Impact of Chemical Treatment on Banana-Fibre-Reinforced Carbon–Kevlar Hybrid Composites: Short-Beam Shear Strength, Vibrational, and Acoustic Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Laminate Fabrication

2.3. Testing Procedure

2.3.1. Void Test

2.3.2. Short-Beam Shear Strength (SBSS) Test

2.3.3. Free-Vibration Test

2.3.4. Impedance Tube Test

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Void Percentage

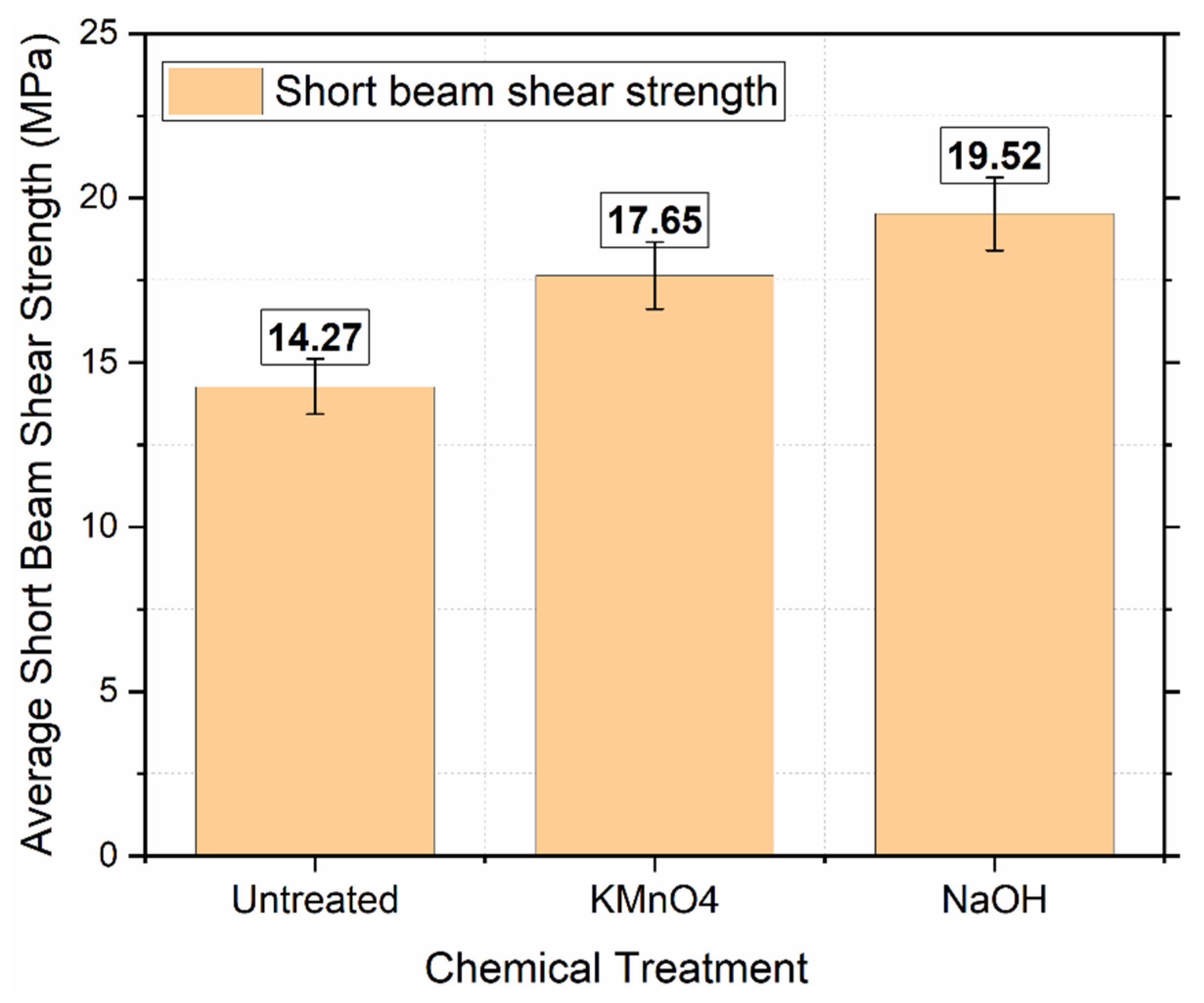

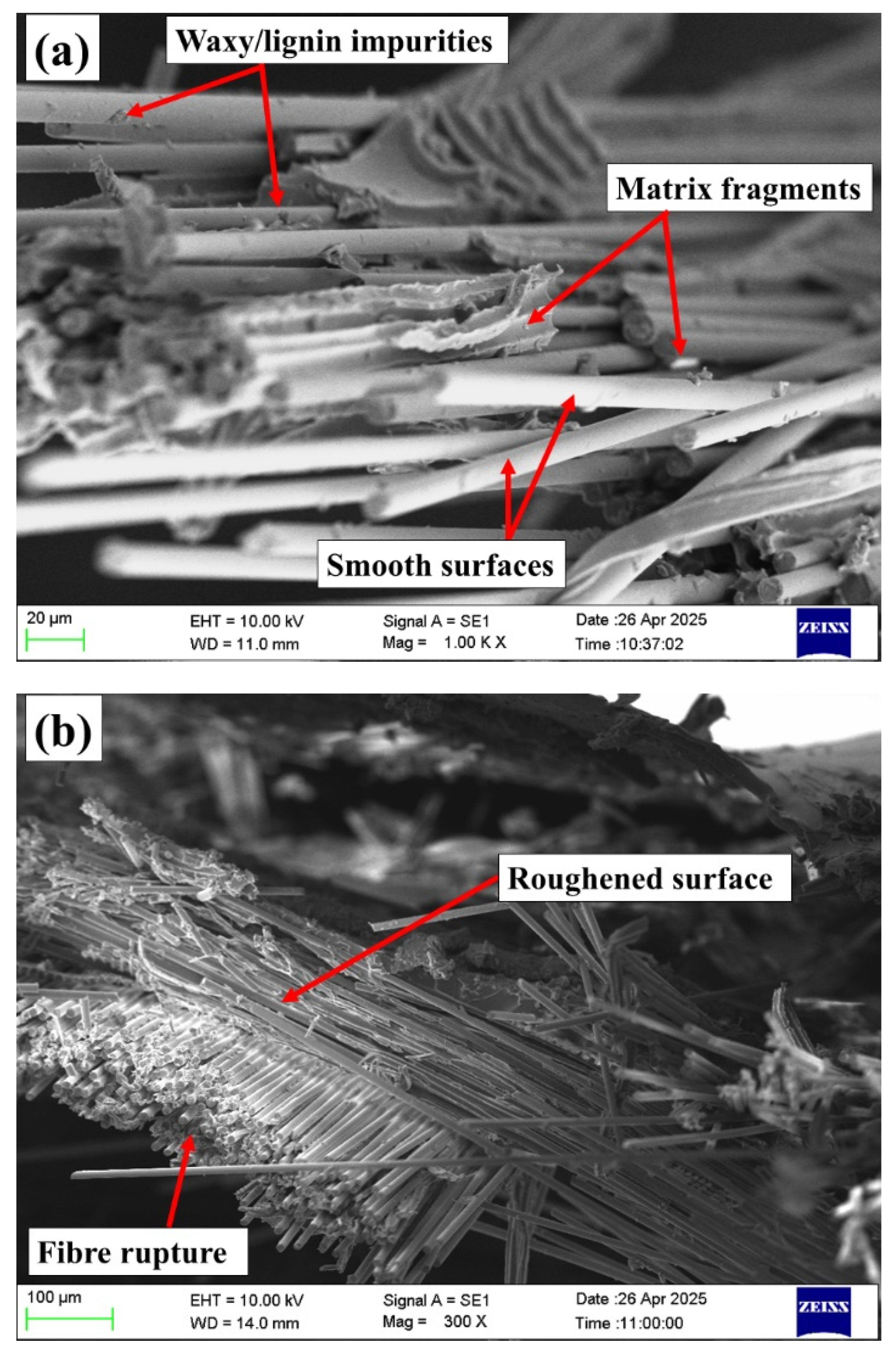

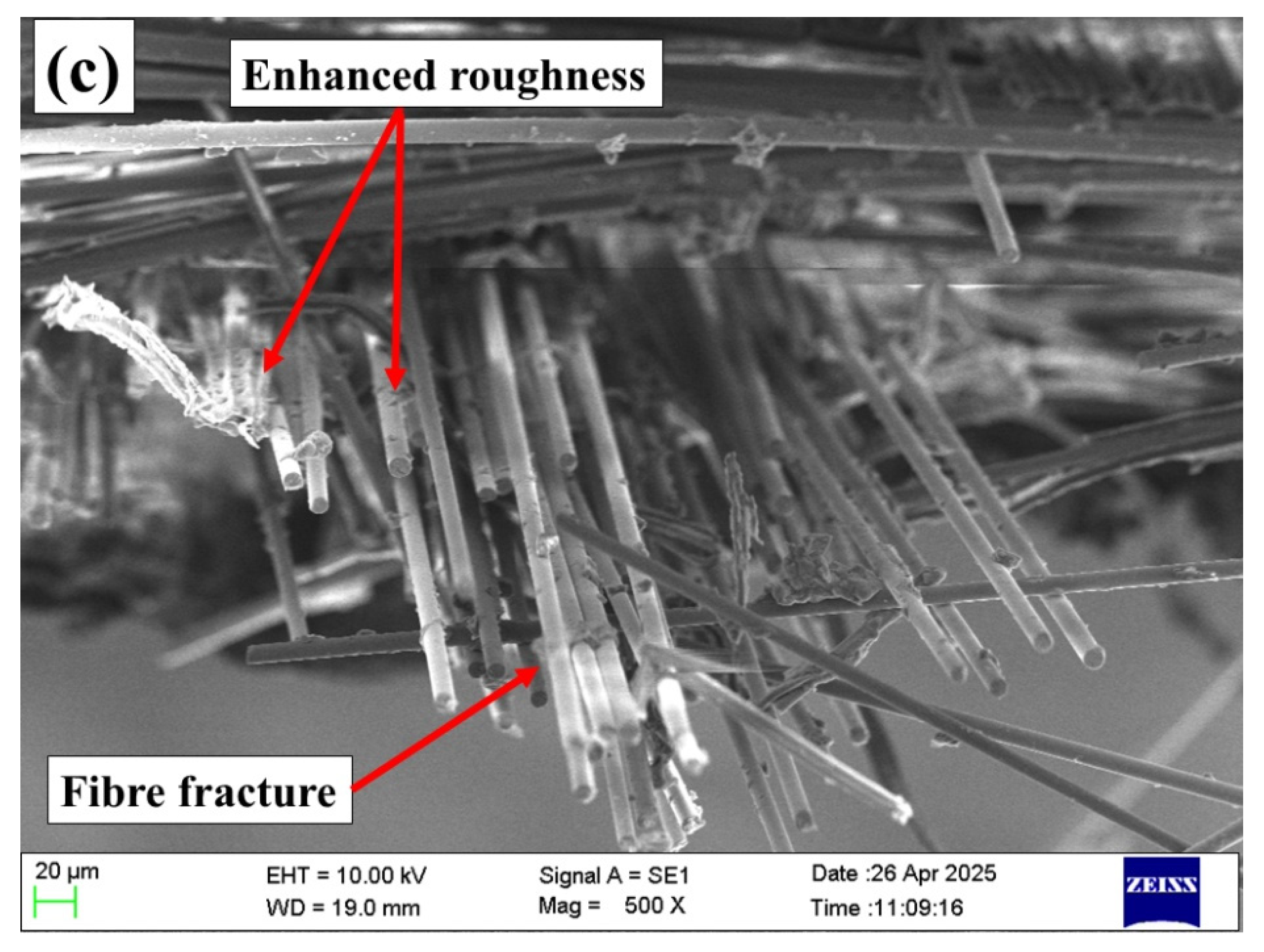

3.2. Short-Beam Shear Strength (SBSS)

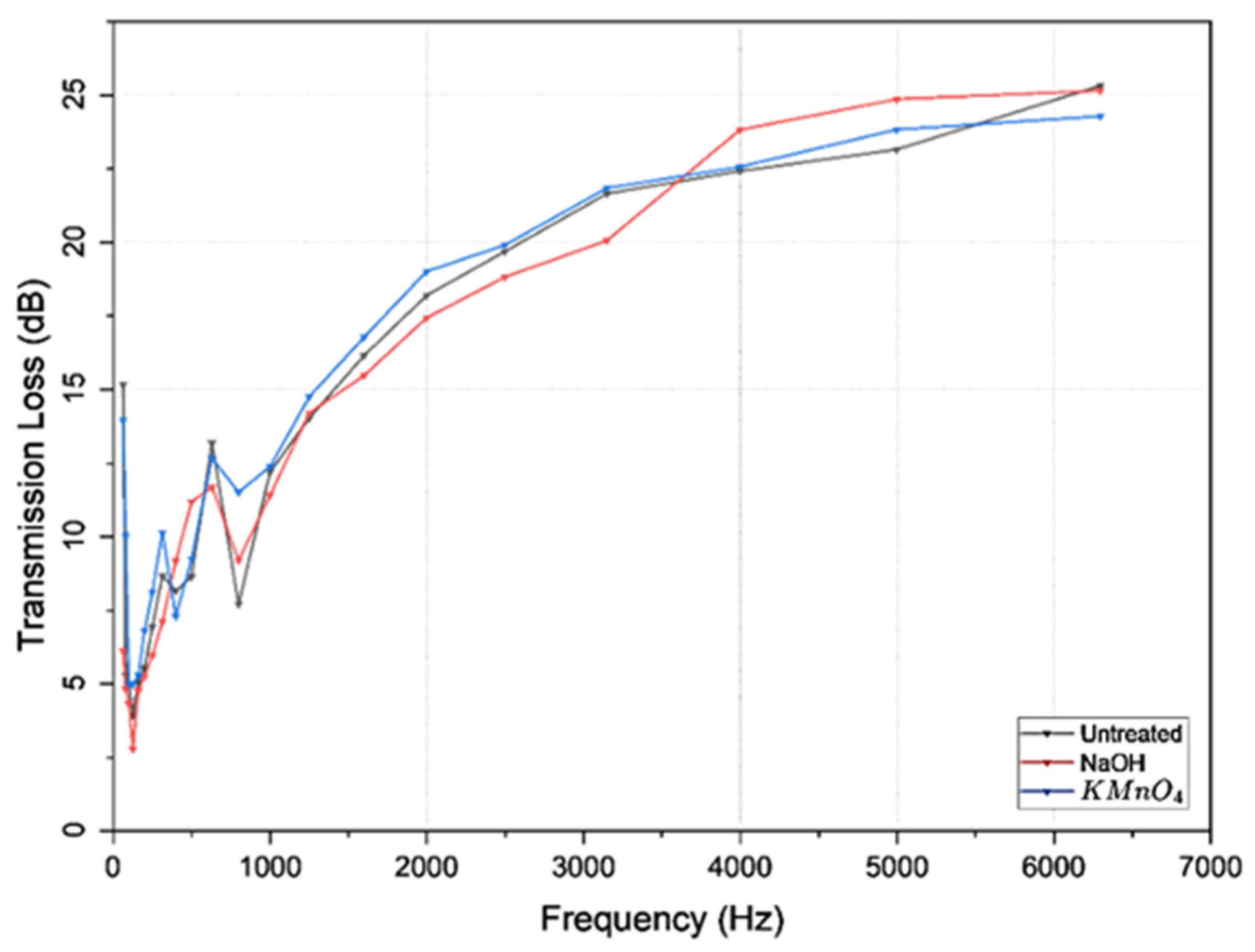

3.3. Impedance Tube Test

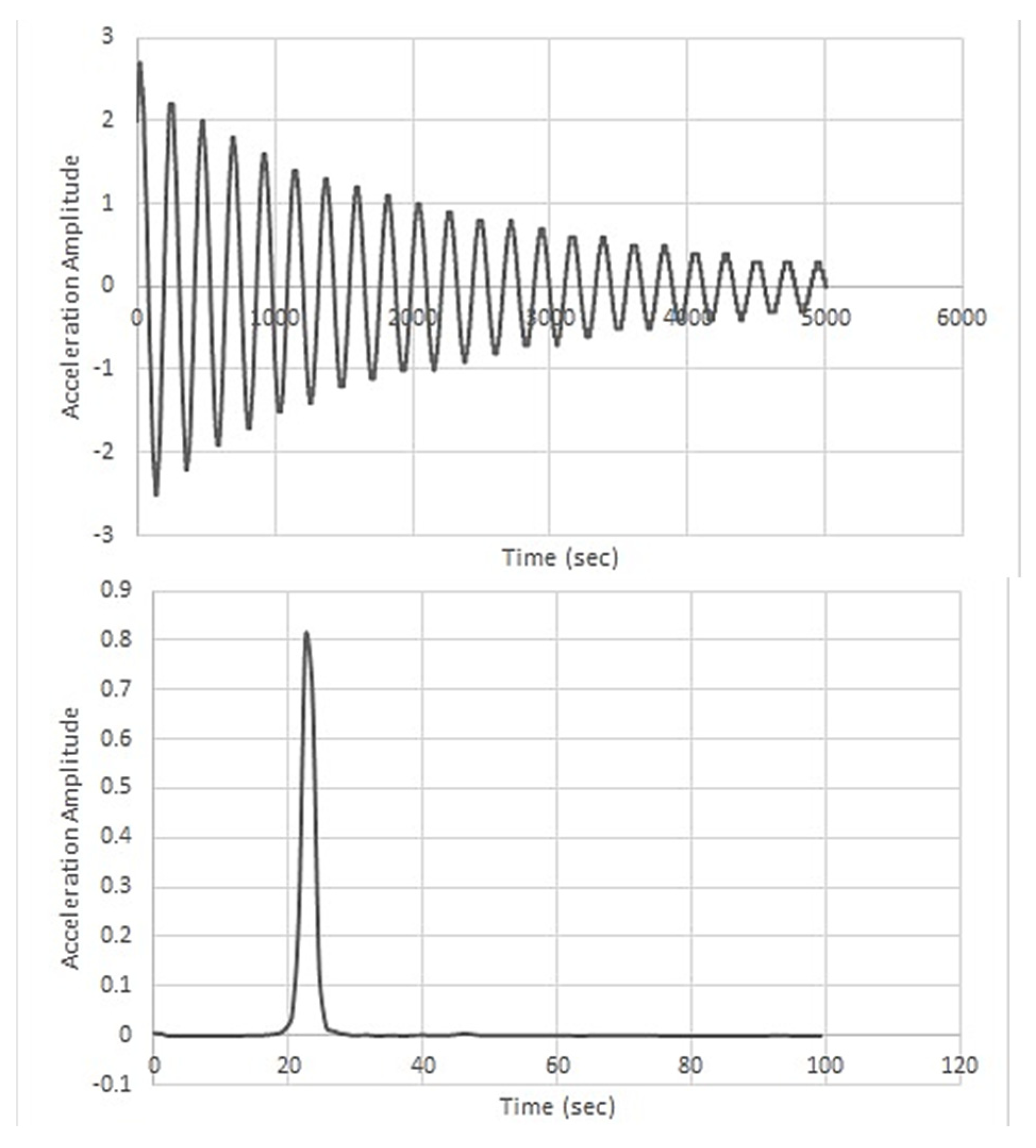

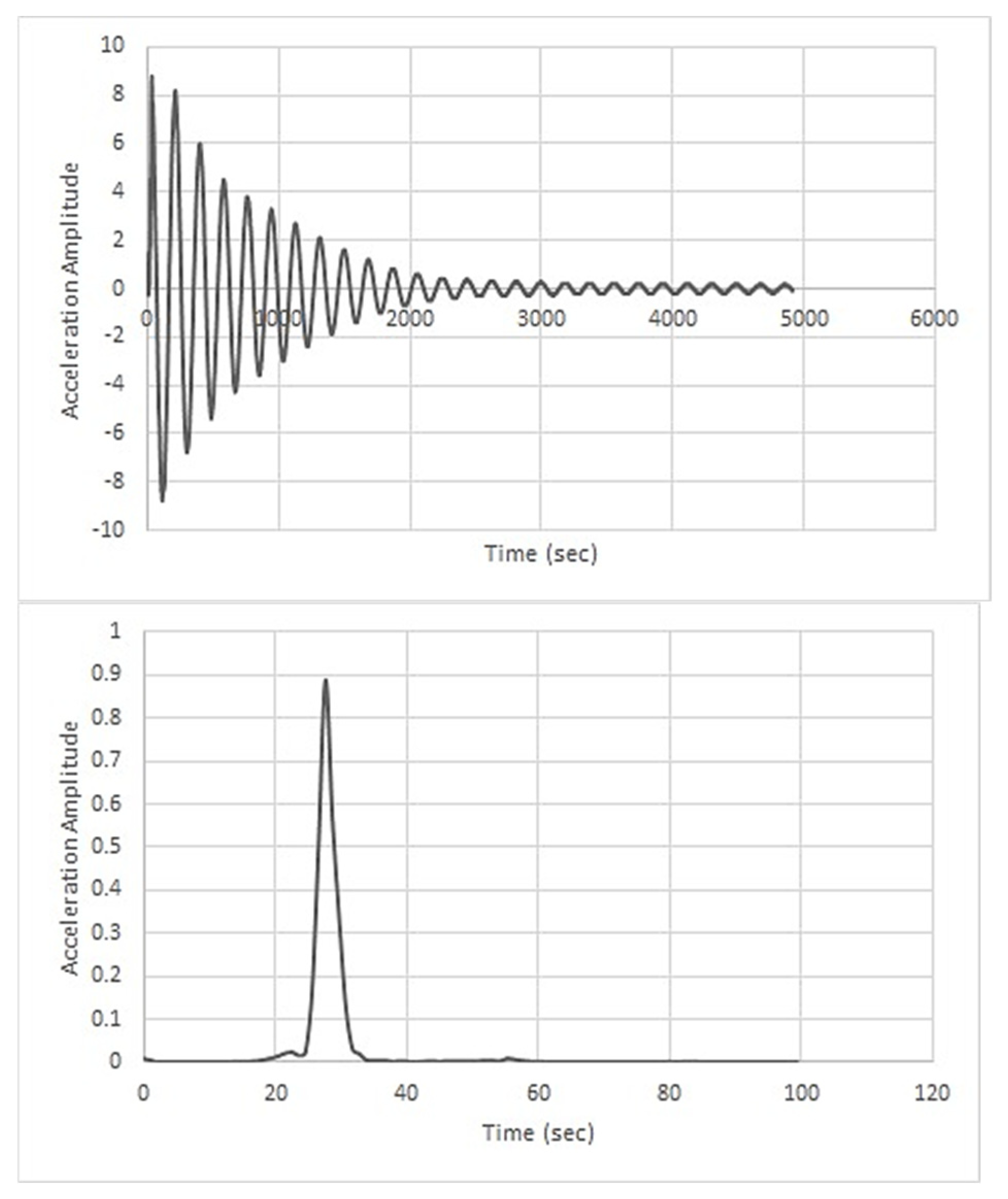

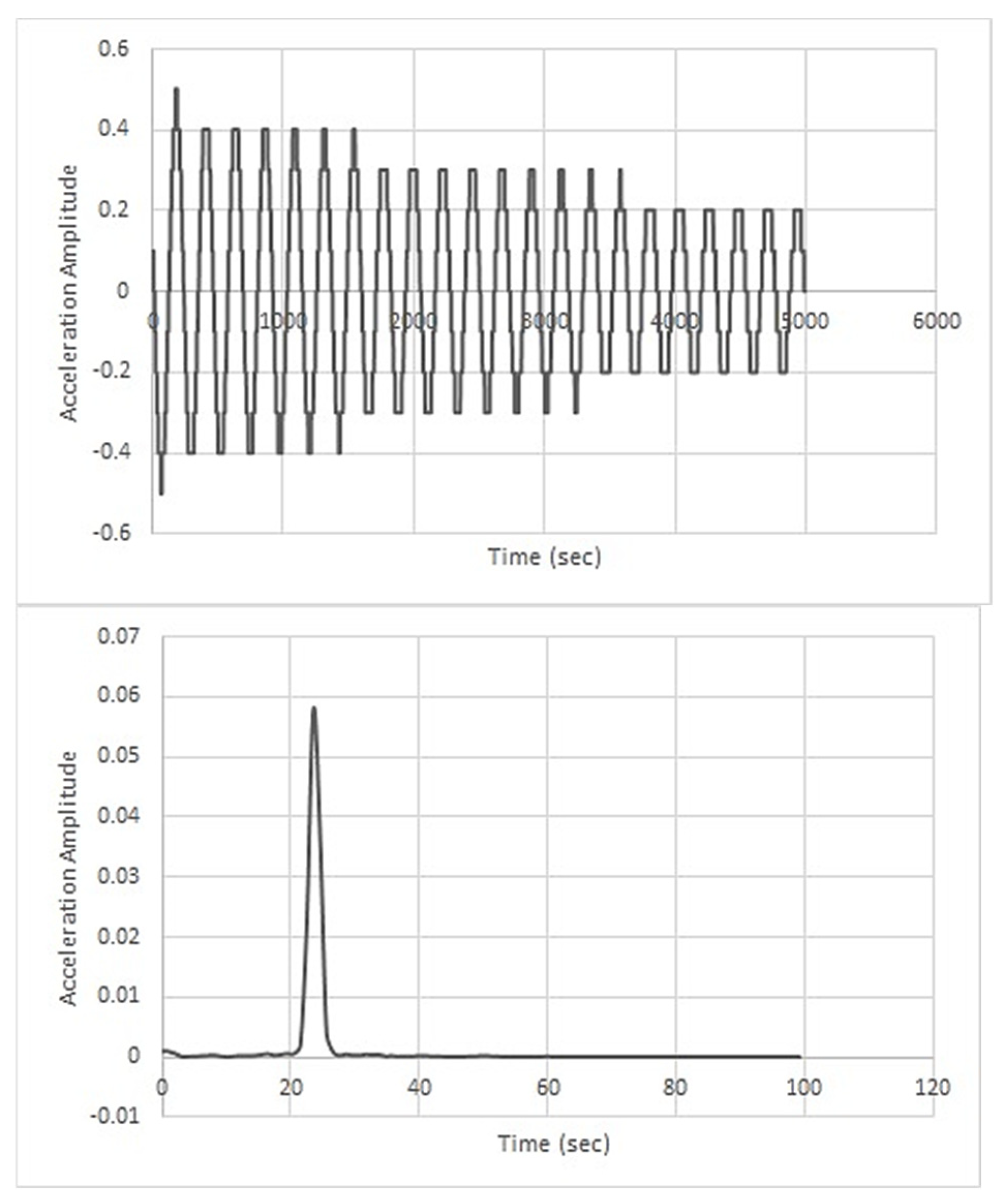

3.4. Free-Vibration Test

4. Conclusions

- Chemical treatments significantly enhanced ILSS of banana-fibre-reinforced carbon–Kevlar composites, with NaOH treatment increasing the ILSS by 36.7% (from 14.27 MPa to 19.52 MPa) and KMnO4 treatment increasing it by 23.7% (to 17.65 MPa).

- Vibration analysis showed NaOH treatment increased stiffness by 21.8% and natural frequency by 9.9%, while KMnO4 treatment enhanced the damping ratio from 0.00716 to 0.0557 compared to untreated composites, indicating superior vibration energy dissipation.

- Acoustic performance improved markedly with KMnO4 treatment, achieving a transmission loss (TL) increase of up to 40% at low frequencies (63 Hz) relative to untreated composites.

- Surface morphology analysis confirmed improved fibre–matrix bonding and reduced defects after chemical treatments, directly correlating with mechanical and functional property enhancement.

- These improvements underline the effectiveness of targeted chemical treatments in developing sustainable, multifunctional hybrid composites with enhanced mechanical strength, vibration damping, and acoustic insulation for advanced engineering applications.

- This work demonstrates the potential of banana fibre and carbon–Kevlar intraply hybrid composites for lightweight structural applications. Future studies should focus on developing finite element models to predict mechanical behaviour and optimise designs. Additionally, evaluating durability under humid and variable environmental conditions is critical to ensure long-term reliability and broaden practical use.

- The limitations of this study include the limited range of chemical treatments investigated, the environmental testing confined to ambient conditions without controlled temperature or humidity variations, and challenges related to industrial scalability such as consistent fibre quality and process optimisation. These factors restrict the immediate applicability of results, indicating the need for future work exploring alternative treatments, more extensive environmental testing, and scalable manufacturing methods.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mallick, P.K. Fiber-Reinforced Composites Materials, Manufacturing and Design, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, C.C.S.K. Composites Manufacturing: Materials, Product and Process Engineering, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, S.; Shanmugam, V.; Sanjeevi, S.; Yang, Y.L.; Marimuthu, U.; Palani, G.; Veerasimman, A.; Trilaksana, H. Prosopis juliflora biochar-based hybrid composites: Mechanical property assessment and development prospects. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 26, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanraj, C.M.; Rameshkumar, R.; Mariappan, M.; Mohankumar, A.; Rajendran, B.; Senthamaraikannan, P.; Suyambulingam, I.; Kumar, R. Recent Progress in Fiber Reinforced Polymer Hybrid Composites and Its Challenges—A Comprehensive Review. J. Nat. Fibers 2025, 22, 2495911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, S.; Parmar, V.; Gohil, P.; Chaudhary, V. Chemical Composition and Mechanical Properties of Natural Fibers. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 3942–3953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, O.; Dutta, J.; Pai, Y.; Pai, D.G. Hole size influence on the open hole tensile and flexural characteristics of aramid-basalt/epoxy composites. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2334911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, Y.; Dayananda Pai, K.; Vijaya Kini, M. Effect of ageing conditions on the low velocity impact behavior and damage characteristics of aramid-basalt/epoxy hybrid interply composites. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 152, 107492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Vijayananth, K.; Murugesan, T.M.; Palaniappan, M.; Santulli, C. The prospects of natural fiber composites: A brief review. Int. J. Light. Mater. Manuf. 2024, 7, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temitayo Oyewo, A.; Olugbemiga Oluwole, O.; Olufemi Ajide, O.; Emmanuel Omoniyi, T.; Hussain, M. Banana pseudo stem fiber, hybrid composites and applications: A review. Hybrid Adv. 2023, 4, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Nguyen, T.H. Study on Mechanical Properties of Banana Fiber-Reinforced Materials Poly (Lactic Acid) Composites. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8485038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.M.; Wang, H.; Lau, K.T.; Cardona, F. Chemical treatments on plant-based natural fibre reinforced polymer composites: An overview. Compos. Part B Eng. 2012, 43, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethi, P.; Balakrishna Murthy, G. Physical and Chemical Properties of Banana Fibre Extracted from Commercial Banana Cultivars Grown in Tamilnadu State. Agrotechnology 2013, 1, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.; Queiroz, H.; Aguiar, R.; Lima, R.; Cavalcanti, D.; Banea, M.D. A review of recent advances in hybrid natural fiber reinforced polymer composites. J. Renew. Mater. 2022, 10, 561–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjana, P.; Arumugaprabu, V. A brief review on mechanical and thermal properties of banana fiber based hybrid composites. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenrayan, V.; Gebremaryam, G.; Shahapurkar, K.; Mani, K.; Fouad, Y.; Kalam, M.A.; Mubarak, N.M.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Abusahmin, B.S. Experimental and numerical assessment of the flexural response of banana fiber sandwich epoxy composite. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komal, U.K.; Verma, V.; Ashwani, T.; Verma, N.; Singh, I. Effect of Chemical Treatment on Thermal, Mechanical and Degradation Behavior of Banana Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites. J. Nat. Fibers 2020, 17, 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuebas, L.; Neto, J.A.B.; de Barros, R.T.P.; Cordeiro, A.O.T.; dos Santos Rosa, D.; Martins, C.R. The incorporation of untreated and alkali-treated banana fiber in SEBS composites. Polimeros 2021, 30, e2020040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.A.; Joseph, K.; Mathew, G.D.G.; Pothen, L.A.; Thomas, S. Influence of polarity parameters on the mechanical properties of composites from polypropylene fiber and short banana fiber. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2010, 41, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudva, A.; Mahesha, G.T.; Pai, D. Influence of Chemical Treatment on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Bamboo Fibers as Potential Reinforcement for Polymer Composites. J. Nat. Fibers 2024, 21, 2332698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudva, A.; Mahesha, M.; Hegde, S.; Pai, D. Influence of chemical treatment of Bamboo fibers on the vibration and acoustic characterization of Carbon/Bamboo fiber reinforced hybrid composites. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 075304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Fajardo, I.; Rivero-Romero, O.; Unfried-Silgado, J. Investigation of the Effect of Chemical Treatment on the Properties of Colombian Banana and Coir Fibers and Their Adhesion Behavior on Polylactic Acid and Unsaturated Polyester Matrices. Fibers 2024, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadire, T.; Joshi, S.N. Effects of alkaline treatment and manufacturing process on mechanical and absorption properties of Wild Abyssinia Banana fiber reinforced epoxy composite. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, 98, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppuraj, A.; Angamuthu, M. Investigation of mechanical properties and free vibration behavior of graphene/basalt nano fi ller banana/sisal hybrid composite. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouf, A.; Alam, R.; Belal, S.A.; Ali, Y. Mechanical and Thermal Performances of Banana Fiber—Reinforced Gypsum Composites. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 2025, 8120082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilrajan, S.; Venkateshwaran, N.; Ismail, S.O.; Nagarajan, R.; Ayrilmis, N. Improvement of vibration and acoustic properties of woven jute/polyester composites by surface modification of fibers with various chemicals. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Bundela, A.S.; Choudhary, P.; Pai, Y.; Pai, D.G. Effect of carbon-Kevlar intraply surface layers on the mechanical and vibrational properties of basalt reinforced polymer composites. Cogent Eng. 2024, 11, 2403704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Pai, Y. Materials Today: Proceedings Mechanical characterization of quasi-isotropic intra-ply woven carbon-Kevlar/epoxy hybrid composite. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 52, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Pai, Y.; Pai, D.; Mahesha, G.T. Assessment of ageing effect on the mechanical and damping characteristics of thin quasi-isotropic hybrid carbon-Kevlar/epoxy intraply composites and damping characteristics of thin intraply composites. Cogent Eng. 2023, 10, 2235111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.S.; Siva, I.; Jeyaraj, P.; Jappes, J.T.W.; Amico, S.C.; Rajini, N. Synergy of fiber length and content on free vibration and damping behavior of natural fiber reinforced polyester composite beams. J. Mater. 2014, 56, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K. Banana fibre-based structures for acoustic insulation and absorption. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 51, 1355–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, K.S.; Shrinivasa, M.D.; Yashwanth, H.L.; Sharanya, I.S.; Nikam, H. Results in Engineering Evaluation of mechanical, acoustic and vibration characteristics of calamus rotang based hybrid natural fiber composites. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D792-20; Standard Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Density) of Plastics by Displacement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D2344/D2344M-13; Standard Test Method for Short-Beam Strength of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials and Their Laminates. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. Available online: www.astm.org (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ASTM E756-05; Standard Test Method for Measuring Vibration-Damping Properties of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Namrata, B.; Pai, Y.; Nair, V.G.; Hegde, N.T.; Pai, D.G. Analysis of aging effects on the mechanical and vibration properties of quasi-isotropic basalt fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scantek, I. SW Series Impedance Tube Solutions. Available online: https://scantekinc.com/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- ISO-10534; Determination of Sound Absorption Coefficient and Impedance in Impedance Tubes. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Shivanagere, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Goyal, P. Modelling of glass fibre reinforced polymer (Gfrp) for aerospace applications. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2018, 13, 3710–3728. [Google Scholar]

- Yahiya, M.; Venu Kumar, N. A review on natural fiber composite with banana as reinforcement. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, M.V.; Padmaraj, N.H.; Hegde, S.; Yash, G.M.; Kini, C.R. Analysis of effect of thickness and surface treatment on sound transmission loss characteristics of natural fibres. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selver, E. Acoustic properties of Hybrid Glass/Flax and Glass/Jute composites consisting of different stacking sequences. Tekst. Ve Muhendis 2019, 26, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthilrajan, S.; Venkateshwaran, N.; Giri, R.; Ismail, S.O.; Nagarajan, R.; Krishnan, K.; Mohammad, F. Mechanical, vibration damping and acoustics characteristics of hybrid aloe vera/jute/polyester composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 2402–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author & Year | Work Carried Out | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Paul et al. (2010) [18] | Banana fibre was treated with alkali, stearic acid, triethoxy octyl silane, KMnO4, and benzoyl chloride | Fibres treated with KMnO4 exhibited enhancement in tensile strength by 5% and flexural strength by 10% |

| Komal et al. (2020) [16] | Composites containing banana pseudo-stem (BPS) fibres treated with a 5% (w/v) aqueous sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution | The composite showed approximate improvements of 4% in tensile strength, around 5% in flexural strength, and about 12% in impact strength |

| Cuebas et al. (2021) [17] | Banana fibres were subjected to alkali treatment by soaking in 5% sodium hydroxide solution (w/v) | The FTIR test revealed a reduction in hydroxyl (OH) groups, indicating increased hydrophobicity and improved mechanical properties |

| Chenrayan et al. (2023) [15] | Chopped fibres were treated with 5% alkaline solution (NaOH) | The flexural characteristics of sandwich specimens containing 10% banana fibre were higher than the neat epoxy core |

| Fajardo et al. (2024) [21] | Banana fibres were soaked in 5% NaOH for 1 h at room temperature with stirring, then washed with acetic acid and water to remove NaOH residues | FTIR confirmed the removal of non-cellulosic components, while SEM revealed increased surface roughness due to impurity removal; interfacial shear strength improved by 10% over untreated fibres |

| Nguyen and Nguyen (2022) [10] | Banana fibres were treated with NaOH solutions at various concentrations | SEM analysis revealed enhanced fibre bonding and wetting properties for 5% NaOH-treated fibres |

| Kadire and Joshi (2024) [22] | Banana fibres treated with 2%, 5%, and 7% (w/v) NaOH concentrations | A 5% NaOH treatment lowered water absorption and increased tensile, bending, and low velocity impact strengths of the composite by approximately 15%, 9%, and 30%, respectively |

| Author & Year | Work Carried Out | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Kumar et al. (2014) [29] | Effect of fibre content and length on free vibration and damping of banana/sisal/polyester composites, short fibres with varying wt%, compression moulding | Natural frequency and damping improved notably with 50 wt% fibre content (exact % not listed), acoustic absorption improved with fibre density |

| Kuppuraj et al. (2022) [23] | Banana/sisal epoxy hybrid, graphene fillers (varying wt%), hand lay-up | Natural frequency up to 100 Hz (Mode 1), damping factor 0.0883, dense hybrid structures expected to provide good sound absorption |

| Singh et al. (2022) [30] | Banana fibre–polypropylene matrix, alkali-treated, impedance tube measurement | Noise reduction coefficient (NRC) 0.78 for 4500 gsm multilayer samples, max. transmission loss 23 dB |

| Sagar et al. (2022) [5] | Influence of NaOH treatment and PLA coating on jute/banana hybrid composites | Tensile strength +20.56%, flexural strength +16.7% (related to improved vibrational behaviour) |

| Agarwal et al. (2024) [26] | Intraply layers consisting of carbon and Kevlar as surface layers and three layers of basalt as core subjected to mechanical tests | Hybrid laminates exhibited a maximum impact strength of 136.25 kJ/m2, marking a 24.4% increase compared to basalt composites; enhancement in impact toughness is credited to the incorporation of surface intraply layers |

| Senthilrajan et al. (2025) [25] | Effect of surface modification on vibration and acoustic properties | NaHCO3 treatment highest natural frequency 61 Hz, improved damping, max, sound absorption coefficient 0.67 at ~2k Hz, 69% higher than untreated |

| Lokesh et al. (2025) [31] | Calamus rotang/glass fibre hybrid composites including banana fibre reinforcement | Damping ratio peak at 8% fibre loading, Sound absorption improved with hybrid fibres |

| Rouf et al. (2025) [24] | Alkali-treated banana fibres at 0–24 wt% in epoxy matrix | Vibration damping improves up to ~15–20% with 24 wt% fibres |

| Type of Fibre | Weave Pattern | Aerial Density (Grams per Square Meter) | Thickness (mm) | Filament Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banana fibre mat | Plain weave | 250 | 0.3 | 3K |

| Carbon–aramid intraply mat | Twill weave | 300 | 0.35 | - |

| Composite | Experimental Density, (Gram per Cubic Centimetre, g/cc3) | Theoretical Density, (Gram per Cubic Centimetre, g/cc3) | Void % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 1.57 | 1.61 | 2.54 |

| NaOH-treated | 1.43 | 1.46 | 2.09 |

| KMnO4-treated | 1.48 | 1.50 | 1.35 |

| Composite Type | Natural Frequency (Hz) | Stiffness (N/m) | Damping Ratio (ζ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 26.08 ± 1.43 | 7780.23 ± 268.32 | 0.00716 ± 0.0002864 |

| NaOH-treated | 28.68 ± 1.81 | 9480.51 ± 303.51 | 0.00398 ± 0.000159 |

| KMnO4-treated | 22.12 ± 1.67 | 5640.84 ± 245.84 | 0.0557 ± 0.00228 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

M., K.B.; Mehar, K.; Pai, Y. Impact of Chemical Treatment on Banana-Fibre-Reinforced Carbon–Kevlar Hybrid Composites: Short-Beam Shear Strength, Vibrational, and Acoustic Properties. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120661

M. KB, Mehar K, Pai Y. Impact of Chemical Treatment on Banana-Fibre-Reinforced Carbon–Kevlar Hybrid Composites: Short-Beam Shear Strength, Vibrational, and Acoustic Properties. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(12):661. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120661

Chicago/Turabian StyleM., Kanchan B., Kulmani Mehar, and Yogeesha Pai. 2025. "Impact of Chemical Treatment on Banana-Fibre-Reinforced Carbon–Kevlar Hybrid Composites: Short-Beam Shear Strength, Vibrational, and Acoustic Properties" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 12: 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120661

APA StyleM., K. B., Mehar, K., & Pai, Y. (2025). Impact of Chemical Treatment on Banana-Fibre-Reinforced Carbon–Kevlar Hybrid Composites: Short-Beam Shear Strength, Vibrational, and Acoustic Properties. Journal of Composites Science, 9(12), 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9120661