stress transfer, confirmed by SEM micrographs (

Figure 5) discussed further. In contrast, larger particles tend to agglomerate, leading to defects and stress concentrations that reduce strength [

35,

36,

37,

38]. On the other hand, flexural modulus reflects material stiffness. Larger particles increase rigidity by acting as mechanical barriers, whereas smaller particles reduce stiffness due to their limited reinforcement effect and reduced structural continuity [

34].

3.4. Morphological and Chemical Characterisation

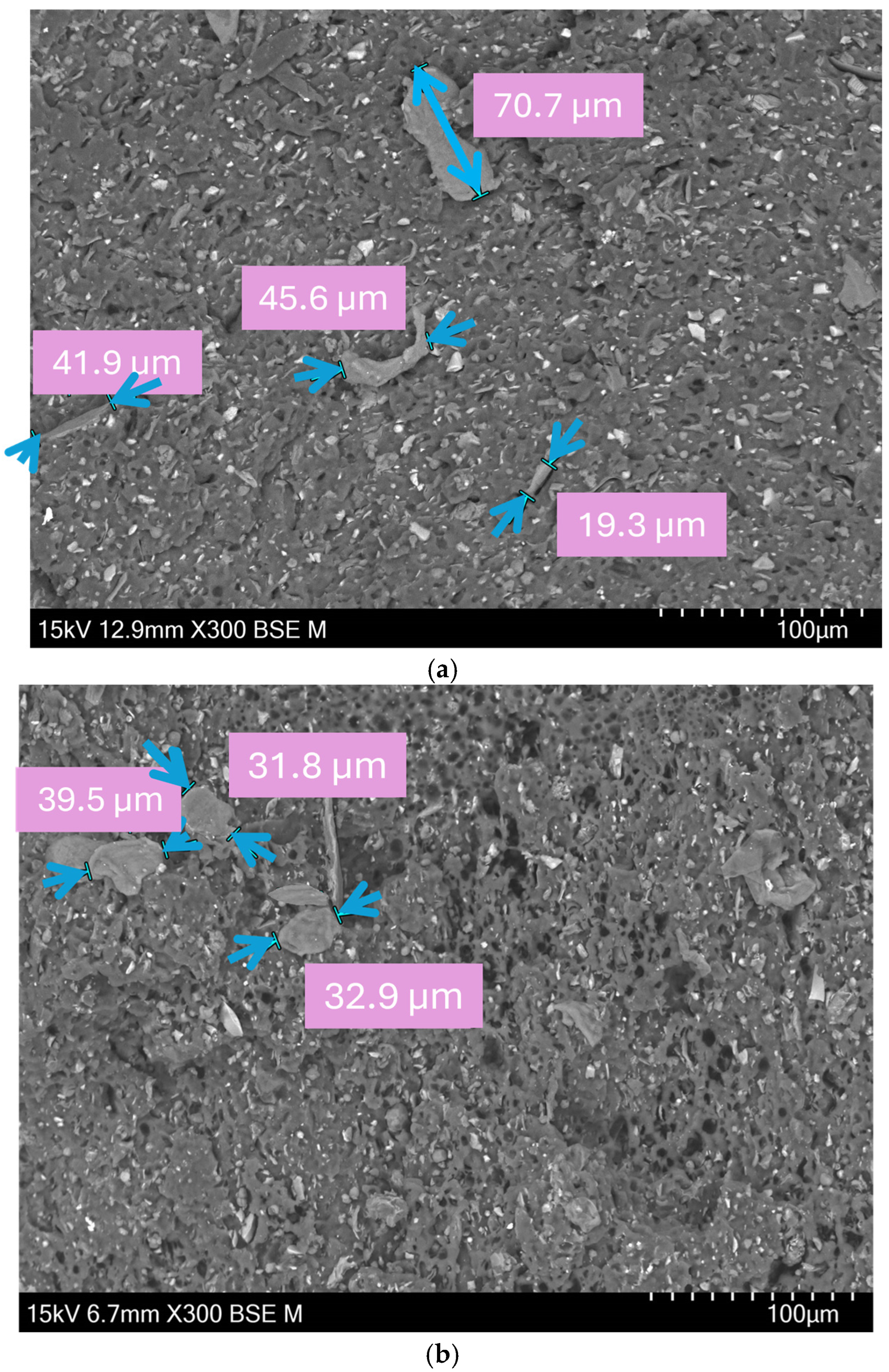

As for the morphological characterisation,

Figure 5 shows the SEM images obtained during the analysis of the fracture surface of the tensile specimens of the biocomposites under study. The images reveal that the particles in the PP composites with micronised rice husk are randomly dispersed and exhibit varying sizes. Comparing the composites with 20% and 30% rice husk particles reveals better particles dispersion in the 20% composite.

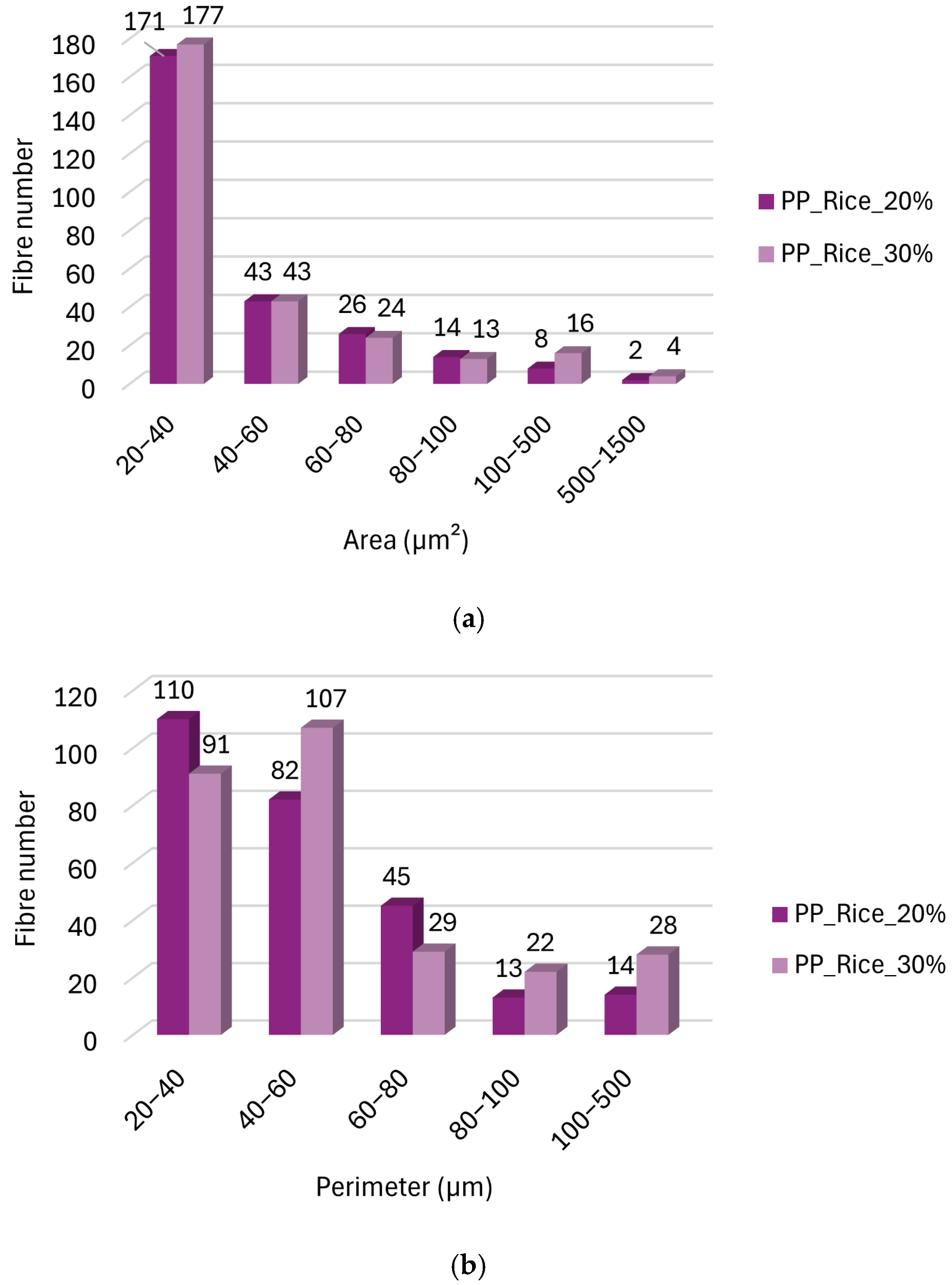

Using ImageJ software (version 1.54g), the number of particles in the SEM images was quantified, and the perimeter and area of each detected particle were also measured. The analysis focused on a sample area of 0.1007 mm

2. The particle size distribution analysis (

Figure 6a,b) indicates that the PP_Rice_30% composite exhibits a slightly broader granulometric range than the PP_Rice_20% composite. As shown in

Figure 6a, although both composites have most particles concentrated in the 20–40 µm

2 range, a greater number of particles in PP_Rice_30% fall within the larger size areas (100–500 µm

2 and 500–1500 µm

2) (

Figure 6a) and above 80 µm in perimeter (

Figure 6b). These results suggest a broader and more heterogeneous particle size distribution in the PP_Rice_30% composite, due to the increased presence of larger particles compared to the PP_Rice_20% composite. Additionally, the broader particle size distribution observed in the PP_Rice_30% composite, as revealed by SEM analysis (

Figure 6a,b), is consistent with its significantly reduced strain at break and yield strain (

Table 4), suggesting that the presence of larger particles may have introduced local stress concentrations. In contrast, the more uniform particle distribution in the PP_Rice_20% composite appears to promote more homogeneous stress transfer within the matrix, which correlates with its comparatively higher ductility.

In the PP_Rice_30%, particles agglomeration and higher presence of voids and porosity are observed (

Figure 5b), suggesting poor adhesion between the matrix and the fibres, which may compromise the mechanical properties of the material. These results are consistent with previous studies [

9,

10], which indicated that increasing the fibre content leads to more voids and fibre detachment, impairing the mechanical performance of the composites. These conclusions can be corroborated by the works of Zhiltsova et al. [

4], Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9], and Aridi et al. [

10], which correlated the fibre content increase with higher number of voids and fibres detachment. Furthermore, Zhiltsova et al. [

4] and Hidalgo-Salazar and Salinas [

9] concluded that the presence of gaps indicates weak adhesion between the PP matrix and the rice husk fibres, which may be related to the poor performance of these composites during tensile tests, particularly in terms of fracture strain and yield stress. As shown in

Table 4, the nominal strain at break of the composites was significantly lower than that of virgin PP. Although the poor adhesion between the PP matrix and rice husk particles is a common drawback in natural-fibre-reinforced composites, several approaches have been proposed in the literature to mitigate this issue. Surface treatments of fibres (e.g., alkali treatment, silane coupling agents, or compatibilisers such as maleic anhydride-grafted polypropylene) have been shown to improve interfacial bonding, reduce void formation, and enhance the overall mechanical performance of the composites. Alternatively, adhesive or coating techniques have also been investigated as effective strategies to promote better stress transfer across the fibre–matrix interface [

39].

A comparison between the micrographs of the micronised composites and those reported by Zhiltsova et al. [

4], who studied PP composites with 20% and 30% rice husk fibres with the nominal 0.5 mm fibres’ size, reveals that the micronised composites exhibit fewer agglomerations. Additionally, composites with larger particle size exhibit more porous regions with larger voids, indicating inferior fibre–matrix adhesion. These findings are consistent with the studies of Zafar et al. [

40] and Onuoha et al. [

41], which investigated the influence of particle size on the properties of polystyrene composites with natural fibres and PP composites with maize fibres, respectively.

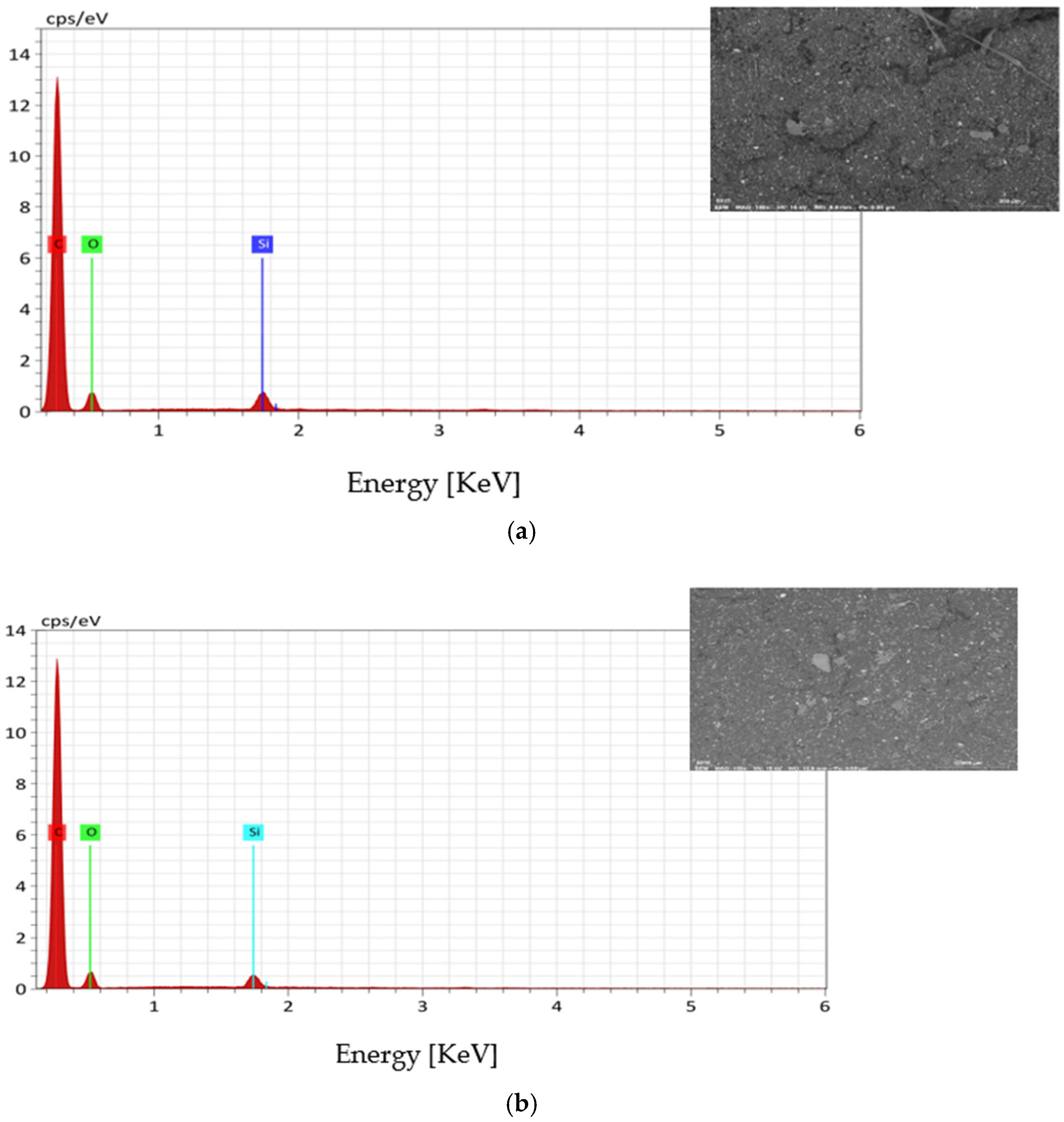

Additionally, the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis revealed that the composites are primarily composed of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and silicon (Si) as illustrated in the EDS spectra presented in

Figure 7.

The presence of carbon is related to the PP matrix, while the presence of O and Si comes from the incorporation of rice husk. It is also noteworthy that, as expected, since the particle content is higher, the amount of Si and O in the PP_Rice_30% is greater than in the PP_Rice_20%, as show in

Table 10. These findings align with those reported in the previously mentioned work by Zhiltsova et al. [

4] and Erdogan and Huner [

11], who analysed PP composites with rice husk fibres using infrared spectroscopy and detected all the elements mentioned. It should be noted, however, that the EDS analysis was carried out on the fracture surfaces of the composites, and therefore the spectra reflect the combined contribution of both the polymer matrix and the rice husk. Analysis of pure rice husk particles was not conducted, as it was beyond the scope of this study.

3.5. Rheological Characterisation

Three rheological models, the Cross–WLF, Carreau–Yasuda, and Carreau–Yasuda–WLF, were selected to describe the viscosity behaviour of the PP rice husk composites. By comparing the results of the models presented in

Table 11, it was observed that the parameter

exhibited significant variations. As expected,

decreased with increasing temperature and increased with higher filler content for the same temperature, a typical behaviour of polymer composites. The increase with filler loading reflects the added resistance to flow caused by the presence of rigid particles, which restrict the movement of the polymer chains. In the Cross–WLF model,

values ranged between 400 and 1600 Pa·s, indicating sensitivity to both temperature and particle content. In contrast, the Carreau–Yasuda model yielded higher values, often exceeding 2500 Pa·s for composites with a higher percentage of rice husk. This is attributed to the fact that the Carreau–Yasuda model adjusts

individually for each temperature and composition, capturing the increasing resistance to flow at higher filler contents more clearly. The Carreau–Yasuda–WLF model showed intermediate values with less variation, since the temperature dependence is incorporated through the WLF shift factor, and a single value of

is fitted for all temperatures. Regarding the

, also presented in

Table 11, which characterises the degree of pseudoplasticity, the Cross–WLF model indicated moderate pseudoplastic behaviour (

ranging from 0.22 to 0.27). The Carreau–Yasuda model suggested higher pseudoplasticity (

between 0.14 and 0.19), whereas the Carreau–Yasuda–WLF model exhibited very low values (

between 0.013 and 0.015), suggesting an almost Newtonian behaviour, which is inconsistent with fibre-reinforced lignocellulosic materials [

42]. The quality of the fittings was also assessed using the coefficient of determination (R

2). The Carreau–Yasuda model achieved the best results (R

2 > 0.998), followed by the Cross–WLF model (R

2 > 0.999). Although the Carreau–Yasuda–WLF model accounts for the influence of temperature, it yielded the lowest R

2 values (ranging from 0.934 to 0.977).

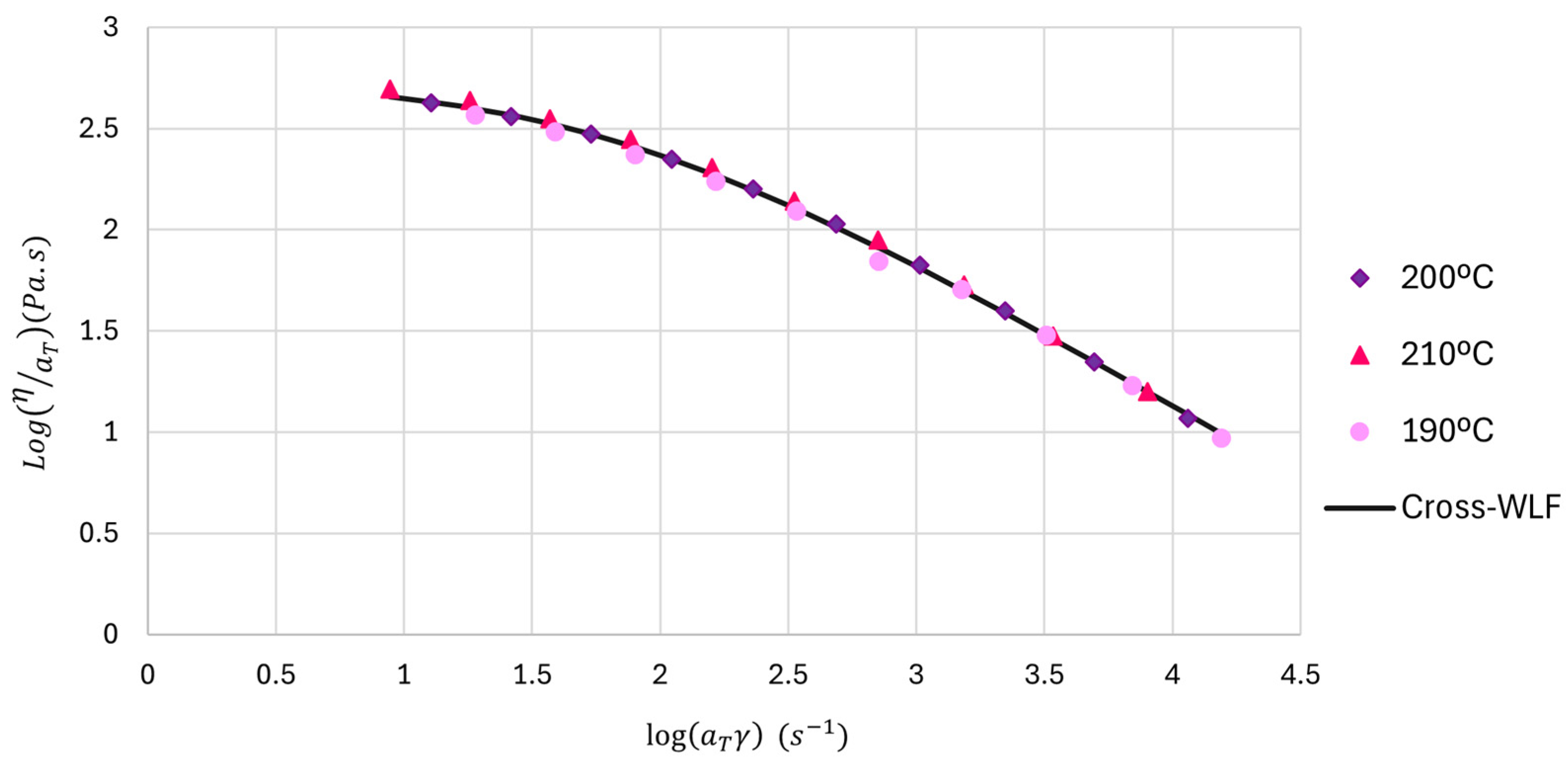

Although the Carreau–Yasuda model achieved the highest R2, this result is mainly due to its ability to adjust individually at each temperature and composition, which improves statistical fitting but reduces physical consistency. In contrast, the Cross–WLF model couples viscosity and temperature through the WLF shift factor, providing a physically meaningful description of the temperature dependence with a single set of parameters. This feature makes the Cross–WLF model more robust and suitable for processing simulations, where temperature effects must be consistently represented. For this reason, despite the slightly lower R2, Cross–WLF was considered the most adequate model.

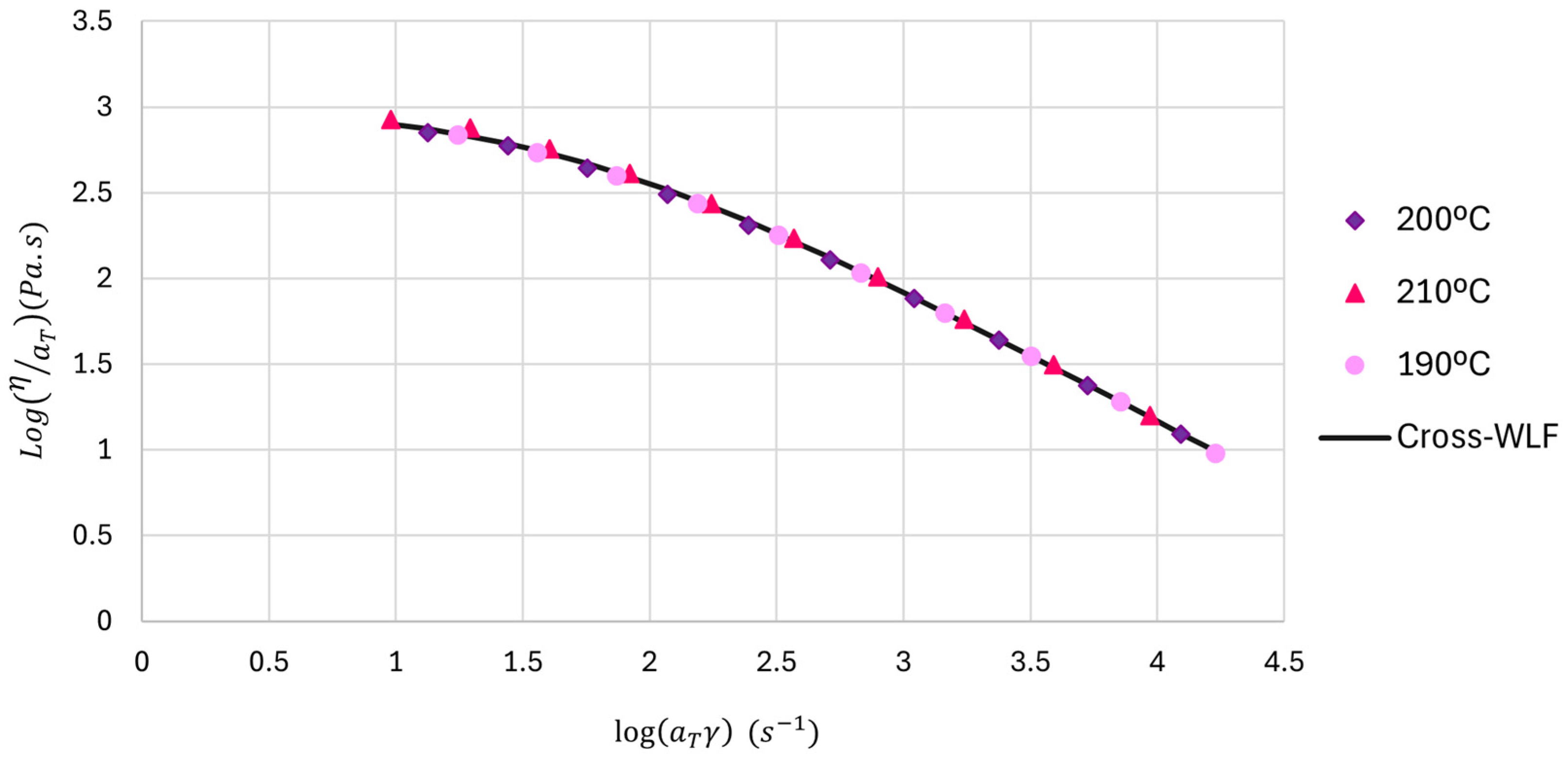

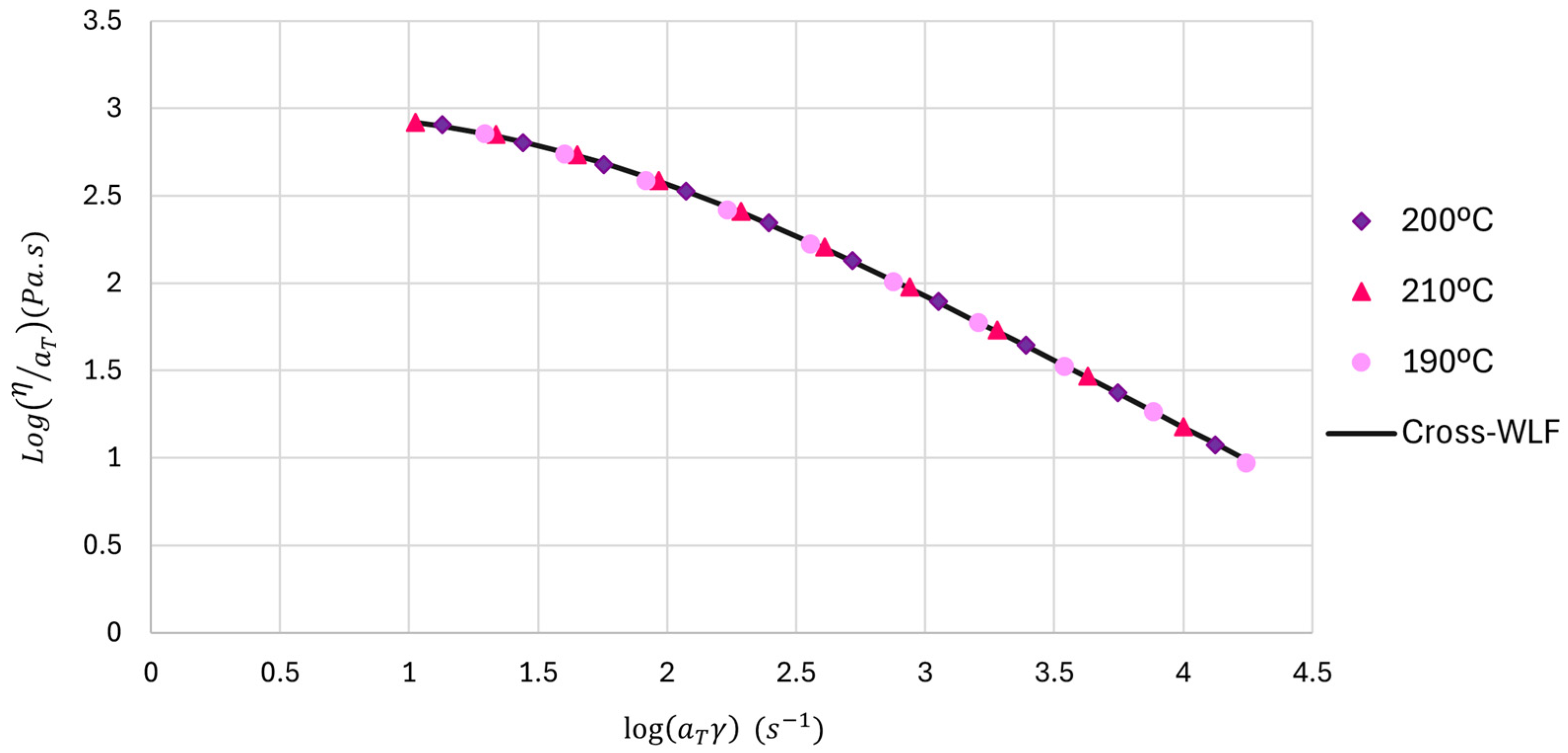

The validity of the time–temperature superposition principle was verified by shifting the experimental viscosity curves obtained at different temperatures. As shown in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, the raw data and the shifted data exhibited a good superposition, confirming that the Cross–WLF model adequately describes the temperature dependence of the composites. This validates the construction of the master curve presented in

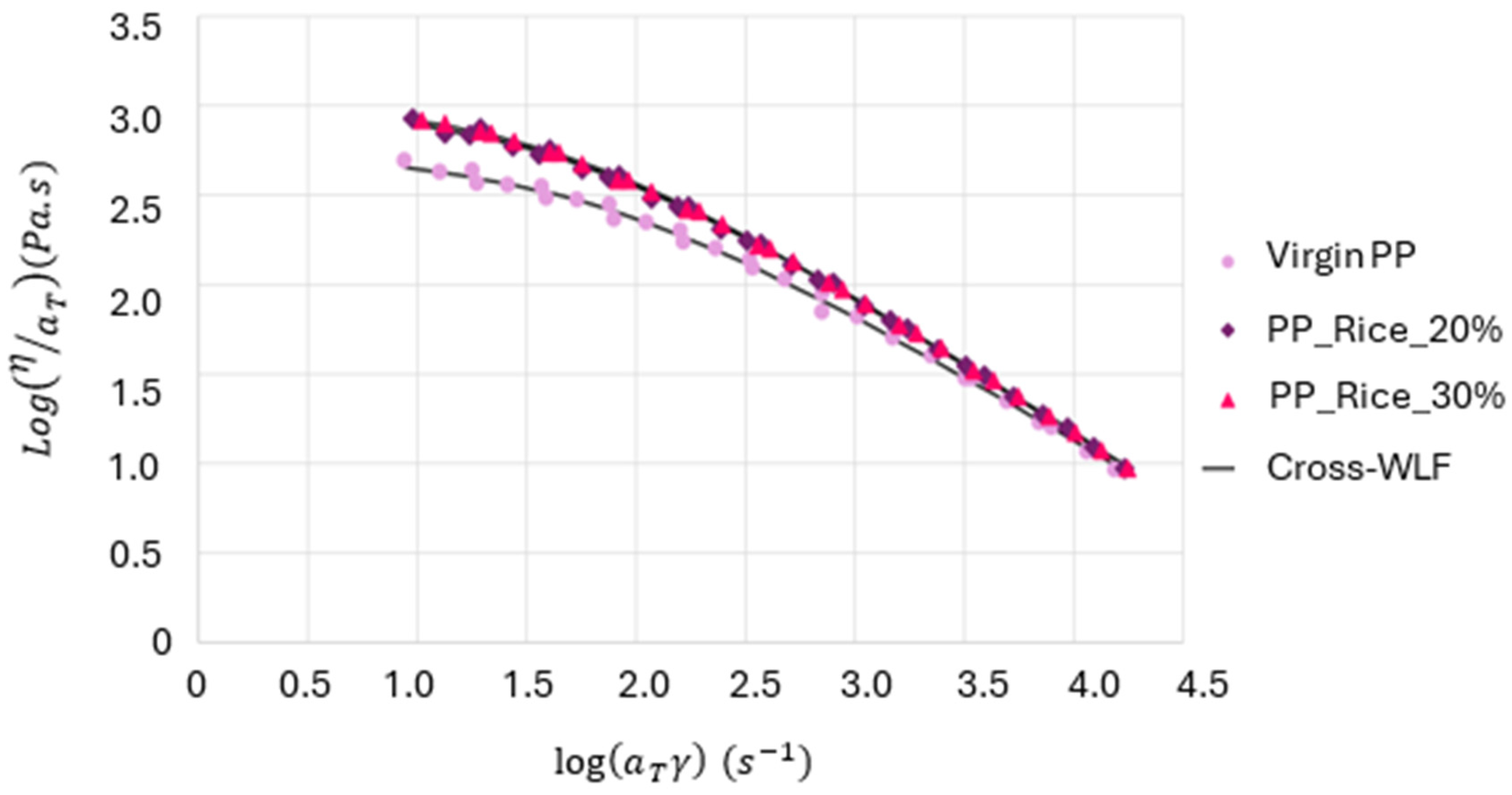

Figure 11.

Table 12 presents the coefficients of the master curve obtained using the Cross–WLF model from the fitting procedure.

The analysis of the master curve (

Figure 11) and

Table 12 revealed that the addition of micronised rice husk particles did not alter the pseudoplastic behaviour of the composites (

< 1). This finding is consistent with studies by Magalhães da Silva et al. [

43] and Frącz and Janowski [

44], who also reported similar

values (ranging from 0.2 to 0.3) for PP-based composites reinforced with cork and wood, respectively. It was also observed that

increased significantly with particle addition, particularly at low shear rates. This trend, attributed to matrix–fibre interactions, was similarly reported by Lewandowski et al. [

45] and Magalhães da Silva et al. [

43]. The presence of the fibres also led to an extension of the Newtonian plateau, as reflected by an increase in the parameter τ. Finally, as noted by Magalhães da Silva et al. [

43] and Lima et al. [

46], all materials exhibited a decrease in viscosity with increasing temperature, as shown in

Table 12. This behaviour is attributed to the increase in free volume between molecules, which reduces intermolecular forces and facilitates flow.

3.7. Tribological Characterisation

Surface roughness analysis is essential in manufacturing technical components, as it affects the appearance, friction, wear, and assembly. Parameters such as S

a, R

a, and R

z assess roughness, while R

sk and R

ku analyse the symmetry and distribution of peaks and valleys, influencing adhesion and precision. This characterisation helps establish manufacturing limits to ensure reproducibility.

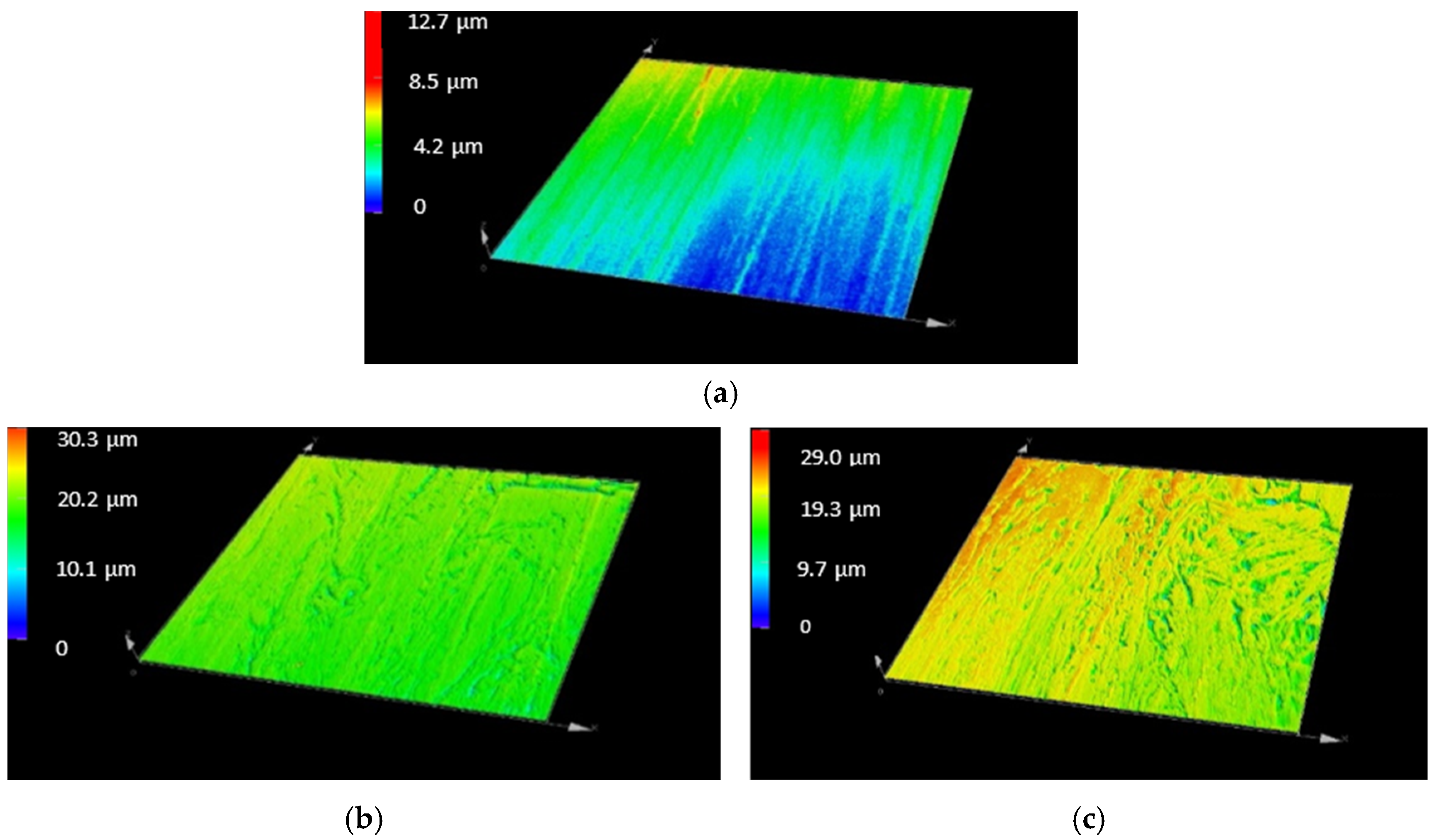

Figure 12 shows the analysed areas, highlighting variations in roughness.

The data presented in

Table 14 reveals that the addition and increased concentration of micronised rice husk particles increase the surface roughness of the composites, in line with the results of Kaymakci et al. [

49] and Haq et al. [

50]. The incorporation of fibres increases the viscosity of the material during injection-moulding, leading to less homogeneous flow patterns and more irregular surfaces [

51]. Rigid particles, such as rice husk fibres/particles, contribute to higher surface roughness compared to neat polypropylene [

49]. This effect is further intensified at higher fibre contents, due to the greater exposure of particles on the surface.

The R

sk values presented in (

Table 14), which reflect surface profile asymmetry, indicate that all composites exhibit negative R

sk values, unlike neat PP, which shows a positive value. A positive R

sk in neat PP suggests the presence of dominant peaks and less uniform roughness distribution, despite its overall low roughness. In contrast, negative R

sk values in the composites imply surfaces with more valleys than peaks and a more evenly distributed roughness. This is associated with improved dimensional stability and reduced polymer shrinkage due to particle addition, which prevents the formation of prominent peaks. These observations are supported by

Figure 12, where neat PP (

Figure 12a) shows colour variation (indicating uneven roughness), while the composites

Figure 12b,c) present a uniform green profile, confirming a more homogeneous surface. The R

ku parameter increased with the introduction of particles, reflecting more pronounced peaks and valleys, but decreased with increasing concentration, suggesting a more uniform profile, possibly due to surface saturation.

The roughness of a material is also related to its tendency to absorb water. Exposure of composite materials to water generally increases surface roughness, which is caused by the uneven swelling of the fibres and the leaching of water-soluble components. This phenomenon can lead to microcracks on the surface or even localised delamination between the polymer matrix and the fibres [

51,

52]. These changes can compromise the aesthetic quality, dimensional stability, and long-term mechanical performance of the part. Therefore, to assess the influence of moisture on the surface morphology, the composites’ roughness was also assessed after the short-term water immersion test.

After 24 h water immersion, the composites surface morphology became more deteriorated (

Figure 13a,b), reflected as an increase in the values of S

a, R

a, and R

z (

Table 15). PP_Rice_30%, showed greater susceptibility to surface degradation and moisture absorption. This behaviour is consistent with the results obtained in the hygroscopicity analysis, where this material showed higher water absorption, and with the observations from the SEM analysis, which revealed a higher presence of voids and particles agglomeration. On the other hand, the PP_Rice_20% showed smaller changes in roughness parameters, suggesting a more even surface aligned with higher resistance to water absorption. The decrease in the absolute values of R

sk and R

ku in both cases indicate surface smoothing and reduced asymmetry, possibly caused by localised swelling induced by the hydrophilic particles within the composite structure.